#Chawan no Naka

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

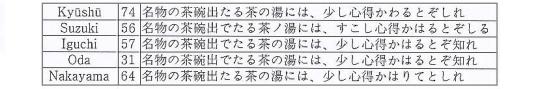

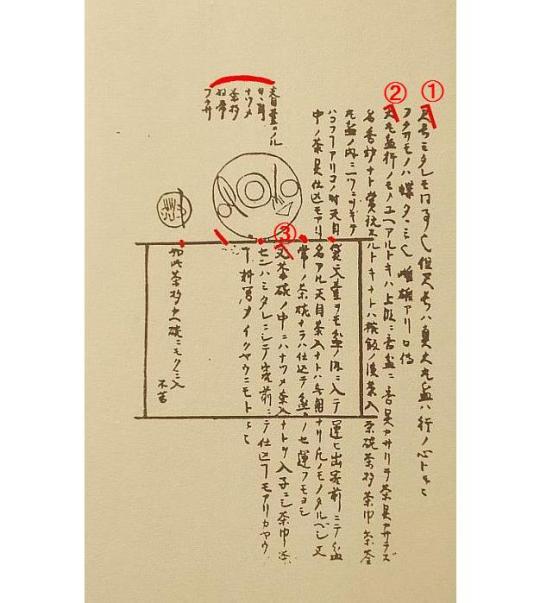

The Chanoyu Hyaku-shu [茶湯百首], Part III: Poem 74.

〽 Meibutsu no chawan idetaru chanoyu ni ha sukoshi kokoro-e kawaru to zo shire

[名物の茶碗出たる茶の湯には 少し心得變わるとぞ知れ].

“When a meibutsu chawan is brought out, the way [you] do things should be modified ever so slightly [so as to emphasize the concern¹ that should be exhibited for this kind of chawan] -- [this idea must] be grasped!”

Jōō is saying not that the meibutsu chawan should be handled differently (that is, by employing a different sort of temae --which is the way many modern practitioners understand this poem), but that an emphasis should be placed on deepening his concern for the handling of the chawan within the framework of the ordinary temae². The host must be very careful to do everything correctly³, and the guests should also be very careful when it is their turn to handle this precious chawan⁴.

On account of its importance in reminding the beginner to be especially careful when a meibutsu-chawan is brought out, it should not really surprise us that this poem has retained the same wording in all of the collections.

_________________________

¹Sukoshi kokoro-e kawaru to zo [少し心得變わるとぞ] literally means that one should modify one’s mindset, one’s way of thinking, by a little.

In practice, this means that the host should be more “solicitous” of the meibutsu chawan -- constantly keeping himself aware of what he is doing, how he is handling the chawan (even though the actual mechanics should be essentially the same as what he was taught when learning how to handle any chawan during the temae). For example, holding the other hand in readiness nearby when handling the bowl with one hand, using two hands rather than one where possible, and keeping the meibutsu chawan closer to the mat when moving it from one place to another. And, of course, carefully wiping it with the chakin as Rikyū taught should always be done*, rather than draping the chakin over the side and rotating the bowl -- the potentially dangerous method that crept into the modern temae from Imai Sōkyū via his machi-shū followers. ___________ *The only exception -- and in practice, for Rikyū, this was an extremely rare occurrence -- would have been when the chawan (usually a temmoku) was displayed at the beginning of the temae tied in its shifuku.

If the host wishes to show the shifuku to his guests (such as when it had been provided by a famous chajin of earlier times), then the best way to do this would be to display the chawan, tied in its shifuku, during the shoza -- either on the floor of the tokonoma (resting on a tray), or somewhere else in the tea room (such as on the chigai-dana, in a venue where one was available). Then, during the naka-dachi, the shifuku would be removed, the chawan rinsed and dried, and displayed on the utensil mat with the chakin and chasen arranged in it.

²It is also best, on such an occasion, to use a mentsū [面桶]* as the mizu-koboshi [水飜し]†, rather than one made of metal or pottery -- since accidentally bumping the wooden koboshi with the chawan will be far less likely to cause it damage than if the koboshi were made of some harder material. ___________ *Today this kind of koboshi is usually called a magemono-kensui [曲げ物建水].

The word mentsū [面桶] means a face[washing] bucket, referring to its original use in the bath. Historically speaking, mentsū originally came in two sizes (both of which Jōō used as his koboshi, depending on the number of guests he would be serving). The smaller size (the kind usually seen today, which measures 5-sun 5-bu in diameter) was made to be used for dipping hot water out of the bath with which to rinse one’s body; while the larger one (measuring 7-sun in diameter; and which is sometimes sold today as a magemono chakin-darai [曲げ物茶巾盥]) was actually the one used when washing the face.

Because these were inexpensive, and easily-obtained objects (even in the most remote mountain hamlets), Jōō’s rule was that they should be used only once, and then discarded (or at least not used again for chanoyu -- though they could probably be used in the bath afterward, so long as they were cleaned out after serving tea). Indeed, this complete cleanliness that was insured by their never having been used before was their special feature, meaning that the mentsū could be used on any occasion, and in any setting (including with the daisu), with absolute impunity.

†The name mizu-koboshi [水飜し] comes from mizu [水], water, and kobosu [飜], which means to spill or pour (water) into something (koboshi, then, is the nominal form, meaning the vessel into which water is poured).

Historically speaking, the kanji-compound “建水,“ a sinicized construction (meaning it appeared at the end of the seventeenth or beginning of the eighteenth century, around the time when the Chá-jīng [茶經] and the sencha-dō [煎茶道], the sencha drinking ceremony, were imported via Korea), was also intended to be pronounced either mizu-koboshi or simply koboshi. “Kensui,” using the on-yomi [音讀み] or “Chinese-style” pronunciation, appeared in the 20th century when people without any classical training in chanoyu were being elevated into exalted positions within the tea hierarchy.

³Again, this is not a matter of doing things differently*, but that the host should focus his attention on the chawan, and handle it strictly in accordance with the rules, rather than taking the more casual approach that is natural when using a chawan that can be replaced easily†. ___________ *Particularly in the case of Rikyū’s chanoyu, the whole premise was that there should be just one, basic temae; and that same temae should be employed on all occasions, with only the most minor modifications necessary in order to accommodate the different kinds of utensils that would be used. It is with this thought in mind that we should reread, and reflect upon, his well-known dictum:

chanoyu ha daisu konbon nari, daisu wo ryakushite furo no chanoyu, furo wo ryakushite irori ni narashi, shin no daisu wo shirazu ha gyō no furo mo narigatashi nari, gyō no furo wo mo wakimaesu-shite ha, sō no irori mo naru-bekarazu to shirubeshi, ne-moto ni hana no zakitaru-gotoku nari ha arubeshi

[茶湯ハ臺���根本也, 臺子ヲ略シテ風爐ノ茶湯, 風爐を略シテ圍爐裏ニナラシ, 眞ノ臺子ヲ不知ハ行ノ風爐モ成難シ也, 行ノ風爐ヲモ分キマヘスシテハ, 草ノ圍爐裏モ成可カラズト知ルベシ, 根本ニ花ノ咲タル如ク成ハ有ルベシ].

“The daisu is the root of chanoyu. When the daisu is abbreviated, we have chanoyu with the furo; and when the furo is abbreviated, it becomes chanoyu with the irori. Without first understanding the ‘shin’ of the daisu, the ‘gyō’ of the furo will be confused; and if the ‘gyō’ of the furo is but imperfectly understood, then the ‘sō’ of the irori will also be unattainable, so you must understand. It is like a flower, which blooms upward from its root.”

This “abbreviation” means simplification -- in the sense of taking away everything that is not necessary -- while keeping the essential elements intact. This is what Rikyū’s temae were.

†By the time Rikyū’s period of greatest influence arrived, chawan were already being produced locally. And if such a piece came to be damaged as a result of inattention to the details of its handling -- though perhaps worthy of blame -- it could, nevertheless, be replaced easily and cheaply. It was the recognition of this possibility (especially in the mind of the beginner) that underpinned the host’s more casual attitude toward his utensils that perhaps was the reason Jōō express this preemptive criticism in words.

⁴The usual way is for them to come forward and drink their tea where the host placed the chawan, rather than taking it back to their seat before drinking. (Sometime -- particularly in Jōō’s and Rikyū’s period -- only the shōkyaku would be served using the meibutsu-chawan, while a different bowl would be used to serve tea to the other guests*.)

And when inspecting the special chawan†, the guests should come forward as a group and look at the chawan where the host placed it, with only one of the guests‡ actually touching it. In this case, that person should handle it in such a way that the others could also see the important features of this bowl so there would be no need for them to want to hold it. ___________ *Nevertheless, though the “different bowl” is technically a kae-chawan [替え茶碗] (a substitute bowl), it should be wiped with the chakin in the same way as any other bowl used to serve tea. Draping the chakin over the rim and rotating the bowl should only be done only during those daisu-temae where the purpose of the kae-chawan was to provide a place for the host to clean the chasen, so he would not have to put the dirty chasen into the omo-chawan.

The chakin is draped over the side and used in that way so as to expose a clean surface to the bowl (since it will likely have been stained by traces of koicha left on the sides of the kae-chawan during the chasen-tōshi), a surface that will be refolded inside at the conclusion of this action.

†While some argue that this is an ideal situation when koicha should be served as sui-cha [吸い茶], doing so will naturally make the meibutsu-chawan more dirty (since the larger volume of tea will fill it more than if a single portion had been prepared; while turning the chawan so that each guest can drink from a “clean” section of the rim, as the preference seems to be nowadays, will also spread tea over more of the bowl’s inner surface and rim). And the passing of the bowl from person to person (even if the first guest puts it down on the mat for the next person to pick up, rather than the more dangerous method of passing it from hand to hand) is inherently more dangerous as well.

Also, while the usual thing is to inspect the chawan immediately after drinking, on an occasion when a meibutsu bowl is being used, the host might decide to take it back immediately, clean it (after drinking the cha-no-ato [茶の跡], as usual), and then place it out again, so it can be inspected more thoroughly.

‡While it might seem that this should be the shōkyaku, that is not necessarily the case. It should really be the person with the most experience of chanoyu who actually handles the meibutsu-chawan -- and if that person is not the shōkyaku, then he should take pains to handle it in such a way that the shōkyaku can fully inspect the bowl without having to touch it at this point.

==============================================

◎ If these translations are valuable to you, please consider donating to support this work. Donations from the readers are the only source of income for the translator.

To contribute, please use the following link:

https://PayPal.Me/chanoyutowa

1 note

·

View note

Text

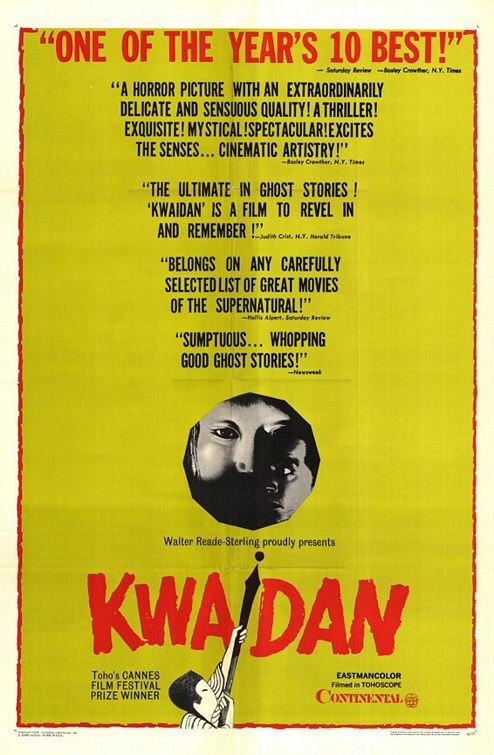

March 13, 2021: Kwaidan: In A Cup of Tea (1965)

This is it! Story 4 of 4, and it’s been a great ride so far!

