#Child and adolescent psychiatry New York

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Mental health clinic New York

Need expert psychiatric care in New York? Skypiatrist offers personalized psychiatric medication, anxiety treatment, and mental health services. Book your consultation today!

#Mental health clinic New York#Child and adolescent psychiatry New York#Child psychiatrist New York#Women's mental health New York#Women's mental health psychiatrist New York#Mental health clinic near me New York

1 note

·

View note

Text

This piece by Texas Observer Digital Editor Kit O'Connell was nominated for a GLAAD Media Award in the category of Outstanding Online Journalism Article.

With this investigation, Kit pushed back against harmful and inaccurate coverage of trans healthcare for kids, published by The New York Times. The original Times article was used in court by the state of Texas in their attempt to redefine gender-affirming healthcare as "child abuse," and this was our attempt to correct the record.

We're honored to be nominated for the 34th #GLAADMediaAwards, alongside so many other important creative works.

From the article:

“The reality is that gender-affirming medical care for trans youth is not controversial within mainstream medicine,” said Jack Turban, a medical doctor and incoming assistant professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of California San Francisco. “There is broad consensus from all major medical organizations that legislation outlawing it is dangerous.”

535 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Below are a nearly a dozen different factors that can sometimes influence a person's sense of sexual identity. Rather than saying any of these things "cause gender dysphoria," it is more accurate to say that they could contribute to a person feeling dysphoric about his or her body. Some individuals might find that some of the factors resonate deeply with them, while others might not relate to any of them. The goal isn't to provide an exhaustive list, but to encourage individuals who experience gender dysphoria to listen with compassionate curiosity to their own story.

Family dynamics

Various situations can contribute to unhealthy attachments related to gender dysphoria.(39) One is when parents hope for their baby to be a sex other than the one they receive. If this is expressed to a child, he or she may internalize the parent's disappointment regarding his or her sex. Sometimes the child is the sex that the parent had hoped for, but wasn't what they had expected. For example, as a little girl, Heather Skriba enjoyed playing with action figures and camouflage, which created tension between her and her father. He said to her, "I always wish that I had a daddy's girl as a daughter." Heather recalled:

What that communicated to my eight-year-old heart was like I'm not the daughter that my dad wants. Being around my version of femininity brings my dad pain, like it's defective, it's not good enough, and I internalized that as my identity, as my value. So that caused me to develop a lot of social anxiety, a lot of insecurity, a ton of self-hatred.(40)

Later, she realized after trying to transition that it wasn't just a hatred and discomfort about her sexual identity, it was a discomfort in who she was as a person. In her words, "It wasn't just, 'I don't like being a woman, it was like 'I don't like being me. ... At the end of the day it was like this tired, lonely, really hurt little girl who just needed love."

-Jason Evert, Male, Female, or Other: A Catholic Guide to Understanding Gender

—

Work cited:

39) Cf. Kenneth J. Zucker and Susan J. Bradley, Gender Identity Disorder and Psychosexual Problems in Children and Adolescents (New York: Guilford Press, 1995); J. Veale et al., "Biological and Psychosocial Correlates of Adult Gender Variant Identities: A Review," Personality and Individual Differences 48 (2009), 357-366; H. Meyer-Bahlburg, "Gender Identity Disorder in Boys: A Parent- and Peer-Based Treatment Protocol," Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry 7:2 (2002), 360-376; P. Cohen-Kettenis and W. Arrindell, "Perceived Parental Rearing Style, Parental Divorce and Transsexualism: A Controlled Study," Psychological Medicine 20 (1990), 613-620; M. Hogan Find lay, Development of the Cross Gender Lifestyle and Comparison of Cross Gendered Men with Heterosexual Controls (PhD diss.; Carleton University, Ottawa, Canada, 1995); R. Schott, "The Childhood and Family Dynamics of Transvestites," Archives of Sexual Behavior 24 (1995), 309-327; D. Ghering and G. Knudson, "Prevalence of Childhood Trauma in a Clinical Population of Transsexual People," International Journal of Transgenderism 8 (2005), 22-30.

40) "Transgender and the Gospel: A Conversation with Heather Skriba," https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eKuftYuby5I&ab_channel=PrestonSprinkle

—

For more recommended resources on gender dysphoria, click here.

#Mtf+#Ftm#Nonbinary#genderfluid#transgenderism#transgender ideology#Jason Evert#quotes#Male Female Other: A Catholic Guide to Understanding Gender

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Christina Buttons

Published: Apr 11, 2024

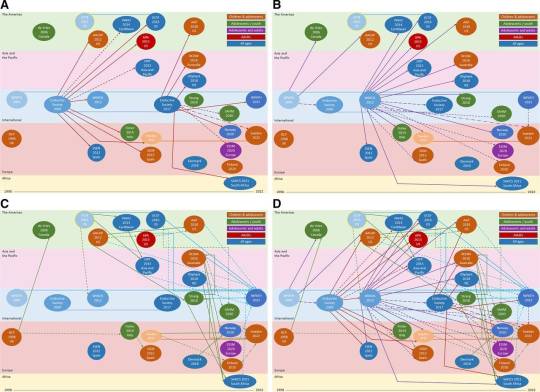

[ Figure 3 from “Clinical guidelines for children and adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria or incongruence: a systematic review of guideline quality (part 1)” ]

A new systematic review of international clinical guidelines for children and adolescents with gender dysphoria has exposed deceptive practices by respected medical authorities who recommend medical transitions for minors. These guidelines are often cited as uncontroversial and scientifically robust. However, the review reveals that these organizations have misled the public by basing their recommendations on insufficient evidence and inaccurately labeling their approach as “evidence-based.” Furthermore, they have engaged in a corrupt practice known as “circular referencing.” Instead of conducting independent evaluations, they have relied on endorsements of sex-trait modification for minors from other medical bodies, artificially creating a consensus on the issue.

Commissioned by NHS England and chaired by Dr. Hilary Cass, the University of York’s research team evaluated 23 international guidelines using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation tool to assess their quality. The study specifically examined how evidence informed recommendations, the development and agreement processes for these recommendations, the stakeholders involved, and how the guidelines referenced each other during their development.

Insufficient Evidence

The findings of the review were deeply concerning. It concluded that clinical guidelines globally used to treat gender-questioning children and adolescents were crafted in violation of international standards for guideline development. These guidelines recommended medical interventions for minors despite insufficient evidence, particularly regarding long-term treatment outcomes in adolescents. Additionally, they relied on other guidelines that recommended medical treatments as the basis for making similar recommendations.

Circular Referencing

The Endocrine Society (ES) and the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) published initial guidelines recommending youth medical transition in 2009 and 2012, respectively. These guidelines became foundational for many subsequent guidelines, shaping their content and recommendations despite the lack of evidence and rigor. In the Cass Review, Dr. Hilary Cass highlighted the ways in which WPATH and ES were closely interlinked, noting their mutual co-sponsorship and input into each other’s drafts. This coordinated effort suggests that WPATH and ES were colluding to grant undue credibility to their guidelines.

The corruption persisted in the formulation of national and regional guidelines by prominent organizations such as the American Psychological Association, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. It also extended to international guidelines from countries like Australia, Spain, Italy, and regions including Asia and the Pacific. Rather than grounding their recommendations in robust evidence, these guidelines deferred to the endorsements from the initial guidelines of WPATH and ES.

Years later, when WPATH and ES updated their guidelines, they referenced the same national and regional guidelines that had initially drawn from their recommendations. This perpetuated a cycle in which each iteration reinforced the others, each time without sufficient evidence to support the recommendations. Dr. Cass highlighted the problematic nature of this circular referencing, stating, “The circularity of this approach may explain why there has been an apparent consensus on key areas of practice despite the evidence being poor.”

Part 1 of the systematic review includes Figure 3, pictured above, which illustrates the various ways in which guidelines reference or influence each other. It shows how guidelines draw on the initial Endocrine Society (2009) and WPATH (2012) guidelines, which have influenced nearly all the national and regional guidelines identified. Additionally, it demonstrates how these subsequent guidelines cite and rely on each other, and how the latest Endocrine Society (2017) and WPATH (2022) guidelines have cited and drawn on the national and regional guidelines.

