#Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Less than two weeks until Extra life game day guys! November 2nd, I will be marathon gaming for 24 hours to raise money to help heal kids at Children's Miracle Network Hospitals.

Everyone who donates will be entered into the milestone raffles for prizes like custom totes, OC portraits and more! Donate $10 or more to receive your choice of hand signed prints.

Have something you want to see me play or would like to play with me? Let me know! While Dragon Age and Dragon's Dogma 2 are high on my list of games I'll be playing, I'd love to play with you too! I will be updating my list as I play and streaming to my Youtube from PS4 and PS5.

Follow the link below to donate, browse my game plan and tune in to watch on November 2nd! And feel free to share! The more the merrier!

#extra life#children's miracle network hospitals#children's hospital of Philadelphia#video games#game streams#marathon gaming#fundraiser#charity

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

with all the trash twins talk on the dashboard and in my notes today i just wanna say i still don't think we acknowledge barbara's pill addiction enough.

#ada speaks#iasip#it's always sunny in philadelphia#i forgot frank calls her a pillhead in the christmas special...#and ofc stealing the pills from the children's hospital in dennis & dee get a new dad#but like. shes a disaster beyond the (*frank voice*) hooring and general neglect#i could write five million words on barbara fucking reynolds despite her only being in one fucking season dskjvhsgvjhk#one day.

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Children's Hospital of Philadelphia#gene therapy#hearing loss#otoferlin#US Food and Drug Administration#Akouos Inc#Eli Lilly and Company

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"This year, on Ronan's birthday, I'll be in Philadelphia attending the Era's tour thanks to @taylorswift13. This day is usually difficult for me, but I've found that giving back in some way brings me comfort. As a part of this effort, we'll be making a donation to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and I'll share more information about this soon.

I would be incredibly grateful if you could help me spread the word and invite others to join us on this special day. Let's come together to celebrate and honor Ronan's Day of Love. #ronansdayoflove #fuckcancer"~Mama Maya

#taylor swift#taylornation#taylors version#eras tour#swifties#philadelphia#children's hospital#fuck cancer#Ronan#mama maya

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

since we now know that all those "my blog is safe for Jewish people" posts are bullshit, here are some Jewish organizations you can donate to if you actually want to prove you support Jews. put up or shut up

FIGHTING HUNGER

Masbia - Kosher soup kitchens in New York

MAZON - Practices and promotes a multifaceted approach to hunger relief, recognizing the importance of responding to hungry peoples' immediate need for nutrition and sustenance while also working to advance long-term solutions

Tomchei Shabbos - Provides food and other supplies so that poor Jews can celebrate the Sabbath and the Jewish holidays

FINANCIAL AID

Ahavas Yisrael - Providing aid for low-income Jews in Baltimore

Hebrew Free Loan Society - Provides interest-free loans to low-income Jews in New York and more

GLOBAL AID

American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee - Offers aid to Jewish populations in Central and Eastern Europe as well as in the Middle East through a network of social and community assistance programs. In addition, the JDC contributes millions of dollars in disaster relief and development assistance to non-Jewish communities

American Jewish World Service - Fighting poverty and advancing human rights around the world

Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society - Providing aid to immigrants and refugees around the world

Jewish World Watch - Dedicated to fighting genocides around the world

MEDICAL AID

Sharsheret - Support for cancer patients, especially breast cancer

SOCIAL SERVICES

The Aleph Institute - Provides support and supplies for Jews in prison and their families, and helps Jewish convicts reintegrate into society

Bet Tzedek - Free legal services in LA

Bikur Cholim - Providing support including kosher food for Jews who have been hospitalized in the US, Australia, Canada, Brazil, and Israel

Blue Card Fund - Critical aid for holocaust survivors

Chai Lifeline - An org that's very close to my heart. They help families with members with disabilities in Baltimore

Chana - Support network for Jews in Baltimore facing domestic violence, sexual abuse, and elder abuse

Community Alliance for Jewish-Affiliated Cemetaries - Care of abandoned and at-risk Jewish cemetaries

Crown Heights Central Jewish Community Council - Provides services to community residents including assistance to the elderly, housing, employment and job training, youth services, and a food bank

Hands On Tzedakah - Supports essential safety-net programs addressing hunger, poverty, health care and disaster relief, as well as scholarship support to students in need

Hebrew Free Burial Association

Jewish Board of Family and Children's Services - Programs include early childhood and learning, children and adolescent services, mental health outpatient clinics for teenagers, people living with developmental disabilities, adults living with mental illness, domestic violence and preventive services, housing, Jewish community services, counseling, volunteering, and professional and leadership development

Jewish Caring Network - Providing aid for families facing serious illnesses

Jewish Family Service - Food security, housing stability, mental health counseling, aging care, employment support, refugee resettlement, chaplaincy, and disability services

Jewish Relief Agency - Serving low-income families in Philadelphia

Jewish Social Services Agency - Supporting people’s mental health, helping people with disabilities find meaningful jobs, caring for older adults so they can safely age at home, and offering dignity and comfort to hospice patients

Jewish Women's Foundation Metropolitan Chicago - Aiding Jewish women in Chicago

Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty - Crisis intervention and family violence services, housing development funds, food programs, career services, and home services

Misaskim - Jewish death and burial services

Our Place - Mentoring troubled Jewish adolescents and to bring awareness of substance abuse to teens and children

Tiferes Golda - Special education for Jewish girls in Baltimore

Yachad - Support for Jews with disabilities

#atlas entry#please add any more you know of an especially add fundraisers for you or people you know#if there are any fundraisers for synagogues please add those as well#jew#jewish#judaism#jumblr#punch nazis

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

CONJOINED.

the symposium by plato / attack of the clones (2002) dir. george lucas / “da selby pt 2” by hozier / interview with the vampire (2022) s1e7 “the thing lay still” / revenge of the sith (2005) dir. george lucas / revenge of the sith by matthew stover / wuthering heights by emily brontë / “claw machine” by sloppy jane and phoebe bridgers / wild space by karen miller / hannibal (2013) s3e6 “dolce” / dead ringers screenplay by norman snider and david cronenberg / dead ringers (1988) dir. david cronenberg / children’s hospital of philadelphia

#another extremely weird post comparing a romantic relationship to conjoined twins but it’s anidala this time#once again it’s about the transcendent closeness i’m not implying anything distasteful don’t get mad at me i’m 0 years old#yeah i reused some of the dead ringers stuff. i really like dead ringers. dead ringers is applicable to many things#sorry for being a cronenberghead it will happen again#web weaving#anidala#anakin skywalker#padmé amidala#padme amidala#star wars#star wars prequels#attack of the clones#revenge of the sith#interview with the vampire#dead ringers#webweaving#web weave

150 notes

·

View notes

Text

Old news, but something people should remember

Never let them tell you "We didn't know covid was so bad" or "It's mild for kids." We knew.

Also preserved on our archive

By John Anderer

PHILADELPHIA, Pa. — The news about coronavirus and children just got a lot worse. A troubling study by researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia reports a “high proportion” of children infected with SARS-CoV-2 show elevated levels of a biomarker tied to blood vessel damage. Making matters worse, this sign of cardiovascular damage is being seen in asymptomatic children as well as kids experiencing COVID-19 symptoms.

Additionally, many examined children testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 are being diagnosed with thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA). TMA leads to clots in small blood vessels and has been linked to severe COVID symptoms among adult patients.

“We do not yet know the clinical implications of this elevated biomarker in children with COVID-19 and no symptoms or minimal symptoms,” says co-senior author David T. Teachey, MD, Director of Clinical Research at the Center for Childhood Cancer Research at CHOP, in a media release. “We should continue testing for and monitoring children with SARS-CoV-2 so that we can better understand how the virus affects them in both the short and long term.”

