#Codex Huitzilopochtli

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

THE IMAGES of GODS

In today’s wonderful book there are over Two Hundred 3/4 page woodcuts of gods, from the beginning of Idolatry and from newly (16th century) discovered parts of the heavens and earth. The East and the west, Japan, Mexico. This is truly a encyclopedia forever yon from there pious, to the pagan, from theologian to artisan.. 774J Vincenso Cartari. 1531–1569 A TYOHON, youngest son of Gaea (Earth)…

View On WordPress

#Codex Huitzilopochtli#Codex Vaticanus 3738.#Columbus#Egyptian#Iconography#Japanese gods#Maya gods#Mextico#mythology#pagan gods#Semiotics

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm going to be not normal about huitzilopotchli on the not being normal about things website

because he was BORN to protect his mother from his own sister. his birth is an act of protection, and he fails to save BOTH of them, his mother becoming a two-headed snake monster, his sister leading an army against him, made of his own brothers and sisters. when he has to kill them all, they become the stars in the sky, and his sister the moon, and every night he has to fight their angry, dead bodies through the night sky, led by a dog he doesn't know is the closest thing he has anymore to a brother. and one day he will fail and the world knows he's going to lose this fight one day and when it does they will all die and he just has to live with that. they have to love him anyway, give their own flesh and blood anyway

like he leads the people of mexico to lake texcoco. he clearly loves the people. not as much as quetzalcoatl but he does

like who's gonna write the book??? do i have to do it??? will it be me????

#aztec gods#aztec mythology#huitzilopochtli#mesoamerica#dont make me write it#also read the codex florentine its free#and super cool#i love the mexica

47 notes

·

View notes

Text

The idea of Olrox being from Cholula specifically makes me so insane. Like would he have identified more as Mexica? Or as Tlaxcaltec? Would he have been loyal to the Tlaxcaltec and allied with the Spanish only to get screwed over like his Mohican lover did in the colonies? Would he have done so thinking he could get the upper hand in the end just like Mizrak/Emmanuel thought the Order could with Erzsebet?

"He thinks the devils he manufactures will be enough to destroy her when the time comes. What do you think? Do you think he's right?" - S1E4

Even after the fall of Tenochtitlan, nobility from all over the region would have been sent to Cholula to get the blessing of Cholulan priests for their legitimacy. How might this have fueled his disdain for nobility?

Olrox: "I prefer my blood blue."

Drolta: "Maybe you do things differently in the new world, but over here we don't feed off the wealthy. The locals will start to grumble." - S1E5

As a Mexica citizen, this disdain could come from resentment toward sumptuary laws, the increasing lack of socioeconomic mobility during Moctezuma's rule, and frustration with how he handled the Spanish... But as a Cholulan sympathetic to Tlaxcala, there's so much more???

It could come from frustration with leadership that defected from the very people who helped them elude Mexica rule in the years before the Spanish conquest. Anger at a decision that economically obliterated the Tlaxcaltec, who became completely surrounded by Mexica member-states? Regret at how much it cost them to 'overthrow' the Mexica? Grief at how this kind of political/military opportunism helped lead the wider indigenous population to its demise?? Like the latter is so much more thematically ripe for a show tackling colonialism and imperialism imo???

"This one? He was just an opportunist, following the Messiah because she's powerful." - S1E4

I mean!!?? Think about how the implications of all of this... *gestures wildly* stuff would lead him to adopt such a cynical, morally ambiguous worldview? This sense that it's all doomed, that he's not strong enough to fight it? Resist and fall to your enemies, or work with them only to lose parts of your identity in the process? Think about how the brutality of the Cholula massacre recontextualizes eurocentric perceptions of the brutality of flower wars and ritual sacrifice??? How it would leave you with anger and pain and an unyielding need for justice?

"Little boy Belmont. I know that feeling. That pain, that hate, that burning, unendurable need for retribution." - S1E1

Think about how the Mexica Empire had adopted Huitzilopochtli (war, sacrifice) as their primary patron deity, and the Tlaxcaltec Mixcoatl/Camaxtli (the hunt, fire)... Yet Olrox's form seems to be based on Quetzalcoatl (wind, knowledge, rebirth, among other things)–the deity the great temple at Cholula was dedicated to.

A handful of mesoamerican deities are associated with serpents/have names ending in '-coatl', but Olrox's serpent form clearly has a feathered crest—the 'quetzal-' in Quetzalcoatl.

But Olrox's abilities also seem to include lightning/thunder, which are associated with Tlaloc, who the Cholulans seemed to have adopted as their central deity some time before the Spanish conquest.

Quetzalcoatl is only associated with storms sort of tangentially, through his aspect as the wind god, Ehecatl. The Florentine Codex refers to Quetzalcoatl-Ehecatl as sweeping the roads to make way for the rain and the thunder.

Think about how in Tlaxcaltec accounts, Cholula–being a sacred city–had no real military to speak of and depended on their gods to protect them???

Mizrak: "There's only one God. Just one. That's the only thing I'm sure of. And I've spent my whole life serving him, fighting for him. That hasn't changed, and it never will." Olrox: "One god... And you think he can protect you?" - S1E4

Like... What does it all mean???? 🫠🫠🫠

Agshsjdkdkfll *screams into a pillow* I am so excited for season 2 but whatever happens Cholulan Olrox is canon in my heart y'all

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

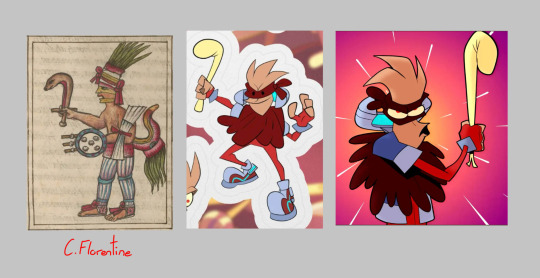

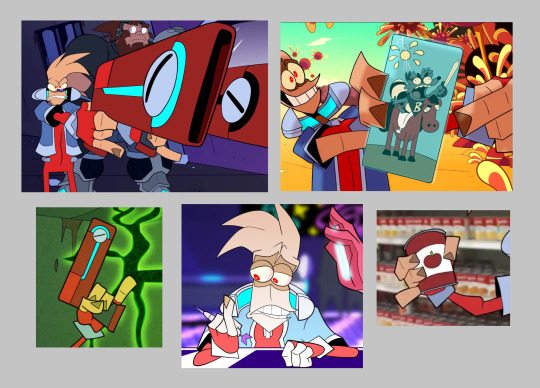

Shrike as Huitzilopochtli... 2!

Ah shit. Here we go again. This time with some more facts (and some corrections lol)

Huitzilopochtli, “Hummingbird of the South”, is the patron god of the Mexica (historically called the Aztecs). He was the patron of the capital city of the Aztec empire, Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City). He was the god of warfare and the sun, as the sun of the fifth and current era.

We'll start with the iconography, and then possible themes

—

Huitzi is nearly always represented with quetzal feathers (quetzalli) on his headdress, a lot of gods in the pantheon have them (In my last post I called them hummingbird feathers but those are the ones on his back. Whoops!). These appear in Shrike’s design as the spikes of his tentacles.

Huitzilopochtli is most known for having a black mask around his eyes. Shrike has dark circles around his eyes. His namesake, shrike, is a bird also known for having a mask of black feathers around its eyes. Additionally, when he’s dressed up as Bandito in ep2, he puts on a dark antiface. And as a potential extra layer, this is to imitate the black masks that raccoons also have.

Huitzi is called the "hummingbird of the south", and so he wears the head of a hummingbird on top of his own. The Aztecs also believed that warriors who died in battle got reincarnated into hummingbirds, so that’s another connection to warfare. Shrike has a beak-like mouth that has visibly been getting longer throughout the episodes.

The god has a pectoral circle made of seashell on his chest (anahuatl). I’m not entirely sure if the collar of his jacket is supposed to be a reference to this. In his reference sheet it’s a circle, various animators draw it as a circle, but Zeurel never draws it as a circle when animating, so it might be a stretch.

Huitzi commonly carries Xiuhcoatl, the “Turquoise Serpent”, as a weapon, mentioned in the story of his birth in the Florentine Codex. When dressed up as Bandito, Shrike grabs one of the floppy leaves of the plant, resembling the shape of the snake.

But Xiuhcoatl can also be found on the pattern on the sides of his shoes!

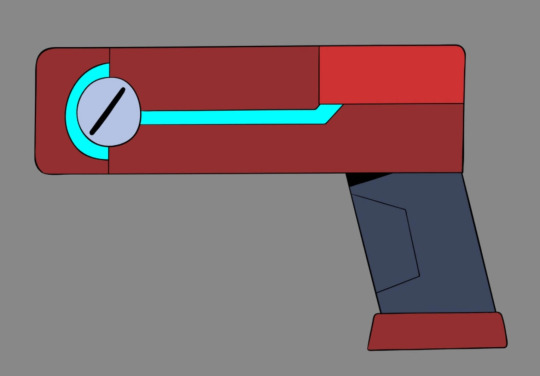

Also mentioned in his origin story in Florentine, he has a xiuh atlatl, a “turquoise dart thrower” (although it can also be associated with Xiuhcoatl as the same thing).

That would be his gun. It’s not the only time that guns are gonna be compared to dart throwers.

