#Camp Winnarainbow

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

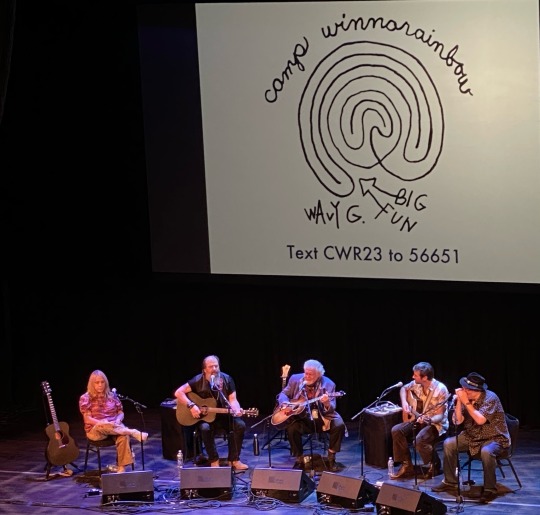

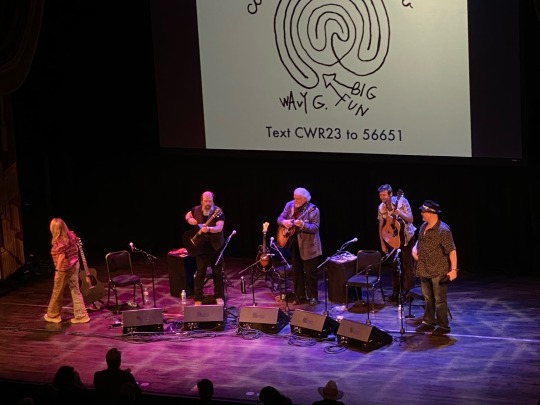

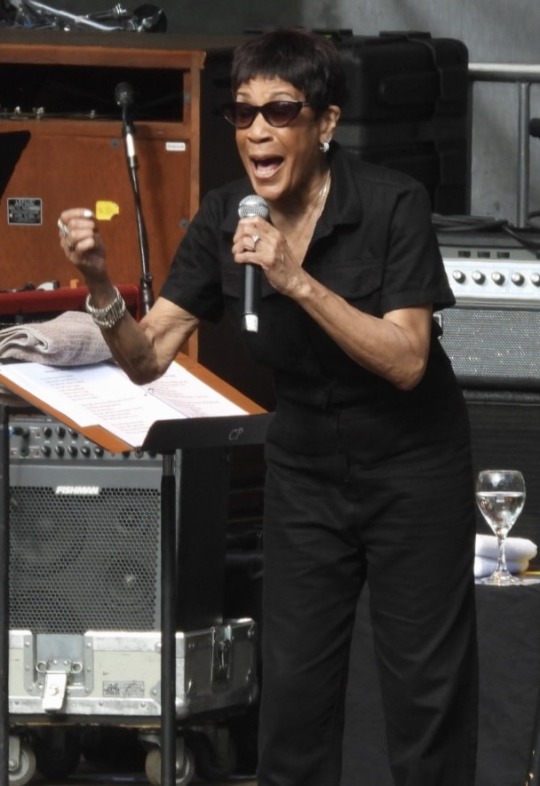

Toward the FUN(ds): A Concert Benefitting Camp Winnarainbow at Herbst Theatre, San Francisco, Sept. 28, 2023

- Steve Earle, Rickie Lee Jones, Peter Rowan, John Craigie and John Popper perform pre-Hardly Strictly Bluegrass benefit with Wavy Gravy in attendance

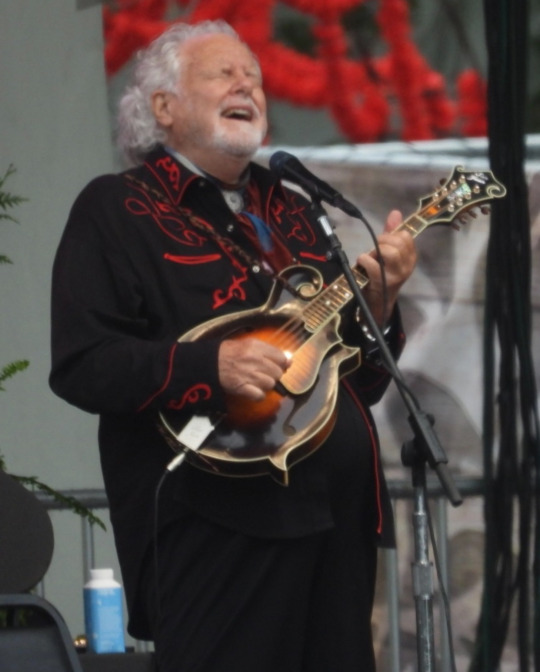

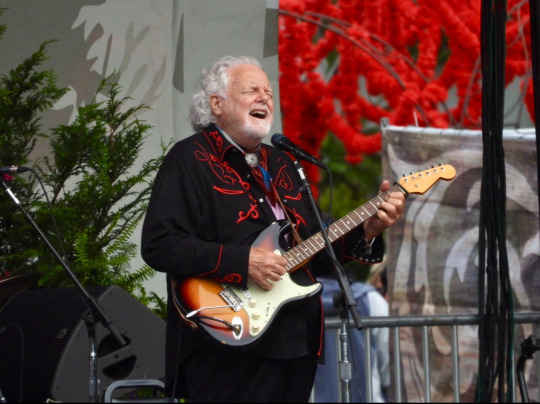

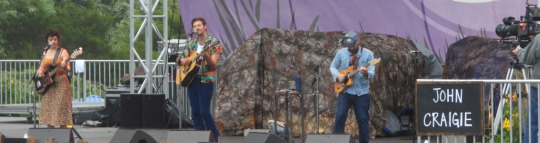

Seeing how they all were in town for separate appearances at Hardly Strictly Bluegrass, Steve Earle, Rickie Lee Jones, Peter Rowan and John Craigie got together and donated some time to a guitar (and mandolin) pull to benefit Wavy Gravy’s Camp Winnarainbow.

The round-robin performance is “an efficient way for a concert to raise funds … you get a lot of us for your buck,” host Earle told the crowd - which included Gravy, 87 and wearing his trademark clown nose, in the front row - assembled Sept. 28 for Toward the FUN(ds) at San Francisco’s Herbst Theatre.

This informal setting was an opportunity to hear Jones fumble through an untitled work-in-progress - “it’s like a lesson - a bad one,” she deadpanned mid-song - while earning the loudest applause of the evening for “Weasel and the White Boys Cool.”

