#Anglo Amalgamated

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

When you ate a bunch of those brownies the hippie chick at work brought in and now you're paranoid AF.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Completing Anglo-Amalgamated Production's "Sadian trilogy," it's CIRCUS OF HORRORS (1960) from director Sidney Hayers! Starring Anton Diffring, Jane Hylton, Kenneth Griffith and Erika Remberg, this film makes your hosts wonder... what's up with circuses?

Context setting 00:00; Synopsis 13:42; Discussion 24:01; Ranking 39:42

#podcast#horror#classic horror#scream scene podcast#thriller#circus of horrors#sadian trilogy#anglo-amalgamated#sidney hayers#george baxt#leslie parkyn#julian wintle#douglas slocombe#reginald mills#franz reizenstein#muir matheson#lynx films#anton diffring#erika remberg#yvonne moniaur#donald pleasence#jane hylton#kenneth griffith#conrad phillips#jack gwillim#yvonne romain#circuses#billy smart's circus#SoundCloud

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I've seen suffering in the darkness. Yet I have seen beauty thrive in the most fragile of places." - History, Culture and Identity in Cartoon Saloon's Irish Mythology Trilogy

Written accounts of Irish history and culture only begin to appear from the 5th century onwards and what came before we are left to piece together from archaeological remains whose meanings and motivations we can only guess at. What is clear, though, is that during that broad stretch of time between the Early Mesolithic and Late Iron Age, a distinctly Irish identity had been established and cultivated through by the craftsmen, artists, hunters, foragers, farmers and warriors that populated the country through their housing, weaponry, metalworks and stone monuments. The development of the Christian church throughout the Early Medieval period brought its own beauty to the art and architecture of the country, but also adapted its culture to suit the needs of an integrating religion and sites and ceremonies of pagan worship were amalgamated into the Christian calendar. Following this were Viking raids, Anglo-Norman settlement, English conquest, plantation, oppression, rebellion, famine and civil war. From the Early Medieval period to the present day Ireland has experienced an almost constant shift in leadership and identity with little time in between for the dust to settle. Culturally, a "Celtic Revival" in the late 19th and early 20th centuries sought to re-invigorate the arts and history of Celtic Ireland (a broad, problematic concept in itself) as an expression of nationalism and to bolster a distinctly Irish artistic and literary identity. All of this is to say that wading through Ireland's history of social upheaval, religious and political conflict, and loss and confusion of identity is no mean feat. To take those threads and conjure up original stories for modern audiences, embracing the suffering and celebrating the beauty, is impressive. To do it three times is witchcraft.

In their films depicting Irish history, culture and mythology, animation studio Cartoon Saloon have approached their stories with a respect for the past, both fact and fiction. By evoking the artwork, legends and real history of Ireland's past and combining it with their own fresh, unique visual style, Cartoon Saloon brings some much needed authenticity and vibrancy to the depiction of Ireland in mainstream culture. Absent are the twee figures of backwards island folk or the commercialised idolatry of a St. Patrick's Day parade. What we get instead is something more personal, recognisable on the surface to every child and adult who learned about Fionn, the Fianna and fairy circles in primary school and with nuggets of information and visual cues for explorers of Ireland's broader history.

"I can't tell you which parts of this story are true and which parts are shrouded by the mists." - The Secret of Kells and the line between history and mythology

Set roughly in the 9th century AD The Secret of Kells is the earliest depiction of Irish culture in the trilogy. This period saw the introduction of Christianity and the eventual integration of the religion among the native Irish, a relatively smooth transition when compared to later events as noted by historian Jo Kerrigan: "And so the people of Ireland combined the new ways with the old…not bothering too much that the names had changed." Although the main character, Brendan, comes from a Christian monastery and carries those beliefs, The Secret of Kells does well to capture this balance between a new religion and old beliefs with the inclusion of Aisling and Crom Cruach, and without dismissing them as a childish or archaic. "Pagans. Crom worshippers. It is with the strength of our walls that they will come to trust the strength of our faith." The threat of Viking raids is what spurs Abbot Ceallach's desire to build a wall around his monastery, but, underlying his actions is another aspect of a monk's work - converting the natives. In The Secret of Kells the abbot's wall not only protects them from invaders but cuts them off from the forest beyond - the domain of shape-shifters, wild animals and pagan temples, a world that Brendan can only glimpse through a crack in the wall. A staple of the entire trilogy is this depiction of wilderness in some form and its association with Ireland's symbolic wilderness and pagan ancestry. When Brendan enters the forest for the first time it is dark and frightening until Aisling, an ethereal Sídhe figure who can shape-shift into a wolf, shows him how to navigate it. Brendan's fear is eliminated and Aisling quickly becomes his friend, each amused and fascinated by the other.

Hidden throughout Brendan's trek in the forest are old, moss covered ogham stones and stone circles, allusions to native practices, but deeper in, the colour palette changes from bright greens and natural browns to a wash of dark greys and black when Brendan stumbles across a temple to Crom Cruach (a deity who, in Irish mythology, is eventually destroyed by St. Patrick). Aisling tries to warn him away, "It is the cave of the Dark One," but Brendan dismisses her worries, "The abbot says that's all pagan nonsense, there's no such thing as Crom Cruach." At the sounding of the deity's name, black tendrils emit from the cave and pull on Aisling as she stops them reaching Brendan. Later, Brendan returns to the cave to steal Crom's eye - a magnifying crystal that will help Brendan and Brother Aidan with their illumination. In a beautifully animated sequence Brendan battles Crom Cruach in his cave by trapping him in a chalk circle and stealing his eye. Crom Cruach is depicted as a never-ending snake (in a geometric pattern reminscent of both pre-Christian art and the knotwork of Christian manuscripts) possibly in reference to the 'snakes' (demons) banished from Ireland by St. Patrick. What's most fascinating about this sequence is that Brendan experiences it at all. Although the experience is supernatural it is never implied as anything other than real. Brendan is a committed monk in training who will spend his life in service to the monastery and creating the Book of Kells; even after meeting Aisling and battling Crom Cruach he never questions his faith or his elders and when he returns to the monastery with the eye no one disputes the story of how he came by it, "You entered one of the Dark One's caves?" At this time, at the edge of a growing monastery and with a direct reference to the abbot's desire to convert the natives, there is still space for pagan ideas to exist. Whenever Brendan is punished by Abbot Ceallach it is for disobedience not a lack of faith. Similarly, Aisling using Pangur Bán's spirit to free Brendan has an effect on the real world. There's an argument to be made that this is a film and anything can happen, but for problems to be solved by magic, the way Aisling frees Brendan, firm world-building rules must be established; in this world, 9th century Ireland, spaces exist in which otherworldly figures reside and actions beyond the mortal realm occur and these spaces exist alongside this film's version of civilisation, the monastery.

