#Caribbean heritage and traditions

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Discovering the Enchantment of Trinidad and Tobago: A Fairy Tale Island Getaway

Nestled in the southern Caribbean, Trinidad and Tobago is a mesmerizing dual-island nation that feels like it has sprung straight from the pages of a fairy tale. With lush landscapes, vibrant culture, and endless activities, it’s no wonder that this island paradise has become one of the top destinations for vacationers seeking both adventure and relaxation. Whether you’re drawn by the natural…

View On WordPress

#authoralchilders#authoraudreychilders#authorchilders#BestOfTrinidad#CaribbeanAdventures#CaribbeanCulture#CaribbeanHeritage#CaribbeanTravel#CarnivalTrinidad#ColonialHistory#DiscoverTrinidad#ExploreCaribbean#ExploreTobago#IndigenousHistory#IslandHistory#IslandParadise#TobagoBeaches#TravelTobago#TrinidadAndTobago#TrinidadAndTobagoTourism#TrinidadIndependence#TrinidadVacation#VisitCaribbean#Arawak and Carib peoples#Best beaches in Trinidad#Best things to do in Trinidad#British rule Trinidad#Caribbean adventure travel#Caribbean heritage and traditions#Caribbean indigenous history

1 note

·

View note

Text

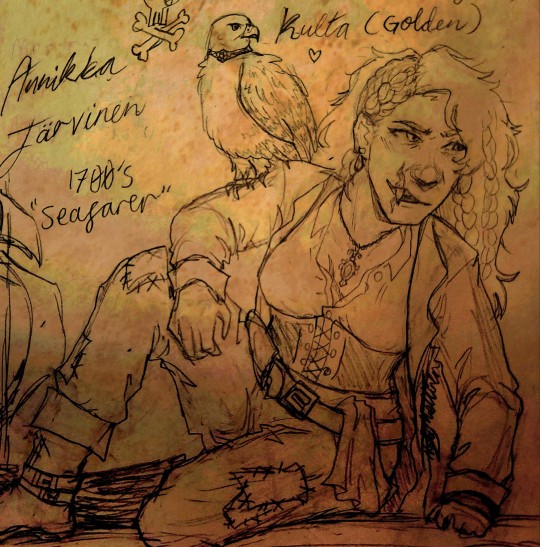

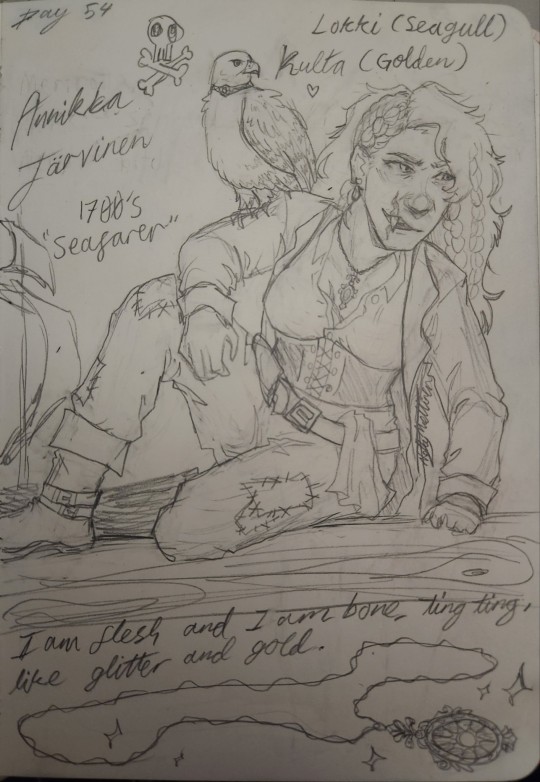

#my art <3#art#sketch#traditional art#oc art#oc artist#pirates#pirate oc#era oc#sea of thieves oc#sea of thieves#pirates of the caribbean#pirates of the caribbean oc#small artist#artists on tumblr#gyrfalcon#finnish heritage

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

#music#caribbean music#haitian music#tradition#heritage#troubadour#putumayo#world music#canadian folk music#caraibes#global music#traditional music#patrimoine#culture

0 notes

Text

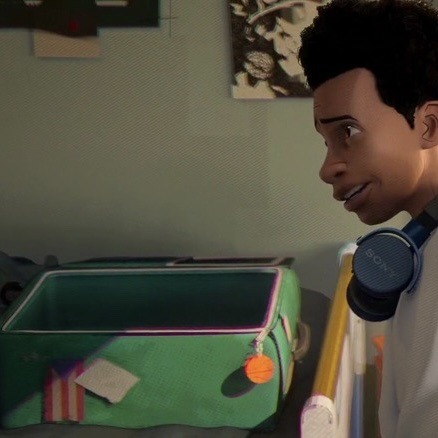

more insight on miles’ puerto rican heritage for your fics or fanart

- traditional quinceañeras (or as they are often called by puerto ricans quinceañeros) are really not that common anymore, most girls nowadays have pool parties or go on a cruise. if miles were to go to one of his cousins’ 15 birthday party, chances are it would be casual— no big poofy dress (his mom probably had one like that though)

edit: some people disagree on this. depends on how traditional your family and friend group is I guess, as well as which part of the island you’re from. on average, it seems to be a far bigger deal amongst some other latines. in my class in pr only 3 out of approx 30 girls had a big event like that. not a single one of my cousins had a traditional quince either so you could say I’m partly biased bc of my own experiences. i personally just had a big pool party

- plantains are a big part of our diet. also, pr being an island in the caribbean, coconut is in a lot of our desserts. if miles had to pick a favorite fruit I hc he’d pick either one of the two lol also please google our food, our food isn’t actually spicy so much as savory

- we “celebrate” thanksgiving like other americans. it’s about the only time we eat oven roasted turkey. for winter holidays (christmas eve/day, new years eve/day, three kings day/eve) oven roasted pork. chicken might be offered as a second option for people who don’t consume pork for whatever reason

- you’re pretty much taught how to dance as soon as you can walk. most of us have basic rhythms down. chances of miles dancing with his mom or friends at parties? astronomically high.

- the reason why our flag is everywhere, besides pride, is ‘cause it was illegal to own it. look up the gag law that prohibited us from even displaying it at our homes. so it’s actually an awesome detail in these movies

- this is my opinion/a fun fact but I feel like miles is basically an homage to black and puerto rican (specifically nuyorican) solidarity around the 70s-80s during the creation of hip-hop and rise of graffiti as a form of expression (you can easily read up on this or watch shows like the get down to learn more about this if you’re curious)

- whether you’re “nuyorican” or “from the island” spanglish is common so miles’ mixing english and spanish isn’t odd bc even rio does this as miles points out in the party scene. he isn’t a “no sabo” kid so much as someone with a strong accent. he understands his mom perfectly

- race ≠ ethnicity. there are plenty of black people in and from Puerto Rico, and miles’ pr family in the spiderverse films are designed to be for the most part afro-latine. so I wouldn’t really call him biracial

- the puerto rican day parade wouldn’t be a thing he skips, he’s gifted a special suit for it in a comic run. his puerto rican heritage is important to him!

