#Quindaro

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

so since June I've been interning in a very cool history research lab project (paid, I might add) focused on black and indigenous history in Ohio. We spent a month learning to do real research (which I knew Nothing about, and that was my prime motivation for applying for this thing) including trips to museums, archives, meeting with descendants of groups/settlements we were studying and then doing a variety of research depending on where we focusing that week. Very cool!

Then in July we've each picked an area to continue researching on our own for. I'm working on studying a couple different mixed race settlements, including 2 Wyandot settlements, one set up before Removal, and the other after. The latter is Quindaro, Kansas, which is a ghost town now but like. This fucking town.

I want a Deadwood-style show about this place. I am not above attempting to write a full on book about it despite being an amateur in hopes of getting a Deadwood-style show about it.

It's a few years pre-Civil War, Kansas territory has been opened for settlement, and pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions are desperate to flip the state for their cause. There are already a couple pro-slavery settlements in place (particularly Wyandot) and the opposition is trying to get a foothold in as well.

Meanwhile the Wyandot tribe was getting pushed out of Ohio and forced into Kansas and even though they were promised treaty land, end up having to buy it themselves.

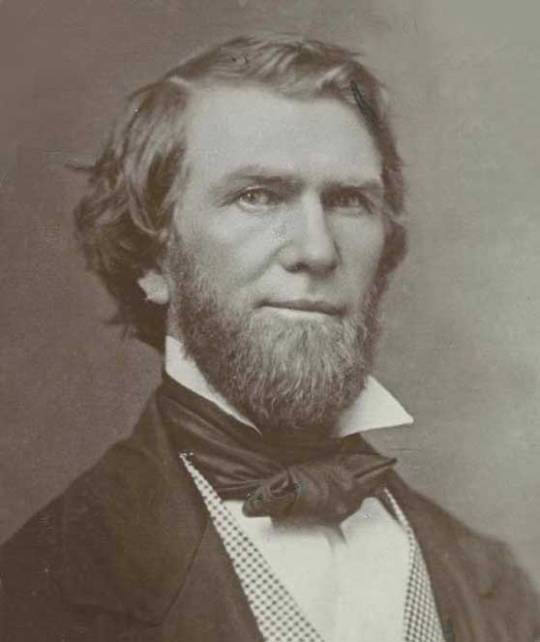

(also tumblr spell check doesn't recognize "Wyandot," and I'm putting that down as a microaggression. Anyway.) This guy, Abelard Guthrie, who's an attorney, and abolitionist, and is married to a Wyandot woman, manages to convince the Wyandot and some backing companies to establish an anti-slavery town on reservation land. They set up the town as a company, with the majority of the land under ownership of a group of individuals (most Wyandot) with Abelard as vp. They name it Quindaro, for his wife's Wyandot name.

Now Abelard and his wife Nancy's story is interesting enough-- supposedly her dad hated Abelard and hoped the relocation would end the relationship; Abelard wouldn't be put off and followed them to buttfuck Kansas anyway; Nancy's dad even tried to press charges claiming Abelard had taken shots at him (no idea yet how that went!)

But the town itself has so much going on! It was a racially mixed community, with the black population growing exponentially once the war broke out. The Wyandot originally owned most of the land and ran a bunch of local businesses, including the hotel (current Kansas Wyandot Chief Judith is actually descended from that guy!) It was predominantly a passionately anti-slavery population (and in competition with its pro-slavery neighbors as a result) meanwhile the president of the town company, Joel Walker, was not only from a prominent Wyandot family but also strongly pro-slavery and may have even owned slaves. Like I need to know what everyday business was like between these people.

They had a local newspaper published by this guy, Morgan, who had his hands in dozens of pies and ended up a Methodist minister; initially it also has a woman assistant editor, Clarina Nichols, who's a woman's right activist and an abolitionist, and for whom this is far from her first or last rodeo. They also had a fucking cannon they nicknamed Lazarus that they had to smuggle in to avoid it getting stolen by their rivals in Wyandot, which eventually got donated to the Union once war broke out. Eventually the pro-temperance faction in town was able to get prohibition passed, and groups went around busting whiskey casks, while for months after people were getting in trouble for having their stash discovered. The town was also seemingly heavily involved in the underground railroad-- to the point that pro-slavery hooligans from Missouri rammed and sank the town's ferry, convinced it was being used to transport escaped slaves. William Tecumseh Sherman lived there for awhile and might have practiced law there for a bit, and there's a (probably legendary) story that John Brown stayed there for a few days. Outside town there was a tavern that served as a pit-stop for the local stagecoach, originally run by a Wyandot guy (who I have not been able to find anything about) but which (esp once the war starts) is such a hang out for gangs of raiding soldiers that the locals (unsuccessfully) try to burn it down. Also the school that's founded there for free black students outlives the town to become Western University.

Once the town was no longer the only anti-slavery bulwark in Kansas it started to become less prosperous. Other regional issues, like a financial panic and a grasshopper invasion only worsened things. The town company partners started to fall out, and the Wyandot, for whom Abelard has been acting as tribal attorney, fired him. So the town is going belly up and Abelard is trying to sue his business partner for mismanagement-- meanwhile at some point Nancy's sister Margaret moved in with her and Abelard (I knew that already from tracking the family through like every census ever) and in the middle of suing people Abelard reportedly chases down and horsewhips the town company treasurer for having seduced Margaret, who was apparently "feeble-minded"?

The Civil War really devastated Quindaro though, first by causing the majority of the male population to abandon the place and enlist; then when soldiers getting stationed there decided to tear the place apart for firewood and supplies.

However a bunch of free and escaped black families start moving in around this time, and the Wyandot who had chosen to move into Indian Territory get pushed back to Quindaro to avoid the Confederates. So for awhile the population is bolstering and although the town isn't doing financially Great it's not the end yet. Abelard Guthrie, who by this time is obsessed with recouping his losses and is trying to petition the govmt to give his wife reserve lands from her mom's side (Shawnee), becomes legal representative to the new Wyandot group, too! And seems to have basically used that as a way of combining his ambitions with the Wyandot's whenever possible. He dies in fucking Washington DC still trying to get a Shawnee reserve grant under Nancy's name.

(The face of a man I would not be shocked to discover was of "excitable disposition.")

Anyway though, the town decays and recovers in leaps and starts-- a lot of it ends up just completely abandoned, while other parts get enveloped by Kansas City-- I think most of it is in ruins now but since the 80s they've worked on protecting the remains and now there are bunch of historic trails and stuff through the area.

I've barely scraped the surface on this place, and I want to know so much more about the personalities. My next goal in my research is to start tearing through the town newspaper; then it's probably going to be back to census-reading for awhile.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

quindaro - Google Search

Quindaro, Kansas – A Free-State Black Town

Western University in Quindaro, Kansas.

Quindaro, Kansas, an old historic town of Wyandotte County, was situated on the south bank of the Missouri River. Though the town is extinct today, it has a rich history, and there is still a Quindaro neighborhood in Kansas City, Kansas today.

Missouri River near Kansas City, Kansas by Laura Ziegler/KCUR

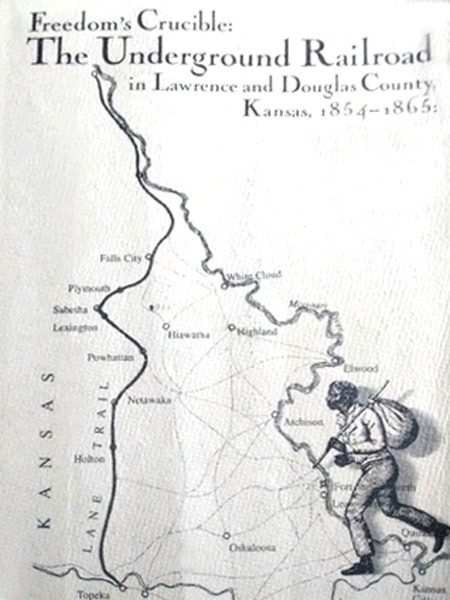

A settlement was established on the Quindaro Bend of the river in about 1850 because it was located across from Missouri, a slave state. At that time, it was a stop along the Underground Railroad. After the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed in 1854, a western branch of the Underground Railroad was developed in Kansas that linked Quindaro to the Lane Trail and provided a new route of escape for slaves from Missouri.

Early residents, who were known as “Seekers of Freedom” because of their escaped slave status, included the families of Turner, Banks, Marshall, Grigsby, Harris, Endicott, Barnett, Duncan, Creek, Graves, Murray, and Sanders.

The old Quindaro Cemetery, established in 1853, is the oldest in the state.

Abolitionists developed the town after the Kansas-Nebraska Act passed in 1854 to create a free state port of entry into Kansas Territory. As the only free-state river port in Kansas, six steamboats a day were soon landing there.

Nancy Quindaro Brown Guthrie

At that time, the land was part of an area that the Wyandot Indians had purchased from the Delaware tribe. When the Wyandot tribe disbanded, the land was divided among tribal members who wished to remain in the area and become U.S. citizens. Among these people were Abelard Guthrie and his wife, Nancy Quindaro Brown Guthrie, for whom the town was named. Mrs. Guthrie was a Wyandot lady of royal blood whose father was chief of the Canadian Wyandot.

