#Anna Samuil

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Someone with a Stalin pfp posting this is brutally ironic, since the Bund was forcibly disbanded in 1921 by the Bolsheviks and a great deal of former Bundists met with grim fates at the hands of the Soviets:

David Petrovsky, Mikhail Liber, Fanny Nyurina, Isaak Nusinov, Yakov Bykin, Yakov Drobnis, Joseph Meerzon, Isaak Illich Rubin, Moisey Rukhimovich, Mikhail Mednikov, Moshe Gutman, Mark Donskoy, Abram Merezhin, Aleksandr Zolotarev, and Israel Leplevsky were all shot during the Purges.

Victor Alter and Henryk Ehrlich were both shot on Stalin's orders.

Aron Sokolovsky, Mikhail Borodin, Isaak Goldstein, Anna Rozental, Aron Vainshtein, Moisei Natanovich Gurvich, and Moisei Rafes died in the GULAG or Sovet prison.

Samuil Agurskii died in Soviet exile.

Zakhar Grinberg died in Soviet prison after being beaten to death.

To be fair, though, Polish Bundists often did not fare much better.

Simon Dubnow, Mordechai Gebirtig, Michał Klepfisz, Pati Kremer, Maurycy Orzech, Aron Skrobek, and Abraham Blum were all murdered by the Nazis and Szmul Zygielbojm committed suicide to protest the apathy of the Western Allies and Polish government in exile with regard to the Holocaust.

#thererisesaredstar#bund#antisemitism#russian history#polish history#ukrainian history#jewish history

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Orest Adamovich Kiprensky (Russian: Орест Адамович Кипренский 24 March [O.S. 13 March] 1782 – 17 October [O.S. 5 October] 1836) was a leading Russian portraitist in the Age of Romanticism.

His most familiar work is probably his portrait of Alexander Pushkin (1827), which prompted the poet to remark that "the mirror flatters me".

Orest was born in the village of Nezhnovo in the Saint Petersburg Governorate on 24 March [O.S. 13 March] 1782. He was an illegitimate son of a landowner Alexey Dyakonov, hence his name, derived from Kypris, one of the Greek names for the goddess of love. He was raised in the family of Adam Shvalbe, a serf. Although Kiprensky was born a serf, he was released from the serfdom upon his birth and later his father helped him to enter a boarding school at the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg in 1788 (when Orest was only six years old).

He studied at the boarding school and the academy itself until 1803. He lived at the academy for three more years as a pensioner to fulfill requirements necessary to win the Major Gold medal. Winning the first prize for his work Prince Dmitri Donskoi after the Battle of Kulikovo (1805) enabled the young artist to go abroad to study art in Europe.

A year before his graduation, in 1804, he painted the portrait of Adam Shvalbe, his foster father (1804), which was a great success. The portrait so impressed his contemporaries, that later members of the Naples Academy of Arts took it for the painting by some Old Master – Rubens or van Dyck. Kiprensky had to ask the members of the Imperial Academy of Arts for letters supporting his authorship.

After that, Kiprensky lived in Moscow (1809), Tver 1811, Saint Petersburg 1812, in 1816–1822 he lived in Rome and Napoli. In Italy he met a local girl Anna Maria Falcucci (Mariucci), to whom he became attached. He bought her from her dissolute family and employed as his ward. On leaving Italy, he sent her to a Roman Catholic convent.

In 1828, Kiprensky came back to Italy, as he got a letter from his friend Samuil Galberg, informing him that they had lost track of Mariucci. Kiprensky found Mariucci, who had been transferred to another convent. In 1836 he eventually married her. He had to convert into Roman Catholicism from Russian Orthodoxy for this marriage to happen. He died by pneumonia in Rome later that year. He is buried in the church of Sant'Andrea delle Fratte.

Orest Adamovich Kiprensky - Self Portrait 1828

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Random Drawing: Prince Gremin (Ferruccio Furlanetto) and Tatjana (Anna Samuil) from Eugene Onegin (Salzburg, conducted by Barenboim) Video I used for reference, link here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hF9MZ3nacrk

Currently obsessed with Furlanetto singing Prince Gremin’s aria!!!