The systematic review highlights an example of this circular referencing: WPATH Version 8, published in 2022, identifies numerous national and regional guidelines published as early as 2012 as potentially valuable resources. It cites guidelines from the APA (2015), Australia (2018), New Zealand (2018), and University California, San Francisco (2016) multiple times to support their recommendations. Importantly, all of these guidelines were themselves significantly influenced by WPATH Version 7 (2012).

Broader Context

In the research world, such circular referencing is sometimes referred to as a citation cartel. This occurs when a group of academic authors collude to excessively cite each other's publications to artificially inflate their citation counts. However, what has occurred here differs slightly; their aim wasn’t to boost citation counts, but rather to enhance their own credibility through mutual referencing in the eyes of the public and other medical professionals. Nonetheless, this practice is highly unethical. By engaging in circular referencing, these medical bodies have actively deceived healthcare professionals and the public, leading them to believe in the validity and reliability of recommendations founded on weak evidence.

Unfortunately, much of the transgender rights movement has advanced through an approach that heavily relies on appeals to authority. Organizations that once focused on Gay and Civil Rights, now pivoting to champion transgender rights, are deferred to as authoritative bodies by news outlets, schools, teachers' unions, and even the Biden administration, which seeks their guidance on transgender issues. Within academia, idea laundering has bestowed Queer Theory and Gender Theory, foundational to modern gender ideology, with the illusion of legitimacy.

Moreover, significant changes in federal regulations under Title IX, granting biological males (who identify as women) access to female-only spaces and sport categories, have occurred through a process known as institutional leapfrogging. In this process, judges and administrators take incremental steps, each citing the authority of the other, ultimately leading to the expansion of federal mandates.

Not Evidence-Based

WPATH, whose stated mission is to “promote evidence-based care,” and ES, who refers to their approach as “evidence-based transgender medicine,” along with any organization advocating for medical transition for minors, are misleading the public by portraying themselves as being “evidence-based.”

In an investigative report for the British Medical Journal (BMJ), Dr. Gordon Guyatt, a highly respected figure in the field of medical research methods and evidence evaluation, and who pioneered the evidence-based medicine (EBM) movement, stated that the current guidelines in the United States for managing gender dysphoria in adolescents should not be considered evidence-based. He emphasized that these guidelines fail to offer cautious and conditional recommendations appropriate for such low-quality evidence. Guyatt further underscored his concerns in a social media post, labeling these guidelines as "untrustworthy."

Similarly, the systematic review team arrived at the same conclusion:

Most clinical guidance lacks an evidence-based approach and provides limited information about how recommendations were developed. The WPATH and Endocrine Society international guidelines, which like other guidance lack developmental rigour and transparency have, until recently, dominated the development of other guidelines. Healthcare professionals should consider the lack of quality and independence of available guidance when utilising this for practice.

In the end, the team was only able to recommend two guidelines for practice: the Finnish guideline published in 2020, and the Swedish guideline published in 2022. Both guidelines conducted their own systematic evidence reviews, concluding that the risks of medical transition outweigh any purported benefits. As a result, they do not recommend medical transition treatments for minors but instead prioritize mental health support.

WPATH, ES, and any medical authority that misrepresents guidelines recommending medical transition for minors as “evidence-based” betray public trust and fail those seeking reliable guidance. Healthcare professionals and regulatory bodies must hold guideline developers accountable for these deceptive practices and ensure transparency in the basis of future recommendations.

The National Health Service England issued a statement in response to the Cass Report and new systematic reviews, asserting that their findings "will not only shape the future of healthcare in this country for children and young people experiencing gender distress but will also be of major international importance and significance."

==

Nobody who has been following the "gender medicine" space or read the interim Cass review would be surprised with the outcome. Or the denial of the activists. Including the ones masquerading as medical professionals.

What might be the most surprising outcome of the Cass review is the level of fraud and collusion by ideologues involved in the way pseudoscience and outright fantasy ("puberty blockers are fully reversible") has been framed as some unquestionable truth ("the science is settled").

It was always fraud. This was always an ideology.

#Christina Buttons#circular referencing#circular logic#citation cartel#academic fraud#fraud#appeal to authority#medical corruption#medical malpractice#medical scandal#academic corruption#gender affirming care#gender affirming healthcare#gender affirmation#queer theory#gender identity ideology#gender ideology#intersectional feminism#religion is a mental illness

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

thank you for tagging me @monkberryfields! 💗 i know i answered Q&A type questions in a recent post, but i love answering them, and these are slightly different from my previous post, so here we go!

are you named after anyone?: the way my parents both named me after themselves UGH! their audacity..Elizabeth and Glenn must really love themselves that much, huh?

when was the last time you cried?: surprisingly, i don’t cry as often as i think. it usually happens when i get sentimental over an old memory or when i overthink about something that was said to me that i took offense to when i shouldn’t have.

do you have kids?: haha, no. i need someone who’s gonna be a good husband/father material first.

do you use sarcasm a lot?: noo, really?

what's the first thing you notice about people?: eyes and outfit usually

what's your eye color?: brown

scary movies or happy endings?: happy endings 💗

any special talents?: i’m an amateur at guitar and bass, and i can operate a motorcycle if you consider that a special talent.

where were you born?: New York! eh, i’m walkin’ here!

what are your hobbies?: working out, reading, listening to music, playing guitar/bass, video editing, photography, traveling the world

have you got any pets?: yes, two actually- a handsome tuxedo cat named Beckley and my rainbow coloured betta fish Dewey.

what sports do you play/have you played?: running, cycling and martial arts

how tall are you?: 4’11 🧍🏻♀️

favorite school subject?: in grad school currently, and since most of my classes have been psychiatry based, the one class i really enjoyed was my child/adolescent psych class- that class was a lot of fun and i kinda wanna work with kids in the field i’m going into so that class was a great learning experience.

dream job? i work as a nurse, and i feel like i’ve already kind of fulfilled my childhood dream of helping and healing the world through my nursing work, but i still want to do missionary work someday and help the sick and poor in underdeveloped countries. i always wanted to do that as a kid :)

tagging: @folklegend @burn-on-the-flame @fancycolours @jwclapton and whoever else wants to do this!

8 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Parental Trauma in a World of Gender Insanity | Miriam Grossman MD | EP 347

Dr. Jordan B. Peterson and Miriam Grossman discuss the grief and trauma associated with the Transgender movement, not just for those transitioning, but for the parents and families who now find themselves shunned and alienated if they refuse to affirm their own child's delusion. They also go into detail on the history of the ideology, the monstrosity of Dr. John Money, and his horrendous failed experiment on which he built his doctrines.

Miriam Grossman MD is a physician, author, and public speaker. Before gender ideology was on anyone’s radar, she warned parents about its dangers in her 2009 book, “You’re Teaching My Child WHAT?” Dr. Grossman has been vocal for many years about the capture of her profession by ideologues, leading to dangerous and experimental treatments on children and betrayal of parents. Dr. Grossman was featured in the Daily Wire’s hit documentary “What Is A Woman?” The author of four books, her work has been translated into eleven languages. After graduating with honors from Bryn Mawr College, Dr. Grossman attended New York University Medical School. She completed an internship in pediatrics at Beth Israel Hospital in New York City, and a residency in psychiatry through Cornell University Medical College, followed by a fellowship in child and adolescent psychiatry. Dr. Grossman is board certified in psychiatry and in the sub-specialty of child and adolescent psychiatry.

#jordan peterson#miriam grossman#psychiatry#psychiatrist#trans#transgender#gender dysphoria#transitioning#ideology#experiments#lost in transnation#family#parents#children#social contagion#demonization#dr. john money#creep#gender

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Licensed Mental Health Counselor In New York

Maria Ruiz De Toro, LMHC

Licensed Mental Health Counselor and Supervisor

Are you experiencing emotional pain? Symptoms are not the problem but the solution! By listening to ourselves and reviewing intimate issues, relational patterns and life experiences, in a structured and organized manner; we can better understand out pain and symptoms, heal and gain insight to resolve our conflicts, be more emotionally consistent and work towards supporting out real self. I welcome you to work on this process. I utilize a variety of therapeutic approaches, including insight oriented, psychodynamic and experiential therapies, and evidence-based treatment such as cognitive behavioral therapy.