The townsite at that time was located six miles above Kansas City, Kansas (then called Wyandotte.)

In 1856, the pro-slavery river port towns of Atchison, Leavenworth, and Delaware City were practically closed to Free State settlers, and several fugitives from these settlements were assisted down the river to safety by Mr. Guthrie, who owned much of the land in the vicinity. It was during these years, before Kansas was established as a free state, that the underground railroad was so important. By this time, pro-slavery factions were establishing blockades on the Missouri River to prevent Free State supporters from accessing supplies and reinforcements as well as blocking their travel.

Tensions between pro and anti-slavery groups caused several instances of armed violence and death in the Missouri-Kansas Territory border region that increased the urgency of the abolitionist cause and the need to establish a Free State river port. In September of 1856, Charles Robinson and Samuel Simpson, two men formerly associated with the New England Emigrant Aid Company, approached Abelard Guthrie about the prospect of starting a Free State town on the Missouri River.

Abelard Guthrie

In the fall of 1856, the Quindaro Town Company was formed by an alliance of Wyandot Indians and Free-State supporters. The site on Quindaro Bend was at a point six miles above the mouth of the Kansas River, where a fine natural rock ledge stood, and the river ran along the bank six to twelve feet deep, making a convenient landing. Plenty of wood and rock were at hand for building purposes, and fertile land was adjacent.

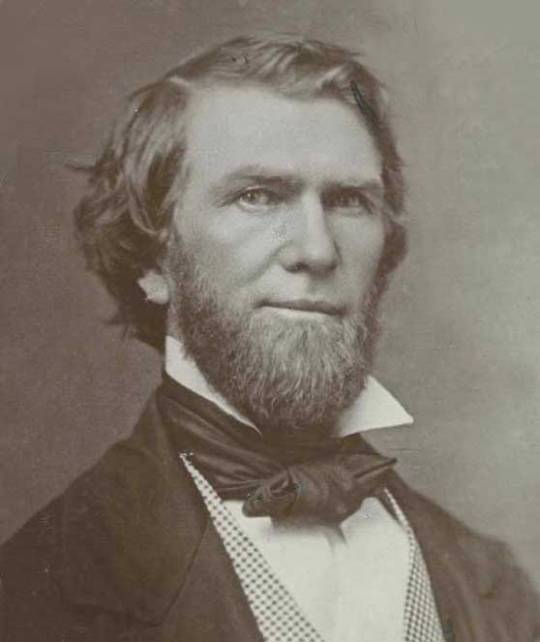

In December 1856, the town was surveyed by P.H. Woodward and platted by Owen A. Bassett. The northern boundary of the town coincided with the Missouri River, upon which a wharf facilitated steamboat landings.

Two commercial thoroughfares, named Levee and Main Streets, ran perpendicular to the river and the town’s primary commercial thoroughfare, named Kanzas Avenue, which now aligns with the present-day 27th Street. The Quindaro Townsite plat included Quindaro Park, one of the first public parks in Kansas.

Quindaro, Kansas Plat Map 1856

The sale of lots and the construction of buildings in Quindaro began in January 1857. By the end of the month, an 8×10 foot temporary office for the Quindaro Town Company, the townsite’s first building, was completed. The first business in Quindaro, the W.J. McCown Store, opened in March on Main Street near the town’s steamboat landing. The establishment of the Quindaro Steam Saw Mill Company in April on Levee Street dramatically increased the pace of building in the new town. Owned by Otis Webb and A.J. Rowell, the mill was the largest of its kind in Kansas Territory.

By April 1, three or four buildings were completed, including the five-story Quindaro House, the second-largest hotel in the territory. The hotel, operated by Philip T. Colby and Charles S. Parker, located at 1-3-5 Kanzas Avenue, also featured the Johnson and Veale Merchants store on the first floor as well as the Quindaro Post Office, established that May.

“There is a farm here for everyone who will come and take possession, a soil whose richness is unsurpassed in the country, a climate unequaled, and a population who are brave, generous, and hospitable. So come on where there is room enough and to spare.” — Hillsdale, Michigan Standard, March 17, 1857

Word-of-mouth that the Quindaro steamboat landing was the best point of entry into Kansas for Free State settlers only served to attract more people to the town. The Quindaro wharf on the Missouri River was completed by May of 1857, reportedly facilitating 36 steamboat landings in one week.

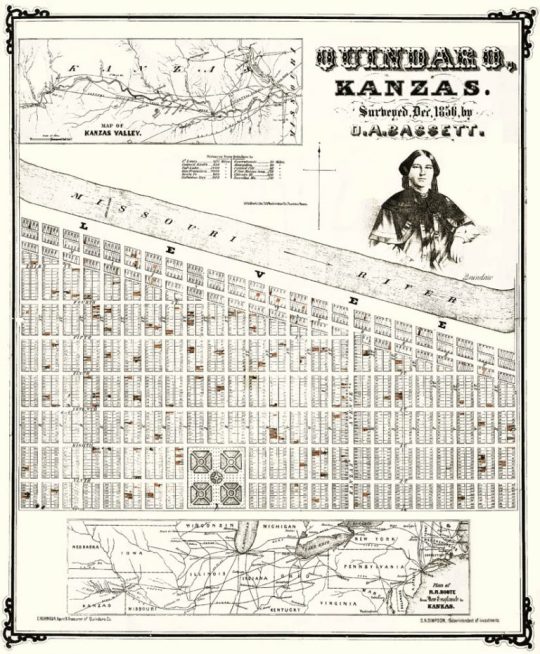

Carriage-Wagon Shop in Quindaro, Kansas.

That same month, a large group of men began to grade the ground near the levee and Kanzas Avenue, which was the main street running south from the river. This commercial corridor was developed in a manner that provided easy access to the town’s wharf and riverfront, facilitating the import and export of goods. Rows of warehouses, predominantly used for storage, lined Levee Street near the wharf, while commercial businesses were located along Main Street, concentrated at the intersection of Main Street and Kanzas Avenue and continuing south along Kanzas Avenue for a block and a half to Sixth Street.

Construction of a road from Quindaro to Lawrence began almost immediately. By May, Alfred Robinson had built a livery stable and established a stagecoach line that charged $3.00 for the six-hour coach trip to Lawrence. Another road traveled south from Kanzas Avenue to the town of Wyandotte (this road eventually became present-day Quindaro Boulevard.) A third road led south to the Shawnee Reserve and linked Quindaro with the Santa Fe and Oregon Trails.

Jacob Zehntner and Henry Steiner built this brewery at 45 N Street, on the west side of Quindaro Creek, in 1857 by Kathy Alexander.

Ebenezer O. Zane’s Wyandotte House Hotel was located across Kanzas Avenue from the Quindaro House Hotel. The J.P. Upson Building was located at 7 Kanzas Avenue, south of the Quindaro House Hotel, and contained the office of the town’s weekly newspaper.

Jacob Zehntner and Henry Steiner built a brewery at 45 N Street, on the west side of Quindaro Creek, in 1857. The main brewery building was a two-story brick and stone structure with a taproom, vaulted beer cellar, and living quarters. Today, its ruins are the only visible remains above ground of the Old Quindaro townsite.

On May 3, a schoolhouse was opened, which also served as a church on Sunday.

The first newspaper, the Chin-do-wan (a Wyandot word meaning leader), owned by Edmund Babb and John M. Walden, appeared on May 13, 1857, and at once began to advertise the new town. John Walden was also a missionary to the freedmen, was involved in the Underground Railroad, and later became a bishop in the Methodist Church. The associate editor of the abolitionist newspaper was Clarina Nichols, who was involved in the temperance, abolition, and suffrage movements in the 19th century. A friend of Susan B. Anthony and a fellow crusader for the rights of women and children, she was also an important Conductor and Station Master of the Underground Railroad. Nichols reported that many slaves took the underground railroad at Quindaro, and she left a letter telling about a time when a Freedom Seeker named Caroline was brought to her home. She hid her in an empty cistern overnight and then sent her on the road North as soon as it was safe.

Clarina Irene Howard Nichols

“My cistern – every brick of it rebuilt in the chimney of my late Wyandotte home – played its part in the drama of freedom. One beautiful evening late in October ’61, as twilight was fading from the bluff, a hurried message came to me from our neighbor – Fielding Johnson – ‘You must hide Caroline. Fourteen slave hunters are camped on the Park – her master among them.’ … Into this cistern Caroline was lowered with comforters, pillow, and chair. A washtub over the trap with the usual appliances of a washroom standing around, completing the hiding.”

— Clarina Nichols

The first issue of the newspaper reported that trees had been removed from several acres of the townsite and that 30-40 houses had been built and occupied, and that 16 business houses were in the process of erection. By August, the first brick house was under construction on “P” street, the bricks having been burned on the townsite, and soon a brickyard was established.

One of the earliest problems of the new town was to gain recognition by the steamboats. These crafts were Missouri-owned and operated, and their officers refused to stop at Quindaro or even denied that such a place existed. Later, they actively sought to get passengers to pass up Quindaro to land at Leavenworth or Wyandot, both of which were pro-slavery towns.

