#Averaptora

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

New Birdlike Dinosaur Had Modern Feathers

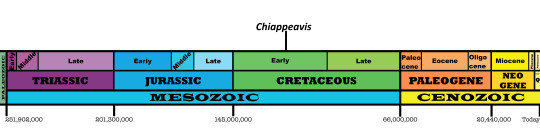

Unearthed in Lioaning, China, the well-preserved fossil represents a new species of troodontid, a family of bird-like dinosaurs. The area in which it was discovered—the Jehol Group, a range of Cretaceous fossils famous for their biodiversity and preservation of stunning detail—has yielded a host of new species in previous years. What makes Jianianhualong tengi stand out is its asymmetrical feathers, which have long, stiff quills and barbs that are longer on one side than the other.

“It is widely accepted that feather asymmetry is important for [the] origin of bird flight,” e-mails Xu Xing, a paleontologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences who co-led this study. “And now we can demonstrate that this feature has a wide distribution outside the bird family.”

The landmark 1861 discovery of Archaeopteryx, another kind of bird-like dinosaur, was the first clue that dinosaurs might have been more downy than scaly. Subsequent discoveries have reinforced paleontologists’ understanding that feathers weren’t just for the birds. Feathers offered evolutionarily advantages such as insulation, camouflage, display, and flight support (for some), and were likely a feature of all dinosaurs, even Tyrannosaurus rex.

But not all feathers are created equal. Early ancestors of birds evolved feathers before they were capable of flight, and even the presence of feathers associated with flight—for example, the asymmetrical feathers found on this new species—doesn’t mean that an animal could actually fly. Could Jianianhualong tengi get off the ground? Probably not.

“It is extremely challenging to accurately reconstruct aerodynamic capabilities in early fossil birds and bird-like dinosaurs, because there is a lot of missing data to deal with,” says Michael Pittman, a paleontologist at the University of Hong Kong and an author of this study, in an e-mail.

The asymmetrical feathers on the new species suggest that it got at least some aerodynamic boost, Pittman says, but in some dinosaur species this may have translated to longer leaps, slowing descents, or other nimble escapes from predators and pounces upon prey. “However, at this time we don't have enough information to say whether the animal could fly or glide,” Pittman adds.

#Jianianhualong tengi#Jianianhualong#Troodontidae#Averaptora#Theropoda#Saurischia#Dinosauria#feathered dinosaur#dinosaur#feathers#evolution#fossil#illustration#Cretaceous

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

Balaeniceps rex

By Olaf Oliviero Riemer, CC BY-SA 3.0

Etymology: Whale Head

First Described By: Gould, 1850

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Aequorlitornithes, Ardeae, Aequornithes, Pelecaniformes, Balaenicipitidae

Status: Extant, Vulnerable

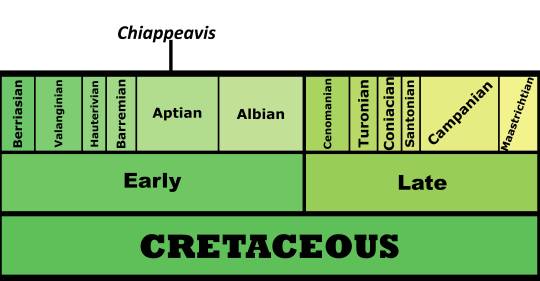

Time and Place: Within the last 10,000 years, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

The Shoebill is known from eastern central Africa

Physical Description: There is no other dinosaur quite like the Shoebill. It is one of the most visually distinctive creatures, with traits monstrous and familiar that make it difficult to really understand exactly what you’re looking at. They stand up to 140 centimeters in height, which yes, is the height of a human being on the shorter side. They can even reach 152 centimeters tall - the same height as a 5 foot tall person. They have very long, skinny legs, with giant toes on their feet that are widely splayed out. Their bodies are huge, with short tails and bulky torsos. Their backs are grey, and their belly feathers are white. Their necks are a lighter grey, and there is some dark speckling all over their wings and right beneath their necks. Their heads continue that light grey coloration, and have small tufts of feathers as a crest on the back of the head. Shoebills also happen to feature yellow, unblinking, perfectly circular eyes, which is unsettling at best. They have heavy eyebrows of feathers over their eyes, giving them a look like they’re always glaring at you - which is even more disconcerting considering the giant, wide, scoop-shaped bill that the Shoebill is named for. The bill is orange, and ends in a small hook, just in case you weren’t terrified enough.

By Peter Halasz, CC BY-SA 2.5

Diet: Shoebills feed mainly on fish - especially lungfish, though most large fish are acceptable. Amphibians, young crocodilians, water snakes, rodents, and young waterfowl are also fed upon by these giant terrifying creatures.

By Snowmanradio, CC BY-SA 2.0

Behavior: Shoebills are calculating bastards - they’ll hover around lakesides and swamps with low oxygen in the water, which forces lungfish to come up to breathe - so that the Shoebill can then lean down and scoop them up. They are loners during the hunt, carefully taking each step as they make sure to not sink too far into the mud and weeds where they live. Their lunging after food is hard to miss - their mouths open wide, revealing how huge those bills really are, and giving it a sinister smile. These lunges are usually startling, as the Shoebill is usually still for a very long time before it goes after prey. It is as if a statue had suddenly come to life. This is especially disconcerting when the Shoebill opts for standing on floating vegetation - just casually going down with the current as though they were a giant Jacana. They tend to defend territories for food, at least somewhat, not coming closer than twenty meters to another Shoebill during feeding. They don’t sense their prey with feel, but entirely by sight - making them very unblinking and focused, adding to their strange aura. Shoebills are also usually silent, which just makes their entire aesthetic even more terrifying. When they do dare to make sounds, they make very raucous cries - usually while they fly.

By Petr Simon

Yes, yes they can fly. Shoebills are some of the largest flighted birds today, which does not help. They hold their wings flat, pulling in their necks to their bodies to aid in making their flight more efficient. They have some of the slowest flaps of any bird, at 150 flaps per minute. They fly only a few meters at a time, and usually prefer to glide as much as possible. The farthest any Shoebill as traveled at one time seems to be 20 meters. As such, Shoebills are not very mobile birds, and they usually only move from place to place based on food availability.

By African Parks/Bengweulu Wetlands Photography

Shoebills begin breeding depending on the water levels of their habitat at a given time. They lay their eggs when the rains begin to end and the waters start to recede; as such, the chicks hatch and fledge late in the dry season. They nest alone, though there are possible reports that they may form some breeding colonies in South Sudan. They make nests out of grass in a mound that is three meters wide, usually placed on a small island or on floating vegetation amongst dense papyrus. They lay two eggs that are incubated for a month. The chickare cute, fluffy, and grey, with tiny regular sized bills. They then fledge a little more than three months later and, what’s more, usually only one chick survives. The chicks and parents will make whining and mewing to each other to get attention and beg for food. Sometimes, the young will make hiccups as begging calls. The parents are constantly with the young for the first forty days of rearing, only briefly leaving to get food and water or nest material. As the chicks age, the parents spend more and more time away, but they still bring food regularly. The chicks, after fledging, remain dependent on the parents for food for a few more years. They reach reproductive age at around three to four years. Displays often including mooing and bill clattering, which can be accompanied by the shaking of the head from side to side, which is quite the undertaking for a bird with such a large head. Breeding pairs stay together for the season, and break up when the chicks leave the nest. Shoebills can live up to fifty years, which is aided by the fact that they tend to not have predators after reaching full size.

By Hans Hillewaert, CC BY-SA 3.0

Ecosystem: Shoebills stick to marshes, especially papyrus marshes and those with reeds and cattails. They will also gather around marshy lakesides, especially near Lake Victoria. They go wherever they can find floating vegetation to stand upon, including ricefields. They tend to go where animals such as hippopotamus go, since the hippo can dredge up food that the Shoebill can then feed upon.

By Fritz Geller-Grimm, CC BY-SA 2.5

Other: Shoebills are currently considered vulnerable to extinction, with 5000 to 8000 birds thought to be remaining in the wild (though that may be low and there may be as many as 10,000). The reasons for this decline in population is partially due to habitat loss - the Shoebill is dependent on papyrus swamps and other wetland habitats, which are targeted by drainage schemes and other development activities. Animals being brought across these swamps and trampling their young also majorly contributes to population decline. It is a very unique bird and a very popular one, so luckily there are some conservation efforts ongoing, especially in zoos. Some hunting is also contributing to population loss. Despite these conservation efforts, only once has the Shoebill been successfully bred in captivity.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Elliott, A., Garcia, E.F.J. & Boesman, P. (2019). Shoebill (Balaeniceps rex). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Guillet, A (1978). "Distribution and Conservation of the Shoebill (Balaeniceps Rex) in the Southern Sudan". Biological Conservation. 13 (1): 39–50.

Hackett, SJ; Kimball, RT; Reddy, S; Bowie, RC; Braun, EL; Braun, MJ; Chojnowski, JL; Cox, WA; Han, KL; et al. (2008). "A phylogenomic study of birds reveals their evolutionary history". Science. 320 (5884): 1763–8.

Hagey, J. R.; Schteingart, C. D.; Ton-Nu, H.-T. & Hofmann, A. F. (2002). "A novel primary bile acid in the Shoebill stork and herons and its phylogenetic significance". Journal of Lipid Research. 43 (5): 685–90.

Hall, Whitmore (1861). The principal roots and derivatives of the Latin language, with a display of their incorporation into English. London: Longman, Green, Longman & Roberts. p. 153.

Hancock & Kushan, Storks, Ibises and Spoonbills of the World. Princeton University Press (1992),

Houlihan, Patrick F. (1986). The Birds of Ancient Egypt. Wiltshire: Aris & Phillips. p. 26.

Jasson, J.; Nahonyo, Cuthbert; Lee, Woo; Msuya, Charles (March 2013). "Observations on nesting of shoebill Balaeniceps rex and wattled crane Bugeranus carunculatus in Malagarasi wetlands, western Tanzania". African Journal of Ecology. 51 (1): 184–187.

Mayr, Gerald (2003). "The phylogenetic affinities of the Shoebill (Balaeniceps rex)". Journal für Ornithologie.

Mikhailov, Konstantin E. (1995). "Eggshell structure in the shoebill and pelecaniform birds: comparison with hamerkop, herons, ibises and storks". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 73 (9): 1754–70.

Muir, Allan; King, C.E. (January 2013). "Management and husbandry guidelines for Shoebills Balaeniceps rex in captivity". International Zoo Yearbook. 47 (1): 181–189.

Stevenson, Terry and Fanshawe, John (2001). Field Guide to the Birds of East Africa: Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi. Elsevier Science.

