#Bering and Wells Holiday Gift Exchange

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

Hi, amtrak12! I'm your Bering & Wells gifter this year, and I'd be happy to provide you with a story of a sort that might make your heart sing. I write AU and canon-compliant stuff, though I do tend to avoid full-on tragedy and anything truly explicit--apologies for that, if it's too limiting, but I bet you'd find any attempts I'd make at those to resemble lumps of coal rather than true gifts. In any case, I'm looking forward to hearing your thoughts!

OMG I totally feel you on the explicit smut. I, too, should not be trusted to write it! LOL And I think the Bering and Wells fandom gave ourselves enough tragic fics during our great Angst War of 2013 😜 So those restrictions are totally fine with me!

Oh, I'm so excited for this! Let's see...

My general likes:

The S3 yearning during Helena's pokeball era XD I will read anything where Myka sneaks Helena's hologram out late at night to talk to her.

Helena mentoring kids. I hate S4 and I hate Instinct, but I do agree with its premise that Helena is fantastic with kids and would love to play a significant role in a child's life again.

Warehouse artifact shenanigans, especially during inventory. Always a classic.

Dislikes:

Character bashing (though feel free to criticize Myka's dad more than the show did)

Season 4 -- everything except Steve's resurrection is just a big no from me. Though if you want to use Abigail in the fic, you can. I did like her.

Season 5 -- I didn't even bother watching this one. I noped out right before the S4 finale and I don't regret that decision at all.

I am more than happy with an AU future where the warehouse and everyone are magically alive (and Leena never died). I don't even need an explanation for it. 💜 Canon S1-3 settings or even pre-series settings are also good with me.

If you'd like some specific prompts to get you started....

Canon Setting Prompts:

Helena has to work with Pete to help Myka -- could be something as big as Myka being in danger. Could be something as simple and domestic as picking out a birthday gift. Myka has two important people in her life and I, at least, am incapable of thinking about her and Helena without also inevitably thinking about Myka's relationship with Pete. (As completely platonic BROTP, of course. No Myka/Pete romance, either past or present :S But that's probably assumed in a B&W gift exchange.)

Helena's past work with WH12 shows up in small ways -- she recognizes an artifact during inventory, she wrote one of the shelving tags, or they find a report she filled out over a hundred years ago when they're refiling in the archives. Could be angsty because it's S3 and Myka misses her. Could be comforting because Helena's back and every reminder helps her feel like she's home. Could be any tone in between.

Myka having to adjust to having Helena living at the B&B, either in S2 when they're still getting to know each other or in a happy, post-S3 world where Helena's working with them again. Or maybe Myka notes that it isn't an adjustment for her at all because it feels so natural to have Helena living with them. Just domestic introspection outside of the chaos of the job.

AU Setting Prompts:

I'm a huge sucker for soulmate AUs. The tattoo style markings are my favorite premise, but if you have another favorite soulmate set-up, feel free to use that instead. I just think it's neat to explore the impact soulmates would have on the world building and relationships. Are soulmates formed or pre-ordained? How do soulmates work when the other person was born in a completely different era than you?

I know we had a firefighter/paramedic AU series way back in the day, but I wouldn't be mad to see it come back. I've been watching a lot of 9-1-1 lately LOL

Lawyer AUs are also always delicious. The tension that comes out in the courtroom -- HNNG!! There's a reason I have sexual headcanons for Alex Cabot (Law & Order SVU) and every single female defense lawyer and judge she came across ROTFL (And no, this doesn't contradict the no smut agreement, you and I have made, anon. One of my most formative ships was Doctor/Rose. They were heavy on the Unresolved Sexual Tension, and I firmly believe UST should make a comeback in media/fic. It's about the denial, it's about the what if's, the almost's, GUH!)

Hopefully, that gave you enough variety to inspire you without overwhelming you. I will be happy with any length of fic. So if you're the type of writer who thrives on deadlines and/or can write plotty fic in a short time, great. If you're a slower or shorter writer, also great! There seems to be a trend where readers only want 10k+ fics (at least in my current fandom), but I love short stories! I think you can do a lot in just a single scene. So write whatever length you're comfortable with, and feel free to use these ideas as just a starting point. I'll be thrilled to read whatever you come up with :) Thank you so much! 💗

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

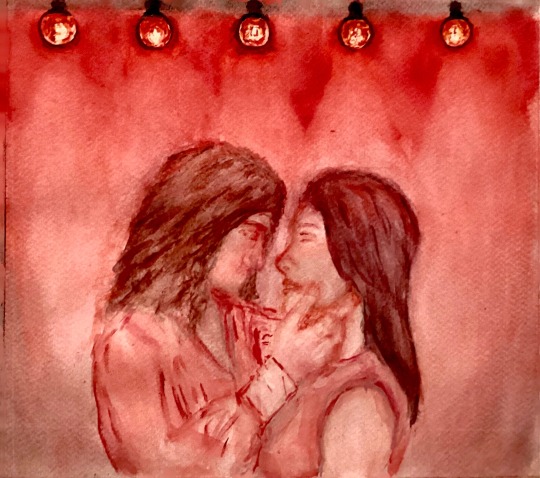

Happy gift exchange @apparitionism !!

inspired by your fanfic Confection (if myka was a little bit braver and quicker)

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! I'm your Bering and Wells Holiday Gift Exchange gifter. I'm a fic writer, and I really appreciate specific prompts :) I'm happy to write anything except for smut.

Hello, thank you! :)

I have some fic ideas that I've posted in my wip pile on Ao3 that I'd love to see turned into actual stories! Especially the one with the trident, but also any of the others.

I'm always intrigued by the idea of Helena having chronic pain from the bronzer, I'm pretty sure that's been done before, but why not do it again? :D

If none of those speak to you or you have some more questions, feel free to send another ask and I'm sure we can figure something out :)

#bering and wells holiday gift exchange#w13#ask the blogger#gift exchange ask#answered#anon#not f#dec'24#27.12.24#my w13#Bering and wells#warehouse 13#ao3 link#mine#bering and wells holiday gift exchange 2025

1 note

·

View note

Text

Happy Bering and Wells Day! This year, @apparitionism gave me a wild set of prompts to play with, so here's what I ended up with.

@b-and-w-holiday-gift-exchange

#warehouse 13#helena wells#myka bering#bering and wells#b-and-w-holiday-gift-exchange#apparitionism#bering and wells exchange

343 notes

·

View notes

Text

IT'S BERING AND WELLS HOLIDAY GIFT EXCHANGE TIME!

Happy American Thanksgiving, and happy Bering and Wells Holiday Gift Exchange sign-up opening day!

The gift exchange is open to anyone who wants to make a fic, art piece, gif, or any other fandom-related gift and exchange it with a fellow Bering and Wells fan. Here's the schedule:

Message or ask me via this blog or my personal account (@kla1991) anytime between now and the winter solstice, December 21st, and say you'd like to participate. Also say whether you're willing to open your askbox to anonymous messages or if you'd prefer courrier service to speak to your secret gifter.

On December 25th, you'll receive the username of someone else who signed up; this is your giftee! You should also double-check that your inbox is open and accepting anonymous messages on this day if you're participating that way.

Between December 25th and New Years, January 1st, you will anonymously communicate with your giftee to receive prompts about what type of fandom stuff you make and what type of gift they might like to receive. You'll also give prompts, if you have any, to your gifter! If at any point you have questions about how to do this, reach out to me.

You will then have from January 1st until Valentine's Day, February 14th, to create a gift, and they'll all be posted on tumblr on the 14th!

Feel free to message me with any questions, and please spread the word!

#bering and wells holiday gift exchange 2025#bering and wells#fandom event#warehouse 13#holiday gift exchange#myka bering#helena wells

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Real

Can’t believe tomorrow is a particular Wednesday already; this season has rushed in like the most foolish of fools, and as a result I’m rushing to push out this new holiday story... because I too am a fool. This is set post-series (including the nonexistent season), though not by much, as the first little bit will make clear. It’s kind of all about fallout. And who wants what, and why, and whether they’re willing to work, wait, and do other things that probably start with “w” to get it. Anyway, season’s greetings to all—and to all (including, eventually, Myka and Helena, I promise) a good night.

Real

“She’s back,” Artie announces one autumn night, and before anyone (Myka) can fully register what that might mean...

...she is.

Is, is, is... a distillation of so much of what Myka instantaneously knows again as possibility, as hopes and wishes jolting back to life, as again (still) the only presence that instantly makes Myka aware of herself as a body, one that responds with barely controllable fervor to that presence—that other body.

Artie goes on saying words, “reinstated” and “agent” among them, but the roaring of Myka’s blood drowns them out.

She fears she will spontaneously combust. She would rather spontaneously combust. That would be better than having to consciously keep from spontaneously combusting, in response to Helena existing, to her moving and speaking, in a proximity that Myka should prize but that her body, fervently responding, informs her is completely insufficient.

Myka escapes as soon as she can, to sit in the dark of her room, to sit and process, but her usual, reliable processing processes fail her.

They always have, where Helena is concerned.

All she does is sit, empty but for the replaying of Helena’s entry into the dining room, her stride so sure, her aspect so unlike the dismissive, shrinking shrugs of Boone... that had sent Myka’s soul soaring.

Helena had greeted them all with good humor, her manner and words to everyone so convivial. So convivial, but also: to everyone, and that is what finds clawed purchase in Myka’s heart, here in the dark.