Steamboat on the Missouri River

A threat to start a Free-State steamboat line from Alton, Illinois, to Kansas, broke up this racket as the pro-slavery boatmen didn’t want such competition.

The Quindaro post office opened on May 14, 1857. Professional men came in, and real estate agents did a good business. F. Johnson and George Veale opened a general merchandise store and were followed by other firms in the same line. Simpson, Macaulay & Smith, forwarding and commission merchants, also opened a store. Charles B. Ellis, a civil engineer and surveyor, opened an office, and Quindaro was soon believed to become one of the largest towns on the river.

Thaddeus Hyatt brought the 100-foot Lightfoot Ferry to Quindaro and completed a few trips to Lawrence via the Kansas River before transitioning service to the Missouri River, which was more navigable. The 100-foot Otis Webb Ferry was also put into operation, offering daily trips between Quindaro and Parkville, Missouri, located two miles up the Missouri River, and occasional trips to the towns of Wyandotte (Kansas City) or Leavenworth.

Temperance Movement

Quindaro was a temperance town, the lots having been deeded with the stipulation that liquor dealers should not occupy them. However, some groggeries crept in, and by June 1857, the women petitioned, and the men acted to clean them out. This induced many emigrants, especially women, to prefer Quindaro to other towns.

Dr. George E. Budington advertised as a physician; Ireland & McCorkle were carpenters and joiners; Fred Klaus, a stone cutter and mason, had a quarry a short distance from town; A. C. Strock & Co. operated a drug store, and Dr. J. B. Welborn had an office in the same building; William Shepherd and D. D. Henry established a hardware store. Mr. Robinson, Gray, Johnson, Webb, and others were rushing around for subscriptions to build the Quindaro, Parkville & Burlington Railroad to obtain a connection with the Hannibal & St. Joe Railroad. By fall, the Methodist Church was built.

Quindaro’s residents also worked to create social institutions and hold cultural events, including a Quindaro Literary Association and a Quindaro Library Association, outfitted with over 200 books. The Literary Association published a journal edited by Clarina Nichols called The Cradle of Progress and held meetings and public lectures in a residence at 62 P Street, a house that would later be called “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and was associated with Underground Railroad activity.

Underground Railroad in Kansas

Through the end of 1857, Quindaro had rapidly developed into a booming pioneer river port town, with stores, hotels, churches, and residences constructed across the steep landscape to support its growing population. The lower townsite near the river was the commercial core, and most residences were higher on the bluff at the upper townsite.

In these early years, Quindaro became an important station on the Underground Railroad, with slaves escaping from Platte County, crossing the river in small boats, and making secret runs of the Parkville-Quindaro Ferry. The runaways hid with local farmers before traveling to Nebraska for freedom.

Quindaro, a Wyandot word translated to “In union there is strength,” fit the town well as there was no end of public confidence in the future of the town that was expected to rival Kansas City, Leavenworth, Atchison, and Wyandotte (Kansas City.)

At the time that the city charter was first approved in January 1858, Quindaro had a population of 800 and boasted 100 buildings, many of which were built of stone and brick that were of a substantial, metropolitan appearance. Businesses included two hotels, a hardware store, three dry goods stores, four groceries, a clothing store, two drug stores, two meat markets, two blacksmiths, a wagon shop, six boot and shoe shops, and a livery stable. There were also four doctors, three lawyers, two surveyors, and several carpenters and builders, as well as two churches and a schoolhouse.

Chin-do-wan Newspaper, 1857

The Chin-do-wan kept up its trumpeting and was bought by V. J. Lane, G. W. Veale, and Alfred Gray, who also published the Kansas Tribune in the fall and winter of 1858-59. The publication was continued for the benefit of the town company until 1861 when it was removed to Olathe.

Quindaro was thought to have reached a peak population of as many as 1,200 people. But Kansas City, Atchison, and Leavenworth were rapidly becoming centers of population and trade, and as they were the natural gateways of the territory, Quindaro began to decline.

The 1860 federal census recorded a population of 689, with a majority (92%) of residents being white, 4% black or “mulatto”, and 4% American Indian. The Census does not indicate whether the black residents were escaped slaves or freedmen. The most common occupation was “farmer,” followed by “laborer.” At the same time, the rest of the males of working age held positions that supported the town, such as hotel keepers, masons, engineers, carpenters, merchants, tinsmiths, bricklayers, and blacksmiths. A lease in 1860 established the right-of-way for the Missouri Pacific Railroad through Quindaro parallel to the Missouri River. The railroad company built the tunnel overpass that crosses 27th Street near the Missouri River.

In the next year, business houses moved to the more prosperous settlements, and the population gradually dwindled.

Underground Railroad by Charles T. Webber, 1893.

When Kansas was established as a free state in January 1861, there was less need for the port, and the growth slowed in the commercial district. At the same time, the economy in Kansas was also suffering from over-speculation. Then, with the opening of the Civil War in April, the town was abandoned by most of the inhabitants. The young men enlisted, and many of their families moved to other communities for safety.

The ferry from Parkville to Quindaro was reputed to be transporting runaway slaves across the river at night when pro-slavery forces sank it in 1861. In January 1862, a man named George Washington escaped from slavery near Parkville, Missouri by crossing the frozen Missouri River on foot. He made it to Quindaro by following pieces of cloth tied to trees by an Underground Railroad “conductor.” Washington then joined the 1st Regiment Kansas Colored Volunteers to fight for the Union in the Civil War.

Cavalry Training in the Civil War

For the dying town, matters were made worse when, from January 20 to March 12, 1862, the Ninth Kansas Volunteer Infantry under Colonel Alson C. Davis, was quartered in the empty business buildings of Quindaro as the troops underwent a reorganization to become the Second Kansas Cavalry. Unfortunately, officer control of the soldiers was slack, and the troops literally destroyed the commercial and residential buildings, tearing up everything movable for firewood and leaving shells where prominent buildings and houses once stood. Once the soldiers were gone, weather, fires, and theft finished them off in the next years.

The town’s charter was revoked by the Kansas State legislature in 1862, and the Quindaro Town Company was dissolved. However, several African Americans remained in the dead town, and Presbyterian minister Eben Blachly started classes in his home for the children of former slaves the same year.

Fugitive Slave

Though Quinidaro as a town was finished, its role as a major stop on the Underground Railroad had already been cast, and its story was far from over. During the Civil War, a number of African-American families escaped from slavery in the surrounding states and established their homes in “Old Quindaro.”

After the Union won the Civil War and the slaves were emancipated, many of them were drawn toward Quindaro because of its anti-slavery history. They settled on the mostly abandoned townsite occupying the empty buildings, particularly in the valley around Quindaro Creek. Newcomers to the area lived and farmed near the town in an area that came to be known as “Happy Hollow” to the west of Quindaro. Individuals and families farmed their own land or worked for the remaining white population. During this time, there was no center of commerce nor organized social, political, or economic structure, and most of the buildings were residential.

For a while, Quindaro served as an outfitting post for freight wagon trains. However, as railroad commerce surpassed river transportation, Quindaro’s steamboat landing languished, and the town’s economic prospects ceased.

By 1865, there were 429 African Americans living in the townsite, and a group of Quindaro citizens, with Reverend Blachly at the lead, opened the Quindaro Freedman’s School (later Western University), the first black school west of the Mississippi River and the only one ever to operate in the state of Kansas. The school was officially chartered in 1867 and was supported through donations, with only two teachers throughout its existence, Eben and Jane Blachly.

The private school operated under the Presbyterian Church and initially utilized available space in existing buildings. The school may have briefly operated from the Steiner and Zehntner Quindaro Brewery, although it occupied a former commercial building on Kanzas Avenue by 1870.

Later-arriving African-American residents settled in the upper town on the bluff. Difficulties in reaching the interior from below the bluff hampered commerce, and changes after the war reduced the need for the port.

By 1870, only a few original buildings and the Missouri Pacific Railroad station were still used. A map of the time showed a few businesses and residences in Quindaro, including Cyrus Taylor’s wagon manufacturing shop, W.J. Heaffaker’s dry goods and variety store, the D.R. Emmons & Company grocery store, a chair factory at the northwest corner of M and 8th streets, and the farms of Alfred Gray, E.D. Brown, and Thomas McIntyre. Also shown were the town’s white and black schools, the Methodist and Congregational churches, and Freedmen’s University housed within former commercial buildings at 34-40 Kanzas Avenue.

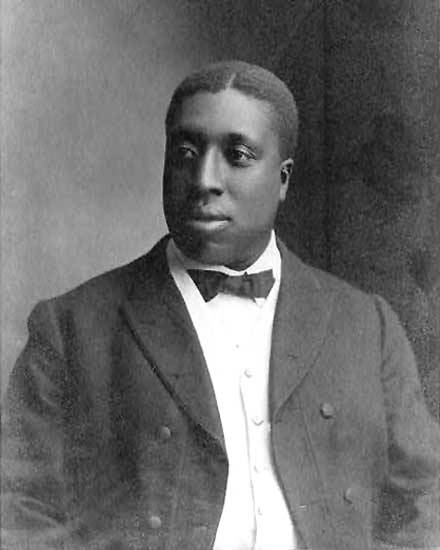

Charles Henry Langston

After being abandoned, the early lower commercial townsite became overgrown, with some areas covered by earth falling from the bluffs. A visitor in 1873 found the town’s former commercial district abandoned, writing, “One store with a granite front and iron posts stood as good as new and various other buildings were in good preservation, but empty.”