The complex connection between kids and COVID It’s fairly well established at this point that most children who contract coronavirus experience little to no symptoms. However, a small portion of young patients develop major symptoms or a post-viral inflammatory response to COVID-19 called Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C).

TMA in adults has a connection to more severe cases of COVID-19. Scientists believe the component of the immune system called “complement cascade” helps to mediate TMA in adults. The complement cascade is supposed to enhance and strengthen immune responses when a threat is present, but it can also backfire and lead to more inflammation. Up until now, the role of complement cascade during childhood TMA hadn’t been investigated.

To research the topic of “complement activation” in kids with SARS-CoV-2, researchers analyzed a group of 50 pediatric COVID-19 patients between April and July 2020. Among the group, 21 showed minimal to no symptoms, 11 experienced severe symptoms, and 18 developed MIS-C.

To search for complement activation and TMA among each patient, researchers used soluble C5b9 (sC5b9) as a biomarker. Scientists have used this substance for quite some time to assess the severity of TMA after stem cell procedures. In brief terms, the higher the level of sC5b9 in a transplant patient, the greater their mortality risk.

No symptoms doesn’t mean there’s no problem Study authors discovered elevated levels of C5b9 in both patients with severe COVID-19 and MIS-C. While this didn’t surprise researchers, they did get a shock from seeing high levels of C5b9 among even asymptomatic youngsters.

Some of the lab data regarding TMA had to be obtained after the fact. This meant researchers didn’t have a complete dataset to work with for all 50 studied patients. Among 22 patients researchers did have complete data for, 86 percent (19 children) were diagnosed with TMA. Every child had elevated levels of sC5b9, even those without TMA.

“Although most children with COVID-19 do not have severe disease, our study shows that there may be other effects of SARS-CoV-2 that are worthy of investigation,” Dr. Teachey concludes. “Future studies are needed to determine if hospitalized children with SARS-CoV-2 should be screened for TMA, if TMA-directed management is helpful, and if there are any short- or long-term clinical consequences of complement activation and endothelial damage in children with COVID-19 or MIS-C. The most important takeaway from this study is we have more to learn about SARS-CoV-2. We should not make guesses about the short and long-term impact of infection.”

The study is published in Blood Advances.

Study Link: ashpublications.org/bloodadvances/article/4/23/6051/474421/Evidence-of-thrombotic-microangiopathy-in-children

#mask up#covid#pandemic#covid 19#wear a mask#public health#coronavirus#sars cov 2#still coviding#wear a respirator

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Costa Nostra- pt 21

Cowritten w @schemmentis

Summary: You find yourselves falling into this new life. Meanwhile, things back at home change.

WC: ~2.05k

The girls love their new school- something you’re eternally grateful for. You manage to find a new business to manage the accounts of, free of any secondhand business on the side while your wife falls back into teaching like she used to before she left to open her restaurant.

This life is different, but it isn’t unwelcome. You easily blend in to the always lit and alive city. You spend much of your time out exploring, finding new special spots and diners to take your girls. You even join a new perish- one that you know will never quite feel like the one back in Philly. The people there are nice enough, but no one will ever be Barbara and Gerald Howard.

Meanwhile, back in Philadelphia, Gerald Howard brings the ledger into his place of work. He calls up the two who handled your case to begin with and brings them in while his wife is there.

Together, the four of them promise to take down the mafia. Neither agent lets it slip that the four of you are still alive; Danik almost does though at Barbara’s shed tears for your twins.

Instead, Danik puts herself into the work at the end of your case. The dismantling of the mafia in the city. A workaholic already, she pushes herself even further. It's only Shaw that reminds her to sleep, at least for an hour or two. To eat, even just a few bites. Danik might know the truth of you and your family being alive. It doesn't negate that there are people out there who would stoop to order the hit. To include two very young children in that hit.

They start back at the very beginning. Working through your old salon and Melissa's cherished restaurant. Neither look the same now, a few months since your ‘deaths’. It's far more obvious now that both locations are fronts. Whoever is running things is getting sloppy. Danik guesses because they've run out of people they can use to hide behind; like you and Melissa were. The members of Cosa Nostra are front and center now. Running in and out of both the salon and restaurant at all hours.

“That definitely wasn't as good as the last time we were here.” Shaw mutters as he follows Danik out of Twelve Tables.

“I'll give her this much;” Danik starts as she gets into their unmarked car. “Melissa was much better with the food than whoever is back there now.”

Shaw sighs as Danik begins driving back down the street. “Back to the salon? Again?”

“Yes. We're closer there than we are with the restaurant. Besides, I called Andretti. He's still undercover and is with the Italians. He's going to try to nab Luca tonight. I need to be there.”

“Grace, you need a break.” Shaw says quietly from the passenger seat. It's rare for them to use their first names, but in the last few months it's grown in frequency. He silently blames a former Melissa Schemmenti and her teasing him from her hospital bed.

He hasn't asked his work partner out. He won't until the case is done. Still, he's been driven to show his affection for her in trying to make sure she takes care of herself at least while they work. Because if people around here are okay killing kids; there's a good chance they're more than okay with killing a federal agent or two in the right circumstances. Circumstances they're pushing their luck on every day and have been for a long time now.

“Ben.” Agent Danik says, almost sounding through her teeth. She's grown from looking at him with a glare for pulling out first names to returning the use of them. At least sometimes. It's progress. “Not tonight, alright? Just…tonight could be the break we need. Leave me be about the rest shit. Just for tonight.”

Agent Shaw sighs. “Just for tonight.” He reluctantly agrees as his partner parks their car adjacent to the salon. “But tomorrow, you’re sleeping. I’ll drag you to bed myself if it means you’ll get sleep.”

He doesn’t miss the blush that creeps into his colleague’s cheeks.

From here, they can see the front through the large glass windows. The very few clients and hair stylists moving about the front. They can also see down the side alleyway. The door you told them any side business went in and out of. The occasional meeting was held in the alley, too.

Tonight, there's a figure leant against the brick next to that door. The dim glow of a cigarette seen each time a draw is taken from it. In the light of dusk, it isn't easy to make features from where the figure stands. Though the height and build matches Luca Bellino.

“There's Andretti.” Grace says with a nod to a man walking down the sidewalk, from the direction of Twelve Tables.

Andretti turns down the smaller path of the alley way. It's then that the figure near the back door of the salon drops the cigarette, stomped out beneath a shoe. The figure steps closer to the street to meet the undercover officer halfway. Just enough distance for the street lamp to illuminate features. It's without any doubt Luca Bellino.

Shaw and Danik watch silently over the next few minutes. The conversation can't be well heard from their car, though they're certain Andretti has some recording device hidden. It looks like a normal conversation between friends. Like two men chatting and catching up over newly lit cigarettes. Until finally, Andretti pulls a thick, nearly over-filled, envelope from beneath his jacket and passes it to Luca.

Danik is already throwing open her car door and tugging her holstered weapon out as she crosses the street.

Shaw scrambles to follow after her, not bothering to even close his car door. He jogs to catch up to her, pulling out his own weapon in case.

“Freeze!” Danik calls once she's on the sidewalk. “Put your hands where I can see them.”

Both Luca and Andretti raise their hands in compliance. Danik nods for Shaw to cuff Andretti to maintain his cover as much as they possibly can. “You're under arrest.” Danik says as she tugs Lucas's hands behind his back to cuff him herself.

“The fuck?” Luca spits, turning to Andretti in a look of panic. He tries to look over his shoulder at Agent Danik. “What for?”

“Money laundering.”

“Money laundering?!” the nephew of Melissa shouts. “This isn’t money laundering! He owes me money for buying my car!”