Not only a great basso, FF is also a wonderful actor! I really like how he reflects his deep and sincere love towards his far-younger wife, Tatjana and how he cares a lot about her, even in small meaningful gestures. Like one moment towards his last scene where he tenderly forbids Tatjana to light a cigarette. OW MAN! It tickles something that had long been dormant in me (thanks Hvorostovsky scene from Met’s Eugene Onegin). This Gremin is strong, straightforward (seen from how he acts toward people he hates during his aria), but also vulnerable (from how he describe the love for Tatjana that has been consuming himself), and acts as fatherly figure. Just AAAAAAWWWWWWWW~~~

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

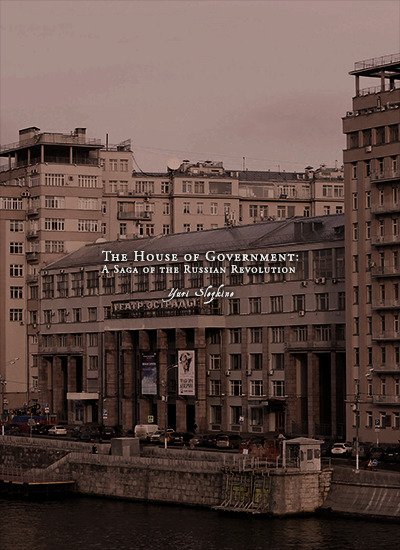

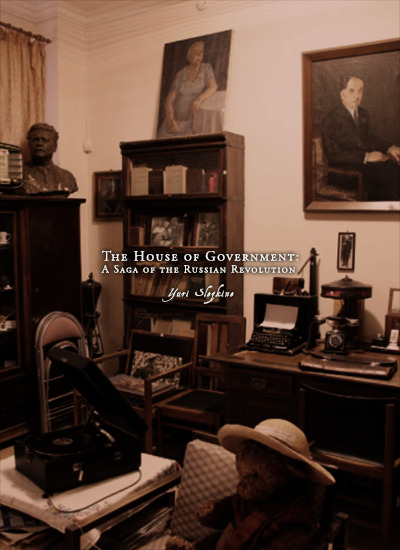

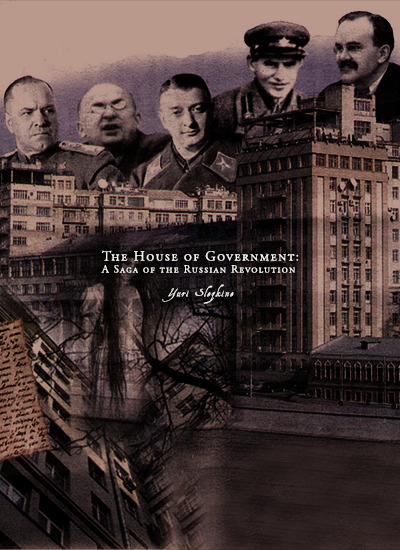

Favorite History Books || The House of Government: A Saga of the Russian Revolution by Yuri Slezkine ★★★★☆

In the House of Government, some residents were more important than others because of their position within the Party and state bureaucracy, length of service as Old Bolsheviks, or particular accomplishments on the battlefield and the “labor front.” In this book, some characters are more important than others because they made provisions for their own memorialization or because someone else did it in their behalf.