#if you’re writing and need cultural insight i don’t mind messages hhhhh#what he represents matters a lot to me#spiderverse#miles molares#spiderman#punkflower#gwiles#flowerbyte

5K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hoiiiii

I was wondering if you could make a Ot8 reaction where ateez has a Caribbean so/

Being caribbean myself it would be interesting to see how it would play out. You don't have to do it if you don't want to but if you do thank you so much

-🌥 xoxo

ATEEZ REACTIONS: DATING A CARIBBEAN S/O

(aka: how I think ATEEZ would vibe with a Caribbean partner)

pairing ✭ ateez x caribbean!reader

tags under

dating, cultural appreciation, playful teasing, possessiveness, language exchange, endless warmth, respect, food sharing, and more

author's note: sooo, I wasn’t entirely sure what direction you were imagining for this, buuut I gave it my best shot! hope it is something like what you had in mind 😊

✨ Requests OPEN! ✨ Feel free to ask for more or send requests through the “Ask” button—if I can write it, you’ll see it here!

navigation

𓄹 ࣪˖ 🪸 𓏲 ๋࣭ . ⁎⁺˳ 𖥦 ˑ ֗ ִ˓𓄹 ࣪˖ 🪸 𓏲 ๋࣭ . . ⁎⁺˳ 𖥦 ˑ ֗ ִ ˖ 🪸 𓏲 ๋࣭ . . ⁎⁺˳ 𖥦 ˑ ֗ ִ˓𓄹 ࣪˖ 🪸 𓏲 ๋࣭ .

hongjoong:

Hongjoong is captivated by your heritage, always wanting to know more about your culture's music, art, and language. He surprises you with playlists of Caribbean beats he’s discovered, weaving elements into his own music. When you two go out, he’s possessive but in the best way, keeping you close. He’s your shield, always watching to make sure you’re comfortable, especially in new settings. If someone stares a little too long, Hongjoong subtly pulls you closer, a quiet reminder of his unwavering devotion.

seonghwa:

Seonghwa adores your vibrant Caribbean energy and compliments your every expression and movement. He’s the type to hold your hand at festivals, taking in every detail with you and admiring the cultural experiences you share. He’s also got a playful side, always ready to dance with you, whether at home or at a Caribbean festival. His favorite thing? Seeing your face light up with joy, which he does everything in his power to bring out, whether through gifts, surprises, or his signature, heartfelt compliments.

yunho:

Yunho’s fascination with your culture goes beyond the surface—he’s genuinely interested in understanding the foods, language, and traditions. Every time you mention a new dish, he’s already texting you asking when you can cook together. He tries his best to replicate the dance moves you teach him, even if he’s hilariously off-rhythm. His enthusiasm is infectious, and he’s always eager to learn more, even though he may need a little help with pronunciation. He loves making you laugh, and every failed attempt only brings you two closer.

yeosang:

Yeosang shows his love quietly but deeply. Though he may not be outwardly expressive, he surprises you with thoughtful gestures that prove he’s always paying attention. He buys you your favorite snacks or researches traditions to understand your culture better. He loves sitting by your side while you talk about your childhood memories, nodding thoughtfully, his gaze warm and supportive. Yeosang values your roots as an extension of who you are, always making sure you know he’s there, sharing in your world.

san:

San is all about making you feel like the only person in the world. His hugs are frequent, tight, and full of affection, grounding you in a way only he can. San loves to show his appreciation physically and emotionally, often pulling you into impromptu dance-offs inspired by Caribbean music. He’s always by your side, hyping you up no matter what you do. He adores seeing you in cultural outfits, showering you with praise and affection. “You’re a goddess, you know that?” he whispers, his eyes lighting up at your every smile.

mingi:

Mingi’s curiosity about your Caribbean culture knows no bounds. He’s constantly cracking jokes and mimicking accents in an endearing, if not always accurate, way. His playful energy brings out the best in you, always inviting you to laugh with him. He’ll try every new dish you mention, no questions asked, and loves teasing you about how spicy your food can be. When you introduce him to music from your culture, he’s quick to memorize the words and sing along, even if his pronunciation makes you both double over in laughter.

wooyoung:

Wooyoung’s energy pairs perfectly with your vibrant Caribbean roots, and he’s often found coordinating dance parties or events that showcase your culture. He’ll surprise you with little things, like learning to cook your favorite dish or organizing a beach day to remind you of home. He’s unapologetically proud to have you by his side, hyping you up to friends, and adoring the way you bring warmth to his world. Wooyoung’s love language is one of celebration, and he ensures every moment you’re together feels like a festive memory.

jongho:

Jongho is endlessly respectful of your culture, quietly taking in every story you tell about your heritage. His admiration shows through his actions, whether it’s patiently learning the phrases you teach him or sitting through dance practices just to see you shine. He might not be the loudest, but he’s got a quiet strength that reassures you he’s always there. Jongho makes you feel safe and seen, his loyalty unwavering, often reminding you just how important your culture is to him as it is to you.

#ateez#ateez fanfic#ateez fic#ateez imagines#kpop#atz#ateez reactions#ateez requests#ateez reading#caribbean#caribbean reader#ateez fluff#hongjoong#seonghwa#yunho#yeosang#san#mingi#wooyoung#jongho

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Battle of Colors - Barranquilla, Colombia – February 2006

The Carnival of Barranquilla is a unique festivity which takes place every year during February or March on the Caribbean coast of Colombia. Cumbia, both music and dance, is considered to be the main essence of the Carnival. A colourful mixture of the ancient African tribal dances and the Spanish music influence – cumbia, porro, mapale, puya, congo among others – hit for five days nearly all central streets of Barranquilla, the capital of the Atlántico Department. Those traditions kept for centuries by Black African slaves have had the great impact on Colombian culture and Colombian society. In November 2003 the Carnival of Barranquilla was proclaimed as the Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.

#The Battle of Colors#Barranquilla#Colombia#Carnival of Barranquilla#February#March#Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO#History#Culture#Afro Colombians

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

🍲Black food history

:1. Fried Chicken: Originated in West Africa, brought to Americas by enslaved people

.2. Gumbo: African, French, and Indigenous fusion dish from Louisiana.

Barbecue: African and European influences merged in Southern BBQ.

Soul Food: Post-Civil War cuisine developed by African American women.

Juneteenth: Celebratory foods like red velvet cake, strawberry soda.

African Diasporic Cuisines: Caribbean, Latin American, African American.

Foodways of Enslavement: Cooking techniques, ingredients.

Freedom Food: Post-Emancipation culinary innovations.

The Black Chef''s Movement: Modern culinary activism.

Black Food Culture Preservation: Efforts to document, celebrate heritage. 🍲Books:

"High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America" by Jessica B. Harris

"Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine" by Adrian Miller

"The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink" by Andrew F. Smith 🍲Documentaries:

"The Search for General Tso"

"Soul Food Junkies"

"The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross" 🍲African American culinary contributions are vast and diverse, reflecting the community''s rich cultural heritage. Here are some key aspects: 🍲Traditional Dishes

Fried Chicken

Barbecue (ribs, brisket, etc.)

Gumbo

Jambalaya

Soul Food (mac and cheese, collard greens, etc.)

Cornbread

Red Velvet Cake

Sweet Potato Pie 🍲Culinary Influences

African (fufu, jollof rice)

Caribbean (jerk seasoning, curry)

Southern American (biscuits and gravy)

European (French, Spanish, Italian) 🍲Historical Context

Slavery: Enslaved Africans brought culinary traditions.