Here in the dark, Myka viciously tells herself that she deserves no special acknowledgment. Why would you?

She also tells herself, This will get easier.

****

In some ways it does. For example, Myka’s shock at, and subsequent need to recover from, each new sight of Helena lessens somewhat. Or maybe it’s that her body becomes accustomed to absorbing the impact.

In others, it profoundly doesn’t.

Case in painful point: one evening when they’re all cleaning up after dinner, Claudia says to Helena, “So can I ask you something?”

“Clearly you can. You just did,” Helena bats back, in play, and envy stabs Myka.

“You’re as bad as Artie,” Claudia groans. “But here goes: are you still seeing that lady?”

Terror appropriates envy’s knife, gashing anew. Myka has not let herself begin to imagine how to get such a question answered, and here Claudia just says it while lowering a stack of dirty plates into the sink.

Helena’s airy reply: “Still the case. Obviously we’re long-distance at the moment.”

Something previously un-knifed in Myka collapses at that “obviously.” Obviously. Obviously. Obviously, the Warehouse return had not entailed a renouncing of Helena’s non-Warehouse connections. As Myka had obviously, she now sees, believed��hoped!—it would.

The depth and breadth of her error sends her to her room again, lightless, wounded, empty, waiting for time to pass until she once again has something to do.

Such as a retrieval with Pete.

The next one of which proceeds well—it’s not a big, dangerous deal, but rather a matter of a sad, not villainous, loner seeking connection via an artifact-compromised comic-book message board. Pete’s his enthusiastic self about the comics of it all, and Myka lets it lull her into a near-trance of this is how it used to be, before everything.

Until they’re on the plane home, when Pete says, “So H.G.’s back.”

“Thanks for the update,” she says, bracing herself, because of course that won’t be all, because that would be too easy.

“And what about that girlfriend?”

“What about her?” Well, that was stupid: asking some reflex question she doesn’t want answered. She braces herself again.

“You think she’s her one?”

That’s worse than she’d imagined. Myka doesn’t want to go anywhere near that Schrödinger-box, for fear that peeking inside would reveal a very dead cat. Would in fact be the deciding factor in that cat’s demise.

After a stretch of silence, Pete says, “Bet she’s not. So what are you gonna do about it?”

What does he mean? Do about the girlfriend not being, or being, Helena’s one? Do about Helena being back in the first place? She would rather avoid nailing that down—another let’s-not-look Schrödinger box.

“I’m going to ignore it,” she says.

“That’s not healthy. I mean, I get it, but it’s not healthy.”

He coughs ostentatiously. Meaningfully? Myka doesn’t know. Can’t tell. Won’t ask. She hates how she feels compelled to leave this cat in limbo too, just so she can shift away from any potential situational consequences.

If only she had resisted the pressure to shift her definition of love.

She tries for resistance now, even though it’s too late: “I’m not going to try to keep her from doing what she wants to do.”

He cocks his head in that exaggerated what-are-you-saying way. “I thought you might though. Try.”

Myka is tempted to demand, “Why would you think that,” but she knows why he would think it, and revisiting that fight is an impossibility. Especially now.

“But you’re not trying,” he says. His tone, though, ratchets down the danger. It’s a relief. “So why not?”

Now Myka’s tempted to give some indignant “I don’t have to justify my behavior to you” answer... and yet. She does owe him more than that. Especially now, having misled him so severely before, she owes him some decent measure of honesty. So she says it as plain as she can: “Because people should do what they want to do.”

“Huh.” He puts on his “thinking” face—the real one, not the cartoon. “But you’re not doing what you want to do.”

“What?” Myka says, playing dismissively dumb. Hoping he’ll give some dumb response.

“You want to stop her doing what she’s doing.” Myka shakes her head at that, trying to pretend it’s dumb, but Pete rolls his eyes. He sees the weakness. How can he be getting her so right in this when he got her so so so wrong before? But then again she’d got herself wrong... “So why wouldn’t you do what you want to do?” he finishes.

Want, want, want. Myka wishes he would quit using the word.

Yes it’s her fault for using it first. Yes she should have shut him down forcefully to begin with. Yes that applies to situations preceding this one.

In any case, wanting is pointless. It literally does not matter: its only product is empty space, a horrific gaping sink, a vacuum as vast as space itself.

So she says, as pedantically as she can, “Because if one person’s wants affect another person’s wants, that’s a different category of... you know what? Never mind.”

“You only ever say ‘never mind’ when you know I’m right.”

“What? I say ‘never mind’ a lot.”

“Which means...” He taps his temple.

“No. No it does not.” But she does smile.

Pete bobs his head as if she’s actually agreed with him, and so they end on a familiar, jokey note. It’s far better than they could have managed some months ago, in the immediate aftermath of their... mistake? Misunderstanding? Mismanagement? Misadventure? Misapprehension?

Stop dictionarying, she tells herself. Despite its being one of her default ways of trying to process confusion, it rarely delivers the clarity she seeks. At any rate, their short-lived whatever-it-was was a mis-everything.

She takes out the book she’s brought with her, H Is for Hawk, so as to fill her head with Heather MacDonald’s solitude rather than her own. She has lately found that overlaying her own thoughts with someone else’s ruminations is quieting, so she’s reading even more than usual... it beats sitting in darkness, waiting. Which she supposes means she should thank Helena (thank her) for her extensive new knowledge: of, here, grief and falconry, but also, the Wright brothers, Joan of Arc, India’s partition, séances in the 1920s, Salem’s witch hunts, various aspects of the Supreme Court...

Erudition must surely outweigh emotionalism Extremity. Enthrallment? Embitterment.

Stop dictionarying.

****

Relentlessly, the holidays approach. Myka tries to ignore them too, particularly their invitation to soften. Unhealthy, Pete’s accusation echoes.

But in speaking to Pete, Myka had lied: she isn’t really ignoring anything Helena-related. In a folder of significant size in her mind, she stores a cascade of spreadsheets in which she tallies and tracks as many of Helena’s movements, statements, interactions as she can, in as much detail as possible: e.g., it wasn’t enough for Myka to get Steve to tell her about his retrievals with Helena—those accounts, while captivating, were incomplete, secondhand—so she has made perverse use of her hard-earned Warehouse database access to read Helena’s actual mission reports, like some pathetic online stalker. They’re literarily significant, she tries to use as additional justification, ignoring the fact that no one other than Warehousers will ever know how or why.

It’s not that she’s hoping to gain insight from any of this; the activity is simply itself. A flat gather of data. For those spreadsheets.

Which she uses, of course, to torture herself, not least for her damning inability to gain insight. Thus proving Pete wrong: it isn’t ignoring things that’s unhealthy. No, it’s paying them attention—stupid, pointless attention—that causes disease.

That’s true, but Myka genuinely does not know how much longer she can suffer making herself sick.

Lovesick, she sometimes thinks... but that makes “love” too prominent in the mix. No, the “sick” is what matters, and it is chronic, not acute. Which means it must be managed rather than cured, and she will manage it, because she has to: because she is an agent and Helena is an agent and they live in the same house and say the same mutually polite “good morning” to each other each day.

Sometimes Myka wisps a wish, in the wake of one of those morningtides whose undertow she cannot reveal, that she could begin to shift her thinking, to try floating above rather than falling under, the better to work her way to commencing the actual ignoring.

But then Helena will talk to Steve about the particulars of his Buddhist practice, or to Claudia about a joint invention project’s feasibility, or to Artie about a disputed wrinkle of history, or even to Pete about, bizarrely yet bizarrely frequently, which menu items should be avoided at fast-food chains... and Myka enters each new datum into the spreadsheets out of avid habit, all while ferally wishing everything different—even, some days, heretically, Helena gone. And while castigating herself for having wished, before, so stupidly inchoately, pleading with the universe to let Helena come back. More: to send Helena back.

How very monkey’s-paw of you, she jeers, to leave out specifics. In particular, to leave out “to me.” Send Helena back to me.

Before Helena came back, Myka was lost; now she’s still lost, but differently. And if there is one thing Myka has never liked—in fact, has always feared—it’s change.

So in truth she can probably suffer making herself sick for quite some time. As long as nothing about the making—or the sickness—changes.

****

The days leading up to Christmas itself are blessedly busy. On the 22nd, Myka and Steve head to West Virginia to bag a problematic coal-miner’s lamp; the work keeps them away until Christmas Eve, and if Myka happens to linger a bit longer at the Warehouse after Steve goes back to the B&B once they’ve deposited the artifact... well, that’s because she’s very conscientious about filing reports in a timely fashion.

In fact, she lingers a lot longer, and she’s happy to arrive home to a mostly silent B&B... however, she is instantly deposited into precisely the sort of situation she’d hoped to avoid: she must walk past Helena, who is in the living room, alone, with the television on. Impossible to slink past undetected, and thus rude to try—particularly once Helena says, “Welcome home.”

How disorienting, for Helena to be here and to say that. Worse, the articulation seems to ring of... before. When Myka was special.

But she is imagining that. She must be.

“What are you watching?” she asks, though she doesn’t need to. Helena is watching the Yule Log.

“A strangely mesmerizing facsimile of a fire,” Helena says, without looking up. “Do I strike you as hypnotized?”

You strike me. Myka’s thought stops there, true as can be. Aloud, she says, “You know what it is, right?”