Please know that one of the strengths of my work entails sorting through life events, including child history and relationships, and helping you to reframe and restructure them into healthier perceptions and positive internalized realities that promote growth.

I believe that including the person’s style and personal interests is essential during the healing process. I also incorporate art interventions and body awareness techniques into my practice. As an international psychotherapist I have lived in and traveled to different parts of the world, including Asia, Europe, and the Americas and I have worked with a culturally diverse caseload throughout my career.

Areas of Expertise:

Anxiety and Depression

Family Therapy and Couples Therapy

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Parenting Issues

Developmental Crisis

Life transitions/Moves and Changes

Acculturation and Adjustment

Child and Adolescent Psychotherapy

Education and Experience:

M.A., Brooklyn College, The City University of New York

Interpersonal Psychoanalysis, William Alanson White Institute of Psychiatry

Wellness Self-Management, Columbia University, New York State Institute

Family Therapy and Systemic Approach, Ackerman Institute

Foundations in Marriage and Family Therapy.

Alternatives for Families: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, St. John’s University

Trauma Focused CBT (Web), Medical University of South Carolina

Mental Health and Family Therapy Training, Roberto Clemente Center NY

Intake Coordinator

New York State License 006853

Click here to schedule an appointment with Maria.

#Mental health counselor#licensed mental health counselor#mental health services#mental health treatment

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comprehensive Psychiatric Services in New York

At Empower Psychiatric Services, we are dedicated to providing high-quality psychiatric services in New York. Our team of experienced psychiatrists and therapists offers a wide range of mental health care solutions to help you overcome anxiety, depression, PTSD, bipolar disorder, and other psychiatric conditions.

Our Services Include:

Diagnostic assessments to understand your unique needs

Therapy and counseling tailored to your mental health goals

Medication management for effective symptom control

Child and adolescent psychiatry for young patients

With both in-person and telehealth appointments available, we make it easy for you to access the care you need. Let us support you on your path to better mental health.

#Psychiatry#therapy#MentalHealthNY#AnxietyTreatment#TherapyNYC#anxietyhelp#health tips#mental health#psychiatricservices#anxietyrelief#depressionsupport

1 note

·

View note

Text

PROGRAMME INFO (8)

**SCROLL TO THE BOTTOM TO READ IN CHRONOLOGICAL ORDER**

Anastopoulos, A. & Shelton, T. (2001). Assessing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishing Co. Barkley, R. A. (1997) Defiant Children: A Clinician’s Manual for Assessment and Parent Training. New York: Guilford Press (800-365-7006; [email protected]). Barkley, R. A. (2006). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment (3rd edition). New York: Guilford Press, 72 Spring St., New York, NY 10012 (800-365-7006 or [email protected]). Barkley, R. A., & Murphy, K. R. (2006). Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Clinical Workbook. New York: Guilford (800-365-7006 or [email protected]). Barkley, R. A. (2005). ADHD and the nature of self-control. New York: Guilford. (see above) Barkley, R. A., Edwards, G., & Robin, A. R. (1999). Defiant Teens: A Clincian’s Manual for Assessment and Family Intervention. New York: Guilford. (see above) Brown, T. (2000). Attention deficit disorders and comorbidities in children, adolescents, and adults. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. Buell, J. (2004). Closing the Book on Homework. Amazon.com. DuCharme, J., Atkinson, L., & Poulton, L. (2000). Success based, noncoercive treatment of oppositional behavior in children from violent homes. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 9951004. Department of Human Development and Applied Psychology, University of Toronto (OISE), 252 Bloor Street West, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5S 1V6. DuPaul, G. J., et al. (1998). The ADHD-IV Rating Scale. New York: Guilford. DuPaul, G. J., & Stoner, G. (2003). ADHD in the schools. New York: Guilford. Gioia, G. A., Isquith, P. K., Guy, St. C., & Kenworthy, L. (2000). Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. (www.parinc.com; 800-331-8378). Goldstein, S. (1998). Managing atttention and learning disorders in late adolescence and adulthood. New York: Wiley. Goldstein, S., & Goldstein, M. (1998). Managing attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children. New York: Wiley. Goldstein, S. & Teeter Ellison, A. (2002). Clinician’s Guide to Adult ADHD. New York: Academic Press. Gordon, M., & McClure, D. (1997). The down and dirty guide to adult ADHD. DeWitt, NY: GSI Publications. Jensen, P. S., & Cooper, J. R. (2003). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: State of Science – Best Practices. Kingston, NJ: Civic Research Institute. Kralovec, E., & Buell, J. (2000). The End of Homework:How Homework Disrupts Families, Overburdens Children, and Limits Learning. Amazon.com. Loo, S. & Barkley, R. A. (2005). Clinical utility of EEG in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Applied Neuropsychology, 12, 64-76. Mash, E. J., & Barkley, R. A. (2003) Child Psychopathology. New York: Guilford. Mash, E. J., & Barkley, R. A. (2005). Treatment of childhood disorders (3rd edition). New York: Guilford. Milich R, Ballentine AC, & Lynam D. (2001). ADHD Combined Type and ADHD Predominantly Inattentive Type are distinct and unrelated disorders. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 8, 463-488. Pagani, L., Tremblay, R., Vitaro, F., Boulerice, B., & McDuff, P. (2001). Effects of grade retention on academic performance and behavioral development. Development and Psychopathology, 13, 297-315. L. Pagani, Ph.D., Research Unit on Children’s Psychosocial Maladjustment, University of Montreal, CP 6128, succursale Centre-ville, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H3C 3J7; email: [email protected]. Phelps, L., Brown, R. T., & Power, T. J. (2001). Pediatric psychopharmacology: Combining medical and psychosocial interventions. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. (www.apa.org/books; 800-374-2721) Robin, A. R. (1998). ADHD in adolescents: Diagnosis and treatment. New York: Guilford. ([email protected]; 800-365-7006) Rojas, N. L., & Chan, E. (2005). Old and new controversies in alternative treatments for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

0 notes

Text

Dr William Zubkoff Biography

Dr. William Zubkoff is a highly respected and well-known child psychiatrist. He has worked extensively with children and families affected by mental illness, substance abuse, and trauma. He is the author of numerous books and articles on these topics. Dr Zubkoff is a leading expert on the treatment of childhood psychiatric disorders. He has been interviewed by major media outlets such as The New York Times, NBC Nightly News, and CBS This Morning.

His early life and medical training

William Zubkoff was born in Brooklyn, New York on June 26, 1934. His father was a pharmacist and his mother was a homemaker. He attended public schools in Brooklyn and then went on to study at the City College of New York (CCNY). He graduated from CCNY with a Bachelor of Science degree in Pharmacy in 1955.

He then went on to study medicine at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center, graduating with his M.D. degree in 1959. He did his internship and residency training in Internal Medicine at the Montefiore Hospital Medical Center in the Bronx, New York.

After completing his medical training, Dr Zubkoff worked as a general practitioner in the borough of Queens in New York City. In 1967, he opened his own private practice which he continued to run until his retirement in 2012.

His career in psychiatry

Dr. William Zubkoff is a highly respected psychiatrist who has been working in the field for over 35 years. He has helped countless patients through his work and has been an advocate for mental health awareness and education.

Dr. Zubkoff began his career as a psychiatric resident at the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center. He then went on to complete a fellowship in child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. After completing his training, Dr. Zubkoff returned to the Bay Area to start his private practice.

His research on ketamine

Dr William Zubkoff's research on ketamine has led to him becoming one of the world's foremost experts on the drug. His work has helped to shed light on the potential therapeutic benefits of ketamine, as well as its risks and side effects.

