#Bethel Baptist Church

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

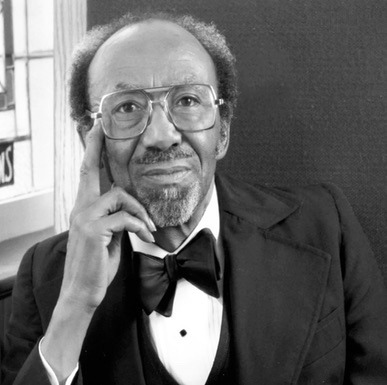

Richard Allen Harris went home to be with his Lord on Thursday, January 14, 2022, after serving as a pastor and teacher to hundreds for over 60 years. He was known for his love of the Scriptures, his love for his people, and his desire to share the love of Christ and the gospel message with others. He is remembered as a great Bible teacher, a leader in the state of Pennsylvania and in the nation for promoting Christian Education and the preservation of the founding principles upon which the United States was founded.

He was born in Doylestown, PA, to Olin and Flora Harris, the seventh child out of eight. After graduating from Central Bucks High School, Doylestown, PA, he married his sweetheart Erla Pauline (Duckworth) Harris. They were married 68 years. The Harrises had six children: Barbara Ann (Harris) Peev, Richard Dwight Harris (deceased), Dr. Allen Gene Harris, Melvin Paul Harris, Cynthia Pauline (Harris) VanOsten and Rebecca Faye (Harris) Frederick.

He attended Bob Jones University, Greenville, SC, graduating in 1959. He then attended 'Faith Theological Seminary' in pursuit of his Masters degree. While pursuing his Masters, he accepted an interim position at a 'One-room school house' where the First Baptist Church of Perkasie was holding a Sunday School ministry in Rockhill Township, Sellersville, PA. From the Sunday School, Dr. Harris and several families started an independent Baptist Church. The church, Bethel Baptist Church, was constituted on October 31, 1962, with 14 families. Ultimately, Bethel would have a membership of over 1,000.

In 1967, convicted about the need for Christian, Bible-based education for children, Dr. Harris led Bethel to start Upper Bucks Christian School. From the one-room schoolhouse, which still stands today, Bethel's campus now covers over 22 acres in Sellersville, PA. Hundreds have graduated from Upper Bucks and are serving in a myriad of ministries and vocations around the world. Dr. Harris co-founded KCEA (Keystone Christian Education Association) to support Christian Schools across the state of Pennsylvania. He also co-founded the Independent Baptist Fellowship of North America (IBFNA), served on the Council of ten for the Pennsylvania Association of Regular Baptist Churches, (PARBC) was a leader in the American Association of Christian Schools, was a director in the American Council of Christian Churches (AACS), and directed the Grace Independent Baptist Mission, (GIBM), with missionaries in over 20 countries. Dr. Harris was awarded an Honorary Doctorate from Hyles-Anderson College, Crown Point, Indiana. He also received the "Defense of the Scriptures" Memorial Award from Bob Jones University and the "Faithful Servant Award" from the Pennsylvania Association of Regular Baptist Churches. In 2000, he retired from Bethel Baptist Church. Since then, he helped four other churches; Bible Baptist Church of West Chester, PA; Kendall Park Baptist of Kendall Park NJ; First Baptist Church of Oxford PA; Shickshinny Baptist Church of Shickshinny, PA; and Dr. Harris recently helped constitute "Bible Baptist Church of Quakertown," PA.

Visitation: 7:00 - 9:00 PM, Fri. Jan. 22, at Naugle Funeral & Cremation Service, 135 W. Pumping Station Rd., Quakertown. Funeral Service: 11:00 AM, Sat. Jan. 23, at Bethel Baptist Church, 754 E. Rockhill Rd., Sellersville, viewing at 10:00 AM. Burial is private. **MASKS REQUIRED, CURRENT SAFETY GUIDELINES WILL BE OBSERVED** In lieu of flowers, we encourage gifts to be given to Keystone Christian Education Association at 6101 Bell Rd., Harrisburg, PA 17111.

#Bob Jones University#Archive#Obituary#BJU Hall of Fame#BJU Alumni Association#2022#Richard Allen Harris#Class of 1959#Bethel Baptist Church#Sellersville#Cathy Salina Harris

0 notes

Text

New Bethel Incident, Detroit 1969

Black Radicalism, Police Repression, Mass Arrests, and an Enduring Mystery

Published June 2021 by Policing and Social Justice HistoryLab/U-M Carceral State Project

Part I: Republic of New Africa

Part II: Outside the Church

Part III: Invading the Church

Part IV: Protests and Trials

Story design by Francesca Ferrara, Caroline Levine, and Matt Lassiter; based on the Detroit Under Fire exhibit section " New Bethel Incident ," researched and written by Aidan Traynor and Matt Lassiter.

On March 29, 1969, a dozen officers from the Detroit Police Department (DPD) invaded the New Bethel Baptist Church and arrested 142 African Americans gathered for the national convention of the Republic of New Africa (RNA). The Black nationalist organization was under constant surveillance by the FBI and the DPD, including multiple undercover agents and informants who had infiltrated the group. The incident began when two white officers initiated a confrontation with armed RNA bodyguards outside the church. What exactly happened is still in dispute, but one officer died in the shootout and his partner claimed that they did not have their guns drawn and were just trying to talk to the Black men. Black power and civil rights activists in Detroit did not believe this cover story and considered the confrontation to be part of the broader policy of politically motivated police repression during the late 1960s. After the 1967 Uprising, the Detroit Police Department criminalized Black Power organizations through illegal surveillance , targeted repression , and mass arrests , including a parallel campaign to destroy the local chapter of the Black Panther Party.

