#Codex Vaticanus A

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

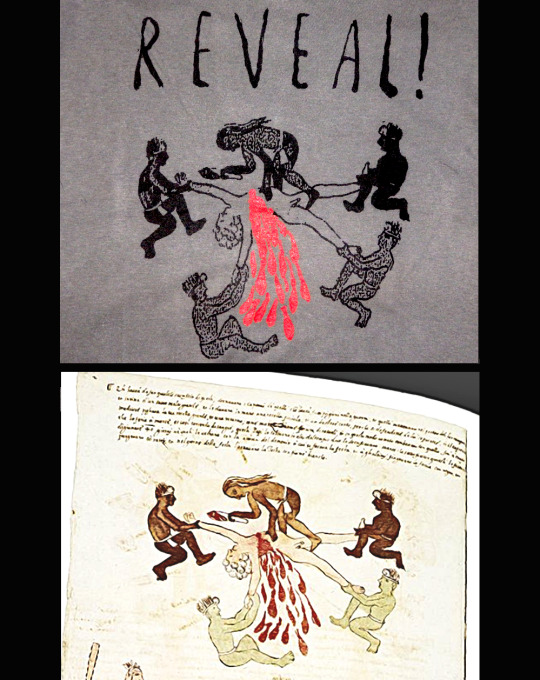

From the Vault: Bloody Revelations

Top image: Reveal! design on t-shirt, 2018

Bottom image: illustration from Codex Vaticanus A, ca. 1580

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Manuscript Monday

Today we will be exploring our facsimile of an Exultet Roll, a southern Italian manuscript originally produced around 950 CE. This is a long scroll (24 feet long, unrolled) containing the text and chant notation for the Exultet, or Exsultet, which is a chant performed at the Easter Vigil mass, usually by a deacon before the congregation. It celebrates the night of the resurrection of Jesus, and is performed in praise of the Paschal candle, which is lit at every mass during the liturgical year. This candle slowly melts down until it is almost completely depleted, and then it is replaced at the Easter Vigil each year.

Although today it is usually chanted in the vernacular language of the Church being attended, this chant is referred to as the Exultet due to the first Latin word of the chant, which begins 'Exultet iam angelica turba coelorum' ('Let the angelic host of heaven exult').

Personally, one of my favorite parts of the Exultet chant is the portion known as the 'Praise of the Bees', which is said to be a reference to Virgil's writings in the Aeneid. This portion of the chant praises the work of the bees done to create the wax with which the Paschal Candle is made:

On this, your night of grace, O holy Father, accept this candle, a solemn offering, the work of bees and of your servants' hands, an evening sacrifice of praise, this gift from your most holy Church. But now we know the praises of this pillar, which glowing fire ignites for God's honor, a fire into many flames divided, yet never dimmed by sharing of its light, for it is fed by melting wax, drawn out by mother bees to build a torch so precious.

The codex -- books bound on one side as we know them today -- had long replaced the scroll by the time this manuscript was produced. So, why is this manuscript in the form of a scroll, rather than a codex? The reason is due to its ceremonial use at the Vigil mass. As the deacon chanted the Exultet, he would actually let the scroll unroll over the front of the ambo, so that members of the congregation could see the illuminations on the manuscript. Because of this use during the mass, these scrolls also have a peculiar feature: the text is written in an opposite orientation to the illuminations. This allowed the deacon to recite the chant accurately while the images were also oriented correctly for the attendees of the mass.

Use of Exultet scrolls during the Easter Vigil is unique to Southern Italian Catholic churches around Benevento and Montecassino and began being produced in the 10th century. All extant Exultet Rolls today were made between the 10th and 13th century.

Our facsimile is a reproducton of the Vatican Library's Codex Vaticanus Latinus 9820 and was published in Graz by the Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt in 1975. There are currently no complete images of the Scroll online, but the Vatican Library does have a digitized document explaining the condition of the scroll when it arrived there around 1200 CE.

View more manuscript posts.

View more Manuscript Monday posts.

– Sarah S., Former Special Collections Graduate Intern

#manuscript monday#manuscript#manuscripts#illuminated manuscripts#exultet roll#Exultet scroll#Easter#Easter Vigil#Catholic#Codex Vaticanus Latinus 9820#Codex Vat. Lat. 9820#Akademische Druck- u. Verlagsanstalt#manuscript facsimile#facsimiles#scrolls#Vatican Library#Vatican#Sarah S.

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I think the term 'bone frenzy' might be a term open to course misinterpretation, personally."

Is there already a campaign to beg Tamsyn to write The Noniad for real? Can we start one? Am I the only one?

#ortus nigenad#matthias nonius#the noniad#the locked tomb#harrow the ninth#gideon the ninth#harrowhark nonagesimus#please?#tamsyn muir#it's only 18 books#I assume this is like classical “books”#so it's maybe what#300 pages?#using the codex vaticanus as a baseline reference?

282 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bilderstreit

1.