Zubkoff's research has shown that ketamine can be an effective treatment for a variety of conditions, including depression, anxiety, and chronic pain. He has also conducted extensive research into the risks and side effects of ketamine use, and his work has helped to inform both clinicians and patients about the potential dangers of the drug.

His views on the future of psychiatry

In his book "The Future of Psychiatry", Dr. William Zubkoff offers a detailed and insightful look at the potential future of psychiatry. He begins by discussing the current state of the field, noting the challenges it faces and the progress that has been made in recent years. He then goes on to outline his vision for the future of psychiatry, which includes a greater focus on preventive care, the use of new technologies to improve patient care, and a more collaborative approach to care between mental health professionals and other medical specialists.

Last Words

Dr. William Zubkoff is a remarkable man who has dedicated his life to helping others. He is a skilled doctor and a talented writer, and he has used his skills to improve the lives of countless people. If you are ever in need of medical help or advice, Dr. Zubkoff is someone you can trust to give you the best possible care.

0 notes

Text

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry New York: Understanding Medication Management

Child and adolescent psychiatry plays a crucial role in addressing mental health issues that affect children and teens. In New York, many families seek psychiatric services to help manage conditions such as anxiety, depression, ADHD, and other behavioral disorders.

0 notes

Text

Associate Professor at Suicide Research Unit discusses Meghan Markle Interview

You can also listen to this interview on a free app on iTunes and Google Play Store entitled 'Raj Persaud in conversation', which includes a lot of free information on the latest research findings in psychology, psychiatry, neuroscience and mental health, plus interviews with top experts from around the world. Download it free from these links. Don't forget to check out the bonus content button on the app.

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.rajpersaud.android.rajpersaud

https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/dr-raj-persaud-in-conversation/id927466223?

Thomas Niederkrotenthaler is associate professor at the Suicide Research Unit at the Institute of Social Medicine, Center for Public Health, Medical University of Vienna. He is the co-chair of the International Association for Suicide Prevention's Media and Suicide Special Interest Group.

Reacting to suicidal revelations - is Piers Morgan right?

Research on suicide reporting suggests a surprising effect of Meghan's interview

by Dr Raj Persaud

Piers Morgan, a controversial TV host, has now left his national broadcasting position after expressing strong disbelief over Meghan’s confessions of suicidal thinking in her interview with Oprah Winfrey.

BBC News reports that Piers Morgan continues to stand by his criticism of the Duchess of Sussex. Ofcom, a regulator of broadcasting in the UK, is investigating his comments after receiving 41,000 complaints from the British public.

The duchess apparently formally complained to ITV about Morgan's remarks. It is reported that she raised concerns about how Piers Morgan's sentiments affect the issue of mental health, and what it might do to others contemplating suicide.

Is Meghan correct in her reported analysis? Or is Piers Morgan right to stand by his comments?

Or, in discussing suicide during an Oprah Winfrey interview, did she in fact make it more likely that others will self-harm?

Media reporting of suicidal behaviour has been found to contribute to an increase in suicidal thinking and actual suicides in the population. At this point Piers Morgan may argue the duchess is wrong to criticise him, and has only herself to blame, if there is a spike in suicides following the interview.

Recent research found that Google searches for “How to kill yourself” significantly increased after the release of ‘13 Reasons Why’, a popular Netflix American teen drama on the aftermath of high school student's suicide. The study calculated there were 900 000 to 1.5 million more searches than expected, for that time of year, in just over two weeks following the release of the series.

Another study, published in the Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry in February 2020, estimated there were 195 additional suicide deaths among 10- to 17-year-old youths between April 1 and December 31, 2017, following the series’ release.

One of the first studies to investigate this effect, analysed 34 newspaper stories that reported on suicides, and found a 2.51% increase in suicide during the month of the publicity.

More worrying still, about the possible repercussions of the extensive reporting of Meghan’s suicidal thinking worldwide, is that, research by Professor Steven Stack, an expert on the sociology of suicide, based at Wayne State University, USA, found that studies measuring the presence of an entertainment celebrity in a suicide press report, are over 5 times more likely to find a copycat effect, while studies focusing on female suicide, were almost 5 times more likely to report a copycat effect, than other research investigating the impact of suicide reporting in the press.

Another example reported by Steven Stack is that in the year of the publication of a book which focused on self-harm via a particular method, suicide by that specific recommended method, increased 313% in New York City. In almost one third of cases a copy of the book was found at the scene of the suicide.

On average, following the media reporting of a suicide, approximately one third of persons involved in subsequent suicidal behavior appear to have seen the reporting of that suicide and may be copycat suicides.

The suicide of actress Marilyn Monroe was associated with a 12% increase in suicide.

One theory as to why reporting of a celebrity killing themselves or feeling suicidal, according to Professor Steven Stack, is that the vulnerable suicidal person may reason, ‘If a Marilyn Monroe with all her fame and fortune cannot endure life, why should I?’

Copycat suicides following media reporting of self-harm has been termed the ‘Werther Effect’, following a notorious historical incident after the publication in 1774 of a popular novel in which the hero kills himself. Entitled, The Sorrows of Young Werther the book by Goethe was rumoured to be responsible for a subsequent epidemic of suicide in young people. European authorities were so worried about its impact, that the book was banned in Copenhagen, Italy and Leipzig.

Goethe is reported to have commented on the phenomenon; “My friends … thought that they must transform poetry into reality, imitate a novel like this in real life and, in any case, shoot themselves; and what occurred at first among a few took place later among the general public …”

However, now new research suggests that, in fact, Meghan Markle in talking about suicide, may have indeed performed a positive service in terms of suicide prevention.

The study entitled, ‘Role of media reports in completed and prevented suicide: Werther v. Papageno effects’, refers to a ‘Papageno Effect’, which the authors claim may be the opposite of the ‘Werther Effect’, and happens when suicide rates go down following a particular kind of self-harm publicity.

The ‘Papageno Effect’, the authors explain, is based on Papageno's overcoming of a suicidal crisis in Mozart's opera ‘The Magic Flute’. If media reporting has a suicide-protective impact this should now be referred to as the ‘Papageno Effect’ the authors argue. In Mozart's opera, Papageno becomes suicidal upon fearing the loss of his beloved Papagena; however, he refrains from suicide because of three boys who draw his attention to alternative coping strategies.

Thomas Niederkrotenthaler and Gernot Sonneck from the Medical University of Vienna, Austria, led a team who analysed all 497 suicide-related print media reports from the 11 largest Austrian nationwide newspapers, including the term suicide, between 1 January and 30 June 2005.

Reporting of individuals thinking about suicide (not accompanied by attempted or completed suicide) was associated with a decrease in national suicide rates. This study suggests that media items on suicidal thinking, perhaps as described by Meghan in her recent interview, formed a distinctive class of articles, which have a low probability of being potentially harmful.

The study, published in the British Journal of Psychiatry found that in marked contrast, media stories attempting to dispel popular public myths about suicide, in other words articles that you would have thought would be helpful, and were intended to be helpful as regards suicide, were associated with increases in suicide rates.

Other articles associated with increases in suicide rates include stories where the main focus was on suicide research, items containing contact information for a public support service and also the reporting of expert opinions.

In other words, all the previous so-called expert opinion of how the media ought to report suicide was not actually linked to drops in suicide rates, but instead increases.

The authors conclude that the actual reporting of suicidal thinking may contribute to preventing suicide. Therefore, it follows that whatever Piers Morgan may think or believe about the Meghan interview, the latest scientific research suggests she may have performed a public service in drawing attention to suicidal thinking.

One theory as to why this might be the case include the suggestion that reporting someone thinking about suicide enhances identification with the reported individual, and thus highlights the reported outcome as ‘going on living’.

This research suggests a new public health strategy as regards suicide prevention. This may be most effective when articles are published on individuals who refrained from adopting suicidal plans, and instead adopted positive coping mechanisms, despite suffering adverse circumstances.

The authors refer to this kind of press story as ‘Mastery of Crisis’. One example they quote: ‘Before [Tom Jones] had his first hit, he thought about suicide… and wanted to jump in front of an Underground train in London… In 1965, before he made the charts with “It's not unusual”, he thought for a second: “If I just take a step to the right, then it'll all be over”.’