Prisoners inside New Bethel Baptist Church ( source )

A contingent of DPD officers responded to the shooting outside the church by storming inside with extreme force, firing wildly and hitting at least four unarmed and innocent people, taking everyone prisoner and threatening to kill them, and committing many acts of brutality. The DPD's official report claimed that a "hail of gunfire" from inside the church justified the police action, which was a lie to justify the abuses and was contradicted by all of the physical evidence and Black eyewitness testimony. The white police officers arrested all 142 people present--men, women, and children--for "conspiracy to commit murder."

Judge George Crockett, an African American and frequent critic of illegal DPD action, ordered the release of everyone wrongfully detained, which set off a political firestorm. The DPD hierarchy and the Detroit Police Officers Association (DPOA), the reactionary white-dominated union , attacked Judge Crockett in a sustained campaign. Black power and civil rights groups defended the judge and escalated their fight against DPD repression. The murder trials of two RNA bodyguards resulted in acquittals and highlighted additional evidence of unconstitutional police methods. The question of what exactly happened outside the church remains an enduring mystery.

This investigative report reproduces secret FBI and DPD surveillance documents as well as eyewitness accounts of the church invasion, inquiries by civil rights agencies, protests by Black community organizations, and records from the murder trials. Scroll down to explore one of the most controversial and polarizing incidents in the history of Detroit during the civil rights era.

"Can any of you imagine the Detroit Police Department invading an all-white church and rounding up everyone in sight? . . . Can anyone explain in other than racial terms the shooting by police into a closed and surrounded church?"--Recorder's Court Judge George C. Crockett, April 3, 1969

Part I: The Republic of New Africa and Illegal Police Surveillance

The FBI's secret COINTELPRO initiative worked with local police departments to "neutralize" black nationalist groups during the late 1960s and early 1970s ( source )

The Federal Bureau of Investigation launched its COINTELPRO against "Black Nationalist-Hate Groups" on August 25, 1967. The top-secret mission instructed FBI field offices to "disrupt" and "neutralize" Black Power organizations, ostensibly because they advocated violence. In reality, COINTELPRO was an overtly political repression campaign in service of a right-wing law enforcement agenda, part of the FBI's long history of investigating "subversive" civil rights groups and criminalizing political dissent. The FBI shared its "counterintelligence" with local police departments across the country, including the DPD. Even though Black Power groups advocated self-defense against police brutality, the FBI claimed that they were part of a nationwide conspiracy to promote "bitter and diabolic violence" in urban America. The FBI specifically warned that Black radical "urban guerillas" were plotting to ambush police officers through "acts of outrageous terror."

The Detroit Police Department conducted its own secret and unconstitutional political surveillance program, often dubbed the "Red Squad" because of its primary focus on left-wing radicals. The DPD's clandestine Criminal Intelligence Bureau spied on civil rights, Black Power, and New Left organizations--collecting intelligence to help guide illegal police crackdowns designed to repress their political activities. The DPD worked closely with the FBI as well as the Special Investigation Unit of the Michigan State Police, which shared the same mission and engaged in massive civil liberties violations of the rights of citizens during this era. All three of these law enforcement agencies had the Republic of New Africa under surveillance in the build-up to the New Bethel Incident of March 1969, including at least five undercover agents and informants and probably more.

Republic of New Africa

Cover of the RNA's 1968 founding manifesto ( source ). Read the full document here.

The Republic of New Africa (RNA) was a Black nationalist organization that originated in Detroit at the Black Government Conference called by the Malcolm X Society in March 1968. The founding meeting took place at the Shrine of the Black Madonna, a church pastored by Rev. Albert Cleage, one of Detroit's most influential Black Power leaders. About two hundred Black people from all over the United States signed the RNA’s declaration of independence stating, “forever free and independent of the Jurisdiction of the United States.”

The RNA's purpose was to establish a "Black Nation" inside the United States and to gain international recognition as a politically independent entity. The group demanded political control of the "black ghettoes" and of a large territory with a majority-Black population in five southern states. The RNA also called on the United States government pay each Black person $10,000 for reparations. The delegates elected Robert F. Williams, a Black Power leader from North Carolina who was exiled in Cuba, as their president, and Milton Henry, a well-known radical attorney in Michigan, as their vice-president. The RNA included a statement that it would achieve its goals "by arms if necessary."

RNA political agenda and manifesto (stamped "confidential" by the FBI) [ source ]

RNA leaders and members including Brother Gaidi (Milton Henry); Brother Robert, Brother Gaidi, and Brother Imari; Rafael Vierra and Clarence Fuller (who stood trial for murder ( source )

Political Surveillance and Infiltration by FBI COINTELPRO

The FBI placed leaders of the RNA under surveillance even before they formed the organization in March 1968. This memo about the RNA's founding to a top FBI official came from an agent who had infiltrated the movement and was reporting on the initial Detroit gathering. This is clear because the author of the memo is redacted, which the FBI always did for its undercover agents and informants when forced to release internal files under Freedom of Information Act requests. Note also that the RNA's Minister of Defense is redacted, indicating that the person in this key position worked for the FBI.

The COINTELPRO program was secret at the time, and the American public did not learn of its existence until 1971. It was standard practice for the FBI's undercover "agents provocateur" to advocate violence so that the FBI could justify the surveillance and repression of radical organizations. The COINTELPRO mission was to "expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize the activities of black nationalist, hate-type organizations and groupings, their leadership, spokesmen, membership, and supporters."

According to this report, provided by an FBI informant, the RNA was planning violence and guerrilla warfare.

