#Atchison County

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

American Auto Trail-Lands of David Rankin (Fairfax to Rock Port MO)

American Auto Trail-Lands of David Rankin (Fairfax to Rock Port MO) https://youtu.be/PhjRCz3jHEI This American auto trail crosses the Tarkio Valley and continues northwest through the farmland David Rankin made famous.

View On WordPress

#4K#american history#Atchison County#Auto trail#David Rankin#driving video#Fairfax#missouri#missouri river#road travel#Rock Port#slow travel

0 notes

Text

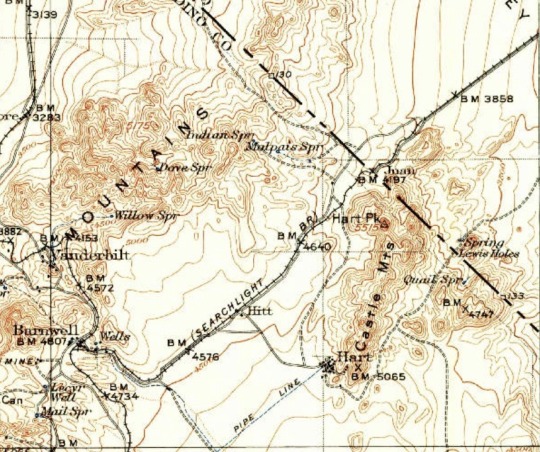

Barnwell and Searchlight Railroad

The Barnwell and Searchlight Railroad was a twenty three miles long railroad which connected Searchlight, Nevada to Barnwell California and the larger rail network of the Mojave Desert. Following the discovery of gold in Searchlight in 1897 a gold rush brought industry into the high desert of the Mojave. In 1900, the Quartette Mining Company formed and within a short years a population of 5000…

View On WordPress

#Atchison#Barnwell#Barnwell and Searchlight Railroad#California#California Arizona and Santa Fe Railway#Clark County#Hart#Juan#Nevada#Railroad#San Bernardino#Searchlight#Topeka and Santa Fe Railway

0 notes

Text

Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe railroad train no. 97 led by diesel switcher locomotive 2229 between Spruce (Douglas County) and Palmer Lake (El Paso County), Colorado. July 25, 1955

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Redid Penelope by simplifying her look (again) and also reworked on the roadway of Mapleville Ridge, thanks to advice. I skimped out on the shading on Penelope since I thought it looked tacky on her. However, that could change at any time, and I could add it in to her and to make her look consistent with everybody else.

Yes, Mapleville Ridge, Wisconsin doesn't really exist, so I had to make it myself. Mapleville Ridge, Wisconsin is a large, major metropolitan city that is located in Milwaukee County, Wisconsin. Mapleville Ridge is the main setting where the events of My Life as a Teenage Rabbot generally takes place in, and is home to the Wilberson family, a family of anthropomorphic animals, humans, robots, and so on.

If you'd like to know more about Mapleville Ridge or Penelope Atchison, you're more than welcome to check out the My Life as a Teenage Rabbot Wiki, a.k.a. the “Rabbotpedia”.

#my oc#oc art#oc artist#my art stuff#original character#oc drawing#the loud house#ocs#digital illustration#cityscape#buildings#town#fan series#fanart

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Larry W. Schwarm

Egg Sign, Atchison County, from the Kansas Documentary Survey Project, 1974

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Members of Troop G of the U. S. Army march near a passenger train at the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad depot in Dodge City (Ford County), Kansas. 1917

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

There's a suburb of Kansas City called Peculiar

According to Wikipedia

There are at least two versions of the story on how Peculiar received its name. The first involves the community's first postmaster, Edgar Thomson. His first choice for a town name, "Excelsior," was rejected because it already existed in Atchison County, Missouri. Several other choices were also rejected. The story goes that the annoyed Thomson wrote to the Postmaster General himself to complain saying, among other things, "We don't care what name you give us so long as it is sort of 'peculiar'." Thomson submitted the name "Peculiar" and the name was approved. The post office was established on June 22, 1868.[6]

In an alternate version, according to Missouri folklorist Margot Ford McMillen, early settlers were searching for a location to farm. As they cleared a small rise and looked below, one remarked "Well that's peculiar! It's the very place I saw in a vision back in Connecticut." The land was purchased and eventually a village sprang up on it, which was named "Peculiar"

Most oddly named town in each US state.

74K notes

·

View notes

Text

Miss Oregon USA 2024 predictions: Shayla Montgomery, Ana Gonzalez, Taisyn Crutchfield

Oregon, United States currently has 11 Miss USA placements including the second runner-up finish of Gail Atchison in 1976. The most recent one was in 2018 when Toneata Morgan finished in the Top 15. On October 15, 2022, Manju Bangalore of Benton County won Miss Oregon USA 2023 at the Sherwood Center for the Arts in Sherwood, Oregon. The respective first, second, third and fourth runners-up were…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

quindaro - Google Search

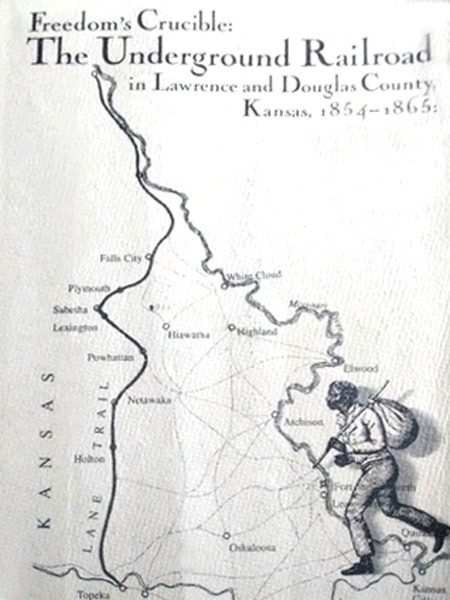

Quindaro, Kansas – A Free-State Black Town

Western University in Quindaro, Kansas.