Reconstruction: Freedmen established restaurants, food businesses.

Great Migration: African Americans introduced Southern cuisine to urban centers. 🍲Iconic Figures

Abby Fisher (first African American cookbook author)

Nat Fuller (renowned chef, Charleston)

Edna Lewis (celebrated chef, author)

Leah Chase (legendary New Orleans chef) 🍲Modern Contributions

Innovative chefs (e.g., Marcus Samuelsson, Carla Hall)

Food media (e.g., "Soul Food Junkies," "High on the Hog")

Food festivals (e.g., Essence Food Festival)

Food justice movements (e.g., Soul Fire Farm) 🍲Regional Cuisines

Southern (e.g., Lowcountry, Cajun)

Caribbean-American (e.g., Haitian, Jamaican)

West Coast (e.g., California soul food)

Midwestern (e.g., Detroit-style soul food) 🍲Books

"The Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink" by Andrew F. Smith

"Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine" by Adrian Miller

"High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America" by Jessica B. Harris 🍲Documentaries

"The Search for General Tso"

"Soul Food Junkies"

"The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross" 🍲Websites

The Southern Foodways Alliance

Black Food Studies

The Food and Culture Exchange

#Black history#black liberation#black community#black power#black people#black culture#black history 365#black history matters#black history is american history#black history is world history#black history month

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Identity, Heritage Monuments, Riohacha, Colombia: Sculpture by the artist Yino Marques, made of bronze, concrete and galvanized iron; It is an emblematic work in the municipality of Riohacha. With this majestic work called identity, it is possible to describe the tradition of the department of La Guajira, being today one of the main attractions of the first Avenue of South America. Identidad Monument, was erected in 2010... Riohacha is a city in the Riohacha Municipality in the northern Caribbean Region of Colombia. Wikipedia

#Identity#Heritage Monuments#Riohacha#Riohacha Municipality#Colombia#south america#south american continent

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

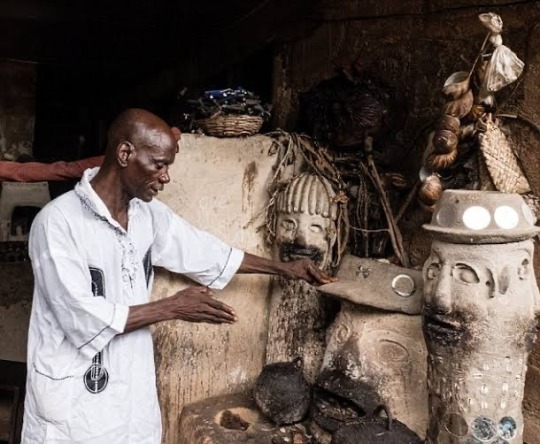

AFRICAN VOODOO

The deep truth about AFRICAN VOODOO

African Voodoo: Unraveling the Mysteries of a Rich Spiritual Tradition

African Voodoo, often shrouded in mystery and misconceptions, is a complex and fascinating spiritual tradition with deep-rooted cultural significance. This ancient belief system, practiced in various forms across the African continent and the African diaspora, offers a unique perspective on the relationship between humans, nature, and the divine. In this article, we will delve into the world of African Voodoo, exploring its history, beliefs, rituals, and its enduring impact on the cultures and societies where it thrives.

A Diverse Tradition

Voodoo, also spelled Vodou or Vodun, is not a monolithic belief system; rather, it is a diverse and adaptable spiritual tradition that has evolved differently in various regions of Africa and beyond. Its origins can be traced back to the indigenous religions of West and Central Africa, where it was practiced by different ethnic groups. Over time, African Voodoo underwent syncretism with Catholicism and indigenous beliefs in the Caribbean, particularly in Haiti, giving birth to Haitian Vodou, which is perhaps the most well-known form of Voodoo.

Core Beliefs

At its core, African Voodoo centers around the veneration of spirits, ancestors, and deities. These spirits are believed to have the power to influence human life and the natural world. Each spirit has a specific domain, and practitioners seek their guidance and assistance through various rituals and offerings. Ancestor worship is a fundamental aspect of Voodoo, as it connects the living to their familial lineage and heritage.

The Loa, or spirits, are a central focus of Voodoo ceremonies. These spirits are intermediaries between humans and the ultimate divine force. Practitioners often enter trance-like states to communicate with the Loa, who possess them temporarily during rituals. The Loa are known for their distinct personalities and preferences, and offerings such as food, drinks, and dance are made to appease and honor them.

Rituals and Practices

Voodoo rituals are colorful and lively events filled with drumming, dancing, singing, and the use of symbolic objects. Rituals are often held in temples or outdoor spaces, and they vary widely depending on the specific tradition and purpose. Some rituals are celebratory, while others are intended to seek protection, healing, or guidance.

One of the most famous Voodoo rituals is the "Voodoo Doll," which is often misunderstood. These dolls are not meant for causing harm but are used as tools for healing or connecting with a specific person's spirit. Pins may be used symbolically to focus intention.

Voodoo in the African Diaspora

The transatlantic slave trade played a significant role in spreading African Voodoo to the Americas, particularly in regions like Haiti, New Orleans, and Brazil. In these places, Voodoo underwent further syncretism with local beliefs and Catholicism, resulting in unique variations of the tradition.

Haitian Vodou, for instance, is a vibrant blend of African Voodoo, Catholicism, and indigenous Taino beliefs. It has had a profound impact on Haitian culture and played a central role in the struggle for independence from colonial rule.

Misconceptions and Stereotypes

African Voodoo has been the subject of many misconceptions and stereotypes, often portrayed negatively in popular culture. These portrayals frequently focus on the more sensational aspects of Voodoo, such as curses and zombies, rather than its rich cultural and spiritual dimensions. It's important to recognize that Voodoo is a legitimate religious practice for millions of people, and like any belief system, it encompasses a wide range of beliefs and practices.

African Voodoo is a complex, multifaceted spiritual tradition with a deep and enduring cultural significance. It is a testament to the resilience of African heritage and the ability of beliefs to adapt and evolve over time. Beyond the stereotypes and misconceptions, Voodoo represents a profound connection between humans, nature, and the divine—a connection that continues to shape the lives and cultures of those who practice it.

Communication with the spirits, often referred to as Loa or Lwa in Voodoo, is a central aspect of Voodoo rituals and practices. Here's an overview of how practitioners communicate with these entities:

1. **Rituals and Offerings**: Voodoo rituals are the primary means of communication with the spirits. Practitioners gather in a designated sacred space, such as a temple or outdoor altar. They often create an elaborate ritual environment with symbols, candles, and ceremonial objects. Offerings, including food, drinks, tobacco, and other items, are presented to specific spirits to gain their favor and attention.

2. **Dance and Music**: Music and dance are essential elements of Voodoo ceremonies. Drumming and chanting create a rhythmic and trance-inducing atmosphere. Through dance and music, practitioners enter altered states of consciousness, allowing them to connect with the spirits more profoundly. It is believed that the spirits may possess individuals during these ceremonies, providing a direct channel for communication.