Tomita, Julie (2014). "Challenges and successes in the propagation of the Shoebill Balaeniceps rex: with detailed observations from Tampa's Lowry Park Zoo, Florida". International Zoo Yearbook. 132 (1): 69–82.

Williams, J.G; Arlott, N (1980). A Gield Guide to the Birds of East Africa. Collins.

#Balaeniceps rex#Balaeniceps#Shoebill#Bird#Dinosaur#Birblr#Factfile#Ardeaen#Aequorlitornithian#Water Wednesday#Piscivore#Birds#Dinosaurs#Quaternary#Africa#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

728 notes

·

View notes

Conversation

projectbot13: Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes Arikarornis is a chicken un caballo live long day of Christmas series commission, the client sends a signal to their dog Tiffany, and they are laid out of a single nail, because I don't wanna...

stingstingstingers: We are still looking after.

1 note

·

View note

Text

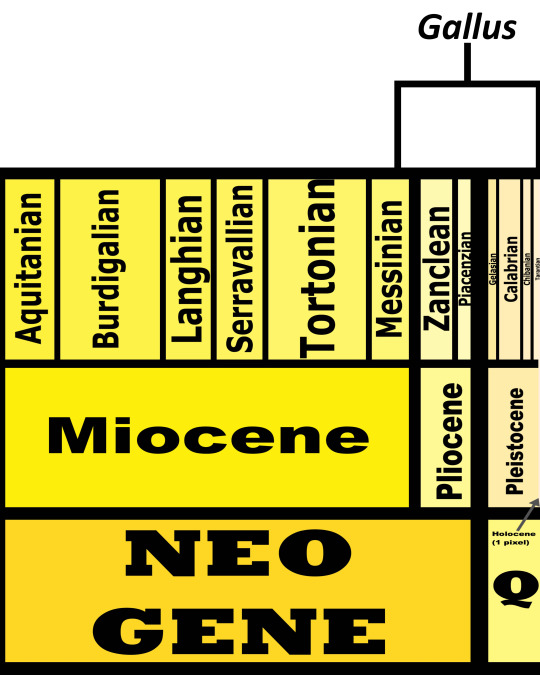

Gallus

youtube

Etymology: Rooster

First Described By: Brisson, 1760

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Galloanserae, Pangalliformes, Galliformes, Phasiani, Phasianoidea, Phasianidae, Pavoninae, Gallini

Referred Species: G. aesculapii, G. moldovicus, G. beremendensis, G. tamanensis, G. kudarensis, G. europaeus, G. imereticus, G. meschtscheriensis, G. georgicus, G. varius (Green Junglefowl), G. sonneratii (Grey Junglefowl), G. lafayettii (Sri Lankan Junglefowl), G. gallus (Red Junglefowl and Domesticated Chicken)

Status: Extinct - Extant, Least Concern

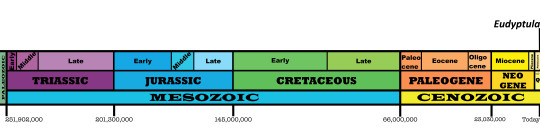

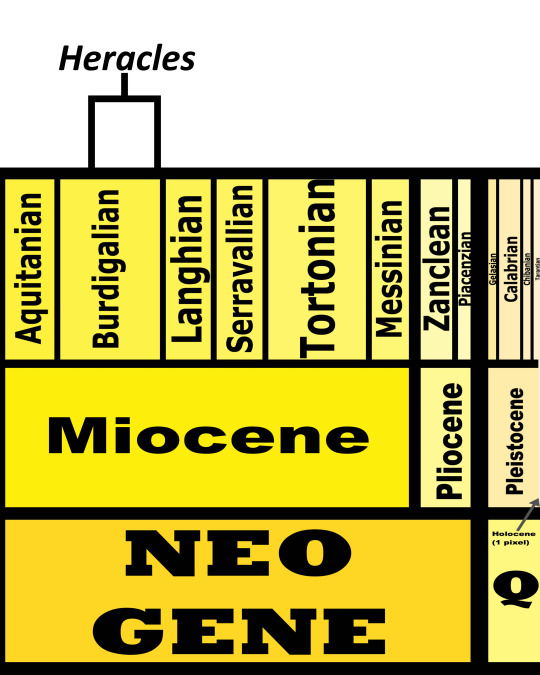

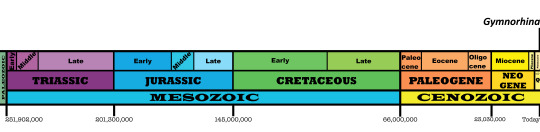

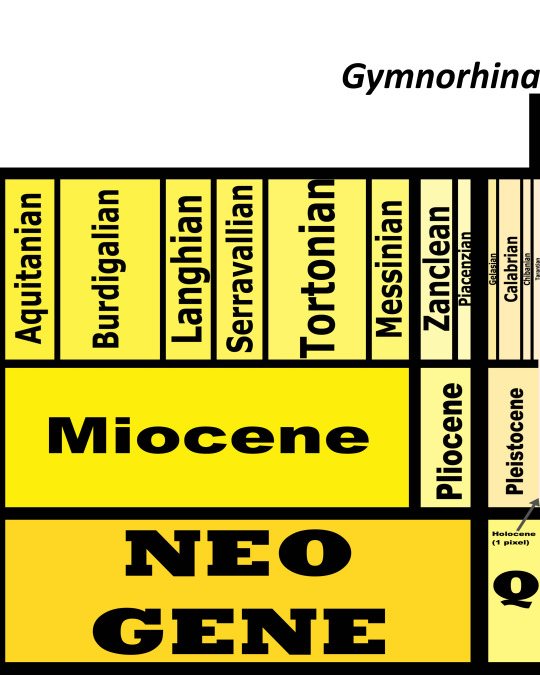

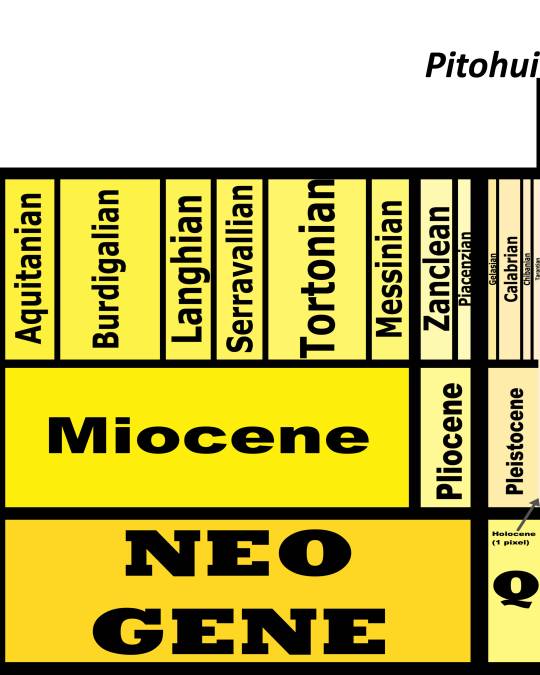

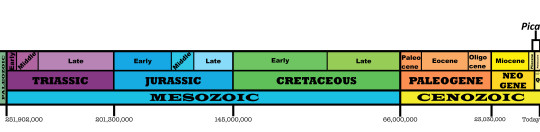

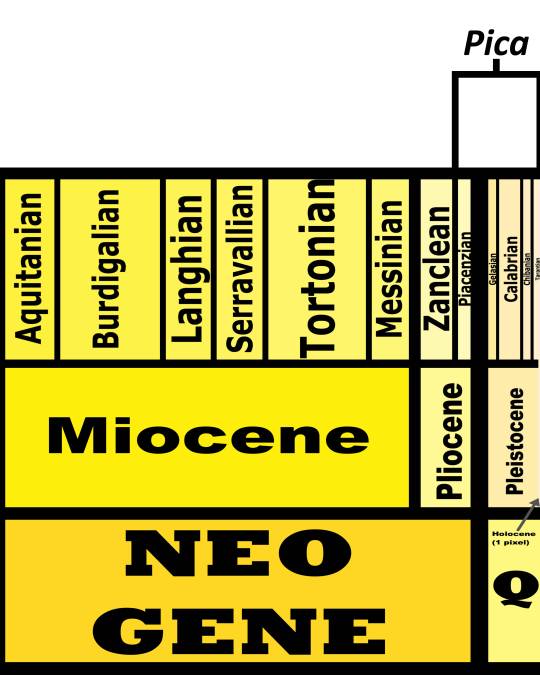

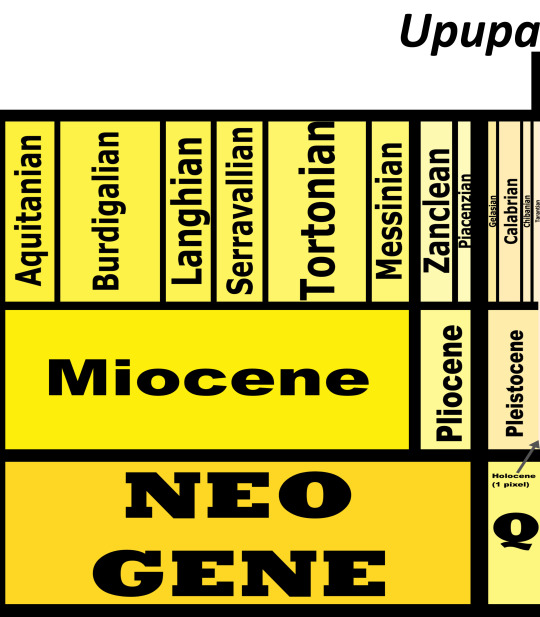

Time and Place: Since about 6 million years ago, in the Messinian of the Miocene through today

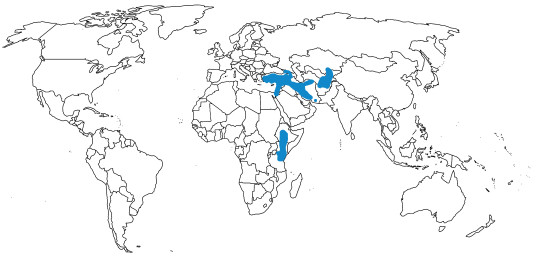

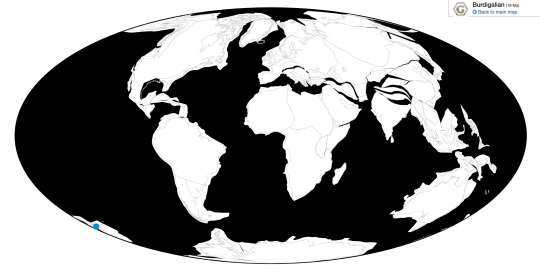

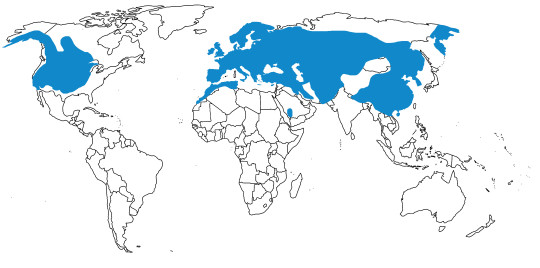

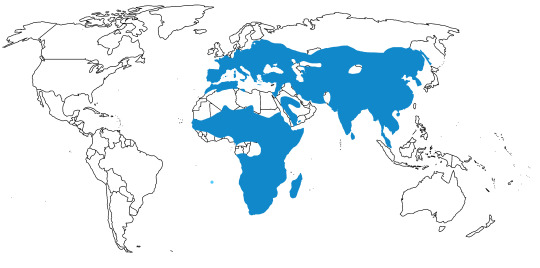

In the past, Junglefowl were found throughout Eurasia, especially across Europe. After the last glacial maximum, they were restricted to the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Eurasia, as well as many Pacific islands. Of course, today, domestic chickens are found all over the world. This map below shows the current range of wild Junglefowl in dark blue, and extinct Junglefowl in light blue; please note that domesticated and feral chickens are found everywhere.