—

Huitzilopochtli was the sun of the fifth era to the Mexica. This sun has the symbol “Nahui Ollin”, which means “4 Movement”. The Ollin is one of the Aztec calendar day signs, it means “movement” or “earthquake”, and it is represented as two intertwined lines. Here it is represented in Codex Borgia.

Now here’s what I’m thinking

This might just be where Shrike’s pinky quirk comes from! Shrike was the one to tell Beebs about pinky promises, and they seem to be very important to him. So much so that he subconsciously keeps his pinkies up whenever he’s holding his guns or his phone.

The reason why each era has a name and symbol attributed to it is because they’re named after the way it would end. This fifth era is named after earthquakes because the Aztecs believed that this world would end with strong tremors, the sun would lose its perpetual fight against darkness, and the stars would come down to earth in the form of creatures called Tzitzimime to kill all of humanity.

This god represents the sun. The sun in the solar system. Earth’s sun, our sun, the Terrans’ sun. Yeah, that sun.

The sun’s job was to illuminate the world for us humans, and to not let it fall into darkness. This could be why Shrike has a fear of the dark, and has such appreciation for Terrans!

Shrike, as the protagonist of the show, is Huitzilopochtli, the god most important to the Mexica. Zeurel currently doesn't have a specific nationality for him, he's generally hispanic, but the crew's Spanish consultant is Mexican, and so is Sr. Pelo, the voice of Bandito. In Bandito's show there are curtains with the colors of the Mexican flag and a prickly pear cactus, which appears in the coat of arms in the middle of said flag.

This symbol actually comes from the legend on the origins of Tenochtitlan! Huitzilopochtli told the Mexica to leave Aztlan, the place where they were originally from (that's where the term "Aztec" comes from). He told them to build a new city where they found an eagle perched on a prickly pear cactus, devouring a snake. That was in the middle of lake Texcoco, where Mexico City still stands on today.

I'd say Shrike is the one who has the strongest connection to his past life memories because he feels a strong connection to Mexican culture and language (if he spoke ancient Nahuatl it'd be too obvious so they made him speak Mexican Spanish instead). He also has the habit of calling everyone “amigo”, even to the people he dislikes or doesn’t seem to know at all.

Maybe it’s because he did know them. A long time ago?

Character list

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

“As above, so below, as within, so without, as the universe, so the soul…” ― Hermes Trismegistus Quetzalcoatl Talon Abraxas Quetzalcoatl: The Feathered Serpent’s Myth & History A ubiquitous Mesoamerican deity occupying space in both the Aztec and Mayan pantheons, the feathered serpent was known by two primary names. Quetzalcoatl, the Aztec name, comes from the Nahuatl language, combining quetzal, a species of brightly feathered bird, and coatl, “snake.” The Mayan name, Kukulkan, is derived from the Yucatec Maya dialect, combining kukul, feathered, and kan, which was used for both “sky” and “snake.” In Mayan iconography, the snake is associated with life above and below the earth, pictured alternately in myth as a snake boy who grew too large and had to be hidden in a cave, and a winged serpent that flew too close to the sun and became the sun’s pet. Beyond these stories, little is known about the Mayan Kukulkan, though his existence supports the theory that the feathered serpent motif is much older than either the Maya or the Aztec, likely dating to the much earlier Olmec civilization (1600–400 BCE). During what is generally referred to as the Formative period, Olmec and Mayan territories overlapped in the highlands of Guatemala, where Mayans continue to live to this day. Much of what is known today of pre- and immediate-post-colonial Mesoamerican civilizations comes from extant written records, known as codices. The Aztec and Mayan codices were screenfold manuscripts, painted on front and back, made either of leather or the bark of various trees. The oldest known Mayan codex (Dresden) dates from around 1200 CE, though it may be a copy of an earlier book. Others, such as the Aztec codices, are more recent, often bearing the signs of Spanish influence, which calls their veracity into question. While examples of pre-conquest Mayan and Mixtec codices are known to exist, very few—as many as five, but as few as one—can be attributed to the Aztecs. Though more are known to have been written, some fell victim to the hot damp environment of the jungle, while others were burned by Catholic priests. In addition to information about the astronomy of Aztec and Mayan civilizations, the codices provide a clear picture, literally, of their creation myths. The Aztec myth begins with the old god Ometoltl (from ome, “dual” and teotl, “divine”), a creator deity whose dual aspects resulted in the binary Ometecuhtli (male) and Omecihuatl (female) deities. Interestingly, little attention seems to have been paid to these creator deities and no temples were dedicated to them, since it was believed that people communicated not through them but through their four sons: Huitzilopochtli, Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, and Xipe Totec.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

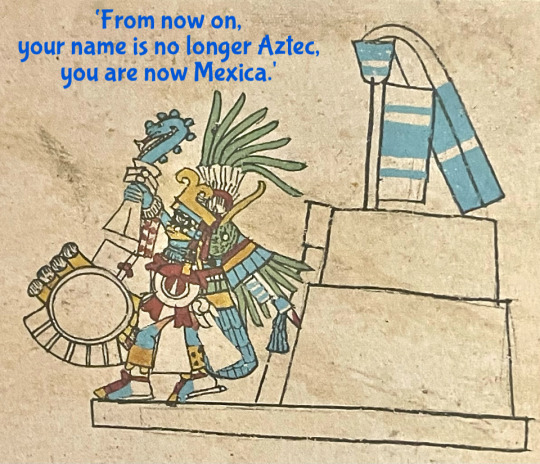

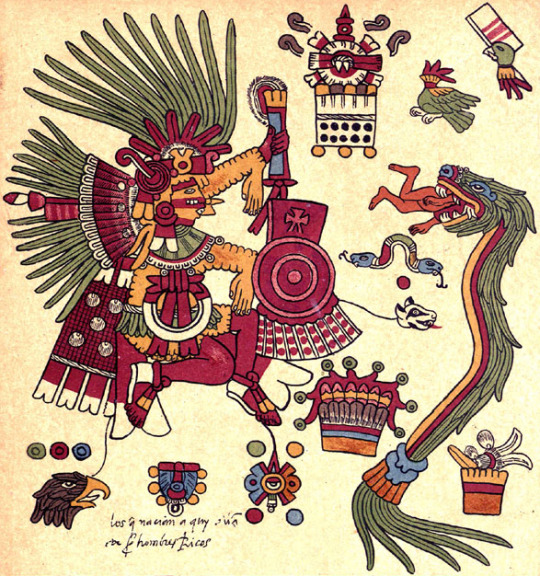

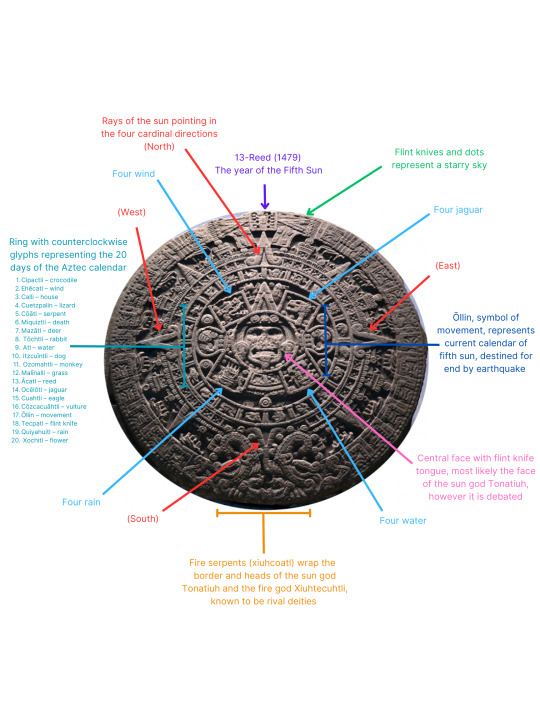

Huitzilopochtli,

patron of the Mexica

"And Huitzilopochtli said to them,

'Take what is among the cacti. They will be the first tribute! And at once there, he changed the name of the Aztecs. He said to them, 'From now on, your name is no longer Aztec, you are now Mexica!

There he painted their ears black; in this way the Mexica took their name.

And there they were given the arrow and the bow and the little net.

Whatever flew overhead, the Mexica shot them well with bows and arrows.

Photo: Codex Borbonicus

Text: Codex Azcatitlan

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

And they also had great respect for Tezcatlipoca, who was believed to have the power to mediate between the gods and the people. Tezcatlipoca was known as the ‘smoking mirror,’ and was associated with the night sky and the stars. He was believed to have the power to see all things, to know all things, and to control the destinies of men. Tezcatlipoca was often invoked in times of war and other crises, as he was believed to have the power to protect the people and to ensure their victory.” Source: Florentine Codex

Tezcatlipoca – Mythopedia

A key element of Tezcatlipoca's power was his omnipresence. He was often represented by an obsidian mirror, though his power extended far beyond obsidian. Any reflection was a portal through which he could view the world.

Pronounced 'Tez-cah-tlee-poh-ka', Tezcatlipoca is the god of night and rival of Huitzilopochtli. His name means 'smoking mirror'. He's often depicted as carrying an obsidian mirror. Aztecs believed Tezcatlipoca and Huitzilopochtli created the world.

Tezcatlipoca was a god of mystery and magic, who could shape-shift into various animal forms and wield great power over the forces of nature.

