#Chatham albatross

Text

[2170/11079] Chatham albatross - Thalassarche eremita

Order: Procellariiformes (tubenoses)

Family: Diomedeidae (albatrosses)

Genus: Thalassarche (mollymawks)

Photo credit: JJ Harrison via Macaulay Library

#LOOK. AT. THIS. BIRD#we should have a lil party every time we get an albatross#woop woop#birds#Chatham albatross#Procellariiformes#Diomedeidae#Thalassarche#birds a to z#described

171 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil Novembirb 3: Race to the Sea

Among the rapidly diverging groups of dinosaurs right after the end-Cretaceous extinction were quite a few groups that went "hey, the ocean... it's full of food... let's go there"

And the ways they went there? Multifaceted and Fascinating

Today, we know of plenty of different types of marine birds, around the world. But in the Paleocene, the hotspot of marine bird evolution was Aotearoa, aka Zealandia.

Here, many early marine birds evolved, stretching out their wings in one way or another to grab the nearest available food sources. One common way modern birds live on the sea is by soaring - rarely touching ground, living their lives over the water, looking for food.

And this mode of life appears to have evolved early, with the first tropicbirds evolving right out the gate with Clymenoptilon. And it wasn't alone among flighted marine birds! Protodontopteryx, the first pseudotoothed bird, is also known from the Paleocene of Aotearoa.

Protodontopteryx by @otussketching

Pseudotoothed birds are one of the most common clades of fossil bird, having thrived in marine habitats across the world until the start of the Pleistocene. Like all modern birds, they weren't able to just re-develop teeth, as the gene for enamel had been lost. However, they - like many other birds that eat on slippery or finnicky prey - worked around that by evolving fake "teeth", or projections, on the parts of their body they did still have.

Most living birds evolve such things as lamellae, aka, little pointy bits on their tongues.

Pseudotoothed birds did so by evolving jagged edges out of their jaws.

And the early Paleocene is where that all started!

That said, Protodontopteryx does not seem suited to soaring flight, and probably lived most similarly to living albatross, selecting targeted prey and sticking close to the shore - the start of a long love affair with the ocean for the clade.

Waimanu by Nobu Tamura

Of course, the reason we're all here is penguins. Penguins are some of the most charismatic birds today, even dubbed the "pinnacle of dinosaurian evolution" by one Dr. Thomas Holtz. And they appeared right away in the Paleocene, showing up just after the impact event - and showcasing a dramatically rapid evolution towards fully marine life.

Early penguins were weird transitional birds, a cross between a normal Neoavian and their later shape, which looks remarkably like living loons and divers. The first penguins we have, Waimanu and Kupoupou, were very similar to modern penguins - so we don't exactly know how this transition started, or when penguins eventually lost flight. Muriwaimanu, however, did show a different form of swimming through the water, indicating that modern penguins developed it later.

Though, they fly through the water, so it's not like they lost it for nothing!

Kumimanu by Nobu Tamura

The ocean, though depleted from the asteroid impact, recovered faster than the land, and was filled with a variety of food items that these different kinds of birds could feed on. Molluscs, Crustaceans, worms, and fish were all available, allowing Aotearoa to host a diverse flock of marine birds, and for penguins to diversify rapidly.

Because, quickly after the evolution of the first penguins, we start to see more and more - and they were huge. Kumimanu was much bigger than living penguins, and Sequiwaimanu had legs similar to other large penguins found in the region.

This was just the start of the Golden Age of Penguins, and we'll revisit them later. We have some other giant birds to meet first...

Sources:

Blokland, J. C., C. M. Reid, T. H. Worthy, A. J. D. Tennyson, J. A. Clarke, R. P. Scofield. 2019. Chatham Island Paleocene fossils provide insight into the palaeobiology, evolution, and diversity of early penguins (Aves, Sphenisciformes). Palaeontologia Electronica 22 (3): 22.3.78.

Mayr, 2022. Paleogene Fossil Birds, 2nd Edition. Springer Cham.

Mayr, G., V. De Pietri, L. Love, A. A. Mannering, R. P. Scofield. 2019. Oldest, smallest, and phylogenetically most basal pelagornithid, from the early Paleocene of New Zealand, sheds light on the evolutionary history of the largest flying birds.

