#Canaanite Polytheism

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Jehovah, Jehovah, Jehovah!... No, actually, it's Yahweh,

A somewhat notable Deity considered by the ancient Israelite people their National God and first attested from the early 9th century BCE.¹

This c. 1518 painting by Raphael is based on a mystical vision of 𒀭Yahweh attributed to the prophet Ezekiel who belonged to a priestly lineage said to be descended from the legendary Joshua. Ezekiel was active during the time the Kingdom of Judah was conquered by the Neo-Babylonian Empire in the early 6th century BCE. (Public domain)

𒀭Yahweh was also apparently worshipped among the Edomites, the Israelites' southern neighbors, based on a reference to “Yahweh of Teman” in an inscription on an early 8th century BCE jar discovered at the site of Kuntillet Ajrud in the Sinai.¹ It's believed that at this time the Ajrud outpost was controlled by the northern Kingdom of Israel as it fell into their hands after a botched invasion by the southern Kingdom of Judah. The two kingdoms were also under the yoke of the Neo-Assyrian Empire at this time with contemporaneous Assyrian records noting both Judahite and northern Israelite representatives.²

Illustrations of the two vessels from Kuntillet Ajrud with translations. It's debated if the 𒀭Bes-type figures on Pithos A are meant to depict 𒀭Yahweh and His Consort 𒀭Asheratah, but it should be noted the righthand figure does not actually have visible genitals as the outdated illustration here shows.³ (Source)

Although 𒀭Yahweh is primarily associated with monotheistic religion nowadays for obvious reasons, historical evidence indicates He was first worshipped in a polytheistic context as the Israelite culture distinguished itself from the Canaanite milieu it emerged from. This can even be seen within the Hebrew Bible; A wonderful example is found in the Book of Habakkuk in the form of an archaic Hebrew poem describing 𒀭Yahweh and His Company including the Plague-God 𒀭Resheph (His Name is usually mistranslated as “plague” in English Bibles) battling sea monsters. Another one of the most noted can be seen in the Book of Deuteronomy and indicates 𒀭Yahweh was probably worshipped as One of the Seventy (symbolically “many”) Sons of 𒀭El:

⁸ When Elyon apportioned the nations, when He divided humankind, He fixed the boundaries of the peoples according to the number of the Gods; ⁹ Yahweh's own portion was His people, Jacob His allotted share.

Deuteronomy 32:8–9 (adapted from the New Revised Standard Version, Updated Edition, 2021)

𒀭Yahweh very much fits the form of other Storm-Gods worshipped in cultures of the Syro-Palestinian region during the Iron Age. The other most famous example of such a Deity is the Levantine manifestation of 𒀭Ba'al Who is cast as 𒀭Yahweh's greatest Rival in the collection of texts within the Hebrew Bible known as the Deuteronomistic history, although the presence of 𒀭Ba'al's name at Ajrud would suggest this conflict is a later idea. It's even been suggested 𒀭Yahweh was originally associated specifically with destructive elements of weather such as flash floods.⁴ Although there are some respectable academic claims of pre-Israelite attestations of 𒀭Yahweh from the Late Bronze Age, none of these are secure and all of them are very much contested.⁵ The scholar Christian Frevel also fascinatingly proposed in 2021 that 𒀭Yahweh was the tutelary Deity of the Omride clan which came to rule the northern Kingdom of Israel for over a century and established its capital of Samaria.¹

A modern artistic impression of a ritual performed by ancient Israelites at the Temple of 𒀭Yahweh in Jerusalem during the Iron Age. The dedication of the Temple in Jerusalem built by King Solomon (c. 1910) by William Hole. (Public domain)

The emergence of monotheism from traditional Israelite belief is an incredibly convoluted topic that I don't intend to get into the weeds of here. One of the most recognizable milestones therein, though, was the religious reforms of King Josiah of Judah shortly before our dear Ezekiel's time. This saw the absolute consolidation of religious authority in the Temple of 𒀭Yahweh at Jerusalem and even the forced closure of all other cultic sites in Judah. However, there's also direct evidence that 𒀭Yahweh continued to be worshipped among other Gods and Goddesses well after the monotheistic, Jerusalem-centric religion which came to be known as Judaism had entered its Second Temple Period.