Image: Aztec God Tezcatlipoca by Mahaboka

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

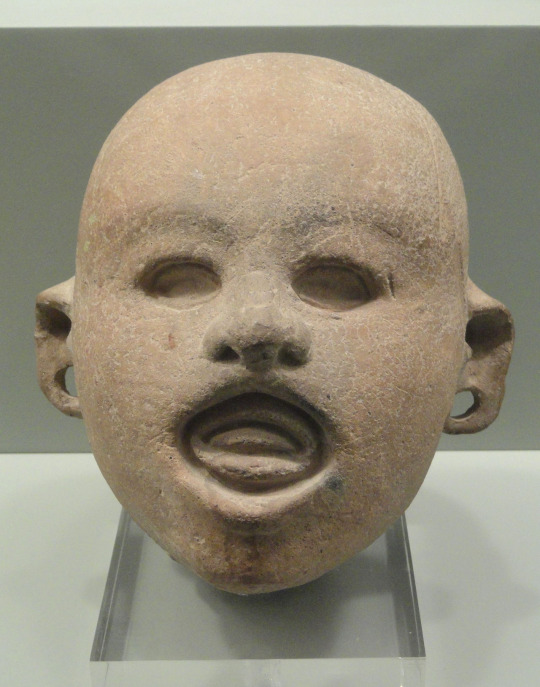

The Flayed God Xipe Totec

“[Tlacaxipehualiztli] was celebrated in the second month of the Aztec year, which corresponded to the last days of February and the early part of March. The exact day of the festival was the twentieth of March, according to one pious chronicler [Diego Duran], who notes with unction that the bloody rite fell only one day later than the feast which Holy Church solemnizes in honour of the glorious St. Joseph. The god whom the Aztecs worshipped in this strange fashion was named Xipe, ‘the Flayed One,’ or Totec, ‘Our Lord’ [i.e., Xipe Totec]. On this occasion he also bore the solemn name of Youallauan, ‘He who drinks in the Night.’ His image was of stone and represented him in human form with his mouth open as if in the act of speaking; his body was painted yellow on the one side and drab on the other; he wore the skin of a flayed man over his own, with the hands of the victim dangling at his wrists. On his head he had a hood of various colours, and about his loins a green petticoat reaching to his knees with a fringe of small shells. In his two hands he grasped a rattle like the head of a poppy with the seeds in it; while on his left arm he supported a yellow shield with a red rim.

Xipe Totec, pictured in the Codex Borbonicus.

(Source: Codex Borbonicus, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

“At his festival the Mexicans killed all the prisoners they had taken in war, men, women, and children. The number of the victims was very great. A Spanish historian of the sixteenth century [Diego Duran, pp. 147-8] estimated that in Mexico more people used to be sacrificed on the altar than died a natural death. All who were sacrificed to Xipe, ‘the Flayed God,’ were themselves flayed, and men who had made a special vow to the god put on the skins of the human victims and went about the city in that guise for twenty days, being everywhere welcomed and revered as living images of the deity. Forty days before the festival, according to the historian Duran, they chose a man to personate the god, clothed him in all the insignia of the divinity, and led him about in public, doing him as much reverence all these days as if he had really been what he pretended to be. Moreover, every parish of the capital did the same; each of them had its own temple and appointed its own human representative of the deity, who received the homage and worship of the parishioners for the forty days.

Earthenware representation of Xipe Totec wearing a mask of flayed human skin (Aztec, c. 1428-1521 CE; found in Mexico, now in the Gardiner Museum, Toronto).

(Source: Daderot, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons)

“On the day of the festival these mortal gods and all the other prisoners, with the exception of a few who were reserved for a different death, were killed in the usual way. The scene of the slaughter was the platform on the summit of the god Huitzilopochtli's temple. Some of the poor wretches fainted when they came to the foot of the steps and had to be dragged up the long staircase by the hair of their heads. Arrived at the summit they were slaughtered one by one on the sacrificial stone by the high priest, who cut open their breasts, tore out their hearts, and held them up to the sun, in order to feed the great luminary with these bleeding relics. Then the bodies were sent rolling down the staircase, clattering and turning over and over like gourds as they bumped from step to step till they reached the bottom. There they were received by other priests, or rather human butchers, who with a dexterity acquired by practice slit the back of each body from the nape of the neck to the heels and peeled off the whole skin in a single piece as neatly as if it had been a sheepskin. The skinless body was then fetched away by its owner, that is, by the man who had captured the prisoner in war. He took it home with him, carved it, sent one of the thighs to the king, and other joints to friends, or invited them to come and feast on the carcase in his house.

Ruins of the Templo Mayor in Mexico City.

(Source: AlejandroLinaresGarcia, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

“The skins of the human victims were also a perquisite of their captors, and were lent or hired out by them to men who had made a vow of going about clad in the hides for twenty days. Such men clothed in the reeking skins of the butchered prisoners were called Xixipeme or Tototectin after the god Xipe or Totec, whose living image they were esteemed and whose costume they wore. Among the devotees who bound themselves to this pious exercise were persons who suffered from loathsome skin diseases, such as smallpox, abscesses, and the itch; and among them there was a fair sprinkling of debauchees, who had drunk themselves nearly blind and hoped to recover the use of their precious eyes by parading for a month in this curious mantle. Thus arrayed, they went from house to house throughout the city, entering everywhere and asking alms for the love of God. On entering a house each of these reverend palmers was made to sit on a heap of leaves; festoons of maize and wreaths of flowers were placed round his body; and he was given wine to drink and cakes to eat. And when a mother saw one of these filthy but sanctified ruffians passing along the street, she would run to him with her infant and put it in his arms that he might bless it, which he did with unction, receiving an alms from the happy mother in return. The earnings of these begging-friars on their rounds were sometimes considerable, for the rich people rewarded them handsomely. Whatever they were, the collectors paid them in to the owners of the skins, who thus made a profit by hiring out these valuable articles of property. Every night the wearers of the skins deposited them in the temple and fetched them again next morning when they set out on their rounds.

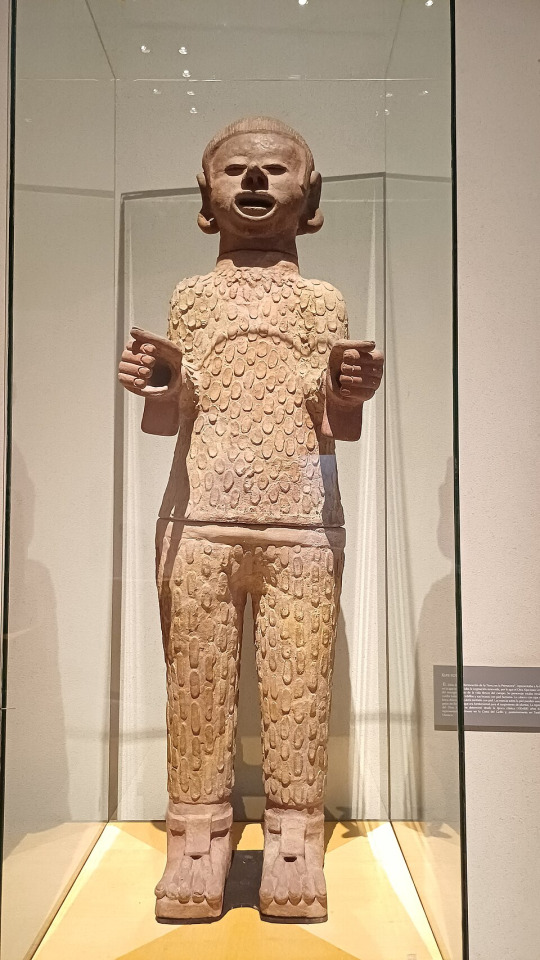

Statue of Xipe Totec clad in flayed human skin (National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico).

(Source: José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

“At the end of the twenty days the skins were dry, hard, shrivelled and shrunken, and they smelt so villainously that people held their noses when they met the holy beggars arrayed in their fetid mantles. The time being come to rid themselves of these encumbrances, the devotees walked in solemn procession, wearing the rotten skins and stinking like dead dogs, to the temple called Yopico, where they stripped themselves of the hides and plunged them into a tub or vat, after which they washed and scrubbed themselves thoroughly, while their friends smacked their bare bodies loudly with wet hands in order to squeeze out the human grease with which they were saturated. Finally, the skins were solemnly buried, as holy relics, in a vault of the temple. The burial service was accompanied by chanting and attended by the whole people; and when it was over, one of the high dignitaries preached a sermon to the assembled congregation, in which he dwelt with pathetic [1] eloquence on the meanness and misery of human existence and exhorted his hearers to lead a sober and quiet life, to cultivate the virtues of reverence, modesty, humility and obedience, to be kind and charitable to the poor and to strangers; he warned them against the sins of robbery, fornication, adultery, and covetousness; and kindling with the glow of his oratory, he passionately admonished, entreated, and implored all who heard him to choose the good and shun the evil, drawing a dreadful picture of the ills that would overtake the wicked here and hereafter, while he painted in alluring colours the bliss in store for the righteous and the rewards they might expect to receive at the hands of the deity in the life to come.