“From a fat manilla envelope in a dark alleyway?” Danik shoots out. “Sure. We’ll believe it when we see it.”

The two men are taken into the station, and Andretti is a great actor it turns out. He huffs about the entire time that he knows Luca can hear him. And then they’re separated, and the undercover cop breathes a sigh of relief.

“Jesus, Shaw,” Andretti sighs as he rubs at his wrists. “Did you have to cuff me that aggressively?”

“Maintaining the story,” Shaw chuckles. “Sorry man.”

“It doesn’t matter,” Danik rolls her eyes at the two. “Shaw, get in there and get him to say something- anything. About the Schemmentis, about the hit on Bobby, about Cosa Nostra. Anything.”

Benjamin Shaw would be lying to himself if he said that Grace Danik ordering him around like that wasn’t hot. He obliged her orders, storming into the interrogation room.

As soon as he’s in there, Luca spills everything aside from the fact that he’s the one who was contracted to kill you and your family. Of course, he only offers up the information at a deal of not being put into jail and only paying a small fine in comparison to what he would have actually had to pay if not for the information.

Danik’s eyes raise at all of this information coming so freely. He tells who is in charge, the way that the Schemmenti family found their way into the mob- the fact that you were tied into the Irish side of it all. He takes down Tony and Uncle Dominic, and everyone else who was involved. Luca tells where they’re all planning on meeting tonight.

The police hold Luca until they can round up everybody within the family. Danik and Shaw are able to come out of the raid without a scratch on them, although other members of the family aren’t so lucky. They manage to keep both Tony and Uncle Dominic alive- if only for the information that they hold. Others are slain as they all turn on each other and try to find out who the rat is, pulling guns out of their coat pockets and firing without hesitation.

The next day, Mickey is set free from prison. He knows that originally, you, Melissa, and the girls were supposed to be the ones to come retrieve him and bring him out into the world for the first time in years. Instead, it’s Kristen Marie. He’s thrilled to see his blonde sister, but what he really wants is to see the four of you.

When he cries, Kristen can only pat his arm in an awkward fashion. She thinks his tears are being shed because he’s finally on the outside- only until he chokes out Melissa’s name and your own does she understand why he breaks down on the sidewalk of the prison building. He drops to his knees as ugly sobs wrack through his body. He was looking forward to the day that he would be able to hug your girls for the first time as a free man- to be able to pick you up and spin you in a circle without the guards looking at him as if he were clinically insane. All he wants is to be able to punch his oldest sister in the arm with a shit eating grin without having to worry about being chastised by security.

That Sunday, he finds himself slipping into the church that he knew the four of you attended. He recognizes Barbara Howard right away. As he makes the sign of the cross over his chest, he looks up at the ceiling- as if he could see that the four of you were looking down on him. He goes to slide into the pew, but a quick hand stops him.

“This seat is taken.”

“Barbara,” Mickey whispers softly through the sermon. Only then does the woman look at Melissa’s brother and see eyes that resemble your wife’s so clearly.

“Mickey?” she gasps softly as she pulls her hand away from the spot and invites him in.

The three, Mickey and the two Howards, end up at your diner in the booth that you always sit in. For the first time in months, breakfast isn’t a silent affair. Mickey trades stories about his sister and you from your past while the Howards tell him about what the four of you were up to for all the time he was behind bars. It’s therapeutic in a way for all three of them. He promises to meet them again for the next sermon.

That's the start of a new tradition. One similar to the one you, Melissa and your girls had with the Howards. Sunday morning services, Sunday brunch. Mickey fills the pew for you. They don't let anyone else sit in that last pew. After a few weeks, they don't even have to tell anyone the seats are taken. Your old parish knows not to even try.

@thesapphictimelady @marvel210 @itisdoctortoyousir @morgana-larkin @thesamesweetie @doesthatsuggestanythingtoyou @marvels--slut @gwennybriggs @megamultifandomtrashposts @lemz378 @http-sam @melissaschemmentisbranzino @imaginesmultifandoms @sexysapphicshopowner @lilfartbox1 @maybe-a-humanbean @imlike-so-gaydude @sapphicxrat @a-queen-and-her-throne @sunsol-22 @notinmyvocab @melanielaufeyson @dvrkhcld

#abbott elementary#abbott elementary fanfiction#abbott elementary fanfic#melissa schemmenti fanfiction#melissa schemmenti fanfic#melissa schemmenti x you#melissa schemmenti x reader#melissa schemmenti

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

In an age that witnessed considerable support for social improvement, public schools often took center stage. By the 1830s, a chorus of reform-minded people began to sing the praises of free, tax-supported schools: Thaddeus Stevens, later a prominent Republican activist in Pennsylvania; Catharine Beecher, advocate of more educational opportunities for women; Caleb Mills, an evangelical minister who later became Indiana's leading common school advocate; and even notable Southerners, who faced the greatest opposition and whose efforts bore the least fruit. Enthusiasm for social improvement through education flourished. Since the turn of the century, countless pamphlets, speeches, reports, petitions, testimonials, newspaper editorials, books, and articles had promoted the importance of education in a republic. A few dozen educational periodicals also popularized the cause of learning by promoting a class-inclusive school system, especially for white children.

In Philadelphia, New York, and other cities, the editors of workingmen's newspaper - the voice of the skilled artisan minority - despaired over the fate of youth as apprenticeships declined and unskilled factory labor increased; they endorsed instituting a common system and eliminating the stigma attached to free schools. "I think that no such thing as charities should be instituted for the instruction of youth," wrote one articulate worker in the Mechanics' Free Press in Philadelphia in 1828. He favored free schools dependent not on "private charities" but "founded and supported by the government itself." One Ohioan added, "Unless the Common Schools can be made to educate the whole people, the poor as well as the rich, they are not worthy of the support of the patriot or the philanthropist." "Give to education... a clear field and fair play," said a recent immigrant in A Treatise on American Popular Education in 1839, "and your poor houses, lazarettos, and hospitals will stand empty, your prisons and penitentiaries will lack inmates, and the whole country will be filled with wise, industrious, and happy inhabitants. Immorality, vice and crime, disease, misery and poverty, will vanish from our regions, and morality, virtue and fidelity, with health, prosperity, and abundance, will make their permanent home among us.”

Born in an age when millennial ideals, such as universal peace and prosperity following Christ's imminent return to earth, influenced wide sectors of the population, the common schools became a useful barometer of the extensive social changes that transformed the nation before the Civil War. Cities, factories, and foreign immigration generated moral panic and social fears among many northern reformers, whose search for solutions to public ills centered on a more expansive public school system. Reflecting the contradictory passions of the reformers, schools not only favored greater access to literacy and academic study but simultaneously downplayed intellectual achievement by elevating the moral aims of instruction. America's ambivalent attitude toward the life of the mind and scholarship thus found expression in the nation's emerging school system, where character development and moral uplift took precedence even as lifeless instruction in academic subjects predominated. Setting a pattern that long endured, reform-minded citizens increasingly assumed that individual welfare and social progress depended on an extensive network of public schools.

william j. reese, america's public schools from the common school to "no child left behind"

#posting this mostly because as you all know#i find 'public schools were designed to create mindless capitalism robots'#an unbearably annoying common take#but i think it's also worth considering that like#the idea of public schools as key to the well-being of a nation#is something we take for granted now#but was like... invented... with the invention of public schools... about 200 years ago#it's not a lesson drawn from something that actually happened. lol.#media 2k24#edublogging#sigh... i'd resisted making a tag for that on this blog but the evidence is against me i fear...