"I have lived through all the ages, through the eyes of salmon, deer and wolf." As an animated feature, there is a lot the film can tell us through visuals alone, and The Secret of Kells does a wonderful job capturing an Ireland in transition. The prologue opens with a close-up image of the Eye of Crom with abstract shapes swimming around it, followed by a glimpse of Aisling hiding in a tree as she narrates over these images in an eery whisper. Following these we see a salmon, deer and wolf, three animals important to Irish mythology, identity and history; the salmon, related to The Salmon of Knowledge, represents mythology, the deer is the national animal of Ireland, and wolves (in the world of Cartoon Saloon) represent its wildernes and history (the elimination of the wolf population became more active in Ireland during times of English occupancy, a theme that is explored more deeply in Wolfwalkers). Even the waves crashing around Iona as Brother Aidan escapes morph into wolves, futhering their symbolism as something wild and dangerous, yet they are never associated with the Viking raiders; the wilderness is as equally affected by change as the people are. The monastery is littered with Iron Age motifs existing alongside Early Christian imagery. Spiral motifs occur in trees and plants, in the ropes that bind the wall's scaffolding together, and circular, semi-circular and zig-zag shapes continue to appear with knot-work patterns and religious figures - even the snowflakes during the raid are strands of knot-work. The monastery itself is accurate to the period with its round tower, beehive shaped structures (called clochán) and the town growing around it, while outside its walls Brendan crosses a stone circle. We even see a game of hurling, the ultimate unifying bridge between pagan and modern Ireland. The walls of the abbot's cell are covered in his own drawings of plans for the monastery's construction. These are exquisitely detailed and clearly a plan for the future but drawn in a style that cannot escape the past; zig-zags, spirals, circles, semi-circles, dots, triangles, sun and star motifs and something that looks like an alignment chart. The style is evocative of the insular La Tène that preceded the arrival of the monks in Ireland; a combination of abstract and geometric, seemingly random, but clearly symbolising something greater.

"You must bring the book to the people." In their last interaction as children Aisling helps Brendan recover the pages of his manuscript as he flees the Vikings. In this gesture Aisling aids Brendan on his religious journey - during the montage later on she even guides him home. Faith never comes between these two, their relationship is one of mutual curiosity and sharing their differences. In Irish mythology, female figures (particularly shape-shifting ones) are often symbolic of Ireland itself and to have the support of these figures is, for kings and heroes, a mark of validation. At this time, these two worlds still live alongside each other and Aisling is allowed to support Brendan's work as a monk while maintaining her own natural way of life. Although Brendan's final journey home shows the spread of Christianity across the country we get one final image of Aisling, changed to her human form in a flash of lightning, that shows us she hasn't disappeared just yet. Brendan, now an adult, returns to Kells and although Abbot Ceallach is old and sick, the monastery stands strong and Brendan brings with him the completed Book of Kells, ready to continue the abbot's work.

"This wild land must be civilised" - Wolfwalkers and the taming of Ireland

Set in 1650, Wolfwalkers occurs roughly 800 years after The Secret of Kells and presents a vastly different universe. The monks' Christianisation of the natives was a far more gentle affair and one founded in a desire to educate people. Ireland under the Lord Ruler (a stand-in for Oliver Cromwell) is a world of service, punishment and fear. By chopping down trees and employing hunters to cull the wolf population the Lord Ruler is attempting to 'tame' the countryside and, most importantly, the people themselves. References to "the old king" and "revolt in the south" place us, historically and politically, in the Cromwellian Conquest, when Cromwell was sent to Ireland to quell uprisings against the newly established English Commonwealth. Heavy stuff and this is a simplification of a period of major conflict in Ireland but Wolfwalkers impresses on us the feeling of living under the thumb of an active oppressor on a much smaller, more personal scale. The Lord Ruler wants the people of Kilkenny afraid and complacent so that they support his efforts to cull the wolves and cut down their forests. Although the wolves pose no threat to the city, people have been made to fear them, resilting in the loss of their connection to the forest outside the town walls. Any reference to a world ouside of the current mode of conduct is cause for immediate punishment and suppression. Even Bill and Robyn, loyal English citizens, are punished. When one of the woodcutters talks of "pagan nonsense" he is confined to the stocks and Robyn is forced to work as a maid in the castle when she does the same. When Bill fails to cull the wolf population (and control his own daughter) he is stripped of his rank as hunter and forced into the role of soldier, robbed of the little freedom he had.

"This once wild creature is now tamed, obedient, a mere faithful servant." Although this line is spoken in reference to Moll, held captive in a cage in her wolf form, it is the human characters who suffer the most from this ideology - even the nameless background characters are confined to the walls of the city. What comes to mind when hearing this line is Robyn in her maid's uniform, once lively and imaginative, now returning home with lines under her eyes after a long day of hard, monotonous work, and Bill, shackled at the neck and forced to march behind the Lord Ruler's horse ("we must do what the Lord Ruler commands"). Although Moll is held captive too, it is in the form of a humongous wolf; she is locked away in the Long Hall for fear of the danger she represents because the Lord Ruler is aware of how poweful she is and so he must keep her locked up to show the people of Kilkenny just how much control he can wield, quelling any potential notions of power they might have held in themselves. In the case of Moll, Robyn and Bill, each time they are held captive by the Lord Ruler their captured bodies submit to the wolf form to escape: Moll uses its strength to break free of her chains, Robyn leaves behind her human body to launch an attack against the soldiers with the rest of the pack, and Bill, who had no idea what being bitten by Moll would do to him, submits to a primal instinct within him to protect his daughter and attacks the Lord Ruler. The Wolfwalkers are able to draw on this power but the people left behind in Kilkenny have no such escape.

"What cannot be tamed, must be destroyed." The ending of Wolfwalkers is bittersweet. Robyn, Médb and their parents are safe after defeating the Lord Ruler and his soldiers and ride off, not quite into the sunset, but onto horizons new. "All is well," Bill and Robyn tell each other and the family appear content, but, before now, leaving the forest was not on the agenda; leaving the forest meant retreating from a threat, as Moll desperately wanted Médb to do, and this is still the case. Médb wanted to save the forest, but, after everything that's happened, the family are no longer safe on the borders of the town. Robyn, Médb, Bill and Moll all save each other but they can't save their home and their retreat from Kilkenny is just that - a retreat. The Lord Ruler may have been killed but that doesn't mean the end of his conquest. Historically, this period saw Ireland amalgamated into the Commonwealth and Irish Catholic landowners ousted by English colonists, as well as a high level of deforestation and the elimination of the wolf population. By having the family leave their home, together and with a bright sky and grassy hills ahead of them, Wolfwalkers' coda balances the narrative conventions of a story by giving the viewers their satisfying ending without sanistising the history it's based on.

