#Béla Kun

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Béla Kun circa 1903

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

România la un Pas de Prăbușire în 1915!

Tensiuni la Granițe, Uneltiri Bolșevice și Pericole Necunoscute: Cum România a Evitat o Catastrofă Anul 1915 nu părea să fie unul extraordinar pentru Regatul României, dar realitatea era alta. Țara se afla într-un moment critic, înconjurată de imperii rivale și cu un teritoriu încă incomplet. Cu un an înainte ca România să intre în Primul Război Mondial, țara era o insulă într-o mare de tensiuni…

View On WordPress

#1915#Aliați#Austro-Ungaria#Basarabia#Béla Kun#bolșevici#Bucovina#Budapesta#Cârlibaba#CBCRO#Cristian Rakovski#CrossBorderChroniclesRo#Ion I.C. Brătianu#Polonia#Primul Război Mondial#Republica Sovietică Ungară#România#Rusia#Tighina#Transilvania#Ungaria#Zbigniew Dunin-Wąsowicz#Zigmunt Zielinski

1 note

·

View note

Photo

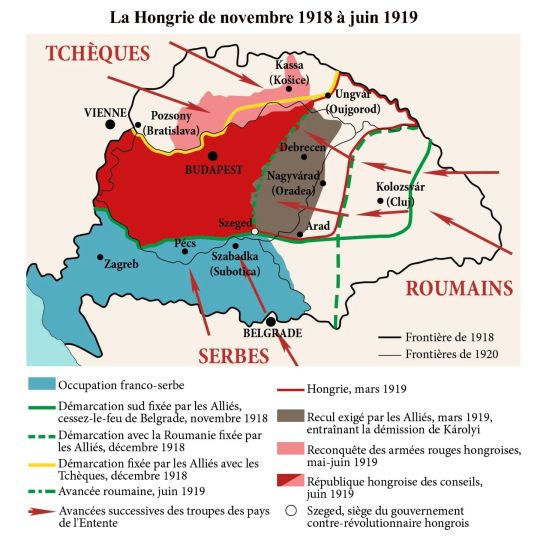

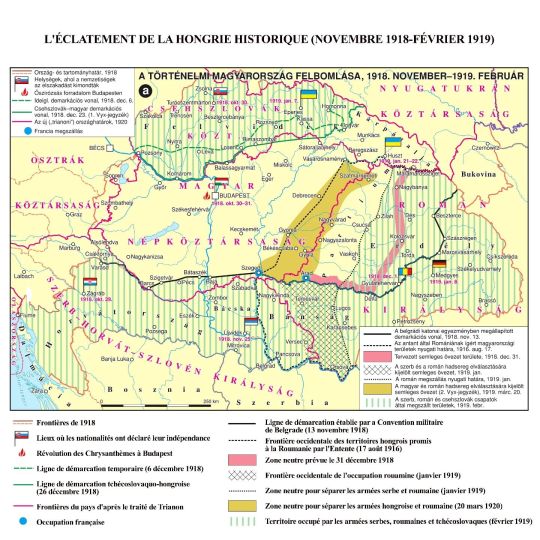

Hungary in 1918-1919

Nicolas de Lamberterie, 2020

"Történelmi atlasz - Középiskolásoknak", József Kaposi, 2016

by cartesdhistoire

Defeats on the front, rising prices, and the agitation of foreign peoples created a troubled situation in Hungary, and in January 1918, a general strike paralyzed activity in Budapest. At the instigation of certain former Hungarian prisoners freed from Russia by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and converted to Bolshevism, mutinies took place, and a new general strike of a political nature extended to the entire country on June 20.

On the night of October 29 to 30, Count Mihály Károlyi became the head of government of a de facto independent Hungary: it was the Aster Revolution which established the Hungarian Democratic Republic (November 16).

The head of the inter-allied military mission, the Frenchman Fernand Vix, demanded a retreat of the Hungarian armies by 100 km, an ultimatum which led to the fall of Károlyi and the formation of a government in the hands of the journalist Béla Kun, who had returned from Russia where he had been a companion of Lenin: the Hungarian Soviet Republic was proclaimed on March 21. To face the armed offensives of its neighbors, the government formed a People's Army which, after some successes against the Czechs, was defeated by the Romanians who advanced on Budapest. Béla Kun left the capital on August 1, two days before the arrival of Romanian and Serbian troops supported by French forces (missions led by Berthelot and Franchet d'Espèrey, respectively).