Whatever else you may think of her, or the interview, the key question becomes, did Meghan exhibit ‘Mastery Of Crisis’?

REFERENCES

Piers Morgan stands by Meghan criticism after Good Morning Britain exit https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-56343768

Internet Searches for Suicide Following the Release of 13 Reasons Why. Ayers JW, Althouse BM, Leas EC, Dredze M, Allem J. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1527–1529. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3333

Association between the release of Netflix's 13 Reasons Why and suicide rates in the United States: an interrupted times series analysis. Bridge, J, Greenhouse, JB, Ruch, D, Stevens, J, Ackerman, J, Sheftall, A, et al. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2019; 28 Apr (doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.04.020).

Suicide in the Media: A Quantitative Review of Studies Based on Nonfictional Stories. Steven Stack. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 35(2) April 2005, 121-133

Role of media reports in completed and prevented suicide: Werther v. Papageno effects. Thomas Niederkrotenthaler, Martin Voracek, Arno Herberth, Benedikt Till, Markus Strauss, Elmar Etzersdorfer, Brigitte Eisenwort and Gernot Sonneck. British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(3), 234-243. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074633

Check out this episode!

1 note

·

View note

Text

Week 1 - Assignment

Suicide Rates in Adolescents in the United States and its association with their Race, Parental relationship and Family background, Race and Personality.

Sri Lanka, my home country unfortunately has one of the highest suicide rates per capita. With suicide rate being 15 per 100000 mid-year population with trends gradually reducing over the years. (suicide-rate @ www.macrotrends.net, n.d.). That being the case, I became interested in exploring the associated factors of suicide specially in the adolescent population, so I chose the Add health dataset for analysis.

I wish to see if suicide in the adolescent population is associated with their racial and religious background, personality, family background and parental relationships.

I created my own codebook by extracting specific variables which I found to describe the associated factors mentioned above. Accordingly I selected, and will be using the following variables under the specific associations I intend to study.

Suicide

H1SU1, H1SU2, H1SU3, H1SU4, H1SU5, H1SU6, H1SU7, H1SU8

Race

H1GI4, H1GI5A, H1GI5B, H1GI5C, H1GI5D, H1GI5E, H1GI5F, H1GI6A, H1GI6B, H1GI6C, H1GI6D, H1GI6E, H1GI7A, H1GI7B, H1GI7C, H1GI7D,H1GI7E, H1GI7F, H1GI7G, H1GI8, H1GI11

Personality

H1PF7, H1PF10, H1PF13, H1PF14, H1PF15, H1PF16, H1PF18, H1PF19,H1PF20, H1PF21, H1PF26, H1PF30, H1PF31, H1PF32, H1PF33, H1PF34,H1PF35, H1PF36

Parental Relations and Family Background

H1PF1, H1PF2, H1PF3, H1PF4, H1PF5, H1PF23, H1PF24, H1PF25, H1WP8, H1WP9, H1WP10, H1WP11, H1WP12, H1WP13, H1WP14, H1WP15, H1WP16, H1WP17A, H1WP17B, H1WP17C, H1WP17D, H1WP17E, H1WP17F, H1WP17G, H1WP17H, H1WP17I, H1WP17J, H1WP17K, H1WP18A, H1WP18B, H1WP18C, H1WP18D, H1WP18E, H1WP18F, H1WP18G, H1WP18H, H1WP18I, H1WP18J, H1WP18K

I then conducted a literature review on suicide trends in adolescents and their associated factors.

An article on Suicide and Suicidal attempts among Adolescent and Young Adults states that suicide affects all races and socioeconomical statuses. It further points out several causes for suicide and suicidal attempts among adolescents, them being “current situational problems and stresses such as conflicts with parents, breakup of a relationship, school difficulties or failure, substance abuse, social isolation and physical ailments” (“American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Adolescence: Suicide and suicide attempts in adolescents and young adults.,” 1988)

Another review article on suicide and youth which focuses on their risk factors point out that the adolescent age itself is prone to have a higher tendency to get more mental illnesses, specially in the age between 13-20 years. (Bilsen, 2018)

Durkheim’s book Suicide (1897) emphasized the concept of social integration, which was conceptualized as the opposite of anomic, isolated, and egoistic. He hypothesized that suicide

rates would vary negatively with the level of social integration of the individuals’ groups and presented data to show that married individuals had proportionately lower suicide rates than unmarried individuals of the same age. He also highlighted the roles of religious integration and

varying family circumstances to an understanding of suicide. (Durkheim, 1951)

Another longitudinal study done targeting 659 families in New York it was found that eight types of interpersonal difficulties ( difficulty in making friends, frequent arguments with adult authority figures, cruelty towards peers, frequent refusal to share, frequent arguments or anger with peers, social isolation, lack of close friends and poor relations with friends and family. (Johnson et al., 2002)

Another study accessing 1508 adolescents over a one year time period showed that there was an increased tendency for attempted suicide even after adjusting for depression. (Lewinsohn et al., 1994)

Furthermore another epidemiological study pointed out that their was a significant increase in the tendency of suicidal ideation in adolescents aged 9-17 years where these adolescents had “a poor family environment (low satisfaction with support, communication, leisure time), low parental monitoring, and poor instrumental and social competence.”(King et al., 1998)

A study focusing on Religion as a risk factor for suicide in patients with existing depression showed that there was an increase in suicide and suicidal attempts in participants who reported religion was more important and who had attended religious services more frequently. (Lawrence et al., 2016)

“Based on the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) in the USA, Kleiman & Liu have shown that those who frequently attended religious services (i.e. >24 times per year) were less than half as likely to die by suicide than those who attended services less frequently.” (Cook, 2014) which turns ut to be contradictory to the findings of the above study.

Another review article pointed out that whether religion acted as a protective factor or risk factor foe suicidal tendency differed according to the gender of the participant (Females more religious being more protected against suicide than the male counterpart) and also the race of the participant , however several contradicting results were found in the review article. (Edward & Dana, 2018)

After going through relevant literature and the Add Health database, I came up with the following hypothesis.

1. There is a positive correlation with Poor Parental Relations and poor Family Background with suicide , Suicidal attempts and Suicidal Ideation.

2. There is a negative correlation with Stronger Religious background and suicide , Suicidal attempts and Suicidal Ideation.

3. Race of the participant correlates with their Suicide rate , Suicidal attempts and Suicidal Ideation.

4. There is a Negative correlation with Stronger personality traits (Problem solving, Decision making) and Suicide , Suicidal attempts and Suicidal Ideation.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Adolescence: Suicide and suicide attempts in adolescents and young adults. (1988). Pediatrics, 81(2), 322–324.

Bilsen, J. (2018). Suicide and Youth: Risk Factors. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9(October), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00540

Cook, C. C. H. (2014). Suicide and religion {. 254–255. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.113.136069

Durkheim, É., 1951. Suicide. Glencoe, Ill.: Free Press.

Edward, R., & Dana, G. (2018). Religion and Suicide : New Findings. Journal of Religion and Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-0629-8

Johnson, J. G., Cohen, P., Gould, M. S., Kasen, S., Brown, J., & Brook, J. S. (2002). Childhood Adversities, Interpersonal Difficulties, and Risk for Suicide Attempts During Late Adolescence and Early Adulthood. 59.

King, R. A., Schwab-stone, M., Flisher, A. J., & Ed, M. M. (1998). Psychosocial and Risk Behavior Correlates of Youth Suicide Attempts and Suicidal Ideation. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(7), 837–846. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200107000-00019

Lawrence, R. E., Brent, D., Mann, J. J., & Burke, A. K. (2016). Religion as a Risk Factor for Suicide Attempt and Suicide Ideation Among Depressed Patients. 00(00), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000484

Lewinsohn, P. M., Rohde, P., & Seeley, J. R. (1994). Psychosocial Risk Factors for Future Adolescent Suicide Attempts. 62(2), 297–305.

suicide-rate @ www.macrotrends.net. (n.d.). https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/LKA/sri-lanka/suicide-rate

1 note

·

View note

Text

What It Took for a Fox News Psychiatrist to Finally Lose His License https://nyti.ms/2MbUGZu

What It Took for a Fox News Psychiatrist to Finally Lose His License

Keith Ablow was a popular fixture on the cable channel until 2017, and a high-profile therapist. He left a trail of vulnerable female patients who claim he abused them.

