#Anglo-Irish War

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Kathleen Ní Houlihan | Ireland Personified and Irish Nationalism

Kathleen Ni Houlihan (Caitlín Ní Uallacháin, literally, “Kathleen, daughter of Houlihan”) is a mythical symbol and emblem of Irish nationalism found in literature and art, sometimes representing Ireland as a personified woman. The figure of Kathleen Ni Houlihan has also been invoked in nationalist Irish politics. Kathleen Ni Houlihan is sometimes spelled as Cathleen Ni Houlihan, and the figure is…

View On WordPress

#"A Mother"#Abbey Theatre#Anglo-Irish War#Caitlín Ní Uallacháin#Daughter of Ireland#Declan Kerr – Irish Art#IRA#Ireland personified#Irish Nationalism#James Joyce#Kathleen Ni Houlihan#Lady Gregory#Northern Ireland#The Shadow of the Gunman#The Troubles#United Kingdom#William Butler Yeats

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

'Can you cook dinner?' shouted a heckler. 'Yes! Can you drive a coach and four?' replied Constance Markievicz (1868-1927) on her campaign for women's votes driving her carriage with four matched grey horses. The daughter of an Arctic explorer in an Anglo-Irish family, she fought against the British occupation of Ireland and was sentenced to death, though released in 1917 under a general amnesty. Arrested again the following year for protesting conscription in the First World War, she stood for Sinn Féin and took 66 per cent of the vote from prison, and refused to take her seat – then she was in any case, still imprisoned.

"Normal Women: 900 Years of Making History" - Philippa Gregory

#book quotes#normal women#philippa gregory#nonfiction#questions#dinner#heckler#stagecoach#carriage#constance markievicz#anglo irish#british occupation#ireland#death sentence#capital punishment#10s#1910s#20th century#amnesty#protesting#conscription#ww1#wwi#world war one#world war 1#first world war#sinn fein#imprisoned#gray horse#campaigning

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today in 1921, the Anglo Irish treaty was signed.

Effectively rubber stamping the partition of Ireland.

And some fuckers out there still think we deserved it!

Why don’t we split THEIR countries in half and see how they like it! (HYPOTHETICAL!)

And no I’m not lionising the anti-treaty faction.

Most of them were dogshit reactionaries what didn’t give a shit about the north either.

#dougie rambles#personal stuff#ireland#vent post#political crap#history#irish history#partition#fuck loyalism#politics#irish politics#irish civil war#Anglo Irish treaty

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Episode 53 – The Provisional Government and the Anti-Treaty Side

What should have been a cause for celebration – the ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, ending 800 years of British dominance – was the final strike needed to shatter the Irish movement for liberation. Eamon DeValera, president of the Dail and leader of the Irish Republican movement, so incensed by the ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, renounced his presidency and led a number of Dail members out in protest. Arthur Griffith was elected the new Dail President and seven days later, Michael Collins was named Chairman of the Provisional Government. Griffith and Collins, who spearheaded the efforts to negotiation the Anglo-Irish treaty, were now responsible for handling the transition from being a British colony to British dominion and prevent a civil war.

During the Dail debates, Collins described the Anglo-Irish Treaty as a “steppingstone” towards Irish independence. I would tweak that thought slightly by calling it a series of steppingstones, the first one being the creation of the Provisional Government of Ireland. What was the Provisional Government?

The Provisional Government was created by Article 17 of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. It was meant to be a temporary government to handle the transition from being purely a colonized nation to the Irish Free State. Once a constitution was passed, the Provisional Government would step down for the constitutionally sanctioned government of the Irish Free State. The Provisional Government would go through two different governments: the first government led by Collins lasted from January 14th until the June General Election, which elected the second government. This was led by William Cosgrave, Minister of Home Affairs, and ruled until the approval of the Irish Constitution on December 6th, 1922. Despite being created by the treaty, Britain did not actually confer any powers to the Provisional Government until April 1922. Additionally, the Provisional Government was supposed to be answerable to a House of the Parliament, but did not specify a specific parliament or even create one.

The first Provisional Government consisted of the following members:

Michael Collins: Chairman

Eamonn Duggan: Minister for Home Affairs

W. T. Cosgrave: Minister for Local Government

Kevin O’Higgins: Minister for Economic Affairs

Fionan Lynch: Minister for Education

Patrick Hogan: Minister for Agriculture

Joseph McGrath: Minister for Labour

J. J. Walsh: Postmaster-General

While Britain did not acknowledge the Dail as a legitimate form of government, Ireland was ruled by both the Provisional Government and the Dail. The Dail considered of a president, Arthur Griffith, and his own cabinet. The Provisional Government, technically, was not answerable to the Dail until a new election was called. This election would be held in June and took their oaths in September 1922. Still both sides worked closely together since many of their ministers served in both governments.

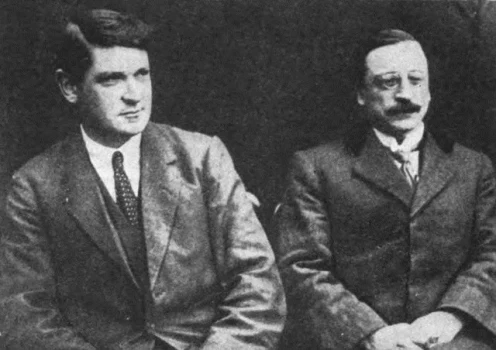

Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith

[Image Description: A picture of two white men in suits. The man on the left is leaning to the left. He is a white man with brown hair. He is wearing a white button down shirt and a black tie with small dots. he is wearing a dark grey vest and a light grey suit. The man on the right is sitting straight with his hand in his lap. He is white with brown hair, a thick brown mustache, and round, wire frame glasses. He is wearing a white, button down shirt, a light tie, and a dark suit with black lapels]

The dual government could create awkward situations such as when Richard Mulcahy, Minister of Defense in the Dail’s cabinet, had to “arrange” with the “Provisional Government to occupy for them all vacated military and police posts for the purpose of their maintenance and safeguarding”. While Mulcahy did not hold an official position within the Provisional Government, he attended many meetings to organize the country’s defense and deal with the schisming IRA. The British never understood this arrangement but were forced to accept it even though Churchill observed that it was “an anomaly unprecedented in the history of the British Empire” (Charles Townshend, The Republic, pg 386).

Florrie O’Donoghue, a Republican IRA member, described the dual government as a master-stroke by the pro-treaty side. The pro-treaty side used the continued existence of the Dail and Irish republicanism to distract people from the core dispute around the treaty all the while allowing the Provisional Government and National Army to strengthen its political and military power. He claimed that:

“if Dail Eireann had been extinguished by the vote on the Treaty the issue would have been much more clear-cut, and many of the subsequent efforts to maintain unity would have taken a different direction. Despite Republican hopes, time was on the side of the pro-treaty party” - Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green

P. S. O’Hegarty, however, felt that the provisional government was a disaster for the pro-treaty side, revealing a weak government eager to appease an intransigent opposition. Similarly, Griffith warned that a dual government would create chaos. What actually happened was that the Dail existed in name and basically merged with the Provisional Government by the time of the general election in June.

The National Army

The Provisional Government created the National Army on January 21st, 1922, even though legally it wouldn’t be formally recognized by the Irish Free State government until August 1923. The National Army structure was based on the British Army and it employed many men who had served In the British army to help with organization and discipline. However, it used the IRA ranks until January 1923, when they switched to a rank system that utilized by most armies. The National Army got most of its equipment, uniforms, and ammunition from the British Government. Once the treaty was signed the British government was invested in preserving the Provisional government. They even offered to send troops to help curb the civil war. About half of the National Army were half-trained troops thrown into counter-insurgency work. The army would have issues with discipline, human rights violations, and ill-discipline. Many in the National Army had combat experience, but little administration, training, and logistical experience. It wasn’t like the IRA could properly train or equipment their forces during the Irish War of Independence. However, core units, such as the Dublin Guard, proved themselves disciplined and effective military units.

Fionan Lynch and National Army Soldiers

[Image Description: A black and white photo of a group of white soldiers in grey military tunics and pants. They are standing on loose dirt and there is an old fashion truck behind them]

The first core unit of the National Army was the Dublin Guards, who were a mixture of IRA veterans loyal to Collins (many who came from the Squad, Collins’ assassins) and ex-Royal Dublin Fusiliers who are known for their brutality in Co. Kerry. Their commander, Brigadier Paddy Daly, who once served as officer commanding of the Squad, said, “nobody had asked me to take kid gloves to Kerry, so I didn’t.” (Diarmaid Ferriter, Between Two Hells, pg 24).