One of the leaders of the Bolshevik takeover in Moscow and chairman of the All-Union Society for Cultural Ties with Foreign Countries, Aleksandr Arosev (Apts. 103 and 104), kept a diary that his sister preserved and one of his daughters published. One of the ideologues of Left Communism and the first head of the Supreme Council of the National Economy, Valerian Osinsky (Apts. 18, 389), maintained a twenty-year correspondence with Anna Shaternikova, who kept his letters and handed them to his daughter, who deposited them in a state archive before writing a book of memoirs, which she posted on the Internet and her daughter later published. The most influential Bolshevik literary critic and Party supervisor of Soviet literature in the 1920s, Aleksandr Voronsky (Apt. 357), wrote several books of memoirs and had a great many essays written about him (including several by his daughter). The director of the Lenin Mausoleum Laboratory, Boris Zbarsky (Apt. 28), immortalized himself by embalming Lenin’s body. His son and colleague, Ilya Zbarsky, took professional care of Lenin’s body and wrote an autobiography memorializing himself and his father. “The Party’s Conscience” and deputy prosecutor general, Aron Solts (Apt. 393), wrote numerous articles about Communist ethics and sheltered his recently divorced niece, whose daughter wrote a book about him (and sent the manuscript to an archive). The prosecutor at the Filipp Mironov treason trial in 1919, Ivar Smilga (Apt. 230), was the subject of several interviews given by his daughter Tatiana, who had inherited his gift of eloquence and put a great deal of effort into preserving his memory. The chairman of the Flour Milling Industry Directorate, Boris Ivanov, “the Baker” (Apt. 372), was remembered by many of his House of Government neighbors for his extraordinary generosity.

Lyova Fedotov, the son of the late Central Committee instructor, Feodor Fedotov (Apt. 262), kept a diary and believed that “everything is important for history.” Inna Gaister, the daughter of the deputy people’s commissar of agriculture, Aron Gaister (Apt. 162), published a detailed “family chronicle.” Anatoly Granovsky, the son of the director of the Berezniki Chemical Plant, Mikhail Granovsky (Apt. 418), defected to the United States and wrote a memoir about his work as a secret agent under the command of Andrei Sverdlov, the son of the first head of the Soviet state and organizer of the Red Terror, Yakov Sverdlov. As a young revolutionary, Yakov Sverdlov wrote several revealing letters to Andrei’s mother, Klavdia Novgorodtseva (Apt. 319), and to his young friend and disciple, Kira Egon-Besser. Both women preserved his letters and wrote memoirs about him. Boris Ivanov, the “Baker,” wrote memoirs about Yakov’s and Klavdia’s life in Siberian exile. Andrei Sverdlov (Apt. 319) helped edit his mother’s memoirs, coauthored three detective stories based on his experience as a secret police official, and was featured in the memoirs of Anna Larina-Bukharina (Apt. 470) as one of her interrogators. After the arrest of the former head of the secret police investigations department, Grigory Moroz (Apt. 39), his wife, Fanni Kreindel, and eldest son, Samuil, were sent to labor camps, and his two younger sons, Vladimir and Aleksandr, to an orphanage. Vladimir kept a diary and wrote several defiant letters that were used as evidence against him (and published by later historians); Samuil wrote his memoirs and sent them to a museum. Eva Levina-Rozengolts, a professional artist and sister of the people’s commissar of foreign trade, Arkady Rozengolts (Apt. 237), spent seven years in exile and produced several graphic cycles dedicated to those who came back and those who did not. The oldest of the Old Bolsheviks, Yelena Stasova (Apts. 245, 291), devoted the last ten years of her life to the ���rehabilitation” of those who came back and those who did not.

Yulia Piatnitskaya, the wife of the secretary of the Comintern Executive Committee, Osip Piatnitsky (Apt. 400), started a diary shortly before his arrest and kept it until she, too, was arrested. Her diary was published by her son, Vladimir, who also wrote a book about his father. Tatiana (“Tania”) Miagkova, the wife of the chairman of the State Planning Committee of Ukraine, Mikhail Poloz (Apt. 199), regularly wrote to her family from prison, exile, and labor camps. Her letters were preserved and typed up by her daughter, Rada Poloz. Natalia Sats, the wife of the people’s commissar of internal trade, Izrail Veitser (Apt. 159), founded the world’s first children’s theater and wrote two autobiographies, one of which dealt with her time in prison, exile, and labor camps. Agnessa Argiropulo, the wife of the secret police official who proposed the use of extrajudicial troikas during the Great Terror, Sergei Mironov, told the story of their life together to a Memorial Society researcher, who published it as a book. Maria Denisova, the wife of the Red Cavalry commissar, Yefim Shchadenko (Apts. 10, 505), served as the prototype for Maria in Vladimir Mayakovsky’s poem A Cloud in Pants. The director of the Moscow-Kazan Railway, Ivan Kuchmin (Apt. 226), served as the prototype for Aleksei Kurilov in Leonid Leonov’s novel, The Road to Ocean. The Pravda correspondent, Mikhail Koltsov (Apt. 143), served as the prototype for Karkov in Ernest Hemingway’s novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls. “Doubting Makar,” from Andrei Platonov’s short story by the same name, participated in the building of the House of Government. All Saints Street, on which the House of Government was built, was renamed in honor of Aleksandr Serafimovich, the author of The Iron Flood (Apt. 82). Yuri Trifonov, the son of the Red Army commissar and chairman of the Main Committee on Foreign Concessions, Valentin Trifonov (Apt. 137), wrote a novella, The House on the Embankment, that immortalized the House of Government. His widow, Olga Trifonova, would become the director of the House on the Embankment Museum, which continues to collect books, letters, diaries, stories, paintings, photographs, gramophones, and other remnants of the House of Government.

