#Amu Darya

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Amu Darya Sturgeon

Pseudoscaphirhynchus kaufmanni, commonly known as either the Amu Darya sturgeon or the false shovelnose sturgeon, is native to the Amu Darya river basin in Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan. The Amu Darya sturgeon grows around 30 inches long excluding its ribbon-like tail filament, which adds around another 10 inches to its total length when included. This sturgeon is not noteworthy for its large size, like some of its lengthier cousins. Instead, you’ll find yourself mesmerized by this sturgeon’s scintillating scutes! There are two beautiful morphs of this species: a large morph with pearlescent white coloring, streaked with pale blues and purples, and a smaller, more quickly maturing morph with a darker coloration. The Amu Darya sturgeon is critically endangered due to habitat loss, overfishing, pollution, and poaching.

#sturgeon#sturgeon fish#sturgeonfish#sturgeon facts#amu darya#amu darya sturgeon#false shovelnose sturgeon#fish#fishing#fish facts#ichthyology#marine biology#pseudoscaphirhynchus kaufmanni

785 notes

·

View notes

Text

You get an Amu Darya Sturgeon

Pseudoscaphirhynchus kaufmanni

you gotta hand it to me

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

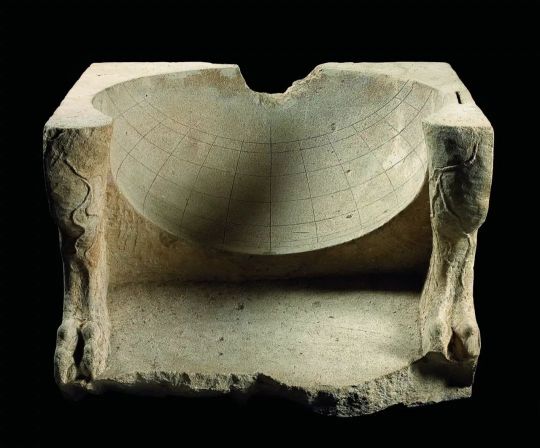

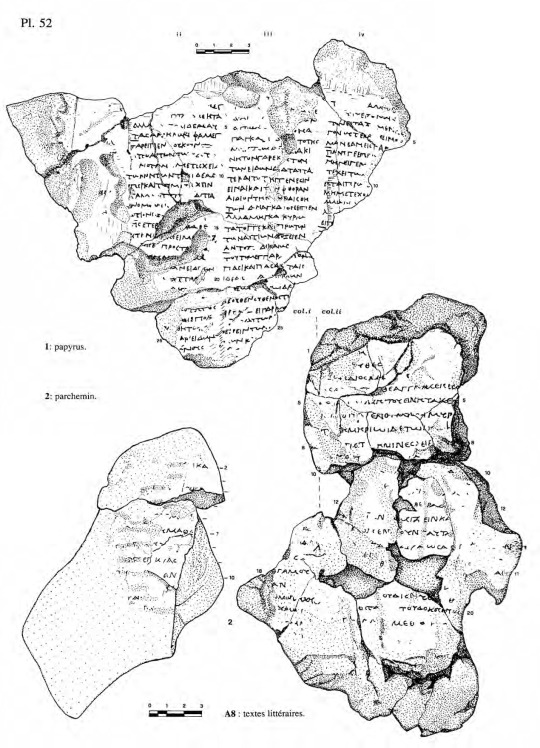

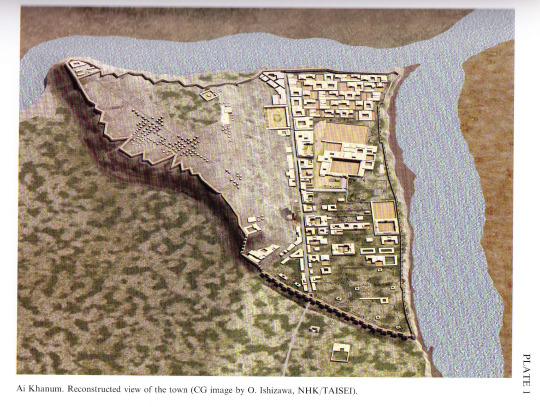

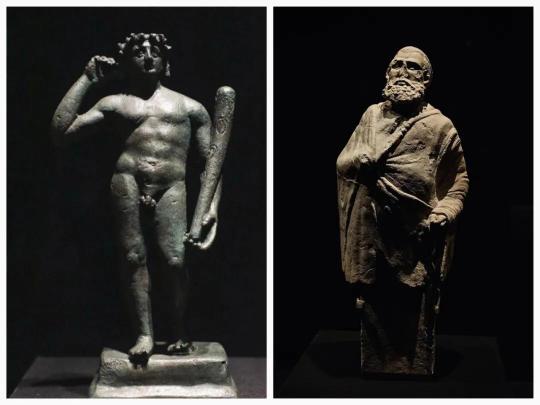

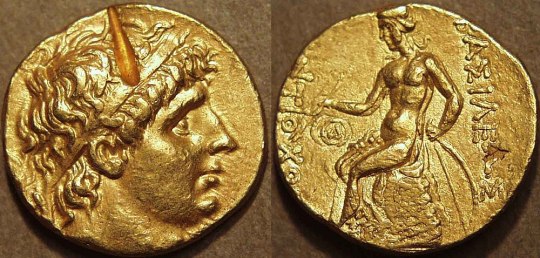

Ai Khanoum 3rd C. BCE - 2nd C. CE. More images on my blog, link at bottom.

"These wise sayings of men of old, The words of famous men, are consecrated At holy Delphi, where Klearchos copied them from carefully To set them up, shining from afar, in the sanctuary of Kineas.

As a child, be well behaved; As a young man, self-controlled; In middle age, be just; As an elder, be of good counsel; And when you come to the end, be without grief.

—trans. of Ai Khanoum stele by Shane Wallace and Rachel Mairs.

Ai-Khanoum (/aɪ ˈhɑːnjuːm/, meaning Lady Moon; Uzbek Latin: Oyxonim) is the archaeological site of a Hellenistic city in Takhar Province, Afghanistan. The city, whose original name is unknown, was likely founded by an early ruler of the Seleucid Empire and served as a military and economic centre for the rulers of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom until its destruction c. 145 BC. Rediscovered in 1961, the ruins of the city were excavated by a French team of archaeologists until the outbreak of conflict in Afghanistan in the late 1970s.

The city was probably founded between 300 and 285 BC by an official acting on the orders of Seleucus I Nicator or his son Antiochus I Soter, the first two rulers of the Seleucid dynasty. There is a possibility that the site was known to the earlier Achaemenid Empire, who established a small fort nearby. Ai-Khanoum was originally thought to have been a foundation of Alexander the Great, perhaps as Alexandria Oxiana, but this theory is now considered unlikely. Located at the confluence of the Amu Darya (a.k.a. Oxus) and Kokcha rivers, surrounded by well-irrigated farmland, the city itself was divided between a lower town and a 60-metre-high (200 ft) acropolis. Although not situated on a major trade route, Ai-Khanoum controlled access to both mining in the Hindu Kush and strategically important choke points. Extensive fortifications, which were continually maintained and improved, surrounded the city.

Many of the present ruins date from the time of Eucratides I, who substantially redeveloped the city and who may have renamed it Eucratideia, after himself. Soon after his death c. 145 BC, the Greco-Bactrian kingdom collapsed—Ai-Khanoum was captured by Saka invaders and was generally abandoned, although parts of the city were sporadically occupied until the 2nd century AD. Hellenistic culture in the region would persist longer only in the Indo-Greek kingdoms.

It is likely that Ai-Khanoum was already under attack by nomadic tribes when Eucratides was assassinated in around 144 BC. This invasion was probably carried out by Saka tribes driven south by the Yuezhi peoples, who in turn formed a second wave of invaders, in around 130 BC. The treasury complex shows signs of having been plundered in two assaults, fifteen years apart.