It is hard to know for sure if RNA members who were radical Black nationalists actually advocated "warfare" against the United States, or if the FBI informant just claimed that they did to justify the law enforcement operation, or whether the leading advocates of violence inside the RNA were the FBI's "agents provocateur."

Source: View the entire memo here .

The COINTELPRO program rapidly infiltrated RNA chapters around the country, and the FBI's full RNA file (available in the Archives Unbound database) makes clear that the Bureau had more than a dozen and perhaps several dozen informants inside the organization, making up a significant percentage of its active membership.

The FBI sent several undercover informants to the second convention of the RNA, held in Detroit in late March 1969, that culminated in the New Bethel Incident. In the memo below, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover personally authorizes travel to Detroit by an RNA member from the Los Angeles chapter who is working undercover for the FBI, one of several such memos in the COINTELPRO file.

Hoover's authorization of Los Angeles informant ( source )

The FBI shared this information with the Detroit Police Department and the Michigan State Police, who also had the RNA under surveillance through their own political counterintelligence operations. In addition, based on the COINTELPRO file, it is almost certain that the FBI also had an undercover operative in a position of influence inside the central RNA group in Detroit.

This is particularly important because, as revealed below in secret FBI documents, the Bureau's own undercover agent stated that the Detroit Police Department officers initiated the confrontation outside the New Bethel Baptist Church by firing first, and that no RNA members inside the church fired on the DPD before they stormed inside. But Director J. Edgar Hoover covered up this evidence and reported to the Attorney General and Congress that the RNA radicals had shot at the police first at both stages of the encounter.

The FBI covered up the reports from at least two of its undercover "agents provocateurs" that the Detroit police officers fired at the RNA members outside the church ( source ). The redactions in this document excerpt are FBI agents or informants. View the full document here , taken from FBI files released under FOIA.

Part II: What Happened outside the Church?

"Is it reasonable to believe two white cops would approach 10-12 armed black men, with their pistols in their holsters and no weapons in their hands? . . . Is it conceivable the police behaved illegally? And would they admit it? Have they ever admitted to error in killing black people?"--People Against Racism

Corner of Philadelphia and Linwood where shooting began ( source )

The Republic of New Africa rented the New Bethel Baptist Church for a rally as part of its multi-day Detroit convention in March 1969. The church was pastored by Reverend C. L. Franklin, a prominent civil rights leader in Detroit, and located at the intersection of Philadelphia and Linwood, northwest of downtown. The RNA's rally started at 8 p.m. and ended at 11:25 p.m.

Armed bodyguards were escorting RNA leaders to their cars, and many of the people who attended the rally were still inside, when the gunfire began on the corner of Philadelphia and Linwood.

The Detroit Police Department claimed that two officers were just driving by and saw "approximately 10 to 12 Negro males with guns entering automobiles," so they stopped to investigate. Given that the DPD had the RNA rally under massive surveillance, it is not clear why the patrol officers instigated this encounter, although one theory is that they did not realize what was happening and just stumbled onto the scene.

The two white patrolmen, Michael Czapski and Richard Worobec, approached the RNA group and gunfire ensued. Patrolman Czapski ended up dead with up to seven bullet wounds. Patrolman Worobec was seriously wounded but managed to get into his squad car and drive away before crashing into a storefront.

Patrolmen Richard Worobec ( left ) and Michael Czapski ( right )

The evidence regarding who shot first is contradictory:

Patrolman Worobec testified that a "lone Negro male" shot them both without provocation.

Multiple witnesses said they heard a single shot, then another, then a sustained volley of gunfire. This could support a scenario in which the officers fired first and the RNA bodyguards returned fire.

At least two of the FBI's undercover agents reported that the patrolmen fired first, but the FBI covered this up and so the account never came out. Another FBI informant said that the RNA bodyguards fired first.

An undercover officer with the Michigan State Police claimed to have witnessed the incident and said that the RNA fired first, but he did not testify in the trials, which raises suspicion about the truthfulness of his account.

People Against Racism, an anti-police brutality group in Detroit, asked the DPD story that the white officers approached the large group of armed RNA men with their guns in their holsters and did nothing to provoke the incident, asking: "Is it reasonable to believe two white cops would approach 10-12 armed black men, with their pistols in their holsters and no weapons in their hands?" (Read the full document here ).

Detailed Accounts of the Initial Shootout

The DPD released this police radio log, which was an incomplete summary not a full transcript, raising more questions ( source )

The DPD Version: The police department provided the city of Detroit's civil rights agency with a partial and edited "transcript" of the radio log, based on communications with the dispatcher and the squad car of Patrolman Czapski and Patrolman Worobec, as well as other squad cars that responded (left).

At 11:42 p.m., Scout 10-5 (Czapski and Worobec) radioed in, “We got guys with rifles out here Linwood and Euclid.” The dispatcher sent backup, and a minute later Worobec gave a distress call over the radio and the "two officers shot" report went out.

At 11:48 and 11:49 p.m., the transcript reports that responding officers radioed in that they were taking fire from inside the church. As explained below, there was zero forensic evidence to support this claim, and it was almost certainly a cover story to justify the police action in storming the church.

The clear fabrication of the gunfire from inside the church raises the question of what else the DPD left out of or doctored in this incomplete transcript, which was provided to the Detroit Commission on Community Relations as part of its investigation of police abuses inside the church. It seems particularly unlikely that the two officers would have calmly approached a group of armed Black men at night without having their weapons drawn, as Patrolman Worobec later insisted when he claimed that most of the group scattered before a "lone Negro male" shot them both.

