#Blanche Yurka

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Cry of the Werewolf

A few minutes into Henry Levin’s debut feature, CRY OF THE WEREWOLF (1944, Tubi, YouTube), John Abbott, the tour guide at the Marie La Tour Museum of the Supernatural, intones in his mellifluous voice, “We will now proceed to the voodoo room,” and I almost fell out of my chair laughing. Maybe it was lack of sleep or a hitherto undiscovered side effect of Ozempic. But then, most of the film seemed utterly ludicrous to me. Columbia Pictures’ attempt to cash in on Universal’s classic horror cycle is a rather limp noodle, proving that when they’re not directed by Joseph Lewis or William Castle, the studio’s B output isn’t anything to cheer about.

Dr. Morris (Fritz Leiber), head of the museum, has discovered the resting place of New Orleans werewolf Marie La Tour. This does not please her daughter (Nina Foch), a Romany princess who’s inherited her mother’s habit of turning into a wolf to dispatch her enemies. She takes out the old man, and then has to deal with his son (Stephen Crane) and the police, headed by Barton MacLane. The script never really clarifies why she would kill someone to keep the grave a secret beyond a vague desire for privacy. There’s a telling line at an inquest when Crane refers to her tribe’s superstitions, and she says, “What you call superstition we call religion,” but this was not the era to examine that idea as a reflection of Western colonialism. Instead, we get a lot of skulking around in the dark, a few shots of a wolf’s shadow and feet and a sequence lifted from CAT PEOPLE (1942) by people who didn’t understand how it worked.

There are a few decent camera angles, and at least it all moves fast. MacLane does a good job, and you get nice character turns by Blanche Yurka and Ivan Triesault. Foch tries hard and gets off some good line readings, but she can’t exude menace the way a Gale Sondergaard could. Of course, it doesn’t help that her character is all over the place. At one point she’s coldly threatening a fellow Romany who’s made himself a suspect. At another she’s crying because she had to kill him. Leading lady Osa Massen works well as the museum’s receptionist and Crane’s love interest. When Foch puts her in a trance, it’s different from her non-trance behavior. A lot of horror film actresses have problems with that sort of thing. As for Crane, or Mr. Lana Turner as he was known then, he’s rather lumpen. But then, he wouldn’t inflict his acting on an unsuspecting public for long before he gave it up to become a successful and influential restauranteur.

#horror films#werewolf films#b movies#nina foch#henry levin#fritz leiber#osa massen#blanche yurka#ivan triesault#barton maclaine#bad movies

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#the flame#john h. auer#1947#blanche yurka#constance dowling#vera ralston#robert paige#john caroll#broderick crawford#inland empire

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

6 giugno … ricordiamo …

6 giugno … ricordiamo … #semprevivineiricordi #nomidaricordare #personaggiimportanti #perfettamentechic

2023: Pat Cooper, nato Pasquale Caputo, attore statunitense. Cooper nacque a Brooklyn, da Michael Caputo (Michele Caputo), un muratore italiano originario di Mola di Bari, e da Louise Gargiulo, nata anch’ella a Brooklyn da immigrati italiani. Recitò in circa 20 film a partire dall’inizio degli anni sessanta e divenne noto per il film Terapia e pallottole e il suo sequel Un boss sotto stress. Si…

View On WordPress

#6 giugno#6 giugno morti#Anne Bancroft#Anne Marno#Blanch Jurka#Blanche Yurka#Dana Elcar#Domenico Maggio#Elvio Calderoni#Enrichetta Thea Prandi#Esther Jane Williams#Esther Williams#Eugene Clair Persson#Florence Roberts#Gene Persson#Gualtiero De Angelis#Jack Haley#Larry Blyden#Larry Riley#Lloyd Hughes#Magda Gabor#Magdolna Gabor#Massimo Osti#Mimì Maggio#Mort Hall#Mort Mills#Pasquale Caputo#Pat Cooper#Pierre Brice#Pierre-Louis Baron Le Bris

