#Ciudad Rodrigo

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Calle Campo de Carniceros, Ciudad Rodrigo, Salamanca, Castile and León.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

CIUDAD RODRIGO ( SALAMANCA )

0 notes

Text

Mañana estrenamos en la Feria de Ciudad Rodrigo. LA MUJER HELADA de Annie Ernaux dirigida por Nina Reglero.

0 notes

Text

Tú en otra visión …

El profeta del Nopal [cit yix]

Metro Balderas, México, Deefe

JUNIO 24 [Este Junio, nunca igual … una vorágine y tantas cosas] tienes 23 Zof.

#Balderas#Deefe#UNIVERSIDAD#Rockdrigo#CitYix#sarapedeneon#mexico#photography#streetphotography#anthropology#street#Salvaje#ciudad salvaje#fotografia#Rodrigo Gonzales#ciudad de méxico#CDMX#fotografasdemexico

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Consuetudinario ≠ Transcripciones

De re metallica

Lecturas Transgresoras núm 7

tercera serie

Libro digital disponible desde el 23 de Abril a las:

13:51 UTC+1. LDN WC2B 5AZ. New Jerusalem: Hasid and Kabbalists.

18:51 horas (GMT-6) CdMx, civilisational project of the New Babylon.

Descarga gratuita en PDF;

No busques en este texto elementos estéticos en la narrativa. Busca la riqueza de su contenido, la valentía de la denuncia realizada por las personas que me han contado acerca de las adicciones, sus implicaciones y consecuencias. Durante más de dos décadas esperé una oportunidad para poder contarles mi historia que, con el pasar del tiempo, se ha vuelto varias historias entrelazadas, donde todos vamos a buscar la felicidad a nuestra manera y según nuestros alcances. Para llegar a ese estado ilusorio de felicidad, veremos cómo cada uno rompe reglas, convencionalismos, normas, códigos, incluso la propia asignación de la personalidad.

Respecto a mi octava publicación digital:

Continuado la secuencia posmodernista de la distribución masiva heredada de la imprenta para subir ─un tema poético principal donde el amor, es expresado en modos diversos─. Para influir en el imaginario colectivo de las sociedades cada vez más globalizadas.

"Poner nuestra vida al desnudo, es el arte de todos los tiempos."

Rodrigo Granda :

“Para revelar; la Mente y el Alma”

Phaneinthymos Media Group Inc. | Phanerothyme

Ciudad de México, México © 2014-2024

─ Index librorum prohibitorum ─

solve et coagula…………...………..............pagina 9

la paleta Tutsi..............................................pagina 21

Sokoły...........................................................pagina 29

Loquillo........................................................pagina 35

pelea como un tigre....................................pagina 43

mi fan #1...............………………………....pagina 51

vetustos libros……………….....................pagina 59

algo para fumar...........................................pagina 67

risa y pánico de marihuanos....................pagina 75

Ahora es “Sharon”.....................................pagina 85

descalza como hippie.................................pagina 97

Las niñas....................................................pagina 105

whisky o whiskey......….......................... pagina 117

#Consuetudinario ≠ Transcripciones#De re metallica#Lecturas Transgresoras núm 10#adicciones#convencionalismos#normas#códigos#asignación de la personalidad#publicación digital#posmodernista#Rodrigo Granda#Phaneinthymos#Phanerothyme#Ciudad de México#México#Trangender#Trans#LGBTIQ+#solve et coagula#Sokoły#vetustos libros#Yuku Chayu#whisky o whiskey#Collection opensource#Language Spanish

0 notes

Text

Noches del Botánico: Farru, Michel Camilo y Tomatito

Botanical Nights: Farru, Michel Camilo and Tomatito Cover Photo: Michel Camilo y Tomatito. TERESA FERNANDEZ HERRERA Directora General de Cultura Flamenca. Periodista – Prensa Especializada Primero el recinto. Un lugar de ensueño para conciertos de verano. En plena Ciudad Universitaria de Madrid, en la avenida Complutense, el Real Jardín Botánico Alfonso XIII, es ajeno a la terrible ola de…

View On WordPress

#"VIVIRÉ"#A dream place for summer concerts#A MEETING FOR HISTORY#BALAOR#CAMARON DE LA ISLA#CHICK COREA#Ciudad universitaria de Madrid#COMPOSITOR DEL ULTIMO KETAMA#CULTURA FLAMENCA#DOS UNIVERSOS#EGBERTO GISMONTI#El Farru#EL REAL JARDIN BOTÁNICO ALFONSO XIII#ESPAÑA#FLAMENCO JAZZ#FOTOGRAFIAS COPYRIGHT FER GONZÁLEZ#INTRO AL CONCIERTO DE ARANJUEZ#JOAQUIN RODRIGO#JONI CORTÉS.JOSE FERNANDEZ Y JOSE VIDAL#JOSE DEL TOMATE#JOSEMI CARMONA#lomasleido#LUIZ BONFÁ#MICHEL CAMILO#SOLEÁ Y BULERIAS#TANGOS DE ASTOR PIAZZOLA#TERESA FERNANDEZ HERRERA MEJOR PERIODISTA ESPECIALIZADA DEL AÑO 2022#Tomatito#UN ENCUENTRO PARA LA HISTORIA

0 notes

Text

Panadero, Ciudad de México, 1963. Rodrigo Moya. Gelatin silver print.