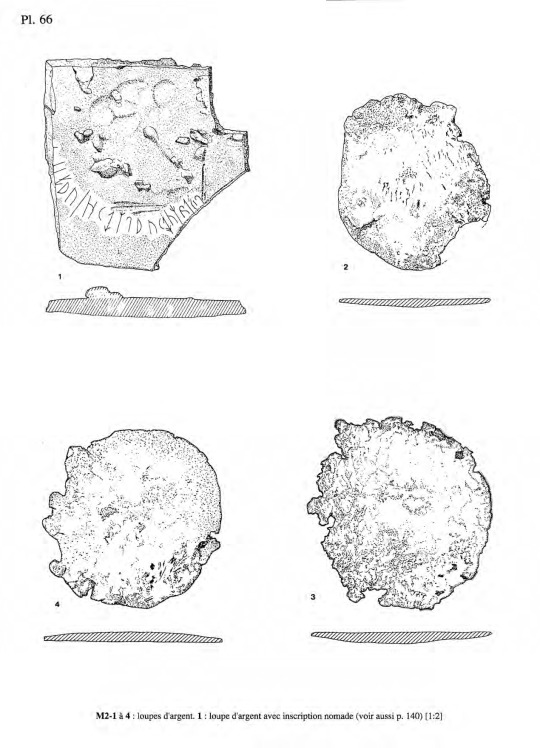

Although the first assault led to the end of Hellenistic rule in the city, Ai-Khanoum continued to be inhabited; it remains unknown whether this reoccupation was effected by Greco-Bactrian survivors or nomadic invaders. During this time, public buildings such as the palace and sanctuary were repurposed as residential dwellings and the city maintained some semblance of normality: some sort of authority, possibly cultish in origin, encouraged the inhabitants to reuse the raw building materials now freely available in the city for their own ends, whether for construction or trade. A silver ingot engraved with runic letters and buried in a treasury room provides support for the theory that the Saka occupied the city, with tombs containing typical nomadic grave goods also being dug into the acropolis and the gymnasium. The reoccupation of the city was soon terminated by a huge fire. It is unknown when the final occupants of Ai-Khanoum abandoned the city. The final signs of any habitation date from the 2nd century AD; by this time, more than 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) of earth had accumulated in the palace.

While on a hunting trip in 1961, the King of Afghanistan, Mohammed Zahir Shah, rediscovered the city. An archaeological delegation, led by Paul Bernard, unearthed the remains of a huge palace in the lower town, along with a large gymnasium, a theatre capable of holding 6,000 spectators, an arsenal, and two sanctuaries. Several inscriptions were found, along with coins, artefacts, and ceramics. The onset of the Soviet-Afghan War in the late 1970s halted scholarly progress and during the following conflicts in Afghanistan, the site was extensively looted."

-taken from Wikipedia

...

"The silver ingot engraved with runic characters found during the excavations of the Treasury could suggest they were Sakā/Sai. This inscription comprises 21 characters of a script and a language that are unknown and both attributed to nomadic people of Sakā origin, by comparison with a dozen similar inscriptions coming from an area extending from Ghazni in Afghanistan to Almaty in Kazakhstan, and dated between the 5th century BC and the 8th century AD."

-taken from Ai Khanoum after 145 BC: The Post-Palatial Occupation by Laurianne Martinez-Sève, University of Lille, 2018

#ancient history#antiquities#art#paganism#statue#museums#sculpture#history#greek art#greek gods#ancient greek#greek myth#scythian#pagan#ancient art#afghanistan

196 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Oxus

The Oxus is a river, today called Amu Darya in its western part and Wakhsh in its eastern parts, which flows for a length of 2400 km across modern Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan into Lake Aral. In Ancient times it crossed the regions Fergana, Bactria, Oxeiana, Sogdiana and Khiva. The Oxus and the Iaxartes are called twin rivers, because of their same destination, almost similar trajectories and because they both are thankless rivers, naturally irrigating only very few areas through which they flow. However, like the Iaxartes, the Oxus allowed large-scale irrigation systems which was the main reason of its area's rich history. The Oxus was the nucleus of the successive Bactrian civilizations and kingdoms. The river was the borderline between the Persian satrapy of Sogdiana northward and Bactria southward, whereas the western part belongs to nomads. Several cities were founded here, mostly known under their Greek names, like Alexandreia Oxeiana (actual Termez). Alexander the Great came across the river three times between 329 and 327 BC. Later, the Eastern part of the Oxus was the nucleus of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom, whereas the western part, especially the Khiva Oasis, was the land of the Parni, who later became the Parthians invading the Seleucid empire.

Continue reading...

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

While in orbit over central Asia, an astronaut aboard the International Space Station took this photograph of Fayzabad. The city, the capital of the Badakhshan Province, lies in a mountainous part of northeastern Afghanistan at an elevation of roughly 1,200 meters (4,000 feet).

The city is situated along the Kokcha River, which flows northward within a deep river valley surrounded by the Hindu Kush Mountains and eventually discharges into the Amu Darya River.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ai-Khanoum

Another real life reference!

Ai-Khanoum, meaning "Lady Moon," is an ancient Hellenistic city located in Takhar Province, Afghanistan, rediscovered in 1961. Likely founded between 300-285 BC by a Seleucid ruler, it served as a military and economic center for the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom until its destruction around 145 BC. Initially thought to have been founded by Alexander the Great, it's now believed to have been established under Seleucus I Nicator or his son Antiochus I. The city, located at the confluence of the Amu Darya and Kokcha rivers, was well-fortified and strategically important, although not on a major trade route.

Ai-Khanoum flourished under Seleucid and Greco-Bactrian rulers, but lost significance when the Greco-Bactrians gained independence under Diodotus I. It regained prominence under Euthydemus I and Eucratides I, the latter redeveloping the city, possibly renaming it Eucratideia. After Eucratides’ death, the city fell to Saka invaders around 145 BC and was mostly abandoned, although parts were sporadically inhabited until the 2nd century AD.

Archaeological excavations led by Paul Bernard revealed a large palace, gymnasium, theatre, and sanctuaries, but were halted by conflict in Afghanistan in the 1970s, and the site was later looted.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

In many places in Europe, as well as outside of it, e.g. in Asia, there are legends told about figures, usually of female gender, who, according to folk belief, watch over spinning, punish lazy spinsters, make sure that no spinning is done on days when spinning is forbidden and so forth. Many legends tell of the visits of these beings, and how they punish spinsters who violate spinning taboos or fail to finish their spinning on time etc. They are also frequently described as being equipped with flax and spinning tools while in the act of spinning.

Thus, in Slovenia, Austria and Germany we find Perchta/Pehtra/ Perhta/Pehtra baba/Pehtrna/Pirta/Pehta/Percht/Berchta/Zlata baba, in Germany Frau Holle or Holda, Stampe/Stempe/Stempa, and in Switzerland Frau Saelde in the role of the “Spinnstubenfrau”. The most prominent Slovenian researcher in these traditions, Niko Kuret, points out the similarities with beings which in Slovenia we also know by other names, such as Kvatrnica, Torka or Torklja. The Italians know a similar being named Befana, the French have Tante Airie, and we also find them with several different names in Central Asia, from Iran through Tajikistan to the basin of the lower Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers etc. (Kuret 1997; 1989, II: 458). There are also various other beings with whom we could equate them to a certain extent, for instance the French Heckelgauclere, the Swiss Sträggele and Chrungele, the German Herke, the Slovenian/ Czech/Slovakian Lucy and others.

Mythical beigns punishing the breaking of taboos on spinning by Mirjam Mencej

#Perchta#Zlata Baba#Kvatrnica#Torklja#Mokosh#Folklore#slavic folklore#slovene folklore#czech folklore#russian folklore#slavic mythology

188 notes

·

View notes

Text

Submitted via Google Form:

How big can a desert oasis be? I know the Nile river delta is massive but how much bigger can it get? I'd like to have one half the area of Egypt. What also needs to be done about the rivers that flow into them?

Tex: An oasis has a geological underpinning that is man-made in its longevity (Wikipedia), so I suppose they’re only as large as they need to be. Some factors in that include amount of irrigation, size of the underlying water table, how long you can travel from one oasis to another before running out of water, and mode of transportation that typically dictates rate of travel. By definition, an oasis resides in a desert. If something is large enough to cover, as you say, half of Egypt, then the resulting changes in the local environment might create a temperate climate rather than an arid one. Rivers are part and parcel with sedimentary or metamorphic rocks because of its more porous nature than igneous rock, and are the surface-visible part of water movement that also works underground through things like water tables/aquifers.

Licorice: Apparently the largest oasis in our world is 33 square miles. It has four cities and 22 villages. It's in Saudi Arabia and it's called Al-Ahsa. Al-Ahsa_Oasis (Wiki)

I think it might all be a question of scale. An oasis half the size of Egypt wouldn’t be an oasis in the Sahara desert, but if your desert took up half your planet, then that huge oasis might be considered an oasis.