0 notes

Text

I have officially spent too much time contemplating Struwwelpeter today

#there was an incorrectly dated reference to it in some of our curatorial material#and I knew it was wrong but I had no idea what source to go at first#but I went through the day by day compilation and found it#so if anybody is wondering:#mark Twain worked on his English translation of Struwwelpeter from October 24th to 28th in Berlin in 1891#not in 1878#which is what our Christmas material states#I’m pretty sure they went to Berlin that year as well#which is probably why it was wrong#they spent a lot of time in Europe so it’s easy to reference the wrong trip to Germany#ngl I do get a rush out of correcting inaccuracies so I can’t wait to send this find to our curator#and see if she wants to update other things as well#the Christmas material hasn’t been updated since 2016#it’s like the time I got IBDB to update Blanche yurka’s bio and denote the discrepancy of her birthplace#museum musings

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barbara Stanwyck, Walter Huston, and Judith Anderson in The Furies (Anthony Mann, 1950)

Cast: Barbara Stanwyck, Walter Huston, Wendell Corey, Judith Anderson, Gilbert Roland, Thomas Gomez, Beulah Bondi, Albert Dekker, John Bromfield, Wallace Ford, Blanche Yurka. Screenplay: Charles Schnee, based on a book by Niven Busch. Cinematography: Victor Milner. Art direction: Henry Bumstead, Hans Dreier. Film editing: Archie Marshek. Music: Franz Waxman.

The Furies takes place in a West that never was: Would any real cattleman name his ranch "The Furies"? But that's because the film aims at the mythic, and darn near succeeds. The Furies of myth were goddesses of vengeance, also known as the Eumenides, which means "the gracious ones" -- they were so terrible that humans tried to placate them by calling them by a nice name. In the film, all of the women are to some degree vengeful: Barbara Stanwyck's Vance Jeffords chafes against the notion that because she's a woman, she can't run a ranch; Judith Anderson's Flo Burnett tries to get her hooks into Vance's father and bypass Vance's claim to his estate; Beulah Bondi's Mrs. Anaheim is the real power behind her banker husband; and the most vengeful of them all, Blanche Yurka's Mother Herrera, seeks justice for the hanging of her son. For a Western, it's also awfully talky, with some lines that sound like film noir: "I don't think I like love," says Vance. "It puts a bit in my mouth." Others are obvious attempts to sidestep cliché: Vance's father, T.C. (Walter Huston), tells her she has a "dowry if you pick a man I can favor, one I can sit down at the table with and not dislodge my chow." I suspect that a lot of the dialogue, as well as a lot of the slightly overcomplicated plot, comes from its source, a novel by Niven Busch, adapted by Charles Schnee: Busch knew his way around tough dialogue, having written the screenplay for one of film noir's classics, The Postman Always Rings Twice (Tay Garnett, 1946). Anthony Mann keeps the action from overwhelming the talk and the mythologizing, greatly helped by Stanwyck and Huston (in his final film) as the sparring but inextricably bonded Jeffordses. The movie could have used a stronger love interest than Wendell Corey as Rip Darrow, the man who wants to get the better of T.C., and woos Vance as part of the plot. Corey and Stanwyck don't strike sparks; she's more in tune with Gilbert Roland as Juan Herrera, the squatter on The Furies who has been her friend since childhood -- a subplot that's in some ways more interesting than the financial struggles to get hold of the ranch. Initially a box office failure, the film has grown in stature over the years as a showcase for some of the best work of Stanwyck, Huston, and Mann.

