#Bloody Sam Peckinpah

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"BLOODY SAM" ON THE GRIM REALITY OF KILLING -- A WARNING TO THE REST OF US.

PIC(S) INFO: Spotlight on assorted film stills from the bloody conclusion of the American epic revisionist Western "The Wild Bunch" (1969), directed and co-written by Sam Peckinpah. Warner Bros.-Seven Arts.

“… killing a man isn’t clean and quick and simple. It’s bloody and awful. And maybe if enough people come to realize that shooting somebody isn’t just fun and games, maybe we’ll get somewhere.”

— SAM PECKINPAH (American film director/screenwriter/cinema iconoclast)

Sources: Britannica, Film Comment, Newsweek, Pinterest, Alchetron, Slash Film, various, etc...

#Sam Peckinpah#Epic Revisionist Western#David Samuel Peckinpah#Western Movies!#Violence in Movies#Sixties#1969#Western#The Wild Bunch 1969 Movie#Bloody Sam#Bloody Sam Peckinpah#Movie Stills#Cinema#Americana#Western Movies#Wild Bunch#The Wild Bunch Movie#Cinematography#Film Stills#60s Cinema#Revisionist Western#Samuel Peckinpah#Gun Violence#Westerns#The Wild Bunch 1969#American Style#1960s#Film Director

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Planet of the Apes (1968) : Movietalk # 05

This came out the same year as 2001: A Space Odyssey. Think about that. Two of the biggest, most highly influential pieces of American science fiction ever produced came out within a few months’ span of each other, and both of them just so happened to be evolved from involve apes. Between this and King Kong I believe Hanuman must’ve been watching over us all along, but this thought goes even further than that (though I will not forget to praise thee, o sweet sweet divine one). That Kubrick’s film, among its many frightening, man-dwarfing cosmic mysteries – created in part by a visionary often seen as more a cold, clinical, and sometimes even cynical type than he was anything resembling warmth – turned out to be one of the most life-affirming, optimistic and spiritually humorous films about humankind’s potential in space and beyond was certainly one thing… and it was quite another it would seem but a major exception at the time compared to this, a film which, with its strong and bitter nihilistic revelations, would not only influence a whole array of other dystopian downers to come (Logan’s Run, Soylent Green, A Boy and His Dog, Damnation Alley, just to name a few) but would also – if it still can be believed – spark an entire franchise (!!!) with the ongoing premise of humankind’s fallacies ever making way for the Ascension of the Great Apes and their Reign on Earth As It Was and As It Shall Ever Be under the banners of Great Ape Heaven.

But then again it was 1968, and America was far from its best (if it could ever be said it had one): we were committing massacres overseas, performing assassinations way back home, and in the midst of all the brutality and protests as the result we would then choose to elect the worst (now second-worst) most possible mound of despicable flesh to ever remain an infamous cancer in the public eye of the planet as president. With all that bad mojo going around it was no surprise that even the westerns had started to get the blues; how did noted director Sam Peckinpah become “Bloody Sam” Kill-em-all Peckinpah all the sudden? Well…

Perhaps what could best be said is that even in fiction we can’t let a good conflict down; hell, even when the American public had decided it was done making itself feel even more down in the dumps by watching another nuclear war apocalypse and instead went in droves to watch this really far-out pulp-tastic space fantasy that just came out, they still inevitably chose to watch a war movie. Yet that could also be further explained by the fact that this time, the good guys were gonna win (oh yes! you betcha ass!) the good guys were gonna take out the oppressive empire, impress the cute girl, and get a gold medal they could chew on the way back home in one fell swoop. After all, it’s always the easiest to withstand any conflict – no matter how devastating or horrific – as long as you know right away the cards will always be held in your favor: things may be tense at times (a bit iffy, a little bumpy, to put it lightly) but at least there would be the certainty they’ll get the job done and get it done right so you could rest at ease to tell your friends all about it over brunch the next day. But that’s just the movies, and because it’s the movies these things often turn themselves back around even when unintended. I guess I was always curious why they called it Star Wars in the first place when they were like, waging one? Now we don’t have to be concerned anymore. We don’t have to worry.

Of course, you could possibly lead this to an argument about how most of these films and TV shows and whatnot of the Kenner ilk have more or less this hopeful spin, this liberating message of persistence and collective strength against the great powers that be assigned to kill us all this time, and I wouldn’t be so inclined to deny it outright (I’d likely get what you were cooking at if you knew how to sauce it)… yet at the same time I don’t feel quite the same of that as I do for, say, more out-there semi-fantasies like anything from the Ultraman or, hell, the Kamen Rider series; they at least feel truer, more closer to the heart, y’know? They have their charms and wonders, yes – anything committed to the art of tokusatsu mustn’t be devoid of either-or to begin with, of course! – yet even in their most friendliest of visages there is more often than not an understanding of cruelty and malice beneath its villains and struggles, a grounded meaning of evil we can not only know in full but then be able to confront it and fight it to its utter end. George Lucas may’ve inserted World War II to Star Wars through the vast array of dime-a-pop war movies and periodical space epics of his childhood, and he may’ve taken the loose-from-reality adventurous spirits those stories held of themselves down to a tee, but at the end of the day it was still WWII, the war to end no wars... which wouldn’t be such a big deal if it had at any point sternly (and truly) acknowledged the graveness and weight that beheld that conflict through any of its creative impulses. Yet they tried… oh by golly did they try – they attempted it first with The Empire Strikes Back where they really put the opera in space opera by making our characters grow (then escalate) further into their worries and doubts and, in some cases, their inner darknesses with immeasurable success; and Lucas himself had single-handedly tried to make catharsis with the then-current tides of early 2000s America with the tremendous misfired oddity that keeps on giving of the Prequel Trilogy – yet even when they had it good there was always this knee-jerk reaction... the major step back... the retreat to Square Oneas if the series just so happened to possess by default a complete nervous system reactant to any sort of change or disturbance that dared touch or look its folds the wrong way, crushing any intruders good or bad to bits and sweeping its messes right under the bed as if to say, We’re always gonna have wars and we’re always gonna be happy about it, damn you! Damn you all to hell!

Now isn’t that just grand? We were supposed to have some fun and now we’re back to feeling as blue as Christmas (way to go brainiac, check out the smarts on you dipshit). Come on, let’s knock the bullshit and go play some tag, let’s chase each other out on the monkey bars over on the big toy, let’s play Starship Cowboys and ride the swings and see how high we can go see how far we can jump without scraping our knees and elbows and after that let’s watch Planet of the Apes yeeaaah Planet of the Apes now that’s a fun movie you know the one with the people wearing the goofy monkey suits and the fake rubber noses I mean that’s just crazy now look look at em go look at em swinging those sticks and riding their horses and shooting their guns and shit ain’t that funny I mean what were they on drugs when they made this I mean what a dumb fucking idea right haha.

“Smile.”