#black and white#photography#foto#fotografia#fotografie#photographie#1960s#mexico#bread#food#city scene#tradition

476 notes

·

View notes

Text

Luz robada, Ciudad Netzahualcoyotl, México, Photo by Rodrigo Moya, 1964

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

LaDS Argentina headcanons

Estaba muy al pedo y necesitaba algo así de los pibes. Son solo mis headcanons personales, así que sientanse libres de agregar cosas que piensen quedan mejor o que cambiarían.

Zayne

•Nombre argentino: Francisco, no le copa el apodo pancho y Carlitos le jode llamándolo así todo el tiempo

•Apellido con el cual lo identifico: Sanchez (no te enganches, porque te va a dejar sin caminar)

•Mc peleando constantemente con Zayne sobre si el mate puede sustituir a tomar agua

•Zayne toma mate dulce, nada de stevia, le manda azucar al palo

•Macarones who? El alfajor es la que va para Zayne

•Creo firmemente en que Zayne y MC se ponen en campaña para probar todos los alfajores, hasta investigan y hacen una lista en google sheets para ir marcando los que van probando, cuantas estrellas le dan, etc

•Tengo cero fútbol pero por alguna razón Zayne y San Lorenzo simplemente matchean en mi cabeza

•Zayne estudió medicina en la UBA y nadie puede convencerme de lo contrario

•Está viviendo en Buenos Aires pero es nativo de Tierra del Fuego

•Hacen viajecito con MC a conocer la Antártida

•Lo veo escuchando a Lali gracias a MC, se vuelve fan

Xavier

•Nombre argentino: Javier, quién sino.

•Apellido con el cual lo identifico: López

•La siesta es sagrada, no se discute

•Le gusta viajar en micro en vez de avion, porque se sube y no despierta hasta llegar a destino

•Fan de racing y Guillermo Francella

•MC le jode con que el hijo de Francella es alto actorazo y obviamente se pone celoso (de todos los actores)

•El y MC se hacen viajecitos en los feriados largos, visitan lugares como Chascomús y Pergamino, pueblitos super tranquis para relajar del aire de ciudad

•Lo veo como pibe de ciudad con alma del interior, por ahí no de Buenos Aires, pero Rosario seguro.

•Sanguchitos de miga es su segundo nombre

•Emanero y trap argentino

Rafayel

•Nombre argentino: Rafael obvio, pero también lo veo como un Sebastián

•Apellido con el cual lo identifico: Fernández

•Vive en el Malba, básicamente

•Fiel creyente de que le gusta pintar o hacer esculturas de pueblos originarios

•Rafayel y MC se ponen a viajar por Argentina con la idea de visitar todos los museos de historia y arte

•Le encantan las Cataratas de Iguazú, del lado argentino obvio. No hay una vez que visite y no se traiga un souvenir de un yaguareté o un tucán o un coatí

•Vitel Toné y Paella y Rabas.

•Le gusta escaparse de Tomás e irse a Mar del Plata, recorre toda la costa y sus playas.

•No me pregunten por qué, pero mi instinto me dice que es de Santiago del Estero.

•No es muy fan del fútbol pero si le preguntas te dice que es de River (porque fue a ver a Taylor Swift)

•Re fan de Soda Stereo y Tini, Emmanuel Horvilleur.

Caleb

•Nombre Argentino: Carlos, Carlitos

•Apellido con el cual lo identifico: Hernández, MC le vive cantando el tema del Cuarteto de Nos

•Asado todos los findes y después se recalienta toda la semana

•Se manda altos guisos

•Es cordobés, fernet y cuarteto, lo lleva en la sangre

•Con MC viven yendo a las sierras cordobesas para ver si encuentran ovnis

•Tiene un cuadro de Rodrigo y de Gilda, al lado de una estatuilla del gauchito gil

•Gideon- perdón, Gastón se pasa a visitar todos los findes, se mandan unos asaditos, fernet y un cuarteto de fondo para bailar cuando pega la noche

•Juega al fútbol después del laburo

•Es hincha de Talleres

Sylus

•Nombre argentino: Ciro o Santiago

•Apellido con el cual lo identifico: Gómez. No sé, no me lo puedo sacar de la cabeza

•Tiene campos en todas las provincias

•Vive en Mendoza pero nació en el Chaco

•Fiel hincha de River, va a todos los partidos y lleva a MC a los palcos

•Fan de Ciro y los Persas, Los Piojos, Los Redondos, Mercedes Sosa, pero MC lo cacha escuchando a Wos y Trueno cada tanto

•Pastas. Ravioles, ñoquis, sorrentinos. Salsa blanca o tuco, los 29 pone dólares abajo del plato.

•Se recorrió toda la Argentina en moto

•Tiene stickers de "las Malvinas son Argentinas" pegadas en su moto y en sus autos. También tiene pins. Usa escarapelas en todos los feriados nacionales

•Juega a la quiniela

Extras

•Talía (Talia) se presenta en el Colón y es más que seguro que Rafa la va a ver.