Quindaro, Kansas, an old historic town of Wyandotte County, was situated on the south bank of the Missouri River. Though the town is extinct today, it has a rich history, and there is still a Quindaro neighborhood in Kansas City, Kansas today.

Missouri River near Kansas City, Kansas by Laura Ziegler/KCUR

A settlement was established on the Quindaro Bend of the river in about 1850 because it was located across from Missouri, a slave state. At that time, it was a stop along the Underground Railroad. After the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed in 1854, a western branch of the Underground Railroad was developed in Kansas that linked Quindaro to the Lane Trail and provided a new route of escape for slaves from Missouri.

Early residents, who were known as “Seekers of Freedom” because of their escaped slave status, included the families of Turner, Banks, Marshall, Grigsby, Harris, Endicott, Barnett, Duncan, Creek, Graves, Murray, and Sanders.

The old Quindaro Cemetery, established in 1853, is the oldest in the state.

Abolitionists developed the town after the Kansas-Nebraska Act passed in 1854 to create a free state port of entry into Kansas Territory. As the only free-state river port in Kansas, six steamboats a day were soon landing there.

Nancy Quindaro Brown Guthrie

At that time, the land was part of an area that the Wyandot Indians had purchased from the Delaware tribe. When the Wyandot tribe disbanded, the land was divided among tribal members who wished to remain in the area and become U.S. citizens. Among these people were Abelard Guthrie and his wife, Nancy Quindaro Brown Guthrie, for whom the town was named. Mrs. Guthrie was a Wyandot lady of royal blood whose father was chief of the Canadian Wyandot.

The townsite at that time was located six miles above Kansas City, Kansas (then called Wyandotte.)

In 1856, the pro-slavery river port towns of Atchison, Leavenworth, and Delaware City were practically closed to Free State settlers, and several fugitives from these settlements were assisted down the river to safety by Mr. Guthrie, who owned much of the land in the vicinity. It was during these years, before Kansas was established as a free state, that the underground railroad was so important. By this time, pro-slavery factions were establishing blockades on the Missouri River to prevent Free State supporters from accessing supplies and reinforcements as well as blocking their travel.

Tensions between pro and anti-slavery groups caused several instances of armed violence and death in the Missouri-Kansas Territory border region that increased the urgency of the abolitionist cause and the need to establish a Free State river port. In September of 1856, Charles Robinson and Samuel Simpson, two men formerly associated with the New England Emigrant Aid Company, approached Abelard Guthrie about the prospect of starting a Free State town on the Missouri River.

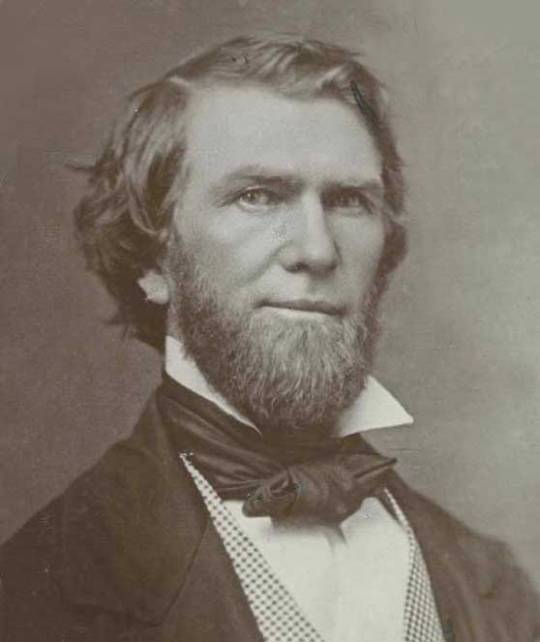

Abelard Guthrie

In the fall of 1856, the Quindaro Town Company was formed by an alliance of Wyandot Indians and Free-State supporters. The site on Quindaro Bend was at a point six miles above the mouth of the Kansas River, where a fine natural rock ledge stood, and the river ran along the bank six to twelve feet deep, making a convenient landing. Plenty of wood and rock were at hand for building purposes, and fertile land was adjacent.

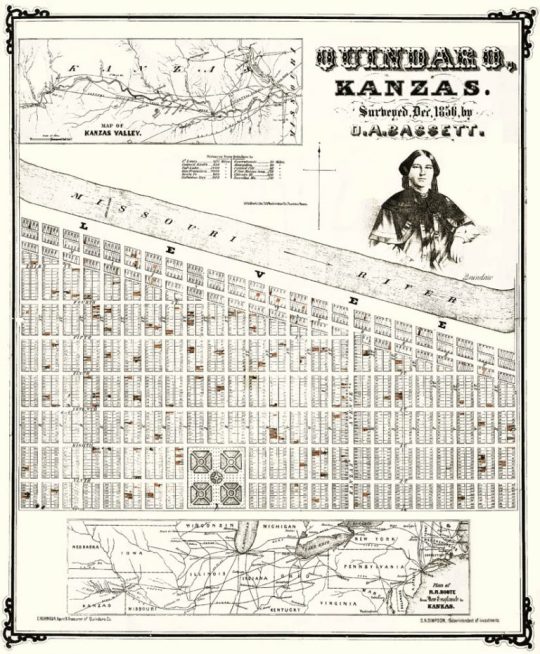

In December 1856, the town was surveyed by P.H. Woodward and platted by Owen A. Bassett. The northern boundary of the town coincided with the Missouri River, upon which a wharf facilitated steamboat landings.

Two commercial thoroughfares, named Levee and Main Streets, ran perpendicular to the river and the town’s primary commercial thoroughfare, named Kanzas Avenue, which now aligns with the present-day 27th Street. The Quindaro Townsite plat included Quindaro Park, one of the first public parks in Kansas.