“That usually happens to me when I host these things,” Earle said.

Jones would later wow the crowd by turning a false start of “Bury Me Under the Weeping Willow” into a singalong “Hand Me Down My Walking Cane.”

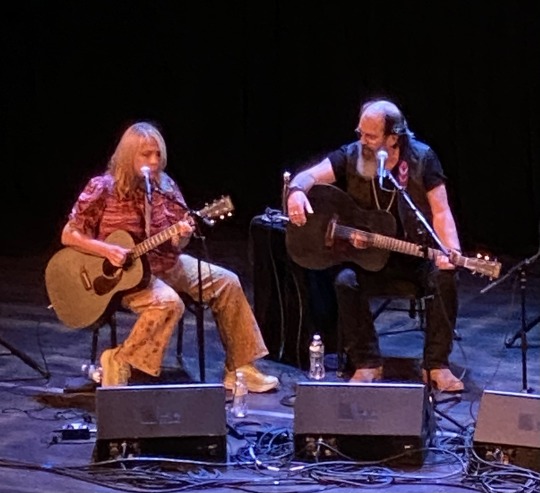

For his part, the host dedicated “Jerusalem” to Gravy, played mandolin on “Copperhead Road” and duetted with Rowan on “Train a Comin’.”

The incongruous grouping also found the 43-year-old California native Craigie - who was hysterical when talking about needing, and eventually quitting, oxygen when playing gigs at altitude - swapping licks with the 81-year-old Rowan, who played mandolin and guitar, sang high notes like a man half his age and slipped Elizabeth Cotten’s “Freight Train” inside his own “Panama Red.”

“Now my roots are really showing,” Rowan said upon playing the first notes of “Freight Train.”

Cragie’s songs, like his banter, can also be funny (as on “I Wrote Mr. Tambourine Man” and “Laurie Rolled Me a J”) before he slips into wistful homesickness on “I am California.” He punctuates both sides of his songwriting with mournful bleats on harmonica.

Unannounced guest John Popper, whose daughter attends the camp, appeared to perform a take of John Lennon’s “Imagine” with Craigie on guitar and participate in the all-hands-on-deck closer “Rivers of Babylon.” The Sour Widows Duo played an opening two-song set. But it was the four-way pull that pulled the crowd in and delivered huge payoffs during their 90-minutes on stage.

Grade card: Toward The FUN(ds): A Concert Benefitting Camp Winnarainbow at Herbst Theatre, San Francisco - 9/28/23 - A-

9/29/23

#toward the fun(ds)#2023 concerts#wavy gravy#camp winnarainbow#rickie lee jones#steve earle#peter rowan#old & in the way#john craigie#new riders of the purple sage#elizabeth cotten#sour widows#john popper#blues traveler#hardly strictly bluegrass#john lennon

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Peter Tork with the Sam Andrew Band (Snookie Flowers, Evette Williams, Sam Andrew, Bill Laymon, and Sharon White) in Laytonville, California on September 6, 1993. Photo 1 by J.C. Juanniss; all photos courtesy of billlaymon dot net, and samandrew dot com.

(Photo 4) “Peter Tork and Bill Laymon, and Snooky’s red hat, with The Sam Andrew Band at Wavy Gravy’s Camp Winnarainbow.” - samandrew dot com

“Almost without exception, every show I do, I get that this is what I’m here for.” - Peter Tork, The Daily Journal, October 21, 2009

#Peter Tork#1990s#Sam Andrews Band#Snookie Flowers#Evette Williams#Sam Andrew#Bill Laymon#Sharon White#1993#90s Tork#<3#Peter deserved better#Tork performances#Tork quotes#can you queue it

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

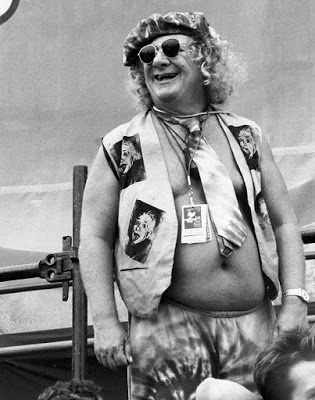

The battle for People’s Park has gone on for decades. I used to wander through in the 1990’s and meet colorful people. From Wikipedia: Wavy Gravy Hugh Nanton Romney Jr. (born May 15, 1936), known as Wavy Gravy, is an American entertainer and peace activist best known for his role at Woodstock, as well as for his hippie persona and countercultural beliefs. Romney has founded or co-founded several organizations, including the activist commune, the Hog Farm, and later, as Wavy Gravy, Camp Winnarainbow and the Seva Foundation. He founded the Phurst Church of Phun in the 1960s, a secret society of comics and clowns that aimed to support ending of the Vietnam War through political theater, and has adopted a clown persona in support of his political activism, and more generally as a form of entertainment work, including as the official clown of the Grateful Dead. As Wavy Gravy, he has had two radio shows on Sirius Satellite Radio's Jam On station. A documentary film based on his life, Saint Misbehavin': The Wavy Gravy Movie, was released in late 2010 to generally positive reviews. Romney was awarded the Kate Wolf Memorial Award by the World Folk Music Association in 1992.” Wavy Gravy at People’s Park, Berkeley, 1993 🇺🇦💔🌎💔🌏💔🌍💔🇺🇦 #earth #human #family #america #berkeley #park #peoplesparkberkeley #social #documentary #comic #performer #philosopher #portrait #photography @hasselblad #hasselblad #camera #mediumformat #fuji @fujifilm_northamerica #film #photography #filmisnotdead #istillshootfilm #pdx #portland #nw #northwest #leftcoast #oregon #streetphotography #ishootfujifilm @hasselbladculture @hasselbladfilmgallery @peoplesparkberkeley 1993 Fuji Reala Hasselblad 500c 120mm Makro-Planar https://www.instagram.com/p/CpSnx_RLWAg/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#earth#human#family#america#berkeley#park#peoplesparkberkeley#social#documentary#comic#performer#philosopher#portrait#photography#hasselblad#camera#mediumformat#fuji#film#filmisnotdead#istillshootfilm#pdx#portland#nw#northwest#leftcoast#oregon#streetphotography#ishootfujifilm

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's time for Beginnings, the podcast where writer and performer Andy Beckerman talks to the comedians, writers, filmmakers and musicians he admires about their earliest creative experiences and the numerous ways in which a creative life can unfold.

