#Battery M 1st US Artillery

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I spent today writing up mini-bios of my great-grandparents for a genealogy project I'm working on. I want to make all the research I've done accessible to everyone in the family, and I want to include a real sense of who our various ancestors were as people, for those who didn't have the opportunity to know them. Here are a couple examples:

Gilbert James McKeehan - Early Life

Gilbert James McKeehan was born 15 September 1903 in Walla Walla, Washington, the only child of Elijah Brewer McKeehan and Nora Belle Crumley. Gilbert’s father had been previously married, and Gilbert had several older half-siblings, but he was his mother’s only child. Nora doted on Gilbert. When he showed an aptitude for music, she bought him a piano and lessons with money she earned cleaning houses.

In June 1921, when he was 17 years old, Gilbert enlisted in the Army National Guard, where he served as a Private and clerk in the Battery A Corp Artillery. He was promoted to Private 1st Class in January 1923. In 1921-1922, historic Fort Walla Walla was converted into a hospital for military veterans (now the Jonathan M. Wainwright Memorial VA Medical Center). Soon after it opened, Gilbert began working as a messenger for the hospital. In May 1924, he was transferred to Company F 161st Infantry. He was discharged in June of that year, but continued to work for the veterans hospital until at least 1942.

At 5 feet 10 inches, with brown wavy hair and hazel eyes, Gilbert was handsome, charming, and a talented musician, able to play the piano by ear. He had a playful sense of humor and a reputation as a ladies’ man. During the 1920s and early 1930s, Gilbert played piano and sang for the Chesterfields, a band named for a popular brand of cigarettes at that time. The band’s motto was “we satisfy!” Other members of the Chesterfields included Earl Schoenberger on horn, Ralph Augustavo on trumpet, Ted Cleaver on guitar, and Pearly Mo on drums. Gilbert served as the band’s manager, and arranged all the music. In 1930, the Chesterfields recorded an album, which included a cover version of Émile Waldteufel’s “The Skater’s Waltz”. Gilbert occasionally played with other local bands as well, such as Bob Meyers’ Whitmaniacs. The bands played all over, including at the Metronome in Walla Walla, Edgewater Park in Wallula, and occasionally in Prescott.

Rowena Helen Armstrong - Early Life

Rowena Helen Armstrong was born 18 January 1903 in Prescott, Washington, the eighth of ten children of Leo Cornelius Armstrong and Mary Catherine “Molly” Martin. She was baptized at the Catholic Church of Saint Patrick in Walla Walla on 26 April 1903. By the time she came along, Rowena’s oldest siblings were already grown, and beginning to start families of their own. Before she turned fourteen, three of her siblings had died. In consequence of this, Rowena grew up very close with her sister Bonnie, who was just twenty months younger than Rowena.

Rowena grew up on her family’s farm on the edge of Prescott. Her mother called Rowena her “angel”, but that didn’t mean Rowena never got up to mischief. She was a lively girl, with an infectious giggle, and a love of fun. Sometimes she would jump off the roof of the barn, using her father’s big umbrella as a parachute to “float” down. She and her friends would tease a young teacher named Mr. Flower to make him blush, calling him “Herr Blossom”. “Once I buried a kid under the snow, right over her head,” she confided to her grandchildren. “But she could still breathe. We fixed it so she could. And when we went back into class after recess the teacher wondered where she was. I buried her at recess – she begged me to!”

When Rowena was eleven, she and her sister Bonnie were playing in the hay barn, where they were forbidden to go, because it was dangerous. They climbed up the pile of hay, halfway to the roof of the barn, and jumped up and down on it, until Bonnie slipped, and fell into the pile. She almost suffocated, but Rowena pulled her out in time. They swore to each other that they would never tell anyone what had happened, for fear of getting into trouble – and they never did, until Rowena told her grandchildren about it decades later.

In the winter, Rowena and her friends went sledding on Skyrocket Hill, Starbuck Hill, Meadowlarks, and at Whetstone Creek. In the summer, they played in the Touchet River, which was dangerous because Rowena did not know how to swim. Sometimes, for special celebrations, they traveled north, taking a ferry across the Snake River to picnic at scenic Palouse Falls.

Rowena was an excellent student. In the eighth grade, she served as her class president, and represented Prescott School in a regional spelling championship. In high school, she took classes in Advanced Home Economics. However, this did nothing to curb her wild side. A teacher at Prescott remembered the school putting on a carnival, and 17-year-old Rowena performed a flamenco dance in full skirts, on a tabletop, with a rose between her teeth.

The summer she was 18, Rowena hitched a ride on the mail truck to visit her eldest sister Maude in Dayton. On the way there, the mail truck was involved in a head-on collision, and Rowena went through the windshield, cutting her face and neck on the glass. When her mother saw her, she threw the oil can she was carrying over her head, cried out, “Oh my God!”, and fainted dead away. Molly couldn’t bear the sight of blood. Maude just said, “The best looking one of the bunch, and she has to get her face cut up.” Fortunately, there was no permanent scarring.

Next on the list: a section about Gilbert and Rowena's (brief) marriage, then separate sections for their later lives and subsequent marriages, and a mini bio of their only child, my grandmother, whose fault it is that I'm doing any of this in the first place!

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

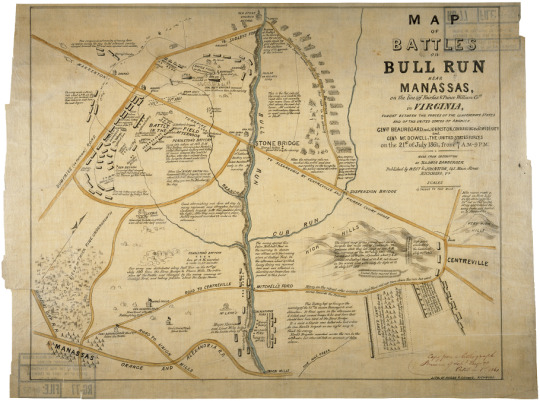

Map of the Battles of Bull Run, 7/21/1861

File Unit: Virginia and the Chesapeake Bay, 1784 - 1890

Series: Civil Works Map File, 1818 - 1947

Record Group 77: Records of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, 1789 - 1999

Image description: Map of the area of Bull Run, showing roads, terrain, troops, structures. There are many notes describing different areas.

Image description: Zoomed-in portion of the map showing the “Battle Field in the Afternoon” area.

Transcription:

MAP

OF

BATTLES

ON

BULL RUN

NEAR

MANASSAS,

on the line of Fairfax & Prince William Coes.

in VIRGINIA,

FOUGHT BETWEEN THE FORCES OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES

AND OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.

GENLS BEAUREGARD and JOHNSTON, COMMANDING the CONFEDERATE

and

GENL. McDOWELL, THE UNITED STATES FORCES

on the 21st of July 1861, from 7 A.M. - 9 P.M.

MADE FROM OBSERVATION

BY SOLOMON BAMBERGER.

Published by WEST & JOHNSTON, 145 Main Street

RICHMOND, Va.

SCALES

4 INCHES TO THE MILE

Two companies of cavalry of enemy here

as reserve during the day. In the afternoon cavalry

charged towards Geo. 7th and were repulsed with canister.

Enemy's Cavalry

WARRENTON TURNPIKE

SUDLEYS FORD

OLD STONE CHURCH METHOD. No guard at Sudley's in the morning and the country people would not give information to the southern army of the approach of the columne

SPRING This road was used by the enemy in the morning

KNIGHT'S The larger number returned by this road in the evening.

DOGAN'S JULY 21ST, 1861. MAJOR SCOTT 4th Alab. wounded in retreat

MAYHEWS STONE GENL. BEE & BARTOW'S command were in advance here in the morning

Lt. Davison 2d position

Van Pelt

Genl. Evans H.Q.

STONEBRIDGE

Enemy's battery opeed fire in the morning

When the retreating column reached this point and saw our cavalry onthe turnpike the panic seized the entire columne.

Here, wagons sotes, the siege gun or 30 pounder, arms, baggage and every thing was abandoned to facilitate their retreat.

This is the flat side of the creek and back to the road does not usually rise more than 15 or 20 feet above the creek bottoms. All enclosed is in cultivation. Opposite or west wide of the creek is bluff.

BULL RUNN

N.H. VT. R.I. N.Y. 69th Ice House CARTER POPLAR or RED HILL FORD

BOAT HOWITZER 4th ALA. COL. JONES BATTLE FIELD in the morning BARTON'S horse shot

N. YORK 7TH wounded GEO. 8th

N.O. Tigers

The enemy made a stand her about 4 P.M., on the retreat our batteries into their columne and here the rout began.