Now Helena looks up. She blinks at Myka and nods, oddly soft, childlike. “I consulted Google.”

Helena is absurdly fond of Google. Myka struggles to keep from finding this absurdly charming. She struggles similarly with the way in which Helena articulates the word itself—every witnessed occurrence of which is represented in the spreadsheets. so Myka is painfully aware of the way Helena puts a slight formal emphasis on both syllables, such that it sounds, in a capping absurdity, as if she’s saying she consulted Gogol.

Not that acquiring input from a dead Russian writer would necessarily be all that different, absurdity-wise, from having instant access to a towering percentage of the world’s collective knowledge. And Helena probably understands that congruence, if that’s what it is, better than Myka ever could.

Myka knows she’s thinking herself down treacherous paths; she should say goodnight and walk away. But it’s Christmas Eve, and she gives herself a present she shouldn’t want but feels she has earned, earned by ignoring—or, to the contrary, recording—so strenuously. She has done such hard work. So she lets herself ask, “Why are you so focused?”

“Pete gave me a choice: watch the Yule Log or talk to Myka. I believe he thought I would reject the former as unworthy of my attention. Yet here I watch, mesmerized.”

“Since when do you do what Pete tells you?” But thanks, I guess, for letting me know where I stand. She can’t then hold back a jab: “Anyway, shouldn’t you be spending the holiday with the famous Giselle?”

Helena blinks again. This time it’s not at all childlike. “That’s why he wanted me to talk to you. But to answer your previous question: since he told me he’s in love with you.”

He... what? “What?”

“You asked me since when do I do what Pete tells me. I’m answering.”

Keep up, Myka; keep up. “When did he tell you that?”

“This evening. As part of what I fear—or hope?—was intended as a Christmas gift.”

“For you?” That’s not keeping up.

“No.”

“Then for who?” That’s not either.

“Whom.”

“Well, excuse my grammar, but I’m a little weirded out.” This is the most extended conversation she and Helena have had since... before. That’s destabilizing enough to her ability to concentrate on words. but what, exactly, is she supposed to do with these words?

“Weirded out,” Helena says, an unexpected affirmation. “As was I. I wasn’t aware.” She makes a small “huh” noise, as if she has to bridge her way to what’s next. “That the two of you had been involved.”

Oh. Hence the bridge—but this is a shifting surprise. “I thought someone—Claudia—would have told you. Must have told you.” Must have, and that in turn must have contributed, Myka had been sure, to Helena’s lack of engagement. She’s always known your judgment was abysmal, she’d lashed herself, based on those must haves, and this is certainly fuel for that fire.

“Our discussions have been more focused on her future. And my past. And technology, of course.”

“Of course,” Myka says. And then, quick, before she loses her nerve: “It didn’t take.”

“Technology?”

“The involvement.”

“I gathered that from its current status.”

“Right.” The conversation, such as it is, should probably end here... but something is off. “Wait. You said he said he is in love with me.”

“Yes.”

Myka had believed it was over. All over. The idea of having to deal with it, with any aspect of it, in perpetuity, or at least with no clear sundown, preemptively exhausts her. And it rekindles her anger at the entire situation, at its utter pointlessness. “I don’t know what to do with that,” she says. She immediately regrets the admission.

“He said he’ll get over it.”

“Well, that’s something. I guess.” It comes out grudging, and that’s another admission Helena shouldn’t be privy to.

“He said you won’t.”

“What? Get over it? No, the problem was that I wasn’t ever in love. With him.” She’s saying far too much. She supposes it’s fortunate that she’s looking at this repetitively flickery video loop, rather than into Helena’s eyes. She supposes also that said loop is a reasonable metaphor for how her life has been proceeding. Lately. Before, and lately.

“He said that too.”

“I’m sorry, but you’re losing me.”

“Interestingly, he said a version of that as well.”

“That you were losing him?” Not hard to believe; sometimes Pete can barely follow a laser pointer.

Helena focuses her gaze on Myka again, adamantine. “That I was losing you.”

And just like that, Myka is through the looking glass. Trapped like Alice, trying to get out. “Why would you care?” she chokes.

Helena lowers her brow, a stern schoolmarm confronting an intransigent pupil. “Because as I mentioned, he said—and seemed quite certain—that you won’t get over being in love.”

Myka knows now what’s next. Helena is about to say, “With me.” Because once again: that fight.

Oh yes I will. That’s what the ignoring is for. When I work my way around to it, that’s what it’s for.

“I didn’t know,” is what Helena actually says, clearly taking Myka’s silence as affirmation of those unuttered words.

“Oh please. Like I could have been any more obvious.” Obviously. She says it with contempt at herself, past and present: what a pathetic moonstruck puppy.

“At which point?” Helena asks.

That’s a surprisingly troubling question. Timelines. Decisions. What did you know and when did you know it? What did you show and when did you show it?

“All I knew was how you responded. Not how you felt.”

Of course the former was all Myka herself had known, certainly at first, and their consonance surprises her. If only she could share that consonance, and her surprise in it, with Helena... but that seems too much like a reward, one that neither she nor Helena deserves. Again exhaustion: at their lack of merit. “I don’t want to play these games,” she says.

“Then don’t.” Was that a shrug? Did Helena really shrug?

“Fine. I won’t.” It’s childish, yet it feels like the best end she can manage tonight. You didn’t seek this out, she assures herself as she takes a first step away.

Before she can seal the escape with her second step, Helena says, “You might at least release me from this view.”

“You talked to me,” Myka says, doing her best to make it all go away. “You’re free.”

Helena turns from the flames too quickly for Myka to dodge being caught by the look. “I am in no way free.”

That is not my problem, Myka would like to maintain, but Helena’s gaze and tone are implicating, which is entirely unfair but still needs to be dealt with. She sits down next to Helena on the sofa. At a judicious distance.

Now they are both watching the Yule Log, which, indifferent to them both, continues its facsimile flicker. “I guess it is kind of mesmerizing,” Myka says after some time.

“We haven’t spoken much,” Helena rejoins.

“There hasn’t been much to speak about.” Without peril, Myka adds, internally, and by that she means, peril to me.

“On the contrary. But I’ve tried to ignore it.”

“So have I. I hear it’s unhealthy.”

“Perhaps. It’s Pete’s strategy as well, according to him,” Helena says. Then, following a throat-clear, “With regard to his feelings for you.”

Myka doesn’t need to clear her throat. “He’s the one who told me it was unhealthy.” Which puts her in mind of his ostentatious cough: it’s meaningful now. Ridiculous, but meaningful.

“Then I suppose we’re ailing, all of us.”

“I suppose we are. An epidemic of ignorance.”

Helena smiles a little at that. Myka can’t help but smile back, and she maintains it as Helena asks, light, “What is the prognosis?”

“Depends on the ignoring’s end result,” Myka temporizes.

“Pete maintains that ignoring something long enough makes it go away.”

Or it kills you, Myka might say, like cancer. But instead she stays light. As light as she can. “Maybe he’s right. No, probably he’s right.” She owes him that.

Now a pause. A wait. What’s next? “So is that where we leave it?” Helena asks.

Maybe it goes away. Maybe that’s what’s next.

Myka can see it, now: see the spreadsheets dissolving into unnecessarity, see herself not responding physically to Helena, see Helena becoming, in essence, like Pete: someone with a past version of whom a past version of herself made a mistake.

She hadn’t imagined, not before this minute, that it was possible. But now a road leads there.

Can she take that road? She looks again into the fire. The not-fire. It mocks her: Everything you really want turns out to be unreal. On the other side of some facsimilating screen. A mirage. She turns away from it, ashamed. She looks at Helena... for the moment, Helena is still real. Still able to render Myka’s resistance from her body, here in this moment by sitting quietly and watching fake flames, in the next by doing nothing more than breathing out, breathing in.

Myka has not yet taken that awful road. Not yet. One more try, she tells herself. But no, that’s not right. She’s never really tried. Never really. She’s waited—longer than she thought she should—and she’s hoped—harder than she thought she could—but that wasn’t trying.

So: one try.

It can’t be the try she might have made in the past, a desperate just-please-touch-me push. Under the circumstances, that’s impossible. So, what?

An olive branch? No, peace isn’t the right aim, even now.

Better, perhaps: something she wouldn’t have said before tonight’s... encounter. Something related to tonight’s encounter, something more real than she’s offered so far: “We fought. Pete and I.”

TBC

#bering and wells#Warehouse 13#fanfic#Real#holiday (but not Gift Exchange)#sometimes I ideate Myka as just so very tired#of all the things but especially Helena-pressure#and how much more difficult she makes everything#particularly when there seems to be no compensation for withstanding that pressure#but hey Myka#it’s Christmas#so maybe some consolation will be coming your way#if you can wend through the conversational thicket

52 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! B&W gifter here! Any requests for artwork? Feel free to be as specific as you like!

Eee art! I'm so excited already!

Okay, since you said I could be specific: Myka in Victorian drag, ala my fic What Myka Found There. It would be super cool if it was like a family portrait with Helena and Christina too??