In the 1870s, property owners in the area donated land from the heart of the townsite to the school, and buildings were erected. In 1872, the Kansas State Legislature established the “Colored Normal School,” a teachers’ college, within Freedman’s University, as a way to create a self-sustaining educational institution and promote education throughout the area. At that time, Charles Henry Langston, a leading black abolitionist, activist, educator, and politician in Ohio and Kansas, became the principal.

The University struggled initially due to the inability of students to pay, which was common among contemporary African-American schools, and the lack of funding from the state, whose coffers were greatly depleted by widespread agricultural losses in 1873.

Exodusters En Route to Kansas, Harper’s Weekly 1879

Though the enrollment was beginning to surge, the college struggled to survive in the troubled mid-1870s, and in 1879, the school’s trustees took out a mortgage on part of the property in an attempt to keep the school open. Reverend Eben Blachly ran the school until his death in 1877, at which time the school became inactive for a short period.

When the last Federal troops left the southern states in 1877, Reconstruction gave way to renewed racial oppression and rumors of the re-institution of slavery. Fearful for their lives, many African Americans began to flee the south for Kansas in 1879 and 1880 because of the state’s fame as a Free-State and the land of the abolitionist John Brown. These people were called Exodusters. Many of them settled in Quindaro, generating renewed interest in Freedman’s University for a brief period of time, beginning in 1879. In 1881, the African Methodist Episcopal Church, under the direction of local community leader and elected official Corrvine Patterson, assumed control of the institution and converted it to a vocational/college preparatory institution.

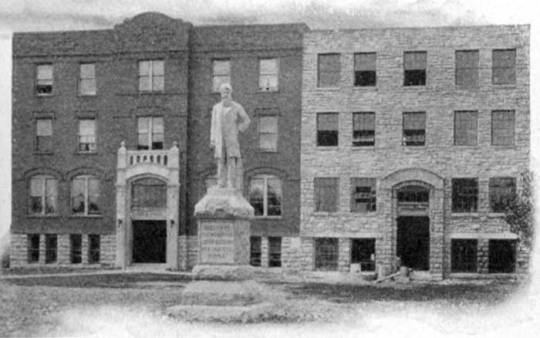

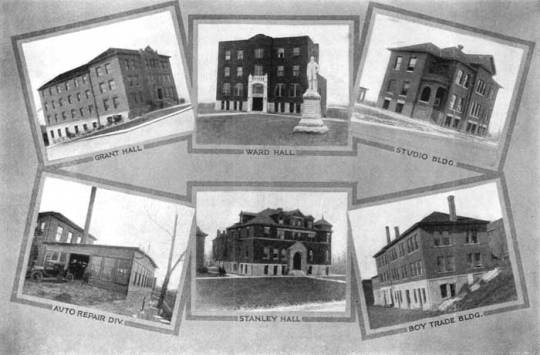

Ward and Parks Halls at Western University in Quindaro, Kansas, 1925

The school’s educational model was Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, which stressed vocational and industrial training for African Americans. However, it would be ten years before the school began to truly operate as a university with an all-black board of trustees and staff.

In 1891, the college was moved from the valley to Ward Hall, which was erected near 27th and Sewell. The church also supported other colleges, and since the Freedmen’s University was its most western institution, the school’s name was changed at that time to Western University.

This new building, Ward Hall, replaced an older former commercial building on Kanzas Avenue. Despite the new facilities, however, enrollment hovered around 12 students for the next four years.

Reverend William Tecumseh Vernon

In the meantime, many former slaves continued to gather in Quindaro to escape from “Jim Crow” laws and establish a better way of life. Several of these people gained employment at some of the local packing and slaughterhouses. By the late 19th century, Quindaro had become mostly African-American.

The arrival of a young new president, Reverend William Tecumseh Vernon, in 1896, revitalized the Western University in the early 20th century. At just 25 years old, Reverend Vernon worked political connections to restore state funding to Western University and to attain a $10,000 appropriation from the Kansas Legislature to spend on a new building and operating expenses. The new building, Stanley Hall, housed the newly formed State Industrial Department. With more state funds, the University soon expanded by building an annex to Stanley Hall, two stock barns, a power plant and reservoir, a girls’ trade building, a boys’ trade building, a girls’ dormitory, and Park Hall, an addition that doubled the size of Ward Hall.

Eva Jessye, a graduate of Western University, made contributions as a singer, actress, choral director, author, and poet.

By 1904, Western University had added architectural and mechanical drawing, carpentry, cabinet-making, printing, wood-turning, business (stenography and typing), dressmaking, tailoring, music, and agriculture programs. It also provided curricula such as theology, classical studies, college preparatory classes, and teacher training. The school became known for its outstanding music program and was said to have been “the best black musical training center in the Midwest.”

Enrollment increased accordingly, and by 1906, the college had 200 students in attendance. That year, Reverend Vernon, who served as president of the school, married Emily Jane Embry, an instructor of Latin and mathematics at Western University. Later that year, Vernon was appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt as Register of the United States Treasury, the nation’s highest governmental post ever occupied by an African American at that time.

Western University buildings in Quindaro, Kansas, in 1920.

The early 20th-century success of Western University reinforced the shift of Quindaro’s economic center from its original location at the north end of Kanzas Avenue at the bottom of the bluff south to the top of the bluff. In the meantime, the lower commercial townsite was abandoned and became overgrown.

Quindaro’s post office closed in October 1909 as Leavenworth and Kansas City had become major population and economic centers. However, the town soon began to pick up, and general stores, mercantile establishments, and drug stores were opened, and churches and schools were again started, and Quindaro awoke to a ghost of its former life. By 1910, Quindaro was called home to about 500 people, and Western University had a flourishing campus with many fine buildings.

Though Western University is gone today, the John Brown Statue still stands at 27th and Sewell in Kansas City, Kansas, by Kathy Alexander.

In 1911, a statue of abolitionist John Brown was prominently placed on the Western University grounds. The statue was a statement of pride in the area’s association with John Brown and his cause.

At about that same time, former Western University president Bishop William Tecumseh Vernon returned to Quindaro briefly after rejecting a second appointment in the later years of the Taft administration in 1911. By the next year, Vernon was serving as the President of Campbell College in Jackson, Mississippi

At some point, the grade school that had been called the Colored School of Quindaro took on the name of “Vernon School” after the former president of Western University.*

In 1915, Western University became affiliated with the Douglass Hospital when it moved near the college campus. This hospital had been originally chartered in 1899 after four black men, including two doctors, a minister, and a lawyer, had become affiliated with the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1905. At that time, blacks were only able to seek medical care in segregated and inadequate wards of the Kansas City General Hospital. Douglass Hospital was also a training facility and educated students in Western University’s nursing program.

The Quindaro post office was reopened in September 1921.

In the 1920s, Western University reached its peak when 400-500 students a year attended the school. However, circumstances began to interfere with the school’s mission.

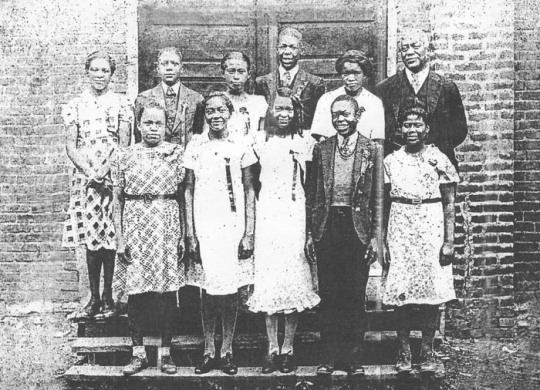

Old Vernon School, Quindaro, Kansas, with Professor King at upper right, 1935.

In 1924, the Vernon School received a new principal. William Franklin King, who had a lifelong teaching career in various towns of Missouri and Kansas, took the position and relocated to Quindaro along with his wife, Mary Hobbs King. Popularly known as “Professor King,” the principal was not only known for his fine educational and administration skills, but he worked hard to ensure that students received a good education and, according to one prior student, “stood for no foolishness.” Professor King would continue to maintain the principal position for the next 12 years until he accepted a position as the principal of the Walker School in South Park, Kansas. He passed away in January 1937 at the Douglass Hospital at the age of 69.

Ward Hall at Western University, Quindaro, Kansas.

In 1924, a severe fire devastated Ward Hall, destroying most of the school’s dormitories. Unfortunately, the African Methodist Episcopal Church did not have the money to replace the facilities. Western University officials also began to quarrel with the church over administrative issues, further complicated by accounting and financial problems in the late 1920s. Afterward, student enrollment continuously dropped, and by 1931, only 182 students were enrolled at Western University.

