#American Literary Translators Association

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

<3 <3 <3 <3 ALTA i love you <3 <3 <3 <3 <3

#stream the american literary translators association#thank u leydeez and lentilmen <3 <3 <3 <3 <3#translation

0 notes

Text

The attempt to humiliate Volodymyr Zelens'kyi in the Oval Office a week ago was an American strategic collapse. It heralded a new constellation of disorderly powers, obsessed with resources, seizing what they can. Inside that new disaster is something old and familiar that we might prefer not to see: antisemitism. The encounter in the White House was antisemitic.

I am historian of the Holocaust. I was trained by a survivor. Jerzy Jedlicki was nine years old when the Germans invaded, and fourteen when he emerged from hiding in Warsaw, and a prominent Polish historian by the time we met. He talked to me about antisemitism for decades, from the time of the breakup of the Soviet Union until his death in 2018. The way that I reacted to the scene in the Oval Office, and how I have pondered and considered it since, have to do with my research, but also with him.

Jerzy survived the Holocaust because his mother Wanda, a literary translator, refused to go with her children to the Warsaw ghetto. Thanks to her courage and ingenuity, and to others who helped her, he and his brother survived. Jerzy's father was murdered, like more than three million other Jews in Poland. The family history emerged bit by bit, as we became friends, as some of his own colleagues wrote memoirs of childhood survival, as my own interests turned towards the war. During my research, I found a recollection, by his mother, of their time in hiding in Warsaw. It turned out that he had helped her to write it.

In post-communist Poland, in the 1990s and 2000s, Jerzy was an activist against antisemitism and xenophobia, and I attended at his urging some of the meetings of the association he helped direct. The entire time, I think, he was trying to train my eye.

Some forms of what he defined as antisemitism had to do with his memories of occupation. Jews had to show deference. Germans mocked the ways Jews dressed. That was before they were sent to the ghetto and murdered. Jews were scapegoated, made responsible for what the Germans wished to do anyway.

Some characteristics of antisemitism as he described it were more abstract. Jewish achievement was portrayed as illegitimate. Jews only gained success, antisemites say, by lying and propaganda. If a Jew was prominent, that only proved the existence of a Jewish conspiracy, and thereby the illegitimacy of the institution where the success was achieved. A prominent Jew was always, went the antisemitic assumption, motivated by money.

Some of what Jerzy said had to do with his experience after the war. Non-Jews will deny the courage and suffering of Jews. They will claim all heroism and martyrdom as their own. He kept a photo of his mother in a locket. It was important to him that she had been courageous. There was a legend in communist Poland, which still survives, which suppressed Jewish courage and claimed all resistance for non-Jewish Poles. And there was after the war a Soviet antisemitism, with a broader and longer heritage, that claimed that Jews had somehow all remained at the rear while others fought and died. The facts were no defense.

The elements that emerged in conversation with Jerzy over the years -- the mockery of Jewish appearances, the need for Jewish submissiveness, the claims about dishonesty, greed, cowardice, and corrupt conspiracies -- figure in the scholarly literature on the subject. And the scholarship is very important, as are the testimonies, and is the teaching in schools. But all of this should help us to see antisemitism in real life. Some cases are so overwhelming in scale that we find them difficult to confront and name. As Orwell noted, it can be hard to see what is right in front of your face.

Much has been said about the evils of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. Its antisemitic element, however, has been underestimated. Russia's major war aim was fascist regime change, the overturning of a democratically-elected president in favor of some sort of collaborator. The premise is absurd: that Ukrainians do not really exist as a nation, and in fact would prefer a Russian. But it was also antisemitic: that it is unnatural that a Jew could hold an important office. Volodymyr Zelens'kyi, the Ukrainian president, is of Jewish origin. Members of his family fought in the Red Army against the Germans. Others were murdered in the Holocaust. Although his Jewishness is not very relevant in Ukrainian politics, it is highly salient to Russian (and other) antisemites.

Ukraine, says Putin, does not really exist. But another theme of the propaganda is that Zelens'kyi is not actually the president of Ukraine. These two bizarre ideas work together: Ukraine is artificial and can exist thanks to the Jewish international conspiracy. The fact that a Jew leads the country confirms — for Russian fascists — both the unreality of Ukraine and the reality of a conspiracy. This Russian regime perspective is implicitly (and sometimes explicitly) antisemitic. Russian propaganda treats Zelens'kyi as obsessed with money and as subhuman. Zelens'kyi was elected on a peace platform in 2019, but Putin did not want to talk to him, in part because he did not think that Zelens'kyi showed him enough deference. The Russian regime that ordered the invasion is itself obviously fascist, on any definition of fascism you care to choose.