Patrolman Richard Worobec was later part of the notorious STRESS operation that killed at least 22 people , mainly unarmed Black males during undercover decoy operations, between 1971 and 1973. Worobec himself shot and killed two Black teenagers in a September 1971 incident that generated massive community protests. He claimed that the youth had attacked him first, but the evidence strongly indicated that he lied to cover up what really happened, and the city of Detroit paid a $270,000 wrongful death settlement to their families.

Michigan State Police Surveillance: The Michigan State (MSP) version (below) is most interesting because it proves that the law enforcement agency had undercover officers on the scene placing the RNA under surveillance, including one who witnessed the shooting.

This five-page Michigan State Police report on the New Bethel Incident is from the files of Governor William Milliken and is marked "confidential."

It provides a log of the reports to the MSP Operations office. The first entry, 12:03 a.m., notes that an MSP "Intelligence vehicle" was present at the intersection during the shooting.

The second page names the MSP undercover officer as Patrolman Landeros of the DPD, who was tasked to the state police intelligence team.

The report notes that Patrolman Landeros gave a statement to the DPD Homicide Bureau--but he never testified at the RNA trials.

This is suspicious. Did Landeros's statement contradict the account of Richard Worobec, the surviving officer?

The third page of the MSP report relays the Detroit Police Department's false story that Black suspects inside the church were wounded in a shootout, when there is no evidence that anyone except DPD officers fired inside.

The 6:50 a.m. entry corrects previous misinformation and says that "12 to 15 colored subjects" fired on the two DPD officers outside the church.

The fourth page provides an updated account of the DPD's version of what happened outside the church. It is likely that at least one of the armed bodyguards named in this entry was an FBI agent.

The entry also notes the arrest of 140+ people inside the church for "conspiracy to commit murder."

The final page lists five Black "suspects" shot inside the church by DPD officers and frames them as having fired on the police when they did not.

Excerpt from Cincinnati Field Office to FBI Director Hoover ( source ). Read the full three-page document here .

The FBI Informants: At least two of the FBI informants/agents provocateurs told the Cincinnati field office that Patrolmen Worobec and Czapski fired first, and then the RNA bodyguards returned fire.

The document at right is from a heavily redacted report from the FBI's Cincinnati office to Director J. Edgar Hoover. Based on the context, it is clear that at least one and probably two of the undercover informants were sent there by the Cincinnati office and is reporting back. Both say the "police fired first."

The document also makes clear that no one inside the church fired on the police before the DPD rained gunfire into the building.

This document is crucial not only as an eyewitness account insisting that the two white officers provoked the shootout, but also because it proves that FBI Director Hoover lied in his official report about what happened in the New Bethel Incident, found immediately below.

Director J. Edgar Hoover: The FBI Director suppressed all information in the reports he received that contradicted the Detroit Police Department's story that the violent Black radicals in the RNA opened fire unprovoked on the police officers both outside and inside the church. He then sent this memo to Attorney General John Mitchell:

Hoover provided the FBI's official coverup of the New Bethel Incident in this April 4, 1969, memo.

He attributed the account to the FBI's undercover sources, even though he misrepresented what they really said, and to the DPD. Hoover also labeled the RNA a "black extremist" group that instigated the violence both outside and inside the church.

The second page identifies RNA members alleged to have fired on the police officers, based on the undercover FBI informant's account, suppressing the information that the same informant said the police fired first and that no one inside the church shot at the DPD backup.

Hoover also sought to discredit Judge George Crockett, who released the people arrested inside the church and criticized the police abuses, by stating that the Black judge was "in close contact with officials of the Communist Party." The FBI also had a political surveillance file on Crockett, who was a left-wing lawyer before he became a judge.

Hoover concludes that "black extremists" are likely to cause more violence in Detroit.

Black Civilian Witnesses: Multiple witnesses gave statements in the murder trials or to the civil rights investigation by the Detroit Commission on Community Relations. None of them had seen what happened to instigate the encounter, meaning that they did not know whether the two white officers fired first or not. All of them stated that they saw only one Black man (only one of the RNA bodyguards) fire at the officers. This also fits Patrolman Worobec's testimony, and it means that the law enforcement accounts that a large group of RNA bodyguards opened fire were not true. Additionally, the witnesses report that the DPD backup officers were on the scene immediately when the gunfire erupted, which indicates a broader tactical surveillance operation rather than the police department's official story that the squad cars only responded when Patrolman Worobec radioed the dispatcher for help.

Kelly Zanders

Kelly Zanders, a 20-year-old Black female from Cleveland, was leaving the RNA rally and gave her statement to the defense attorneys. She said she did not see the beginning but did see a Black man with a rifle firing at another man on the sidewalk. She also said that Clarence (Chaka) Fuller, who was charged with murder, was with her the whole time and never fired a gun.

Wilbur Gratton

Wilbur Gratton, a 50-year-old Black man and RNA member from Cleveland, said in his affidavit that he saw a man shooting a rifle at another man "lying prone on the sidewalk." He also swore that Chaka Fuller was not the shooter.

Gerald McKinney

Gerald McKinney, a Black man, was driving by and not involved with the RNA. He said he saw a man with a "rifle and he was firing into the back of the police car." McKinney also said that the other DPD officers were already on the scene during the initial shootout.

William Barry, Jr.

William Barry, Jr., a Black man, was riding in the car with Gerald McKinney and said he saw a man on the sidewalk shooting toward the police car. Barry also stated that 15-20 police officers arrived "within seconds," which again raises questions about the veracity of the police log provided by the DPD.