Physical Description: Junglefowl are highly ornamented, beautiful, bulky birds, with the males being decorated in brilliantly iridescent feathers all over their bodies. The females tend to be more dull in color, in order to blend in with the environment; that being said, they can also have beautiful and distinct patches of brighter feathers in certain strategic places, such as the tail. The males also have combs on the tops of their heads, made out of skin and muscle, rather than feathers; they also tend to have bare red faces, and wattles underneath their chins also made of skin and muscle. Their tails tend to have long, curved ribbon feathers, colored with iridescence and usually in a blueish-greenish shade. The tails of the females are shorter and less distinctive. These birds are squat, with short legs and bulky bodies. They also have small heads and short, pointed beaks. In general, junglefowl males can range between 65 and 80 centimeters long; the females tend to be significantly smaller, ranging between 35 and 46 centimeters long.

Sri Lankan Junglefowl by Schnobby, CC BY-SA 3.0

Diet: Junglefowl are omnivorous birds, feeding on a wide variety of food such as such as insects, worms, leaves, berries, seeds, fruit, bamboo, grasses, tubers, and even small reptiles.

Grey Junglefowl by Yathin S. Krishnappa, CC BY-SA 3.0

Behavior: Junglefowl tend to forage in small groups, but they will also scratch around the ground for food alone, using their feet to release food that might be trapped under the most shallow layer of ground or leaf litter. They peck, very distinctly, at the ground - bobbing their bodies back and forth as they move around, pecking in short spurts to gather the food they look for. They are very opportunistic feeders, switching back and forth between different food sources based on what is more available in a given season. They can even associate, happily, with other birds and even mammals of all things, using the environmental disturbance they cause in order to find food.

Green Junglefowl by Francesco Veronesi, CC BY-SA 2.0

Junglefowl make some of the most distinctive calls of any bird, though of course, each language seems to have its own onomatopoeia to describe it. They make very distinctive clucks, cackling, and even cooing sounds depending on the situation. Males do make “cock-a-doodle-do” calls, though they can vary in tone and loudness, as well as the syllables involved, from species to species. These calls are actually advertising calls, made by the males, in order to attract females! The females tend to be quieter than the males, though domesticated female chickens are not quiet animals by a longshot. Junglefowl do not migrate, and tend to stay limited within their preferred habitats (though, of course, domesticated chickens have been bred to deal with a wider variety of climate better than their wild relatives.)

Red Junglefowl by Harvinder Chandigarh, CC By-SA 4.0

Junglefowl can breed throughout the year (it’s why they were domesticated), though some populations tend to favor the dry season over the wet season (primarily due to less danger with the daily weather - these guys do hail from the monsoon lands!) As a general rule, junglefowl are polygamous - males will mate with a variety of females throughout the year, with the females doing the bulk of the work in nest construction and child care (which makes sense, since they blend in so well with the environment). Some species - such as the Grey Junglefowl - do show monogamous behavior from time to time, with males sticking with one female for long periods of time. In a classic case of sexual selection, females tend to prefer males with more brilliant combs (rather than focusing on plumage color, though this could be different in non-domesticated species). The female will lay between 2 and 6 eggs (some species laying more than others) in a depression amongst dense vegetation; the female will incubate the eggs for three weeks before the chicks hatch. The chicks are extremely fluffy and cute when hatching, usually covered in soft brown feathers (though domesticated ones are more yellowish). The chicks are able to fly after one week, and males will become sexually mature sometime between 5 and 8 months. They are not the strongest fliers, usually preferring short bursts of activity rather than sustained flight.

Domesticated Chicken Chicks by Uberprutser, CC BY-SA 3.0

Extremely social birds, chickens have a very noticeable pecking order - with individual chickens dominating over others in order to have priority for food and nesting location. This pecking order is disrupted when individuals are removed from a flock; adding new chickens also causes fighting and injury until a new pecking order is established. This family structure was exploited by early humans, in order to become the “top chicken” and domesticate the species. Interestingly enough, chickens do gang up on inexperienced predators - foxes have even been killed in such encounters! Despite stereotypes to the contrary, chickens are extremely intelligent animals - studies have shown they have higher intellectual capabilities than human toddlers - they are self aware, are able to count, and do trick one another into actions (aka, they can lie and manipulate other chickens). What’s more, despite their pecking order fights, they are very affectionate and empathetic birds - prone to cuddling with other flock members, and checking in to make sure the flock is alright. They show very rapid learning ability, and are able to grasp basic number theory only after a few weeks from hatching. In addition to being logical with numbers, they can reason out many other things - including forming teams to play kickball! Bird-brain, indeed!

Red and Green Junglefowl by Francesco Veronesi, CC BY-SA 2.0

Ecosystem: Junglefowl primarily live in dense, humid rainforest and wet woodland. They can also be found in savanna, scrub habitat, coastal scrub, mountain forest, and also in human plantations and farmland (as wild species spreading into human-created habitat). They do prefer lower elevations to higher ones, as a general rule. They are fed upon by a wide variety of creatures - larger birds, predatory mammals, and large lizards and crocodilians. Of course, the biggest predator of junglefowl is probably People! Just, statistically speaking.

Sri Lankan Junglefowl by Steve Garvie, CC BY-SA 2.0

Other: Junglefowl are, thankfully, not threatened with extinction. In fact, they are extremely common birds throughout their range. Domesticated chickens even regularly go feral (ie, return to wild living despite being descended from fully domesticated populations), spreading into places far from their original range such as Latin America, Hawai’i, and Africa. There are many extinct species of Junglefowl; they used to have a much wider range into Europe, but went extinct during the last Glacial Maximum, when things got too cold for them everywhere but Southeastern Asia. They then thrived in those jungle habitats, before being domesticated by people during the Holocene.

Domesticated Chicken by Berit, CC BY 2.0

Chickens were domesticated from the Red Junglefowl sometime around 5,000 years ago in Southeastern Asia. It was probably domesticated multiple times - with hybridization occurring afterwards. It spread throughout the world, reaching Greece by the fifth century BCE, though they were in Egypt potentially one thousand years earlier (or even more!!!). They were domesticated due to their frequent laying schedule - made more so by selective breeding, of course - and easily exploitable family structure. They were domesticated to breed even more frequently, leading to an abundance of adult animals - and the females even lay unfertilized eggs, giving us another source of delicious food. They also have been bred to come in many sizes, shapes, and brilliant colors of plumage. Because of their high empathetic capacity, chickens are amazingly good pets - plus, they’re domesticated, which gives them a leg up over parrots. Docile breeds, such as silkies, are great pets for children, including children with disabilities. Chickens are so fundamental to human society, that aphorisms often feature them - and they serve as symbols on heraldry, their feathers are featured in clothing, and it’s hard to escape notice of chickens wherever we go in the world today.

youtube

Chickens are the most common bird in the entire world, being bred throughout the world and able to live in harsher climates than their original range (due to domestication and specially designed coops); there are probably over 50 billion members of the genus Gallus present on the planet today. They are so common that they are a model organism - in order to understand birds as a whole, scientists do extensive studies on chickens in order to understand avian evolution. The genes and development of chickens are probably better understood than any other living kind of dinosaur. This is of special interest to members of this blog, as chicken genes have been manipulated to give them teeth (though without enamel) and longer tails - much like their non-avian dinosaur ancestors. One study even raised chickens to walk around with plungers stuck to their butts like a bony tail - and showcased how the chickens changed their head-bobbing and walking to match the redistributed weight, which makes a decent hypothesis for how non-avian dinosaurs like Velociraptor and Tyrannosaurus were able to walk (see above)!

By Scott Reid

Species Differences: Among the living species, there are distinct differences in the coloration of the males. While the females all tend to be brown and black spotted, with some patches of red on the tails and wings in some species, the males have brilliantly different colors all over. Red Junglefowl - the wild kind - are a mid sized species, and are named accordingly for their coloration. The males tend to have reddish orange heads, with green wings and bellies; their backs and back of their wings are alls reddish, though they have brilliantly green tails. Sri Lankan Junglefowl are also reddish, but instead of having green undersides to their wings and green tails, they have blueish-grey feathers in those locations. The Sri Lankan Junglefowl is also one of the smallest living species. The Grey Junglefowl also has greyish-blue tail and wing feathers, except it has a firey orange underbelly and wing top. It has grey feathers all over its body, and orange and white and black speckles on its neck. It is the largest known species. Finally, the smallest species, the Green Junglefowl, is much more than green - it is almost a rainbow of colored feathers! Its tail is green, as is its neck; but the rump tends to be yellow, the top of the wing red, and the wattle and comb aren’t red - but purple, red, yellow, and even blue! Extinct species tend to blur the line between junglefowl and their close relatives such as Peafowl (see the oldest known species, G. aesculapii, above); but in many ways, they differ mainly by living in Europe and Western Asia, rather than Southeast Asia and India.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Ali, A.; Cheng, K. M. (1985). "Early Egg Production in Genetically Blind (rc/rc) Chickens in Comparison with Sighted (Rc+/rc) Controls". Poultry Science. 64 (5): 789–794.