On today's episode, I talk to musicians Maia Sinaiko and Susanna Thomson, the founders and 2/3 of the Bay Area band Sour Widows. Originally meeting and becoming friends at Camp Winnarainbow in their youth, Maia and Susanna formed Sour Widows in 2017, when they found themselves living near one another for the first time. Eventually they invited drummer Max Edelman to join them in the band, and since then, they've released two fantastic EPs, a self-titled one in 2020 and Crossing Over in 2021. In 2023, they recorded their first full-length album Revival of a Friend at Tiny Telephone, and it will be released on Exploding In Sound Records at the end of the month!

I'm on Twitter here and you can get the show with:

Apple Podcasts

Spotify

Amazon Podcasts

YouTube Podcasts

Permalink RSS Feed Facebook

0 notes

Text

Chart-Topping Popstar Kendra & the Bunnies Releases “I’m A Showstopper (ft. AYO SK3TCH)

Pop singer/songwriter, recording artist and philanthropist Kendra & the Bunnies (Kendra Muecke) recently released her new hit single “I’m a Showstopper – Remix (ft. AYO SK3TCH),” surpassing 25K streams within the first week and landing coveted spots on several Spotify Editorial playlists. You can listen to the track HERE! With entertaining lyrics like jump into the crowd and let them catch me, born to put a show on if you ask me, “I’m a Showstopper” embodies the magical presence Kendra brings to the stage. You can watch the official music video HERE!”AYO SK3TCH and I linked up through the Los Angeles music scene,” Kendra explains. “We met each other at some mansion parties and had mutual friends, so we kept in contact. He invited me to a couple events and he came to see my band play. We always wanted to work together – we were just waiting for the right song. We’re both Showstoppers…I think one of our biggest similarities is that we are both working and grinding 24/7. It’s all about the music and a successful future!” In honor of her new single, Kendra has partnered with The Recording Academy’s MusiCares via Spotify’s Fan Support program. The non-profit organization offers preventive, emergency, and recovery programs to musicians in need. In June, the organization launched the Humans Of Hip Hop, providing resources tailored to hip-hop communities nationwide, focusing on eight cities: Atlanta, Chicago, Detroit, Los Angeles/Compton, New York, Oakland, Philadelphia, and Washington D.C. For more information, please visit www.musicares.org and click here if you’d like to make a contribution. Back in March of this year, People Magazine published an exclusive interview with Kendra, detailing the artist’s close encounter with a home intruder that stalked her and tried to assault her in the shower. This experience was the inspiration behind her song “Alive” on her EP “of all time.” About Kendra & the Bunnies: Kendra Muecke (BMI) of Kendra & the Bunnies is a freestyle rock-loving pop artist, singer-songwriter and multi-instrumentalist. Kendra has released numerous albums, EPs, and singles centered around the themes of self-love and shared understanding. With a combined total of over 206K followers on social media and over 1 million streams on Spotify, Kendra & the Bunnies has proven to be a fan-favorite in pop music. Atop her numerous releases, Kendra is very involved in The Recording Academy as a Grammy Voting Member, GRAMMY U mentor and GrammyNEXT member (2022), and she is on the Recording Academy Los Angeles Chapter Foundation Committee. In February 2023, Kendra spoke on a panel on behalf of The Recording Academy’s GRAMMY U program. The panel was held at Arizona State University alongside Jordin Sparks, Qiana Conley, and Randy Henderson. Kendra & the Bunnies is also a two-time Josie Music Award winner for Artist of the Year (Multi-Genre) in 2021 and Artist of the Year (Pop) in 2022. Kendra Muecke is a graduate of Pepperdine University (Bachelor of Fine Arts, Theatre Arts) and Musicians Institute (Independent Artist Program). Additionally, Kendra has studied songwriting at the Blair School of Music, Vanderbilt University. Kendra is known for wearing her heart on her sleeve and likes to volunteer with organizations benefiting community inclusion, addiction/recovery, and arts for children including: Strings For Hope (Nashville), Artists For Trauma (Los Angeles), Camp Winnarainbow (Northern California), Rex Foundation (National) and Smoke-free Music Cities (National). In her community, Kendra partners with the Junior League of Los Angeles as an active member advocating for foster youth and serves on the Public Policy Institute Committee. For more information, visit www.kendraandthebunnies.com and follow Kendra & the Bunnies on Instagram, TikTok, Facebook, Twitter, Threads, YouTube and Spotify. Read the full article

0 notes

Photo

* * * *

INTERVIEW: SAINT MISBEHAVIN’ WAVY GRAVY

by Richard Whittaker, Dec 21, 2010

One day I got a note from ServiceSpace founder, Nipun Mehta offering me tickets to a new documentary movie about Wavy Gravy. Would you like to go?

I went. Although I was aware of Wavy Gravy as a cultural icon, I really knew very little about him. The film is a eye-opener. Michelle Esrick’s loving documentary, Saint Misbehavin’ - 10 years in the making - is a real introduction to this remarkable man. I'd never heard about Hugh Romney, the man who later became famous as Wavy Gravy. And what a story. I'll mention just one of its surprises: earlier in his life, Hugh Romney was Lenny Bruce's manager.

A few weeks after seeing the film, at Mehta’s urging, I had the chance to interview Wavy Gravy himself.

Richard Whittaker: How are you feeling about Saint Misbehavin’?

Wavy Gravy: Oh, it’s a swell movie. I’m honored to be so well-documented, and the review in the New York Times was embarrassing. I’m not that good.

RW: You said in the film that you’re an “intuitive clown.” Would you mind saying something about what that means?

WG: I’m trained in the art of acting improvisation. That means acting on the spur of the moment rather than doing, say, the focused slow burn and all the traditional clown moves. I don’t do any of that.

RW: So that would be about sensing the moment, what’s there, and taking in who you’re with.

WG: Absolutely—and sensing what’s going on. I was, for a number of years, with The Committee in San Francisco. I taught improvisation at Columbia Pictures. Harrison Ford was one of my students and I’ve taught improvisation at Camp Winnarainbow for over thirty years.

RW: I wanted to ask you about your history. For instance, in New York in Greenwich Village, you wrote poetry, right?

WG: Yes I did.

RW: Is any of it available? And is it something you’d want people to find?

WG: There are a couple of slender volumes out there. I think you’d have to go to Amazon or eBay to find them. I don’t even have copies myself. But other people do and will lend them to me when I need them.

RW: Do any titles stand out for you?

WG: Kaleidoscope and there’s Joe’s Song, which is taught in a poetry class at the University of California at Berkeley. Would you like to hear it?

RW: Please.