Max Hardeman

Max Hardeman, a Black man, was interviewed for the investigation by the Detroit Commission on Community Relations. He was across the street and said he saw an RNA bodyguard "fire several blasts" at a police officer. Like every other civilian witness, Hardeman saw only one shooter.

The DCCR report concluded that what happened outside the church "has proved impossible to recreate" but was harshly critical of the DPD's actions inside the church, examined next.

Part III: The DPD's Invasion of the Church

"Were basic constitutional rights flouted by acts of reprisal generated from uncontrolled anger over the slaying of a fellow officer?" -- Detroit Commission on Community Relations, investigative report of New Bethel Incident

All of the civilian witnesses agreed that the solitary man who shot at the white police officers did not flee into the church, as the DPD claimed the shooters did in its official report. Whether the two officers fired first or not in the encounter outside the church is still uncertain to this day. What happened next is not. The contingent of DPD officers on the scene fabricated a story that multiple RNA shooters fled into the church, and that "black extremist" radicals inside the church fired at the officers outside, to justify the armed invasion and brutal retaliation that followed. All non-police testimony and all forensic evidence reveals that no one inside the church fired a shot and that every bullet came from a police weapon.

RNA members held prisoner and "herded up like cattle" after the police invasion; photograph from a legal defense pamphlet by the radical League of Revolutionary Black Workers ( source ).

There were 142 African Americans, including many women and children, still inside the New Bethel Baptist Church after the RNA rally when the police assault began around five minutes after the sidewalk shooting. The police contingent of at least a dozen officers fired around 100 rounds into the church before and during the invasion. The Black civilians took refuge and later described a campaign of racial terror and indiscriminate vengeance by the invading officers, even as they tried to surrender and after they were prisoners. The police officers who invaded the church arrested them all and booked everyone present for conspiracy to commit murder.

Source : View the full DCCR investigation report here .

CLICK THE HEADER TO READ THE ENTIRE PIECE, AS IT'S ABOVE THE LIMIT FOR TUMBLR POSTS

CLICK HERE TO READ AND SEE ALL THE PICTURES

#Detroit#RNA#Republic of New Afrika#New Bethel Baptist Church#New Bethel Incident#Detroit 1969#Rev C.L. Franklin#Chaka Fuller#dpd#white supremacy#cointelpro#March 29#1969#march 29 1969#msp#hoover#white lies

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early in the morning on Sunday, June 29, 1958, a bomb exploded outside Bethel Street Baptist Church on the north side of Birmingham, Alabama, in one of the segregated city's African American neighborhoods. The church's pastor, Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, was a civil rights activist working to eliminate segregation in Birmingham. Bethel Street Baptist had been bombed before—on Christmas Day 1956—and since then several volunteers had kept watch over the neighborhood every night. Around 1:30 am, Will Hall, who was on watch that night, was alerted to smoke coming from the church. He discovered a paint can containing dynamite near the church wall, which he quickly carried into the street before taking cover. The paint can had between 15 and 20 sticks of dynamite inside, and as it exploded it blew a two-foot hole in the street and broke the windows of several houses. The church's stained glass windows, which were still being repaired from an earlier bombing, were also damaged. Police told church leaders there were few clues as to the culprit's identity or motive, but a passerby reported seeing a car full of white men in the area shortly before the bomb was discovered. The Rev. Shuttlesworth praised Mr. Hall for his brave actions and quick intervention, which surely saved the church from ruin, while also condemning the attack. "This shows that America has a long way to go before it can try to be called democratic," the Rev. Shuttlesworth said.

#history#white history#us history#am yisrael chai#jumblr#republicans#black history#June 29 1958#June 29#Bethel Street Baptist Church#Birmingham#Alabama#democrats#Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth#Fred Shuttlesworth#December 25#December 25 1956#bomb#bombed#terrorist#white supremacy#Will Hall

1 note

·

View note

Text

#There Have Been At Least 100 Attacks On Black Churches Since 1956#Black churches#christians#Black churches attacked by racists#mother bethel#AME#Baptist#Methodist

0 notes

Text

Decades after a historic Alberta cemetery was reclaimed from the forest, a group of volunteers is preserving both the graves and the stories of the Black pioneers who were buried there. Headstones will soon be placed to mark the burial plots of 13 men, women and children interred at the Bethel Baptist Cemetery, one of the last remaining traces of the once-thriving Black settlement of Campsie, Alta., about 135 kilometres northwest of Edmonton. Descendents of the settler families are supporting the efforts of the Barrhead Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-Day Saints and the Barrhead and District Family Community Support Services in restoring the cemetery and fundraising for the stone markers.

Continue Reading

Tagging @politicsofcanada @abpoli

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

In our inaugural discussion, we explore the significance of open and affirming places of worship and discuss the intersection of faith and queerness. Our fantastic panel of local thought leaders present viewpoints from various religions, denominations, and lived experience:

Anthony H. Crisci, CEO of Circle Care and attendee/volunteer leader of St. Paul’s on the Green

Rabbi Evan Schultz, Senior Rabbi of Congregation B’nai Israel Bridgeport

Rev. Kym McNair, Baptist Minister

Rev. Ryan Gackenheimer, Pastor of First Congregational Church of Bethel

Link to additional references on the YouTube page

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rev. Dr. Charles Kenzie Steele (born February 17, 1914 - August 19, 1980) was a preacher and a civil rights activist. He was one of the main organizers of the 1956 Tallahassee bus boycott and a prominent member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. On March 23, 2018, Florida Governor Rick Scott signed CS/SB 382 into law, designating portions of Florida State Road 371 and Florida State Road 373 along Orange Avenue in Tallahassee as C.K. Steele Memorial Highway.