8 notes

·

View notes

Video

Jennifer Jones | The Song Of Bernadette {1943) | Full Length Movie Classic

The Song of Bernadette was a 1943 US biographical drama movie based on the 1941 novel of the same name by Franz Werfel. The film stars Jennifer Jones as Bernadette, the film is the story of Bernadette Soubirous, who experienced 18 visions of the Virgin Mary between February and July of 1858. She was canonized in 1933. The Cast: Jennifer Jones as Bernadette Soubirous Charles Bickford as Abbé Dominique Peyramale William Eythe as Antoine Nicoleau Gladys Cooper as Marie Therese Vauzou, Bernadette's schoolteacher and later the Mistress of Novices Vincent Price as Vital Dutour, Imperial Prosecutor Lee J. Cobb as Dr. Dozous Anne Revere as Louise Casterot Soubirous, Bernadette's mother Roman Bohnen as François Soubirous, Bernadette's father Mary Anderson as Jeanne Abadie, Bernadette's friend Patricia Morison as Empress Eugenie Jerome Cowan as Emperor Napoleon III Aubrey Mather as Mayor Lacade Charles Dingle as Jacomet, chief of police Edith Barrett as Croisine Bouhouhorts Sig Ruman as Louis Bouriette Blanche Yurka as Bernarde Casterot, Bernadette's aunt Ermadean Walters as Marie Soubirous, Bernadette's sister Marcel Dalio as Callet Pedro de Cordoba as Dr. LeCramps Eula Morgan as Madame Nicoleau Let Mr. P notify you when new videos are uploaded, join the channel. https://www.youtube.com/@nrpsmovieclassics

0 notes

Photo

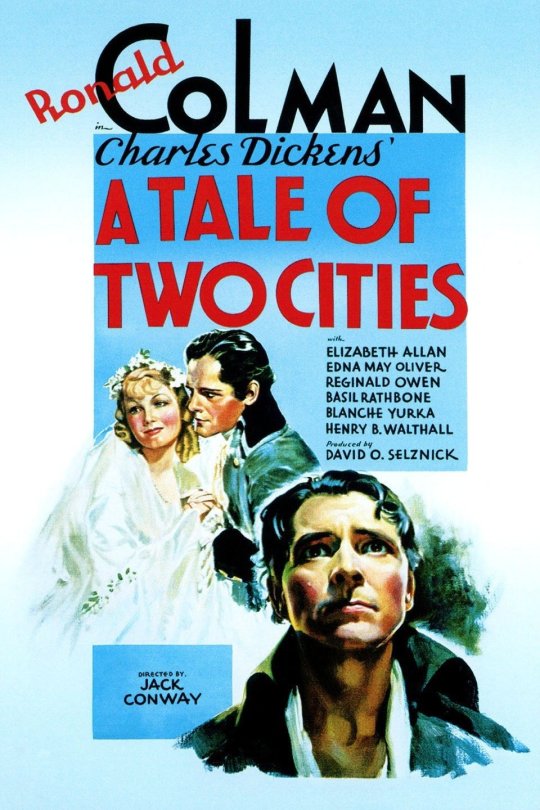

#a tale of two cities#ronald colman#elizabeth allan#edna may oliver#reginald owen#basil rathbone#blanche yurka#henry b. walthall#jack conway#1935

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

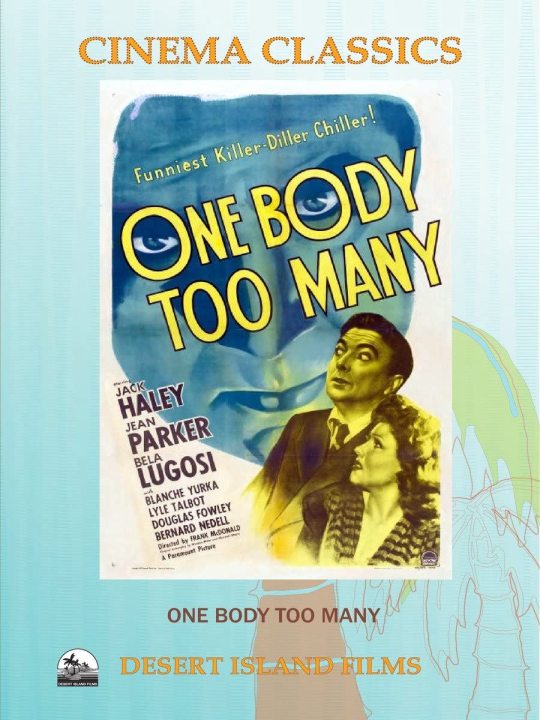

One Body Too Many

One Body Too Many

One Body Too Many (1944) starring Jack Haley, Jean Parker, Bela Lugosi One Body Too Many – insurance salesman Jack Haley stumbles onto an eccentric millionaire’s will, and the murder mystery among his relatives. (more…)