Last Friday I happened to start watching the discussion at the White House between Zelens'kyi, Donald Trump, JD Vance and Brian Glenn towards the end, when Vance was already yelling at the Ukrainian president: "you're wrong!" I took in the tone and the body language, and my first, reflexive reactions was: these are non-Jews trying to intimidate a Jew. Three against one. A roomful against one. An antisemitic scene.

And the more I listened to the words, the more that reaction was confirmed. I won't speak for how Zelens'kyi regards himself. Ukrainian, of course. Beyond that I don't know. These things are complex, and personal.

But not for the antisemite.

It was all there, in the Oval Office, in the shouting and in the interruptions, in the noises and in the silences. A courageous man seen as Jewish had to be brought down. When he said things that were simply true he was shouted down and called a propagandist. There was no acknowledgement of Zelens'kyi's bravery in remaining in Kyiv. The Americans portrayed themselves as the real heroes because they provided some of the weapons. The suffering of Ukrainians went unmentioned. An attempt to refer to it was cruelly and falsely reduced to a "propaganda tours" led by Zelens'kyi. The Americans portrayed themselves as the real victims of the because they paid for some of the weapons. It was all, bizarrely, about money. There is this odd Trumpian notion, unique to Ukraine, that aid should be paid back as if it were a loan, with Trump himself just making up the amount owed. Zelens'kyi was portrayed as someone who was taking our cash, giving is nothing in return, ripping us off. He was also mocked for not knowing how to dress for the space, as not belonging. And his deference was demanded: "Have you said thank you once?" "Offer some words of appreciation." And then was thrown out of the White House. And told to resign his office as president of Ukraine.

As always with antisemitism, facts are no defense. Zelens'kyi consistently thanks Americans, as can be easily verified. He is the elected president of a country that is a democratic republic under a constitution. Zelens'kyi won the last election with 73% and his approval rating is now 68%; if there were another election, he would win. By the terms of the constitution, the next election will be held when the war is over and martial law can be lifted. It is the general opinion in Ukraine, shared by Zelens'kyi's opponents in parliament, that elections cannot be held while Russia is invading, holding swathes of Ukrainian territory, and coercing Ukrainian citizens. Zelens'kyi has been personally courageous. He stayed in Kyiv when everyone expected him to flee. He visits the front on a regular basis. Ukrainian suffering, sadly, is all too real, from the torture chambers through the executions through the kidnapped children and destroyed cities. It is quite true that the anti-tank weapons Trump authorized during his first term were very important during the first few weeks of the war. But it was the astonishing fact of successful Ukrainian resistance that led to the delivery of further weapons. The arms allocations to Ukraine were aid, and aid is not a lone. They are an essentially invisible portion of the U.S. budget, a penny on the dollar. Most of that penny on the dollar remains in the U.S., restarting assembly lines that had gone cold. Much of what the U.S. has given Ukraine were obsolescent weapons that would have been otherwise been thrown away. As everyone in the room in fact knew, what Zelens'kyi was wearing was meant as an expression of solidarity with a people at war. It was not so unlike what Churchill wore in the White House in 1942.

To conclude that the scene in the White House was antisemitic, one does not need to know anything further. It's all right there: the demand for deference, the obsession with money, the claims of corruption and dishonesty, the encirclement, the loud voices, the bizarre grievances, the underlying sense that a Jewish person does not fit and must be expelled. The context was evocative enough, and nothing more is really needed: those historical markers of antisemitism; Zelens'kyi's Jewish origins; the particular way he was treated by non-Jews.

If we consider for a moment the men who tried to humiliate him, however, the picture only sharpens and clarifies. The man who asked him about his clothes, Brian Glenn, is a conspiracy-theorizing far-right journalist. It is not clear why he was in the Oval Office; but he does seem to know Marjorie Taylor-Greene, she of the Jewish space lasers and the determined defense of Russian propaganda. The man who demanded deference and spoke of "propaganda tours," JD Vance, had just returned from Germany, where he made a point of publicly supporting the German far right. Vance presents Zelens'kyi as a corrupt liar, with no evidence beyond what was brought to him by an internet which has, apparently, found his vulnerabilities. The man who insisted that the Americans (and indeed he himself personally) were the real heroes, Donald Trump, told Jews last fall they would be held responsible if he lost the election -- among many other things. And the man behind them all, Elon Musk, supports the extreme right in several countries, adapts his social media platform to support fascists, and is notorious around the world for his Hitlergrüß. Musk's idea that Zelens'kyi is a grifter could hardly be more antisemitic.