#historyedit#litedit#soviet history#russian history#european history#history#nanshe's graphics#history books

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fr, 18. Dez 2015 | 19 Uhr

Schiller Theater Berlin

MOZART Il dissoluto punito, ossia il Don Giovanni

DON GIOVANNI | Christopher Maltman

DONNA ANNA | Anna Samuil

DON OTTAVIO | Peter Sonn

KOMTUR | Jan Martiník

DONNA ELVIRA | Dorothea Röschmann

LEPORELLO | Luca Pisaroni

MASETTO | Grigory Shkarupa

ZERLINA | Narine Yeghiyan

Chor der Staatsoper Unter den Linden Berlin

Staatskapelle Berlin

Massimo Zanetti | Musikalische Leitung

0 notes

Text

Sa, 23. Dez 2017 | 15 Uhr

Staatsoper Unter den Linden Berlin

HUMPERDINCK Hänsel und Gretel

PETER | Arttu Kataja

GERTRUD | Anna Samuil

HÄNSEL | Natalia Skrycka

GRETEL | Evelin Novak

DIE KNUSPERHEXE | Stephan Rügamer

SANDMÄNNCHEN | Corinna Scheurle

TAUMÄNNCHEN | Sarah Aristidou

Kinderchor der Staatsoper Unter den Linden Berlin

Staatskapelle Berlin

Sebastian Weigle | Musikalische Leitung

0 notes

Text

Prophetess. via /r/islam

Prophetess.

As-salamu alaykum,

As much of us are aware the Qur'an establishes give or take 25 different Prophets, starting with the Prophet Adam and ending with the final Prophet Muhammad. Ahadith and other Islamic literature expand on this list, mentioning other Prophets such as Urmiya and Samuil. The Qur'an alludes to even more, stating that "We assuredly sent amongst every People a messenger," though "some whose story We have not related to thee." This has led to some Muslims believing that figures such as Zoroaster, Mani, Krishna, and Buddha may have been Prophets.

But notably missing from the aforementioned list, especially when compared to Judeo-Christianity, is any Prophetess. In Judaism, Sarah, Miriam, Huldah, Deborah, Hannah, Abigail, and Esther comprise the group known as the 'Seven Prophetesses'. From the list, only Sarah, wife of Abraham, and Miriam, sister of Moses and Aaron, have any notable mention in Islam. Christianity typically agrees with Judaism's 'Seven Prophetesses', while also adding in others, such Anna the Prophetess. While the thought of a female Prophet seems alien to Islam, many Islamic scholars regard multiple women as Prophetesses.

Mary, Mother of Christ, is often one of the first Prophetesses cited in Islam. As early as the tenth century, Islamic scholars, such as the Andalusian theologian Al-Qurtubi firmly believed that Mary had been a Prophetess: "Truly Maryam is a prophetess because God inspired her through the angel in the same way He inspired the rest of the male prophets." This sentiment was echoed by other scholars, such as Ibn Hazm. Al-Qurtubi based his view on the Qur'an itself, asserting that the Annunciation narrative found in Chapter 19th reconciled Mary's Prophethood. In Hadith, Mary is also listed among the women to attain perfection, which is also evidence used to support Mary's Prophethood.