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Medical Behavioral Unit

#architecture#art#decor#design#frutiger aero#frutiger eco#frutiger metro#graphic design#hospital#leaves#nature#pennsylvania#philadelphia#photography#trees#usa#us

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Extra Life 2024 Part 1 - Dragon Age The Veilguard

#dragon age#dragon age veilguard#dragon age veilgaurd spoilers#extra life#marathon gaming#video games#game stream#charity#fundraiser#children's hospital of philadelphia#children's miracle network#ftk

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

More from Tinderbox: HBO's Ruthless Pursuit of New Frontiers, by James Andrew Miller:

ANNE THOMOPOULOS: Richard Winters, who commanded Easy Company, was very reticent about being involved in the project. Richard was very conservative and very suspect of Hollywood. He didn't want to share his life. At the end of our lunch I said, "Regardless of what you decide, I need to thank you because my mother-and father-in-law were married during the war and decided that they wouldn't have children until they knew their children would be okay. My brother-in-law was born in a bombing seven months after you landed on the beach in Normandy. I owe you my life. My daughter is a result of your efforts and she's my greatest joy. Whatever hap-pens, I am eternally grateful." Carmi told me it was because of that that he changed his mind.

MARA MIKIALIAN: I had this idea to pair actors and veterans, so we flew actors to where the veterans were. The one who portrayed Babe Heffron was from Scotland-Robin Laing-and had never even been to America. While Robin is on his way from Scotland to Philadelphia, Babe ends up in the hospital. So Robin landed and I greeted him and said, "Do you want to rest? You want to go see the Liberty Bell? You've never been in America before." He said, "Bring me to Babe." We immediately went to the hospital and of course Bill was there because those two were inseparable. It was important to Babe that Robin and also Frank see their world. Bill basically set out an itinerary for us, drove us all around in his car with his only one leg that he had. We went to the restaurant where they had breakfast every day. We went to the Irish bars. We did that with four other pairings. Honestly, to this day, I think I'm still so proud of that story and how it came out [in People magazine] and how the actors and the veterans felt about it.

TONY TO: A big ingredient of the magic was that the actors were talking to the people they were playing. The spirit was everybody wanted to honor them. You would have a call sheet with the characters who were supposed to be there, but then two or three other actors who had a day off would come and they would be in wardrobe. They would say, "I talked to my guy yesterday. He said, 'I was on that patrol. You don't have to give me any lines, but we want to do right by them. We're going to be here even if we're treated like extras."

ANNE THOMOPOULOS:

To get on that train was really touching, and I realized something about the bond that happens between soldiers that I had never really understood before. They basically said, "We love our wives, our kids, their families. But the love we have for each other is different." These men had faced death over and over again together.

According to Tony To, BoB never used a stunt man, everything was done by the actors.

David Frankel directed and shot Ep 7 The Breaking Point and Ep 9 Why We Fight. It took 55 days of production, for two hours of television. The longest schedule Frankel had on a feature film he has made is 55 days.

Originally BoB had 12 episodes but it’s over the budget so they had to cut out 2 from the bible.

38 notes

·

View notes

Photo

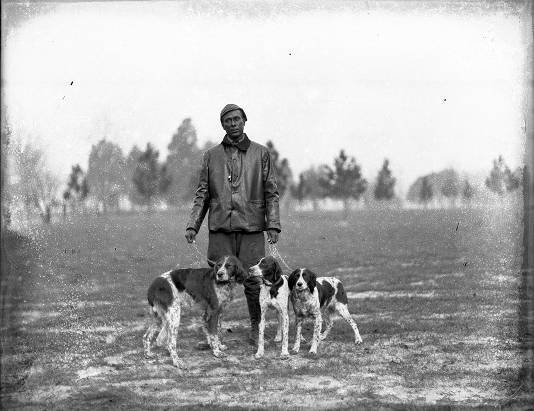

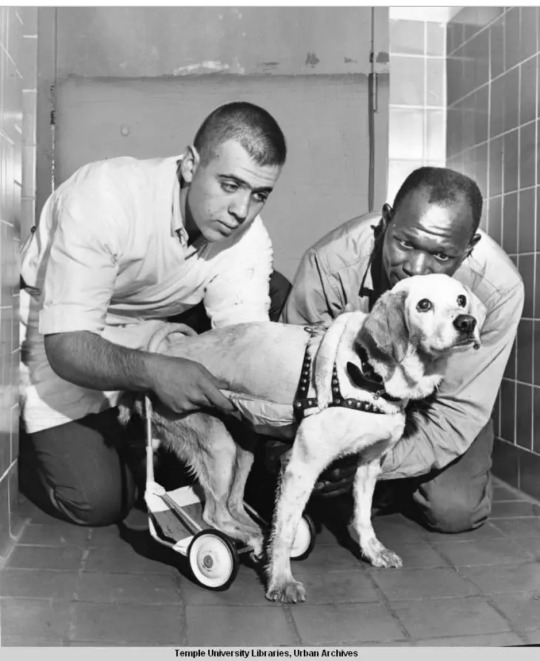

There’s a deeply rooted misconception that the only history that Black people have with dogs is a violent one. We recall the stories of slave patrols (the early prototype of our present law enforcement in the United States) enslaved people and free people of color through the swamps and forests with bloodhounds. Our minds turn to images of dogs being weaponized by white officers to intimidate and injure activists and community members. We reinforce narratives that nurture this haunted history of violence. But that is not the full story.

So here’s a little community history that show Black folk being pet parents and companions to furbabies~

- Bartel and Vashti Mosby, sitting together in front of their home with a small terrier in Lincoln, Nebraska (1910 - 1925)

- A young girl and elder stand on porch with cat (1928)

- Unidentified woman sitting with dog (1910)

- Children play with dog on the beach in Apalachicola, Florida (1895)

- A hunter stands with three hunting dogs in Georgia (1926)

- A mother surrounded by three children and a dog in rural Wilcox County, Alabama (1910-1919)

- A small child smiles down two dogs in Lincoln, Nebraska (1919-1925)

- At West Park Animal Hospital in West Philadelphia (born and raised~) a multi-racial team including Howard Krawitz and Whitfield Thompson (pictured) crafted a prosthetic cart for a puppo named Peanuts (1964)

- Two women at a picnic show off their smiling pitbull terrier (1910-25)

- Two children with dog in Boston, Massachusetts

Collection sourced from Florida Memory | Smithsonian | Library of Congress | New York Public Library | Nebraska Public Library | Boston Public Library

#for my afrofolio of period dramas#black history month#BlackExcellence365#people#our history is your history#yes i did make a fresh prince joke#in west philadelphia born and raised~

246 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writing Resources for Shazam Fanfics:

Revan Foundation on Foster Care.

Children's Hospital of Philadelphia on Foster Care.

Chapin Hall on various aspects of the foster system.

Annie E. Casey Foundation on aging out of the foster system.

Metropolitan Museum of Art on Greek Mythology. (This is just a basic overview)

Greek Traveltellers on Ancient Greek Mythological Monsters. (This is more specific look at monsters.)

Map of Philadelphia.

Hope this helps someone.

162 notes

·

View notes

Text

At age 17, Donnell Drinks was one of many young men in Philadelphia who went to prison for life without parole. Today, the city has resentenced more of those prisoners than any other jurisdiction.

Published Aug. 15, 2023Updated Aug. 18, 2023

Donnell Drinks woke up one morning to banging on his door in the projects of North Philadelphia. It was the late 1980s, and Mr. Drinks, who was 15 and the oldest of three boys, had nodded off after taking his youngest brother to school. He should have been at school himself, but he had stopped going earlier that year. It wasn’t a truant officer at his door, though — no one had ever come knocking about that. Instead, sheriff’s deputies were waiting outside. They were there to evict his family.

