#Balzac Billy

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Groundhog Predictive Success Rate

#tous le monde connait Fred la Marmotte!#Balzac Billy and Shubenacadie Sam are great names. sorry Manitoba Merv....#Wiarton Willie has the worst rate#Groundhog#Groundhog Day

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

why has NOBODY ever told me that Alberta's groundhog is a) not a groundhog, and b) named Balzac Billy

#this province is a joke in so many ways but at least this joke is fucking hysterical#groundhog day#b posts

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

MORTIMER ADLER’S READING LIST (PART 2)

Reading list from “How To Read a Book” by Mortimer Adler (1972 edition).

Alexander Pope: Essay on Criticism; Rape of the Lock; Essay on Man

Charles de Secondat, baron de Montesquieu: Persian Letters; Spirit of Laws

Voltaire: Letters on the English; Candide; Philosophical Dictionary

Henry Fielding: Joseph Andrews; Tom Jones

Samuel Johnson: The Vanity of Human Wishes; Dictionary; Rasselas; The Lives of the Poets

David Hume: Treatise on Human Nature; Essays Moral and Political; An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

Jean-Jacques Rousseau: On the Origin of Inequality; On the Political Economy; Emile, The Social Contract

Laurence Sterne: Tristram Shandy; A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy

Adam Smith: The Theory of Moral Sentiments; The Wealth of Nations

Immanuel Kant: Critique of Pure Reason; Fundamental Principles of the Metaphysics of Morals; Critique of Practical Reason; The Science of Right; Critique of Judgment; Perpetual Peace

Edward Gibbon: The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire; Autobiography

James Boswell: Journal; Life of Samuel Johnson, Ll.D.

Antoine Laurent Lavoisier: Traité Élémentaire de Chimie (Elements of Chemistry)

Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison: Federalist Papers

Jeremy Bentham: Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation; Theory of Fictions

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Faust; Poetry and Truth

Jean Baptiste Joseph Fourier: Analytical Theory of Heat

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: Phenomenology of Spirit; Philosophy of Right; Lectures on the Philosophy of History

William Wordsworth: Poems

Samuel Taylor Coleridge: Poems; Biographia Literaria

Jane Austen: Pride and Prejudice; Emma

Carl von Clausewitz: On War

Stendhal: The Red and the Black; The Charterhouse of Parma; On Love

Lord Byron: Don Juan

Arthur Schopenhauer: Studies in Pessimism

Michael Faraday: Chemical History of a Candle; Experimental Researches in Electricity

Charles Lyell: Principles of Geology

Auguste Comte: The Positive Philosophy

Honore de Balzac: Père Goriot; Eugenie Grandet

Ralph Waldo Emerson: Representative Men; Essays; Journal

Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Scarlet Letter

Alexis de Tocqueville: Democracy in America

John Stuart Mill: A System of Logic; On Liberty; Representative Government; Utilitarianism; The Subjection of Women; Autobiography

Charles Darwin: The Origin of Species; The Descent of Man; Autobiography

Charles Dickens: Pickwick Papers; David Copperfield; Hard Times

Claude Bernard: Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine

Henry David Thoreau: Civil Disobedience; Walden

Karl Marx: Capital; Communist Manifesto

George Eliot: Adam Bede; Middlemarch

Herman Melville: Moby-Dick; Billy Budd

Fyodor Dostoevsky: Crime and Punishment; The Idiot; The Brothers Karamazov

Gustave Flaubert: Madame Bovary; Three Stories

Henrik Ibsen: Plays

Leo Tolstoy: War and Peace; Anna Karenina; What is Art?; Twenty-Three Tales

Mark Twain: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn; The Mysterious Stranger

William James: The Principles of Psychology; The Varieties of Religious Experience; Pragmatism; Essays in Radical Empiricism

Henry James: The American; ‘The Ambassadors

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche: Thus Spoke Zarathustra; Beyond Good and Evil; The Genealogy of Morals; The Will to Power

Jules Henri Poincare: Science and Hypothesis; Science and Method

Sigmund Freud: The Interpretation of Dreams; Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis; Civilization and Its Discontents; New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis

George Bernard Shaw: Plays and Prefaces

Max Planck: Origin and Development of the Quantum Theory; Where Is Science Going?; Scientific Autobiography

Henri Bergson: Time and Free Will; Matter and Memory; Creative Evolution; The Two Sources of Morality and Religion

John Dewey: How We Think; Democracy and Education; Experience and Nature; Logic; the Theory of Inquiry

Alfred North Whitehead: An Introduction to Mathematics; Science and the Modern World; The Aims of Education and Other Essays; Adventures of Ideas

George Santayana: The Life of Reason; Skepticism and Animal Faith; Persons and Places

Lenin: The State and Revolution

Marcel Proust: Remembrance of Things Past

Bertrand Russell: The Problems of Philosophy; The Analysis of Mind; An Inquiry into Meaning and Truth; Human Knowledge, Its Scope and Limits

Thomas Mann: The Magic Mountain; Joseph and His Brothers

Albert Einstein: The Meaning of Relativity; On the Method of Theoretical Physics; The Evolution of Physics

James Joyce: ‘The Dead’ in Dubliners; A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man; Ulysses

Jacques Maritain: Art and Scholasticism; The Degrees of Knowledge; The Rights of Man and Natural Law; True Humanism

Franz Kafka: The Trial; The Castle

Arnold J. Toynbee: A Study of History; Civilization on Trial

Jean Paul Sartre: Nausea; No Exit; Being and Nothingness

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn: The First Circle; The Cancer Ward

Source: mortimer-adlers-reading-list

#reading list#long post#mortimer adler#text#saved posts#works#books#so much to read#philosophy#literature#dark academia#light academia

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

i tried to get a decent mix of american and canadian groundhogs on this poll. there're also one or two "alternative groundhogs" on this poll too i think. whether or not they count is up to you

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

If you were to teach a lesson in a creative writing course, what advice would you offer to help writers differentiate literature from stories that seem primed for adaptation into film and television, or from the prevalent cinematic writing style that's hard to avoid? How does a writer encourage a reader to choose books over screens?

I believe you touched upon this in a previous discussion, possibly in reference to your hopes for Major Arcana. I also have a vague recollection of a piece by James Wood on Flaubert, where he highlighted how Flaubert pioneered a particular style of descriptive writing that veered away from traditional literature and leaned more towards the visual. My memory on this is a bit hazy, though.

Yes, in Wood's "Half Against Flaubert" (in The Broken Estate) he criticizes Flaubert for developing of style of pregnantly chosen visual detail that easily coarsens into mannerism (in literary fiction) or formula (in pulp fiction) and that looks forward to film.