Most notably a community of Israelites living on the island of Elephantine at ancient Egypt's southern frontier had a Pantheon in which 𒀭Yahweh was associated with the Goddess 𒀭Anat and another God named 𒀭Bethel.⁶ They even had Priestesses of Yahweh and were apparently on good terms with Jerusalem as indicated by the Aramaic-language texts written in Egyptian Demotic script discovered at Elephantine. An analysis of the narrative of Aaron's Rod in the Book of Numbers has also led to the alluring proposition that worship of the famous 𒀭Asherah as 𒀭Yahweh's Consort may have continued even within the Jerusalemite cult itself during this period.⁷

An altar of incense discovered at the site of ancient Ta'anakh. Although it's dated to the tenth century BCE, predating any secure attestations of 𒀭Yahweh, some researchers believe the top and second-to-bottom registers are intended to symbolize Him with His 𒀭Asherah likewise on the alternating registers. (Source)

There's so many fascinating developments being made in archaeology and the study of history unraveling more about the ancient Israelites and the worship of 𒀭Yahweh before our very eyes. I honestly feel incredibly privileged to be alive just in time to witness such a thing. Although I haven't “worked with” 𒀭Yahweh myself within my primarily Canaanite Pagan practice, I'd be very interested to hear and discuss different perspectives on this fascinating ancient Deity and it'd make me very happy to see what some of you think. Shulmu 𒁲𒈬 and thank you so much for reading!

Another thing

Given what part of the world this all concerns, I feel I would be morally remiss to say nothing of the genocide taking place against the Palestinian people in their homeland and particularly in Gaza. I find this important because earlier today the so-called President of the United States Donald Trump expressed the US's intent to “take over” and ethnically cleanse Gaza at a public event alongside Benjamin Netanyahu, the so-called Prime Minister of Israel. In the face of such great evil, I feel obligated by simple virtue of being a human to state I wholeheartedly support the full liberation of Palestine and an end to the unjust and unlawful occupation with all it has wrought. Arab.org is a website which allows you to support Palestinians via a simple click of a button with no donation necessary along with providing further resources. Free Palestine 🇵🇸

References

Frevel, Christian. “When and from Where Did YHWH Emerge? Some Reflections on Early Yahwism in Israel and Judah.” Entangled Religions 12:2 (March 30, 2021). https://doi.org/10.46586/er.12.2021.8776.

Na’aman, Nadav. “Samaria and Judah in an Early 8th-Century Assyrian Wine List.” Tel Aviv 46:1 (January 2, 2019): pp. 12–20. https://www.academia.edu/43169801.

This was clarified by archaeologist Ze'ev Meshel in communication with Nir Hasson reporting for Haaretz, https://www.facebook.com/share/1JASsUsdcN.

Fleming, Daniel E. “Yahweh among the Baals: Israel and the Storm Gods.” Essay. In Mighty Baal: Essays in Honor of Mark S. Smith, edited by Stephen C. Russel and Esther J. Hamori, pp. 160–74. Harvard Semitic Studies 66. Leiden, Netherlands; Boston, Massachusetts, United States: Brill, 2020.

Pfeiffer, Henrik. “The Origin of YHWH and its Attestation.” Essay. In The Origins of Yahwism, edited by Markus Witte and Jürgen van Oorschot, pp. 115–44. Beihefte Zur Zeitschrift Für Die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 484. Berlin, Germany; Boston, Massachusetts, United States: De Gruyter, 2017.

Cornell, Colin. “Judeans and Goddesses at Elephantine.” Ancient Near East Today 7:11 (November 2019). American Society of Overseas Research (ASOR). https://www.asor.org/anetoday/2019/11/Judeans-and-Goddesses-at-Elephantine.

Eichler, Raanan. “Aaron’s Flowering Staff: A Priestly Asherah?” TheTorah.com, 2019. https://www.thetorah.com/article/aarons-flowering-staff-a-priestly-asherah.

#ancient history#ancient near east#history#pagan#paganism#semitic pagan#semitic paganism#ancient levant#baal#bronze age#iron age#canaanite pagan#canaanite paganism#canaanite#canaanite polytheism#yahweh#yhwh#el#asherah#anat#resheph#canaan#israelites#israelite#ancient israelite#ancient religion#ancient egypt#elephantine#polytheist#polytheism

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

⚔️Subtle Anat Worship🏹

Greatly inspired by @khaire-traveler's wonderful subtle worship series, which can be found here.