By Ginia Bellafante | Published Dec. 20, 2019 | New York Times | Posted December 21, 2019 |

Late in 2009, a 28-year-old woman not long out of graduate school found herself in a stressful job at a Bronx hospital and decided it would be useful to talk to someone. Searching online, she came across the name of a psychiatrist, Keith Ablow.

Dr. Ablow was familiar to her from his writing, both his journalism and the best-selling thrillers he turned out — “Denial,’’ “Projection,” “Compulsion,’’ “Murder Suicide.’’ She had read all of those, as well as “Psychopath,’’ a book about a psychiatrist who prods the interior lives of strangers only to kill them, baroquely obscuring the distinction between patient and victim.

The woman — who has asked to be identified only by her confirmation name, Monique — found Dr. Ablow just as his media star was rising. That year, Roger Ailes had hired him as a regular contributor on Fox News, where he would remain until 2017, speculating about the mental states of political figures and presiding over viewer segments like “Normal or Nuts?”

Dr. Ablow offered counseling in the conventional sense, but he also conducted life-coaching via email. Monique engaged with him this way at first, but after she answered various questions about her past, mentioning adolescent bouts of depression, she agreed to see Dr. Ablow in person. His busy schedule meant that she would have to go to his primary office, in Newburyport, Mass. He was impressive to her, and so Monique made the five-hour trip for her first visit.

Over the next year and a half, Monique saw Dr. Ablow two or three times a week, at the reduced rate of $350 an hour. During this time she found herself coming unwound.

Her anxiety about work did not recede. On the contrary, she felt increasingly addled and insecure, and problems that had been latent for a long time resurfaced. She began cutting herself, something she hadn’t done in years.

Monique came to believe that Dr. Ablow had not only failed to help her; he left her more damaged than she already was. For his part, Dr. Ablow would maintain that whatever boundaries she thought he violated — the frequent texts and emails, the intimate revelations about his own life — were in the service of her treatment, well within the standard of sound psychiatric care.

As Monique would discover, it would take years — and several other patients coming forward with their own stories of manipulation — for Dr. Ablow’s transgressions to be taken seriously.

The case represents a core challenge of psychological treatment. At a cultural moment in which all kinds of relationships are policed for abuses of power imbalance, psychotherapy takes place in seclusion: two people, alone in a room, with one holding extraordinary influence over the other, just as it has been since Freud. It remains a world with murky oversight, and if you are harmed, it is not obvious what can be done.

By the time Monique left his care, her new marriage had fallen apart and she had developed a dependency on Valium, Xanax and Adderall. She also said she had drained her savings of $30,000 to pay for the treatment.

Most alarming, she had become obsessively, insidiously reliant on Dr. Ablow’s affirmation, a circumstance she and her lawyer would later suspect he engineered.

On an unusually hot late-summer morning, in a coffee shop just north of the city, Monique recounted how she had come under Dr. Ablow’s thrall. When she finally disentangled, she filed a complaint with the disciplinary board in New York that oversees psychiatrists — a body that works secretly and can take years to respond to charges. In this case, when it finally completed its initial review of Dr. Ablow, it found no reason to sanction him.

As we spoke over several hours, Monique’s caution gave way to a fluid and emotional narrative. It was easy to imagine her on the other side of conversations that played out this way hundreds of times. She was, in fact, a therapist herself.

That she had this training compounded the embarrassment anyone in her situation would surely feel. Monique was reflexively skeptical about human motivation. As a child she had resisted authority. How had she landed here?

From the beginning, Dr. Ablow presented himself as an idealized caretaker more than a guide. “As if he said, ‘Let down your guard, let go of everything and completely fall on me, because I will give you everything you ever needed. And you need nothing but to trust me,’” she reflected.

This was intoxicating to Monique. Her childhood had been marked by her father’s volatility, her mother’s emotional absence, a difficult relationship with her brother. With Dr. Ablow, she found herself in the strange state of feeling both further weakened by her past and protected from it.

If therapy is the project of overcoming, Monique belatedly came to believe that Dr. Ablow urged her neither toward strength nor self-reliance. “He did make me feel beautiful and precious and special,’’ she said. “But very broken.’’

On May 15, Dr. Ablow’s license was suspended in Massachusetts after an investigation determined that his continued practice was a threat to the “health, safety and welfare” of the public. He is appealing the ruling.

This article is based on interviews with Monique and others, including her current therapist as well as legal and medical documents obtained by The Times. Dr. Ablow did not respond to attempts to speak with him directly, but his lawyer, Paul Cirel, issued a statement on his behalf, writing in an email that his client would not “breach the ethical/confidentiality standards of his profession” and comment further.

Earlier this year, Dr. Ablow referred to the claims Monique made in her legal complaint to the health department in New York as “groundless.” He has categorically denied all allegations of sexual misconduct against him that have come up in subsequent cases. And he has said, as he did with Monique, that to whatever extent he revealed personal information with patients, he did so in the effort to help them work through issues of psychological importance.

On Feb. 5 next year, a hearing will take place in Massachusetts that will ultimately determine the future status of Dr. Ablow’s medical license.

From the outset, Monique had inklings of doubt about Dr. Ablow, but she easily suppressed them. Her first meeting with him ended with a prescription for an antidepressant. Although she found it curious that he would administer drugs so quickly, she deferred to his approach.

The boundary between patient and doctor was permeable from the start. Dr. Ablow took Monique to a taping at Fox; he connected her with a literary agent when she wanted to write. On one occasion, she mentioned she was near his office with her dog. This was in Newburyport, where she still went for treatment on occasion, running up bills in local inns, in addition to seeing him in New York. She knew Dr. Ablow had expressed an interest in meeting her dog, and he briefly left a session with another patient to come outside and play with him, she said.

Their sessions had an improvisational, transgressive tone. According to her official complaint, Dr. Ablow twice wondered, for no apparent therapeutic purpose, whether Monique had genital piercings. At one point, when she was describing a conflict with her father, Dr. Ablow responded: “Why don’t you tell your father to come stick a gun in my face and see what happens.”

Money was an ongoing problem for Monique, and she eventually questioned why so much of her costly time in therapy was spent listening to Dr. Ablow talk about issues he confronted in his own life — that his sister was drawn to broken men, that his son did a lot of pacing.

These confidences nonetheless made Monique feel as though she held outsize status with Dr. Ablow. Which made it all the more painful for Monique when she felt dismissed by him — when he would arrive late for their sessions, she said, or text and email during them.

Any of these incidents might have given her pause, but it took what she regarded as an explicit act of cruelty to compel her to leave. Early on, Monique had told Dr. Ablow that she feared, above all, being physically trapped — imprisoned, taken somewhere and locked up.

Many months later, during a disagreement about something relatively minor, she said, Dr. Ablow suggested that he might have to hospitalize her. Hospitalizing a distraught psychiatric patient is not an unreasonable course in certain circumstances, but Monique was certain he was preying on her vulnerabilities.

“I couldn’t trust him after that,” Monique said.

When Keith Ablow was in medical school at Johns Hopkins University in the 1980s, after graduating from Brown, he hoped to become an ophthalmologist. It was a mentor at Hopkins who suggested psychiatry, recognizing someone profoundly curious about other people’s lives.

His ambition was evident early on. He wrote the first of his 16 books, “Medical School: Getting In, Staying In, Staying Human,’’ while he was still a student. A paperback edition featured a blurb from The New England Journal of Medicine.

In the mid-1990s, Dr. Ablow was interviewed for a book, “In Session: The Bond Between Women and Their Therapists.’’ The author, Deborah Lott, had met him at a gathering of clinicians and found him to be insightful on the subject of boundaries and transference. Ms. Lott thought of him “as one of the good guys,’’ she said recently, “an advocate for women.”