While Al-Qurtubi only argued that Mary had been a Prophetess, other scholars hold different opinions, arguing that Eve, Wife of Adam, Sarah, Mother of Isaac, Jochebed, Mother of Moses and Aaron, and Asiyah, Wife of the Pharaoh, had also been Prophetesses. Notably, only Sarah is regarded as a Prophetess in Jewish and Christian thought. According to Al-Ash'ari, founder of the Asharite theology, any figure who received commandment from God, either directly or via an Angel was considered a Prophet(ess).

This post was not meant to convince anyone that any of the aforementioned women are Prophetesses, rather it was merely a post meant to learn about other points of view in Islam and too allow for discussion and conversation.

Submitted August 17, 2020 at 05:26AM by HelpMeFindTutter via reddit https://ift.tt/2CxF14T

0 notes

Video

youtube

The Best of Shostakovich

1953–19611953 starb Stalin, und Schostakowitsch veröffentlichte seine 10. Sinfonie in e-Moll, seine Abrechnung mit dem Diktator.

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dmitri_Dmitrijewitsch_Schostakowitsch#1937%E2%80%931953_Komponieren_unter_Stalin

1937–1953 Komponieren unter Stalin

Nachdem er seine 4. Sinfonie in c-Moll aufgrund des kritischen Prawda-Artikels zurückgezogen und in der Schublade hatte verschwinden lassen, begann Schostakowitsch am 18. April 1937 unter der offiziellen Parole der „praktischen Antwort eines Sowjetkünstlers auf gerechte Kritik“ die Arbeit an seiner gemäßigten 5. Sinfonie in d-Moll auf der Krim. Zurück in Leningrad erfuhr er, dass der Mann seiner Schwester verhaftet und sie selbst nach Sibirien deportiert worden war. [3]

Nach der Uraufführung wurde die 5. Sinfonie offiziell als die Rückkehr des verlorenen Sohnes in die linientreue Kulturpolitik dargestellt. Das Werk wurde ein großer internationaler Erfolg, lange Zeit wurde das Marschfinale als Verherrlichung des Regimes angesehen. Die in ihrer Echtheit umstrittenen Memoiren Schostakowitschs behaupten, dass der Triumphmarsch in Wirklichkeit ein Todesmarsch sei:

„Was in der Fünften vorgeht, sollte meiner Meinung nach jedem klar sein. Der Jubel ist unter Drohungen erzwungen. […] So als schlage man uns mit einem Knüppel und verlange dazu: Jubeln sollt ihr! Jubeln sollt ihr! Und der geschlagene Mensch erhebt sich, kann sich kaum auf den Beinen halten. Geht, marschiert, murmelt vor sich hin: Jubeln sollen wir, jubeln sollen wir. Man muss schon ein kompletter Trottel sein, um das nicht zu hören.“

Die 7. Sinfonie in C-Dur geht in dieser Doktrin noch weiter und gilt als Schostakowitschs bekanntestes Werk. Zu dieser Sinfonie sagte er laut den Memoiren:

„Ich empfinde unstillbaren Schmerz um alle, die Hitler umgebracht hat. Aber nicht weniger Schmerz bereitet mir der Gedanke an die auf Befehl Stalins Ermordeten …“

Das Werk entstand 1941 zur Zeit der Belagerung Leningrads durch Hitlers Truppen, während Schostakowitsch der Feuerwehr zugeteilt war und unter Granatenbeschuss an seinem Werk arbeitete. Der Pekinger Neurologe Wang Dajue berichtete, dass er in den 1950er Jahren mit einem führenden sowjetischen Neurochirurgen zusammengearbeitet habe; dieser habe ihm erzählt, dass Schostakowitsch in Leningrad von einem deutschen Schrapnell getroffen worden sei und er ihn einige Jahre später mit Röntgenstrahlen untersucht habe, wobei er einen Metallsplitter im Cornu inferius des linken Hirnventrikels gefunden habe. Dieses habe verursacht, dass Schostakowitsch während des seitlichen Neigens des Kopfes unwillkürlich immer wieder verschiedene Melodien gehört habe, die er dann auch zum Komponieren verwendet habe.[4] Dies ist jedoch nicht durch unabhängige Quellen belegt, so dass an der Zuverlässigkeit dieser Aussage gezweifelt werden kann.