The Bolsheviks' rise to power was poorly received in the provinces and among the Allies. In the southeast of the country occupied by French troops, a national government was formed in June in Szeged whose army was entrusted to Admiral Horthy who, at the time of Béla Kun's fall, already controlled the entire South and West of the country. After negotiating the departure of the Romanians with the Entente, Horthy entered Budapest at the head of his army on November 16. The assembly elected him regent of Hungary on March 1, 1920.

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stratégiai nyugalom Nemzeti értékrend Nekünk ebből a háborúból ki kell maradni Magyarérdek! Családérdek! Sorosterv! Fürkészünk és portyázunk! Hátha leesik valami a kamionról Rezsigázkőolaj Hol a faszban a dílerem! Béke! Béke! Béke! A magyar nép katonanép Keresztény értékekkel! Sohasem fogom kimosni a számból Lavrovot… Hol a picsában lehet ebben a szaros városban koxot szerezni? Just one fix! Kereszténydemokrácia A Geccnek persze könnyű Ő legálban tolja Rivotrilra páleszt Putyin békepapagája Mikor lesz már ennek vége? Hogy kerültem ebbe a majomketrecbe? Hazám, hazám, te mindenem! Baszki bogarak mászkálnak a bőröm alatt!!!! Csak az a döglődő Putyin meg ne nyomja Azt a piros gombot Akkor fölöslegesen építettem magamnak futsalpályát Baszki Kun Béla, Rákosi és Kádár nyomdokain Moszkvába járunk faszt szopni Ezek a genya ukránok miért nem adják meg magukat?!!! Fogadják vendégszeretően az orosz felszabadítókat Széttárt combokkal és pucsító seggel Mint az én őseim 1848, 1945, 1956 magasságában Just one fix Where is the exit? Békeharc!!! Békeharc! Nem gyenge bástya Hanem erős rés vagyunk Az EU várfalán! Just one fix!

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

És ti tudtátok, hogy Szent István útját Dobrev Klára járja elsősorban? Gondolom Kun Béla is ezen az ösvényen poroszkált!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ma azon töprengtem, hogy micsoda mulasztás az, hogy egy csomó kisebb köztéri izét még nem neveztek el híres magyarokról.

Pl. lehetne:

- wass albert villanypózna (nagyfeszültségű szakaszolóval)

- kun béla körzeti transzformátor-állomás

- csurka istván szennyvíz-átemelő

- gr. klebersberg kunó metrószellőző

- "németh lászlóné" gázfogadó

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

2001 Budapest, mémorial de Béla Kun au Memento Park

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

On this All Hallows' Eve I recall an old leftist article from an italian site.

The characters are:

Dracula comunista

Commissario del Popolo per gli Affari esteri Béla Kun

aristocratico István Bethlen

sanguinario ammiraglio Miklós Horthy

Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau

Boris Karloff

#tag yourself

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“If we are intended for great ends, we are called to great hazards.” –His Eminence, St. John Henry Cardinal Newman

Laudetur Jesus Christus! On this day in 1971, His Eminence, Venerable József Cardinal Mindszenty (1892 - 1975), Archbishop of Esztergom and Prince-Primate of Hungary, was released from exile, bringing an end to his fifteen-year political asylum in the United States Embassy in Budapest.

Born in Csehimindszent, Austria-Hungary, and ordained a priest in 1915, Mindszenty was a prolific writer who penned many texts in defense of traditional motherhood and the family, and he was an ardent defender of the Habsburg claim to the throne; accordingly, he vehemently opposed the socialist government of Mihály Károlyi, the communist government of Béla Kun, and the Arrow Cross Party, all three of which arrested him for his Catholicism during his life.