Ein Teil der Rechtswissenschaft beschäftigt sich mit der Frage nach den Medien, dabei auch mit der Frage, was ein Bild ist. Da ist der Teil, der sich mit dem Medienrecht befasst, im weiteren Sinne ist das die Rechtswissenschaft, die sich damit beschäftigt, wie das Wissen ums Recht produziert und reproduziert wird, wie es übertragen und geteilt wird, welche Mittel und Techniken dabei verwendet werden.

Was heute als Mediengeschichte und Medientheorie des Rechts kursiert, das interessiert mich u.a. als Weiterführung eines Streites, der mit den Inventionen des byzantinischen Bilderstreites Bilderstreit genannt werden kann. Wenn die Medientheorie und Mediengeschichte rechtswissenschaftlich wird, wenn sie mit Theorien der großen Trennung (der Ausdifferenzierung), des Take-Offs, einer großen Anreicherung des Westens oder gar mit Theorien abendländischen Individualismus und Universalismus einhergehen, dann sind diese Theorie der Geschichte der Bilderstreites assoziiert. Welche Rolle die Sprache für die Entwicklung von Rechtsordnungen hat, welche Rolle der Buchdruck oder die Schrift spielen, welche Rolle soziale Netzwerke, Gerichtsöffentlichkeit, das Menschenbild oder der menschliche Körper spielt: Auch wenn sich die Rechtswissenschaft nicht direkt mit dem Bild befasst, kann der Bilderstreit über (kleine) Umwege, wie durch einen Nebeneingang, in die Auseinandersetzung eingeschleust werden, die Beispiele lassen sich fortsetzen. Meine These lautet, dass es sich dabei um eine Auseinandersetzung handelt, die historischen Ausprägungen des Bilderstreit soweit affin ist, dass man sie sogar selbst als aktualisierte Form eines Bilderstreites beschreiben kann. Sie sind historischen Ausprägungen des Bilderstreites ähnlich oder verwandt - und diese Ähnlichkeit oder Verwandtschaft ist Teil dessen, um das gestritten wird. Die Ähnlichkeiten und Verwandschaften sind z.B. daran festzumachen, dass um die Eigenschaften und den Status von Medien gesellschaftlicher Konflikte und Koordination - und dabei auch um das Verhältnis zwischen Rationalität und einer 'minoren' Epistemologie gestritten wird.

Die Beziehung zeitgenössische Theorie 'westlicher Medien', die mit Thesen zur Inkarnation oder Exkarnation, zu einer dank Buchdruck erfolgten Umstellung des Diskurses von Bildern auf Begriffe und zu einer Abfolge von 'Trennungen' (zum Gewinn von Distanz, Kontextfreiheit, Neutralität, Sachlichkeit und Abstraktion) hat Bezüge zu Figuren des Bilderstreites, etwa zu Hierarchisierung von Sinnlichkeit/ Sinn hat. Auch der 'Wiedereintritt der Bilder', den man in jüngeren Texten der Rechtswissenschaft mit Geschichten und Theorien der Persönlichkeitsideale und der Subjektivierung sowie in Auseinandersetzungen um 'Sichtbarkeit' findet, deute ich in der Tradition des Bilderstreites.

2.

Eine These lautet, dass der Bilderstreit Bilder durch Bestreiten erscheinen lässt. Bilderstreit ist also dasjenige, was Bilder händelt, sei es, indem sie zerstört oder aufgestellt, negiert oder affirmiert, zensiert oder gefördert werden.

In den letzten Jahren hat Horst Bredekamp sich unter anderem mit einer Geschichte und Theorie des Bildaktes beschäftigt, also auch mit Kulturtechniken, in denen das Bild auch als Subjekt und Akteur mit Handlungsmacht auftaucht. Im Bilderstreit taucht das Bild aus eine Weise auf, die unsicher ist, besser gesagt unbeständig. In bezug auf die philosophischen, grammatikalischen und theoretischen Kategorien taucht das Bild in der jüngeren Literatur an unterschiedlichen Stellen auf, nicht nur als Subjekt oder Aktant, auch als Objekt, Quasiobjekt (Serres) odser Grenzobjekt (Susan Leigh Star). Man macht es sich in der Forschung nicht leichter, wenn man sagt, dass unterschiedlichen Positionierungen des Bildes alle Recht haben - dies aber vielleicht 'nur' das Recht ist, Bilder und ihre Positionen zu bestreiten. Man wird dann schärfer Linien der Auseinandersetzungen verfolgen müssen, etwa die Art und Weise, wie in Bezug auf das Verhältnis zwischen Bild und Begriff mit Fragen der Ästhetik, Wahrnehmung und Hirnforschung gleichzeitig die Sinne des Menschen geteilt und abgeschichtet oder stratifiziert werden.