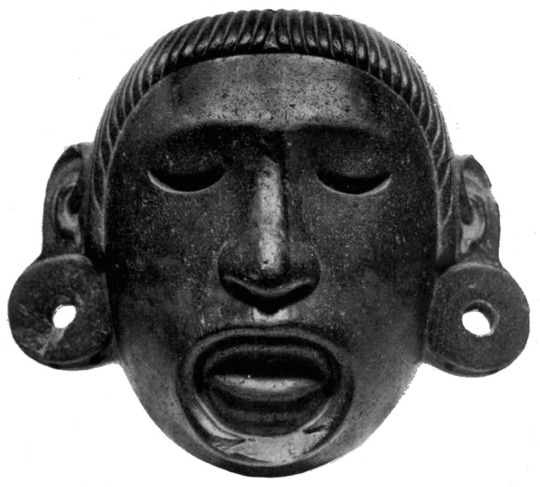

Stone mask of Xipe Totec, included as an illustration in Mexican Archæology (G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1914), by T. A. Joyce (see plate IV).

(Source: T. A. Joyce, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

“While most of the men who masqueraded in the skins of the human victims appear to have personated the Flayed God Xipe, whose name they bore in the form Xixipeme, others assumed the ornaments and bore the names of other Mexican deities, such as Huitzilopochtli and Quetzalcoatl; the ceremony of investing them with the skins and the insignia of divinity was called netcotoquiliztli, which means ‘to think themselves gods.’ Amongst the gods thus personated was Totec. His human representative wore, over the skin of the flayed man, all the splendid trappings of the deity. On his head was placed a curious crown decorated with rich feathers. A golden crescent dangled from his nose, golden earrings from his ears, and a necklace of hammered gold encircled his neck. His feet were shod in red shoes decorated with quail's feathers; his loins were begirt with a petticoat of gorgeous plumage; and on his back three small paper flags fluttered and rustled in the wind. In his left hand he carried a golden shield and in his right a rattle, which he shook and rattled as he walked with a majestic dancing step. Seats were always prepared for this human god; and when he sat down, they offered him a paste made of uncooked maize-flour. Also they presented to him little bunches of cobs of maize chosen from the seed-corn; and he received as offerings the first fruits and the first flowers of the season.”

—J. G. Frazer, The Scapegoat (The Golden Bough, vol. IX, 1913, p. 296-300)

Earthenware statue of one of Xipe Totec's impersonators, executed by an unknown artist in the Remojadas style (c. 600-900 CE; found in Veracruz, today in the Walters Art Museum at Baltimore, MD, USA).

(Source: Walters Art Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

[1] Frazer, whose prose was most influenced by 18th century writers like Joseph Addison and Edward Gibbon, [2] here uses the word “pathetic” in its more archaic sense: he means that the eloquence of the dignitary was emotionally affecting, not that it was sad or pitiful.

[2] Robert Ackerman, J. G. Frazer: His Life & Work (Cambridge, 1987), p. 23.

#jg frazer#the golden bough#the golden bough vol ix#xipe totec#aztecs#aztec mythology#aztec religion#gods#human sacrifice#religious practices#flaying#ancient mexico

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Brief Analysis on the flags of Medieval Two Total War #1

Introduction and Aztecs | Part 02

Aztecs

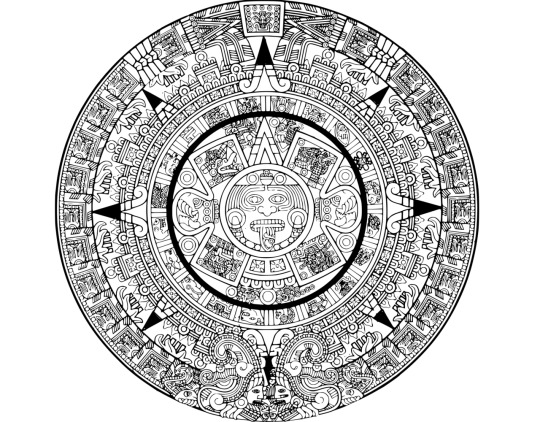

In-Game Symbol

This one had me a bit confused, as I couldn’t figure out 100% what it’s depicted due to the low resolution of the game. Though I think it’s the Sun/Calendar Stone. As the name suggests, it’s a monolithic calendar constructed during the reign of Moctezuma II (1500s-1520). It was found in 1790, under the Zócalo square of Mexico City, at the ruins of the Main Temple of Tenōchtitlan, dedicated to Huitzilopochtli the war god and Tlaloc the rain god. At the centre a deity is depicted, thought to be Tōnatiuh the Sun Deity of daytime Sky. On the aligning circles are carved various symbols representing the eras, centuries and days of the Aztec calendar as well as the four points on the horizon, Moctezuma’s name and two fire serpents. It is debated whether it was used solely as a calendar or as a sacrificial altar.

(Images from Wikipedia)

📜 Historicity 📜

This flag is fictional but inspired by historical elements. The yellow colour for one of the Sun deities is fitting as well as the turquoise colour, which is matching with Tōnatiuh’s epithet of “Turquoise Lord”. Tōnatiuh was one of the most prominent deities of the Aztecs –as well as of other Mesoamerican cultures. The use of the entirety of the sunstone was what confused me the most. As far as I know, the American people and their rulers didn’t use flags, but of course one had to be made for the game. According to Wikipedia, the Aztecs used banners with intricate designs, called Pāmitl in Nahuatl to represent officers and important warriors on the battlefield. Those banners are indeed present in-game and appear on the backs of certain units.

(Pāmitl as depicted on the Codex Mendoza-1540s)

(Pāmitl used by in-game units)

☝️🤓 My humble suggestion ☝️🤓

Although, I think I can understand the reasoning behind it, I believe that this flag can be improved. We can keep the Sun elements with the original colours, but the Sun Stone could be replaced with a depiction of Tōnatiuh, or perhaps another sun deity like Huitzilopochtli. Or since gods’ depictions are very detail and something simpler would be more practical, we can put an animal ascosiated with the sun. Like an eagle, as these birds are associated with Huitzilopochtli. In Aztec mythology eagles were present when the sun was created, as well in Tenōchtitlan’s founding myth, the Aztecs decided to build their city on the place where an eagle landed and ate a snake. The eagle was believed to have been Huitzilopochtli. Let’s not forget that this scene is depicted in Mexico’s coat of arms. An alternative could be the hummingbird, another bird linked with Huitzilopochtli that has some supernatural properties of its own. It was believed that hummingbirds were the reincarnation of fallen warriors. One last suggestion would be the jaguar, an animal associated with the creator god Tēzcatlīpohca and represented military might.

(Tōnatiuh as depicted in Codex Borgia- 16th c.)

(Huitzilopochtli as depicted in Codex Telleriano-Remensis-After 1542)

(Codex Mendoza)

(Aztec Spirit Bird from Mexico City, Jorge Enciso-1947)

(Hummingbird, Codex Mendoza)

(Jaguar depicted in Codex Magliabechiano-16th c.)

Sources

#history#long post#total war#medieval#medieval 2 total war#vexilology#mini ramble#flags#aztec culture#aztec mythology#aztec gods#mesoamerica#mexican history

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE IMAGES of GODS

In today’s wonderful book there are over Two Hundred 3/4 page woodcuts of gods, from the beginning of Idolatry and from newly (16th century) discovered parts of the heavens and earth. The East and the west, Japan, Mexico. This is truly a encyclopedia forever yon from there pious, to the pagan, from theologian to artisan.. 774J Vincenso Cartari. 1531–1569 A TYOHON, youngest son of Gaea (Earth)…

View On WordPress

#Codex Huitzilopochtli#Codex Vaticanus 3738.#Columbus#Egyptian#Iconography#Japanese gods#Maya gods#Mextico#mythology#pagan gods#Semiotics

0 notes

Text

The Mesoamerican Sun/War God

Depiction of Tonatiuh from the Codex Borgia.

The image of a still beating heart being presented to the sun on an Aztec pyramid might not reflect reality (beheading was more common), but it is true that the Mexica sun god, Huitzilopochtli, was conceived as a warrior deity demanding sacrifices to keep his war against nocturnal evil gods.

At first, I thought that this sun/war combo was exclusive to the Aztec. After all, the Mexica were relatively late newcomers to Mesoamerica, so their patron god would have stand out as unique. Yet, the more I searched this rabbit hole, the more the idea of a pan-Mesoamerican war/sun deity began to form:

Tonatiuh, the sun god of the Mixtecs, was a warrior deity associated with eagles (Catillo 2008), much like the replacing Huitzilopochtli.

Curicaueri, the Tarascan/Purepecha sun god, was similarly a warrior god associated with eagles.(Torres 2005)

Copijcha, the Zapotec sun god, was also a warrior deity. This in particular is noticeable given the seniority of the Zapotecs compared to these other cultures, and how their domain is located to the south of them.

Just about the only exception to this seems to be the Mayan sun god, K’inich Ahau, which was more of a healing deity. So rather than an Aztec invention, the sun/war god seems to have a deep history in Mesoamerica. Thus Huitzilopochtli’s attributes match those of a long established tradition, which makes one wonder if he changed once the Mexica became established as an empire, or if this aspect was once more widespread across the Americas and we simply haven’t detected it well enough.

Food for thought.

References

Diaz del Castillo, Bernal (2008). Carrasco, David (ed.). The History of the Conquest of New Spain. Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. p. 469. ISBN 978-0826342874.

González Torres, Yólotl (2005). Diccionario de mitología y religión de Mesoamérica (1. Aufl., 11. reimpr ed.). Madrid: Larousse. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-970-607-802-5.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Have you heard of the canonical/ingame xbalanque x xiuhcoatl genderswap fanfic writing group yet

You ask me THAT? You ask the Xiuhcoatl's simp that scoured every crumbs of his mention in the game??? Of course I do.