Learn self-defence, weapons included or not

Work on becoming more comfortable with the idea of conflict; it is only natural that we sometimes disagree with people

Learn about and uphold Ma'at

Make a playlist or listen to songs that remind you of her or you think she'd like

Make a collage/moodboard/pinterest board/similar collection of photos and images you associate with her, especially if some of the images are your own

Wear a piece of jewelry or other clothing item that reminds you of her

Light a candle or incense that reminds you of her (safely)

Carry a picture of her in your wallet, pocket, phone case, etc. or as a phone or computer wallpaper

Have spear, shield, weapon, cow, or eagle imagery

Do something hard or challenging, especially if you've been putting it off, or it needs to get done

Make a list of your personal strengths and things you're proud of

Exercise a little, even if it's just stretching

Play combat-based video games

Practice standing up for yourself; speak your mind and assert your personal boundaries

Allow yourself to express your anger and frustration; sit with and feel your feelings

Carry a protective charm

Writing letters (that you will never send) to people who've hurt you and burning them

Stand up for family members blood or otherwise and other people you care about (keep in mind they might be in the wrong)

Get more comfortable with the idea that we don't get along with everyone; it's ok if someone doesn't like you

Stand up for what you believe in; attend protests or activism events (be safe, please)

Allow yourself to mourn over difficult changes or the end of relationships; allow yourself to miss people

Learn about healthy conflict resolution skills; try to implement these in your next conflict

Find ways to express yourself, even if it's small

Learn archery

Spend time out in nature (e.g. go on a hike, take a walk outside, visit a nature preserve, etc.)

Befriending neighborhood animals, such as cats, birds, or dogs; leaving food out for them

Learn about plants and animals, especially those that are native to your area or the areas she was worshiped

Learning how to safely forage for food, such as picking berries or mushrooms

Eat in season produce; support local farmers

Learn about local invasive species, plants or otherwise; get rid of any invasive plants you see, if safe to do so

Do things to help local wildlife like hanging up suet feeders, building bat boxes, etc.

Take care of your body physically to the best of your ability (shower, eat well, get a good amount of sleep, etc.)

Take your medications, if any; take medications as needed

Take care of a sick loved one or someone who is having a hard time

Learn about/research health conditions that you or your loved ones have; get a better understanding of these things

Clean anything you regularly interact with

Look into healthy coping skills for any anxiety, depression, trauma, etc. - anything that can improve your mental/emotional well-being

Learn about your healthcare options and medical rights (HIPPA in the US)

Donate blood

Set boundaries for yourself; I'll only give this much support to that person, I won't stay on my phone for hours before bed, I won't engage with this media that always upsets me, etc.

Although I am coming to this from a kemetic perspective, I have tried my best to research her so that this list is reflective of the many different places she was worshiped in and should hopefully be useful for those who worship her outside a kemetic context.

I may add more to this list in the future. Suggestions are always appreciated.

Link to the Kemetic Subtle Worship Masterpost

#kemetic polytheism#kemetic#kemetic paganism#kemeticism#kemetism#levpag#canaanite polytheism#canaanite paganism#subtle deity worship#Anat#polytheism#pagan tips#deity worship#paganblr

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm here for goth girl Anat

Are you?

#esoterica#anat#canaanite mythology#canaanite polytheism#ugaritic mythology#ugaritic polytheism#paganism#war gods#esoteric shitposting

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

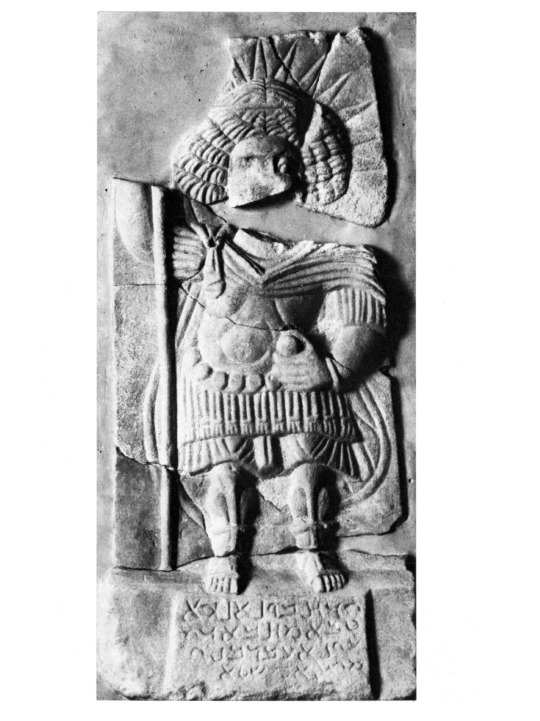

Yarhibol, the Sun-God Dura-Europos, Syria c. 50 CE Source: The Pantheon of Palmyra by Javier Teixidor, 1979

#yarhibol#dura europos#canaanite paganism#canaanite polytheism#canaanite gods#levantine paganism#phoenician#phoenician paganism#phoenician polytheism#phoenician gods#syrian paganism#syrian polytheism#syrian gods#natib qadish#pagan#paganblr#paganism#polytheism#witchcraft#witchblr#magic#occult

84 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Huh, I remember reading about this being a statue of Astarte.

Babylonian Alabaster Statue of the goddess Ishtar, 350 B.C.