Mein Ansatz ist perspektivisch und relativ. Eine allgemeine Theorie des Bildes oder gar eine 'Absolutierung' des Bildes: das gibt es, kommt vor, kann passieren, passiert immer wieder. Daran arbeite ich, um so ein Auftauchen absoluter Bilder als Teil des Bilderstreites wie auf einer Karte einzutragen, also um das Absolute daran wieder zu relativieren. Solche Absolutierungen, sagen wir so: Einrichtungen absoluter Bilder, tauchen kulturtechnisch auf, d.h. mit Operationen. die nicht nur Bildoperationen sind. Sie können mit bestimmten Maltechniken auftauchen wie im Suprematismus, sind aber auch da mit anderen Techniken verbunden, etwa (besonders im religösen und politischen Kontex) mit Architektur, mit liturgischen, choreographischen Techniken oder mit einem Diskurs, der Aussagen und Massenmedien auffährt wie das beim Bildnis des Souveräns der Fall sein soll. Man sollte nicht ignorieren, dass absolute Bilder historisch auftauchen. Das Projekt berücksichtigt so ein Auftauchen aber als ein Bestreiten. Ob ihr Auftauchen begrifflich am besten als Illusion oder Fiktion beschrieben ist, das würde ich bis auf weiteres offen lassen; die Effektivität und ihr Limit, schließlich auch dasjenige, was die Vorstellung eines absoluten Bildes wiederum verstellt und insoweit diese Vorstellung gar als Lüge erscheinen lässt da lässt sich an Details vielleicht besser klären.

Wesentliche Eigenschaften des Bildes, seine Eigentümlichkeit, sein Eigenes - das interessiert mich also als Teil einer Auseinandersetzung und in Bezug auf die iKulturtechniken. Wie die Eigenschaften eines Bildes behauptet werden, wie seine Stellung gegenüber anderen Dingen, anderen Medien oder gar dem Menschen behauptet, besser gesagt kulturtechnisch ein- und ausgerichtet werden, das allerdings interessiert mich sehr. Kultur ist ein "historischer Begriff" (Luhmann), ein Vergleichsbegriff. Kultur kommt dann auf, wenn auch eine zweite Kultur aufkommt (etwa wenn eine Gesellschaft glaubt, die habe etwas von sich überwunden oder hinter sich gelassen oder aber von anderen Gesellschaften erfolgreich getrennt), mit dem Aufkommen sind geographische oder historische Grenzen verknüpft. Technik ist artifiziell, auch wenn Natur involviert bleibt (und das eventuell ohne hierarchisierbare Bedingungen) . Die Arbeiten von Cornelia Vismann aufgreifend meine ich, wenn ich von Kulturtechniken spreche, juridische Kulturtechniken.

In Zusammenhang mit einem Forschungsprojekt zu Aby Warburg interessiere ich mich für die Unbeständigkeit, dabei noch genauer für die 'Polarität' der Bilder ( Was ein Bild ist, ist dabei Effekt operationalisierter Differenz, Effekt des Umstandes 'gezeichneter Unterscheidungen' oder 'zügiger/ gezogener' Formen. Auch die Inventionen des byzantinischen Bilderstreites lassen bereits erkennen, dass Ikonoklasmus und Bildproduktion zusammen laufen können - deutlich wird das also nicht erst im Suprematismus und nicht erst mit der Idee, dass ein schwarzes Quadrat bestreitet, was eine Ikone sein soll, also ein Bild durch ein Bild ersetzt.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE IMAGES of GODS

In today’s wonderful book there are over Two Hundred 3/4 page woodcuts of gods, from the beginning of Idolatry and from newly (16th century) discovered parts of the heavens and earth. The East and the west, Japan, Mexico. This is truly a encyclopedia forever yon from there pious, to the pagan, from theologian to artisan.. 774J Vincenso Cartari. 1531–1569 A TYOHON, youngest son of Gaea (Earth)…

View On WordPress

#Codex Huitzilopochtli#Codex Vaticanus 3738.#Columbus#Egyptian#Iconography#Japanese gods#Maya gods#Mextico#mythology#pagan gods#Semiotics

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

history of the hebrew bible

—1250-1000 bce israel emerges in the highlands of canaan, holding oral narratives of the pentateuch (abraham, if historical, ca. 1800, moses ca. 1250)

—1050 bce the united monarchy forms. saul's reign ca. 1050. david's ca. 1000. solomon's ca. 960. the latter erects the temple. the first former prophets are summoned

—ca 950 bce the oral narrative of the pentateuch is recorded in hebrew. some scholars name this earliest source the yahwist

—922 bce the kingdoms separate into israel in the north (capital samaria) and judah in the south (capital jerusalem). more former prophets are summoned, as well as the latter and the twelve

—ca 850 bce the so-called elohist source records oral narratives of the pentateuch. they may have access to the yahwist source

—722/21 bce assyria ruins samaria, exiles population. this exile affects prophets from the north such as amos and hosea

—621 bce josiah "finds" a scroll in the temple. this deuteronomist source reifies his reforms

—606 babylon and medes ruin nineveh

—597-596 bce babylon ruins jerusalem, namely, the temple. exiles population. this exile affects prophets from the south such as ezekiel and jeremiah

—ca 550 bce the priestly source, keen on re-membering in the midst of exile, records oral narratives of pentateuch. they made use of earlier written sources (so-called j, e, and d sources). some scholars suggest most, if not all, of the hebrew narrative is in fact recorded in this exile period

—539 bce persia ruins babylon, returns judean exiles, allows for temple to be rebuilt

—520-515 bce the temple rebuilt in jerusalem. this starts the 'second temple period'

