#Ayodhya case

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

M. Siddiq vs Mahant Suresh Das (2019 SCC Online 1440)

This Case Summary is written by Masab Ahmed Maaz, a 3rd-year law student at the University Of Petroleum And Energy Studies, Dehradun SYNOPSIS This case has one of the oldest origins in the history of the Indian legal system and has been in the spotlight of the entire nation for a long time. The case revolves around the religious sentiments of India’s two largest communities and their dispute…

View On WordPress

#Ayodhya case#Ayodhya case judgement#Ayodhya judgement#M. Siddiq vs Mahant Suresh Das#M. Siddiq vs Mahant Suresh Das (2019 SCC Online 1440)#ram mandir

0 notes

Text

On why exit polls were probably broken in Ayodhya

Nobody spoke because of the fear factor. They were worried if they complained over their shop being demolished the authorities will come and demolish their homes too for no reason.

Residents also feared that if they speak they will have to face court cases. Police ka bhaiya (fear of the police) ensured the people did not speak out so nobody reported too about such incidents.

cc @nyomkitten

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

I can’t stress this enough for people who have had their eyes opened with the ongoing genocide of Palestinians who might not be aware of this context: this is a part of that ‘slow buildup that we all should have noticed’, except just like in that case it’s also been going on. It’s not remotely harsh to draw a line in the sand there. Celebrating the Ram temple in ‘Ayodhya’ is simple Hindutva, no matter how common it seems

218 notes

·

View notes

Note

Genuinely curious, because you seem to hate the Ram Mandir... or how you think one party/ruling government is using it for political gain/votes or how it's wasting money etc.

What do you have to say about the Waqf board act? Or the infamous Shah Bano case and the way the Rajiv Gandhi government went against the decision of the Supreme Court to favour Muslim patriarchy. Or the fact that the Congress government banned books like the Satanic Verses to please a certain community. Is this not politics of appeasement?

You say that the ruling party is playing politics over religion, but hasn't every party done it? It's not like BJP was even hiding it, they've been campaigning for the Ram Mandir rebuilding for decades. It doesn't make it automatically a bad move.

Besides, Ram Mandir is built through devotee donations, so why so much vitriol against it? If Hindus are giving money to construct a temple, it's solely their own decision. I genuinely don't understand why there's so much hatred for it. If a community is reclaiming their holy land, which had been forcibly ruined and rebuilt into another type of building, it's not a bad thing. Plus, a big chunk of land was given to the Sunny Waqf board to build a beautiful mosque in Ayodhya itself, which has begun construction this year (iirc). Both communities will have their interests restored.

Why can't we move on and celebrate the Ram Mandir rebuilding and inauguration? Is decolonization and reclaiming of a place of cultural significance not important?

(I know that some people are being too aggressive about it, but the majority isn't. They're simply celebrating and praying. And some of them actually got attacked for it.)

Okay. Since you're genuinely curious, I'll answer this.

"Why am I criticising the current ruling party for playing politics of appeasement and not any of the other parties?" I'm criticizing them BECAUSE they're the ruling party. They have been in power for close to 10 years now. That's more than 1/3rd of my whole life. This is a hilarious question because I would've been criticizing the same action if it would've been taken by any other political party. I don't have a problem with the party, I have a problem with what they're doing. All citizens are SUPPOSED to do this, my friend. Criticizing your government on what they're doing wrong is a fundamental part of a democracy.

"Politics of appeasement." I hope you understand the difference between appeasement and religious nationalism. The ruling party isn't appeasing anyone. Their acts are guided by their political ideology of Hindutva. I fundamentally disagree with their ideology. I do not agree with them when they say being Hindu is integral to being an Indian. I do not believe in maintaining a Hindu hegemony in India. I simply refuse to accept an ideology that was LITERALLY INSPIRED BY FASCISM AND THE IDEAS OF RACIAL SUPERIORITY.

"What do you have to say about so-and-so?" You know, I would've criticised things I believe are harming our country and power when the governments you speak of were in power. Unfortunately, in certain cases I was not alive then to criticize them and in a few cases, I was a child and I did not know how to form complex sentences. I do not believe in essentialism, you understand? I do not believe that any religion or political party is essentially good or bad. I believe in judging them for what they do.

"They've been campaigning for the Ram Mandir for decades. It doesn't make it automatically a bad move." It's imperative for you to understand this, it is politically a good move and in all other ways a HORRIBLE move. They get the support of all the Hindus who make up the majority of the population? Decent political move. Who could begrudge them for using DIVIDE AND CONQUER as a strategy? But in doing so, what kind of monster have they created? Have they created a billion people who think religious-nationalism is an okay direction for the country's future? Is that a good move, I ask you.

"Ram mandir is built through devotee donations so it's okay." That's close to ₹1,800 crores. (Estimated amount because of course, there's no transparency in the donation system so that we know who donated what amount.) Do you seriously believe all that money came out of the pockets of average working class Indians? Or did the ultra wealthy businessmen fund this religious project and get massive tax breaks in the process? But yes, I'm sure there's no fuckery going on with the money because it's out of DEVOTION. That makes it okay, I guess.

Now we come to the part that is the worst part of this anon message, according to me.

"Reclamation and decolonization." You use these words so lightly and I find that offensive. These words are HIGHLY tied to power structures. Who has the power right now? Is it the mythic evil Islamic conquerors of 400 years ago? Or is it a political party that believes in hindu nationalism and is funded by the ultra wealthy billionaires because said party helps them get even richer? Who is reclaiming what here? I want you to ask yourself this. Can a powerful majority claim reclamation when they tear down a building to build another building there?

"They tore down the temple and built a mosque there" And now you've torn down the mosque and built a temple there. Congratulations, you've won the game. Where do we go from here? Will everyone be happy now? Has peace been restored? A great evil destroyed? What story are we telling ourselves here? Will the religious fanaticism go away now? Will the hatred that has been cultivated in the hearts of Hindus against Muslims be sated? Or will it find more avenues to spread itself?

Decolonizing the mind, right? I wonder why we're only focused on decolonizing against the islamic past and not anything else. But it's okay that India is currently colonising Kashmir. We don't believe in decolonisation when it comes to Kashmir. We don't believe in decolonizing from the system of capitalism that is choking the lives out of us. HELL, WE DON'T EVEN BELIEVE IN RECLAMATION SEEING HOW WE HAVE A PROBLEM WITH GIVING THE BARE MINIMUM RESERVATION TO CERTAIN COMMUNITIES AS A REPARATION FOR THE HARM THEY'VE HISTORICALLY AND CURRENTLY SUFFERED AND ARE STILL SUFFERING.

I don't want people to talk to me about reclamation, reparation and decolonisation before they accept their own hypocrisy.

Anon, you say have so much vitriol and hate towards a mandir. I should let people celebrate. Did I stop you personally from celebrating? Did I beat up somebody for trying to shove their religious agenda on me? All I did was talk about how sad I am that this is what we've decided to do with our country's resources. Why is one voice of dissent such a big deal to you? Do you want me to shut up and fall in line? Will that be acceptable?

- Mod S

96 notes

·

View notes

Note

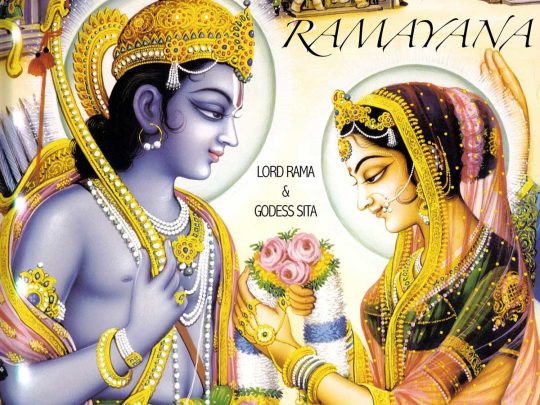

hi, can i request something? i was thinking that we don't get to see rama hearing about sita (who's miraculous birth and deeds must have been stories that spread to ayodhya as well as other kingdoms) before they meet as we do see sita hearing about rama and admiring him in adaptations. so, it would be great if you could write an au on 5 times rama heard about sita and 1 time he told someone about her (maybe luv-kush or hanuman/the vanaras). thank you!

Hello there! Thanks for the ask, this was very interesting to write, and I discovered I have so many opinions and headcanons about a bunch of characters and their relationships I could make a whole entire post out of it. Also, this is a 4k+ monster, so beware :D

1.

“They found her where?”

Rama looks up from his dessert blearily to where Bharata is frowning at their King Father. It is a sweet spring morning, and their family is gathered around the table breaking their fast. Beside his drooping self, Lakshmana bounces restlessly.

“I want the curd,” he whines.

Mother Kaikeyi answers her son as she passes the dish over. “She was buried in the earth, and King Janaka found her under the plough.”