#planet of the apes#pota#franklin j. schaffner#pierre boulle#movies#consider the following#movietalk#more to come

0 notes

Text

#HARPERSMOVIECOLLECTION

2024 MOVIE LIST

www.tumblr.com/theharpermovieblog

🎃HALLOWEEN 2024🎃

I re-watched I Spit On Your Grave (1978)

Let's get dark....really dark.

After being sexually brutalized and left for dead, a young woman exacts her revenge on the men who committed the crimes against her.

Filmmaker Meir Zarchi doesn't have a huge resume. He's directed three films, written a book and produced a handful of movies. His biggest claim to fame is, in fact, this very film and his involvement with it's remake and the several sequels which followed the remake.

"I Spit On Your Grave" follows three of the most famous revenge films from the 1970's. Wes Craven's "Last House On The Left (1971) Sam Peckinpah's "Straw Dogs" (1971) and Bo Arne Vibenius' "Thriller: A Cruel Picture" (1973).

Revenge films are often gritty, disturbing, excessively violent, and not for everyone. They require the viewer to witness brutal acts upon innocent people. However, they also ask the viewer to face a dark side of themselves, and revel in the darkness of vicious and bloody retaliation.

Revenge films, whether they are trying to or not, give us a look into a very base and natural urge to get even. To see good not only triumph over evil, but to crush it. If done right, they make us question if we should take satisfaction in seeing blood for blood, or if we should strive to be better and forgiving. They are necessary art in my opinion, even if the genre itself is often too exploitative for some.

"I Spit On Your Grave" really turns your stomach in the exact moment the initial rape ends.

The movie starts out rather cheesy and typical, and doesn't feel like it's going to become as aggressive as it eventually does. When the rapists make their move it's franticly paced. You're too engaged to be disturbed, as the action pulls you in. Then, the rape happens, quick and cold. When it ends it's suddenly quiet again, and you feel the weight of the horrible act you've just witnessed. From there, it only gets worse.

This film shows you the worst things you can see, and one of the worst crimes there is. It is not a pleasant watch and it's not one I recommend for a fun Halloween. However, it is an effective Revenge film. Maybe not the smartest one or the most creative or best produced, but certainly effective.

0 notes

Text

Are people becoming afraid of American movies? When acquaintances ask me what they should see and I say THE LAST WALTZ or CONVOY or EYES OF LAURA MARS, I can see the recoil. It's the same look of distrust I encountered when I suggested CARRIE or THE FURY or JAWS or TAXI DRIVER or the two GODFATHER pictures before that. They immediately start talking about how they ''don't like" violence. But as they talk you can see that it's more than violence they fear. They indicate that they've been assaulted by too many schlocky films—some of them highly touted, like THE MISSOURI BREAKS. They're tired of movies that reduce people to nothingness, they say—movies that are all car crashes and killings and perversity. They don't see why they should subject themselves to experiences that will tie up their guts or give them nightmares. And if that means that they lose out on a TAXI DRIVER or a CARRIE, well, that's not important to them. The solid core of young moviegoers may experience a sense of danger as part of the attraction of movies; they may hope for new sensations and want to be swept up, overpowered. But these other, "more discriminating" moviegoers don't want that sense of danger. They want to remain in control of their feelings, so they've been going to the movies that allow them a distance—European films such as CAT AND MOUSE, novelties like DONA FLOR AND HER TWO HUSBANDS, prefab American films, such as HEAVEN CAN WAIT, or American films with an overlay of European refinement, like the hollowly objective PRETTY BABY, which was made acceptable by reviewers' assurances that the forbidden subject is handled with good taste, or the entombed INTERIORS.

If educated Americans are rocking on their heels—if they're so punchy that they feel the need to protect themselves—one can't exactly blame them for it. But one can try to scrape off the cultural patina that, with the aid of the press and TV, is forming over this timidity. Reviewers and commentators don't have to be crooked or duplicitous to praise dull, stumpy movies and disapprove of exciting ones. What's more natural than that they would share the fears of their readers and viewers, take it as a cultural duty to warn them off intense movies, and equate intense with dirty, cheap, adolescent? Discriminating moviegoers want the placidity of nice art—of movies tamed so that they are no more arousing than what used to be called polite theatre. So we've been getting a new cultural puritanism—people go to the innocuous hoping for the charming, or they settle for imported sobriety, and the press is full of snide references to Coppola's huge film in progress, and a new film by Peckinpah is greeted with derision, as if it went without saying that Bloody Sam couldn't do anything but blow up bodies in slow motion, and with the most squalid commercial intentions.

This is, of course, a rejection of the particular greatness of movies: their power to affect us on so many sensory levels that we become emotionally accessible, in spite of our thinking selves. Movies get around our cleverness and our wariness; that's what used to draw us to the picture show. Movies—and they don't even have to be first-rate, much less great—can invade our sensibilities in the way that Dickens did when we were children, and later, perhaps, George Eliot and Dostoevski, and later still, perhaps, Dickens again. They can go down even deeper—to the primitive levels on which we experience fairy tales. And if people resist this invasion by going only to movies that they've been assured have nothing upsetting in them, they're not showing higher, more refined taste; they're just acting out of fear, masked as taste. If you're afraid of movies that excite your senses, you're afraid of movies.

Pauline Kael

0 notes

Text

The Wild Bunch - dir. Sam Peckinpah (1969)

This film is a masterpiece, as you would expect from Peckinpah. An incredibly violent and bloody tale that's about getting old. Gloves are mainly limited to Robert Ryan so I've posted my favourites.

William Holden - at his best (and best looking) - stars. Not wearing gloves, sadly, but I'll get round to posting some of him soon.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

THE VISITOR (1979) “Atlanta, Georgia: where Polish God comes to fight obnoxious girl Sateen, step-daughter of basketball tycoon. You’ll throw your arms up and quickly move backwards trying to figure out how this Eye-Ti remix of OMEN + EXORCIST + ROSEMARY’S BABY gathered the faded legends of Old Hollywood. Groovy furniture, CQ sfx, and harrowing accidents but also glacial plot. As Uncle Marty said, “Would have made a great music video” -Sonny Gazelle

“Simultaneously thrilling and boring. No idea how John Huston and Bloody Sam Peckinpah were persuaded to act in this. CHINATOWN? Sure! THE VISITOR? ummmmm. They probs told Peckinpah he gets to abort the Antichrist. That might have been enough for him. Yo so why do Angel Children not get to have hair? Is Franco Nero Jesus? OR is he God? The Ol’ Ball and Chain Shelly Winters shows up to slap the shit out of a devil child. For once she’s not the butt of all the jokes. This shit is overstuffed and psychedelic but also slow. There’s like a half hour of basketball at the start with teams in generic-ass uniforms. I was offended by that. The costume designer couldn’t have been bothered. If I got that gig I would make my sports uni dreams come true. I mean this is awesome though I guess.” -Tommy Gazelle

0 notes

Photo

The Wild Bunch

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The Wild Bunch”

-A buck of misfit toys that are grumpy old men have their Vietnam war in Mexico, and end it all in a bloody shoot out