Having been made Bishop of Veszprém in 1944 and then Archbishop of Esztergom and Prince-Primate of Hungary the following year after the collapse of the Kingdom of Hungary, Mindszenty was elevated to the rank of Cardinal in 1946 by His Holiness, Pope Venerable Pius XII, who told him that, “Among these thirty-two [new Cardinals], you will be the first to suffer the martyrdom symbolized by this red color.” True to this prophecy, His Eminence was persecuted by the ruling Hungarian Working People’s Party, which regarded Mindszenty as a “clerical reactionary” harboring “aristocratic attitudes” in light of his refusal to give up his royal titles and his refusal to comply with the Party’s abolition of private farm ownership and Catholic religious orders.

Arrested in 1948 for treason and conspiracy to restore the Habsburg Monarchy, Mindszenty was repeatedly tortured and then convicted in a “show trial” whose perpetrators were excommunicated by Pius XII. Following his predetermined conviction, Mindszenty was tortured in prison for seven years until, in 1956, he was liberated by Catholic insurgents during the Hungarian Revolution and taken to the United States Embassy in Budapest, where he was confined for the next fifteen years in order that he would not be arrested by the invading Soviet Army.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Ha a Szikra mozgalom hozza magával a nemzetközi antifa-kapcsolatait, a Párbeszéd pedig becsatornázza az Extinction Rebellion meg a Fridays for Future forrófejű fiataljait, kész is az új tanácsköztársaság erőszakos magja. Szabó Tímea lesz az új Kun Béla!

Persze, csináljanak forradalmat, csak ne járjon túl nagy zajjal, mert akkor valagba rugdosom őket

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Savage Béla Kun to y'all 💅🏻

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

From the article;

Hungary: supporter of 1919 revolution

Lugosi supported the Hungarian Communist Party, which was founded in December 1918, and its leader, Béla Kun. Following the example of revolutionary Russia, a mass uprising overthrew the old regime beholden to the ruling class. The Hungarian Soviet Republic was founded on March 21, 1919.

While the Red Flag of the fledgling republic waved over the parliament building for only 133 days, Kun’s government introduced the first legal protections for ethnic minorities, the 8-hour workday and higher national wages.

Lugosi led a demonstration of actors in March 1919 and emerged as a high-profile organizer. He was instrumental in founding the Free Organization of Theatrical Employees, which later expanded into the first film actors union in the world, the National Trade Union of Actors.

Don Rhodes wrote in “Lugosi: His Life in Films, on Stage and in the Hearts of Horror Lovers” that “Lugosi helped combine the Free Organization of Theater Employees and members of the film industry in the National Trade Union of Actors, and acted as its general secretary.”

The NTUA’s first statutory congress began on April 17, 1919. Lugosi’s speech included the words: “Half a year ago, I launched the struggle with the decision that the national trade union of socialist actors should be established.”

#he was exiled for his support of the Hungarian Revolution#and also spoke out numerous times against the Horthy gov and Hungarys alliance with nazi ger#articles a good read

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

1956 – Ki a gyilkos?

Most már minden rendben van.

Most már minden rendben lesz.

Gyurcsány elvtárs és Hiller elvtárs 1956 után született, és bár a Kun Béla, Rákosi Mátyás és Kádár János kommunista pártjának összeharácsolt vagyonából és politikai tőkéjéből szervezett utódpárt (Kommunisták Magyarországi Pártja, Magyar Kommunista Párt, Magyar Dolgozók Pártja, Magyar Szocialista Munkáspárt, Magyar Szocialista Párt) oszlopos tagjai, büszkén vallják, hogy nekik semmi közük elődeik, elvtársaik, szellemi atyáik tetteihez, aljasságához, bűneihez. Horn Gyula nem köphette szembe pufajkás elvtársait, Gyurcsány és Hiller elvtársak ezt már emelt fővel, büszkén megteszik.

Ők már nem kommunisták. Ha egyáltalán valaha azok voltak, azt már rég elárulták, megtagadták, elfelejtették. Ők már szociáldemokraták.

Látványnak sem utolsó: egy magyar szociáldemokrata milliárdos a szocialista pártkongresszuson teli torokkal harsogja – Föl, föl, ti rabjai a földnek! – a proletár nemzetköziség himnuszát, az Internacionálét. (Mondják: Gyurcsány nem énekelte, mert a kongresszus végén, amikor elvtársai dalolni kezdtek, kisomfordált a teremből. Látványnak ez talán még szebb!)

