#Archbishop of Canterbury Lanfranc

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Kings and Churchmen

Kings and Churchmen and why Kings of England needed the support of the Church to hold on to power if they did not have support of nobility

Today, I will be writing and discussing the importance of churchmen who supported kingship during the mediaeval ages, stretching from the fall of the Roman Empire in 476 CE to the discovery of America by Europeans in 1492 CE by Christopher Columbus. For this article, I will be discussing the kingship focus Kings of England, why churchmen were an essential pillar of Kings and a force for support,…

View On WordPress

#Archbishop of Canterbury Lanfranc#Battle of Lincoln#Christopher Columbus#Church and State#Cnut the Great#Earl Robert of Gloucester#English History#King Stephen of England#Kings of England#Lanfranc#William the Conqueror

0 notes

Text

SAINT OF THE DAY (April 21)

On April 21, the Catholic Church honors Saint Anselm, the 11th and 12th-century Benedictine monk and archbishop best known for his writings on Christ's atonement and the existence of God.

In a general audience given on 23 September 2009, Pope Benedict XVI remembered St. Anselm as “a monk with an intense spiritual life, an excellent teacher of the young, a theologian with an extraordinary capacity for speculation, a wise man of governance and an intransigent defender of the Church's freedom.”

St. Anselm, the Pope said, stands out as “one of the eminent figures of the Middle Ages who was able to harmonize all these qualities, thanks to the profound mystical experience that always guided his thought and his action.”

Anselm was born in Aosta, part of the Piedmont region of present-day Italy, around 1033.

While his father provided little in the way of moral or religious influence, his mother was a notably devout woman and chose to send Anselm to a school run by the Benedictine order.

The boy felt a profound religious calling during these years, spurred in part by a dream in which he met and conversed with God.

His father, however, prevented him from becoming a monk at age 15. This disappointment was followed by a period of severe illness, as well as his mother's early death.

Unable to join the monks and tired of mistreatment by his father, Anselm left home and wandered throughout parts of France and Italy for three years.

His life regained its direction in Normandy, where he met the Benedictine prior Lanfranc of Pavia and became his disciple.

Lanfranc recognized his pupil's intellectual gifts and encouraged his vocation to religious life.

Accepted into the Order and ordained a priest at age 27, Anselm succeeded his teacher as prior in 1063 when Lanfranc was called to become abbot of another monastery.

Anselm became abbot of his own monastery in 1079.

During the previous decade, the Normans had conquered England, and they sought to bring monks from Normandy to influence the Church in the country.

Lanfranc became Archbishop of Canterbury and asked Anselm to come and assist him.

The period after Lanfranc's death, in the late 1080s, was a difficult time for the English Church.

As part of his general mistreatment of the Church, King William Rufus refused to allow the appointment of a new archbishop. Anselm had gone back to his monastery and did not want to return to England.

In 1092, however, he was persuaded to do so.

The following year, the king changed his mind and allowed Anselm to become Archbishop of Canterbury.

But the monk was extremely reluctant to accept the charge, which would involve him in further struggles with the English crown in subsequent years.

For a three-year period in the early 12th century, Anselm's insistence on the self-government of the Church – against the claims of the state to its administration and property – caused him to be exiled from England.

But he was successful in his struggle and returned to his archdiocese in 1106.

In his last years, Anselm worked to reform the Church and continued his theological investigations – following the motto of “faith seeking understanding.”

After his death in 1109, his influence on the subsequent course of theology led Pope Clement XI to name him a Doctor of the Church in 1720.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE DESCRIPTION OF SAINT ANSELM OF CANTERBURY The Father of Scholasticism and the Defender of the Immaculate Conception Feast Day: April 21

"For I do not seek to understand in order to believe, but I believe in order to understand. For I believe this: unless I believe, I will not understand."

The future archbishop of Canterbury was born Anselmo d'Aosta, circa 1033 in Aosta, Kingdom of Burgundy, Holy Roman Empire. His father Gundulph, was a Lombard noble, probably one of Adelaide's Arduinici uncles or cousins; his mother Ermenberga was almost certainly the granddaughter of Conrad the Peaceful, related both to the Anselmid bishops of Aosta and to the heirs of Henry II who had been passed over in favour of Conrad.

At the age of 27, he entered the Benedictine abbey of Bec, in Normandy, and three years later, he was elected as the abbot of Caen. Several monks murmured on account of his youth, but Anselm by his sympathy and patience won the allegiance of all. With regard to the training of the young, he had quite modern views.

To a neighboring abbot, who was lamenting the poor success of his educational method, he said: 'If you plant a tree in your garden and bound it on all sides, so that it can not spread out its branches, what kind of tree would it become? And that is how you treat your boys, cramping them with fears and blows, depriving them of the enjoyment of any freedom.'

Being an original thinker, Anselm was the greatest theologian of his age, and the father of Scholasticism. In the Monologion, he spoke of God as the highest being and investigated God's attributes; while in his Prologue, he gave the famous ontological proof of God's existence.

Anselm was called to succeed his countryman Lanfranc, as the archbishop of Canterbury. It was a time of great strife with the king over the Church's independence, and Anselm was exiled several times.

Amid the rejoicing of the people, Anselm returned to Canterbury in 1106, where he died a holy death on April 21st three years later in 1109. Anselm was proclaimed a Doctor of the Church by Pope Clement XI in 1720; he is known as the doctor magnificus ('Magnificent Doctor') or the doctor Marianus ('Marian doctor').