The officers told him to get out, not bothering to ask if there was an adult around, which there wasn’t. Mr. Drinks’s dad had abandoned the family a decade earlier, and his mom was in the throes of crack cocaine addiction. For years, Mr. Drinks had been raising his younger brothers, and he had just become a father himself. He’d dropped out of school to support his family by selling drugs, a transition that felt so natural he hardly remembered how it happened.

Groggy and panicked, Mr. Drinks scanned the apartment for essentials, stuffed a shopping cart with clothes for his brothers and wheeled the cart up the road to his grandmother’s overcrowded rowhouse. The officers never asked where he was going.

“There was not one adult that said, Hold a minute. We need to call somebody,” Mr. Drinks said. “Not one adult said, That’s a child.”

At the time, Black teenage boys like Mr. Drinks were being treated less as children in need of help and more as if they were threats to society itself. Crime was rising nationwide, particularly in Philadelphia, where, in 1990, the city recorded 500 murders in a year for the first time. It was a terrifying period, especially for people living in poorer neighborhoods where the violence was worst. But the rhetoric, perpetuated by public officials and overheated headlines, suggested that a new morally depraved generation of teenagers — particularly Black teenagers — were to blame. This idea gave rise to the “superpredator” era and a raft of laws cracking down on juveniles that followed.

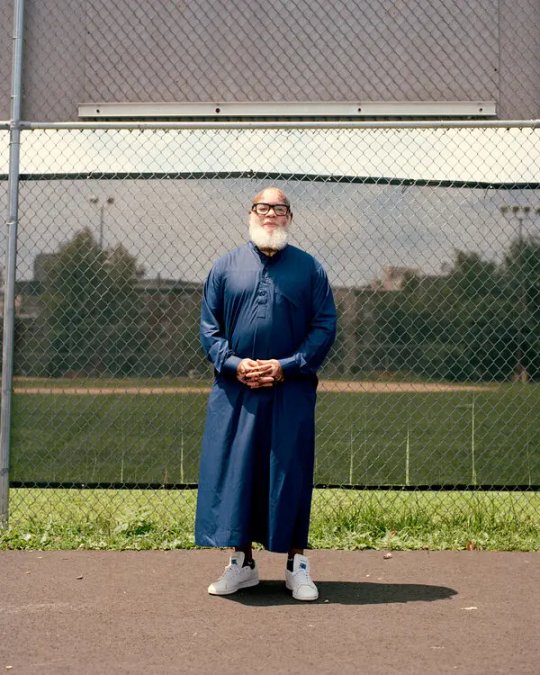

Mr. Drinks, now 50 years old, is a small man with a stocky frame and a warm, gaptoothed smile. He keeps his salt-and-pepper beard meticulously fluffed. An animated storyteller who is quick with a metaphor and a motivational quote, he becomes guarded when describing his upbringing — not just because it’s painful, but because he doesn’t want anyone to think he’s trying to justify what happened next. “This is context,” he said, “not excuses.”

In February 1991, when he was 17, Mr. Drinks and his 22-year-old girlfriend, who was a police officer, tried to rob a man named Darryl Huntley. They staked out Mr. Huntley’s house and forced him and his fiancée inside at gunpoint. That violent act led to others. Mr. Drinks stabbed Mr. Huntley, fatally, and was shot himself. Mr. Drinks was arrested while he was in the hospital recovering from his injuries.

By the time Mr. Drinks was brought to trial for Mr. Huntley’s murder, Philadelphia had a new district attorney: Lynne Abraham, a former judge who went on to hold the office for nearly two decades. Pennsylvania law already made life sentences mandatory for first- and second-degree murder convictions, but Ms. Abraham responded to the era’s surge in violent crime by aggressively pursuing the death penalty, an approach that once earned her the moniker the “deadliest D.A.”

She also called for tougher punishments for juveniles. In 1994, she pushed for legislative changes to give prosecutors more power to charge juveniles as adults. “You don’t get any bonus for being under a certain age,” she told The Philadelphia Inquirer at the time. The next year, the state passed a law that required prosecutors to treat children 15 and older as adults when they were charged with certain crimes.

Though Philadelphia had already sentenced many young people to life without parole, under Ms. Abraham’s watch — and with the city’s murder rate remaining high throughout the ‘90s — the number getting that sentence in Philadelphia rose quickly. For some, it may have been a deal worth taking to avoid the death penalty.

Mr. Drinks was tried as an adult and initially sentenced to death. In 1993, his sentence was reduced to life without parole. (His then-girlfriend, who received the same sentence, remains in prison.)

He most likely would have died in prison, but while Mr. Drinks was behind bars, a national effort began to rethink the culpability of young people in the eyes of the law. In the 2005 case Roper v. Simmons, the Supreme Court struck down the death penalty for minors, leaning heavily on new scientific research that showed — “as any parent knows,” Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote — that young people are not like adults. They are more impulsive, reckless and susceptible to persuasion.

The court did not question that minors should pay for committing heinous crimes, but in banning the most severe punishment, it affirmed the possibility “that a minor’s character deficiencies will be reformed.” Real change, Justice Kennedy suggested, was possible.

Mr. Drinks had been in prison for more than a decade when the Roper decision came out. Then one day, a Philadelphia lawyer named Bradley Bridge traveled to the upstate Pennsylvania prison where Mr. Drinks was locked up, and explained to him and the other men who had been given life sentences as boys what the ruling could mean for them.

Striking down the death penalty for minors was only the beginning, Mr. Bridge said. Soon, he predicted, the court would apply the same logic to outlaw mandatory life sentences for juveniles too, potentially giving Mr. Drinks and others serving such sentences a shot at freedom — and giving the city of Philadelphia a chance to rewrite its legacy.

A long list of friends

Mr. Bridge had been delivering his speech inside prisons throughout Pennsylvania for months before Mr. Drinks heard him speak. Mr. Bridge worked for the Defender Association of Philadelphia and had spent nearly three decades representing prisoners who were appealing their sentences. When the Roper ruling came down, he was involved in the case of a teenager facing a mandatory sentence of life without parole. He understood immediately the opportunity that the Supreme Court’s ruling presented not just for his client, but for scores of prisoners.

For Mr. Bridge, it meant pursuing a novel legal theory that might help dismantle what he viewed as a particularly unjust part of the justice system. “Children are children, and they make mistakes,” Mr. Bridge said. “But they grow and change.”

Mr. Bridge began the enormous undertaking of compiling a list of all the prisoners in Pennsylvania who were sentenced to life as minors. No one in the state had ever kept track of this group, who came to be called “juvenile lifers” in the courts and “child lifers” by some of the inmates themselves.

He expected the list to be long. He didn’t expect it to eventually include more than 500 names, nearly one-fifth of the more than 2,800 child lifers in the country. More than 300 of them had come through Philadelphia’s system, making a city with less than 1 percent of the country’s population responsible for more than 10 percent of all children sentenced to life in prison without parole in the United States. No other city compared. Even more glaring: More than 80 percent of Philadelphia’s child lifers were Black. Nationally, that figure was roughly 60 percent.

Racism “undoubtedly occurred in every phase of the criminal justice system,” Mr. Bridge said. “This created an opportunity to try to fix things that had been broken.”

After the Supreme Court outlawed the death penalty for minors, Bradley Bridge started encouraging inmates sentenced to life as children to prepare for the possibility that the court would eventually revisit the constitutionality of their sentences, too.

His partner in this work was Marsha Levick, who had co-founded the Juvenile Law Center in 1975 as an idealistic young graduate of Temple University’s law school and gone on to become one of the nation’s foremost experts on juvenile sentencing.