"Remember me in your stories and in your songs" - Song of the Sea and loss:

If Wolfwalkers is the taming of Ireland then Song of the Sea is Ireland tamed. Set roughly in the 1980s it is the closest depiction of a modern Ireland in Cartoon Saloon's ouevre. In contrast to The Secret of Kells and Wolfwalkers, which represented Ireland's native identity in the forest, here it takes the form of (drumroll) the sea, but while those other films depicted the battle between the wilderness and civilisation Song of the Sea depicts its defeat. The last of the Sídhe live in hiding in a rath disguised as the centre of a roundabout and use a sewage system to get around. In their diminshed forms, Lug, Mossy and Spud also resemble more closely what we might think of as 'fairies' in Ireland today, not the imposing figures of mischief and chaos the Sídhe really are in mythology. Still, Lug, Spud and Mossy wear torcs, brooches and earrings of gold and strewn about their home are ogham stones and hurls; in a nice marriage of modern and ancient tradition, they play the bodhrán, fiddle and banjo, singing a version of the Irish language song 'Dúlamán'. Only in this one pocket in the middle of the city do different aspects of traditional Irish culture survive.

All throughout Song of the Sea we see iconography of modern Ireland. Conor drinks a pint of Guinness (unlabelled but unmistakable), the front of the pub he sits in is decorated in proto-typical Irish pub fashion. On the wall in Granny's house sits proudly a picture of Jesus with the Sacred Heart lamp as she warbles along to the classic Irish children's song, 'Báidín Fheilimí'. Ben and Saoirse take refuge in a shrine to a holy well with a rag tree outside that is bursting with religious iconography as well as a toy sheep. Symbols that are as much a part of the national identity as those pre-historic and mythological ones. There are also references to the assimilation of pop culture outside of Ireland in a Lyle's Golden Syrup tin, the Rolling Stones poster on Conor's old bedroom door and Ben's 3-D glasses and cape, an emulation of a superhero costume. These images are, ultimately, harmless but have overtaken their native counterparts. Although we see statues of the Sídhe in the background, these are not shrines but detritus, and they lie forgotten, covered in plants and moss, in the company of bags of rubbish and old televisions. The diminishing of one era of Ireland's history to make way for a newer more powerful and modern identity is just one kind of loss that is portrayed in Song of the Sea, but each character experiences their own version throughout. The loss of Bronach that has affected Ben and Conor; the potential loss of Saoirse as she grows sicker; the loss of Mac Lir that drove Macha to such despair she literally bottled her emotions and those of others until they turned to stone. All of this comes to a climax at the end of the film when these tragedies are laid bare. As in Wolfwalkers the greater connotations of this theme are presented on a smaller scale: Ben and Conor's pain by the loss of Bronach.

Ben and Conor are representative of the human world and so suffer her absence more visibly than Saoirse who approaches her mother's world with curiosity and ease. In contrast, Ben, although he misses Bronach, rejects the sea (her home and symbolic identity) and his sister, a physical as well as spiritual reminder of what's been taken away from him. He turns his back on his past as much as he mourns its loss. We see it less obviously in Conor who wallows in his own memories and grief and tunes out Ben's references to his mother "It's as though I've been asleep all these years. I'm so sorry." Ben's grief is more expressive compared to the inwardly focused Conor and even towards the end of the film when Ben is trying to help Saoirse, Conor brushes over his insistence that only her selkie coat can save her. It's only when Saoirse is finally wearing the coat and wakes up from her sickness that he finally engages with Ben on the subject of Bronach, "She's a selkie, isn't she? Like Mam." "Yeah." (Which looks like a weak conversation written down but it's the happy smile on his face and the emotion in his voice that give the single word weight). "Please don't take her from us." During the film's final sequence, when Saoirse sings her song and wakens the sleeping Sídhe, Bronach returns but only to take Saoirse away. With tears in her eyes she begins to lead Saoirse along until Ben and Conor stop her, not forcefully but pleadingly, "she's all we have." All they have is Saoirse, all they have is a thread connecting them to Bronach's world and their memories of her.

"All of my kind must leave tonight…" As the Sídhe are wakened by Saoirse's song we watch them rise joyfully to form a glowing processional in the sky as they make the journey across the sea to their home. This scene is so beautifully animated and so filled with a sense of magic and wonder that we are charmed into believing this is a good thing. The Sídhe are returned to their noble forms and going to their home "across the sea"; they fill the sky with a warm, mystical light, but they are taking that light and their magic with them. As Bronach quotes in the film's prologue, "Come away, o human child, to the waters and the wild, with a fairy, hand in hand, for the world's more full of weeping than you can understand." This is a world that can no longer bear the force of two identities. Unlike The Secret of Kells where Brendan and Aisling were allowed to live alongside each other without compromising their beliefs or ways of living, Bronach, a spiritual being, is forced to leave, while Ben and Conor have no choice but to stay and Saoirse, who walks both worlds, is made to choose between them. Although this is a happy ending it is still being depicted on a personal level. On a grander scale, the country has lost something that isn't coming back and this is depicted as a relief for the ones leaving it behind. On the other hand, Saoirse's decision to remain shows that, in small pockets of the country, the magic remains.