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 8.15 (before 1800)

636 – Arab–Byzantine wars: The Battle of Yarmouk between the Byzantine Empire and the Rashidun Caliphate begins. 717 – Arab–Byzantine wars: Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik begins the Second Arab Siege of Constantinople, which will last for nearly a year. 718 – Arab–Byzantine wars: Raising of the Second Arab Siege of Constantinople. 747 – Carloman, mayor of the palace of Austrasia, renounces his position as majordomo and retires to a monastery near Rome. His brother, Pepin the Short, becomes the sole ruler (de facto) of the Frankish Kingdom. 778 – The Battle of Roncevaux Pass takes place between the army of Charlemagne and a Basque army. 805 – Noble Erchana of Dahauua grants the Bavarian town of Dachau to the Diocese of Freising 927 – The Saracens conquer and destroy Taranto. 982 – Holy Roman Emperor Otto II is defeated by the Saracens in the Battle of Capo Colonna, in Calabria. 1018 – Byzantine general Eustathios Daphnomeles blinds and captures Ibatzes of Bulgaria by a ruse, thereby ending Bulgarian resistance against Emperor Basil II's conquest of Bulgaria. 1038 – King Stephen I, the first king of Hungary, dies; his nephew, Peter Orseolo, succeeds him. 1057 – King Macbeth is killed at the Battle of Lumphanan by the forces of Máel Coluim mac Donnchada. 1070 – The Pavian-born Benedictine Lanfranc is appointed as the new Archbishop of Canterbury in England. 1096 – Starting date of the First Crusade as set by Pope Urban II. 1185 – The cave city of Vardzia is consecrated by Queen Tamar of Georgia. 1224 – The Livonian Brothers of the Sword, a Catholic military order, occupy Tarbatu (today Tartu) as part of the Livonian Crusade. 1237 – Spanish Reconquista: The Battle of the Puig between the Moorish forces of Taifa of Valencia against the Kingdom of Aragon culminates in an Aragonese victory. 1248 – The foundation stone of Cologne Cathedral, built to house the relics of the Three Wise Men, is laid. (Construction is eventually completed in 1880.) 1261 – Michael VIII Palaiologos is crowned as the first Byzantine emperor in fifty-seven years. 1281 – Mongol invasion of Japan: The Mongolian fleet of Kublai Khan is destroyed by a "divine wind" for the second time in the Battle of Kōan. 1310 – The city of Rhodes surrenders to the forces of the Knights of St. John, completing their conquest of Rhodes. The knights establish their headquarters on the island and rename themselves the Knights of Rhodes. 1430 – Francesco Sforza, lord of Milan, conquers Lucca. 1461 – The Empire of Trebizond surrenders to the forces of Sultan Mehmed II. This is regarded by some historians as the real end of the Byzantine Empire. Emperor David is exiled and later murdered. 1483 – Pope Sixtus IV consecrates the Sistine Chapel. 1511 – Afonso de Albuquerque of Portugal conquers Malacca, the capital of the Malacca Sultanate. 1517 – Seven Portuguese armed vessels led by Fernão Pires de Andrade meet Chinese officials at the Pearl River estuary. 1519 – Panama City, Panama is founded. 1534 – Ignatius of Loyola and six classmates take initial vows, leading to the creation of the Society of Jesus in September 1540. 1537 – Asunción, Paraguay is founded. 1540 – Arequipa, Peru is founded. 1549 – Jesuit priest Francis Xavier comes ashore at Kagoshima (Traditional Japanese date: 22 July 1549). 1592 – Imjin War: At the Battle of Hansan Island, the Korean Navy, led by Yi Sun-sin, Yi Eok-gi, and Won Gyun, decisively defeats the Japanese Navy, led by Wakisaka Yasuharu. 1599 – Nine Years' War: Battle of Curlew Pass: Irish forces led by Hugh Roe O'Donnell successfully ambush English forces, led by Sir Conyers Clifford, sent to relieve Collooney Castle. 1695 – French forces end the bombardment of Brussels. 1760 – Seven Years' War: Battle of Liegnitz: Frederick the Great's victory over the Austrians under Ernst Gideon von Laudon.

0 notes

Text

If you put out a list of "Must-Read Medieval Historical Fiction Novels" and your list of only ten books includes Ken Follett, Philippa Gregory, and Bernard Cornwell, I am legally allowed to hang, draw, and quarter every person involved in putting together this farce.

Especially if Christopher Beuhlman, Umberto Eco, Sharon Kay Penman, Karen Maitland, Dorothy Dunnett, and even Tracy Chevalier and Sharan Newman (neither a literary genius, but capable of doing research; bar's very low) are nowhere to be found?

Also, what the fuck is this???

Please kill me now.

(Also, this is fucking stupid. What goddamn help is a fucking philosopher and perennial fuck-up [multiple accusations of heresy, excommunicated, slept with his student (who may have been no older than 15 at the time) and got her pregnant, and was fucking castrated for his nonsense] going to be in attempting to figure out 19 years after the fact whether William Rufus was accidentally or deliberately killed? Not to mention that involving Abelard in anything was usually a recipe for disaster... Why not move the story back 10 years and let the person trying to help this guy Hilary be Anselm of Bec??? He was Archbishop of Canterbury! Meaning he at least actually lived in England! PETER ABELARD NEVER STEPPED FOOT IN ENGLAND IN HIS GODDAMN LIFE.

...Lanfranc [Archbishop before Anselm and a very sarcastic dude] would have been even more fun, but he was sadly very dead by the time William Rufus was killed.)

(I would generally argue that calling a book set in 14th-century Vietnam or 15th century Persia "medieval" is, in the same way people call Jane Austen "Victorian" [Austen died two years before Queen Victoria was even born, and 20 years before Victoria became queen] or Nelson Mandela "African-American," ABSOLUTELY 1000% STUPID.)

(Also, can we talk about the fact that other things happened in the Middle Ages besides the Black Death and the Wars of the Roses??? Admittedly, the whole William Rufus thing above is a refreshing change of medieval pace. Just... again... why Abelard???)