Mr. Bridge and Ms. Levick began traveling the state, arranging meetings with the people on Mr. Bridge’s list and adding names as they went. Mr. Bridge’s first stop was Graterford, a maximum-security facility outside of Philadelphia that, at the time, held more child lifers than any prison in the state. Dozens of men crowded into Graterford’s chapel to hear what Mr. Bridge had to say.

“People wanted to know what was coming down the pike,” remembered Kempis “Ghani” Songster, who was in the room that day. “Is this a ray of light flickering on?”

At age 15, Mr. Songster stabbed another teenager to death in a crack house. Both were runaways working for the same gang. He was given a life sentence for his crime, but it wasn’t until that meeting in 2006, nearly two decades after he went to prison as a scrawny kid who couldn’t grow a beard, that he realized how many other lifers at Graterford had also arrived as teenagers.

“It was like, Whoa, he’s been here since he was a kid, too?” Mr. Songster said. “A lot of us who were child lifers didn’t really know that we were in a distinct class.”

There had never been a reason to talk about age. The courts had treated them as adults, and if anything, being marked as a child in a violent adult prison would only have made them more vulnerable. Now, there was power in the identity.

The child lifers inside Graterford began organizing. They quickly formed a committee called Juvenile Lifers for Justice, which met weekly to discuss the evolving law and science around adolescent development. They drafted pamphlets, circulated newsletters to other prisons and their family members, and kept one another motivated around their common cause.

These conversations also started to change how some of the men thought about why they had committed such serious crimes.

Mr. Songster said he never felt “entitled” to be free. “I can’t wash the blood off my hands that’s on my hands,” he said. But the emerging research, which showed brains aren’t fully developed until people get into their 20s, gave him new understanding. “It made me curious about myself,” Mr. Songster said of the research. “I knew I was a good person, but I couldn’t reconcile the person that I became and I know I am with the person that committed that horrible act.”

The child lifers were also reaching out beyond the prison walls. They invited politicians to visit Graterford and partnered with nonprofit organizations to distribute supplies to local schools.

“We were always trying to break that wall down so people could see we’re humans,” said Don Jones, who was also sentenced as a minor and was the president of Graterford’s N.A.A.C.P. chapter during this period.

Mr. Bridge and Ms. Levick became frequent fixtures at the prison. At each of these visits, Ms. Levick was struck by how the men — imprisoned at such a young age and last in line for any prison edification programs because of their status as lifers — had mastered the nuances of the law and were orchestrating a statewide grass-roots movement from inside prison. “Their desire to come home was real,” Ms. Levick said. “It was palpable, and it made you want to do more.”

“We were always trying to break that wall down so people could see we’re humans,” said Don Jones, who was locked up at Graterford and has since been released.

Mr. Drinks had spent 10 years at Graterford, but after he was transferred upstate, newsletters coming out of Graterford and messages passed along from old friends became his lifeline. Without a lawyer of his own, he kept his case alive by adapting draft legal petitions circulated by Mr. Bridge. And he documented his accomplishments in prison — articles he’d written, certificates he’d earned, thank-you notes from the nonprofits he’d raised money for — until he had three manila envelopes’ worth of records illustrating all the ways he’d grown.

Still, he never quite let himself believe that Mr. Bridge’s prediction would pan out. He wanted to be prepared, but he was also prepared to be let down.

“It’s like throwing water out of a boat that’s sinking,” Mr. Drinks said. “You’ve got to do it anyway, because if you don’t, the water’s going to get you.”

Throughout this period, lawyers around the country, including Ms. Levick and Mr. Bridge, were bringing new cases, trying to apply the rationale in the Roper ruling to other kinds of sentences for juveniles. At the national level, a key leader in this work was Bryan Stevenson, founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit.

Mr. Stevenson saw a connection between the superpredator era and the overwhelming number of young Black boys who had been locked away for life.

“You had these criminologists going around saying that some children aren’t children. Some kids look like kids, but they’re really, quote, superpredators,” he said. “That narrative was so prevalent, so persuasive, that you see states all over the country lowering the minimum age for trying children as adults.”

In 2008, the Equal Justice Initiative found 73 children who had been given sentences of life without parole when they were 13 and 14 years old. And all of the people who received those sentences for crimes other than homicide were children of color.

“It just said something about the way in which race was a proxy for a presumption of dangerousness, this presumption of irredeemability,” Mr. Stevenson said.

Then came a series of breakthroughs. In 2010, the Supreme Court abolished sentences of life without parole for minors charged with crimes other than murder. Two years after that, Mr. Stevenson appeared before the court on behalf of two young men who were sentenced to life without parole when they were 14. In its decision in Miller v. Alabama, the Supreme Court struck down all mandatory sentences of life without parole for juveniles. Four years later, in a case called Montgomery v. Louisiana, for which Ms. Levick served as co-counsel, the court made that decision retroactive, fulfilling the prediction Mr. Bridge made in the Graterford chapel a decade before, and giving more than 2,800 child lifers across the country the right to have their sentences revisited.

Mr. Drinks remembers the first time he got a look at Mr. Bridge’s list. It was filled with the names of people he’d known for years, but had never known were child lifers. There was Abd’Allah Lateef, the soft-spoken guy he’d always admired at Graterford, even when he griped about Mr. Drinks’s loud music. There was Luis “Suave” Gonzalez, a big talker whom Mr. Drinks had encouraged to lead one of Graterford’s Latin American cultural exchange groups. And there was Don Jones, a friend so close, Mr. Drinks said, “my brothers call him brother.”

“That was my tear-shed moment,” Mr. Drinks said. “I knew I was on the list, but going down the list and seeing genuine friends?” Now, they might all have a shot at freedom — a shot, but not a guarantee.

A block in North Philadelphia. Donnell Drinks sold drugs in the area as a teenager and was convicted of homicide at age 17 in a robbery gone wrong.

‘The election changed everything’

The Supreme Court’s rulings in Millerand Montgomery marked an important rethinking of culpability when it comes to children who commit the most serious crimes. But the practical implications of the rulings were limited: the court hadn’t abolished all life without parole sentences for children — only ones where state laws made the sentences mandatory.And while child lifers now had a chance to make a case for their release, prosecutors could still seek new life sentences. In other states with high numbers of child lifers, including Michigan and Louisiana, as well as some parts of Pennsylvania, that’s just what they did.

In Philadelphia, however, all of the list-gathering and planning that had been taking place for more than a decade began to pay off. Most of the state’s child lifers had been prosecuted in the city, and it was up to its district attorney’s office and court system to move hundreds of people through the resentencing process. “Philadelphia was bad, and everybody recognized it was bad,” Mr. Bridge said.

Ms. Levick added, “In a way, the whole world was watching.”

Philadelphia soon began resentencing and releasing child lifers, starting with those who’d been in prison the longest. But while R. Seth Williams, Philadelphia’s district attorney, initially committed not to resentence anyone to life without parole, he stuck to strict new state sentencing guidelines, which meant that Mr. Drinks and others who had been swept up in the ’90s, would most likely spend many more years in prison.