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cry of the Werewolf (1944) Henry Levin

August 17th 2020

#cry of the werewolf#1944#henry levin#nina foch#osa massen#stephen crane#barton maclane#blanche yurka#robert b. williams#ivan triesault#john abbott#milton parsons#fritz leiber

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#13 rue madeleine#henry hathaway#james cagney#annabella#richard conte#frank latimore#e.g. marshall#karl malden#sam jaffe#blanche yurka

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Furies

If all Westerns looked like John Ford’s or Anthony Mann’s, I think I’d be a much bigger fan of the genre. Of course, it’s almost unfair to call Mann’s THE FURIES (1950, Criterion Channel, YouTube) a Western. It’s more of an anti-Western. It features the same conflict as in most of the genre — the frontier vs. civilization — but in this case civilization is represented not by home, family and the feminine but rather by business interests, particularly banks. And as shot by Victor Milner, the wide-open spaces are more oppressive than liberating. These characters don’t need railroads and cities and farms to fence them in. They’re already confined by their own twisted passions. Walter Huston is the tyrannical, mercurial owner of a ranch called The Furies. He’s Lear on horseback. He plans to leave everything to his tough, adoring daughter (Barbara Stanwyck) as long as he can control her life, including whomever she might marry. Then he comes home from a business trip with a wealthy widow (Judith Anderson) out to take Stanwyck’s place, and the fur and the scissors fly. Charles Schnee adapted the script from a Niven Busch novel, and at the start it has the meandering quality of a lot of fiction. You can’t quite tell where the story’s going, but the characters and atmosphere are so rich it doesn’t matter. And when you get to see Huston (in his last film) and Stanwyck interact, who needs a plot. There’s a terrific score by Franz Waxman and wonderful supporting work from Anderson, Gilbert Roland, Thomas Gomez, Blanche Yurka and Beulah Bondi, who’s barely on screen five minutes yet manages to capture her character simply in the way she transfers her fan from one hand to the other. Censorship imposed a certain racism on the film. Where Stanwyck and Roland had an affair in the novel and even married, that was turned into a friendship and Roland’s unrequited love, because his character, a Mexican, couldn’t be intimate with a white woman. And then there’s Wendell Corey. He’s better than in a lot of his leading roles, but he hardly seems magnetic enough to capture Stanwyck’s passions. And the character, as written for the screen, doesn’t make a lot of sense. He uses Stanwyck at first and then suddenly falls in love with her. Nor does it help that he has a misguidedly chauvinistic proposal scene: “And don’t ask me to be your husband. If we marry, remember one thing. You’ll be my wife. Whenever you’re wrong, I’ll tell you so. If I’m ever wrong, you just keep your little mouth shut.” Would anybody ever believe he could exercise that kind of control over a Barbara Stanwyck? Or a Barbara Hale? Or even a Barbara Pepper?

#anthony mann#barbara stanwyck#walter huston#judith anderson#gilbert roland#blanche yurka#beulah bondi#thomas gomez#franz waxman#western noir#western#film noir#wendell corey

1 note

·

View note

Text

6 giugno … ricordiamo …

6 giugno … ricordiamo … #semprevivineiricordi #nomidaricordare #personaggiimportanti #perfettamentechic

2015: Pierre Brice, nato Pierre-Louis Baron Le Bris, attore francese famoso in Germania. (n. 1929) 2013: Esther Williams, Esther Jane Williams, è stata una nuotatrice e attrice statunitense. (n. 1921) 2008: Gene Persson, Eugene Clair Persson, è stato un attore, produttore teatrale e cinematografico statunitense. Ha sposato Shirley Knight e dopo il divorzio sposò Ruby Persson. (n. 1934) 2005:…