(Abelard is in Sharan Newman's medieval books, but as a peripheral character because the protagonist was educated at the convent of Argenteuil, where Heloise was abbess.)

(Heloise is the student Abelard slept with. I think most people know that, but maybe not???

(Also, can we talk about the fact that Heloise's Wikipedia article says she influenced Abelard, rather than the other way around. Which is accurate, but still also fucking hilarious.)

(Abelard was such a whiny little asshole he called his autobiography "Historia Calamitatum," "the history of my calamities." Pete, my friend, every single one of your many, many calamities was YOUR FAULT.)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Eleanor experienced almost fifteen years of regular childbearing after marrying Henry Plantagenet. It was during her early years as queen, while she was bearing a child almost annually, that she was busiest acting as Henry’s regent in England. She would give Henry II nine children within thirteen years. If Eleanor of Aquitaine was a distant figure as mother to her children, so were other aristocratic mothers responsible for supervising complex households. As queen, she had even less time than most for child-rearing. Contact with her children would have been limited while they were growing up.

This was due to circumstances and social custom, not to a lack of maternal feeling, and it is not necessary to conclude that Eleanor was indifferent toward her young children nor that she made little “psychological investment” in them. There is no evidence to show that she and Henry failed to cherish their children, to provide for their care, to place their hopes in their futures, or to experience grief at their deaths. It seems fruitless from a distance of eight centuries to calculate Eleanor’s role in shaping her children’s adult psyches, when thinking on the topic is still influenced by nineteenth-century bourgeois models modified by twentieth-century Freudian psychology.

Yet one fact that stands out is the devotion to Eleanor demonstrated by her sons in their adult lives, and it testifies that their experience of her love was more powerful than their father’s fitful affection. Clearly, the queen had cemented solid ties of affection with them at some point, whether during their infancy or adolescence; and strong maternal feelings would prod her to furious activity after Henry II’s death, struggling to assist first Richard and then John in securing their thrones. As one writer observes, “It is difficult to believe that the devotion shown [Eleanor] by her adult sons and daughters did not grow out of childhood experience, experience that simply left no record in the account books and annals of the court.”

Possibly Henry’s difficulties with his sons were caused by their early and prolonged separations from their father. The fact that they were near-strangers to one another, in some years together only on great festive occasions, can explain in part the ease with which they took up arms against their father and against each other. Along with all medieval mothers, Eleanor was unaware of the significance of earliest childhood for shaping adult personality that modern psychology teaches. The early Fathers of the Church had not shown great interest in questions centering on family life, and twelfth-century churchmen with their ambivalent feelings about women provided mothers with little more direction in carrying out their maternal responsibilities.

Although concern for the care of children was growing in the twelfth century, encouraged in great part by Christian teaching, spiritual counselors offered mothers little counsel beyond advocating emulation of the Virgin Mary, the ideal mother. An exception to the dearth of literature on motherhood is a biography of Queen Margaret of Scotland, written in the first years of the twelfth century as a guide for her daughter Edith-Matilda, Henry I’s queen. It praises Margaret as a model mother, intimately involved with her children’s upbringing; yet the daughter who commissioned it hardly knew her mother, having been sent away at age six to be brought up at an English convent where her aunt was abbess.

Like many other great ladies living in the twelfth century, Eleanor had larger duties in politics and government that she regarded as equally important and perhaps greater than her responsibility for her children’s upbringing. In Henry and Eleanor’s household were retainers of many ranks, ranging from dependent relatives and high-ranking nobles to simple knights or domestic servants of peasant origin, any of whom could be charged with caring for the royal children. As a result, the royal children’s ties of affection would not have been focused uniquely on their parents, but diffused among household members of many ranks.

While differing from typical nuclear families today, the medieval English royal household, overflowing with servants and retainers, had much in common with other medieval aristocratic families. Like them and like European aristocrats or American plutocrats even in the twenty-first century who turn their children over to a series of servants, Eleanor and Henry did not think it unnatural to hand their children into the care of others in the royal household, or even to custodians far from court. Sons and daughters were often sent away at early ages, daughters to be reared in the households of their betrothed and sons given over to the care of others until early adolescence, when they were established in households of their own.

Yet these practices do not negate royal parents’ caring instincts or an awareness of the uniqueness of childhood that is innate in all societies. It is clear that Eleanor and Henry showed great concern for the upbringing of their offspring, choosing with care the personnel who were to supervise them even if their personal participation was limited. The rapidity with which Eleanor gave birth shows that she did not nurse her infant children, for it was uncommon for great ladies to nurse their own babies. As queen, her chief responsibility was ensuring continuity of the royal line by bearing children, not rearing them, and it was widely known that breast-feeding inhibited pregnancy.

Names of some of the royal children’s wet-nurses survive, and they indicate that they were selected from women of free, not servile, status, probably from wives of servants in the royal household. Alexander of Neckham, a scientific writer, Oxford master, and later abbot of Cirencester, proudly claimed that he and Richard Lionheart were “milk-brothers,” for his mother had been the prince’s wet-nurse. Eleanor felt so fondly toward Agatha, one of her children’s wet-nurses, that in 1198, three decades after her child-bearing years, she rewarded her service with a gift of land in Hertfordshire and a year later a more valuable gift, a Devonshire manor.

Agatha was a woman whose ambition Eleanor could admire, and such generous gifts would have made her former servant a woman of some means. Some time, probably before becoming John’s wet-nurse, Agatha entered into a long-term relationship with Godfrey de Lucy, son of the chief justiciar and himself a royal clerk who would win the bishopric of Winchester in 1189 despite being encumbered with a “wife.” Wet-nurses of Eleanor’s children must have resembled nannies in their relations with their charges, providing not only nourishment, but also affection and companionship and remaining with them long after weaning.