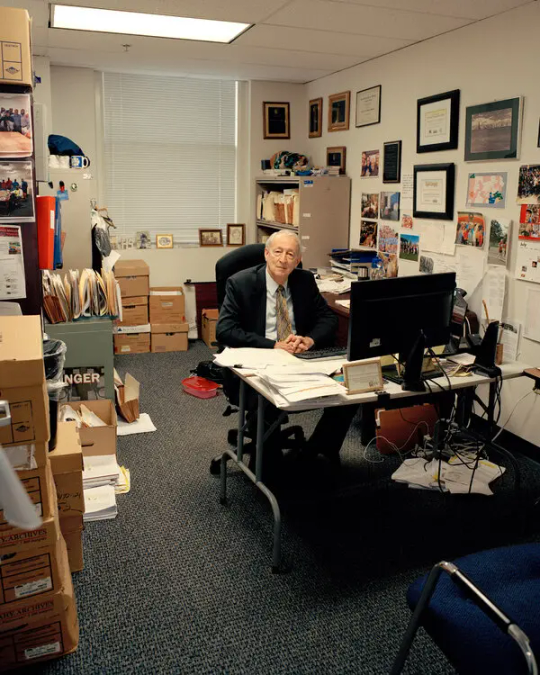

Marsha Levick, an expert on juvenile sentencing, visited inmates. “Their desire to come home was real,” Ms. Levick said. “It was palpable, and it made you want to do more.”

Mr. Williams viewed this approach as the only way to honor the Supreme Court’s ruling, the Pennsylvania government’s consensus and the rights of the victims. “People often only look at the factors for the defendant. I understand. But they often forget there was a victim,” Mr. Williams said. “Someone was murdered. We just can’t just sweep that under the rug.”

Then came a twist that no one predicted. In March 2017, a little over a year after the Montgomery decision, Mr. Williams was indicted on charges including bribery and extortion and later sentenced to five years in prison. Almost as surprising was who was elected to be his successor: a sharp-elbowed former public defender and criminal defense attorney named Larry Krasner.

Whatever Ms. Abraham, the former district attorney, had been to the city in the 1990s, Mr. Krasner swore to be the opposite. (Ms. Abraham did not respond to requests for comment.) He had run against the death penalty and mass incarceration, and vowed to decriminalize marijuana and end cash bail. One of his first moves after taking office in January 2018 was to fire 31 prosecutors in a purge that became known as the Snow Day Massacre.

When it came to juvenile lifers, Mr. Krasner was more open than his predecessor to considering how people had changed in the decades since committing their crimes. Chesley Lightsey is a former assistant district attorney who worked on Mr. Drinks’s case and others under both administrations. “It took time for me to wrap my head around it: ‘Okay, now we can have much more of a conversation about this,’” she said about the change when Krasner was elected. “It was just a different perspective.”

Under Mr. Krasner, prosecutors paid special attention to reports drafted by mitigation specialists. Those specialists, who are essentially professional storytellers for defendants, interviewed juvenile lifers, their families and anyone else who could offer context. They asked questions about how the inmates had been raised, the trauma and pain that had influenced their actions, what they had done with their time in prison and what they planned to do upon release.

By the time Mr. Krasner took office in January 2018, Mr. Drinks had spent hours spilling his soul to a lawyer and mitigator named Rachel Miller. Over the course of countless calls and several in-person visits, Ms. Miller wove the story of Mr. Drinks’s life into a memo, complete with a two-inch stack of documents highlighting his accomplishments.

The memo covers the most painful moments of Mr. Drinks’s childhood: being abandoned by his father, his mother’s struggle with addiction, getting evicted. It describes how Mr. Drinks would skip school to collect the family’s food stamps before his mother could pawn them for drugs and how, when his mother turned violent, he would take the brunt of her beatings in an attempt to spare his brothers.

But the memo also tells the story of a grown man who spent his time behind bars trying to atone for the crime that put him there. Among the stack of documents is a community college transcript filled with A’s and B’s, an agenda for a workshop he organized with victims’ rights advocates and a photo of him beaming behind a giant check made out to Big Brothers Big Sisters of America. Perhaps most meaningful to Mr. Drinks were the letters he received from other incarcerated men who were members of a youth group he founded attesting to all the ways the group, and Mr. Drinks, had saved them. “I did not know the child that committed the crime he is in here for,” read one of the letters, “but the man I do know is not that same person.”

Before Mr. Krasner’s election, Mr. Drinks was offered a deal of 35 years to life, which would have made him eligible for parole in 2026. Shortly after Mr. Krasner took over in 2018, Mr. Drinks got a new offer: time served.

“The election changed everything,” Mr. Drinks said, referring to Mr. Krasner’s victory.

“I’m always conscious of the emotion, the hurt, the disappointment, the disdain, all those negative emotions that my actions led to,” Mr. Drinks said of the murder he committed. “I’ve got to live the rest of my life counteracting that.”

Mr. Drinks’s case was not unique. Researchers at Montclair State University have found that, under Mr. Krasner, prosecutors began offering child lifers new sentences that were, on average, 11 years shorter than the ones offered to those same people under Mr. Williams. Crucially, the researchers found that child lifers’ release had a negligible effect on public safety. Seven years after they started coming home, the rearrest rate for Philadelphia’s child lifers hovers around 5 percent. That’s small compared with the national rate, where 40 percent of people with past murder convictions are rearrested within the first five years, according to the most recent data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. As of early this year, only three of the city’s child lifers who were rearrested have been convicted (for marijuana possession, contempt and robbery in the third degree), according to the Montclair State researchers.

For Mr. Krasner, these numbers reveal as a lie the idea that some people are so incapable of change that they should never be offered a shot at it. “It was always wrong to believe that people are either saints or they’re sinners,” Mr. Krasner said.

At his resentencing hearing in April 2018, Mr. Drinks read aloud from a letter before a gallery filled with friends and family, as well as the loved ones of Mr. Huntley, his victim. He apologized to Mr. Huntley’s family and said he knew he had no right to ask anyone in the room for forgiveness, and so he didn’t. But he did promise to spend the rest of his life making amends.

Mr. Huntley’s family members also made statements to the court. In a handwritten letter, Mr. Huntley’s sister described her brother as a loving and giving person. She explained how his murder had crushed her family, derailed her own education and deprived her children of ever knowing their uncle. “My mother still is deeply hurt and our family find it difficult to celebrate Valentine’s Day,” she wrote, “because these horrible, horrible actions took place that evening leading into his death.” She told the court that she did not want to see Mr. Drinks released.

Mr. Huntley’s sister did not respond to an interview request, but Suzanne Estrella, who runs the Office of Victim Advocate in Pennsylvania, said that many victims’ families “flat-out just do not” agree with the resentencings. But she said there were also many families that understood and accepted them. “You have survivors who have lost loved ones and survivors who have loved ones who are incarcerated,” Ms. Estrella said. “So you see all those perspectives coming to the table at the same time.”

As painful as it was, Mr. Drinks said he appreciated Mr. Huntley’s family’s honesty. “I felt it, and I understood it,” he said. “I’m always conscious of the emotion, the hurt, the disappointment, the disdain, all those negative emotions that my actions led to. I’ve got to live the rest of my life counteracting that.”

Three months after the hearing, having won the approval of the parole board, Mr. Drinks met his brothers as he walked out of prison for the first time in nearly three decades. Mr. Drinks remembers his sense of disbelief and being a little carsick as they drove the four hours back to Philadelphia, where he would move in with his brother Damon. The whole way home, he couldn’t shake the feeling that someone was following close behind. “I didn’t want to look back,” he said, “so I kept looking ahead.”

Donnell Drinks married Shekia Drinks two years ago. But he hasn’t been able to get the approval needed to move out of his brother’s home and in with his wife.

A return to the 1990s?

Of the more than 300 child lifers who became eligible for resentencing in Philadelphia in 2016, all but about a dozen have been resentenced, and more than 220 have been released, the majority of them on lifetime parole. That’s nearly a quarter of the roughly 1,000 total child lifers who have been released across the country. These numbers make Philadelphia, once an outlier in imprisoning minors for life, now an outlier in letting them go. By 2020, the city had resentenced more child lifers than Michigan and Louisiana combined.

What set the city apart, said Mr. Stevenson, of the Equal Justice Initiative, was not just the buy-in from local officials and public defenders, but also the community of child lifers who became their own best argument for release.