“How was she not mowed down? Do people stare at the ground as they plough? Why did the oxen not trample her? How did she survive in the heat? Who put her- ”

“Bharata,” Mother Kaikeyi frowns at him. “One question at a time. Someone must have left her there – a god, perhaps, or some poor peasant who did not have money to feed a child. How she survived the heat and the yoke and the oxen I do not know. A miracle, clearly, and proof that the child is blessed.”

“I hope Janaka raises her as his own,” Mother Sumitra says, waving her hand vaguely in the air, “since he found her and everything.”

“Found who?” Rama asks at last, finally interested in the conversation.

“A baby,” Shatrughan grouses. He is five summers old and has formed many opinions on babies ever since Shanta didi brought Rahul over; not one of them is complimentary. “I do not understand what the fuss is all about. Surely, it is as ugly and dirty as all others.”

Mother Koushalya laughs. “You know, a mere couple of years ago, you were a baby yourself.”

“Ew.”

“Now, now,” Father chides him. “Mithila is suffering from terrible droughts. Mayhaps the child will bring them good luck.”

“That is an awful lot of hope to pin on a babe,” Mother Sumitra remarks, cynical as ever.

There is a blessed silence as everyone contemplates this. Mithila falling out of Indra’s favour is old news; over the past years many messengers have come and gone from Ayodhya’s royal court, and many carts have rolled between the two kingdoms, bearing grains that would never be enough. Mithila had enough fertile lands to feed herself, but her people were more inclined to knowledge and learning, and rarely took up tools to divert rivers or dig canals. The seasonal monsoons watered most of their lands; without it the crops had withered and burnt in their fields, and the hard earth cracked open to gaping maws unsuitable for any agricultural endeavor. That a mere girl, however divine-born she might have been, could cure such a calamity…

“In any case,” Mother Koushalya says primly, giving their father A Look, “let us hope King Janaka will take her for the blessing she is. Daughters are not to be forsaken.”

Father sighs. “Dear, please…” he murmurs, then quails under his wife’s glare. Daughters are a sore subject between Ayodhya’s King and her eldest Queen.

“Do we know what her name is?” Rama asks, and Mother Kaikeyi smirks at his unsubtle attempt to steer the conversation away.

Dasharatha latches onto the distraction with both hands. “Whose name? The girl’s?”

Rama nods.

��They named her after the furrow she was found in.”

“Oh?”

“Mhmm,” Dasharatha smiles. “She is called Sita.”

2.

It is late when Guru Vishwamitra decides to halt for the night and invites the brothers to sit by their little fire.

“You did well today,” he says, and Rama thinks the sage almost looks pleased.

“It was all your blessings, Guruji,” he demurs, “and that of our parents’.”

Beside him Lakshmana supresses a snort, noting how he left Guru Vashistha out of the mix. While their companion ruminates on this with a beatific smile, his brother whispers in his ears, “You are going to be a great politician one day.”

Rama elbows him. Lakshmana elbows back, and then it is a boyish game that is barely discreet. Rama can feel the beginnings of a smile twitching on his face.

They are interrupted by Guru Vishwamitra, who folds his hands sternly over his lap, turns to them, and asks, without the barest hint of hesitation, “Say, Rama, have you ever thought of marriage?”

Rama sputters. Beside him, Lakshmana tenses, prepared to fend off any and all questions until Rama decides what to answer, like he always did back in Ayodhya, because Rama has the best brother in the whole wide world. But Guru Vishwamitra rolls over any protests.

“We shall stop at Mithila next, and the noble King Janaka has under his care four comely young maidens – two his own, and two his brother’s.”

The crickets chirp in the shadow of the forest. Rama stares, unblinking and silent.

“Forgive my impudence, revered one,” Lakshmana says at last, when it becomes evident that Rama will not answer, “but my brother believes it is improper to speak of such matters without consulting our elders.” His brother chances a glance at him. “And he also thinks the man and the woman should get to know each other beforehand.”

The last part is entirely Lakshmana’s own addition, since he despises the idea of marriage and has long hoped to turn away any potential suitors by acting churlishly. That is unlikely to happen, given that few fathers care for their daughters’ opinions, and Lakshmana is charming even in his devilry. Rama refrains from mentioning any of this, especially because Lakshmana has clearly caught the ‘four maidens’ comment.

Guru Vishwamitra nods, meanwhile, as if he has expected something such all along.

“That is all very well, my boy, but let me tell you this. Janaka’s eldest child is the mightiest woman to ever walk upon Aryavart, and the most virtuous. When she was yet a child, she lifted with one dainty hand the Destroyer’s bow. Then her father declared that such a maiden’s hand may only be claimed by one who could perform a similar feat.”

“How… awe-inspiring,” Rama manages at last, already daunted by the thought of this princess.

Guru Vishwamitra smiles. It is the kind of smile that Shatrughan has when someone is about to find dead fish among their clothes.

“Do not worry about your father,” the sage says nonchalantly. “We shall reach Mithila by tomorrow. Look sharp, Rama, it is the princess’s Swayamvar. You will lift the Pinaka, and then knowledge and valour shall be wedded, and what a joyous day it shall be! Do you not agree?”

“Ah, Guruji,” Rama gropes about for anything that will dissuade him. “The Pinaka is a legendary bow, and I am but a young boy.”

“I have faith in your ability, Bhaiyya,” says the traitor heretofore known as Lakshmana, Rama’s brother, “and as he told you, our Guru thinks similarly.”

“I do not even know her name,” Rama says, desperately elbowing Lakshmana when the latter starts to snicker.

Their Guru shrugs. “That is easily solved. She is called Sita.”

3.

Rama is broken. There is no other way to put it – this empty haze that mars his sight, this endless sorrow that mires him down, this bleak, bleak search that shall never end – Rama is irrevocably ruined.

He feels nothing save grief and rage, and knows nothing save that they must go on and on and on, till they have eclipsed the earth thrice over, till they have searched every nook and cave and treeshade, pausing neither for food nor rest nor death.

He screams, sometimes at the forest and sometimes into the earth, and sometimes at foolish, foolish Lakshmana, who is so exhausted and so dear, and Rama thinks he knows what the Pinaka’s master will do at the breaking of the world, for he feels that catastrophe within the traitorous organ beating in his chest, calling through the bars of his bones like a forgotten prisoner, ‘Sita! Sita! Sita!’

“Bhaiyya, please,” Lakshmana begs, gripping his shoulders tighter than ever before.

Once Rama was stronger, but now he even struggles to loosen his hold. “Let me go,” he wails, writhing and unseeing. “I will not, I cannot- ”

“You need to, Bhaiyya,” Lakshmana insists, tightening his hands, pressing fingers to the hollow between Rama’s clavicle and collarbone.

Rama shakes like Mount Meru trembling under Sachi’s wrath. “I need to?” he demands. “I need to? Like you needed to leave Sita, needed to search for me, despite your faith in me, despite knowing that- ”

Lakshmana’s hands unclench, and Rama finds himself sinking. His gaze clears, little by little, and he hears his brother make a strange, muffled sound, and he is sinking to his knees, familiar hands guiding him, but no longer restraining. There is an Asoka’s trunk to his right, and he is made to lean against it, all gentle-soft and slow. When he looks up, Lakshmana’s face is turned away, tears leaking out of the corner of his eye, mingling with the blood on his chin from where he has bitten his lip to hold back a sob.

“Lakshmana,” he murmurs, reaching out to him, and oh, there are flecks of dried blood on his knuckles, and oh, Lakshmana’s temple is a sickly purple when he looks back, like the costliest dhoti muddied by rain, and when, oh, when did he strike the most beloved of brothers, and why?

Lakshmana is kneeling beside him, always one reverent inch behind the bend of his arm, running a thumb over the crimson remnants of violence.

“It was not your fault,” he soothes, lilting like a childhood song. “You did not see me coming.”

When? he wants to ask, how? But the haze returns like insidious tendrils of fog. He should be comforting Lakshmana, he thinks, for it was always his job to quieten his brother’s temper. Lakshmana needs comforting, he knows, but Lakshmana is not angry. Why, then…

Someone shakes his shoulder. “Bhaiyya?”

“Uh,” he offers intelligently.

“I am going to get some water, okay? Please, please do not leave. You need to rest awhile; we are no use to Bhabhi if we are dead.”

He waits for Rama to nod his assent, and leaves with tear-tracks on his cheeks. That was why Rama should have comforted his brother – Lakshmana was crying. And now he is gone, and Rama is seated under a tree waiting for him to bring water, like that blind old couple had so many years ago waited in vain for Shravana Kumara. They cursed his father for slaying the boy, and that curse drags ever on, even today. What would Rama do if some stray arrow found his brother’s heart? Would he curse the shooter, even if it was a chance of fate? No, he thinks, he would hunt them down, and then burn cursed Dandaka, all the way from the Vindhyas to the unresting sea, with every man and beast and rakhshasha in it.