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Ok so back a few years ago, maybe more like 5?

There was a levpag content creator who made collaged images of the gods and now I can’t find their work. I was trying to specifically find the images for Ashera/Athirat and El/Ilu.

Are you still out there? Do you still publish these images for community use?

0 notes

Text

I seriously don’t understand why more people aren’t talking more about this. I think it’s interesting!

https://academia.edu/resource/work/122323191

#AddsContext

(Academia.edu = #academic papers)

#CanaaniteReligion, #UgaritReligion, #El, #Yahweh, #polytheism, #monolatry, #monotheism, #HistoryOfReligion

#CanaaniteReligion#Canaanite Religion#UgaritReligion#Ugarit Religion#UgariticReligion#Ugaritic religion#El#Yahweh#polytheism#monolatry#monotheism#HistoryOfReligion#history of religion#comparative relligion#biblical scholarship

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Steven Dillon's conversion to Christianity: what does it mean to Hellenism and Pagan Community?

Steven Dillon, the author of "The Case for Polytheism" and "Pagan Portals - Polytheism: A Platonic Approach", recently returned to Christianity.

This event made me think a lot. I think this event can teach us that the more you are concerned with "the One" and you think it can respond, the more likely you will go towards monotheism.

The point is that "the One" is us, and is "a thing", not "somebody".

The One is not a person. This is the reason why we worship the Gods, they are persons.

The One, the All, is so big that the idea that it can listen is nonsense.

Monotheism emerges when you think the entire universe can listen to you. Polytheism is the humbleness to understand that only certain parts of the Universe can listen to you.

And when you think you are talking to the One you are always actually talking to a part of it.

This is the reason why Christ, Yahweh, Allah, etc. are parts of the One and not the One.

Even attempts to interact with the entirety of the One are just interactions with parts of the One, ie one of the many Gods.

This is confirmed by Aleister Crowley's experience, we can read from the Liber Astarte Vel Berylli that he considered Allah, Christ and Yahweh as Parts or Aspects of the One, exactly as other Polytheistic Deities, and not as the All/the One in its entirety:

"Let the devotee consider well that […] Christ and Osiris be one […]".

"As for Deities with whose nature no Image is compatible, let them be worshipped in an empty shrine. Such are Brahma, and Allah. Also some postcaptivity conceptions of Jehovah".

"[…] the particular Deity be himself savage and relentless; as Jehovah or Kali."

-

Moreover, Dillon was (is?) Platonic, and the problem is even worse, because sadly the reaction to the problem of evil is very similar between Platonism and Christianity.

However, the Stoic (and maybe the Hindu and Buddhist) worldview completely destroys the problem of evil, because if the Divine is good and we simply don't perceive the goodness and that is what evil is, ie ignorance or misperception, then the problem of evil is solved.

If we, instead, perceive the evil as something real and the Gods as totally good not evil, the problem of evil remains.

-

Finally, a Pagan that comes back to Christianity usually doesn't know history very well, and is unaware of Natib Qadish, ie Modern Canaanite Religion or Neopaganism.

If you listen to Natib Qadish (ie Canaanite and Israelite Polytheistic Neopaganism) and Wathanism (Arabian pre-Islamic Polytheistic Neopaganism) practitioners' voices, you cannot come back to Christianity.

In fact, Christianity doesn't make any sense: Yahweh is a Storm God that comes from Edom to Israel through the Kenites or Shasu, which were nomads. His name meant "to blow", and so he was a variation of Baal Hadad.

In the origin, El was the father of Baal/Yahweh, and his sister was Anat and his mother Asherah. Later, El ie the Sky God and Yahweh ie the Storm God, merged and so Yahweh was seen as the husband of the Goddess Asherah.

In fact in Kuntillet Arjud it's possible to see blessings by "Yahweh and his Asherah". Moreover, even the Bible (read The Book of Judges) witness that people worshipped Asherah/Astarte and Baal together with YHWH.

In Elephantine in Egypt there was a Jewish temple for Yahu-Anat, ie both Anat and YHWH.

So how can Jesus be the son of the only God Yahweh if Yahweh was never a monotheistic God before the Josiah's reform that made Judaism monotheistic?

If Judaism is originally polytheistic then Christianity makes no sense.

By reading the "Cycle of Baal" we'll discover the origin of the Biblical Deity (or Deities?).

youtube

I end my dissertation with some interesting quotes from the Bible:

Jeremiah 7:

"17 Do you not see what they are doing in the towns of Judah and in the streets of Jerusalem? 18 The children gather wood, the fathers light the fire, and the women knead the dough and make cakes to offer to the Queen of Heaven."