•Tomás (Thomas) más de una vez tiene que salvar a Rafa de que lo metan preso por hacer grafitis en la calle

•Tamara (Tara) es fan de hacer la carta astral, se junta con MC a tomar mate y comer alfajorcitos de maizena mientras le tira las cartas

•Jenny (Jenna) es parte de Gendarmería o Prefectura

•Gerardo (Greyson) también estudió en la UBA

#love and deepspace#lads#love and deepspace headcanons#lads headcanons#lads hc#love and deepspace hc#headcanons argentinos#lads argentina#love and deepspace argentina#lads zayne#lads xavier#lads rafayel#lads sylus#lads caleb#zayne#rafayel#sylus#xavier#caleb

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Calle Gavia, Sancti-Spíritus, Salamanca, Castile and León.

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

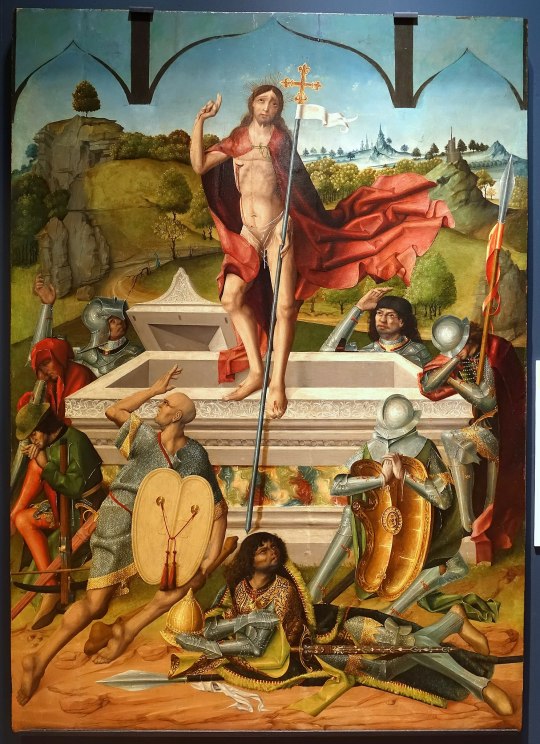

The Resurrection (from the Ciudad Rodrigo altarpiece), Maestro Bartolomé and workshop, between 1480 and 1488

#Easter#Easter Sunday#Resurrection#art#art history#Maestro Bartolomé#religious art#Biblical art#Christian art#Christianity#Catholicism#New Testament#Gospels#Spanish art#15th century art#oil on panel#University of Arizona Museum of Art

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elie Baudus about Masséna and Bessières

In volume 2 of his memoirs, Elie Baudus adds a long note about what went on between Masséna and Bessières at the battle of Fuentès de Onoro – the occasion at which Masséna is said to have remarked that, on seeing Bessières arrive at the head of his troops, he had hoped for "a bit more men and a bit less Bessières" - , and about his mission to report to the emperor about that failed battle. Unsurprisingly, Baudus, being an ADC to Bessières, relates the events quite differently to others, writers close to Masséna. As I have not seen Bessières’ side of the story so far, I thought it might be interesting to some.

Be warned though, it’s really very long.

I will place here some memories about the different missions that were entrusted to me at that time, first in contact with this illustrious warrior [Masséna], and in the end with the emperor, after the battle of Fuentès de Onoro. These memories can serve to make known the character of Napoleon, and to demonstrate that, as great as was his firmness, he nevertheless never managed to impose from afar to his generals to be united; they will also show that, despite his willingness to never be in ignorance of anything that was important for him to know, the truth nevertheless had some difficulty getting through to him. In this respect the details that one will read may appear worthy of interest.

In March 1811, Marshal Masséna left Santarem to bring his army back to the Spanish borders. As soon as Marshal Bessières learned about this movement, he gave orders to make the necessary preparations in the provinces of Salamanca and Ciudad-Rodrigo to provide these troops, exhausted by a long and difficult campaign, all that they might need. I was charged with transmitting to the generals in command there the instructions related to what had to be taken care of. On top of that I had orders to visit the place of Almeida, to inform myself about the state of its supplies, so that I could give to Marshal Masséna all the information he might want, as it was also part of my mission to go to his headquarters, in order to offer him from the Duc d'Istrie all support in infantry, artillery and cavalry that he needed. I joined the Prince of Essling between Sabugal and Alfayatès; he answered to the offers I made to him “that he only demanded food.’ I returned to Valladolid, headquarter of the Armée du Nord de l'Espagne, and a couple of days later the army of Portugal arrived under the cannons of Ciudad Rodrigo. Marshal Masséna moved his headquarters to Salamanca, and his troops entered into cantonments.

This rest however would not last much longer than a month, because at the end of April it became necessary to occupy ourselves either with throwing provisions into Almeida, or with lifting the blockade from the English who had tightly surrounded this place from the moment our last columns had crossed the Portuguese border back. Marshal Masséna having informed Marshal Bessières about his plans with regards to this point, the latter sent me to Salamanca to come to an understanding with his colleague about the support the Army of Northern Spain could be called upon to provide for this operation.

Marshal Masséna, to whom I was authorised to promise the cooperation of a large corps of all arms which the Duke of Istria intended to lead in person, told me ‘that he had enough infantry, that the equipment and personnel of his artillery were sufficient; that he only lacked horses’. He therefore asked only for teams for his artillery and as much cavalry as the Duke of Istria could muster in the short time between now and the time when the food situation of the Almeida garrison would force him to begin his movement.