As the army grew, it relied on men with British army experience such as General W. R. E. Murphy, Major-General Dalton while Lt-General J.J. O’Connell and Major-General John Proust served in the US Army during WWI, which would create problems for Richard Mulcahy and William Cosgrave during and after the civil war.

The Provisional Government knew they couldn’t rely on the army to keep civil order, so they created the Civic Guards to replace the withdrawn British Army and RICs. They played a small roll in the civil war itself except for a mutiny later in 1922, which we’ll talk about in another episode.

Finally, the British withdrew all forces except for 5000 men under General Macready, who was there, Churchill claimed because:

“We shall certainly not be able to withdraw our troops from their present positions until we know that the Irish people are going to stand by the Treaty, neither shall we be able to refrain from stating the consequences which would follow the setting up of a Republic." - Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green

The British either sensing that civil war was imminent or simply being racist and assuming the Irish “couldn’t rule themselves” constantly pestered the Provisional Government to do a better job at governing. While they acknowledged that to interfere in Irish affairs before the Irish Free State was created would only exasperate things, they had no problem threatening the Provisional Government with the return of British forces whenever they didn’t respond as quickly as the British expected.

The British had some right to be concerned as the National Army was weak. It’s estimated that about 70% of the IRA disapproved of the Treaty, while others supported it simply because Collins said to. This left Mulcahy with the difficult task of keeping together a republican army that didn’t respect or acknowledge the powers of the provisional government and felt the Dail was being co-opted. We’ll get into this more in the next episode, but by February 1922, the Provisional Government was facing the unsettling truth that the National Army was in a race with the IRA to claim ownership of the abandoned British barracks and large swaths of the country.

The Provisional Government gained its first victory on January 16th, just two days after it’s creation, when Michael Collins took the keys for Dublin Castle from the British. For centuries Dublin Castle as served as a citadel for British forces and one of the most distinct symbols of British colonial rule. The fact that it was now in Irish hands was maybe the first true sign that Ireland was free of British control. The Times described the moment as follows:

“All Dublin was agog with anticipation. From early morning a dense crowd collected outside the gloomy gates in Dame Street, though from the outside little can be seen of the Castle, and only a few privileged persons were permitted to enter its grim gates… [At half past 1] members of the Provisional Government went in a body to the Castle, where they were received by Lord FitzAlan, the Lord Lieutenant. Mr. Michael Collins produced a copy of the Treaty, on which the acceptance of its provisions by himself and his colleagues was endorsed. The existence and authority of the Provisional Government were then formally and officially acknowledged, and they were informed that the British Government would be immediately communicated with in order that the necessary steps might be taken for the transfer to the Provisional Government of the powers and machinery requisite for the discharge of its duties. The Lord Lieutenant congratulated … expressed the earnest hope that under their auspices the ideal of a happy, free, and prosperous Ireland would be attained… The proceedings were held in private, and lasted for 55 minutes, and at the conclusion the heads of the principal administrative departments were presented to the members of the Provisional Government.” - The Times, 17 January 1922 – Dublin Castle Handed Over, Irish Ministers in London Today, The King’s Message.

Later that day, Collins would issue the following telegram:

“The members of the Provisional Government of Ireland received the surrender of Dublin Castle at 1.45 p.m. today. It is now in the hands of the Irish nation. For the next few days the functions of the existing departments of the institution will be continued without in any way prejudicing future action. Members of the Provisional Government proceed to London immediately to meet the British Cabinet Committee to arrange for the various details of handing over. A statement will be issued by the Provisional Government tomorrow in regard to its intentions and policy." - Michael Collins, Chairman, The Times, 17 January 1922 – Dublin Castle Handed Over, Irish Ministers in London Today, The King’s Message.

As monumental as this victory was, it did little to ease the many issues facing the Provisional Government. They were responsible for

taking the executive from the British

maintaining public order during the transition

drafting a constitution

preparing a general election

preventing a civil war

Win over their furious, anti-treaty colleagues who refused to acknowledge the Provisional Government or the Dail as a legitimate government.

As much shit as the Provisional Government and later the Cosgrave Administration gets (and I will give because wow they make some terrible decisions), I think it can be easy to overlook what they were facing and how overwhelmed they must have been. Many of the members of the Provisional Government had either been violent rebels since 1916 or had been ministers in an illegal ministry risking arrest and death since 1916. They didn’t have any real government experience, they hadn’t dealt with any of their trauma, and the tools that had worked for them for the past few years are not necessarily the best tools when you’re trying to build a nation state.

Kevin O'Higgins

[Image Description: A black and white picture of a white man with a a receding hairline and a high forehead. He is wearing a white button down shirt, a thin tie, and a black suit coat. Behind him is an out of focus tan building and black metal gate.]

Another thing to keep in mind, because this will be an undercurrent to the entire war, is the relationship between the IRA and the IRB and the Dail. In season one, I spent a lot of time analyzing the tension between Cathal Brugha’s civilian ministry of defense and Mulcahy and Collin’s more militant Squad and IRA as well as the limited control GHQ actually had over its own units. This culture of might makes right and violence is ok if Collins says it is, is one of the reasons the civil war occurs and will plague Ireland for a long time. It was up to the Provisional Government to handle this problem, but how can the Provisional Government do that when it’s run by Michael Collins, a bit of a strong man himself who never had issues with assassins, disappearances, and violent solutions to irritating problems.

I find this quote from Kevin O’Higgins as capturing the feeling of the Provisional Government in 1922 both moving and enlightening: The Provisional Government was:

“simply eight young men in the City Hall standing amongst the ruins of one administration, with the foundations of another not yet laid and with wild men screaming through the keyhole” - Diarmund Ferriter, A Nation and Not a Rabble, pg 268

For the anti-treaty side, the acceptance of the treaty and the creation of the Provisional Government was nothing short of the very betrayal of everything they had fought for both in 1916 and during the Irish War of Independence. Worst, the anti-treaty side saw the Provisional Government co-opting the many institutions that were supposed to belong to the “Irish Republic” such as the Dail, Sinn Fein, and the Irish Republic Army. In an attempt to buy time to win over more people to the pro-treaty side and to work a compromise that would prevent civil war, Collins, during a Sinn Fein meeting, delayed the general election from February to June. On one hand, this could be seen as a pragmatic thing to do, especially if he feared he didn’t have the votes to uphold the treaty and he thought he could legitimately find a compromise that would satisfy everyone. However, many anti-treatyites saw this as election rigging. Mary MacSwiney ruefully wrote:

“When Collins saw he had a majority against him…he put up the unity plea to stave off the vote.” - Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green

Many blamed DeValera for agreeing to this compromise. Katheen O’Connell, DeValera’s secretary, wrote of the meeting were the compromise took place:

“The vast majority were Republicans. What a pity a decision wasn’t taken. We could start a new Republican Party clean. Delays are dangerous. Many may change before the Ard-Fheis meets again” - Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green

The thing was that no one wanted a civil war. Collins was desperate to prevent a military conflict and he believed that if he could craft a constitution before the next election, he could prove that the Treaty was only a steppingstone meant to placate the British. The constitution would be closer to a republican ideal. Similarly, DeValera, who even during the Irish War of Independence disliked guerilla warfare, wanted to avoid war. He believed he could use the next three months to win over the Provisional Government and tweak the treaty itself.

February 21, 1922 Sinn Fein meeting

[Image Description: A sepia toned photo of a gathering of mostly white men with a handfuil of white women. They are organized in three rows, the people in the front row are sitting, the people in the second and third row are standing. They are outside, in a park with bare branched trees.]

Sinn Fein fell apart shortly after the treaty was ratified and DeValera created his own party, Cumman na Poblachta. Despite wanting compromise, DeValera went on the offensive as he campaigned for the upcoming general election, claiming, on March 18th, 1922, that the IRA would have to “wade through Irish blood, the blood of the soldiers of the Irish Government, and, perhaps, the blood of some of the members of the Government” to achieve Irish freedom. (Charles Townshend, The Republic, pg 361)

The developing split wasn’t simply a matter of semantics or principles. This was a clear divide between those who were willing to work with what they managed to wrangle from the British and those who wanted to fight until all of their goals were achieved. These goals included complete separation from Britain, a return to a glorified Gaelic past, and an Irish republic, not a parliament that swore its loyalty to a British king. If the Provisional Government saw themselves as the protectors of Ireland’s future, the Anti-Treaty side saw themselves as the protectors of Ireland’s republican past. They draped themselves in the rhetoric and principles of Easter Rising, believed that the Dail under DeValera was the last legitimate government in Ireland, and that they alone had Ireland’s true interests as heart.