Quindaro, Kansas Plat Map 1856

The sale of lots and the construction of buildings in Quindaro began in January 1857. By the end of the month, an 8×10 foot temporary office for the Quindaro Town Company, the townsite’s first building, was completed. The first business in Quindaro, the W.J. McCown Store, opened in March on Main Street near the town’s steamboat landing. The establishment of the Quindaro Steam Saw Mill Company in April on Levee Street dramatically increased the pace of building in the new town. Owned by Otis Webb and A.J. Rowell, the mill was the largest of its kind in Kansas Territory.

By April 1, three or four buildings were completed, including the five-story Quindaro House, the second-largest hotel in the territory. The hotel, operated by Philip T. Colby and Charles S. Parker, located at 1-3-5 Kanzas Avenue, also featured the Johnson and Veale Merchants store on the first floor as well as the Quindaro Post Office, established that May.

“There is a farm here for everyone who will come and take possession, a soil whose richness is unsurpassed in the country, a climate unequaled, and a population who are brave, generous, and hospitable. So come on where there is room enough and to spare.” — Hillsdale, Michigan Standard, March 17, 1857

Word-of-mouth that the Quindaro steamboat landing was the best point of entry into Kansas for Free State settlers only served to attract more people to the town. The Quindaro wharf on the Missouri River was completed by May of 1857, reportedly facilitating 36 steamboat landings in one week.

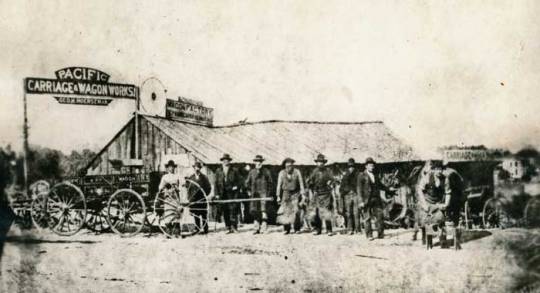

Carriage-Wagon Shop in Quindaro, Kansas.

That same month, a large group of men began to grade the ground near the levee and Kanzas Avenue, which was the main street running south from the river. This commercial corridor was developed in a manner that provided easy access to the town’s wharf and riverfront, facilitating the import and export of goods. Rows of warehouses, predominantly used for storage, lined Levee Street near the wharf, while commercial businesses were located along Main Street, concentrated at the intersection of Main Street and Kanzas Avenue and continuing south along Kanzas Avenue for a block and a half to Sixth Street.

Construction of a road from Quindaro to Lawrence began almost immediately. By May, Alfred Robinson had built a livery stable and established a stagecoach line that charged $3.00 for the six-hour coach trip to Lawrence. Another road traveled south from Kanzas Avenue to the town of Wyandotte (this road eventually became present-day Quindaro Boulevard.) A third road led south to the Shawnee Reserve and linked Quindaro with the Santa Fe and Oregon Trails.

Jacob Zehntner and Henry Steiner built this brewery at 45 N Street, on the west side of Quindaro Creek, in 1857 by Kathy Alexander.

Ebenezer O. Zane’s Wyandotte House Hotel was located across Kanzas Avenue from the Quindaro House Hotel. The J.P. Upson Building was located at 7 Kanzas Avenue, south of the Quindaro House Hotel, and contained the office of the town’s weekly newspaper.

Jacob Zehntner and Henry Steiner built a brewery at 45 N Street, on the west side of Quindaro Creek, in 1857. The main brewery building was a two-story brick and stone structure with a taproom, vaulted beer cellar, and living quarters. Today, its ruins are the only visible remains above ground of the Old Quindaro townsite.

On May 3, a schoolhouse was opened, which also served as a church on Sunday.

The first newspaper, the Chin-do-wan (a Wyandot word meaning leader), owned by Edmund Babb and John M. Walden, appeared on May 13, 1857, and at once began to advertise the new town. John Walden was also a missionary to the freedmen, was involved in the Underground Railroad, and later became a bishop in the Methodist Church. The associate editor of the abolitionist newspaper was Clarina Nichols, who was involved in the temperance, abolition, and suffrage movements in the 19th century. A friend of Susan B. Anthony and a fellow crusader for the rights of women and children, she was also an important Conductor and Station Master of the Underground Railroad. Nichols reported that many slaves took the underground railroad at Quindaro, and she left a letter telling about a time when a Freedom Seeker named Caroline was brought to her home. She hid her in an empty cistern overnight and then sent her on the road North as soon as it was safe.

Clarina Irene Howard Nichols

“My cistern – every brick of it rebuilt in the chimney of my late Wyandotte home – played its part in the drama of freedom. One beautiful evening late in October ’61, as twilight was fading from the bluff, a hurried message came to me from our neighbor – Fielding Johnson – ‘You must hide Caroline. Fourteen slave hunters are camped on the Park – her master among them.’ … Into this cistern Caroline was lowered with comforters, pillow, and chair. A washtub over the trap with the usual appliances of a washroom standing around, completing the hiding.”

— Clarina Nichols

The first issue of the newspaper reported that trees had been removed from several acres of the townsite and that 30-40 houses had been built and occupied, and that 16 business houses were in the process of erection. By August, the first brick house was under construction on “P” street, the bricks having been burned on the townsite, and soon a brickyard was established.

One of the earliest problems of the new town was to gain recognition by the steamboats. These crafts were Missouri-owned and operated, and their officers refused to stop at Quindaro or even denied that such a place existed. Later, they actively sought to get passengers to pass up Quindaro to land at Leavenworth or Wyandot, both of which were pro-slavery towns.

Steamboat on the Missouri River

A threat to start a Free-State steamboat line from Alton, Illinois, to Kansas, broke up this racket as the pro-slavery boatmen didn’t want such competition.