This is genuinely a great movie, so I can’t wait for the final bit here! OK, I’ve somehow found a way to tie a Pokemon to all of these so far, like a goddamn nerd, so...I mean, I guess this one’s obvious, right?

Sinistea and Polteageist are genuinely one of my favorite new Pokémon. Hey, say what you like about Pokémon Sword and Shield (and, yeah, you definitely can), but most of the new Pokémon were pretty goddamn solid.

But, OK, let’s see, what’re Sinistea and Polteageist based on? According to Bulbapedia, they’re based on...ghosts and tea. Um...I mean...OK? Well, that went nowhere, I guess. So, uh, let’s see what happens with this short! Let’s get into it!

This is the last of four tales presented in the film Kwaidan, all of which are linked here:

The Black Hair (黒髪, Kurokami)

The Woman of the Snow (雪女, Yukionna)

Hoichi the Earless (耳無し芳一の話, Miminashi Hōichi no Hanashi)

In A Cup of Tea (茶碗の中, Chawan no Naka)

One more time! SPOILERS AHEAD!!!

Recap (4/4): In A Cup of Tea

Briefly, we jump forward to the year 1900, 32 years post-Meiji Restoration, around the time that the original stories were collected and written. The collector, author, and narrator of all of these stories (Osamu Takizawa) is awaiting a visit from his publisher. He notes that these stories were incomplete in many instances, and the author questions why that is. However, he decides to present an example in the form of the last story, which takes place on New Year’s Day, 220 years in the past.

Lord Nakagawa Sadano is making a round of visits with his entourage. One of his attendants, Kannai (Nakamura Kan'emon), takes a cup of tea. In the cup, he sees the face of a man, where none is behind or above him. He empties the cup, and grabs another one. When you have to hydrate, you have to hydrate. And the face in the cup agrees. Kannai empties the cup again, and smashes it this time. He grabs another cup and fills it with tea, but NOPE. THERE HE IS AGAIN! But again...when a guy’s gotta hydrate...

So, yeah, Kannai drinks the tea with the face in it, which I’m sure can only lead to good things. He goes inside the temple, and is directed to assume night watch duties, guarding Sadano. He mutters some prayers to himself, and then spies a cup. Still shaken by the previous incident, he knocks over the cup.

Ah. Well, fuck. The guy’s name is Heinai Shibuku (Noboru Nakaya), and he questions why Kannai doesn’t recognize him. Eventually, he realizes that they’re one and the same, but he doesn’t admit it. Instead, the attendant asks how Shibuku got into the estate, which he doesn’t say. Instead, he claims that the attendant caused him great harm that morning, which I assume was by drinking him. Fair enough, really.

Kannai tries to attack him, but each attack phases through the mysterious stranger, as if he were a ghost or something. Weird, right? Kannai agrees, and he rouses all of the other guards to help find him. However, they all basically call him crazy and take off, leaving him alone.

The next night, Kannai’s alone in his chambers, and a young woman comes to visit him. He stares at the cup she’s brought suspiciously (understandably), when he’s also interrupted by news that he has three visitors. He goes to greet them, and they tell him the news that Shibuku was hurt by his sword slashes, and has gone to heal himself. Kannai apologizes for this, but isn’t happy to hear that Shibuku will return on the 16th of EVERY MONTH to avenge himself.

Kannai slashes at the visitors, but they appear to be like Shibuku, and disappear at his every hit and slash, only to reappear elsewhere. Kannai, clearly a little stressed out at this point, continues his assault. And there’s a BRILLIANTLY shot scene, where you see their shadows, and not the samurai themselves. Holy shit, that looks cool.

But then, Kannai appears to get the upper hand, and appears to kill the trio. However, of course, they come back. And Kannai...Kannai’s not doing great at this point. Mentally, I mean. He starts laughing like a maniac, clearly not OK. And then...

That’s it. The story ends. We come back to the modern day, where a woman is trying to find the author, who’s suddenly gone missing after writing all day. His publisher (Nakamura Ganjirō II) comes to visit, and the two search for him. The publisher stumbles upon the story he was writing, which finishes with the idea that, since there’s no ending...why don’t you come up with the best one. How would end a story about a man who swallows another man’s soul?

Maybe...like this.

Holy shit, that’s the author! Now THAT is how you end a fuckin’ ghost story! That was Kwaidan! AND HOT DAMN, that was a good movie! Seriously, I have goosebumps. Review should be interesting. See you there!

#kwaidan#怪談#masaki kobayashi#In a Cup of Tea#茶碗の中#Chawan no Naka#Haruko Sugimura#Osamu Takizawa#Nakamura Kan'emon#Nakamura Ganjirō II#Noboru Nakaya#Seiji Miyaguchi#Kei Satō#fantasy march#user365#365 movie challenge#365 movies 365 days#365 Days 365 Movies#365 movies a year#mygifs#my gifs

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

KWAIDAN (1964) – Episode 118 – Decades of Horror: The Classic Era

"You promised that night you'd never tell anybody. You finally broke the promise. It was a pledge for life for both of us. I told you if you broke it, I would kill you. You betrayed me!" Isn’t that always the way it goes? Join this episode’s Grue-Crew - Whitney Collazo, Chad Hunt, Daphne Monary-Ernsdorff, and Jeff Mohr - as they are mesmerized by the legendary Kwaidan (1968)!

Decades of Horror: The Classic Era Episode 118 – Kwaidan (1964)

Join the Crew on the Gruesome Magazine YouTube channel! Subscribe today! And click the alert to get notified of new content! https://youtube.com/gruesomemagazine

ANNOUNCEMENT Decades of Horror The Classic Era is partnering with PlayNow Media's THE CLASSIC SCI-FI MOVIE CHANNEL, THE CLASSIC HORROR MOVIE CHANNEL, and WICKED HORROR TV CHANNEL, which all now include video episodes of The Classic Era! Available on Roku, AppleTV, Amazon FireTV, AndroidTV, Online Website. Across All OTT platforms, as well as mobile, tablet, and desktop. https://classicscifichannel.com/

This film contains four distinct, separate stories: 1) "Black Hair": A poor samurai who divorces his true love to marry for money, but finds the marriage disastrous and returns to his old wife, only to discover something eerie about her; 2) "The Woman in the Snow": Stranded in a snowstorm, a woodcutter meets an icy spirit in the form of a woman who spares his life on the condition that he never tells anyone about her. A decade later he forgets his promise; 3) "Hoichi the Earless": Hoichi is a blind musician, living in a monastery who sings so well that a ghostly imperial court commands him to perform the epic ballad of their death battle for them. But the ghosts are draining away his life, and the monks set out to protect him by writing a holy mantra over his body to make him invisible to the ghosts. But they've forgotten something; 4) "In a Cup of Tea": a writer tells the story of a man who keeps seeing a mysterious face reflected in his cup of tea.

IMDb

Director: Masaki Kobayashi

Writer: Yôko Mizuki (screenplay); Lafcadio Hearn (stories, as Yakumo Koizumi)

Music: Tôru Takemitsu

Cinematography: Yoshio Miyajima

Film Editing: Hisashi Sagara

Art Direction: Shigemasa Toda

Set Decoration: Dai Arakawa

Costume Design: Masahiro Katô

Musician: Kinji Tsuruta (biwa)

Cast

"Kurokami" ("Black Hair")

Michiyo Aratama as First wife

Misako Watanabe as Second Wife

Rentarō Mikuni as Husband

Kenjiro Ishiyama as Father

Ranko Akagi as Mother

"Yuki-Onna" ("The Woman of the Snow," "Snow-Woman")

Tatsuya Nakadai as Minokichi

Keiko Kishi as the Yuki-Onna

Yūko Mochizuki as Minokichi's mother

Kin Sugai as Village woman

Noriko Sengoku as Village woman

"Miminashi Hōichi no Hanashi," ("Hoichi the Earless")

Katsuo Nakamura as Hoichi

Tetsurō Tanba as Warrior

Takashi Shimura as Head priest

Yoichi Hayashi as Minamoto no Yoshitsune

Kazuo Kitamura as Taira no Tomomori

Yōsuke Kondō as Benkei

"Chawan no naka" ("In a Cup of Tea")

Haruko Sugimura as Madame

Osamu Takizawa as Author / Narrator

Ganjirō Nakamura as Publisher

Noboru Nakaya as Shikibu Heinai

Seiji Miyaguchi as Old man

Kei Satō as Ghost samurai

Kwaidan is Daphne’s pick and she loves every single second of the 183-minute runtime. In fact, she watched it three times! The beauty of the film, the amazing storytelling, and both the sound and set design blew her away. Chad agrees that it is a beautiful film with wonderful sets and music and appreciates how the four segments are based on supernatural folk tales. For the record, his favorite of the four is “The Woman of the Snow.” As a big lover of world folklore and ghost stories, Whitney is also on the Kwaidan bandwagon, granting it everything anyone could want in finely detailed sets, makeup, and folklore. The middle two stories, “The Woman of the Snow” and “Hoichi the Earless,” grabbed her the most. Jeff is gobsmacked by Kwaiden, calling it a stunningly beautiful film. He loved all the stories but “Hoichi the Earless” is his favorite with its historical prologue.

If you haven’t seen Kwaidan, the Classic Era Grue-Crew strongly recommends it. Yes, three hours is a long slog, but the individual stories are completely separate, so you can digest it a piece at a time. So if you haven’t seen it, do it know. If you have seen it, watch it again! Don’t make them break their feet off in your ass! At the time of this writing, Kwaidan is available to stream on The Criterion Channel and HBOmax, and on physical media as a Blu-ray disc from Criterion.

Gruesome Magazine’s Decades of Horror: The Classic Era records a new episode every two weeks. Up next on their very flexible schedule is one chosen by Whitney: Dos Monjes (1934, Two Monks) directed by Juan Bustillo Oro. Dos Monjes is available to stream on YouTube and on physical media in “Martin Scorsese's World Cinema Project No. 3” (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]. And the world folklore just keeps on coming!!

Please let them know how they’re doing! They want to hear from you – the coolest, grooviest fans: leave them a message or leave a comment on the site or email the Decades of Horror: The Classic Era podcast hosts at [email protected]

To each of you from each of us, “Thank you so much for listening!”

Check out this episode!

0 notes

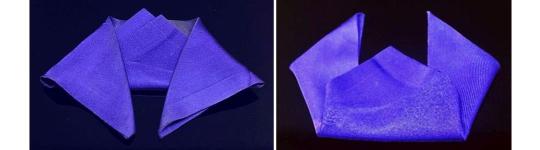

Photo

お茶碗をお貸ししたソムリエ茶人の上田さん(@hiroyaueda )が、日頃よりお使いいただいているとのこと。使いやすいといいんですが(^_^;) 連絡を頂いた方に限りお茶碗をお貸ししてます‼DMにてお知らせください(о´∀`о) #amazing #art #beautiful #japan #culture #ceramic #ceramics #pottery #和 #stoneware #matcha #chawan #chanoyu #sadou #zen #禅 #ソムリエ #日本文化 #アート #陶芸 #陶器 #茶碗 #茶の湯 #抹茶 #茶道 #中目黒 #空 #裏千家 #craft #teaceremony (Naka-Meguro Station)

#chanoyu#茶碗#ceramic#日本文化#中目黒#amazing#japan#art#stoneware#chawan#禅#culture#matcha#teaceremony#ソムリエ#茶道#craft#和#陶器#空#アート#ceramics#zen#pottery#陶芸#sadou#裏千家#茶の湯#抹茶#beautiful

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

As year by year, we are getting more conscious about food ,culture and heritage.Every cuisine get affected by its history ,evolution and religion.Japanese cuisine ,a cuisine stringed by its culture ,social and economics changes happened in past.Japanese cuisine is heavily dependent on seafood products and having largest market of whale meat.