It is fitting that Song of the Sea, as a representation of modern Ireland, draws on loss; Ireland has been experiencing loss on a grand scale for centuries. Although the march of progress is mostly positive, in some cases it has altered our respect and interest in the past. Today there is a nihilism attached to Irish heritage; the spirituality that is associated with airy fairy hippies dancing naked in a moonlit field; the language that is almost universally despised by every secondary student forced to grapple with the Tuiseal Ginideach; its disappearing and continually exploited ecological landscapes; traditions and tales that grow more twee and archaic with every tourist bus that passes by; the preservation of archaeological sites in frequent battle with the progress of industry. In the interest of leaving behind the worst of our past we are at risk of losing the best. The writer Manchán Mangan suggests that this desire to forget lies in the pain we feel when we consider our history. Some, like Conor, try to push all reference to this pain out of their lives, others, like Ben, divert their pain into misplaced anger. Mangan cites the Famine as a source of generational pain and its effect today on our use of the language, but really it can be attached to many events and periods of time, "English was the future; Irish would only bring suffering and death." This is a sentiment that carries through to this day; despite encouragement from schools, local councils and the government, Irish remains a least favourite subject for most people who dismiss it as unuseful for success in the wider world. By proxy, anything to do with the notion of "Irish", the language, history and culture, is old-fashioned (suffering and death) while success and the future lie outside of the country. Mangan goes on to suggest that only by confronting the pain of our past can we unlock an ability in ourselves to engage more fully with our identity, "We might stop blaming our failure to learn on teachers, or the education system, or Government policy, and realise that we have no difficulty learning any other subject…" Ben and Conor are given the opportunity to say goodbye to Bronach before she leaves, allowing them to carry on with their memories of her and the last strand of their connection to her as represented by Saoirse. More and more people today are looking to Ireland's past, ecology and language for whatever it is they need or want to find. It isn't necessary to convert to paganism and live on the shores of the Connemara coastline to achieve this connection, but actively disengaging from your past can only hurt more than it can help. In their respective stories Brendan does not compromise his beliefs but still builds a friendship with Aisling, while Robyn and Bill integrate fully into Médb and Moll's world. There is no right way to engage with this side of our history and identity, but in contrast to Ben and Conor, Brendan and Robyn have balanced and fulfilling relationships with their native counterparts - the threats to their world come from outside sources. Ben and Conor were stuck in their pain over Bronach's loss and it is only after getting to see her one last time that helped them to move on and heal. Conor tells Bronach that he still loves her, he will carry his love and memories of her forever; Ben lets Saoirse into his life and is able to move past his grief and fears of the sea. Here, the threat of loss and destruction in modern Ireland comes from within, and can only be treated by engaging with the past - its rich heritage and tragic history - and moving on with all of the wisdom and experience it provides.

#another late post because my laptop charger broke#cartoon saloon#the secret of kells#song of the sea#wolfwalkers#irish mythology#irish movies#animated movies#animated films#animation#essays#film analysis#movie analysis#i do go on and on don't i

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

I’m afraid I’ve come more and more around to the opinion that Rowling is the kind of author who simply doesn’t think. So to look for an analytical interpretation of anything in the series is probably an exercise in frustration. She paints what is intended as impressive word pictures — essentially vignettes — mainly on the basis of how they are supposed to push your buttons and make you feel, without ever considering how they are supposed to fit together. This sometimes produces a considerable emotional impact, if you are at all sensitive to that kind of jerking around, but it doesn’t necessarily make sense. And sometimes they just plain backfire. Quite a few of these issues are still slowly coming into focus. And one of the sharpest is the awareness that the world Rowling assembled is simply a lot bigger than the narrow-focused, smug, anglo-centric view of it she gave us. Because when you come right down to it, it becomes clear that she never really intended to build a solid secondary world to put her story in. She simply didn’t do the groundwork. Instead, she has ended up with this weird amalgamation that she threw together — which is highly detailed in some areas, and only vaguely sketched in elsewhere with several great gaping holes where you least expect them, to fall right out of the story through. But, back when she first assembled this pretend world, she used the best possible materials available. She mined folklore, and classic (written) tales that have been pretty fully absorbed by the culture, as well as ancient myth, and symbolism that has been around for centuries, she mimicked the authentically traditional “tropes” of how stories are put together and how they work, and she did it with a free hand. But I’m no longer convinced that she did it all consciously. I think she slung a lot of them together because they just “felt” right together. Sure, sometimes she tweaked them before she deployed them, or renamed them, or trivialized the hell out of them, but she hardly ever invented anything new. Most of her elements already existed. The only thing in the Potterverse that is really original are some of her combinations. And, of course, the Dementors. Consequently, as I say, she ended up with something that is a lot bigger than she is. And which upon first encounter comes across as a lot more erudite than she probably really is too, because all of the elements she used to build it came already equipped with their own baggage, and a whole pre-existing collection of associations which all originally led someplace. And most of them are so widely known and/or so universal that even with a 2nd or 3rd-rate education, you are able to recognize them, and are at least somewhat aware of what those particular elements usually mean. And the components are all thoroughly documented, so you can readily find out what the original source meant if you are at all curious. But that doesn’t mean that she ever intended to use any of that material. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts. It is certainly bigger than the shallow, petty, and mean-spirited viewpoint that she keeps pushing into the foreground and expecting us to use as a lens.

via Red Hen's restrospective review of Deathly Hallows, 2008

#red hen#anti jkr#hp meta#jkr critique#writing#myth#appropriation#satire#sff#fantasy literature#liberalism

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

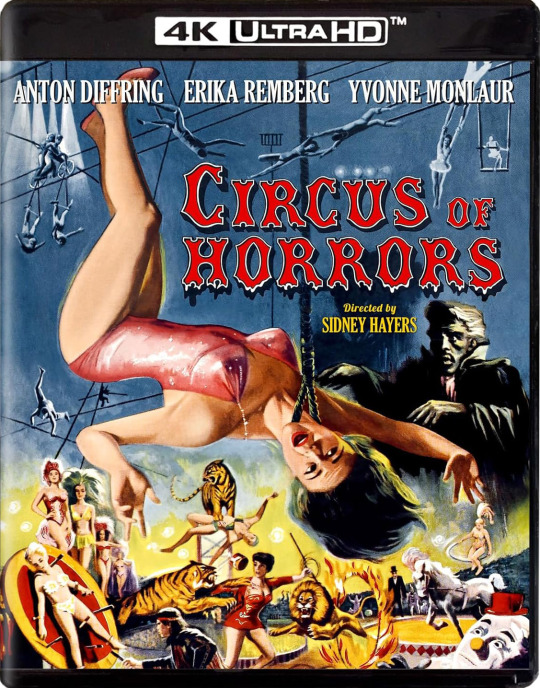

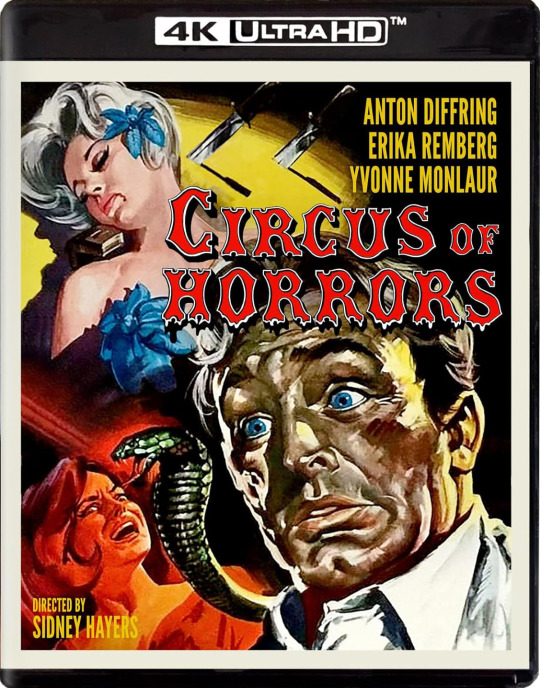

Circus of Horrors will be released on 4K Ultra HD + Blu-ray on October 29 via Kino Lorber. The 1960 British horror film features reversible artwork.