I don't think fiction needs to be wholly purified of the cinematic or the dramatic. The novel is always generically impure; trying to purify it can lead to tediously programmatic avant-gardism (cf. the gradual subtraction of the entirety of the world over the course of Beckett's oeuvre). But it can do many things unavailable to cinema and should generally be doing at least one of these:

—fiction can depend for its effect on the style, voice, or character of the narrator as much as or more than even what the narrator describes (novel as performance of voice: Huckleberry Finn, True Grit; novel as unreliable narration: Ishiguro's early books; novel as both: Lolita)

—fiction can compress, telescope, summarize, and therefore proliferate tales beyond what visual media can usually accomplish (Balzac, Kafka, Borges, Singer, Bolaño)

—fiction can dramatize the inner workings of subjectivity and consciousness (Ulysses, Mrs. Dalloway, Herzog, A Single Man, Beloved)

—fiction can be discursive or essayistic, in narrative or in dialogue, and therefore convey many more ideas than visual media can (novel as essay or analysis: The Scarlet Letter, Billy Budd, Death in Venice; novel as Platonic dialogue: Dostoevsky, Mann, Lawrence, Murdoch)

—fiction can encompass every type of verbal media into a stylistic collage that takes on much of the culture or creates an air of authenticity or provokes parodic humor (Dracula, Ulysses, Pale Fire, Possession, Cloud Atlas)

—fiction can offer, even in the midst of visual description, all the pleasures of language itself, whether figuration (metaphor, metonymy) or sound (alliteration, rhythm, even rhyme), and can even be a pure exercise of verbal style (early Joyce, Hemingway, Faulkner, Bellow, Didion, McCarthy, DeLillo)

It's probably at this point less about competing with screens—a lot of people now read on screens anyway—than about setting up feedback loops between screen cultures and literary cultures: for example, what we're doing here.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bro.... the groundhog they use for groundhog day in alberta's name is Balzac Billy..... they couldnt have chosen another town that wasn't fucking Balzac????

1 note

·

View note

Text

True Love Quotes

True love is selfless. It is prepared to sacrifice.- Sadhu Vaswani

Rare as is true love, true friendship is rarer.- Jean de La Fontaine

Life is a game and true love is a trophy.- Rufus Wainwright

True love stories never have endings.- Richard Bach

True love lasts forever.- Anonim

Love has no age, no limit; and no death.- John Galsworthy

True love bears all, endures all and triumphs!- Dada Vaswani

True love of a true friend will open your eyes, mind, and heart to a better more fulfilling life.- Anonim

True love is like ghosts, which everyone talks about and few have seen. - Francois de La Rochefoucauld

Only true love can fuel the hard work that awaits you.- Tom Freston

We loved with a love that was more than love.- Edgar Allan Poe

The course of true love never did run smooth.- William Shakespeare

People confuse ego, lust, insecurity with true love.- Simon Cowell

Love isn't something you find. Love is something that finds you.- Loretta Young

Nothing can bring a real sense of security into the home except true love." - Billy Graham

True love doesn't come to you it has to be inside you.- Julia Roberts

True love is eternal, infinite and always like itself. It is equal and pure and is always young in the heart.- Honore de Balzac

True love brings up everything - you're allowing a mirror to be held up to you daily.- Jennifer Aniston

I'm looking for the unexplainable connection and spark - real, true love.- Rachel Lindsay

True love is quiescent, except in the nascent moments of true humility.- Bryant H. McGill

True Love Quotes in English

0 notes

Text

I thought it might interest some of you to know that the province I live in has it's own weather-predicting groundhog, and that not only is it just a dude in a costume, but it's name is Balzac Billy.

Like a large rodent isn't the best method of predicting weather to begin with, but this is somehow worse.

143 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I need everyone to know that this is both a USAmerican and Canadian tradition, just so we aren’t singling them out nor lumping Canadians in as “American,” and also that this is not limited to one singular mythical groundhog.

In Canada, our main groundhog is arguably Wiarton Willie:

But there are several other notable mystical hogs of the ground, such as:

(And yes, these are all from the Actual Weather Network, because I assume this is the most exciting time of year for them. Like with NORAD and their Santa Tracker.)

However… these visions of weather forecasting are not limited to just living groundhogs.

(Source: groundhog-day.com )

There are ‘alternative’ groundhogs, most of which are taxidermy groundhogs, but some of which are things like Manitoba Merv, who is a Groundhog golf club cover:

…Balzac Billy, a mildly disconcerting gopher mascot costume that no furry would be caught wearing:

…And my personal favourite…

🦞 LUCY THE LOBSTER 🦞

A lobster in a hat.

…so anyways, the point of this is it’s not just immortal rodents that will outlive their children not gifted with the curse of immortality, we have given the job of annual spring prognostication to various species of animal and several inanimate objects. This is because a prolonged winter drives one to the point of utter madness where one begins enacting annual rituals with animals and/or animal effigies hoping that will somehow make the fucking snow go away.

(whispers conspiratorially) In America they think rodents predict the weather

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

sir is not happy with punxsutawney phil’s prediction

#rip fred la marmotte#groundhog day#punxsutawney phil#wiarton willie#fred la marmotte#shubenacadie sam#staten island chuck#balzac billy#buckeye chuck#milltown mel#general beauregard lee#stormy marmot#woodstock willie

0 notes

Text

are you a punxsutawney phil or a balzac billy fan

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Subtle, feat. Matthew Tkachuk

Warnings: Smut, Jealousy, Edging, Rough sex

Length: 3.1k

Inspiration: I was actually inspired by a line in @jasonmorgan96‘s Meet The Parents with Vince Dunn. I almost used Vince for this fic, but Matthew fit much better.

To say your boyfriend hated your neighbor was an understatement.

A major understatement

Like, a wow understatement.

But you couldn’t really blame him. They were exact opposites. While your apartment neighbor, Will, was clean and put together, Matthew was wild and untamed. Whereas Will had has hair clean cut and slicked back, Matthew let his curls run wild. Will strutted around in J. Crew and Banana Republic, Matthew lived in sweatpants and ath-leisure. The differences went on for ages.

But the biggest difference was that you were dating Matthew and not Will. And this was a difference Will seemed unwilling to accept.

See, you and Will were a lot alike: Academic, intellectual, scholarly types that didn’t take up a lot of room in front. Your boyfriend, on the other hand, was a loud, in your face, take up all the air in the room type of man. And you adored him for it. Your totally contrasting personalities fit together like two pieces of a puzzle. While you brought peace and serenity to his life, he brought intensity and fire to yours.