In the 1930s, construction of a pipeline corridor through the Quindaro townsite damaged or destroyed the remains of Quindaro’s historic storage warehouses along Levee Street and the commercial structures at the intersection of Main Street and Kanzas Avenue.

The Great Depression reduced available financial support for the university at a time when it was facing increasing competition to attract students. The state legislature began to lose confidence in the management of the institution and debated revoking its financial support and accreditation. The African Methodist Episcopal Church withdrew support in 1933, which also negatively impacted enrollment and monetary contributions.

Vernon School in Quindaro, Kansas, by Kathy Alexander.

In 1933, Reverend William Vernon returned to Quindaro to accept an appointment from Governor Alfred Landon as superintendent of the State Industrial Department at Western University. During this time, he also used political clout to help get the funding to build a new Vernon School on the same site as the old Vernon School, which had become overcrowded and dilapidated.

Soon, a new school was under construction by members of the Works Progress Administration to serve the area’s African-American children for grades 1st-8th. While the new building was in the works, students attended classes in the basement of the Methodist Church, which still stands at 3428 N. 29th Street.

The new Vernon School opened in 1936, with Professor William Franklin King serving as the first principal. He continued to serve that first year until he accepted another position elsewhere. The Vernon School was a haven of education for African-American students prior to school integration, which occurred in 1944.

In 1937, the Douglass Hospital moved to 3700 North 27th Street, on the campus of Western University.

In 1938, Reverend Vernon retired from Western University. He died six years later, on July 25, 1944.

After the United States entered World War II in 1941, the draft further diminished enrollment at Western University. The six women of the 1943 high school class were the final graduates of the college. After 78 years of providing a four-year education to African-American students, the school was officially closed in 1944 and was legally dissolved in 1948.

Douglass Hospital in Grant Hall Western University in Quindaro, Kansas.

In 1945, Douglass Hospital renovated the old Western University Grant Hall as a medical facility.

In 1949, an article in the Kansas City Times observed that the Steiner and Zehntner brewery was “virtually the only remaining structure” in Quindaro, stating, “all other buildings are lost from sight and are overgrown with trees and brush.”

Quindaro’s post office closed for good in March 1954.

The Vernon School closed in 1971 after Urban Renewal wiped out most of the homes of children in the area. Today, the Vernon School is on the National Register of Historic Places and is home to the Quindaro Underground Railroad Museum. Here, visitors can see displays, artifacts, and maps of the cooperative efforts of the Native Americans, whites, and free blacks who worked together on the Underground Railroad. The museum also displays information regarding the discovery and exploration of the Quindaro Ruins.

Douglass Hospital occupied the former Western University site for more than 30 years before closing in 1978. Unfortunately, during those years, the hospital demolished the buildings associated with the university and replaced them with two new buildings designed as elderly housing or nursing homes. The closure of the hospital brought an end to more than 120 years of Quindaro’s existence.

Some of these “newer” hospital buildings still stand deteriorating today, but unfortunately, nothing but cornerstones of some early buildings still exist. Some buildings were lost to fire and others to demolition as sites were redeveloped. The last structures remaining were three faculty houses, which were demolished near the end of the 20th century.

The site of Western University and later the Douglass Hospital today, courtesy of Google Maps.

In the late 1980s, a company wanted to build a landfill in the area but encountered an obstacle under the Kansas Antiquities Commission Act, which required that an archeological investigation be conducted. Over a two-year period, a cistern, three wells, and the foundations of 22 residential and commercial buildings were discovered in the 1850s town.

Public outcry over the proposed landfill caused the company to withdraw its interest in the project, and the excavated artifacts were given over to the Kansas Historical Society.

A view from the Quindaro overlook of the old townsite showing Kanzas Avenue and the Missouri River by Kathy Alexander.

The 70.5-acre Quindaro Townsite is now a National Commemorative Site and an archaeological district. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 22, 2002.

In present-day terms, Quindaro was bounded on the north by the Missouri River, on the east by 18th Street, on the south by Brown Avenue, and on the west by 42nd Street. During Quindaro’s boom days, the Missouri River was west of the present location. Kanzas Avenue is now 27th Street. The ruins of Quindaro now belong to the African Methodist Episcopal Church and the City of Kansas City, Kansas. There is a stone platform overlooking the ruins.

Today, Old Quindaro is a living neighborhood that is part of Kansas City, Kansas.

The statue of John Brown, erected in 1911, still stands at 27th and Sewell with a marker that explains the history of Western University. Across the street is the Quindaro Underground Railroad Museum in the old Vernon School. To the north, at 3700 N. 27th Street, are the remaining deteriorating buildings of the old nursing home, and at the end of the street, at a dead-end, is the Quindaro Ruins Overlook. A dirt path extends from the overlook stairs, following the alignment of Kansas Avenue. This path veers west, leading to the cemetery at the northwest before continuing south along what some former residents referred to as “Happy Hollow Road,” now recognized as 31st Street Terrace.

Visitors may also visit the two Quindaro Cemeteries. One is located at 38th and Parallel and has become a part of the Mount Hope Cemetery. The second Quindaro Cemetery is located at 34th and Sewell Avenue.

Old Quindaro Museum in Kansas City, Kansas, by Kathy Alexander.

The Old Quindaro Museum at 3432 N 29th Street, which has long preserved the overall importance of the African-American Community of Quindaro, appears to be closed as of this writing.

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of Kansas, updated October 2023.

Also See:

African American History

Kansas City, Kansas

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Photo

Today is National Native American Heritage Day. Listen to Series 5: People of the Island. Homegrown KC is a podcast dedicated to exploring Kansas City's fascinating history and sharing stories from its rich past. It is available wherever podcasts can be found including but not limited to Audible, Amazon Music, Google Music, Pandora, Spotify, and Apple Podcasts. To become a patron supporter subscribe to redcircle.com/homegrownkc or patreon.com/homegrownkc. Subscribers get access to exclusive bonus episodes featuring other local historians, archivits, and museum professionals. They also receive an item from the merchandise store valued at 5$ or less, and a shout out on every episode and social media post. Or you can give a one time donation at redcircle.com/homegrownkc or Ko-fi.com/homegrownkc. All donors will receive a shout out. And 1% of all Ko-Fi donations will go to fight climate change. To see what merchandise is available, go to zazzle.com/store/homegrown_kc_store. For more information on each topic, visit my website: homegrownkc.wordpress.com. and sign up for my monthly newsletter on my website as well. Like, follow, and subscribe to the show on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Pinterest, Tumblr, and Youtube. Rate and Review the show where you listen, especially on Apple Podcasts. Thank you Bjorn, Joan, and Jeanna for your continued support. Thanks also goes to Sarah McCombs for the creation of my logo; the Dear Misses for use of their song Kansas City, as the intro and outer music of the show; to local libraries; and to all my wonderful listeners. Cheers! #homegrownkc #communityhistory #stateandlocalhistory #kchistory #kcproud #historypodcast #podcastersofinstagram #indigenoushistory #nativehistory #quindaro #wyandotte #wyandotnation #wyandottenation #wyandotnationofkansas https://www.instagram.com/p/ClYz6HNrMiQ/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#homegrownkc#communityhistory#stateandlocalhistory#kchistory#kcproud#historypodcast#podcastersofinstagram#indigenoushistory#nativehistory#quindaro#wyandotte#wyandotnation#wyandottenation#wyandotnationofkansas

0 notes

Photo

Bath in 24kt Gold #gold #24kgold #soap#cuticlecare #selflove#cleanlinessisnexttogodliness #pennycandy #pennycandyllc #sweetsfortheskin #followtheyellowbrickroad #brickcity #kck #wyandotte #kckgirl #quindaro #gold #goldbricks #luxurylifestyle #candywrapper https://www.instagram.com/p/CEVMJtCn1_i/?igshid=1a138r34fwpfm

#gold#24kgold#soap#cuticlecare#selflove#cleanlinessisnexttogodliness#pennycandy#pennycandyllc#sweetsfortheskin#followtheyellowbrickroad#brickcity#kck#wyandotte#kckgirl#quindaro#goldbricks#luxurylifestyle#candywrapper

0 notes

Text

Quindaro Overlook

Dedicated in 2008, the Quindaro Overlook presents a vantage point to survey the ruins of Quindaro, a Wyandot community and Underground Railroad landmark. Interpretive signs at the overlook tell the story of Old Quidaro, a briefly thriving river port town founded to provide safe harbor for free-soil migrants after pro-slavery residents blockaded all the other ports on the Missouri River. Using land purchased from local Wyandots, the town grew quickly along the steep hillside with a mixed population of Native, white, and black Americans.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The ruins of Quindaro, a town that was once a stop on Harriet Tubman’s Underground Railroad. A weak attempt was made by conservationists to preserve the ruins, but the funds ran dry, and it now sits buried in the woods, untouched by both vandals and historians alike.