Utuabzu: The exact definition of oasis gets a little fuzzy, since it’s not super clear at what point your lake becomes an inland sea. But an oasis is typically a body of water formed by upwelling groundwater - generally from an artesian basin of some kind - in an otherwise arid environment. They can range in size from a glorified puddle to the one Licorice mentioned, and they’re not necessarily permanent features on the landscape. Plenty of oases are seasonal, only present when the groundwater has risen due to rains elsewhere and vanishing again once the water table drops.

You mentioned the Nile Delta, which is not an oasis. I suspect you may have meant the Fayum, which is a body of water formed by a branch of the Nile entering an endorheic basin - a watershed that cannot empty to the sea because it is too high on all sides - and has been and remains a very agriculturally productive region of Egypt. Endorheic basins can also produce what are called inland deltas, where a river fans out into a large wetland at the bottom of the basin, as it is unable to reach the sea and does not have high enough water flow to flood the basin and create a lake or inland sea. Examples of this include the Okavango Delta in Botswana and the Sistan Delta in Iran and Afghanistan. More commonly endorheic basins have lakes (often salt lakes) or saltpans at their lowest points, and small or intermittent to non-existent waterways.

If we take what you want to be a region approximately the size of Egypt with a river that ends in a delta but does not flow into the sea, surrounded by desert, then that is possible. The Syr Darya and Amu Darya rivers flow through the Central Asian deserts and steppe to empty into the Aral Sea, which is an endorheic basin that once housed an enormous freshwater lake.* The region between these two rivers - called Transoxiana in classical sources - has been home to a chain of vibrant, prosperous civilisations and a vast diversity of peoples and cultures. So if you want to have a big river run through a desert and empty either into a lake or an inland delta, so long as you know where the water is coming from - the Syr Darya and Amu Darya are fed by snowmelt from the Hindu Kush and Tian Shan mountains, while the White Nile, which is the source of the Nile floods, rises in the Ethiopian Highlands and is fed by the wet season rains there - then there’s really no reason why you shouldn’t. Far stranger things exist in real life.

*Soviet hydroengineering has resulted in the Aral Sea all but drying up, causing immense ecological damage to Central Asia.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Stalin to the members of the Politburo and Adoratsky 19 July 1934 F. 17, op. 3, d. 950, ll. 82–86. Typewritten original.

To the members of the Politburo and Comrade Adoratsky.

In sending out Engels’ article “The Foreign Policy of Russian Tsarism,” I find it necessary to preface it with the following comments.

Comrade Adoratsky is proposing to publish in the next issue of Bolshevik, which is devoted to the 20th anniversary of the imperialist world war, Engels’ well-known article “The Foreign Policy of Russian Tsarism,” which was first published abroad in 1890. I would consider it quite normal if the proposal was to print this article in a collection of Engels’ works or in one of the historical journals. But the proposal to us is that it be printed in our militant journal, in Bolshevik, in an issue devoted to the 20th anniversary of the imperialist world war. Therefore this article is evidently considered to be a source of guidance, or at any rate profoundly instructive for our party functionaries with regard to clarifying the problems of imperialism and imperialist wars. But unfortunately, despite its merits, the content of Engels’ article makes clear that it does not possess these qualities. Moreover, it has a number of shortcomings that, if published without criticism, may confuse the reader.

I would therefore consider it inadvisable to publish Engels’ article in the next issue of Bolshevik.

But what are the shortcomings?

1. In describing the expansionist policy of Russian tsarism and doing justice to the abominations of that policy, Engels does not attribute it primarily to the “need” of Russia’s military-feudal-mercantile leaders for outlets to the seas and seaports, for an expansion of foreign trade and control of strategic locations. Instead he gives more weight to the notion that Russia’s foreign policy was led by a supposedly all-powerful and very talented gang of foreign adventurists, which for some reason was lucky everywhere and in every endeavor, which surprisingly managed to over come each and every obstacle on the path to its adventurist goal, which duped all of the European rulers with surprising dexterity and finally reached the point where it had made Russia the most militarily powerful state.

This treatment of the issue by Engels may seem more than incredible, but it is, unfortunately, a fact.

Here are the relevant sections of Engels’ article.

“Foreign policy,” Engels states, “is unquestionably the realm in which tsarism is very, very strong. Russian diplomacy constitutes a kind of new Jesuit Order, which is powerful enough to overcome, when necessary, even the tsar’s whims and, while spreading corruption far beyond itself, is capable of stopping corruption in its own midst. At first it was primarily foreigners who were recruited for this Order: Corsicans, such as Pozzo di Borgo; Germans, such as Nesselrode; and Ostsee [Baltic Sea] Germans, such as Liven. Its founder, Catherine II, was also a foreigner.”

“To this day only one full-blooded Russian, Gorchakov, has held a high post in this order. His successor, von Girs, again bears a foreign surname.”

“It was this secret society, whose members were recruited originally from among foreign adventurists, that elevated the Russian state to its present might. With iron perseverance, steadfastly pursuing its objective, not stopping at perfidy, treachery, or assassination from around a corner, or fawning—unstinting with bribes, refusing to become intoxicated by victories, refusing to lose heart after defeats, stepping across millions of soldiers’ corpses and at least one tsar’s corpse—this gang is as unscrupulous as it is talented, and has done more than all the Russian armies to expand Russia’s borders from the Dnieper and the Dvina beyond the Vistula, to the Prut, the Danube, and to the Black Sea, from the Don and the Volga beyond the Caucasus, to the sources of the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya. It has made Russia great, mighty, and fear-inspiring, and has opened its way to world domination” (see Engels’ above-mentioned article).

One might think that in the history of Russia, in the history of its foreign relations, diplomacy was everything, and tsars, feudal lords, merchants, and other social groups were nothing, or almost nothing.

One might think that if Russia’s foreign policy had been led by Russian adventurists such as Gorchakov and others, rather than foreign adventurists such as Nesselrode or Girs, Russia’s foreign policy would have taken a different course.

Never mind the fact that an expansionist policy with all of its abominations and filth was by no means the monopoly of Russian tsars. Everyone knows that an expansionist policy was also associated—at least as much, if not more—with the kings and diplomats of every country in Europe, including an emperor in a bourgeois mold such as Napoleon, who, despite his nontsarist background, successfully practiced intrigue, deceit, perfidy, flattery, atrocities, bribery, assassinations, and arson in his foreign policy.

Clearly, it could not have been otherwise.

In his criticism of Russian tsarism (Engels’ article is a good piece of militant criticism), Engels evidently was somewhat carried away and, once carried away, he forgot for a minute about some elementary facts that were well known to him.

2. In describing the situation in Europe and analyzing the causes and portents of the approaching world war, Engels writes:

“The present-day situation in Europe is defined by three facts: 1) Ger many’s annexation of Alsace and Lorraine; 2) tsarist Russia’s yearning for Constantinople; 3) the struggle between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie, which is growing hotter and hotter in every country—a struggle, for which the ubiquitous upsurge of the socialist movement serves as a thermometer.”

“The first two facts account for the present division of Europe into two large military camps. The annexation of Alsace-Lorraine turned France into an ally of Russia against Germany, and the tsarist threat to Constantinople is turning Austria and even Italy into an ally of Germany. Both camps are preparing for a decisive struggle—a war such as the world has never seen, a war in which 10 to 15 million armed warriors will face one another. Only two factors have until now prevented the eruption of this terrible war: first, the unprecedently rapid development of military technology, in which every newly invented type of weapon is overtaken by new inventions before it can even be introduced in a single army, and second, the absolute impossibility of calculating one’s chances, the complete uncertainty as to who will ultimately emerge victorious from this gigantic struggle.”

“This entire danger of world war will disappear the day when affairs in Russia take such a turn that the Russian people are able to do away with the traditional, expansionist policy of their tsars and, instead of fantasies of world domination, pursue their own vital interests inside the country, interests that are threatened by extreme danger.”

“. . . The Russian National Assembly, which will want to deal at least with the most urgent internal tasks, will have to decisively put an end to any efforts toward new conquests.”

“Europe is sliding with increasing speed, as though down a slope, into the abyss of a world war of unprecedented scope and force. Only one thing can stop it: the replacement of the Russian system. That this must occur in the next few years is beyond all question.”

“. . . On the day tsarist rule, that last bastion of European reaction, falls, on that day a completely different wind will begin to blow in Eu rope” (ibid.).