-you know, fucking awesome

-gotta love how after actor William Holden says the immortal line “If they move...kill em!” Then comes the title card “directed by Sam Peckinpah. Now that is a screen credit

-what I love most about him as a director is how in the middle of utter chaos he gives these victims of circumstances their blaze of humanity and dignity; the warm embrace of comfort that life otherwise denied them

-I think it’s worth noting that Peckinpah was also an alcoholic, so there is fair amount of lusty rambling, and utter spikes of lucidity

-it’s just endearing as Holden and Ernest Borgnine argue and support each other

-This is such a lived in world, each of the visual elements so assured and soaked in attention

-actor Warren Oates has great fun shooting the wine barrels and lapping up their liquid ambrosia

-what a train sequence. The way it’s held together by sheer willpower is mesmerizing

-westerns really do capture the mood of the times better than any other storytelling form (tied with horror); it’s as if the vast open lands allow emotions to paint in the negative space

+ the sheer heartache of the world in the late 1960s chalk outlined here (largely in red)

-quite spiffy to see an US filmmaker take back the dance lead from the (so great) Italian motion pictures

-I also think there is something captured in the scene of the ants attacking the scorpion; how the energy of crowds can destroy things individuals never can

-truthfully there isn’t a great deal of specific characterization in any one individual in this film (Pike being the main exception)

-it’s when they come in unison, like walking out of the whorehouse to their eventual death, that the film stirs up a swell of deep affection

-the beginning of this film is almost overwhelming; after numerous start and stop stills, the bank robbery has so much information backed in with quick cuts, like trying to get in 20 minutes of shoot outs in 8 minutes

-life can come at you fast, indeed

-I don’t consider this Peckinpah’s best film (call me crazy, but “Ballad of Cable Hogue” is my pick) but as a vivid statement of purpose, of screaming behavior, it obliterates the target

#the wild bunch#sam peckinpah#new beverly cinema#william holden#ernest borgnine#warren oates#ryan roberts#film#new bev

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Wild Bunch (1969); AFI #79

The next film up for review is one of the most famously violent films of the Western genre, The Wild Bunch (1969). The film was directed by Sam Peckinpah and has been described as "an orgy of violence" due to the first 10 minutes and the last 10 minutes of the film. The movie stars Western film legends William Holden, Ernest Borgnine, and Ben Johnson. The film was nominated for best screenplay and best original score, but it is one of the few on the AFI top 100 that didn't win any major awards. It is still iconic for 3 specific scenes of extreme violence and was rated X at the time for being so bloody. The film was cut down and reached a restricted (R) rating in the new MPAA system, but the film would never have been released prior and revealed a whole new level of realistic violence that became the standard. I want to go over the pacing, tone, and message of the film because it is really fascinating, but I will start with the normal synopsis and the standard spoiler warning. Here we go...

SPOILER WARNING!!! THIS IS A GREAT MOVIE THAT TAKES SOME VERY UNEXPECTED TURNS SO I WOULD SUGGEST GIVING IT A WATCH BEFORE READING THE SYNOPSIS!!! IT IS UP TO YOU, BUT YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!!!

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

The film starts out really strong as it goes straight into a heist and standoff before any characters are introduced. In 1913 Texas, Pike Bishop (William Holden), the leader of a gang of aging outlaws dressed as soldiers, is seeking retirement after one final score: the robbery of a railroad office containing a cache of silver. The gang is ambushed by Pike's former partner, Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan), who is leading a posse of bounty hunters hired and deputized by the railroad. A bloody shootout kills more than half of the gang, but Pike sees the ambush and uses a parade of Prohibitionists (ironically because the gang members are very heavy drinkers) to shield their getaway, and many citizens are killed in the crossfire.

Pike rides off with Dutch Engstrom (Ernest Borgnine), brothers Lyle (Warren Oates) and Tector Gorch (Ben Johnson), and Angel (Jaime Sanchez), the only survivors. They are dismayed when the loot from the robbery turns out to be a decoy: steel washers instead of silver coins. The men reunite with old-timer Freddie Sykes (Edmond O'Brien) and head for Mexico.

Pike's men cross the Rio Grande and take refuge that night in the village where Angel was born. The townsfolk are ruled by General Mapache, a corrupt, brutal officer in the Mexican Federal Army, who has been ravaging the area's villages to feed his troops while losing to the forces of the revolutionary Pancho Villa. Pike's gang makes contact with the general when Angel spots Teresa, his former lover, in Mapache's arms and shoots her dead, angering Mapache. Pike defuses the situation by offering to work for Mapache, but it seems apparent that the general wants Angel dead.

Mapache tasks the gang to steal a weapons shipment from a U.S. Army train so that Mapache can resupply his troops and appease Commander Mohr, his German military adviser, who wishes to obtain samples of America's armaments. The reward will be a cache of gold coins. Angel gives up his share of the gold to Pike in return for sending one crate of rifles and ammunition to a band of rebels opposed to Mapache. The holdup goes largely as planned until Thornton's posse turns up on the train the gang has robbed. The posse chases them to the Mexican border, only to be fooled again as the robbers blow up a trestle bridge spanning the Rio Grande, dumping the entire posse into the river. The pursuers temporarily regroup at a riverside camp and decide to continue the chase.

Pike and his men, knowing they risk being double-crossed by Mapache, devise a way of bringing him the stolen weapons without risk. They deliver information about the location of some of the guns in exchange for a share of the reward. This is working well, however, Mapache learns from Teresa's mother that Angel stole a crate of guns and ammo, and the general reveals this information as Angel and Engstrom deliver the last of the weapons. Surrounded by Mapache's army, Angel desperately tries to escape, only to be captured and tortured. Mapache lets Engstrom go, and Engstrom rejoins Pike's gang and tells them what happened.

Sykes is wounded by Thornton's posse while securing spare horses. The rest of Pike's gang returns to Agua Verde for shelter, where a drunken celebration over the weapons transfer has commenced. They see Angel being dragged on the ground by a rope tied behind the general's car, and after a brief frolic with prostitutes and a period of reflection, Pike and the gang try to forcibly persuade Mapache to release Angel, who by then is barely alive after the torture.

The general appears to comply; however, as the gang watches, he instead cuts Angel's throat. Pike and Engstrom angrily gun Mapache down in front of his men. For a moment, the Federales are so shocked that they fail to return fire, causing Engstrom to laugh in surprise. Pike calmly takes aim at Mohr and kills him, too. This results in a violent, bloody shootout involving over 100 on-screen deaths in less than five minutes in which Pike and his men are killed, along with most of Mapache's troops and the remaining German adviser. Peckinpah utilizes the idea of Chekov's gun because a machine gun was taken in the train robbery, and it is used heavily during the ending massacre.