After John was brought to England during the great rebellion of 1173–74, the pipe roll records a grant of ten marks to “the nurse of the king’s son,” although he was at least seven years old then. The wet-nurses of Richard Lionheart and John earned their fond feeling, and their affection was returned. When Richard became king, he granted a pension to his nurse, Hodierna. After John’s death, his former nurse Agatha, by then a prosperous widow, remembered him and his son when making a gift of land to the nuns of Flamstead “for the soul of King Henry [III] son of King John.”

When Henry II’s sons were little more than infants, each of them was assigned a “master” or “preceptor” from among members of the royal household. He was assigned responsibility for the young boy, charged with spending on his needs and supervising the servants caring for him. He was not necessarily a cleric, and he did not give lessons; teachers—also called masters—could be recruited from the clerks and chaplains present in any great household. Choosing such a master was Henry’s duty, for noble fathers made major decisions about their sons’ upbringing, although he was likely to have discussed his selection with Eleanor.

A master named Mainard took charge of Young Henry in 1156 when the boy was only a year old, and he remained with him for at least three more years. The division of authority between this official and the child’s mother is unknown, but it must have meant that Eleanor was denied full responsibility for her son’s care, even in early childhood. Forced to share responsibility for her young sons with a male named by her husband, she nevertheless succeeded at some point in their youths in knitting the affective bonds normally binding sons to their mothers.

In 1159, when Young Henry was only four years old, his father placed him in the household of his chancellor Thomas Becket, where sons of nobles were “educated in gentlemanly upbringing and teaching.” There was precedent for Henry’s sending his heir away at such an early age: William the Conqueror had placed his second son, William Rufus, the designated heir to the English Crown, in Archbishop Lanfranc’s household. Henry II may already have been thinking of naming Becket his archbishop of Canterbury and having his eldest son crowned as king while still a boy.

When relations between Henry and Archbishop Becket began to cool, Henry, in October 1163, rebuked his newly installed primate by removing Young Henry from his custody. When the king left for his French territories the next month, he did not send the boy, then about eight years of age, back to Eleanor; instead, he continued to live apart from his mother’s household with a new master, William fitz John, a royal administrator. Young aristocrats were knighted as part of their initiation into manhood, and fathers would find them a mentor to join their household: an older, experienced knight who could prepare them for knighthood with training in the noble occupations of hunting, hawking, and warfare.

After Young Henry’s coronation in 1170, his father assigned such a mentor to the fifteen-year-old youth, the knight-errant William Marshal, much admired for chivalry, but an illiterate with little interest in administration. According to the History of William Marshal, he served as the sort of companion-guide who accompanied heroes of the romances, charged with the Young King’s instruction in courtesy and martial arts, preparing him to take up arms as a knight. Hunting sharpened warrior skills, and all of Henry and Eleanor’s sons shared their ancestors’ love for the chase.

Richard during his youth in Poitou would find pleasure in hunting in his mother’s ancestral forests in the Vendée. Roger of Howden wrote of Henry II’s sons, “They strove to outdo others in handling weapons. They realized that without practice the art of war did not come naturally when it was needed.” Sons of royalty needed to know more than skill in handling horses and weapons, and at twelfth-century princely courts, clerics were advocating a courtly ideal of conduct, challenging old-fashioned knights upholding the traditional warrior ethos of the knightly class.

The counts of Anjou had long prized learning in Latin letters, seen in the excellent schooling that Henry II’s father provided for him, and Eleanor too knew the value of learning. While less is known about Henry’s sons’ formal education than his own, it is certain that they acquired a sound grounding in Latin grammar, although no formal office of royal schoolmaster yet existed at the English court. A letter in the archbishop of Rouen’s name, addressed to the king when Young Henry was only ten years old, however, expresses a fear that the knightly side of the future king’s education was taking precedence over study of the liberal arts.

Perhaps the concern stemmed from Henry’s removal of his heir from Thomas Becket’s custody, and it hints at rivalry between the boy’s clerical and knightly tutors over the two groups’ diverging values. Richard Lionheart knew Latin well, although he is better known for his French verses. Gerald of Wales’s anecdote of the Lionheart’s correcting the Latin spoken by his archbishop of Canterbury gives evidence of his competence as a Latinist. John gained an interest in literature during his youth, and as king he built up a considerable library of classics and religious works. He deposited his books at Reading Abbey for safekeeping and sometimes wrote to the abbot requesting that certain volumes be sent to him.

Although great ladies had responsibility for their sons’ upbringing only until they reached their sixth or seventh year, aristocratic daughters could remain in their mother’s care until adolescence, unless they were betrothed as pre-adolescents and sent away to be brought up by their future in-laws. Like other queens throughout the Middle Ages, Eleanor saw her daughters affianced at early ages to foreign princes chosen for political considerations, and promptly sent far away to grow up at foreign courts. Personal contact by Eleanor with her daughters was difficult once they were sent off to their future husbands’ lands in Germany, Spain, and Sicily, and she had little prospect of seeing them again.

Yet contacts between royal daughters and their birth-parents were seldom entirely severed, and Eleanor doubtless corresponded with her daughters, although no copies of her letters survive. Royal parents maintained contact with daughters married to foreign princes, for their marriages had been arranged for the purpose of serving the family interest, creating or securing alliances. Matilda, Eleanor, and Joanne, married to princes who were conspicuous as cultural patrons, were almost certainly literate.

Late twelfth-century romances depict noble maidens learning their letters, and a renowned preacher, Adam of Perseigne (d.c. 1208), sent the countess of Chartres Latin texts that she could give to her daughters to read with the help of her chaplain or a learned nun. Although instruction in letters must have begun before Eleanor’s daughters left the English royal household, the major portion of their education would have taken place at the courts of their in-laws.”