Mayr, 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance (TOPA Topics in Paleobiology). Wiley Blackwell.

67 notes

·

View notes

Note

For the fanfic director’s cut: ⭐️⭐️⭐️

I was going to respond seriously to this, but when I went to find the appropriate googledoc, the googledoc I had open already was "Penguins (A Divine Quest, Probably)", the planning doc for the D&D 5e campaign I ideated by never ran (yet). The premise is: all players are penguins in a post-apocalyptic world in which nuclear radiation a) returned magic to the world and b) made penguins sentient and gave them mild tactile telekinesis, ie, the ability to manipulate (moderately lightweight) objects with their mind while physically touching them (to avoid issues like 'no thumbs' and 'average penguin is about 3ft tall and minimal strength'.)

So I'll share my list of species correlations instead, including reasoning:

Great Penguins

Emperor - BIG BOYS (36-37kg), no nests - Goliath

King - lorge (15ish kg), chicks grow slowly, yellow feather “crown”, deep divers, common - Minotaur

Brush-Tailed Penguins

Adelie- medium (5ish kg), particularly cold-resistant, line nests with stones, common - Elf

Chinstrap - 5ish kg, pretty (says this site), nest on slopes, common - Half-elf

Gentoo - standardish penguins? 5+a bit kg, Antarctic continent + islands, like crab, common - Human

Little Penguins

Little - SMOLEST CHILDES (1ish kg), nocturnal, common - Svartniblin

Fairy - ditto smol and habitat?? - Gnome

Banded Penguins

Galapagos - smol! (2ish kg), equatorial (very good in heat) - Halfling

African - 3ish kg, burrow much, used to warmer (African) weather - Dwarrow-Dwarf

Humboldt - 5-a bit kg, burrow some, occupy cold Peruvian current but hot (desert/Mediterranean) breeding site. Fucked by El Nino some years - Mountain Dwarf

Magellanic - 5-a bit kg, burrow breeders, ~ African but South American - Hill Dwarf

Large Divers

Yellow-eyed - 5.5ish kg, maybe rarest penguin, nest in plants - Aasimar

[EXTINCT] Waitaha

Crested Penguins

Rockhopper (Southern, Eastern, Northern) - 2.5ish kg, red eyes, tiny but fierce - Goblin

Snares - 3ish kg, endemic to Snares Islands, kill forest with guano quantity, yellow eyebrows - Hobgoblin

Fiordland - 4ish kg, endemic to New Zealand rainforests - Half-orc

Macaroni - 5+a bit kg, don’t Land much when not breeding, weird orange hair - Kobold

Erect-crested - 5ish kg, tall crests (~horns!) - Tiefling

Royal - 5+a bit kg, related to Macaroni probably (yellow hair), nest in open. Standardish - Dragonborn

[EXTINCT] Chatham

Humans = giants, 1 enclave per type

Other birds (terns, mostly? not albatross? Must really live there) arakockra

Genasi may be done as a half-heritage thing, ie, half genasi, half established race

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chatham albatross (Thalassarche eremita)

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

hi we have never met but ur coming to nz so birds right. kiwi is a classic but i guarantee you will love piwakawaka/fantail they are so friendly. ur most likely to see them on bushwalks cause they like to follow u around since you kick up the dirt so they can eat the bugs and stuff underneath

the humble kereru/wood pigeon is also very cute in my opinion i do love them and they’re pretty common like piwakawaka

keas!! very mischievous. like to steal peoples food/windshield wipers so watch out lol. very cool birds i think they’re becoming more common in auckland now which is cool

pukeko, funky little guys. mostly blue with long legs, you might see them by the road out of town or in wetland. my cousin had one when she worked for the spca and it was chill with us we could feed it but it could be aggro around other people. idk if that applies to all pukeko though that’s just my experience

takahe, pukeko’s bigger friend. basically same thing, but rounder (idk if they’re actually related but they look similar at least)

kākāpō, big green flightless babies. i love them so much i have a plush toy of one his name is gerald

kakaruia/black robin, ur not gonna see one of these unless you go to the chatham islands but they’re worth mentioning cause they’re very cute and i had a book about one as a kid (old blue) and because this is My list and i do what i want