Japan cuisine (washoku) depends on rice with miso soup and different dishes; there is an accentuation on occasional fixings. Side dishes regularly comprise of fish, salted vegetables, and vegetables cooked in juices. Aside from rice, staples incorporate noodles, for example, soba and udon. Japan likewise has many stewed dishes, for example, angle items in stock called oden, or hamburger in sukiyaki and nikujaga. Fish is normal, regularly flame broiled, yet additionally served crude as sashimi or in sushi. Fish and vegetables are additionally rotisserie in a light player, as tempura. Dishes propelled by remote nourishment—specifically Chinese dishes like ramen, seared dumplings, and gyōza—and in addition dishes like spaghetti, curry, and ground sirloin sandwiches have turned out to be embraced with variations for Japanese tastes and fixings.

The culinary items are grains, vegetables or ocean growth, poultry, and red meat .Japanese food is set up with small cooking oil expecting some of southern style dishes. Japanese sustenance is normally prepared with a blend of dashi, soy sauce, purpose and mirin, vinegar, sugar, and salt, ginger and takanotsume red pepper.A unobtrusive number of herbs and flavors might be utilized amid cooking as an indication or complement, or as a methods for killing fishy or tough scents present.some different fixings aresprig of mitsuba or a bit of yuzu skin, a touch of wasabi and ground daikon, Minced shiso leaves and myoga filled in as yakomi, kelp as folded nori or chips of aonori.

Rice is served in its own little bowl (chawan), and each course thing is put without anyone else little plate (sara) or bowl (hachi) for every individual portion.The little rice bowl or chawan (lit. “tea bowl”) serves as a word for the substantial tea bowls in tea ceremonies.Japanese feast would be expedited serving napkins called zen.Before eating, most eating places give either a hot or frosty towel or a plastic-wrapped wet napkin (o-shibori).The rice or the soup is gobbled by grabbing the bowl with the left hand and utilizing chopsticks (hashi) with the right, or the other way around in the event that one is left-handed.The appropriate use of chopsticks (hashi) is the most imperative table manners in Japan.It is traditional to eat rice to the last grain.

Meal of Japanese cuisine

yakimono(grilled and pan-fried dishes ),

nimono (stewed/simmered/cooked/boiled dishes ),

itamemono (stir-fried dishes ),

mushimono (steamed dishes),

agemono(deep-fried dishes ),

sashimi(sliced raw fish ),

suimono and shirumono (soups),

tsukemono(pickled/salted vegetables),

aemono(dishes dressed with various kinds of sauce),

su-no-mono(vinegared dishes),

chinmi (delicacies, food of delicate flavor )

Kaseki

Kaiseki is a type of art form that balances the taste, texture, appearance, and colors of food.It comprised a bowl of miso soup, include an appetizer, sashimi, a simmered dish, a grilled dish, and a steamed course with additional dishes:

Sakizuke : an appetizer similar to the French amuse-bouche

Hassun : one kind of sushi and several smaller side dishes.

Mukōzuke : a sliced dish of seasonal sashimi.

Takiawase : vegetables served with meat, fish or tofu; simmered separately.

Futamono : a “lidded dish”; typically a soup.

Yakimono : (1) flame-grilled food (esp. fish); (2) earthenware, pottery, china.

Su-zakana : a small dish used to clean the palate, such as vegetables in vinegar.

Hiyashi-bachi : served only in summer; chilled, lightly cooked vegetables.

Naka-choko : another palate-cleanser; may be a light, acidic soup.

Shiizakana : a substantial dish, such as a hot pot.

Gohan : a rice dish made with seasonal ingredients.

Kō no mono : seasonal pickled vegetables.

Tome-wan : a miso-based or vegetable soup served with rice.

Mizumono :a seasonal dessert; may be fruit, confection, ice cream, or cake.

Rice and noodles

Gohan and Meshi are the name used for cooked rice.Rice is short-grained and becomes sticky when cooked. Hakumai is very popular among them.Unpolished brown rice is getting popularity in japan.

Sweets

Wagashi is Japanese traditional sweet made up of red bean paste and mochi.Green tea flavored ice cream is also popular among them. Kakigōri and dorayaki is a ice based dessert flavored with syrup or condensed milk.

Beverages

SANTA ROSA, CA – FEBRUARY 07: A Russian River Brewing Company customer takes a sip of the newly released Pliny the Younger triple IPA beer on February 7, 2014 in Santa Rosa, California. Hundreds of people lined up hours before the opening of Russian River Brewing Co. to taste the 10th annual release of the wildly popular Pliny the Younger triple IPA beer that will only be available on tap from February 7th through February 20th. Craft beer aficionados rank Pliny the Younger as one of the top beers in the world. The craft beer sector of the beverage industry has grown from being a niche market into a fast growing 12 billion dollar business, as global breweries continue to purchase smaller regional craft breweries such this week’s purchase of New York’s Blue Point Brewing by AB Inbev. (Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

Green tea may be served to most Japanese dishes.Japan are pale-colored light lagers, with an alcohol strength of around 5.0% ABV. Sake is a brewed rice beverage that typically contains 15%–17% alcohol and is made by multiple fermentation of rice. Shōchū is a distilled spirit that is typically made from barley, sweet potato, buckwheat, or rice.Total market share of wine on alcoholic beverages is about 3%.

Japanese cuisine and health

Dishes consist of grains and vegetables, with moderate amounts of animal products and soy but minimal dairy and fruit – had a reduced risk of dying early and from heart disease or stroke.Japan have lowest rates of obesity.It have highest number of centenarian of the world possess lowest rate of age related disease.This also includes phytoestrogens, or plant-based oestrogens, that may help protect against hormone-dependent cancers, such as breast cancer.They have a traditional saying, “hara hachi bu”, which means to eat until you are 80% full, and they start teaching it to their children from a young age.

“Eat to live don’t live to eat”

“Hara Hachi Bu”

Japanese cuisine: A traditional and culture cuisine As year by year, we are getting more conscious about food ,culture and heritage.Every cuisine get affected by its history ,evolution and religion.Japanese cuisine ,a cuisine stringed by its culture ,social and economics changes happened in past.Japanese cuisine is heavily dependent on seafood products and having largest market of whale meat.

0 notes

Photo

June 30, 2017

Kwaidan (1965)

“Taking its title from an archaic Japanese word meaning ‘ghost story,’ this anthology adapts four folk tales. A penniless samurai marries for money with tragic results. A man stranded in a blizzard is saved by Yuki the Snow Maiden, but his rescue comes at a cost. Blind musician Hoichi is forced to perform for an audience of ghosts. An author relates the story of a samurai who sees another warrior’s reflection in his teacup.”

Genre: Horror

Where: Shudder

Comments: The cinematography in this film is breathtaking. I loved all the stories the same but for different reasons. 'Kurokami’ was a great tale of revenge. 'Yukionna’ was sad and visually stunning while 'Miminashi Hōichi no Hanashi’ was wonderfully bizarre and funny. Ears. 'Chawan no Naka’ was downright terrifying. I love anthologies that incorporate themes and, although vastly different from one other, these four stories evoke different emotions that compliment the previous work and together they make this film feel complete.

Rating: 5/5

0 notes

Text

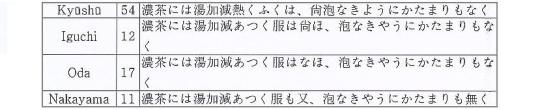

The Chanoyu Hyaku-shu [茶湯百首], Part III: Poem 54.

〽 Koicha ni ha yu kagen atsuku fuku ha nao awa naki-yō ni katamari mo naku

[濃茶には湯加減熱く服は尙 泡無き樣にカタマリも無く].

“With respect to koicha, the water should be hot, and the portion free of foam; and also there should be no katamari.”

Yu kagen atsuku [湯加減熱く]: kagen [加減] means the state or condition (of the hot water). Fuku ha nao awa naki-yō [服は尙泡無き樣]: fuku [服] refers to a dose or portion (of medicine)¹, so fuku ha nao [服は尙] means “furthermore, the portion (should be)...;” awa naki-yō [泡無き樣] means free of foam.

Koicha does not develop a frothy head of foam the way usucha does, so the scattering of small bubbles (which appear distinctly white against the dark green of the tea) might visually suggest some sort of impurity or contamination².

Katamari [カタマリ = 固まり] means a lump. After transferring the matcha into the chawan, the host takes the chashaku and smooths out the tea. At this time, the host was also supposed to break up any apparent lumps, since they can easily turn into katamari when hot water is added³.

This poem is not represented in every collection of the Chanoyu hyaku shu⁴; but in those where it is found, the wording is always the same.

_________________________

¹This traditional usage may derive from the fact that tea was originally considered a medicine.

While the modern schools hold that this is because only one bowl of koicha is prepared, to then be shared by all of the guests, this practice (called sui-cha [吸い茶]) was not really employed by Jōō or Rikyū*, both of whom served koicha in individual portions (or, in the case of Rikyū, did so for the shōkyaku, while asking the other guests share a bowl with their neighbor, in order to save time). ___________ *According to Rikyū’s own writings -- and in contrast to the arguments put forward by the modern schools (who ascribe the origin of the practice to Shukō) -- the practice of sui-cha began in Uji, during the annual auction of the year’s new tea leaves (at the end of the harvest, after the leaves had been processed). Since each bowl of koicha can be subtly different from the next, even when all other conditions are equal, it was decided that a single bowl of koicha would be prepared, and quickly shared by all the bidders, so they would all have a clear and equal understanding of the characteristics of that particular tea (since this would inform the amount of money that they were willing to bid for the lot -- usually the leaves were purchased by tea merchants, who would take them back and blend them with others to produce that firm’s characteristic flavors, after which they were sealed in jars and stored carefully until the beginning of winter).

Certain of his contemporaries began to adopt the custom, employing it during their own chakai, but Rikyū felt it was inappropriate. He held that the shōkyaku should always be served individually (since the gathering was effectively given for him -- so he should be allowed to enjoy his koicha without being forced to worry about leaving sufficient tea for the others), while the others might share bowls in groups of two (it being not too difficult to drink half).

In the wabi setting, he held that sui-cha would only be appropriate on the occasion of the kuchi-kiri no chakai [口切茶會], when the jar of new tea was cut open for the first time, since time would not permit the host to grind a sufficient quantity of matcha so that it could be served as usual. On such occasions, since the jar was cut open at the beginning of the shoza, only the tea that could be ground by the time of the naka-dachi would be available, so Rikyū prepared it as a single bowl of rather thin koicha, which all of the guests would share.

²Traditionally this is explained as looking as if poison* had been mixed with the matcha (with the poison failing to dissolve completely during the blending process); but the more likely explanation is that it would look like dust had fallen onto the koicha (such as from the host’s sleeve, as he withdrew the chasen) as the blending process was concluding. ___________ *Which is argued to have been the preferred way of eliminating the opposition by followers of the despised and feared Ikkō-shū. The problem with this line of argument is that both Jōō and Rikyū (and virtually all of their contemporaries, Japanese as well as the Korean’s of Sakai and Hakata) were followers of the Ikkō-ichi-nen Shū [一向一念宗], apparently having trained as a de facto novice for a certain period of time in their youth. Thus it is not likely that Jōō or Rikyū would have facilitated the dissemination of what could have been taken to be anti-Ikkō-shū propaganda.