One cannot help but notice that in this description of the situation in Europe and the list of factors leading to world war a very important point is omitted that later played a decisive role, i.e. the imperialist struggle for colonies, for markets, and for sources of raw materials, which was already of extraordinary importance then; it omits the role of England as a factor in the coming world war, and the conflicts between Germany and England, conflicts that were also of substantial importance and that later played an almost decisive role in the outbreak and development of the world war.

I think this omission is the main shortcoming of Engels’ article.

This shortcoming leads to other shortcomings, of which the following should be noted:

a) An overestimation of the role of tsarist Russia’s yearning for Constantinople in paving the way for the world war. True, at first Engels judges Germany’s annexation of Alsace-Lorraine to be the leading war factor, but later he relegates that aspect to the background and gives priority to the expansionist ambitions of Russian tsarism by asserting that “this entire danger of world war will disappear the day when affairs in Russia take such a turn that the Russian people are able to do away with the traditional, expansionist policy of their tsars.”

This is, of course, an exaggeration.

b) An overestimation of the role of the bourgeois revolution in Russia and the role of the “Russian National Assembly” (the bourgeois parliament) in preventing the approaching world war. Engels asserts that a collapse of Russian tsarism is the only means of preventing a world war. This is an obvious exaggeration. A new, bourgeois system in Russia, with its “National Assembly,” could not have prevented the war, if only because the mainsprings of the war lay in the realm of the imperialist struggle be tween the principal imperialist powers. The point is that ever since Russia’s Crimean defeat (in the 1850s), the autonomous role of tsarism in European foreign policy began to decline significantly, and by the time the imperialist world war drew near, tsarist Russia was essentially playing the role of an auxiliary reserve for the main European powers.

c) An overestimation of the role of tsarist rule as “the last bastion of European reaction” (Engels’ words). The fact that tsarist rule in Russia was a powerful bastion of European (as well as Asian) reaction cannot be disputed. But that it was the last bastion of this reaction—this is a matter of doubt.

It should be noted that these shortcomings in Engels’ article are not only of “historical value.” They were, or should have been, of great practical importance. Indeed, if the imperialist struggle for colonies and spheres of influence is disregarded as a factor in the approaching world war, if the imperialist conflicts between England and Germany are also disregarded, if Germany’s annexation of Alsace-Lorraine is minimized as a war factor in comparison with the yearning of Russian tsarism for Constantinople, which is depicted as a more important and even decisive war factor, if, finally, Russian tsarism represents the last bulwark of European reaction— then isn’t it clear that, say, the war of bourgeois Germany against tsarist Russia is not an imperialist war, not a predatory war, not an antipopular war, but a war of liberation or almost a war of liberation?

There can scarcely be any doubt that this way of thinking must have contributed to the betrayal by German social democrats on 4 August 1914, when they decided to vote for military credits and proclaimed the slogan of defending the bourgeois fatherland against tsarist Russia, against “Russian barbarism” and so forth.

Characteristically, in the sections of his letters to Bebel in 1891 (a year after Engels’ article was published) that dealt with the prospects of imminent war, Engels says outright that “victory for Germany, therefore, is victory for the revolution,” that “if Russia starts a war, then onward against the Russians and their allies, no matter who they are!

It is clear that this way of thinking leaves no room for revolutionary defeatism, for the Leninist policy of transforming the imperialist war into a civil war.

Those are the facts with regard to the shortcomings in Engels’ article. Engels, alarmed by the French-Russian alliance that was being formed at the time (1890–1891) and was aimed against the Austrian-German coalition, apparently set himself the goal of attacking the foreign policy of Russian tsarism in his article and stripping it of any credibility in the eyes of public opinion in Europe, and above all in England. But in pursuing this goal he overlooked a number of other highly important and even crucial points, which resulted in the one-sidedness of the article.

After all of the foregoing, is it worthwhile to print Engels’ article in our militant organ, Bolshevik, as a source of guidance, or at any rate as a profoundly instructive article, since it is clear that printing it in Bolshevik is tantamount to tacitly giving it precisely this kind of recommendation?

I don’t think it is worthwhile.

I. Stalin.

19 July 1934.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

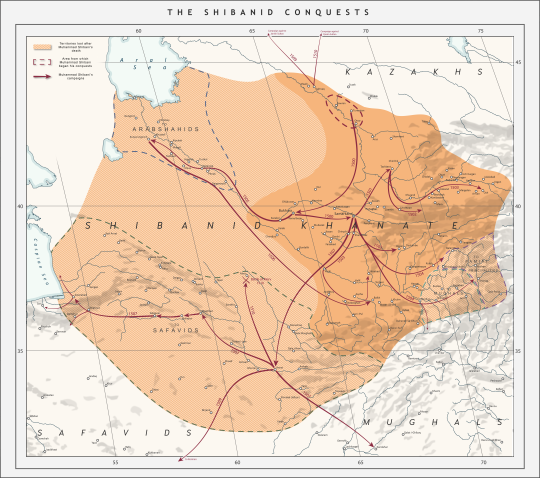

The Shibanid (Shaybanid) Conquests, 1500-1510.

by u/Swordrist

This is my attempt at covering an underapreciated area of history which gets next-to no coverage on the internet. Here's some historical context for those uneducated about the region's history:

Grandson of the former Uzbek Khan, Abulkhayr, Muhammad Shibani (or Shaybani) was a member of the clan labeled in modern historiography as the Abulkhayrids, who were one of the numerous tribes which were descended from Chingis Khan through Jochi's son, Shiban, hence the label 'Shibanid' which is used not only in relation to the Abulkhayrids who ruled over Bukhara but also for the Arabshahids, bitter rivals of the Abulkhayrids who would rule Khwaresm after Muhammad Shibani's death and for the ruling Shibanid dynasty of the Sibir Khanate.

After his grandfather's death in 1468, Shibani's father, Shah Budaq failed to maintain Abulkhayr's vast polity in the Dasht i-Qipchak, as the tribes elected instead the Arabshahid Yadigar Khan. Shah Budaq was killed by the Khan of Sibir and Shibani was forced to flee south to the Syr Darya region when the Kazakhs returned and proclaimed their leader, Janibek, Khan. Shibani became a mercenary, serving both the Timurid and their Moghul enemies in their wars over the eastern peripheries of Transoxiana. After the crushing defeat of the Timurid Sultan Ahmed Mirza, Shibani succeeded in attracting a significant following of Uzbeks which formed the powerbase from he launched his conquests.

Emerging from Sighnaq in 1499, Muhammad Shibani captured Bukhara and Samarkand in 1500. In the same year he defeated an attempt by Babur (founder of the Mughal Empire) to take Samarkand. Over the course of the next six years, Shibani and the Uzbek Sultans conquered Tashkent, Ferghana, Khwarezm and the mountainous Pamir and Badakhshan areas. In 1506, he crossed the Amu-Darya and captured Balkh. The Timurid Sultan of Herat, Husayn Bayqara moved against him however died en-route and his two squabbling sons were defeated and killed. The following year he crossed the Amu-Darya again, this time vanquishing the Timurids of Herat and Jam and subjugating the entirety of Khorasan east of Astarabad. In 1508, he raided as far south as Kerman and Kandahar, however he moved back North and launched two campaigns against the Kazakhs, but the third one launched in 1510 ended in his defeat and retreat to Samarkand at the hands of Qasim Sultan.

The Abulkhayrid conquests heralded a mass migration of over 300 000 Uzbeks to the settled regions of Central Asia from the Dasht i-Qipchak. They heralded the return of Chingissid political tradition and structures and the end of the Persianate Timurid polities which had dominated the region for the last century. It forever after changed the demographic of the region. His reign was also the last time Transoxiana was closely linked with Khorasan, as following the shiite Safavid conquests the divide between the two regions would grow into a permanent one.

In 1510, Shibani faced his end when he moved to face Ismail Safavid, who was making moves on Khorasan. Lacking the support of the Abulkhayrid Sultans, who blamed him for their defeat against the Kazakhs earlier that year, he faced Ismail anyway, where he was defeated, killed and turned into a drinking cup.

Shibani's death caused a complete reversal of the Abulkhayrid fortunes. Khorasan and the rest of his empire fell under Safavid dominion. However in Khwaresm, Sultan Budaq's old rivals the Arabshahids expelled the qizilbash and founded their own Khanate, based first in Urgench and then Khiva. In Transoxiana, Babur lost the support of the populace when he announced his conversion to Shiism and his loyalty to Shah Ismail, which allowed the Abulkhayrids to rally behind Shibani's nephew, Ubaydullah Khan and expel the Qizilbash. Nonetheless, the Abulkhayrids would never again hold as much power as they briefly did when led by Muhammad Shibani Khan.