waxeyes, common garden birds and very pretty and cute we get them in our feijoa trees i love them

lesser short-tailed bat because if bird of the year can include them so can i dammit. bats!! never seen one personally but they look like funky little guys. we also have the long tailed bat

tuis how have i not mentioned tuis yet. i love them so much my dads ringtone is a tui. you’ll be walking past a kōwhai tree or something and someone will go “look a tui” or “i hear a tui” and you all just stand there staring at it for a bit. beautiful

we also have penguins but to be honest with u i need to get out of bed so. perhaps i will return later with more fun facts for u also i am sorry if you already knew these things also forgive me for sending you an ask literally Out of the blue lmao i saw the neil gaiman ask and thought my country????? must inform them of things

Oh my god this is so nice?? Thank you so so much <33 Please come back with more fun facts about birds!!

I knew about some of them, but not all, so this is super interesting- I love birds and particularly water birds (I’m also super excited to finally see some albatrosses since we don’t have them in europe and they’re one of my favourite birds)

Also i can’t believe piwakawakas like to follow people? that’s so wild to me all birds i’ve ever met are shy to humans and even the ones that are not (eg pigeons and seagulls) still keep their distance, especially in the villages im from

I can’t wait to hear a tui ahhh <3

0 notes

Photo

Chatham Mollymawk / Chatham Albatross (Thalassarche eremita) - photo by linrod

88 notes

·

View notes

Photo

February 14, 2017 - Chatham Albatross, Chatham Mollymawk, or Chatham Islands Mollymawk (Thalassarche eremita)

These albatrosses are found in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and the west coast of South America. Their diet includes fish, krill, barnacles, and cephalopods. A pelagic species, they spend the majority of their time at sea, only returning to land to breed. They breed on an island known as the Pyramid, located at the southern end of the Chatham Islands. Nests are tightly packed on the steep cliffs of the island. These cliffs allow the nests to be accessed from the air and easily defended from predators. Like other albatross species, they are monogamous and share in incubation and care of the chicks. They are classified as Vulnerable by the IUCN because of their small breeding range, despite their apparently stable population.

Happy Valentine’s Day!

#chatham albatross#albatross#chatham mollymawk#thalassarche eremita#bird#birds#illustration#art#water#holiday#valentines day#birblr art

70 notes

·

View notes

Video

undefined

tumblr

natgeo In Jan 2018 National Geographic Photographer @thomaspeschakreached and photographed Te Tara Koi Koia, an imposing pyramid shaped rocky island at the southern edge of New Zealand’s remote Chatham Islands. This is the only nesting site of the vulnerable Chatham albatross ( @chatham_taiko_trust) and lies exposed to the wild moods of the tempestuous southern Ocean. Landing on and climbing Te Tara Koi Koia is only possible a handful of times per year and it took 27 days of waiting until a gap in the weather appeared. With the help of many Chatham Islanders @thomaspeschakwas finally able to photograph this near mythical albatross nesting ground for ‘Lost at Sea’ a story published in the July 2018 issue of National Geographic Magazine. Thank you to the traditional owners for granting access and @ottowhiteheadfor shooting and editing the video. The @chatham_taiko_trustis a pioneering grassroots conservation organization and this story would not have been possible without their support and guidance. Please follow @chatham_taiko_trustto find out more about this wild and iconic place at the edge of the world.

#New zealand#geology#island#te tara koi koia#pyramid#chatham islands#nature#albatross#travel#landscape#video#instagram#science#the earth story#national geographic

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

I've heard that Sphenisciformes (a.k.a Penguins) could've originated as far back as the Cretaceous Period? Is there any evidence to support this theory or is this pure speculation? When (in terms of geological age) and where were the first sphenisciformes discovered?

Oh boy. This touches on one of the most controversial subjects surrounding the origin of modern birds, so I’ll try my best not to make this answer overly complicated.

Let’s start with the easy part: the oldest known penguin fossils come from the Paleocene of New Zealand and are about 60–62.5 million years old. In the late 2000s, some news reports stated that the penguin fossils specifically from the Takatika Grit of the Chatham Islands were Cretaceous in age. More recent studies, however, have concluded that though there are some reworked Cretaceous fossils in the Takatika Grit, the rocks themselves formed entirely within the Paleocene, so there’s no particular reason to think that those penguin fossils were deposited in the Cretaceous.