The illustrious victor of Zurich treated me with a kindness and distinction that flattered me infinitely. During my stay at his headquarters, I had the honour of dining tête-à-tête with him several times. The Marshal was so preoccupied with the sad results of his campaign in Portugal that he was willing to talk to me about the causes he attributed to its lack of success. He complained mainly, and with great bitterness, of the inadequacy of the means which the emperor had placed at his disposal, and told me, with a frankness beyond all praise, that in putting him in charge of this difficult operation he had been given a task beyond the strength left to him by so many labours of war. He added that he felt perfectly well that the time had come for him to retire from active service; that after thirteen years as commander-in-chief, it was time to leave this responsibility to officers younger than himself. His exasperation with his master was such that he seemed to have the deep conviction that the Emperor had only employed him in this circumstance in order to make him lose the beautiful name of Cherished Child of Victory which Bonaparte, as General-in-Chief, had bestowed on him on the glorious battlefields of Italy. The vivid complaints of this Nestor of our modern military glory, even more laden with laurels and fatigue than with years, awakened in me the memory of the great things he had done, and caused me an emotion that it would be difficult for me to express. A few days later I was destined to hear, from Napoleon himself, the counterpart to these warm recriminations. On the day of my return to Valladolid, orders were given to assemble all the cavalry available, and Marshal Bessières left the following day at the head of two thousand horses, made up of General Wathier's brigade and eight hundred cavalrymen of the guard, followed by the quantity of horses necessary to harness six batteries of artillery.

When we arrived in Salamanca we no longer found Marshal Masséna; he had left the day before to establish his headquarters in Ciudad-Rodrigo, where we joined him on 1 May. On the 3rd the army marched on Fuentès de Onoro, a large town in a good position on one of the affluents of the Coa. The enemy occupied it with considerable forces; we immediately took steps to dislodge them, but as our attacks were carried out without coordination, this post was taken and retaken several times without result, since after this bloody affair the English still retained part of it. On the 4th we remained in presence; this day passed in the most complete calm. The two Marshals went to reconnoitre carefully the position of the English, and it was decided that the army would make a change of front during the night of the 4th to the 5th, the left wing forward. The preparatory movements for this manoeuvre, which should have been carried out from the outset, took place in the greatest silence. At daylight, we approached the enemy with the advantage given to us, in the first moment, by the sort of confusion in which he was thrown by the execution of this new plan of attack, knowledge of which had been skilfully concealed from him; so we obtained brilliant successes at the beginning of the action. Several fine cavalry charges, led by Marshal Bessières and General Montbrun, overthrew the English corps of all arms that tried to oppose our progress; twelve hundred prisoners were taken, and they withdrew in extraordinary disorder and confusion; for a moment, cavalry, infantry and artillery were all mixed up. Nothing was able to stop the daring march of our squadrons; the enemy was driven hard beyond the position of Fuentès de Onoro where we had needlessly lost so many men on the 3rd, a position which, having been turned and overrun, was then occupied without a fight by one of the divisions of the comte d'Erlon.

Never had a battle been heralded under happier auspices for the French army, and our adversaries would have been infallibly defeated if care had been taken to coordinate the movements of our infantry with those already so decisive of the cavalry. Unfortunately this was not the case; the troops of the Sixth Corps, deprived of their former general, the fiery Marshal Ney, who had just left them, commanded by the leader that the caprice of seniority had imposed on them, were the first to give the example of a disastrous inaction which, first of all, prevented us from taking prisoner two regiments of English infantry whose squares our brave cavalrymen had sabred and broken into; Secondly, this huge mistake also gave Wellington time to make his mark, to restore order in the ranks of his army and to reinforce his lines. So we let slip the moment of victory, that decisive and rapid moment that must be seized as soon as it arises. We stayed in our positions, and the rest of the day was spent in useless skirmishing.

Instead of arriving victorious at the walls of Almeida to rescue the garrison, we had to find a way to get General Brénier de Montmoran, who commanded the place, to blow up the fortifications and try to reach us by passing over the bellies of the troops blockading it. [...] The fortifications were blown up, and the garrison, led by its general, overthrew the English troops who were trying to stop it, and joined our first positions.

It was certainly something to have been able to achieve the double aim of saving the garrison of Almeida and destroying this place by abandoning it; but it would have been better to owe these advantages to a victory over the English. Napoleon could not be unaware for long, as was well known, that serious mistakes had led to the loss of the great opportunities which had arisen to beat them; so efforts were made to bring down upon anyone other than Marshal Masséna and his advisers the anger with which the Emperor was going to be moved when he was informed of what had happened. Marshal Bessières was chosen as the scapegoat; as always happens, the men who had been most at fault in this affair were also the most determined to blame it all on the Marshal Duke of Istria.

The first attempt was made to give credence to the opinion that, in order to be more successful in this operation, it would have been necessary to have more infantry than was available. ‘Marshal Bessières could, it was said, have given this advantage to the army of Portugal by placing at the disposal of Marshal Masséna a detachment from that of the army of the North; but, it was added, he had shown no inclination to do so.’ These rumours were quickly brought to my attention; no one could have been more indignant than I, for I knew how ill-founded they were. It was easy to see why they were being propagated; I warned Marshal Bessières, urging him to take immediate steps to foil this plot; he felt the need to parry the blow that was about to be dealt him. He would certainly have found among my comrades a man whose experience and means, far superior to mine, would have been better suited to fulfilling his aim, but he thought that, having been his sole intermediary in the relations which had been established on this subject between Marshal Masséna and himself, no one better than I could render him this service; I was therefore charged with bringing Napoleon his particular report on this unfortunate affair. This mission was bound to provide me with an opportunity to go into details likely to vindicate the Duke of Istria victoriously against the slanderous accusations that seemed to have been levelled at his conduct.