Thornton finally catches up with his remaining posse to take the gang members' bullet-riddled bodies back to collect the reward. He elects to stay behind, knowing what awaits the posse. After a period, Sykes arrives with a band of the previously seen Mexican rebels, who have killed off what's left of the posse along the way. Sykes asks Thornton to come along and join the revolution, and Thornton smiles and rides off with them.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

There are other things that happened in the film that I did not mention above, but they are all so boring compared to the 3 major set pieces that they are not really worth mentioning in a synopsis. If I were to explain this movie, I would say there is a bank robbery, then a train robbery, and finally a showdown with a Mexican general. And that is one of the issues that a lot of people have with this film: it goes at either an absolute crawl or 100 miles per hour. This was something that is credited to being done on purpose by Peckinpah as he had become frustrated with the Vietnam war and the unrealistic portrayals of violence in Westerns and wanted to give the audience a true experience of being in a gun fight. Hours and hours sitting and waiting for something to happen then a flurry of overwhelming sights and sounds that one would be lucky to make it through. The life of an outlaw was supposed to be short and ironically both violent and boring. Peckinpah did an excellent job of showing this to the audience.

There was an interesting tone to the film, a sort of black or "gallows" humor. The characters break into fits of laughter at some of the most minor things like a person who is psychotic or somebody who is afraid and overwhelmed by nervous laughter. The constant laughing by people when they are nervous about dying or intending to kill someone is awkward, but again this is intentional. Killing and robbing is not funny, in fact living such a life is a flawed existence. The main character's, especially Pike, are constantly laughing at their own folly because otherwise they would have to face what they really were: murderers, thieves, and rapists. We, as an audience, might not be able to relate to these things (hopefully not), but we can all relate to making mistakes and laughing at ourselves.

Some critics and general audience members accused Peckinpah of glorifying violence under the guise of making art. He was also accused of being misogynistic. There aren't a lot of interviews with Peckinpah that I could find, but a lot of the cast spoke on their own experience with the director. Ernest Borgnine defended the amount of blood in the final shootout by asking if anyone had seen another person shot with a gun and there wasn't bleeding. Peckinpah famously said that dying was not fun and games despite many Westerns making it out to be such. The violence wasn't glorified as much as it was realistic and horrible. It is more of the way that major movies since the introduction of MPAA ratings will show violence. It is interesting to note that the movies that show the most death and truly glorify violence currently are the superhero films...and they make their studios a billion dollars in box office sales. Realistically depicting violence is not glorifying or promoting violence, so I wouldn't describe this film in that way at all.

A special note about the sound effects comes to mind as I finish up this review. I don't remember movies older than this one that didn't have stock gunshots that matched the weapon. There are films, such as Shane, that accentuated the sound and smoke of the guns in the film, but I think that Peckinpah was one of the first to cut in the sounds of the individual weapons and use live rounds to make realistic foley of a shoot-out that involved a wide variety of weapons. The deluge of sounds that accompany the constant bursting squibs as bodies fall to the ground is almost sickening, but that is the vision that Peckinpah wanted as opposed to "pop" and a man does a pirouette then falls gently to the ground. I have seen more realistic falls in professional soccer than some of these old Westerns.

I have seen this film a half dozen times at this point and the thing that has always fascinated me the most was the pause that occurs right after the gang shoots Mapache. Everybody was so stunned that they probably could have made their escape and maybe lived to fight another day, but these men were not Robin Hood or Swamp Fox. They did not fight for a good cause, and they knew that villains don't get to retire, so they accepted their fate and kept shooting. That one true moment when a person is honest with themselves and accepts who they are can be a life changing moment, but for this group it would lead directly to their death. The sad thing about being a villain is that deviation from the villainous path surely results in a swift death.

So, does this movie deserve to be on the AFI top 100? Absolutely. It changed the way that violence was portrayed in American cinema and tested the boundaries of a brand new MPAA ratings system. The acting wasn't outstanding, which is very different from many of the movies on the list, but the story, editing, and directing was exceptional and deserves acknowledgment. Would I recommend it? Yes, but know what this movie is before jumping in. This is not a cool Western where heroes defend what is right and villains get what is coming to them. This is a movie that pits evil and crazy against each other, and all are punished. I wouldn't recommend watching if you need role models and a happy ending. It is a fantastic movie, though, if you think you can handle it.

#western#sam peckinpah#william holden#ben holden#introvert#introverts#movies#psychology#violence#film review#long reads

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Case of Weapons and Mistaken Identity in a Bloody, Cheesy Romp.

There’s music in the air, but it’s not coming from a guitar. Rather, it’s the sound of gunfire and falling bodies. Such is the soundscape of El Mariachi (1992), Robert Rodriguez’s giddy, ultra-low-budget directorial debut. Directing, writing, photographing, and editing the entire film himself, Rodriguez crafts an incredibly stylish, if fairly tacky, tale of armed assassins, romance, and unfortunate circumstances.

Shot for a paltry $7,000, the film makes up for its unrealistic-looking props and jittery pacing with inspired cinematography and sumptuously bloody firefights, not to mention several chuckle-worthy moments of dark comedy. For such a meager career starter, El Mariachi went on to spawn a trilogy, expanding on its protagonist’ adventures in 1995’s Desperado and 2003’s Once Upon a Time in Mexico. That a film so small could have longevity just over a decade is a testament to Rodriguez’s clear passion for cinema and his knowledge of delivering a good time.

In a quaint Mexican town, the titular and nameless musician (Carlos Gallardo), clad in black and carrying his guitar in a case, is just looking for work from any of the local bars. Meanwhile, assassin Azul (Reinol Martinez) has escaped from prison and is quite literally gunning for his former boss Mauricio aka “Moco” (Peter Marquardt), who refuses to give him his cut of drug money. Mauricio sends his henchmen to hunt down Azul, who has made it to the same town. Also dressed darkly and lugging around a guitar case, Azul differs from the mariachi in that his case is full of weapons. Convening on the town, Mauricio’s goons mistake the mariachi for Azul forcing the hapless guitarist to go on the run and seek sanctuary from seductive bartender Domino (Consuelo Gómez), who harbors a dangerous secret.

Immediately from the opening sequence, one can tell Rodriguez loves 1970s grindhouse flicks, as the entirety of El Mariachi is styled like one. The film stock is gritty and grimy, while the handheld camerawork employs optical effects such as fisheye views and slow-motion to create wacky yet exciting action as the protagonist flees from his pursuers down the otherwise serene streets. Rodriguez was clearly going for an exploitation-esque aesthetic, and he definitely succeeded, putting his tiny budget to great use. What he could’ve worked on more was his editing, erratic and jumbled enough to make even the most levelheaded viewer dizzy, leading to several unclear moments and at least one continuity error.

However, what’s not disorienting are the shootout sequences, the film’s clear highlights. Taking a page from Sam Peckinpah’s seminal The Wild Bunch (1969), Rodriguez slows down the camera to capture every blood spurt, jerking body, and flashing muzzle with almost balletic beauty, again evoking grindhouse cinema in his glorious portrayal of visceral carnage. He’s a director who knows how to have fun, delivering old-school cinematic treats on a similar budget in a more contemporary time. If you crave more bullet-riddled mayhem, find out where El Mariachi goes from here with its aforementioned sequels. The song is just getting started.