³A katamari begins as a lump in the matcha (often because the tea remained too long in the chaire that it began to be affected by atmospheric moisture). What happens is that the outside of the lump absorbs water, while the interior remains relatively dry. Rather than breaking down when the tea is blended with the chasen, the katamari remains intact, becoming quite gummy in the process.

Katamari are very unpleasant for the guests to drink -- disquieting enough that they will completely destroy the guest’s pleasure when drinking the koicha*. ___________ *While this word is introduced in a discussion of koicha, katamari can also occur in usucha, and are just as insidious in that context. This is why the matcha should always be sifted using a cha-furui [茶篩] (a specially designed tea-sieve -- since something like a juice strainer may not have the wires close enough together to prevent minute katamari from sifting through) prior to use -- whether the tea will be put into a chaire or natsume, or simply used to prepare a bowl of tea tate-dashi.

⁴Including Jōō’s original collection (that was preserved in the Matsu-ya family archives), and Rikyū’s 1580 version.

This poem’s absence from the earliest manuscripts suggests that it was written by someone other than Jōō or Rikyū (possibly Hosokawa Sansai, since it is found in the collection associated with him, as well as the Sen family, which was relying on Sansai to fill in many of the details of their understanding of Rikyū and his ideas about chanoyu), and added to the collection -- perhaps in the interests of filling what was perceived to be an omission* that later generations felt was essential advice that needed to be passed on to the beginner in as authoritative a way† as possible. ___________ *The reader has to bear in mind that the way chanoyu was learned changed drastically between the mid-sixteenth century and the mid-seventeenth century (when all of the versions that did not come directly from Jōō and Rikyū were assembled).

In the sixteenth century, a person interested in chanoyu began by applying to join a tea group (usually one that had coalesced around one of the popular tea masters of the day -- with the master acting more as a living repository of knowledge, tradition, and precedent, while the actual work of teaching was delegated to his principal disciples). The beginner, once accepted, began participating in the group’s monthly or bimonthly chakai as a middling guest (where his primary responsibility was to watch the goings on quietly and with composure). Only after several years of this was the novice invited to learn the procedures (something that could be accomplished rather easily and quickly, since he was already thoroughly familiar with most of what he would learn in the context of the actual chakai). Thus the learning phase lasted no more than several months at most -- after which the novice began to host his own chakai for the group (receiving invaluable criticism after each).

During the seventeenth century, the modern system (where the student pays the teacher for lessons) began to make its appearance -- in this setting, the beginner usually had very little knowledge of, or experience with, chanoyu when he presented himself at the teacher’s kyōshitsu [教室] for his first lesson. As a result, matters that had formerly been obvious now needed to be explained, and explained in detail; and it was in this situation that the majority of the spurious poems were added to the collection -- in order to give an authoritative voice (no matter how false) to those arguments that the Sen family (and other leaders) felt needed to be emphasized, but which had not been addressed in earlier times.

†In other words, by putting the words into Rikyū’s mouth (since, by mid-century, the poems were already considered to have been exclusively Rikyū’s productions -- this was, in part, what inspired Katagiri Sadamasa to investigate Jōō’s own hand in the composition of the poems, which is how they became part of the Sekishū canon as well).

==============================================

◎ If these translations are valuable to you, please consider donating to support this work. Donations from the readers are the only source of income for the translator.

To contribute, please use the following link:

https://PayPal.Me/chanoyutowa

0 notes

Text

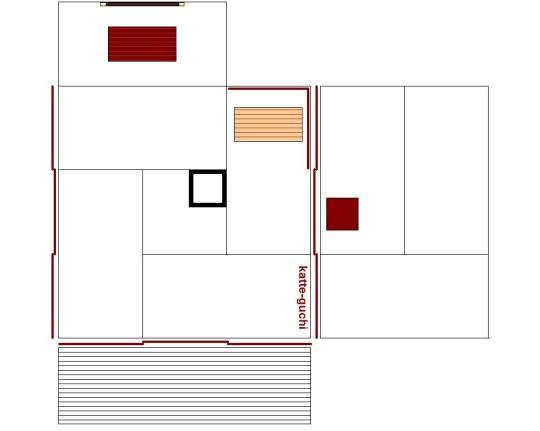

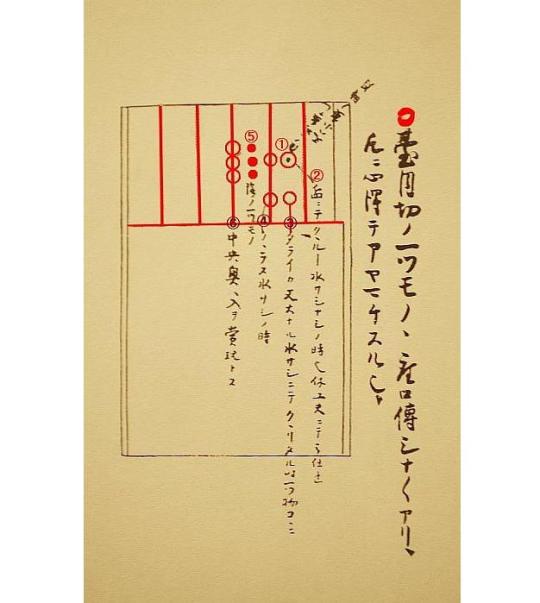

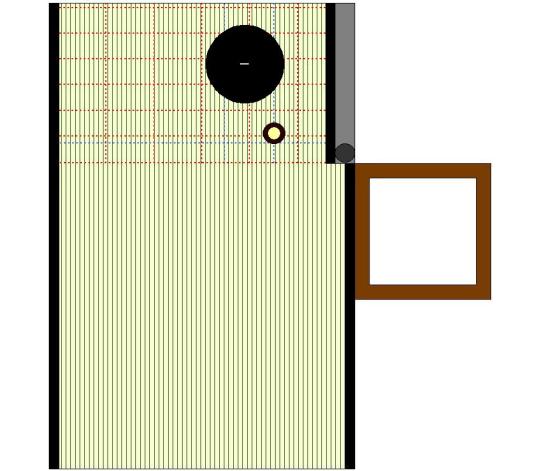

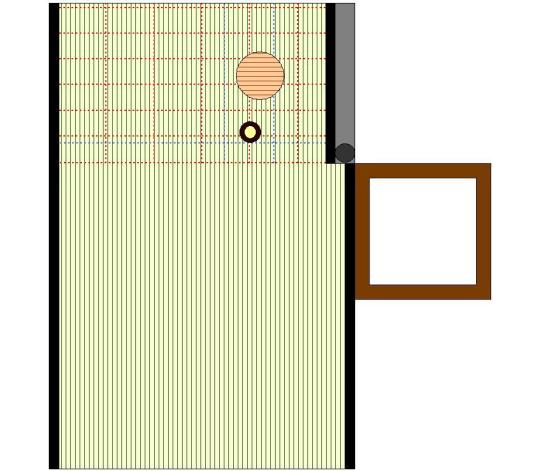

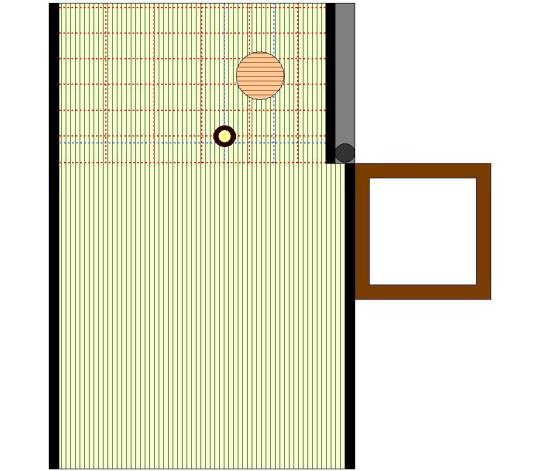

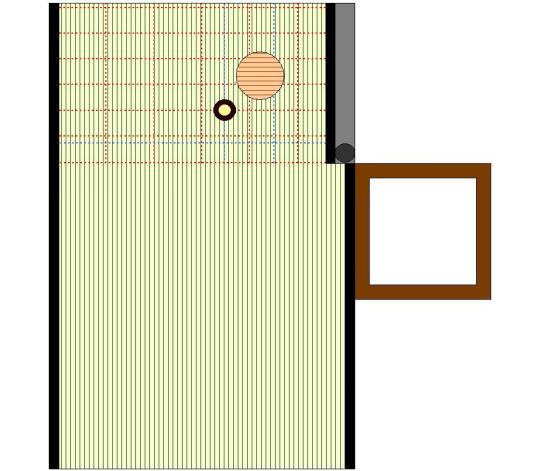

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (63): Rikyū’s Ji-butsu-dō [持佛堂].

63) Concerning [Ri]kyū’s ji-butsu-dō [持佛堂], to the east of the katte [勝手] attached to his two-mat tearoom, another two-mat room was [erected]¹. This [two-mat room] was surrounded, on three sides, by roofed verandas; and in the toko at the head of the room, [the image of his] “personal Buddha” was [installed]².

On the memorial days, when [Rikyū’s] thoughts turned to [his ancestors] and he performed a memorial service, invariably oshō [和尚], accompanied by this monk, were always invited to attend³. Inside the ji-butsu[-dō] the small utensils [= the chaire and temmoku-chawan] were of an even number; and these [utensils] were displayed on yin-kane. (If [you] asked [him] why [it was only the small utensils that were arranged on yin-kane], [Rikyū] would have replied that more than this was unnecessary [to cause the arrangement to be yin, as was appropriate when offering tea in memory of the departed]⁴.)

On one occasion, on the day of Sen’ami’s memorial service, [Rikyū] prepared tea using [his] small nasubi [chaire]: the chaire was displayed as an yin hitotsu-mono [一物]⁵.

_________________________

◎ According to Tanaka Senshō’s commentary, the description given here resembles the several Sen families’ Rikyū-dō [利休堂]* -- their memorial shrines to Rikyū as the ancestor of their families. As the language of this entry is likewise of the second half of the seventeenth century, this was probably another instance where an attempt was being made to validate these constructions by making it seem that Rikyū had used a similar sort of shrine to venerate his ancestors. This is also one of the few actual documents where the mysterious Sen’ami [千阿彌]† is named as the ancestor of the family.

Tanaka laments the fact that no drawing has come down to us to inform us of the room’s actual appearance -- as would have been expected given the rather vague description provided by the text.

It is important to point out that the Tokugawa bakufu wished to encourage the worship of the ancestors -- particularly those individuals who had been instrumental in their rise to power -- so it is probably in this vein that this entry was added to the collection. ___________ *The description given in this entry makes it difficult to associate this construction with any of Rikyū’s known residences. Since Rikyū always had the guests’ entrance on the north side of the tearoom, in a room where the guests’ entrance was in the same wall adjoined by the mukō-ro (the 2-mat rooms with a geza-toko [下座床]), this would place the ji-butsu-dō next to the wall behind the guests’ seats (which would impede the light entering through the important windows behind their backs); if it is referring to the Mozuno ko-yashiki (as most documents from the Edo period that can be clearly sited do), this would place the ji-butsu-dō beside the tearoom’s mizuya-veranda. Now while that is not inherently impractical -- especially since it seems that the ji-butsu-dō did not have its own attached katte -- it would obstruct the light entering the room from that side (the Mozuno ko-yashiki had a shōji panel as the door of the dōko, the intention of which was to allow light to enter at floor level; and if a building was constructed next to the mizuya), at least unless there was so much space between the two that the mizuya would not really provide any support to the ji-butsu-dō.

The fact that there was no katte, however, makes this room appear similar to the Mozuno ko-yashiki, however, because in that room, too, the host entered from the veranda (on which the guests sat during the naka-dachi).