—400 bce the torah section of the canon reaches its final form

—336-323 bce alexander the great ruins persia

—312-198 bce ptolemies of egypt reign over judah. the dead sea scrolls are composed ca. 300-100 bce. seleucids conquer jerusalem ca. 198

—200s bce LXX is composed in greek. the prophets section of the canon reaches its final form

—168/167 bce syria reigns over jerusalem. maccabean revolt

—33 ce a rabbi from nazareth with kind eyes hangs on a cross

—40s-60s ce a pharisee falls off a horse, sends letters to house churches (pauline epistles)

—66-70 ce the second temple is destroyed

—60s-110s the four gospels of the second testament are written. a fifth one, named q, may or may not be lost at this time

—100 ce the writings section of the canon reaches its final form

—300-400 ce codex vaticanus and codex sinaiticus composed

—600-900 ce the MT is rendered. hebrew is afforded vowels, finally. aleppo codex and cairo codex composed

#for anon#these are wellhausen's dates and for the record i dont subscribe wholly to any four source hypothesis but for the sake of our final exam#which i hope youre studying for#its good to know these#faq

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sistine Hall of the Vatican Library.

La Sala Sistina della Biblioteca Vaticana.

(English / Español / Italiano)

Built at the behest of Pope Sixtus V in 1587, the room represents the beating heart of the Vatican Library, which was officially established in 1475 but whose origins date back to early Christian times.

The Sistine Hall is an immense gallery about 70 metres long and 15 metres wide, conceived as a single room divided into two parallel naves by a row of Corinthian marble columns. The ceiling is an extraordinary work: frescoed with complex geometric patterns, arabesques and papal heraldic symbols, all framed by an explosion of bright colours.

Apart from its impressive architecture, the Sistine Hall is famous for its original function: to house and make accessible the precious manuscripts and books of the Vatican Library. Some of the most important documents in human history were stored here, including sacred texts, works of philosophy, science, literature and law. Among the most famous treasures are the Codex Vaticanus, one of the oldest biblical manuscripts, and the Vergilius Vaticanus, a 5th century manuscript containing texts by Virgil accompanied by magnificent illustrations.

A little-known element is the technological innovation adopted already in past centuries to preserve the volumes stored in the room. The original shelves were designed to allow optimal air circulation, thus preventing humidity and damage to the manuscripts. Even today, the Vatican Library is at the forefront of conservation, with laboratories dedicated to the restoration and digitisation of ancient texts.

Fun fact: it is said that Michelangelo, while frescoing the Sistine Chapel, also found inspiration in the Vatican's book collections.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Construida a instancias del Papa Sixto V en 1587, la sala representa el corazón palpitante de la Biblioteca Vaticana, creada oficialmente en 1475 pero cuyos orígenes se remontan a los primeros tiempos del cristianismo.

La Sala Sixtina es una inmensa galería de unos 70 metros de largo por 15 de ancho, concebida como una única sala dividida en dos naves paralelas por una hilera de columnas corintias de mármol. El techo es una obra extraordinaria: pintado al fresco con complejos motivos geométricos, arabescos y símbolos heráldicos papales, todo ello enmarcado por una explosión de vivos colores.

Además de por su impresionante arquitectura, la Sala Sixtina es famosa por su función original: almacenar y hacer accesibles los preciosos manuscritos y libros de la Biblioteca Vaticana. Aquí se guardaban algunos de los documentos más importantes de la historia de la humanidad, incluidos textos sagrados, obras de filosofía, ciencia, literatura y derecho. Entre los tesoros más famosos se encuentran el Codex Vaticanus, uno de los manuscritos bíblicos más antiguos, y el Vergilius Vaticanus, un manuscrito del siglo V que contiene textos de Virgilio acompañados de magníficas ilustraciones.

Un elemento poco conocido es la innovación tecnológica adoptada ya en siglos pasados para conservar los volúmenes almacenados en la sala. Las estanterías originales se diseñaron para permitir una circulación óptima del aire, evitando así la humedad y el deterioro de los manuscritos. Aún hoy, la Biblioteca Vaticana está a la vanguardia de la conservación, con laboratorios dedicados a la restauración y digitalización de textos antiguos.

Dato curioso: se dice que Miguel Ángel, mientras pintaba al fresco la Capilla Sixtina, también encontró inspiración en las colecciones de libros del Vaticano.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Costruita per volontà di Papa Sisto V nel 1587, la sala rappresenta il cuore pulsante della Biblioteca Vaticana, istituita ufficialmente nel 1475 ma le cui origini risalgono all’epoca paleocristiana.

La Sala Sistina è un’immensa galleria lunga circa 70 metri e larga 15, concepita come un unico ambiente diviso in due navate parallele da una fila di colonne corinzie in marmo. Il soffitto è un’opera straordinaria: affrescato con complessi motivi geometrici, arabeschi e simboli araldici papali, il tutto incorniciato da un’esplosione di colori vivaci.