DUMFRIES (ON POTOMAC) ROAD

First colors planted over Sherman's battery were regiment colors of the 7th Georgia. captured battery

RICKET'S or SHERMAN'S captured here

captured battery Geo 7 Regt.

Jim. Robinson free Negro

Washington

N.O. Battery Capt. Inboden's battery

BATTLE FIELD IN THE AFTERNOON

Old woman killed in this house

BARTOW killed

Washington Artillery

Cummings Allen Preston Echols Harper Gl. Jackson's brigade

PENDLETON'S BATTERY came into action at 12 1/12 P.M. This Battery dismounted Rickett's called Sherman's battery and killed 45 horses. General Bee and Col. Bartow, after their retreat from the turnpike formed under Genl. Jackson's command.

When Genl. KIRBY SMITHS reinforcement (Elzy's brigade) came up about 3 1/12 P.M. Beauregard remarked, Elzy you are the Blucher of the day.

GEN. Bee killed Cumming' Regt. charged and took this battery when Col. Thomas of Mard was killed

Battery twice capture

caisson blew up

Enemy advanced thus far and retreated by Sudley's Ford

WARRENTON TURNPIKE AT ALEXANDRIA BY CENTREVILLE AND FAIRFAX COURTHOUSE

SUSPENSION BRIDGE

CUB RUN

The enemy opened fire below Mitchell's Ford in the morning to deceive our officers as to the crossing above at Sudley's Ford. In the afternoon, about 4 o'clock heavy firing was resumed here and was effectual in diverting our troops from the pursuit to this point.

HIGH HILLS

The largest group of the enemy was on the turnpike two miles east of Centreville. The prisoners state they left camp at one A.M. the morning of the 21st July 1861. They turned out at Widow Spindle's about 7 A.M. crossed at Sudley's Ford at 10 A.M., east dinner in the woods and were ready for fight at 12 M. July 21st 1861.

United States reserved forces

High point overlooking the battlefield July 21st 1861.

United States reserved forces

OLD FIELD OF THICK PINE UNDERGROWTH

LEWIS House

Where Capt. Ricketts and Wilcox were carried after being wounded.

Good skirmishing was done all day by many regiments and stragglers, but Genl. Jackson' brigade held their position during the fight; After they were assigned a place, Seibel's regiment marched 22 in the afternoon.

PENDLETON'S BATTERY

here at 12 M. marched 4 miles in 30 minutes

Our army was distributed along Bull Run on the 21st of July 1861 from the Stone Bride to Union Mllls. The entire plan of the Battle was changed by the enemy crossing at Sudley's Ford, and taking position about the Carter House.

WARE's HOUSE ROAD TO CENTREVILLE MITCHELL'S FORD

GEN. BEAUREGARD's Head Quart. after the Battle of July 21st.

McLANE'S

GENl. JOHNSTON'S Head Quarter

Major Harrison and Lieut. Miles killed in the battle July 18th, 1861

Washington Light Artillery in the bottom

BLACKFORDS FORD

Enemy's Battery

McLEAN'S FORD

July the 18th 1861

Many on the retreat after crossing Sudley's Ford did not turn down the run but went across towards the Potomac

ENEMY's Camp Timber felled around about 60 feet wide as abbatis, and the enhancements in front supposed to have been done under the flag of truce for burying their dead, July the 19th of 1861

This Battery kept up firing in the morning of the 21st to deceive Beauregard and Johnston. It fired again in the afternoon at 4 o'clock and cause troops to be sent here that should have been used the the Stone Bridge. It is said a Courier was killed who had orders for Gen. Ewell's Brigade on our right wing to flank the enemy. Ewell's Brigade marched across the run in the afternoon, but returned back on account of false alarm.

ROAD TO UNION MILLS

GENl. BEAUREGARD'S Head Qrs before the Battle

MANASSAS GAP R.R.

MANASSAS

UNION MILLS

FOUR MILE CREEK

ORANGE AND ALEXANDRIA R.R.

Miles reserve made a stand on these hills on the evening of the 21st. but as the routed army approached the wing broke and pushed on to Alexandria.

VERY HIGH HILLS

Spring

CENTREVILLE

The left wing of the enemy retreated from the Mitchells Farm at 6 P.M. July 21st and held this position in the line of battle until 11 1/2 P.M. when he retreated toward Alexandria

Copy from a lithograph Bureau of Topl. Engrs. October 1st, 1861

LITH. OF HUGER & LUDWIG, RICHMOND

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

#12

This is another one of my favorites, but for different purposes. As much as flashy equipment and extravagant detail impress me, I still have a soft spot for simpler design.

1st Lieutenant Jesse Hopkins, USA exemplifies that in my mind.

Really, what you see is what you get. Not really much more than a different styling of the usual Action Soldier equipment, though one suited for the Korean War.

The Korean War was an unwelcome shock to the US, being a relatively stagnant war after the dramatic victories of WW2. Instead of taking huge swathes of land in enormous campaigns, the majority of the war consisted of largely gaining or losing small chunks of land. From time to time there might be the occasional trench raid, where Lt Hopkins would come in. As an artillery lieutenant, he would be charged with coordinating a battery in firing on a specific location as requested by a given infantry unit. As such he’s relatively lightly armed with the then-new M2 carbine

and an M1911

On his head he wears a fur lined winter hat, part and parcel a copy of the Russian’s ushanka hat. In a very welcome feature of usability, the flaps can actually be folded down and snapped closed.

The rest of his uniform represents slight improvements from WW2, including the M-1943 boots and the M-1951 field jacket, successor to the venerable M-1943 jacket.

The Korean War distinguished itself in another way: being the first war in which US troops were assigned to fully integrated units. Therefore, Lt Hopkins could very well have been commanded white artillerymen, unthinkable just five years prior.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

• Battle of Pointe du Hoc

Pointe du Hoc is a promontory with a 100-foot (30 m) cliff overlooking the English Channel on the northwestern coast of Normandy in France. During World War II it was the highest point between the American sector landings at Utah Beach to the west and Omaha Beach to the east. The German army fortified the area with concrete casemates and gun pits. On D-Day, the United States Army Ranger Assault Group attacked and captured Pointe du Hoc after scaling the cliffs.

Pointe du Hoc lies 4 mi (6.4 km) west of the center of Omaha Beach. As part of the Atlantic Wall fortifications, the prominent cliff top location was fortified by the Germans. battery was initially built in 1943 to house six captured French First World War GPF 155mm K418(f) guns positioned in open concrete gun pits. The battery was occupied by the 2nd Battery of Army Coastal Artillery Regiment 1260. To defend the promontory from attack, elements of the 352nd Infantry Division were stationed at the battery.

The plan of attack called for the three companies of Rangers to be landed by sea at the foot of the cliffs, scale them using ropes, ladders, and grapples while under enemy fire, and engage the enemy at the top of the cliff. This was to be carried out before the main landings. The Rangers trained for the cliff assault on the Isle of Wight, under the direction of British Commandos. The assault force was carried in ten landing craft, with another two carrying supplies and four DUKW amphibious trucks carrying the 100-foot (30 m) ladders requisitioned from the London Fire Brigade. One landing craft carrying troops sank, drowning all but one of its occupants; another was swamped. One supply craft sank and the other put the stores overboard to stay afloat. German fire sank one of the DUKWs. Once within a mile of the shore, German mortars and machine guns fired on the craft.

These initial setbacks resulted in a 40-minute delay in landing at the base of the cliffs, but British landing craft carrying the Rangers finally reached the base of the cliffs at 7:10am on June 6th, 1944 with approximately half the force it started out with. As the Rangers scaled the cliffs, the Allied ships USS Texas, USS Satterlee, USS Ellyson, and HMS Talybont provided them with fire support and ensured that the German defenders above could not fire down on the assaulting troops. The cliffs proved to be higher than the ladders could reach. The original plans had also called for an additional, larger Ranger force of eight companies (Companies A and B of the 2nd Ranger Battalion and the entire 5th Ranger Battalion) to follow the first attack, if successful. Flares from the cliff tops were to signal this second wave to join the attack, but because of the delayed landing, the signal came too late, and the other Rangers landed on Omaha instead of Pointe du Hoc.

When the Rangers made it to the top, they had sustained 15 casualties. The force also found that their radios were ineffective. Upon reaching the fortifications, most of the Rangers learned for the first time that the main objective of the assault, the artillery battery, had been removed. The Rangers regrouped at the top of the cliffs, and a small patrol went off in search of the guns. Two different patrols found five of the six guns nearby and destroyed their firing mechanisms with thermite grenades.