- Ralph V. Turner, “Once More a Queen and Mother: England, 1154–1168.” in Eleanor of Aquitaine: Queen of France, Queen of England

#eleanor of aquitaine#eleanor of aquitaine: queen of france queen of england#children#history#high middle ages#medieval#wetnurses#education#ralph v. turner

84 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Imagine this: you are an 11th-century monk in Canterbury. You wake up only to discover you are not feeling very well. However, you don’t feel so awful that you think you need to go to the monastery’s infirmary but you are definitely too sick to function normally today. So what are you to do?

Luckily, we don’t have to wonder what your next steps should be! The Monastic Constitutions of Lanfranc, written by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Lanfranc (hence the name) tells you in detail what to do next.

The first thing a monk needed to do was announce his predicament in chapter. (Chapter was the monastery’s daily meeting.) After all, he couldn’t just not do his daily tasks without explaining why he was skipping them! So the monk would lay prostrate on the ground until the abbot/prior/whatever superior was running chapter that day gave him permission to stand up. Once he got to his feet, the monk would explain he was not feeling well and was unable to complete his duties for the day.

I’ve summarized the rest of Lanfranc’s instructions on my website. You can find it under the post titled "What Happened When An 11th Century Monk Was Only A Little Sick."

A monk sitting on the ground near a cliff and a tree

Genève, Bibliothèque de Genève, Comites Latentes 15, f. 2r

Source: https://www.e-codices.ch/en/list/one/bge/cl0015

1 note

·

View note

Text

Today, the Church remembers St. Wulfstan, Bishop.

Ora pro nobis.

Wulfstan was born about AD 1008 at Long Itchington in the English county of Warwickshire. His family lost their lands around the time King Cnut of England came to the throne. He was probably named after his uncle, Wulfstan II, Archbishop of York. Through his uncle's influence, he studied at monasteries in Evesham and Peterborough, before becoming a clerk at Worcester. During this time, his superiors, noting his reputation for dedication and chastity, urged him to join the priesthood. Wulfstan was ordained shortly thereafter, in AD 1038, and soon joined a monastery of Benedictines at Worcester.

Wulfstan served as treasurer and prior of Worcester. When Ealdred, the bishop of Worcester as well as the Archbishop of York, was required to relinquish Worcester by Pope Nicholas, Ealdred decided to have Wulfstan appointed to Worcester. In addition, Ealdred continued to hold a number of the manors of the diocese. Wulfstan was consecrated Bishop of Worcester on 8 September 1062, by Ealdred. It would have been more proper for him to have been consecrated by the Archbishop of Canterbury, whose province Worcester was in. Wulfstan had deliberately avoided consecration by the current archbishop of Canterbury, Stigand, since Stigand's own consecration had been uncanonical. Wulfstan still acknowledged that the see of Worcester was a suffragan of Canterbury. He made no profession of obedience to Ealdred, instead offering a profession of obedience to Stigand's successor Lanfranc.

Wulfstan was a confidant of Harold Godwinson, who helped secure the bishopric for him.

A social reformer, Wulfstan struggled to bridge the gap between the old and new regimes, and to alleviate the suffering of the poor. He was a strong opponent of the slave trade, and together with Lanfranc, was mainly responsible for ending the trade from Bristol.

After the Norman conquest of England, Wulfstan was the only English-born bishop to retain his diocese for any significant time after the Conquest (all others had been replaced or succeeded by Normans by 1075). William noted that pastoral care of his diocese was Wulfstan's principal interest.

In AD 1072 Wulfstan signed the Accord of Winchester. In AD 1075, Wulfstan and the Worcestershire fyrd militia countered the Revolt of the Earls, when various magnates attempted a rebellion against William the Conqueror.

Wulfstan founded the Great Malvern Priory, and undertook much large-scale rebuilding work, including Worcester Cathedral, Hereford Cathedral, Tewkesbury Abbey, and many other churches in the Worcester, Hereford and Gloucester areas. After the Norman Conquest, he claimed that the Oswaldslow, a "triple hundred" administered by the bishops of Worcester, was free of interference by the local sheriff. This right to exclude the sheriff was recorded in the Domesday Book in AD 1086. Wulfstan also administered the diocese of Lichfield when it was vacant between AD 1071 and 1072.

As bishop, he often assisted the archbishops of York with consecrations, as they had few suffragan bishops. In AD 1073 Wulfstan helped Thomas of Bayeux consecrate Radulf as Bishop of Orkney, and in AD 1081 helped consecrate William de St-Calais as Bishop of Durham.

Wulfstan was responsible for the compilation by Hemming of the second cartulary of Worcester. He was close friends with Robert Losinga, the Bishop of Hereford, who was well known as a mathematician and astronomer.

Wulfstan died 20 January 1095 after a protracted illness, the last surviving pre-Conquest bishop. After his death, an altar was dedicated to him in Great Malvern Priory, next to Cantilupe of Hereford and King Edward the Confessor.

At Easter of AD 1158, Henry II and his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine visited Worcester Cathedral and placed their crowns on the shrine of Wulfstan, vowing not to wear them again.

Wulfstan was canonized on AD 14 May 1203 by Pope Innocent III.

Almighty God, your only-begotten Son led captivity captive and gave gifts to your people: Multiply among us faithful pastors, who, like your holy bishop Wulfstan, will give courage to those who are oppressed and held in bondage; and bring us all, we pray, into the true freedom of your kingdom; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever.

Amen.