--Conall Rubin-Thomas

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"WE WANTED TO SHOW VIOLENCE IN REAL TERMS. DYING IS NOT FUN AND GAMES."

PIC(S) INFO: Spotlight on assorted visceral film stills from one of the greatest films ever made -- the American epic revisionist Western, "The Wild Bunch" (1969), directed and co-written by Sam Peckinpah. Warner Bros-Seven Arts.

"We wanted to show violence in real terms. Dying is not fun and games. Movies make it look so detached. With "The Wild Bunch," people get involved whether they like it or not. They do not have the mild reactions to it."

— SAM PECKINPAH on depicting violence onscreen in his classic revisionist Western (American filmmaker/cinema legend)

Sources: https://twitter.com/bja_samuel/status/1325047548084629504, https://medium.com/applaudience/if-they-move-kill-em-2cb9ccb60579, various, etc...

#The Wild Bunch 1969#The Wild Bunch#Revisionist Western#Western#Westerns#1969#Cinematography#Sam Peckinpah#Samuel Peckinpah#Gun Violence#Sixties#The Wild Bunch 1969 Movie#Bloody Sam#Bloody Sam Peckinpah#Cinema#1960s#Western Movies#The Wild Bunch Movie#Film Director#Epic Revisionist Western#Film Stills#Filmmaker#Americana#Filmmaking#American Style#Movie Stills#Wild Bunch#David Samuel Peckinpah#Western Movies!#Violence in Movies

0 notes

Text

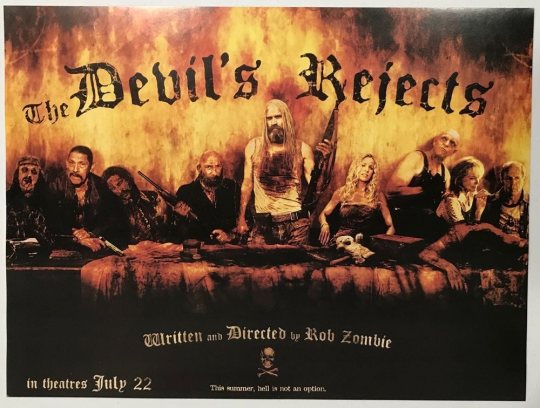

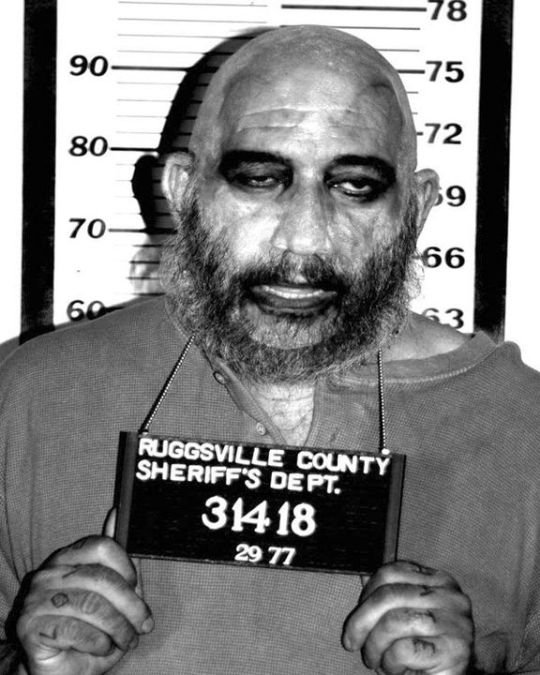

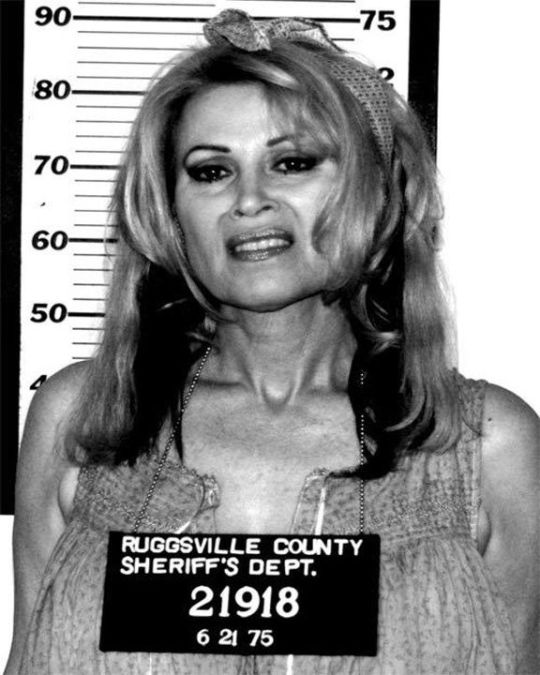

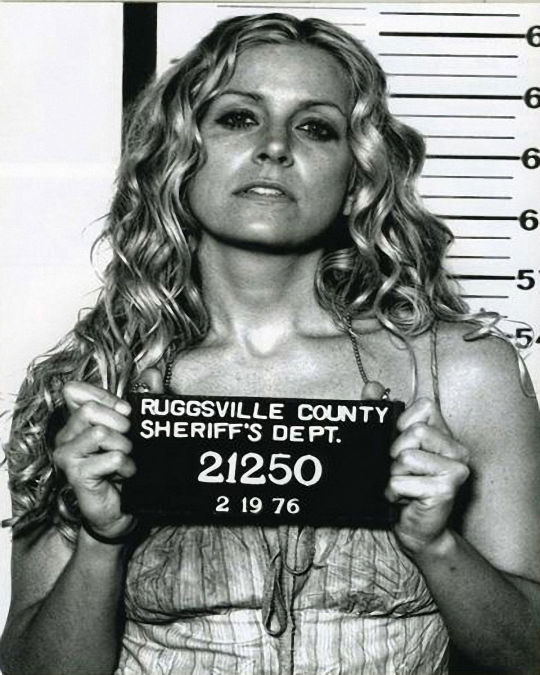

BLOGTOBER 10/2/2018: THE DEVIL’S REJECTS

The core ethos of Rob Zombie’s movies, if you can say that there is one, is individuality: a certain don’t-give-a-fuckness, a matter of being yourself at all costs, even if that means cutting holes in your pants for your ass to hang out of, not brushing your teeth, and murdering people who piss you off. In the spirit of that level of realness, I must confess that, even though I don’t have a lot of desire to defend it, a part of me really wants to like this messy, self-satisfied movie. Unfortunately, I can’t come clean about why, but that’s because I don’t really know.