Gyurcsány Ferenc nagyon kimódolt bevonulásakor a Magyar Állami Operaházba, először kezet fogott a Himnuszt éneklő fogyatékos férfival, majd barátságosnak gondolt, kegyúri gesztussal többeket megsimogatott, ezt követően emelkedett szellemű emlékbeszéddel ünnepelte a forradalmat, a forradalom hőseit és mártírjait. Nagy Imrét például. Azt a Nagy Imrét, aki ezzel a mondattal búcsúzott az élettől: „Csak attól félek, hogy azok fognak majd rehabilitálni, akik most meggyilkolnak.”

Nagy Imre régi kommunista volt. Kalapban, karján esernyővel ott állt magányosan 1956. október 6-án a Kerepesi temetőben, amikor az elvtársai által meggyilkolt Rajk László és társai újratemetésekor Apró Antal elvtárs azt harsogta: Soha többé! Lehet, hogy Nagy Imre már ott, a temetőben gyanította: egy kommunista fogadkozása, bocsánatkérése, ígérete semmit sem ér. De azt akkor még nem sejthette, hogy Kádár elvtárs másfél év múlva „ellenforradalmi bűneiért” őt ítélteti el és küldi bitófára.

1958 tavaszán már tudta: gyilkosai fogják majd rehabilitálni őt.

Így is történt.

De hát Gyurcsány Ferenc még nem élt, amikor hajdani elvtársai – gondolom, KISZ KB-titkár korában még elvtársának tekintette Kádár elvtársat – meggyilkolták elvtársukat, Nagy Imrét. A milliárdos úrrá vedlett Gyurcsány elvtárs úgy gondolja: neki semmi köze nincs ahhoz a hajdani gyilkossághoz. Ellenkezőleg! A megbékélés jegyében mártírnak kijáró tisztelettel övezi Nagy Imre és a forradalom emlékét, és – Horn Gyula ezt nem tehette meg – szociáldemokrata úriemberként Gyurcsány elvtárs készül a kommunisták összes gaztettéért Kádár Jánost megtenni egyedüli bűnbaknak. Nincs új a nap alatt: Kádár János szerint az ötvenes években nem a kommunista diktatúra tette tönkre az országot, csupán a Rákosi–Gerő-klikk szektás- dogmatikus politizálása. Kádárból magányos gyilkost kreálni, Nagy Imréből ballib prófétát faragni, a Magyar Szocialista Pártot szociáldemokrata párttá átmázolni tisztességtelen, de okos taktikai lépés, mert akkor Gyurcsány Ferenc nyugodtan megkoszorúzhatja Nagy Imre sírját, hiszen annak halálakor nem is élt, így könnyű szívvel elfelejtheti hajdani elvtársát, Kádár Jánost, akiért KISZ-titkár korában még lelkesedett.

Ha Gyurcsány Ferenc becsületes kommunista volt, akkor most erkölcstelen politikus. Ha csak színlelte hajdan, hogy kommunista, akkor most erkölcstelen milliárdos.

Ahogy jó másfél száz éve a bölcs dán filozófus, Søren Kierkegaard mondta: Vagy-vagy.

Öreg tollforgatóként üzenem 2004 őszén Gyurcsány Ferencnek, Magyarország miniszterelnökének: okos ember csatát nyer, becsületes ember háborút. A becsületes ember gyakran csatát veszít, a becstelen soha nem nyer háborút. És ha akad a miniszterelnök úrnak bokros teendői közepette egy szabad félórája, ajánlom figyelmébe Lukács evangéliumát. Különösen a 11. rész 47. versét:„Jaj néktek! mert ti építitek a próféták sírjait; a ti atyáitok pedig megölték őket.”