The Quindaro post office opened on May 14, 1857. Professional men came in, and real estate agents did a good business. F. Johnson and George Veale opened a general merchandise store and were followed by other firms in the same line. Simpson, Macaulay & Smith, forwarding and commission merchants, also opened a store. Charles B. Ellis, a civil engineer and surveyor, opened an office, and Quindaro was soon believed to become one of the largest towns on the river.

Thaddeus Hyatt brought the 100-foot Lightfoot Ferry to Quindaro and completed a few trips to Lawrence via the Kansas River before transitioning service to the Missouri River, which was more navigable. The 100-foot Otis Webb Ferry was also put into operation, offering daily trips between Quindaro and Parkville, Missouri, located two miles up the Missouri River, and occasional trips to the towns of Wyandotte (Kansas City) or Leavenworth.

Temperance Movement

Quindaro was a temperance town, the lots having been deeded with the stipulation that liquor dealers should not occupy them. However, some groggeries crept in, and by June 1857, the women petitioned, and the men acted to clean them out. This induced many emigrants, especially women, to prefer Quindaro to other towns.

Dr. George E. Budington advertised as a physician; Ireland & McCorkle were carpenters and joiners; Fred Klaus, a stone cutter and mason, had a quarry a short distance from town; A. C. Strock & Co. operated a drug store, and Dr. J. B. Welborn had an office in the same building; William Shepherd and D. D. Henry established a hardware store. Mr. Robinson, Gray, Johnson, Webb, and others were rushing around for subscriptions to build the Quindaro, Parkville & Burlington Railroad to obtain a connection with the Hannibal & St. Joe Railroad. By fall, the Methodist Church was built.

Quindaro’s residents also worked to create social institutions and hold cultural events, including a Quindaro Literary Association and a Quindaro Library Association, outfitted with over 200 books. The Literary Association published a journal edited by Clarina Nichols called The Cradle of Progress and held meetings and public lectures in a residence at 62 P Street, a house that would later be called “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and was associated with Underground Railroad activity.

Underground Railroad in Kansas

Through the end of 1857, Quindaro had rapidly developed into a booming pioneer river port town, with stores, hotels, churches, and residences constructed across the steep landscape to support its growing population. The lower townsite near the river was the commercial core, and most residences were higher on the bluff at the upper townsite.

In these early years, Quindaro became an important station on the Underground Railroad, with slaves escaping from Platte County, crossing the river in small boats, and making secret runs of the Parkville-Quindaro Ferry. The runaways hid with local farmers before traveling to Nebraska for freedom.

Quindaro, a Wyandot word translated to “In union there is strength,” fit the town well as there was no end of public confidence in the future of the town that was expected to rival Kansas City, Leavenworth, Atchison, and Wyandotte (Kansas City.)

At the time that the city charter was first approved in January 1858, Quindaro had a population of 800 and boasted 100 buildings, many of which were built of stone and brick that were of a substantial, metropolitan appearance. Businesses included two hotels, a hardware store, three dry goods stores, four groceries, a clothing store, two drug stores, two meat markets, two blacksmiths, a wagon shop, six boot and shoe shops, and a livery stable. There were also four doctors, three lawyers, two surveyors, and several carpenters and builders, as well as two churches and a schoolhouse.

Chin-do-wan Newspaper, 1857

The Chin-do-wan kept up its trumpeting and was bought by V. J. Lane, G. W. Veale, and Alfred Gray, who also published the Kansas Tribune in the fall and winter of 1858-59. The publication was continued for the benefit of the town company until 1861 when it was removed to Olathe.

Quindaro was thought to have reached a peak population of as many as 1,200 people. But Kansas City, Atchison, and Leavenworth were rapidly becoming centers of population and trade, and as they were the natural gateways of the territory, Quindaro began to decline.

The 1860 federal census recorded a population of 689, with a majority (92%) of residents being white, 4% black or “mulatto”, and 4% American Indian. The Census does not indicate whether the black residents were escaped slaves or freedmen. The most common occupation was “farmer,” followed by “laborer.” At the same time, the rest of the males of working age held positions that supported the town, such as hotel keepers, masons, engineers, carpenters, merchants, tinsmiths, bricklayers, and blacksmiths. A lease in 1860 established the right-of-way for the Missouri Pacific Railroad through Quindaro parallel to the Missouri River. The railroad company built the tunnel overpass that crosses 27th Street near the Missouri River.

In the next year, business houses moved to the more prosperous settlements, and the population gradually dwindled.

Underground Railroad by Charles T. Webber, 1893.

When Kansas was established as a free state in January 1861, there was less need for the port, and the growth slowed in the commercial district. At the same time, the economy in Kansas was also suffering from over-speculation. Then, with the opening of the Civil War in April, the town was abandoned by most of the inhabitants. The young men enlisted, and many of their families moved to other communities for safety.

The ferry from Parkville to Quindaro was reputed to be transporting runaway slaves across the river at night when pro-slavery forces sank it in 1861. In January 1862, a man named George Washington escaped from slavery near Parkville, Missouri by crossing the frozen Missouri River on foot. He made it to Quindaro by following pieces of cloth tied to trees by an Underground Railroad “conductor.” Washington then joined the 1st Regiment Kansas Colored Volunteers to fight for the Union in the Civil War.

Cavalry Training in the Civil War

For the dying town, matters were made worse when, from January 20 to March 12, 1862, the Ninth Kansas Volunteer Infantry under Colonel Alson C. Davis, was quartered in the empty business buildings of Quindaro as the troops underwent a reorganization to become the Second Kansas Cavalry. Unfortunately, officer control of the soldiers was slack, and the troops literally destroyed the commercial and residential buildings, tearing up everything movable for firewood and leaving shells where prominent buildings and houses once stood. Once the soldiers were gone, weather, fires, and theft finished them off in the next years.