#father troy beecham#christianity#troy beecham episcopal#jesus#father troy beecham episcopal#saints#god#salvation#peace

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

“The life tells us that Margaret was literate and well-read. She herself spoke English as her native language, with her husband Malcolm acting as translator into his native Gaelic at court. However, she was likely also able to read in Latin, and possibly write in Latin too. It is known that she was in correspondence with Archbishop Lanfranc of Canterbury, though only his letters to her survive. Turgot describes how as her chaplain he went to great trouble to obtain the books she requested, suggesting that she required a wide range of reading materials. Not only did she often quote great works and scriptures, but she also used her knowledge to debate churchmen on legal and theological matters. The life tells of a three-day long argument she had with prominent Scottish churchmen over church observances. She used her knowledge to influence Scottish observance of Christianity to bring it in line with the rest of the Western church, standardising how mass was celebrated, and urging that her subjects receive communion at Easter, which they had previously refused to do because they believed themselves sinners and unworthy. She stressed that they should observe Lent from Ash Wednesday instead of the following Monday, as they were breaking fast on Sundays and thus only fasted for thirty six days instead of forty. She encouraged them to cease work on Sundays, and had the church forbid men to marry their stepmothers or sisters-in-law.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

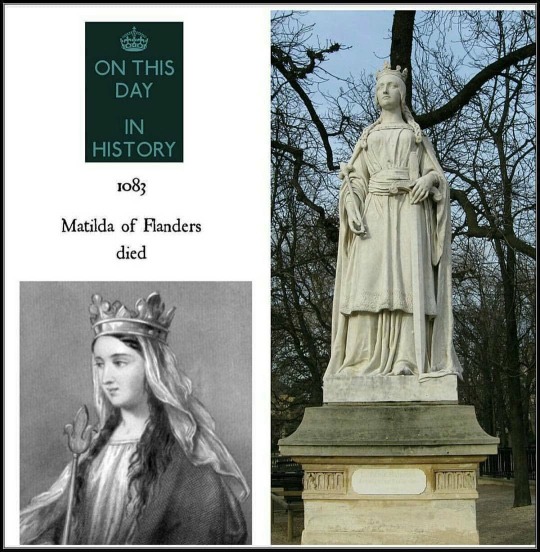

On This Day In History . 2 November 1083 . Matilda of Flanders died . . About Matilda; . 👑 Matilda of Flanders was born around 1031. She was the wife of William the Conqueror &, as such, Queen of England. She bore William nine or ten children who survived to adulthood, including two kings, William II & Henry I. . ◼ As a niece & granddaughter of kings of France, Matilda was of grander birth than William, who was illegitimate,& according to some suspiciously romantic tales, she initially refused his proposal on this account. Her descent from the Anglo-Saxon royal House of Wessex was also to become a useful card. Like many royal marriages of the period, it breached the rules of consanguinity, then at their most restrictive (to seven generations or degrees of relatedness); Matilda & William were third-cousins, once removed. She was about 20 when they married in 1051/2; William was some three years older, & had been Duke of Normandy since he was about eight. . ◼ The marriage appears to have been successful, Matilda was about 35, & had already produced most of her children, when William embarked on the Norman conquest of England, sailing in his flagship Mora, which Matilda had given him. She governed the Duchy of Normandy in his absence, joining him in England only after more than a year, & subsequently returning to Normandy, where she spent most of the remainder of her life, while William was mostly in his new kingdom. She was about 51 when she died in Normandy in 1083. . ◼ Apart from governing Normandy & supporting her brother’s interests in Flanders, Matilda took a close interest in the education of her children, who were unusually well educated for contemporary royalty. The boys were tutored by the Italian Lanfranc, who was made Archbishop of Canterbury in 1070, while the girls learned Latin in Sainte-Trinité Abbey in Caen, founded by William & Matilda as part of the papal dispensation allowing their marriage. . . . #OnThisDayInHistory #thisdayinhistory #theyear1083 #d2nov #MatildaofFlanders #HouseofFlanders #History #EnglishMonarchy #BritishMonarchy #otd #RoyalHistory #Flanders #QueenofEngland #QueenConsort #MedievalHistory #Normans #WilliamtheConqueror (at Caen, France) https://www.instagram.com/p/CHGKcbADksl/?igshid=f0d5e8a7o399

#onthisdayinhistory#thisdayinhistory#theyear1083#d2nov#matildaofflanders#houseofflanders#history#englishmonarchy#britishmonarchy#otd#royalhistory#flanders#queenofengland#queenconsort#medievalhistory#normans#williamtheconqueror

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saint of the Day - 28 May 2020 - Blessed Lanfranc of Canterbury OSB (c 1005-1089)

Saint of the Day – 28 May 2020 – Blessed Lanfranc of Canterbury OSB (c 1005-1089)

Saint of the Day – 28 May 2020 – Blessed Lanfranc of Canterbury OSB (c 1005-1089) Archbishop of Canterbury, Benedictine Abbot, celebrated Jurist, Scholar, Professor, spiritual writer, Reformer, negotiator – born in c 1005 in Pavia, Italy and died on 24 May 1089 in Canterbury, England of natural causes. He is also variously known as Lanfranc of Pavia, Lanfranc of Bec and Lanfranc of Canterbury. …

View On WordPress

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

April 21 is the feast day of St. Anselm of Canterbury, bishop and Doctor of the Church

Source of picture: https://anastpaul.wordpress.com

Life of St. Anselm

Born near Aosta in Italy in 1033, Anselm began his education under the tutelage of the monks of a local Benedictine monastery. After his mother passed away, Anselm observed a period of grief and mourning and then traveled throughout Europe. At that time, the spiritual and intellectual reputation of the monk Lanfranc, who belonged to the monastery of Bec in Normandy, was widespread. Anselm was drawn to Lanfranc, and in 1060 attached himself to Lanfranc's abbey. The community immediately recognized Anselm's unique abilities and he was soon teaching in the abbey school. He was made prior of the monastery in 1063.