(Keserű utóirat: Véletlenül került kezembe egy közel negyvenéves meghívókártya. 1966. október 23-án a budavári Fortuna étterembe fogadásra invitálta az amerikai Time című hetilap kiadója a magyar értelmiség és művészvilág néhány kiválóságát, közöttük Latinovits Zoltánt. Véletlenül éppen 1966. október 23-ra, a forradalom tízéves évfordulóján. Ma már nem tudni, mi történt aznap este a Fortuna étteremben. Nem tudom, miről beszélgettek a meghívott magyar művészek és értelmiségiek az amerikai üzletemberekkel, szerkesztőkkel, újságírókkal. Mertek őszintén beszélni? Politizáltak? Vagy mindenki tudta: t��z évvel ezelőtt ezen a napon robbant ki a magyar forradalom, s ők most azért beszélgetnek és poharazgatnak itt, mert szavak nélkül, de együtt akarnak emlékezni a letiport, meggyilkolt forradalomra, szabadságharcra és az elesett, kivégzett áldozatokra.

Jó lenne tudni, mi történt a Fortuna étteremben 1966. október 23-án. Egy biztos: akik ott voltak, emelkedett lélekkel emlékeztek a forradalomra, a szabadságharcra, a halottakra.

Rég volt.

A Pesti Műsorban megjelent hirdetést böngészem: „Nosztalgiavonattal a Csabai kolbászfesztiválra 2004. október 23-án.”

Hát itt tartunk, miniszterelnök úr! Kolbászfesztivál október 23-án, nosztalgiavonattal. Főzőcskézünk, eszegetünk, iszogatunk, jól élünk a megbékélés jegyében.

Nem tudom, ki szervezte a kolbászfesztivált. Nem tudom, melyik pártnak a tagja vagy híve az az ostoba ember, akinek agyából kipattant ez az idióta ötlet. De az biztos, hogy – jobb- vagy baloldali politikai meggyőződésétől függetlenül – nem tudja, mit jelent magyarnak lenni, nincs köze történelmünkhöz, erkölcsi érzéke egyenlő a semmivel. Ráadásul még emberi mértékkel mérhető ízlése sincs.

Rettegve gondolok arra, mit fognak kiötleni lelkes hazámfiai 2006. október 23-án, hogy nemzeti ünnepünkön felhőtlenül s boldogan mulasson a nép, kacagva és zabálva felejtse el történelmét, múltját, nemzeti értékeit, erkölcsi értékrendjét.)

Szigethy Gábor

0 notes

Text

El Evangelio según Lukács

Por Claudio Mutti

Traducción de Juan Gabriel Caro Rivera

György Lukács, alias Georg Löwinger (1885-1971), desempeño funciones gubernamentales en dos breves y distintos momentos de su existencia: en 1919, en la época de la llamada «República de los Consejos» presidida por Béla Kun, cuando fue Comisario del Pueblo para la Educación, además de comisario político de la Quinta División Roja; después, en 1956, cuando, como miembro del Círculo Petöfi y del Comité Central del Partido Comunista, fue Ministro de Educación en el primer gobierno de Nagy.

Sin embargo, su intervención más incisiva, más violenta y más devastadora en la vida cultural húngara tuvo lugar en el bienio democrático 1945-1946, cuando regresó a Hungría y fue diputado y miembro de la dirección de la Academia de Ciencias, así como profesor de estética y filosofía de la cultura en la Universidad de Budapest. El vástago del banquero József Löwinger se convirtió entonces en «un verdadero director de conciencias, un dictador espiritual, un dictador relativamente liberal cuya palabra era ley. (...) Era la prueba viviente de la tolerancia del régimen hacia las mentes más sutiles» (1). Otro famoso «judío errante» (2) nacido en Hungría (primero marxista, luego católico y finalmente, por supuesto, liberal) lo describe en estos términos casi idílicos: Ferenc Fischel, alias François Fejtö, fundador con Raymond Aron del Comité de Intelectuales por una Europa de las Libertades. El concepto de libertad de Fischel-Fejtö puede deducirse de lo que escribe sobre la acción político-cultural de György Löwinger-Lukács; según él, «quería hacer del Partido Comunista el mecenas y protector de todas las actividades culturales, un centro de acopio para llevar a cabo las grandes reformas: democratización y modernización de la enseñanza, ampliación de las bases de la cultura, emancipación del espíritu. Era la época del pluralismo y del “diálogo”» (3).