I want to save the in depth discussion about the IRA’s feelings for the next episode, where we talk about the taking of barracks and the army convention, but the army’s growing disgruntlement and anger with everything political, its disrespect for the Dail and GHQ, and its firm belief it “won” the war and thus had a right to determine Ireland’s future, also played a huge role in sparking the civil war. The Irish Civil War was both a legitimate political argument but also a huge army mutiny.

In his magnificent book, Vivid Faces, R. F. Foster explains the treaty split in class terms. He writes that one can see the Irish Civil War as a long brewing divide between those who were influenced by Catholic piety and social conservatism and pragmaticism against those who were ardently revolutionary and radical and socialist. Liam Mellows argued that:

“We do not seek to make this country a materially great country at the expense of its honour. We would rather have this country poor and indigent, we would rather have the people of Ireland eking out a poor existence on the soil, as long as they possessed their souls, their minds, their honour” - R. F Foster, Vivid Faces, pg 282

Liam Mellows

[Image Description: A black and white photos of a white man with curly blonde hair that is shaped upwards. He has a faint mustache. He is wearing a white, collared, button down shirt with a black tie and a black suit. The wall behind him is grey]

This sounds great on paper, but how do you sell that to a people who have been colonized, gone through a world war, and spent the last few years in a guerilla war? Ireland had been economically, physically, socially, and culturally brutalized during the Irish War for Independence and it makes sense that while some people would want to fight until everything they desired was achieved, others simply wanted a break and a chance to recover and heal. But even healing was a matter of contention because what did healing really mean when you still had to take an oath of loyalty to your colonizer? When your national army is being armed by your former oppressor so you can fire on the disgruntled members of your own society? When your island is split in two and the only way to unite it is still through violent intervention? When so many of the heady promises made during the revolutionary period are put aside for more practical concerns?

I would add that there is something that happens when people are presented with the opportunity to form a state. We saw this in our Season 2, Central Asia during the Russian Civil War. The minute the Jadids, Alash Orda, Soviets, and others were given the chance to form their own definition of their boundaries and identities, is the moment we see this idea of “us” vs “them” and the “other” form as well as the concept of elites who control political and economic power.The Treaty shifted the debate that was occurring in Ireland during the Irish War for Independence. No longer were the IRA fighting a guerrilla war that they could lose at any moment and they needed lofty ideals such as a Republic and a Free Gaelic Ireland. Or an Ireland cleansed of all British influence. The Treaty gave the people of Ireland a real tangible chance to build something and that changed a lot of desires, hopes, and plans for a lot of people.

Mary MacSwiney

[Image Description: A black and white picture of a white woman wearing a simple, black, long sleeved dress. Her wavy, brown hair is pulled back into a bun. Behind her is a grey wall]

The anti-treaty side were not wild people who wanted to destroy simply to destroy. The split tore them apart. Many simply couldn’t understand how their comrades could give up on their republican dreams so easily. Many anti-treatyites wrote to their pro-treaty friends, begging them to support the Republic. Mary MacSwiney, one of the most vehemently anti-treaty women, wrote to none other than Richard Mulcahy, claiming:

“No matter what good things are in the Treaty, are they worth all this unhappiness, Dick? Do you not realize we hold the Republic as a living faith – a spiritual reality stronger than any material benefits you can offer – cannot give it up. It is not we who have changed it is you.” - R. F. Foster, Vivid Faces, pg 280

Formerly close family members found themselves bitterest of enemies. For example, the Ryans family found themselves torn apart as Min, Mulcahy’s wife, along with Agnes and Denis McCullough supported the treaty, while their siblings Phyllis, Chris, Nell, and James and Mary Kate were against it. Some would spend time in jail and even go on hunger strike while Mulcahy was minister of defense. He would refuse to release them or give into their demands during the war. Phyllis at one point told Min to leave Mulcahy, but Min refused.

The treaty nearly ruined Mabel and Desmond Fitzgerald’s marriage and shattered friendships, the most famous being Michael Collins and Harry Boland. Others, like Liam Lynch, bent themselves into pretzels trying to find a way to avoid a split. Both sides appealed to the Catholic Church to support their side as they grew closer and closer to war.

Others couldn’t find it in themselves to blame their comrades and turned their anger on the British, Protestants, and the “other”. Muriel MacSwiney, wife to Terence, wrote to Mulcahy, stating:

“I don’t feel anything against anybody but England for what has happened…Although I think this treaty is by a long way the greatest infamy that the enemy has ever perpetrated on us & I will always oppose it or anything like it I feel nothing against any Irishman; the whole weight of my venom is directed against the English people…I shall spend my life not, as up to this, working for the complete independence of Ireland’s Republic, but also working for the destruction & downfall of England & of every single English person I come across. The English people are to me now a plague of moral lepers. - R. F. Foster, Vivid Faces, pg. 280

Finally, I would argue that trauma played a huge role in the split. You simply can’t take a majority of young men and women who have spent the last few years fighting to survive and tell them use this new political process to register your disagreements with this government that we’re building on the fly. The sense of betrayal – on both sides – was very real and very vivid and there wasn’t any mechanism to deal with it.

For the Provisional Government, they couldn’t believe their comrades were willing to risk their very state over something as “miniscule” as an oath. The hatred of the treaty and the government that would follow must have also felt quite personal since so many former members of DeValera’s government transferred to the Provisional Government. All of a sudden they weren’t trusted to lead Ireland into a liberated future.

For the anti-treaty, apparently everything they fought for was a lie and the comrades they thought they could trust were traitors to the very idea of an Irish Republic. Old, festering personal clashes rose to the surface with sudden ferocity, because the treaty released the pressure of war.

All these the differences and issues that had been developed during the Irish War of Independence could be ignored as long as survival was paramount. But now that the war was over, the pressure that kept all that shit down, was gone, and the world isn’t better. In fact, it looks like it’s either going to be more of the same or a compromised reality which doesn’t really justify all the shit you went through to get to this point.

It’s like when you’re working on your own trauma and you dive really deep and you accidentally ram into a deep, dark trauma and now it’s out and all these emotions your brain was protecting you from, rises to the surface and so now you’re a swirl tornado of emotions with no tools to handle it and nothing seems to help. The biggest tragedy is that both sides tried so hard to avoid war, but it wasn’t enough. The sense of betrayal was too strong and the promised achievements of the treaty were too minuscule.

References

The Republic by Charles Townshend

Between Two Hells by Diarmaid Ferriter

Vivid Faces by R. F. Foster

Irish Civil War 1922-23 by Peter Cottrell

Richard Mulcahy: From the Politics of War to the Politics of Peace, 1913-1924 by Padraig O Caoimh

Eamon De Valera: a Will to Power by Ronan Fanning

Green Against Green by Michael Hopkinson

#irish history#irish civil war#anglo-irish treaty#michael collins#richard mulcahy#eamon devalera#Kevin O'Higgins#W. T. Cosgrave#queer historian#queer podcaster#Spotify

0 notes

Text

"I've seen suffering in the darkness. Yet I have seen beauty thrive in the most fragile of places." - History, Culture and Identity in Cartoon Saloon's Irish Mythology Trilogy

Written accounts of Irish history and culture only begin to appear from the 5th century onwards and what came before we are left to piece together from archaeological remains whose meanings and motivations we can only guess at. What is clear, though, is that during that broad stretch of time between the Early Mesolithic and Late Iron Age, a distinctly Irish identity had been established and cultivated through by the craftsmen, artists, hunters, foragers, farmers and warriors that populated the country through their housing, weaponry, metalworks and stone monuments. The development of the Christian church throughout the Early Medieval period brought its own beauty to the art and architecture of the country, but also adapted its culture to suit the needs of an integrating religion and sites and ceremonies of pagan worship were amalgamated into the Christian calendar. Following this were Viking raids, Anglo-Norman settlement, English conquest, plantation, oppression, rebellion, famine and civil war. From the Early Medieval period to the present day Ireland has experienced an almost constant shift in leadership and identity with little time in between for the dust to settle. Culturally, a "Celtic Revival" in the late 19th and early 20th centuries sought to re-invigorate the arts and history of Celtic Ireland (a broad, problematic concept in itself) as an expression of nationalism and to bolster a distinctly Irish artistic and literary identity. All of this is to say that wading through Ireland's history of social upheaval, religious and political conflict, and loss and confusion of identity is no mean feat. To take those threads and conjure up original stories for modern audiences, embracing the suffering and celebrating the beauty, is impressive. To do it three times is witchcraft.