Jeremiah 44:

"17 We will certainly do everything we said we would: We will burn incense to the Queen of Heaven and will pour out drink offerings to her just as we and our ancestors, our kings and our officials did in the towns of Judah and in the streets of Jerusalem. At that time we had plenty of food and were well off and suffered no harm. 18 But ever since we stopped burning incense to the Queen of Heaven and pouring out drink offerings to her, we have had nothing and have been perishing by sword and famine.”

"19 The women added, “When we burned incense to the Queen of Heaven and poured out drink offerings to her, did not our husbands know that we were making cakes impressed with her image and pouring out drink offerings to her?”"

"25 This is what the Lord Almighty, the God of Israel, says: You and your wives have done what you said you would do when you promised, ‘We will certainly carry out the vows we made to burn incense and pour out drink offerings to the Queen of Heaven.’"

#Hellenism#Paganism#Polytheism#devotional polytheism#Christianity#Canaanite#Platonism#Neoplatonism#Natib Qadish#Youtube

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

A suggestion from someone new to Canaanite Paganism

This sort of ties in to some local cultus kind of deal, but with Halloween coming up I was thinking about adding a Canaanite flavor.

Now this is sort of UPG but bear with me here. If you're a Canaanite pagan, you probably know about Mot.

He's the spooky God of death, always hungry for pretty much anything and everything (man or God alike), and he received absolutely ZERO offerings or worship. So around this time of year it could be that M/t is at his worst, looking for prey. Carve a scary face in a gourd or some other vegetable to scare him away.

Sort of like the ritual that pruned him like a grapevine.

#pagan#polytheism#witchblr#witchcraft#witch#paganblr#canaan#canaanite paganism#levpag#levantine#paganism

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Deity Dagan

Originally a god of West Semitic speakers from the Levant, but worshipped widely throughout the Near East, including Mesopotamia.

Deity of grain, as well as its cultivation and storage. Indeed, the common word for "grain" in Ugaritic and Hebrew is dagan. According to one Sumerian tradition and to the much later Philo of Byblos, Dagan invented the plow. In the north, he was sometimes identified with Adad. Thus, he may have had some of the characteristics of a storm god. In one tradition his wife was Ishara, in another Salas, usually wife of Adad. Salas was originally a goddess of the Hurrians. Dagan also had netherworld connections. According to an Assyrian composition, he was a judge of the dead in the lower world, serving with Nergal and Misa-ru(m), the god of justice. A tradition going back at least to the fourth century BCE identified Dagan as a fish god, but it is almost certainly incorrect, presumably having been based upon a false etymology that interpreted the element "Dag" in Dagan as deriving from the Hebrew word dag "fish."

The earliest mentions of him come from texts that indicate that, in Early Dynastic times, Dagan was worshipped at Ebla. Dagan was taken into the Sumerian pantheon quite early as a minor god in the circle of Enlil at Nip-pur. Kings of the Old Akkadian peri-od, including Sargon and Narām-Sin, credited much of their success as conquerors to Dagan. Sargon recorded that he "prostrated (himself in prayer before Dagan in Tutul [sic]" (Oppen-heim, ANET: 268). At the same time, he gave to the god a large area of the country he had just conquered, including Mari, Ebla, and larmuti in western Syria. A number of letters from the Mari archives, dated mainly to the reign of Zimri-Lim, record that Dagãn was a source of divine revela-tion. The letters reported prophetic dreams, a number of which came from Dagan, conveyed by his prophets and ecstatics. In his law code, Hammu-rapi credits Dagan with helping him subdue settlements along the Euphrates.

The Assyrian king Samsi-Adad I commissioned a temple for him at Terqa, upstream from Mari, where funeral rites for the Mari Dynasty took place.

In the Old Babylonian period, kings of the Amorites erected temples for Dagan at Isin and Ur. In the Anzû(m) myth, Dagan was favorably coupled with Anu(m). At Ugarit Dagan was closely associated with, if not equated to, the supreme god El/I(u). Although he is mentioned in the mythic compositions of Ugarit as the father of the storm god Ba'lu/ Had(d)ad, Dagan plays only a very minor role. His popularity is indicated by his importance in offering and god lists, one of which places him third, after the two chief gods and before the active and powerful god Ba'lu/ Had(d)ad. Dagan is attested in Ugaritic theophoric names. In Ugaritic texts the god is often referred to as "Dagan of Tuttul." It might also be the case that one of the two major temples of the city of Ugarit was dedicated to him, and he might there have been identified with the chief god I(u) / El.

Festivals for Dagãn took place at Ter-ga and Tuttul, both of which were cult centers of the god. He was certainly worshipped at Ebla and also at Mari.