Personally, I don't agree with the ship, but why do they have to heterofy it😒 If they want to ship them so bad, at least commit to it and make it a DOOMED (and optional: toxic) YAOI as God intended😤✊️

But if you want to hear my copium-riddled brain's opinion... it actually makes sense. Not that Xiuhcoatl is actually female, but in a way, he also embodied femininity.

(TW: Mentions of pregnancy. Nothing graphic though.)

Take a look at other confirmed sovereigns:

• Neuvillette: He's pretty feminine, actually. Not just in appearance (long hair with a bow tie, superb eyelashes, his name having -ette, a feminine suffix, etc,) but also in narrative. He's regarded as the father of the melusine, and his love for them are nurturing, almost maternal-like. He forgave the Fontainians and made them into real humans with real blood, almost like pregnancy turning an embrio into a real flesh and blood. He also has a Persephone theme going on:

He's the Persephone to Focalors' Hades, who tricked him to dwell in Fontaine (the Netherworld) and care for the Fontainians. He's also the Heart of the Primordial Sea, the sea that birthed Teyvat's original lifeforms.

And his sourcewater droplets have dna-looking thing in them, almost like an egg cell/ovum:

So yeah, Neuvillette is MOTHERING😤

• Apep: The dragon has female voice. 'Nuf said/j. But joking aside, she indeed have many life-giving aspect of motherhood:

Elemental lifeforms were born and nurtured inside her, and she planned to release her "children" after they matured... this is literally pregnancy. Warden of Oasis Prime, her immune system's second boss form holds an embrio, in a pose almost like a mother holding her child:

And it's attacks are littered with DNA imagery:

So yeah, Xiuhcoatl being feminine isn't far-fetched. In fact, I expect him to be so. It seems Sovereigns act as the life-giving forces of the original world, and Xiuhcoatl is no exception. The fanfic writers probably catch his feminine side and run along with it.

Plus, if he's the one who created Huitzilopochtli, that's actually pretty cool. Because not only it reversed his position as Huitzilopochtli's weapon in the myth, he also embodied two important female figures in Huitzilopochtli's life:

• Huitzilopochtli's mother (if we go by Codex Florentine), Coatlicue. She has many snake imageries, and Huitzilopochtli is practically her weapon against the stars and moon, the night, which we can take as a metaphor for the Abyss in game.

Coatlicue is represented as a woman wearing a skirt of writhing snakes and a necklace made of human hearts, hands, and skulls. Her feet and hands are adorned with claws and her breasts are depicted as hanging flaccid from pregnancy. Her face is formed by two facing serpents, which represent blood spurting from her neck after she was decapitated. According to Aztec legend, Coatlicue was once magically impregnated by a ball of feathers that fell on her while she was sweeping a temple. She subsequently gave birth to the god Huitzilopochtli. Her daughter the goddess Coyolxauhqui then rallied Coatlicue's four hundred other children together and goaded them into attacking and decapitating their mother. The instant she was killed, the god Huitzilopochtli suddenly emerged from her womb fully grown and armed for battle.

- Wikipedia "Coatlicue"

• But considering Xiuhcoatl's moon imagery, and the fact that he was killed by the Huitzilopochtli's equivalent in game, Xbalanque, he could also embodied Huitzilopochtli's sister, Coyolxauhqui, the Goddess of the Moon.

On the summit of Coatepec ("Serpent Mountain") sat a shrine for Coatlicue, the maternal Earth deity. One day, as she swept her shrine, a ball of hummingbird feathers fell from the sky. She "snatched them up; she placed them at her waist." Thus, she became pregnant with the deity Huītzilōpōchtli. Her miraculous pregnancy embarrassed Coatlicue's other children, including her eldest daughter, Coyolxāuhqui. Hearing of her pregnancy, the Centzonhuītznāhua, led by Coyolxāuhqui, decided to kill Coatlicue. As they prepared for battle and gathered at the base of Coatepec, one of the Centzonhuītznāhua, Quauitlicac, warned Huītzilōpōchtli of the attack while he was in utero. Hearing of the attack, the pregnant Cōātlīcue miraculously gave birth to a fully grown and armed Huītzilōpōchtli who sprang from her womb, wielding "his shield, teueuelli, and his darts and his blue dart thrower, called xinatlatl." Huītzilōpōchtli killed Coyolxāuhqui, beheading her and throwing her body down the side of Coatepec: "He pierced Coyolxauhqui, and then quickly struck off her head. It stopped there at the edge of Coatepetl. And her body came falling below; it fell breaking to pieces; in various places her arms, her legs, her body each fell." As for his brothers, the Centzonhuītznāhua, he scattered them in all directions from the top of Coatepec. He pursued them relentlessly, and those who escaped went south.

- Wikipedia "Coyolxauhqui"

(Btw this supports my copium theory that Xiuhcoatl-Xbalanque are Natlan's symbolic twins. Having similarities with both the mother and sister of the God of the Sun and War... damn.)

In conclusion: Xiuhcoatl might not be female, but he probably does embody femininity. Thanks for the ask!

#genshin impact#genshin#genshin lore#natlan#genshin natlan#meta post#genshin theory#genshin sovereign#genshin dragons#dragon sovereign#hydro dragon#dendro dragon#neuvillette#genshin neuvillette#apep#genshin apep#xiuhcoatl#genshin xiuhcoatl#radaedan posting#radaedan ask#pyro sovereign#pyro dragon

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ballcourt in the Codex Borgia

Ullamaliztli (religious ceremony)

Ullamaliztli is a mesoamerican ballgame played by the Aztecs. Where a ball made of rubber, where each player would "kick" the ball with their hips.¹ It would be played in a court on an oblong-shaped field, with wider ends giving it the look of a capitalized I. A thick wall would surround the field, and in the middle of the wall, there would be a high ring which was the goal.² The ball weighed 2.5 kilograms and it could not touch the ground. It was only permitted to be kicked with the hips, head, elbows, and knees. The players wore protective shields, but they would still come out with bruises and bleeding. The Aztecs enjoyed gambling and used Ullamaliztli as an outlet too. With the loser needing to give up a daughter or wife to the winner. Even becoming slaves to the winning man.³ The court symbolized the Aztec underworld, with Ullamaliztli being a reenactment of day and night opposite forces, as the sun passes through the underworld to rise back up. This significance comes from the nature of the gods they worshipped dealing with elemental and cosmic manifestations. Such as gods of the sun, moon, rain, earth, and stars, based on a calendar cycle which determines the people's prosperity.⁴ An interpretation of this ritual is that the ball is the goddess of the moon's head. Representing her decapitation by Huitzilopochtli the sun god. Showing the light defeating the dark. It is said they played in specific equinoxes or months to influence the movement of the sun as it passes through the underworld⁵. The Aztecs used a ritual where they would choose someone to impersonate a god and then sacrifice them. In this ceremony, a player would be chosen to represent the moon goddess, and at the end of the game would be sacrificed to complete the ritual.⁶ The religious aspect of this game is to maintain a cosmic balance as many Aztec rituals are performed in order to prevent cataclysmic events.

-----------------------------------------------------

Bibloagraphy

Cohodas, Marvin. The Symbolism and Ritual Function of the Middle Classic Ball Game in Mesoamerica. American Indian Quarterly, vol. 2, no. 2, 1975, URL

Maries-Les, Gabriela. AZTECS - CIVILIZATION, CULTURE AND SPORTIVE ACTIVITIES: ACCES LA SUCCES. Calitatea 13, no. 2 05, 2012 URL

Leyenaar, Ted J. J. Ulama the Survival of the Mesoamerican Ballgame Ullamaliztli. Kiva 58, no. 2, 1992. URL

------------------------------------------------------

Ted J.J., Leyenaar, Ulama the Survival of the Mesoamerican Ballgame Ullamaliztli, (Kiva 58, no. 2, 1992,) p117, URL

Leyenaar, Ted J.J., Ulama the Survival of the Mesoamerican Ballgame UllamaliztlI, p119

Gabriela, Maires-Les, AZTECS - CIVILIZATION, CULTURE AND SPORTIVE ACTIVITIES: ACCES LA SUCCES. (Calitatea 13, no. 2 05, 2012,) URL

Marvin, Cohodas, The Symbolism and Ritual Function of the Middle Classic Ball Game in Mesoamerica, (American Indian Quarterly, vol. 2, no. 2, 1975,) p102, URL

Cohodas, Marvin, The Symbolism and Ritual Function of the Middle Classic Ball Game in Mesoamerica, p109

Cohodas, Marvin, The Symbolism and Ritual Function of the Middle Classic Ball Game in Mesoamerica, p109-110

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"As above, so below; as below, so above." —The Kybalion

Quetzalcoatl Talon Abraxas

Quetzalcoatl: The Feathered Serpent’s Myth & History

Before he was identified as an indigenous god, Quetzalcoatl was simply a peculiar snake-bird carving on a broken stone tablet found in Mexico—a carving, it turns out, from the Mesoamerican mother culture, the Olmecs. This appearance was the first of many, as explorations revealed the iconography of the feathered serpent peppered throughout Mesoamerican history, across cultures and religions, right up until the Conquistadors appeared. At one time, even blamed for the success of the Spanish conquest, Quetzalcoatl is an enduring example of how the line between myth and history can become blurred.