In their films depicting Irish history, culture and mythology, animation studio Cartoon Saloon have approached their stories with a respect for the past, both fact and fiction. By evoking the artwork, legends and real history of Ireland's past and combining it with their own fresh, unique visual style, Cartoon Saloon brings some much needed authenticity and vibrancy to the depiction of Ireland in mainstream culture. Absent are the twee figures of backwards island folk or the commercialised idolatry of a St. Patrick's Day parade. What we get instead is something more personal, recognisable on the surface to every child and adult who learned about Fionn, the Fianna and fairy circles in primary school and with nuggets of information and visual cues for explorers of Ireland's broader history.

"I can't tell you which parts of this story are true and which parts are shrouded by the mists." - The Secret of Kells and the line between history and mythology

Set roughly in the 9th century AD The Secret of Kells is the earliest depiction of Irish culture in the trilogy. This period saw the introduction of Christianity and the eventual integration of the religion among the native Irish, a relatively smooth transition when compared to later events as noted by historian Jo Kerrigan: "And so the people of Ireland combined the new ways with the old…not bothering too much that the names had changed." Although the main character, Brendan, comes from a Christian monastery and carries those beliefs, The Secret of Kells does well to capture this balance between a new religion and old beliefs with the inclusion of Aisling and Crom Cruach, and without dismissing them as a childish or archaic. "Pagans. Crom worshippers. It is with the strength of our walls that they will come to trust the strength of our faith." The threat of Viking raids is what spurs Abbot Ceallach's desire to build a wall around his monastery, but, underlying his actions is another aspect of a monk's work - converting the natives. In The Secret of Kells the abbot's wall not only protects them from invaders but cuts them off from the forest beyond - the domain of shape-shifters, wild animals and pagan temples, a world that Brendan can only glimpse through a crack in the wall. A staple of the entire trilogy is this depiction of wilderness in some form and its association with Ireland's symbolic wilderness and pagan ancestry. When Brendan enters the forest for the first time it is dark and frightening until Aisling, an ethereal Sídhe figure who can shape-shift into a wolf, shows him how to navigate it. Brendan's fear is eliminated and Aisling quickly becomes his friend, each amused and fascinated by the other.

Hidden throughout Brendan's trek in the forest are old, moss covered ogham stones and stone circles, allusions to native practices, but deeper in, the colour palette changes from bright greens and natural browns to a wash of dark greys and black when Brendan stumbles across a temple to Crom Cruach (a deity who, in Irish mythology, is eventually destroyed by St. Patrick). Aisling tries to warn him away, "It is the cave of the Dark One," but Brendan dismisses her worries, "The abbot says that's all pagan nonsense, there's no such thing as Crom Cruach." At the sounding of the deity's name, black tendrils emit from the cave and pull on Aisling as she stops them reaching Brendan. Later, Brendan returns to the cave to steal Crom's eye - a magnifying crystal that will help Brendan and Brother Aidan with their illumination. In a beautifully animated sequence Brendan battles Crom Cruach in his cave by trapping him in a chalk circle and stealing his eye. Crom Cruach is depicted as a never-ending snake (in a geometric pattern reminscent of both pre-Christian art and the knotwork of Christian manuscripts) possibly in reference to the 'snakes' (demons) banished from Ireland by St. Patrick. What's most fascinating about this sequence is that Brendan experiences it at all. Although the experience is supernatural it is never implied as anything other than real. Brendan is a committed monk in training who will spend his life in service to the monastery and creating the Book of Kells; even after meeting Aisling and battling Crom Cruach he never questions his faith or his elders and when he returns to the monastery with the eye no one disputes the story of how he came by it, "You entered one of the Dark One's caves?" At this time, at the edge of a growing monastery and with a direct reference to the abbot's desire to convert the natives, there is still space for pagan ideas to exist. Whenever Brendan is punished by Abbot Ceallach it is for disobedience not a lack of faith. Similarly, Aisling using Pangur Bán's spirit to free Brendan has an effect on the real world. There's an argument to be made that this is a film and anything can happen, but for problems to be solved by magic, the way Aisling frees Brendan, firm world-building rules must be established; in this world, 9th century Ireland, spaces exist in which otherworldly figures reside and actions beyond the mortal realm occur and these spaces exist alongside this film's version of civilisation, the monastery.

"I have lived through all the ages, through the eyes of salmon, deer and wolf." As an animated feature, there is a lot the film can tell us through visuals alone, and The Secret of Kells does a wonderful job capturing an Ireland in transition. The prologue opens with a close-up image of the Eye of Crom with abstract shapes swimming around it, followed by a glimpse of Aisling hiding in a tree as she narrates over these images in an eery whisper. Following these we see a salmon, deer and wolf, three animals important to Irish mythology, identity and history; the salmon, related to The Salmon of Knowledge, represents mythology, the deer is the national animal of Ireland, and wolves (in the world of Cartoon Saloon) represent its wildernes and history (the elimination of the wolf population became more active in Ireland during times of English occupancy, a theme that is explored more deeply in Wolfwalkers). Even the waves crashing around Iona as Brother Aidan escapes morph into wolves, futhering their symbolism as something wild and dangerous, yet they are never associated with the Viking raiders; the wilderness is as equally affected by change as the people are. The monastery is littered with Iron Age motifs existing alongside Early Christian imagery. Spiral motifs occur in trees and plants, in the ropes that bind the wall's scaffolding together, and circular, semi-circular and zig-zag shapes continue to appear with knot-work patterns and religious figures - even the snowflakes during the raid are strands of knot-work. The monastery itself is accurate to the period with its round tower, beehive shaped structures (called clochán) and the town growing around it, while outside its walls Brendan crosses a stone circle. We even see a game of hurling, the ultimate unifying bridge between pagan and modern Ireland. The walls of the abbot's cell are covered in his own drawings of plans for the monastery's construction. These are exquisitely detailed and clearly a plan for the future but drawn in a style that cannot escape the past; zig-zags, spirals, circles, semi-circles, dots, triangles, sun and star motifs and something that looks like an alignment chart. The style is evocative of the insular La Tène that preceded the arrival of the monks in Ireland; a combination of abstract and geometric, seemingly random, but clearly symbolising something greater.

"You must bring the book to the people." In their last interaction as children Aisling helps Brendan recover the pages of his manuscript as he flees the Vikings. In this gesture Aisling aids Brendan on his religious journey - during the montage later on she even guides him home. Faith never comes between these two, their relationship is one of mutual curiosity and sharing their differences. In Irish mythology, female figures (particularly shape-shifting ones) are often symbolic of Ireland itself and to have the support of these figures is, for kings and heroes, a mark of validation. At this time, these two worlds still live alongside each other and Aisling is allowed to support Brendan's work as a monk while maintaining her own natural way of life. Although Brendan's final journey home shows the spread of Christianity across the country we get one final image of Aisling, changed to her human form in a flash of lightning, that shows us she hasn't disappeared just yet. Brendan, now an adult, returns to Kells and although Abbot Ceallach is old and sick, the monastery stands strong and Brendan brings with him the completed Book of Kells, ready to continue the abbot's work.

"This wild land must be civilised" - Wolfwalkers and the taming of Ireland

Set in 1650, Wolfwalkers occurs roughly 800 years after The Secret of Kells and presents a vastly different universe. The monks' Christianisation of the natives was a far more gentle affair and one founded in a desire to educate people. Ireland under the Lord Ruler (a stand-in for Oliver Cromwell) is a world of service, punishment and fear. By chopping down trees and employing hunters to cull the wolf population the Lord Ruler is attempting to 'tame' the countryside and, most importantly, the people themselves. References to "the old king" and "revolt in the south" place us, historically and politically, in the Cromwellian Conquest, when Cromwell was sent to Ireland to quell uprisings against the newly established English Commonwealth. Heavy stuff and this is a simplification of a period of major conflict in Ireland but Wolfwalkers impresses on us the feeling of living under the thumb of an active oppressor on a much smaller, more personal scale. The Lord Ruler wants the people of Kilkenny afraid and complacent so that they support his efforts to cull the wolves and cut down their forests. Although the wolves pose no threat to the city, people have been made to fear them, resilting in the loss of their connection to the forest outside the town walls. Any reference to a world ouside of the current mode of conduct is cause for immediate punishment and suppression. Even Bill and Robyn, loyal English citizens, are punished. When one of the woodcutters talks of "pagan nonsense" he is confined to the stocks and Robyn is forced to work as a maid in the castle when she does the same. When Bill fails to cull the wolf population (and control his own daughter) he is stripped of his rank as hunter and forced into the role of soldier, robbed of the little freedom he had.