Before his emergence at Fox, Dr. Ablow was a familiar presence on daytime talk shows, where he delivered advice with a brash compassion. Ms. Lott had lost track of him until his television appearances. As a Fox commentator, she said, his persona was radically different from the one she remembered. (A spokeswoman for Fox confirmed that Dr. Ablow’s contract was not renewed in 2017 and had no further comment.)

On TV, Dr. Ablow’s habit of diagnosing political leaders, particularly President Obama, who he believed suffered from abandonment issues that made him a weak leader, sparked criticism from a profession that maintains a fierce distaste for this sort of conjecture.

In 2014, Jeffrey Lieberman, chair of the psychiatry department at Columbia University, publicly denounced Dr. Ablow, who in turn responded with a clever press statement: “I am apparently joined by my nemesis Dr. Jeffrey Lieberman in rejecting the position that psychiatrists ought not comment on public figures. Lieberman condemned me as a ‘narcissistic self-promoter’ — yet he has never interviewed me.”

In November of that same year, Ms. Lott received a circumspect email from a young woman who had read her book and had questions about Dr. Ablow’s involvement. It was Monique. She was wondering what Dr. Ablow was doing in a book about boundaries. “She had no ax to grind,” Ms. Lott recalled, “other than trying to make sense out of what had happened.’’

Two years earlier, in 2012, Monique had outlined all of her allegations against Dr. Ablow in a lengthy complaint she made with New York State’s Office of Professional Medical Conduct, the agency empowered to suspend and revoke psychiatric licenses.

In these documents, she claimed that Dr. Ablow had crossed multiple boundaries, overwhelming her with details about himself — that he had been attracted to his children’s babysitters, for instance, and that his marriage was unfulfilling.

He asked her to coffee frequently. He encouraged her to move in with a female friend of his in Manhattan when Monique separated from her husband, only to later tell her that the roommate he recommended was “nuts.” He mentioned to Monique that he wanted to send a former all-star running back for the New York Giants to her as a patient. He also suggested that she date him.

At one point, while she was still seeing Dr. Ablow for regular therapy, he offered her a job with his life-coaching business. She took it, counseling people remotely. For a few months, she was both his patient and his employee.

In the course of her efforts to establish her own practice, Dr. Ablow encouraged Monique to move to Newburyport, which would be cheaper than New York.

She almost went through with it.

Monique had recently married a man after a four-year engagement, yet her ambivalence about him persisted. Dr. Ablow knew all about this. In fact, when she emailed him on the eve of her wedding, he gave her confounding advice. In his reply, he implicitly encouraged her to go through with it, at the same time remarking that marriage itself was “absurd.”

On the day she planned to move and leave her husband behind, in January 2011, a tremendous storm hit the Northeast. She decided to stay in New York, where she continued to see Dr. Ablow for another six months.

Once she made the decision to leave Dr. Ablow, Monique met with a Manhattan lawyer, Audrey Bedolis, who has concentrated in psychotherapeutic malpractice since the early 1990s.

Ms. Bedolis knew that cases without accusations of sexual misconduct, clear physical abuse or some other singular, dramatic incident are typically hard to litigate; she and her client eventually abandoned plans for a lawsuit. But Ms. Bedolis believed that the sheer volume of Dr. Ablow’s boundary trespasses would surely result in disciplinary action from state authorities.

In the dynamic between Monique and Dr. Ablow, Ms. Bedolis saw something all too familiar. Though she knew only Monique’s side of the story, it seemed to her a clear case of exploitation that, while it did not involve sex, was just as devastating. “First he medicated her when she never thought she should be medicated,’’ Ms. Bedolis said. “Then he lured her in as the only person who could help her.”

For several years, Monique waited to hear something from the conduct office in New York. In October 2017, the office finally wrote to say that it had found “insufficient evidence’’ to bring any charges of misconduct against Dr. Ablow.

One week after the New York board wrote to Monique saying that it would not sanction him, it sent a separate letter to Dr. Ablow, stating that in her case, he had failed to render proper care and treatment and that he prescribed medications inappropriately. He was told to refrain from boundary violations.

But there was no punishment for this; his license to practice psychiatry in New York remained in good standing.

This spring, however, based on Monique’s claims and the testimonies of four other female patients, as well as several former employees of Dr. Ablow’s, the Massachusetts Board of Registration in Medicine ruled that Dr. Ablow practiced “in violation of law, regulations, and/or good and accepted medical practice.” As a result of that suspension, he consented to cease practice in New York, where a renewed investigation by the conduct office is underway.

Three of the women — like Monique, all young — told an investigator for the Massachusetts board that Dr. Ablow had become sexually involved with them during the course of their treatment. One of them said that he introduced her to sadomasochism and hit her with a belt during their encounters, exclaiming, “I own you.”

In a formal written response to the board, Dr. Ablow denied this, as well as the charges that he had been physically intimate with the other patients involved in the case.

In a statement issued in August, Dr. Ablow’s lawyer, Mr. Cirel, addressed the charges in a series of malpractice lawsuits brought against Dr. Ablow, which were settled out of court this year, as well as the allegations in the complaint to the state, writing: “We are pleased that the civil matters have been amicably resolved. Dr. Ablow can now focus his attention and resources on overturning the Board of Medicine’s order of temporary suspension, so that he can restore his medical license and resume helping patients into the future, as he has countless times in the past.”

Last winter, before the suits were settled, Dr. Ablow appeared on a Boston-area news show, where he addressed them and claimed to be a target of cancel culture. “A male, a public person and a Trump supporter,” Dr. Ablow said in the interview. “So am I surprised? Yeah. But shocked? No.”

In his rebuttal to the Massachusetts board, Dr. Ablow said that one of his accusers had a history of falsely accusing men of sexual misbehavior and that she had essentially confused what happened between them with the actions of a recurring character in his novels.

The documents filed in conjunction with Dr. Ablow’s suspension reveal something else as well — that in three separate instances in which his medical license came up for renewal in Massachusetts, between 2013 and 2017, he failed to notify the state that he was under investigation in New York. During the renewal process, an applicant is asked specifically if he or she is under investigation in a different state. Dr. Ablow said that he wasn’t.

After her time with Dr. Ablow, Monique was apprehensive about trusting a new therapist. Eventually she returned to the psychoanalyst she saw during her first year of graduate school, Robert Katz. Recently, she gave permission to Dr. Katz to speak about her experience with Dr. Ablow.

Monique entered treatment with him shaken by what had happened to her under Dr. Ablow’s care, he said. Dr. Katz viewed the boundary violations she described as a means of grooming her for a sexual relationship.

Of everything she brought up, Dr. Katz added, one detail stuck out most in his mind: that Dr. Ablow had suggested to Monique that she become an escort to earn the extra money she needed. (Dr. Ablow has denied ever saying this, and denied it again when another patient made the same claim.)

In recent years Monique has settled into a successful private practice (this is why she insisted on anonymity in exchange for participating in this article).

Still, even now, after all she has come to understand, she finds herself occasionally missing the connection she had with Dr. Ablow, longing again to experience how much she imagined she meant to him.

When a psychiatrist, psychologist or social worker is barred from practicing, it does not necessarily mean that they are prevented from dispensing advice, in an office, for profit. Life-coaching is a career open to almost anyone; requiring no credentials, it is largely unregulated.

After the suspension of his license, Dr. Ablow repositioned himself. The Ablow Center for Mind and Soul in Newburyport identifies Dr. Ablow on its website as someone who “practiced psychiatry for over 25 years before developing his own life-coaching, mentoring and spiritual counseling system.” Over the summer, he took courses in pastoral counseling at Liberty University, the evangelical Christian college in Lynchburg, Va.

The Ablow Center is expanding its services, including free therapy for veterans once a month. It also announced an essay contest for high-school and college students considering a career in counseling.

Beyond that, visitors to the center’s website can find regular blog posts from Dr. Ablow, like a recent entry with the headline, “Why a Depression and Anxiety Consultant Could Be the Key to Recovering.”