It’s worth mentioning that THE DEVIL’S REJECTS is Rob Zombie’s sequel to his first feature, the incomprehensible HOUSE OF 1,000 CORPSES. This is worth mentioning precisely because it’s worth forgetting. The latter disaster, which to be fair Zombie was forced to make up on the spot in an impromptu pitch meeting, and which was plagued with production problems, amounts to a loose collection of pornographically violent cartoons, motivated by nothing other than the director’s love for his own ideas. It isn’t easy to take, but at least they are his own ideas. Whether or not I find it entertaining, I can find my way to appreciating a filmmaker just mashing up his personal fetishes, when so many movies are boringly predicated on one person’s condescending projection of what all of OUR fetishes are. Ultimately, Ho1KC’s lack of structure and...maybe I wanna say, point...makes all this fantasizing pretty irrelevant to anyone other than the fantasizer. Mercifully, THE DEVIL’S REJECTS finds Zombie squeezing a more carefully curated selection of his obsessions into a plot, with some character arcs and everything.

Ok, so it’s not like a masterpiece of mythology or anything. In fact, the movie’s fatal flaw, in spite of all this new coherence, is that it’s still too hard to tell what the point is. THE DEVIL’S REJECTS rescues the three strongest characters from its predecessor--Otis and Baby of the savage Firefly Clan, and Captain Spaulding, an ambiguous character from the first movie who is outed here as Baby’s father--and makes them over for this new effort. Their transition from being so broad that they might as well be puppets in a children's show, into salt of the earth psychos who you can practically smell, is a natural consequence of the new environment in which DEVIL’S REJECTS finds them. In fact, this sequel is part of a totally different genre than the Ho1KC, which clumsily smooshes together THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE and SPIDER BABY and THE ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW. The new movie, however blood-drenched, sets out for something more like Sam Peckinpah territory. There’s a brief moment I like at the beginning of the movie, when Spaulding--or Cutter, as he’s more casually called here--peels out to go rescue Baby and Otis from the bloody police raid on the Firefly compound. You see the dusty, dilapidated shack where Cutter lives, fenced off from an apocalyptic-looking wasteland, and then as he swings out into the road, the rich green expanse of an industrial farm. The new world of the Fireflies is utterly mundane, even depressed, a place whose banality is shattered only by the random acts of violence perpetrated by our defacto heroes.

It’s a big relief to not to have a bunch of shrill, spoiled teenagers squirming around, existing only as living opportunities for cartoon villains to demo their personalities. DEVIL’S REJECTS rejects this obligatory horror trope, in an important first step toward Rob Zombie finding his footing as a filmmaker. He not only positions the ostensible bad guys more clearly as heroes, which falls in line with his true feelings, but he populates his movies with grownups. This sounds simple, but in an entertainment landscape dominated by co-eds finding themselves, and 30-somethings acting to the best of their ability like co-eds finding themselves, it’s extremely inviting to see adults in all shapes and sizes with creased faces, aging flesh, and wiry muscles clinging to the bone against the ravages of gravity. Groovy young nubiles are seen only in battered photographs, usually beaten beyond recognition.

Therein lies the rub, though--in the movie’s ambiguous victimology. We know that the media-dubbed Devil’s Rejects are responsible for the torture, rape, murder, and necrophilic violation of a growing mass of apparent innocents in Ruggsville County. In the context of the movie, they do away with a handful of touring country signers, in order to force them to help unearth Otis’ buried arsenal, and to hide out in the group’s hotel room until Cutter catches up with them. Of course there’s plenty of sadistic thrills in the mix, but the question remains: What do the Devil’s Rejects usually do? What I mean is: The Sawyer clan only busts out the chainsaws for trespassers. Jason Voorhees kills violators of a set of stuffy social mores. Freddy Krueger kills primarily for revenge. In HOUSE OF 1,000 CORPSES, the Firefly family seems to kill mainly to punish smug, judgmental tourists. But it’s hard to figure out what the Rejects really want in the present film, and this is pretty hard to ignore when they’re construed as outlaw folk heroes. With all their ferocious family loyalty, swagger and charisma (and what Rob Zombie takes to be sparkling banter, but is mainly just the word “fuck” repeatedly so often that it achieves a zen-like obliteration of meaning), it’s clear that we’re supposed to like these guys. But, if they just kill people for no reason most of the time, and I don’t even see enough of it to get a sense of how everything shook out, then I have to start thinking that maybe they’re just a bunch of assholes. Certainly when they’re degrading and torturing their victims to death at great length in a seedy hotel, the droning HENRY: PORTRAIT OF A SERIAL KILLER-type music communicates to me that I’m supposed to think of this murder as a bad thing, a depressingly unnecessary tragedy perpetrated by...you know, a bunch of assholes. And you don’t go on to play “Freebird” over a majestic slow motion shootout for a bunch of assholes. Do you?

Obviously Rob Zombie is doing something right, because I’ve seen this movie several times before, and I have now written an amount of analysis of it that no normal person would ever want to read. But here I am, grappling with my feelings about the movie’s atmosphere, its look, its genre-bending story. Probably the safest thing for me to say now, in the continued spirit of the movie’s fierce individuality, is that I am actively looking forward to the next movie in the series, THREE FROM HELL. I’m ready to be disappointed, but I’m also ready for Zombie to continue to flesh out what it really means to be a Firefly. Fingers crossed that there turns out to be more of the latter than the former.

#blogtober#rob zombie#sherri moon zombie#sid haig#bill moseley#the devil's rejects#house of 1000 corpses#thriller#action#slasher#road movie#western#sheri moon zombie

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Snake Eyes, Storm Shadow, and the Legacy of Ninja Movies

https://ift.tt/eA8V8J

This article contains Snake Eyes: G.I. Joe Origins spoilers.

It’s been a long time since we’ve been to the movies and an even longer time since we’ve seen a ninja flick on the big screen. Snake Eyes: G.I. Joe Origins is a dazzling return to the underrated ninja genre – a breakout premiere in the shadow of the pandemic.

Ninja films rarely earn a theatrical showing anymore. They are pigeon-holed as B-grade movie fodder, and justifiably so. Back in the 1980, ninja films proliferated when second and third-run movie theaters ruled. Campy, low budget ninja pictures were popular fare there back then, right alongside slasher films and teen sex comedies. But with the advent of home entertainment, those cheap flea-ridden theater seats atop soda-sticky floors are long gone. Nowadays, most new ninja films go straight to streaming so to see one on the big screen is quite a treat for fans of the genre.

Above and beyond the G.I. Joe franchise, Snake Eyes rides on the cloak tails of a massive colorful genre (even if that color is mostly black splattered with sanguineous red). In Japan, ninja films are part of their venerated cinematic category known as Jidai-geki, or “period dramas.” Silent Japanese movies about ninjas can be found as early as the 1910s – silent like Snake Eyes himself.

Ninjas still proliferate Japanese cinema, especially in anime. Who can deny the impact of Naruto? And as anyone who has seen it knows – Batman Ninja is an uncommon treat of an anime mash-up. There are literally hundreds of Japanese ninja films – anime, classic historical, modern depictions, tokusatsu stories, even a whole sub-genre of erotic ninja films.

And ninja movies are still popular in Japan. In 2019, director Yoshitaka Yamaguchi delivered his highly regarded dual ninja films, Last Ninja: Red Shadow and Last Ninja: Blue Shadow. Like Snake Eyes, that was a creation story circling around a ninja rivalry.