Sidney Hayers (Burn Witch Burn) directs from a script by George Baxt (The City of the Dead). Anton Diffring, Erika Remberg, Yvonne Monlaur, Donald Pleasence, Jane Hylton, and Jack Gwillim star. Anglo-Amalgamated (Peeping Tom) produces.

The film is presented in 4K (SDR) from a 2018 scan of the 35mm original camera negative. Special features are listed below.

Special features:

Audio Commentary by Film Historian David Del Valle

Theatrical Trailer

TV Spots

A deranged plastic surgeon (Anton Diffring) takes over a traveling circus, then transforms horribly disfigured young women into ravishing beauties and coerces them to perform in his three-ring extravaganza. But when the re-sculpted lovelies try to escape the clutches of the obsessed doctor, they begin to meet with sudden and horrific “accidents.” Now the trapeze is swinging, the knives are flying, the wild animals are loose – and “The Grisliest Show on Earth” is about to begin.

Pre-order Circus of the Dead.

#circus of horrors#horror#donald pleasence#60s horror#1960s horror#british horror#kino lorber#dvd#gift#sidney hayers#british film#60s movies#1960s movies#anton diffring

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just found this book that came out this year about botany in the Philippines. Loving her research so far from the previews of the book I've found online.

“Science, or the amalgam of various disciplines that seemingly emerged in Europe, could only attain such a premier position because of its co-constitution with empire and colonialism.

The philosophical fervor with which botanists strove to order plant life erected a way of knowing that could hierarchize all other ways.”

Last but not least...

"The expectation that Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778), considered the father of modern botany, and his apostles could achieve this aim ran headlong into a diversity of ways people understood— and in several respects, continue to understand— plants in Asia and, as this book will cover, in the islands of the Philippines."

https://books.google.com.ph/books/about/Unmaking_Botany.html?id=cepJEQAAQBAJ&source=kp_book_description&redir_esc=y

Someone who has been documenting how Filipinos use, grow, and/or consume Philippine plants in a more empathetic and human way I'd say would be John Sherwin Felix via his Lokalpedia project: https://facebook.com/LocalFoodHeritagePH

You can learn more about Kathleen here: https://www.nybg.org/planttalk/hispanic-heritage-and-philippine-medicinal-plants-the-personal-story-of-kathleen-cruz-gutierrez-ph-d/

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Carry on Cleo (1964) Anglo-Amalgamated Dir. Gerald Thomas

Sid James as Mark Anthony David Davenport as Bilius

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

Radical Ideas

I always laugh when people say that someone is their "brother" or "sister" due to their ethnicity and for lack of a better term "race". It's so dumb because one, just because you share a language and a history does not make you somehow kindred and have inviolable bonds. I have more in common with people from the Midwest and the South than I do from my ancestral lands, the majority being Germany, Ireland and the British Isles in general.

The people who are of Slavic descent in These United States might share a common tongue with their distant relatives but not much else, maybe some religious and cultural practices but besides that. Even Hispanics and Latinos in the US who have family in their mother country, maybe one or two generations removed are different than how they would have been twenty, thirty years ago.

It's just weird that people become so insecure and fall into tribalism when it does not really benefit them or others to be like this. It really does not to try to be in one way in the home and one way in public, accept that you're going to both loose and gain traits from cultural exchange, it's a part of human culture that has been happening since ever. As long as humans have existed, cultural exchange and really change has existed. Trying to conserve something that simply doesn't exist or to propagate it, is extremely dumb.

For example, it's weird to have all African Americans embrace each other as one big "family" not only because they often and conveniently exclude groups like the North Africans like Egyptians and the Copts since they're "just Arabs" but, the collective history of all of these various cultures is so vast and complex that someone from Chad, another from Nigeria and finally someone from Ethiopia don't really have a baseline except, they're all from the African Continent. Their: culture, religion, languages and so much more are so distinct, that they're cousins in a general sense not siblings. Sure, geographic regions like how Europe has geographic regions (the Nords, Francs, Anglos, Slavs of all sorts) but, not this weird cope of a unified identity (I mean if the Island of England has England, Scotland, Wales and the Cornish, plus the fact that no one in England can really decide where the North starts and the South ends there's no way you have larger populations of larger land masses agreeing on a singular unified identity).

I believe this to be both a consequence of diaspora of various minorities and also a certain insecurity when attempting to affirm their own unique cultural identity. For example, I have a friend who's a Filipino and when he was living in Westminster, California (which is where a bunch of Asians of all stripes have settled initially as refugees) now have amalgamated into this weird monoidentity buuut, it's unique only to Westminster, it does not exist in the larger US or even the international community. When I lived in the Twin Cities, I worked at the postal service and again the Twin Cities are a big place for the relocation of refugees and asylum seekers. But, the Hmong stuck with the Hmong, the Ethiopians with the Ethiopians, Tibetans with Tibetans, ect. This was with the first and second generation and probably with the third generation things start to break down and they will integrate with the general population of the area, it's simple ethnographic trends. The only way you prevent this is with groups like the Amish where they simply refuse to integrate or they're just stuck in a relatively isolated area. In a rapidly connecting world people are going to adapt and you can't just set up these arbitrary barriers to make yourself feel special, then you'd be no better than those weird people wanting an ethnostate.

#personal#ramblings#politics#vent#hey listen things are weird culture is weird but#it don't give you the excuse to create a fiction#also the indigenous people argument doesn't really work as a tangent#I mean#borders have always changed#The Cherokee and Crow were fighting over territory with each other as much as they were with the Spanish and Anglos#besides if you go back far enough there's enough families with traces of indigenous blood that was covered up for various reasons#but y'all aren't ready for that conversation yet.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

HISTORICAL IGBO TIMELINES:

STONE AGE -MIDDLE AGES.

This is the period dating 1.2million years to 3000BC , the era of homo-erectus found within the areas of ugwuele uturu following the discovery of Archeolean hand axes and stone tools in caves. Clay pots dating 3000BC were recovered at Afikpo and Opi iron slags .Details of this era is buried in archeology .