The costliest part of the battle for Pointe du Hoc for the Rangers came after the successful cliff assault. Determined to hold the vital high ground, yet isolated from other Allied forces, the Rangers fended off several counter-attacks from the German 914th Grenadier Regiment. The 5th Ranger Battalion and elements of the 116th Infantry Regiment headed towards Pointe du Hoc from Omaha Beach. However, only twenty-three Rangers from the 5th were able to link up with the 2nd Rangers during the evening of June 6th, 1944. It was not until the morning of June 8th, that the Rangers at Pointe du Hoc were finally relieved by the 2nd and 5th Rangers, plus the 1st Battalion of the 116th Infantry, accompanied by tanks from the 743rd Tank Battalion.

At the end of the two-day action, the initial Ranger landing force of 225+ was reduced to about 90 fighting men. In the aftermath of the battle, some Rangers became convinced that French civilians had taken part in the fighting on the German side. A number of French civilians accused of shooting at American forces or of serving as artillery observers for the Germans were executed.

#history#military history#military#us history#army rangers#army history#united states#d day#french history#german history#second world war#world war 2#wwii#world war ii#pointe du hoc

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Summary Statement, 2nd Quarter, 1863 – 1st Regiment, US Regulars

Summary Statement, 2nd Quarter, 1863 – 1st Regiment, US Regulars

So to start the review of the summary statements from the second quarter, 1863, the First Regiment of the US Artillery is appropriately at the front of the queue:

The batteries of the First were detailed to assignments across various theaters of war, though not to the Trans-Mississippi. Looking at the administrative details by battery:

Battery A– Reporting at Port Hudson, Louisiana with four…

View On WordPress

#1st US Artillery#Alanson Randol#Battery A 1st US Artillery#Battery B 1st US Artillery#Battery C 1st US Artillery#Battery D 1st US Artillery#Battery E 1st US Artillery#Battery F 1st US Artillery#Battery G 1st US Artillery#Battery H 1st US Artillery#Battery I 1st US Artillery#Battery K 1st US Artillery#Battery L 1st US Artillery#Battery M 1st US Artillery#Beaufort SC#Chandler P. Eakin#Edmund C. Bainbridge#Fort Macon#George Woodruff#Guy V. Henry#Hilton Head#James E. Wilson#Loomis L. Langdon#Manchester PA#Philip D. Mason#Port Hudson#Richard C. Duryea#Warrenton VA#William Graham

0 notes

Text

Weapons at sea - Cannons

In ancient times ramming spurs were used on the hulls of ships to attack enemy ships. As the ships grew larger and heavier and the ram spur became less important, the ships were equipped with centrifugal devices, so that stone balls and arrow projectiles could be launched in the direction of the enemy. The Byzantines developed the so-called Greek fire as a special offensive weapon, which sprayed a burning liquid over a certain distance by means of a bundled jet. So-called fire lances have been used on Chinese warships since their first development in the 11th century. At that time, these handguns were initially still made of bamboo cane.

Despite these weapons, naval battles were fought mainly similar to land battles, i.e. in infantry man-to-man combat, where the ships served as floating battle platforms. Only with the invention of the black powder the fight was designed from man to man for the distance. In Europe cannons were common on ships since the 14th century. These were mainly weapons of small calibre, some of them breech loaders, as well as smaller colubrines, which were intended more for use against the crew than against the ship's hulls ('man-killers'). The first known use of ship guns took place in 1340 in the naval battle of Sluis. At that time there were galleys equipped with a gun at the bow (hunting cannons), but these ships were still intended for close combat by boarding.

The first heavier black powder guns to appear in the 15th century were bombards, which were varied and adapted to different functions over the following centuries. In the 15th century, the calibre of the cannons grew to such an extent that they could also be used effectively against the wooden side walls of the enemy ('ship-smashers'). In addition, more and more muzzle-loaders were used, which were cast from one piece of bronze and later iron.

Around the year 1500, gun ports were installed on sailing ships along the ship's hull, as the guns could no longer be placed high in the superstructures due to their higher weight. They fired over so-called piece ports in the broadside. In the beginning, the gun ports were still arranged directly above each other (for example in the Great Harry galleon of 1514) - it was only in the further development of the ship types that it was discovered that the so-called chessboard arrangement of the gates offered structural and tactical advantages. This development also led to the galley being replaced by the much more effective sailing warship. By the beginning of the 17th century, the development of muzzle-loading smoothbore artillery had been largely completed. The liner ships carried the majority of the guns on two or three continuous battery decks with the heaviest guns on the lowest deck. In the middle of the 17th century, according to English inventories, these were the so-called Cannons, Demi-cannons and Culverines, which fired 42, 32 and 18 pounds (19, 14.5 and 8.2 kg respectively) of heavy iron bullets. On the upper deck there were lighter cannons. Breech loaders existed only as small calibers or as outdated pieces.

The Muzzle Loader Cannon

A muzzle-loader gun is a thick-walled iron or bronze tube closed at the rear. The walls of a cannon tube are not even over the whole length, but reinforced in some places. The wall thickness of the ground field is greater, because the explosion of the propellant charge takes place inside the tube, the head frieze is a reinforcement, which should protect the muzzle of the tube from damage by the escaping explosive gasesThe shield pins cast horizontally onto the pipe are a little closer to the ground than to the head of the cannon. With its trunnions, the pipe is stored on the rapert or the gun carriage. The trunnions are mounted in such a way that the rear part of the gun is somewhat heavier, but should be balanced in such a way that the height direction can be changed with as little effort as possible.

The size of the calibre diameter is decisive for the proportioning of the cannons. The length of the barrel is measured by a certain number of calibre diameters, as are the wall thicknesses of the barrel or the diameters of the trunnions, etc.The bore of the tube is cylindrical and is called the "soul". In muzzle-loading cannons it was smooth until well into the 19th century, i.e. the barrel did not have any cut-in grooves that gave the projectile a twist, as had been known for some time with handguns. Of decisive importance for the firing accuracy of the cannon is the precise central position of the soul axis. The bore has a larger diameter than the projectile intended for the cannon. The difference is called "play". In the 18th century this was still comparatively large, which meant a reduction of the bullet velocity, because a larger part of the explosive gases escaped unused.

The term "muzzle-loader" results from the necessity to load pipes of the described form from the front, i.e. first to insert the propellant charge and then the projectile. The propellant charge is ignited through the ignition hole in the ground field, at the end of the soul.Some cannons and other guns have chambers. These are cylindrical or hemispherical receptacles for the propellant charge in the bottom of the gun. They have a smaller diameter than the soul bore

The smooth muzzle-loading cannon was the most important naval weapon until the middle of the 19th century. Although there were numerous gradual improvements, cannons and mountings were very similar from the 17th to the beginning of the 19th century. Already in the 17th century most of the ship cannons were made of cast iron, although this material had disadvantages for guns compared to bronze. Iron cannons needed somewhat larger wall thicknesses, so that they were heavier than corresponding cannons made of this material despite the higher density of bronze. Due to the brittleness of the material, iron cannons tended to crack, not to mention the corrosion, and iron is more difficult to drill than bronze. The decisive advantage of cast iron was its relatively low price. In the late 18th century, the price of a bronze cannon barrel was seven to eight times that of an iron cannon of the same calibre. At the end of the 17th century bronze cannons could only be found in the English navy on prestige ships such as liners of the 1st rank or royal yachts, but for cost reasons it was not possible to equip even the ships of the 1st rank completely with bronze tubes. 1717 there were in the British navy only on three ships of 1st rank bronze cannons. When in 1782 the Royal George (built 1756) sank, she was apparently the last ship of the Royal Navy with an extensive, but not complete equipment of bronze tubes. Her subbattery 42 pounds consisted of captured and bored French 36 pounds (because the French pound was heavier than the British pound, the calibre diameter was close to the British 42 pound). Contrary to some suppositions, the famous Victory of 1765 probably never had bronze cannons on board in its existence.

In the 18th century the Netherlands, Sweden and England were the centres of iron artillery casting. Although there were problems with quality in these countries at certain times, French iron guns remained notorious for being inferior in the long term. Major developments in gun-casting technology originated in England, so that Prussia, Russia and even France, among others, used British specialists to expand their capacities.Cannons were named after the weight of the iron full sphere which they fired. In the navies of the different nations similar cannon sizes developed, but the pounds were nationally different - a French 24-pounder shot a bigger, heavier bullet than a British 24-pounder.Common calibers in the 2nd half of the 18th century were:

Great Britain: 42, 32, 24, 18, 12, 9, 6, 4, 3 English pounds ball weight France: 48, 36, 24, 18, 12, 8, 6, 4 French pounds Sweden: 36, 24, 18, 12, 8, 6, 4, 3 Swedish pounds

Many calibres had two or three different tube lengths. The last British 42-pounders, which were set up in the subbatteries of first-rate triplane batteries, were replaced towards the end of the century by 32-pounders, which had been the most important liner gun for a long time, because of their sluggishness. Among the new French designs cast from 1787, there were no more 48-pounders. Still in 1780, however, some bronze 18-pounders and 48-pounders had been cast. The latter were intended as armament for two 110-cannon ships.At the other end of the scale disappeared up to the end of the 18th century still before the 4-pounder of the 3-pounders largely from the British ship armaments, although they were to be found on smaller, more irregular vehicles of the navy (rented) still after 1800. Lighter cannons on the superstructures, among which 6- or 9-pounders are to be counted, were often replaced after the distribution of the carronades by these with the same or lower weight of larger calibre guns.