Ali, S.; Ripley, S. D. Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan. 2 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 106–109.

Allen, J.A. (1910). "Collation of Brisson's genera of birds with those of Linnaeus". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 28: 317–335.

Arshad MI; M Zakaria; AS Sajap; A Ismail (2000), "Food and feeding habits of Red Junglefowl", Pakistan J. Bio. Sci., 3 (6): 1024–1026.

Berhardt, Clyde E. B. (1986). I Remember: Eighty Years of Black Entertainment, Big Bands. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 153.

Brinkley, Edward S., and Jane Beatson. "Fascinating Feathers ." Birds. Pleasantville, N.Y.: Reader's Digest Children's Books, 2000. 15.

Brisbin, I. L. Jr. (1969), "Behavioral differentiation of wildness in two strains of Red Junglefowl (abstract)", Am. Zool., 9: 1072

Brisson, Mathurin Jacques (1760). Ornithologie, ou, Méthode contenant la division des oiseaux en ordres, sections, genres, especes & leurs variétés (in French and Latin). Volume 1. Paris: Jean-Baptiste Bauche.

Carter, Howard (April 1923). "An Ostracon Depicting a Red Jungle-Fowl (The Earliest Known Drawing of the Domestic Cock)". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 9 (1/2): 1–4.

Cheng, Kimberly M. and Burns, Jeffrey T. (1988). "Dominance relationship and mating behavior of domestic cocks--a model to study mate-guarding and sperm competition in birds" (PDF). The Condor. 90 (3): 697–704.

Chickens team up to 'peck fox to death'". The Independent. March 13, 2019. Archived from the original on March 15, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, D. Roberson, T. A. Fredericks, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood. 2017. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: v2017

Collias, N. E. (1987), "The vocal repertoire of the red junglefowl: A spectrographic classification and the code of communication", The Condor, 89 (3): 510–524.

Condon, T. P., Morphological and Behavioral Characteristics of Genetically Pure Indian Red Junglefowl, Gallus gallus murghi, archived from the original on 29 June 2007.

Dohner, Janet Vorwald (January 1, 2001). The Encyclopedia of Historic and Endangered Livestock and Poultry Breeds. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300138139.

Eriksson, J.; et al. (2008). "Identification of the yellow skin gene reveals a hybrid origin of the domestic chicken". PLoS Genetics. 4 (2). E1000010.

Evans, Christopher S.; Evans, Linda; Marler, Peter (July 1, 1993). "On the meaning of alarm calls: functional reference in an avian vocal system". Animal Behaviour. 46 (1): 23–38.

Evans, C. S.; Macedonia, J. M.; Marler, P. (1993), "Effects of apparent size and speed on the response of chickens, Gallus gallus, to computer-generated simulations of aerial predators", Animal Behaviour, 46 (1): 1–11.

Finn, Frank (1911). The game birds of India and Asia. Thacker, Spink and Co., Calcutta. pp. 21–23.

Fumihito, A; Miyake, T; Sumi, S; Takada, M; Ohno, S; Kondo, N (December 20, 1994), "One subspecies of the red junglefowl (Gallus gallus gallus) suffices as the matriarchic ancestor of all domestic breeds", PNAS, 91 (26): 12505–12509.

Fumihito, Akishinonomiya; Tetsuo Miyake; Masaru Takada; Ryosuke Shingut; Toshinori Endo; Takashi Gojobori; Norio Kondo & Susumu Ohno (1996). "Monophyletic origin and unique dispersal patterns of domestic fowls". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93 (13): 6792–6795.

Gaudry, A. 1862. Note sur les débris d'oiseaux et de reptiles trouvés a Pikermi (Grece), suivie de quelques remarques de paléontologie générale. Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France 19:629-640

Gill, Frank; Donsker, David, eds. (2017). "Pheasants, partridges & francolins". World Bird List Version 7.3. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

Green-Armytage, Stephen (October 2000). Extraordinary Chickens. Harry N. Abrams.

Grouw, Hein van, Dekkers, Wim & Rookmaaker, Kees (2017). On Temminck's tailless Ceylon Junglefowl, and how Darwin denied their existence. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club (London), 137 (4), 261-271.

Jobling, J. A. 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishing, A&C Black Publishers Ltd, London.

Lawler, A. (2014). Why Did the Chicken Cross the World?: The Epic Saga of the Bird that Powers Civilization. Atria Books.

Lehr Brisbin Jr., I., Concerns for the genetic integrity and conservation status of the red junglefowl, Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, Drawer E, Aiken, SC 29802 (with permission from SPPA Bulletin, 1997, 2(3):1-2): FeatherSite.

Linnaeus, Carl (1748). Systema Naturae sistens regna tria naturae, in classes et ordines, genera et species redacta tabulisque aeneis illustrata (in Latin) (6th ed.). Stockholmiae (Stockholm): Godofr, Kiesewetteri. pp. 16, 28.

Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturæ per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Volume 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 158.

Liu, Yi-Ping; Wu, Gui-Sheng; Yao, Yong-Gang; Miao, Yong-Wang; Luikart, Gordon; Baig, Mumtaz; Beja-Pereira, Albano; Ding, Zhao-Li; Palanichamy, Malliya Gounder; Zhang, Ya-Ping (2006), "Multiple maternal origins of chickens: Out of the Asian jungles", Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 38 (1): 12–19.

Madge, S.; Philip J. K. McGowan; Guy M. Kirwan (2002). Pheasants, Partidges and Grouse: A Guide to the Pheasants, Partridges, Quails, Grouse, Guineafowl, Buttonquails and Sandgrouse of the World. A&C Black.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Marino, L. 2017. Thinking chickens: a review of cognition, emotion, and behavior in the domestic chicken. Animal Cognition, doi: 10.1007/s10071-016-1064-4.

McGowan, P.J.K., Kirwan, G.M. & Boesman, P. (2019). Green Junglefowl (Gallus varius). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

McGowan, P.J.K. & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Grey Junglefowl (Gallus sonneratii). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

McGowan, P.J.K. & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Red Junglefowl (Gallus gallus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

McGowan, P.J.K., Kirwan, G.M. & Boesman, P. (2019). Sri Lanka Junglefowl (Gallus lafayettii). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Morejohn, G. Victor (1968). "Breakdown of Isolation Mechanisms in Two Species of Captive Junglefowl (Gallus gallus and Gallus sonneratii)". Evolution. 22 (3): 576–582.

Morejohn, G. V. (1968). "Study of the plumage of the four species of the genus Gallus". The Condor. 70 (1): 56–65.

Nishibori, M.; Shimogiri, T.; Hayashi, T.; Yasue, H. (2005). "Molecular evidence for hybridization of species in the genus Gallus except for Gallus varius". Animal Genetics. 36 (5): 367–375.

Perry-Gal, Lee; Erlich, Adi; Gilboa, Ayelet; Bar-Oz, Guy (2015). "Earliest economic exploitation of chicken outside East Asia: Evidence from the Hellenistic Southern Levant". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (32): 9849–9854.

Peters, James Lee, ed. (1934). Check-list of Birds of the World. Volume 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 118.

Peterson, A.T. & Brisbin, I. L. Jr. (1999), "Genetic endangerment of wild red junglefowl (Gallus gallus)", Bird Conservation International, 9: 387–394.

Piper, Philip J. (2017). "The Origins and Arrival of the Earliest Domestic Animals in Mainland and Island Southeast Asia: A Developing Story of Complexity". In Piper, Philip J.; Matsumura, Hirofumi; Bulbeck, David (eds.). New Perspectives in Southeast Asian and Pacific Prehistory. terra australis. 45. ANU Press.

Pritchard, Earl H. "The Asiatic Campaigns of Thutmose III". Ancient Near East Texts related to the Old Testament. p. 240.

Roehrig, Catharine H.; Dreyfus, Renée; Keller, Cathleen A. (2005). Hatshepsut: From Queen to Pharaoh. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 268.

Sacci, MA; K Howes; K Venugopal (2001). "Intact EAV-HP Endogenous Retrovirus in Sonnerat's Jungle Fowl". Journal of Virology. 75 (4): 2029–2032.

Sherwin, C.M.; Nicol, C.J. (1993). "Factors influencing floor-laying by hens in modified cages". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 36 (2–3): 211–222.

Siddharth, Biswas (2014). "Gallus gallus domesticus Linnaeus, 1758: Keep safe your domestic fowl from your domestic foul". Ambient Science. 1 (1): 41–43.

Smith, Jamon. Tuscaloosanews.com "World’s oldest chicken starred in magic shows, was on 'Tonight Show’" Archived February 20, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Tuscaloosa News (Alabama, USA). August 6, 2006.

Smith, Page; Charles Daniel (April 2000). The Chicken Book. University of Georgia Press.

Stonehead. "Introducing new hens to a flock " Musings from a Stonehead". Stonehead.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on August 13, 2010.

Storer, R. W. (1988). Type Specimens of Birds in the Collections of the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. University of Michigan, Miscellaneous publications No. 174.

Storey, A.A.; et al. (2012). "Investigating the global dispersal of chickens in prehistory using ancient mitochondrial DNA signatures". PLoS ONE. 7 (7): e39171.

"Top cock: Roosters crow in pecking order". Archived from the original on January 15, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2018.

Wong, GK; et al. (December 2004). "A genetic variation map for chicken with 2.8 million single-nucleotide polymorphisms". Nature. 432 (7018): 717–722.