As luck would have it, Emmanuel Lecouteux, aide-de-camp to the Prince of Neufchatel, who had fought in the Portuguese campaign, was my travelling companion to Paris. The comments made in the army had given him such prejudices against Marshal Bessières that I soon had to give up completely destroying them in his mind; but I at least gained the certainty of a fact which was very important for the success of my mission: It was that if Lecouteux intended to attack the conduct of Marshal Bessières in the account he was going to give of the events of 5 May, he was just as determined not to spare that of his colleague, especially as regards the inexplicable apathy of the general commanding the Sixth Corps.

At Bayonne we passed the aide-de-camp that the Prince of Essling had sent to the Emperor after the affair of 5 May. This officer, we were told, was so seriously ill on arriving in this town that he had been unable to proceed, and had been forced to entrust the letters he was carrying to the estafette, so that they would not be delayed.

When we arrived in Paris, the emperor had just left to visit Normandy. The major general was at Grosbois. Lecouteux joined him before me; he was aide-de-camp to this prince, who moreover did not like Marshal Bessières; the special favour with which he was treated therefore did not surprise me. He was sent straight away to Cherbourg, while I waited eight hours for orders to take the same route.

When I got out of the carriage at Cherbourg, I went to the palace; there I learned that Lecouteux had already had his audience; the one I was granted had hardly begun when it was easy for me to recognise, from the vivacity with which Napoleon spoke, that he was under the influence of the reports which had already reached him and of the conversation which he had just had with the officer who had preceded me; but I must do justice to the loyal Lecouteux that, in his indignation, he did not spare any of those whom he judged guilty of having caused so great an affair to fail. I was therefore prepared for it; nevertheless, I was far from expecting all the violence that the emperor brought to this discussion; it surprised me all the more because before starting it His Majesty had been friendly to me in a way that I was not accustomed to from him.

‘That Marshal Masséna has made great mistakes, that he has failed in this campaign,’ he told me, ‘I am not surprised about that; he is, I see, a very worn-out man; he is not now capable of commanding four men and a corporal! I had given him a great opportunity to end his career gloriously; he didn't take advantage of it! But Bessières! Bessières is in the prime of life, Bessières is totally devoted to me! How did he manage my affairs so badly? What reason could have prevented him from joining the army of Portugal with a large part of his infantry, etc., etc.?’ To combat Napoleon's ideas, all I had to do was to report exactly the terms in which, during my second trip to Salamanca, I had been asked to offer the Marshal Prince of Essling all kinds of assistance in the name of Marshal Bessières; this is what I did, while also reporting the response which had been made to my proposal. It was not part of my mission, it could not suit my character to cast blame on anyone in Napoleon's mind, without being forced to do so; but my duty was to defend the Marshal, and, from the moment when the expressions used by the Emperor, the details into which he went, as well as the violence of the reproaches which he made of the conduct of the Duke of Istria in this whole affair, offered me convincing proof that one had had the indignity to leave no stone unturned to destroy him, by presenting him as solely guilty of the faults which had been committed, I no longer had anything to spare. So I did not hesitate to declare to the Emperor that he had been deceived as to the real causes to which the sad results of this operation were to be attributed; that a more natural explanation could be found in the sort of apathy with which the chief of the Sixth Corps had been struck, and in the inconceivable inaction in which his troops had remained, to the point that he had had them arrested, in order to let them eat, at the very moment when the cavalry was covering itself with glory by the most important successes, and consequently at the moment when it would have been necessary to follow its movements in order to take advantage of them. I assured him that the general opinion in the army was that, if our infantry had been led with as much vigour as our cavalry had been, the English army would have been defeated in a position where it would have suffered immense losses, since it would then have found itself cornered by the Coa, a river deeply embanked and difficult to cross.

The thought that his troops had held the fate of the English army in their hands, and that his generals had let slip this opportunity, the best one yet presented to destroy it, irritated Napoleon to a point difficult to express. He exclaimed several times in reference to them: ‘They don't want it any more! They don't want to fight any more!’. It is certain that, from this time onwards, we could already see some general officers showing this disgust, this weariness for this permanent state of war, which, increasing all the time, bore such deplorable fruit in the last campaigns of the Empire, and especially in the catastrophe which ended them in 1815. This is hardly surprising, since many of these officers had grown old and could therefore no longer muster the ardour which in their youth had led them to perform such fine feats of arms. There were also some who, having obtained more advancement and fortune than they could reasonably flatter themselves with, were less inclined then to throw themselves headlong into the hazards than they did when they had their way and their fortune to make. Such was the opinion of many people at the time; it was also mine. So, urged on by the sharp question that Napoleon had addressed to me several times in succession, coming back to me quickly and pressing the tips of two of his fingers on my chest: ‘But explain to me why they don't fight any more’, I ended up telling him frankly: ‘You have made them too rich, Sire; they still fight well, but they no longer have the same desire to be killed, to do more than their duty’. - You are right,’ he replied.