At Mari, in Old Babylonian times, he appears as fourth deity on a god list; that is, he was very important. He was venerated also at Emar. There a "Sacred Marriage" ritual between Dagan and the goddess Nin-kur was celebrated.

At the same city, a festival was held in honor of "Dagan-Lord-of-the-Cattle," at which the herds of cattle and prob. ably sheep were blessed.

According to the Hebrew Bible, Dagan was the national god of the Philistines. I Samuel:5-6 tells of the capture of the Ark of the Covenant by the Philistines. It was customary in the Ancient Near East for the conquerors to carry off the deity statues of the conquered to mark the surrender not only of the people, but also of their deities.

So the Philistines took the Ark, the symbol of the god of the Israelites, into the temple of Dagan at Ashdod. Since the Israelites had no statues of their deity, the much revered Ark was an obvious substitute. In this way, the Philistines marked the submission of the Israelite god to Dagan. However, on the next day, the people of Ashdod found the statue of Dagan lying face down in front of the Ark. The following day the same thing happened except that the head and hands of Dagan's statue lay broken on the temple threshold. This biblical account seems to be an etiology for a practice of the priests of the temple of Dagan at Ashdod, for it states that for this reason it is the custom of the priests of Dagan not to tread on the threshold as they enter the temple of Dagan. The best-known of the biblical stories that mention Dagan is in Judges 16, the tale of Samson and Delilah. After Delilah arranged for the Philistines of Gaza to capture Samson, they blinded him, shackled him, and made him a slave at a mill. During a festival to Dagan, the Philistines took Samson to be exhibited in Dagan's temple, where thou sands of Philistines had gathered for the celebrations. After praying to the Israelite god, the now long haired Samson got back his old strength. By pushing against two central pillars, he brought the temple crashing down on himself and on more Philistines than he had killed in his whole lifetime of killing Philistines.

— From a Handbook to Ancient Near Eastern Gods & Goddesses by Frayne & Stuckey page 67-69

#pagan#polytheism#levpag#philistines#israelites#canaanites#assyrians#1 samuel#tanakh#mesopotamians#dagan#dagan deity#deity#god#quote#sumerian polytheism#levant#ancient near east#landof2rivers#quote pile#put this in text for someone so thought id post it#eblaite#ebla

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lady Ashirat nurses Shahar and Shalim,

based on the Revadim Asherah figurine.

Prayer inspired by a water spout, yesterday:

O 𒀭Lady Ashirat of the Sea,

Thank You for water spouting up from the lively Earth,

Thank You for every green plant to nourish animals and humans;

Please protect me in all things, I place myself low in begging,

Watch over me as the ibex does her kid, attentive to their crying,

Banish all evil by the force of Your Horns;

Thank You for all wonder and beauty upon the Earth, Most Kindhearted 𒀭Lady Ashirat.

(Source)

#ancient near east#pagan#paganism#semitic pagan#semitic paganism#ancient history#ancient levant#polytheism#polytheist#bronze age#iron age#canaan#canaanite#canaanite pagan#canaanite paganism#canaanite polytheism#phoenicia#Phoenician#ugarit#ugaritic#ugaritic mythology#asherah#shahar and shalim#devotional art#devotion#prayer#faith#spirituality#religion#athirat

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

🐎Subtle Astarte Worship👑

Greatly inspired by @khaire-traveler's wonderful subtle worship series, which can be found here.

Learn self-defence, weapons included or not

Work on becoming more comfortable with the idea of conflict; it is only natural that we sometimes disagree with people

Learn about and uphold Ma'at

Make a playlist or listen to songs that remind you of her or you think she'd like

Make a collage/moodboard/pinterest board/similar collection of photos and images you associate with her, especially if some of the images are your own

Wear a piece of jewelry or other clothing item that reminds you of her

Light a candle or incense that reminds you of her (safely)

Carry a picture of her in your wallet, pocket, phone case, etc. or as a phone or computer wallpaper

Have horse, horns, chariot, lion, or dove imagry

Do something hard or challenging, especially if you've been putting it off, or it needs to get done

Make a list of your personal strengths and things you're proud of

Exercise a little, even if it's just stretching

Play combat-based video games

Allow yourself to express your anger and frustration; sit with and feel your feelings

Carry a protective charm

Get more comfortable with the idea that we don't get along with everyone; it's ok if someone doesn't like you

Learn how to ride a horse

Go stargazing

Support humanitarian organizations especially those that help parents or children

Show support for any parents or pregnant people in your life, especially new ones; help out when/if you can

Be kind to children; play with them if offered

Donate children and baby supplies to homeless shelters

Help out or mentor others, especially children

Picking up trash at a beach, lake, or river

Fall asleep/meditate to ocean sounds

Stand in water; ground yourself around bodies of water; meditate standing in or near them

Meditate at night; try to relax at night; sit in darkness silently for a bit

Get a telescope; use it to observe the stars

Get involved with your government (vote, go to local meetings, protest, write/call a leader, etc.)