If that's not your jam, no worries, I'll think of something else!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

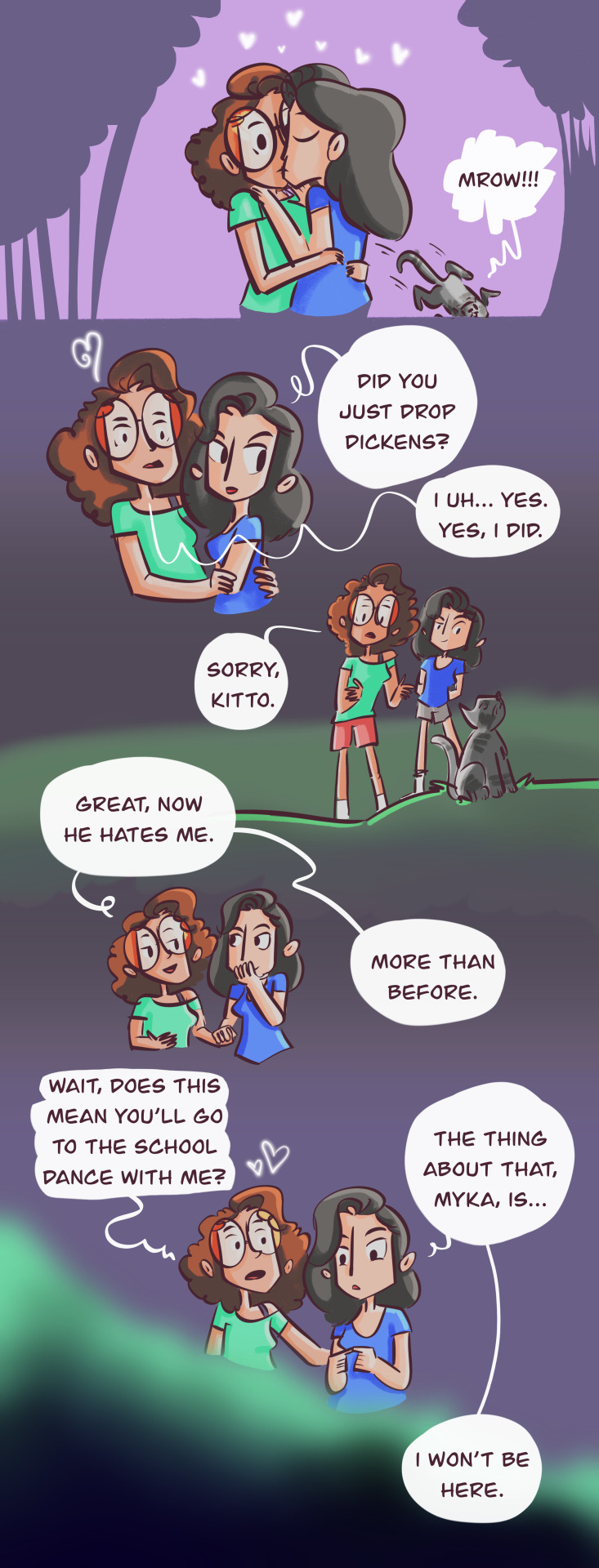

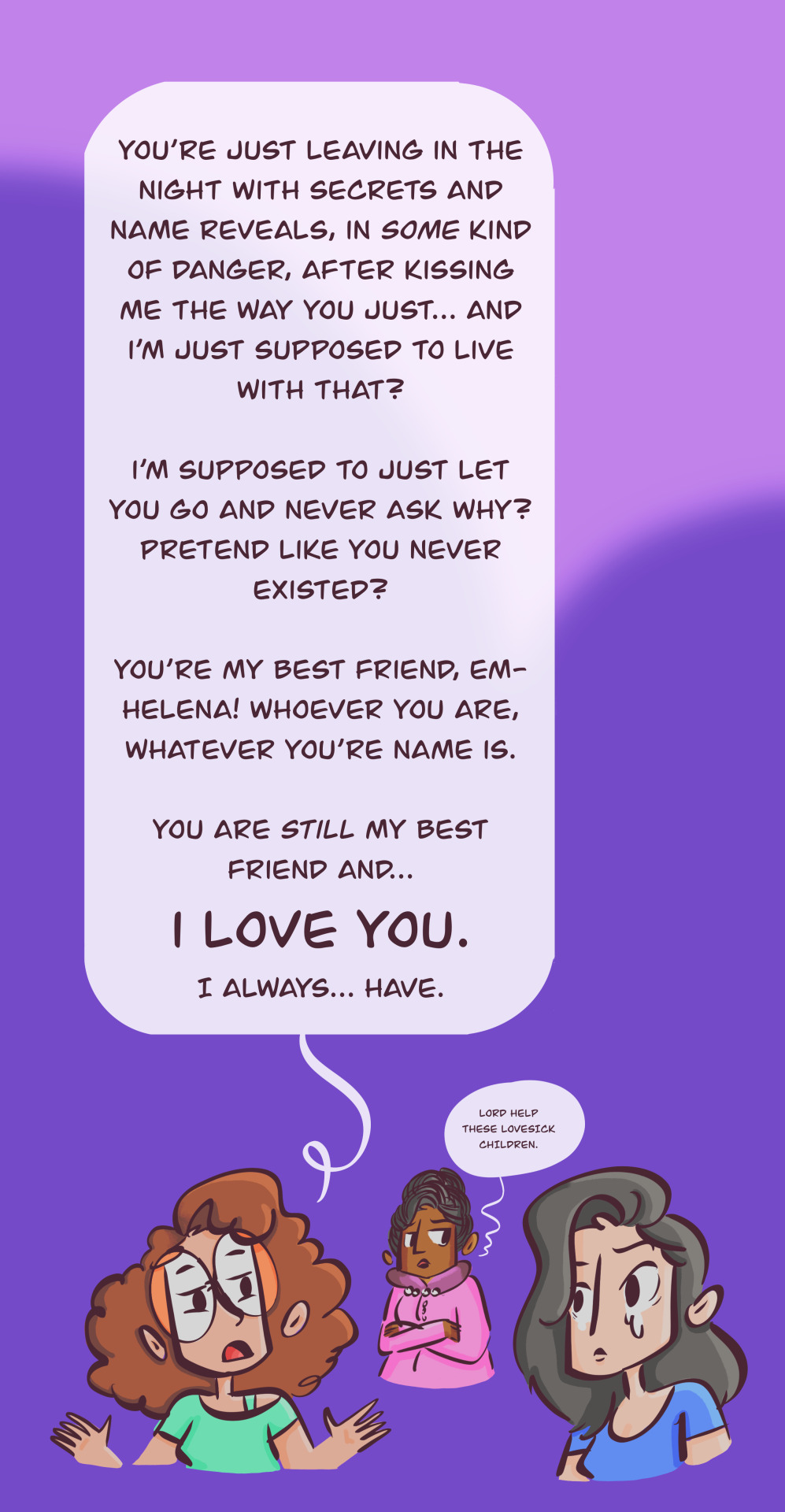

A Bering & Wells Gift Exchange comic story for @lady-adventuress. Happy Palentines Day, friend! There are typos and drawos, even after my very extensive, not-at-all rushed, proof-reading, so, many advance apologies. Thank you for the ideas, I tried to stay in line with mistaken identity/long lost theme. Hope it is enjoyable!

Myka was seventeen when Emily Lake, her best friend, disappeared. Whisked away into the night by Mrs. Frederic, crying and inconsolable, cursing her father’s name. It was unreal, all of it, from first kiss to final goodbye. But whatever disbelief Myka had held onto, wide awake in her bed most of that night, shattered entirely on her walk to school the next morning.

She remembers hearing the sirens as she’d finally drifted into sleep but there were always sirens. Sirens were never unusual.

She should have known. She should have known.

Emily Lake’s house was burned to the ground. A smoldering pile of charred rubble, surrounded by crime scene tape, police vehicles, and a white Coroner's Office van.

She could only get so close but she could see all she needed to see.

She doesn't remember losing consciousness, though she supposes no one does when they come to. She remembers the spinning. She remembers the falling.

And she remembers waking up in the back of an ambulance with Mrs. Frederic by her side.

//

Myka sees Mrs. Frederic a lot over the years. Not by choice or chance. Not by want for that woman to be in her life. Just by the mere fact that she loves a ghost. A girl that's supposed to be dead.

Burned up in a house fire.

Buried in the ground.

They'd pulled two bodies from the rubble of Emily Lake's house, too badly burned for an open casket. Too unknown and unrelated to anyone of means to have a proper burial.

Myka went to Emily's memorial at the high school. She listened as others spoke about a girl they knew nothing about. And while she grew angry at their forced tears and fabricated associations to a dead girl they never knew, she, herself, had absolutely nothing to say about it.

Her best friend, Emily Lake, had died in a fire.

Some girl she loves, called Helena, arose from her ashes.

//

Myka sees Mrs. Frederic once when she's nineteen. This time she hasn't passed out. She's at a cafe on her college campus, listening to music through a set of headphones, and drawing in her sketchbook.

Mrs. Frederic sets a flyer down on the table in front of Myka and takes a seat in the chair across from her.

She doesn't wait for Myka to remove her headphones or even acknowledge her presence.

"This is not cute," the older woman tells her while gesturing down at the paper. "This is too close."

Myka eyes the flyer. It isn't hers per se but she'd been hired by someone on campus to draw it for an upcoming event. It's a very simple drawing of two women holding hands, but one of those women looks a lot like herself and the other looks a lot like someone she used to know.

"You don't like my art?" Myka sighs, turning her attention back to her sketchbook.

"She's dead," Mrs. Frederic recites, not at all for the first time.