As Above, So Below: The Myths of the Feathered Serpent

A ubiquitous Mesoamerican deity occupying space in both the Aztec and Mayan pantheons, the feathered serpent was known by two primary names. Quetzalcoatl, the Aztec name, comes from the Nahuatl language, combining quetzal, a species of brightly feathered bird, and coatl, “snake.” The Mayan name, Kukulkan, is derived from the Yucatec Maya dialect, combining kukul, feathered, and kan, which was used for both “sky” and “snake.” In Mayan iconography, the snake is associated with life above and below the earth, pictured alternately in myth as a snake boy who grew too large and had to be hidden in a cave, and a winged serpent that flew too close to the sun and became the sun’s pet.

Beyond these stories, little is known about the Mayan Kukulkan, though his existence supports the theory that the feathered serpent motif is much older than either the Maya or the Aztec, likely dating to the much earlier Olmec civilization (1600–400 BCE). During what is generally referred to as the Formative period, Olmec and Mayan territories overlapped in the highlands of Guatemala, where Mayans continue to live to this day.

Much of what is known today of pre- and immediate-post-colonial Mesoamerican civilizations comes from extant written records, known as codices. The Aztec and Mayan codices were screenfold manuscripts, painted on front and back, made either of leather or the bark of various trees. The oldest known Mayan codex (Dresden) dates from around 1200 CE, though it may be a copy of an earlier book. Others, such as the Aztec codices, are more recent, often bearing the signs of Spanish influence, which calls their veracity into question. While examples of pre-conquest Mayan and Mixtec codices are known to exist, very few—as many as five, but as few as one—can be attributed to the Aztecs. Though more are known to have been written, some fell victim to the hot damp environment of the jungle, while others were burned by Catholic priests.

In addition to information about the astronomy of Aztec and Mayan civilizations, the codices provide a clear picture, literally, of their creation myths. The Aztec myth begins with the old god Ometoltl (from ome, “dual” and teotl, “divine”), a creator deity whose dual aspects resulted in the binary Ometecuhtli (male) and Omecihuatl (female) deities. Interestingly, little attention seems to have been paid to these creator deities and no temples were dedicated to them, since it was believed that people communicated not through them but through their four sons: Huitzilopochtli, Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, and Xipe Totec.

Of the four brothers, Tezcatlipoca and Quetzalcoatl were principally responsible for the creation of the world, or worlds, of which the Aztec believed there were four previous. Each world was created through the combined efforts of the brothers, embodying the dual aspects of light (Quetzalcoatl) and dark (Tezcatlipoca), good and evil, like two sides of the same deity. Alternately, one brother would decide that the other had messed up and destroyed his creation. After the fourth creation, it was Quetzalcoatl’s turn again. He descended into the underworld, Mictlān, to collect the bones of the dead from the previous four creations to create the people of the fifth, which included the Mexica.

The equivalent of Ometeotl in Mayan mythology is Itzamná. The word Itz has many meanings including “magic,” “magician,” and “witch,” but also “dew” and “essence.” Like Kukulkan, the lizard god Itzamná was associated with both the upper and lower worlds and had two names: Itzam Yeh (Bird of Heaven) and Itzam Cab Ain (Earth crocodile). Itzamná also had a female counterpart, Ixchel, and together they produced many offspring, including four brothers known as bacabs who, like the four main deities of the Aztec pantheon, each represented a color and a direction.

Mayan mythology diverges between two main groups: the K’iche’ and the Yucatec. Each had a different name for the feathered serpent, the more well known being Kukulkan, in use among the Yucatec. In present-day Guatemala, the feathered serpent was called Gucumatz (Q’uq’umatz). Beginning around 1500 BCE, the Maya have occupied highland Guatemala in one form or another, but no written records of their creation story have been found prior to the writing of the Popol Vuh, the “Mayan bible,” between 1554-1558 CE. Unlike the earlier Yucatec creation story featuring Itzamna and Ixchel, the Popol Vuh substituted Gucumatz and his brother, Tepeu, the K’iche’ equivalent of Tezcatlipoca, as creator gods, resulting in a somewhat simplified version of the Aztec and Yucatec stories of four brothers.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

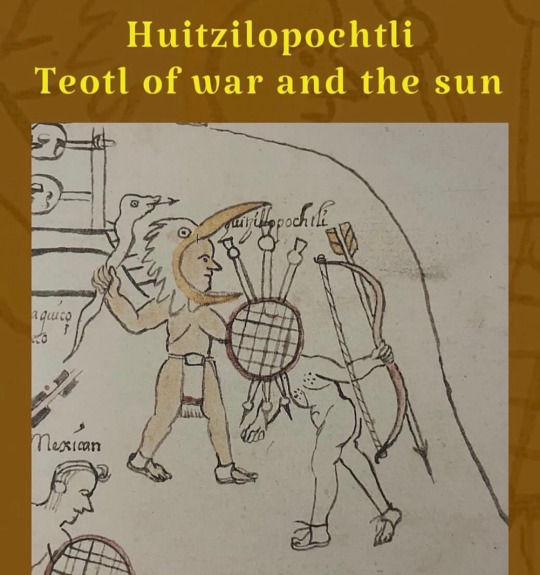

Huitzilopochtli,

leading the Mexica in battle while on their migration from Aztlan. He is fighting an enemy while holding a shield and atlatl darts in one hand and his xiuhcoat weapon in his other. He is wearing his hummingbird headpiece.

Photo: Codex Azcatitlan

#aztec mythology#aztec gods#mayan mythology#quetzalcoatl#aztec goddesses#huitzilopochtli#tezcatlipoca#azteccodex#prehispanic#aztec#aztecmemes

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lakes, canals and irrigation ditches in Mexico City and Tenochtitlán

You can also listen to this article in audio Upon arriving at the lake basin and in the various settlements they occupied for a century, the Aztecs carried out "religious constructions, acquired knowledge of water management through dams and erected defensive structures", as Sonia Lombardo points out in her work "Urban Development of Mexico-Tenochtitlan". Thus, when Tenochtitlan was founded in 1325 (some sources suggest 1370), on an islet in Lake Texcoco, they already had notions of urban planning and hydraulic engineering. The longed-for sign, according to the legend, represented by an eagle (Huitzilopochtli) perched on a cactus, was spotted "on a small islet, surrounded by tules and reeds, which was part of the Tepaneca lordship governed by the powerful Tezozómoc", as Lombardo indicates. According to the Codex Ramirez, quoted by the author, "the next day" they began the construction of an "altar of humiliation" to pay homage to the protector god, and "...using the sturdiest reeds they found in the reeds, they erected a square seat right in the same place...". This site probably coincides with the present remains of the Templo Mayor. Living space was extremely limited. They were in a situation of "scarcity, confinement and apprehension", so that their first constructions were simply jacales made of reed. Their livelihood depended exclusively on fishing and the resources obtained from the lagoon. In the second year, the Aztecs were able to acquire materials such as stone, wood and lime to erect a more durable temple in honor of Huitzilopochtli. This was achieved in exchange for resources from the lagoon: "...the fish, the salamander and the frog, the shrimp, the aneneztli, the water snake, the swamp mosquito, the lake worm and the duck, the cuauhchilli and the mallard, all the aquatic birds, with which we acquired the stone and the wood..." After the construction of the temple, a ball court was erected. The layout was radial, with four causeways radiating from the temple towards the cardinal points, thus forming four sectors. The lack of habitable space was solved by expanding the land, adding chinampas to the islet, especially in the south and southwest directions. The first main arteries were waterways, which made navigation a daily activity. A very delicate water management system. Expert understanding of the flow patterns in the surrounding bodies of water gave the Mexica the ability to establish a sophisticated hydraulic system based on dams, floodgates, irrigation ditches and a network of canals for both navigation and irrigation, thus forming a system that adjusted to the seasons of the year. This engineering not only mitigated the risk of flooding, but also prevented the mixing of the saline waters of Texcoco with the fresh waters of Xochimilco and Chalco, as well as preventing possible attacks from rival communities. A clear example of this innovation is the Iztapalapa causeway, which served a dual function as an extensive dike separating saline and fresh waters. On both sides of this road, canals flowed that probably played a strategic role in the transport of resources. The relevance of this transportation infrastructure is reflected in "Historia general de la infantería de marina mexicana", where it is suggested that it not only facilitated the transfer of supplies and personnel, but also conveyed the notion of the vulnerability of the lake cities and islands to a possible enemy attack. Tenochtitlán's geographical position allowed the militias to move quickly through the basin. "The Mexica military structure included an Infantry Corps, which operated both on land and in aquatic environments, covering rivers, lakes and coasts, manifesting a versatile approach in its organization." In terms of road infrastructure, the Tacuba causeway stands out, which apparently had at least seven drawbridges, and presumably followed a model similar to that of the Iztapalapa causeway, carrying out both aquatic and road functions.