The town’s charter was revoked by the Kansas State legislature in 1862, and the Quindaro Town Company was dissolved. However, several African Americans remained in the dead town, and Presbyterian minister Eben Blachly started classes in his home for the children of former slaves the same year.

Fugitive Slave

Though Quinidaro as a town was finished, its role as a major stop on the Underground Railroad had already been cast, and its story was far from over. During the Civil War, a number of African-American families escaped from slavery in the surrounding states and established their homes in “Old Quindaro.”

After the Union won the Civil War and the slaves were emancipated, many of them were drawn toward Quindaro because of its anti-slavery history. They settled on the mostly abandoned townsite occupying the empty buildings, particularly in the valley around Quindaro Creek. Newcomers to the area lived and farmed near the town in an area that came to be known as “Happy Hollow” to the west of Quindaro. Individuals and families farmed their own land or worked for the remaining white population. During this time, there was no center of commerce nor organized social, political, or economic structure, and most of the buildings were residential.

For a while, Quindaro served as an outfitting post for freight wagon trains. However, as railroad commerce surpassed river transportation, Quindaro’s steamboat landing languished, and the town’s economic prospects ceased.

By 1865, there were 429 African Americans living in the townsite, and a group of Quindaro citizens, with Reverend Blachly at the lead, opened the Quindaro Freedman’s School (later Western University), the first black school west of the Mississippi River and the only one ever to operate in the state of Kansas. The school was officially chartered in 1867 and was supported through donations, with only two teachers throughout its existence, Eben and Jane Blachly.

The private school operated under the Presbyterian Church and initially utilized available space in existing buildings. The school may have briefly operated from the Steiner and Zehntner Quindaro Brewery, although it occupied a former commercial building on Kanzas Avenue by 1870.

Later-arriving African-American residents settled in the upper town on the bluff. Difficulties in reaching the interior from below the bluff hampered commerce, and changes after the war reduced the need for the port.

By 1870, only a few original buildings and the Missouri Pacific Railroad station were still used. A map of the time showed a few businesses and residences in Quindaro, including Cyrus Taylor’s wagon manufacturing shop, W.J. Heaffaker’s dry goods and variety store, the D.R. Emmons & Company grocery store, a chair factory at the northwest corner of M and 8th streets, and the farms of Alfred Gray, E.D. Brown, and Thomas McIntyre. Also shown were the town’s white and black schools, the Methodist and Congregational churches, and Freedmen’s University housed within former commercial buildings at 34-40 Kanzas Avenue.

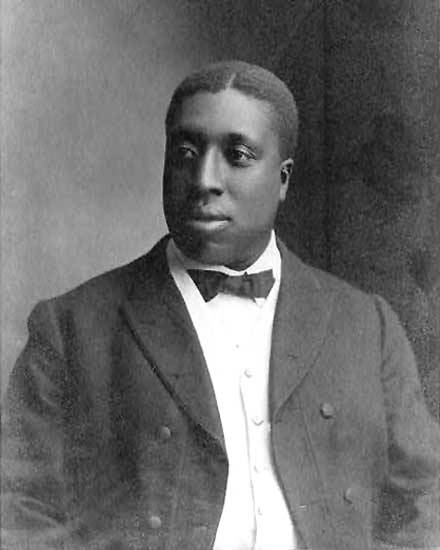

Charles Henry Langston

After being abandoned, the early lower commercial townsite became overgrown, with some areas covered by earth falling from the bluffs. A visitor in 1873 found the town’s former commercial district abandoned, writing, “One store with a granite front and iron posts stood as good as new and various other buildings were in good preservation, but empty.”

In the 1870s, property owners in the area donated land from the heart of the townsite to the school, and buildings were erected. In 1872, the Kansas State Legislature established the “Colored Normal School,” a teachers’ college, within Freedman’s University, as a way to create a self-sustaining educational institution and promote education throughout the area. At that time, Charles Henry Langston, a leading black abolitionist, activist, educator, and politician in Ohio and Kansas, became the principal.

The University struggled initially due to the inability of students to pay, which was common among contemporary African-American schools, and the lack of funding from the state, whose coffers were greatly depleted by widespread agricultural losses in 1873.

Exodusters En Route to Kansas, Harper’s Weekly 1879

Though the enrollment was beginning to surge, the college struggled to survive in the troubled mid-1870s, and in 1879, the school’s trustees took out a mortgage on part of the property in an attempt to keep the school open. Reverend Eben Blachly ran the school until his death in 1877, at which time the school became inactive for a short period.

When the last Federal troops left the southern states in 1877, Reconstruction gave way to renewed racial oppression and rumors of the re-institution of slavery. Fearful for their lives, many African Americans began to flee the south for Kansas in 1879 and 1880 because of the state’s fame as a Free-State and the land of the abolitionist John Brown. These people were called Exodusters. Many of them settled in Quindaro, generating renewed interest in Freedman’s University for a brief period of time, beginning in 1879. In 1881, the African Methodist Episcopal Church, under the direction of local community leader and elected official Corrvine Patterson, assumed control of the institution and converted it to a vocational/college preparatory institution.

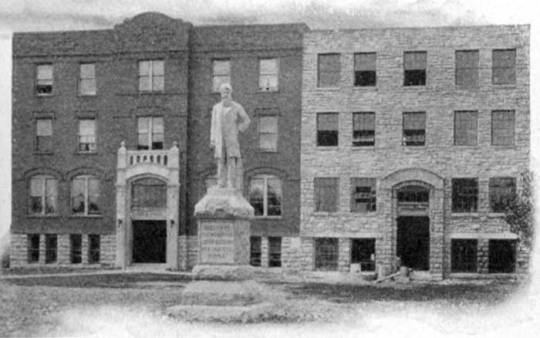

Ward and Parks Halls at Western University in Quindaro, Kansas, 1925

The school’s educational model was Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, which stressed vocational and industrial training for African Americans. However, it would be ten years before the school began to truly operate as a university with an all-black board of trustees and staff.