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chapter 5 is up!

Apologies to anyone who was waiting…I’m a day behind with my update.

Welcome to my original character! I love him so much, so I hope y’all will too. I wanted a perspective that I thought had been missing — the Lesser Fae needed a voice. And there needs to be an outsider’s view of Velaris/HC as well. Lucien has a bit of it, but he’s all bound up with Elain and the IC, plus he’s an aristocrat.

I know this won’t be as interesting to most people as the characters you already know and love, but hopefully you’ll start seeing how all of these braid together. Thanks for reading, as ever! We’ll be back to more familiar territory next week: Elain, and a Solstice party.

TW: description of torture & graphic violence

Chapter 5: ANDHAL

TWO DAYS BEFORE SOLSTICE

Staring up into the recesses of the cliff face, it occurred to Andhal that the Hewn City looked as though it were a gargoyle come to leering, menacing life.

And then, with a grim chuckle, he wondered if the journey from the Windswept had scrambled his brain. It certainly had been cold enough to freeze the blood and turn it sluggish. But two days before Solstice, how else should it feel, he supposed.

He led Bagal and the sledge she dragged, gently pulling her bridle down the pathway toward the entrance, flanked by onyx pillars busy with carvings, probably representing gods and nightmares and all other things High Fae used to lord themselves into believing they were better. The gray mule balked briefly but then acquiesced, clearly hoping for hay and a warm stall in which to sleep. Andhal stroked her neck gently and offered her the last of the dried lingonberries he had brought to entice her to walk all this way. She accepted them with a toss of her head and a glance over her long nose. Is this all? she seemed to say. He tapped her nose and winked at her. You had to be sly with mules. They had something of a sense of humor.

Andhal supposed that if he were trying to be fair, the beauty here was not intended for his consumption. He was partial to the rough magnificence of the open fields that rustled just above the treeline of the steep but beautiful range that clustered near the border with the Day Court. The High Fae had named them Amu Darya, the dark hills. Andhal fancied that whoever had written that on the map had never actually seen them. His people didn’t call them that, just Cyreia — sisters of the sun. Simple, but glorious, especially when the sun embraced the ridged horizon, whether rising or setting. The fingers of light stealing over the border between night and day turned the world into a gleam of glory. Even in the darkness for which the Night Court was renowned, the pyrite ore in the hills gleamed under the stars, heavenly beneath the feet until you couldn’t tell what side was sky and what was stone. And the Zemeistan, the Windswept, the grassy meadows that yawned up their sides, spilling clover and buttercups and poppies from valleys to peaks, scarlet and gold in the dawn’s fond gaze, could never be less than magnificent. This place, however impressive, seemed overdone by comparison. Ostentatious.

Bagal stopped with a wheeze and dug her hooves in. He tugged her gently forward again, and hummed for her under his breath.

Winds carry worries away, away

And waters will ease the heart’s pain

So find me a field at the edge of the world

I’ll be happy the rest of my days.

It was his mother’s favorite tune. He’d sung it more and more often since her funeral. As a younger male, he’d always scoffed a bit at sentimentality — it didn’t till the fields, hunt the hares, keep the Dul’ahan at bay, or feed the mouths — but now, a couple hundred years under his belt and a loss or two removed from childhood, he realized it was necessary. Survival wasn’t enough to make a life.

But it was paramount. Hence his presence here at the Great Goblin Temple. Andhal almost laughed aloud at the thought, and stored it away for later use. If you had to pay feasance to lords and ladies, it helped to bow with mischief ribboning through your mind. Made it easier. Less humiliating.

“You there! Stop!”

Andhal slowed to a halt before the bridge that loomed over the precipice, marking the entrance to the Hewn City. The guards came forward with their ash spears angled toward him. He raised both hands and bowed his head in a show of respect. They were twisted, dark creatures; strong, and lithe, but heavy, stocky, mundane. Andhal thought true nightmares were ones that existed at the edge of consciousness, fueling fears with reality, but gone as soon as you turned an eye to look. Never visible, but always there.

“State your business,” the leading goblin muttered in a voice that sounded like gravel on a grate.

Andhal lifted his head and smiled at them, adjusting his posture into an unthreatening slump. He was a tall male, taller than most of his people, and if he pulled himself up to his full height, he would stand at least a handspan above even the tallest of the High Fae. He’d learned early to disguise himself in affability, like a cloak. “End of year tithe, and an audience with the High Lord, if he has the time,” he said, pleasantly.

The ash spears lifted and the nightmare-guard grunted. “Where is your freehold?”

Andhal knew it was useless to correct them; no one in the cities understood that settlements of the Windswept weren’t built of bricks or mortar or wood. So, as was his custom, he gave the name of the nearest town. “Lariat, sir.”

The guard snorted. “The borderlands.” He stared Andhal up and down and then motioned him to pass, a leer on his face. Andhal inclined his head and tugged Bagal forward across the black malachite cobblestones. He’d made it almost all the way past the group of guards when he heard one of them sneer, “Dirtback.”

Heat spiked through Andhal’s core and up his neck. Less than thirty seconds into their company, and he’d already been insulted. He turned, and raised himself up, imagining pulling a string above his head and stacking his vertebrae in a column of steel. He threw hay bales all day, bound and strapped up tents for the trips up and down the mountainsides, rolled down mountain screes to catch sheep stranded on shale cliffs, trained with the sling and bow on the rest days until his shoulders ached. Let them see him, then. For everything he was. Dirtback, indeed.

The guard looked up at him, face slackening.

Andhal held his gaze, letting the silence stretch into a heavy meaningful weight, and then turned slowly, and strode into the city with his head held high. Your kind of nightmare was my childhood fear. I kill Dul’ahan, who are sent to steal children and burn crops and drink blood. Let intimidating me fall to your bigger, scarier friends.

He saw to it that Bagal was calmly ensconced in a stable, chewing on alfalfa, before he took his place in the line of supplicants who came to ask the High Lord’s favor. He had a gold mejuri — a thick medallion — that his settlement had banded together to afford, with the likeness of a Dul’aha on the front, teeth bared into razor-sharp spikes, huge flat eyes unblinking. He hoped it was eye-catching enough to keep Rhysand’s attention, even amongst all the gleaming luxury. In the council where they’d commissioned it, imbued it with the magic of the bargain sacred to all the Fae, brought it into being with words and pleas and anguish, it had been glowing, gorgeous. Somehow, it seemed smaller and sadder here.

If they do not address our concerns, then what will I do? I can’t go home without a plan.

He had left the settlement en route to Lariat, en route to a tribal council, hopeful that the greater numbers present at the fires would dissuade the attacks. But he had no way of knowing if they’d all made it.

I must trust in my people and their good sense.

His father had taught him that when you were called to protect and lead, that it was to serve others and not yourself. That more could be done as a group than alone, and at times, the hardest way forward was to trust.

But it’s not my folk I do not trust, Andhal argued with himself. It’s the blood monsters that track them.

More and more frequently, Dul’ahan had been appearing on the hillsides. The monsters were dark and unkempt and hungry, and usually settled for stray sheep or goats, despite their storied taste for fae blood.

But when they had lost the child, it had become far more urgent.

Andhal had killed the offending Dul’aha himself, and brought its body back to the little boy’s mother. He would never forget her face: frozen, no feeling at all, until the council fire took the Dul’aha’s body, and it released her tears. She had screamed on her knees at the edge of the flames, her hands outstretched, hair wild, restrained by her husband’s arms from throwing herself in. And shadows at the edge of the pyre had moved with purpose, seeking out the scent of blood and flesh. His people had drawn closer, pulled their own weapons, prepared to sell their lives as dearly as they could. Andhal had seen Jamila, his brother’s wife, draw a scimitar, test its weight in her slender hand, and angle it out at the shadows, her back straight and eyes clear. Andhal been so terrified for all of them, and so desperately proud that his throat had knotted closed; he’d known in that moment he would have to seek the High Lord’s help.

We have never asked for more than basic safety, he reassured himself. Lord Rhysand could clear those hills of the creatures without any serious drain on his power. It will not be an imposition on his abilities. And I have a token to mark the bargain.

Please let it be enough.

Then he could go home, and tend the fields, where they grew alfalfa next to wildflowers and wheat alongside heather. Tend the wild beehives at the edges of the cliffs, dripping with honey in the mountain summer. Travel down mountain in the winter to stay warm and live off their stores. Maybe marry, one day, and be blessed with faelings of his own. Protect his people until his final day, when the Mother called him back over the horizon.