Perhaps because he has such a keen ear, or perhaps because he is thinking about it, he hears a terrible, piercing groan, and shoots up. The sound comes again, and Rama runs. It does not occur to him that he runs the other way, or that he should take his bow. All he does is plough through the tall trees, tripping on roots and choking on outstretched branches, fighting against Aranyani’s will.

When he finally stumbles upon the body, all he can think of is that it isn’t Lakshmana. Then the groan comes again, and he rushes over to the feathered being, kneels by its side. Once, it must have been a great bird, but now there are only stumps where the wings would have been, and it has a gaping hole in its stomach.

“My dear,” Rama says, already knowing it beyond saving, “rest. All will be well.”

To his surprise, the bird opens its eyes. “Who are you?” it asks, in a distinctly masculine voice.

“Rama, son of Dasharatha,” Rama says, and looks up to some scuffling. “That is my brother, Lakshmana,” he adds, as said brother tumbles into the clearing with wide eyes, twin bows and ruffled hair.

“Dasharatha?” Clarity rushes to the bird’s eyes. “Once, I, Jatayu, named him friend. Wait, you are Rama and Lakshmana? That woman called for you.”

“So we are,” Lakshmana agrees, kneeling as well. “What woman sought us, noble Jatayu?”

“The fairest of them,” Jatayu says, “with the darkest curls and most beautiful mien I ever knew. She wept from the perch of the Pushpaka Vimana and called high and low for aid, even as Ravana took her ever southward to his golden state. I sought to free her, friends, and so I fell wingless from the sky.”

Rama dares not hope, dares not breathe. “Southward?” he asks, settling on the least painful, and most important detail.

“Southwards to Lanka,” Jatayu explains, words slurring again, “to that seagirt island he names his own. I shall not be here long, but I beg you, make haste my friends.”

There is a noose uncoiling from Rama’s chest. He needs to thank Jatayu for his aid, for trying to save his wife, for being their father’s friend; he needs to make sure he passes away in peace. And he will do it all, only after one last question.

“Do you know who she was?”

“Mhmm,” Jatayu hums. “She called herself Sita.”

4.

Hanuman leads them up Mount Rishyamukh with nimble leaps and fleet feet. Rama and Lakshmana toil behind, each hard-faced so as not to give away how strenuous they find all this jumping.

“I feel like a stray goat,” his brother mutters, teeth clenched to hold back huffs. “He is showing off for you, and naturally, I am the one caught in the middle.”

“If you think I am enjoying this…” Rama begins, then sighs to mask his panting.

“Then why do you not ask our guide to slow down? He seems to like you well enough.”

Rama snootily turns his nose up in the air. “We are the scions of Ikshvaku, heirs of the Raghu clan. We must endure.”

“You mean you must endure.” Lakshmana’s voice is sardonic as he continues, “If my honour comes from attempted suicide by heat exhaustion, I care little for it.”

“If I have to climb up this thrice-damned mountain without protest, then so will you.”

Silence. Rama turns, alarmed, half afraid his jesting has been taken seriously. They have not spoken about everything that came to pass in the weeks before meeting Jatayu, and although Lakshmana’s bruise has long healed, Rama’s heart has not. But no, his brother is smirking and shaking his head, and when Lakshmana speaks, his voice quivers with mirth. “You are mean.”

Rama exhales, yet relief does not come.

“Lak- ” he begins, but is immediately interrupted by a joyous shout from above.

“Prabhu!” Hanuman beams down at them, “We are here.” Then he turns and addresses someone else, “Oh, please do tell Maharaj Sugriva, he shall be most elated.”

Lakshmana eyes the remaining steps and then surveys the distance they have come.

“This should not have been so difficult,” he mumbles, and Rama is inclined to agree. Once the two of them could have scaled the peak without breaking a sweat and run three miles afterwards. All that crying and bumbling about the forest must have made them soft.

Sugriva – dressed in old finery and worn purples – comes to meet them in a great, cavernous hall, reeking of cheap wine and misery. The crown on his head is scratched and askew.

“Show them what we found,” he tells one of the attendants, after Hanuman has recounted their tale of woe, and nods to them. “Please, have a seat, my lords.”

Rama sits and tries not to quiver with anticipation. This is it. He can feel it in the air – this is the key to rescuing Sita. Lakshmana stands by his side, half a step behind, and places a hand on his shoulder.

“We found them on the ground,” Sugriva says, tail flicking nervously. “By the time I was called, it was all over, but my Vanaras say a great golden chariot had flown across the skies, and from it came the weeping of a maiden most fair.”

He pauses, as a worn pouch is brought in, and a bearer places tall earthen glasses of drinks before them. Rama ignores the latter and reaches for the pouch.

“This has the ornaments you found?”

“Yes.”

Rama pulls apart the string holding it together and turns it over on his palm. A familiar necklace falls out, thick and glittering gold, followed by a lonely earring, a chain, and an anklet strung with little bells.

Rama stares.

“Prabhu?” Hanuman probes. “Are these the ones you seek?”

“Yes,” he breathes, fingers trembling, stroking the trinkets as if they could somehow pass on his affection to their beloved wearer. “These are hers.”

He looks up to an assortment of pitying glances. They can tell the woman is someone important, though neither Rama nor his brother had revealed in as many words that Sita was his wife. Did they think of him an idiot, a desperate father, or a maddened brother, or a lovelorn husband clutching to circumstantial proof of a dear one’s presence?

As he has done these past weeks, and all their lives, Lakshmana comes to the rescue. “I recognise the anklet.”

Sugriva hesitates. “My Lord Lakshmana?”

“The anklet,” he repeats. “I saw it every morn when I knelt for her blessings. I would not confuse them for any other.”

“And the others?”

“Uh,” Lakshmana blinks. “I would not dare be so importune with a lady as to stare at her person” – here Rama catches Sugriva stiffen minutely, as a guilty man does when caught, but Lakshmana has spoken without malice, and it passes as quickly as comes – “but her sister has an earring of similar fashion.”

“You will not look at her but you will look at her sister,” Sugriva notes, and it is interesting how he has latched onto that.

Lakshmana turns pink. “I married her sister?” he says, phrasing it like a question, as if all those days with Urmila were a fever dream. Rama can relate.

There is an awkward pause, and his brother plows on with all the daintiness of the bulls that once ploughed the land Sita rose from. “What was she like?”

“I told you – I have not seen her. My people told me this: that she was the fairest maiden they ever beheld, shining like the sun at high noon, that her voice was like starlight, and that she called for the scions of Raghu to aid her. Twice she called for one Raghurai, and once for a Saumitra.”

Rama cannot help the smile on his face. Of course, Sugriva will surely ask for some terrible recompense, but he is an outcast King, and exiled besides. He will not shirk from helping.

Beside him, he feels his brother relax. “She is no mere maid,” Lakshmana drawls. “She is the daughter of King Janaka, of distant Mithila, and the wife of Rama, prince of Ayodhya. She is Sita.”

5.

Rama eyes the prodigious young twins seated on the floor of his court. They are young, barely a year older than Bharata’s oldest, and the sight of them makes something in Rama’s chest tremble. It has been a long time since he has been blessed with the sight of his wife, save in the terrible gilded statue that occupies her place beside him. Today, though, he sees her everywhere – in the curls of the twins' hair, in the way the older one smiles, and the younger wrinkles his nose. He sees her even in the way they hold their veena, which makes little sense, given that most people hold their instruments the same way.

They had introduced themselves as students of Rishi Valmiki, without any patronymic. That means nothing. They could simply be referring to the one who sent them here. But their mother must have been pregnant the same time as Sita, if age is any indication, and Sita had been having twins, and they did look awfully like her...

“Greetings, Your Majesty,” says Kusha, the older twin, his hair sticking up like the grass he was named for.

His voice is a blessing, for it derails Rama's terrible thoughts, and a curse, for it sounds so like Sita's that he may as well be in Mithila's gardens more than two decades ago, facing a demure princess who would later be his wife.

This is folly, he thinks, nodding at the young ones, permitting them audience.

Kusha continues, “Our Guru, the mighty sage Valmiki, was immensely inspired by your tale. Thus, he composed an epic, so all the world may remember the valour of Shri Rama.”

“It is still being written as we speak,” Luv says, picking up where his brother left, “but we have learnt in song all that was penned down before we departed. If His Majesty pleases, we would be honoured to present it to you.”

Rama stares, then hesitates. Seeking self-praise is the path to downfall, and the story is painful besides. All save Lakshmana look eager – even Urmila, though she must have been told everything, either by her husband or by Sita. He should praise their dedication and send them away with blessings and a few gifts. There is no point in unearthing such sorrow again, not when the story has no triumph, and Sita is not by his side.

Luv and Kusha look up at him, familiar doe eyes wide and beseeching. They are clutching each other’s hands, tense with anticipation. Rama opens his mouth to disappoint them, and instead says, “Very well, we shall hear you.”

He could have cursed himself them, but the answering smiles he receives wash away all self-recrimination.