EARLY HISTORY:

8th-9 th AD : Kingdom of Nri begins with Eze Nri Ìfikuánim.

1434 AD: Portuguese explorers make contact with the Igbo.

1630 AD : The Aro-Ibibio Wars start.

1690AD: The Aro Confederacy is established

1745AD : Olaudah Equiano is born in Essaka, but later kidnapped and shipped to Barbados and sold as a slave in 1765.

1797AD : Olaudah Equiano dies in England as a freed slave.

1807 AD : The Slave Trade Act 1807 is passed (on 25 March) helping in stopping the transportation of enslaved Africans, including Igbo people, to the Americas. Atlantic slave trade exports an estimated total of 1.4 million Igbo people across the Middle Passage

1830 AD : European explorers explore the course of the Lower Niger and meet the Northern Igbo.

1835 AD: Africanus Horton is born to Igbo ex-slaves in Sierra Leone

1855 AD: William Balfour Baikie a Scottish naval physician, reaches Niger Igboland.

MODERN HISTORY:

1880–1905: Southern Nigeria is conquered by the British, including Igboland.

1885–1906: Christian missionary presence in Igboland.

1891: King Ja Ja of Opobo dies in exile, but his corpse is brought back to Nigeria for burial.

1896–1906: Around 6,000 Igbo children attend mission schools.

1901–1902: The Aro Confederacy declines after the Anglo-Aro war.

1902: The Aro-Ibibio Wars end.

1906: Igboland becomes part of Southern Nigeria (the beginning of our problem)

1914: Northern Nigeria and Southern Nigeria are amalgamated to form Nigeria. (escalation of our problem)

1929: Igbo Women's War (first Nigerian feminist movement) of 1929 in Aba.

1953: November Anti Igbo riots (killing over 50 Igbos in Kano) of 1953 in Kano

1960: October 1 Nigeria gains independence from Britain; Tafawa Balewa becomes Prime Minister, and Nnamdi Azikiwe becomes President.

1966: January 16 A coup by junior military officers takes over government and assassinated some country leaders. The Federal Military Government is formed, with General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi as the Head of State and Supreme Commander of the Federal Republic.

1966: July 29 A counter-coup by military officers of northern extraction, deposes the Federal Military Government; General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi is assassinated along with Adekunle Fajuyi, Military Governor of Western Region. General Yakubu Gowon becomes Head of State.

1967: Ethnoreligious violence between Igbo Christians, and Hausa/Fulani Muslims in Eastern and Northern Nigeria, triggers a migration of the Igbo back to the East.

1967: May 30 General Emeka Ojukwu, Military Governor of Eastern Nigeria, declares his province an independent republic called Biafra, and the Nigerian Civil War or Nigerian-Biafran War ensues.

1970: January 8 General Emeka Ojukwu flees into exile; His deputy Philip Effiong becomes acting President of Biafra.

1970: January 15 Acting President of Biafra Philip Effiong surrenders to Nigerian forces through future President of Nigeria, Olusegun Obasanjo, and Biafra is reintegrated into Nigeria.

References:

Understanding 'Things Fall Apart' by Kalu Ogbaa

Wikipedia

Image Credit: Ukpuru, Pinterest

#kalu#ogbaa#nigerian#ojukwu#emeka#biafra#fulani#hausa#igbos#igbo#nigerian history#igbo history#essaka#africanus horton#african#afrakan#kemetic dreams#africans#afrakans#brownskin#brown skin#african culture

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nigella’s lemon polenta cake is also really good and great for those with gluten sensitivities

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

•~❉᯽❉~•─ Part 2 ─•~❉᯽❉~•

⚝ All witches or magickal practitioners are wiccans.

》 This is the most in accurate thought process to ever sweep through the mundane communities. Wicca is a fairly new practice and is an amalgamation of old world magicks from many different cultures. Wicca was founded in the 1900s and became popular due to the Gardnerian Wicca sect in the 60s. Some Wiccans do not use the term witch, most witches do not use the term Wiccan. All magickal practitioners define theirself differently and the majority are reconstructionalists of cultures that are FAR older than Wicca, in fact before calling someonw a Wiccan or a Witch it is best to ask how the practitioned identifies themself within their practice.

⚝ Witches are female and Wizards and male.

》 A practitioner can be any gender or no gender. To force such a binary thought process onto magick is confining and incorrect. Anyone can practice magick no matter their pronouns. Again, ask the practitioner what they wish to be called in their line of practice. Do not push your thought process onto someone else's ideologies. Instead of you are curious, ask questions before assuming the answers.

⚝ Every practitioner follows The Wheel of the Year.

》 The Wheel of the Year is a Wiccan creation that has taken holidays from older Celtic, Nordic and Anglo-Saxon cultures to create a celebratory timeline. As previously stated not all practitioners are Wiccan and thus The Wheel of the Year is not a part of everyone's practice. You will find those who are not Wiccan may adhere to the wheel but you will also find practitioners who have created their own celebrations. The equinoxes are typically celebrated in most reconstructed cultures, however there are far more holidays within each specific culture than a wheel could ever hold.

In a community such as the Occult, it is common for those who are not members to not understand the nuances of what Occult Community Members truly believe. It is our job to correct the wrong information and to forge ahead in helping those outside our circles to understand. We should never add to the flames of judgment but provide a safe space to give knowledge correctly to those willing to listen. To learn more, visit us at The Occult Lounge Discord.

#occult#occultist#occultism#occult community#occultblr#pagan#paganism#pagan community#paganblr#witch#witchcraft#witchy community#witchblr#spirituality#spiritualism#discord

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joan of Arc Couldn't Ride a Horse

My father is Catholic, my mother agnostic, and within me these two magnets war like poles casting off gravity in their urge to repel each other. As a child I became religious at my father's observance, on a whim, that because of my middle name, Joan of Arc is my patron saint. I was stunned. I came from a coastal Oregon town where we rode bikes around, chewed gum if we could get it; built forts on the beach or in the woods. Sainthood, patron saints, Catholicism, the cathedrals of France—all a new, albeit arcane magic. Tell me, as a lost and homesick 11-year old, that a radical woman on horseback is coming to lead me.

We had settled in France, and I was learning French. I knew authoritatively that she was really Jeanne d'Arc, although all I had to go on was an (ironically British) 1971 Ladybird book written by Lawrence du Garde Peach, an English actor and radio playwright who was in military intelligence during World War I. This child's book gently whitewashed the massive overlay of bubonic plague, the Hundred Years' War; virginity exams; threats of rape; the hardness of life in the 15th century.