Of course, the fossil record is patchy, so it’s almost never safe to assume that the oldest representatives that we’ve found of a lineage were the oldest members of that lineage ever. Through the 2000s, there were a few reasons why it was thought that penguins might have originated as far back as the Cretaceous, despite the lack of direct fossil evidence.

Firstly, a number of fragmentary fossils from the Late Cretaceous had been identified as belonging to members of specific neoavian groups, including shorebirds, loons, petrels, cormorants, and even parrots. If all of those groups really had originated in the Late Cretaceous, then it didn’t seem so farfetched that penguins might have already appeared then as well.

Secondly, a lot of early molecular clock analyses also seemed to support an extensive diversification of modern-type birds during the Cretaceous. In simple terms, molecular clock analyses compare the differences among the molecular sequences of different organisms and use estimated mutation rates to approximate the amount of time that has passed since their lineages diverged. Several early molecular clock analyses of birds estimated the origins of many modern bird lineages, including penguins, as Cretaceous in age.

However, the results of molecular clock studies are highly sensitive to prior assumptions that are included in the analyses. We already know that molecular mutation rates don’t remain constant over time, so these analyses need to allow for a plausible range of variation in mutation rates for the results to be credible. In addition, other sources of data (usually fossils) are typically used to calibrate these rates. For example, if we were running a molecular clock analysis estimating the age of penguins, we’d tell the analysis that penguins split from their closest living relatives at least 60–62.5 million years ago, because that’s how old their oldest known fossils are.

As you might imagine, the choice of which fossils to use as calibrations can make a big difference to the results of molecular clock analyses. If a fossil used to calibrate the age of a specific lineage is not actually a member of that lineage, then that can easily produce a misleading estimate. This was a fairly common problem with those early molecular clock estimates for modern birds.

For example, a few analyses used some of those aforementioned supposed Late Cretaceous neoavian fossils as calibrations. However, the truth is that essentially all of those specimens are too incomplete for us to really be sure that they are neoavian fossils. By using them as calibrations, some of those analyses placed the origin of specific neoavian groups in the Cretaceous by default, even though the grounds for doing so were not particularly strong, to say the least.

As it turns out, more recent molecular clock analyses that allow for plausible rate variation and use only well-supported fossil calibrations tend to find that most if not all modern neoavian lineages originated in the Cenozoic, shortly after the Cretaceous mass extinction.

Even so, some paleontologists still think that it is plausible penguins originated in the Cretaceous, and you can find very recent papers that argue for this (including one I linked earlier in this post). Their main arguments are based on the fact that multiple penguin species have been found at the sites that produced the oldest known penguin fossils, and the fact that these fossil penguins are recognizably very different from the closest living relatives of penguins, the procellariiform birds (albatrosses, petrels, etc.). According to these researchers, the amount of time between the Cretaceous mass extinction and the occurrence of these fossils doesn’t seem long enough for such extensive diversification and evolution to have occurred.

If you ask me, however, I personally find the idea that most neoavian lineages originated in the Cenozoic to be more consistent with the available evidence. For starters, though the fossil record is incomplete, I don’t think the absence of unambiguous Cretaceous neoavian fossils should be ignored. Based on the phylogenetic relationships among modern birds, if there were Cretaceous penguins, we’d not only be missing Cretaceous fossils of one or two bird lineages. In addition to penguins, we’d also be missing Cretaceous representatives of at least the lineage that gave rise to procellariiforms, the lineage that gave rise to pelecanimorphs (pelicans, herons, cormorants, etc.), the lineage that gave rise to loons, the lineage that gave rise to phaethontimorphs (tropicbirds, sunbitterns, etc.), and around 4–5 other neoavian lineages. That’s at least 9–10 groups that we lack any clear evidence of, even though we know of end-Cretaceous sites that preserve fossils of birds and their close relatives.