172 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I got to take a longer look at the Quindaro Overlook and Ruins today. It's not as scary when you bring a friend along and go in the middle of the afternoon as opposed to sun down. #quindaro #kansascitykansas #Kansas #kck #localhistory #kansashistory #blackhistory (at Quindaro Ruins)

0 notes

Link

She rose to fame as an endlessly inventive pop android. Now, she's finally revealing the real person waiting inside

Janelle Monáe is crying in her spacesuit. It's early April in Atlanta, and she's in one of the basement studios of her Wondaland Records headquarters, surrounded by computer monitors and TV screens, one of them running a screensaver that displays images of her heroes: Prince, Martin Luther King Jr., Pam Grier, Tina Turner, Lupita Nyong'o, David Bowie. She's about to reveal, for the first time, something the world has long guessed, something her closest friends and family already know, something she's long been loath to say in public. As she sings on a song from her new album, Dirty Computer,"Let the rumors be true." Janelle Monáe is not, she finally admits, the immaculate android, the "alien from outer space/The cybergirl without a face" she's claimed to be over a decade's worth of albums, videos, concerts and even interviews – she is, instead, a flawed, messy, flesh-and-blood 32-year-old human being.

And she has another rumor to confirm. "Being a queer black woman in America," she says, taking a breath as she comes out, "someone who has been in relationships with both men and women – I consider myself to be a free-ass motherfucker." She initially identified as bisexual, she clarifies, "but then later I read about pansexuality and was like, ‘Oh, these are things that I identify with too.' I'm open to learning more about who I am."

It's a lovely spacesuit she's wearing, a form-fitting white NASA artifact complete with a commander patch on one arm and an American flag on the other. She's put it on for no reason at all – there are no cameras in sight – as she lounges around Wondaland. The outfit is a remnant, perhaps, of the android persona, known as Cindi Mayweather, that she fed us all these years: a messianic, revolutionary robot who fell in love with a human and vowed to free the rest of the androids.

Early in her career, Monáe was insecure about living up to impossible showbiz ideals; the persona, the androgynous outfits, the inflexible commitment to the storyline both on- and offstage, served in part as protective armor. "It had to do with the fear of being judged," she says. "All I saw was that I was supposed to look a certain way coming into this industry, and I felt like I [didn't] look like a stereotypical black female artist."

She is also a perfectionist, a tendency that's helped her career and hindered her emotional life; portraying a flawless automaton was also a bit of wish fulfillment. It's one of the many reasons she thought she had a "computer virus" that needed cleaning, which led her to years of therapy, starting before the 2010 release of her debut, The ArchAndroid. "I felt misunderstood," she says. "I was like, ‘Before I self-destruct, before I become a confused person in front of the world, let me seek some help.' I was afraid for anybody to see me not at the top of my game. That obsession was too much for me."

So she overcompensated, as she puts it, leaving fans to puzzle over the sight and sound of a dark-skinned, androgynously dressed black woman creating Afro-futuristic fantasias as trippy as the Parliament-Funkadelic soundscapes she grew up hearing. She became a pop anomaly, a sometimes incongruous interloper in the universes of her earliest supporters, Big Boi and Puff Daddy, the latter having signed her to a partnership with Bad Boy Records in 2008. The ArchAndroidwas a buzzy introduction, and 2013's Electric Lady – certainly the first progged-out concept album in the history of Bad Boy – established her as one of the 21st century's most inventive voices. Years before Frank Ocean, Solange, Beyoncé and SZA pushed arty, alternative R&B to the mainstream, Monáe was already there, bridging the gap between neo-soul and all that was to come, unafraid to fuse rock, funk, hip-hop (when she feels like it, as on her recent single "Django Jane," she's a top-flight rapper), R&B, electronica and campy, drama-kid theatricality.

She always ducked questions about her sexuality ("I only date androids" was a stock response) but embedded the real answers in her music. "If you listen to my albums, it's there," she says. She cites "Mushrooms & Roses" and "Q.U.E.E.N.," two songs that reference a character named Mary as an object of affection. In the 45-minute film accompanying Dirty Computer, "Mary Apple" is the name given to female "dirty computers" taken captive and stripped of their real names, one of whom is played by Tessa Thompson. (The actress has been rumored to be Monáe's girlfriend, though Monáe won't discuss her dating life.) The original title of "Q.U.E.E.N.," she notes, was "Q.U.E.E.R.," and you can still hear the word on the track's background harmonies.

Monáe is the CEO of her own label, a CoverGirl model and a movie star, appearing in the Oscar-winning Moonlight and the Oscar-nominated Hidden Figures, two hits led by black casts. In both films, she tackles black American stories that don't typically get the big-screen treatment. "Our stories are being erased, basically," she says of her attachment to those scripts, which made her "want to tell my story." Monáe does worry that the human behind her masks may not be enough. She has asked aloud, including in therapy, "What if people don't think I'm as interesting as Cindi Mayweather?" She'll miss the freedom of being the android. "I created her, so I got to make her be whatever I wanted her to be. I didn't have to talk about the Janelle Monáe who was in therapy. It's Cindi Mayweather. She is who I aspire to be." On Dirty Computer, the only hints of sci-fi are in the title and the storyline of the accompanying film. The lyrics are flesh-and-blood confessions of both physical and emotional insecurity, punctuated with sexual liberation. They're the unfiltered desires of an overthinker letting herself speak without pause, for once. And she wants to help listeners gain the courage to be dirty computers too. "I want young girls, young boys, nonbinary, gay, straight, queer people who are having a hard time dealing with their sexuality, dealing with feeling ostracized or bullied for just being their unique selves, to know that I see you," she says in a tone befitting the commander patch on her arm. "This album is for you. Be proud."

Monáe grew up in a massive, devoutly Baptist family in Kansas City, Kansas, or as she likes to put it, "I got 50 first cousins!" Not all of them know details of her romantic life, but they have almost certainly seen her wear sheer pants and share a lollipop with Thompson in the "Make Me Feel" video. "I literally do not have time," she says, laughing, "to hold a town-hall meeting with my big-ass family and be like, ‘Hey, news flash!' " She worries that when we visit Kansas City tomorrow, they'll bring it up: "There are people in my life that love me and they have questions, and I guess when I get there, I'll have to answer those questions."

Over the years, she's heard some members of her family, mostly distant ones, say certain upsetting things. "A lot of this album," she says, "is a reaction to the sting of what it means to hear people in my family say, ‘All gay people are going to hell.' "

She began questioning the Bible and her family's Baptist faith early on. Now, she says, "I serve the God of love" – love, she's determined, is the common factor among all religions, an idea Stevie Wonder expanded on in a Dirty Computer interlude.

When we arrive in the flat, industrial Kansas side of Kansas City, her family doesn't actually have any questions – or anything unkind to say, for that matter. There's just a whole lot of love for their homegrown superstar.

Janelle Monáe Robinson was born here on December 1st, 1985, to a mom who worked as a janitor and a dad who was in the middle of a 21-year battle with crack addiction. Her parents separated when Monáe was less than a year old, and her mother later married the father of Janelle's younger sister, Kimmy.

Monáe's loving warnings about the sheer size of her family ring true as soon as we step into her old neighborhood. On one street, her maternal grandmother owned several homes in a row that housed cousins, aunts, uncles and Monáe herself. A few minutes away is her paternal great-grandmother's pastel-coated house. Monáe spent a significant portion of her time there – it was her main connection to her dad and his family as he went in and out of prison; their relationship was rocky until he got sober 13 years ago. Another short car ride away is her maternal Aunt Glo's home, where we meet her mom. "She's my favorite slice of pie," her Auntie Fats says, referring to Monáe's familial nickname of "pun'kin."

Monáe was raised in a working-class community called Quindaro. It started as a settlement established by Native Americans and abolitionists just prior to the Civil War, and became a refuge for black Americans escaping slavery via the Underground Railroad. A few weeks before our visit, vandals painted swastikas and "Hail Satan" on a statue of abolitionist John Brown in the neighborhood. It's since been repainted. "I know nobody in this neighborhood did that," her great-grandmother says, shaking her head. "Outsiders."

On the Missouri side of the bridge, Kansas City is predominately white, but Monáe's community is overwhelmingly black. "I would read about where I was from," she says, "and understand who's really disadvantaged coming from these environments. It sucks. It's like that for brown folks." It's hard to miss her family's religiosity – they hardly get a sentence out without a mention of God's blessings. At 91, Monáe's great-grandma still monitors the halls at the local vacation Bible school with a switch in hand. During our visit, she sits behind a piano to lead a gospel singalong. Monáe, beside an aunt and a cousin, joins in, belting "Call Him Up and Tell Him What You Want" and "Savior, Do Not Pass Me By."

Monáe is never more relaxed during our time together than when she's in Kansas City. Her Midwestern drawl comes back as she screams and sings while running into the arms of her cousins, aunts and uncles, many of whom she gets to see only during the holidays or tour stops nearby. At one point, she curls up into her mom's lap while they look at a homemade poster full of sepia-toned childhood pics. "She was a delightful baby," Auntie Fats recalls.

Monáe's family members all share different versions of the same story: She was born to be a star, and she made that clear as soon as she gained motor skills. There was that time she got escorted out of church for insisting on singing Michael Jackson's "Beat It" in the middle of the service. There were the talent shows for Juneteenth where she covered "The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill" three years in a row and won each time. She was the star of the school musicals, except for The Wiz her senior year, when she lost the role of Dorothy because she had to leave the audition early to pick up her mom at work. She's still a bit miffed about not getting that part.