Oltre alla sua architettura imponente, la Sala Sistina è famosa per la sua funzione originaria: custodire e rendere accessibili i preziosi manoscritti e libri della Biblioteca Vaticana. Qui erano conservati alcuni tra i documenti più importanti della storia umana, inclusi testi sacri, opere di filosofia, scienza, letteratura e diritto. Tra i tesori più celebri vi sono il Codex Vaticanus, uno dei più antichi manoscritti biblici, e il Vergilius Vaticanus, un manoscritto del V secolo contenente testi di Virgilio accompagnati da magnifiche illustrazioni.

Un elemento poco noto è l’innovazione tecnologica adottata già nei secoli passati per preservare i volumi custoditi nella sala. Gli scaffali originali erano progettati per consentire una circolazione ottimale dell’aria, prevenendo così l’umidità e i danni ai manoscritti. Ancora oggi, la Biblioteca Vaticana è all’avanguardia nella conservazione, con laboratori dedicati al restauro e alla digitalizzazione dei testi antichi.

Curiosità: si dice che Michelangelo, mentre affrescava la Cappella Sistina, trovasse ispirazione anche nelle collezioni librarie del Vaticano.

Source: Curiosando Impari

#renacimiento#renaissance#rinascimento#16th century#s.XVI#sala sistina#biblioteca vaticana#papa sisto V

1 note

·

View note

Text

Why is Matthew 17:21 Not Included?

The Bible is a compilation of diverse books, letters, and teachings that have been passed down through generations. While many parts of the New Testament are consistent across translations, certain verses, like Matthew 17:21, are conspicuously absent from some versions of the Bible. This absence raises important questions about the historical and theological reasons for its omission. Why is Matthew 17:21 not included in many modern Bible translations? Does its exclusion affect the meaning of the Gospel, and what does this say about how the Bible has been transmitted over the centuries?

In this article, we will explore the historical, textual, and theological reasons why Matthew 17:21 is not included in many translations of the Bible, what its original context may have been, and the broader implications for understanding the process of biblical transmission.

Matthew 17:21 and the Textual Issue

To understand why Matthew 17:21 is sometimes omitted, we must first look at the context of the verse itself. Matthew 17:21 is a verse that appears in some versions of the Gospel of Matthew, but not in others. It reads as follows in the King James Version (KJV):

"Howbeit this kind goeth not out but by prayer and fasting." (Matthew 17:21, KJV)

This verse is part of a larger passage in which Jesus' disciples are unable to cast out a demon from a boy who is possessed. When they ask Jesus why they could not perform the exorcism, Jesus responds with the famous words:

“Because of your unbelief…” (Matthew 17:20, KJV)

Then, in the KJV, Matthew 17:21 follows, with the added instruction that some demons can only be cast out through prayer and fasting.

However, this specific verse does not appear in most modern Bible translations, including the New International Version (NIV), the English Standard Version (ESV), and the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV), among others. The key question is: why is this the case?

The Role of Textual Criticism

The absence of Matthew 17:21 in many translations comes down to the field of textual criticism, which seeks to determine the most accurate and reliable text of the Bible based on the oldest and most complete manuscripts available. Textual critics study variations in ancient manuscripts to identify possible alterations, additions, and omissions.

Manuscript Evidence: The earliest Greek manuscripts of the Gospel of Matthew (such as Papyrus 37, Codex Sinaiticus, and Codex Vaticanus) do not include Matthew 17:21. These early manuscripts, which date back to the 4th and 5th centuries, are considered to be some of the most reliable and authoritative witnesses to the text of the New Testament. They are the primary sources that modern Bible translations rely on.

Later Manuscripts: However, later manuscripts, especially those produced in the Byzantine tradition, do include Matthew 17:21. These manuscripts, which were copied from earlier versions during the Middle Ages, contain a number of textual additions and variations, some of which were likely inserted over time by scribes who wanted to harmonize certain passages or provide clarification.

Textual Variants: The fact that Matthew 17:21 appears in some manuscripts but not in others is a prime example of a textual variant—a difference in wording or content found in different copies of the Bible. Textual critics examine these variants to determine which reading is most likely to reflect the original text of the New Testament. In this case, the majority of early manuscripts (and some key later manuscripts) do not contain Matthew 17:21, leading many scholars to conclude that this verse was likely a later addition.

Why Was Matthew 17:21 Added?

While we cannot be absolutely certain about the exact origin of Matthew 17:21, scholars have several theories as to why it might have been added to certain manuscripts of the Gospel.

1. Harmonization with Mark 9:29

One of the most plausible explanations is that Matthew 17:21 was added as a way to harmonize the Gospel of Matthew with the Gospel of Mark. In Mark 9:29, the parallel passage to Matthew 17:21, Jesus says:

“This kind can come out only by prayer.” (Mark 9:29, NIV)

The phrase "prayer and fasting" in Matthew 17:21 may have been introduced by scribes who were familiar with this verse in Mark and sought to add additional detail to the Matthew account, possibly in an effort to harmonize the two Gospels. The inclusion of "fasting" in Matthew 17:21 aligns more closely with other passages in the Gospels that emphasize the importance of fasting in spiritual disciplines (such as in Matthew 6:16-18).

2. Theological Considerations

Another possible reason for the addition of Matthew 17:21 could be theological. Early Christian communities were deeply concerned with the power of prayer and fasting as spiritual tools for overcoming evil forces. The idea that some spiritual battles required a more intense commitment to prayer and fasting was a theme that resonated with the early church.