3. **Possession and Trance**: One of the most distinctive aspects of Voodoo rituals is the concept of spirit possession. Practitioners, often referred to as "servants of the spirits," may enter a trance-like state during which a particular Loa or spirit is believed to take control of their body. In this state, the possessed individual may speak in the voice of the spirit, offering guidance, advice, or requests on behalf of the spirit.

4. **Divination**: Divination is another way to communicate with the spirits in Voodoo. Practitioners may use various divination tools such as tarot cards, cowrie shells, or casting of objects to seek guidance from the spirits. These divination practices help practitioners understand the desires and intentions of the spirits and may provide insights into their own lives.

5. **Prayer and Invocation**: Voodoo practitioners often use prayer and invocation to establish a connection with the spirits. Specific prayers or invocations are recited to call upon a particular spirit's presence and assistance. These prayers are typically passed down through generations and may be spoken in a specific language or dialect.

6. **Voodoo Dolls**: Contrary to popular misconceptions, Voodoo dolls are not used for causing harm but are symbolic tools for communication. They can represent a specific person or spirit and are employed in rituals to convey intentions, requests, or healing energy to the spirits associated with them.

It's important to note that communication with the spirits in Voodoo is a deeply spiritual and cultural practice, and the methods may vary among different Voodoo traditions and communities. Voodoo practitioners believe that these rituals and practices maintain a reciprocal relationship with the spirits, offering offerings and devotion in exchange for protection, guidance, and assistance in various aspects of life.

Masquerades and Voodoo in Africa: A Cultural Tapestry of Spiritual Expression

Africa is a continent rich in cultural diversity, and its spiritual practices are as varied as its landscapes. Among the many vibrant traditions that permeate African culture, masquerades and Voodoo (often spelled Vodun or Vodou) hold significant places in the hearts and lives of its people. This article explores the fascinating intersection of masquerades and Voodoo, shedding light on how these practices are intertwined with African spirituality.

**Masquerades: The Embodiment of Spirits**

Masquerades are a prominent cultural phenomenon across Africa, characterized by elaborate costumes, masks, and dances. These performances serve multifaceted purposes, including entertainment, social commentary, and spiritual expression. However, it's the latter aspect, the spiritual dimension, that ties masquerades to Voodoo and other indigenous African belief systems.

1. **Role of Ancestors**: In many African cultures, masquerades are a means of connecting with ancestors and spirits of the deceased. The masks and costumes worn by performers often represent these spirits. During masquerade ceremonies, participants believe that the spirits inhabit the masks and interact with the living. This interaction serves as a way to honor and seek guidance from the ancestors.

2. **Protection and Cleansing**: Some masquerades have protective roles in communities. They are believed to ward off evil spirits, illnesses, or other malevolent forces. These masquerades often perform purification rituals, symbolically cleansing the community and its members.

3. **Harvest and Fertility Celebrations**: Masquerades are frequently associated with agricultural and fertility rites. They may perform dances and rituals to ensure a bountiful harvest or to promote fertility among the community members.

4. **Social Order and Governance**: Masquerades also play a role in enforcing social norms and maintaining order within communities. They may act as judges, mediators, or enforcers of communal rules during their performances.

**Voodoo: The Spiritual Heartbeat**

Voodoo, a widely practiced religion across West Africa and its diaspora, is deeply entwined with masquerades and the spiritual fabric of the continent.

1. **Ancestor Worship**: Voodoo places a significant emphasis on ancestor worship, much like masquerades. Practitioners believe that the spirits of ancestors are ever-present and can influence the living. Offerings, rituals, and masquerade performances are ways to honor and seek the guidance of these spirits.

2. **Connection to Nature**: Voodoo, like many African belief systems, recognizes the close relationship between humans and nature. It views natural elements, such as rivers, forests, and animals, as inhabited by spirits. Masquerades often incorporate nature-centric symbolism in their performances.

3. **Trance and Possession**: Both Voodoo and certain masquerades involve altered states of consciousness. In Voodoo, devotees may enter trances and become possessed by spirits, similar to the possession experiences during some masquerade ceremonies. These states facilitate direct communication with the divine.

4. **Rituals and Sacrifices**: Offerings and sacrifices are common in both Voodoo and masquerade traditions. These rituals are believed to appease spirits and seek their favor.

**Cultural Resilience and Transformation**

While masquerades and Voodoo have endured the test of time and colonization, they have also adapted and evolved. In the African diaspora, especially in the Americas, they fused with other cultural elements and religions, giving rise to unique traditions such as Haitian Vodou and New Orleans Voodoo.

masquerades and Voodoo in Africa are vibrant expressions of spirituality, culture, and identity. They are living traditions that continue to shape the lives and beliefs of countless individuals and communities, offering insights into the enduring resilience and adaptability of African cultures in the face of change and adversity.

The timing for Voodoo practices, like many spiritual traditions, can vary depending on the specific tradition, the purpose of the practice, and the preferences of the practitioner. There is no universally "best" time for Voodoo practice, but certain times and occasions are commonly observed:

1. **Festival Days**: Many Voodoo traditions have specific festival days or holidays when practitioners gather to perform rituals and ceremonies. For example, in Haitian Vodou, the Festival of the Ancestors (Fèt Gede) is a significant event where people honor and communicate with their ancestors. These festivals often have fixed dates in the Voodoo calendar.

2. **Full Moon and New Moon**: Lunar phases are significant in various spiritual practices, including Voodoo. Some practitioners prefer to conduct rituals during the full moon or new moon, believing that these phases are particularly potent for spiritual work. The full moon is often associated with amplifying energy and intentions, while the new moon is seen as a time for new beginnings.

3. **Nighttime**: Many Voodoo rituals take place during the nighttime. This is believed to be a time when the veil between the spiritual and physical realms is thinner, making it easier to communicate with the spirits. Candlelit ceremonies, drumming, and dancing are common elements of Voodoo rituals conducted at night.

4. **Personal Preference**: Individual practitioners may have their own preferred times for Voodoo practice based on their personal experiences and beliefs. Some may feel a stronger connection to the spirits during specific times of the day or year.

5. **Life Events**: Voodoo is often integrated into various life events such as births, marriages, and funerals. The timing of these rituals is determined by the occurrence of these events.

6. **Consulting a Voodoo Priest/Priestess**: For more specific guidance on the timing of Voodoo practices, consulting a Voodoo priest or priestess is advisable. They can provide insights based on their knowledge and experience within their particular Voodoo tradition.

It's essential to remember that Voodoo is not a monolithic practice; it encompasses various traditions and regional variations, each with its own customs and beliefs. Therefore, the best time for Voodoo practice can differ significantly from one tradition to another. Additionally, Voodoo is deeply rooted in cultural and spiritual contexts, so practitioners often follow the customs passed down through generations within their specific communities.

#life#animals#culture#aesthetic#black history#history#blm blacklivesmatter#anime and manga#architecture#black community#heritagesites#culturaltours

267 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Gift

Story originally posted on Coiled Fist December 2011

_______________________________________________

Nick and Mark grew up together. They went to middle school, high school and were even roommates in college together. They had always been inseparable. Unfortunately as so often happens, life sent them their own separate ways after graduating college. Mark moved out East to work in New York while Nick had moved out West to LA. The two that used to spend every second of the day together were on opposite ends of the continent.