It was this intensity and fire you felt in your belly that Friday night, his fingers digging into your hips, his hips strong against yours, his teeth sharp on your throat. You giggled as you both stumbled into the elevator of your apartment building, his strength enough to keep you both from falling to the floor. Pulling his head up, you took his mouth in a kiss that quickly turned hot as he took control. The two of you collapsed back against the wall of the elevator, mouths still fused. It was when you felt his calloused hand pulling your floor-length dress up your thigh that you dragged yourself away.

“No, no, no. No, sir. We were late for the last event. We will not be late for this one.”

Matthew only hummed in feigned compliance as you wiggled out of his grip and leaned forward to press the lobby button on the control panel. You barely made the reach, as he still had his hands firmly on your hips, which were cradled back into his own.

“They’ll understand. Especially when they see you in this dress,” he purred against the shell of your ear. You rolled your eyes. “Of course they’ll understand. They’ll understand so well I’ll hear about it for the next two weeks.” You could practically hear Matthew beaming with pride behind you.

Before the elevator doors could close, a hand shot out from the hallway and they parted again. You immediately felt Matt stiffen behind you, his hands tightening on your hips as Will slid into the elevator, his eyes narrowed judgmentally. Since you believed in keeping peace with your neighbors, you cleared your throat and smiled cordially.

“Hi, Will.”

“Y/N. Where are you headed this evening?”

“Oh, the Flames are having an event.”

“Again?”

“Yes, they have quite a few.”

“How...humanitarian of them.”

Jesus.

A few months ago, Will would have been your type. But since you started dating someone as open and unashamed as Matthew, you could better see a guy like Will for what he really was: condescending, judgmental, entitled. He never missed a chance to remind you that he thought you could do “better.” Though he never said this in as many words.

You should come to this new cafe with me. I’m sure you’re long due for a stimulating conversation.

While I can’t push a puck around, I can read Shakespeare and Balzac.

No amount of money or fame can replace a college education.

Jackass.

You replied before Matthew got a chance. “Yes, I certainly like to think so. They love to give back. What are athletes without the people who support them? Oh, here’s the lobby. Have a good night, Will.”

Lacing your fingers through Matt’s, you all but dragged him out of the elevator toward the front door. He fell easily into step next to you, your fingers still laced together. “You should let me beat him up in the parking garage one day.”

You let out a very unladylike bark of a laugh and brought his hand up to kiss him on the knuckles. He responded with a kiss to the crown of your head and a not so subtle squeeze of your ass as you made your way to his waiting car.

By then end of the night, your boyfriend had you dying for him. Soft, teasing touches under the table, deep kisses snuck when no one was watching, and filthy words of promise whispered in your ear made you so on edge you were dragging him out the door by the end of the night. His hand rested dangerously high on your leg the entire ride back to your apartment, his fingers only just brushing the seam of your thigh. You fidgeted desperately, trying to pull his hand where you needed it, but he wouldn’t give in.

As soon as you were alone in the elevator he was on you, his hands shoving your dress up so he could grip your thighs and hoist you up between his body and the wall. You grunted when your back met the metal, but it was muffled by his mouth over yours. The kiss was deep and wild, everything you had been holding back the entire night. It was everything that was Matthew. The ding of the elevator at your floor had you pulling apart reluctantly. As you stumbled out of the elevator you ran right into Will rummaging through his satchel at the door to his apartment. He looked up, eyes narrowing at your unkempt appearances.

“Oh, hi, Will. How was your night?”

“It was good, thank you. Very productive. How was your night?”

“It was great.”

“Yes I can see that.”

Before you could reply, Matthew opened his big fat hockey mouth. “And it’s going to get a lot fuckin’ better. Good night, Billy.”

With that, he pulled your key out of your hand, deftly unlocked your door, and dragged you inside.

“Very subtle, Matthew,” you scolded him drily, hoping your voice relayed at least some displeasure at his childish behavior. Unfortunately, his hands at your waist and mouth at your neck were making it difficult to hold your ground.

“Wasn’t trying to be subtle, princess,” he murmured against your ear, his chest rumbling against your back as he squeezed your hips and guided you toward the bedroom. You groaned as his lips moved from your ear down your throat to nip at your shoulder. His hands were also roaming, skimming up your sides to tug at the back zipper of your dress.

“Actually,” he continued. “I don’t want to be subtle for the rest of the night.”

“Wha-”

You yelped as he twisted you around and shoved you not ungently onto your back on the bed. He was stunning as he towered over you, eyes hooded in the darkness of the room.

“I want you to be loud tonight. Can you do that for me?”

Unable to deny him anything, you wordlessly nodded, still speechless at the sheer sight of this man that was yours.

“Hmm, good girl.” With that, he dropped to his knees, hooked his arms beneath your legs, and dragged you to the side of the bed. Shoving your dress to your waist, he buried his face between your legs. The sudden heat and pressure of his mouth made you cry out and buck against the feel. Collapsing back, you arched into the touch. He hadn’t taken off your panties, and it was torture to feel the pressure of his tongue against you, but not inside of you.

Pleading his name, you shoved your hands through his curls, both pulling him closer and pushing him away as the pleasure built. When he finally pulled your panties aside and curled two fingers inside of you, his name was a sharp cry, your back arching off the bed. Just as you were about to tip over the edge, he pulled away.

“Not yet, princess. It will be so good when I let you come. So fucking good, baby.”

Whimpering, you reached for him, but he was shoving your hands away and grabbing at the neckline of your dress. He ripped it off in one quick motion, having unzipped it a few moments before. Your panties came with it and you were bare to his eyes. When you reached forward again, he let you make quick work of his own clothes, his hands just as urgent as yours as you tore open his shirt and shoved aside his dress pants.

As he stood naked before you, cock hard against his stomach, you couldn’t help yourself. Moving to the edge of the bed, you wrapped your arms around his waist and laid kiss after kiss over his chest, nipping here and there with your teeth, worshipping him. His hands were in your hair, pushing you closer as a loud moan of your name left his throat. You could imagine his face: head tipped back, tendons strong against his throat as his eyes fluttered shut and his mouth opened in pleasure.

You felt his cock twitch against the skin of your chest and his hand was suddenly at your neck and shoving you down onto the bed. You felt his grip on your throat trael between your legs and you nearly came, but his voice was pulling you away again.

“Not yet, baby. You come with me inside you.”

Before you could object, he was moving over you, a knee coming to the side of your head, the other coming up beneath your arm and under your shoulder. One of his hands had fisted his cock. “Suck me off, princess.”

You did as you were told, greedily accepting his cock in your mouth. He groaned long and loud, his body pitching forward until he had to catch himself with one hand against the bed. You ran your nails up his thighs to his hips, digging them in hard as you took him as far back as you could. This drew a long, strangled moan from his chest and you whimpered in need. His other hand went to the back of your head, digging a strong grip into your hair and forcing your head forward.