Myka puffs out a soft laugh, glances up at Mrs. Frederic, and says, "And yet here you are. Again."

"It isn't safe yet, Myka."

Myka drops her pencil. "When will it be?"

Mrs. Frederic looks away from Myka, over her shoulder, out of a window. She says, without ever turning back, "I told you to forget her. She told you to forget her. You know the consequences of not doing that. You've seen what they're capable of."

"I don't know anything. I certainly don't know the consequences or who they are."

"And believe me when I tell you that you do not want to."

"Is it witness protection?"

"Do I look like I work for the Marshal's office, Ms. Bering? Do our interactions scream Federal Government to you?"

Myka eyes Mrs. Frederic up and down but says nothing at all. In response, she receives a huff of annoyance from the older woman across from her.

"The amount of time I have spent running interference between you and that girl is both baffling and exhausting."

That makes Myka smile. Just a little.

"Finish school, Ms. Bering. Keep your head down. Stop this," Mrs. Frederic taps the paper on the table, "and forget her." She stands and turns then adds, just over her shoulder, "I won't be repeating myself."

Myka sits back in her chair, smiles softly up at the other woman, and says, "Let's do this again sometime, hm?"

Mrs. Frederic rolls her eyes up and sighs. Then turns and walks away.

//

When Myka graduates college at twenty-two, she catches a glimpse of Mrs. Frederic in the hallway of the auditorium where her commencement ceremony is to take place. She is mentally and emotionally preparing herself to fend off all of that woman's criticisms, about what she should and shouldn't be drawing, about how she should and should not be living her life, about who she should and should not be remembering.

But Mrs. Frederic never approaches her. She disappears into the crowd.

Myka has always just assumed that she is being watched, that Mrs. Frederic is watching her. But Mrs. Frederic has never, before now, allowed herself to be seen in return.

//

Myka starts dating a boy named Sam when she is twenty-five years old. Sam doesn't remind her of Helena and it's the thing she likes most about him. It's easy. He's nice. They have fun together.

Myka doesn't see Mrs. Frederic the entire two years they are dating. And somehow, somewhere inside of her, she's a little sad about that.

//

Sam is killed in an accident when Myka is twenty-eight.

They had been broken up for a year at that point but they were still close. Still really good friends with a shared love of art and creating, still collaborating to make what dreams they may have into reality.

A lot of Myka's art shifts back into dark places and in those dark places comes reminders of dark histories. Of grief and sadness. Of love and loss. Of all the pain suffered and endured and, mostly, overcome when the perfect person comes along and holds your hand through it all.

For years, that had been Emily.

Helena.

They'd suffered and endured. They'd held hands through it all. Comforted each other, whenever the other needed it most. Together, they'd imagine themselves on fantastic journeys. The innumerable marks on their skin, souvenirs from their mishaps and adventures.

Myka hasn't cried in so long but she cries the night Sam dies. She cries hard and long, for hours and hours. And when she's all cried out over Sam, she starts crying all over again for Emily Lake.

For the girl named Helena whose last name she doesn't even know. She cries until she falls asleep, then wakes up and does it all over again the next day. She does this for a whole week until the day of Sam's funeral and she doesn't know who she cries for more, Sam, Helena, or herself.

It's been nearly four years since their last encounter but Myka isn't surprised when Mrs. Frederic appears. After the casket is lowered and the crowd dispersed, she steps to Myka's side and stands there just beside her for several moments in silence.

And when Mrs. Frederic has decided she's had enough of the quiet, she says, "You did try. I'll give you that."

Myka doesn't know why but this comment, a simple and useless recognition from the woman who gives almost nothing at all, makes her full belly laugh, crying tears of laughter until she can cry no more.

//

Myka is almost thirty when she almost dies of a heart attack. And then, immediately after that, almost dies by large-toe bludgeoning.

"I'm glad to see you attempting to move on with your life."

"Oh, fuck!" Myka drops a mixing bowl of cooke dough and the very thin, suddenly sharp lip of that bowl lands square on her big toe. When she turns to Mrs. Frederic, in her kitchen somehow, she swears that woman is smiling.

Even if just barely.

"That's a new trick." Myka growls, calming her racing heart.

"New to whom? You seem to be an expert in the field of accidental self-inflicted wounds."

"I mean you. In my kitchen. Inside of my apartment." Myka sighs. "How did you get in here?"

"Certainly not by working at the Marshal's office." Mrs. Frederic quirks a singular brow in Myka's direction.

"Certainly not." Myka mimics, lowering herself to the ground, to clean the cookie dough from tile floor. "What have I done now?"

"I've seen the draft of your very telling graphic memoir. I thought we were clear on the lines that should not be crossed."

Myka stops cleaning. "Speaking of lines that should not be crossed, I won't bother asking how you've seen something that exists solely on my computer." She stands and crosses her arms and tells Mrs. Frederic, "It doesn't mean anything to anyone except me. Nobody else would know it's her and it's not like it's going to bring her back."

"Myka."

Myka laughs softly, "Wow. First name basis? I have definitely crossed a line."

"The problem is, that is exactly what could happen. It could bring her back. Give her no choice but to return."

"She has a choice now? Because that's not what it looked like when you dragged her away."

"I did not drag her. I simply urged her to move forward, faster. You saw, with your own eyes, what the result would have been had she lingered with you. Two homes might have burned that night and your family--"

"I have a lot of respect for you, Mrs. Frederic, despite your constant intrusions. But please, do not talk about my family."

"Fair enough," Mrs. Frederic concedes after a sigh.

"You know, I thought I'd have more hope over time. That she was alive. That she'd one day come back. That I could go to her. Or that holding on to her the way I do would eventually mean something. Anything.

"But after all this time, I find myself more often grieving Emily's death. Because it's the only thing that's real in my mind, it's the only thing that happened.

"Helena is just... she's an old memory that I struggle to keep alive. Ten minutes in one night in the entirety of my life. And I don't even know if anything about those ten minutes is real. If it even means anything. If it's worth holding on to."

Mrs. Frederic watches Myka in thoughtful silence.

"I do know that I never want to forget the way she makes me feel. They way she always made me feel. As Emily, before Helena. She taught me so much. She helped me open up. She opened up to me.

"If I can't talk about her, in a book about my life, there is no book.

"She was my best friend and I loved her. I do what I love because of her and having known her and loved her, for the little time that I was able to, still impacts my life today. Every single day."

Myka gestures to Mrs. Frederic and smiles.

"You, Mrs. Frederic, are living proof of that." She pauses to laugh and adds, "Or the most prolific stalker the world has ever seen."

The older woman remains quiet, pensive. And for a second, one tiny fraction of a second, Myka thinks she's going to show some kind of emotion. Sympathy. Sadness. Contentedness. Amusement? At this point, Myka would even take her usual dose of exhaustion. But Mrs. Frederic's face remains a facade of unconvinced underwhelm and boredom.

Her words, however, belie genuine emotion.

"I have a story for you."

Myka arches a brow. "How suspicious."

"Two little girls grew up together, lived similar lives with similar fathers, who mistreated them in very similar ways. In a single night, they had the nerve to fall in love, right in front of my eyes. A youthful, foolish love that should have ended a decade ago. And yet, here I stand, an intermediary between two foolish girls who refuse to let each other go. Even as they risk their very ends.

"One of those girls is the daughter of a dangerous man who once had the power to demand ungodly things be done to the families of even more dangerous people.

"And the other girl, Ms. Bering, is you."

Myka breathes in slowly. Breathes out one long steady breath.

"I have... so much work to do. And yet, for some reason, I spend, have spent, most of my time intervening in various shenanigans between the two of you."

"Me, living my life like a normal human being, not constantly under threat by some faceless boogie man, is not shenanigans."

Mrs. Frederic ignores Myka's interjection and goes on.

"Intercepting every little whim of the heart you two decide to try and throw out into the world, in order to find each other without blatantly finding each other, when you both know, very well, that is the last thing you should be doing."

"She's... she's trying to find me?"

"Not the point," Mrs. Frederic cuts in. "The point is that she should not be. She knows that. Nor should you be and you know that. Because they could leverage you to get to her to get to her father. They have tried and they will continue to try. And I will continue exhausting myself to keep you two safe because that is what I am, unfortunately, obligated to do.

"No matter how hard you make the task. No matter how many times you want to laugh in the face of it, believe me when I say that he is not worth either of you dying."

Myka remains quiet. She stills. When Mrs. Frederic says no more, Myka takes in another steadying breath and says, "If I didn't know any better, I'd say you actually care about me."

"I care to keep you alive. And her. Until such a time that I no longer have to care about keeping either of you anything for the foreseeable future."

"I do appreciate what you supposedly do, Mrs. Frederic, but in all of our time together, I have never, at any point, felt unsafe or watched by anyone but you."

"And you are welcome for that."

That, to Myka, is the most unnerving thing she has ever heard Mrs. Frederic say to her. In all of their time.

"So what, her dad was some sort of mob boss's hit man?"

"That's a close enough analogy."

"Why didn't you just tell me all of that from the beginning?"

"You were a child. You're no longer a child. I've seen what you've survived. Even if I myself don't find it amusing, I do understand why you laugh when threatened. Now, do you understand the gravity of this ongoing situation?"

Myka nods, "I do."

"I don't believe you."