The Role of Fasting: The combination of prayer and fasting as a means of spiritual preparation or warfare is a concept that appears in other parts of Scripture, particularly in the early church's practices. The inclusion of fasting in Matthew 17:21 may have been intended to provide a fuller teaching on how to confront spiritual challenges, especially in light of the growing influence of ascetic practices in some Christian communities.

3. Transmission and Scribe Variants

The addition of Matthew 17:21 may also be the result of the way texts were transmitted in antiquity. Scribes often sought to clarify or expand upon a passage they were copying, sometimes adding details that they believed would help readers better understand the text. The scribe who inserted Matthew 17:21 may have been influenced by the oral tradition or the liturgical practices of the time, which emphasized the importance of fasting alongside prayer.

Theological Implications of the Omission

While the absence of Matthew 17:21 from many modern translations may seem insignificant at first, it does have some theological implications. The omission of this verse does not change the core message of the passage—that faith in God can overcome even the most difficult challenges—but it does alter the focus on the role of prayer and fasting in spiritual warfare.

Prayer and Fasting as Spiritual Disciplines: The concept of prayer and fasting as a means of spiritual preparation and victory over evil is still supported by other parts of the Bible. For instance, in Matthew 6:16-18, Jesus teaches about fasting as a private act of devotion. Additionally, in the Gospel of Mark and other New Testament writings, prayer is emphasized as a means of accessing God's power and intervention.

Theological Emphasis: While Matthew 17:21 specifically mentions both prayer and fasting, the omission of fasting from the passage does not diminish the biblical teaching on these practices. Instead, it suggests that the early church recognized the importance of both prayer and fasting as distinct disciplines in their own right.

Conclusion: The Importance of Textual Integrity

The question of why Matthew 17:21 is not included in many translations of the Bible is a reflection of the broader discipline of textual criticism, which seeks to preserve the integrity of the biblical text. While the verse itself may not be included in all modern translations, its omission does not affect the core message of the Gospel. The presence or absence of Matthew 17:21 should not detract from the profound truths of the passage: that faith in Jesus can move mountains, and that prayer is a powerful tool in spiritual warfare.

Ultimately, the study of textual variants like Matthew 17:21 highlights the complex history of the Bible’s transmission, and serves as a reminder of the care and diligence involved in preserving the Word of God for future generations. Whether or not Matthew 17:21 is included, the overall message of the Gospel remains unchanged: that through faith in Jesus Christ, believers have access to divine power and victory over evil.

0 notes

Text

El episodio de los cerdos en Gerasa, registrado en los evangelios de Marcos 5:1-20, Mateo 8:28-34, y Lucas 8:26-39, ha generado debate sobre su precisión geográfica. En este relato, Jesús llega a la región de los gerasenos (o gadarenos, según algunos manuscritos) después de cruzar el Mar de Galilea. Al desembarcar, se encuentra con un hombre poseído por demonios. Jesús le pregunta su nombre, y el hombre responde que se llama “Legión”, porque tenía muchos demonios. Jesús expulsa a los demonios, que entran en una piara de cerdos, la cual luego corre cuesta abajo y se arroja al mar, ahogándose. Gerasa, identificada con la moderna Jerash, es una ciudad ubicada en la región de Decápolis, a unos 50 km al sureste del Mar de Galilea. Esta distancia hace imposible que los cerdos hayan corrido desde un acantilado hacia el mar, ya que no hay cuerpo de agua cercano a Gerasa. Gadara, otra ciudad mencionada en algunos manuscritos, es más cercana al Mar de Galilea, pero sigue estando a unos 10-12 km del mar, lo cual también plantea dificultades geográficas. Aunque esta distancia es menor que la de Gerasa, sigue siendo poco probable que los cerdos hayan podido correr desde Gadara hasta el mar. Algunos estudiosos creen que la referencia a “Gerasa” podría ser un error de copistas o una confusión con Gergesa, una ciudad más cercana al mar. Aunque no existe un consenso claro sobre la ubicación exacta de Gergesa, se cree que podría haber estado en las inmediaciones del Mar de Galilea, lo que haría más plausible la historia de los cerdos corriendo hacia el agua. Esta idea es apoyada por Raymond E. Brown, quien menciona que la variación entre “Gerasa” y “Gadara” en los manuscritos indica que los primeros copistas pudieron haber malinterpretado los nombres de las localidades o los escribas no estaban familiarizados con la geografía exacta de la región. Variantes textuales Gerasa: Encontrada principalmente en Marcos 5:1 y Lucas 8:26 en manuscritos antiguos como el Codex Sinaiticus (siglo IV) y el Codex Vaticanus (siglo IV). Gadara: Se menciona en Mateo 8:28, y aparece en manuscritos como el Codex Bezae (soglo V) y el Codex Alexandrinus (siglo V). Gergesa: Una variante tardía que aparece en algunas versiones siríacas y es mencionada por escritores como Eusebio. Traducciones que hoy conocemos Los nombres de estas 3 ciudades están presentes en distintas traducciones de la Biblia que han llegado a nosotros en la actualidad. Gadara: Reina-Valera (1960, 1995), King James Version (KJV), Nueva Versión Internacional (NVI), La Biblia de las Américas (LBLA) (especialmente en Mateo 8:28). Gerasa: Reina-Valera, KJV, NVI, LBLA (en Marcos 5:1 y Lucas 8:26). Gergesa: Se menciona en algunas notas al pie de traducciones como la Biblia de Jerusalén y algunas ediciones de la Dios Habla Hoy, aunque rara vez aparece en el texto principal. También está presente en algunas versiones antiguas como la Peshitta siríaca. Discrepancias entre los evangelios El evangelio de Mateo menciona a dos hombres poseídos, mientras que Marcos y Lucas solo mencionan a uno. Esto ha llevado a algunos estudiosos a concluir que los evangelios se basan en diferentes fuentes o tradiciones orales, lo que podría explicar las variaciones en la narrativa geográfica. La transmisión oral, característica de los primeros tiempos del cristianismo, a menudo llevaba a que los detalles precisos (como los nombres de las ciudades) se modificaran o no fueran consistentes. Bart Ehrman, en su obra “Misquoting Jesus”, discute cómo los errores y las alteraciones en la transmisión textual de los evangelios son comunes, y este episodio puede ser un ejemplo de cómo los nombres de lugares y detalles geográficos pudieron haber sido alterados en la tradición escrita posterior. Aunque se puedan ofrecer muchas explicaciones, claramente los textos no son perfectos. Poniendo atención a los detalles, es posible advertir que tienen errores. Incluso si solo fueran errores de los copistas y no de las tradici...