And what have the Americans done since last Friday? They have scapegoated Zelens'kyi. They have doubled down on lies that, sadly, only make sense in an antisemitic worldview. They have blamed him, over and over again, for the things that they wanted to do anyway. It is somehow his fault, rather than their choice, that they are denying weapons to Ukraine and supporting Russia; that they are denying Ukraine necessary intelligence and thereby making it easier for Russia to kill Ukrainians in missile and drone strikes. The scapegoating is antisemitic in form, relying on preposterous notions that American strategic choices can and should be shaped by an ally's dress and demeanor. And it is antisemitic in content, shifting all responsibility from oneself to the Jewish person who must take the blame for everything. The Americans continue to encircle Zelens'kyi, on media, denying his legitimacy as president, calling for his resignation. Musk piles on, calling Zelens'kyi names, and demanding that he be replaced and removed from his country.

Underlying this all is an assumption that can only really be understood as both antisemitic and anti-Ukrainian: that if Zelens'kyi were to resign, the war would somehow end, because he, and not Putin and the Russians, is somehow its instigator. And that is profoundly and weirdly wrong: Zelens'kyi is not some master conspirator who is somehow getting Ukrainians to do something that they would not otherwise do. Ukrainians are actors in all this. Ukrainians have been attacked and who are defending themselves. Their president is, in his own words, just one grain of sand in the hourglass. If Zelens'kyi were assassinated, an outcome that the American abuse has made more likely, Ukraine would continue to fight.

The American antisemitism now merges with the Russian antisemitism and reinforces it. The idea that Zelens'kyi is not a real president, and that his government is therefore not a real government, has been a very specific Russian antisemitic trope from the beginning. And the Russian approval for the American behavior in the White House since Friday could hardly have been more explicit. A spokesman for Putin expressed his pleasure that policies were aligning. A spokeswoman for the Russian foreign minister compared Ukrainians to pedophiles and thieves. The foreign minister himself said that Zelens'kyi was "hardly human." A former Russian president called Zelens'kyi a swine and cheered on Trump. Russian television has celebrated Trump as a Russian ally all week. During this chorus of Russian praise, the White House halted military aid and limited intelligence assistance to Ukraine. And so the United States is now aiding the fascist invasion, and legitimating the attempt at fascist regime change.

It is harder in the 2020s to call things by name than it was, perhaps, in the last century. Actual fascists now call other people "fascists" to make the word meaningless, and so they themselves cannot be seen for what they are. This is the normal Russian practice, now picked up by American fascists. Antisemites likewise can call other people "antisemites." When Russians say that they had to invaded Ukraine because of someone else’s antisemitism rather than their own, they are just trying to make the term meaningless. When Americans claim that antisemitism means that universities must be harassed, they are doing much the same thing. The fact that someone wants to ban protests does not mean that they oppose antisemitism. History would suggest rather the contrary. A concerted effort is being made to train us to think that antisemitism is something besides traditionally hostile ways that non-Jews regard and treat Jews. The result of these semantic abuses is a trivialization of antisemitism — a concept we all need to be able to take seriously, a phenomenon we all need to recognize.

In addition to abusing the word, antisemites can react with manufactured outrage when called out. They can try to hide behind Israel, or by pointing to Jews in their vicinity. So when confronted by actions that appear antisemitic, you have to consider what you see for yourself. The moral and political implications are of the greatest significance. I had a strong personal reaction to that scene in the Oval Office, and I checked it for a week with friends and colleagues, who confessed that they had had the same reaction. I reconsidered what I had learned as a historian. I looked at the scholarly definitions. Everything, sadly, lines up.