But first…

He stared at the dark obsidian tile, polished to glassy slickness that reflected the white faelights from above in a ghostly gleam. His eyes were getting heavy; he had sped up the travel today, hoping to arrive before dark, and hadn’t had a chance to sleep before coming down to the audience chamber. The other fae, mostly the kind the High Fae called “lesser,” sat on the long stone benches in haphazard groups, talking to one another animatedly. There were some green-skinned dryads, a few whose wings were thickly feathered like ravens, and some who had speckled pale skin and great clouds of whitish-gray hair that resembled nothing so much as clouds. He recognized a few nightlarks, who lived in the same mountains Andhal did; they kept to the cliffsides and the air, their buzzing wings, which opened telescopically on their backs like carapaces, preventing them from falling to their deaths in the valleys. Their lore said the Illyrians had killed most of them in the northern mountains, but as the warriors didn’t venture out of the Steppes unless it was on the tide of war, the nightlarks were mostly safe in the Amu Darya. Their midnight blue skins blended well with the obsidian and the shadows. If he directed his gaze straight ahead he almost couldn’t see them at all, just silhouettes against the stone. Andhal would have nodded in their direction but his eyes…were so heavy…

He started, head falling forward, waking up in a shock.

I can’t fall asleep. I can’t miss them calling my turn.

He stood, and stretched, his long form towering above the others. Another fae on the bench nearest him caught his eye and grinned lopsidedly. “Not been waiting long, have you?”

Andhal shook his head. “Not long. Just a lengthy journey to get here.”

“Where you from?” The fae had silvery-gray skin and eyes so pale they were almost white. The pupils looked absurdly small in the middle.

Andhal hesitated; he did not like sharing his life with other travelers as a general rule. But with his burnished skin, crackled with gold in the sunlight, and the shadows he could draw over himself to stay hidden in the magnificent starlit expanse of the Night, he didn’t know how anyone would mistake him for anything but a mountain fae. “From Lariat.”

The fae squinted and said, “Didn’t think mountain fae spent much time in towns.”

Andhal inclined his head. So this one knew some of the customs. “Not much,” he agreed.

“I’m from the eastern islands,” the fae said with a disarming smile. Andhal couldn’t help flaring his nostrils, but it didn’t help; he couldn’t tell if the fae was male or female, by sight or scent. Perhaps it was a bit of both; Andhal had heard of such things. Their scent was pleasant, a bit brackish, like fog over the ocean. “And you’re here for the tithe?”

Andhal nodded.

“I brought six barrels of the finest salt as a gift,” the fae said proudly. “Preserve anything, that will. Or flavor it perfectly. I brought the High Lord a box of our caviar too.”

Andhal’s mind stirred uncomfortably. Only a few tribes had special dispensations to pay tithes in anything other than gold; people like his, who grew grain that could be processed and used for food. The city folk said the food tithes went to feed the hungry, but from the infrequent visits of the Velaris government to the surrounding territories, who beat away hunger with both hands on a weekly basis, Andhal suspected it was less the starving masses than the hungry soldiers in the Night Court army. Gifts at the tithe were meant for one thing only: to sweeten the request for a boon. Was Lord Rhysand going to be amenable to granting multiple requests?

It’s to ensure our safety, he reminded himself. It’s his responsibility, as our caretaker.

But an additional skein of worry wound around the already-present twist in his gut.

“How long have you been waiting for your audience?” he asked the islander.

Their face fell. “Three days.”

Andhal had to clench his fist to keep from gasping in shock. Three days? How long had all of the supplicants been waiting?

The islander shrugged and said, with rather more optimism than Andhal might have retained after three days in an audience chamber, “I hear he’s busy with the High Lady. That they’re getting ready for solstice. It’s her birthday, after all. Perhaps there’ll be a party.”

Andhal felt the edge of his vision blur with red. Mother save me. A birthday party for the High Lady. Well, I hope a Dul’aha doesn’t show up to her hearth. He stretched, trying to pull the fatigue from his sore arms and legs. Perhaps he should check on Bagal. Or try to find something to eat. Surely even in this temple of nightmares, there was food?

“Would you like something to eat?” he asked the islander, hesitantly. “If they’re taking their time with the tithe, it might be a while, and I could use some food.”

The islander shook their head. “I’m well. If you’re leaving I’ll watch your place. But don’t get lost—” their white eyes gleamed mischievously, “—else we’ll be sending a goblin guard to come find you in the hellpits of this place.”

Andhal laughed, and extended his hand. “If I’m not back in an hour, send the goblins after me. I’m sure their type of nightmare is preferable to being stuck in a hellpit.”

They shook, and the islander said with a shrug, “oh there’s all kinds here. The nightmares you can dismiss and the ones you can’t. I’ve heard screams in the dark for at least a day now. Dunno where it’s coming from. But it’s all around us when it happens. Anyway, if you want a decent stew — not as fresh as I’m used to but it’ll do in a pinch — there’s a stall two levels down run by a friend, Loren. She’ll get you fed.”

Andhal nodded and made for the exit. He heard the fae shout after him, “Oyo, what’s your name, friend?”

He turned and called, “Andhal,” back across the crowd.

“See you in a bit, Andhal,” the islander waved. “Ask for Bindi if I’ve made other friends by the time you get back.”

Andhal chuckled and slipped between the pillars that marked the entryway. Two levels down, he thought, striding forward, bootheels ringing against the floor.

The Hewn City was cut into the rock in spirals, shooting deep inside the mountain with cross-paths and tunnels that crossed in a mind-melting labyrinth, but overall a massive circular winding pathway that led past stately homes fashioned from the stone itself. The streets were wide enough to hold multiple stalls for food and other conveniences, but many of the business providers used wheeled carts to move along to better stations at busier traffic times. It was fairly late in the day, so not many were left; but a few still had wares to sell.

Andhal felt in his pockets for the few coins he’d brought. It wouldn’t buy much. But enough to briefly sate his hunger.

He wound around the side of the mountain, so unlike and yet so similar to his beloved home.

He had made it down one full circle when he saw the youngling.

She was dark skinned, a dusky blue-black dotted with tiny silver speckles that kept her concealed in doorways and shadows, but would also make her impossible to see in an open area, under a swath of stars. Her dark hair, riotous and curly, twisted into thick skeins. As he watched, the locks of hair wrapped around her head, flattening against the wall to blend beautifully with the angles of shadows in a city. Andhal supposed her ability to hide was aided by a natural slight stature, but he couldn’t help but swallow hard at how skinny she was — to the point that her belly curved in away from her ribs — and angular, with her joints larger than the arms and legs they held together. He was aghast. He was used to seeing hungry people in the countryside, but…they let children starve in the Hewn City? Home of the highest of High Fae, blessed with generations of wealth and magic?

He stepped further, and she noticed him, then turned and blended into the shadow of a doorway, leading down a darkened corridor. She must have come from inside the mountain, he realized. He looked for a timepiece, but saw none close by. Had it been an hour yet? Would Bindi keep to their word and send someone after him?

He couldn’t see the little ghost, the little shadow…had she run off?

A little squirm of movement caught his eye, recessed a bit further down the passageway. Andhal leaned into the doorway, stooping so his big shoulders would fit. He squinted. He knew shadows; he could use them to hide himself. But this little thing; she could disappear completely into them.

“Hello,” he said, cautious, hoping it wasn’t a lure for other little ones to come out and rob him. Andhal was fairly confident he could fight off even a group of little ones, but should they steal his precious mejuri, or his coin? Then he’d be helpless in a foreign, hostile city.

The shadow stirred; he saw bright eyes shine at him, briefly, before winking back into invisibility.

“Are you lost?” he asked.

No movement.

“Where is your home? Your mother, father? Your family?”

No movement. Andhal somehow felt certain that meant she had none.

He sighed, suddenly inexplicably sad. Everywhere there is loss, and sadness, and misery. He stood up, muscles shifting under his skin, that gleamed where it caught the light. He should leave. He had a purpose. A mission. And before that, he had a hunger in the belly to quiet.

But something nagged at the back of his neck. A tiny voice in his mind. There is always time, it said sternly, always time to be kind.