The modern versions of the Rikyū-dō (usually referred to as sō-dō [祖堂], ancestor shrines) present in the several Sen family compounds have been rebuilt several times since the seventeenth century, and so their present iterations may not reflect their original shapes or configurations (indeed, they all seem to have been reimagined as places where a larger number of people could be seated, most of whom would be spectators to the act of offering of tea).

†This name indicates that he was an adherent to the Amidist sect from which chanoyu itself sprang; and he is purported to have been a member of the dōbō-shū [同朋衆] (though his name does not seem to be mentioned in this, or any other, capacity in any of the accounts from the Ashikaga period). Still, while he may not have served in Japan, as that system of high ranking governmental advisers providing a sort of cultural education to the ruler imitated the hwa-rang-do [화랑도 = 花郎道 or 花郎徒] of the Goryeo dynasty, it is possible that this person served in such a capacity in the court there, and that his memory was brought back from the continent by Rikyū, who chose to recognize him as the familial patriarch by taking the surname Sen [千] (which is a Korean family name, rather than a Japanese surname) as his own when he returned to Japan.

¹Kyū no ji-butsu-dō ha, ni-jō-shiki no cha-seki no katte yori, higashi no kata ni mata ni-jō-shiki ni shite [休ノ持佛堂ハ、二疊鋪ノ茶席ノ勝手ヨリ、東ノ方ニ又二疊敷ニシテ].

Ji-butsu-dō [持佛堂] is a dedicated room (often constructed as a separate building attached to the residence by a hallway or veranda) in a private residence in which a statue of the household’s “personal Buddha,” and the memorial tablets of their deceased members, are kept. It functions as a private oratory; and it is there that offerings to the ancestors (such as during New Year’s, and the O-bon festival) are made.

Ni-jō-shiki no cha-seki no katte yori, higashi no kata ni mata ni-jō-shiki ni shite [二疊敷の茶席の勝手より、東の方に又二疊敷にして] means “from the katte of the 2-mat tearoom, on the east side there was another 2-mat room.”

This 2-mat room would have been the ji-butsu-dō [持佛堂].

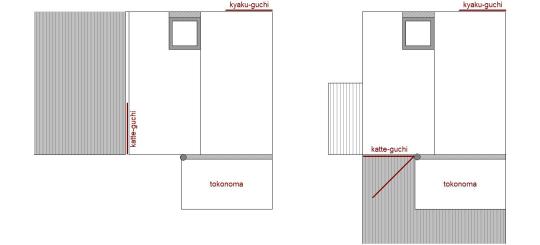

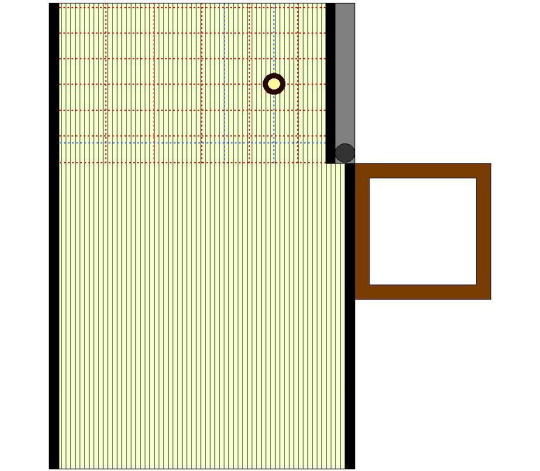

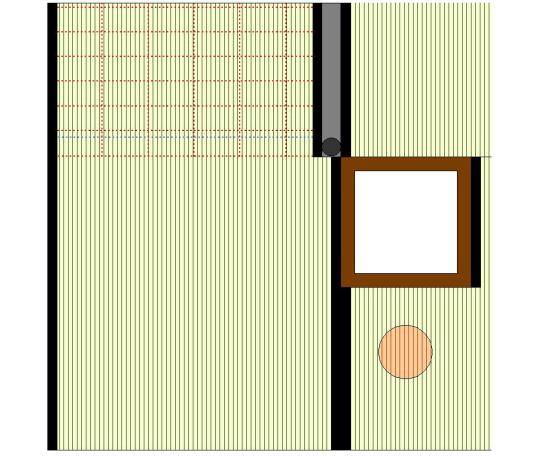

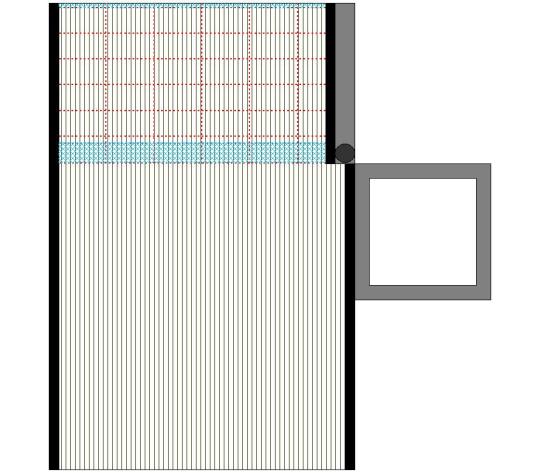

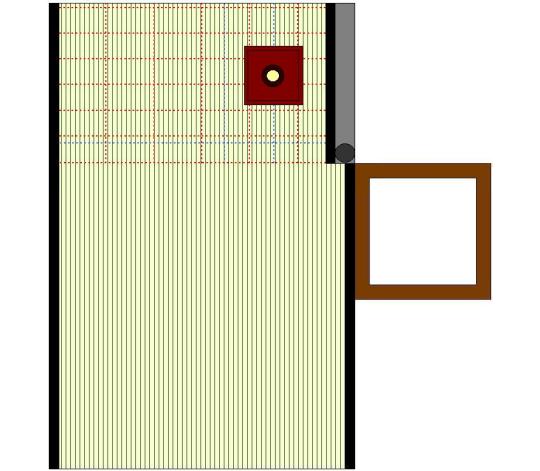

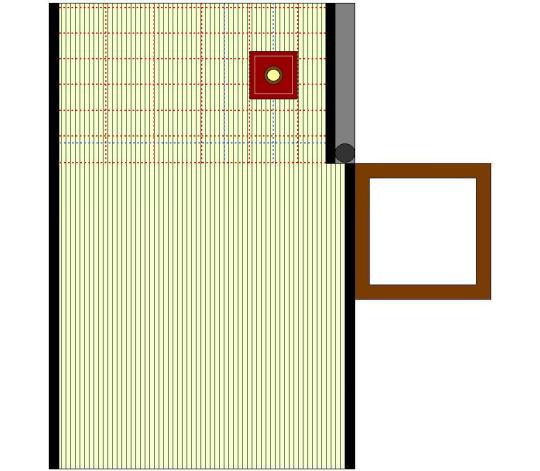

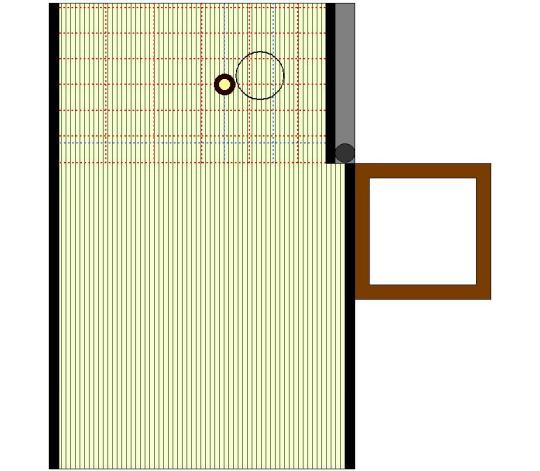

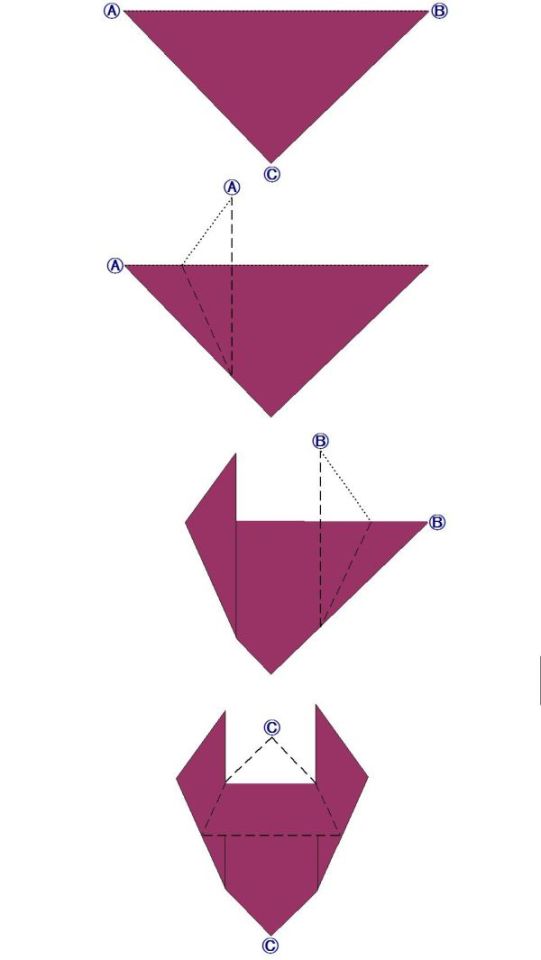

Since Rikyū preferred to have the guests’ entrance on the north side of the tearoom, and since his earlier 2-mat rooms were configured with a geza-toko [下座床]*, with the mukō-ro cut near the guests’ entrance, this means that the katte would have had to be either on the south or west side of the room, as shown below.

Because the tearoom itself is to the east of the katte in Rikyū’s earlier rooms (on the left), this text could not be referring to this kind of room.

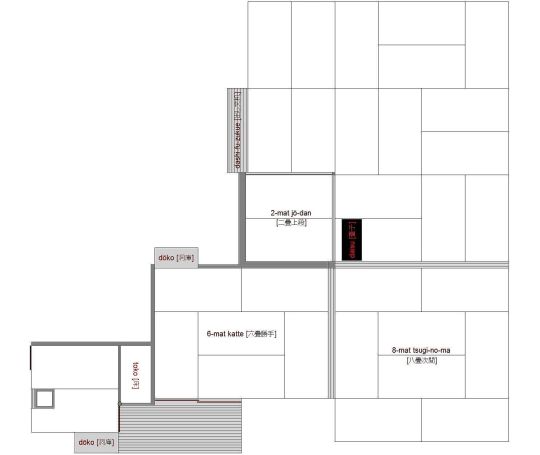

In the case of the room shown on the right, which was the sort of 2-mat room (with a hinged katte-guchi, that imitated that door originally proposed for the 1.5-mat room) that was erected in Rikyū’s residence in Kyōto, the problem is that to the east of the 6-mat katte was Rikyū’s 18-mat reception room (with 2-mat jō-dan) -- according to surviving records of this room on which the below sketch is based†. While some versions of this drawing show a single shōji in the wall perpendicular to the dōko in the katte (though with no mention of what lay beyond that door), if the veranda that surrounded the ji-butsu-dō on three sides adjoined the katte there, the ji-butsu-dō would be east of the 2-mat room, not its katte -- and such a construction would probably impact the lighting within the tearoom itself‡.

As for the Mozuno ko-yashiki, Rikyū’s final 2-mat room, it had a mizuya-dōko [水屋洞庫], and so did not have a katte at all.

In light of these details, it is difficult to understand the logistics from this description. __________ *A geza-toko [下座床], which had been Rikyū's preferred orientation for the toko in his small rooms since the creation of his 2-mat daime Jissō-an [實相庵] in 1555, is a toko located on the guests’ left, and so at the foot of the room (if the location of the mukō-ro is the upper side).

The 1.5-mat room (which was created not long after the 2-mat daime room) also featured a geza-toko -- though he quickly abandoned it since it was too difficult for the guests to use).