It was during his days at Bec that Anselm composed his innovative works on the existence and nature of God.

Source of picture: www.art.com

His election to the position of abbot of the community in 1078 speaks to the love and regard in which he was held by his confreres. But Bec was not to be the end of his journey. In 1093 he was summoned to England to become the archbishop of Canterbury, succeeding his master and spiritual director Lanfranc. Anselm's years at Canterbury were not lacking in political controversy. He showed great courage in disputing William II and Henry I in regard to ecclesiastical abuses that were being visited upon the church by those kings. Twice he was banished while making appeals in Rome. Twice he returned to Canterbury, his abilities as an extraordinary theologian, negotiator, and statesman having added luster and authority to the cause of the church.

Throughout his years, Anselm maintained a strong allegiance to his monastic lifestyle and to his intellectual pursuits. He composed several philosophical and theological treatises, as well as a series of beautiful prayers and meditations in addition to his oftentimes inspirational correspondence. Anselm held the position of archbishop until his death in 1109.

Source: https://www.anselm.edu/about/history-mission/who-was-saint-anselm

A Prayer by St. Anselm of Canterbury

Source of picture: www.americaneedsfatima.org

O my God, teach my heart where and how to seek You,

where and how to find You.

You are my God and You are my all and I have never seen You.

You have made me and remade me,

You have bestowed on me all the good things I possess,

Still I do not know You.

I have not yet done that for which I was made.

Teach me to seek You.

I cannot seek You unless You teach me

or find You unless You show Yourself to me.

Let me seek You in my desire,

let me desire You in my seeking.

Let me find You by loving You,

let me love You when I find You.

Amen.

Source: Fr. John Sassani, Mary Ann McLaughlin: Meeting Christ in Prayer

#saints#St. Anselm of Canterbury#God#faith#christian religion#Christ#Jesus#Jesus Christ#teach my heart#where to seek God#how to seek God#where and how to find God#benedictine monk#bishop#Doctor of the Church#prayer

1 note

·

View note

Text

SAINT OF THE DAY (April 21)

On April 21, the Catholic Church honors Saint Anselm, the 11th and 12th-century Benedictine monk and archbishop best known for his writings on Christ's atonement and the existence of God.

In a general audience given on 23 September 2009, Pope Benedict XVI remembered St. Anselm as “a monk with an intense spiritual life, an excellent teacher of the young, a theologian with an extraordinary capacity for speculation, a wise man of governance, and an intransigent defender of the Church's freedom.”

St. Anselm, the Pope said, stands out as “one of the eminent figures of the Middle Ages who was able to harmonize all these qualities, thanks to the profound mystical experience that always guided his thought and his action.”

Anselm was born in Aosta, part of the Piedmont region of present-day Italy, around 1033.

While his father provided little in the way of moral or religious influence, his mother was a notably devout woman and chose to send Anselm to a school run by the Benedictine order.

The boy felt a profound religious calling during these years, spurred in part by a dream in which he met and conversed with God.

His father, however, prevented him from becoming a monk at age 15.

This disappointment was followed by a period of severe illness, as well as his mother's early death.

Unable to join the monks, and tired of mistreatment by his father, Anselm left home and wandered throughout parts of France and Italy for three years.

His life regained its direction in Normandy, where he met the Benedictine prior Lanfranc of Pavia and became his disciple.

Lanfranc recognized his pupil's intellectual gifts and encouraged his vocation to religious life.

Accepted into the order and ordained a priest at age 27, Anselm succeeded his teacher as prior in 1063 when Lanfranc was called to become abbot of another monastery.

Anselm became abbot of his own monastery in 1079.

During the previous decade, the Normans had conquered England, and they sought to bring monks from Normandy to influence the Church in the country.

Lanfranc became Archbishop of Canterbury, then asked Anselm to come and assist him.

The period after Lanfranc's death, in the late 1080s, was a difficult time for the English Church.

As part of his general mistreatment of the Church, King William Rufus refused to allow the appointment of a new archbishop.

Anselm had gone back to his monastery and did not want to return to England.

In 1092, however, he was persuaded to do so. The following year, the king changed his mind and allowed Anselm to become Archbishop of Canterbury.

But the monk was extremely reluctant to accept the charge, which would involve him in further struggles with the English crown in subsequent years.

For a three-year period in the early 12th century, Anselm's insistence on the self-government of the Church – against the claims of the state to its administration and property – caused him to be exiled from England.

But he was successful in his struggle and returned to his archdiocese in 1106.

In his last years, Anselm worked to reform the Church and continued his theological investigations – following the motto of “faith seeking understanding.”

After his death on 21 April 1109, his influence on the subsequent course of theology led Pope Clement XI to name him a Doctor of the Church in 1720.

He was canonized by Pope Alexander VI on 4 October 1494.

He is the patron saint of theologians and philosophers.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Great Seal of King William II of England (reigned 1087 – 1100).

William II was the second son of William the Conqueror. When his father died in 1087, he bequeathed his native Normandy to Robert Curthose, England to William Rufus, and five thousand pounds to Henry, his youngest.

William Rufus took the throne at the age of thirty. He neither married nor had any children, and was probably gay. He was as brutal as his father had been, but lacked a level-headed strength of purpose, and could never be trusted to keep a treaty.

He desperately wanted to possess Normandy as well as England, and soon became known as an exceptionally greedy king who extracted as much money from the English as he could, and allowed his followers to to the same.

Lanfranc, the Archbishop of Canterbury, died in 1089. The last remaining influence on William was gone, and he proceeded to treat the Church's possessions as if they were his own. He fell ill shortly afterwards, and promised to mend his ways, but this did not last long.