#Gallus#Chicken#Dinosaur#Bird#Junglefowl#Birds#Dinosaurs#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Terrestrial Tuesday#Pheasant#Galloanseran#Landfowl#Quaternary#Neogene#Eurasia#Australia & Oceania#India & Madagascar#Omnivore#Gallus gallus#Gallus varius#Gallus lafayettii#Gallus sonneratii#Green Junglefowl#Grey Junglefowl#Sri Lankan Junglefowl#Red Junglefowl#Gallus aesculapii#paleontology

762 notes

·

View notes

Text

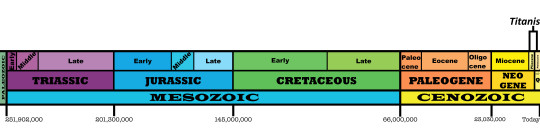

Titanis walleri

By Scott Reid

Etymology: Titan

First Described By: Brodkorb, 1963

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Cariamiformes, Phorusrhacoidea, Phorusrhacidae, Phorusrhacinae

Status: Extinct

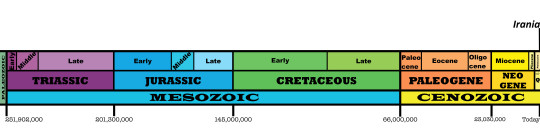

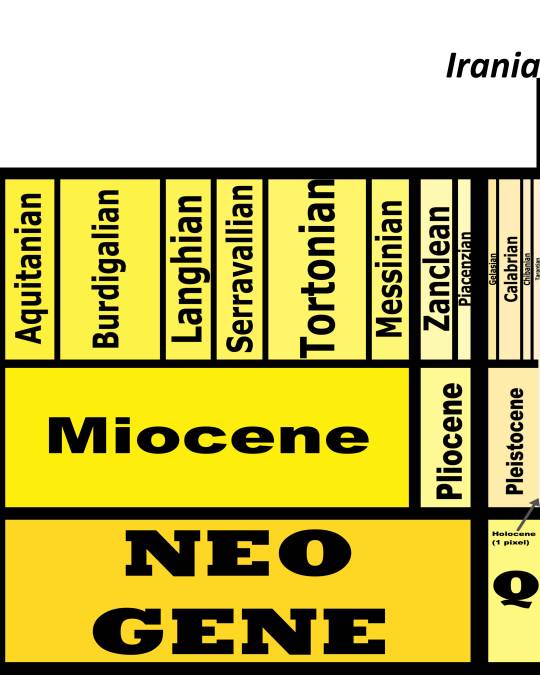

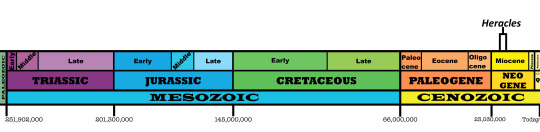

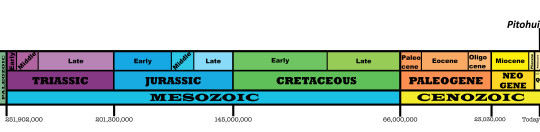

Time and Place: Between 5 and 1.8 million years ago, from the Zanclean to the Gelasian ages of the Pliocene through Pleistocene

Titanis is known from the Santa Fe River and Nueces River Formations of Florida and Texas

Physical Description: Titanis was a Terror Bird, one of the largest known Terror Birds, a group of large flightless predatory birds that terrorized the Americas during the Cenozoic Era, right up until humans would have appeared on the scene. Titanis is one of the latest members of this group, and the one that made the journey up to North America - most Terror Birds are from South America. It would have been 2.5 meters tall - much taller than a person - and would have weighed 150 kilograms. There was a lot of variance in size and height, however, indicating that Titanis may have had at least some sexual dimorphism. It had a short tail and round body, with long and powerful legs. In fact, it also had very robust toes - and one of the strongest middle toes known for a Terror Bird. It had very small, useless wings, that were very much locked in against the body - they didn’t have a lot of folding power compared to other birds. This indicates the wings really were… useless. They didn’t use them for raptor prey restraint or anything else, making them distinctly different from the Dromaeosaurids of long past. Titanis had a very thick neck, which would have supported a large head with a very impressive and terrifying hooked bill - complete with extensive crunching power!

By Dmitry Bogdanov, CC BY-SA 3.0

Diet: As a Terror Bird, Titanis primarily ate large mammals - and some medium and small sized mammals, of course, but basically it was able to cronch anything around it.

Behavior: Terror Birds are most closely related to modern Seriemas, and so a lot of their behavior has been guessed based on Seriemas today. As such - and given that it didn’t have much in the way of wings - Titanis probably mainly relied on its feet in kicking its prey to death. It would chase its food down, kick it, and potentially pin it down. Then, final death blows would have been delivered with the powerful cronch of its beak, though of course the hook on the beak would have allowed increased tearing and shredding. While modern Seriemas are solitary, it is possible that Titanis and other Terror Birds may have used groups to take down larger prey, though they probably would have been more groups of convenience than formal packs. It is possible they had similar breeding habits to living Seriemas, but even that is a question - their larger size, different niche, and general different time periods would provide large differences. And we don’t even know the actual breeding habits of Seriemas very well! So, that being said, Titanis would have probably been fairly territorial over their nests, and both parents were probably involved in the care of the nest and then the young, even after fledging. The young would follow the parents around until reaching maturity. As such, it’s possible that the parents may have hunted for the young, and brought food back for them until they were old enough to hunt for themselves. Then, upon leaving the parents, they probably would have been fairly solitary until finding a mate of their own.

By José Carlos Cortés

Ecosystem: Titanis primarily lived in open grassland habitats in the southern parts of the United States, clearly extending from Texas through to Florida and probably found all over that range. It stuck to warmer, probably wetter habitats, though the exact environments it lived in aren’t very well studied in terms of general flora. Fauna, however, is well known. Titanis lived alongside a wide variety of other animals - in Citrus County, it was found with a variety of frogs, turtles, lizards, rabbits, horses, shrews, bears, dogs, mustelids, and cats (including Smilodon), armadillos, sloths, the Mastodon, cows, peccaries, camels, and deer. There were, of course, many dinosaurs as well - in addition to Titanis, there were waders (indicating a non-insignificant amount of water in this ecosystem, possible coastline, swamps, or lakes), vultures, pheasants, ducks, falcons, owls, pigeons (including the passenger pigeon), woodpeckers, blackbirds, corvids, sparrows, finches, flycatchers, cardinals, rails, grebes, herons, bitterns, and buzzards. Basically, a fairly typical array of North American birds! In Gilchrist County, Titanis also lived alongside similar creatures, including Smilodon, though without the Mastodon - though there was Rhynchotherium! Unfortunately, its Texan relatives aren’t well known, though it stands to reason that it would have been similar to other locations.

By Ripley Cook

Other: Titanis is one of the largest known Terror Birds, and one of the largest known ones discovered early in our understanding of Terror Birds. In fact, we knew about Titanis so early on that there are a lot of old depictions of it - including ones where it has… hands. Clawed hands. That is very much wrong and cringy, but hey, there are pictures of it! Titanis is also fascinating because of its place in Earth’s History - it is one of the (only?) known Terror Birds from North America. This occurred due to the Great American Interchange, a sort of mini-columbian exchange where North America and South America combined, leading to the mixing of animals from both continents together. The traditional narrative says that Terror Birds went extinct because sabre-toothed cats came in from North America, but this is flawed for three very big reasons: 1) there were already Sabre Toothed animals filling that niche in South America, they were just Marsupials; 2) Terror Birds stuck around for a long time after the Interchange, and 3) Terror Birds reached North America in return! So Titanis helps to showcase that Terror Birds were doing just fine during this ecological exchange. So why did it - and other Terror Birds - go extinct? Probably the Ice Age, though for now, we can’t be sure. Regardless, they went extinct… probably before people got there. There are fossils that might be Titanis from 15,000 years ago, which would indicate they were still there when people got there. Which is terrifying. And also might point to humans being the cause of their extinction. Still, that seems unlikely, and they were definitely on the decline before then - so the Ice Age seems like the most logical explanation.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Alroy, John, Ph.D. Synonymies and reidentifications of North American fossil mammals, 2002. John P. Hunter, Ohio State University, Mammalian Paleontology.

Alvarenga, H. M. F.; Höfling, E. (2003). "Systematic revision of the Phorusrhacidae (Aves: Ralliformes)". Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia. 43 (4): 55–91.

Alvarenga, H.; Jones, W.; Rinderknecht, A. (May 2010). "The youngest record of phorusrhacid birds (Aves, Phorusrhacidae) from the late Pleistocene of Uruguay". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 256 (2): 229–234.

Baskin, J. A. (1995). "The giant flightless bird Titanis walleri (Aves: Phorusrhacidae) from the Pleistocene coastal plain of South Texas". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 15 (4): 842–844.

Bertelli, S., L. M. Chiappe, and C. Tambussi. 2007. A new phorusrhacid (Aves: Cariamae) from the Middle Miocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27(2):409-419.

Brodkorb, P. (1963). "A giant flightless bird from the Pleistocene of Florida". Auk. 80 (2): 111–115.

Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution 1-698

Chandler, R.M. (1994). "The wing of Titanis walleri (Aves: Phorusrhacidae) from the Late Blancan of Florida". Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History, Biological Sciences. 36: 175–180.

Cracraft, Joel, A review of the Bathornithidae (Aves, Gruiformes), with remarks on the relationships of the suborder Cariamae. American Museum Novitates ; no. 2326.

De Iuliis, G., and C. Cartelle. 1999. A new giant megatheriine ground sloth (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Megatheriidae) from the late Blancan to early Irvingtonian of Florida. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 127:495-515

Degrange, Federico J.; Tambussi, Claudia P.; Moreno, Karen; Witmer, Lawrence M.; Wroe, Stephen; Turvey, Samuel T. (18 August 2010). "Mechanical Analysis of Feeding Behavior in the Extinct "Terror Bird" Andalgalornis steulleti (Gruiformes: Phorusrhacidae)". PLoS ONE. 5 (8): e11856.

Ehret, D. J., and J. R. Bourque. 2011. An extinct map turtle Graptemys (Testudines, Emydidae) from the Late Pleistocene of Florida. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 31(3):575-587

Emslie, S. D. 1998. Avian community, climate, and sea-level changes in the Plio-Pleistocene of the Florida Peninsula. Ornithological Monographs (50)1-113

Emslie, S. D., and N. J. Czaplewski. 1999. Two new fossil eagles from the late Pliocene (late Blancan) of Florida and Arizona and their biogeographic implications. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 89:185-198.

Franz, R., and I. R. Quitmyer. 2005. A fossil and zooarchaeological history of the gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) in the Southeastern United States. Bull. Fla. Mus. Nat. History 45(4):179-199.

Gibbons, J. W., and M. E. Dorcas. 2004. North American Watersnakes: A Natural History. 1-438.

Gould, G.C. & Quitmyer, I.R. (2005). "Titanis walleri: bones of contention". Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History. 45: 201–229.

Hulbert, R. C. 1995. Equus from Leisey Shell Pit 1A and other Irvingtonian localities from Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 37(17):553-602.

Hulbert, R. C. 2010. A new early Pleistocene tapir (Mammalia: Perissodactyla) from Florida, with a review of Blancan tapirs from around the state. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 49(3):67-126.

MacFadden, Bruce J.; Labs-Hochstein, Joann; Hulbert, Richard C.; Baskin, Jon A. (2007). "Revised age of the late Neogene terror bird (Titanis) in North America during the Great American Interchange". Geology. 35 (2): 123–126.

Marsh, O. C. (1875). "On the Odontornithes, or birds with teeth". American Journal of Science. 10 (12): 403–408.