View On WordPress

#6 giugno#6 giugno morti#Anne Bancroft#Anne Marno#Blanch Jurka#Blanche Yurka#Dana Elcar#Domenico Maggio#Elvio Calderoni#Enrichetta Thea Prandi#Esther Jane Williams#Esther Williams#Eugene Clair Persson#Gene Persson#Gualtiero De Angelis#Jack Haley#Larry Blyden#Larry Riley#Lloyd Hughes#Magda Gabor#Magdolna Gabor#Massimo Osti#Mimì Maggio#Mort Hall#Mort Mills#Pierre Brice#Pierre-Louis Baron Le Bris#Ricordiamo#Ruggero De Daninos#Thea Prandi

1 note

·

View note

Photo

2017:189 — Cry of the Werewolf

(1944 - Henry Levin) ***

#film#1944#Cry of the Werewolf#Henry Levin#Nina Foch#Stephen Crane#Osa Massen#Blanche Yurka#Barton MacLane#three stars#shocktober

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Betty Field and Zachary Scott in The Southerner (Jean Renoir, 1945)

Cast: Zachary Scott, Betty Field, J. Carrol Naish, Beulah Bondi, Percy Kilbride, Charles Kemper, Blanche Yurka, Norman Lloyd. Screenplay: Hugo Butler, Jean Renoir, based on a novel by George Sessions Perry. Cinematography: Lucien N. Andriot. Production design: Eugène Lourié. Film editing: Gregg G. Tallas. Music: Werner Janssen.

The Southerner is perhaps the best of the films Renoir made during his wartime exile in the United States, which is not to say that it ranks with his French masterpieces that include Grand Illusion (1937), La Bête Humaine (1938), or Rules of the Game (1939). It does, however, stand up well against the better American films of 1945, such as Mildred Pierce (Michael Curtiz), Spellbound (Alfred Hitchcock), or Leave Her to Heaven (John M. Stahl). It also earned him his only Oscar nomination as director: He lost to Billy Wilder for The Lost Weekend, but he was presented an honorary Oscar in 1975. The film was also nominated for sound (Jack Whitney) and music score (Werner Janssen). The Southerner feels less authentic than it might: Renoir was unable to overcome the Hollywood desire for gloss, so Betty Field looks awfully healthy and well-coiffed for the wife of a hard-scrabble cotton farmer whose family lives in a shack with no running water and whose youngest child almost dies of "spring sickness" -- a form of pellagra caused by malnutrition. Zachary Scott is a little more credible as her determined husband, Sam Tucker, a cotton picker who decides to start farming on his own. The role is a sharp contrast to his performance the same year in Mildred Pierce, in which he's a slick con man -- the kind of role he found himself playing more often. The cast also includes Beulah Bondi as Sam Tucker's grandmother, J. Carrol Naish as the Tuckers' stingy neighbor, and Norman Lloyd as the neighbor's nephew and man-of-all-work, who tries to drive the Tuckers off their land. Renoir is credited with the screenplay along with Hugo Butler, who did the adaptation of a novel by George Sessions Perry, but it was also worked on by an uncredited William Faulkner and Nunnally Johnson.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Southerner (1945)

Directed by Frenchman Jean Renoir, The Southerner’s drama takes place far from the Western front as seen in Renoir’s Grand Illusion (1936, France), even further the upper-class shenanigans found in The Rules of the Game (1939, France). The setting is rural Texas, a part of the United States with no equivalent in France. With the people in The Southerner – adapted from George Sessions Perry’s 1941 novel Hold Autumn in Your Hand – occupying a space sprawling and isolated, appealed to Renoir not for the story, but the raw emotions involved and that the characters:

...attain a level of spirituality of which they themselves are unaware... all the characters [are] heroic, in which every element would brilliantly play its part, in which things and men, animals and Nature, all would come together in an immense act of homage to the divinity.