The pace was rough and desperate as he fucked into your mouth, his hips snapping forward until he was hitting the back of your throat at every stroke. You welcomed him every time, giving him complete control to take whatever pleasure he wanted from you. You could only hold on, let his hold on your head dominate every movement you made. Words of filthy encouragement dripped from his mouth and you opened your mouth wide as you felt his cock twitch.

But before he came down your throat, he was yanking your head back and pulling away yet again. You collapsed back onto the bed, gasping for breath. Before you could raise your head or even open your eyes, you felt the heat of his tongue lick a long path up your pussy. Groaning out his name, you thrust your hands through his hair in welcome. But he was gone again the next second, the strength of your hands incomparable to his.

“Do you have any idea how fucking gorgeous you are like this?” He purred against the mound of your pussy before laying a gentle kiss there. “So fucking wet and wrecked for me. God, such a slut for me.” You could only whimper in reply as he kissed his way slowly back up your body. Your pussy throbbed at the soft brush of his cock, but it was gone again in the next breath.

His next words were murmured against your throat. “Who does this to you, baby? Who makes you this fucking wet?”

It took a long moment to find them, but your words left you on a rush of breath. “You-you do, M-Mathew.”

He hummed in approval against your throat before taking your mouth in a rough tangle of a kiss. You groaned again and collapsed back against the bed, wrapping your legs tight around his hips. No matter what he did, how far he pushed you, the pleasure he dragged screaming from your body, his kiss felt like sanctuary every time. The two of you stayed like that for a long moment, relishing the warm intimacy of the kiss before he was flexing his hips and biting hard at your bottom lip. You yelped in pain, but then squealed in surprise when you were suddenly moving off the bed and through the air.

Your back met the headboard so hard you grunted. Matthew’s body was hot and hard against yours, pressing you back until you could feel the tension of his muscles with every deep breath you took. You leaned forward to kiss him again, but he clapped his hand over your throat and shoved you back against the headboard.

“Matt...”

His hand gripped your hip and lifted your body up slightly. You gasped against his mouth as he pushed just the tip of his cock into you. Your pussy clenched reflexively, but he was pulling out again to the sound of your strangled sob.

“What do you need, princess?” he growled against your lips. “Tell me what you need.”

“Matthew, please. I can’t-”

You yelped again as he slapped your ass hard. “Tell me.”

You struggled to find words as he pushed in slowly again, only slightly deeper than before. You both inhaled at the pleasure, bodies moving as one.

“You, Matthew. I need you. Please. Please-”

He pulled out again, but was quick to push back again, his own need reaching a breaking point.

“What do you need? Tell me exactly what you need, baby.”

“I need to come, Matthew. I need you to come inside of me. Please. Please.”

He chucked against your mouth, shameless in his knowledge of your desperation.

“Whatever you want, princess. But be loud for me. Scream my name fucking loud.”

As he pulled out and slammed in to the hilt, you did just that, screaming out louder than you ever had before. His hands flew up and one of them manacled your own wrists to the headboard, dragging your body up until you had to sacrifice all control. His other hand went to the top edge of the headboard and held on tight. With every thrust against you, he slammed the headboard back against the wall.

Let that little prick hear whose name you screamed. Let him hear every slam of that headboard until he couldn’t think of anything else when he so much as saw you.

Your orgasm was shattering when you finally came, more powerful than any you had had before in your life. Your body sagged in his grip, but Matthew wasn’t done. He pounded into you until he reached his own climax, pulling out and thrusting in so deep you could feel him in your throat.

When he let go of your hands and let his own body relax, you sagged against him, collapsing as you struggled to catch your breath. He held you gently, murmuring praise into your ear as he stroked your hair.

When you finally regained some composure, you laid a hot, wet kiss to his throat, a silent thank you for the pleasure. He groaned and tilted his head to the side in compliance. When you felt his cock twitch in renewed interest, you flexed tight around him.

HIs next words came only after a strangled groan. “Not yet, baby. You did so good for me. We’re going to rest a bit.”

Before you could argue, he wrapped an arm tight around your waist and moved you both to lay down with your heads against the pillows, his cock still inside you. Your bodies more than enough heat without the blankets, you snuggled into him and let out a small noise of content and drifted off to sleep.

He woke you up twice more that night, dragging you on top to ride him and then putting you on your knees, head shoved into the pillows as he pounded into you from behind. The next morning, you could barely move, grimacing as you pulled yourself into an upright position.

“You okay?” Matthew’s voice was tired and raspy. You looked down at him and your heart fluttered like a teenage girl’s. He was beautiful next to you, unashamedly naked and taking up every inch of air in the room. You also didn’t miss the glint of concern in his eyes. Not being able to help yourself, you leaned down and pecked him on the mouth. “Yes,” you reassured him. “But you need to feed me.”

He grinned against your mouth and pulled his own body up and out of bed. You couldn’t help but glare at his retreating form as he sauntered to the bathroom. He was used to throwing his body around like a wrecking ball. You were not. You were going to feel last night for at least a week.

As you began to get ready to go out for breakfast, you caught a glimpse of the wall behind your headboard. You squawked in anger and disbelief as you took in the state of your wall.

“Matthew!”

He poked his curly head out from the hallway, his toothbrush hanging out of his mouth.

“What?”

“Look at my wall! It’s fucking dented!”

The cocky bastard didn’t even try to look ashamed. He looked unbelievably proud of himself. “We did good, babe.”

Grabbing the closet object - an UGG slipper on the floor - you lobbed it at his head. Of course, he ducked back into the bathroom just in time.

“You’re paying my security deposit,” you hollered over your shoulder as you stomped to the other bathroom.

When the two of you made it out of your apartment, who should you run into but Will. Who did not look happy. He got one glimpse of the two of you and his jaw set in an angry, judgmental line.

“Good morning,” he greeted you frostily.

“Mornin’,” Matthew replied, a wide smirk on his face.

You felt your own face flush a deep red. God, the two of you had been loud last night. And Will lived in the apartment right next to your bedroom wall. If you were rough enough to dent the wall, you were loud enough to keep him awake.

As Matthew was about to say something else, the three of you turned your heads as a tiny old lady hobbled out of the apartment. You and Matthew both stood in stunned silence.

“This if my widowed grandmother,” Will explained with a tight voice and a frosty glare. “She stayed with me last night.”

You gaped and looked up at Matthew, who had turned a concerning shade of white.

The little old lady took you both in before her face broke out in a big brilliant smile. She reached out and patted your cheek. “Good for you, sweetheart!”

Subtle.