Ante una apología tan sentida, uno se queda sencillamente estupefacto, si se piensa que el «pluralista» Lukács fue el consejero más autorizado de la comisión encargada de compilar el Catálogo de la prensa fascista y antidemocrática, un auténtico Index librorum prohibitorum que se dividió en tres partes publicados entre 1945 y 1946 en varias ediciones por el Departamento de Prensa de la Oficina del Primer Ministro. En aquella época gobernaba una coalición de mayoría centrista, presidida por un clérigo que pertenecía al Partido de los Pequeños Propietarios.

El Catálogo nació del mismo espíritu inquisitorial que unos años más tarde produciría el infame libro de Lukács Die Zerstörung der Vernunft (El asalto a la razón), pero tenía una función eminentemente práctica: señalaba a las autoridades policiales los textos que debían ser requisados en librerías y bibliotecas privadas para ser enviados a la industria de la pasta y el papel, en aplicación del Decreto 530 emitido el 28 de abril de 1945 por el gobierno del General Béla Miklós (el Sumo Sacerdote húngaro), un decreto relativo a la «prensa fascista y antidemocrática». En las bibliotecas públicas, los libros indexados debían trasladarse a departamentos especiales, no accesibles a los lectores ordinarios.

El Catálogo (más de 160 páginas en total) enumera por orden alfabético libros y revistas, folletos y partituras, incluso carteles de propaganda y octavillas impresos en las dos últimas décadas. No se trata sólo de textos húngaros, sino también de ediciones alemanas, italianas, francesas, inglesas y españolas, que tuvieron cierta difusión en Hungría en el periodo de entreguerras.

Entre las obras del índice, además por supuesto de los Protocolos de los sabios de Sión y toda la literatura sobre la cuestión judía, figuran los escritos de Hitler y Mussolini, Joseph Goebbels y Alfred Rosenberg, Pavolini y Farinacci, así como del líder crucificado Ferenc Szálasi. Pero también hay libros de célebres figuras literarias húngaras como József Erdélyi (el poeta nacional-popular ya condenado en la época horthista) o Cecil Tormay (el cuentista que tradujo del italiano a Gabriele d'Annunzio). Entre los autores no húngaros figuran Berdjaev, Céline, Chesterton, Gide, Panait Istrati, Keyserling, Malynski, Maurras, Moeller van den Bruck, Ossendowski, Carl Schmitt, Werner Sombart y Othmar Spann. Entre los italianos, en particular, podemos mencionar a Giuseppe Bottai, Armando Carlini, Ernesto Codignola, Enrico Corradini, Carlo Costamagna, Julius Evola, Arnaldo Fraccaroli, Giovanni Gentile, Balbino Giuliano, Salvator Gotta, Guido Manacorda, Mario Missiroli, Romolo Murri, Alfredo Oriani, Sergio Panunzio, Giovanni Papini, Concetto Pettinato, Giorgio Pini, Giovanni Preziosi, Carlo Scarfoglio, Nino Tripodi y Gioacchino Volpe.

El «plan para ampliar las bases de la cultura» de Lukács incluía también la compilación de la tristemente célebre Lista B, una lista de intelectuales que no eran «políticamente correctos», condenados al silencio y a la muerte civil.