The courtiers clasp their hands and lean forward, and the boys bob their heads in a semblance of a bow.

“Hear us,” Luv proclaims, “for we sing of Rama, son of Dasharatha, of blessed Ayodhya.”

It is a familiar tale, of the joys of his childhood and the days at the Gurukul, the love of his father and three gentle mothers. But Rama knows, the grief is about to come.

He allows a tremulous smile when they sing of Sita’s Swayamvara, for it was a joyous occasion. He holds his breath when Ravana of the tale carries Sita away, but pain lances through him only once. He trembles when they exalt Sita’s resolve in the face of misery, trapped in her golden prison, and shivers when they recount Lakshmana’s deadly injury.

But just as he thinks that perhaps, having lived through it once, he has numbed himself enough to be able to get through this without the waterworks, the song rolls to their victory, and to Sita’s freedom.

“And then Rama of the golden bow,” Kusha intones, “says ‘I have not yet sunk so low, to take back unquestioned a spouse that has lived a year in another’s house.’”

Half the court inhales, and Rama feels a telltale burn behind his eyes. What has he done? He wants to throw out the boys, forgetting his fondness for them, wants to scream and curse and run away. But he is an Emperor, and this is his court, and such behaviour is unbecoming. The lay turns stern and punishing, quickening to a chant.

Sita in the epic stands as straight and bold as she had all those years ago, before an army of thousands. Her hair is a riot of curls blacker than the length of Nisha’s dread night; her face is as gaunt as Dhumavati’s terrible mien. When she speaks her voice is Indra’s thunder across the sky, devoid of any love or affection. “If you shall question me, husband,” she says, “then may Agni judge me. Lakshmana, son, make me a pyre.”

Lakshmana of the tale weeps, as he does in real life, both then and now. And Ravana’s captive, all molten iron clothed in a delicate body, walks out of the pyre unblemished and unburnt, lit red and orange and yellow – a living flame. For she is Janaka’s daughter and Rama’s wife, but she is also the mightiest woman that Aryavart would ever know, and the most virtuous.

The song ends with exaltations of their victory, and the joy of reunion, but Rama, seated beside a lamentable golden mockery of a woman he once named his own, hears none of it. His tears come hot and unbidden, like summer tempests across the plain, and he weeps and weeps and weeps.

+1.

Luv kneels on the green grass, wide eyes following an eagle's flight across the sky. Rama strokes his head, soft and gentle and in love. It is a tranquil morning, and Rama wonders if he should postpone court to prolong this moment. Beside him, Kusha hums softly, sprawled over the grass.

“You look melancholic,” Rama observes.

Kusha shrugs. Rama has yet to learn all his son’s expressions, but this one he knows intimately. His son misses Sita. Now that she is not here, it is his duty to comfort him. The thought warms Rama's heart nigh as much as it chills.

“Your mother,” he begins, then hesitates, unsure.

Kusha sits up. “What of her?” he demands, cornered and defensive.

Rama holds up his hands, feels Luv’s glower boring into the side of his face. Sita is a sensitive topic, lying between them with the treachery of a coiled snake, defying the peaceful manner of its namesake.

“Would you like to hear about her?” he offers at last.

Kusha frowns. Luv crawls over to look at his face. “Hear what?”

“Whatever you wish to know.” Rama will likely come to regret this, for they undoubtedly will ask something difficult to answer, but as the furrows part from Kusha’s brows, Rama thinks they can push through. He opens his arms, gathering them close, and kisses the top of their heads. Like this, it is not hard to understand why Dasharatha thirsted so desperately for sons, even if he was fated to die grieving for them.

Kusha interrupts his musing with a question. “Do you love her?”

“Of course!” Rama is scandalised enough that Kusha has the decency to look a little guilty.

That, however, does not stop him from his next question. “Why?”

“Why what?”

“Why do you love her?”

Rama cannot believe they are having this conversation, even though he can see why they might be curious.

“How could I not?” he says at last, when it becomes evident that silence will not make Kusha forget his question. “Sita was the loveliest woman – kind, generous, and brave.”

Kusha does not appear the least bit happy and Rama startles when Luv pokes his arm.

“Nuh-uh,” his son says, “those are easy things to say. You have to pick one.”

Rama opens his mouth to answer, then pauses. This is some sort of a test. Luv and Kusha have been wary of him ever since they arrived at the palace, hiding away from him and mingling mostly with their cousins. He is suddenly aware that this answer could have tremendous repercussions. But what can he say to such a question? How can he define peerless Sita with one virtue?

The children look up at him expectantly, so Rama clears his throat and tries to think. Sita was charming, and her beauty helped, but that was not the foremost of merits.

“Sita was… good at being good,” Rama says slowly, barely able to keep himself from quailing at the twin raised eyebrows. “It is hard to explain, you understand? But her virtues were restrained. She was terribly forgiving, but not so forgiving that she would take upon her a sentence twice over when she knew herself to be innocent. She could be generous, but never to a fault. She was selfless, but not so selfless that she would deny herself easy pleasures.”

And was that not true? Sita was pure, and in his heart of hearts Rama knows that even if Ravana touched or defiled her, even if Agni burnt her, it would only be her body that fell, only her vessel of flesh that would be blamed; her soul was far too pure and mighty to be affected.

And this is Raghuvamsa’s folly – they will cling to promises and tradition even in death, will give up sons to satisfy wives, forgive villainous servants and shy from righteous rage, forsake wives for the words of ignorant men. Had Rama not loved Sita for the same reason he loved Lakshmana? That even follies were to be embraced, even elders could be spoken against, even golden deer could be chased for the sheer joy of it.

“She had no excesses,” Rama tells their children. “She would forgive me for testing her once, but not twice. And I do not think I could have loved her as much if she accepted it.”

Luv and Kusha are looking at him. Rama tries to blink away his tears, but they come and come and come.

“Sita…” His breath catches, but he plows on. “They tell us that it is important to be selfless, to never ask for more than you have – not unless you can earn it yourself. But Sita knew I loved giving her things – clothes, jewels, flowers, anything. And even in the forest she would ask for a flower or a fruit or a sapling, because she knew it brought me joy. She cared.” The tears are falling now, but Rama cannot stop. “She cared, and then I threw it away. I knew her, and I failed her.”

Rama puts his face in his hands and sobs. All this, and he is not even sure he has managed an answer. He starts at the feel of small hands, and of cheeks pressed against each shoulder.

“What is past is gone,” Kusha murmurs, close by his ear. “But we are here. Father, we will always be here.”

The gong for the court sounds, yet no one moves. Perhaps, Rama thinks wearily, he has not failed at everything.

#i have so many feelings about this#I'm pretty sure I've rendered a few of them OOC bc that's how I see them in my head#but no way everything was as glowy as everyone makes it seem#will add on later about the other gods and goddesses referenced#rama#ram#lakshmana#lakshman#laxman#bharat#shatrughan#sita#hanuman#sugriva#ramayan#ramayana#hindu mythology#luv#kusha#ask#answered#boo writes#5 + 1 fic

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

hii i saw your amazing post on the ram mandir thing and i had to know your thoughts on this. i post about hinduphobia a lot, genuinely to spread awareness, and its a serious thing. i just saw a post by this person called tiredguyswag talking about how hinduphobia isn't real. its a real longass rant. i wanted to know what your thoughts were on it, and if you could debunk anything they were saying as false. ty!

Thank you so much for the appreciation <3 Every supporter counts. We will fight against this Hinduphobia, and we will emerge victorious!

I did go through the blog of this guy and honestly, this hellsite is exhausting. So are the hinduphobes and leftists. I might just exit someday because they do not deserve my energy.

To all the ones saying Hinduphobia does not exist— what was the Godhara train arson? What happened to the Kashmiri Hindus? What happened to the Brahmins of Pune post MK Gandhi's assassination? What happened to the Sikhs of Punjab after Indira Gandhi's killing? What was the emergency prior to that incident? What was that which happened to the 9 and 7 year old boys of Guru Gobind Singh ji? What happened to Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj? What was the destroying of temples and deracination of our Gurukulas? What was all that money and artifacts stolen from our country, has it not robbed the golden sparrow? What was the voluntary faulty translation of the Vedas and Puranas so that Hindus themselves believe that their culture is maligned? THERE'S NO HINDUPHOBIA? LOOK AT PAKISTANI HINDU GIRLS BEING FORCIBLY CONVERTED AND RAPED! The Mughal India holocaust! The ncert has the fucking guts to teach little minds that Aurangzeb protected and built new temples! And what's their source? They have none. No files. Nothing at all to support their claim, and yet they have been teaching it for god knows how much time. But we do have Babur himself writing in his book that he hated Hindus, called us pigs and what not. We have evidences that they raped our women, murdered our men, the children weren't foreign to their brutality. The invaders looted the Somanatha multiple times, broke the floating Shivalinga. They took away Ayodhya, Mathura, Kashi and so many other temples. Some shitheads have their asses in fire when they're seeing us celebrate the Rama temple. Y'all wouldn't be having a meltdown had the other side won the case. Y'all should rot in hell. You have no concept of country and social harmony, no global brotherhood, all your liberalism reduces to ashes when you see Hindus being happy for once. We have been killed for being idol-worshippers, and our fault is that we don't cease to exist.