The negative reactions to the Oval Office scene can of course take other forms. The antisemitic element of the confrontation, though important, was not the only dynamic. Ukrainians and Europeans, understandably, took the attempt to humiliate Zelens’kyi as a prompt to begin discussions of a security order that accounts for an unreliable United States. Moral assessments along other lines also came in, including from former dissidents in eastern Europe. On Monday, thirty onetime Polish anti-communist oppositionists signed a letter to Donald Trump. They expressed their repugnance at how Zelens'kyi had been treated in the White House. They pointed out that no monetary currency can be equivalent to that of blood shed for freedom. They compared the atmosphere in the Oval Office during that confrontation on Friday to that of a communist interrogation or communist trial, in which the person who had taken the risk to do right was told that they held no cards, that might makes right.

My dissertation advisor, Jerzy Jedlicki, had been a dissident. Polish communists placed him in an internment camp. Perhaps Jerzy, were he still with us, would have signed that letter. As someone who has studied and written about communist terror, I can see the dissident perspective; and given their own personal experiences with interrogations and communist terror, it is one that must be taken seriously. What they failed to mention, though, is that communist interrogation techniques in the 1970s and 1980s were antisemitic: people of Jewish origin were presented as alien to the nation, and were subjected to special abuse. Multiple interrogators would encircle the dissident, and talk among themselves about his supposedly Jewish betrayals and failures. Encirclement, bullying, belittling.

And so I can't escape that first reflexive response to that scene in the Oval Office: here is a person of Jewish origin being treated in a very particular and familiar way by non-Jews. I get the dissidents’ comparison to an interrogation or trial, and can imagine the cell or the courtroom. But what struck me was the circle of bullying gentiles -- as in Europe in the 1930s, and in other places and times, at the particular moment when the mob felt that power was shifting.

But is it? In writing about antisemitism here I am obviously making a moral point. I am asking us, Americans, to think seriously about what we are doing, about Russia's criminal war against Ukraine, in which we are now becoming complicit. That Russia's war is antisemitic is one of its many evils; taking Russia’s side in that war is wrong for many reasons, including that one. At a time when antisemitism is a growing problem around the world, I would like for us to be able to see the obvious examples, especially when we Americans are so closely involved in them. There is a certain mobbish mindlessness in the growing circle of American voices calling for Zelens'kyi to leave office, and I think it has a name and a history. I would like for us to recall that history and remember that the name can apply to us.

In writing about antisemitism I am also making a political claim. The antisemite really believes that the Jew must defer, that the Jew cannot fight, that a state led by a Jew must duly crumble. This was one of Putin's mistakes, two years ago. And now, I suspect, it is also Trump's, and Musk's. America does have the power, of course, to hurt Ukraine. Just as Russia does. The combination of American and Russian policy is killing Ukrainians right now. The costs of the emerging Russian-American axis will be terrible for Ukraine. But Ukraine will not immediately collapse, nor will the Ukrainian population turn against Zelens'kyi. What he will personally do I couldn't say and won't try to predict: and that, of course, is my point.

In the world of the antisemite, all is known in advance: the Jew is just a deceiver, concerned only with money, subject to exclusion, intimidated by force. As soon as he is humiliated and eliminated, everything else will fall into its proper place. Consider the smirks in the Oval Office last Friday: the antisemite thinks that he has understood everything. But in the actual world in which we actually live, Jews are humans, perilous and beautiful like the rest of us. The United States has never elected a Jewish president, and perhaps never will. But Ukraine has; and that president represents his people, facing challenges that those who mock him will never understand. Those Americans have chosen to add their own to the evil he must confront. But that does not mean that they will control what happens next.

In 1936, before the war, Wanda, Jerzy’s mother, translated a book entitled Oil Rules the World. We seem to be heedlessly returning to an era where resources demand violence. American foreign policy now seems to be all about mineral wealth: in Greenland, in Canada, and in Ukraine — where the pressure on Zelens’kyi is connected to an American desire to control Ukrainian minerals. This is worrying for a number of reasons.

In the antisemitic imagination, everything is for the taking. I used to talk with Jerzy Jedlicki about Mein Kampf, whether and how it should be censored, who read it in the twenty-first century. Our world, as Hitler described it in Mein Kampf, is just thin crust of land, to be defined by the fertility of the topsoil and the bounty of the minerals beneath. Only the Jews, he thought, stand in the way of its conquest by the strongest. Behind all of the calumnies about the lying and the stealing and the conspiracies was Hitler's true fear: the Jews, he thought, were the only source of human values, the reason why we might think that there is something in the world aside from power and the greed of the powerful, something beyond an endless war for topsoil and minerals. To extinguish virtue the Jew must be mocked, and then marginalized, and then murdered. And that, of course, worked as politics in Nazi Germany; not because the premise was true, but because Germans went along, killing their own virtue along the way. Never again means attending to the smaller aggressions that imply the greater ones to come.