The geza-toko arrangement, regardless of the size of the room, allows the host to face the shōkyaku simply by turning toward his right. This enables him to offer the bowl of tea directly to that guest -- which may have been a large part of the reason for his favoring that orientation.

†It seems that Rikyū preferred to connect his 2-mat rooms to the main building, while it was the 4.5-mat room that was detached. The reason appears to have been because this allowed the guests to be served the kaiseki in the 6-mat katte; and at the conclusion of the gathering they would be able to walk directly into the shoin (which would have been an important detail when serving people such as Hideyoshi).

‡Several different representations of Rikyū’s residence within Hideyoshi’s Jurakudai [聚樂第] compound have come down to us. The above floor-plan is based on the only one that shows how the 2-mat room was connected to its katte, and, ultimately, to the 18-mat “colored shoin” -- though none of the drawings indicate the presence of a ji-butsu-dō anywhere on the grounds (admittedly, they only focus on showing the arrangement of the main buildings within the compound).

In one version of this sketch that is held by the Sen family (and on which Omotesenke’s reconstruction of the “colored shoin” is said to have been based), any reference to the 2-mat room is completely missing (and a notation on that document indicates that, rather than the pair of shōji that lead to the 2-mat room, a kuguri [クヽリ] -- presumably a nijiri-guchi or other low entrance of that sort -- was found in that place). While many of the other details of the six-mat room are the same, it is not named as a katte (probably since, without the tearoom, there is no other room to which it could serve as this appendage).

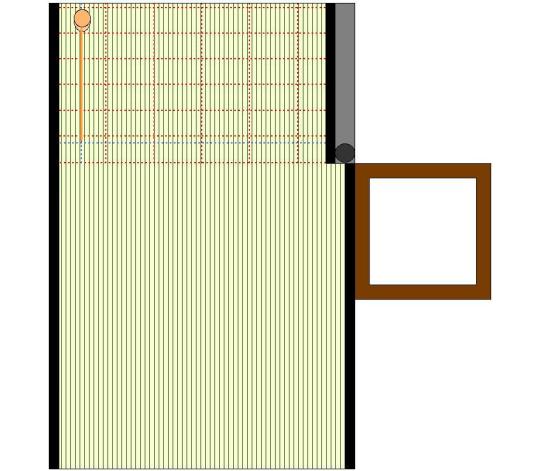

²San-bō ni hisashi wo mawashi, shōmen ni toko, ji-butsu ari-shi nari [三方ニヒサシヲマハシ、正面ニ床、持佛アリシ也].

San-bō ni hisashi wo mawashi [三方に庇を廻し]: hisashi [庇] means either an aisle room (a narrow room that encircles one or more sides of the main room, which allows servants and functionaries to move around without disturbing the people seated within the main room), with the outer sides facing the gardens -- with or without shōji or latticed shutters (shitomi-do [蔀戸]) to protect the interior from the weather, or its occupants from being spied upon); or, as here, a simple veranda protected by an overhanging roof (sometimes with a low balustrade standing at the outer edge).

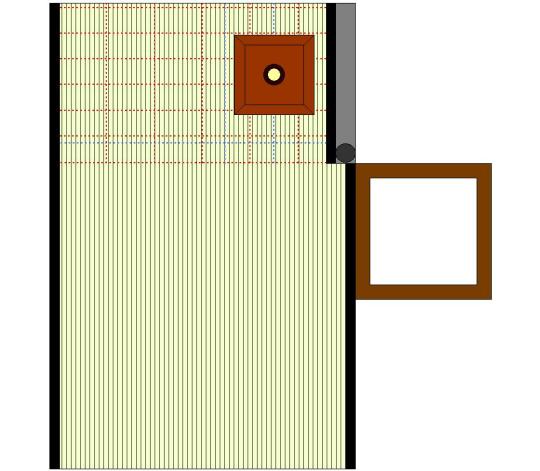

San-bō ni [三方に] means that the hisashi were found on three sides of the central room*.

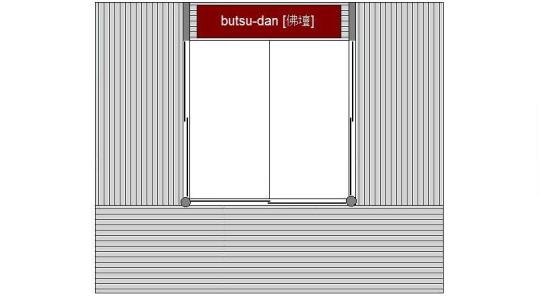

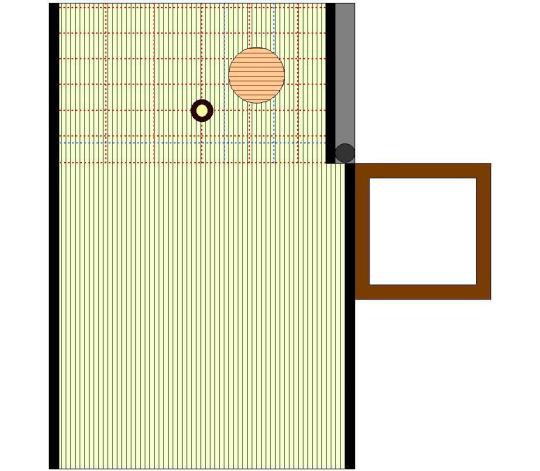

Shōmen ni toko [正面に床]: shōmen ni [正面に]† means directly, head-on -- that is, the toko was located at the deepest part of the room -- so the room was oriented like the Mozuno ko-yashiki, with the recess at the far end of the room. The hisashi (likely separated from the interior of this 2-mat room by three banks of shōji) surrounded the room on the other three sides. This is the arrangement shown below (the dimensions of the three hisashi are, of course, pure speculation).

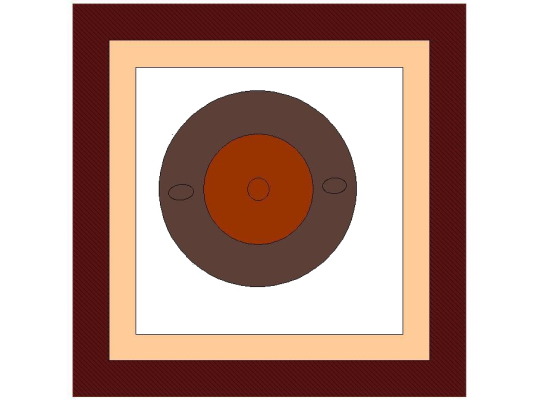

Ji-butsu ari-shi nari [正面に床、持佛ありしなり]: ji-butsu [持佛] means a personal image of the Buddha, one’s own Buddha statue. In other words, an image of the Buddha‡ was installed in the toko (probably resting on some sort of butsu-dan [佛壇], a Buddhist altar** -- together with an incense burner, a kōgō, one or a pair of candlesticks, and one or two small flower arrangements) -- along with the name-tablets of deceased members of the family. Possibly a kinran or brocade altar-cloth would have been spread underneath the censer, with a valance and curtains (suspended from the otoshi-gake [落し掛]) surrounding the butsu-dan on three sides.

Shibayama's version provides the reader with a little more clarity: san-bō ni hisashi tsuke-mawashi, shōmen ni toko ji-butsu wo kamaetaru jūkyo nari [三方ニヒサシツケ廻シ、正面ニ床持佛ヲ構ヘタル住居也].

San-bō ni hisashi tsuke-mawashi [三方に庇付け廻シ] means on three sides hisashi were attached around (the two-mat room's) periphery.

Shōmen ni toko ji-butsu wo kamaetaru jūkyo nari [正面に床持佛を構えたる住居なり] means a dwelling (or residence)†† in the forward part of which the ji-butsu (i.e., the butsu-dan [佛壇]) was enclosed within the toko.

That is, the butsu-dan on which the image and ancestral tablets were displayed was enclosed within the tokonoma. __________ *Tanaka Senshō, however, argues that buildings of this sort generally have hisashi on all four sides, which provide seating for various people who are participating (in an inferior capacity) in the ritual. Only the principal descendant of the departed, and the monks who were chanting the prayers, would enter the ji-butsu-dō.

†Presumably, shōmen [正面] means the side of the room that functioned as its focal point.

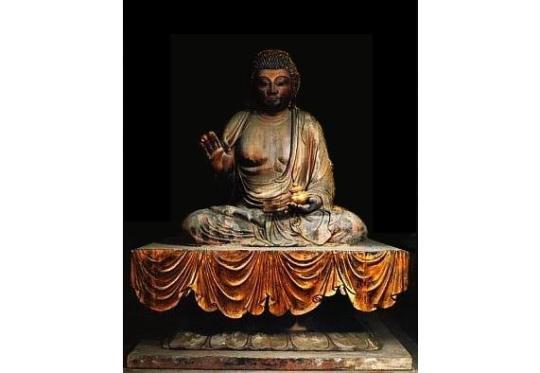

‡Today this would invariably be Shakyamuni (Siddhārtha Gautama), but the idea of ji-butsu also allows a representation of the Buddha (or even a Bodhisattva) to which one is particularly devoted -- in the case of most chajin of Rikyū's day, this would have been Amitābha (Amida [阿彌陀]) as the Lord of the Pure Land and the principal Buddha of the Ikkō-ichi-nen-shū [一向一念宗].

Though even Bhaiṣajyaguru (Yaku-shi nyorai [藥師如來]), the Bodhisattva of Healing (shown above) under whose protection chanoyu is included (and who is often depicted holding a small jar, like a chaire, in his left hand).

**While I have shown the butsu-dan extending across the entire width of the room, many of the commentators make the tokonoma 3-shaku, 4-shaku, or 4-shaku 2-sun wide, with the butsu-dan reduced accordingly. Some even envision a circular opening in the wall, covered by a pair of small shōji that open onto a recess wherein the Buddha statue and its accompanying objects were enshrined.

While these various representations imitate what is seen in the Sen families’ sō-dō [祖堂], they would be more appropriate to the Edo period than to Rikyū’s day. Rikyū would probably have used a rather long, somewhat narrow, table that extended across the width of the room (as I have shown) -- based on the way things have traditionally been done, with respect to ancestor-worship altars, in both China and Korea.

††Jūkyo [住居] means a residence or dwelling. Whether this is referring to Rikyū's compound, or to the toko (as the place where the ji-butsu “resides”), is unclear.

³Ekō kokorozashi no kuyō-bi ni ha, kanarazu oshō narabi ni kono-bō wo manekare-shi ni [囘向心ザシノ供養日ニハ、カナラズ和尚幷コノ坊ヲ招カレシニ].

Ekō [回向]* means to hold a memorial service (for a departed person).

Kokorozashi [志]†. Shibayama explains this usage in the following way:

sono seisha ni kokoro wo mukuru i ni te, ki-nen to iu ni onaji‡

[其逝者ニ心ヲ向クル意ニテ、記念ト云フニ如ジ].

“The meaning is to turn one’s thoughts to the deceased; it is the same as saying to commemorate or honor the memory of (someone).”

Kuyo-bi [供養日]: kuyo [供養] is a Buddhist term meaning a memorial service. Kuyo-bi [供養日], then, would name the day of the memorial service.

Kanarazu oshō narabi ni kono-bō wo manekare-shi ni [必ず和尚ならびこの坊を招かれしに] means certainly (kanarazu [必ず]) oshō** [和尚], and also (narabi ni [ならびに]) this monk††, would be invited (manekare-shi [招かれしに]).

In other words, Rikyū had the desire that, as a way to do honor to the deceased, he would always invite ōsho [和尚] and Nambō Sōkei to the memorial service. Apparently with the intention that they chant prayers during the offering of tea at the altar.