He was the son of a coal miner, an only child. At a young age, he knew that he wanted to be a preacher, and he started preaching when he was 15 years old. He graduated from Morehouse College. He began preaching in Toccoa and Augusta, Georgia, and in Montgomery at the Hall Street Baptist Church (1938–52). He moved to Tallahassee, where he started preaching at the Bethel Missionary Baptist Church. He met Martin Luther King Jr. when he was on his way to Tallahassee.

The Tallahassee bus boycott began in May 1956, during the Montgomery bus boycott. Like other bus boycotts during the Civil Rights Movement in America, it started because African American people were forced to ride in the back of the bus, and when two students refused to give up their seats to a white woman, they were arrested. An organization was formed to protest and boycott the city bus system. The organization was called Inter-Civic Council and he was elected president. He and other protesters boycotted the system by starting carpools and the bus system stopped for the first time in 17 years on July 1. He was arrested many times during this period.

He was the lead plaintiff in the school desegregation suit, which led to the desegregation of public schools in Leon County. He was a part of many other protests, marches, and boycotts, where he helped to accomplish integration in many public places. He helped Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. organize the SCLC in 1957. He was made the First Vice President under Dr. King at the time of the formation of SCLC.

He participated in the Selma to Montgomery marches in 1965. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

On December 25, 1956, Ku Klux Klan members in Alabama bombed the home of civil rights activist and co-founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth. Rev. Shuttlesworth was home at the time of the bombing with his family and two members of Bethel Baptist Church, where he served as pastor. The 16-stick dynamite blast destroyed the home and caused damage to Rev. Shuttlesworth’s church next door, but no one inside the home suffered serious injury. Undeterred by the Klan’s assassination attempt, Rev. Shuttlesworth proceeded as planned with the December 26 protest rides.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

My first memories of Juneteenth began in church. I grew up in a predominantly Black section of Jamaica, in the New York City borough of Queens. Our small congregation at New Bethel Baptist Church consisted of Caribbean immigrants such as my Haitian-born mother, native-born New Yorkers such as me, and migrants from across the South, including Texas. As new parishioners arrived, they transplanted their food, culture, and folkways into our church rituals and traditions.

My mother prided herself on the excellence of her Haitian cooking, especially dishes such as soup joumou, stewed chicken accompanied by rice and beans (black or red), and the sweet coconut dessert she occasionally prepared for other congregants. But we also relished those special occasions at church when the cozy upstairs room that doubled as a kind of banquet hall was filled with the rich aroma of Southern soul food: cornbread, fried fish, red velvet cake.

This was the early eighties, my elementary school years. One Sunday morning, as I sat on a light brown pew in New Bethel’s sanctuary, I was rapt as parishioners from Texas took to the pulpit and told a fascinating story of enslaved African Americans who didn’t hear news of their liberation until Union general Gordon Granger issued an order in Galveston on June 19, 1865, more than two months after Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House, in Virginia. I was reminded of my mother’s stories about the Haitian Revolution, in which slaves overthrew French rule and, to much of the world’s surprise, achieved independence in 1804. That uprising inspired emancipation movements around the globe, though it would be another six decades before freedom for the enslaved reached America’s shores. After the service I overheard fervent conversations about slavery and the need to teach young children like me to never forget.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know everyone talks about pastor’s wife Beyoncé, but this gif in particular always reminds me that we are, at most, three universes away before we hit Sister Beyoncé Williams, the wife of the associate pastor of Bethel Full Gospel Church. She’s divorced by 33, but swiftly recovers as First Lady Beyoncé Williams-Price of New Calvary Missionary Baptist Church. She gets every choir solo.

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Onsite & Design | Mt Bethel Baptist Church

0 notes

Text

I'm not religious have considered myself spiritual for a long time but I keep getting this weird urge to go back to church (left when I was 12 ~ 14 years old raised in a horrific hybrid of Baptist and Fundamentalist but somehow ended up in a Catholic school for 4 years of my early childhood) it's probably because 100% of the people I knew from my past are super religious now at least the few who did not lose their minds to drug addiction or went to prison or just vanished without a trace. IDK though my oldest cousin joined a cult (church of Bethel) and while I'm so thankful she's alive and healthy it does pop into my head sometimes like I wonder where she is now? Oh yeah, the cult.... Maybe that's what I actually need to do form a new one

0 notes

Text

CulturalShocker of the Day: Aretha Franklin

-Born March 25, 1942

-Honored the "The Queen of Soul" and Rolling Stone Magazine twice named her as the greatest singer of all time.

-From Memphis, Tennessee and raised in the Baptist church. Her Father, C.L. Franklin was a minister and civil rights activist.

-Some of her iconic hits include: "Ain't no way" (March 1968), "I Say a Little Prayer" (July 1968), and "Respect" (1967)

-Aretha was, much like her father, a civil rights activist. She provided money and covered payrolls for activist groups by performing concert benefits. She also advocated for Indigenous rights as well

-She received her Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1979 and became the first woman inducted into the Rock and Roll hall of Fame 1985. Many tributes have been performed in her honor which include: Black Girls Rock tribute (2018), American Music Awards (2018), and The 61st Grammy Awards

-She has 44 Grammy nominations and 18 wins

-She died on August 16, 2018 from pNET and the memorial service was held at her home church, New Bethel Baptist Church.

*All information and comes from Wikipedia.com*

0 notes

Text

Join us for Healthy Conversations at Bethel Missionary Baptist Church in Dayton, Ohio!

The event will be streamed live on YouTube on the Bethel Dayton channel.

Listen in for a discussion with Dr. Alonzo Patterson, Dr. Tanisha Richmond, Marquetta Colbert, and Dr. Patrick Spencer.