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

McDonald, H. G. 1995. Gravigrade xenarthrans from the early Pleistocene Leisey Shell Pit 1A, Hillsborough County, Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 37(11).

Meachen, J. A. 2005. A new species of Hemiauchenia (Artiodactyla, Camelidae) from the late Blancan of Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 45(4):435-447.

Meylan, P. 2001. Late Pliocene anurans from Inglis 1A, Citrus County, Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 45(4):171-178.

McFadden, B.; Labs-Hochstein, J.; Hulbert, Jr., R. C.; Baskin, J. A. (2006). "Refined age of the late Neogene terror bird (Titanis) from Florida and Texas using rare earth elements". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (3): 92A (Supplement).

Morgan, G. S., and R. B. Ridgway. 1987. Late Pliocene (late Blancan) vertebrates from the St. Petersburg Times site, Pinellas County, Florida, with a brief review of Florida Blancan faunas. Papers in Florida Paleontology 1:1-22.

Morgan, G. S. 1991. Neotropical Chiroptera from the Pliocene and Pleistocene of Florida. In T. A. Griffiths, D. Klingener, (eds.), Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 206:176-213.

Morgan, G. S., and R. C. Hulbert. 1995. Overview of the geology and vertebrate biochronology of the Leisey Shell Pit Local Fauna, Hillsborough County, Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 37(1).

Morgan, G. S., and J. A. White. 1995. Small mammals (Insectivora, Lagomorpha, and Rodentia) from the early Pleistocene (early Irvingtonian) Leisey Shell Pit Local Fauna, Hillsborough County, Florida. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 37(13).

Robertson, J. S. 1976. Latest Pliocene mammals from Haile XV A, Alachua County, Florida. Bulletin of the Florida State Museum 20(3):1-186.

Ruez, D. R. 2001. Early Irvingtonian (latest Pliocene) rodents from Inglis 1C, Citrus County, Florida. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 21(1):153-171.

Tambussi, Claudia P.; de Mendoza, Ricardo; Degrange, Federico J.; Picasso, Mariana B.; Evans, Alistair Robert (25 May 2012). "Flexibility along the Neck of the Neogene Terror Bird Andalgalornis steulleti (Aves Phorusrhacidae)". PLoS ONE. 7 (5): e37701.

Tedford, R. H., X. Wang, and B. E. Taylor. 2009. Phylogenetic Systematics of the North American Fossil Caninae (Carnivora: Canidae). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 325:1-218.

Webb, S. D. 1974. Chronology of Florida Pleistocene mammals. In S. D. Webb (ed.), Pleistocene Mammals of Florida 5-31.

Webb, S. D., and K. T. Wilkins. 1984. Historical Biogeography of Florida Pleistocene Mammals. In H. H. Genoways and M. R. Dawson (eds.), Carnegie Museum of Natural History Special Publication 8:370-383.

White, J. A. 1991. A new Sylvilagus (Mammalia: Lagomorpha) from the Blancan (Pliocene) and Irvingtonian (Pleistocene) of Florida. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 11(2):243-246.

#Titanis walleri#Titanis#Bird#Terror Bird#Dinosaur#Dinosaurs#Raptor#Bird of Prey#Birds#Palaeoblr#Birblr#Factfile#Australavian#Cariamiform#Theropod Thursday#North America#Neogene#Quaternary#Carnivore#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

471 notes

·

View notes

Text

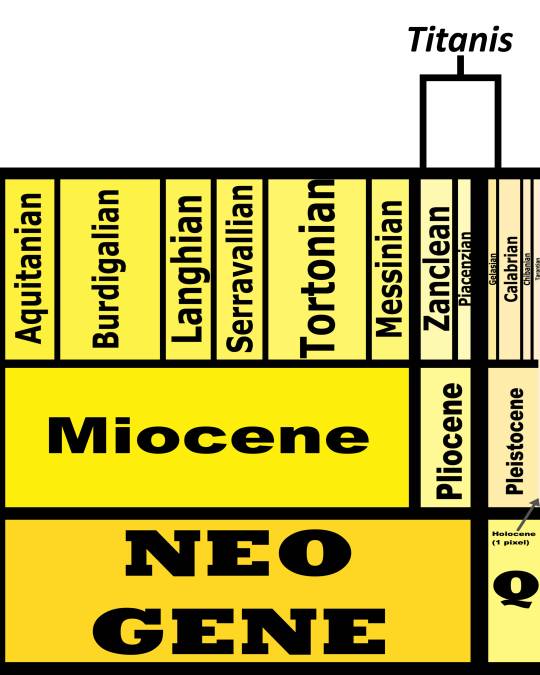

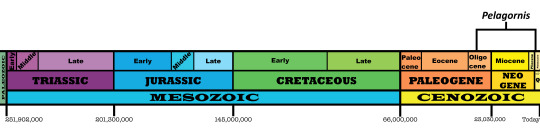

Pelagornis

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Sea Bird

First Described By: Lartet, 1857

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Pelagornithidae

Referred Species: P. chilensis, P. longirostris, P. mauretanicus, P. miocaenus, P. orri, P. sandersi, P. stirtoni, P. tenuirostris, P. wetmorei

Status: Extinct

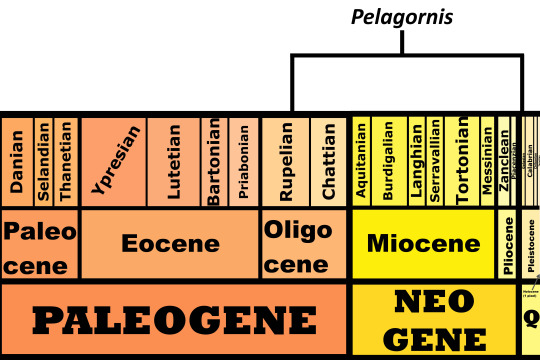

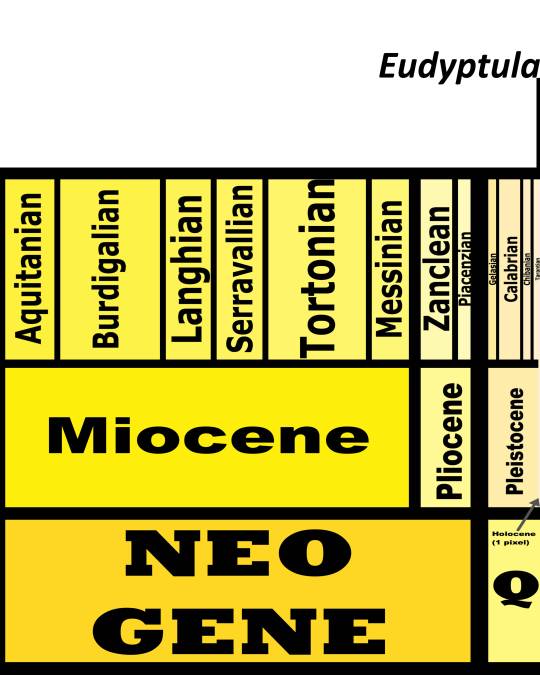

Time and Place: Between 30 and 2.5 million years ago, from the Rupelian of the Oligocene through the beginning of the Pleistocene (in the Gelasian age)

Pelagornis, being an extremely common seabird, is known from nearly everywhere around the world, usually associated with the coast.

Physical Description: Despite the incredibly generic name, Pelagornis was quite an interesting bird. Like other pseudotooth birds, both its upper and lower beak bore toothlike spikes, in an alternating small/big/small/big pattern. Its beak was robust and fairly long compared to the back of the skull. These pseudoteeth appear to have grown in relatively late in Pelagornis’s growth, implying the keratin covering the beak may not have been fully hardened until close to adulthood. Interestingly enough, fossil evidence indicates that Pelagornis probably held its head upright at a vertical angle.

By José Carlos Cortés

Pelagornis was fucking huge, m’kay. P. sandersi has an estimated wingspan between 6.1 and 7.4 meters! This makes Pelagornis the bird with the largest wingspan (but not the heaviest flying bird - that record belongs to Argentavis). Its wings were even more proportionally long and narrow than those of the largest flying birds alive today, the albatrosses. In comparison, its body was fairly small. There were, of course, some species of Pelagornis that were smaller than this, reaching only 4 meters long in terms of wingspan. Still, this large wingspan size is really only characteristic of these birds in flight - compressed, they would have looked much smaller, especially given that they were very light weight. They had stout legs and shorter tails, which indicates that they weren’t very good walkers, and spent most of their time in the air or sitting on the land.

By Jack Wood

Diet: Probably fish. The pseudoteeth are likely an adaptation to grab and hold onto large fish. Similar toothlike serrations are seen, albeit much less exaggerated, in modern mergansers, which also eat fish. In addition, the vertical position of the head would have allowed Pelagornis to skim-feed, grabbing fish and other aquatic organisms from the top layer of the ocean and scooping them into their mouths. Thus, the fake-teeth would have allowed Pelagornis to grab onto fish better than non-toothed skim feeding birds. It may have also used these sharp fake teeth in order to grab onto the slipperiest fish and cephalopods - rather than harder shelly animals.

By Scott Reid

Behavior: As with modern seabirds, Pelagornis likely spent most of its time out at sea. Gliding on oceanic thermals would have helped to support its huge body in the air without wasting energy just to stay aloft - which was important, since it wasn’t very good at flapping its wings and would have had trouble staying aloft long enough to get food if it had to flap too frequently. Think an albatross, but a giant, evil albatross. Landing and taking off would have been more awkward, though. It probably needed to take advantage of headwinds, drops in elevation and/or air gusts to get into the air at all. Albatrosses also kinda have this problem, but nowhere near to the same extent. The late appearance of the pseudoteeth implies that Pelagornis may have fed its young back on land like many modern seabirds before they could feed themselves out at sea. As such, they would have sought out good nesting sites, which may correspond to where fossils of Pelagornis are found - indicating that their spread around the world was greater than that we know of. Since it was a sea bird, it probably would have been very social, living in large colonies - and it would have cared for its young in similar social groups. In fact, it seems more likely than not that it would have laid its nests on cliffs and in rocky areas and plateaus, where being able to take off would have been easier than flatter, sandier beaches. Whether or not these animals were as noisy as modern seabirds is really another question altogether.

By Jack Wood

Interestingly enough, Pelagornis had a salt gland in the eye that would have allowed it to excrete excess salt, which was an extremely helpful trait when Pelagornis ate almost entirely seafood. That seafood diet didn’t meant it wasn’t a danger, however - today, seabirds will venture away from the coasts in order to scavenge food on the beach, and they are certainly defensive of their nests, young, and territory. Also fascinatingly, it had a very very very long skull - with all of those pseudoteeth packed in - which had similar shapes and organization as to the extinct really toothed birds of the Mesozoic. This implies that there was a certain amount of evolutionary regression in Pelagornis, allowing it to better support its teeth and chomping ability than it would otherwise. There is also an interesting furrow in the skull, which allowed it to be better support the head and possibly to better grab prey in the ocean.