#Matthew Tkachuk#Matthew Tkachuk smut#Matthew Tkachuk imagine#nhl imagine#nhl smut#nhl fic#smut#imagine#my work#hockey-hoe-24-7

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Season 1 Gilmore Girls References (Breakdown)

Yay! All the season 1 references have been posted. Before I start posting season 2, I wanted to post this little breakdown for your enjoyment :) It starts with some statistics and then below the cut is a list of all the specific references.

Overall amount of references in season 1: 605

Top 10 Most Common References: NSYNC (5), Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory (5), Taylor Hanson (6), Leo Tolstoy (7), Lucky Spencer (7), Marcel Proust (7), PJ Harvey (7), The Bangles (8), The Donna Reed Show (8), William Shakespeare (10)

Which episodes had the most references: #1 is That Damn Donna Reed with 55 references. #2 is Christopher Returns with 44 references

What characters made the most references (Only including characters/actors who were in the opening credits): Lorelai had the most with 237 references, Rory had second most with 118, and Lane had third most with 48.

First reference of the season: Jack Kerouac referenced by Lorelai

Final reference of the season: Adolf Eichmann referenced by Michel

Movies/TV Shows/Episodes/Characters, Commercials, Cartoons/Cartoon Characters, Plays, Documentaries:

9 1/2 Weeks, Alex Stone, Alfalfa, An Affair To Remember, A Streetcar Named Desire, Attack Of The Fifty Foot Woman, Avon Commercials, Bambi, Beethoven, Boogie Nights, Cabaret, Casablanca, Charlie's Angels, Charlie Brown cartoons, Christine, Cinderella, Citizen Kane, Daisy Duke, Damien Thorn, Dawson Leery, Donna Stone, Double Indemnity, Double Mint Commercials, Ethel Mertz, Everest, Felix Unger, Fiddler On The Roof, Footloose, Freaky Friday, Fred Mertz, Gaslight, General Hospital, G.I. Jane, Gone With The Wind, Grease, Hamlet, Heathers, Hee Haw, House On Haunted Hill, Ice Castles, I Love Lucy, Iron Chef, Ishtar, Jeff Stone, Joanie Loves Chachi, John Shaft, Lady And The Tramp, Life With Judy Garland: Me And My Shadows, Love Story, Lucky Spencer, Lucy Raises Chickens, Lucy Ricardo, Lucy Van Pelt, Macbeth, Magnolia, Mary Stone, Mask, Midnight Express, Misery, Norman Bates, Officer Krupke, Oompa Loompas, Old Yeller, Oscar Madison, Out Of Africa, Patton, Pepe Le Pew, Peyton Place, Pink Ladies, Pinky Tuscadero, Ponyboy, Psycho, Queen Of Outer Space, Rapunzel, Richard III, Ricky Ricardo, Rocky Dennis, Romeo And Juliet, Rosemary's Baby, Sandy Olsson, Saved By The Bell, Saving Private Ryan, Schindler's List, Schroeder, Sesame Street, Seven Brides For Seven Brothers, Sex And The City, Sixteen Candles, Sleeping Beauty, Star Trek, Stanley Kowalski, Stella Kowalski, Stretch Cunningham, The Champ, The Comedy Of Errors, The Crucible, The Donna Reed Show, The Duke's Of Hazzard, The Fly, The Great Santini, The Little Match Girl, The Matrix, The Miracle Worker, The Oprah Winfrey Show, The Outsiders, The Shining, The Sixth Sense, The View, The Waltons, The Way We Were, The Scarecrow, This Old House, V.I.P., Valley Of The Dolls, Vulcans, Wild Kingdom, Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory, Wheel Of Fortune, Who's Afraid Of Virginia Woolf, Working Girl, Yogi Bear, You're A Good Man Charlie Brown

Bands, Songs, CDs:

98 Degrees, Air Supply, Apple Venus Volume 2, Backstreet Boys, Bee Gees, Black Sabbath, Blue Man Group, Blur, Bon Jovi, Boston, Bush, Duran Duran, Everlong, Foo Fighters, Fugazi, Grandaddy, Hanson, I'm Too Sexy, Joy Division, Jumpin' Jack Flash, Kraftwerk, Like A Virgin, Livin La Vida Loca, Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds, Man I Feel Like A Woman, Metallica, Money Money, My Ding-A-Ling, NSYNC, On The Good Ship Lollipop, Pink Moon, Queen, Rancid, Sergeant Pepper, Shake Your Bon Bon, Siouxsie And The Banshees, Sister Sledge, Smoke On The Water, Steely Dan, Suppertime, Tambourine Man, The B-52s, The Bangles, The Beatles, The Best Of Blondie, The Cranberries, The Cure, The Offspring, The Sugarplastic, The Wallflowers, The Velvet Underground, Walk Like An Egyptian, XTC, Ya Got Trouble, Young Marble Giants

Books/Book Characters, Comic Books/Comic Book Characters, Comic Strips:

A Mencken Chrestomathy, A Tale Of Two Cities, Anna Karenina, Belle Watling, Boo Radley, Carrie, David Copperfield, Dick Tracy, Dopey (One of the seven dwarfs) Goofus And Gallant, Great Expectations, Grinch, Hannibal Lecter, Hansel And Gretel, Harry Potter (book as well as character referenced), Huckleberry Finn, Little Dorrit, Madame Bovary, Moby Dick, Mommie Dearest, Moose Mason, Nancy Drew, Out Of Africa, Pinocchio, Swann's Way, The Amityville Horror, The Art Of Fiction, The Bell Jar, The Grapes Of Wrath, The Hunchback Of Notre Dame, The Lost Weekend, The Metamorphosis, The Portable Dorothy Parker, The Unabridged Journals Of Sylvia Plath, The Witch Tree Symbol, There's A Certain Slant Of Light, Tuesdays With Morrie, War And Peace, Wonder Woman

Public Figures:

Adolf Eichmann, Alfred Hitchcock, Angelina Jolie, Anna Nicole Smith, Annie Oakley, Antonio Banderas, Arthur Miller, Artie Shaw, Barbara Hutton, Barbara Stanwyck, Barbra Streisand, Beck, Ben Jonson, Benito Mussolini, Billy Bob Thornton, Billy Crudup, Bob Barker, Brad Pitt, Britney Spears, Catherine The Great, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Charles I, Charles Dickens, Charles Manson, Charlie Parker, Charlotte Bronte, Charlton Heston, Charo, Cher, Cheryl Ladd, Chris Penn, Christiane Amanpour, Christopher Marlowe, Chuck Berry, Claudine Longet, Cleopatra, Cokie Roberts, Courtney Love, Dalai Lama, Damon Albarn, Dante Alighieri, David Mamet, Donna Reed, Edith Wharton, Edna O'Brien, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Elizabeth Webber, Elle Macpherson, Elsa Klensch, Elvis, Emeril Lagasse, Emily Dickinson, Emily Post, Eminem, Emma Goldman, Errol Flynn, Fabio, Farrah Fawcett, Fawn Hall, Flo Jo, Francis Bacon, Frank Sinatra, Franz Kafka, Fred MacMurray, Friedrich Nietzsche, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Gene Hackman, Gene Wilder, George Clooney, George Sand, George W. Bush, Harry Houdini, Harvey Fierstein, Henny Youngman, Henry David Thoreau, Henry James, Henry VIII, Herman Melville, Homer, Honore De Balzac, Howard Cosell, Hugh Grant, Hunter Thompson, Jack Kerouac, Jaclyn Smith, James Dean, Jane Austen, Jean-Paul Sartre, Jennifer Lopez, Jessica Tandy, Jim Carey, Jim Morrison, Jimmy Hoffa, Joan Of Arc, Joan Rivers, Jocelyn Wildenstein, Joel Grey, John Cage, John Gardner, John Muir, John Paul II, John Webster, Johnny Cash, Johnny Depp, Joseph Merrick AKA Elephant Man, Judy Blume, Judy Garland, Julian Lennon, Justin Timberlake, Karen Blixen AKA Isak Dinesen, Kate Jackson, Kathy Bates, Kevin Bacon, Kreskin, Lee Harvey Oswald, Leo Tolstoy, Leopold and Loeb, Lewis Carroll, Linda McCartney, Liz Phair, Liza Minnelli, Lou Reed, M Night Shyamalan, Macy Gray, Madonna, Marcel Marceau, Marcel Proust, Margot Kidder, Marie Antoinette, Marie Curie, Marilyn Monroe, Mark Twain, Mark Wahlberg, Marlin Perkins, Martha Stewart, Martha Washington, Martin Luther, Mary Kay Letourneau, Maurice Chevalier, Melissa Rivers, Meryl Streep, Michael Crichton, Michael Douglas, Michelle Pfeiffer, Miguel De Cervantes, Miss Manners, Mozart, Nancy Kerrigan, Nancy Walker, Nick Cave, Nick Drake, Nico, Oliver North, Oprah Winfrey, Oscar Levant, Pat Benatar, Paul McCartney, Peter III Of Russia, Peter Frampton, Philip Glass, PJ Harvey, Prince, Queen Elizabeth I, Regis, Richard Simmons, Rick James, Ricky Martin, Robert Duvall, Robert Redford, Robert Smith, Robin Leach, Rosie O'Donnell, Ru Paul, Ruth Gordon, Samuel Barber, Sarah Duchess Of York, Sean Lennon, Sean Penn, Shania Twain, Shelley Hack, Sigmund Freud, Squeaky Fromme, Stephen King, Steven Tyler, Susan Faludi, Susanna Hoffs, Tanya Roberts, Taylor Hanson, Theodore Kaczynski AKA The Unabomber, The Kennedy Family, Groucho, Harpo, Chico, Zeppo, and Gummo Marx AKA The Marx Brothers, Venus and Serena Williams (The reference was "The Williams Sisters"),Thelonious Monk, Tiger Woods, Tito Puente, Tom Waits, Tony Randall, Tonya Harding, Vaclav Havel, Vanna White, Vivien Leigh, Walt Whitman, William Shakespeare, William Shatner, Yoko Ono, Zsa Zsa Gabor

Misc:

Camelot, Chernobyl Disaster, Cone Of Silence, Hindenburg Disaster, Iran-Contra Affair, Paul Bunyan, The Menendez Murders, Tribbles, Vulcan Death Grip, Whoville, Winchester Mystery House

#gilmore girls#gilmore girls references#season 1 references#reference breakdown#nsync#willy wonka & the chocolate factory#taylor hanson#leo tolstoy#lucky spencer#marcel proust#pj harvey#the bangles#the donna reed show#william shakespeare#lorelai gilmore#rory gilmore#michel gerard#lane kim#lane kim van gerbig#jack kerouac#lauren graham#alexis bledel#keiko agena#yanic truesdale

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

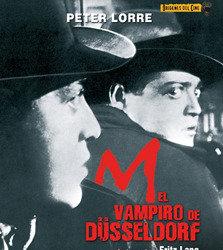

¿POR QUÉ CINE NEGRO?

¿FUE ESTA LA PRIMERA?

¿O FUE ESTA?

EL HALCÓN MALTÉS

PERDICIÓN

EL SUEÑO ETERNO

EL TERCER HOMBRE

LA JUNGLA DEL ASFALTO

LAUREN

HUMPHREY

LAURA

SED DE MAL

FORAJIDOS

RETORNO AL PASADO

ATRACO PERFECTO

A veces los nombres de los movimientos artísticos tienen un origen no muy bien definido. En el caso del cine, el término CINE NEGRO tiene un origen dudoso como ocurre con términos artísticos como RENACIMIENTO o BARROCO.

La palabra Renacimiento no tiene un origen claro. Por una parte, hay quien responsabiliza al artista Giorgio Vasari en pleno siglo XVI la alusión al renacer de la cultura clásica tras la Edad Media por lo que utilizó la palabra Rinascita. (En arquitectura, en pleno siglo XVI se denominaba a las construcciones renacentistas como de estilo “a la romana”). Sin embargo, la mayoría de los autores opinan que fue Balzac quien utilizó la palabra Renacimiento por primera vez en su novela Le Bal de Sceau en 1829 y que ya era un término que se usaba en los círculos intelectuales. Por su parte la palabra Barroco también es de dudoso origen, aunque existe cierto consenso en por atribuirla al idioma portugués, más exactamente a la palabra Barocco que significa “perla irregular con deformaciones”.

En el caso del cine nos encontramos con un género cinematográfico denominado Cine Negro cuyo origen también se ha señalado como dudoso. Está claro que tiene un origen literario: la novela policial, pero sin embargo nadie ha calificado al género cinematográfico como Cine Policial. Es cierto que en los años 20 del siglo pasado aparecieron una serie de novelas con el calificativo de Serie Negra; de ahí al cine solo había un paso y pronto a las películas que podían encuadrarse en este género se les comenzó a etiquetar como Cine Negro.

Pero ¿quién usó por primera vez este término?: tampoco hay un acuerdo unánime, aunque parece que fue el crítico italiano Nino Frank el que utilizó el nombre film noire. El éxito de la denominación fue absoluto hasta el punto de que ese nombre fue asumido por Hollywood tras la II Guerra Mundial. Pero para ello el género literario adquirió una gran calidad en base a unos talentos creativos que han perdurado con el tiempo no ya como guionistas cinematográficos sino como auténticos maestros de este tipo de literatura. Así tenemos que citar entre los m��s conocidos a Dashiel Hammett, Raymond Chandler, William Riley Burnett, Jim Thompson, John Hadley Chase, Steve Fisher y especialmente para mí, a James M. Cain.