Entre las víctimas más ilustres de la lista de proscritos ideada por Lukács nos gustaría recordar a Béla Hamvas (1897-1968). Sándor Weöres, el Rimbaud magiar, le llamaba «mi maestro»; el filósofo Botond Szathmári le calificaba de «continuador de la tradición platónica». Béla Hamvas, que fue el primero en dar a conocer en Hungría las obras de Guénon y Evola, ha sido señalado en repetidas ocasiones por su parentesco espiritual con los maestros del «tradicionalismo integral»; su obra maestra Scientia Sacra, una gran obra de síntesis que bien podría compararse con libros como La crisis del mundo moderno o Revuelta contra el mundo moderno, merece una mención. Autor prolífico y polifacético, Béla Hamvas reanudó su actividad cultural tras la guerra publicando una antología de la literatura universal, Anthologia Humana, que alcanzó su tercera edición. A continuación, supervisó la publicación de una serie de libros de bolsillo (los «Pequeños Cuadernos de la Tipografía Universitaria») que dieron a conocer al público húngaro no sólo a los presocráticos y neoplatónicos, sino también a autores como Heidegger y Heisenberg, hasta entonces prácticamente desconocidos en el país del Danubio. Pero la serie editada por Hamvas fue prohibida por Lukács, que mandó enviar a al horno los volúmenes ya impresos y ordenó la destrucción de las impresiones. Con diligente escrupulosidad, Lukács también hizo destruir los tomos de un volumen sobre Heidegger que aún no había entrado en imprenta, tras haber tachado ex cathedra al autor de Sein und Zeit de «líder del sombrío existencialismo fascista». Calificado sumariamente (y falsamente) por Lukács como «el más turbio devoto del neomisticismo húngaro», Béla Hamvas fue despedido de la Biblioteca de la Capital, de la que era funcionario, y se vio obligado a ganarse la vida como jornalero agrícola y luego como mozo de un almacén en una empresa de construcción de centrales eléctricas. Pero esto no tenía por qué significar mucho para un hombre que solía decir: «En todas partes hay un Eje».

Volviendo a Lukács, nos parece interesante una sugerencia de Róbert Horváth, que sitúa el origen de la pronunciada vocación de Lukács por el sadismo persecutorio en una especie de devoción religiosa («subreligiosa») invertida e impregnada de un «espíritu» parroquial. Por nuestra parte, hemos encontrado una expresión en uno de los escritos juveniles de Lukács que casi parece anticipar, como una lúcida declaración programática, el ascetismo criminal del futuro inquisidor: «Para salvar el alma��, escribe Lukács, «hay que sacrificar el alma misma: hay que convertirse, partiendo de una ética mística, en un feroz Realpolitiker y violar no una restricción artificial, sino el mandamiento absoluto: “No matarás”» (4). Sic.

De hecho, en la obra de Lukács no faltan elementos que confirmen la indicación de Róbert Horváth. Al contrario, en ella es posible percibir ese contenido «negativamente espiritualista y (...) maléficamente religioso» (5) que según Emmanuel Malynski caracteriza «el llamado materialismo histórico» (6); o más bien, esa marca que Guénon consideraba típica de la «contrainiciación»: una marca claramente visible allí donde se desfigura la imagen de lo sagrado y donde se distorsiona o falsifica el sentido de las doctrinas espirituales. Róbert Horváth se detiene en el caso concreto de la lectura que Lukács hace de Meister Eckhart, pero la investigación podría desarrollarse también en relación con otros maestros espirituales, como Plotino y Proclo, a los que Lukács trató de instrumentalizar junto con Eckhart: y no sólo a lo largo de la fase «juvenil» de su actividad (7), hasta Geschichte und Klassenbewusstsein (8), sino también en los años de la llamada «ortodoxia» (9).

Por otra parte, es más que explícita en Lukács una concepción del marxismo que Guénon habría definido como «contrainiciatica»: «Parece esencial al socialismo – escribe Lukács – esa fuerza religiosa capaz de llenar el alma que distinguía al cristianismo de los orígenes» (10). Tampoco faltan en esta caricatura del cristianismo los aspectos escatológicos y mesiánicos, hasta el punto de que si Marianne Weber ya reconocía en el joven Lukács al «mensajero escatológico» de una nueva era (11), Paolo Manganaro ha podido detenerse más ampliamente en estos rasgos del marxismo de Lukács: «Lukács se adhiere a un modelo de socialismo quiliastico, mítico y religioso (...) Para Lukács es decisivo que la clase mesiánica (la Messiasklasse) haya hecho su entrada en la historia: el presente es así el comienzo, la puerta de la utopía. (...) en Lukács la Kultur está cargada de un elemento místico fácilmente discernible. (...) El primer borrador de ¿Qué es el marxismo ortodoxo? desarrolla una dialéctica mesiánica del “cumplimiento esperado” de la revolución» (12).