Furthermore, I don’t consider the short time frame between the end-Cretaceous mass extinction and the oldest known penguins to be all that problematic. 3.5 million years may be very short from a geologic perspective, but it’s a very long time in absolute terms. To be sure, giving rise to most of the major neoavian groups in such a time frame would still require very fast rates of evolution; however, we know that evolution can happen extremely quickly under the right circumstances. Consider how wall lizards transplanted to an island without native lizard species have been documented evolving herbivorous specializations in a matter of decades, or how the cichlids of Lake Victoria diversified into about 500 species in just 15,000 years. One of the conditions that probably promotes such rapid evolution is the availability of ecological opportunities... which the nearly empty world following a mass extinction would likely have a lot of.

In fact, there is more than just circumstantial evidence that this happened in neoavians. Regardless of when neoavians originated, all recent molecular clock estimates suggest that diversification happened extremely quickly at the base of Neoaves, which is probably one reason why their phylogenetic relationships have been so difficult to tease out. If modern neoavians originated in the Cretaceous, we don’t know of any obvious driver that could have caused such a rapid diversification, but it would make a lot of sense if it happened right after the Cretaceous mass extinction.

To be clear, none of this demonstrates that modern neoavians only originated after the Cretaceous. Maybe the fossil record really is so fickle that we’ve missed nine groups of end-Cretaceous birds, maybe some of those fragmentary fossils really are neoavians and we can’t tell, and maybe there was some unidentified major Late Cretaceous event that could have prompted a huge neoavian diversification. There’s a lot we don’t know about the ancient past, and it would take only one solidly identified Cretaceous neoavian fossil to prove me wrong! For the time being though, I think a post-Cretaceous origin of most if not all neoavian groups is more consistent with what we do know about the fossil record, evolutionary rates, and molecular evolution in birds.

For a more detailed overview regarding the controversies and challenges surrounding the timing of modern bird origins, I recommend this recent paper co-authored by my supervisor, Daniel Field. And if you’re not tired yet of hearing from me about this subject, I elaborated on many of the concepts I discussed here in the first episode of my podcast series on bird evolution.

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Albatross Cave by Thomas P Peschak

The large cave on the side of Te Tara Koi Koia shelters the eggs and chicks of Chatham albatrosses until the young are ready to fly. The island is the only place in the world where they breed naturally, making Thomas one of the privileged few to have witnessed and captured this moment.

Having a single breeding ground means that the future of Chatham albatrosses is insecure. Since the 1980s extreme storms have eroded the soil on Te Tara Koi Koia and destroyed vegetation crucial to nest-building. Conservationists recently translocated a new breeding colony onto the largest of the Chatham Islands to improve their chance of survival.

39 notes

·

View notes

Photo

It’s easy to launch when there are winds racing up the cliffs! Just open your wings and go... Today I’m winging my way to the Chathams to help out with a seabird translocation project! I’m gone for around ten days, with no phone and no internet. Enjoy these beautiful light-mantled albatross while I’m gone. Enderby Island #birdventurenz #subantarctic #expeditionguide #newzealand #birdventure #aotearoa #newzealand #seabird #albatross #seabirdstory #seabirdbiologist #biologistlife #wildsouth #your_best_birds #nuts_about_birds #kings_birds #nzbirds #wildnz #subantarcticadventure #ocean #nikonnz #nikond500 #seabirdscience #wilderness #adventure #bird_lovers_daily #wanderwonder @nikonnz @heritageexpeditions #wildernessculture #conservationphotography #conservationphotographer https://www.instagram.com/p/B8R2ixFJOTF/?igshid=1jet742wr0v7g

#birdventurenz#subantarctic#expeditionguide#newzealand#birdventure#aotearoa#seabird#albatross#seabirdstory#seabirdbiologist#biologistlife#wildsouth#your_best_birds#nuts_about_birds#kings_birds#nzbirds#wildnz#subantarcticadventure#ocean#nikonnz#nikond500#seabirdscience#wilderness#adventure#bird_lovers_daily#wanderwonder#wildernessculture#conservationphotography#conservationphotographer

37 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Admits Housebreaking and Theft Here; Given Sentence of Five Years,” The Porcupine Advance (Timmins). January 11, 1940. Page 03.

----

Admits ‘Long, Miserable’ Criminal Record in Police Court, Examination Shows Record Extends Back to 1920. Pleads Guilty to Two Charges of Breaking and Entering in Timmins and Two Charges of Theft

----

Five years in Kingston Penitentiary was the sentence imposed yesterday morning on Carl St. Regis after he pleaded guilty to four charges of breaking and entering and theft. St. Regis pleaded guilty to the charges in police court on Tuesday but sentence was remanded until Wednesday so that the Magistrate would have an opportunity to examine St. Regis’ record.