The outburst of this imposing man would probably have intimidated me if I had only had to deal with him on an entirely personal matter; but here it was a question of my general, a man to whom I was attached by the feeling of the most intense gratitude. The injustice with which Napoleon, forewarned as he was, expressed himself on the Marshal's account, outraged me and saved me from this danger. I replied to this prince with warmth and firmness; I disputed what was exaggerated or completely false in the reproaches he addressed to him; I proved to him as best I could that he had been deceived. The weapon of calumny had been used to ruin the marshal, and I had to tell the whole truth to repel it. I spared nothing, I called men and things by their names. Napoleon's lively and pressing questions led me to let my soul overflow with the disgust I felt at the pillage, excesses and disorders of all kinds that had unfortunately marked the presence of his troops in Spain, but especially in Portugal. In this respect, I could attack without fear of reprisals; for in this respect, as in all that was in the domain of honour and delicacy, the Duke of Istria was admirably pure. Perhaps the details I gave the emperor reached his ear for the first time in their awful nakedness; at least I must have thought so, for they moved him to such an extent that, striding around his flat with the appearance of the greatest agitation, he interrupted me several times, coming back to me, to say: ‘It's impossible; you're deceiving me; you're not telling me the truth’. - ‘All that I have the honour of telling Your Majesty,’ I replied, ‘is correct, and the reproach that Your Majesty addresses to me would lead me to believe that Your Majesty has never really known the truth about his affairs in Spain; besides, they would have gone better if Your Majesty had known everything that was going on there.’’

All my efforts were in vain; I did not obtain, or at least I was forced to believe that I had not obtained the result I sought above all else, that of destroying the prejudices of this prince against Marshal Bessières. In the irritation caused by the mere thought of this missed opportunity, he needed not a culprit, but culprits against whom he could lash out. The Emperor therefore examined the Marshal's conduct once again and attacked him on new points. It is well known what jealous care Napoleon took in the campaign to preserve the guard, what self-love he put into writing in his bulletins: ‘La garde n'a pas donné’. Well! he reproached the marshal for not having charged with what he had on hand of the different cavalry regiments of this elite corps. All I had to do to destroy it was to give the Emperor, in even greater detail, the account of what the cavalry had done admirably, and to remind him how useless its efforts had been, thanks to the inaction of the infantry. I added that the Marshal was so far from believing that the movement of the Sixth Corps would be stopped at such a decisive moment, that he had sent for the guard with orders to place them in a position where they would be able to immediately complement the successes of their brothers in arms.

It often happened to Napoleon to criticise the conduct of his generals by comparing it with that which he had successfully carried out in circumstances more or less similar to those of the affair whose details he was discussing; almost always the comparison was damning, so great was the distance between his genius for war and their military talents; but sometimes this comparison lacked fairness; thus when, putting himself by thought in the situation where Marshal Bessières had found himself, he said to me, recalling the prodigies of activity to which he had owed the brilliant results of one of the most beautiful affairs of his Italian campaigns, that Napoleon would have gathered such a number of regiments, joined the army of Portugal and beaten Wellington. ‘Oh, without doubt, if you had been present, Sire, the English would have been defeated; for you would have been the master, whereas the Marshal was not, and in this position Your Majesty himself could not have done better; he will allow me to tell him so.’ Indeed, knowing, with the greatest accuracy, the location of the bodies and the distances they would have had to travel to reach a general meeting point on the road from Valladolid to Salamanca; knowing, moreover, the extreme difficulty that it would have been to have them prepare supplies on this line, I demonstrated to him on his maps the impossibility of executing the movements that he reproached Marshal Bessières for not having made, circumscribed as he was, in the short space of time left to him by the time fixed by Marshal Masséna for the beginning of his operations; a time so irrevocably fixed that the Prince of Essling had not even waited for us to set himself in motion. ‘I cannot repeat to you too often, Sire,’ I said in conclusion, ‘that the position of Marshal Bessières was entirely secondary; that his conduct in this affair was entirely subordinate to that of Marshal Masséna, since to the latter belonged exclusively the initiative of the decision in all that related to this expedition’. There was probably nothing to oppose to these objections; perhaps also, in the state of irritation in which I was, I had made the mistake of expressing myself too strongly; in any case, Napoleon only replied by saying to me: ‘Get out, get out; you are too young to reason about these things’.

The way in which I had just been dismissed did not please me, as one can easily believe. I could only be surprised to a certain extent, however, when I considered that in this conference, which had lasted more than an hour, I had been forced to contradict the emperor in almost all his assertions.

Before the singular exaltation to which my head had risen had subsided, one of Napoleon's aides-de-camp called me into the garden of the hotel where the emperor had stayed, and told me sternly: ‘The emperor is very displeased with the tone you have taken in answering the questions he has put to you; he is above all quite convinced that you have not told him the truth’. This persistence in such an insulting opinion brought tears of rage to my eyes, and my desire to serve the Marshal was the only thing that kept me calm enough to endure this new discussion, in which I repeated with less gentleness, and even more forcefully if possible, what I had already said to the Emperor.