Por lo tanto y por extraño que nos parezca, el término procede de la literatura y no propiamente del cine y además tiene su origen, no en el lugar donde se desarrolló con más éxito y calidad artística este género, sino en la vieja Europa (aunque sería injusto no señalar la gran aportación europea al género con películas de grandes directores, especialmente franceses, como Claude Chabrol, Jean Pierre Melville, Louis Malle o Jean Luc Godard).

Pero ¿cuáles son las características esenciales que identifican el cine negro? Pues de nuevo no se puede hablar en términos absolutos, pero si hay acuerdo en algunos elementos técnicos y argumentales que pueden definirse como propios de este género:

1. Hay consenso generalizado en que el origen cinematográfico se debe buscar en el expresionismo alemán, un movimiento caracterizado por la existencia de luces y sombras y posiciones de la cámara (picados, contrapicados y angulaciones) que otorgan una atmósfera de dramatismo a la historia. Este movimiento surgió alrededor de 1920 y debemos citar El gabinete del doctor Caligari, Metrópolis o El Golem como algunas de sus películas esenciales. Un elemento destaca por encima de todo en estas películas: están realizadas lógicamente por su fecha de producción en Blanco y Negro (B/N). Esta va a ser también una característica del cine negro, al menos esencialmente en su época dorada: desde los años 30 hasta finales de los 50 del siglo pasado. No obstante, en años posteriores aparecieron numerosas películas de calidad que se pueden integrar en este género y realizadas ya en color. (De todas formas, es curioso cómo grandes creadores, cuando han abordado el cine negro en años recientes recuperan el B/N para su producción: es el caso de los Hermanos Coen cuando realizaron El hombre que nunca estuvo allí).

2. Otra característica más o menos general es el rol que asumen los personajes masculinos y femeninos en este género. Los masculinos se dividen entre los propios criminales y esencialmente los protagonistas, que conforman un perfil de “perdedores” con moral algo ambigua. Los máximos representantes de estos antihéroes son Sam Spade y Phil Marlowe, creaciones de dos de los grandes autores de este género: Dashiel Hammett y Raymond Chandler y que curiosamente fueron interpretados por un mismo y mítico actor: Humphrey Bogart. El cine negro supuso también la aparición de la mujer en un nuevo rol. Se pasó de una mujer débil e indefensa salvada por el héroe, a una mujer independiente y capaz de convertirse en asesina; en definitiva, aparece en el cine la representación de la femme fatale con ejemplos en personajes de Lana Turner, Lauren Bacall o Barbara Stanwick

3. La tercera característica es que el argumento incluya la denuncia, la crítica social, señalando la corrupción policial o el mal funcionamiento del sistema (este aspecto argumental estaba más claramente expresado en sus orígenes literarios, mientras que en el cine las críticas al sistema se dulcificaron en parte por miedo a la censura).

4. Por último, un elemento esencial de estas historias es la violencia. Evidentemente remarcar la violencia en el cine negro de sus años dorados puede resultar un inocente ejercicio cuando en las últimas décadas la violencia explicita ocupa en gran parte toda película que se precie de contar una historia criminal (Tarantino nos presentó una violencia cínica y explicita cercana al gore y Lars Von Trier en La casa de Jack muestra una violencia extrema y provocadora). De cualquier forma, sigo pensando que, como decía Wilder respecto a su maestro en relación al sexo: “Lubisth enseña más con una puerta medio cerrada que los directores de hoy día con una bragueta abierta” o ¿es que la presencia de abundantísima sangre y larga escenas de tortura y crueldad puede superar a la violencia final de M, la violenta angustia de La noche del cazador o a la de La dama de Sanghai?

De forma más o menos general todos los críticos e historiadores coinciden en que el Cine Negro es un género que tuvo su mayor desarrollo en Estados Unidos entre 1930 y 1950. Pero todo es relativo en términos artísticos y hay quien considera que ya en 1903 se realizó la primera película de ese género: Asalto y robo al tren de Edwin S. Porter. Pero ¿qué película podemos citar como realmente la primera de ese género? Tampoco existe un acuerdo. Algunos historiadores sostienen que hay varias películas anteriores a la IIGM que pueden ostentar ese título de ser la primera ya que, sí por otra parte, varios creadores de ese género eran de origen alemán y huyeron a Estados Unidos cuando los nazis llegaron al poder, es normal que se identifiquen varias películas de su obra europea como cine negro. Se suele citar El desconocido del tercer piso (1940) de un también desconocido Boris Ingster como la primera, pero asimismo pueden ostentar ese galardón tres films anteriores de Fritz Lang: M (1931), Furia (1936) o Solo se vive una vez (1937).

¿Y cuando puede deducirse que tiene su finalización el género?: en un sentido estricto podríamos decir que no ha finalizado, aunque se tiene a Sed de mal de 1958 como la película que cierra brillantemente este género. ¿No hay cine negro posterior a estas fechas? Para la gran mayoría de críticos no, en todo caso hay un cine que podríamos denominar como policial, pero con alusiones de algún tipo al cine negro. De esta forma tendríamos que incluir a películas como Taxi Driver o A quemarropa en esta clasificación y directores como los Coen, Tarantino o De Palma como realizadores de películas con estas características mixtas. Personalmente creo que es una discusión gratuita pues el tiempo ha ido enmarcando cada obra en su correspondiente clasificación de género.

Derivada de la palabra thrill (emoción, estremecimiento) se ha generalizado el término thriller para designar un tipo de cine policial muy amplio, desde películas de suspense, hasta terror psicológico. Creo que se podrían etiquetar como THRILLER a las películas que se pudieran incluir como encasilladas en el cine negro pero que han sido producidas posteriormente a 1958 y generalmente en color, mientras que el término CINE NEGRO lo podríamos restringir a las realizadas en el periodo clásico de ese género, desde la década de los 30 hasta finales de los 50 del siglo pasado.