The fields or pieces and sections of the pipe:

A-E: Long field ( Le troisième renfort, la volée). B-C: Neck ( le collet). F-H: Midfield, cone field ( Le deuxième renfort). F-G: Belt ( la ceinture). I-N: Ground field, chamber field ( Le premier renfort). M: Vent field (Champ de lumiére).

Further parts

O-P: Cascable (Culasse). P-Q: Grape (Bouton). R: Vent patch. S: Trunnions (Tourillons). U: Muzzle (Bouche).

Munition

The most important type of munition was the full iron ball, which could be used equally against the hull, rigging and crew. Chain balls (two iron hemispheres connected by a short chain) or rod balls (so-called bars) (two iron balls connected by rods) were fired especially for use against the rigging. In addition, at short distances against the enemy crew, cartridges or hail were used, for example to defend against boarding. Although the range of the cannons was up to 2 km, the chances of hitting beyond a few hundred meters were extremely low. Around 1800, most commanders of the British Navy trained their guns to fire as fast as possible and tried to fire at a distance of a few 10 metres, making it virtually impossible to pass by. The combination of open fire, open gunpowder and the wooden ships with ropes and bad luck offered many occasions to lose the ships by fire or explosion. At very short combat distances, there was a danger for both sides that the muzzle flash and the loading plugs would first catch the enemy and then their own ship on fire. The jump back of the pipes during firing was another danger potential on the decks overfilled with humans. The artillery of a sail warship was normally able to penetrate the side walls of a comparable enemy at short distances. Due to the small size of the cannons, however, it was difficult to sink an opponent of the same size. The effect of the cannons was particularly directed when shooting into the fuselage against the enemy armament and crew, with which the majority of the losses resulted from splinters of wood. By the loss of masts or rigging a ship could be shot maneuvering incapable. In many single fights, i.e. in fights far away from the great sea battles, the commander of a ship was anyway careful with relative caution, as a capsized ship including captured crew and cargo (pinch) brought him and his own crew a lot of pinch money under certain conditions.

97 notes

·

View notes

Text

Private (later Lieutenant) Wesley Strang Caldwell[i] was yet to earn the Military Medal for his actions at Courcelette, the Somme, when this letter was published in the Huron Expositor on March 10, 1916. He was 20-years old, just shy of his 21st birthday by 40 days. He was a combat veteran claiming to have served continuously, along with his Battalion and his Brigade, for 137 days. This number is accurate as the Battalion entered the lines in the Ypres sector on the night of September 23, 1915 and the total days in active service until the date of the letter (written February 6, 1916) is precisely 137 days. Perhaps it was this attention to detail that would help him earn promotion to the rank of lieutenant.

Huron Expositor. March 10, 1916. Page 1.

Huron Expositor. March 10, 1916. Page 1.

His letter relates to the Battalion’s experiences before the battle at St. Eloi Craters as the Battalion is stationed in the Ridgewood Sector of Ypres during the latter half of January 1916 and is full of interesting points:

From the Front

The following letter was written by Pte. Wes. Caldwell, of the 18th Battalion, and whose home is in Hensall. He is well known in Clinton, having attended the Collegiate Institute there, before enlisting for overseas service. The letter is dated Belgium, Feb. 6, 1916[ii], as follows:

Dear Friend, — Am sitting beside a machine gun in a redoubt about 200 yards from the front line. Was transferred to the section about 10 days ago. We spent six days in the front line, then the next six here in the redoubt followed by another six in the front line, then we got into divisional reserve for the next six; thus taking twenty-four days for the round trip.

Our last term in the front line was rather exciting. Our bomb throwers had been aggravating the Germans all one night and they began to retaliate just before dawn. In all they must have sent over 150 rifle grenades and ball bombs on a frontage of 100 yards. Our gun was right in the midst of it, but fortunately none of the crew was injured. The parapet was blown flat in two places, but was speedily built up again that night.[iii]

The German rifle-grenade is much feared as it not only contains a very high explosive but also much heavy shrapnel. Their hand grenades are not so dangerous. There was a ball bomb exploded within ten feet of me one night but I was only scratched in a couple of places. The explosion lifted me clear off my feet but I came to earth again almost unhurt. The narrow escapes that some fellows have are nothing short of marvellous.

There is no danger of the Germans ever advancing any farther on the Western front. We are holding them with the greatest possible ease by a triple line that cannot be broken.

Our supply of munitions is fast mounting up in a supply which will be inhaustable [sic] before long; then the great offensive will commence, which will make the world sit up and take notice.

The cost of attempting to advance without the necessary munitions and supplies to back it up has been proven before. The people at home are wondering why we are not making more headway. The reason for that, is that, the Allies have already lost too many good men of account of the lack of artillery and shells. We are only waiting the time when nearly all the defences can be blown to pieces by artillery fire, when a general advance is made. Destructive bayonet charges are soon to be a thing of the past. Our artillery is now vastly superior to that of the enemy, in fact, the German batteries are almost afraid to open up for fear of the awful retaliation given them by our batteries.

Sniping is a great feature in trench warfare. We have one old sniper who is a regular Indian at the game. I believe he would scalp his victims if he could.

Am feeling as well as can be expected but the whole brigade is in need of a rest. We have created a new record for continuous service in the trenches. We have held this frontage for 137 days, which is 20 days longer than any brigade in the British Army has ever served without a rest, and we are still holding it.

Hoping you are well, I remain,

Sincerely,

W.S. Caldwell

The letter is addressed to a “friend” giving the only clue to who the audience is. The letter is pretty frank as to the experiences Private Caldwell has, even relating a close call with a German grenade. Perhaps it is a friend from the Clinton Collegiate? It is, perhaps, more casual and informative than a letter written to his parents and one wonders what they thought, if this was the case, if they read the letter in the newspaper.

Though the letter is dated February 6, 1916 this date may refer to a post mark. As Private Caldwell states, specifically, that he is “…sitting beside a machine gun in a redoubt about 200 years from the front line,” it can be surmised that the writing of the letter occurred while the Battalion was in the line in the La Clytte/Vierstraat sector and that the letter was posted when the Battalion went off the line into Brigade Reserve at Ridgewood on February 2, 1916. He relates the nature of the rotation of the battalions from front line to support line (redoubt), and then reserve line, though it appears that the Battalion cycled back and forth between front and support lines twice before it was moved to divisional reserve.

From this and the following paragraph it appears that Private Caldwell has been assigned to serve a machine gun. The Lewis Gun did not become part of the equipment of a Canadian Battalion until July 1916. It is possible that Private Caldwell was part of a Colt Machine Gun crew. The initial battalion allotment was two-guns per battalion.

Soldiers aiming a 1914-Model Colt Machine Gun, December 1914. Canadian War Museum, 199900004-171.

He relates, in some detail, an incident where the 18th Battalion was interdicting the German trenches with grenades. It is not clear why type of grenades being “thrown” by the Canadians but, as the grenades sent by the Germans in reply for the ‘aggravation’ created by the men of the 18th, it appears that the distance between the Canadian and German lines was such that the Canadian probably were using rifle grenades or some method to launch percussion grenades. The Germans replied with their Karabingranate M 1914 rifle grenade and the “ball bomb” Kugelhandgranate 1915 (a round grenade fired with launchers and timed fuses). It is interesting to note that Private Caldwell, or other men of the Battalion could identify the nature of the grenades during the action.[iv] The Karabingranate M 1914 rifle grenade, “…is much feared as it not only contains a very high explosive but also much heavy shrapnel,” while the Kugelhandgranate 1915, “…is not so dangerous.” Yet, it is this exact grenade whose, “…explosion lifted me clear off my feet but I came to earth again almost unhurt.” A touch of youthful bravado expressed in the letter. It was, perhaps with concern for those at home may take alarm at this last story, that Private Caldwell relates that this is, apparently, part of a series of “narrow escapes” and that their number makes these escapes “marvelous.” No matter how marvelous these escapes may be it is certain Caldwell’s parents would not take heart at the number of them, regardless if they were marvelous.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

An interesting note is he alludes to the fragile nature of the type and design of trenches in his sector. The parapet was, most likely, layers of sandbags above earth grade. The water table in this sector was very high and many of the trenches were shallow digs with walls of sandbags making up the construction of the trench as protection for the soldiers. This trench was subject to tiresome maintenance to keep it in good shape.

