#Southern Variable Pitohui

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

A new variant has been added!

Southern Variable Pitohui (Pitohui uropygialis) © David Bishop

It hatches from black, brown, large, orange, secondary, similar, southern, and variable eggs.

squawkoverflow - the ultimate bird collecting game 🥚 hatch ❤️ collect 🤝 connect

0 notes

Text

Pitohui

Hooded Pitohui by Berichard, CC BY-SA 2.0

Etymology: Inedible (Rubbish) Bird

First Described By: Lesson, 1831

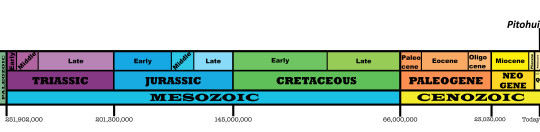

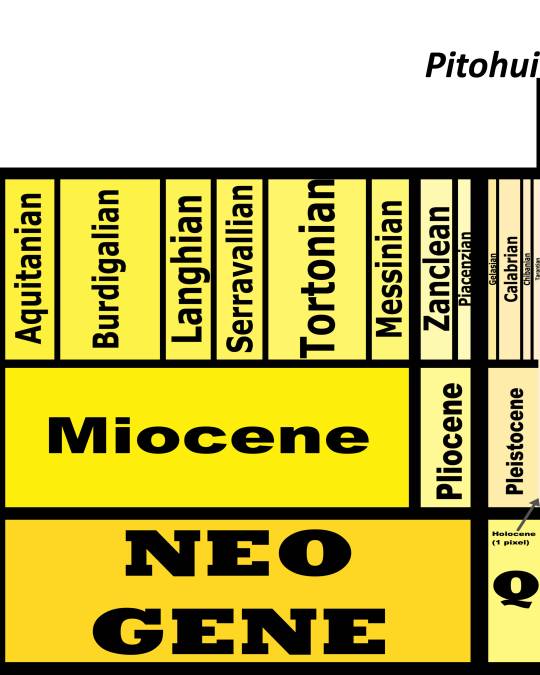

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Australaves, Eufalconimorphae, Psittacopasserae, Passeriformes, Eupasseres, Passeri, Euoscines, Corvides, Orioloidea, Oriolidae

Referred Species: P. kirhocephalus (Northern Variable Pitohui), P. cerviniventris (Raja Ampat Pitohui), P. uropygialis (Southern Variable Pitohui), P. dichrous (Hooded Pitohui)

Status: Extant, Least Concern

Time and Place: Since 10,000 years ago, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

Pitohuis are endemic to New Guinea

Physical Description: The Pitohuis look like your average Corvids - large passerines with dark coloration, thick bills, and high intelligence - but there’s more to these strange birds than meets the eye. Pitohuis are some of the rare examples of poisonous birds! Pitohuis tend to range in size between 20 and 26 centimeters long, and they are mostly black all over with brown to bright orange patches on their bellies or backs - though there is, of course, one species that is primarily brown. They have large, thick black bills, short wings, and short tails. The sexes tend to be very alike in these birds, though some species have subpopulations with different colorations. The juveniles, in general, are more brown in regions that are black in the adults. These birds are extremely toxic, with a neurotoxin called homobatrachotoxin in their skin, feathers, and other tissues. The least toxic parts of these birds are their bones. The toxins are secreted into their feathers on purpose; though some is left behind in muscle and organ tissue, which indicates a lack of sensitivity to the toxins by the birds. Some individuals do not have the toxins, probably due to a lack of the toxin-making beetles in their diets; but this is a variable occurrence and the vast majority of Pitohuis have the toxins in their feathers and skin.

Southern Variable Pitohui by Markus Lilje

Diet: Pitohuis primarily feed on insects, though at least a few species also supplement their diets with fruit and seeds. Most importantly, they feed on beetles of the genus Choresine, which contain the toxin they incorporate into their feathers.