Im Oktober 1941 wurde Schostakowitsch mit seiner Familie aus Leningrad ausgeflogen und konnte die Sinfonie in Kuibyschew (Samara) fertigstellen, wo sie am 5. März 1942 vom dorthin ausgelagerten Orchester des Bolschoi-Theaters unter Leitung von Samuil Samossud uraufgeführt wurde. Die Moskauer Erstaufführung am 27. März fand ebenfalls unter lebensgefährlichen Umständen statt, doch selbst ein Luftalarm konnte die Zuhörer nicht dazu bewegen, die Schutzräume aufzusuchen. Stalin war daran interessiert, die Sinfonie auch außerhalb der Sowjetunion als Symbol des heroischen Widerstands gegen den Faschismus bekannt zu machen. Am 22. Juni dirigierte sie Sir Henry Wood in London, und Arturo Toscanini leitete die erste Aufführung der Sinfonie in den Vereinigten Staaten, die am 19. Juli 1942 in New York mit dem NBC Symphony Orchestra stattfand und Schostakowitsch auf die Titelseite des Time Magazine brachte[5]. Sein Wunsch nach einer Aufführung in Leningrad ging kurze Zeit später in Erfüllung: Ein Sonderflugzeug durchbrach die Luftblockade, um die Orchesterpartitur nach Leningrad zu fliegen. Das Konzert vom 9. August (Dirigent: Karl Eliasberg) wurde von allen sowjetischen Rundfunksendern übertragen. Schostakowitsch erhielt den Stalinpreis für sein Werk, da es als Hommage an den Widerstandswillen der von deutschen Truppen eingeschlossenen hungernden Bevölkerung aufgefasst wurde. Die Interpretation der Sinfonie bleibt dabei bis heute umstritten. Die „Memoiren“ selbst sprechen davon, dass Schostakowitsch weder Hitler noch Stalin als Ziel seiner Sinfonie sah. Vielmehr findet sich im ersten Satz ein Motiv, das entweder als „Hitler-“ oder als „Stalin-Motiv“ gedeutet wird. Tatsächlich handelt es sich dabei um eine Variation auf das Gewaltthema aus der Oper Lady Macbeth von Mzensk. Es taucht in einer Form auf, die in der Oper für die staatliche Gewalt in Form der Polizei und als Bedingung für den Mord verwendet wird. Die 7. Sinfonie wurde Schostakowitsch aufgrund ihrer nicht eindeutigen Auslegung in den Reden Schdanows im Umkreis der Verfolgung sowjetischer Komponisten 1948 vorgeworfen.

Auch die epische 8. Sinfonie in c-Moll, 1943 in Moskau unter Jewgeni Mrawinski uraufgeführt und oft als „Stalingrader Sinfonie“ bezeichnet, entstand unter dem Eindruck der Kriegsgeschehnisse. Im Gegensatz zu den Erwartungen, er würde nach der „Leningrader“ etwas ähnlich Triumphales schreiben, das dem schicksalhaften Sieg der Sowjetunion über die vorrückenden deutschen Truppen in Stalingrad Ausdruck verlieh, ist die 8. Sinfonie in weiten Teilen nachdenklich, melancholisch und zeigt im Ergebnis keine Befriedigung über den Sieg, sondern kündet von individuellem Leid und der Trauer über die unglaublichen Verluste an Menschenleben. Die Sinfonie meidet in ihrem humanistischen Engagement große heroische Gesten. Sind der grandiose erste Satz (Adagio) und die beiden folgenden Sätze noch von apokalyptischer Steigerung, teilweise aggressiven und schnellen Tempi geprägt, erklingen in den beiden letzten Sätzen grüblerische, leise Töne, bevor der letzte Satz still und offen verklingt. Nach dem Krieg fiel die 8. Sinfonie der Zensur zum Opfer, sie wurde nicht mehr aufgeführt, und sogar viele Rundfunkmitschnitte wurden gelöscht.