Note the shallowness of the trench and the multiple layers of sandbags about grade. ‘D’ Company, 1st Battalion, The Prince of Wales’s Leinster Regiment (Royal Canadians), in the front-line at St. Eloi, 1915./

Private Caldwell then touches on his assessment of the war to date and relates that the First World War will be, essentially to achieve tactical success, a war of artillery. His statement: “Destructive bayonet charges are soon to be a thing of the past,” is a recognition that the use of edged weapons will not be the primary agent of death in battle. But the inculcation of the use of bayonet through the bayonet courses and training to encourage aggression and élan in combat was so strong that the concept of the bayonet in the hands of a soldier as a weapon of fear is slow to die. Event after two years of war.

His reference, albeit, brief, to sniping, is of interest and the reference to, “…one old sniper who is a regular Indian at the game,” is not clear in its meaning. Is the sniper an aboriginal soldier or is the soldier that is sniping acting like a “regular Indian” in his use of tactics, concealment, and shooting. Note that sniping developed into a 2-man team based role and Private Caldwell does not reference another member of the team, so it is not clear if this sniper is working alone, or Caldwell simply does not mention the observer’s role in sniping.

He is obviously proud of the 4th Brigade’s achievement to the total time it spent in the line. This constant exposure to the weather and the stress of combat would require the C.E.F. to later modify the rotation of battalions and brigades as the war progressed. During this time (September to February) the 18th Battalion suffered 34 men fatalities, almost all due to combat. It was a precursor to the experiences the Battalion would experience at St. Eloi and the Somme, but at a much lower intensity than those actions.

Private Caldwell was to survive the war and several other letters from him were published in the local papers. This letter is rich in detail and information and allows one to experience part of his past. It would be interesting to exam the other letters and see how his point-of-view and tone changes as he becomes older and takes on the responsibilities of an officer.

Caldwell was to become an officer and returned to the 18th Battalion and served in that capacity until he was gassed during the Battalion’s engagement at Passchendaele on November 8, 1917. He would survive the war and return to Canada and live until 1972.

[i] Private Wesley Strang Caldwell, reg. no. 53661. Ref. RG 150, Accession 1992-93/166, Box 1387 – 56 Item Number: 82005

[ii] The Battalion was in Brigade Reserve at Ridgewood, Ypres Sector, Belgium when this letter was written. The 18th Battalion war diary relates for that day: -Ditto- [Routine] Communion service was held at 11 a.m. CAPT. HALE proceeded on leave. It appears that Caldwell started the letter some days before he dated it.

[iii] Note the accompanying images. Due to the high water table, the trenches in the Ypre sector were often not very deep and the “trench” height was maintained by several layers of sandbags.

[iv] The author is almost CERTAIN he would be under cover and would not make any effort to identify the type of grenade being used against him.

“The parapet was blown flat in two places…” Private (later Lieutenant) Wesley Strang Caldwell[i] was yet to earn the Military Medal for his actions at Courcelette, the Somme, when this letter was published in the Huron Expositor on March 10, 1916.

#artillery#Clinton Ontario#Colt Machine Gun#Karabingranate M 1914#Kugelhandgranate 1915#rifle grenades#sniper

0 notes

Text

US Army Sergeant Eric M. Houck. 10 JUN 2017.

Died in Peka Valley, Nangarhar Province, Afghanistan, of gunshot wounds sustained in Peka Valley, Nangarhar Province, Afghanistan while deployed in support of Operation Freedom’s Sentinel . The incident is under investigation. Houck was assigned to Headquarters and Headquarters Battery, 3rd Battalion, 320th Field Artillery Regiment, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) and Company D, 1st Battalion, 187th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Brigade Combat Team, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), out of Fort Campbell, KY.

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

AN ANGEL OF MERCY BECOMES THE WIDOW OF THE SOUTH I just returned in December from visiting the historic Carnton Plantation in Franklin Tennessee. While only one spot on the bloody battlefield of Franklin Tennessee on November 30th 1864, the story of that one bloody night is so incredibly horrific, that it defies the imagination. After the five hours of intense carnage and desperate hand to hand combat their would be roughly 10000 souls who were either killed, wounded or captured. Sarah North Martin was a resident of nearby Columbia, Tennessee just south of Franklin in November 1864 as both the Union and Confederate armies swept through the town during Southern General John Bell Hood’s “invasion” of Tennessee. Sarah, the wife of prominent local judge, William P. Martin, was taken by surprise on November 24, 1864 when two brigades of Union infantry under Brigadier General Jacob Dolson Cox Jr. commandeered ground on the Mount Pleasant Road. Before they were in position Union cavalrymen came hastily down the gravel road, fleeing from the brigades of Lieutenant General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Confederate cavalry. Cox had three artillery batteries along with his troops on both sides of the road. More Confederate troops later arrived and sought to displace the Yankees. Sarah Martin’s thoughts as she and her family escaped, are part of a remarkable letter she sent to a relative:

The fighting commenced at our house, which is situated about 50 yards from the road on a high hill. I dare not write the particulars. Suffice it to say the Yankees had possession of our home & forced us to leave. We went to Mr. Martin’s fathers’ [i.e. George M. Martin], about 800 yards nearer town, taking with us the bedding of three beds & most of our wearing apparel. We were between the fires of the two contending parties for two days, & five shells struck [his] father’s house while [we] were in it, until we had to go down to a brick milk cellar in the yard, the minie balls falling on the roof like hail. The wounded Yankees [kept] passing through the yard, bleeding & screaming with pain. We could hear the yells of the Rebels as they charged & drove the Yankees toward town. At last, when the fight was evidently beyond us, I ran out quickly to avoid the sharpshooters, & entering the [George M. Martin] house, found Gen. [Colonel Edmund Winchester] Rucker’s staff, who showed us every courtesy. Each officer took charge of one of us, & led us in the line of the house, over to [our] home; procured an ambulance and sent us down to Gen. Pillow’s. [this was “Clifton,” four miles west of Columbia, the home of Brigadier General Gideon Johnson Pillow, who was married to her husband’s sister (Mary Martin Pillow)] Gen. [Brigadier General Stephen Dill] Lee had possession of our house, & artillery was planted in several places on the hill. The Yankees [had] sacked our house, & set fire to it, but Forrest came in time to extinguish the flames, before any serious damage was done. They [Yankees] threw our wheat into the pond, burned piles of bed clothes & books, & threw our china all over the yard, took the most of twenty-two hogs, and killed nineteen shoats, took all our horses, etc. In short I cannot enumerate our loss, or tell you how the Yankees treated us. We have ever since been living on biscuit[s] & milk, without a parcel of meat, for we have no money to buy with. You can have no conception of the oppression, & we dare not murmur. Even yesterday they came & took the only animal we had, a mule. Judge M. [i.e. her husband Judge William P. Martin] walked to town to day in the rain to try to get it back, but was unsuccessful, & now we have nothing to plow with, or to haul wood, for we had been driven to hauling wood in a cart. We are very anxious to sell & move to Texas… All our negroes ran off during the fight, & went with the Yankees in their retreat to Nashville. Some of them want to come back, but we will not receive them. The Lord has mercifully preserved our health, & I hope will bring us safely through these troubled times. Just six days later both armies raced towards Nashville for a final bloody showdown. The Union Army was delayed in Franklin due to the swollen Harpeth River. They were ordered to hold their position and dig defensive fortifications as a purely protective measure until they received pontoons from Nashville to move men and equipment across. They did not believe that a major battle would ensue their. But Confederate Lt. General John Bell Hood had other ideas. Seeing the Union Army split and penned against the swollen stream, he decided to launch an all out offensive. General Jacob Dolson on this day would awake Fountain Branch Carter at 4:30 AM to inform him that his home was being commandeered. As the likely spectre of a major battle grew more likely, the town residents hunkered down to bear a fear and horror no human being should ever have to experience. The following are a list of eyewitness accounts of that cold terrible November evening in 1864: "The Men seemed to realize that our charge on the works would attend with heavy slaughter, and several of them came to me bringing watches, jewelry, letters and photographs, asking me to take charge of them and send them to their families if they were killed. I had to decline as I was going with them and would be exposed to the same danger. I was vividly recalled to me the next morning, for I believe every one who made this request of me was killed." Chaplain James H. M'Neilly Quarles Brigade "When Conrads brigade took up its advanced postion we all supposed it would be only temporary, but soon an orderly came along the line with instructions for the company commanders, and he told me that the orders were to hold the postion to the last man, and to have my sergeants fix bayonets and to instruct my company that any man, not wounded, who should attempt to leave the line without orders, would be shot or bayonetted by the sergeants." Capt John K. Shellenberger 64th Ohio Inf. "When I regained consciousness I was laying in the ditch . . of running water and could feel the loose dirt fall in on me when Yankee bullets would strike the top of the ditch . . I became thirsty but had fallen on my canteen but could not get to it... I drank the water in the ditch and it was cold and good. I knew my sight was destroyed. I placed my hands under my forehead to keep my face from above water .. and fell asleep" Lt. Mintz 5th Arkansas, Govans Brigade I saw a Confederate soldier, close to me thrust one of our men through with a bayonet and before he could draw his weapon from the ghastly wound his brains were scattered on all of us that stood near, by the butt of a musket swung with terrific force by some big fellow whom I could not recognize in the grim dirt and smoke.. As I glanced hurredly around and heard the dull thuds, I turned from the sickening sight and glad to hide the vision in work with a hatchet for I had broken my sword. Col Wolf 64th Ohio Conrad's Brigade "The slaughtering could be seen down the line as far as the Columbia and Franklin Pike, and where the works crossed the pike . . . Our troops were killed by whole platoons, Our front line of battle seemed to have been cut down by the first discharge for in many places they were lying on their faces in almost as good order as if they had lain down on purpose; but no such order prevailed among the dead who fell in making the attempt to surmount the Cheval-de-frise, for hanging on the long spikes of this obstruction could be seen the mangled and torn remains of many of our soldiers who had been pierced by hundreds of minie balls and grape shot ... The ditch was full of dead men and we had to stand and sit upon them. The bottom of it from side to side was covered with blood to the depth of shoe soles" James M. Copley 49th Tennessee Quarles' Brigade " as evening came on the neighboors began to come in . . and we went down in the cellar. Grandpa had already put rolls of rope in the windows. . to keep the bullets out. The negroes crouched down in the dining room, and all the children & grand children and neighbors in the hall cellar, and granpa walked back and forth and watched out the window." "The first sound of the firing and the booming of cannons, we children all sat around our mothers and cried." Alice M. Nichol age 8 Tod Carters neice "The mangled bodies of the dead rebels weere piled up as high as the mouth of the embrasure and the gunners said that repeatedly when the lanyard was pulled the embrasure was filled with men crowding forward to get in who were literally blown from the mouth of the cannon. Only one rebel got past the muzzle of the gun and one of the gunners snatched up a pick and killed him with that. the ditch was piled promiscuously with the dead and badly wounded and heads arms and legs were sticking out in almost every conceivable manner. The ground near the ditch was filled with the moans of the wounded and the pleadings of some of those who saw me for water and for help were heartrending." Capt John K. Shellenberger 64th Ohio Inf. Conrad's Brigade "Nothing could be heard but the wails of the wounded and the dying, some calling for their friends, some praying to be relieved of their awful suffering and thousands in the deep agonizing throes of death filled the air with mouthful sounds and dying groans" Capt. Hickey 1st Missouri Cockrells Brigade "I could hear the wounded calling for help in every direction. I again wanted water and thought I would again drink from the water in the ditch, biut this time it tasted of blood and I managed to get my canteen from under me and drank from it." Lt. Mintz 5th Arkansas, Govans Brigade (who has been blinded) "I stood on the parapet just before midnight and saw all that could be seen. I saw and heard all that the eyes, or my rent soul contemplate in such an awful environment. It was a spectacle to chill the stoutest heart...the wounded shivering in the chilled November air; the heartrending cries of the desperately wounded and the prayers of the dying filled me with an anguish that language cannot describe. From that hour I have hated war. Colonel Isaac Sherwoood 111th Ohio Infantry "I remember seeing one poor fellow, sitting up and leaning back against something whose lower jaw had been cut off by a grape shot, and his tongue and under lip were hanging down on his breast. I knelt down and asked if I could do anything for him. He had a little piece of paper and an envelope. He wrote: No, John Bell Hood will be in New York before three weeks." Teenager Hardin Figuers, Franklin resident moments after he emerged from shelter. �� "God forgive me for ever wanting to see or hear a battle! You had to look twice as you picked your way among the bodies to see which were dead and which were alive and often a dead man would be lying partly on a live one, or the reverse. And the groans, the sickening smell of blood! I noticed while wandering along the earthworks that all or nearly all of the Union soldiers were shot in the forehead. In front, the ground was covered with bodies and pools of blood. the cotton in the old cotton gin was shot out all over the ground. Our Union soldiers had been stripped of everything but their shirts and drawers, but the Confederate soldiers could not be blamed much for that, for they were half clothed, half barefoot and many of them bareheaded." Carrie Snyder; a Union sympathizer who happen to be visitig friends in Franklin at the time. "In this yard and in that garden, I could walk from fence to fence on bodies, mostly those of Confederates. In trying to clean up, I scraped together a half a bushel of brains right around the house, and the whole place was dyed in blood. Nothing in the shape of horse, mule, jack, nor jinny was left in this neighborhood. In fact I remember it was not untilChristmas, twenty five days afterwards, that I was enabled to borrow a yoke of oxen, and I spent the whole of that Christmas Day hauling seventeen dead horses from this yard." Moscow Carter: Brother of Captain Tod Carter recalling what he saw upon emerging from The Carter House root cellar. "Amid the hundreds of dead and wounded Confederates who lay thickly scattered over the field in our front....there was one lying in front of my company, only a few distant feet crying "Mother you were right, you'll never see your boy again. I'm dying out here in the dark....I'm bleeding to death. "The boy's voice became gradually weaker and weaker until we heard it no more......One of the company's new recruits, a mere boy in years, was crying as though his heart was broken. He too was the only son of a widowed mother.": An unknown officer of the 63rd Indiana. The carnage was so great throughout the town that any available structure was used as a hospital. To put this into proper perspective, for every single resident who resided in Franklin Tennessee (pop. approx. 900) there were 7 casualties. The Carnton house quickly became a field hospital for Confederate wounded. It was a ghastly scene of pain , torment, and suffering. The McGavocks tended for as many as 300 soldiers inside Carnton alone, though at least 150 died the first night. John and Carrie McGavock and their 9 yr old daughter Hattie and 5 yr old son Winder helped tend the over 300 men who lay throughout the home. Soon the outbuildings were filled with hundreds more until the only place to lay them were in the yard. After the battle, on December 1, Union forces under Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield evacuated toward Nashville, leaving their dead, including several hundred Union soldiers, and their wounded who were unable to walk. The residents of Franklin were then faced with the task of burying over 2,500 soldiers, most being Confederates.The following are some of the first hand accounts of the nightmarish eve at Carnton: "Every room was filled, every bed had two poor, bleeding fellows, every spare space, niche, and corner under the stairs, in the hall, everywhere -0 but one room for her own family. Our Doctors were deficient in bandages, and she began by giving her old linen, then her towels, amd napkins, then her sheets and table clothes, then her husband's shirts and her own undergarment. During all this time the surgeons plied their deadful work amid the sighs and moans and death rattle. Yet amid it all, this nobel woman. . . was very active and constantly at work. During all the night neither she nor any of the household slept, but dispensed tea and coffee and such stimulants as she had and that two with her own hands.. she walked from room to room from man to man her very skirt stained with blood." Capt. William D. Gale - Lt. Gen Alexander P. Stewart's staff "Give me forty grains of morphine' he called out all through the night. 'Give me forty grains of morphine and let me die!' 'Oh Can't' I Die?' ' My Poor Wife and Child!'' My Poor Wife and Child!' "OMG ! Can you get the surgeons to administer some drug that will relieve me of this torture" I did try through my appeals were in vain. " Cold presperation gathered in knots on his brow and of course (he) knew that death was inevitable. . . "I went down the steps and far beneath the silence of the stars to escape his piteous prayers." C. E. Merrill Adjutant General , Brig. Gem Scott's Staff All of the Confederate dead were buried as nearly as possible by states, close to where they fell, and wooden headboards were placed at each grave with the name, company and regiment painted or written on them." Many of the Union soldiers would later be re-interred in 1865 at the Stones River National Cemetery in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Over the next eighteen months many of the markers either rotted or were used for firewood, and the writing was disappearing. To preserve the graves, John and Carrie McGavock donated 2 acres of their property to be designated as an area for the Confederate dead to be re-interred. The citizens of Franklin raised the funding and the soldiers were exhumed and reburied in the McGavock Confederate Cemetery for the sum of $5.00 per soldier. A team led by George Cuppett took responsibility for the reburial of 1,481 soldiers. The names and identities of the soldiers were recorded in a cemetery record book by Cuppett, which soon fell into the care of Carrie McGavock. It is said that for years following the war visitors would knock on her door requesting the book to see if they could find closure from the loss of a loved whom they never knew of their fate. Carrie never failed to fulfill those requests. Carrie McGavock spent nearly 40 years of her life maintaining the McGavock Confederate Cemetery. In her later years she also would help to raise orphaned children, many of which were created by that bloody war. It was the most sincere expression of the heart and compassion she personified for so many years. Carrie died in 1905 and rests beside her husband, John, within sight of the nearly 1,500 Confederate soldiers who they protected and watched over for so many years. The mere thought of young children having to witness so much blood and suffering should draw deep emotions from even the coldest of souls. This was truly an experience where nightmares were born. Harriet (Hattie), Young McGavock was only nine-years-old on the day of the Battle of Franklin. That afternoon and night, she and her younger brother, five year old Winder, and their parents, John and Carrie, watched as their home became a hospital and mortuary. Hattie and Winder worked alongside their parents throughout the night, helping where they could as the battered bodies poured in to the house. The next morning, the bodies of four Confederate generals, who had been killed in the fighting, were brought to the McGavock home and laid side-by-side on the back porch. They were Patrick Cleburne, John Adams, Hiram Granbury, and Otho Strahl.