According to Lombardo's writings, during the reign of Moctezuma II (1502-1520), the city had three types of streets: terrestrial, aquatic and mixed. The waterways were highly transited thanks to the canoes, used as an efficient and widespread method of communication among the population, while the chinampas and most of the houses connected with irrigation ditches for daily services. The main doors of the houses opened onto narrow land streets. Small beam bridges crossed the ditches, facilitating the passage of pedestrians. Some of the mixed streets had a considerable width. Take as an example the road currently corresponding to 16 de Septiembre-Corregidora, later called Acequia and Las Canoas, which had a width of 7.5 meters in the water lane and 5 meters in the land lane. The Mexica demonstrated outstanding control in the art of navigation and the science of hydraulic engineering. When the Spaniards arrived, the Valley was home to about 40 cities that maintained a vigorous activity. According to Carlos J. Sierra in "Historia de la navegación en la Ciudad de México", it is estimated that, at the beginning of the 16th century, approximately one million fish were extracted to supply these cities. Every day, some 4,000 canoes entered the city bound for the Tlatelolco market. Alonso Suaro, another Spanish chronicler, calculated that in the lagoon there were between "sixty and seventy thousand large canoes" used to transport provisions. Although there is no confirmation in the sources consulted, it has been mentioned that the Mexica practiced a form of sport similar to regattas as part of their training. Regarding the acallis, a term used to refer to smaller vessels, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, one of the conquistadors, described that "they were carved from a single tree trunk without joints (...). They had a flat bottom and no keel. There were various sizes, from one or two persons to those that could carry forty or fifty crew members. They were very light and capsized easily, but did not sink, even if filled with water." Poles were used in shallow water to propel the boat, while paddle oars were used in deeper water. mixed infantry controlling the lakes. In its beginnings, Mexica society was characterized as theocratic, with leadership led by religious figures. However, over time, this structure evolved into an imperial system in which commercial and military aspects became as important as religion. This change developed gradually, but the rise of the Mexica as a dominant culture in Mesoamerica was solidified with the formation of the Triple Alliance in 1430, in collaboration with Texcoco and Tlacopan. At the height of what could be described as a "militaristic state" formed by the Triple Alliance, navigation acquired a strategic role, since its power was based on the extensive use of canoes. These vessels offered benefits in the transport of military supplies, soldiers and equipment. In addition, they contributed to propagate the perception, both among the lake cities and the islands, that they were targets that could be reached quickly. These aspects are highlighted in "Historia general de la infantería de marina mexicana". Tenochtitlán's location gave the militias the ability to move quickly throughout the basin, which provided a crucial strategic advantage. "Within their military structure, the Mexica had an Infantry Corps that operated not only on land, but also in river, lake and coastal environments. This meant that this infantry had versatility in both terrestrial and aquatic environments." In the context of Tenochtitlán, the route that currently corresponds to the 16 de Septiembre-Corregidora avenue had a hybrid nature. This road had a width of 7.5 meters in the water lane and 5 meters in the land lane. Thirteen brigantines from Tlaxcala. The vision the Spaniards had upon first contemplating the majesty of the city of Mexico-Tenochtitlan has been described on countless occasions; Bernal Díaz del Castillo expressed it as ".

.. things of enchantment". When invited to explore the city, both the lake structure and the naval activity attracted the attention of the conquistadors. Hernán Cortés carefully observed the operation of the floodgates and recognized the threat they would pose in future confrontations. In response, he planned the construction of "four brigantines to facilitate exit by water in case of need," as chronicles of the time relate. At the same time, Moctezuma II experienced for himself the amazement of boarding one of the brigantines, when he was invited to join a hunt. The technology of the sails, unknown to him, proved to be far superior to the indigenous canoes that could not catch up. The first major clash between the Mexica and the Spanish, along with their indigenous allies, took place after the massacre at the Templo Mayor, in which 600 high-ranking Mexica were killed by Cortés' soldiers. The indigenous retaliation ended on June 30, 1520, after seven days of siege against the foreigners, who took refuge in the houses of Axayácatl. The Spaniards fled silently during the night, along Tlacopan Avenue. However, they were discovered and attacked both through the irrigation ditches and from the rear with projectiles. Despite carrying a portable bridge to cross the sections cut by the irrigation ditches, many did not make it to the mainland and lost their lives in the attempt. A year later, with the support of the Tlaxcalans, Cortés returned with the firm intention of conquering the city. His strategy involved encircling it and cutting off its provisions, especially the supply of drinking water that came through an aqueduct from Chapultepec. To confront the imperial naval fleet, he brought with him from Tlaxcala 13 brigantines that he had ordered to be built. These were transported by eight thousand Indians to Lake Texcoco. The first naval combat documented in the chronicles of the American continent was fought at 2,200 meters above sea level during the siege imposed by Cortés on the great Tenochtitlán in Lake Texcoco, beginning on May 10, 1521 and lasting 95 days, according to records in "Historia general de la infantería" (General History of the Infantry). Other sources suggest that its duration was 75 days. Through alliances that were consolidated, Cortés finally achieved the conquest with the support of 50,000 indigenous combatants and 20,000 canoes. On the Mexica side, 300,000 troops and "thousands" of canoes participated, many of them with armor. Among their combat tactics, the Mexica installed stakes in the lake to damage enemy vessels or drove them to unseen areas called albarradones so that they would collide there. Some of the brigantines had to be repaired during the siege. Meanwhile, land incursions became deeper as time went on. The supply of drinking water was soon exhausted and the solution of supplying it by canoes proved unsustainable. The cut-off of communication between Tenochtitlán and Tlatelolco, their source of provisions, proved crucial. In the final battle, which lasted 24 hours, the Mexica faced both brigantines and 6,000 canoes. Finally, on August 13, Tenochtitlán, exhausted by war, hunger, thirst and smallpox, fell, as summarized in "Historia general". In later times, to the east of the city, a fortress known as Las Atarazanas was erected to guard the brigantines, guaranteeing their safety and their ability to enter and exit as needed. This site, close to La Merced market, evolved into a small square. However, lack of care, maintenance and careening led to the destruction of those ships between 1531 and 1540. Solutions in the new Spain a vicious circle of patches The capital of New Spain maintained in part the pre-Hispanic hydraulic system, although it suffered considerable damage during the siege. An example of this was the breaking of the albarrada de Netzahualcóyotl by Cortés, which had served to direct the flow of fresh water from springs and lakes such as Xochimilco and Tláhuac around the island.

This breach was made to make way for the brigantines. After the war, many ditches were filled with stones from destroyed buildings, transforming them into streets and avenues. Despite this, river navigation continued to be active, not only for supplies, but also for the construction of the new city. A large quantity of materials was transported in canoes. Curiously, several dams were altered by using their stones. Subsequently, the intensity of water traffic decreased. According to Sierra, "during the years of the Conquest, the number of canoes oscillated between 100 and 200,000; in the 16th century, more than 1,000 canoes entered the city daily. However, by the 17th century, this figure varied between 70 and 150. The disarticulation of the hydraulic system led to flooding problems which, in turn, made it difficult to clean the canals, generating a vicious circle. The flood of 1629, which submerged the city in water and mud for four years and forced evacuations, further aggravated the river system. For example, the albarrada de San Lázaro was completely covered by water. These difficulties led the Spaniards to try to solve the problem by patching it up, but without success. By the end of the 16th century, the idea of draining the lake was already under consideration, although it would take centuries to carry it out. Nevertheless, by the late 17th and early 18th centuries, travelers and chroniclers praised the "Venetian" image of the city. Despite the adversities, seven main irrigation ditches survived, along with several secondary ones, canals and bridges that fostered a vibrant commerce. In fact, there was a resurgence in river trade. Each canoe could carry between 65 and 70 bushels of corn (a bushel was approximately 55 liters), according to Sierra. By the end of the 17th century, it was estimated that around 5,000 bushels were arriving in the city. In 1709, 97,330 bushels transported in 1,419 canoes were recorded. In addition, other products were also transported through this waterway. In 1803-1804, Viceroy Iturrigaray made the decision to open the Texcoco canal in order to reduce the cost of transporting wheat from Tula and Cuatitlán. This was due to the high cost of overland freight. The dirt roads were at risk due to the presence of robbers and suffered deterioration during the rainy season, although the yield of the river canal decreased in times of drought. Nevertheless, in a sort of institutional contradiction, the project to drain and drain the lakes continued. The arrival of the Bourbon dynasty to the Spanish throne marked the destiny of New Spain in economic, political, social and cultural terms. The system of irrigation ditches and canals also faced its definitive challenge. Due to their limited efficiency as a means of transporting people and supplies... Bourbon reforms included a focus on the cleanliness and organization of the roads. Ditches were identified as "sources of infection", but to ensure the drainage of the city, "the main ones (...) were replaced by subway conduits or atarjeas". The process of obstructing the irrigation ditches began in 1753, starting with the blocking of the Royal Ditch, the most abundant of all: "...it was blocked in the section with the least river traffic, between the Coliseum and the southwest corner of the Plaza Mayor, and in its place a double ditch was built to ensure a smooth flow of water". By the beginning of the 19th century, "the 'water streets' had practically disappeared" from the urban structure. Of the 56 bridges that existed in the mid-18th century, about a dozen had been lost - the remaining ones deteriorated - although some new ones were also built. A sad disassembly The transformation of the old hydraulic system of Mexico-Tenochtitlan was methodically executed under the direction of the Bourbons. This change not only permanently altered the urban landscape, but also the means of transportation and points of reference for the inhabitants of the colonial city.