They say we blame invasions for everything bad that has happened to us, but remember that we were the golden sparrow without them.

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

What was the age of Rama and Sita when they got married?

Child marriages did not exist in Ancient India. Vedas, Ithihasas, or Puranas do not mention any child marriage. All women in ancient times married after at least attaining 16 years of age, and most weddings were at Swayamvar.

Susruta, the ancient surgeon of India, wrote in his book ‘Susruta Samhita’ that the marriage age of a girl must be above 16 and for boys must be above 25 years. Many pseudo-scholars wrongly claim that Rama and Sita were kids when married, but Valmiki Ramayana proves them wrong.

Since Vedic era, Upanayana or initiation of education was considered as 2nd birth (Dwija). For Brahmins, it was done at age of 8, Kshatriyas at 11 and Vaishyas at 12. They were called Dwija (twice born) after that. Since both Sita and Rama were from Kshatriya families, both of them were initiated at 11. So after their 2nd birth (initiation), their new ages were 6 and 13 respectively, but their biological ages were 18 and 25 at marriage.

In Aranya Kanda of Valmiki Ramayana, Sita tells Ravana that she had stayed at Ayodhya for 12 years after marriage this is when Ravana appears before Sita in the guise of a saint, she entails the details of her family background.

She mentions that after her marriage with Rama, she stayed in Ayodhya for 12 years.

उषित्वा द्वा दश समाः इक्ष्वाकूणाम् निवेशने |

भुंजाना मानुषान् भोगान् सर्व काम समृद्धिनी || ३-४७-४

𝑑𝑣𝑎𝑎 𝑑𝑎𝑠ℎ𝑎 𝑠𝑎𝑚𝑎𝑎𝐻 means two & ten [twelve] years.

Sita says: "On residing in the residence of Ikshvaku-s in Ayodhya for twelve years, I was in sumptuosity of all cherishes while relishing all humanly prosperities. [3-47-4]”

Janaki also reveals that she was 18 at the time of exile while Rama was 25.

मम भर्ता महातेजा वयसा पंच विंशकः || ३-४७-१०

अष्टा दश हि वर्षाणि मम जन्मनि गण्यते |

"My great-resplendent husband was of twenty-five years of age at that time, and to me eighteen years are reckoned up from my birth. [3-47-10b, 11a]”

Sita also repeats the same to Hanuman in the Sundarkanda, stating that he stayed in Raghava’s house for a period of 12 years.

समा द्वादश तत्र अहम् राघवस्य निवेशने || ५-३३-१७

भुन्जाना मानुषान् भोगान् सर्व काम समृद्धिनी |

"I stayed in Rama's house there for twelve years, enjoying the worldly pleasures belonging to humankind and fulfilling all my desires."

On this basis, a simple conclusion has been drawn by popular Bengali authors like Rajsekhar Basu and Upendranth Mukherjee et al [2]. Both of them (and many others) have suggested in their footnotes that Sita was married to Rama when she was only six years of age.

Many great commentators of the Ramayana from the South have tried to analyse the age of Rama and Sita from the prism of spiritualism.

Nagoji Bhatta, whose famous commentry on Ramayana - “Tilaka” (whose views align with the Advaita school of Sankaracharya) [3] explains:

रावणेन त्विति । आत्मानं जिहीर्षुणा परिव्राजकरूपेण रावणेन पृष्टा वैदेही आत्मना स्वयमेवात्मानं शशंस ।। 3.47.1 ।।

ननु पूजामात्रं कर्तव्यं किं प्रतिवचनेनेत्याह ब्राह्मणश्चेति । एष अनुक्त इत्यार्षो ऽसन्धिः । अनुक्तो ऽनुक्तप्रतिवचनः ।। 3.47.2,3 ।।

सर्वकामसमृद्धिनी । व्रीह्यादित्वादिनिः ।। 3.47.4 ।।

राजमन्त्रिभी राज्ञो राज्यनिर्वाहकैर्मन्त्रिभिरित्यर्थः ।। 3.47.5 ।।

संभ्रियमाणे । संपाद्यमानसंभारे इत्यर्थः । भर्तारं दशरथम् ममार्या मम पूज्या श्वश्रूः । "अनार्या" इति क्वचित्पाठः ।। 3.47.6 ।।

मे श्वशुरं सुकृतेन परिगृह्य वररूपेण सुकृतेन वशीकृ��्य । यद्वा धर्मेण शापयित्वेत्यर्थः । मम भर्तुः प्रव्राजनं भरतस्याभिषेचनमिति द्वौ वरावयाचत ।। 3.47.79 ।।

Rama’s age was around 25 years at the time of leaving Ayodhya.

Twenty-five corresponds to the twenty-five principles of the Sankhya system, of which the 25th is seen as 𝐂𝐡𝐚𝐢𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐲𝐚 𝐏𝐮𝐫𝐮𝐬𝐡𝐚 – which is Rama himself or as he is perceived to be.

In the Balakanda, Rama has been presented as an avatar of Vishnu. Being Chaityana Purusha, the whole world is pervaded by his life force, and nothing can transcend it.

In the case of Sita, 18 - represents the five subtle elements, five gross elements, five senses of action, and self, intellect and mind. This implies that Sita is the origin of these and represents Prakriti, the primordial nature of the Sankhya system. [4]

Siromani by Sivasahaya another popular commentary from the South have suggested that Rama was 28 years & not 25 at the time he left for the forest.

In the Balakanda (Sarga 20), King Dasaratha says to Viswamitra:

ऊनषोडशवर्षो मे रामो राजीवलोचनः |

न युद्धयोग्यतामस्य पश्यामि सह राक्षसैः || १-२०-२

"Less than sixteen years of age is my lotus-eyed Rama, and I see no warring aptitude to him with the demons. [1-20-2]”

Here, he probably meant that Rama is just shy of 16, could be anywhere between 15-16.

Now, ‘𝘝𝘢𝘺𝘢𝘴𝘢 𝘗𝘢𝘯𝘤𝘢𝘷𝘪𝘯𝘴𝘢𝘬𝘢𝘩’ – could mean someone whose age is 25+3 =28, if we go by the etymology of the word.

It coincides with Sita's narration. If Rama went with Viswamitra at the age of 15, married Sita the following year, then he should be 28 by the time he left the city.

Sita says she was ‘𝘢𝘴𝘵𝘢𝘥𝘢𝘴𝘢𝘷𝘢𝘳𝘴𝘢𝘯𝘪 𝘨𝘢𝘯𝘺𝘢𝘵𝘦’, so she must be 18 when she left Ayodhya. [5]

In the Ayodhyakanda, Kauslaya says to Rama that she had waited 17 years from his second birth after hearing that his son has been banished to the forest.

दश सप्त च वर्षाणि तव जातस्य राघव |

असितानि प्रकान्क्षन्त्या मया दुह्ख परिक्षयम् || २-२०-४५

Kausalya: "Oh, Rama! I have been waiting for seventeen years after your second birth of thread ceremony, with the hope that my troubles will disappear at one time or the other."

Here the word ‘𝘫𝘢𝘵𝘢𝘴𝘺𝘢’ is an indication of Rama’s age. In [1-20-2], King Dasaratha himself claims Rama was less than sixteen years i.e. fifteen years of age when he accompanied the sage Viswamitra and was eventually married to Sita.

According to Sita’s narration, Rama had spent 12 years of his married life before King Dasaratha decided to install him on the throne as Prince Regent. So, Rama’s age can’t be 17 at the time of exile.

‘Jatsaya’ means ‘born for a second time’. It has been interpreted as the second birth of Rama’s thread ceremony which indicates the investiture with the sacred thread. Going by rules laid down in Smritis, it must have taken place at the age of ten to eleven – “𝑒𝑘𝑎𝑑𝑎𝑠𝑒 𝑣𝑎 𝑟𝑎𝑗𝑎𝑛𝑦𝑎𝑚”. [6]

Thus, Rama must have been 27-28 at the time of leaving Ayodhya.

𝗖𝗿𝗶𝘁𝗶𝗰𝗮𝗹 𝗘𝗱𝗶𝘁𝗶𝗼𝗻 [𝐂𝐄]

The Critical Edition of The Ramayana has removed the shloka where Sita suggests that she was 18 years of age. Also, they have found inconsistency in the text regarding Sita’s stay in Ayodhya. The Baroda Edition suggests Sita had stayed for just one year in Rama's house after her marriage.

संवत्सरं चाध्युषिता राघवस्य निवेशने |

भुञ्जाना मानुषान्भोगान्सर्वकामसमृद्धिनी || ४||

Aranyakanda, sarga 45, states clearly that Sita stayed for one year only.