Early Hollywood Ninja Movies

The immigration of ninjas to Hollywood goes back to none other than James Bond. In 1967, You Only Live Twice introduced Bond (Sean Connery in his final appearance as 007 in an Eon Production) to a clan of ninja accomplices. The film marked a significant departure from Ian Fleming’s original novel. You Only Live Twice was the conclusion of Fleming’s “Blofeld trilogy” where Bond finally gets revenge on his arch nemesis and murderer of his bride. Bond finally tracks down Blofeld in Japan, hiding in his “Garden of Death,” a restored castle surrounded by poisonous plants, and dispatches him in a brutal sword fight.

The movie script was written by children’s book author Roald Dahl, who pirated the plot of the second book of the Blofeld trilogy, Thunderball, in which SPECTRE steals a missile, but instead of atomic bombs, it’s a manned spacecraft. In retrospect, it felt right to have Her Majesty’s top assassin introduce Japan’s elite killers to Western audiences.

In 1975, celebrated action director Sam Peckinpah reintroduced Western audiences to ninjas in Killer Elite. James Caan and Robert Duvall play former covert operative partners, Mike Locken and George Hansen. Again akin to Snake Eyes, Locken and Hansen are split by a vengeance-filled rivalry. Hansen is in cahoots with a ninja clan, led by Negato Toku, played by renowned real-life Karate master Takayuki Kubota. Kubota invented a popular self-defense keychain that he dubbed Kubotan and instructed many celebrities, notably Martin Kove who plays Kreese in Cobra Kai. Sadly, Peckinpah succumbed to cocaine during production and Killer Elite is regarded by many critics as his worst film.

The 1980s: The Golden Age of Ninja Movies

The addition of Snake Eyes into the G.I. Joe universe came as a reboot of the toys that reflected the times. Originally G.I. Joe dolls were 12” military figures that were introduced in the 1960s. These were reality-based figures, each emulating the authentic uniforms and gear of U.S. armed forces. In 1982, the toy line was rebooted at 3 ¼” scale, the same size as the popular Star Wars figures introduced in the late 70s.

These new G.I. Joe came out with an accompanying marketing plan that included a simultaneous comic series from Marvel that revealed the rivalry between the “Real American Hero” G.I. Joe team and the villainous terrorist organization known as Cobra. The campaign was so successful that the first animated G.I. Joe TV show came out the following year.

And at the movies, the great ninja wave began with Chuck Norris’ 1980 flick The Octagon. Regarded as one of his stronger films, Norris played Scott James, a retired Karate champion, who has to face his rival half-brother, the ninja terrorist Seikura, played by another renowned Karate master, Tadashi Yamashita. Yamashita is credited as the man who taught Bruce Lee how to use his signature nunchaku. Norris opened the door for the ninja invasion of the ‘80s with The Octagon, as well as inspired the UFC’s trademarked octagonal ring, The Octagon, which has become a hallmark of the brand.

Following Norris’ lead, Sho Kosugi emerged as the leading ninja in grindhouse cinema. He starred in a series of ninja films beginning in 1981 with his preposterous yet entertaining “Ninja Trilogy,” Enter the Ninja, Revenge of the Ninja, and my personal favorite, Ninja III: The Domination (although most feel his 1985 film Pray for Death which falls outside the trilogy was his ninja masterpiece).

The other leading ninja franchise of the eighties was the American Ninja pentalogy. Michael Dudikoff played Private Joe Armstrong in a franchise which echoed the paramilitary ninja connection from G.I. Joe. In the first film, Armstrong faced the Black Star Ninja, seeing Tadashi Yamashita once again playing a ninja baddie.

Dudikoff was an exception to the rule that ninja film leads must have a martial arts background. However he was athletic and a quick study, and became a dedicated practitioner from his involvement with the franchise. Dudikoff starred in three of American Ninja films. He skipped American Ninja 3: Blood Hunt because he didn’t want to get typecast as a martial arts actor and was anti-apartheid (it was filmed in South Africa). He returned for American Ninja 4: The Annihilation but didn’t appear in American Ninja V. Both Kosugi’s films and American Ninja franchise were produced by that goliath grindhouse of the eighties, Cannon Films. They made ample bank slinging ninja films back then.

The ‘80s ninja craze helped inspire G.I. Joe’s Snake Eyes, and he quickly rose to become a favorite character. The pivotal G.I. Joe comic issue #21, “Silent Interlude,” was published in 1984 (coincidentally the same year the first Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles comic was released). This was one of the first modern comics to be told entirely without word bubbles. It helped set the tone of silence for Snake Eyes’ character. That issue also marked the first appearance of Storm Shadow.

As with all comic-to-cinema characters, Snake Eyes has several incarnations, depending upon which story you follow. In the comic canon, Snake Eyes suffers a horrible helicopter crash while saving Scarlett’s life. His face is burned and he loses his voice, something very different than what we see on screen in Snake Eyes: G.I. Joe Origins.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong was getting into the action by infusing Kung Fu movies with ninjas. Leading the charge was the ultimate martial arts rivalry between China and Japan, 1978’s Challenge of the Ninja (a.k.a. Heroes of the East) in 1978, Veteran Kung Fu star Gordon Liu played Ho Tao, who must match his skills against his Japanese bride’s family. Got ninjas? According to Liu, the solution is scattering your yard with peanut shells!

In a savvy move for those times, Challenge of the Ninja depicts the Japanese respectfully instead of as caricatured villains, with the exception of the ninja who Ho declares to be dishonorable. Challenge of the Ninja is widely considered as one of the all-time best Kung Fu films and in its wake, dozens more ninja films came out in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

In 1982, the legendary Kung Fu grindhouse Shaw Brothers studios delivered the outrageously imaginative Five Elements Ninjas, directed by the legendary Chang Cheh who dominated the Kung Fu film genre with his gloriously bloody epics.

The last major ninja film that was released theatrically in the United States was Ninja Assassin in 2009 (coincidentally the same year that G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra came out). It was James McTeigue’s second directorial effort following V for Vendetta, and starred K-pop singer and dancer, Rain. For ninja fans, it had a fitting homage by casting Sho Kosugi as the villain. Ninja Assassin was Kosugi’s final theatrical film role to date. The film hoped to continue as a new ninja franchise, and although it was profitable, it failed to attract enough of a following to warrant a sequel.

The Rise of Snake Eyes

It’s a bold move for Snake Eyes: G.I. Joe Origins to premiere exclusively in theaters. Not even Black Widow was so daring with the Delta variant looming. As theaters reopen, it seems telling that several of the first theatrical films coming out are about stealthy martial arts masters.

You could argue that Natasha Romanoff is an MCU ninja (Elektra is the real Marvel ninja but Jennifer Garner’s film doesn’t count in the MCU “sacred timeline”). You could also argue that Mortal Kombat is a ninja movie. Both have black clad assassins wielding martial arts weapons.