In 1891, the college was moved from the valley to Ward Hall, which was erected near 27th and Sewell. The church also supported other colleges, and since the Freedmen’s University was its most western institution, the school’s name was changed at that time to Western University.

This new building, Ward Hall, replaced an older former commercial building on Kanzas Avenue. Despite the new facilities, however, enrollment hovered around 12 students for the next four years.

Reverend William Tecumseh Vernon

In the meantime, many former slaves continued to gather in Quindaro to escape from “Jim Crow” laws and establish a better way of life. Several of these people gained employment at some of the local packing and slaughterhouses. By the late 19th century, Quindaro had become mostly African-American.

The arrival of a young new president, Reverend William Tecumseh Vernon, in 1896, revitalized the Western University in the early 20th century. At just 25 years old, Reverend Vernon worked political connections to restore state funding to Western University and to attain a $10,000 appropriation from the Kansas Legislature to spend on a new building and operating expenses. The new building, Stanley Hall, housed the newly formed State Industrial Department. With more state funds, the University soon expanded by building an annex to Stanley Hall, two stock barns, a power plant and reservoir, a girls’ trade building, a boys’ trade building, a girls’ dormitory, and Park Hall, an addition that doubled the size of Ward Hall.

Eva Jessye, a graduate of Western University, made contributions as a singer, actress, choral director, author, and poet.

By 1904, Western University had added architectural and mechanical drawing, carpentry, cabinet-making, printing, wood-turning, business (stenography and typing), dressmaking, tailoring, music, and agriculture programs. It also provided curricula such as theology, classical studies, college preparatory classes, and teacher training. The school became known for its outstanding music program and was said to have been “the best black musical training center in the Midwest.”

Enrollment increased accordingly, and by 1906, the college had 200 students in attendance. That year, Reverend Vernon, who served as president of the school, married Emily Jane Embry, an instructor of Latin and mathematics at Western University. Later that year, Vernon was appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt as Register of the United States Treasury, the nation’s highest governmental post ever occupied by an African American at that time.

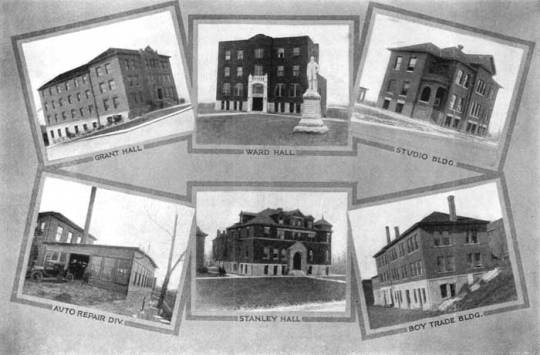

Western University buildings in Quindaro, Kansas, in 1920.

The early 20th-century success of Western University reinforced the shift of Quindaro’s economic center from its original location at the north end of Kanzas Avenue at the bottom of the bluff south to the top of the bluff. In the meantime, the lower commercial townsite was abandoned and became overgrown.

Quindaro’s post office closed in October 1909 as Leavenworth and Kansas City had become major population and economic centers. However, the town soon began to pick up, and general stores, mercantile establishments, and drug stores were opened, and churches and schools were again started, and Quindaro awoke to a ghost of its former life. By 1910, Quindaro was called home to about 500 people, and Western University had a flourishing campus with many fine buildings.

Though Western University is gone today, the John Brown Statue still stands at 27th and Sewell in Kansas City, Kansas, by Kathy Alexander.

In 1911, a statue of abolitionist John Brown was prominently placed on the Western University grounds. The statue was a statement of pride in the area’s association with John Brown and his cause.

At about that same time, former Western University president Bishop William Tecumseh Vernon returned to Quindaro briefly after rejecting a second appointment in the later years of the Taft administration in 1911. By the next year, Vernon was serving as the President of Campbell College in Jackson, Mississippi

At some point, the grade school that had been called the Colored School of Quindaro took on the name of “Vernon School” after the former president of Western University.*

In 1915, Western University became affiliated with the Douglass Hospital when it moved near the college campus. This hospital had been originally chartered in 1899 after four black men, including two doctors, a minister, and a lawyer, had become affiliated with the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1905. At that time, blacks were only able to seek medical care in segregated and inadequate wards of the Kansas City General Hospital. Douglass Hospital was also a training facility and educated students in Western University’s nursing program.

The Quindaro post office was reopened in September 1921.

In the 1920s, Western University reached its peak when 400-500 students a year attended the school. However, circumstances began to interfere with the school’s mission.

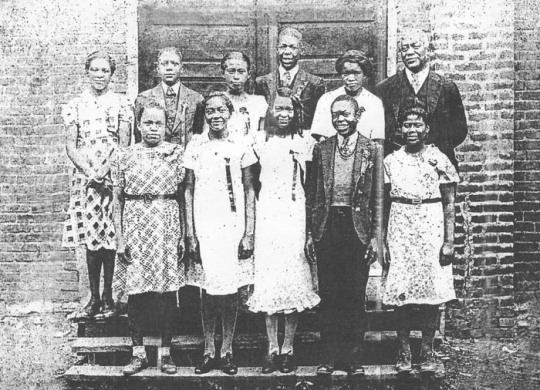

Old Vernon School, Quindaro, Kansas, with Professor King at upper right, 1935.