"This once wild creature is now tamed, obedient, a mere faithful servant." Although this line is spoken in reference to Moll, held captive in a cage in her wolf form, it is the human characters who suffer the most from this ideology - even the nameless background characters are confined to the walls of the city. What comes to mind when hearing this line is Robyn in her maid's uniform, once lively and imaginative, now returning home with lines under her eyes after a long day of hard, monotonous work, and Bill, shackled at the neck and forced to march behind the Lord Ruler's horse ("we must do what the Lord Ruler commands"). Although Moll is held captive too, it is in the form of a humongous wolf; she is locked away in the Long Hall for fear of the danger she represents because the Lord Ruler is aware of how poweful she is and so he must keep her locked up to show the people of Kilkenny just how much control he can wield, quelling any potential notions of power they might have held in themselves. In the case of Moll, Robyn and Bill, each time they are held captive by the Lord Ruler their captured bodies submit to the wolf form to escape: Moll uses its strength to break free of her chains, Robyn leaves behind her human body to launch an attack against the soldiers with the rest of the pack, and Bill, who had no idea what being bitten by Moll would do to him, submits to a primal instinct within him to protect his daughter and attacks the Lord Ruler. The Wolfwalkers are able to draw on this power but the people left behind in Kilkenny have no such escape.

"What cannot be tamed, must be destroyed." The ending of Wolfwalkers is bittersweet. Robyn, Médb and their parents are safe after defeating the Lord Ruler and his soldiers and ride off, not quite into the sunset, but onto horizons new. "All is well," Bill and Robyn tell each other and the family appear content, but, before now, leaving the forest was not on the agenda; leaving the forest meant retreating from a threat, as Moll desperately wanted Médb to do, and this is still the case. Médb wanted to save the forest, but, after everything that's happened, the family are no longer safe on the borders of the town. Robyn, Médb, Bill and Moll all save each other but they can't save their home and their retreat from Kilkenny is just that - a retreat. The Lord Ruler may have been killed but that doesn't mean the end of his conquest. Historically, this period saw Ireland amalgamated into the Commonwealth and Irish Catholic landowners ousted by English colonists, as well as a high level of deforestation and the elimination of the wolf population. By having the family leave their home, together and with a bright sky and grassy hills ahead of them, Wolfwalkers' coda balances the narrative conventions of a story by giving the viewers their satisfying ending without sanistising the history it's based on.

"Remember me in your stories and in your songs" - Song of the Sea and loss:

If Wolfwalkers is the taming of Ireland then Song of the Sea is Ireland tamed. Set roughly in the 1980s it is the closest depiction of a modern Ireland in Cartoon Saloon's ouevre. In contrast to The Secret of Kells and Wolfwalkers, which represented Ireland's native identity in the forest, here it takes the form of (drumroll) the sea, but while those other films depicted the battle between the wilderness and civilisation Song of the Sea depicts its defeat. The last of the Sídhe live in hiding in a rath disguised as the centre of a roundabout and use a sewage system to get around. In their diminshed forms, Lug, Mossy and Spud also resemble more closely what we might think of as 'fairies' in Ireland today, not the imposing figures of mischief and chaos the Sídhe really are in mythology. Still, Lug, Spud and Mossy wear torcs, brooches and earrings of gold and strewn about their home are ogham stones and hurls; in a nice marriage of modern and ancient tradition, they play the bodhrán, fiddle and banjo, singing a version of the Irish language song 'Dúlamán'. Only in this one pocket in the middle of the city do different aspects of traditional Irish culture survive.

All throughout Song of the Sea we see iconography of modern Ireland. Conor drinks a pint of Guinness (unlabelled but unmistakable), the front of the pub he sits in is decorated in proto-typical Irish pub fashion. On the wall in Granny's house sits proudly a picture of Jesus with the Sacred Heart lamp as she warbles along to the classic Irish children's song, 'Báidín Fheilimí'. Ben and Saoirse take refuge in a shrine to a holy well with a rag tree outside that is bursting with religious iconography as well as a toy sheep. Symbols that are as much a part of the national identity as those pre-historic and mythological ones. There are also references to the assimilation of pop culture outside of Ireland in a Lyle's Golden Syrup tin, the Rolling Stones poster on Conor's old bedroom door and Ben's 3-D glasses and cape, an emulation of a superhero costume. These images are, ultimately, harmless but have overtaken their native counterparts. Although we see statues of the Sídhe in the background, these are not shrines but detritus, and they lie forgotten, covered in plants and moss, in the company of bags of rubbish and old televisions. The diminishing of one era of Ireland's history to make way for a newer more powerful and modern identity is just one kind of loss that is portrayed in Song of the Sea, but each character experiences their own version throughout. The loss of Bronach that has affected Ben and Conor; the potential loss of Saoirse as she grows sicker; the loss of Mac Lir that drove Macha to such despair she literally bottled her emotions and those of others until they turned to stone. All of this comes to a climax at the end of the film when these tragedies are laid bare. As in Wolfwalkers the greater connotations of this theme are presented on a smaller scale: Ben and Conor's pain by the loss of Bronach.

Ben and Conor are representative of the human world and so suffer her absence more visibly than Saoirse who approaches her mother's world with curiosity and ease. In contrast, Ben, although he misses Bronach, rejects the sea (her home and symbolic identity) and his sister, a physical as well as spiritual reminder of what's been taken away from him. He turns his back on his past as much as he mourns its loss. We see it less obviously in Conor who wallows in his own memories and grief and tunes out Ben's references to his mother "It's as though I've been asleep all these years. I'm so sorry." Ben's grief is more expressive compared to the inwardly focused Conor and even towards the end of the film when Ben is trying to help Saoirse, Conor brushes over his insistence that only her selkie coat can save her. It's only when Saoirse is finally wearing the coat and wakes up from her sickness that he finally engages with Ben on the subject of Bronach, "She's a selkie, isn't she? Like Mam." "Yeah." (Which looks like a weak conversation written down but it's the happy smile on his face and the emotion in his voice that give the single word weight). "Please don't take her from us." During the film's final sequence, when Saoirse sings her song and wakens the sleeping Sídhe, Bronach returns but only to take Saoirse away. With tears in her eyes she begins to lead Saoirse along until Ben and Conor stop her, not forcefully but pleadingly, "she's all we have." All they have is Saoirse, all they have is a thread connecting them to Bronach's world and their memories of her.

"All of my kind must leave tonight…" As the Sídhe are wakened by Saoirse's song we watch them rise joyfully to form a glowing processional in the sky as they make the journey across the sea to their home. This scene is so beautifully animated and so filled with a sense of magic and wonder that we are charmed into believing this is a good thing. The Sídhe are returned to their noble forms and going to their home "across the sea"; they fill the sky with a warm, mystical light, but they are taking that light and their magic with them. As Bronach quotes in the film's prologue, "Come away, o human child, to the waters and the wild, with a fairy, hand in hand, for the world's more full of weeping than you can understand." This is a world that can no longer bear the force of two identities. Unlike The Secret of Kells where Brendan and Aisling were allowed to live alongside each other without compromising their beliefs or ways of living, Bronach, a spiritual being, is forced to leave, while Ben and Conor have no choice but to stay and Saoirse, who walks both worlds, is made to choose between them. Although this is a happy ending it is still being depicted on a personal level. On a grander scale, the country has lost something that isn't coming back and this is depicted as a relief for the ones leaving it behind. On the other hand, Saoirse's decision to remain shows that, in small pockets of the country, the magic remains.