In 1094, he organized an episode of Normandy, but the Normans (in Britain) greatly distrusted him, and refused to join in. William enlisted the English instead, but when they arrived at Hastings with 10 shillings each for provisions, William took the money and sent them all home.

In 1097, Robert Curthose joined the First Crusade. To raise the money, he leased Normandy to William for 10,000 marks. William got the money by acts of extortion against landlords (who robbed their peasants to pay), and by pillaging shrines of the Church. By now, he was on dreadful terms with just about anyone.

William II was killed (or possibly murdered) in 1100 while hunting in the New Forest. The clergy refused to carry out services for him. It was said that, “He was loathsome to almost all his people, and abominable to God.”

#history#military history#crusades#first crusade#britain#norman britain#england#france#normandy#william ii#william the conqueror#robert curthose#henry i#lanfranc#anselm of canterbury

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 8.15 (before 1900)

636 – Arab–Byzantine wars: The Battle of Yarmouk between the Byzantine Empire and the Rashidun Caliphate begins. 717 – Arab–Byzantine wars: Maslama ibn Abd al-Malik begins the Second Arab Siege of Constantinople, which will last for nearly a year. 718 – Arab–Byzantine wars: Raising of the Second Arab Siege of Constantinople. 747 – Carloman, mayor of the palace of Austrasia, renounces his position as majordomo and retires to a monastery near Rome. His brother, Pepin the Short, becomes the sole ruler (de facto) of the Frankish Kingdom. 778 – The Battle of Roncevaux Pass takes place between the army of Charlemagne and a Basque army. 805 – Noble Erchana of Dahauua grants the Bavarian town of Dachau to the Diocese of Freising 927 – The Saracens conquer and destroy Taranto. 982 – Holy Roman Emperor Otto II is defeated by the Saracens in the Battle of Capo Colonna, in Calabria. 1018 – Byzantine general Eustathios Daphnomeles blinds and captures Ibatzes of Bulgaria by a ruse, thereby ending Bulgarian resistance against Emperor Basil II's conquest of Bulgaria. 1038 – King Stephen I, the first king of Hungary, dies; his nephew, Peter Orseolo, succeeds him. 1057 – King Macbeth is killed at the Battle of Lumphanan by the forces of Máel Coluim mac Donnchada. 1070 – The Pavian-born Benedictine Lanfranc is appointed as the new Archbishop of Canterbury in England. 1096 – Starting date of the First Crusade as set by Pope Urban II. 1185 – The cave city of Vardzia is consecrated by Queen Tamar of Georgia. 1224 – The Livonian Brothers of the Sword, a Catholic military order, occupy Tarbatu (today Tartu) as part of the Livonian Crusade. 1237 – Spanish Reconquista: The Battle of the Puig between the Moorish forces of Taifa of Valencia against the Kingdom of Aragon culminates in an Aragonese victory. 1248 – The foundation stone of Cologne Cathedral, built to house the relics of the Three Wise Men, is laid. (Construction is eventually completed in 1880.) 1261 – Michael VIII Palaiologos is crowned as the first Byzantine emperor in fifty-seven years. 1281 – Mongol invasion of Japan: The Mongolian fleet of Kublai Khan is destroyed by a "divine wind" for the second time in the Battle of Kōan. 1430 – Francesco Sforza, lord of Milan, conquers Lucca. 1461 – The Empire of Trebizond surrenders to the forces of Sultan Mehmed II. This is regarded by some historians as the real end of the Byzantine Empire. Emperor David is exiled and later murdered. 1483 – Pope Sixtus IV consecrates the Sistine Chapel. 1511 – Afonso de Albuquerque of Portugal conquers Malacca, the capital of the Malacca Sultanate. 1517 – Seven Portuguese armed vessels led by Fernão Pires de Andrade meet Chinese officials at the Pearl River estuary. 1519 – Panama City, Panama is founded. 1537 – Asunción, Paraguay is founded. 1540 – Arequipa, Peru is founded. 1549 – Jesuit priest Francis Xavier comes ashore at Kagoshima (Traditional Japanese date: 22 July 1549). 1592 – Imjin War: At the Battle of Hansan Island, the Korean Navy, led by Yi Sun-sin, Yi Eok-gi, and Won Gyun, decisively defeats the Japanese Navy, led by Wakisaka Yasuharu. 1599 – Nine Years' War: Battle of Curlew Pass: Irish forces led by Hugh Roe O'Donnell successfully ambush English forces, led by Sir Conyers Clifford, sent to relieve Collooney Castle. 1695 – French forces end the bombardment of Brussels. 1760 – Seven Years' War: Battle of Liegnitz: Frederick the Great's victory over the Austrians under Ernst Gideon von Laudon. 1843 – Tivoli Gardens, one of the oldest still intact amusement parks in the world, opens in Copenhagen, Denmark. 1863 – The Anglo-Satsuma War begins between the Satsuma Domain of Japan and the United Kingdom (Traditional Japanese date: July 2, 1863). 1893 – Ibadan area becomes a British Protectorate after a treaty signed by Fijabi, the Baale of Ibadan with the British acting Governor of Lagos, George C. Denton. 1899 – Fratton Park football ground in Portsmouth, England is officially first opened.

0 notes

Text

I remember reading the letters of Lanfranc, Archbishop of Canterbury. The dude roasts people like mad.

The chronicle of the monk Herbert of Reichenau for the year 1021 ends “My brother Werner was born on November 1.“

1021 was not an uneventful year. The emperor began a campaign into Italy. Illustrious abbots died. There was an earthquake. But Herbert took the time to note, at the end of the year, that his brother was born.

Of such acts of tenderness is history made.

122K notes

·

View notes