Ah, Mother, he thought sadly. This little creature would be one of your lost little folk. He pictured her at the council fire, telling stories to their faelings, chuckling when they fingered the fringe on the blue of her skirt, opening her arms for snuggles and comfort when they got frightened by the bards’ folk tales. He had been an orphan too, long ago as a youngling, and she had comforted him at the council fire, and later taken him home to food and warmth, to raise him in her house to be an elder of the tribe. When he got jealous of the others who swarmed her for attention, she would cup his face gently in her hands. My lovely boy, she had said. Your heart is always full. You have great strength. Share it, for there is always time to be kind.

Andhal blinked swiftly against the stinging in his eyes, and nodded to himself.

“I’m going to get some food,” he said, keeping his voice as light as he could. “If you like, you could share with me?”

There was no movement. Andhal almost cursed his own stupidity; but then he saw the shadow move again. Her tendrils of hair crept up the wall, hands sleek and dark against the stone, and froze as she caught his eye.

Maybe she is a nightmare herself, Andhal thought, and powerful enough to put a geas on anyone foolish enough to challenge her.

But the little shadow crept just a tiny bit closer, and in the darkness he saw the gleam of her eyes.

He stood up and walked off down the street, keeping close to the houses to give her space to hide. It became like an odd sort of game; hide and not-seek, instead of hide and seek. He let her follow him around the side of the mountain, stopping only to briefly take in the view of the mountains yawning up into the fading sky. It was a beautiful sight. Forbidding. But beautiful.

He found Loren, loud in conversation with her cashier, who indeed admitted to knowing Bindi and gave Andhal an extra bread roll and an extra scoop of fish stew into a paper bowl. She waved him off when he tried to give her extra coin. “Just tell that little fucker Bindi that they owe me a hug and four silver sous the next time they drag their skinny arse down here,” she snickered. “Now get gone. Don’t want to be missing when they call you for the tithe.”

“There isn’t a way to get back up faster, is there?” Andhal thought it might take easily an hour to climb the circling street back to where he started.

“Cauldron yes,” she laughed. “But it’s a steeper way, and you can’t see the mountain to tell you where you’re going.”

Andhal drew himself up and let the golden crackles on his skin shine. She raised an eyebrow. “Mountain fae, eh?”

He smiled. Maybe he’d change his mind about keeping to himself. It was a much better trip when you found real folk to talk to.

“Well, all right then, since you’re used to steep slopes and all.” Loren waved a hand toward a narrow doorway. Andhal looked, and the shadow at the side of it writhed just a little. Very well, so perhaps his little nightmare knew the way too.

“Many thanks,” he said, offering the extra bread in his outstretched hand as he leaned into the steeper slope of the passage. It only took a moment for her to snatch it from him, and he heard the wolfish sound of her tearing into it. “Stars above, little one. You should eat slower or you’ll make yourself sick.”

A flash in the darkness. She had rolled her eyes at him. He laughed, and dug into the stew. It was hearty, stocked with fish and plenty of potatoes, and thickened with cream. For a moment, the two of them ate in content silence, the only sounds the scrape of a spoon or the crisp crackle of a crust. They made slow progress, distracted by their food.

The long hall wound on and on, steeply rising in places, in others cut with uneven steps. Andhal handled the path expertly, but found it to be much longer than he had expected. Hopefully he would come out at the peak of the mountain, at the rate they were climbing. The little nightmare slid along nimbly behind him. They rose up a few more feet, only to see a split in the hall. Both turns led upward at odd angles. He stood and examined them for a moment.

“Do you know which way will get me back to the audience hall?” he asked. The little nightmare pressed back against the wall. Andhal felt a twist of unease. He glanced backward down the steep hallway, wondering if he shouldn’t have followed Loren’s advice after all; but now it was too far to go back, and would take far too long.

He stared ahead, and then shrugged. When the road diverges, make your choice and go on, he thought. There are too many unknowns to be worrying about.

With a sigh, he chose the left path, and climbed further up; the path narrowed significantly so it was only wide enough for one. There was a tentative tap at the back of his knee. He turned to see the little nightmare, pressed against the wall, closer than she’d been before. Her locks of living hair waved with anxiety. Was she…afraid?

“Did I go the wrong way?” he asked.

She gazed back down the tunnel.

“It’s too late now,” he said. “Must press onward. Too long to go back down and around.”

She flattened herself further to the wall.

“Are you going to stay here?” She remained still, a tiny dark silhouette on the stone wall. She seemed frozen, although he couldn’t tell if it was with stubbornness or fear. Perhaps both, he thought uneasily.

“Well. Then it was nice to meet you, little one,” he said, and turned to climb onward. “Be careful getting home, wherever you live.”

He put out both his hands to brace against the walls, then kept climbing. There was a curious stretching effect, like every step was costing him four steps’ effort, or like he had weights attached to his wrists and ankles.

Stars save me, he thought, eyes peering through the murky light. What manner of place is this?

The path leveled out briefly, and then to his left, part of the curved tunnel ceiling fell away, as though it were a sort of balcony. He came up to it and stared downward into a vast dark chamber. There were soft noises coming from recesses in the walls; sighs, sobs like the tearing of cloth.

Andhal slid backward toward the solid wall. If anyone was patrolling this place, he didn’t want them to find him.

And then, the screams began.

They were ragged, rough, as though the throat from which they issued had been screaming for a long time. They swelled with panic, with pain, then collapsed into sobs. The sound was wrenching. He’d never heard anything so desperate. It pulled tears from his own eyes to listen to it.

Andhal dropped down to the floor of the tunnel and reached for a shadow at the ledge, then pulled it over himself like a blanket. The screams went on and on, hacking the silence into jagged pieces that throbbed in his ears. He remained still for only a moment before fear galvanized him and he turned around to run, making it a full ten cubits before a wall of darkness blocked his path. It was a black so deep he thought that if he reached into it, his very flesh would melt into nothing. He was used to darkness, the normal kind…not this, this nothingness, which could easily be the border between worlds. The screams rolled on and on behind him, paralyzing him; would he have to leap into oblivion or be dragged back to be cut apart by whatever nightmare was inflicting such horrible pain?

When they finally stopped, taking a full minute to die, there were soft words being spoken. The echoes magnified them as they climbed the walls, so it sounded like the speaker, despite being a full fathom below Andhal, sounded as if he were right next to him.

“Are you telling me you don’t know anything more, witch?”

The sobs continued, thick and wet.

“You were the only one to assault the Archeron lady? There were no others?”

Andhal rolled to the ledge and lifted up very slightly onto his elbows. He peered into the depths of the chamber, until he made out an obsidian-dark ledge over a yawning chasm that extended all the way down into the mountain’s heart. In the sudden quiet, he could only hear the distant drip of water onto stone.

“No others? Or aren’t you feeling talkative today?” the voice said again, relaxed and gentle and all the more cruel for its softness. Andhal saw something move on the dark stone ledge; a silhouette.

Fae? Or nightmare?

It was oddly shaped, with two great crescents of darkness at the back. As it moved, Andhal let the breath slide from him in terror.

The great dark crescents were wings. Massive skin wings.

An Illyrian. Stars save him; he was caught under the Hewn City with an Illyrian.

There was a gleam of a blade, and a wet cough from the rock wall. Andhal squinted; he could just make out a figure, caught in iron chains, suspended above the rock ledge. It had a curious green gleam.

“Then, let’s discuss this magic of yours,” the Illyrian continued. “It seems to create a vacuum into which other magic is absorbed, if I am correct. What did you take from the Archeron lady?”

The chains clinked as the figure twisted. Her arms and legs, illuminated in a sickly glow by the green light faintly emanating from her torso, looked…odd. They were overly long, prisoned by shackles at the upper arm and the wrist. The shackles gleamed wetly under the pulse of green light. Her arm…her arm was cut almost to ribbons, skin hanging down in drapes, no longer connected to her muscles. The dull white of bone was exposed, and dark fluid dripped in a slow, curving stream from her arm down onto the rock. She squirmed, the looseness of shackles at her neck and torso allowing her minimal movement, but her arm stayed still, pinioned immovably to the stone wall. Andhal felt his gorge rise, and despite the goosebumps that rose on his arms, he felt beads of sweat slide down his temple. He had seen many creatures strung up like this. Flayed. Prepared for butchering. His eyes swam, and he noticed with a start that there were multiple shadows that were behaving…oddly. The sinuous ribbons of them twirled around the stalagmites and rock formations, whispering in chittering little voices.

But shadows were not sentient.