Every year for the Holidays, Mark and Nick would exchange stupid gag gifts to each other to keep things exciting. This year, even though there was distance between them, Nick wanted to continue this tradition. He had heard and advertisement for something on the scyfy channel that gave him a great idea.

Mark was an average build and height. At 23, he was not a muscle man, but not flabby either. He was about 5’10’’ with short, black hair, warm brown eyes and olive skin – you could definitely notice the slight Italian heritage in him. Nick, also 23, had a similar body build; only slightly more buff. He had spiked blonde hair and blue eyes like the ocean in the Caribbean.

The doorbell rang. Finally, Nicks surprise for Mark had arrived. At Nick’s feet at the front door was a tiny box, about the size of a ring box. In it was a single pill. Under it was a folded paper that said in small writing “Directions” and “Side Effects.” Out of excitement, Nick ignored the paper, tucked it in his pocket and snatched the pill out of the box with a smirk.

Everything was in place. On the ground at the front door was an empty box with the lid open with a label already secured on one side. There was packaging tape halfway across one of the top flaps with the other half waiting to seal the box shut. Nick grabbed a bag of candy that he had bought from some kid fundraising for something or other earlier in the week. It wasn’t a specific candy, just a bag with a couple pieces of chocolate that says in very vague wording “candy” on the bag.

“Well, I think that’s everything. Box is ready, I have the pill, food for the journey,” says nick while looking down at the candy in his hand. “Well, here goes nothing I guess,” Nick says sighing as he gulps the pill down in one swift move. The impact of the pill is immediate. Nicks head is spinning and already he is noticing the world around him slowly getting larger. When he gets to be about two feet tall, he steps into the box to finish his descent. When he is at equal height of the sides of the boxes, he reaches his arms up, grabs the flaps and pulls them down tightly, sealing the box with the extra tape. There is no going back now. Nick was trapped in a box, addressed to his best friend Mark in New York and there was no way out. Finally, Nick stopped his shrinking at about 2 inches tall. Almost immediately after the shrinking process ended, Nick felt the box being picked up by the postman, to take him off on his journey. There was nothing to do now but sit back and relax. Thankfully his box was marked as overnight so the trip won’t be a long one. Nick was tired anyway so he let himself drift off to sleep.

When Nick awoke, his muscles felt very stiff. He attributed it to the poor sleeping conditions in the box and brushed it off. Outside the box, he heard voices saying “THIS ONE HERE IS GOING TO MANHATTAN…THAT THERE IS HEADING TO BROOKLYN..” Nick knew that he must already be in New York. He was so excited he wanted to get up and see if he could catch a passing glimpse from a crack in the box. When he tried to get up though, his legs didn’t respond. Remembering the paper, and understandably panicking, Nick reached into his pocket to retrieve the paper that came with the pill. It read “Gradual shrinking Pill. Directions: take one pill orally. Effects wear off after one week’s time. SIDE EFFECTS: May cause dizziness, fatigue and temporary loss of all motor skills” Nick’s heart sank….does this mean that, for a period of time, he will not be able to move? He suddenly feels faint and realized he still hasn’t eaten. To try and calm himself, Nick lay’s back down and decides to eat his snack. He places the bag on his lap, finishes its contents and let’s himself drift slowly into sleep again.

He is suddenly jolted awake by a loud THUD and a knock on the door. There is a distant sound of voices that he can’t make out, and then his box is shifted again until it finally comes to rest once more. After a slight pause, a huge silver object pierces the seal of the tape and slides down allowing light to freely flow in. Almost unbelievably, he sees several HUGE finger tips squeeze into the opening and force the flaps open. After a brief burst of light that blinds him, Nick notices the face of his best friend Mark who is looking into the box curiously with a puzzled face. He must have just returned from the gym because he is wearing a sweat soaked t-shirt, mesh shorts and running shoes. His hair, though disheveled from sweat because of the workout, still fell perfectly over his forehead as if he had done it on purpose. Almost immediately, Mark’s face turned from puzzlement to joy and shock as he puts the pieces together.

“HOLY SHIT! Nick really out did himself this time! How did he even do this!? He sent an EXACT replica of himself in CANDY! That is the craziest shit I have ever seen!” Nick is confused. What is he talking about? Then it begins to make sense; The empty bag on his lap reading simply “candy,” his inability to move the slightest bit. What else was Mark to think? Nick thinks to himself that this has the potential to end very, very badly if he doesn’t think quickly. But what can he do?

Without giving him even a second to gather his thoughts, Mark’s massive hands are swooping in to grab Nick. Eight huge fingers slide under Nicks back and slowly lift him up. Marks skin is warm, soft and still moist from the workout. They smell like a mix of sweat and soap. Nick’s form is rolled down the fingers and into a waiting palm where the opposite hand proceeds to examine the treat. Beyond the hands, Mark’s face is held in a slight half smile. “Wow. I still can’t believe this. It looks so real! I wonder if it actually tastes any good.”

“No, No. Bad, bad, bad.” Nick thinks to himself. “I need to do something NOW!” But Mark isn’t waiting for Nick to formulate a plan. His lips are already being moistened by a protruding tongue and the lips are slowly parting. The hand holding Nick begins to raise up to meet the mouth. The lips open fully revealing a couple saliva strands connecting the pink tongue to the rigged roof of the mouth behind a perfect set of flawless, straight, white teeth. Mark’s breath surrounds Nick’s tiny form. It has a hint of the smell of Gatorade, no doubt from the workout as well. Without warning, the hand containing Nick begins to tilt towards the waiting mouth of Mark.

Helpless, Nick wants to kick and scream, but can’t even so much flinch a one bit. Nick slides down, head first towards Mark’s waiting and slightly extended tongue. Nick falls into the soft pink lip, continues over the lower row of teeth until finally coming to rest on Mark’s tongue. It softer than expected, warm and very moist. It wiggled a little under him as it began to taste the morsel. Nick’s legs are all that hang out of the mouth, but not for long. Mark’s lips close on the legs tightly. Suddenly, a loud slurping noise begins and the legs are slowly dragged into the darkness of the mouth with the rest of the body. As the back molars place themselves over Nick’s head, ready to give the killing blow, Nick regains all feeling in his body almost as if a switch had been flipped. As the molar begins to apply a little pressure, a loud, blood curdling scream is let out of Nicks Mouth. “NO! STOP! MARK STOP!” Nick cries. He kicks the tongue, punches the check. Does everything he can. Almost choking, Mark immediately spits out the contents of his mouth into his hand.

“What the…NICK!? FUCK, is this really YOU!?” Mark said astonished, looking like he is going to be sick.

“YES MARK! THANK GOD! IT’S ME!” Says Nick, coughing and trying to catch his breath. Nick proceeded to tell Mark the entire story.

“Dude…I…I almost ATE YOU MAN! What the hell is wrong with you!?”

“I don’t know, I thought this would be a cool idea to keep up with our gift exchange…”

“Well, it sure IS neat. I’m sorry I yelled. I just, I was worried that’s all. Whew. Can you imagine if I ACTUALLY ate you!?”

“Yea, let’s try not to think of that…hey, you don’t have any food, do you Mark? That candy didn’t exactly hold me over.”

“Oh, sure man! Hold on a second.” Mark runs off and puts a couple crackers on a paper towel on the table.

“Thanks Mark! I’m starved!”