Also note, here Sita says – राघवस्य – in the house of Rama – instead of the Ikshashu family (इक्ष्वाकूणाम्), as given in the Vulgate text.

Critical Edition collected 42 manuscripts (MSS) for studying the Aranyakanda, of which they selected only 29 for use (partial or composite). The North Edition consisting of scripts in Bengali, Nepali, Maithili, Sarada, Newari, Devanagari – had 14 MSS. Likewise, Telegu, Grantha, Malayalam and Devanagari made the South Recension, which contributed to 15 MSS for the study of Aranya Kanda.

The manuscripts are not uniform regarding the event of Sita residing for one year in her in-laws' house. All Southern MSS, plus N1 –S1-D1-5 (1 Nepali script, 1 Sarada script, Five Devnagari script) and the Lahore Edition of the Ramayana have the shlokas - उषित्वा द्वा दश समाः (that is 12 years).

Whereas, N2 – V1 – B – D6-7 (2 Nepali, 1 Maithili, 1 Bengali, and Devaganri) have the shloka - संवत्सरं चाध्युषिता (that is one year). It also appears in Gorresio (Bengal) and Calcutta Editions.

Critical Edition has decided to it keep one year, with Aranya Kanda Editor P.C. Diwanji stating – “it very well suits the context.” [7]

Likewise, CE has removed this shloka - अष्टा दश हि वर्षाणि मम जन्मनि गण्यते | - (that is I am 18 years of age) and made it a three-line stanza, somewhat contrary to Valmiki's rhyme.

मम भर्ता महातेजा वयसा पञ्चविंशकः |

रामेति प्रथितो लोके गुणवान्सत्यवाक्षुचिः |

विशालाक्षो महाबाहुः सर्वभूतहिते रतः || १०||

CE has removed this shloka on the basis of transposition.

So, going by CE’s findings, Rama was 25 when he left Ayodhya. Sita (whose age is not mentioned in CE) stayed just one year with Rama after marriage before moving out, which means Rama was 24 at the time of his marriage.

CE also mentions that in Sundarkanda, Sita tells Hanuman – 5-33-17/18 – she spent twelve years in Raghava’s residence, a place that can satisfy all the objects of desire.

Once again, we see the same disparity. All Southern MSS, plus N1 –S1-D1-5 have suggested that she stayed 12 years, and on the 13th year, Rama was supposed to be coronated.

Whereas, N2 – V1 – B – D6-7 claims that Sita stayed for just one year and it also appears in Gorresio (Bengal) and Calcutta Editions. The Lahore Edition of the Ramayana doesn’t mention this shloka at all.

The Critical Edition follows a critical apparatus of filtering text, but on this occasion even they have failed to weed out inconsistencies.

The North East Recension (whom they have based their shlokas for this particular case) says Rama was 25 years of age at the time of coronation, while the North West Recension says he was 27-28.

The Bengal edition doesn’t mention the age of Rama.

General Editor of Baroda, Dr Bhatt claimed that the North West recension contains the oldest MSS and that it is the oldest composite edition – known as the Lahore edition.

Therefore, a natural question arises -- why in this case, despite having an old MSS and a composite edition, CE chose to go with a relatively later MSS on the basis of apparent logic which they felt suits the context?

It differs markedly from Sita’s version at Sundarkand. Why did the editor of the Sundarkand - G.C. Jhala - not go with Sita’s one year stay (her speech to Hanuman) to maintain the consistency?

Jhala writes in the Appendix of the Sundarkand that Sita’s speech to Hanuman has been kept as it is in line with CE’s methodology, but in Arayankanda, when the issue was raised, General editor, Bhatt, went with one year (despite not all evidence backing up) because he felt that was the most logical deduction of the event.

The CE notes in the Appendix – “The reference to 25 or 27 (regarding Rama’s age) seems to be an interpolation or later edition.”

The reason being, CE focuses on Kausalya’s speech to Rama as the focal point – that he was 17 years of age at the time of the coronation. And yet, they completely ignored the word ‘𝘫𝘢𝘵𝘢𝘴𝘺𝘢’.

CE has also kept Dasaratha’s speech to Viswamitra that is Rama was less than 16. So, if Rama gets married at 24, it’s improbable to think that it took eight years for him in the forest to kill Taraka, saving Ahalya and then moving to Mithila.

CE is implying that Rama was 17-18 years of age when he left for the forest (keeping in tune with Kausalya’s words) and negating Sita’s version of 25 years, although they didn’t remove the shloka, only suggesting it could be an interpolation. They didn't consider the concept of 'second birth' - or the Upanayana when it's clearly mentioned in the text.

Camille Bulcke [8] has suggested in Ram Katha (pg 359) that if Sita had stayed for 12 years in Ayodhya that portion was not properly documented, alluding that an avatar of Vishnu leisurely wasting 12 years of his life is unthinkable, and hence that portion is an interpolation.

So, we have to take a holistic approach here.

Going by the Vulgate, Sita was six years of age at the time of her marriage. However, cross-references and analysing the text on the pretext of the Vedic cult defies logic.

The Vedic and post-Vedic literature like the Mahabharata and the Grhyasutras suggest the minimum age of marriage for a girl is ideally 16, or it is better to say when a girl attains her puberty. [9]

King Janaka says to Viswamitra in front of Rama in Balakanda - 𝘷𝘢𝘳𝘥𝘩𝘢𝘮𝘢𝘢𝘯𝘢𝘢𝘮 𝘮𝘢𝘮𝘢 𝘢𝘢𝘵𝘮𝘢𝘫𝘢𝘢𝘮 – that is – my daughter has come of age. [1-66-24]

Also, Janaka recounts that the Kings of Aryavatra tried their luck lifting the bow to win Sita who was a Viryashulka.

ततः संवत्सरे पूर्णे क्षयं यातानि सर्वशः || १-६६-२२

साधनानि मुनिश्रेष्ठ ततोऽहं भृशदुःखितः |

“Then elapsed is a year and in anyway the possessions for livelihood went into a decline, oh, eminent sage, thereby I am highly anguished [1-66-22b, 23a]”

Does that mean, the Kings were fighting to marry a five-year-old girl at that time?

Also, it is interesting to note what Sita says to Rishi-wife Anasuya.

पति सम्योग सुलभम् वयो दृष्ट्वा तु मे पिता |

चिन्ताम् अभ्यगमद् दीनो वित्त नाशाद् इव अधनः || २-११८-३४

Sita says that her father was anxious as she has reached the age of “𝘱𝘢𝘵𝘪 𝘴𝘢𝘮𝘺𝘰𝘨𝘢 𝘴𝘶𝘭𝘢𝘣𝘩𝘢𝘮” – that means where the husband can have a holy union.

सुदीर्घस्य तु कालस्य राघवो अयम् महा द्युतिः |

विश्वामित्रेण सहितो यज्नम् द्रष्टुम् समागतः || २-११८-४४

लक्ष्मणेन सह भ्रात्रा रामः सत्य पराक्रमः |

Sita says that when all the Kings failed to lift the bow, Rama visited Mithila after “a very long time”. These are found in all MSS (no chance of interpolation) and therefore Sita’s statements here hold paramount importance.

The fact that Sita gave Rama a permanent place in her heart (1-76-14) and that the princes enjoyed pleasures in the palaces after marriage logically points to that Sita can’t be six years of age at that time. [10]

So, there can be a multitude of probabilities. Rama can be 16 or 24 at the time of marriage. However, Sita surely has crossed her puberty at the time of marriage, and can’t be six years of age.

Reference:

[1] – Valmiki Ramayana – Hanumanta Rao

[2] – Valmiki Ramayana – Rajsekhar Basu

[2] – Valmiki Ramayana – Upendranatha Mukhopadhyay

[3] Valmiki Ramayana, CE – Volume 1

[4] Valmiki Ramayana with Tilaka commentary

[5] Valmiki Ramayana – IIT

[6] Manu Smriti – Sacred Text (online)

[7] Valmiki Ramayana, CE – Volume 3

[8] Ramkatha – Camille Bulcke

[9] History of Dharmasastra – P.V. Kane

[10] The Riddle of the Ramayana – C.V. Vaidya

#ramayana#ramayan#Ramcharitmanas#valmiki ramayan#ramayan serial#ramayan sita#sita#bhagavatam#srimadbhagavatam#bhagwan shiv#mahabharata#shrimadbhagwatgeeta#bhagvadgita#padmapuran#valmiki#sriram#srimad#srikrishna#shrikrishna#rama#vedas#vedic astrology#Vedic Jyotish Online#vedic astro observations#astrology numerology vedicastrology#astrology numerology vedicastrology#vedic astro notes#vedic chart#puranas#rg veda

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Novel Score

It's sometime around the beginning of a month, which apparently means these days that it's time for me to do a roundup post of the books I read in the preceding month--in this case, January 2024. Once again have been keeping on top of it during the month which helps me actually produce it in a timely manner. Because I started this back in November/December, doing monthly book posts isn't a New Year's resolution, unless the resolution was just "keep doing it". I'm keeping doing it.