In Hattie McGavock Cowan's own words over 50 years later:

I can still sense the odor of smoke and blood. I recall how the startled cattle came home from the pastures, how restless they became, sniffing and excitedly running about the place, bewildered by the smell of the battlefield. I can still see swarms of soldiers coming with their dead comrades and lying them down by the hundreds under our spacious shade trees and all about the grounds. I shall carry those awful pictures in my mind down to the day of my death. I was only nine-years-old then, but it is all as vivid and as real as if it happened only yesterday. I overheard a man at Carnton that night say he estimated over 300 wounded were crammed in to our home. There we were in this ocean of suffering — mother, father, Winder and me — going from man-to-man doing what we could. Mother ordered the bed sheets and linens torn into bandages. Those ran out so, she told the medical attendants to use her tablecloths, towels, and father’s shirts. At one point, she used her own undergarments, put to use mending the myriad of wounds. Those who saw her were awestruck by her selfless actions. Mother never ceased in her work that long and dreadful night. She handed out tea and coffee and went from room to room making sure there was nothing else she could do. William D. Gale, of Gen. A.P. Stewart’s staff, said mother was so involved in affairs that her skirt was “stained in blood.” I remember it vividly. Some of the soldiers recuperated at our home until June, nearly seven months after the battle. There was a lot of bad, but there was a lot of good. You sometimes see the best in people under these circumstances. We just went to work and did what we could. I stuck by my mother. Chaplains, doctors, and agents of the U.S. Christian commission showed up over the coming weeks and months.

What happened to Hattie McGavock Cowan?

She married a Confederate veteran named George Cowan at Carnton on January 3, 1884. They lived in close proximity to Carnton for many years in a home known as Windermere. George died in 1919. Hattie lived until 1931 and for many old Franklin residents she was the last living connection to the Battle of Franklin. She is buried with George at Mt. Hope Cemetery in Franklin. Winder Mcgavock took over Carnton after his mother's death in 1905. He died just two years later. While touring Carnton (which would cost over 10 million in modern day currency) visitors can still see the blood stains in the wooden floors from over 150 years ago. The operating table used by surgeons was set up "rather ironically" in the nursery. It consisted of two saw horses and a barn door. It is still on display their today. Hattie Mcgowan quite vividly retold of her memories of that bloody night in an interview she gave shortly before her death in 1931 recalling the smell of blood and powder smoke and the sounds of the intense suffering of the wounded. One can only imagine the nightmares these two children experienced for years afterwards.

0 notes

Text

Unusual Civil War vintage notes

By Mark Hotz

Last month, I brought to you a very interesting American short snorter of World War II vintage, this one belonging to none other than John A. Roosevelt, youngest son of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who served as a naval officer in the Pacific toward the end of the war. This month we will look at the Civil War.

This $1 bank note issued by the Girard Bank of Philadelphia (later the Girard National Bank) was found on the body of a dead Federal colonel at the Battle of Seven Pines, Va., in 1862.

Here is the back of the Girard Bank $1 note, with the inscription by Pvt. J.G. Stewart of the Confederate Mobile Cadets regiment.

Inscribed currency from the Civil War is rather hard to find, notwithstanding the occasional Confederate piece with someone’s attempted forgery of Robert E. Lee’s signature scrawled upon it. I have in my collection several unusual items of Civil War vintage. The first that I will present to you is a $1 bank note of the Girard Bank of Philadelphia, dated Jan. 9, 1862. Inscribed in bold pen on the back is the following:

“This Note was given / to Mrs. Celia Coe / By J. G. Stewart of / the Mobile Cadets/ He took it out of / a Federal Cols. / Pocket on the Battle / field of the Seven / Pines the first Battle / he was ever in / given to her at / Winchester Virginia / October 21st 1862.”

I am sure many of you can see how this item certainly piqued my interest, and my excitement was palpable when I obtained it. I initiated an Internet search in an effort to find out more about J.G. Stewart and the mysterious Mobile Cadets. After a short but determined inquiry, I found some information that really brought the item to life.

The Mobile Cadets were none other than Company A, 3rd Alabama Infantry Regiment. The Mobile Cadets consisted of volunteers from Mobile County, Ala., and was the very first company to volunteer to serve the Confederacy. The 3rd Alabama was the first regiment from that state to offer its services to the Confederate cause and the first to be sent to Virginia for mustering duties. Jones M. Withers was elected its first colonel.

The 3rd Alabama had been held in reserve in Norfolk for almost a year without seeing any action. Its “baptism of fire” came on June 1, 1862, at the battle known as Seven Pines to the Confederates and Fair Oaks to the Federals. This battle was part of the great Peninsula Campaign in which the Union Army, under the command of Gen. George McClellan, came within 10 miles of Richmond but failed to capture it.

This photo shows Battery B of the 1st New York Light Artillery at the Battle of Seven Pines.

This vintage postcard shows the entrance to the Civil War cemetery at Seven Pines.

The 3rd Alabama, with the Mobile Cadets as Company A, was held in reserve the first day of the of the battle (May 31, 1862), but was thrown into the fight and badly cut up on June 1, losing 38 killed in action and 122 wounded. Two weeks later, the regiment was made part of General Daniel Hills’ Division and took part in battles before Richmond. When the Confederates advanced across the Potomac in September, the 3rd Alabama was the first Confederate regiment to plant the Stars and Bars flag in Maryland. It was engaged in heavy fighting at Boonsboro and Antietam before retreating with the rest of the army into the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia.

On one website, I was able to find a roster roll of the 3rd Alabama Infantry Regiment. All of the men were listed alphabetically, with their company and rank. Eagerly and with anticipation, I scrolled down to “S.” Stewart had been in Company A, the Mobile Cadets. He had enlisted as a private and ended his service as a sergeant. There was no indication of whether he had been wounded or killed.

It was very exciting to be able to make this currency-related relic come alive. At least now I knew something about Pvt. Stewart and his unit. I do not know his relationship to Mrs. Celia Coe, but I can surmise from the date inscribed that the regiment had been regrouping in Winchester after the Battle of Antietam. Perhaps Stewart had been billeted in Mrs. Coe’s home?

I have yet to determine the identity of the officer from whose pocket the note was taken, but how many colonels of Philadelphia units could have fallen at Seven Pines? If any readers can offer any further assistance here, I would be grateful.

This 10-cent currency note issued by the Corporation of Winchester, Va., in 1861 was taken from Colonel Robert F. Baldwin, commander of the 31s Regiment of Virginia Infantry, when he was captured at the Battle of Bloomery Gap, Feb. 14, 1862.

The back of the Corporation of Winchester note with the inscription indicating that note was taken from Col. Baldwin on his capture. The Federal forces referred to the battle as Blooming Gap at the time, though the real location was Bloomery Gap.

The next item I’ll present to you I was very fortunate to find just in the last month. While visiting an out-of-state coin shop, I came across a Corporation of Winchester, Virginia, 10-cent note issued Oct. 4, 1861. This in itself is not a rare note and can generally be found on the market for a very reasonable price. However, when I turned it over, I found a most interesting pen inscription, which resulted in my adding this note to my collection. It read as follows:

“This was found upon the person of Col. Baldwin, on his being made prisoner at Blooming Gap.”