The war that Hitler began, the Second World War, was about eliminating Jews and stealing resources. He was aiming above all for the fertile soil of Ukraine and the mineral wealth of the Caucasus: for what he called Lebensraum, living space. To get to Ukraine, Germans had to cross Poland, where they created ghettos, like the one in Warsaw where Wanda did not go; and then the death factories, like Treblinka, where the Jews of Warsaw were murdered. Jerzy escaped gassing at Treblinka; decades later on he tried to helped me to see, and to think. He was trying to help me to have the eye of a historian in the present, and perhaps he succeeded, a bit. About one thing I am certain. Our eyes have to be open to what we do not wish to see.

214 notes

·

View notes

Text

Milestone Monday

Poetry in Punk

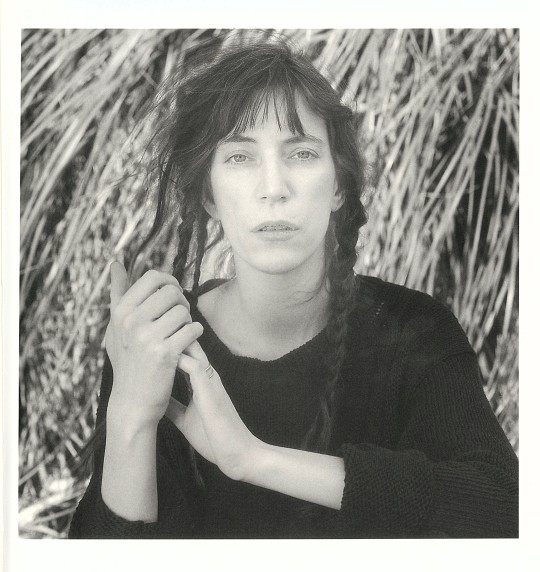

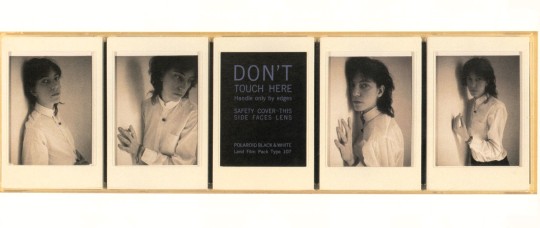

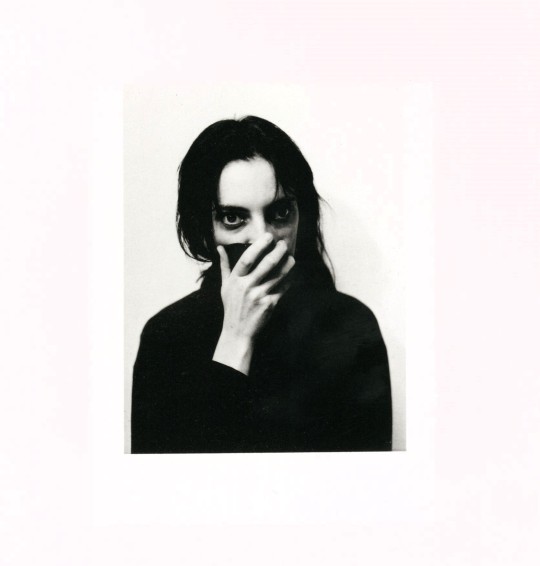

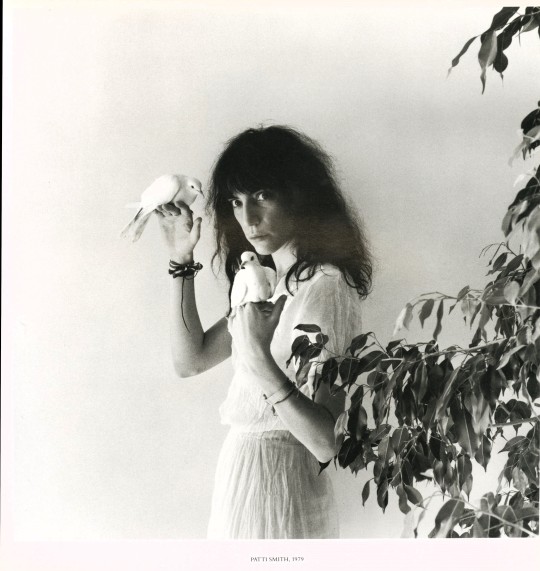

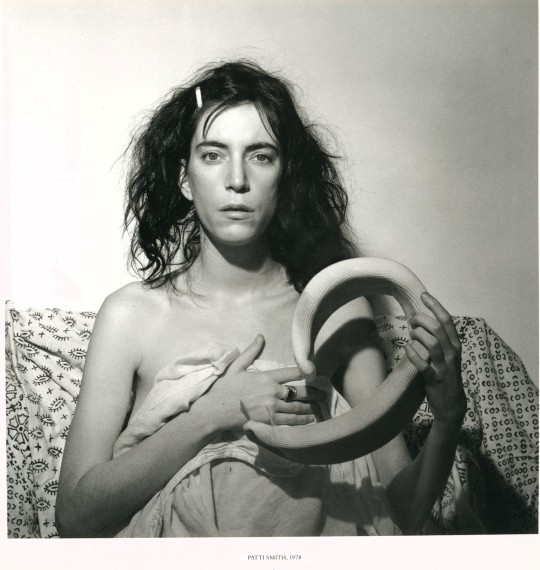

On this day, December 30th, 1946, Patti Smith, a singer, songwriter, author, poet, photographer, and painter, was born in Chicago, Illinois. Often referred to as the "Godmother of Punk," Smith is known for her influential music that blends rock and poetry. Her debut album, Horses, released in 1975, is considered a landmark work in the punk rock genre. Beyond her music career, Patti Smith has written several books, including the acclaimed memoir Just Kids, which explores her relationship with photographer Robert Mapplethorpe and their experiences within the New York City artistic scene. Throughout her life, she has been a prominent cultural figure, advocating for artistic freedom and social change.

Images featured come from:

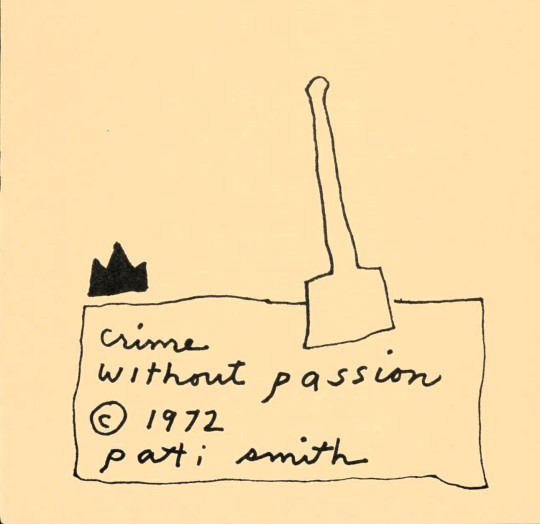