Book list under the cut, book-related ramblings may include spoilers for Lois McMaster Bujold's Vorkosigan series, Martha Wells's Murderbot series, Kelly Meding's Dreg City series, and maybe others. You have been warned.

Ashok Banker: Siege of Mithila, completed January 6

As mentioned previously, I am rapidly running out of books by male "diversity" slot authors in my collection. I read the first Ashok Banker book, Prince of Ayodhya, a few years earlier, and was kind of meh on it, so I wasn't sure if I would continue. But I did pick up the other one as a library discard (ah, the days when I got books and CDs as library discards…back when they used to have a sale rack in the local branch all the time, instead of saving them up for periodic bulk sales…) so I hadn't entirely given up on it. So, in not quite desperation, I turned to Siege of Mithila as my next diversity read.

The series is apparently a retelling of the Ramayana, which is some kind of important epic in India, though I can't judge if it's like "the Bible" or "King Arthur" or "The Iliad" or what, but I assume it's somewhere on that level, at least among certain cultures. My brief skimming of the Wikipedia article on the Ramayana implies that Banker is following the story pretty closely, which means that sometimes it gets a little weird plotwise, but is perhaps more revealing culturally or something. And sometimes it's a wee bit problematic…like the way that the main adversary for the first two books is Ravana, lord of the Asuras (basically demons), who rules over the southern island kingdom of Lanka (like…"Sri Lanka"?), which is populated entirely by Asuras. Which is about like if there was a fantasy series set in England where they had to fight evil demons from the western island kingdom of Eire or something. (Wait…do they have those?) One wonders if this series (or the original Ramayana) are quite as popular in Sri Lanka, then…

Anyway, we mostly follow Rama, the titular Prince of Ayodhya from the first book, and his half-brother Lakshman, but a lot of this book is also set back in the palace in Ayodhya following Rama's father the Maharaja, his three wives, and the evil (and hunchbacked--oh look, it's equating deformity with wickedness, that's awesome) witch Manthara as she and Ravana try to sabotage the kingdom from within. Rama and Lakshman end up going to Mithila instead of back to Ayodhya, and foiling a big Asura attack on the city, which comes unbelievably close to the end of the book and is not quite solved by deus ex machina, but doesn't feel particularly satisfying.

One element of the series is that some of the characters are just like ridiculously powerful sages who were like "I've been meditating for 5000 years so I'm really wise and can do anything, though I guess I should let Rama solve a few things on his own to gain some of his own wisdom". Not that this is all that different from, say, Gandalf or Merlin, of course... There are also some odd storytelling choices, like switching to a different set of characters just at a dramatic point in a different storyline, or, in one major side-quest, just skipping the ending of it and coming back to it a couple of chapters later in flashbacks. Also, one character is given important advice by a ghost which he then completely ignores (luckily other people overrule him, but it bugged me).

The book kind of feels like the second book of a trilogy, but not quite, which makes sense because apparently there are eight other books in the series, so it's not just about fighting Ravana and the Asuras. I'm on the bubble about the series, as you may have gathered, so I don't know offhand if I'll be going on.

T. Kingfisher: Clockwork Boys, completed January 9

I paced myself going through Siege of Mithila, taking seven days for it (I started on December 31st to get a little head start), so it put me a bit behind on my Goodreads challenge (100 books for the year, again). This means, time to read some shorter things! I haven't read any T. Kingfisher yet (though I have read, like, the webcomic "Digger" under her real name, Ursula Vernon, if nothing else), so I let my wife, who has read a lot of them, suggest which one I should start with, and this was the one she chose (at the time; it may have been a couple of years ago). We have it as an ebook from Kobo, which sometimes makes it a little hard to tell how long the book actually is in pages, but Goodreads claimed it was under 300 pages, so it seemed a possible three-day read.

I was, I guess, vaguely expecting a steampunk story involving two boys who were made of clockwork or something, but apparently it's more straight fantasy (not too similar to the Ramayana was far as I can tell, though, which is good because I like consecutive reads to vary in genre if at all possible) where the Clockwork Boys are the bad guys. Also, apparently this is the first of a duology, a "long book split in two" duology as opposed to "book and a sequel featuring the same characters" duology.

The characters seem somewhat interesting, though I'm not sure I'm 100% won over. Sir Caliban for some reason reminds me of both Sanderson's Kaladin and Bujold's Cazaril, but maybe it's just the similarity of names enhancing certain similarities of character. And the demons also made me think of Bujold's Penric books. Maybe the tone is a little light for me on this one. We've got the second one as an ebook too, so I'll finish it off at some point and then maybe take a look at Nettle & Bone or something.

Kelly Meding: The Night Before Dead, completed January 12

As I may have also mentioned previously, I've tried a whole lot of urban fantasy series. Many of them, my wife has enjoyed more than I have, and is all caught up on them, but most of those I'm only a few books in. (I've given up on relatively few--Jennifer Estep and Jess Haines, among others.) For whatever reason, my wife didn't like the first book in Kelly Meding's "Dreg City" series, Three Days To Dead, and this time, to be actually clever about it, I decided to read the book myself and decide if I wanted to continue on in the series before it went out of print. As it turned out, I did like the first book, and I kept reading it on my own. When the series got dropped by the publisher after four books, I even went and bought the last two books (self-published, probably print on demand) to finish the series.

So this is the last one, which is supposed to wrap up the main conflict. Our main character, Evy Stone, started out the series waking up after death in a newly-vacated body; she was part of a group that worked to deal with paranormal threats. This world has beast-form shapeshifters named "Theria", vampires, and lots of types of fey--mostly pretty usual when it comes to urban fantasy--and their existence is unknown to world at large, etc.

Thie book does seem to wrap things up well enough, at least for the main characters, though it's hard to say if all the resolutions are satisfying. Still, it was enjoyable enough. She does have a couple of other, shorter series which I can try next, since we do actually own them. (And maybe some stuff under a different name?)

Lois McMaster Bujold: Brothers In Arms, completed January 15

Next (chronologically) in the reread order, this is the one where Miles goes to Earth and discovers the existence of his clone-brother Mark (spoilers). It starts up with a level of frustration--why does Miles have to stay at the embassy, and why aren't his mercenaries getting paid?--but things mostly work out in the end. Ivan shows up again (by authorial fiat--it's a bit too much of a coincidence, really), we meet recurring character Duv Galeni, and of course Mark, as mentioned already. It's not a particular favourite, but it's pretty good. And without it, how would we get Mirror Dance, and thus Memory?

I feel like I should be able to say more about it, but I've already talked about the Vorkosigan series a lot in previous posts, and, like I said, it's not a particular favourite. I guess I could mention how the first time through the series I read them in publication order, and so this was before The Vor Game and Cetaganda… Also, although we don't see much of Earth outside of London, we do get a good look at the gigantic dikes being used to hold back the ocean, because in the intervening mumble-mumble centuries the sea levels have risen. So presumably the icecaps have melted or something, though it doesn't seem like the Gulf Stream has shut down or anything, so maybe they have managed to mitigate things somewhat. An interesting view of future Earth, anyway, without going too overboard on covering the vast majority of the planet not relevant to our immediate plot.

Seth Dickinson: The Traitor Baru Cormorant, completed January 20

Taking another book from my list of authors to try (currently stored on my pool table); I picked this one because apparently the author has a new book coming out, and I do see people talking about the character from time to time, so clearly this is a book/series that has had some staying power and cultural impact, as opposed to something obscure that apparently sank without a trace. But this is a book that my wife tried, and either didn't finish or didn't want to continue the series.

And, having finished it, I can see why. I wouldn't say that it's a bad book…but I didn't, in the end, like it. I read it all the way to the end, and I've decided I'll leave it there and not try to continue the series. And probably I won't look for other books by Dickinson either. Like Ian McDonald's Desolation Road, which I read last year, I felt, as I was reading it, that this was a book I would have liked a lot better when I was younger, but these days it just doesn't do it for me.

It has the feeling of fantasy, in that it's set in a different world from our own, and there is none of the futuristic technology that would explain this as being a colony world…but there is also little or nothing in the way of magic. A little alchemy, maybe, but I don't know that it's out of line with what you could achieve with actual drugs. No wizards, and I don't think there were supernatural creatures either. But it's fantasy-coded, and maybe there's some minor thing I'm forgetting. It's not about magic, though. It's really about colonialism, and what happens when you're sucked into the colonizer's system so far that you think that the only way to help your people is by going along with that system. And Baru Cormorant is somewhat autistic-coded, perhaps--not only is she a savant, but she seems to have trouble figuring out the motives and feelings of others. Puts too much confidence in the ability to explain everything using economics (the character and possibly also the author, quite frankly), in a way which reminds me mostly of Dave Sim's deconstruction of faith and fantasy in Cerebus: Church And State. Not sure if it counts as grimdark, but it feels like the honorable are punished for their naivety like in "A Song of Ice And Fire". I lost sympathy for the main character partway through, and never got much for anyone else either. One character I liked and hoped to see more of was (gratuitously?) killed in the middle of the book. I was forewarned of the existence of a plot twist at the end of the book, and when it came, although I wasn't completely surprised, I was disappointed, and I didn't feel that it worked.