Raja Ampat Pitohui, by Carlos N. G. Bocos

Behavior: Pitohuis tend to forage at most levels of the forest, oftentimes in mixed-species flocks, though they are the ones that feed more on poisonous beetles than others in these flocks. They will hide in dense vegetation in order to avoid letting their prey know they’re there, but since they don’t have a lot of predators they don’t have to worry much about them. They do not migrate, but they are extremely vocal and social - making a variety of whistling and calls, which vary in word from species to species. Some are more leisurely than others, and they go between a variety of high and low pitches. Usually, they are quite musical and loud. Pitohuis begin breeding in early spring, and start nesting in the summer - though Hooded Pitohuis tend to lay more in the autumn. Multiple mated pairs probably work together to take care of the nest, which is a cup of vines and tendrils suspended on slender branches a few meters up from the ground. They typically lay one to two eggs a season.

Hooded Pitohui by Markus Lilje

Ecosystem: Pitohuis live mainly in tropical rainforest and mangrove forests, as well as mountainous forests. They live at a variety of elevations, up to 2000 meters high; many species can also be found at forest edges and swamp forests, as well as lowlands. They do overlap with many other Pitohuis - including each other - and share the poisonous beetles among one another. Potential predators, including a variety of snakes, show marked sensitivity and irritation to even small amounts of the toxins found in the feathers of these birds - and as such, predators of the Pitohuis are not known at this time, at least of the adults. The young, who might not have as much of these toxins in their feathers and skin, are still vulnerable to nest raiders. Humans also do not feed on Pitohuis - leading to their name!

Northern Variable Pitohui by Paul van Giersbergen

Other: Toxicity in birds is an extremely rare trait, but it seems to have evolved multiple times in birds in New Guinea. In fact, Pitohui is a general name often used for any such poisonous bird, but recent scientific studies has showcased they’re not actually closely related at all! So, many species of Pitohui actually belong to other genera in not closely related groups of songbirds. While the ones we discussed today are Orioles, some are Bellbirds and others are Whistlers/Shrikethrushes. They are all, however, in the general Corvides group. The reasons as to why toxicity evolves in birds is debated - it may be a defensive measure (and is used as such), but it also might just be a consequence of their diet. They had to do something with the toxins from the beetles - so why not shed it out into their feathers? And then, BONUS! They aren’t eaten by a lot of predators! Regardless of how this odd trait began, they aren’t hunted or eaten very much as a result! Though having a limited range, the toxicity of these birds means that they are rarely fed upon by predators - including humans - and as such, they are common in their ranges.

Hooded Pitohui by Frédéric Pelsy

Species Differences: The Pitohuis mainly differ based on their coloration from species to species, though there are some range differences (the Hooded and Northern Pitohuis live on the northern half of New Guinea, the Southern Pitohui on the Southern Half, and the Raja Ampat Pitohui only on the island of Waigeo. Hooded Pitohuis have black heads and wings, with black tails; the rest of their bodies are utterly black orange. Raja Ampat Pitohuis are brown almost everywhere, except for having a lighter orange on their bellies and black tips to their wings and tails. Northern Variable Pitohuis can be one of three color schemes: grey heads with brown backs black tails and wings and bright orange bellies; black heads with dark orange backs black wings black tails and lighter orange bellies; or dark orange on top all over and a lighter orange on the belly. Southern Variable Pitohuis can be black on their heads wings and tails with a dark red-orange on their backs and bellies; or black on their heads and tails and wings with dark orange on top and lighter orange on bottom in only the males, while the females have more brown heads. So much variation!

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Beadell, J.; Gering, E.; Austin, J.; Dumbacher, J.; Peirce, M.; Pratt, T.; Atkinson, C.; Fleischer, R. (2004). "Prevalence and differential host-specificity of two avian blood parasite genera in the Australo-Papuan region". Molecular Ecology. 13 (12): 3829–3844.

Boles, W. (2019). Hooded Pitohui (Pitohui dichrous). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Boles, W. & Kirwan, G.M. (2019). Northern Variable Pitohui (Pitohui kirhocephalus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

del Hoyo, J., Collar, N., Kirwan, G.M. & Boesman, P. (2019). Southern Variable Pitohui (Pitohui uropygialis). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

del Hoyo, J., Collar, N., Kirwan, G.M. & Boesman, P. (2019). Waigeo Pitohui (Pitohui cerviniventris). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Diamond, J. (1987). "Flocks of brown and black New Guinean bird: a bicolored mixed-species foraging association". Emu. 87 (4): 201–211.