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

#1100 Does the Vatican have a secret library?

Does the Vatican have a secret library? No. The Vatican doesn’t have a secret library. There are some sections that are restricted, and there are some recent records that are off limits, but no more than many other government libraries and there are certainly some governments that are much more secretive. The Vatican library is enormous. That isn’t really surprising considering that the Roman Catholic church has a history going back over 1500 years. The library has only existed in its present location since 1475, but the Catholic church has owned a library and book collections for much longer than that. The books were kept in many locations, but the center of the church has always been Rome and it made sense to keep all of the books there. It is said to be one of the oldest libraries in the world and it has manuscripts and scrolls going back to the 4th century. The oldest book it has is the Codex Vaticanus, which is a Christian copy of a Greek bible that has been dated to about 325 AD. The library contains over 1.5 million books and manuscripts. 8.600 books that were printed before 1500. It has coins, works of art, antiquities, and a whole range of other things. There are over 100,000 letters from the first half of the 14th century alone! The library is estimated to have over 85 km of shelving! So, is there a secret library? There is a section called the Vatican Apostolic Archive, which has been called the Vatican Secret Archive, but secret doesn’t mean what we think it means. Thanks to Dan Brown and his books, we assume that the Vatican are hiding things from us, but the library is private more than secret. The word “secretum” in Latin means private. It basically contains state papers, correspondence, accounts, and other documents that pertain to the running of the state. However, this section is most certainly not secret and any scholar can view the documents if they like. It is not easy to get permission to go in, but it is not impossible. You need to have a letter of recommendation from a university or a research institution, or a recognized scholar. Then you have to undergo an interview to make sure you are who you say you are and your reasons are true. If you are successful, the Vatican will write to you with permission and the date you can attend. Once you are inside, there are pretty strict rules as well. You are not allowed ink pens or photography equipment. You must wear gloves and the books you have requested are brought to you. You can only request up to five books a day. All of this doesn’t make the archives secret, it just means that the Vatican are doing what they can to protect their collection of ancient books. You would get exactly the same treatment and have to go through the same steps if you requested to see an ancient book in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. There are still some documents that are restricted. The Vatican archives were first opened up in 1881 when Pope Leo XIII was persuaded to open them up to historians. People started to study the documents in depth. Before this, the documents hadn’t really been secret, more restricted. Also, there wasn’t a huge amount of interest in them until probably the end of the 18th century. The study of history was not a common pastime until probably the time of the Industrial Revolution. In 1979 a historian called Carlo Ginzburg requested access to all of the archives of the Roman Inquisition, which was granted. Since then, when somebody wants to see a document, they are generally granted access. The documents that are still restricted are any correspondence or documents related to the current state and pope. Documents are made public 75 years after the end of a pope’s reign, which almost always means their death. This can be waived by other popes and sometimes is. The Vatican Library is a candy shop for historians. When we study history at school, we learn about numerous important events that changed the course of history and many of the documents connected to these events are kept in the Vatican Library! Henry VIII’s request for a marriage annulment, which led to the foundation of the Church of England. The records of the trial of Galileo and the trials of the Knights Templar. The papal bull excommunicating Martin Luther. Correspondence with historical figures, such as Napoleon, and various monarchs. And so many other things that would fascinate any historian. But none of them are secret. And this is what I learned today. Photo by Aliona & Pasha: https://www.pexels.com/photo/aerial-view-of-vatican-city-3892129/ Sources https://www.history.com/news/step-into-the-vaticans-secret-archives https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vatican_Apostolic_Archive https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vatican_Library https://carpediemtours.com/blog/secrets-of-the-vatican-library https://publicmedievalist.com/vatican-secret-archives/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Codex_Vaticanus Read the full article