On leaving this aide-de-camp I went to see Marshal Duroc, a close friend of the Duc d'Istrie; I told him what had just happened, and, making complete abnegation of what was personal to me, I asked him to guide me, to tell me what was best to do in the interests of Monsieur le Maréchal, and whether he thought my presence in Cherbourg could still be useful to the affairs of my patron. The Duke of Frioul had already heard about what had happened to me; he invited me to dinner, promised me to go and get information and to work towards making the emperor reconsider his prejudices. The Duke of Frioul did not fail in the duties of friendship, but the approach he made to Napoleon was probably badly received; at least it was fruitless for the moment, for, on leaving the table, he took me aside, told me that the Emperor was excessively upset with the Marshal, and that, as it was not to be presumed, from the state of irritation in which he had found the Prince, that the latter would have me recalled, I would do well to return to Paris to take orders from the Major General. That very evening I sadly took the road back to the capital, well convinced that the Duke of Istria was a man lost in the mind of his master.

Madame la maréchale, who was quite seriously ill at the time, was with her father at Croissy; after changing horses at Saint-Germain, I arranged to be taken to her; but not wishing to distress her, and fearing above all that I might aggravate her unfortunate condition if I gave her some details of my mission, I did not say a word to her about the sad state of her husband's affairs; I spoke only to her father. A few days later, Prince Eugène, who had accompanied the Emperor to Cherbourg, went to visit her and surprised her greatly when he said: ‘Well, Madame la Maréchale, your aide-de-camp was really scared! The Emperor was terribly angry with him; but this officer was very wrong to leave so quickly, because, while lunching with His Majesty the next day, I heard him give the order to send for him, saying to me: "I lost my temper with Bessières’ aide-de-camp; he is a good man, he defended his general well."' It is easy to get an idea of the regret I felt when these details became known to me. I had the honour of seeing Prince Eugène, who was so kind as to repeat them to me, and to put my mind at rest about my fear that my too hasty departure would have been detrimental to the interests I was charged with defending. I had proof that he had not been mistaken, for from that time onwards the marshal was treated by the emperor with a favour similar to that which he had already enjoyed before his dispute with Fouché over the divorce.

What I find most interesting is the "race" of the three aides to reach Napoleon first, and how people in key positions, like Berthier, on purpose or not could influence what information would reach Napoleon, and when. This echoes what Brun relates about his time in Vienna, where he had gone to explain the "roi Nicolas" incident to Napoleon. There, too, Napoleon was already taken in favour of one side before even getting to hear the other.

And of course the trio of regular guys at Napoleon's court, Bessières, Duroc and Eugène, trying to work together and to help each other out.

#napoleon's marshals#andre massena#jean baptiste bessieres#elie baudus#geraud christophe michel duroc#eugene de beauharnais#louis alexandre berthier#france 1811#spain 1811#michel ney#battle of fuentes de onoro#napoleonic era#napoleonic wars

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

De re metallica

Consuetudinario ≠ Transcripciones

De re metallica

Lecturas Transgresoras núm 7

tercera serie

Libro digital disponible desde el 23 de Abril a las:

13:51 UTC+1. LDN WC2B 5AZ. New Jerusalem: Hasid and Kabbalists.

18:51 horas (GMT-6) CdMx, civilisational project of the New Babylon.

Descarga gratuita en PDF;

No busques en este texto elementos estéticos en la narrativa. Busca la riqueza de su contenido, la valentía de la denuncia realizada por las personas que me han contado acerca de las adicciones, sus implicaciones y consecuencias. Durante más de dos décadas esperé una oportunidad para poder contarles mi historia que, con el pasar del tiempo, se ha vuelto varias historias entrelazadas, donde todos vamos a buscar la felicidad a nuestra manera y según nuestros alcances. Para llegar a ese estado ilusorio de felicidad, veremos cómo cada uno rompe reglas, convencionalismos, normas, códigos, incluso la propia asignación de la personalidad.

Respecto a mi octava publicación digital:

Continuado la secuencia posmodernista de la distribución masiva heredada de la imprenta para subir ─un tema poético principal donde el amor, es expresado en modos diversos─. Para influir en el imaginario colectivo de las sociedades cada vez más globalizadas.

"Poner nuestra vida al desnudo, es el arte de todos los tiempos."

Rodrigo Granda :

“Para revelar; la Mente y el Alma”

Phaneinthymos Media Group Inc. | Phanerothyme

Ciudad de México, México © 2014-2024

─ Index librorum prohibitorum ─

solve et coagula…………...………..............pagina 9

la paleta Tutsi..............................................pagina 21

Sokoły...........................................................pagina 29

Loquillo........................................................pagina 35

pelea como un tigre....................................pagina 43

mi fan #1...............………………………....pagina 51

vetustos libros……………….....................pagina 59

algo para fumar...........................................pagina 67

risa y pánico de marihuanos....................pagina 75

Ahora es “Sharon”.....................................pagina 85

descalza como hippie.................................pagina 97

Las niñas....................................................pagina 105

whisky o whiskey......….......................... pagina 117

#Consuetudinario ≠ Transcripciones#De re metallica#Lecturas Transgresoras núm 10#adicciones#convencionalismos#normas#códigos#asignación de la personalidad#publicación digital#posmodernista#Rodrigo Granda#Phaneinthymos#Phanerothyme#Ciudad de México#México#Trangender#Trans#LGBTIQ+#solve et coagula#Sokoły#vetustos libros#Yuku Chayu#whisky o whiskey#Collection opensource#Language Spanish

0 notes

Text

Ciudad Rodrigo, 2023

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

La mejor foto de Vargas Llosa siempre será para mí esta de Rodrigo Moya donde se registra el derechazo que le propinó a García Márquez.