Visit richfeet.org to schedule an appointment or call/text 937-228-3668.

🌟 #HealthyConversations #CommunityHealth

0 notes

Text

Mapping the Lost History of the Tenth Street Historic District

The driveway behind SMU archaeologist Katie Cross and kinkofa co-founders Tameshia Rudd-Ridge and Jourdan Brunson was once the entrance to Elizabeth Chapel, which is named for the wife of Tenth Street founder, Anthony Boswell.

Much of Tenth Street's history has been lost to demolition and city policy.

A new effort aims to help people visualize what once was, with the goal of appreciating and saving what remains.

Much of the historic Freedman’s town of Tenth Street has been lost to time and demolition.

Even a Landmark designation from the city three decades ago did little to stop the destruction of its homes in this pocket just east of Interstate 35E, in Oak Cliff.

Piecing together that lost history is daunting.

But SMU archaeologist and doctoral student Katie Cross is using technology to combine the stories and history of Tenth Street with geographic information systems (GIS) to tell the community’s story.

It’s part of a collaborative effort called “If Tenth Street Could Talk,” which includes kinkofa, a technology company that provides resources for Black families to document and preserve their stories.

(More of Cross’ work can be found here.)

Tameshia Rudd-Ridge and Jourdan Brunson, the co-founders of kinkofa, worked with genealogist Dolores Rodgers to record oral histories, digitize photos, and research genealogy to create a digital museum of Tenth Street.

They’re also collaborating with Remembering Black Dallas, the Dallas Public Library, and the Tenth Street Residential Association. The work is possible thanks to a grant from the Library of Congress.

“I was combing through city directories and census data. Sanborn maps,” Cross says. “I was looking at aerial imagery, and then putting it into one place. I was georeferencing them, which is putting them on top of where they are in the real world on a map.”

They can also attach to the map the oral histories collected by kinkofa and other organizations like Remembering Black Dallas.

“We can look at how infrastructure impacted the community,” she says. “And when you put it all together, it shows this narrative of a vibrant neighborhood despite the infrastructure that disrupted it.”

Present-day Tenth Street is bounded by Interstate 35, East Eighth Street, and Clarendon Drive at the eastern edge of Oak Cliff, not far from the Dallas Zoo.

But the community began in the 1880s, south of the Trinity River, as formerly enslaved people settled and began buying lots and homes.

By the turn of the century, those families had created a community with churches, a school, and small businesses.

By the 1950s, nearly 2,000 residents lived here.

At one point, it had a hospital whose doctor lived next door.

Jim Crow-era policies began to change that community, separating blocks by the race of homeowners.

Black homeowners were sometimes forced to literally move their homes to nearby blocks because they were located on a “White” block.

Redlining and disinvestment by the city followed.

In the 1960s, I-35 was routed through the neighborhood, cutting it off from the rest of Oak Cliff while demolishing neighborhood businesses.

In 2010, the city passed an ordinance that allowed homes in Landmark Districts to be torn down if they were smaller than 3,000 square feet.

Nearly all the homes in Tenth Street fit that bill.

Fourteen years later, the Dallas City Council voted to repeal the ordinance after years of demolitions.

The area’s last commercial building stands vacant and boarded up.

At one point, Simpson’s Corner Store was one of 40 businesses in the neighborhood.

Greater El Bethel Missionary Baptist Church is still holding Sunday worship, but it’s the only church remaining out of the eight that were once present in the neighborhood. Image

Members of the Greater El Bethel Missionary Baptist Church gather in the 50s in their Sunday finery. From the collections of the Dallas History & Archives Division, Dallas Public Library

Rudd-Ridge learned firsthand how history disappears when she began researching her own family.

When she found that jazz trumpeter Clora Bryant was a cousin of her great grandmother, she began to search for her home.

She looked on Betterton Circle, but found an access road at the edge of a highway instead.

“Literally the highway is where my family home was supposed to be,” she says. She related her frustrations while on Remembering Black Dallas bus trip with the late George Keaton and Tenth Street resident Larry Johnson not long after.

“They said, ‘Well, what are you going to do about it?’” she says.

That was almost three years ago.

Since then, Rudd-Ridge and Brunson have worked to document the history of the neighborhood—even when longtime residents sometimes question whether their stories are important. Image

In a photo from the 1950s, three generations of the Sims family—Lobie Washington Sims, her daughter, Othella Sims, and her grandchildren— gather on the front steps of their Tenth Street home. Dallas History & Archives Division, Dallas Public Library

“Your lived experience is valuable,” Rudd-Ridge says. “The every day is really what makes a people’s history.”

Brunson said that similar work the organization has done in Tulsa found that people are sometimes unaware of their history. They’ve found that to be true in Tenth Street, too.

“They don’t know the significance of the heyday of the community, or even the current issues they’re battling,” he says.

Cross says she hopes that the work done in Tenth Street will force a change in what is considered worthy of preservation.

“Historic protections aren’t perfect,” she says. “They do not stop destruction. We need to rethink how we do historic preservation.”

A broader understanding of historical places and why they’re important will help. Rudd-Ridge says she hopes Tenth Street residents now have the city’s attention, and that there is momentum to change what happens in the community.

Eventually, they’d like to see the neighborhood showcased as one of the few intact Freedman’s towns in the state, and cement it as a Black cultural destination.

“Our goal is to keep applying positive pressure,” she says.

In the meantime, they’ll continue to help people visualize the history they can’t see, one map and story at a time.

Freedmen's Settlements

Freedmen's Settlements were founded in Texas between 1865 to 1930.