WG: Okay. It goes like this: “Once upon and ever since I was a child in a child’s world. I have wept a child’s tears and built a child’s wall of clay and stone and colored years of poems in paint and virgin gold. I sought to build a wall so tall from lion eggs from Gallilee, a brick of song among the dregs of silver nails and lesser men a mile long to kiss the sun and climb again. Once ago and ever now I stood a man on a child’s wall. I stopped and prayed to spider webs and roses of the sea. I spoke as one with all the earth and knew the pain of birth and death to be the same without my wall. Once upon and ever furled I stand alone with all the world.”

RW: That’s beautiful.

WG: I wrote it in 1960 or about then. I don’t write lyric poems very often. These days I mainly write haiku, usually when friends pass away, which is happening more and more frequently from natural causes. Also I’ve been having the good fortune to have my art exhibited, and I do a haiku to go with each piece.

RW: I’m imagining that, as a younger man, you had certain visions and deep feelings that could have been a liability for living the conventional life.

WG: I don’t think I ever had to contend with that one [laughs]. I live in the land of one thing after another. [speaking with an east Indian accent] “The sand only goes through the hourglass one grain at a time,” as some Hindu sage proclaimed. I’ve discovered that to be true.

RW: Did you have mentors who supported you in Greenwich Village?

WG: It was kind of amusing. I was going to theater school at Boston University, which was an amazing theater school. The finest directors in the world would come in and the whole college would read for a part. A freshman could get a lead. It was extraordinary. And if you weren’t cast in the production, you would be cast in the lighting crew or the costume crew or the stage crew. Then there was an upset about theater students not doing their social studies and the university attempted to move the campus of the theater school over to where the rest of the university was laid out. Just at that time, the teachers who had all been hired during the McCarthy blackball because they couldn’t work on Broadway, well, the blackball ended and they all quit. They went to work at the Neighborhood Playhouse in New York City, and they took me with them.

But while I was at BU, I had read in Time Magazine about jazz and poetry in San Francisco. I thought, hey, I’ve written a couple of poems and I know some musicians. I can do that! So I got together with a bunch of artists from the museum school and we proceeded to take the basement of a bar called The Rock on Huntington Avenue. The place in the basement was called The Pebble in the Rock. We put in black tables and black clothes and mobiles and paintings and began doing jazz and poetry. It was the first jazz and poetry done on the East Coast. So I had the privilege of inaugurating the East Coast to jazz and poetry. I persisted in doing it for years in, of all places, Hartford Connecticut. On every Monday I would grab a bunch of musicians and go to Hartford and make substantial money. Otherwise I was going to the Neighborhood Playhouse and reading my poetry in the evenings at the Gaslight Café in Greenwich Village, as you saw in the movie.

RW: That’s an amazing story. There was another thing you said in the film, “put your good where it can do the most.”

WG: Which is the advice I gleaned from one of my mentors, the author and adventurer, Ken Kesey.

RW: Did that kind of focus something for you?

WG: Well, it lit up. It lit up. I had discovered that, somewhat. Whenever I would do a good thing, it made me feel good. I think I heard a preacher of color on television in the late fifties. He said, “It’s nice to be nice.” And that kind of hit a chord for me.

RW: Do you think there’s a mix in what artists do? That in your poetry, part of it was trying to give something?

WG: Hmmm, I don’t know. I was just trying to get out of the way and let whatever was inside of me come to the surface. In the early days, I was not all that consciously altruistic—although, in the early days of poetry, the poets were not paid. We used to pass a cornucopia around after an hour or so and people would put money in it. We made an embarrassing amount of money that way. Myself and Len Chandler, who was one of the first folk singers I brought into The Gaslight, he and I put on these capes with hoods—Len was an African-American and he had a motor scooter. And we would jump on the motor scooter at the end of the evening and drive down into the Bowery and find somebody passed out on the sidewalk. We’d stuff his pockets with money and drive off and find somebody else until we’d given away at least half of what we’d made in the course of the evening. It was a lot of fun.

RW: That’s incredible. What do you think led you to do that?

WG: I don’t know. It just seemed like a fun thing to do. We didn’t need all that money.

RW: Do you remember the moment when Ken Kesey said “Put your good where it will do the most good”?

WG: No. But he told me a lot of stuff—like, “You should honor your mother and your father.” This comes out of the Bible. As soon as I learned that Kesey had written that, I forget how he worded it, I immediately called my mother and my father and honored them verbally as best I could. And it was illuminating for them and for me. Afterwards, I called Ken up to thank him. He said, “Well, it’s just so darn simple.”

RW: I want to ask about giving and receiving. Do you have any thoughts in general, let’s say, about giving?

WG: Giving seems to be easy for me. Receiving is the thing I’m just beginning to learn how to do with grace. It’s a work in progress, like the rest of me. Over the last thirty years I’ve experienced considerable physical difficulty, having had to receive a series of spinal surgeries and spending amounts of time in body casts. You have no alternative, or you starve. So it was necessary. I tell people I learned patience in the hospital. [there’s a pause] That’s a pun.

RW: You’re right! [laughs]

WG: And as my infirmities persisted, I learned to acquiesce to the moment and accept, with as much graciousness as I could muster, the assistance of people who offered it.

RW: I bet this is true for lots of people, that it’s easier to give than to receive.

WG: Right, but as I pointed out, I didn’t have much choice, as with a lot of the stuff that has happened to me in my life. Life situations have presented themselves and it was either sink or swim.

RW: This reminds me of another part in the film. This is at Woodstock. You and the other members of The Hog Farm were brought there to be the police force for the whole event. You called yourselves “the please force.”

WG: We were the Please Force. And we had also set up what we called the Trip Tent.

RW: And there’s a part in the movie where you describe helping a young man who was having a bad acid trip.

WG: As he came in ranting, this three-hundred pound Australian doctor laid on top of him and said, “Body contact. You need body contact” [said with an accent] and then a psychiatrist leaned in and said, [using another funny voice] “Just think of your third eye, man.”

Then I figured it was time for me to make my move. I said, “Excuse me. I’d like to try something here.” And they all backed up. What’s this hippie going to do? That’s when I said, “What’s your name, man?”

RW: And he mumbled something…

WG: I said, “No, your name.” He told me his name and I said it back to him. In fact, I said it back to him several times.

RW: I noticed how very clear and emphatic you were when you got his name. “Okay, Bob. Bob, that’s your name.”

WG: Your name is Bob.

RW: Where did you get the knowledge of using that simple directness?

WG: We’d spent some time on the psychotropic frontiers through the prankster days and beyond. It was not unfamiliar territory.