However Snake Eyes is a pure ninja film, unabashed and unapologetic in its style and gratuitousness. Regardless of its G.I. Joe origins, the Joes are peripheral. Snake Eyes evades that with a glorious reboot, shifting away from the canon established in the previous two live-action G.I. Joe films and forging its own path.

Snake Eyes is Hasbro’s Batman Begins. It’s a completely novel creation story for the characters that defies what the film franchise has already established. The origin story of Snake Eyes and Storm Shadow was already told in the first film, G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra. While not the central tale, it was a significant story arc that forecasted how the ninjas would eventually eclipse the Joe’s paramilitary characters in popularity.

In Paramount’s previous G.I. Joe films, Wushu champion Ray Park played the silent Snake Eyes, and taekwondo practitioner Lee Byung-hun was Storm Shadow. Byung-hun is constantly twirling a shuriken like a fidget-spinner, predating the 2017 fad by eight years. Park never speaks or shows his face, in character with the Snake Eyes of the comics. Their teacher the Hard Master is played by another real life martial arts master Gerald Okamura.

The sequel, G.I. Joe: Retaliation added another ninja, Kim Arashikage, a.k.a. Jinx, played by Elodie Yung, a black belt in Karate. Yung went on to play Elektra in Netflix’s Daredevil. The standout act was a thrilling ninja battle while rappelling down a Himalayan cliffside. That show-stopping scene put the sequel above the original film, especially if you saw it in 3D IMAX. In a sneaky way, the ninja story arc creeps up on the G.I. Joe films from behind, and now it’s all about those ninjas.

Bringing Ninjas Back

Compared to the CGI bombast of the earlier two films, Snake Eyes has cool cinematic style, bathed in Tokyo neon and split with flashing katana blades. And when it comes to action, it cuts quickly to the chase. Like any good ninja flick, there’s just enough plot to get to the next sword fight, no more, no less. And in contrast to previous outings, Snake Eyes tells a completely different origin story for the mysterious Snake Eyes.

In this reboot, Snake Eyes (Henry Golding) and Thomas Arashikage (Andrew Koji) meet as adults, not as children. The Hard Master is played by Iko Uwais, a genuine master of the Indonesian martial art of Silat. A practitioner of Taekwondo and Shaolin Kung Fu, Koji best known as Ah Sahm, the lead role in the Bruce Lee inspired Cinemax series Warrior.

Like Dudikoff decades ago, Golding had no martial arts background prior to accepting the role. Once he landed it, the Crazy Rich Asians star spent four hours a day training with the stunt team in preparation.

With the exception of Golding, the casting of genuine martial arts practitioners underscores a critical element in ninja films. Ninja films are about martial arts fights. No matter how good the story and acting might be, a ninja film fails if it doesn’t bring great action. Consequently for a ninja film to work, it needs a cast with a genuine martial arts background.

Golding makes up for his lack of skills with his smoldering screen presence, but much credit must be given to the film’s fight coordinator, Kenji Tanigaki. Tanigaki is one of Asia’s top choreographers who has been in the business since the mid ‘90s. Just prior to Snake Eyes, he oversaw the action on Donnie Yen’s last two films, Enter the Fat Dragon and Big Brother, and completed two more installments of the five-part samurai manga-turned-movie series Rurouni Kenshin.

Snake Eyes is poised to spin off into its own franchise. The end credits scene with Storm Shadow declaring his new identity to the Baroness (Úrsula Corberó) was hardly a surprise to anyone, but it teased the possibility of a sequel. Back in May 2020, Paramount and Hasbro were in negotiations with Joe Shrapnel and Anna Waterhouse to write the script, but then the world plunged into the pandemic and no more developments have been announced at this writing. Will the sequel be Snake Eyes’ The Dark Knight? For ninja fans all over the world, we can only hope.

cnx.cmd.push(function() { cnx({ playerId: "106e33c0-3911-473c-b599-b1426db57530", }).render("0270c398a82f44f49c23c16122516796"); });

Snake Eyes: G.I. Joe Origins is now playing in theaters.

The post Snake Eyes, Storm Shadow, and the Legacy of Ninja Movies appeared first on Den of Geek.

from Den of Geek https://ift.tt/3eR6QFv

0 notes

Photo

It’s a traumatic poem of violence, with imagery as ambivalent as Goya’s. By a supreme burst of filmmaking energy, Sam Peckinpah is able to convert chaotic romanticism into exaltation; the film is perched right on the edge of incoherence, yet it’s comparable in scale and sheer poetic force to Kurosawa’s “The Seven Samurai.” The movie, set in 1913, is about a band of killers who flee Texas for Mexico, and Peckinpah has very intricate, contradictory feelings about them. He got so wound up in the aesthetics of violence that what had begun as a realistic treatment—a deglamorization of warfare that would show how horribly gruesome killing really is—became instead an almost abstract fantasy about violence. The bloody deaths are voluptuous, frightening, beautiful. Pouring new wine into the bottle of the Western, Peckinpah explodes the bottle; his story is too simple for this imagist epic. And it’s no accident that you feel a sense of loss for each killer of the Bunch: Peckinpah has made them seem heroically, mythically alive on the screen. With William Holden, Ernest Borgnine, Robert Ryan, Ben Johnson, Edmond O’Brien, Warren Oates, Bo Hopkins, L. Q. Jones, Strother Martin, Jaime Sanchez, Emilio Fernandez, Albert Dekker, and Dub Taylor. Released in 1969.

—

Pauline Kael

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

animated Straw Dogs (1971) directed by Sam Peckinpah David Sumner (Dustin Hoffman) lost all pity

Upon moving to Britain to get away from American violence, astrophysicist David Sumner and his wife Amy are bullied and taken advantage of by the locals hired to do construction. When David finally takes a stand it escalates quickly into a bloody battle as the locals assault his house. (from IMDb)

10 notes

·

View notes

Quote

On the 29th of December 1984, the day after Sam Peckinpah died at the age of 59, a small obituary appeared in the New York Times. It claimed that Peckinpah, “best known for his westerns and graphic use of violence… attained notoriety for such films as The Wild Bunch, a brutal picture that was by several thousand red gallons the most graphically violent Western ever made and one of the most violent movies of all time.” With the release of The Wild Bunch, Peckinpah became known as “Bloody Sam.” The release of Straw Dogs in 1971 cemented the cult of notoriety, making Peckinpah a marketable, yet controversial director. Much sought after, he gave contentious interviews to a variety of newspapers and magazines, including Game, Playboy, Films and Filmmaking, and Take One, while also writing letters to newspaper editors justifying his work and slamming his detractors. Under the microscope of feminist film theory, his sometimes aberrant treatment of the representation of women and his “excessive” use of violence was noted and condemned. With Peckinpah making it onto the hit list of Joan Mellen’s Big Bad Wolves, further investigation was deemed unnecessary.

Gabrielle Murray, This Wounded Cinema, This Wounded Life

#gabrielle murray#this wounded cinema this wounded life: violence and utopia in the films of sam peckinpah#sam peckinpah#joan mellen

0 notes