“No problem buddy! Hey, I just have to check on one thing on the computer for work before Tyler wakes up. He always hogs the computer with games. You eat up and I will be right back!”

Tyler? Who is Tyler? Oh, right, Mark’s stoner roommate. He is a bit of a waste of space, but Nick needed somebody to help pay the rent. He actually isn’t such a bad looking guy, if he would just get a real job. He was only 21, fresh out of college and looking for work. He was 6’1’’, had a swimmers build and brown styled hair, with brown eyes and a little stubble on his face. Nick remembers seeing pictures of him on Facebook. Oh well, at least Nick will get to spend the entire week with Mark, even if that means Tyler is around too.

Just as Nick is digging into the crackers, he catches something out of the corner of his eye. Startled, he looks into its direction only to see a MASSIVE spider, the same size as he is heading towards him. Terrified, Nick screams and heads in the opposite direction of the spider. Nick didn’t notice that he was nearing the end of the table as he was looking over his shoulder to monitor the progress of his attacker. Nick reaches the tables end, and tumbles right off of it. He falls for what feels like an eternity until finally landing on a soft, plush surface. Mark must have been about to do laundry as a basket full of unwashed clothes sits beside the table and breaks Nicks fall.

“Holy SHIT! What the fuck!? Ok, enough of this…I need to go get Mark!” Nick climbs off the clothes and makes his way towards the computer where Mark is diligently working, still clad in all of his gym clothes. On the way to the computer, Nick feels the familiar feeling from in the box of his muscles becoming stiff. “No, not now! NOT NOW!” Nick thinks. Nick barely makes it to the foot of the computer where Mark is sitting. He opens his mouth to shout up at Mark when, he freezes. Nick is once again stuck in one position only mere inches from the right foot of his best friend.

As Mark works, he begins to fidget with his feet. He slowly kicks off his Nike running shoes and brushes them to the side. Immediately Nick is hit with the warm, humid stench from Mark’s feet. The smell seemed to be a mix of vinegar, cheese and salt. As if the smell wasn’t bad enough, Nick looked up in time to see Mark’s slightly dirty, white no show sock descending directly over him. The impact came shortly after that. The soft, moist fabric rubbing all over Nick’s body. Mindlessly, Mark pushed his foot back and forth causing Nick to roll under his sole. Before long, Nick was completely covered in sweat and grime from Mark’s socks. This continued for some time until Mark decides that his socks have become a burden and removes them revealing his perfect, size 12, soft sole with long, plump toes. His arch is directly overhead, with slight creases in the skin as it too begins to descend onto Nick. The impact of the bare foot is much worse than with the sock. The smell, the sweat, the texture is all magnified on the bare foot. Nick’s face is pressed into the soft flesh of Mark’s sole. His toes wrap around Nicks head causing him to gag a little.

The form in between his toes must have raised some suspicion in Mark as he, briefly looks away from the computer screen, down at his feet to see Nick’s tiny form pinned under his toes. “NICK! SHIT MAN! I am so sorry! Dude these boys are RANK after the gym, I can only imagine how badly they smell!” When Nick didn’t respond in any way, Mark figures out what happened. “Ah, frozen again I see. You should do a little more research next time, eh? Here, for now let me put you back into your box so you’re safe until I am done!”

Mark carries the still form of Nick and places him back into the box where he found him. Mark leaves to head back to his work saying “OK, now don’t move. HAH! Ok, bad joke, sorry.” Nick only had a few minutes to himself to think about all the fun he and Mark would have this week when he suddenly hears a door quietly open behind him. Footsteps. He sees a dominating image pass by his box. He can barely make out that it is Tyler’s head, heading for the fridge. Tyler opens the fridge, and Nick hears him groan and close the fridge. He turns around and his eyes fall immediately on the box and his eyes light up.

Tyler looks groggy, wearing a white t-shirt, shorts and his hair is slightly messed up and his stubble is a bit longer than usual. Tyler’s lips creep into a smile as he sees the wrapper reading “candy.” His hands reach for Nick’s solid form. Tyler isn’t as gentle as Mark was. He grabs Nick in a tight fist and brings him up to his face. He gives Nick a long lick and smacks his lips. “MM, not bad!”

Nonchalantly, Tyler takes his hand and moves it quickly towards his mouth. Nick is projected into his mouth at full speed. He slams into the uvula at the back of Tyler’s mouth and falls down to his tongue - Also, soft, but a little moister than Mark’s was. His breath had a hint of weed in it mixed with some tooth paste. Tyler savors Nicks flavor for a while rolling him around, sucking on him and tasting the morsel. Nick slowly senses his feeling returning. “THANK GOD! JUST IN TIME,” he thinks to himself.

Nick lets out a similar scream and protest as to the one from in Mark’s mouth, only with less success. Tyler ignores the protests and continues his snacking. Feeling the wiggling in his mouth, Tyler says to himself “Fuck, I must still be high. I swear my food is moving. I guess there is only one way to end it.”

With that, Tyler places Nick into the center of his tongue. He tilts his head back some and Nick slides back to the uvula. Just as he is about to reach the back of the throat he stops. Saliva drenches him from head to toe. Suddenly, Tyler’s tongue flips up throwing Nick into the back of his throat. He meets the moist uvula which swiftly forces him downward to the opening of the esophagus. Nick pauses there for a second, only to be greeted with a second, stronger pressure from the uvula along with a loud *GULP* noise. Nick screams as loud as he can as his squirming form is forced into the tight opening of the esophagus. The muscles in the uvula slowly work Nicks struggling body down towards the stomach. Outside, Tyler’s neck bobs in and out as he swallows his breakfast. He lets out a satisfying sigh as Nick continues his descent to the stomach. Finally, Nick reaches the opening of the stomach. He is squeezed through a tight opening and falls with a splash into the empty stomach below. He immediately gets up and begins screaming, kicking, clawing, doing anything he can to escape. Tyler merely ignores the squirms and heads back to bed, blaming the feeling on hallucinations from the weed. Realizing it is useless, Nick slowly drifts off to eternal sleep in the stomach juices.

Sometime later, Tyler wakes up again to find Mark searching frantically around the apartment. “Dude, what are you looking for?” he asks.

“Oh it’s uh, oh never mind!” Mark says frantically, obviously frustrated by his lack of success.

“Well, whatever it is, forget it. You should go out and get more of that candy instead. I had that last piece earlier today, and it rocked my world dude.”

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Babaaláwo or Babalawo in West Africa (Babalao in Caribbean and South American Spanish and Babalaô in Brazilian Portuguese) literally means "father of secrets" in the Yoruba language. It is a spiritual title that denotes a high priest of the Ifáoracle. Ifá is a divination system that represents the teachings of the ÒrìṣàỌrunmila, the Òrìṣà of Wisdom, who in turn serves as the oracular representative of Olodumare.

Functions in society

The Babalawos are believed to ascertain the future of their clients through communication with Ifá. This is done through the interpretation of either the patterns of the divining chain known as Opele, or the sacred palm nuts called Ikin, on the traditionally wooden divination tray called Opon Ifá.

In addition to this, some of them also perform divination services on behalf of the kings and paramount chiefs of the Yoruba people. These figures, holders of chieftaincy titles like Araba and Oluwo Ifa in their own right, are members of the recognised aristocracies of the various Yoruba traditional states.