Monáe soon passed a bigger audition, for the American Musical and Dramatic Academy, and headed to New York. She studied musical theater and shared a small apartment with a cousin where she didn't even have a bed to herself. When she wasn't in class, she was working.

Meanwhile, an old friend was having the college experience Monáe desired, in Atlanta, so she relocated. The rest is well-trod history in the myth-building of Monáe: She was an Afro'd neo-soul singer strumming her guitar on college quads and working at Office Depot. She was fired from that job for using one of the company's computers to respond to a fan's e-mail, an incident that inspired the song "Lettin' Go."

That song caught the attention of Big Boi, who put her on Outkast's Idlewild and helped connect her with Sean Combs. "I'm-a be honest with you," her dad says, recalling an invite to one of Monáe's shows in Atlanta, where Combs was supposed to be in the house. "I was like, ‘Yeah, right.' I didn't think Puff Daddy was coming."

Skepticism aside, Michael Robinson was proud of the invite. He'd recently gotten sober, and the two were repairing their relationship. He spent much of Janelle's childhood hearing about her immense talents from the more-present members of their family. He was honored that they had come far enough for Monáe to want him to be there for such an important concert. But he still didn't believe Puffy would be there.

"I go down there with my two cousins, and she says, ‘Dad, everyone's gonna know you're not from here. Your jeans are creased.' " Fashion faux pas aside – he insists he hasn't creased his jeans since – Robinson was in for a pleasant surprise when one of his cousins spotted Combs and Big Boi in the back. It was the beginning of his daughter's new life, and he was just in time to be along for the journey. "I remember thinking, ‘This is what the big time is like,' " he muses. "They had all the cameras, all the lights. It was all about Janelle."

Wondaland Arts Society's headquarters feels like a utopian synthesis of Monáe's past lives in Kansas City and Manhattan. It sits inconspicuously in the midst of suburban Atlanta and looks like every other neighborhood home, with its two floors and brick exterior. Inside is much more ostentatious, with vintage clocks wallpapering the foyer, pristine white couches in the communal living spaces, and books and records everywhere.

It mimics the close-knit, constant accessibility of her childhood in Kansas City, with all its artists popping in and out of the space throughout each day to record new music, rehearse for shows and present the final product to the rest of the collective. At one point, the singer-rapper Jidenna shows up, having recently returned from a trip to Africa – everyone immediately starts teasing him about his newly buff physique.

Simultaneously, Chuck Lightning, seemingly the more extroverted half of two-man funk act Deep Cotton, who make their own music as well as work with Monáe, grabs a bowl of quinoa from the kitchen as Monáe doles out decisions on which version of the "Pynk" video will be released (they settle on the one without the spoken-word love poem that appears within the song in the film).

Monáe recorded most of Dirty Computer here, in a small studio with Havana-inspired decor. Guests and collaborators ranged from Grimes to Brian Wilson, who added harmonies to the title track. The album's liner notes cite Bible verses and a recent Quincy Jones interview alongside Monica Sjöö's The Great Cosmic Mother and Ryan Coogler's Black Panther.

But she was particularly close to one inspiration. Monáe was good friends with Prince, who personally blessed the album's glossy camp tone and synthed-out hooks. "When Prince heard this particular direction, he was like, ‘That's what y'all need to be doing,' " Lightning says. "He picked out that sound as what was resonating with him." Prince gave highly specific music and equipment recommendations from the era they were drawing on, including Gary Numan, whom he loved. "The most powerful thing he could do was give us the brushes to paint with," Lightning says.

Rumors spread that Prince co-wrote the single "Make Me Feel," which features a "Kiss"-like guitar riff. "Prince did not write that song," says Monáe, who sorely missed his advice during the production process. "It was very difficult writing this album without him." Prince was the first person to get a physical copy of The ArchAndroid – she presented the CD to him with a flower and the titles written out by hand. "As we were writing songs, I was like, ‘What would Prince think?' And I could not call him. It's a difficult thing to lose your mentor in the middle of a journey they had been a part of."

Stevie Wonder was another early fan of Monáe, and a conversation between them – Wonder insisted she record it – appears as an interlude on Dirty Computer. At one point, years ago, her budding friendships with both legends collided: She had to choose between playing with Prince at Madison Square Garden or with Wonder in Los Angeles. Prince encouraged her to pick Stevie.

On election night in 2016, Monáe found herself experiencing an unfamiliar emotion. "For the first time," she says, "I felt scared." Overnight, she went from living in a country whose president loved her music and had her perform on the White House lawn to one where it felt like her right to exist was threatened. "I felt like if I wake up tomorrow," she says, "are people going to feel they have the right to just, like, kill me now?"

Monáe had already been a committed activist. In 2015, with members of Wondaland, she created "Hell You Talmbout," which demands we say the names of black Americans who have been victims of racial violence and police brutality. Before #MeToo and Time's Up, Monáe created an organization, Fem the Future, which stemmed from her frustrations about opportunities for women in the music industry. She was called on to perform at the 2017 Women's March and to speak about Time's Up while introducing Kesha at the Grammys. "We come in peace, but we mean business," she told the cheering crowd.

That sums up Monáe's mindset in the Trump era. She hopes not to destroy the oppressors but to change their minds. "The conversations might not happen with people in the position of power," she says, "but they can happen through a movie, they can happen through a song, they can happen through an album, they can happen through a speech on TV. Most of them will probably turn off their TVs, but . . ."

She's in a New York hotel now, two weeks before the album's release. "There's some anxiety there, but I feel brave," she says, teetering between her typical sternness and a bit of vulnerable shakiness. No tears will be shed today. "My musical heroes did not make the sacrifices they did for me to live in fear." Her activism isn't the focus of Dirty Computer, but it's there, hovering above every note. She ended band rehearsal in Atlanta by asking the musicians to reflect on how American this album is. Monáe's America is the one on the fringes; it accepts the outsiders and the computers with viruses, like the ones she thought she had.

She understands the significance of now making her personal life a bigger, louder part of her art. She cites the conversation around one of her films as an example of how she might use her own story to engage with more-conservative listeners. "When I did Hidden Figures, there were some Republican white men tweeting about it and how they just felt bad. You could feel through their tweets that they were just like, ‘These black women did help us get to space. How could we treat them like that?' "

Meanwhile, she's again anticipating questions from her family back in Kansas. She seems more worried about them than what anyone else has to say. Still, Dirty Computer is meant to be a celebration, and if she loses a few people along the way, Monáe seems OK with that risk.

"Through my experiences, I hope people are seen and heard," she says, sitting at a hotel-room desk, dressed up from a day of promo in a puffy black-and-red jacket, matching red pants and terry-cloth hotel slippers. "I may make some mistakes. I may have to learn on the go, but I'm open to this journey." She sighs, voice confident and stare unfaltering. "I need to go through this. We need to go through this. Together. I'm going to make you empathize with dirty computers all around the world."

https://www.rollingstone.com/music/features/cover-story-janelle-monae-prince-new-lp-her-sexuality-w519523

#long reads#janelle monae#janellemonae#wondaland#wondaland records#rolling stones#rolling stone magazine#cover#coverstory

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

I've moved on to focusing on Wyandotte (Quindaro's neighbors, also built on reserve lands) and found not only an attempted murder of a relative of that councilman whose murder had me so intrigued before, but also a revenge killing of the attempted murderer-- also the ferry has been stolen TWICE in the space of 2 years?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

One step closer: Quindaro Townsite inches toward National Historic Landmark designation

0 notes

Photo

Preservando las #Ruinas del pueblo de #Quindaro www.quindaroruinsprojectfoundationkck.org

0 notes

Text

Saturday, February 11, 2023 Canadian TV Listings (Times Eastern)

WHERE CAN I FIND THOSE PREMIERES?: THE GIRL WHO ESCAPED: THE KARA ROBINSON STORY (Lifetime Canada) 8:00pm A PARIS PROPOSAL (W Network) 8:00pm MARC MARON: FROM BLEAK TO DARK (HBO Canada) 10:00pm

WHAT IS NOT PREMIERING IN CANADA TONIGHT: THE PERFECT 10 (Fox Feed) MASTERS OF ILLUSION (CW Feed)

NEW TO AMAZON PRIME CANADA/CBC GEM/CRAVE TV/DISNEY + STAR/NETFLIX CANADA:

AMAZON PRIME CANADA CHUPKE CHUPKE

CRAVE TV MARC MARON: FROM BLEAK TO DARK

NHL HOCKEY (SNPacific) 12:00pm: Canucks vs. Red Wings (SN1/SNEast/SNOntario) 12:30pm: Flames vs. Sabres (SNWest/TSN5) 12:30pm: Oilers vs. Senators (TSN2) 12:30pm: Islanders vs. Habs (SN) 3:30pm: Capitals vs. Bruins (CBC/SN/City) 7:00pm: Blue Jackets vs. Leafs (CBC/SN) 10:00pm: Chicago vs. Jets

NBA BASKETBALL (TSN4) 6:00pm: 76ers vs. Nets (SN Now) 8:00pm: Bulls vs. Cavaliers (TSN/TSN4) 8:30pm: Lakers vs. Warriors

W5 (CTV) 7:00pm: Washed Away; The Tallest Teen on Earth: How fast Canada's east coast is disappearing into the ocean and how it can be stopped; the world's tallest teen is a quiet Canadian, whose challenge is to find his way in sports and life.