Hollywood, in its depictions of twentieth- and twenty-first century rural America, has largely dismissed that divinity of which Renoir speaks of. Leave it to an outsider to recognize that and show it in a movie. Renoir, who had fled his homeland due to the advances of Nazi Germany, found himself frustrated with Hollywood’s producer-oriented Studio System. He had been allowed unfettered freedom in France’s director-first systems, and was most comfortable in such environments. Released by United Artists (UA), The Southerner would essentially – despite the fact UA was considered a major studio – be an independent production. And before the end of his career, Renoir would note that The Southerner (his third American film) would be the only American film of his that he would be truly satisfied with.

Sam Tucker (Zachary Scott), his wife Nona (Betty Field), and his Uncle Pete (Paul E. Burns) are migrant sharecropper farmers picking cotton in Texas. The migrants are white, black, and Latino in a brief visual, sociological representation – perhaps the questions raised there can be the basis for a future movie. One day, Uncle Pete collapses from the intense heat and, knowing his heart too weak to continue, urges Sam and Nona to, “Work for yourself, grow your own crops.” Sam is inspired to do just that – securing a plot of land, taking his wife, the children Daisy (Jean Vanderwilt) and Jot (Jay Gilpin), and Granny (Beulah Bondi) to their new home to become an independent tenant farmer. It is not easy. Uncooperative neighbors (J. Carrol Naish and Norman Lloyd), being at nature’s mercy, the “Spring Sickness” (Pellagra), starvation, and other obstacles emerge in the first several months of Sam and Nona’s endeavors.

The screenplay by Hugo Butler and Renoir – with William Faulkner (yes, that Faulkner) and Nunnally Johnson uncredited – is sparse, content to allow several scenes to pass without much dialogue. What the screenwriters are most interested in is developing the requisite pathos for the audience members – regardless of their familiarity with the harshness of a farmer’s life – to empathize with the tribulations depicted onscreen. One disaster is addressed, with some respite and time for observational humor. But oftentimes that respite is fleeting, and the drama of another potential disaster requires a response. So often the Tuckers’ behavior is one of reaction to the nature surrounding them. This serves to emphasize how their survival can be dependent on the assistance of others. When a neighbor refuses to share, provide advice, or outright sabotages their efforts, the consequences can be the difference between life and death. The Tuckers’ symbiotic connection to the land – which can be extended to all farmer growing their own crops – is presented with sentiment, without sentimentality. By letting events occur with just enough dialogue, the screenwriters make the audience dread whatever crisis might be around the corner, and allows us to celebrate with the Tuckers when those crises are overcome.

Zachary Scott (1945′s Mildred Pierce) is not and was never a household name. Second choice to Joel McCrea – who dropped out after creative differences with Renoir – Scott had typically played suave, cultured supporting protagonists or villains in his career. But his appearance in The Southerner allowed him to draw upon his Texan roots, to more genuinely portray a determined young patriarch figure tasked with keeping everybody’s spirits afloat even in the most despairing hours. There’s a bit of Gary Cooper-esque fatherliness here, which Scott utilizes brilliantly for perhaps his best cinematic performance. For Betty Field (1955′s Picnic) as the mother, her character is not relegated to just being a child-rearer. She, too, must help her husband in the fields, the construction and reparations of the farmhouse, and other daily tasks. Field could have played her character as someone needing her man to get by, but that is not the case here. As Nona, Field works with Scott as a team. And though both husband and wife might have tasks considered gendered, it always feels like a relationship of equals.

Beulah Bondi (1937′s Make Way for Tomorrow) is disappointing as Granny Tucker. The character actress, forty-six years old the year of the film’s theatrical release, had the unfortunate habit of being typecasted by casting directors into elderly mother or grandmother roles. With heavy makeup, Bondi’s character is almost a cartoon figure that obfuscates The Southerner’s rich humanism. Granny’s acid-tongued insults and stubbornness might have worked in other settings, but Bondi is overacting here. Whether this was here decision or not, it is dissatisfying work from an otherwise underrated actress. For Naish and Lloyd, it is a study of opposites. Where Naish’s weathered cynicism and gradual refusal to help his neighbors seems justified due to his character’s experiences, Lloyd’s sneering, poorly-groomed, undeveloped character reminded me of Tom from Tom and Jerry when Tom is behaving out of absolute bloodlust.