RW: You knew something about being really concrete, and focused.

WG: And through the greatest professor of them all, professor experience; and from courses at hard knocks university.

RW: You’ve had a lot of hard knocks university experience, I think.

WG: Yes. Well, that’s how you learn things.

RW: You said in the film how you’d found you could get high without the psychotropic assistance. Could you say something about that again?

WG: There are many ways to alter space. I do lots of breathing exercises, and I do mantras. Different people have different recipes to get to a space of consciousness and then to dwell in it for as long as you can, I guess. My own way is an amalgam of many different practices from many different lineages.

RW: You evolved from Hugh Romney doing the poetry to where you were wearing a jester’s hat.

WG: Between poems I used to talk about the bizarre things that happened to me during the day because it was really tedious just reading all these poems night after night after night. Then a guy came along and said, look, skip the poetry. Just talk about your bizarre experiences. That’s how I got into doing stand-up.

Lenny Bruce became my manager. I put out a couple of albums and toured the U.S. —and in fact, something of the world—doing stand-up before these other things came along.

RW: Somewhere you left the jester’s hat and started dressing as a clown.

WG: I was asked, when we had moved to Berkeley in the mid-seventies, to go the Children’s Hospital in Oakland and cheer up kids. On the way out the door of my house, someone handed me a red, rubber nose. I discovered it enabled me to get out of myself and be entertaining to the kids. After awhile, I began to paint my face up as a clown. Somebody gave me a costume, and a clown who was retiring from Ringling Brothers gave me his giant shoes. I worked with kids, with kids who were terminal, even, and did this almost every day for about seven years.

At one point I had to go to a political rally at Peoples’ Park and I didn’t have time to take off my clown stuff. I discovered that the police didn’t want to hit me anymore. Clowns are safe.

RW: Can you say more about what your experience at Children’s Hospital working with kids was like?

WG: I discovered that not only was I helping the kids, I was helping myself. As I began to do this work, I’d gone through three major back surgeries and was in quite a bit of pain. But working with the kids I discovered that as I focused on the children and the pain they were in, I lost track of my own pain.

RW: Is the clown an archetype you can inhabit?

WG: Sure.

RW: Do you think, “I’m a clown?”

WG: I don’t know. I can’t see you.

RW: [laughs] No. I have a long way to go. If I evolved, I might become a clown.

WG: Well, you need to go to camp Winnarainbow. They’ll teach you to clown. It’d be good for you. I think John Townsend said it most brilliantly in The Book of the Clown, “A clown is a poet who is also an orangutan.” But clown comes from the word “clod” or bumpkin, and the red nose indicates they were drunk. But I found all this out later. Suddenly I have these big shoes on and [laughs] a nose and I’m painting my face up, and where does it all come from? I began to study it, and it’s very fascinating, the path of the clown and the jester.

RW: What have you found out about being a clown? What has been revealed?

WG: It enables me to go places I couldn’t go as a regular kind of guy. People feel challenged by people going where I go. But when I put on the patina of a clown I’m no challenge to them in any way.

RW: What do you wish for people when you become a clown?

WG: I wish that they would find joy in the moment. It’s like I expressed in the film, laughter is the valve on the pressure cooker of life. Either you laugh at stuff or you’re going to end up with your beans on the ceiling.

RW: At camp Winnarainbow in the film it showed the labyrinth you have on the grounds…

WG: It’s a unicursal Cretan labyrinth. The oldest one is 3000 years old and was found on the island of Sardinia. The more common labyrinth, like the one you see at Grace Cathedral came about during the 11th or 12th century when Europeans could not go to Jerusalem on pilgrimage. So they developed this other labyrinth, which is different from the Pagan labyrinth, which made it to Scandanavia, to India and somehow to Peru and to the sun temple at Mesa Verde. That’s where I first encountered it when I spent time living with the Hopi Indians for a few months.

RW: How did that happen?

WG: I was enamored of the Book of the Hopi by Frank Waters. And that’s where I first saw the labyrinth. According to the Hopi if there was a condition of planetary emergency the different races would gather on this mesa for instruction from the spirit world. So I showed up. They said, “You’re pretty early.” But they took pity on me and I got to hang out with them for a while.

RW: Was anything given to you?

WG: Not something that I would feel comfortable talking about, but yes—not so much from the people as from the geography.

RW: So you brought this labyrinth to camp Winnarainbow, then?

WG: Yes. I asked Minalanska, who was an elder, what that was. She said, “Oh Wavy Gravy, that’s just the master plan of the universe.” So I borrowed a pencil and wrote it down, and I’ve brought it everywhere I’ve gone ever since. I learned to draw it. Even with my first book, I’d sign it and draw that labyrinth.

RW: Now how do you make use of the labyrinth at camp for the kids?

WG: A teepee at a time, in the evening, the campers get to walk the labyrinth to beautiful music under the stars. If they do good things, they get strokes. If they do bad things they get strikes. Three strikes and you’re out. You can always work off strikes, but you can get enough strikes to be sent home, too. By doing things above and beyond the ordinary camper—for instance, if you get eight stokes in a two-week session, you get to walk into the center of the labyrinth. In the center, there’s also these crystals. You get to take a crystal out of the labyrinth and take it home.

RW: Do you talk to the kids about the labyrinth?

WG: Oh, sure.

RW: What do you tell them?

WG: I tell them that the labyrinth is not a maze. Mazes are designed to get you lost. Labyrinths are designed to get you found. And I ask them to think of each step as a prayer for peace. I tell them you go into the labyrinth and that there’s an energy in the center that I call the spirit of Gaia, the earth mother. I say that if you have cares or problems you can leave them in the labyrinth and come out perhaps lighter than when you went in. And that is sometimes helpful to young people.

RW: In the film you made a comment to one kid that the labyrinth is inside of you.

WG: Oh, I tell all the kids that. The true labyrinth is inside you.

RW: That’s powerful. From the film, I see that your life has been a journey. Do you feel it that way?

WG: Absolutely. It’s been a great adventure.

RW: What are some of the changes from where you were and where you are today?

WG: The things that are the most significant for me in my life are the circus and performing arts camp that I’ve run with my wife Jahanara for over thirty years. We do nine weeks for kids and one week for grown-ups. And the Seva Foundation is another. Through it I’m able to raise funds to help the blind regain their sight. Eighty percent of the blind people in the world don’t need to be—they can get their sight back.