It is fitting that Song of the Sea, as a representation of modern Ireland, draws on loss; Ireland has been experiencing loss on a grand scale for centuries. Although the march of progress is mostly positive, in some cases it has altered our respect and interest in the past. Today there is a nihilism attached to Irish heritage; the spirituality that is associated with airy fairy hippies dancing naked in a moonlit field; the language that is almost universally despised by every secondary student forced to grapple with the Tuiseal Ginideach; its disappearing and continually exploited ecological landscapes; traditions and tales that grow more twee and archaic with every tourist bus that passes by; the preservation of archaeological sites in frequent battle with the progress of industry. In the interest of leaving behind the worst of our past we are at risk of losing the best. The writer Manchán Mangan suggests that this desire to forget lies in the pain we feel when we consider our history. Some, like Conor, try to push all reference to this pain out of their lives, others, like Ben, divert their pain into misplaced anger. Mangan cites the Famine as a source of generational pain and its effect today on our use of the language, but really it can be attached to many events and periods of time, "English was the future; Irish would only bring suffering and death." This is a sentiment that carries through to this day; despite encouragement from schools, local councils and the government, Irish remains a least favourite subject for most people who dismiss it as unuseful for success in the wider world. By proxy, anything to do with the notion of "Irish", the language, history and culture, is old-fashioned (suffering and death) while success and the future lie outside of the country. Mangan goes on to suggest that only by confronting the pain of our past can we unlock an ability in ourselves to engage more fully with our identity, "We might stop blaming our failure to learn on teachers, or the education system, or Government policy, and realise that we have no difficulty learning any other subject…" Ben and Conor are given the opportunity to say goodbye to Bronach before she leaves, allowing them to carry on with their memories of her and the last strand of their connection to her as represented by Saoirse. More and more people today are looking to Ireland's past, ecology and language for whatever it is they need or want to find. It isn't necessary to convert to paganism and live on the shores of the Connemara coastline to achieve this connection, but actively disengaging from your past can only hurt more than it can help. In their respective stories Brendan does not compromise his beliefs but still builds a friendship with Aisling, while Robyn and Bill integrate fully into Médb and Moll's world. There is no right way to engage with this side of our history and identity, but in contrast to Ben and Conor, Brendan and Robyn have balanced and fulfilling relationships with their native counterparts - the threats to their world come from outside sources. Ben and Conor were stuck in their pain over Bronach's loss and it is only after getting to see her one last time that helped them to move on and heal. Conor tells Bronach that he still loves her, he will carry his love and memories of her forever; Ben lets Saoirse into his life and is able to move past his grief and fears of the sea. Here, the threat of loss and destruction in modern Ireland comes from within, and can only be treated by engaging with the past - its rich heritage and tragic history - and moving on with all of the wisdom and experience it provides.

#another late post because my laptop charger broke#cartoon saloon#the secret of kells#song of the sea#wolfwalkers#irish mythology#irish movies#animated movies#animated films#animation#essays#film analysis#movie analysis#i do go on and on don't i

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

the war of the roses - a snippet

sirius black/severus snape explicit

here’s a wee look at the next chapter of the war of the roses to tide you over before the weekend...

featuring tonks being a bonafide baddie with a terrible taste in men, sirius moping [as per], and me shoehorning in my "everything in the series connects to contemporary anglo-irish history" agenda....

Tonks has a black eye (courtesy of Augustus Rookwood) and a grey complexion (courtesy of being dragged back to work weeks earlier than she should have been). She looks exhausted. She’s lost weight. She has dark circles under her eyes and hollows under her cheekbones and he finds it almost terrifying to look directly at her.

Not because growing thinner has made it all the clearer how much she looks like Bella - he knew that; he can handle that - but because her specific brand of wan and worn-out looks so much like the one he remembers his mother putting on during his childhood - a cloak of pale skin and mourning robes and staring at the woven roses on the rug and not leaving the house - and never taking off.

Only the fact that her hair is electric blue and her aura opalescent and her appetite undiminished quells the shiver working its way down his spine, stopping him from panicking that there’s been some rip in time and the old bitch isn’t dead anymore.

‘- started quacking like a duck,’ she says, cheeks bulging out like a hamster’s with pasta bake, her luminescence - a gemstone sheen that no Death Eater’s curse could rob from her - so magnificent that even Molly smiles indulgently at her lack of table manners.

(Sirius wonders how long it took Andy - she was hardly as much of a prig as Cissy, but she’d nonetheless never gone in for eating like she lived in a pig-sty - to give up on trying to drum some decorum into her.)

‘The Muggles all thought he’d lost his gobstones - obviously - but the portrait in the PM’s office alerted the Accidents and Catastrophes lot just before they could cart him off to see one of their - oh bollocks, what do they call them? Y’know - the healers for the mind?’

‘Sike-trists,’ says Kingsley.

‘That’s the word I was looking for!’ she squeals, waving her fork in his direction with transparent glee. ‘I was going to say “suck-tits”, but I knew that wasn’t right…’

Kingsley chuckles. Moony chokes on his beer.

And Tonks stares at him, her dark eyes - Bella’s eyes; his mother’s eyes - gleaming, the dancing flames from the fireplace reflected within them. She looks thrilled, triumphant. Like making Moony shed his stiffness - the meek and restrained act he’s been perfecting since he was eleven - and reveal himself to be capable of spontaneity, of looking dishevelled and coming undone, was her goal.

Moony blushes. Tonks waggles her eyebrows extravagantly at him and then collapses into giggles.

(Sirius wonders what Andy would say. There’s no way she hasn’t warned her daughter to beware the hungry glint which lurks in wolfish eyes, betraying the monster which coils beneath an affable, moderate veneer, ready to strike. After all, she’d seen a similar heart-shaped face staring rapt and worshipping.)

‘It’s no laughing matter, Tonks,’ says Arthur, sternly, gamely diving into the fire which seems to have sprung up around her and Moony. ‘We’re very lucky that Herbert Chorley had a bad reaction to the Imperius Curse… If it had taken, the Prime Minister would be dead.’

Tonks doesn’t look remotely chagrined.

(Sirius wonders if Andy would say that passion’s flame - no matter how dangerous; no matter how quickly it burns itself out - is better than the alternative. He remembers his mother and father, drifting past each other on the stairs like ships in the night. He remembers Bella sitting awkwardly beside her new husband at her wedding breakfast, and how he and Reg had spent the next seven years - until he’d fled, for Godric’s Hollow and its fields of golden wheat - convinced that Rodolphus was genuinely incapable of smiling.)

But Kingsley is possessed by the spirit of irritation at government incompetence which all civil servants must indulge. ‘The worst thing is,’ he spits, ‘we didn’t have a fucking clue the Prime Minister was at risk until this Imperius was buggered up. It doesn’t seem to have occurred to anyone that they might not confine their attacks on Muggles to this shit with the giants… Scrimgeour told me that I’m going to be the first ever liaison we’ve had in the Muggle government. The fucking first! Voldemort probably has dozens!’

‘Why would he bother with all that, though?’ asks Tonks, still shovelling food into her mouth. ‘He wouldn’t get any credit for offing the PM. The Muggles would just blame it on their own terrorists.’

‘Exactly,’ says Arthur. ‘The Muggles would blame their own terrorists, which would give You-Know-Who the cover to keep attacking them on the pretence that the terror threat was escalating, which would involve him doing more and more magic in plain sight, which would keep the Ministry busy scrambling to cover everything up.’

‘And it hurts the Ministry’s standing with the Muggles,’ says Kingsley. ‘The relationship between the Minister and the PM is sold to them on the basis that we don’t affect their affairs in any way. We’re on thin ice with them as it is - the PM took a lot of shit about rising crime rates in February, after the breakout from Azkaban; it’s hit his polling hard - and I guarantee Voldemort knows it. It’s why he’s going after Muggle targets in the way he is. If the PM stops talking to the Minister, because he’s pissed off that he’s having to look unpopular for things which are our fault, then the Death Eaters have a clear run at creating chaos in the Muggle world.’ He picks up his fork again, jabs it with an irritated stab into a piece of pasta. ‘D’you remember in the last war, Arthur, that massacre in Belfast -’

‘- where he had all the Death Eaters dress up like Muggle soldiers. Of course I do. The Prime Minister was furious. There were genuinely worries he was going to renege on the terms of the Statute of Secrecy. We were working overtime for months to sort it all out.’

‘It killed Eugenia Jenkins’ career.’

‘I remember that Mad-Eye used to be convinced that it was Voldemort who got Mountbatten,’ says Moony, his gaze still fixed on Tonks.

‘I’m pretty sure Mad-Eye’s still convinced of that,’ mutters Kingsley.

‘Yeah,’ says Tonks, with a roll of her eyes, ‘but since Mad-Eye’s also convinced that You-Know-Who stopped the Kestrels winning the league in ‘79, I take everything he says with a pinch of salt.’