Por último, voy a señalar las que, bajo mi criterio, pueden ocupar los puestos más destacados en una supuesta lista de LAS MEJORES PELÍCULAS DE CINE NEGRO (lógicamente me olvido de algunas y entre otras, muchas de aquella modesta serie B que nos dejó grandes películas):

-M (Fritz Lang, 1931)

-Furia (Fritz Lang, 1936)

-Solo se vive una vez (Fritz Lang, 1937)

-El halcón maltés (John Huston, 1941)

-Perdición (Billy Wilder, 1944)

-Laura (Otto Preminger, 1944)

-La mujer del cuadro (Fritz Lang, 1944)

-Historia de un detective (Edward Dmytryk, 1944)

-Perversidad (Fritz Lang, 1945)

-Alma en suplicio (Michael Curtiz, 1945)

-El sueño eterno (Howard Hawks, 1946)

-El cartero siempre llama dos veces (Tay Garnett, 1946)

-Gilda (Charles Vidor, 1946)

-La dalia azul (George Marshall, 1946)

-Forajidos (Robert Siodmak, 1946)

-Retorno al pasado (Jacques Tourneur, 1946)

-La senda tenebrosa (Delmer Daves, 1946)

-Cayo Largo (John Huston, 1948)

- La dama de Sanghai (Orson Welles, 1948)

-El abrazo de la muerte (Robert Siodmak, 1949)

-Al rojo vivo (Raoul Walsh, 1949)

-El tercer hombre (Carol Reed, 1949)

-El crepúsculo de los dioses (Billy Wilder, 1950)

-La jungla del asfalto (John Huston, 1950)

-Extraños en un tren (Alfred Hitchcock, 1951)

-Cara de ángel (Otto Preminger, 1951)

-Los sobornados (Fritz Lang, 1951)

-La noche del cazador (Charles Laughton, 1951)

-Atraco perfecto (Stanley Kubrick, 1951)

-Sed de mal (Orson Welles, 1958)

-Vértigo (Alfred Hitchcock, 1958)

Volver a ver cualquiera de ellas supone una auténtica delicia cinematográfica.

17/1/2021

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Florida Project, Sean Baker, 2017 (unfinished review: March 15th, 4.32am)

À la recherche d’un film m’aidant à forger ma personnalité, suis-je retombée sur une recommendation soutenue par mon amoureux, un film que j’aimerais, The Florida Project.

Des fragments précieux de vie d’une jeune mère et sa fille Moonee vivant dans la galère au sein d’un motel de Floride. On y suit les amitiés de Moonee, virevoltant dans une enfance non-conventionnelle, où règne toutefois l’amour.

Essentiellement, dans toute sa cradeur cette œuvre célèbre la vie, en ses joyeux petits fragments ridicules. C’est très certainement ce vif contraste entre l’aspect pastel, très léger d’une enfance insouciante; et la réalité sociale dans laquelle Haley présente en elle tous les vices antithétiques au propre d’une maman, qui offre un reflet de la vie comme le socle de toute chose, galères et euphorie. Cet aspect presque dérangeant est mis en scène parfaitement lorsque Moonee appelle Haley “maman”, revenant d’une agression physique initiée sur sa voisine devant son propre fils. Brutal, presque viscéral, on y suit la diversité d’états bruts dans lesquels se trouvent nos protagonistes, tous enfants.

En outre, à la manière de Jacqueline Wilson, Sean Baker nous livre un doux récit où au-delà du manque de sous, l’amitié et l’amour maternel parviennent à égayer des enfances naviguant le monde des grands.

Parfaitement reflété par un décor coloré, parfaitement cadré, Baker nous donne l’impression d’un monde enfantin, protégé par Billy, qui fait figure de père. Bien qu’apparemment échouant à sa propre famille, le manager du motel se présente comme un affectueux médiateur entre deux mondes, celui de l’enfance, et de l’adulte responsable. En outre, c’est cette négation des responsabilités qui offre à Haley ce côté libérateur - bien que chaotique - soutenu à merveille par la fluidité des mondes dans lesquels évoluent nos trois gosses Moonee, Scooty et Jancey.

Impolis, Moonee et Scooty libèrent Jancey de sa rigueur maternelle, pour explorer le monde dans la quête primale d’amusements. On les voit s’y amuser à tout prix avec rien, le temps d’un été. Haley se trimballe sa gosse à droite à gauche, construire un salaire pour payer les factures, et ainsi ne se soumettant pas aux impératifs du 9-5 auquelle elle n’est visiblement pas adéquate. Il s’agit dans son creux, d’une pièce sur la famille, celle qui nous éduque, et celle qu’on choisit. Dans l’ambition finale de faire comprendre à l'auditeur que la vie rééelle est à trouver dans ses imperfections, dans la hess “You know why it’s my favorite movie? Cause it’s tipped over and still growing”.

Le réalisme de cette fantaisie en décalage avec le fantaisiste parc Disney Universal voisin, présente la double-face à tout, à la manière d’un roman de Balzac adapté en son temps moderne et lieu américain,.

Le confort réside en l’amour solidaire, ami et/ou famille. (trop fatiguée: jeu sur l’enfance dérouté (maturité, sensibilité, large définition de l’enfance, limitevicieux d’avoir de la sympathie pour Haley car on est rendus sensible à son amour imature pour sa fille)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Writing Report March 26, 2021

The first draft of my big (formerly) work in progress clocks in at 104,599.

I tend to write long and shaggy, repeating information, spelling things out in great detail, etc., etc., and of course, etc.

Final draft target length will be in the 80K range, but it’s not simply a matter of whacking stuff out.

I’ve come up with several scenes and bits of business I want to add. Draft two will incorporate them and try to make an appreciable dent in the word count, but the real paring down will be in the polish.

I differentiate between drafts and polishes this way:

The first draft gets the story laid out so I can see all the component parts.

The second draft works on those parts, rearranging them / trimming them / eliminating some.

The polish takes the final form and sands down the rough edges, slaps a smooth finish on it, and sends it out into the cold, cruel world.

For me, there shouldn’t be a third draft of the story.

You need your basics laid out in the first draft, the final structure in the second.

If you’re still facing structural problems in the third draft…well, to paraphrase Billy Wilder, the problem was in the first draft.

(This is not to say I haven’t written stories that have run into third drafts, just not third complete drafts. I can usually tell long before I finish draft one that it isn’t working and will abandon that approach and restart the effort from a different direction; call that one draft one-B. I have a story where it took me over two decades and two abortive false starts before I figured out the correct angle of approach and eventually I will write it now that I’ve figured out what the problem is.)

I forget which writer said it (Voltaire? Honore de Balzac? I seem to remember it being a French author), but there’s a quote about a writer needing to tell the story three times:

First to tell it to yourself.

Then to discover what the story is really about.

Finally to figure out how to tell it to the reader.

I’m taking about a six week break from my first draft to work on some other projects, then will dive into re-reading / re-editing / re-writing what I need to for the second draft.

God willin’ an’ th’ crick don’t rise, I hope to have it ready by the end of summer.

© Buzz Dixon

1 note

·

View note