Cinematographer Lucien N. Andriot had the expanse of California’s Central Valley as his backdrop. Shot in and around Madera, California (close to Fresno) and where present-day Millerton Lake is, low-angled upward shots close to the ground or downward shots from elevated positions dominate many of the work scenes found in The Southerner. We see the details of the Tuckers preparing their land for planting and the eventual harvest. Andriot’s cameras depict these granular details between humanity and earth – including the various ways humans prepare the soil and tend to it. It is reverential, in some ways, how these actions are shown.

When stereotyping rural Americans, and particularly the American farmer, dramatists, directors, writers, all sorts of creative artists call upon the concept of rugged individualism. Rugged individualism, in the American West, implies an independent streak and assumes a rigid moral correctness among individuals in their labor. Renoir is not here to deconstruct that image nor refute it. Instead, Renoir approaches that type of narrative by presenting the Tuckers’ enterprising motivations not in isolation, but made possible with the support and concern of others. Yet that network of collective support, according to Renoir, is meaningless, without the individual motivation to even make the attempt to be an independent farmer in the first place. A level of determination – maybe even a healthy dosage of arrogance – seems necessary, too. But if that arrogance extends to a self-perception of being a master of nature, that invites recklessness and a humbling from nature itself.

Initial reception in the American South was divided. Where some condemned The Southerner as portraying people in the South as ignorant rednecks (some state officials, the Ku Klux Klan), other Southerners and organizations (like the United Daughters of the Confederacy) praised the film for its respectful portrait of an intrepid family so dedicated to their land. Poor, white Americans indeed have their narratives told more often than other groups. But even then, those in Hollywood rarely make films as tender as this.

Having passed into the public domain, numerous prints of The Southerner are available, so beware of secondhand and thirdhand copies of prints (one excellent print can be accessed here). And due to direction of Jean Renoir’s career, it is easy to discount his American works. As Renoir said himself, The Southerner is no film to be ignored, and demands a viewer’s patience and emotional understanding of the characters striving and living within.

My rating: 9/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found here.

#The Southerner#Jean Renoir#Zachary Scott#Betty Field#Beulah Bondi#J. Carrol Naish#Percy Kilbride#Charles Kemper#Blanche Yurka#Norman Lloyd#Estelle Taylor#Jay Gilpin#Jean Vanderwilt#Paul E. Burns#Hugo Butler#William Faulkner#Nunnally Johnson#Lucien N. Andriot#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

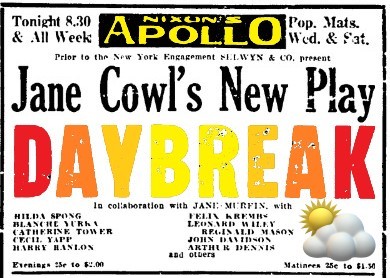

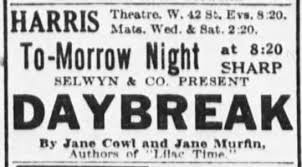

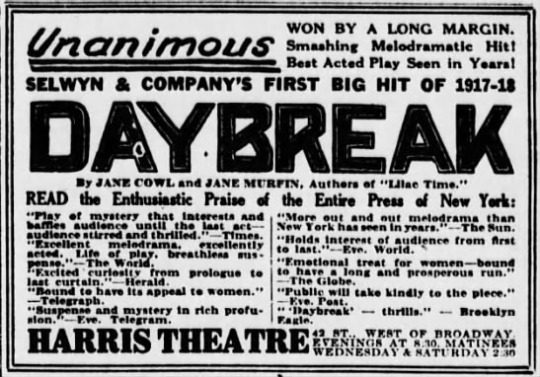

DAYBREAK

1917

Daybreak is a play by Jane Cowl and Jane Murfin. It was originally produced by Selwyn and Company staged by Wilfred North and Miss Cowl.