Everyone laughs, dragged back to levity by her refusal to take anything too seriously. She’s basking in it - their adulation - being cocky and cheeky, so sure that nothing truly evil hides in the lengthening shadows on the other side of the walls that they can almost believe she might be onto something, and let themselves forget the slog which grinds them down and makes exhausted bodies - horses fit for the knacker’s yard - out of young men.

She doesn’t realise that her swagger makes her susceptible, Sirius thinks. She hasn’t noticed that her eyes are glassy with something which could be fever, as she watches Moony watching her, neither of them pretending he isn’t. Sirius has never seen him so overt in his desire, so unwilling to merely pine from afar.

He wonders if something lupine in him has caught the scent of easy prey.

She takes a swig of beer, lips lingering for just a little longer than necessary around the bottle-top when she draws it away.

‘Scrimgeour’s putting liaisons everywhere,’ she says. ‘Ankunda’s going to be guarding Tony Blair. I asked if I could get the gig protecting Princess Diana.’

‘And did you?’ Moony asks. A purr has come into his voice, something low and sultry, like the embers of a fire.

Tonks chuckles. ‘Nah. Scrimgeour thinks that it wouldn’t do to have me pictured near her.’ She gestures at her hair. ‘Says it might ruin her mystique… It’s gone to Savage. He reckons he’s going to have a crack at her.’

‘Poor woman.’

‘Oh, I dunno.’ She winks at him. ‘She’s done worse.’

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

13 books!

What’s up readers?! How about a little show and tell? Answer these 13 questions, tag 13 lucky readers and if you’re feeling extra bookish add a shelfie! Let’s Go!

(I was tagged by the kind @glueblade, thanks for sending the ask!)

1) The Last book I read:

The Lost Metal, by Brandon Sanderson

2) A book I recommend:

I really enjoyed The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller!

3) A book that I couldn’t put down:

It's a clichéed response, but Gideon the Ninth by Tamsyn Muir. Damn but I loved Gideon (the character) from the start and I wanted to know more about her.

Also Monstrous Regiment by Terry Pratchett. My favourite of his so far!

4) A book I’ve read twice (or more):

Do mangas count? Because I've read the Fullmetal Alchemist series by Hiromu Arakawa quite a number of times lol

5) A book on my TBR:

The rest of the Murderbot Diaries by Martha Wells. I only read the first novella so far, and I'm hooked!

6) A book I’ve put down:

I tried to read The Well of Time a couple of times, and I've never quite managed. I don't know why it just doesn't click with me.

7) A book on my wish list:

God, so many. I'd be curious to read anything by R. F. Kuang, like the Poppy Wars series and Babel.

8) A favorite book from childhood:

I was a big fan of the Bartimaeus series by Jonathan Shroud. Barty is still one of my favourite narrators ever.

9) A book you would give to a friend:

I have the tendency to lend my books to my friends, does it count? For one, I got two of them hooked on the Stormlight Archive series by Brandon Sanderson that way. I have a friend who would really like Uprooted by Naomi Novik too, but I haven't had the occasion to lend it to her yet!

11) A nonfiction book you own:

I like reading history books these days! So I have a few of Martin Wall's books about Anglo-Saxon history, and couple of books about the Viking age and the Roman era too.

12) What are you currently reading:

Artificial Condition, bu Martha Wells, and Irish History by Neil Hegarty.

13) What are you planning on reading next?

Feet of Clay by Terry Pratchett. And a lot, lot more lol...

I tag... @baepsae-7, @andordean, @mass-convergence, @kelenloth, @ramblesanddragons and anyone who would want to try! But no pressure if you don't have the time!

22 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stances of IRA divisions on the Anglo-Irish treaty, which ended the Irish War of Independence.

by oglach:

For background, what made the treaty so controversial was the fact that it gave Ireland partial independence as a dominion (akin to Canada at the time), where politicians still had to swear loyalty to the crown. As well as effectively guaranteeing the partition of the island, and the creation of Northern Ireland.

Many within the IRA rejected these compromises and wanted to keep fighting for complete freedom, causing a civil war between pro-treaty and anti-factions. This was eventually won by the pro-treaty side with British support, with the pro-treaty IRA going on to become the new Irish military.

The anti-treaty faction was driven underground, but continued to wage a low-level insurgency against both Britain and the new Irish government until the 60s, when they split again into communist and nationalist factions. The latter of which became known as the Provisional IRA, and obviously experienced a huge "revival" during the Troubles.

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Three Garridebs

Originally published in 1925 and part of the 1927 Case-Book collection.

Refusals of honours are fairly common in Britain - some find the whole thing silly, some these days object to being in something called the "Order of the British Empire", some have political disagreements and others may hold out for something higher.

The South African War refers to the Second Boer War. This is going to get its own post at a later date.

"Britisher" was a contemporary term for British people; most people now use "Brit".

The "wheat pit" in Chicago refers to the Chicago Board of Trade Building, where wheat futures were traded. The building on the site was demolished in 1929 due to structural issues and replaced by the 1930 Art Deco building still on the site today.

Tyburn Tree refers to the former public execution site at Tyburn, near where Marble Arch is located today, which had a three-legged triangular gallows used for mass executions. The last execution was carried out there in 1783, before executions moved to Newgate Prison, now the site of the Old Bailey. A plaque marks the location.

Sotheby's and Christie's are two famous London auction houses.

Sir Hans Sloane was an Anglo-Irish physician, naturalist and collector, whose personal collection was bequeathed to the British nation on his death in 1753, forming the basis of three of London's major museums.

An artesian well is a well that brings water to the surface without pumping as it's under pressure below.

This was a time when the political machines were very much active in Chicago.

"Queen Anne" refers to the Baroque style of architecture popular during her reign from 1702 to 1714. There was a Queen Anne Revival style going at the time, which is somewhat different. Neither should be confused with the American style of architecture of that name.

The Bank of England is the sole printer of banknotes in England and Wales. Seven banks in Scotland and Northern Ireland are able to print banknotes there, but these are technically not legal tender and will generally be refused in England.

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

#OTD in 1922 – Michael Collins secretly authorised the formation of a specially paid unit of seventy IRA volunteers, known as the Belfast City Guard, to protect districts from loyalist attack.

In the north of Ireland there were continual breaches of the Truce by ‘unauthorised loyalist paramilitary forces’. The predominantly Protestant, Unionists government supported polices which discriminated against Catholics in which, along with violence against Catholics, led many to suggest the presence of an agenda by an Anglo-ascendancy to drive those of indigenous Irish descent out of the…

View On WordPress

#Anglo-Irish Treaty#Arthur Griffith#Belfast#Dublin#England#Footage of Michael Collins in Armagh#History of Ireland#IRA#IRB#Ireland#Irish Civil War#Liam Lynch#Mater Hospital#Michael Collins#National Army#Northern Ireland#Prime Minister#Sinn Fein#Sir James Craig#Winston Churchill

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is your practice Anglo-Saxon?

Have you heard of any of these terms ?

Maiden, Mother and crone

Triple Goddess

Three Mother Goddess

The Mothers

Mabon

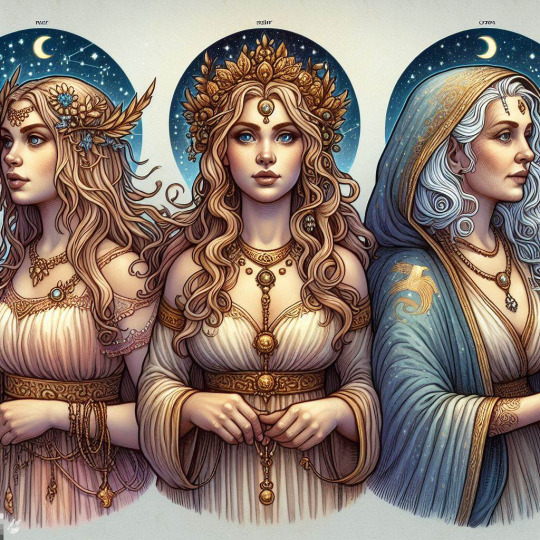

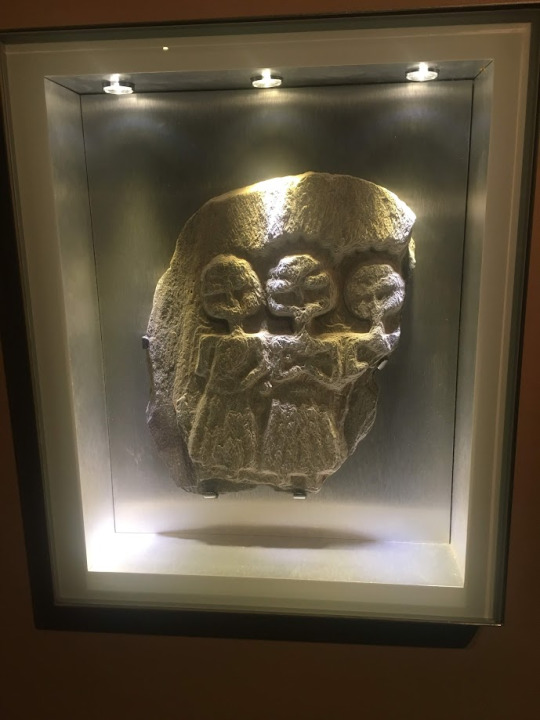

Many of us have the triple goddess as cornerstone of our practice but do you know what you are actually worshiping?