Dumbacher, J.; Beehler, B.; Spande, T.; Garraffo, H.; Daly, J. (1992). "Homobatrachotoxin in the genus Pitohui: chemical defense in birds?". Science. 258 (5083): 799–801.

Dumbacher, John P. (1999). "Evolution of toxicity in Pitohuis: I. Effects of homobatrachotoxin on chewing lice (Order Phthiraptera)". The Auk. 116 (4): 957–963.

Dumbacher, J. P.; Spande, T. F.; Daly, J. W. (2000). "Batrachotoxin alkaloids from passerine birds: A second toxic bird genus (Ifrita kowaldi) from New Guinea". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 97 (24): 12970–12975.

Dumbacher, J. P.; Fleischer, R. C. (2001). "Phylogenetic evidence for colour pattern convergence in toxic pitohuis: Mullerian mimicry in birds?". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 268 (1480): 1971–1976.

Dumbacher, J. P.; Wako, A.; Derrickson, S. R.; Samuelson, A.; Spande, T. F.; Daly, J. W. (2004). "Melyrid beetles (Choresine): A putative source for the batrachotoxin alkaloids found in poison-dart frogs and toxic passerine birds". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (45): 15857–15860.

Dumbacher, J; Deiner, K; Thompson, L; Fleischer, R (2008). "Phylogeny of the avian genus Pitohui and the evolution of toxicity in birds". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 49 (3): 774–781.

Dumbacher, John P.; Menon, Gopinathan K.; Daly, John W. (2009). "Skin as a toxin storage organ in the endemic New Guinean genus Pitohui". The Auk. 126 (3): 520–530.

Glendinning, J. (1993). "Pitohui: how toxic and to whom?". Science. 259 (5095): 582–583.

Jønsson, K. A; Bowie, R. C.K; Norman, J. A; Christidis, L.; Fjeldsa, J. (2008). "Polyphyletic origin of toxic Pitohui birds suggests widespread occurrence of toxicity in corvoid birds". Biology Letters. 4 (1): 71–74.

Jønsson, Knud A.; Bowie, Rauri C. K.; Moyle, Robert G.; Irestedt, Martin; Christidis, Les; Norman, Janette A.; Fjeldså, Jon (2010). "Phylogeny and biogeography of Oriolidae (Aves: Passeriformes)". Ecography. 33 (2): 232–241.

Lamothe, L. (1979). "Diet of some birds in Araucaria and Pinus forests in Papua New Guinea". Emu. 79 (1): 36–37.

Legge, S.; Heinsohn, R. (1996). "Cooperative breeding in Hooded Pitohuis (Pitohui dichrous)". Emu. 96 (2): 139–140.

Ligabue-Braun, Rodrigo; Carlini, Célia Regina (2015). "Poisonous birds: A timely review". Toxicon. 99: 102–108.

Menon, Gopinathan K.; Dumbacher, John P. (2014). "A "toxin mantle" as defensive barrier in a tropical bird: evolutionary exploitation of the basic permeability barrier forming organelles". Experimental Dermatology. 23 (4): 288–290.

Mouritsen, Kim N.; Madsen, Jørn (1994). "Toxic birds: defence against parasites?". Oikos. 69 (2): 357.

Poulsen, B. O. (1994). "Poison in birds: against predators or ectoparasites?". Emu. 94 (2): 128–129.

Sam, Katerina; Koane, Bonny; Jeppy, Samuel; Sykorova, Jana; Novotny, Vojtech (2017). "Diet of land birds along an elevational gradient in Papua New Guinea". Scientific Reports. 7 (44018): 44018.

#Pitohui#bird#Dinosaur#Songbird#Poisonous Bird#Passeriform#Perching Bird#Songbird Saturday & Sunday#Quaternary#Australia & Oceania#Insectivore#Northern Variable Pitohui#Raja Ampat Pitohui#Southern Variable Pitohui#Hooded Pitohui#Pitohui kirhocephalus#Pitohui cerviniventris#Pitohui uropygialis#Pitohuis dichrous#Birds#Dinosaurs#Factfile#Birblr#Waigeo Pitohui#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science

162 notes

·

View notes