So, yeah. Your mileage may vary, but this book did not win me over.

Charles Stross: The Annihilation Score, completed January 25

I wanted something a bit more light-hearted after the previous book, but not, apparently, too much so. Charles Stross's "Laundry Files" series is set against a backdrop of cosmic horror and the looming end of the world, but also of British governmental bureaucracy, out of which he can usually pull of a fair amount of humour, as well as humanity. The main protagonist of the series is Bob Howard (named in honour of Robert E. Howard, inventor of Conan and friend of Lovecraft), computational demonologist, and the books in turn have paid tribute to a lot of different sources--James Bond, vampires, American evangelical megachurches, and--in this book--superheroes. But also, in this book, Bob is not our narrator; instead, we get his wife, Mo, in the fallout of a scene in the previous book (which we get from her POV here) with dire implications for their relationship…which has always been kind of a three-way between Bob, Mo, and Mo's soul-eating sentient violin, and this triangle has now come to a crisis. Plus there's superheroes.

Stross notes in the introduction that he never really read American superhero comics, so he had to pick a few brains about them, but the book really isn't about American superheroes either; he references the British superhero anthology series "Temps" (which I never did manage to read, since I only managed to find the second book, but now I feel like I should check out) as contrasted with the "Wild Cards" series.

All in all it's pretty decent, with lots of witty read-aloud bits, but the pacing is odd; there's a lot of plotlines, and some of them don't seem to progress for a long time. Some of them turn out to be red herrings, I guess, but overall it doesn't gel as well as it could. We don't see much of Bob (which makes sense since this isn't his book), though Mo is a perfectly fine protagonist. I'll be fine going back to Bob for the next book. If I can ever find it.

See, apparently this is the last book in the series I own right now, and probably the next one, The Nightmare Stacks, came and went while I was behind on reading it, and now it's out of print (and possibly never had a mass-market release at all, which is still my preferred format) and seems like it'll be hard to find in any physical format. I mean, I went on a site which allows you to search indie and second-hand bookstores, and the title didn't even come up on search. I have long been resisting switching wholeheartedly over to ebooks (a transition my wife has already made), but I can see that at some point I may have to get used to the fact that ebooks are just replacing mass-market paperbacks for the cheap release format. (I still can't manage to bring myself to spend as much as $8, let alone $12 or more, for an ebook, though. Like…what am I paying for? The publishing costs are minuscule compared to physical copies, and I expect that saving to be passed on to me. I guess I don't know if the extra is being passed on to the author in a non-self-published situation, but given our current corporate hellscape I'm gonna say probably not. Note: if you think this makes me a horrible person who hates writers to make money, please remember that I am married to a writer who I would love to make enough money that I don't have to work, but the publishing industry is horrible and they're the ones that actually have the capability to allow writers to make enough money to make a living, and they're not doing it, so I don't know what to tell you. I've bought thousands of books in my life, even if I don't go out of my way to buy the most expensive ones, because that's a good way to go broke. Get off my back, person I made up for this parenthetical aside.)

Martha Wells: System Collapse, completed January 28

I may be the last person in my house to have read Murderbot. My wife had already read some of Martha Wells earlier books (Raksura series, I want to say) before she read the Murderbot novells, and she loved them and read them to/got our kids to read them too. I eventually scheduled one in (novellas are good when I'm behind on my Goodreads challenge) and…it was okay, I guess? And I kept reading them because, well, more novellas. Last year I read the first novel-length story, Network Effect, and I liked it somewhat better than the novellas, for whatever reason.

I had been putting off the latest one for a little while, though, partly because of my Vorkosigan reread--I generally don't like books that are too close in genre too close together, and they're both kinda space opera-ish, though quite different kinds (Murderbot's future is more corporate-dominated), but next up I'm taking a break for a Dick Francis reread, so I thought I might as well put it in now. Though I've got to say that, since we have it as a physical hardcover as opposed to the digital novella ebooks, I'm really not a big fan of the texture of the dust jacket. Like, it is physically unpleasant to touch, being just a little bit rough. But not as bad as some I'd run across in the past few years, so I don't have to, like, take off the dust jacket to read it.

In the end I didn't like it as well as Network Effect, though I did like the middle bit where Murderbot becomes a Youtube influencer. The early part of the book, Murderbot is in a bit of a depressive state and not fun to read, like the first part of "Order of The Phoenix" or something. I guess if a character is too hypercompetent then nothing challenges them, but I wasn't a big fan of the emotional arc.

Dick Francis: Forfeit, completed January 31

I remember precisely where I was when I first heard of Dick Francis. See, I went to this convention in Edmonton in the summer of 1989, "ConText '89". It was an important convention--a reader-oriented rather than media-dominated SF/Fantasy convention, for one thing, and also it resulted in the formation of the first SF/Fantasy writer's organization in Canada, currently named SF Canada. Oh, and also, I met a cute girl there (Nicole, a YA author guest from northern Alberta), started dating, fell in love, got married, had three kids, and we're still married today.

I also saw this posting for a writing course out at a place called the Black Cat Guest Ranch, in the Rockies near Hinton, and decided to go. There I met Candas Jane Dorsey (who was the instructor for the course) and several other writers, and we later formed a writers' group called The Cult of Pain which is still going to this day. Anyway, I went out for a second course there, with Nicole coming along this time (though we may not have technically been dating and didn't share a room)--I think it was in mid-February sometime--and one evening we were all hanging out in the outdoor hot tub, watching snowflakes melt over our heads, and talking about books. And Candas and Nicole started rhapsodizing about this guy named Dick Francis. I said, "Who?" And they both told me I had to go read him, like, right away.

Dick Francis, apparently, was a former steeplechase jockey turned mystery/thriller writer. Now, mysteries and thrillers were not really my thing--I was into the SF & fantasy--but I supposed I was willing to try it. I was in university and trying to read other stuff outside my comfort zone, like Thomas Hardy and The Brothers Karamazov and William S. Burroughs, so why not. Plus, I wanted my girlfriend to like me. And the first one I picked up was one that one of my roommates had lying around, called Forfeit. It was pretty decent, and I went on to others--Nicole had a copy of Nerve, and I soon started to pick up more--and eventually read almost all of them (a few proved elusive, but I tracked down a copy of Smokescreen not long ago…).

Every book was concerned in some way with horse racing, but there was a wide variety--sometimes the main character was a jockey, but sometimes that was just their side hustle, and they had another profession, or sometimes they did something else like train horses or transport horses, or paint pictures of horses, or they didn't do anything about horses but the romantic interest did… He covered a lot of different professions over his books, they were usually quite interesting, and his characters were always very well-drawn. After his wife Mary (apparently an uncredited frequent collaborator and researcher) died, there was a gap of a few years before he started writing them with his son Felix. I think I read all of those ones, but after he died and Felix started writing solo novels, I haven't really kept up on those ones.

Instead, a few years ago I decided I was going to reread all the books, in publication order, interspersed with my series rereads as I was already doing with Discworld and Star Trek books. Forfeit is his seventh published book…and when I went to look for it on my shelf, I discovered that I actually didn't own a copy, and probably never had. I had just borrowed it from my roommate, and then given it back (a rookie mistake). Was it in print? Of course not, don't be silly. I had managed to find a used copy of Smokescreen online, as I mentioned, but for Forfeit there was only more expensive trade paperbacks, or $8 ebooks. They didn't even have it at the library! Except, well, they did…but I'd have to interlibrary loan it. I went back on forth on which to try to do, and eventually went ILL, and it came in for me at the library on the 20th. So there, overpriced ebooks. (And person I made up for the earlier parenthetical aside.)

Dick Francis novels have turned to be pretty rereadable, because they're not primarily mysteries of the sort where you don't remember which of the suspects is guilty; they're mysteries where the main character has to figure out who's behind the crimes and then avoid getting killed by them. Some of it is competency porn as they use their special skills to solve problems. And some of it just because of the engaging characters, which are maybe not quite all the way there in the earlier books (the ones I've reread so far are still books from the 60s, so the female characters could be more nuanced). In Forfeit what I recalled from that first read (some 34 years ago) was that the main character was a sportswriter, it started with one of his colleagues killing himself, and his wife was disabled and bedridden. (And one exciting scene in the middle of the book in which spoilers.) Though it turned out I was conflating two suicide openings (Nerve also starts with one, a gunshot suicide on the first page, whereas Forfeit's is more falling out of a window), and the exciting scene is missing an element I was sure was there.