These early settlements refelcted the difficulties of black landowners in the post civil war south.

Uncovering their history requires ethnographic, archeological, archival, and participatory research.

Community histories are scattered across private collections, archeological surveys, and in elderly residents’ memories.

FREEDMEN'S SETTLEMENTS.

Freedmen’s settlements, otherwise known as Black settlements, freedom colonies, or freedmen’s towns, are historically significant communities founded across the South, including Texas, from 1865 to 1930.

Black Texans obtained the land upon which these settlements were founded via cash purchase or adverse possession, often in flood-prone bottomlands on the edges of plantations and city boundaries.

Accumulating land in Texas was no small feat for the formerly enslaved.

Since the state's inception in 1845, property laws privileged the White majority, particularly slaveholders.

The land redistribution discussions of Charles Sumner, Thaddeus Stevens, and other Radical Republicans and Special Field Order No. 15 issued by Gen. William T. Sherman on January 16, 1865, that suggested the federal government consider providing all ex-slaves with "40 acres and a mule" proved baseless.

After the Civil War, the Texas Freedmen's Bureau held no property for redistribution to freedmen, and the agricultural system of sharecropping came to dominate.

Most freed persons remained in the countryside and engaged in farm tenancy with White landowners as day laborers, sharecroppers, or share tenants.

The State's Black Codes legislation and the 1866 Homestead Act of Texas banned African Americans from accessing the 160 acres in public land available to each White settler.

Freedmen and their families moved to settle in segregated "quarters" within unplatted and unincorporated lands adjacent to established White towns.

As in the case of Barrett Station, Harris County, some Black settlements existed for years before residents formally purchased or preempted land.

When these families managed to save enough funds to purchase property, Whites would either not sell to them or cancel informal contracts shortly before the final deed transfer.

Black landowners risked becoming the targets of White supremacists who felt threatened by Black economic advancement.

Freedom colonies resulted from clusters of landowning Black families in seeking security in this climate of racial terror.

Freedmen's strong desires for land, autonomy, and a safe refuge from Whites motivated formation of these independent Black settlements.

The relationship between land accumulation and place-making became clear when Black farm and homestead owners in Texas went from owning 2 percent of all Texas farmland in 1870 to 31 percent by 1910.

However, most formerly enslaved Texans settled in the only areas available to them—bottomland in low-lying areas.

Up in the sand hills, down in the creek and river bottoms, and along county lines, hundreds of Black settlements came into being throughout Reconstruction.

With their physical locations hidden and their economies based on self-sufficiency, Black formerly enslaved Texans were not only able to avoid falling prey to sharecropping, debt bondage, and White violence but further created complex and dynamic cultures that revolved around family, tradition, and education.

The Black settlements that expanded across the state from East Texas were individually unified by church, school, and residents' collective sense of community.

Oral tradition and interviews with descendants characterized relationships with White, Mexican American, and Indigenous neighbors as somewhat complicated or traumatic at times.

While settlements in urban centers are most well-known, hundreds are present throughout Central and East Texas.

Freedmen’s Town in Houston’s Fourth Ward was a mecca for formerly enslaved Black Houstonians who built churches and schools and paved their own roads with bricks.

Travis County’s Robinson Hill and Masontown were among Austin’s commercial hubs.

Ministers and their congregations took the lead in founding some communities such as St. John Colony in Caldwell County.

At County Line (now Upshaw) in Nacogdoches County, and at other places, groups of siblings formed the core pioneers of settlements.

Some counties have between twenty and forty small kinship-based settlements, with some colonies becoming incorporated towns, including Independence Heights, Ames, and Kendleton.

Halls Bluff, Simon Springs, and Fodice in Houston County and Grant's Colony in Walker County are just some of the settlements anchored by farmers and landowners.

Cemeteries, homesteads, churches, and schools made these communities recognizable until the years of the Great Depression, World War II, and the Great Migration when residents moved away due to various factors, including land dispossession and the search for economic opportunity and a respite from violence.

Without full-time residents, land loss, sprawl, and gentrification destroyed these once secure, self-reliant communities that soon disappeared from public records and maps.

At present, Black settlement boundaries are either distilled to urban neighborhood boundaries or are simply no longer on maps.

Some patterns of community origin are discernable, while gentrification, natural disasters, resource extraction, and environmental injustice catalyzed mass exodus from family lands and population decline.

Despite declining populations in these freedmen’s settlements, former community residents make pilgrimages from major cities back to settlements to celebrate their heritage, and efforts have been made to commemorate this history.

For example, Shankleville in Newton County, founded by a formerly enslaved couple named Jim and Winnie Shankle after emancipation, has historic churches, cemeteries, and a homestead on the National Register of Historic Places, and descendants organize annual festivals and homecomings which support fundraising which supports cemetery stewardship and preservation projects.

The evidence of Black settlements’ existence is preserved in oral history and eyewitness testimony in the effort to save important community history which is often forgotten as elderly residents pass away.

Further efforts to protect these settlements using policy under the guidelines of the National Register of Historic Places are complicated by standards for designation that do not cover the specific attributes and characteristics of freedom colonies.

Identifying the more than 550 Black settlements founded in Texas requires extensive ethnographic, archeological, archival, and participatory research.

Community histories are scattered across private collections, archeological surveys, and in elderly residents’ memories while remaining historic structures decline in the absence of full-time caretakers.

Since 2014 the Texas Freedom Colonies Project (TXFC Project) under the direction of Andrea Roberts has amassed the origin stories, locations, and public histories of 357 Black settlements and partnered with descendants to map more than 200 communities within its online atlas.

0 notes