Nach dem Ende des gewonnenen Zweiten Weltkriegs erwartete die Musikwelt eine Triumphsinfonie − etwa im Stile Beethovens Neunter. Doch Schostakowitsch fiel mit seiner 9. Sinfonie in Es-Dur bei der sowjetischen Kritik erneut durch, denn es handelt sich stattdessen um ein Werk von fast haydnscher Schlichtheit, welches mit grotesker „Zirkusmusik“ endet − weit entfernt von einem grandiosen Finale.

Bisher aber ist nicht erkannt worden, dass Schostakowitsch hier das Lied Lob des hohen Verstandes aus Gustav Mahlers Des Knaben Wunderhorn zitierend versteckt, in welchem der Esel entscheidet, dass der Kuckuck schöner singe als die Nachtigall. Hinweise dazu gibt der Artikel von Jakob Knaus in der Neuen Zürcher Zeitung vom 29. Oktober 2016 unter dem Titel Das Geheimnis von Schostakowitschs 9. Sinfonie: Der Weiseste der Weisen – ein Esel?. Stalin war nach Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs als großer Sieger und als „Weisester der Weisen“ bezeichnet worden. Dass der Esel den Kuckuck als Sänger der Nachtigall vorzieht, liegt darin begründet, dass der Kuckuck nur zwei Töne singt und deshalb vom breiten Volk verstanden werden kann; die Nachtigall hingegen singt zu kompliziert und muss deshalb als Formalistin verurteilt werden.[6]

Nachdem Schostakowitsch schon vor dem Krieg im Zentrum der Kritik gestanden hatte, entzündete sich nach Debatten über zeitgenössische sowjetische Dichter und Literaten (unter anderem Anna Achmatowa) nun erneut eine Diskussion über moderne sowjetische Musik: Schostakowitsch und viele namhafte Komponisten der Sowjetunion, z. B. Prokofjew oder Chatschaturjan, wurden 1948 vom sowjetischen Komponistenverband und dessen Präsidenten Tichon Chrennikow unter ideologischer Führung Andrej Schdanows wiederum des „Formalismus“ und der „Volksfremdheit“ beschuldigt. Schostakowitsch komponierte weiterhin, ohne auf die Vorwürfe einzugehen. Praktisch alle bedeutenden Werke dieser Zeit waren ausschließlich für die Schublade bestimmt und kamen erst in der Zeit des „Tauwetters“ bzw. erst nach der politischen Wende 1989/1990 zur Uraufführung. Seine persönliche Lage entsprach weiterhin derjenigen der Zeit nach 1936: über sein Schicksal bestimmte einzig die Gnade Stalins. Weltweit mittlerweile ein berühmter und angesehener Komponist, sah sich Schostakowitsch in der Sowjetunion erneut in der Lage, ständig zwischen der drohenden Verhaftung einerseits und Auszeichnungen für sein Werk andererseits zu stehen.

Im Kampf gegen den „Formalismus“ sah sich Schostakowitsch, obwohl mehrfach mit Stalin-Preisen ausgezeichnet, vor allem nach 1948 heftig attackiert. Er profilierte sich mit Werken, die dem sozialistischen Realismus scheinbar unterzuordnen waren, und hielt problematischere Werke zurück (etwa das emotional aufgeladene 1. Violinkonzert, den Liederzyklus Aus jüdischer Volkspoesie und das 4. Streichquartett mit seinen unverkennbar jüdischen Themen im Finale). Ein Werk mit besonders deutlicher Sprache war das im Ergebnis der repressiven Kulturpolitik, der sogenannten Schdanowschtschina, entstandene satirische Stück Antiformalistischer Rajok, in der er zwei fiktive Genossen − Genosse Eins (Stalin) und Genosse Zwei (Schdanow) − auf jeweils eine georgische Volksliedmelodie bzw. einen Walzer die Vorstellungen der Führung von der geforderten „positiven“ und „optimistischen“ Grundstimmung in der sowjetischen Musik singen ließ. Schostakowitsch hielt das brisante Stück zeit seines Lebens zurück.