Successful businessman Arthur Frome, who drinks too much, pushes a newsboy under an automobile, thus causing him severe injuries. His wife Edith then becomes disillusioned with her husband and leaves him. After an absence of a few years, Edith returns to her husband but offers no explanation of her behavior. Soon, however, Arthur becomes suspicious when she and their family friend, Dr. Brent, frequently visit a house in which a small child is living. Arthur has Edith followed by the wife of one of his employees, whom he has caught stealing, and soon discovers that the child, who is gravely ill, is his own. Edith confesses that she did not want to raise their child under the influence of a drunkard and so left him in someone else's care. Soon after this confession, Arthur is shot by the husband of the woman who has followed Edith because the man suspected his wife of having an affair. Arthur recovers, however, as does the child, and through Dr. Brent's intervention is happily reconciled with Edith, with whom he plans a new life.

About the Title: The play begins at daybreak in a darkened hallway of a New York apartment. Cowl and Murfin were intent on creating the mood of daybreak without resorting to clichés that might result in laughter. They nixed a visit from the milkman and a crowing rooster. They settled on a single shaft of yellow light piercing the darkness of the quiet room. The first scene is played in silence with no dialogue to create the ‘hush’ of early morning.

Daybreak premiered in Atlantic City at Nixon’s Apollo Theatre on the Boardwalk on June 18, 1917.

“[The play] was presented to early summer reporters at Atlantic City. It will not, therefore, be an unusual sight in Atlantic City to see a large number of people going home after ‘Daybreak'.” ~ WASHINGTON POST

Edith Frome was played by Blanche Yurka, a performer that Cowl had worked with and promised to help in her career. She was later cast in another play by Cowl and Murfin. Arthur Frome was played by Frederick Truesdell, one of Broadway’s most popular leading men.

In late July and early August, the play was seen on the Jersey shore in Asbury Park at The Savoy and Long Branch at the Broadway.

Daybreak opened on Broadway at the Harris Theatre (254 West 42nd Street) on August 14, 1917.

About the Venue: The Harris (named after William B. Harris) was built in 1904 as the Lew Fields Theatre. It was variously known as the Hackett, Wallacks, the Frazee, and finally the Anco Cinema. In 1988, the interior was gutted and it was used as retail space. It was finally demolished in 1997 as part of the 42nd Street redevelopment.

This was the second collaboration between Cowl (above) and Murfin, who previously penned Lilac Time earlier in 1917. Cowl also performed in Lilac Time, which closed on June 9th at The Harris (having transferred from The Republic), allowing Daybreak to move in. Between the two plays, Lilac Time proved the more popular and more successful. In October 1918 they collaborated on a third production, Information Please, with Cowl again performing, which was less successful still. In December 1919, the pair had their most successful script, Smilin’ Through, although they wrote it under the pseudonym Allan Langdon Martin. It inspired two films and two television adaptations. In 1932, Smilin’ Through was the basis for a flop musical titled Through The Years by Vincent Youmans.

"I am really pretty tired," she said. "You see, last summer was a strenuous one. I live at Great Neck on Long Island, and my movie work was done at Fort Lee NJ. I used to get up every morning at 5:30 am and shortly after after 6:30 I was in my car and on my way to Fort Lee. At 7 I was in my dressing room, by 8 I was in the studio. Then it was work until 5 or 6, with a short time off for lunch. Back to New York and rehearsals for "Daybreak,” my new play, until all hours. ~ JANE COWL, OCTOBER 7, 1917

After the play was established on Broadway, Jane Cowl joined the road company of her Lilac Time. As of October 1917, Cowl was also seen on cinema screens in The Spreading Dawn (a title oddly similar to Daybreak), a civil war drama.

Daybreak closed on Broadway on October 13, 1917 after 71 performances.

Daybreak was filmed in 1918 starring Emily Stevens and Julian L’Estrange. It is now considered a lost film.

#Daybreak#Jane Cowl#1917#Jane Murfin#Selwyn & Co#Nixon's Apollo Theatre#Broadway#Broadway Play#Harris Theatre

18 notes

·

View notes