The record was illustrative of St. Regis’ admission in court to the effect that he was a habitual criminal. It showed that he was first apprehended in Fort Wayne, Indiana, as a suspect in 1920. In 1922 he was sent to jail for a period from three to fifteen years for breaking and entering; in 1923, he escaped from Michigan State Reformatory, and in 1923 was sentenced to three years for housebreaking and theft at London, Ontario. In 1926 he was returned to Michigan State Reformatory. In 1929 he was sentenced to three years in Toronto for housebreaking and theft and in the same year received a three year term at Guelph for burglary. Two years in Leavenworth Penitentiary was the sentence in 1934 for violation of Immigration Laws. In 1937 at Chatham 3 months for theft and the same sentence in 1938 at Welland.

St. Regis pleaded guilty to four charges here. The first was that he broke and entered the home of John F. McNeil, and stole there from a radio, a suitcase and shoes. Second was that he broke and entered the home of Kelly Abrams and stole a combination radio-victrola worth $102. He pleaded guilty to the theft of an electric drill from Marshall-Ecclestone’s store and the theft of a tool chest, containing tools valued at $100 from Antoine Vachon.

Asked if he had been previously convicted, St. Regis said, ‘Yes your worship, I have a long and miserable record. I have made a long struggle since I left Burwash in April and have tried to go straight. I did 17 days’ work for the Chief of Police at Sault Ste. Marie and I got a job in a mine for a while. I probably wouldn’t be here now expect that I did a re-decorating job for a man in Timmins and only got $7 of the total bill for $67. He wouldn’t pay me the money he owed me.’

After hearing St. Regis Magistrate Atkinson remanded sentence until Wednesday morning in order to be able to examine the man’s court record.

[AL: A typical member of the so-called ‘criminal class’ - a persistent offender who was rarely out of prison and whose record served as an albatross around his neck. St. Regis was convict #6061, worked mostly in the blacksmith shop at Kingston penitentiary this sentence, and was released in 1944 - he soon committed another theft and was returned for two years between 1946-1948.]

#timmins#housebreaking#housebreaker#theft#stolen radio#stolen record player#ex-convict#jailbird#long criminal record#habitual criminal#sentenced to the penitentiary#kingston penitentiary#great depression in canada#sault ste. marie#chatham#london ontario#border crossings#crime and punishment in canada#history of crime and punishment in canada#burwash industrial farm#northern ontario

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“The Chatham albatross only breeds on a large rock stack on the Chatham Islands in New Zealand called The Pyramid. Masters of flying at speeds well over 50mph, they are capable of crossing large distances without flapping their wings.”

quote and pic from https://www.instagram.com/bbcearth/

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

When penguins ruled after dinosaurs died

https://sciencespies.com/biology/when-penguins-ruled-after-dinosaurs-died/

When penguins ruled after dinosaurs died

Illustration of the newly described Kupoupou stilwelli by Jacob Blokland, Flinders University. Credit: Jacob Blokland, Flinders University

What waddled on land but swam supremely in subtropical seas more than 60 million years ago, after the dinosaurs were wiped out on sea and land?

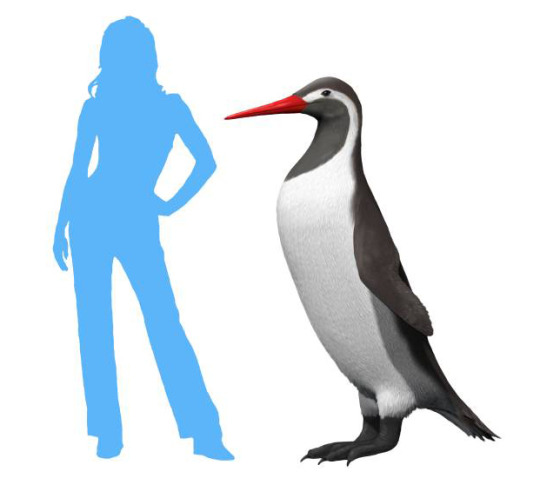

Fossil records show giant human-sized penguins flew through Southern Hemisphere waters—along side smaller forms, similar in size to some species that live in Antarctica today.