In dieser Zeit (1950/51) entstanden auch die 24 Präludien und Fugen op. 87, inspiriert von der Teilnahme Schostakowitschs an den Feierlichkeiten in Leipzig anlässlich des 200. Todestages von Johann Sebastian Bach.

0 notes

Text

Program Beethoven al Orchestrei Române de Tineret în Festivalul ”Enescu”(6 septembrie 2017, București)

Program Beethoven al Orchestrei Române de Tineret în Festivalul ”Enescu”(6 septembrie 2017, București)

Astăzi, miercuri, 6 septembire 2017, la ora 20.00, la Sala Mare a Palatului, program Beethoven al Orchestrei Române de Tineret, care îl va avea la pupitrul dirijoral pe Domingo Hindoyan: Concertul nr. 1 pentru pian și orchestră în Do major, op. 15 – solist: Sergio Tiempo; Simfonia a IX-a în re minor, op. 125. Soliști: Anna Samuil (soprană), Roxana Constantinescu (mezzosoprană), Stefan Vinke…

View On WordPress

#Beethoven#Cristian Mandeal#cultură#Domingo Hindoyan#EFNYO (European Federation of National Youth Orchestras)#eveniment#festivalul Enescu#Ion Iosif Prunner#Marin Cazacu#muzică clasică#Orchestra Romana de Tineret#Pușa Roth#Sergio Tiempo#Simfonia a IX-a în re minor op. 125#”Orchestra Română de Tineret – spirit enescian şi tradiţie europeană”#”Prietenii muzicii – Serafim Antropov”

0 notes

Text

Stemme Shrinks Then Soars

Review – Götterdämmerung (BBC Proms, Sunday 28 July 2013)

Brünnhilde – Nina Stemme Siegfried – Andreas Schager Hagen – Mikhail Petrenko Gunther – Gerd Grochowski Gutrune & Third Norn – Anna Samuil Waltraute & Second Norn – Waltraud Meier First Norn –…

View Post

#Aga Mikolaj#Andreas Schager#Anna Lapkovskaja#Anna Samuil#Daniel Barenboim#Gerd Grochowski#Johannes Martin Kränzle#Margarita Nekrasova#Maria Gortsevskaya#Mikhail Petrenko#Nina Stemme#Staatskapelle Berlin#Waltraud Meier

0 notes

Text

So, 13. Dez 2015 | 18 Uhr

Schiller Theater Berlin

MOZART Il dissoluto punito, ossia il Don Giovanni

DON GIOVANNI | Christopher Maltman

DONNA ANNA | Anna Samuil

DON OTTAVIO | Peter Sonn

DONNA ELVIRA | Dorothea Röschmann

KOMTUR | Jan Martiník

LEPORELLO | Luca Pisaroni

MASETTO | Grigory Shkarupa

ZERLINA | Narine Yeghiyan

Chor der Staatsoper Unter den Linden Berlin

Staatskapelle Berlin

Massimo Zanetti | Musikalische Leitung

0 notes

Text

All That Glistens …

Review – Das Rheingold (BBC Prom – Monday 22 July 2013)

Wotan – Iain Paterson Fricka – Ekaterina Gubanova Alberich – Johannes Martin Kränzle Loge – Stephan Rügamer Fasolt – Stephen Milling Fafner – Eric Halfvason Mime – Peter Bronder Woglinde – Aga Mikolaj

View Post

#Aga Mikolaj#Anna Lapkovskaja#Anna Larsson#Anna Samuil#Daniel Barenboim#Ekaterina Gubanova#Eric Halfvason#Iain Paterson#Jan Buchwald#Johannes Martin Kränzle#Maria Gortsevskaya#Marius Vlad#Peter Bronder#Staatskapelle Berlin#Stephan Rügamer#Stephen Milling

0 notes