Myka rolls her eyes. "I understand that I'm supposed to stop doing what I love to do most, drawing and telling stories about my own life, because you want this to end, sooner rather than later."

"No," Mrs. Frederic corrects, "because your life could end, sooner rather than later. You would not have a life to draw or tell stories about."

Myka breathes in deep.

"I am not asking you to give up your passion, Myka, I'm simply reminding you to be mindful, as your passion influences art that grows in popularity, about how much personal information you impress upon it.

"Or one day you'll turn around and it won't be me standing behind you."

//

Myka is thirty-two years old when Mrs. Frederic appears in a bookstore for one of Myka's book signings and, for whatever reason, that woman chooses to stand in line. Myka catches sight of her when she's at least eight people back, and after three more signings, she motions for Mrs. Frederic to come forward.

To Myka's surprise, the woman does.

Nothing about the way she looks has changed, except that she seems a little less baffled, a little less exhausted. Her visits had slowed, once more, as Myka's preoccupation with Helena's absence continued to wane over time.

"I could have waited," the woman tells Myka.

"The looming anticipation of your next threat was too much for me to handle." Myka smiles. "How is our girl?"

The older woman sighs heavily. All of that exhaustion and bafflement returning to her expression. But Myka is surprised, more than that, when Mrs. Frederic answers her genuinely.

"Insistent. Stubborn."

Myka smiles at the thought of Emily/Helena interacting with Mrs. Frederic in these little ways she occasionally interacts with Mrs. Frederic. A thing she used to think about often but doesn't think about so much anymore.

"Thank you," Myka says softly, lowering her head to face the table below and wiping away a stray tear. When she looks back up to Mrs. Frederic, she adds, "I appreciate knowing she hasn't changed one bit."

Mrs. Frederic reaches into her purse and pulls out a copy of Myka's book. She sets it on the table in front of Myka, who smiles wide.

"You bought my book."

"A birthday gift," Mrs. Frederic says, "for our very insistent friend."

//

Myka is thirty-four when Mrs. Frederic unexpectedly sits beside her on a park bench then holds an envelope out in front of her. And for the first time, in a long time, Myka isn't startled. She almost expects that other woman's arrival.

She says to the older woman, without ever looking at her, "I don't know what they're paying you but I'm sure it's not enough."

Myka doesn't immediately take that envelope but she can see that her name is on the front. She can see that the handwriting is Emily's. Recognizable in comparison to all of the old notes she has stashed away from high school.

Still, she straightens in her seat and asks, "We're on writing terms now?"

"Proof of life."

"Seventeen years ago, you told me she died." Myka cautiously takes the envelope. "You told me to forget about her."

"And nearly two decades later, look where that has gotten us."

"You've suggested on several occasions that I'd be murdered."

"I resisted the urge myself on many of those occasions."

"A joke?"

Mrs. Frederic arches a brow. The playfulness of that expression, Myka finds, is unnerving at best.

"You said they are dangerous people."

"They were."

"They were?"

"We're on the cusp of a resolution."

"A resolution? With very dangerous people? More dangerous than the man who committed heinous crimes against them?"

Mrs. Frederic nods and simply says, "Even dangerous people grow old."

"Then I guess I feel comforted that you haven't aged a day since we met."

Myka can see Mrs. Frederic suppressing a smile.

"You know, in all these years that I've come to know you, Mrs. Frederic, you don't strike me as the type to negotiate with, much less protect, a man who has done ungodly things to anyone. Dangerous people included."

"You refer to her father as a man, which is something I haven't done in over three decades." A pause follows a thoughtful sigh as Mrs. Frederic turns away from Myka and says. "Still, I find even calling him the monster that he is to be too generous."

Myka gives a subtle, understanding nod.

"The thing you may or may not have come to understand, without the proper context, is that some very terrible people are more valuable to when they are alive, worthless when they are dead, when the survival of many more good people depends on what they know. My employers find value in his living, so he remains alive and, by default, protected."

"And Helena? Where does she come into all of this talk of value and worth?"

"She is her father's collateral damage." Mrs. Frederic turns to Myka. "From the moment she was born, he has been using her existence to further his malintent. Without her, he would already be dead."

Myka can feel her blood rising.

"He had money. He had custody. He had power. He doesn't have any of those things now and I promise you, Myka Bering, that he is not worth the energy you will burn being angry at him."

Myka doesn't quite let the anger go. But she breathes a little steadier now.

//

Weeks later, Myka finds a Post-It note on her refrigerator door that she didn't place there and doesn't recall seeing the night before.

It reads: Answer the call. - F

Within the hour, Myka's cell phone rings. No name or number appears on the screen. And when she answers, it's with a tease. She says, "It only took you twenty years to realize you could threaten me over the phone instead of constantly sneaking up on me in public?"

"I told Irene," a soft, distantly familiar voice starts, "you'd tire of her appearing act sooner than most."

The voice hits her hard. Harder than the combined weight of every moment in her past that she has felt sorrow or grief or loneliness beyond measure. She has to steady her hands to not drop the phone. She has to steady her breathing to not fall to the floor.

"Helena?"

Soft breathing turns to soft laughter which turns to soft crying, on both ends of that line.

"Is that really you?"

"It really is."

Myka sits before she falls, carefully lowering herself to the kitchen floor. Clutching that phone in her hands. Her back to the cabinet doors. Her legs folded up before her.

She decides to start off small and easy.

"Hi."

And is rewarded beyond measure.

"Hello again, my love."

#bering and wells#b&w holiday gift exchange#lady-adventuress#dickens draws#sorry this is so late#i usually draw and post and then write when i post#and this writing took on a mind of its own#i wasn't even done i just cut myself off lol

64 notes

·

View notes

Link

Chapters: 1/1 Fandom: Warehouse 13 Rating: General Audiences Warnings: No Archive Warnings Apply Relationships: Myka Bering/Helena "H. G." Wells Characters: Myka Bering, Helena "H. G." Wells Additional Tags: Fluff, Established Relationship, Bering and Wells Holiday Gift Exchange 2024 Summary:

Myka can't wait for winter to be over. On the first day it feels like spring has finally arrived, her and Helena have a picnic.

This was written for @purlturtle as part of the 2024 Bering and Wells Holiday Gift Exchange, who gave me the following prompt:

"how about something spring-themed (since the gifts will be exchanged for Valentine's, IIRC)? Like, being at the tail end of winter and longing for spring, or experiencing the first day when it really feels like spring is in the air, that kind of thing?

Alternately, maybe something to do with chocolate? (I love chocolate)"

I had a lot of fun with the prompt (started writing it pretty much as soon as I got it) and I tried to include everything. Hopefully you enjoy it :)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy B&W Gift Exchange @madronash!

(Virtual) Reality: Helena gives a virtual reality headset from FarGames a try, and Myka watches fondly. Set post-series, in a better version of the series where the silly bullshit didn't happen.

https://archiveofourown.org/works/45041281

@madronash

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

and i could be enough / and that would be enough

My contribution to the @b-and-w-holiday-gift-exchange — Bering & Wells + That Would Be Enough for @galactic-pirates.

This is lyrically perfect or them thank you so much for the inspiration, I hope you like it.

#bering and wells#myka x hg#gifs#warehouse 13#wh13edit#beringandwellsexchange#myka bering#helena wells

783 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello it's your gift exchange gifter! Let's say your story has hypothetically expanded to cover four or five short chapters. Would you like your story all at once, or in installments?

well firstly you’re amazing thank you!!! i think id like them in installments please! to stretch out the wondrousness of the exchange :D

thanks again and cant wait for tomorrow!

1 note

·

View note

Text

of purple goo and other surprises

My @b-and-w-holiday-gift-exchange fic for @deathtodickens, I hope you'll like it!

3.6k T, no warnings, canon-divergence

setting: Helena is a Warehouse agent along with Myka. They are close friends, but Myka wishes for more... Can an overnight stay during a retrieval mission reveal her feelings?

Beta read by @wellsbering, thanks for the help <3

#please reblog :)#lilo writes#lilo writes fanfic#bering and wells#bering and wells gift exchange#warehouse 13#Bering and Wells fanfic#my w13#gift fic#prompt fic#only one bed#getting together#wlw#b&wexchange22#deathtodickens#b and w holiday gift exchange#mine#feb'23#14.02.23#ao3 link#my post

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A @b-and-w-holiday-gift-exchange gift for @sharkbatez . Happy Bering and Wells Day!

#warehouse 13#helena wells#myka bering#bering and wells#b-and-w-holiday-gift-exchange#sharkbatez#bering and wells exchange

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Giftee Names Are Out!

Please let me know if you did not receive a DM with your giftee's name, or if you are unable to reach your giftee anonymously.

Also, please check your settings and make sure your askbox is accepting anonymous messages! Or, if you don't want to turn on that setting, please reach out and let me know.

You have from now until January 1st to discuss prompts with your giftee! Have fun!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bonus 4

First, a PSA: If you are eligible to vote in next week’s US election, please VOTE FOR HARRIS as well as every other Democratic candidate on the ballot, and do what you can to persuade as many other people as you can to do the same. I assume anyone who bothers to read my writing is smart enough to understand why that’s necessary—and why engaging in any sort of protest-vote or sit-this-one-out charade is counter to the interests of most living breathing people at this point in history.