“What did you take from her?” the Illyrian asked again. He seemed broad, powerfully built. Andhal wondered if he was merely a jailer or if he was a warrior. The warriors were dark and terrifying. A different kind of brutal than their untrained counterparts. He knew them from tales of old, stories of them descending like dragons on the fields of the Windswept, murder in their eyes, slicing down his people in cold blood, using their cursed shimmering siphons to blast craters into the ground so there would be nothing salvageable…nothing salvageable…

“N…nothing, my lord,” gasped the creature in the chains. “Please…”

“I’m not a lord,” the Illyrian said, angling his knife upward toward the creature’s pinioned arm. “And I think you’re lying to me.”

“No,” the creature sobbed, her voice fracturing.

“Only one way to know, is there?” the Illyrian spoke. Lightly, as if discussing the weather. He slid the blade up against the creature’s hand, as she shook her head violently in panic…

Screams split the darkness again, sending the odd shadows roiling in distress. Andhal felt a tug on his boot and whirled, ready to kick; but it was his little nightmare, crouching next to the ledge. She beckoned him back toward the tunnel. Come with me, she seemed to say. This isn’t safe for you.

No shit it isn’t, Andhal wanted to shout. But the screams were pulsing through his head again. He couldn’t think; he squeezed his eyes shut tight. He felt an urgent patting on his arm. She was telling him, now. You must come now.

He pulled himself together as much as he could, fighting sobs from escaping his throat, and followed her toward the dark-cloaked door. The little nightmare stopped, her hair locks creeping forward; Andhal watched her. She seemed to be considering the doorway like a railway timetable. She put up her fingers. Four.

There was a swirl of dark blue inside the dark curtain. She put one finger down. Three.

Sparks appeared in the darkness, bravely bright, but fading almost immediately. One more finger down. Two.

He was getting more and more agitated as the screams continued. Now they were laced with the Illyrian talking. “Scream louder, witch. We have an audience.”

Andhal’s eyes went wide. Had the warrior seen him somehow?

The little nightmare stared fixedly at the dark curtain, which undulated like a physical piece of cloth. She put another finger down. One.

Andhal turned, looking back toward the balcony, and saw a spiraling shadow wriggling along its railing. Shadows don’t see, he tried to comfort himself. They sit in crevices. They cover us when we need to hide.

But this one…this one seemed like it could. A whispering noise came from it. A chittering, a clicking, like the sound of nails tapping on rocks…it was telling something where it was, what it was seeing…

The little nightmare blew forward with all the strength in her tiny body, and the darkness streamed outward. Beyond it was the tunnel; narrow, dark, dank, but normal. Or as normal as anywhere in this terrible place could be.

She seized his hand and pulled. He darted forward, and felt a whirring around him as the opening - not a true curtain, more like a doorway between the shadows - contracted closed. He felt her drag him in front of her, and then she pushed him. Hard.

He landed on solid stone, cracking his knee hard against the floor. He curled up like a child, finally letting the sobs break free. A court of nightmares indeed.

Nightmares.

Where was his little nightmare? She had gotten him out. She seemed like just a child. Had she seen these terrible things before? How had she known where to go, and how to get back?

He looked back toward the dark curtain, expecting to see her crouched against the wall. All he saw was a slab of sharp obsidian rock.

She was gone.

Andhal felt panic rise in him like the tide. She was now trapped in there, with those sentient shadows and that cruel…that warrior, who knew how to torture, whose calm voice betrayed that he had done it before even as the very darkness trembled with disgust around him.

He pressed his hands against the stone, faintly feeling echoes of the screams still trapped inside. Not a place for anyone, he thought, frantic. Not a place for a little one.

He scratched at the stone. It tore his nails. He beat it with his fists. It bruised his hands.

Finally, his eyes aching with tears, he pressed his forehead against the wall, and made a promise that he hoped echoed into that dark chamber.

I will come back. I will find you. Stay alive until then.

And feeling as broken as he ever had in his lengthy Fae life, Andhal stumbled back down the tunnel. He would pay his tithe. He would ask his boon of the High Lord, try not to attract too much attention. And then he would try to sneak this little nightmare out of the court that kept her imprisoned, dying of hunger, caught in a stone grip.

After that, what would come would come.

There is always time to be kind, his mother’s voice whispered.

But first, you had to survive. To prolong the journey into darkness by another week, another day, another hour. To protect the ones who suffered. He was strong enough to face it. He always had been.

#elucien#acotar#elain archeron#lucien vanserra#fanfic#prythian#gwyneth berdara#gwynriel#lesser fae#azriel shadowsinger

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excellent selection of these wonderful animals! For me I can’t help but love the Atlantic sturgeon the most — the passion in my heart that longs for Atlantic sturgeons to swim in the rivers of my homeland like centuries ago gives them a slight edge. I want everyone to know what we had and hope for their return, too!

I tried to get a good variety

#of course every sturgeon is amazing#hoping for their revival and their success always#sturgeon#white sturgeon#lake sturgeon#shovelnose sturgeon#beluga sturgeon#european sea sturgeon#amu darya sturgeon#starry sturgeon#yangtze sturgeon#atlantic sturgeon#siberian sturgeon#sterlet#polls

193 notes

·

View notes

Text

Two Rivers

A photographic journey along the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya rivers tracing the shifting political, social, and geographical landscapes

Carolyn Drake

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

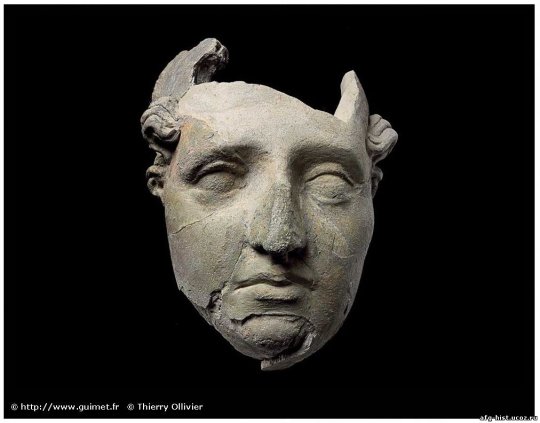

Saka Scythian soldier, as defeated enemy of the Yuezhi, from Khalchayan 1st C. BCE

"Khalchayan (also Khaltchaïan) is an archaeological site, thought to be a small palace or a reception hall, located near the modern town of Denov in Surxondaryo Region of southern Uzbekistan. It is located in the valley of the Surkhan Darya, a northern tributary of the Oxus (modern Amu Darya).

The site is usually attributed to the early Kushans, or their ancestors the Yuezhi/Tocharians. It was excavated by Galina Pugachenkova between 1959 and 1963. The interior walls are decorated with clay sculptures and paintings dated to the mid-1st century BCE, but they are thought to represent events as early as the 2nd century BCE. Various panels depict scenes of Kushan life: battles, feasts, portraits of rulers.

Some of the Khalchayan sculptural scenes are thought to depict the Kushans fighting against a Saka tribe. The Yuezhis are shown with a majestic demeanour, whereas the Sakas are typically represented with side-wiskers in more or less grotesque attitudes."

-taken from wikipedia

#saka#scythian#statue#sculpture#museums#artifacts#antiquities#history#ancient history#1st century bce

95 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Oxus

The Oxus is a river, today called Amu Darya in its western part and Wakhsh in its eastern parts, which flows for a length of 2400 km across modern Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan into Lake Aral. In Ancient times it crossed the regions Fergana, Bactria, Oxeiana, Sogdiana and Khiva. The Oxus and the Iaxartes are called twin rivers, because of their same destination, almost similar trajectories and because they both are thankless rivers, naturally irrigating only very few areas through which they flow. However, like the Iaxartes, the Oxus allowed large-scale irrigation systems which was the main reason of its area's rich history. The Oxus was the nucleus of the successive Bactrian civilizations and kingdoms. The river was the borderline between the Persian satrapy of Sogdiana northward and Bactria southward, whereas the western part belongs to nomads. Several cities were founded here, mostly known under their Greek names, like Alexandreia Oxeiana (actual Termez). Alexander the Great came across the river three times between 329 and 327 BC. Later, the Eastern part of the Oxus was the nucleus of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom, whereas the western part, especially the Khiva Oasis, was the land of the Parni, who later became the Parthians invading the Seleucid empire.

Continue reading...

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

An astronaut aboard the International Space Station took this photograph of the Aral Sea while in orbit over Kazakhstan. This “sea” is actually an endorheic lake, located along the Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan border and fed by the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers. For the past 60 years, the lake has experienced a rapid decline in surface area due to the diversion of its two inflowing rivers to irrigate crops. At its greatest extent, the Aral Sea would have spanned almost the entirety of this photo.

13 notes

·

View notes