In 1924, the Vernon School received a new principal. William Franklin King, who had a lifelong teaching career in various towns of Missouri and Kansas, took the position and relocated to Quindaro along with his wife, Mary Hobbs King. Popularly known as “Professor King,” the principal was not only known for his fine educational and administration skills, but he worked hard to ensure that students received a good education and, according to one prior student, “stood for no foolishness.” Professor King would continue to maintain the principal position for the next 12 years until he accepted a position as the principal of the Walker School in South Park, Kansas. He passed away in January 1937 at the Douglass Hospital at the age of 69.

Ward Hall at Western University, Quindaro, Kansas.

In 1924, a severe fire devastated Ward Hall, destroying most of the school’s dormitories. Unfortunately, the African Methodist Episcopal Church did not have the money to replace the facilities. Western University officials also began to quarrel with the church over administrative issues, further complicated by accounting and financial problems in the late 1920s. Afterward, student enrollment continuously dropped, and by 1931, only 182 students were enrolled at Western University.

In the 1930s, construction of a pipeline corridor through the Quindaro townsite damaged or destroyed the remains of Quindaro’s historic storage warehouses along Levee Street and the commercial structures at the intersection of Main Street and Kanzas Avenue.

The Great Depression reduced available financial support for the university at a time when it was facing increasing competition to attract students. The state legislature began to lose confidence in the management of the institution and debated revoking its financial support and accreditation. The African Methodist Episcopal Church withdrew support in 1933, which also negatively impacted enrollment and monetary contributions.

Vernon School in Quindaro, Kansas, by Kathy Alexander.

In 1933, Reverend William Vernon returned to Quindaro to accept an appointment from Governor Alfred Landon as superintendent of the State Industrial Department at Western University. During this time, he also used political clout to help get the funding to build a new Vernon School on the same site as the old Vernon School, which had become overcrowded and dilapidated.

Soon, a new school was under construction by members of the Works Progress Administration to serve the area’s African-American children for grades 1st-8th. While the new building was in the works, students attended classes in the basement of the Methodist Church, which still stands at 3428 N. 29th Street.

The new Vernon School opened in 1936, with Professor William Franklin King serving as the first principal. He continued to serve that first year until he accepted another position elsewhere. The Vernon School was a haven of education for African-American students prior to school integration, which occurred in 1944.

In 1937, the Douglass Hospital moved to 3700 North 27th Street, on the campus of Western University.

In 1938, Reverend Vernon retired from Western University. He died six years later, on July 25, 1944.

After the United States entered World War II in 1941, the draft further diminished enrollment at Western University. The six women of the 1943 high school class were the final graduates of the college. After 78 years of providing a four-year education to African-American students, the school was officially closed in 1944 and was legally dissolved in 1948.

Douglass Hospital in Grant Hall Western University in Quindaro, Kansas.

In 1945, Douglass Hospital renovated the old Western University Grant Hall as a medical facility.

In 1949, an article in the Kansas City Times observed that the Steiner and Zehntner brewery was “virtually the only remaining structure” in Quindaro, stating, “all other buildings are lost from sight and are overgrown with trees and brush.”

Quindaro’s post office closed for good in March 1954.

The Vernon School closed in 1971 after Urban Renewal wiped out most of the homes of children in the area. Today, the Vernon School is on the National Register of Historic Places and is home to the Quindaro Underground Railroad Museum. Here, visitors can see displays, artifacts, and maps of the cooperative efforts of the Native Americans, whites, and free blacks who worked together on the Underground Railroad. The museum also displays information regarding the discovery and exploration of the Quindaro Ruins.

Douglass Hospital occupied the former Western University site for more than 30 years before closing in 1978. Unfortunately, during those years, the hospital demolished the buildings associated with the university and replaced them with two new buildings designed as elderly housing or nursing homes. The closure of the hospital brought an end to more than 120 years of Quindaro’s existence.

Some of these “newer” hospital buildings still stand deteriorating today, but unfortunately, nothing but cornerstones of some early buildings still exist. Some buildings were lost to fire and others to demolition as sites were redeveloped. The last structures remaining were three faculty houses, which were demolished near the end of the 20th century.

The site of Western University and later the Douglass Hospital today, courtesy of Google Maps.

In the late 1980s, a company wanted to build a landfill in the area but encountered an obstacle under the Kansas Antiquities Commission Act, which required that an archeological investigation be conducted. Over a two-year period, a cistern, three wells, and the foundations of 22 residential and commercial buildings were discovered in the 1850s town.

Public outcry over the proposed landfill caused the company to withdraw its interest in the project, and the excavated artifacts were given over to the Kansas Historical Society.

A view from the Quindaro overlook of the old townsite showing Kanzas Avenue and the Missouri River by Kathy Alexander.

The 70.5-acre Quindaro Townsite is now a National Commemorative Site and an archaeological district. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 22, 2002.

In present-day terms, Quindaro was bounded on the north by the Missouri River, on the east by 18th Street, on the south by Brown Avenue, and on the west by 42nd Street. During Quindaro’s boom days, the Missouri River was west of the present location. Kanzas Avenue is now 27th Street. The ruins of Quindaro now belong to the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the City of Kansas City, Kansas. There is a stone platform overlooking the ruins.

Today, Old Quindaro is a living neighborhood that is part of Kansas City, Kansas.

The statue of John Brown, erected in 1911, still stands at 27th and Sewell with a marker that explains the history of Western University. Across the street is the Quindaro Underground Railroad Museum in the old Vernon School. To the north, at 3700 N. 27th Street, are the remaining deteriorating buildings of the old nursing home, and at the end of the street, at a dead-end, is the Quindaro Ruins Overlook. A dirt path extends from the overlook stairs, following the alignment of Kansas Avenue. This path veers west, leading to the cemetery at the northwest before continuing south along what some former residents referred to as “Happy Hollow Road,” now recognized as 31st Street Terrace.

Visitors may also visit the two Quindaro Cemeteries. One is located at 38th and Parallel and has become a part of the Mount Hope Cemetery. The second Quindaro Cemetery is located at 34th and Sewell Avenue.