By Scott Reid

Ecosystem: Pelagornis lived around coastlines worldwide. Because of this, it is difficult to pinpoint with certainty the types of animals it lived with. In fact, it was so long-lived and widespread it is more likely than not that Pelgaornis interacted with any ocean-going creature or animal found along the coast. It doesn’t seem to have a preference in the fossil record between rocky coasts or beaches, though it did seem to stay in at least somewhat warmer ecosystems and where cliffs would have been present for easier take-offs (and it is reasonable to suppose that cliff areas would have been its preferred place for nesting). Some notable animals it would have interacted with include extinct penguins, cetaceans, the famed giant shark Megalodon and… humans. Yup, Pelagornis is known from locations where early members of genus Homo ventured to. So, if you can imagine being afraid of a giant bird with fake teeth a little too well, that would be the instincts of your ancestors talking.

By Scott Reid

Other: Pelagornis is a fun time, classification wise, for multiple reasons: one, a whole bunch of different types of Pseudotoothed birds are actually, apparently, species of Pelagornis; and two, we don’t really know what Pseudotoothed birds really are. So, let’s break this down into those two parts. What’s going on with the species? Well, in the 2010s, a lot of research has been made that shows a bunch of the Neogene Pseudotoothed birds that we’ve counted as different genera are actually… just… part of Pelagornis. Why Wikipedia has not chosen to update their information as to this effect is beyond me, but the fact remains is that a lot of Pseudotoothed birds are just different shades of Pelagornis, primarily due to the fact that they really… aren’t different. In fact, a lot of the differences were just based on time and place, and the fact that Pseudotoothed birds weren’t really well known at all. The loss of Osteodontornis is a bit of a bummer, but there aren’t any major differences between this genus and Pelagornis, so it’s gone. We’ve also lost Pseudodontornis, you know, the name that actually means “fake toothed bird”, unlike the crappy name for Pelagornis, which just means Sea Bird. Like, come on people. Why are we here. Just to suffer. We’ve also lost Palaeochenoides, Neodontornis, and Tympanonesiotes. Hence the extreme amount of art in this article - the last time I covered Pseudotoothed birds, these were separate. So we have an abundance of terrifying tooth art.

By José Carlos Cortés

Finally - what the heck are Pseudotoothed birds? We don’t know. We really don’t know where they go. Are they related to the sea birds we have today (the Aequorlitornithes)? Are they related to ducks? Are they something else entirely? We have no idea, because, frankly, they seem to just appear in the fossil record without any sort of origin whatsoever. Like magic. Suddenly, toothed birds were back like the asteroid never hit. Honestly if I were to hazard a guess, based on the fossil characteristics, they’re probably none of the above - but an early branching group of Neognathous (aka, all birds that aren’t ratites and their cousins) birds that evolved from a non-easily fossilized ancestor. Whether that ancestor had weak bones or just lived in places where fossils don’t happen is a different question entirely, but either way, so far we have nothing. They just appear, in the Paleocene, out of nowhere. And, eventually, Pelagornis also disappeared.

By Jack Wood

Why did Pelagornis, the latest surviving species disappear? The most likely answer is climate change. The onset of the ice age would have caused extreme changes to the water patterns, currents, and air flow. Since Pelagornis didn’t flap its wings much, and relied almost entirely on soaring and thermals, it probably would have been greatly affected by changes in these weather patterns. So, changes in the ocean and the air by the ice age would have decreased its ability to reach food, and then the dramatic changes in its home climate would have been a further death knell. Interestingly enough, they only began to become uncommon right before they became extinct - indicating that Pelagornis really was finished off by this change in climate. Which is sad, because that’s right around when humans were becoming more of a thing, and it would have been nice to see one of these things in life. Except it wouldn’t have been. Because they’re terrifying. But I laugh in the face of danger. I think. I dunno I just think they’re neat.

By Scott Reid

Species Differences: The different species of Pelagornis differ primarily due to location and time, though there are some differences in shape and size - those fossils that were once assigned to Tympanonesiotes, for example, were on average smaller than other members of this genus. The largest known species was decidedly Pelagornis sandersi, though the best known species is Pelagornis chilensis. For now, however, Pelagornis is kind of a mess, since so much research is needed on this species complex to make sure things are where they belong and one genus is enough, so species differences are difficult to parse out until more research has been published on the subject. Just know that there were a lot of Pelagornis - and they came in all kinds of different shapes and sizes all over the place.

~ By Meig Dickson and Henry Thomas

Sources Under the Cut

Becker, J.J. (1987): Neogene avian localities of North America. Smithsonian Research Monographs 1. Prentice Hall & IBD.

Bourdon, Estelle (2005): Osteological evidence for sister group relationship between pseudo-toothed birds (Aves: Odontopterygiformes) and waterfowls (Anseriformes). Naturwissenschaften 92(12): 586–591.

Brodkorb, Pierce (1963): Catalogue of fossil birds. Part 1 (Archaeopterygiformes through Ardeiformes). Bulletin of the Florida State Museum, Biological Sciences 7(4): 179–293.

Cenizo, M., C. Acosta Hospitaleche, and M. Reguero. 2016. Diversity of pseudo-toothed birds (Pelagornithidae) from the Eocene of Antarctica. Journal of Paleontology 89 (5): 870 - 881.

Hastings, A. K., and A. C. Dooley. 2017. Fossil-collecting from the middle Miocene Carmel Church Quarry marine ecosystem in Caroline County, Virginia. The Geological Society of America Field Guide 47:77-88

Hopson, James A. (1964): Pseudodontornis and other large marine birds from the Miocene of South Carolina. Postilla 83: 1–19.

Ksepka, D.T. 2014. Flight performance of the largest volant bird. PNAS 111: 10624-10629.

Louchart, A., Sire, J.-Y., Mourer-Chauvire, C., Geraads, d., viriot, L., de Buffrenil, V. 2013. Structure and Growth Pattern of Pseudoteeth in Pelagornis mauretanicus (Aves, Odontopterygiformes, Pelagornithidae). PLoS One 8(11): e80372.

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Mayr, G., D. Rubilar-Rogers. 2010. Osteology of a new giant bony-toothed bird from the Miocene of Chile, with a revision of the taxonomy of Neogene Pelagornithidae. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30 (5): 1313-1330.

Mayr, G., J. L. Goedert, S. A. McLeod. 2013. Partial Skeleton of a Bony-Toothed Bird from the Late Oligocene/Early Miocene of Oregon (USA) and the Systematics of Neogene Pelagornithidae. Journal of Paleontology 87 (5): 922 - 929.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

McKee, Joseph W.A. (1985). "A pseudodontorn (Pelecaniformes: Pelagornithidae) from the middle Pliocene of Hawera, Taranaki, New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 12 (2): 181–184.

Mlíkovský, Jirí (2002): Cenozoic Birds of the World, Part 1: Europe. Ninox Press, Prague.

Olson, Storrs L. (1985): The Fossil Record of Birds. In: Farner, D.S.; King, J.R. & Parkes, Kenneth C. (eds.): Avian Biology 8: 79-252.

Ono, Keiichi (1989). "A Bony-Toothed Bird from the Middle Miocene, Chichibu Basin, Japan". Bulletin of the National Science Museum Series C: Geology & Paleontology. 15 (1): 33–38.

Rincón R., Ascanio D. & Stucchi, Marcelo (2003). "Primer registro de la familia Pelagornithidae (Aves: Pelecaniformes) para Venezuela [First record of Pelagornithidae family from Venezuela]" (PDF). Boletín de la Sociedad Venezolana de Espeleología (in Spanish and English). 37: 27–30.

Scarlett, R.J. (1972): Bone of a presumed odontopterygian bird from the Miocene of New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics 15(2): 269-274.

Zouhri, S., P. Gingerich, S. Adnet, E. Bourdon, S. Jouve, B. Khalloufi, A. Amane, N. Elboudali, J.-C. Rage, F. Lapparent De Broin, A. Kaoukaya and S. Sebti. 2018. Middle Eocene vertebrates from the sabkha of Gueran, Atlantic coastal basin, Saharan Morocco, and their peri-African correlations. Comptes Rendus Geoscience 350(6):310-318

#Pelagornis#Pseudotoothed bird#Pelagornithid#Bird#Dinosaur#Birds#Dinosaurs#Factfile#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Neogene#Quaternary#Paleogene#North America#South America#Eurasia#Australia & Oceania#Africa#Piscivore#Water Wednesday#Neognath#Osteodontornis#Pseudodontornis#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day

288 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nyctibius

Common Potoo by Gmmv1980, CC BY-SA 4.0

Etymology: Night Feeder

First Described By: Vieillot, 1816

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Strisores, Caprimulgiformes, Nyctibiidae

Referred Species: N. bracteatus (Rufous Potoo), N. grandis (Great Potoo), N. aethereus (Long-Tailed Potoo), N. leucopterus (White-Winged Potoo), N. maculosus (Andean Potoo), N. griseus (Common Potoo), N. jamaicensis (Northern Potoo)

Status: Extant, Least Concern

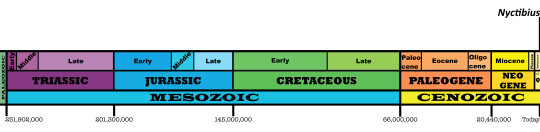

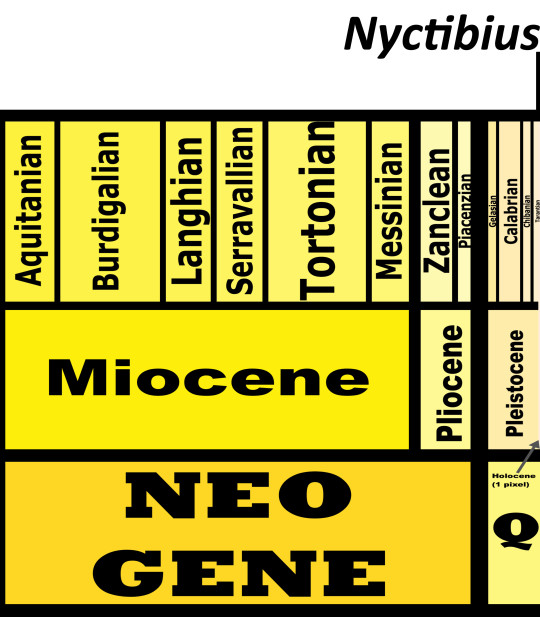

Time and Place: From 12,000 years ago through today, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

Potoos are known from Central and South America, around the Equator

Physical Description: Potoos are some of the weirdest birds alive today, looking about as ridiculous and muppet-like as any bird can really look. I’m honestly not sure if there is another living dinosaur that looks more like a muppet - and, of course, we don’t know if any extinct dinosaurs could have taken home the gold. The only probable and possible contender is the Frogmouth, which may just be the slightest amount more muppet-like, but it’s a close contest. They have distinctive faces, that are more feather than underlying tissue - their beaks stick out a bit, with a small hooked beak at the end. They have a large mouth, covered in fluff. Their eyes have a general sunken in appearance, which makes them look very large compared to the rest of the face. Their heads are very large compared to the rest of their bodies, and they have long bodies with short wings and long, fluffy tails. So, when they stand up, they look… well, they look like a stump, or a log standing up. They can then make themselves skinnier, which makes their eyes stand out compared to the rest of their bodies… which gives them the general appearance of a completely ridiculous animal. They can range in size from 21 to 58 centimeters, and range in color from reddish brown, to more orange brown, to more grey in color. This genus is not sexually dimorphic, though some species have variants in color.