For anyone “still’’ feeling anxious or low, Dr. Ablow had some wisdom: “It may have nothing to do with you,” he wrote, “and everything to do with the treatments being offered to you.”

______

Ginia Bellafante has served as a reporter, critic and, since 2011, as the Big City columnist. She began her career at The Times as a fashion critic, and has also been a television critic. She previously worked at Time magazine. @GiniaNYT

#fox news#mental health#mental ill health#mental heath support#u.s. news#public health#health#health & fitness#health news#nyt > top stories#top news

1 note

·

View note

Link

Abstract

This chapter addresses certain features of Native American healing practices that have relevance to the treatment of traumatic stress syndromes and other mental states of distress. The major focus will be on American Indian healing practices used for survivors. To those unfamiliar with the ways of American Indian shamans, these practices may seem strange and initially somewhat foreign or even threatening. However, for those willing to learn and be open to experience, there is psychic encounter in ritual that some would term metaphysical or perhaps supernatural. To Native Americans, they are both religious and sacred.

References

Attneave, C. L. (1974). Medicine men and psychiatrists in the Indian health service. Psychiatric Annals, 4(22), 49–55.Google Scholar

Barter, E. R., & Barter, J. T. (1974). Urban Indians and mental health problems. Psychiatric Annals, 4(11), 37–43.Google Scholar

Bergman, R. L. (1971). Navajo peyote use: its apparent safety. American Journal of Psychiatry, 128, 695–699.PubMedGoogle Scholar

Bergman, R. L. (1973). A school for medicine men. American Journal of Psychiatry, 130, 663–666.PubMedGoogle Scholar

Bergman, R. L. (1974). The peyote religion and healing. In R. H. Cox (Ed.), Religion and psychotherapy (pp. 296–306). Springfield, II: Charles C Thomas.Google Scholar

Brown, J. E. (1971). The sacred pipe. Baltimore: Penguin Books.Google Scholar

DeMallie, R. J. (Ed.). (1984). The sixth grandfather: Black Elk’s teaching given to John G. Neihardt. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.Google Scholar

Dillon, R. H. (1983). North American Indian wars. New York: Facts on File.Google Scholar

Dizmang, L. H., Watson, J., May, P. A. & Bopp, J. (1974). Adolescent suicide at an Indian reservation. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 44, 43–49.PubMedCrossRefGoogle Scholar

Erikson, E. (1968). Identity, youth and crisis. New York: W. W. Norton.Google Scholar

Fuchs, M., & Bashshur, R. (1975). Use of traditional Indian medicine among urban Native Americans. Medical Care, 13, 915–927.PubMedCrossRefGoogle Scholar

Hagan, W. T. (1979). American Indians (Rev. ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Google Scholar

Harner, M. (1980). The way of the shaman. New York: Harper & Row.Google Scholar

Holm, T. (1982). Indian veterans of the Vietnam War: Restoring harmony tribal ceremony. Four Winds, Autumn, 3, 34–37.Google Scholar

Holm, T. (1984). Intergenerational reapproachment among American Indians: A study of thirty-five Indian veterans of the Vietnam War. Journal of Political and Military Sociology, 12, 161–170.Google Scholar

Holm, T. (1986). Culture, ceremonialism and stress: American Indian veterans and the Vietnam War. Armed Forces and Society, 12, 237–251.PubMedCrossRefGoogle Scholar

Hultkrantz, A. (1979). The religions of the American Indians (Monica Setterwall, Trans.). Berkeley: University of California Press.Google Scholar

Isaacs, H. L. (1978). Toward improved health care for Native Americans: Comparative perspective on American Indian medicine concepts. New York Journal of Medicine, 78, 824–829.Google Scholar

Janoff-Bulman, R. (1985). The aftermath of victimization: Rebuilding shattered assumptions. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Trauma and its wake: The study and treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (pp. 15–36). New York: Brunner/Mazel.Google Scholar

Jilek, W. G. (1971). From crazy witch doctor to auxiliary psychotherapist—the changing image of the medicine man. Psychiatric Clinic, 4, 200–220.Google Scholar

Jilek, W. G. (1974). Indian healing power: Indigenous therapeutic practices in the Pacific Northwest. Psychiatric Annals, 4(11), 13–21.Google Scholar

Leighton, A. H. (1968). The mental health of the American Indian—Introduction. American Journal of Psychiatry, 125, 217–218.PubMedGoogle Scholar

Locke, R. F. (1976). The book of the Navajo. Los Angeles: Mankind.Google Scholar

Mails, T. E. (1978). Sundancing at Rosebud and Pine Ridge. Sioux Falls: Center for Western Studies.Google Scholar

Mails, T. E. (1985). Plains Indians: Dog soldiers, bear men, and buffalo women. New York: Bonanza.Google Scholar

Mansfield, S. (1982). The gestalts of war. New York: Dial Press.Google Scholar

May, P. A., & Dizmang, L. H. (1974). Suicide and the American Indian. Psychiatric Annals, 4(11), 22–28.Google Scholar

McNickle, D. (1968). The sociocultural setting of Indian life. American Journal of Psychiatry, 125, 219–223.PubMedGoogle Scholar

Meyer, G. G. (1974). On helping the casualties of rapid change. Psychiatric Annals, 4(11), 44–48.Google Scholar

Red Fox, W. (1971). The memoirs of Red Fox. New York: McGraw-Hill.Google Scholar

Shore, H. H. (1974). Psychiatric epidemiology among American Indians. Psychiatric Annals, 4(11), 56–66.Google Scholar

Silver, S. M. (1985a). Lessons from child of water. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. CG 018 606.).Google Scholar

Silver, S. M. (1985b). Post-traumatic stress disorder in veterans. In P. A. Keller & L. G. Ritt (Eds.), Innovations in clinical practice sourcebook (Vol. 4, pp. 23-34). Sarasota Professional Resource Exchange.Google Scholar

Silver, S. M. (1985c). Post-traumatic stress and the death imprint: The search for a new mythos. In W. E. Kelly (Ed.), Post-traumatic stress disorder and the war veteran patient (pp. 43–53). New York: Brunner/Mazel.Google Scholar

Silver, S. M., & Kelly, W. E. (1985). Hypnotherapy of post-traumatic stress disorder in combat veterans from WW II and Vietnam. In W. E. Kelly (Ed.), Post-traumatic stress disorder and the war veteran patient (pp. 211–233). New York: Brunner/Mazel.Google Scholar

Stands In Timber, J., & Liberty, M. (1967). Cheyenne memories. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.Google Scholar

Terrell, J. U. (1972). Apache chronicle. New York: World.Google Scholar

Underhill, R. M. (1965). Red man’s religion: Beliefs and practices of Indians north of Mexico. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.Google Scholar

Wallace, A. F. C. (1966). Religion. New York: Random House.Google Scholar

Weibel-Orlando, J., Weisner, T. & Long, J. (1984). Urban and rural drinking patterns: Implications for intervention policy development. Substance and Alcohol Actions/Misuse, 5, 45–57.PubMedGoogle Scholar

Westermeyer, J. (1974). “The drunken Indian:” Myths and realities. Psychiatric Annals, 4(11), 29–36.Google Scholar

Wilson, J. P. (1980). Conflict, stress and growth. In C. R. Figley & S. Leventman (Eds.), Strangers at home: Vietnam veterans since the war (pp. 123–166). New York: Praeger Press.Google Scholar

Wilson, J. P., & Zigelbaum, S. D. (1986). Post-traumatic stress disorder and the disposition to criminal behavior. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Trauma and its wake: Theory, research and intervention (pp. 305–321). New York: Brunner/Mazel.Google Scholar

Wilson, J. P., Walker, A. J., & Webster, B. (in press). Reconnecting: Stress recovery in the wilderness. In J. P. Wilson (Ed.), Trauma, transformation, and healing. New York: Brunner/Mazel.Google Scholar

Worcester, D. E. (1979). The Apaches. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.Google Scholar

#native american#Resources#energy medicine#shamanism#Therianthropic Shaman#healing energy#meditation#trauma#books#quantum consciousness#spirituality#integrative medicine

1 note

·

View note

Quote