Now the newly described Kupoupou stilwelli has been found on the geographically remote Chatham Islands in the southern Pacific near New Zealand’s South Island. It appears to be the oldest penguin known with proportions close to its modern relatives.

It lived between 62.5 million and 60 million years ago at a time when there was no ice cap at the South Pole and the seas around New Zealand were tropical or subtropical.

Flinders University Ph.D. palaeontology candidate and University of Canterbury graduate Jacob Blokland made the discovery after studying fossil skeletons collected from Chatham Island between 2006 and 2011.

He helped build a picture of an ancient penguin that bridges a gap between extinct giant penguins and their modern relatives.

“Next to its colossal human-sized cousins, including the recently described monster penguin Crossvallia waiparensis, Kupoupou was comparatively small—no bigger than modern King Penguins which stand just under 1.1 metres tall,” says Mr Blokland, who worked with Professor Paul Scofield and Associate Professor Catherine Reid, as well as Flinders palaeontologist Associate Professor Trevor Worthy on the discovery.

“Kupoupou also had proportionally shorter legs than some other early fossil penguins. In this respect, it was more like the penguins of today, meaning it would have waddled on land.

“This penguin is the first that has modern proportions both in terms of its size and in its hind limb and foot bones (the tarsometatarsus) or foot shape.”

As published in the US journal Palaeontologica Electronica, the animal’s scientific name acknowledges the Indigenous Moriori people of the Chatham Island (Rēkohu), with Kupoupou meaning ‘diving bird’ in Te Re Moriori.

The discovery may even link the origins of penguins themselves to the eastern region of New Zealand—from the Chatham Island archipelago to the eastern coast of the South Island, where other most ancient penguin fossils have been found, 800km away.

University of Canterbury adjunct Professor Scofield, Senior Curator of Natural History at the Canterbury Museum in Christchurch, says the paper provides further support for the theory that penguins rapidly evolved shortly after the period when dinosaurs still walked the land and giant marine reptiles swam in the sea.

“We think it’s likely that the ancestors of penguins diverged from the lineage leading to their closest living relatives—such as albatross and petrels—during the Late Cretaceous period, and then many different species sprang up after the dinosaurs were wiped out,” Professor Scofield says

“It’s not impossible that penguins lost the ability to fly and gained the ability to swim after the extinction event of 66 million years ago, implying the birds underwent huge changes in a very short time. If we ever find a penguin fossil from the Cretaceous period, we’ll know for sure.”

Explore further

Scientists say monster penguin once swam New Zealand oceans

More information:

Chatham Island Paleocene fossils provide insight into the palaeobiology, evolution, and diversity of early penguins (Aves, Sphenisciformes) , Palaeontologia Electronica 22.3.78 1-92 doi.org/10.26879/1009

Provided by

Flinders University

Citation:

When penguins ruled after dinosaurs died (2019, December 9)

retrieved 10 December 2019

from https://phys.org/news/2019-12-penguins-dinosaurs-died.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

#Biology

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Earth' Our home too : Albatross

‘Earth’ Our home too : Albatross

Albatrosses are large seabirds in the family Diomedeidae. They are related to the procellariids, storm petrels, and diving petrels in the order Procellariiformes (the tubenoses). They range widely in the Southern Ocean and the North Pacific. Albatrosses are among the largest of flying birds, and species of the genus Diomedea (great albatrosses) have the longest wingspans of any extantbirds,…

View On WordPress

#Albatross#Amsterdam albatross#Antipodean albatross#Atlantic yellow-nosed albatross#Birds#Black-browed albatross#Black-footed albatross#Buller&039;s albatross#Campbell albatross#Chatham albatross#Ecological preservation#endangered species#Facts & Stats#Grey-headed albatross#Indian yellow-nosed albatross#Laysan albatross#Light-mantled albatross#Northern royal albatross#Ocean Birds#Salvin&039;s albatross#save birds#Short-tailed albatross#Shy albatross#Sooty albatross#Southern royal albatross#Tristan albatross#Useful information#Wandering albatross#Waved albatross#White-capped albatross

0 notes