0 notes

Text

The shorter the time period

The shorter the time period between the date when a document was originally written [the autograph] and the date of its first extant copy [or manuscript], the more reliable a text is considered. For most ancient classics an average of over 1000, up to 1400, years stands between the original work and the date of the earliest existing copy… The textual situation with the New Testament is vastly superior:

John Rylands MS (AD 130)

Bodmer Papyrus II (AD 150-200)

The Diatessaron (c. AD 170)

Chester Beatty Papyri (AD 200)

Codex Sinaiticus (AD 350)

Codex Vaticanus (AD 325-350)

Codex Ephraemi (AD 400)

Codex Alexandrinus (Ad 400)

Codex Bezae Cantabrigiensis (c. AD 450)

~ Samples, Kenneth Richard. ‘Without a Doubt: Answering the 20 Toughest Faith Questions.; p. 93, 94

1 note

·

View note

Text

THE IMAGES of GODS

In today’s wonderful book there are over Two Hundred 3/4 page woodcuts of gods, from the beginning of Idolatry and from newly (16th century) discovered parts of the heavens and earth. The East and the west, Japan, Mexico. This is truly a encyclopedia forever yon from there pious, to the pagan, from theologian to artisan.. 774J Vincenso Cartari. 1531–1569 A TYOHON, youngest son of Gaea (Earth)…

View On WordPress

#Codex Huitzilopochtli#Codex Vaticanus 3738.#Columbus#Egyptian#Iconography#Japanese gods#Maya gods#Mextico#mythology#pagan gods#Semiotics

0 notes

Text

Codex Vaticanus B & Codex Borgia

is a pre-Columbian Middle American pictorial manuscript, with a ritual and calendrical content.

0 notes

Photo

The Borgia Group is the scholarly designation of number of mostly pre-Columbian documents from central Mexico. In 1830–1831, they were first published in their entirety as colored lithographs of copies made by an Italian artist, Agustino Aglio, in volumes 2 and 3 of Lord Kingsborough's monumental work titled Antiquities of Mexico. They were named the “Codex Borgia Group” by Eduard Seler, who in 1887 began publishing a series of important elucidations of their contents.

The main members of the Borgia Group are:

The Codex Borgia, after which the group is named. The codex is itself named after Cardinal Stefano Borgia, who owned it before it was acquired by the Vatican Library,

The Codex Cospi,

The Codex Fejérváry-Mayer,

The Codex Laud,

The Codex Vaticanus B.

Also sometimes included are:

The Aubin Manuscript No. 20, or Fonds mexicain 20,

The Codex Porfirio Díaz.

v

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

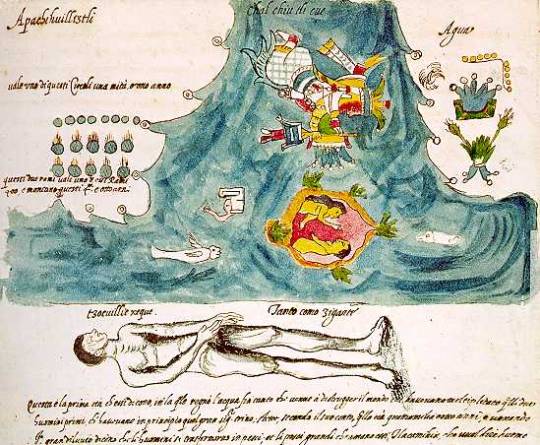

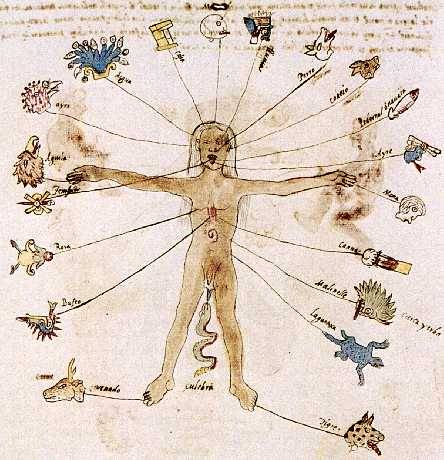

The Codex Vaticanus A / Codex Rios is an adaptation of the Codex Telleriano-Remensis, a colonial Spanish manuscript, translated into Italian with annotations by a Dominican friar working in Oaxaca, Mexico. The manuscript was likely created in Italy after AD 1566 and recounts the history of Tolteca-Chichimeca culture from AD 1195 - 1549.

Top, page 4. "The first age in Mexican cosmogony ended with a great flood when the water deity descended to earth. Men were changed into fish, but one couple managed to escape the deluge. During this age, giants lived on earth (here, the large reclining body).“

Bottom, page 54: Signs representing the twenty days of the ritual calendar are linked to a part of the body.

#codex rios#colonial mexico#codex vaticanus a#codex telleriano-remensis#codex#rios#vaticanus a#toltec#chichimeca#telleriano-remensis#mexico

173 notes

·

View notes