Anyway. Here I offer the final part of last year’s Christmas story... again and as usual, where were we? I recommend the intro to part 1 for where we are, canon-wise (S4, essentially, but diverging); beyond that, Myka has just returned to the Warehouse after a holiday retrieval in Cleveland (Pete, in town visiting his family, was tangentially involved), where Helena, whom Myka hadn’t seen since the Warehouse didn’t explode, served as her backup—a situation facilitated by Claudia as something of a Christmas bonus. Post-retrieval, Helena and Myka shared a meal at a restaurant; this was a new experience that went quite well until, alas, Helena was instructed (by powers higher than Claudia) to leave. Thus Myka returned home, both buoyed and bereft... and here the tale resumes. I mentioned part 1, but for the full scraping of Myka’s soul, see part 2 and part 3 as well.

Bonus 4

Late on Christmas Day, Myka is heading to the kitchen for a warm and, preferably, spiked beverage, intending to curl up with that and a book—well, maybe a book; a restless scanning of her shelves had left her drained and decisionless, hence the need for a resetting, and settling, beverage—and to convince herself to appreciate the peace of these waning Christmas hours. She peeks into the living room, just to assess the wider situation, and regards a sofa-draped Pete. He returned from Ohio barely an hour ago, which Myka knows because she had heard Claudia exclaim over his arrival. Then things had gone quiet.

Now, he appears to be napping.

Myka tries to slink away.

“Claud mentioned about your backup,” he says as soon as her back is turned, startling her and proving she’s a terrible slinker. Small favors, though: at least she hadn’t already had her beverage in hand and so isn’t wearing it now. “That had to be weird,” he goes on, sitting up.

She’s been wondering whether the topic would come up, whenever they happened to get beyond how-was-your-trip pleasantries... she entertains herself for a moment with the idea of referring to Helena, specifically with Pete, as “the topic.” So she tries it: “‘Weird’ does not begin to describe the topic.” It is entertaining, as a little secret-layers-of-meaning sneak. But there’s yet more entertainment in the offing, with its own secret layers: “Incidentally, speaking of weird—which I’m sure was also mentioned—I met your cousin. Thanks for giving her an artifact. Very Christmas of you.”

He rounds his spine into the sofa like he’s trying to back his way through the upholstery and escape. “Don’t be mad. I didn’t mean to. I didn’t know it was an artifact.”

Myka is tempted to keep him guessing about her feelings, but she doesn’t really have the energy; she gives up on entertainment and tells the truth: “I’m not mad. I’m serious: thank you.”

“I think you’re trying to trick me,” he skeptics. “Soften me up for something. But if that’s for real, then you should thank my mom more than me.”

Pete’s mother. The extent of Jane Lattimer’s role in Myka’s life is... surprising. Then again the extent of her role in Pete’s life has turned out to be surprising too, and that’s probably a bigger deal, all things considered.

Pete goes on, “Because I was gonna blame her, but should I give her props instead? It was her idea to give the little feather guy to Nancy, because of how after I got it I saw that it’d probably PTSD you.”

“I appreciate the seeing, but... wait. After you got it. How’d you get it in the first place?”

“I was in this antique store,” Pete says.

As if that explains everything—when in fact it explains nothing. In further fact, it unexplains. “Why were you in an antique store? According to you, you hated those even before the Warehouse turned them into artifact arcades.”

“Mom was picking something up there, and this guy showed it to me.”

“Your mom, this guy...” Myka is now beyond suspicious. “What did this guy look like?” A pointless question. As if knowing that could help her... as if anything could really help her. This is madness. “Fine. It doesn’t matter what he looked like, because I’m stopping here. I can’t keep doing this. For my sanity, I can’t.”

“Keep doing what?”

“Tracing it back. You win. You all win.”

“Do we? Doesn’t feel like it. And that doesn’t seem like a reason you’d be thanking me.”

“No. That isn’t. But as of now I’m trying to keep myself from focusing on... let’s call it the causal chain.”

“I’d rather focus on the popcorn chain.” He points to the strands that loop the Christmas tree.

They are the tree’s only adornment. Every prior holiday season of Myka’s Warehouse association, Leena has decorated the B&B unto a traditional-Christmas Platonic ideal; this year, in her absence, Myka, Steve, and Claudia, trying to replicate that, had purchased a tree. And transported it home. And situated it near to plumb in the tree stand, which was an exhausting exercise in what they earnestly assured each other was complicated physics but was really just physical incompetence.

They had then settled in to do the actual decorating, starting with popcorn strings... but once they’d finished those, they were indeed finished, pathetically drained of holiday effort. And they’d succeeded in that initial (and sadly final) project only because, as they’d all agreed once they’d strung the popcorn, Pete hadn’t been there to shovel the bulk of their also-pathetic popping efforts into his mouth.

“Take them down, slurp them up like spaghetti if you want,” Myka says now. “Christmas is pretty much over.” The statement—its truth—makes her stew. At Pete? But the situation isn’t ultimately his fault, no matter what part he played. And why is she so set on assigning, or marinating in, this vague blame anyway? She got something she wanted: time with Helena. It didn’t work out as perfectly as she’d wished it would, but she got it.

She tries to resettle: her heart to remembrance, her brain to appreciation.

The doorbell rings, its old-fashioned rounded bing-bong resounding from foyer to living room and beyond, bouncing heavily against every surface. Myka lets the vibrations push her toward the kitchen; she’s had enough of interaction for now. Her beverage and book, whichever one will provide some right refuge, await. As do remembrance and appreciation.

She hears Pete sigh and the sofa creak; he must have shoved himself from it in order to lurch to the foyer. A minute later, he yells, “Guess what! Christmas might not be over!”

Still kitchen-focused, Myka yells back, “If that’s not Santa himself, you’re wrong!”

“Never heard of that being one of her things!” Pete shouts, even louder.

“Quit shouting!” Myka bellows, so loud that she drowns out her own initial registering of what he’s said, which then starts to resonate in her head, a stimulating hum that resolves into meaning... her things? Her things... Myka’s torso initiates a turn; her body knows what’s happening, even if her brain—

“Hey, H.G.,” Pete says, and now every part of Myka knows.

Except her eyes, but once she moves to the foyer to stand behind Pete, they know too: There Helena is. Her body. Embodied. The illumination of her, in the foyer semi-dark... her bright eyes catching Myka’s, warming to the catch... oh, this.

Seeing the sight—greeting, once again, her perfect match—she is struck dumb.

There’s movement behind her, though, and she turns to see Steve and Claudia poking their heads into the space like meerkats—well, no, in South Dakota she should think prairie dogs... but they’re both built more like meerkats than prairie dogs, so she should probably keep thinking meerkats out of... respect? Whatever: they’re animal-alert, heads aswivel, faces alight. It surely signifies something.

Turning back to Helena, trying to get a voice in her mouth, she coughs out, “You’re back? Now? I mean, already? How did you—”

“To quote myself: ‘when I can, I will,’” Helena says, as matter-of-factly as anyone could possibly speak while maintaining intense eye contact with one person, and Myka thanks all gods and firefighters above that she is herself that person. “Now, not forty-eight hours later, I could. Thus I did. I should note that I’m unsure as to why I could, but perhaps it’s a gift horse?” Her focus on Myka does not waver. Pete and the meerkats might as well not exist, and Myka in turn is mesmerized.

“Maybe that’s the horse you rode in on,” Claudia says. Is she trying to break the spell? Myka wishes she wouldn’t... she ideates shushing her, even as Claudia goes on, “But better late than never, Christmas-wise, right?”

“Did you enjoy your additional portion of squash?” Helena asks Myka, ignoring Claudia’s interjection. Her tone is formal, presenting public, but her question is for Myka alone.

“It was very good for my heart,” Myka says. She doesn’t add, though she could, And so was that question.

Helena smiles like she heard both good-fors—like she’s grateful for both—and Myka thinks, for the first time out loud in her head, She feels the same way I do.

It’s... new. Different. Perfect? Not yet, the out-loud-in-her-head voice instructs.

But she can make a move in that direction. “Please put your suitcase in my room,” she says. Out loud, outside her head. Realing it.

“I will,” Helena says. She takes up her case and moves toward the stairs, presumably to real that too.

It renders Myka once again enraptured. She is taking her suitcase to my room. My room. She is.

The first stair-creaks that Helena’s ascent occasions sound, to Myka’s eagerly interpretive ears, approving.

Claudia and Steve don’t even blink. Pete does—well, more the opposite; he widens his eyes in the cartoony way.

But then he turns on his heel, Marine-brusque and not at all cartoony, and exits the space. Myka doesn’t know what to make of that. She’ll most likely have to address the topic—in fact, “the topic”—with him later. Fortunately, later isn’t now.

She does know, however, what to make of Steve and Claudia’s aspect: “I’m sensing some ‘aren’t we clever’ preening,” she accuses.

“We are clever,” Claudia says, dusting off her shoulder. “More Fred. Don’t sweat it.”

Exasperating. “Don’t sweat it? As I understood the situation, Fred was a retrieval and an insanely expensive dinner. Are we doing that again, or is she back for good?”

“She’s back for nice,” Claudia says.

Steve jumps in with, “To answer your question: we’re not a hundred percent sure.”

“See, we made a deal,” Claudia says.

“With whom?” Myka asks.

“Santa?” Claudia says, but without commitment. Myka’s response of an oh-come-on face causes her to huff, “Fine. Pete’s mom and company. And Mrs. F. And even Artie, in absentia.”