When we first started doing the work it was about five dollars for a cataract operation. Now it’s close to fifty dollars for the operation in third world countries. If you go to SEVA.org you can find out all about us. We’ve helped to orchestrate—it’s going on three million sight-saving operations. I get to put on concerts to raise funds to do that. I’m going to be seventy-five years old in May and I’m looking forward to doing a concert in the Bay Area at the Craneway Pavillion in Richmond and in New York City at the Beacon Theater. And also I’m facing another basic spinal surgery in January. So I’ve got a lot of stuff on my plate.

RW: I know we don’t have much more time, but …

WG: Eternity now, I always say. That’s one of my favorite quotes. And we’re all the same person trying to shakes hands with our self. I think that’s a good one, too.

RW: I like those quotes. It’s clear that you’ve spent a lot of time doing forms of service. Camp Winnarainbow seems to be a service.

WG: Well, my greatest legacy is the children that have come out of camp over the last thirty years. Lots of the kids who started camp when they were seven are now running the camp. And I’m sure it will go on long after I’m gone.

RW: Is that something one begins to learn, that the deepest gifts come when one can look beyond personal wants to take in the needs of others?

WG: That is my want! [laughs] Put your good where it will do the most. I can’t say it any better.

[WORKS AND CONVERSATIONS]

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Reposted from @moped.outlaws Hello Summer, episode 53, is now... LIVE!! #linkinbio👆👆 This episode starts with 1/2 the hosts present... due to technical difficulties. But, we are off and running with talk about Robyn's trip to Asia and our listeners being multi-dimensional time-travelers. There's the beginning of summer, Juneteenth a lot of talk about the film, Hustle. Great film! Lotsa spoilers... And we end with our summer camp experiences - and blue russians. The dude abides. #mopedoutlaws #enjoy (at Camp Winnarainbow) https://www.instagram.com/p/CfB15aILJgF/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Photo

Snippet from “Spy Rock Memories” by Larry Livermore (about Camp Winnarainbow, a kids performing arts camp)

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pitchfork review of: Electric on the Eel ~ Jerry Garcia Band ~ By Jess Jarnow

A new six-disc box set featuring performances from the late ‘80s and early ‘90s offers the definitive document of the latter-day Jerry Garcia Band.

One way to find Jerry Garcia the last weekend of August 1987 was to open an issue of Billboard, where Garcia and the Grateful Dead lingered on both the singles and albums charts. The MTV-assisted hit “Touch of Grey” peaked at No.9, while parent album In the Dark climbed to No. 6—the only two Top 10 hits of the Dead’s career. Another way to find Garcia that same weekend was to pack the car and drive three-and-a-half hours north of San Francisco, deep into the Emerald Triangle, northern California’s much-contested cannabis-growing region, until Route 101 ran along the Eel River. There, at a secluded spot known as French’s Camp, Jerry Garcia and his long-running Jerry Garcia Band jammed on a simple tapestry-draped stage while naked hippies frolicked in the water, a benefit for Wavy Gravy’s Camp Winnarainbow.

A new box set, Electric on the Eel, captures the Jerry Garcia Band on their three visits to the idyllic French’s Camp in 1987, 1989, and 1991. They show Jerry Garcia at both the height of his fame and simultaneously escaping into his not-so-secret identity: himself. Since 1970, Garcia had played outside the Dead in various musical guises, hiding in plain sight at regular no-name jam sessions in Bay Area clubs that—with bassist John Kahn—consolidated into the Jerry Garcia Band by 1975. Though the Garcia Band would remain most at home playing in dark bars, they also became an outlet for the kind of laid-back musical opportunities the Dead could no longer accommodate, like playing for a few thousand hippies in the summer sunshine while Wavy Gravy MCed.

In more ways than one, The Jerry Garcia Band functioned as an escape hatch from the creative and financial chaos of the Grateful Dead—Kahn, Garcia’s frequent musical second-in-command outside the Dead, also served as Garcia’s longtime drug buddy. In the summer of 1986, Garcia fell into a diabetic coma and nearly died. Years of addiction and ill health had taken their toll, and when he came to, he had to relearn how to play guitar. When he took the stage again, in decent health for the first time in nearly a decade, he had a new sense of agency and purpose. You can hear that ravaged clarity even in these low-key sessions.

As Electric on the Eel documents, the Jerry Garcia Band was as unpretentious as the Grateful Dead were convoluted. With the repertoire of a deep bar act, they were a platform for Garcia’s endless guitar variations over a more straightforward rhythm section, plus backup singers to support Garcia’s scarred voice. It is uncomplicated and often sweet, lying at the blurry intersection of rock, R&B, Motown, and gospel, cushioned by the enveloping warmth of Melvin Seals’ Hammond organ and Gloria Jones and Jacklyn LaBranch’s backing vocals. It is music intended for dancing or, at least, feeling good.

The box set dips into Garcia’s bag of trusted extra-Dead originals, including 1982’s charging “Run For the Roses,” 1976’s redemptive “Mission in the Rain,” and 1977’s apocalyptic “Gomorrah.” But most of Electric on the Eel is devoted to a songbook of covers in the emerging jam-band vernacular that Garcia was helping to define. Among the 31 different songs on Electric on the Eel, more than a dozen were new to the songbook since Garcia’s coma, including Bruce Cockburn’s “Waiting For A Miracle,” which became a late-career staple, and “Twilight,” a pining and lonesome deep cut by The Band. Garcia’s voice is especially strong and confident on crisp versions of Los Lobos’s “Evangeline” from 1987 and 1989, neither version cracking four minutes, both bouncing like the streamlined early ‘70s Dead.

Garcia’s vocals, despite ample wear and tear, are in arguably the best shape of his later years. Nearly every track is a sterling example of how someone with a damaged voice can also be an incredible singer. Scratched from years of cigarettes and freebasing Persian heroin, Garcia’s voice flutters and shakes. He doesn’t always sustain notes or land on the right pitch. Sometimes, he transposes verses or forgets lyrics. And yet, his singing is as much a reason to listen to Electric on the Eel as his guitar playing, both filled with a rejuvenating brightness mirrored in Melvin Seals’ buoyant organ, and capable of clarity, articulation, and even power. Garcia had been singing spirituals since his folkie days in the early ‘60s, but—in its post-coma return—his voice finds more grace than ever.

Of course, every track makes its way to the inevitable guitar solo. “I’ll take a simple C to G and feel brand new about it,” Garcia sings on a cover of Allen Toussaint’s “I’ll Take a Melody,” perhaps a rare bit of boasting on Garcia’s part. A staple of his solo shows since the early ’70s, it’s also a song that became his own, in part through his brilliant variations on it. To those tuned in, Garcia’s guitar could unlock the language of the cosmos even on generic bar fodder like Eric Clapton’s “Lay Down Sally.” When Garcia was tuned out, though, as he was for much of the early ‘80s, it could also sound closer to a musical screensaver. By 1987, Garcia’s playing and singing had both regained their former urgency, the cosmos once again within reach.