People can visit Babalawos for spiritual consultations, which is known as Dafa. The religious system as a whole has been recognized by UNESCO as a “Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity."

#unesco#babalawo#dafa#yoruba#african#afrakan#africans#brownskin#afrakans#kemetic dreams#brown skin#african culture#afrakan spirituality#nigerian#ancestors#peace#metaphysics#araba#opele#ifa#ouwa#olodumare#orisa#orunmilla#orun#traditional african religion#west africa#yoruba language#father of wisdom#orisa of wisdom

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

🇬🇩 🇬🇩 At the core of Jab Jab culture lies a rich history intertwined with the struggles of the African diaspora and the emancipation of enslaved people in the Caribbean. The term “Jab Jab” or “J’Ouvert” is derived from the French patois word “diable,” meaning “devil.” However, its literal meaning is not related to demonic culture but symbolises the spirits of Grenada’s African ancestors.

During the days of slavery, Carnival festivities were primarily reserved for the white ruling class or plantation owners. However, the Enslaved Africans on the sugar plantations found their own way to celebrate their freedom. A masquarder playing Jab Jab is playing the devililish souls of the slave masters. Drawing on African dance traditions the enslaved ridiculed the slave owners through masquerade and song. They emerged as a mass of resistance, celebrating their liberation from hardships. Over time, the Jab Jab tradition evolved and became an integral part of Grenadian culture and heritage.

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

"We are thrilled to announce the launch of the Garifuna International Indigenous Film Festival (GIIFF) on November 9th-November 12th, 2023, a groundbreaking initiative dedicated to supporting and preserving the Garifuna nation and all indigenous cultures being held at the Electric Lodge located in Venice, California.

This unique film festival will create a platform for filmmakers, artists, and community leaders/members to showcase their works while emphasizing the importance of cultural diversity and representation. The Garifuna people, originating from the Caribbean Island of St. Vincent, possess a rich tradition and enduring heritage that deserves global recognition. The Garifuna International Indigenous Film Festival aims to bring this vibrant culture to the forefront and shed light on the struggles and triumphs of the Garifuna nation and other indigenous communities worldwide.

The underlying objective of GIIFF is to promote a deeper understanding and appreciation of indigenous traditions, values, and stories. Through the power of film, GIIFF aims to bridge gaps, foster dialogue, and debunk stereotypes surrounding indigenous cultures.

This multidisciplinary approach will not only provide a unique experience for audiences, but it will also contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage for future generations.

GIIFF will feature a diverse selection of thought provoking-international films, documentaries, workshops, cultural presentations, and short films that center around indigenous cultures. The festival strives to create an inclusive space, where filmmakers and artists can engage with industry leaders, intellectuals, and audiences who share a passion for the sense of community and collaboration, encouraging meaningful conversations and connections.

This inclusive space not only allows industry leaders and intellectuals to engage with these powerful stories but also invites audiences from all walks of life to immerse themselves in the beauty and diversity of indigenous cultures. The GIIFF is more than just a film festival; it is a celebration of heritage, resilience, and the power of storytelling."

-via Garifuna Indigenous Film Festival, October 2023

#indigenous#first nations#indigenous peoples#indigenous history#garifuna#caribbean#carribbean#film festival#los angeles#st. vincent#cultural heritage#documentaries#good news#hope

131 notes

·

View notes

Photo

An Archaeology and History of a Caribbean Sugar Plantation on Antigua

Georgia L. Fox's "An Archaeology and History of Caribbean Sugar Plantation on Antigua" offers a meticulous and interdisciplinary exploration of Betty's Hope, which was one of Antigua's most prominent sugar plantations. This book is a significant contribution to Eastern Caribbean historical archaeology, providing insights into colonialism, slavery, and environmental change.

This book is a collection of essays that blends archaeology, archival research, and environmental studies to examine the history and material culture of Betty's Hope, established in the 1650s by the Codrington family. Moreover, Fox, alongside a team of scholars, analyzed and dissected various facets of plantation life, including enslaved labor, agricultural practices, and the plantation's ecological footprint.

On Caribbean plantations like Betty's Hope, sugar reigned supreme - its cultivation dictated the rhythms of life, drove economies, and forged an empire built on the backs of the enslaved. The chapters will provide readers with detailed archaeological investigations and findings at Betty's Hope that give readers a window into the lives of enslaved Africans and the plantation's operational infrastructure and system. The author also provides discussions on the excavation of the windmill, cistern, production, equipment, and the lifestyle of enslaved laborers, revealing the ingenuity and resilience of the enslaved population despite oppressive conditions in slavery.

The book effectively conveys the idea that sugar was the driving force behind Caribbean colonialism, encapsulating the phrase “sugar was king.” Fox situates Betty’s Hope within the wider Atlantic world, where plantations served as profit-making machines for European empires. The book traces the exploitation of human labor, with enslaved Africans reduced to mere cogs in the machinery of sugar production. This systemic exploitation enabled the accumulation of wealth in Europe while impoverishing and dehumanizing those who labored under its weight in the Caribbean.

One of the book’s significant contributions lies in its nuanced portrayal of the enslaved. The analysis of material culture gives an insight into how enslaved people faced the harsh reality of living in a plantation society. While they had little control over their labor, enslaved individuals asserted agency in subtle but meaningful ways, such as in their foodways, religious practices, and community-building efforts. The recognition of these forms of resistance counters traditional narratives that depict enslaved populations as entirely subjugated.

This book also highlights the devastating environmental consequences of sugar cultivation. The plantation’s reliance on monoculture exhausted Antigua’s soil, while the need for constant water supply led to the construction of elaborate cistern systems and windmills. The ecological legacy of this exploitation persists today, and the book offers a critical reflection on how colonial environmental practices continue to shape Caribbean landscapes.

The book extends its analysis beyond the past, emphasizing the importance of preserving plantation sites like Betty’s Hope. She discusses the challenges of conservation in the 21st century, where such sites are simultaneously spaces of historical memory and painful reminders of exploitation. The restoration of Betty’s Hope, including its iconic windmills, raises questions about whose histories are prioritized in heritage narratives and how these spaces can foster meaningful engagement with the past for citizens.

The book has a variety of strengths that make it a very important publication on Antiguan history and archaeology. Fox’s ability to synthesize archaeology, history, and environmental science makes this book a standout contribution to Caribbean and historical studies. The archaeological data is seamlessly integrated with historical records and environmental investigations, providing a holistic understanding of plantation life in the Caribbean. Secondly, by centering the experiences of the enslaved people, the book challenges Eurocentric interpretations of plantation history. The analysis of artifacts and settlement patterns paints a vivid picture of the enslaved community’s resilience and creativity. Finally, the book situates Betty’s Hope within the global dynamics of the transatlantic slave trade and sugar production. This perspective highlights the topic of colonial economies and underscores the Caribbean’s pivotal role in shaping the Western world.

The only limitation of the book is that it provides an in-depth study of Betty’s Hope. It could have benefited from a more explicit comparison with other Caribbean plantations. This would have strengthened its claims about the universality and uniqueness of plantation practices in Antigua.