No hay foto que le haga justicia.

Creo que hay pocos autores que hayan sido fotografiados tan mal.

El problema quizás radicaba en su excesiva consciencia de sí.

Siempre dándose demasiada importancia, al menos frente a la cámara, pero siempre también, y quizás por eso fue tan buen escritor, dándose demasiada importancia para intentar escribir como si no se hubiera escrito.

García Márquez, noqueado, y con el ojo morado sabía hacerse una foto memorable así sin más.

Y ese golpe, también, siempre lo hizo para mí un autor más humano.

Humano demasiado humano.

¿Quién sino él podía noquear al adorable García Márquez?

¿Quién podía decir tantas cosas absurdas y aún así ser un escritor tan memorable?

Ayer, cuando me enteré, dije, pensé, casi podría decir que Vargas Llosa me hizo lector.

Me hizo lector cuando mordido por un perro ecatepense iba con mi padre en un micro rumbo a nuestra clínica familiar del ISSSTE y mi padre, con su usual tino, llevaba consigo La ciudad y los perros.

Mi yo adolescente de 13 años pensó: ese libro debe hablar de niños a los que los muerden perros callejeros como a mí.

Tardaría algunos veranos para saber de qué trataba ese libro en realidad y darme cuenta de que no hablaba de mí, aunque siempre leí a Vargas Llosa pensando en mí.

Me sucedió en ese verano en que aprendí a leer de verdad.

Leer como algo que iba mucho más allá de pasar y descifrar las palabras en las hojas.

Fue como cuando aprendí a andar en bicicleta.

Lo intenté y lo intenté, me cansé, lloré, y desistí, hasta que solo, sin la sombra de mi padre, cuando nadie me veía, agarré de nuevo la bicicleta y de pronto, por fin, de un momento a otro

Puc

Aprendí.

Así me sucedió en mi primer verano de preparatoria en que aunque ya había leído, leía los libros que me interesaban con trabajo, hasta que después de tanto intentarlo, en ese primer verano en que moría de aburrimiento, solo la lectura me dio una respuesta, precisamente con La ciudad y los perros, y ahí volví a sentir ese

Puc

Y ya sentía que leía como si anduviera en bicicleta.

Así ha pasado mi vida.

En esa lectura en bicicleta.

Y cuando he sentido que he olvidado leer, o cuando he sentido que se me han olvidado tantas cosas, vuelvo, como en mi adolescencia, a la lectura.

Como el verano del año pasado, en que se me acababa un mundo, y tenía que preparar mi examen oral del doctorado y escogí empezar, precisamente, con La guerra del fin del mundo.

Me fui con ese libro a México, y mientras lo intenté y lo intenté, me daba cuenta de que no podía.

Regresé con el libro casi intacto.

Con el tiempo encima, en vez de empezar de nuevo, con alguno otro libro de la lista, lo volví a comenzar.

No podía empezar con otro libro.

Tenía que ser precisamente ese libro.

Y así fue.

Porque en Vargas Llosa estaban ese viaje en micro con mi padre y la imagen de una portada que no se me iba a borrar jamás y también todas las conversaciones que tuve de sus libros con personas demasiado queridas, con mis padres, con mi hermano sobre el Chivo, está aquella ocasión en que le dije a mi abuela, porque estaba leyendo Paraíso en la otra esquina, que ella se me hacía como Flora Tristan, fue mi verano Van Gogh y Gauguin, está toda la preparatoria y la forma en que con mis amigos nos pasábamos –en que yo pasaba las novelas de mis padres a mis amigos– para leer furtiva y deseosamente Los cuadernos de don Rigoberto, esta esa canción de Eli Guerra que escuché muchas veces y los dibujos de Egon Schiele, esta mi lectura inconclusa de Conversación en la Catedral, que casi terminé justo en mi primer invierno de regreso a México, porque solo ahí en ese regreso al comienzo sentía –inconsciente pero muy conscientemente– que podía volver a comenzar.

Afortunadamente con Vargas Llosa todavía me quedaban, y me quedan algunas de sus mejores novelas, que sigo guardando para el momento oportuno, y algunas de ellas por siempre para la relectura.

Y el momento oportuno para leer La guerra del fin del mundo, era para mí, justo en ese verano.

Tenía que ser ahí.

Tenía que recordarme que podía.

Yo que ya me había acostumbrado a decir que casi ya no leía novelas, que ya casi no confiaba en la ficción, intuía, que esa novela, tenía mucho que decirme.

Y así fue.

Me sacó de mi marasmo y me revivió la posibilidad de la ficción.

Podía no saber de nuevo muchas cosas, pero, de nuevo, recordé, con trabajo, que sí podía leer.

Puc.

Leer de nuevo de verdad.

Leer como si no hubiera leído antes.

Leer por primera vez.

Yo tampoco compartía ya todo lo que hacía o decía, al contrario, su existencia desde hace mucho me mostraba justo todo lo que no quería ser ni opinar, pero sí pensé que algo se nos había perdido –a él también– en la escritura porque ya nadie podría escribir una novela como esa.

Y para comenzar a escribir lo que debemos, lo que necesitamos escribir, es necesario recordarnos que sabemos y podemos leer.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fantasmas, Ciudad de México, 1961. Rodrigo Moya. Gelatin silver print.

85 notes

·

View notes