Old Quindaro Museum in Kansas City, Kansas, by Kathy Alexander.

The Old Quindaro Museum at 3432 N 29th Street, which has long preserved the overall importance of the African-American Community of Quindaro, appears to be closed as of this writing.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated October 2023.

Also See:

African American History

Kansas City, Kansas

0 notes

Text

Man Pleads Guilty to Distributing Fentanyl That Caused Fatal Overdose

Faces at Least 20 Years in Prison KANSAS CITY, Mo. – A Rock Port, Mo., man pleaded guilty in federal court today to selling fentanyl to another Atchison County, Mo., man that resulted in his fatal overdose. Quentin W. Carder, 23, pleaded guilty before U.S. District Judge Howard F. Sachs to one count of conspiracy to distribute fentanyl and cocaine, which caused the death of another person, and…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

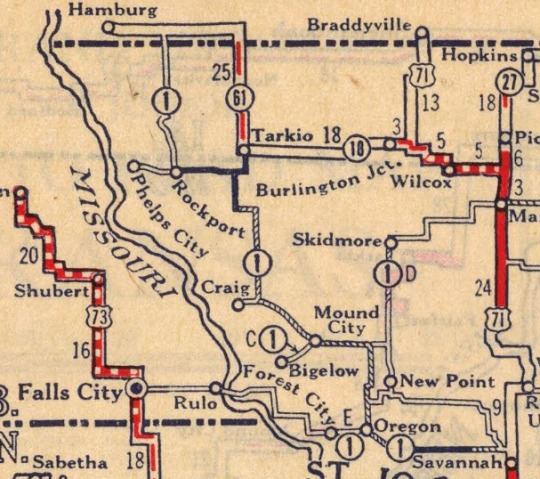

American Auto Trail-Missouri Route 1 (Mound City to Fairfax MO)

American Auto Trail-Missouri Route 1 (Mound City to Fairfax MO) https://youtu.be/-jBGHMhKZ7g This American auto trail explores the former Missouri Route 1, from Mound City to Fairfax, Missouri.

View On WordPress

#4K#american history#Atchison County#Auto trail#Craig#driving video#Fairfax#Holt County#missouri#missouri river#Mound City#road travel#slow travel

0 notes

Text

Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad

Explorers of the Mojave Desert in southern California are bound to have heard the stories of the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad. The Tonopah and Tidewater flanks the western edge of the Mohave National Preserve as travels south to north from Ludlow, California to Beatty, Nevada and up to Tonopah, Nevada utilizing the Bullfrog Goldfield Railroad. Many of the off ramps, sites and historic monuments…

View On WordPress

#Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad#California#Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad#Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad#Nevada#Nye County#San Bernardino#Santa Fe Railway#Tonapah & Tidewater Railroad

0 notes

Text

KDOT Lettings: January 2023

There are 23 projects up for bids at KDOT on January 18

There are 23 projects up for bids on January 18 Federal-Aid: 73-3 KA 3889-01: Replacement of Bridge #014 over Walnut Creek Drainage on US 73/K-7 in southern Atchison County. One lane of traffic to be carried through the work zone, controlled by signals. 435-46 KA 5500-02: Guardrail upgrades on I-435 from K-10 to Midland Drive. 635-46 KA 5501-02: Guardrail upgrades on I-635 in Johnson…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Diablo Canyon

#ATSF#AZ#Arch#Arch Bridge#Arizona#Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe#Bridge#Canyon Diablo#Canyon#Coconino#Coconino County#Railroad#Santa Fe#Santa Fe Railroad#Steel Arch

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1883, less than 20 years after emancipation, Curtis Gentry bought nearly 1,500 acres of undeveloped land in Shiloh, a rural community in the Alabama county where he had once been enslaved. Alongside his brother Turner, with whom he was able to reunite after emancipation—unlike the members of so many other Black families—Gentry cleared that property, uprooting trees, brush, and undergrowth. Once the land was arable, he planted and harvested an array of crops, including ribbon cane, corn, and peas.

“He was a hard worker,” Bernice Atchison, Gentry’s granddaughter-in-law, told me. “Not only did he clear his own land, but he took jobs helping white people clear their land.” He taught his family how to take care of the farm while he worked on other people’s farms, bringing in extra money to the household.

Gentry’s children continued to farm after their father’s death, and each subsequent generation was trained in the ways of tending to their inherited land trust. When Atchison married Gentry’s grandson Allen in 1953, the young couple were given charge of nearly 280 acres of farmland, which included amenities built by those who came before. “We had a ribbon cane mill that made syrup. We had a saw mill. There was an old still that they had used to make whiskey back in those days,” Atchison said. “I loved farming, because you have to come to understand the land.”

In 1959, the Atchisons bought another 39 acres, and two years later, they built a house in which they would raise eight children. The couple sold vegetables and produce to loyal customers, most of whom worked in nearby factories and plants. In 1981, just after the Atchisons were certified as United States Department of Agriculture pig breeders, they received a letter from the USDA notifying them that they qualified for federal loans to buy “farrowing pens for the sows to have their little babies in,” Atchison said. She and Allen had spent years helping neighbors build their own farrowing pens, which had been paid for with USDA farm subsidies. “Helping Mr. Waldruf and Mr. Jones and Mr. Scott, we saw that the loan program had worked for them. So we went down to the USDA to get the money to build ours,” she said.

But there was a crucial difference. “They were white, and we were Black,” Atchison explained.

👉🏿 https://www.thenation.com/article/society/black-farmers-pigford-debt/

👉🏿 https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/losing-ground/id1036276968

👉🏿 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pigford_v._Glickman

#politics#usda#black farmers#pigford v glickman#racism#white privilege#reparations#farmers#farm workers

701 notes

·

View notes