Shibayama’s text suggests a slightly different interpretation might be in order: ekō kokorozashi no kuyō-bi ni ha, kanarazu kore ni te oshō narabi ni kono-bō wo manekite cha ari-shi ni [回向志ノ供養日ニハ、必コレニテ和尚幷ニ此坊ヲ招キテ茶アリシニ].

This means on the memorial day on which Rikyū turned his thoughts to the performance of the commemorative service, (he) would certainly invite oshō and this monk for tea on this occasion.

Perhaps he is thinking of hosting a chakai for the two monks after the service is finished (as a way to express his thanks for their presence and prayers)? __________ *Ekō [囘向] uses one of those strange kanji variants that became fashionable during the seventeenth century.

†Kokorozashi [心ざし], as this word is written in the Enkaku-ji text, is the same nonstandard form found in the preceding (and other) entries -- suggesting that they were either written or edited by the same individual or group.

‡Onaji [如じ] is possibly a variant (and non-standard) way of writing the word onaji [同じ]. It is equivalent to gotoshi [如し], meaning “the same as.”

**According to Hisamatsu Shin-ichi [久松真一; 1889 ~ 1980] sensei, the editor of the Sadō ko-ten zen-shū [茶道古典全集] version of the Nampō Roku, the title oshō is referring to Shōrei Sōkin [笑嶺宗訢; 1505? ~ 1584].

However, Hideyoshi's Jurakudai (in which the most likely version of Rikyū’s two-mat room seems to have made its first known appearance) was not completed until 1586. In that case, and assuming that this particular ji-butsu-dō is the one that would have been built somewhere on the grounds of Rikyū's residence there, oshō would more likely refer to Kokei Sōchin 「古溪宗陳; 1532 ~ 1597].

Perhaps it should be added that, while Shibayama Fugen says nothing regarding the supposed identity of this “oshō,” Tanaka Senshō agrees with Hisamatsu sensei’s assessment.

††In other words, Nambō Sōkei.

⁴Ji-butsu no uchi, ko-dōgu in-kazu in-kane nari-shi hodo ni tazune-sōroeba, anagachi ni sono sata ni mo oyobu-bekarazu to ha no tamai-shi nari [持佛ノ内、小道具陰數陰カネナリシホドニ尋候ヘバ、アナガチニ其沙汰ニモ及ベカラズトハノ玉シ也],

Ji-butsu no uchi [持佛の内] means within the ji-butsu-dō.

Ko-dōgu in-kazu in-kane nari-shi [小道具陰數陰カネなりし]: according to the previous entry, ko-dōgu [小道具] refers, in this context, to the chaire and the temmoku. The number of these things should be an even number*, and they should be displayed on yin-kane.

Hodo ni tazune-sōroeba [ほどに尋候えば] means if (you) should ask the reason for this -- in other words, if you should feel inclined to ask about why only the chaire and chawan need to conform to the yin-kane (rather than all of the other utensils).

Anagachi ni sono sata ni mo oyobu-bekarazu to ha no tamai-shi nari [強ちにその沙汰にも及ぶべからずとはの給いしなり]: anagachi ni [強ちに] means (not) necessarily, (not) always; sono sata ni mo [その沙汰にも] means also (when) handling† such things; oyobu-bekarazu [及ぶべからず] means should not go beyond (something), should not exceed (something).

In other words, this is saying that it is not necessary for anything but the chaire and chawan to be associated with a yin-kane in order to achieve a yin arrangement‡. __________ *Meaning that both the chaire and the chawan should be displayed together. Placing out the chaire only (and carrying in the temmoku later), for example, would be a violation of this rule.

†Specifically, deciding what is right -- as opposed to what is wrong -- in a given setting or situation.

‡Preparing tea in memory of a departed person requires a yin arrangement.

Whether the host is using a daisu, or arranging the utensils directly on the mat, the positions of the other utensils -- the furo or (in the case of a 2-mat room) mukō-ro, the mizusashi, and so on, are mostly fixed, and cannot be changed.

⁵Aru-toki Sen’ami no nenki-no-hi ni, ko-nasubi ni te cha-taterareshi ni ha in no hitotsu-mono nari [アルトキ千阿彌ノ年忌日ニ、小ナスビニテ茶立ラレシニハ陰ノ一物也].

Aru-toki Sen'ami no nenki-no-hi ni [ある時千阿彌の年忌日に]: aru-toki [ある時] means on one occasion*; Sen’ami† nonenki-no-hi ni [千阿彌の年忌日に] means on the day of the anniversary of Sen’ami's death.

Ko-nasubi ni te cha-taterareshi [小茄子茶入にて茶立られし] means that Rikyū prepared tea (during the memorial service) using a small nasu-chaire‡.

In no hitotsu-mono [陰の一物] means that Rikyū displayed this chaire so that it was resting squarely on a yin-kane** -- with the implication being that this was done as a gesture of respect (both for Sen’ami, and for the chaire).

Shibayama Fugen's version of the text has aru-toki Sen’ami no nenki-hi ni, ko-nasu ni te cha-taterareshi ni ha, in no hitotsu-mono ni okare-shi nari [或時千阿彌ノ年忌日ニ、小茄子ニテ茶立ラレシニハ、陰ノ一物ニ被置シナリ]. But aside from the minor changes in punctuation, and the final okare-shi [被置し = 置かれし] (this verb only states what is already obvious from context) -- all of which help the reader arrive at the correct understanding -- the basic meaning remains the same. ___________ *The implication being that Rikyū used a different set of utensils on every occasion, or at least changed them frequently enough that the author thought this was worth a mention.

This, of course, fits into the ideas that the bakufu was promoting during the first century of the Edo period. For that matter, so does the idea of venerating ones ancestors -- by constructing a dedicated memorial oratory (sō-dō [祖堂]) of some sort (something that remained fairly common, at least among the middle to upper classes in Japan, until fairly recently).

†Sen’ami [千阿彌] was supposed to have been Rikyū's grandfather (though “grandfather” is often used more loosely to mean progenitor or ancestor, regardless of the actual number of generations that separate said person from the present). While modern Sen family mythology states that he was one of the dōbō [同朋], “companions,” serving the Ashikaga shōgunate, his name does not seem to appear in any of the relevant records from that period.

Since the dōbō-shū seem to imitate a similar sort of system that provided training and advice to the Koryeo kings, and (perhaps more importantly) because Rikyū began to voice this understanding of his ancestry only after he returned to Japan from his stay on the continent, the possibility should be considered that Sen’ami was a functionary of the Koryeo court. (A possibility that most Japanese tea people, at least, would find repulsive -- given the ties between modern day chanoyu and the ultra-nationalist camp that has ruled the Japanese nation since the beginning of the 20th century, and which has been largely responsible for rewriting Japanese history as a repudiation of the archaeological and anthropological studies conducted by western-trained Japanese scholars during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in both Japan and Korea.)

‡While this seems to be a direct allusion to the preceding entry, and while Rikyū did own a ko-nasu chaire, his chaire measured just over 2-sun in diameter, rather than the 1-sun 5- or 6-bu that was prescribed there.

Interestingly, in the Taishō mei-ki kan [大正名器鑑], Takahashi Sōan states that this chaire was the model for Rikyū's small natsume made by Seiami [盛阿彌] (Hideyoshi's principal lacquerer) -- that is, the shape of the lower part of that natsume (up to the point of maximum diameter), as well as its height and diameter, were based on this small nasu-chaire.

**This seems to be an allusion to the mitsu-gumi arrangement that was discussed in the previous entry (though it is unlikely that Rikyū performed that sort of chanoyu in his ji-butsu-dō).

0 notes

Text

March 13, 2021: Kwaidan: Hoichi the Earless (1965)

Um...yeah, no idea, people.

Not sure what “the earless” means, but it worries me. So, rather than try to guess here, let’s get right into it!

This is the third of four tales presented in the film Kwaidan, listed here:

The Black Hair (黒髪, Kurokami)

The Woman of the Snow (雪女, Yukionna)

Hoichi the Earless (耳無し芳一の話, Miminashi Hōichi no Hanashi)

In A Cup of Tea (茶碗の中, Chawan no Naka)

Here we go again! SPOILERS AHEAD!!!

Recap (3/4): Hoichi the Earless

A musician sings a song, known as “The Tale of the Heike”, and is specifically detailing the epic Battle of Dan-no-ura, during which two clans fought each other at the end of a great war. The scene is played out on screen as kabuki theatre, with the singer strumming an instrument in the background of the epic clash. It’s, uh...it’s pretty goddamn rad, not gonna lie to you.

Don’t know if you guys have ever seen kabuki theater, like legit kabuki theater, but it’s genuinely interesting. If you want to see an example accessible to non-Japanese audiences (and nerds like me everywhere), check out Star Wars Kabuki-Kairennosuke and the Three Shining Swords! Here’s a link! It is also rad.

Anyway, the epic tale of war and suicide results in a haunted shoreline, on which the mysterious Heike crabs appear with faces on their shells. But as the story ends, we meet its teller: Hoichi (Katsuo Nakamura), a blind monk who works at a temple. One day, a noise draws him inside one of the buildings of the temple. He attempts to investigate, but finds no one there. Confused, he decides to settle down and play his instrument, the biwa.

But as he does, a soldier (Tetsurō Tamba) appears with a message: his master wishes to see the site of the battle of Dan-no-ura, and also wants to hear Hoichi recite his version of the battle. While Hoichi doesn’t think himself worthy, he still goes along with the mysterious soldier, who takes him...towards the shore. So, dude’s a ghoooooooost, and Hoichi’s also to be fuuuuuuuucked. The soldier takes Hoichi to the beautiful azure temple to see his master.

Yeah, no, it’s definitely haunted, and Hoichi’s either dead, or is about to be dead. Or...wait, is this an Orpheus story? You know, a mortal recording artist so good that even the gods love his hit singles? Dunno, just came to me, so we’ll see. Anyway, he’s brought into the definitely not haunted temple, bedecked in tattered red flags, with beautifully spectral backgrounds all throughout.

Meanwhile, on the shore, a young man is found dead on the shoreline. We don’t see his face...but I have a bad feeling I know who it is. Although, it seems that it might be a fisherman whose boat recently sank...maybe. I’m still not convinced. The other monks wonder where Hoichi’s disappeared to, and then he reappears later that night. OK, cool, he isn’t dead. That warrior from before definitely was, though.

Hoichi never tells the monks where he disappeared to, but he’s soon called back to the mysterious temple by the warrior, who is indeed a ghost. Apparently, they commanded Hoichi not to tell anyone of their meetings, a command which he obeys willingly. Subsequent visits continue, but they obviously start to take a toll on Hoichi, who’s beginning to look, well...gray. Uh oh.

The head monk questions him on his disappearance, but Hoichi makes up an excuse about “needing to finish something, heedless of the hour”. And yeah, he REALLY doesn’t look good. Looks like this one’s gonna be another “don’t fuck with ghosts” lesson, huh? But Hoichi doesn’t really care, as he goes out even in a massive rainstorm. As his fellow monks look for him, he’s playing once again for the ghosts, which includes a child emperor seen in the epic song reenactment seen earlier. So, yeah, these are the spirits lost on the day of the Battle of Dan-no-ura. And those spirits want to hear that song once again.

And, of course, Hoichi plays it for them on the biwa. When ghosts tell you to play a song for them, you goddamn DO IT. We see him play it and the song for them, and all the while, the other monks are looking for him. As they do, will-o-the-wisps appear before them. Which, yeah, is another Pokémon, just saying. Both Gastly and Litwick are basically will-o-the-wisps.

But OK, back to the actual ghost story, as Hoichi plays the biwa with some crazy-ass intensity. As he does, the people he’s playing for change from the emperor and his people to the samurai of the opposing side.