“What kind of deal?” Myka asks, because while she can’t dispute the indisputably positive fact that Helena is here, she mistrusts any deal involving Regents. Pete’s mom aside. Or Pete’s mom included: She can’t stop her brain from stirring, stirring once again to life those causal-chain questions: What’s being put in motion this time?

“A kind of deal about which things they’re willing to let us—well, technically Steve—say are nice,” Claudia pronounces, as if that explains everything.

Myka is very tired of proffered explanations that actually unexplain.

Steve says, “Claudia finally found the file on the pen. Seems that Santa’s list, once made, is kind of ridiculously powerful. And it turns out you can put a situation on the list.”

“For example,” Claudia supplies, “H.G. and you. Getting to be in each other’s... proximity.”

Steve adds, “And yours isn’t the only one I put there. That was part of the deal.”

“So you’re letting the pen reward nice situations with... existing,” Myka says. “And are you storing it on some new ‘Don’t Neutralize’ shelf? So nobody accidentally bags the existence out of them?”

Claudia says, “Kinda. At least for a while.”

This all seems deceptively, not to mention dangerously, easy. “But: personal gain, not for,” Myka points out.

“Right,” Steve says. “So here’s a question: what does ‘personal gain’ actually mean? The manual doesn’t have a glossary. So we’re trying to work it out. Let’s say Claud uses an artifact and then makes this utterance: ‘My use of this artifact was not for personal gain.’ And let’s say I assess that utterance as not a lie. The question remains, are the Warehouse and Claud and I agreeing on the definition of ‘personal gain’?”

“The question remains,” Myka echoes, fretting. “And the answer?”

“We’ll see,” Steve says.

It’s destabilizing, but that’s the Warehouse’s fault, not Steve’s. “I just hope the artifact won’t downside you for any disagreement. Because you’re remarkably nonjudgmental, and—”

“With a Liam exception,” Steve notes. “Or several. Ideally, though, the Warehouse and I can work through these things like adults. Unlike me and Liam.”

Myka respects his honesty. And yet: “I’m having a seriously hard time ideating the Warehouse as an adult.”

“We’re working through that too,” Steve concedes.

“You clearly have the patience of a saint.”

Steve chuckles. “Pete’s your partner, right? And in another sense, H.G. might be too?” Myka waves her hands, no-no-too-soon, because suitcases notwithstanding, she has certainly in the past thought she was making a safe all-in bet, only to lose every last copper-coated-zinc penny of her metaphorical money. “No matter what we call anybody,” he continues, “I think you get a lot more patience practice than I do. I’m just dealing with one little Warehouse and its feelings.”

“Aren’t its feelings... unassimilable?” she asks. “Or at least, shouldn’t they be?” It’s a building. Whatever its feelings, they should be talking about it like it’s an alien, not somebody who’s in therapy. Or somebody who should be in therapy.

“Maybe,” Steve says. “Or maybe not. That was part of the deal too, that I would test out how it feels. About personal gain specifically here, eventually maybe more. But if it has a meltdown...”

“Ah. We cancel the test, neutralize the pen, and face the consequences.”

Steve nods. “But ideally, if that happens, we will have leapfrogged whatever the looming Artie-and-Leena crises are. The two of them coming back here safely are the other situations we niced, as part of the deal.”

Claudia adds, “My big fingers-crossed leapfrog is over their stupid administrative ‘keep H.G. away from Myka and everybody else who loves her’ dealy-thingy. We’re hoping they’ll just forget about whatever their dumbass reasons for that were when they see how great it is for her to be back.”

“Dealy-thingy? Have you been talking to Pete?” Myka asks, trying for silly, for light—so as to deflect that “love her” arrow.

“Not about that. But wait, are you saying he loves her too? I mean I figured he was okay with her after the whole Mom-still-alive thing, but his Houdini out of here just now makes me think he’s not quite all the way to—”

“Never mind,” Myka says, as a command.

Claudia squints like she wants to pursue it. Myka crosses her arms against any such idea, in response to which Claudia says, “Fine. Here’s some funsies you’ll like better. Making that list, you’ve gotta have balance. Naughty against the nice.”

“And you think I’ll like that because?”

“I talked to Pete’s cousin, a little pretty-sure-we-don’t-have-to-tesla-you-but-let’s-make-super-sure exit interview. Heard some things about a guy. Bob? Seemed like a good candidate.”

Well. Pete had been right on several levels about Christmas not being over yet. “That’s the best news I’ve had in the past... I don’t know. Five minutes?” Other than the Pete-vs.-“the topic” question, it’s been an absurdly good-news-y several minutes.

Claudia goes on, “Personal gain, what is it? There’s also a warden from that place I don’t like to remember being committed to who’s about to have a Boxing Day that’ll haunt him longer than he’s been haunting me.”

That definitely raises questions—flags, even—about “personal gain” in a definitional sense, but letting all that lie seems the better part of valor, so Myka asks Steve, “Any Liam on there?”

“Too personal to let the Warehouse anywhere near,” he says, but with a smile.

Myka smiles too. “Would that I could say the same about my situation.”

Claudia snickers. “Your situation is Warehouse-dependent. Warehouse-designed. Warehouse-destined.”

“All the more reason said Warehouse shouldn’t object to easing the pressure,” Steve says.

“Are you kidding?” Claudia says. “Its birth certificate reads ‘Ware Stress-Test House.’”

Myka appreciates their positions—Steve’s in particular, even as she internally allows that Claudia’s is probably more accurate—but she would appreciate even more their ceasing to talk about her situation like they’re the ones whose philosophy will determine how, and whether, it succeeds. Or even proceeds.

And she would most appreciate their ceasing to talk about her situation entirely. So that she can go upstairs and be in her situation, because Helena hasn’t come back downstairs, a fact for which Myka’s rapidly overheating libido has provided a similarly overheated reason: she is waiting, up there in the bedroom, for Myka.

Which thought is of course followed by Helena’s preemption of same: she descends the stairs and presents herself in the foyer.

Damn it, Myka’s disappointed libido fumes.

Sacrilege! an overriding executive self chastises, and it isn’t wrong, for again, here Helena is. To fail to appreciate that—ever—is an error of, indeed, biblical, or anti-biblical, proportions.

In any case, now four people are just standing here, awkwardness personified.

Helena flicks her eyes briefly toward Myka—it seems a little offer of “hold on”—then turns to Steve and Claudia. “I didn’t greet either of you directly when I arrived. I apologize. Claudia darling, it warms my heart to see you... and this is of course the famous Steve, whose acquaintance I’m delighted to make at last.”

Striking to witness: Helena has essentially absorbed the awkward into her very body and transmogrified it into formality.

Myka loves her.

“Famous?” Steve echoes, like she’s said “Martian.”

“I’ve heard much of you,” Helena says, with an emphasizing finger-point on “much.”

Steve smiles his I’m-astonished-you’re-not-lying smile, through which he articulates, “Likewise? I mean, likewise, but with more. Obviously.”

Yes, Myka loves her: for her charming self alone, but also for how that charm extends; her sweet attention to Steve has him immediately smitten. Myka’s the one to catch Helena’s gaze now, intending merely to convey gratitude, but to her gratification it stops Helena, causing her to abandon her engagement with Steve.

Maybe she and Myka can stand here and gaze at each other forever. It wouldn’t be everything, but it would be something. Second on second, it is something. It is something.

Claudia interrupts it all, saying to Helena, “Can I hug you?”

Myka doesn’t begrudge the breaking of this spell, particularly not with that; she had been selfish, before, greedy to keep Helena and her eyes all to herself. She also doesn’t begrudge the ease of the hug in which Claudia and Helena engage; getting a hug right is simpler when its purpose is clear. And clearly joyful.

Over Claudia’s shoulder, Myka’s and Helena’s gazes lock yet again, and it’s spectacular.

However: it also seems to introduce a foreign element into the hug, some friction that Claudia must sense, for she disengages and says, “So. I have to go. I just remembered I have an appointment to not be here.”

Steve says, “I feel like I was supposed to remember to meet you there, wasn’t I,” Steve says, and Myka has never been able to predict when he’ll be able to play along instead of blurting “lie” (even if he does often follow such blurts with some version of an apologetic “but I see the social purpose”).

“I don’t think you were,” Claudia says, “because I’m revising the gag; it makes more sense if I just now made an appointment to not be here. So you couldn’t be remembering some nonexistent-before-now appointment.”

“But I still think the appointment ought to be with me, gag-wise and otherwise,” Steve says, doggedly, still playing. “In the first and second place.”

“Is this the first place?” Claudia muses, faux-serious, now rewarding his doggedness. “Is the appointment in the second place?”

They could who’s-in-the-first-place this for days, so Myka intervenes, “In the first place, if this is a gag, it desperately needs workshopping. But in the second place: Scram!”

“You mean to the second place,” Claudia sasses.

Myka scowls, wishing she could growl proficiently.

Claudia’s eyes widen. “Scramming. Best scrammer,” she says, sans sass, proving the actual growl unnecessary. Interesting.

“Except that’s about to be me with the gold-medal scram,” Steve objects and concurs.

Myka pronounces, “I’ll be the judge of who’s what. Once you actually do it.”

“You’ll award the medals later though, right?” asks Claudia. Her words are jokey, yet her tone is weirdly sincere, as if Myka might forget they had scrammed on her behalf, and that such amnesia would be hurtful.