The progressive "obstruction of the irrigation ditches" began in the eighteenth century and continued throughout the nineteenth century, as detailed in the study "Las calles de agua de la Ciudad de México en los siglos XVIII y XIX" by Guadalupe de la Torre. Several factors contributed to this process. The decrease in the water level in the acequias was due to "the detour of water flows and the expansion of riverbeds to expand irrigation of arable land". In addition, "the lack of an effective strategy for the maintenance and cleaning of the irrigation ditches caused their deterioration". By the end of the 19th century, bridges were no longer predominant urban landmarks, although many streets still retained related names, such as Puente de la Misericordia, Puente de Tezontlale, Puente del Espíritu Santo or Puente del Zacate, as De la Torre points out. However, the Acequia de Mexicalzingo, also known as the Canal de La Viga, had a different destiny. Throughout the 18th century, the viceroyalty authorities were interested in keeping it functional to facilitate the traffic of canoes and trajineras. As the water level decreased due to the drying up of the lakes, floodgates were installed in Chalco to regulate its flow. This canal even had an important bridge, La Viga, which since 1604 functioned as a checkpoint, located two kilometers from present-day San Pablo Street. In the 19th century, a wide variety of products transited through this canal, from foodstuffs such as sesame, rice and corn, to materials such as wood, beams, iron and more, as detailed in Araceli Peralta's account in "El canal, puente y garita de la Viga" (The La Viga Canal, Bridge and Checkpoint). In the period from 1858 to 1859, the La Viga checkpoint saw the passage of 685 trajineras, 960 larger boats (24 varas long), 90 medium-sized boats (12 varas long) and 458 chalupitas carrying wool, stone, sand and more, for a total of 4,944 canoes. This busy commercial flow would join the new wave of industrial innovations. The Mexican Republic on a steamboat After the achievement of the War of Independence, the question of the lake system in the Valley of Mexico remained a controversial issue: "while some considered it essential to drain the lakes, others advocated taking advantage of them for transportation, canalization and irrigation purposes, and there were those who believed in the combination of both strategies for the planned development of Mexico City," as Sierra's opinion highlights. Among the group of those interested in taking advantage of bodies of water were a number of entrepreneurs and inventors who, from the 1840s to the end of the century, presented a series of projects for inland navigation. The ability of many of these projects to prosper, despite the political and economic instability that characterized Mexico during much of that period, is surprising, although it is true that several also had unfavorable results. The precursor of steam navigation on the Anahuac was Mariano Ayllón, who overcame multiple obstacles to establish and operate a company with three steamboats, destined to travel between the capital, Chalco, Texcoco, Tacubaya, Guadalupe Hidalgo, San Ángel and Tlalpan. This involved the construction of the first two steamboats (one with a capacity for 200 passengers and the other for 20), the creation of a dock at the La Viga checkpoint, the cleaning of the canal and the raising of some bridges. On July 21, 1850, the steamer Esperanza made its first trip to Chalco, and by August, the service was in regular operation. In 1861, José Brunet also obtained permission to operate steamboats in the valley. In addition, Carlos Pehive introduced "propeller boats for the canal or ditch from Mexico to Tacubaya," while Tito Rosas promoted sailing in sailboats. During the Maximilian government (1863-1867), as Sierra mentions, some additional permits were granted. In 1869, a company launched the steamship Gautimoc, which offered services between the city and lakeside towns.

On its maiden voyage, President Juárez was invited and part of his cabinet was present. Although on the trip there was an explosion in the boiler, fortunately without causing any damage. Guillermo Prieto, in a chronicle, commented: "... the good fortune of the President of the Republic, who always comes out unscathed from all dangers, is striking". Approval of more projects continued until 1890. However, natural desiccation of the lakes persisted, and maintaining adequate water levels for navigation in the canals became increasingly challenging by the second half of the 19th century. Numerous steamboats operated in this period between the capital and Chalco. Despite the need for works, the uncertainty as to whether accelerating the dewatering was the best option remained an unresolved issue. It was during Madero's administration that the decision was finally made to carry out this task. Last glimpses of a lake past. The transformation of the lake system in Mexico City experienced its last phases at the end of the 19th century and at the dawn of the 20th century. The elements that contributed to this process are in essence similar to those that manifested themselves in the mid-18th century, but with an accentuated intensity. In addition, the rise of the railroad and later the automobile gradually displaced river transport. After the drainage of the La Viga canal, this body of water became a deposit of waste and garbage, where elements such as water lilies, decomposing animals and various types of putrefied materials accumulated. This situation led the Hygiene Commission to classify this area as a high risk to public health. In 1940 the filling process began and by 1957 the area was paved, as detailed by Peralta. One type of resurgence of the lake system took place in 1952, when floods caused considerable damage in the city center, especially on 16 de Septiembre Street. During this period, canoes reappeared "sporadically" to transport people, as Sierra points out. It seemed that the spirit of times past wished to remind the inhabitants of modern Mexico City of one of the means of transportation that was once essential in this region. Some resuscitation maneuvers. The discovery in 1978 of the monolith of the goddess Coyolxauhqui, belonging to the Mexica civilization, in the area of the Templo Mayor, provoked a notable interest on the part of the local and federal governments to revitalize the Historic Center of Mexico City, which had been neglected at the institutional level. The initiative began with the demolition of structures in the region to recover pre-Hispanic vestiges. This process was followed by a kind of reconstruction of the colonial city, which involved the restoration of emblematic buildings and the recovery of the historical scale of the city. The restoration project, carried out between 1980 and 1981, also included archaeological excavations on a 260-meter stretch of the Acequia Real, which ran along the streets of Corregidora, from Pino Suárez to Alhóndiga, and then following the latter. The Acequia Real, which was vital in pre-Hispanic times, had been partially obstructed at several points and its closure was completed in 1939. These excavations made it possible to trace the route of the irrigation ditch and to discover the remains of walls, stairways, piers and bridges, as well as a variety of objects from both the pre-Hispanic and colonial eras. Under the direction of architects Pedro Ramírez Vázquez and Vicente Medel, together with historian Gastón García Cantú, it was decided to restore two sections of the Acequia. One of them was located in Corregidora, along the National Palace, and the other in Alhóndiga. Images from that time show an unusual urban landscape with these two restored water areas. However, this was also a time of rapid growth of informal commerce, which led to the encroachment of the streets. The restored sections were hidden and became garbage dumps, repeating a pattern of decay. In 2004, these sections had to be closed again.

For a time, puddles formed under the Roldán bridge and near the Casa del Diezmo. These problems were addressed in 2009, when a renovation of the urban infrastructure of Alhóndiga Street was carried out, converting it into a pedestrian area and sealing these puddles. With this event, it seems that the chapter of the waterways in the Historic Center is concluded. However, Mexico City is still located in a lake basin, and the power of the water that remains in its foundations sometimes manifests itself, reminding us of its past. The Flowery Lenten Season and the Paseo de la Viga A segment of the La Viga canal was transformed at the end of the 18th century into the charming Paseo de la Viga. Also known at different times as Paseo de la Orilla, Paseo de Revillagigedo, Paseo Juárez and Paseo de Iztacalco, it experienced its greatest splendor in the 19th century. This place of recreation and entertainment for the inhabitants of Mexico City covered 1,560 meters long and 30 meters wide. Its natural beauty inspired several writers, including Guillermo Prieto, the Marquise Calderón de la Barca, Luis Castillo Ledón and Ignacio Muñoz, according to Araceli Peralta. Especially during Lent and the celebration of the Friday of Sorrows, or Fiesta de las Flores, people of all social classes congregated at this site. Ignacio Muñoz, mentioned by Peralta, relates: "From early in the morning, the whole city would go to these streets (Roldán) where the pier was, renting canoes and trajineras decorated with poppies, celery, tulles and carnations, which were used to stroll along the canal until reaching La Viga or Santa Anita the rowers sang and danced in the canoes, where tamales, moles, atoles, enchiladas and all sorts of delicacies of the complex Mexican gastronomy were served." Xochimilca farmers took advantage of this festivity to earn additional income by offering rides in their canoes. Incidents were not exempt, "mainly caused by drunkenness and negligence of visitors, which led the City Council to establish a mounted police force in charge of maintaining order in the promenades of Mexico City". Acequias in Mexico City. During the 18th century, there were five main irrigation ditches in Mexico City that originated in the western part of the Mexico Basin and crossed the region in a west-east direction, following the natural slope of the terrain until they flowed into Lake Texcoco, the lowest area. According to Guadalupe de la Torre Villalpando's research, these irrigation ditches were fundamental to the hydraulic structure of the city. Among these irrigation ditches were the Santa Ana, Tezontlale, the Apartado or del Carmen, another unspecified one that entered through the Chapultepec Causeway (filling the neighborhoods of San Juan and Belén), and then turned south, crossing the Salto del Agua and Monserrat neighborhoods until it reached the San Antonio Abad swamp. The Royal or Palace irrigation ditch was the largest and most abundant, divided into three branches, including the Regina and La Merced. Additionally, there was the outstanding Mexicaltzingo acequia or La Viga canal, which arose to the south, in Chalco, and continued its course northward, passing through the east of the city. Another significant acequia was the resguardo (fiscal) or "square ditch", so called because of its distinctive shape. It was begun in the first half of the century with the purpose of connecting the sentry boxes that surrounded the city, facilitating better control of tax collection and the entry of merchandise. Although it was never completed in its entirety, the sections that were built gradually disappeared due to urban expansion at the end of the 19th century. These irrigation ditches played a vital role in the historical configuration of Mexico City, and although many of them are no longer visible, their legacy endures and continues to influence the structure of the city today.

0 notes