Compared to the languid Garcia Band extravaganzas of the ’70s, the Electric on the Eel shows are fairly concise. There is one excellent exploratory jam—a 14-minute “Don’t Let Go” from 1989—but most performances fall under the 10-minute mark. Anchored by drummer David Kemper, who once described the band’s particular groove as simultaneously “having the foot on the gas pedal and foot on the brakes,” the band is flexible and easy, sliding with Garcia as his improvisations stretch.

Most of the music on Electric on the Eel has only circulated as fan-made audience tapes, so these recordings will provide upgrades for deeper heads. But the scope of the set is also a fine way for the Jerry-curious to take a deeper dive into what many consider to be the Garcia Band’s golden period. For some Deadheads, as for Jerry Garcia himself, the Jerry Garcia Band became their own escape from the Dead, and Electric on the Eel shows why, moving with a lightness the Dead had long since lost. Its six discs are both a comprehensive document of the group’s penultimate lineup and a fine introduction to the Jerry Garcia Band at their best, music to make the hassles disappear.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Day No. 1, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, Sept. 29, 2023

- Rickie Lee Jones, Christone “Kingfish” Ingram, John Cragie, Peter Rowan and others highlight first day

Rickie Lee Jones opened the 2023 edition of Hardly Strictly Bluegrass - and christened the festival’s new, Horseshoe Hill stage - by reading from her 2021 memoir.

And Peter Rowan played country - not bluegrass - music during his late-afternoon set on the Banjo stage.

These were just two highlights from Day One at the long-running festival, which also included Christone “Kingfish” Ingram redefining the blues and John Craigie finding his quirky spot alongside Todd Snider in folk-Americana.

Seated on the small stage set up to resemble a living room and flanked with clothes drying on the line, an animated Jones embellished her reading from “Last Chance Texaco” with playful asides and wise cracks. She talked about how Laura Nyro made her feel connected and how Neil Young made her realize odd voices can be successful voices.

“I like it up here,” Jones said of being on stage. “I think artists sometime mistake the excitement for fear.”

Jones read about hitchhiking through California as a 14-year-old in 1969 as a foggy drizzle enveloped Golden Gate Park. She had soundchecked with a snippet of “The Horses,” but ended her well-received spoken-word gig by playing her father’s composition “The Moon is Made of Gold” solo and acoustic and earning a standing ovation from the small crowd seated in grass surrounded by tall trees.

Afterward, Mr. and Mrs. Sound Bites took in a couple of numbers from Vetiver - think the Byrds with a slide guitarist - on the Swan stage as the blog couple headed for Ingram, who played before an audience of thousands on the Towers of Gold stage.

Borrowing Stevie Ray Vaughan’s tone and adding equal measures of funk and R&B, Ingram and his band were super-charged during 50 minutes of electrifying blues as they continually tore the music down before building it right back up. The guitarist sang of lost love on “Fresh Out;” walked off stage, but kept playing out of sight, to showcase his band on “Not Gonna Lie;” and engaged powerful call-and-response with his keyboardist during the set, which ended as Craigie took to the adjacent Swan stage.

Backed by electric bass and guitar and playing acoustic axe and harmonica, Craigie mixed humorous stage banter with tunes both playful (“I Wrote Mr. Tambourine Man”) and serious (“I am California”). Stage presence and song craft made fans of the Sound Biteses, who got their second dose of Craigie in as many days following the previous evening’s benefit for Camp Winnarainbow.

Bluegrass legend Rowan was the biggest surprise of the day, turning in a country and blues set that found him alternating between electric guitar and mandolin, supported by guitar, bass, drums and fiddle. This was exhilarating, though low volume at the Banjo stage lessened the impact of the instrumental guitar duel of “T Bone Shuffle” and made “Panama Red” -> “Freight Train” -> “Panama Red” sound like they were coming in on the winds from Ocean Beach.

Small price to pay for the opportunity to hear Rowan perform such warhorses as “Lonesome L.A. Cowboy,” “Land of the Najavo” and “Midnight Moonlight” in novel musical settings in the bucolic landscape of Golden Gate Park.

9/30/23

#hardly strictly bluegrass#2023 concerts#rickie lee jones#last chance texaco#john cragie#peter rowan#old & in the way#christone kingfish ingram#vetiver#laura nyro#neil young#stevie ray vaughan

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Celebrating #campwinnarainbow founder #wavygravy with @jacoblife100 @bobweir @benandjerrys #winnarainbow2017 (at Camp Winnarainbow)

0 notes

Photo

* * * * *

Of course I’d heard of Wavy Gravy.

He was one of the icons of the 1960s psychedelic counterculture and had played an inspired role at one its iconic events, Woodstock. But I knew very little about this amazing man. That changed when I found myself at the San Francisco premiere of Michelle Esrick’s loving documentary of Wavy Gravy, "Saint Misbehavin’".

I learned that the life of Hugh Romney (he was nicknamed Wavy Gravy by B.B. King) has been one of increasingly conscious service for the greater good—in the humble guise of a clown and in service to children in hospitals and at his camp Winnarainbow. Human beings are built for service, I’ve heard Jacob Needleman say. But how do we find ways to serve in the midst of our lives of striving and getting? A few days after Esrick’s film debuted in San Francisco, I spoke with Wavy and learned about the way of a beloved hippie trickster, gently challenging the status quo. Richard Whittaker: I’m imagining that, as a younger person, you had certain visions and deep feelings that could have been a liability for living the conventional life. Wavy Gravy: I don’t think I ever had to contend with that one. I live in the land of one thing after another. “The sand only goes through the hourglass one grain at a time,” as some Hindu sage proclaimed. I’ve discovered that to be true. MORE

[He was always striving to be “the best Wavy I could muster”. The story of how he got his name.

“At the 1969 Texas International Pop Festival Romney was lying onstage, exhausted after spending hours trying to get festival-goers to put their clothes back on, when it was announced that B.B. King was going to play. Romney began to get up; a hand appeared on his shoulder. It was B.B. King, who asked, "Are you wavy gravy?" to which Romney replied "Yes." "It's OK; I can work around you," said B.B. King, and he and Johnny Winter proceeded to jam for hours after that. Romney said he considered this a mystical event, and assumed Wavy Gravy as his legal name.”]