Desde que Paul Vulliaud, estudioso de la Cábala hebrea, publicara en 1938 su estudio sobre la «propaganda mística de los comunistas», poco se ha hecho por explorar este tema. Aparte de los trabajos de Richard Wurmbrand, Jacques Bergier, Jean Robin y algunos otros, así como algunos artículos de divulgación propios, las investigaciones más serias y orgánicas sobre la subreligión comunista accesibles al lector italiano son sin duda las de Aleksandr Dughin (13) y Nicola Fumagalli (14). El primero ha puesto de relieve la influencia ejercida por aquella doctrina neoespiritualista que en Rusia recibió el nombre de «cosmismo», mientras que el segundo, basándose en la obra de Giorgio Galli, ha intentado rastrear elementos de origen esotérico en el pensamiento político de la izquierda rusa anterior a 1917. Una exploración del pensamiento de Georg Löwinger-Lukács a la luz de los datos e indicios mencionados podría completar válidamente las escasas nociones que hasta ahora se han recogido sobre las «raíces ocultas» del marxismo y las implicaciones pseudorreligiosas del bolchevismo.

Notas:

1. F. Fejtö, Ungheria 1945-1957, Torino 1957, pp. 122-123.

2. Fejtö Judío errante es el título con el que «Il Giornale» (Milán) del 26 de junio de 1997 publicó una larga entrevista con François Fejtö, también colaborador del mismo periódico.

3. F. Fejtö, op. cit., pp. 30-31.

4. Gy. Lukács, Lettera a Paul Ernst, 4 maggio 1915, rip. en: Gy. Lukács, Schriften zur Ideologie und Politik, Neuwied und Berlin 1967, pp. 10-11 nota. La carta traducida se puede encontrar en: Gy. Lukács, Epistolario 1902-1917, Roma 1983, pp. 359-363.

5. E. Malynski, La guerra occulta, Padova 1989, p. 153.

6. Ibidem.

7. Cfr., ejemplo: Gy. Lukács, Epistolario 1902-1917, cit., pp. 159, 188, 202, 204, 230, 247.

8. Gy. Lukács, Storia e coscienza di classe, Milano 1967, p. 272.

9. Cfr., por ejemplo: Gy. Lukács, Megjegyzések egy irodalmi vitához. Az Uj Magyar kultúráért, Budapest 1948; rist. en: Gy. Lukács, Magyar irodalom – Magyar kultúra, Budapest 1970, p. 453.

10. Gy. Lukács, Esztétikai kultúra, cit. en: István Mészáros, Philosophie des Tertium datur und Coexistenzdialogs, en Festschrift zum 80. Geburstag von Georg Lukács, Neuwied und Berlin 1965.

11. M. Weber, Max Weber. Ein Lebensbild, Tübingen 1925, p. 509.

12. P. Manganaro, Introduzione a: Gy. Lukács, Scritti politici giovanili 1919-1928, Bari 1972, pp. XI-XIX.

13. A. Dughin, Continente Russia, Parma 1991.

14. N. Fumagalli, Cultura politica e cultura esoterica nella sinistra russa (1880-1917), Milano 1996.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The communist oppressive secret police of Hungary, the ÁVH, after WWII would torture male prisoners of the state by jamming thin rods of glass up their penis hole, then punching their dick to break them, filling their urethra with broken glass. The women were raped so violently that the victims would be so desperate to make sure they weren't pregnant with the babies of disgusting Soviets, that they would shove cleaning chemicals up their vaginas to destroy them and make themselves infertile. To force fake confessions, the communists often beat prisoners in the face until they lost all their teeth, including women. Ernő Gerő, one of the communist leaders during the 1956 uprising, called for the open fire on the civilians of Hungary who were planning a public gathering before the riots even began, because how dare they have the audacity to oppose the regime, right? Béla Kun, another communist leader of Hungary, wanted to destroy the Holy Crown of Saint Steven, one of Hungary's most iconic symbols and most beloved historical artifacts. Thank God it's okay and he never did destroy it.

In other words, communism is not just an oppressive force that squanders any semblance of freedom, it also suppresses culture and ethnic identity.

Yes, capitalism is essentially slavery to money, but at least the cops aren't shoving glass rods up your penis.

178 notes

·

View notes