By the time we found our way to the Rouen marketplace where she was burned I did not care if she was schizophrenic, mad, or called by God to drive the English armies out of France—I believed in her wholly, the way only a teenaged girl can believe in another teenaged girl who has been tied to a stake and burned.

Since that point my long struggle has been away from religion, letting go of the fervent superstitions of faith, to my mother's flip side, viewing religion as weak-minded, for the masses. I wanted to believe that I was smart and scientific. Then, as the slow tragedy of life drove me past that, out of a greater necessity, I began to find the similar persuasions in the way of the Tao, and in the massive, gorgeous visions of Black Elk, and in the perfunctory spiritual power of the AA 12-Steps.

Then, in a story I'm working on, one character turned to another and said: 'You know, Joan of Arc couldn't ride a horse.'

Offended, this sent me down into the research warrens, where I soon ran into the French historian Régine Pernoud and her book Jeanne d'Arc, and also five hours of the double film Jeanne La Pucelle (1994.) Pernoud cemented the deal by confessing that she had always avoided Jeanne for her mythy, overblown teenaged religious saga. However, one day she made that fatal karmic mistake of opening just the right book to just the right page, and the girl's clear treble voice rose from those documents like a mystic voice in a churchyard.

Caught up in a similar manner I found myself writing The Prisoner of the Chateau-Forte du Louvre.

The upshot of all this was that yes, of course Jehanne of Domrémy could ride a horse. Horses were such an integral part of her image that one of her chargers was put to death when she was killed. She had grown up riding her father's plough horses, and ultimately she could handle a galloping Percheron while wearing full armor, carrying a standard, and exhorting an army to follow her—to use an Anglo-French word amalgamated over La Manche—into the affray.

___________________

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lemon Polenta Cake by Nigella

Yields: 12 - 14 slices

Ingredients

Cake

1 3/4 sticks soft unsalted butter (plus some for greasing)

1 cup superfine sugar

2 cups almond meal

3/4 cup fine polenta (or cornmeal)

1 1/2 teaspoons baking powder (see NOTE below)

3 large eggs

Zest of 2 unwaxed lemons (save juice for syrup)

Syrup

juice of the 2 unwaxed lemons above

1 cup confectioners' sugar

Instructions

1. Line the base of a 23cm/9inch springform cake tin with baking parchment and grease its sides lightly with butter.

2. Preheat the oven to 180°C/160°C Fan/gas mark 4/350°F.

3. Beat the butter and sugar till pale and whipped, either by hand in a bowl with a wooden spoon, or using a freestanding mixer.

4. Mix together the almonds, polenta and baking powder, and beat some of this into the butter-sugar mixture, followed by 1 egg, then alternate dry ingredients and eggs, beating all the while.

5. Finally, beat in the lemon zest and pour, spoon or scrape the mixture into your prepared tin and bake in the oven for about 40 minutes.

6. It may seem wibbly but, if the cake is cooked, a cake tester should come out cleanish and, most significantly, the edges of the cake will have begun to shrink away from the sides of the tin. remove from the oven to a wire cooling rack, but leave in its tin.

7. Make the syrup by boiling together the lemon juice and confectioners' sugar in a smallish saucepan.

8. Once the confectioners' sugar’s dissolved into the juice, you’re done.

9. Prick the top of the cake all over with a cake tester (a skewer would be too destructive), pour the warm syrup over the cake, and leave to cool before taking it out of its tin.

Notes

To make this cake gluten-free, make sure to use gluten-free baking powder, or omit the baking powder altogether and beat the batter exuberantly at step 4.

To make this cake dairy-free, substitute 150ml light and mild olive oil for the 200g of butter, making sure you still whisk the oil and sugar together very well in step 3.

MAKE AHEAD: The cake can be baked up to 3 days ahead and stored in an airtight container in a cool place. Will keep for a total of 5-6 days.

FREEZE: The cake can be frozen on its lining paper as soon as cooled, wrapped in a double layer of clingfilm and a layer of foil, for up to 1 month. Defrost for 3-4 hours at room temperature.

0 notes

Text

Hmm. Thinking about the “young angry men” phenomena people have been talking about on here recently. I think looking at the self-reported statistics (at least in Anglo N America), it’s less that younger men are becoming more sexist/reactionary, but that younger women are embracing feminism and progressive social values at a quicker rate than their male counterparts (which, to be clear, good for them). So the political gender gap in adult Gen Z demographics is a result of women being over all much less conservative than their parents while men are either only slightly less conservative or remain the same. Why is this the case? I don’t know, and I think too much speculation is unhelpful. Nevertheless, I do think we can look at some possible routes to understanding this emerging phenomenon. Namely, to me it’s difficult to tell if this phenomenon should be understood as primarily effecting women (to be more progressive) or men (to be more conservative).

One’s interpretation of this final question usually falls along partisan lines. Those of a left leaning persuasion tend to focus on a rise in reactionary politics in men and those of a right leaning persuasion focus on a rise in feminist rhetoric amongst woman. Now, while my sympathies lie with the former, I think both are appealing to a naturalistic fallacy that positions their own politics as an organic development and those of their rivals as an aberration. Therefore I see no issue with approaching both position with equal skepticism, disregarding my own sentiments.

First of all, something that doesn’t seem to be mentioned too often is that feminism, as a movement and set of ideologies, is bound to be more partisan amongst the men than it is amongst women. To showcase this, let us imagine we can divide both populations into two equal ethical positions: one is more solipsistic, concerned with one’s own status in society and universalizing only their personal issues while the second is concerned with the welfare of their fellows, a worldview which situates the individual in the community and encourages the this individual to be concerned with the welfare of all.

Now, in this simplistic model, we should expect both positions to favour feminism amongst women yet only the latter to favour feminism amongst men. The reason should be clear: while anyone who is dedicated to the betterment of society at large should lean towards such emancipatory movements as feminism, for those who are more concerned with only their own status only those for whom said emancipatory movement directly applies would favour it. This seems to be the most obvious reason for the political gender gap to me.

However, the effect of the so-called “Manosphere” and similar anti-feminist movements must also be mentioned. Early attacks upon feminism usually came from incoherent groups of traditionalists. There was feminism: a reformist (and revolutionary, though this interpretation seems to have faded into a negligible status) movement in opposition to a patriarchal society, and there were those who defended the patriarchal society. Now, however, these “defenders of patriarchy” have amalgamated themselves into something more recognizable as a movement of its own. They even have attracted their own thinkers (as pathetic as they may be) and have set down an ideology which is more than just a repetition of gender roles handed down from religious and academic elites. In effect, as in many such cases throughout history, those in opposition to a successful new social movement have now learned some of the keys to its success and have sought to repeat them for their own benefit.