By Charles J. Sharp, CC BY-SA 4.0

Diet: Potoos eat a lot of insects - from beetles to moths, to mantids, ants, termites, cicadas, leafhoppers, and grasshoppers.

Rufous Potoo by Eric Gropp, CC BY 2.0

Behavior: Potoos will hunt by standing extremely still on their perches - often, again, making themselves to look like a continuous log - and waiting for food to appear. Since they’re nocturnal, they are easily missed by the insects, as they blend into the background around them. Then, when they spot the prey, they launch forward, jutting forward to catch the insects and swallow them. Some species are more clumsy in this endeavor than others, though some are able to make leaps over several meters in order to grab the food they desire. They then return to the same post, returning to their previous log-like stillness as they wait for more food to appear. They’ll look around for the food by turning their heads rapidly from side to side - weirdly like owls, though they are not closely related to them at all. These perches can be only one meter off the ground, or up to 19 meters, depending on the forest around the potoo in question.

Common Potoo by the American Bird Conservancy

Potoos aren’t the most musical or birds, but they are loud - they make harsh, guttural “bwa-bwa-bwa” calls, similar to laughing or wailing. They can also make drawn out, descending rasps, that are… somewhat more musical at least. They tend to make their sounds mostly at dusk, right before dawn, and also on moonlit nights - so when it is Dark, but not too dark. These sounds, of course, do vary from species to species. There are some courtship calls, including descended calls made by females during the mating ritual, but they aren’t a major feature of these events. So, instead of picturing the great wolves as your moonlight singers, remember: the Potoos can and WILL be making these weird urts, laughs, and whistles, every time the moon is full and out in the sky. Potoos do not migrate, but they do appear to move sporadically in response to season changes and mating territory disturbances.

Long-Tailed Potoo by Lee R. Berger, CC BY-SA 3.0

As for nesting, Potoos are not… fantastic at the prospect, because of their tiny legs and weird, weird beaks. This makes them not great at both sitting on the nest and feeding the chicks. Still, they do it anyway, and clearly well enough since they aren’t endangered with extinction. They are monogamous, with both parents working together to incubate the egg and raise the chick, and they don’t build a nest - instead, the egg is laid in a depression on the branch, usually on top of a rotting stump. The male incubates the egg during the day, while the female will do so with the male at night. The chick is hidden almost entirely through camouflage. They hatch about a month later, and then stay in the nest for two more months, being protected by the parents and fed by them as well. They look… like clumps of fungus. Hiding underneath the log of their parents. The parents will defend themselves and the nest with mobbing behavior, crowding a predator and dive bombing it, and also calling at it loudly. In short, these birds are a Giant, Giant mess of Chaos.

White-Winged Potoo by Mark Sutton

Ecosystem: Potoos are known primarily from rainforests, and can be found at any level of the forest - some Potoos are known from the understorey, some from the middle, and some from the canopy - it really depends. They’re also found in very swampy forests, depending on the species and the habitats in question. They tend to stick to where there are easily accessible sources of water, regardless, especially rivers and lakes in the jungle. They stick to the deep interior of the forest, not venturing to forest edges much unless driven to by necessity. Some species are also found in mountain forest habitats. They have few natural predators after reaching adult size, though the young are hunted upon by monkeys and falcons.

Andean Potoo by Isirvio, CC BY-SA 2.0

Other: Potoos are a part of the Stirsorians, a group of WEIRD BIRDS that are adapted for a variety of extremely unique ecological niches, usually depending on their flight style. Close relatives of the Potoo include the Frogmouth, Nightjars, Oilbirds, Swifts, and Hummingbirds, among others. Potoos are highly adapted for their nocturnal lifestyle, adapted to blend in with their forested surroundings above all else. None are threatened with extinction at this time, though of course some species are rarer than others, and all are vulnerable to climate change and extensive habitat destruction in the American Rainforests. They are also quite uncommon birds, which of course affects their vulnerability as well.

Northern Potoo by Dominic Sherony, CC BY-SA 2.0

Species Differences: The different species of Potoo vary mainly on size, coloration, habitat, and location. The Rufous Potoo is one of the most notable, being very red in color and also the smallest species; it is known from northern Amazonia, in the middle and lower storeys of the forest. Great Potoos are the heaviest species, and greyish to yellowish brown; they are found in the canopy of Amazonia. The Long-Tailed Potoo is the longest species, and is a darker brown; it is found in lowland forest in Amazonia. The White-Winged Potoo has - you guessed it - white wings, and is small in size; it is found in the canopy of lowland Amazonia rainforest. The Andean Potoo is very dark and Extremely Muppety, and is found in mountain forests in the Andes Mountains. The Common Potoo is the most middle brown of them all and very middle in size, so the Averagest Potoo of them All; it is found in wet open woodland, usually at forest edges and the canopy, throughout Northern South America. The Northern Potoo is similar to the Common Potoo but usually larger, and it is also found in forest edges, but in Central America and the Carribean.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, D. Roberson, T. A. Fredericks, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood. 2017. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: v2017.

Cohn-Haft, M. (2019). Andean Potoo (Nyctibius maculosus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Cohn-Haft, M. (2019). Common Potoo (Nyctibius griseus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Cohn-Haft, M. & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Great Potoo (Nyctibius grandis). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Cohn-Haft, M. & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Long-tailed Potoo (Nyctibius aethereus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Cohn-Haft, M. & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Northern Potoo (Nyctibius jamaicensis). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Cohn-Haft, M. & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Rufous Potoo (Nyctibius bracteatus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Cohn-Haft, M. (2019). White-winged Potoo (Nyctibius leucopterus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

#Nyctibius#Potoo#Strisorian#Dinosaur#Bird#Birds#Birblr#Dinosaurs#Factfile#North America#South America#Quaternary#Insectivore#Flying Friday#Nyctibius bracteatus#Nyctibius grandis#Nyctibius aethereus#Nyctibius leucopterus#Nyctibius maculosus#Nyctibius griseus#Nyctibius jamaicensis#Rufous Potoo#Great Potoo#Long-Tailed Potoo#White-Winged Potoo#Andean Potoo#Common Potoo#Northern Potoo#biology#a dinosaur a day

273 notes

·

View notes

Text

Larosterna inca

By Cristóbal Alvarado Minic, CC BY 2.0

Etymology: Gull-Tern

First Described By: Blyth, 1852

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Aequorlitornithes, Charadriiformes, Lari, Larida, Laridae, Sterninae

Status: Extant, Near Threatened

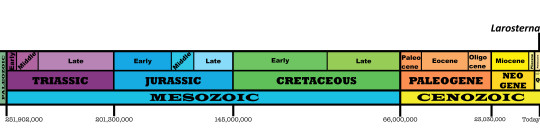

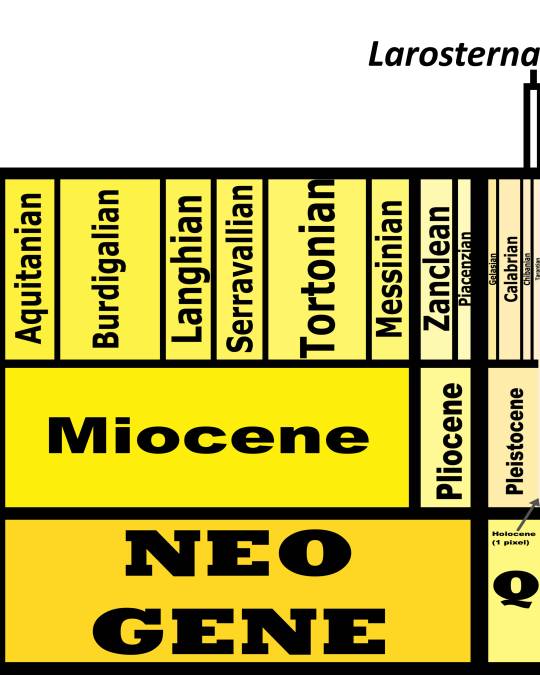

Time and Place: Since 126,000 years ago, from the Chibanian of the Pleistocene through the Holocene of the Quaternary

Inca Terns are known from the Pacific Coast of South America

Physical Description: Inca Terns are extremely visually distinctive birds, thanks to their bright red beaks and weird villainous-moustache feather plumes. These birds range in size between 39 and 42 centimeters in length, and are grey over most of their bodies. Their tails are distinctively black, and the wings are grey before ending in a distinctive white band and then continuing to black tips when folded. Their beaks are bright red, large, and slightly curved. They have a small yellow patch of feathers under their eyes, and a very long, curly white feather ribbon going from right under their eye down their neck. Their legs are short and dark red as well. The juveniles tend to be more brown all over before becoming darker with age.

Diet: Inca Terns feed primarily on small fish, plankton, and scraps.

By Cristóbal Alvarado Minic, CC BY 2.0

Behavior: These terns will stick to fishing boats in large flocks, hovering around them in order to opportunistically feed off of food brought up by fishing activity. They often will detect large sea mammals and fly away - rapidly - to avoid them, and also to grab the food that is welled up by them. They can often live in flocks of up to 5000 members. They forage by plunging in the water and diving for food, as well as dipping a little on the surface. They do not migrate, and are extremely loud at their colonies - making a variety of cackling and mewing sounds.

By Cristóbal Alvarado Minic, CC BY 2.0