UNDERGROUND RAILROAD: THE SECRET HISTORY (CTV2) 7:00pm: Archaeologists unearth the lost community of Quindaro, Kan., a long-forgotten abolitionist town that shielded Freedom Seekers from bounty hunters, and in Illinois, experts use high-tech tools to explore a secret underground tunnel.

AUNTIE JILLIAN (CTV) 8:00pm (SEASON PREMIERE): Determined to keep her family active, Jillian sets up a day of baseball training with her brother and former pro-ball player, Nigel Wilson; Jillian invites a medium to the house for a reading, despite Warren's fear and concerns.

THE WINTER PALACE (Super Channel House & Home) 8:00pm: A novelist with a severe case of writer's block is given the chance to finish her book at an empty winter chateau.

DOWNTON ABBEY: A NEW ERA (Crave) 9:00pm: The Crawley family goes on a grand journey to the South of France to uncover the mystery of the dowager countess's newly inherited villa.

MACK & RITA (Starz Canada) 9:00pm: A 30-year-old writer spends a wild weekend in Palm Springs, Calif., and wakes up to find she's magically transformed into her 70-year-old self.

KICKING BLOOD (Super Channel Fuse) 9:00pm: After falling for a recovering alcoholic, a modern-day vampire sets her mind and heart on quitting blood and becoming human again.

#cdntv#cancon#canadian tv#canadian tv listings#W5#underground railroad: the secret history#auntie jillian#nhl hockey#nba basketball

1 note

·

View note

Photo

November is Native American Heritage Month in the USA. Listen to my People of the Island Series, including my conversation with 2nd Chief Louisa Libby, to learn about the history of the Wyandottes and the Wyandot Nation of Kansas. Homegrown KC is a podcast dedicated to exploring Kansas City's fascinating history and sharing stories from its rich past. It is available wherever podcasts can be found including but not limited to Audible, Amazon Music, Google Music, Pandora, Spotify, and Apple Podcasts. To become a patron supporter subscribe to redcircle.com/homegrownkc or patreon.com/homegrownkc. Subscribers get access to exclusive bonus episodes featuring other local historians, archivits, and museum professionals. They also receive an item from the merchandise store valued at 5$ or less, and a shout out on every episode and social media post. Or you can give a one time donation at redcircle.com/homegrownkc or Ko-fi.com/homegrownkc. All donors will receive a shout out. And 1% of all Ko-Fi donations will go to fight climate change. To see what merchandise is available, go to zazzle.com/store/homegrown_kc_store. For more information on each topic, visit my website: homegrownkc.wordpress.com. and sign up for my monthly newsletter on my website as well. Like, follow, and subscribe to the show on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Pinterest, Tumblr, and Youtube. Rate and Review the show where you listen, especially on Apple Podcasts. Thank you Bjorn, Joan, and Jeanna for your continued support. Thanks also goes to Sarah McCombs for the creation of my logo; the Dear Misses for use of their song Kansas City, as the intro and outer music of the show; to local libraries; and to all my wonderful listeners. Cheers! #homegrownkc #communityhistory #stateandlocalhistory #kchistory #kcproud #historypodcast #podcastersofinstagram #wyandotte #wyandotnation #wyandottenationalburialground #wyandotnationofkansas #nativehistory #indigenoushistory #historiccemetery #quindaro #nativeamericanhistory #nativeamericanheritagemonth https://www.instagram.com/p/Cka53V7Orbd/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#homegrownkc#communityhistory#stateandlocalhistory#kchistory#kcproud#historypodcast#podcastersofinstagram#wyandotte#wyandotnation#wyandottenationalburialground#wyandotnationofkansas#nativehistory#indigenoushistory#historiccemetery#quindaro#nativeamericanhistory#nativeamericanheritagemonth

0 notes

Text

D+6

First I must apologize for the extreme hiatus, especially after such a tragic cliffhanger. The road was rough and full of spontaneity, and my downtime was more happily spent gaming than updating and organizing these memories. Regardless, the adventure progressed without major incident from that point, aside from the looming lack of funding. The day in Kansas City was spent enjoying some unique museums and ended deep under the Earth, in a place few have ever seen.

The National WWI Museum is a gem in downtown KC

I wandered the exhibits and antique weaponry, amazed at the vast collection of history of a conflict that is often overshadowed by the following war. The museum contained case after case of guns, tools, medals, and documents telling the story of the Great War.

A battle damaged French Renault FT, now over 100 years old

There was also a large collection of trench art, and an immersive display of a trench battlefield. The walls were lines with propaganda posters and captured standards. I spent hours browsing, making sure I saw everything on display. There was even a signed piece of hard tack dated 4-16-17. Across the lawn from the WWI Museum is a Federal Reserve Bank, which contains a small money museum. While there wasn’t much to see, they did have on loan an impressive collection of every coin issued under the US Government, as well as rare bills and a history of Federal Reserve operations.

The amount of $100 bills that a federal bank cart can hold.

The highlight of this museum is the currency processing area. Each day the bank processes millions of dollars into storage or for destruction. Visitors can walk right up to a processing room and view workers counting and bagging huge sums of money, though no photography is allowed. When carts are loaded with a specified denomination, automated robots wheel them past a thick vault door into the massive money reserve, where more robots can lift and store them into seemingly endless racks. Standing so close to such an insane amount of cash is a surreal feeling. The trip continued with a stop at Kaw Point, the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri rivers. Formerly an industrial site, the grounds were cleaned up and converted into a park by dedicated volunteers, though there doesn’t seem to be funding or support to maintain them to a nice standard. I first visited this site in 2015, as a stopping point along the way to Standing Rock. The park is a monument and memorial to Lewis and Clark and the native peoples they encountered on their legendary journey.

The Lewis and Clark silhouette, covered in chalk, pointing towards the city

The next stop was a short one, at an overlook to the remains of Quindaro, a former town on the underground railroad. I don’t know the exact location of any ruins, but I couldn’t see anything from the overlook, and wasn’t up to climbing down the hill to find any. Near the site stands a statue of John Brown, erected by the “grateful people” of a now defunct HBCU, Western University. After this I checked out the ruins of Kansas city’s Schlitterbahn. The site had been heavily modified due to reconstruction, and was difficult to traverse. The park’s lifespan was just 9 years. In 2014, they opened the poorly named Verrückt, a 14 story slide with a hill that plunged riders up to 65mph. Due to poor safety features, the slide could cause riders to go airborne on the hill, and impact the safety netting designed to keep anything from falling out of the slide. Just two years after the ride’s construction, the 10 year old son of a Kansas state legislator was decapitated while riding. The park was unable to survive the financial impact and increased auditing of its attractions. I had the idea of possibly mountain biking in the abandoned waterways, but it would have been ridiculous to attempt in the dark.

An aerial view of the park before it’s demolition. Currently, only the concrete features remain, but will probably be removed for further development.

The final stop of the day was the entire inspiration for conducting this trip. Through a photographer friend, I learned of the existence of a vast underground storage cave. Many such caves exist around the country, and even within Kansas City, converting old limestone or other mines into cheap and climate stable storage. This cave was one of the oldest operating, and as such did not have robust fire suppression installed, as it was built before such codes existed. In 1991, disaster struck when a fire ignited in a food storage area forced an emergency evacuation. Firefighters responded, but lacked oxygen tanks with enough capacity to get through the mile of thick smoke pouring out of the cave tunnels. Still they fought for several days attempting to reach and extinguish the blaze.

Newspaper excerpt from the time of the fire

A variety of methods were applied, but with no knowledge of the scale or exact source of the fire, plus the difficulties of getting the proper equipment a mile underground, the battle was utterly lost. The owners of the cave once bragged that it contained one pound of food for every person in America. At the time, it was estimated to have about 245 million pounds of dry and frozen goods. Officials decided to cut their losses and attempted to seal the cave in order to choke off the fire. It continued to burn for two months. After it finally died out, the company was able to resume some mining and begin salvage operations for the rest of the cave’s contents, an operation that lasted months. The former entrances to the cave were easy to find, though I did not know how many there were, or how far they were spread. Expecting flooded passages and muddy terrain, I donned my waders and equipment, I hiked down the overgrown gravel path and squeezed through the stuck gate, entering what used to be the administration and office area of the enormous Kansas City Underground.

The mouth of the cave entrance, hidden at the base of the cliff wall

The air was damp, chilly, and thick with dust. The muddy earth sucked at my boots as I waded through the water, trying to find a way deeper in. I attempted to take the right path, but nearly lost my balance trying to unstick my shoe in water up to my waist. I turned back and headed straight, climbing over piles of rockfall from the collapsed ceilings. Sometimes these collapses are intentional, to seal off passages, but others are a result of the slowly decaying nature of the artificial tunnels.