Take charge/leadership roles in parts of your life

Learn about plants and animals, especially those that are native to your area or the areas she was worshiped

Learning how to safely forage for food, such as picking berries or mushrooms

Stand up for what you believe in; attend protests or activism events (be safe, please)

Learn to take pride in yourself; be your own role model

Learning about and practicing healthy conflict resolution skills

Educate yourself on your rights (legally); keep up to date on new bills and laws

Take care of your body physically to the best of your ability (shower, eat well, get a good amount of sleep, etc.)

Take your medications, if any; take medications as needed

Take care of a sick loved one or someone who is having a hard time

Learn about/research health conditions that you or your loved ones have; get a better understanding of these things

Clean anything you regularly interact with

Look into healthy coping skills for any anxiety, depression, trauma, etc. - anything that can improve your mental/emotional well-being

Learn about your healthcare options and medical rights (HIPPA in the US)

Donate blood

Set boundaries for yourself; I'll only give this much support to that person, I won't stay on my phone for hours before bed, I won't engage with this media that always upsets me, etc.

Although I am coming to this from a kemetic perspective, I have tried my best to research her so that this list is reflective of the many different places she was worshiped in and should hopefully be useful for those who worship her outside a kemetic context.

I may add more to this list in the future. Suggestions are always appreciated.

Link to the Kemetic Subtle Worship Masterpost

#kemetic polytheism#kemetic#kemetic paganism#kemetism#kemeticism#levpag#canaanite polytheism#canaanite paganism#subtle deity worship#Astarte#Ashtart#polytheism#pagan tips#deity worship#paganblr

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The funniest neopagan religion to found would be neopagan ancient Israelite religion (El and Yahweh as distinct deities, restoring the worship of Asherah, etc), since ancient authorities spent so much time trying to shift the Israelite flavor of Canaanite polytheism to a monotheistic footing. And because of the literary layers of the Hebrew bible and the rich archeology of the ancient Near East, you could probably cobble together something that was more historically informed than like Slavic or Celtic or even Norse neopaganism. It would also be fun to try to come up with a modern version of the one-god-for-every-nation scheme present in some parts of ancient Semitic cosmology. Maybe modern nations could inherit ancient gods, or maybe you could just treat major gods of various national myths as the guardian deities of each nation.

274 notes

·

View notes

Text

Baal Hadad, God of Storms and Fertility Stele from Tel Burna, Shephelah c. 1400 BCE Source: The Louvre

#baal#hadad#balu#haddu#canaan#canaanite#canaanite paganism#canaanite polytheism#canaanite gods#phoenician#phoenician paganism#phoenician polytheism#phoenician gods#aramean#aramean paganism#aramean polytheism#aramean gods#natib qadish#pagan#paganism#polytheism#magic#witchcraft#occult

128 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Jezebel

Jezebel (d. c. 842 BCE) was the Phoenician Princess of Sidon who married Ahab, King of Israel (r. c. 871 - c. 852 BCE) according to the biblical books of I and II Kings, where she is portrayed unfavorably as a conniving harlot who corrupts Israel and flaunts the commandments of God.

Her story is only known through the Bible (though recent archaeological evidence has confirmed her historicity) where she is depicted as the evil antagonist of Elijah, the prophet of the god Yahweh. The contests between Jezebel and Elijah are related as a battle for the religious future of the people of Israel as Jezebel encourages the native Canaanite polytheism and Elijah fights for the monotheistic vision of a single, all-powerful male god.

In the end, Elijah wins this battle as Jezebel is assassinated by her own guards, thrown from a palace window to the street below where she is eaten by dogs. Her death, the biblical authors note, was prophesied earlier by Elijah and is shown to have come to pass precisely according to his words and, so, in accord with the will of Elijah's god.

Her name has become synonymous with the concept of the evil seductress owing to the interpretation of some of her actions (such as putting on make-up in order to, allegedly, seduce her adversary Jehu, who is anointed by Elijah's successor, Elisha, to destroy her) and calling a woman a “jezebel” is to label her as sexually promiscuous and lacking in morals.

Recent scholarship, however, has tried to reverse this association and Jezebel is increasingly recognized as a strong woman who refused to abide by what she saw as the oppressive nature of her husband's religious culture and tried to change it.