The spirits listen, as we see a painting of the battle and the disaster that came from it. The spirits, ALL of them, listen on, as the scene changes from an attentive spiritual audience, to a battle scene. And, uh...it’s intense. And terrifying. And genuinely very haunting. And while Hoichi can’t see any of it, we can. And again, it is HAUNTING, my lord. And then, as the monks arrive to find Hoichi singing, the spirit court fades away, and Hoichi is instead surrounded by will-o-the-wisps. My God.

The other monks try to take the clearly fucked up Hoichi back to the temple, planning on giving him an exorcism to cleanse him of these spirits. But the spirits, now seen in Hoichi’s absence, all rise as he leaves. Tattered red flags hit water, and the spirits disappear, AND I WILL HAVE NIGHTMARES TONIGHT. Now exposed, Hoichi is spoken to by the head monk, who reveals that doing what a spirit tells you to do is a sure fire way to open yourself up to their influence. And so, a plan is formed, in order to protect Hoichi from further possession. And to do that...it’s time for some painting.

Yeah, the monks paint Buddhist symbols all over Hoichi, hoping to protect him from the spirits influence. And they write ALL OVER him, and it’s both a gorgeous sight, while also being...well, extremely eerie. They paint all over him, in black and red script, even painting his eyelids. The GF pointed out that they’re putting the larger red symbols on his chakras, which makes sense and is neat. They even paint his hair, which is genuinely impressive.

The plan is then formed to let Hoichi outside to act as bait for the spirit to come back. He’s told not to make a sound in front of the spirits, and that he mustn’t move in front of them either. If he does, the spirits will tear him to pieces. But he’s still protected by the Heart Sutra, which is painted all over his body. Except for...his ears. Oh, shit, I think I know what’s gonna happen to poor, sweet Hoichi.

Sure enough, the Spiritual Samurai shows up, and is unable to see every part of him...except for his ears. GODDAMN IT DONKAI (the monk who painted the symbols on him), YOU DUMBASS. Well, the spirit believes that only his ears are left, and the spirit needs proof of Hoichi’s fate...so he takes his ears. And when I say he takes his ears, I mean that HE TAKES HIS FUCKING EARS. HE. RIPS. OFF. HOICHI’S. EARS. And Hoichi doesn’t make a goddamn sound as he bleeds profusely. HOLY FUCKING SHIT DUDE

With that, Hoichi bleeds his way to another part of the temple. Injured, he’s cared for by the head monk and DONKAI, who’ve realized Donkai’s grave mistake. And Hoichi is now Hoichi the Earless. Remind me never to fuck with the spirits without checking EVERY. SINGLE. MINUTE. DETAIL. Hoichi’s basically traded his ears for his life. And the spiritual visitors will no longer visit, according to the head monk. Meanwhile, Hoichi the Earless is now pretty famous, due to his unusual predicament. A wealthy lord wants to meet the strange young man, n as brought along a bunch of people to watch him play. While the monks tell him to refuse the request, he still plays to honor the fallen spirits regardless.

Soon, he and the temple are given money and gifts from all over the place, and Hoichi gains much personal wealth and fame. However, it never was about that for Hoichi, really. He just plays.

And that’s Hoichi the Earless! Wow. Interesting ending. Three out of four! Let’s go to the last, shall we? See you there!

#kwaidan#怪談#masaki kobayashi#hoichi the earless#hoichi-the-earless#Miminashi Hōichi no Hanashi#耳無し芳一の話#Katsuo Nakamura#Tetsurō Tamba#Takashi Shimura#Yoichi Hayashi#Yōsuke Kondō#usermichi#mormarsli#my gifs#mygifs#fantasy march#365 movie challenge#365 movies 365 days#365 Days 365 Movies#365 movies a year#user365

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

March 13, 2021: Kwaidan: The Woman of the Snow (1963)

Y’ever see Interviews with Monster Girls?

Absolutely one of my favorite slice-of-life anime from the past few years, and I genuinely want to rewatch it! Might do so after this, honestly. The conceit of the series is that the main character, a biology teacher named Takahashi, is trying to better understand and help with the issues of the “demi-humans” that attend the school. There’s the vampire girl, Hikari; the dullahan (best character), Kyoko; the math teacher succubus Sakie; and Yuki Kusakabe.

Yuki, as implied by her name is a yuki-onna, also known as a snow-woman. Now in the show, she’s a shy girl who’s always cold, and she’s great. But in mythology, the yuki-onna is...different. A tall woman with long black hair and blue lips, the serene snow woman appears to travelers in blizzards, and freezes them with her icy breath.

While the yuki-onna does have a soft side, she’s best known for her vengeful nature. The only stories that I’ve heard of come from the anime, honestly. There’s one with two woodcutters, an old one and a young one. Old guy gets frozen, young guy doesn’t. Don’t quite remember the reason for that. In another story, the yuki-onna is brought in by a kind young man, and she melts in the warmth. I know there are others, but those are the ones I remember.

Oh, and there’s a Pokémon based on this one, too. Pokédex entry says this about it:

Froslass, the Snow Land Pokémon. An Ice/Ghost type. Legends in snowy regions say that a woman who was lost on an icy mountain was reborn as Froslass.

Seeeee? OK, enough background, let’s get to the movie! Film ain’t gonna watch itself, y’know. The second of four tales presented in the film Kwaidan, listed here:

The Black Hair (黒髪, Kurokami)

The Woman of the Snow (雪女, Yukionna)

Hoichi the Earless (耳無し芳一の話, Miminashi Hōichi no Hanashi)

In A Cup of Tea (茶碗の中, Chawan no Naka)

Here we go again! SPOILERS AHEAD!!!

Recap (2/4): The Woman of the Snow

We start, well...in the snow.

An eye glares at us through it, eerily, and we’re told of two woodcutters, Mosaku and Minokichi (Tatsuya Nakadai), an old and young man respectively. They travel from their village to the cold mountainside, and are one day beset upon by a fierce blizzard. As they trudge through it, eyes are watching them in the background. It’s extremely eerie, to be honest.

The old man is lost in the blizzard, but the young an struggles through it. As he does, he looks up and sees eyes in the sky, as if made of the moon itself. He finds himself trapped on one side of the river, and also managed to find the older man once again through it all. They make it to the hut of a boatsman, who’s already left down the river before the blizzard. But the wind is strong, and the door swings open as the wind wails, as if a voice were crying on it.

The younger woodcutter settles in for the night, and then OH NO

FUCK ME DUDE THAT’S GODDAMN TERRIFYING

The older woodcutter’s dead as SHIT, frozen by the breath of the Yuki-onna (Keiko Kishi). But she seems to like the younger man, smiling in a way that has scared him and me off of water for life. Like, it’s intense enough that even liquid water would remind me of this terrifying spirit. Same with the dude. But here’s the thing: I can tell you guys about this. He can’t.

See, she spares the younger woodcutter’s life on one condition: he can NEVER tell ANYONE about it. If he tells anyone, INCLUDING his mother (she specifies that), she WILL come and kill him. And odds are gonna be that that’s exactly what he’s gonna do, the great numpty.

She leaves, and the blizzard eventually subsides. The man is found and nursed back to health by his mother. A year passes, and Minokichi doesn’t say SHIT about what happened. One day, he’s cutting wood in the forest, against a sunset that is definitely a set-backdrop, but still looks gorgeous. He walks past a beautiful woman, and asks what she’s doing out there. The woman is on her way to the city of Edo, and is hoping to secure a job there.

However, the two get to know each other on the walk, and start to talk. He introduces her to his mother, and we learn that her name is Yuki, and I REMEMBER THE REST OF THIS STORY NOW. It’s from Tales from the Darkside: The Movie!

YEAH. I’ve seen Tales from the Darkside: The Movie, and I haven’t seen The Godfather, I KNOW. Anyway, the film adapted this story into a short called Lover’s Vow, and replaced the yuki-onna with a...gargoyle monster, I think? Its never made completely clear. Anyway, the same thing happens, where he witnesses the creature kill somebody, and it spares his life if he doesn’t tell anyone of the encounter. He agrees, then later on meets a woman with whom he falls madly in love, and THEN...well, hold on a hot sec, here. That’ll spoil the movie.

Anyway, just like the story, this woman is the yuki-onna. I mean, c’mon, her name is Yuki, for Chrissakes. The two fall in love, and eventually have sex in a field. We had friends over, and I was gonna watch this movie at the time, and it’s a good thing I didn’t because that’d be awkward!

They marry, have three kids, and spend about ten years together. However, soon after this, Minokichi begins to realize who exactly Yuki is. The light on Yuki’s face reminds him of the night that the yuki-onna came. Without thinking about it, he tells her about that night, which he’s never told anybody about.

Here’s the thing, even during the day, we’ve seen eyes in the sky. Because she’s always watching him. and watching his actions. And as he tells the story of the yuki-onna’s visit...well...

Yeah, it’s her. After that dumbass is done with his story, she revealed herself, and spurns him for breaking his promise not to tell anyone, in exchange for his life. And he just broke that goddamn promise. And how she’s gotta kill him, and take the kids away from him as they transform into snow children, but like in Tales from the Darkside: The Movie, right?

Well...no, actually. Because, to my surprise, their kids together is what stops her. Because he broke his promise, she can no longer be a part of their lives. But she loves the children, and also loves him. She tells him that he better raise them right, and with care. If he ever mistreats then, she’ll kill him. And then...

She’s gone. Minokichi leaves the sandals that he was going to give Yuki outside, heartbroken at the loss of his wife, and at his own idiocy. She accepts his gift.

And that’s The Woman of the Snow! VERY cool. Pun...lightly intended. See you for Number 3: Hoichi the Earless! That title worries me! See you there!

#kwaidan#怪談#masaki kobayashi#the woman of the snow#yukionna#yuki-onna#Tatsuya Nakadai#Keiko Kishi#Yūko Mochizuki#usermichi#fantasy march#user365#365 movie challenge#365 movies 365 days#365 Days 365 Movies#365 movies a year

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 6 (49.2): the Shin [眞] Forms of the Kō-kazari [香飾], Part 2.

49 [continued]) There is the case where a request to appreciate incense is made by the guests¹. Whereupon:

◦ the sumi-tori is carried out and placed next to the ro².

◦ From within the sumi-tori two tadon [炭團] are taken out and put into [the ro], so they will start to burn³.

◦ While adding water to the kama and so forth, the tadon will be catching fire⁴.

◦ The kōro is lowered [from the shelf], the [kō]bon is rearranged⁶, and the fukuro is removed from the kōro⁷.

◦ [Then] one tadon is put into [the kōro], to heat the ash⁸, while the other tadon is allowed to develop its hi-ai fully [in the ro]⁹.

◦ [Meanwhile, the kōro] is rested on the tray, and, once again, [the tray] is raised up onto the shelf¹⁰.

◦ Then, the kama is suspended [over the ro]¹¹.

◦ After everything else [that needs to be done in the sumi-temae] has been finished at a leisurely pace¹², because incense will follow, the ash [in the kōro] should be drawn up [into a shallow cone, to prepare it to receive the gin-yō [銀葉], and the piece of incense]¹³.

In the aforementioned instance, when the burning [charcoal] was taken [and put into the kōro], should it not have followed that [appreciating] incense would happen right away? Why, then (Rikyū asked Jōō), was [the kōro] lifted up to the shelf once again?¹⁴

[Jōō replied,] the correct condition of the heat is absolutely crucial¹⁵. If the burning [charcoal] is too hot, with heat like that the temperature will be too extreme¹⁶. [So] if you want to burn something like an old variety of meikō [名香], [this kind of heat] will be unsuitable: the condition of today’s fire is completely inappropriate¹⁷.