This is one of the earliest representations I have found of the mothers from Bath Spa in England, where pagan traditions from across Europe came together. Although not clear it is the standard three representations, Maiden, Mother and Crone.

The Mothers: The Benevolent Spirits of the Anglo-Saxon Peoples

The Anglo-Saxon peoples, inhabited England from the fifth to the eleventh centuries and had a rich and complex religious system. One of the most intriguing aspects of their beliefs was the concept of the Mothers, the benevolent spirits who protected and nurtured the land and its inhabitants.

The Mothers were female deities associated with fertility, abundance, and prosperity. They were often depicted as matronly women, sometimes holding children or fruits in their arms. They were worshipped in various ways, such as by offering them food, drink, or coins, or by carving their images on stones, altars, or buildings.

The Mothers were not a single entity, but rather a collective term for a variety of local or regional spirits who had different names and attributes. Some of the most well-known Mothers were the Matres, the Matronae, and the Modron.

The Matres and the Matronae were usually depicted in groups of three, representing the three aspects of the female life cycle: maiden, mother, and crone. They were especially popular among the continental Germanic tribes, who brought their practices to Britain during the Anglo-Saxon migrations. It's worth noting however that each tribe had slight different beliefs, stories and rituals.

The Modron was a Celtic goddess who was identified with the Welsh Rhiannon and the Irish Macha. She was the mother of Mabon, the divine son who was kidnapped and rescued by King Arthur and his knights. The same Welsh Mabon celebrated these days at the Autumn equinox.

The Mothers were not only revered by the common people, but also by the kings and nobles, who sought their favor and protection. Some of the most famous Anglo-Saxon kings, such as Alfred the Great and Athelstan, claimed to be descended from the Mothers, thus legitimizing their authority and prestige. The Mothers were also invoked in times of war, as they were believed to grant victory and peace to their devotees.

The Mothers were not completely replaced by Christianity, but rather adapted and assimilated into the new faith. Some of the Mothers were identified with Christian saints, such as Mary, the mother of Jesus, or Anne, the mother of Mary. Others were regarded as guardian angels or holy ancestors, who continued to watch over and bless their descendants. The Mothers were also incorporated into the folklore and customs of the Anglo-Saxon peoples, who celebrated their presence and power in festivals, songs, and stories.

The Mothers were an integral part of the Anglo-Saxon worldview, as they embodied the values and ideals of their culture. They were the sources of life, abundance, and joy, who cared for and sustained the land and its people. They were the symbols of the bond between the human and the divine, the natural and the supernatural, the past and the present. They were the Mothers, the benevolent spirits of the Anglo-Saxon peoples.

Yule Calibration

Did you know the Mothers had their own day of celebration as part of Yule (ġēola or ġēoli in Anglo-saxon). On the first day of Yule, The day before that Winter Solstice. people honoured the Mothers, the goddesses who watched over the family and the land. They offered them food and drink on Mother’s Night, and asked for their blessings for the coming year.

For more ideas click here for my Masterpost

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

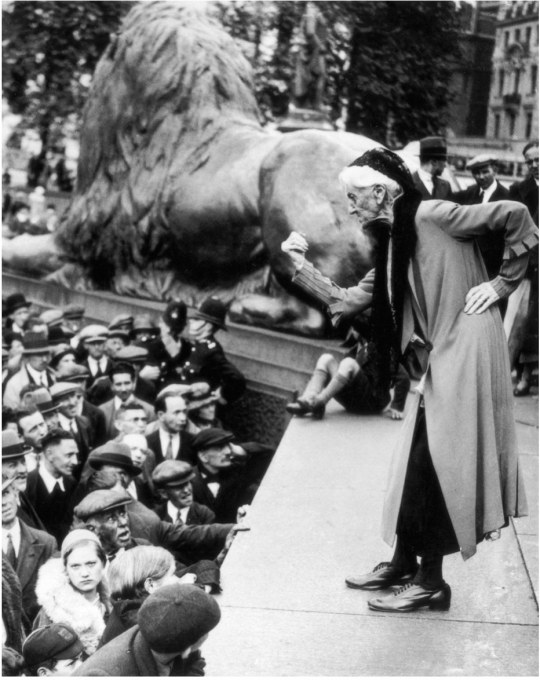

TODAY’S FROZEN MOMENT - 90 Years Ago Today - June 11th, 1933 - Anglo-Irish activist Charlotte Despard riles the crowd at an anti-Fascist rally in Trafalgar Square. Fascinating character Charlotte was. A pacifist, socialist, novelist and famed suffragette, she led countless initiatives and protests on behalf of the poor, women’s equality, against war, and for several political causes. She was frequently arrested, but was fearless and tireless, and her speeches, like this one here, riveted the crowds… Feisty girl…

[Mary Elaine LeBey]

* * * *

“The liberty of a democracy is not safe if the people tolerated the growth of private power to a point where it becomes stronger than the democratic state itself. That in its essence is fascism: ownership of government by an individual, by a group, or any controlling private power.” ― Franklin D. Roosevelt

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

A couple years ago, some morons were claiming it was racist that a 19th century cavalryman had described an Apache scout that he fought beside as “loyal as an Irish hound”.

My dude, the Irish have a war god named “hound”, and both the Irish and Anglos are, uh, just in general kinda big on dogs?

Somehow I think these disingenuous cocksuckers would know to consider the cultural attitudes involved, if someone said “heifer-eyed”, an epithet of goddesses and important mortal women in many parts of India, was an insult. (Go look at a cow’s eyes, if you are confused as to why that is an honorific title for women and goddesses.)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recap of the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The Anglo-Irish Treaty is a very controversial document that sparked the Irish Civil War. But how was it created and what did it actually do?

Truce

A truce between Britain and the IRA was declared on July 11th, 1921. According to the truce, the British agreed to:

Stop the raids and searches

Restrict military activity to support police during their normal duties

Remove the curfew restrictions

Suspend reinforcements from England

Replace the RIC with the Dublin Metropolitan Police

The IRA agreed to

Avoid provocative displays

Prohibit the use of arms

Cease military maneuvers

The IRA released a bulletin, announcing the truce which added additional terms. The British also agreed to:

No incoming troops or munitions

No military movements

No pursuit of Irish officers or men or war material

No secret agents spying

No pursuit of lines of communication

The IRA agreed to:

No attacks on crown forces and civilians

No provocative displays of forces

No interference with government or private property

No disturbing of the peace

Neither side was happy. The British claimed that waving the Sinn Fein flag was provocative and that they had to exert all discipline while the Irish didn’t have to. GHQ complained that according to the treaty the military couldn’t move freely in Ireland. After several disagreements, the British backed down and recalled its forces into their barracks. Meanwhile the IRA believed this was a temporary truce and continued to recruit, drill, and prepare for the resumption of war.

For DeValera, the preliminary negotiations were a chance to reassert himself as the leader of the Dail and Irish liberation.

Preliminary Negotiations

DeValera and an Irish delegation which comprised of Arthur Griffith, Austin Stack, Robert Barton, Count Plunkett, and Erskine Childers traveled to London on July 12th to begin preliminary discussions with Lloyd George. Dev would meet with Lloyd George 4 times between July 14th and the 21st. Lloyd George’s proposal was to turn Ireland into a Dominion but they would have no navy, no hostile tariffs, and no coercion of Ulster. Dev refused, saying that “Dominion status for Ireland would never be real. Ireland’s proximity to Britain would not allow it to develop as dominions thousands of miles away could.” Even though Dev rejected his proposal, Lloyd George continued to honor the truce and Dev returned to Dublin.