Above the ink inscription, in a far less sophisticated hand, and in pencil, was scrawled “Col. Baldwin Blooming Gap.” This looked all very intriguing to me, and though I had never heard of Blooming Gap, I thought it was worth researching.

Here is what I learned. It turned out that what the Federals called Blooming Gap was actually known as Bloomery Gap, and a battle took place there on Feb. 14, 1862. Early in 1862, Confederate raids and attacks put Hampshire County, Va. (now West Virginia) and much of the surrounding area under nominal Southern control. The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and nearby telegraph wires were severed, impeding Federal troop movements.

A militia brigade under Col. Jacob Sencendiver, 67th Virginia Militia, occupied Bloomery Gap to threaten the railroad and Union-occupied territory near the Potomac River. To drive them out, Union Gen. Frederick W. Lander led a mixed force of infantry and cavalry south from Paw Paw, Morgan County, on the afternoon of Feb. 13. He intended to strike Sencendiver’s position at dawn the next morning, but bad weather and high water delayed him long enough for the Confederate pickets to give warning.

Sencendiver hastily ordered the wagons packed and sent east while posting the 31st Virginia Infantry to block Lander’s advance. Lander led the charge of part of the 1st West Virginia Cavalry (Union), overrunning and scattering the Virginians and capturing many officers and men, as well as the wagon train. Sencendiver rallied the 67th and 78th Regiments, however, and recaptured the wagons. The Federals returned to Paw Paw while the Confederates marched to Pughtown, leaving the railroad and telegraph lines open for the day. Sencendiver soon reoccupied the gap.

This lithograph of a Federal Cavalry charge, ostensibly at Bloomery Gap, was published in ‘Harper’s Weekly’ in February 1862.

The battle routed the Confederates, who lost 13 killed and 65 captured. Among the officers captured was none other than Col. Robert F. Baldwin, commander of the 31st Virginia Infantry regiment. Baldwin and his staff were surprised by the Federal cavalry, and Baldwin surrendered to Gen. Lander personally. A report submitted by Sencendiver to the Headquarters of the 16th Brigade, Virginia Militia, on Feb. 17, included a reference to Col. Baldwin:

“Our advanced pickets came in about daylight and reported the enemy advancing upon us in large force. I gave orders to have the baggage packed immediately and the men prepared to meet the enemy and repulse him if possible. The Thirty-first Regiment, Colonel Baldwin, being quartered nearer the point from where the enemy was advancing than the balance of the command, rushed hurriedly to meet him…Our loss, I regret to say, is over 50 officers and privates missing. Annexed is a list of officers captured: Col. R. F. Baldwin, Thirty-first Regiment; Capts. William Baird, acting assistant adjutant-general, and G. M. Stewart, Eighty-ninth Regiment…”

Baldwin was eventually sent as a prisoner to Fort Warren, located in Boston Harbor. On May 16, 1862, Brig. General Lorenzo Thomas, Adjutant General of the Union Army, sent the following message to Col. J. Dimmick, commander at Fort Warren: “SIR: You are authorized and directed to transfer Colonel R.F. Baldwin, Thirty-first Virginia Regiment, now in your custody, to Gen. Wool at Fortress Monroe, to be held by him for exchange of Colonel Corcoran, now a prisoner at Richmond.”

At the same time, Thomas wrote to Maj. Gen. John E. Wool, commander of Fortress Monroe to that effect, adding “…Upon his (Baldwin’s) arrival at Fortress Monroe, you will notify the rebel officer nearest to you that he is there to be exchanged for Colonel Corcoran, now a prisoner in Richmond, and upon the arrival of the latter at Fortress Monroe, you are authorized to release Colonel Baldwin.”

Col. Corcoran was the commander of the 69th New York Infantry Regiment who had been captured at First Bull Run. I have not been able to trace Baldwin after the point of his exchange, which took place in August. The 10-cent note that I acquired was obviously taken from the colonel’s possessions. The penciled inscription was probably made at the time by the soldier who was responsible for searching the colonel. Later, the pen inscription was added. But what an interesting story it is. The Battle of Bloomery Gap was a small one-day affair, and this note may well be the sole remaining souvenir of that fight.

This photo shows the Battle of Bloomery Gap historical marker, located on WV State Route 172 in front of the Bloomery Gap Presbyterian Church.

Today, the Battle of Bloomery Gap is largely forgotten, with just a historical marker placed in front of the Bloomery Gap Presbyterian Church on West Virginia Route 127 in Bloomery, located just across the line from Virginia, about 20 miles northwest of Winchester. I have included a photo.

Readers may address questions or comments about this article to Mark Hotz directly by email at [email protected].

This article was originally printed in Bank Note Reporter. >> Subscribe today.

More Collecting Resources

• Order the Standard Catalog of World Paper Money, General Issues to learn about circulating paper money from 14th century China to the mid 20th century.

• Any coin collector can tell you that a close look is necessary for accurate grading. Check out this USB microscope today!

The post Unusual Civil War vintage notes appeared first on Numismatic News.

0 notes

Text

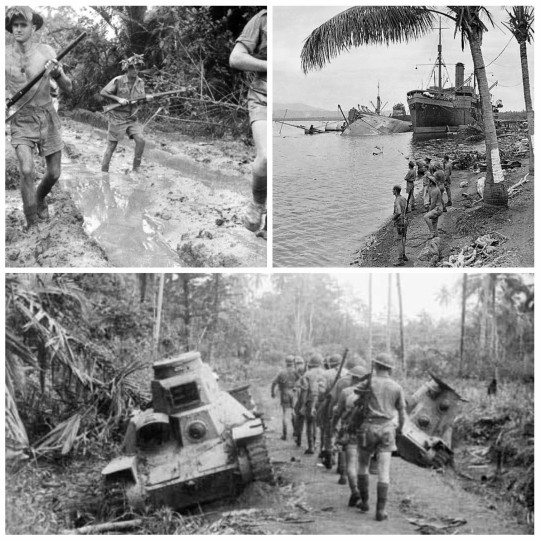

• Battle of Milne Bay

The Battle of Milne Bay, also known as the Battle of Rabi by the Japanese, was a battle of the Pacific campaign of World War II.

Milne Bay is a sheltered 97-square-mile (250 km2) bay at the eastern tip of the Territory of Papua (now part of Papua New Guinea). It is 22 miles (35 km) long and 10 miles (16 km) wide, and is deep enough for large ships to enter. The coastal area is flat with good aerial approaches, and therefore suitable for airstrips, although it is intercut by many tributaries of rivers and mangrove swamps. The first troops arrived at Milne Bay from Port Moresby in the Dutch KPM ships Karsik and Bontekoe, escorted by the sloop HMAS Warrego and the corvette HMAS Ballarat on June 25th. The troops included two and a half companies and a machine gun platoon from the 55th Infantry Battalion of the 14th Infantry Brigade, the 9th Light Anti-Aircraft Battery with eight Bofors 40 mm guns, a platoon of the US 101st Coast Artillery Battalion. On July 11th, troops of the 7th Infantry Brigade, under the command of Brigadier John Field, began arriving to bolster the garrison. The brigade consisted of three Militia battalions from Queensland, the 9th, 25th and 61st Infantry Battalions.

Japanese aircraft soon discovered the Allied presence at Milne Bay, which was appreciated as a clear threat to Japanese plans for another seaborne advance on Port Moresby, which was to start with a landing at Samarai Island in the China Strait, not far from Milne Bay. On July 31st the commander of the Japanese XVII Army, Lieutenant General Harukichi Hyakutake, requested that Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa's 8th Fleet capture the new Allied base at Milne Bay instead. Under the misconception that the airfields were defended by only two or three companies of Australian infantry (300–600 men), the initial Japanese assault force consisted of only about 1,250 personnel. The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) was unwilling to conduct the operation as it feared that landing barges sent to the area would be attacked by Allied aircraft. As a result, the assault force was drawn from the Japanese naval infantry, known as Kaigun Rikusentai (Special Naval Landing Forces). led by Commander Masajiro Hayashi, were scheduled to land on the east coast near a point identified by the Japanese as "Rabi", along with 197 men from the 5th Sasebo SNLF, led by Lieutenant Fujikawa.

Following the battle, the chief of staff of the Japanese Combined Fleet, Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki, assessed that the landing force was not of a high calibre as it contained many 30- to 35-year-old soldiers who were not fully fit and had "inferior fighting spirit". The Japanese enjoyed some initial advantage in the form of possessing two Type-95 light tanks. After an initial attack, however, these tanks became marooned in the mud and abandoned. They also had control of the sea during the night, allowing reinforcement and later evacuation. Over the course of the 23th and 24th of August, aircraft carried out preparatory bombing around the airfield at Rabi. The main Japanese invasion force left Rabaul on August 24th, under Matsuyama's command.