Jezebel's Changing Reputation

The story as given in I and II Kings presents Jezebel as an evil influence from the moment of her arrival in Israel who corrupts her husband, the court, and the people by trying to impose her “godless” beliefs on the Chosen People of the one true god. I Kings 16: 30-33 presents King Ahab as a wicked king seduced by the corrupting influence of his new wife and is an audience's introduction to the story:

Ahab, son of Omri, did more evil in the eyes of the Lord than any of those before him. He not only , but he also married Jezebel, daughter of Ethbaal, king of the Sidonians, and began to serve Baal and worship him. He set up an altar for Baal in the temple of Baal that he built in Samaria. Ahab also made an Asherah pole and did more to arouse the anger of the Lord, the God of Israel, than did all the kings of Israel before him.

Traditionally, the story of Jezebel is one of a corrupting influence on a king who had already shown himself a poor representative of his kingdom's religious culture. The biblical account assumes a reader's knowledge that Jezebel, coming from Sidon, would have worshipped the god Baal and his consort Astarte along with many other deities and also assumes one would know that the polytheism of the Sidonians was comparable to that of the Canaanites prior to the rise of Israel and monotheism in their land. Since monotheism and the kingdom of Israel are presented in a positive light, Jezebel, Sidon, and Ahab are cast negatively.

It could be that the biblical narrative depicts events, more or less, accurately but this view is challenged by modern-day scholarship which increasingly leans toward a new interpretation of the clash between Jezebel and Elijah as demonstrating the conflict between polytheism and monotheism in the region during the 9th century BCE. In this interpretation, Jezebel is understood as a princess, the daughter of a king and priest, trying to maintain her cultural heritage in a foreign land against a religion she could not accept. The historian and biblical scholar Janet Howe Gaines comments:

For more than two thousand years, Jezebel has been saddled with a reputation as the bad girl of the Bible, the wickedest of women. This ancient queen has been denounced as a murderer, prostitute and enemy of God, and her name has been adopted for lingerie lines and World War II missiles alike. But just how depraved was Jezebel? In recent years, scholars have tried to reclaim the shadowy female figures whose tales are often only partially told in the Bible. (1)

Although she has been associated with seduction, depravity, and harlotry for centuries, a more accurate understanding of Jezebel emerges as one considers the possibility she was simply a woman who refused to submit to the religious beliefs and practices of her husband and his culture. The recent scholarship, which has led to a better understanding of the civilization of Phoenicia, the role of women, and the struggle of the adherents of the Hebrew god Yahweh for dominance over the older faith of the Canaanites, suggests a different, and more favorable, picture of Jezebel than the traditional understanding of her. The scholarly trend now is to consider the likely possibility she was a woman ahead of her time married into a culture whose religious class saw her as a formidable threat.

Continue reading...

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

✧ Introduction to Yahwism ✧

Yahwism is a iron age religion from the Isrealite tribe from before the existence of Israel. According to the story, the Israelites were saved from slavery in Egypt when the god, Yahweh, came to set them free. Yahweh had become the god of the Israelites. As the Israelites met the Canaanite tribe, they adopted the worship of the gods El and Ba'al along with the goddess Asherah. Asherah had been seen as being the consort of Yahweh. As time went on, prophets of Yahweh and the rest of the Israelites, began becoming unhappy with worshipping other gods along side Yahweh so they destroyed idols of Asherah and banned the worship of the other gods, though this did not completely stop the worship of them. The Israelites saw Yahweh as the only deity worth worshipping in their tribe so they abandoned polytheism but still being aware of the existence of the other gods. As time went on and Israel came to be, Judaism and Christianity branched off from Yahwism but Yahwism is absolutely NOT Judaism or Christianity. Yahwists only follow the teachings of the Tanakh (hebrew old testament) as it was the first bible. Yahwists do believe in Jesus but only as a prophet and only use his original name, Yahshua. Yahshua only said he was the son of Yahweh but as a metaphor for being a believer and follower.

Differences:

Yahwism

~ Focus is Yahweh and His holy spirit

~ Follows the Tanakh

~ Yahshua (Jesus) is only a prophet

~ There is no hell, either eternal life for the worthy or eternal oblivion for the non-worthy

~ Using the labels "God" or "Lord" is seen as disrespect as they are not Yahweh's name

Christianity

~ Believes in the holy trinity, Jesus is a form of God

~ Uses the labels "God" and "Lord"

~ Contains the new testament, which is Roman in origin

~ Believes in hell

~ Celebrates easter, christmas, etc.

~ Uses holy water and holy oil

~ Believes in judgement day

Judaism

~ Uses the labels "God" and "Lord"

~ Believes using the name "Yahweh" is disrespectful and too divine to be said

~ Not much focus on the afterlife, focus is life on earth

~ Follows the Tanakh

~ Celebrates chanukah

37 notes

·

View notes