“It was the way they organized, the way they cared for one another, the way they modeled a kind of readiness to contribute to society,” Mr. Stevenson said. “These young people had been told they were going to die in prison. Some of them just never accepted that.”

Since the Supreme Court decisions, more than half of all states have outlawed life without parole sentences for children altogether, reducing the number of child lifers left in the country to fewer than 600, according to the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, a national nonprofit. Mr. Stevenson’s organization is now working to raise the minimum age at which children can be tried as adults in 11 states, including Pennsylvania, where there is no age floor. Other states are considering abolishing mandatory life without parole sentences for people under 21.

While life without the possibility of parole sentences for juveniles are now rare, they are not unheard of. The now solidly conservative Supreme Court has issued a ruling that could lower the bar for judges to apply the sentence to children in states where it is still allowed. A prosecutor in Oakland County, Mich., is seeking life without parole for a mass shooter who was 15 when he killed four students at his high school in 2021. A judge will have to weigh the horror of his crime against the possibility that, over time, he could change.

The United States is still the only country in the world that gives courts the discretion to send children to prison without the chance of proving themselves later in life at a parole hearing. And the tough-on-crime rhetoric of the 1990s is making a comeback, thanks to a spike in violent crime that began at the outset of the pandemic. In Philadelphia alone, the murder rate has surpassed the record set in 1990 two years in a row, with young people emerging as both victims and perpetrators.

Mr. Drinks and Mr. Jones started an anti-violence group in Philadelphia and sometimes walk the streets handing out pamphlets.

Just as they did in prison, child lifers have come together to create a buffer against an outside world that often feels hostile and unwelcoming.

Though this uptick in crime is showing signs of decline, it has prompted a nationwide backlash against progressive prosecutors, including Mr. Krasner, whose comparatively lenient approach has become a lightning rod in local politics. Mr. Krasner was recently the subject of an impeachment effort by Pennsylvania Republicans, and even some Democrats raced to condemn his record during the city’s mayoral primary in May.

Those who were released have become some of the loudest voices for building upon the fragile gains they fought for while on the inside. Their fight now is about abolishing life without parole for everyone, getting young people out of adult prisons and addressing the underlying causes of the violence plaguing Philadelphia and other major cities.

“If you would have dealt with a lot of my issues,” Mr. Drinks said, “they probably would not have escalated to crime.”

It’s not that Mr. Drinks and his fellow activists believe juveniles convicted of murder should not be held accountable. “When we talk to legislators, we don’t say: Throw the doors open, and everybody’s coming home,” Mr. Drinks said. “Our conversation is always that everybody deserves an opportunity to show they’re worthy of coming home.”

Today, Mr. Drinks coordinates a network of former child lifers through the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth. In any given week, he might be found with two cellphones in hand, flying to Alabama to urge progressive prosecutors to stay the course, organizing retreats for formerly incarcerated men and women, or canvassing city streets through an anti-violence nonprofit he co-founded with Mr. Jones, his friend from Graterford.

Mr. Drinks and other child lifers know that they embody for the public what all the research said about a young person’s capacity for change, and they are keenly aware that their example could help secure other people’s freedom. But they are also wary of being used to suggest that the system works, or allowing it to conceal just how difficult their re-entry into the outside world has been.

While several of Philadelphia’s child lifers have gone on to become an Ivy League lecturer or nonprofit executive, many more are working minimum-wage jobs or are unable to find work. Some are in bad health. Four have died. Nearly all of them are on lifetime parole, with the possibility of being sent back to prison forever looming.

Mr. Drinks credits his brothers, Damon and Kareem, for making his homecoming easier. Throughout Mr. Drinks’s incarceration, the three brothers had remained as close as the prison system would allow, keeping up visits even when he was transferred far away. Often, Damon Drinks would bring along Mr. Drinks’s son, who was just 3 when his father was arrested, and is now a grown man with a family of his own. It is thanks to his brothers, Mr. Drinks says, that he was able to maintain a relationship with his son at all.

Mr. Drinks, in Fairmount Park, said his brothers visited him while he was in prison and have helped him readjust to life on the outside.

Damon and Kareem Drinks’s support continued once their big brother was released. They took him shopping, kept him housed and partnered with him to start a local printing company not far from the city courthouse. Mr. Drinks has not had to struggle to survive, but that doesn’t mean he has not struggled. Five years after he left prison, the terms of his parole still prohibit him from leaving the county of Philadelphia without permission. He got married two years ago, but he has yet to get the approval needed to move out of his brother’s home and in with his wife. And he lives with the constant fear that one act of violence by any of the state’s other child lifers could spell the end of his own tenuous freedom.

This fear is part of what keeps Mr. Drinks connected to the men who were once boys with him on the inside. Just as they did in prison, child lifers have come together to create a buffer against an outside world that often feels hostile and unwelcoming. These bonds are as much a product of their shared experiences as they are a defense against their shared vulnerabilities.

“We’re each other’s co-defendants,” Mr. Drinks said. “We see people want to stray, it’s like, No, come on. We’re going to get to this finish line together.”

Mr. Drinks hugs Michael “Smokey” Wilson, another former child lifer.

#How People Sentenced to Life in Prison Made Their Case for Release#prison#american injustice system.#penal injustice#sentencing disparities#adultification#Black Lives Matter

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Overnight, Israeli forces bombed a kindergarten housing hundreds of displaced Palestinian in Al-Salam neighborhood, east of Rafah, the southern city which borders Egypt. Wafa news agency reported that two girls were killed in the Israeli airstrike and dozens injured. Another Israeli airstrike on an apartment in Hassan Salama Tower in Al-Geneina neighbourhood, east of Rafah, killed a child and wounded two others.

An Israeli airstrike on the house of the Abu Safar family killed seven Palestinians, including children, in the Al-Hakar area in Deir Al-Balah city, in central Gaza. Wafa also reported that several Israeli airstrikes and artillery shelling were launched on Khan Yunis overnight.

An airstrike on the house of Masran family in Nuseirat refugee camp in central Gaza injured several Palestinians as Israeli forces continued to bomb north Gaza neighbourhoods, killing at least eight Palestinians in an airstrike on the Al-Rimal area.

Wafa reported that in north Gaza, medical teams transferred the bodies and the injured to the Kamal Adwan Hospital, while for the sixth day in a row, Israeli forces are laying siege over the Al-Shifa Hospital, preventing people from accessing the facility. Last week, Israeli tanks approaching the Al-Shifa Hospital and Al-Rimal neighborhood, forced thousands of Palestinians to flee in panic and fear to the eastern areas of Gaza City. Despite being one of the first hospitals attacked by the Israeli military in its ground offensive campaign, Al-Shifa is one of the few remaining hospitals that are still partially operating in Gaza.

In Rafah, Israeli airstrikes on two inhabited houses killed at least 26 Palestinians, according to Wafa, and injured dozens. Rafah, the southernmost district of the Gaza Strip, has seen the influx of nearly half of Gaza’s 2 million residents, who were forcibly displaced by Israeli forces. Thousands of Palestinian families are living in tents in Rafah and lack sufficient food, fresh water and heating sources. In the past weeks, Israel has been mulling a plan to invade the Philadelphia Axis, a zone which separates the Gaza Strip from Egypt.

Palestinians are concerned that Israel will use the military operation in the area to push thousands of people out to the Sinai Peninsula under the threat of bombardment and airstrikes. Israel claims that the border area is still a breathing lung for Hamas fighters and has tunnels running underneath it.

-- From "‘Operation Al-Aqsa Flood’ Day 121" by Mustafa Abu Sneineh for Mondoweiss, 4 Feb 2024

18 notes

·

View notes