[via alive on all channels]

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bob Weir and RatDog - Reunion for #WavyGravy82 Streaming Live Now from the Sweetwater

Bob Weir and RatDog – Reunion for #WavyGravy82 Streaming Live Now from the Sweetwater

Steve Kimock & Friends – A Celebration of Wavy Gravy’s 82nd Birthday with Proceeds Benefiting Camp Winnarainbow at Sweetwater Music Hall

Bob Weir, Steve Kimock, Jeff Chimenti, Jay Lane, Robin Sylvester = RatDog!

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Sound Bites Presents: The Best of Hardly Strictly Bluegrass 2023

Editor’s Note: the 2023 edition of Hardly Strictly Bluegrass ended one week ago today. Having returned to backward Oiho after a glorious three days in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, the blog recounts his favorite sets of the festival. Read Sound Bites’ full coverage here, here and here; and see more photos here, here and here.

Rickie Lee Jones - Horseshoe Hill stage, Sept. 29; Banjo stage, Sept. 30: Given 45 minutes for her festival-opening reading from “Last Chance Texaco” and another hour for music the following day, when she played the titular song from her 2021 memoir, Jones got more stage time than any other performer. And she put it to good use. After sound-checking with a snippet of “The Horses,” a high-spirited Jones read excerpts about her time as a 14-year-old hitchhiker in California and how her admiration of the hippie ideal eventually turned into contempt. She closed the session by playing a solo-acoustic version of “The Moon is Made of Gold,” a song written by her father.

The following afternoon, Jones and her band played to a ginormous crowd - “I haven’t seen so many people in front of me for so long,” she said, clearly enjoying the moment. Crooning at the mic on “One More for the Road;” playing guitar on a New Orleanian rearrangement of “Danny’s All Star Joint;” sitting at the piano for “We Belong Together;” and playing banjo on an untitled work-in-progress she had unveiled two nights earlier on guitar at the benefit for Camp Winnarainbow, Jones was effervescent and as appreciative of her audience as they were of her. Sound Bites obviously doesn’t know Jones, yet it made him so happy to see her so happy over the three days of performances he and Mrs. Sound Bites witnessed. Rickie Lee, gold.

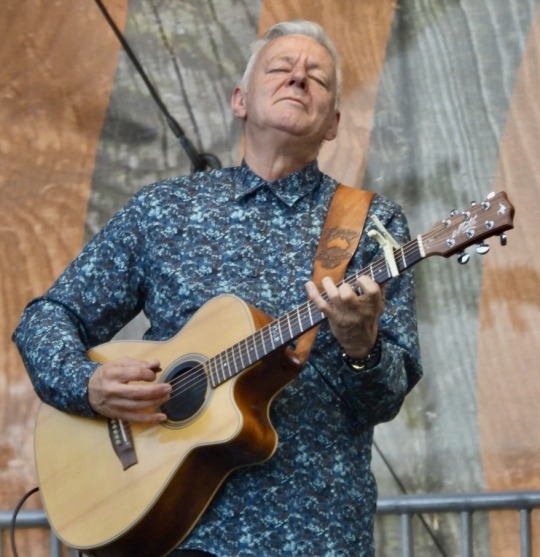

Tommy Emmanuel - Arrow stage, Oct. 1 - Allotted a criminally stingy 50 minutes, Emmanuel was the only solo-acoustic act to make an audience stop talking and simply gasp at what they were hearing and seeing. That’s because he is a band unto himself and he introduced his phantom accompanists while playing bassline, percussion, rhythm and lead simultaneously on his acoustic guitar. “Sixteen Tons” and “Nine-Pound Hammer” found Emmanuel singing; “Imagine” was instrumental save for the audience and the guitarist’s famous, inhuman “Beatles Medley” closed the set, which should’ve run an hour.

Eilen Jewell - Rooster stage, Oct. 1 - Playing songs from her pre- and post-pandemic albums, Gypsy and Get Behind the Wheel, respectively, Jewell was positively enthralling during her 45-minute midday set, which wrapped with a near carbon-copy of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Green River,” allowing secret-sauce guitarist Jerry Miller to shine.

Christone “Kingfish” Ingram - Towers of Gold stage, Sept. 29 - At 24, Ingram sounds like he’s been playing guitar for 50 years already. This up-and-coming bluesman is going to be a huge star and he spent his 50 minutes demonstrating why he may very well be thought of in 2073 in the same way Buddy Guy is today.

The Travelin’ McCourys - Banjo stage, Oct. 1 - With Punch Brother Noam Pikelny filling in for Rob McCoury on banjo, the sons of Del played some of the least-Hardly Strictly music of the entire festival, as a large swath of the audience bounced along in unison while the band smoked a bluegrass “Scarlet Begonias” in the park the Grateful Dead filled with music so many times in the days of yore. “Seems appropriate,” Ronnie McCoury said.

Doc Watson Tribute - Horseshoe Hill stage, Oct. 1 - Joined at various points by Andrew Marlin, Valerie June and Jon Langford, Mitch Greenhill, Nora Brown and Stephanie Coleman offered an intimate set that included “Summertime,” “Handsome Molly” and “Tom Dooley” among others. It all ended with the life-affirming experience of a couple of hundred people singing “Keep on the Sunny Side” under a canopy of trees in a light afternoon fog.

Bettye LaVette - Rooster stage, Sept. 30 - At 77, LaVette remains a powerful performer, stalking the stage and employing her raspy voice to great effect. Bob Dylan may have written “Things Have Changed,” but LaVette owns it.

Irma Thomas - Rooster stage, Sept. 30 - Thomas, 82, played HSB’s most-rambunctious set, closing Saturday with a barnburner that reached its apex with “I Done Got Over It” -> “Iko Iko” -> “Hey Pocky Way” -> “I Done Got Over It.”

Honorable mention: The McCrary Sisters - Rooster stage, Sept. 30 - Rather than a full performance, which they merited, the McCrarys played a handful of five- to 15-minute spots that included uplifting renditions of Stevie Wonder’s “Higher Ground” and “Amazing Grace.”

10/8/23

#hardly strictly bluegrass#rickie lee jones#tommy emmanuel#eilen jewell#the travelin’ mccourys#doc watson#the mccrary sisters#irma thomas#bettye lavette#christone kingfish ingram#2023 concerts

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

My only safe haven

#laybrinth#camp#cwr#winnarainbiw#camp winnarainbow#crystals#wavy gravy#northern california#laytonville#sisters and brothers#love#comfort

10 notes

·

View notes