An Archaeology and History of a Caribbean Sugar Plantation on Antigua is a groundbreaking work that offers a profound understanding of the Caribbean plantation complex. By integrating archaeological evidence, historical documents, and environmental studies, Georgia L. Fox, Professor of Anthropology at California State University, Chico, and her collaborators provide a great view of Betty’s Hope as a microcosm of colonialism’s economic, social, and ecological impacts. This book is important reading material for scholars of Caribbean history, historical archaeology, and heritage studies.

Continue reading...

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Honest Review of ‘Slavic Witchcraft; Old world Conjuring Spells and Folklore’ , By Natasha Helvin

Before I start, I am not here to question Natasha’s heritage or place in the Caribbean African diaspora spirituality’s. If you have comments on that, that’s up to you. I neither have the background or place to discuss that.

My review is also on my Goodreads,

Review

Natasha Helvin, as described in her own words, is an occultist, hereditary witch, and priestess of Voodoo. Born in the Soviet Union and later moving away at 18. She claims to have learned from her mother and grandparents, the traditions of old world Slavic paganism.

All this and yet, she cannot source anything she says, save a very unfounded “Just trust me.”

The book is separated into 10 chapters, the first two and introduction focusing on ‘The traditions,’ and other folklore information as well as history. The later 8 sections are all about Spells and spell work, and superstition.

Introduction; Sorcery as a Living Tradition.

Slavic Witchcraft was published in 2019, deep into the popularization and hype of witchcraft and paganism in the 21st century. And yet, Natasha chooses to open her book with a Cautionary Note, which warns the reader that what is inside is ‘taboo’ and ‘forbidden.’ Which is what initially made me raise an eyebrow at what I was reading.

The majority of this section was just discussing her childhood, and experiences to solidify her position as the teacher in this book. Nothing too unusual, and nothing of note. I won’t comment on someone’s life experiences as a point of note. But it’s hard to see the point in bringing it up, when it just loops over itself, as if to philosophize on it rather then make a point. Nostalgia is a valid place to write from, even in Spirituality and Nonfiction, but there are ways to go about it, to make a point. As an example; Braiding Sweetgrass, By Robin Wall K. She makes many points of talking about her life, that ultimately ends with her informing the reader of a life lesson. In Slavic Witchcraft, this just becomes a loop, that is hard to read.

1, Pagan Christianity or Christian Paganism

This Chapter highlights the most glaring issue in the entire book. There are NO SOURCES. Throughout this chapter Natasha Heavily references historical events and real life situations that do have the history to back them up. The Indoctrination into Orthodox Christianity, and the way they amalgamated pagan practices into their religion, are true historical facts. The way paganism out beat Christianity in Russia multiple times, are facts. However, the author refuses to use references and build a bibliography which makes everything she says feel less credible.

Here I will also address the 4 Elements. This isn’t the first and won’t be the last time I bring it up in a Spirituality book review.

Where is your information on the four elements as the building blocks of the universe coming from. It’s not a universal idea? Multiple other cultures have elements ranging from 3-5 or six. I would love genuinely a reference from where Natasha has the Ancient Slavs using these elements as a structure of their beliefs.

2, Slavic Magic Power and Sorcery

There’s a lot of things in this section that just require the reader to trust that Natasha is telling the truth without any resources to reference. Once again a lot of this book would have benefited from sources but because there are none, you just have to trust her.

An example is the Sorcerers Song. She dedicates quite a bit of this chapter to ‘folklore’ and often references this thing called the sorceresses/sorcerers song. The song in question is the dying sorcerers last words, before they transfer magic to someone else. A lot of the stuff in here is very fantastical, and there is a level of difficulty in understanding what is just fun storytelling on the authors part and what is to be believed as fact.

Here she also contradicts herself on the facts of who can and cannot be a witch.

What a witch is according to folklore, where the unfortunate use of a Romani slur is used, in a sentence that is just a repetition of really old racism. How can you write the sentence that describes witches as “ugly iron toothed and (racial stereotypes)” without also clarifying that these are all descriptions from a post orthodox and heavily antagonistic mindset?

These chapters really clarified for me that this book is not about Slavic paganism as a religion but rather, Ms Helvins Experience as a pagan with a post Christian Russian heritage. Everything is still very Christian. Which isn’t bad and not wrong, most folk magics we see today come from a Christian background because that is the most common religion of all our ancestors. This book isn’t a reconstruction of Slavic paganism, or Slavic pagan as a broad term regardless. It’s Natasha’s paganism.

The rest of the book focuses on Spells, which are for the most part fine.

I have personal issues with her opening comments on All people were made by god as man and woman and our true desires are to find our other halves. Okay, no.

I have issues with the amount of times she references everything and everyone around us as “manipulatable” that all things fall under our whims. Which is morally uncomfortable. I don’t think our ancestors who worked alongside animals and plants always saw them as lower, as seen in, still Alive and well, Indigenous American beliefs.

In the end, this book isn’t for beginners, it’s not for Slavic pagans, it’s for Natasha. And that’s fine.

#witchcraft#paganism#witchblr#pagan#pagan witch#paganblr#pagans of tumblr#slavic paganism#slavic witch#slavic witchcraft

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guava rugelach are an edible testament to Jews embracing the new ingredients and cooking techniques that they encountered in the Diaspora. They are also a testament to my mom, a culinary magician who wielded guava like a wand, infusing its sweet tones into our meals.

Brought to Latin America by Eastern European Jews in the early 20th century, cities such as Buenos Aires, Mexico City and Caracas have embraced rugelach. While many versions of the pastry still proudly bear the traditional Ashkenazi flavors of cinnamon, raisins and nuts, that’s far from the whole tale. Rugelach in Buenos Aires or Caracas might contain dulce de leche or cabello de ángel (pumpkin jam), while a stroll into a bakery in Mexico City might reveal rugelach filled with luscious chocolate ganache and aromatic Mexican vanilla.

This rugelach dough is enriched with sour cream, and results in a soft, flakey pastry. The pièce de résistance, though, is the guava filling.

Originating from Central and South America, “guava” translates to “fruit” in Arawak, the language spoken by the native communities of the Caribbean, where this fruit, similar in size to a passion fruit, grows in abundance. The guava’s tender skin encases a creamy white or orange pulp filled with numerous tiny black seeds.

As guava is a seasonal fruit and isn’t as widespread as mangoes or papaya, I call for guava paste, due to its unique sour-sweet taste profile. Often referred to as “goiabada,” this paste generally has a lower quotient of added sugars and presents a superior texture for baked products. Unlike runny jams and marmalades, guava paste is sculpted into a dense, sticky block yet remains soft enough to be sliced.

Growing up, my mom used the vibrant, naturally sweet guava as her secret ingredient, a touch of the tropics that hinted at Caribbean culinary tradition in Venezuela. It turned the simplest family recipe into an exotic treat. This recipe draws inspiration from her traditional guava bread, where history, heritage and affection were kneaded into dough and baked to perfection.

Her guava-infused creations echo loudly in my present, shaping the culinary adventurer in me and reminding me of the vital link between taste and memory. Guava rugelach are not merely a pastry but a narrative of the age-old Jewish practice of reinventing ourselves in the face of new environments. The story of my lineage in the Diaspora, one many fellow Jews can relate to, is etched in the buttery dough and sweet, aromatic filling. Each bite is a reminder of who I am: A fusion of cultures, histories and flavors.

40 notes

·

View notes