Which of these explanations do I favour? I don’t know, likely a mix of the two. And obviously these dynamics are still evolving and should be understood as much more complex than what I can write here. These are just two of my personal interpretations of the behaviours we are witnessing within the younger voting generation and should be regarded as nothing more than the navel gazing of a curious blogger.

0 notes

Text

The author critically differentiates the two expressions. A historical analysis by Aristotle serves as a convincing and illuminating paradigm of the difference between chance and fortune. The terminologies fortune and chance, luck and misfortune are compared in daily or normal parlance and also in the business milieu. It is imperative that chance and fortune being evaluated in the business and the economic sector. This argument is coherent and explanatory though it is incapable of clearly defining and differentiating these expressions. The argument that fortune and chance can be controlled and comprehended is put forward. This was as suggested by Machiavelli. However, Machiavelli also agrees that half of what happens is unplanned. He categorically argues that, fortunes can be controlled and strategies must be developed to evade and elude chance. People of Latin origin view what is unexpected as fortune while the Anglo Saxon views it as chance. There is a clear differentiation of the applicability of these two terms based on the cultural difference. Further, the Latin culture emphasize that destiny can be altered and deciphered while in the economic and administrative perspective, chance is indescribable, indeterminate and un-understandable. Again, the author indicates that, in business, people may be victims or beneficiaries of unknown circumstances with no apparent derivation. Irrespective of the meanings of fortune, lack, chance and misfortune, Business and organization suffer either a loss or a gain as a direct or indirect consequence of uncertainties. Both the Anglo-Saxon and the Latin fail to define measures that can control, describe or alter misfortune and chance (Derr, 1987). This argument is well supported in the economic and administrative sectors who perceive chance as inexplicable and undetermined but as having either positive or negative implication based on their nature. Latin's view chance as unfathomable and based on Gods logic while the Agro-Saxon view it as divine logic that is beyond human reason. Again, for Gods perceptive the two regions seem to categorize fortune and chance as unplumbed and beyond human indulgent. Nevertheless chance and misfortune may have beneficial and detrimental effects. The author presents the effects of perceptions of chance and misfortune with respect to organizations. To do this, a critical appraisal of literature by Michel de Motaigne (Hollier, 1995), Becker (1994), Toffler (2000), is done. Michel de Motaigne attributes success in any field to fortune. The Latin's defend against uncertainty by refuting seduction related to fortunes while the capitalist administrative agenda is centered on precision and daringness. For the Latin, good and bad fortunes results to greater concerns on liability while the Anglo-Saxons mainly strategize against market fluctuations by enhancing their opportunities and threats towards the organization funds. The Latin's tend to reduce the distance between the desirable and the possible events while the Anglo-Saxon amalgamates both the probable and improbable events. The issues of cultural and location views towards chance and misfor Read the full article

0 notes

Text

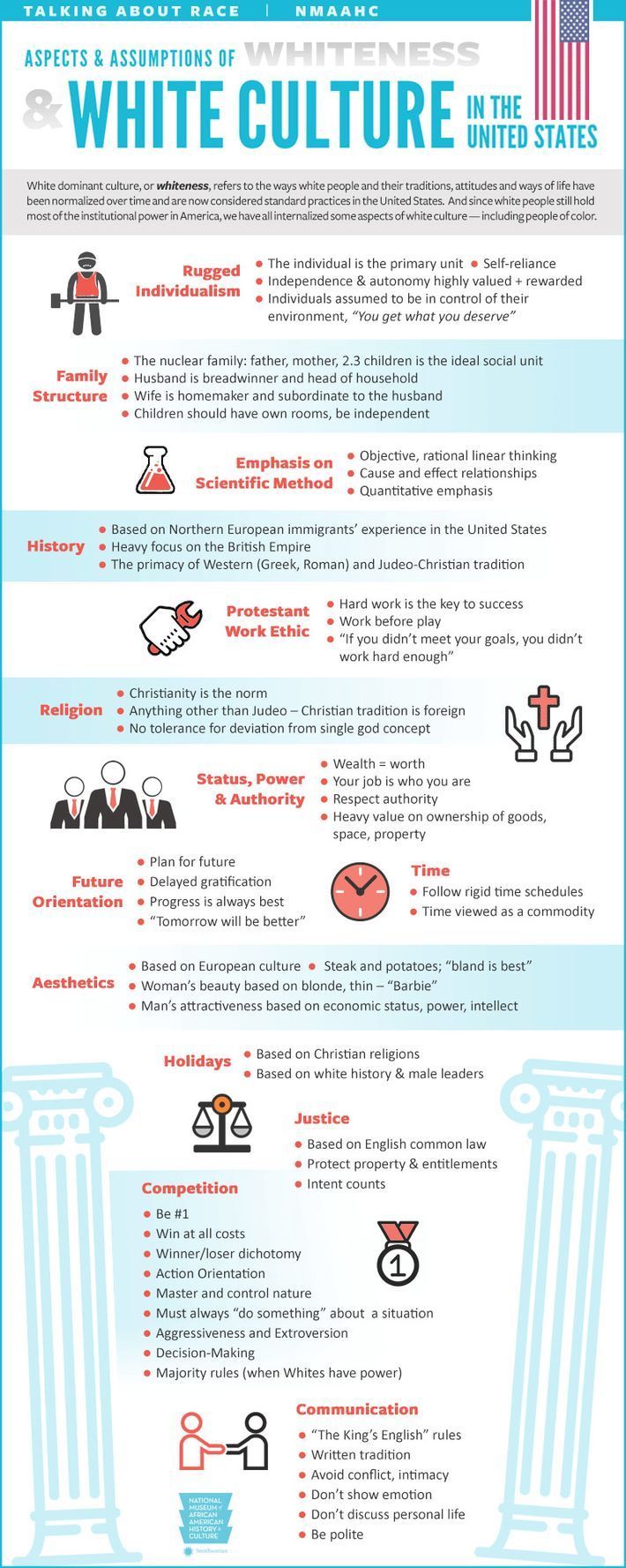

"White American" is a broad, socially constructed identity that amalgamated multiple different European ethnic groups. What is often misunderstood is that the stereotypical "White Culture" as we understand it today is actually, in its origins, something "Anglo-Saxon." Non-Anglo Europeans like that of Hungarians, Italians, and Spaniards do not have the same culture of rigid individualism. It only so happened that Anglo-Saxon culture absorbed the peripheral European identities into what we now perceive to be White.

0 notes