Our first edition of A Useless Death, a poem by Patti Smith that was published as a chapbook and distributed by Gotham Book Mart and Gallery in New York in 1972.

Ha! Ha! Houdini!, a poem written by Patti Smith and published as a chapbook. It was distributed by Gotham Book Mart and Gallery in New York in 1977.

Robert Mapplethorpe, released by Peter Weiermair and published by Robert Wilk in 1981. The contexts come from a catalogue of an exhibition sponsored by the Frankfurter Kunstverein, April 10-May 17, 1981, and features an introduction by Sam Wagstaff, the artistic mentor and benefactor to Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith.

Some Women by Robert Mapplethorpe that features an introduction by one of the pioneers of New Journalism, Joan Didion. Our first edition was published in Boston by Bulfinch Press in 1989.

Robert Mapplethorpe by Richard Marshall with essays by American poet, literary critic essayist, teacher, and translator Richard Howard, and South African-born American writer and editor Ingrid Sischy. Our copy is the first cloth edition, published in New York: Whitney Museum of American Art; Boston: in association with Bulfinch Press: Little, Brown and Company in 1988.

Mapplethorpe prepared in collaboration with the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation with an essay by American art critic, philosopher, and Professor Arthur C. Danto. This first edition was published in 1992 by Random House in New York.

-View more Milestone Monday posts

-Melissa, Special Collections Graduate Intern

#milestone monday#patti smith#milestones#Arthur C. Danto#robert mapplethorpe#photograhy#birthdays#punk#poetry#music#singers#songwriter#poet#author#punk rock#A Useless Death#ha ha houdini#Some women#Bulfinch Press#Gotham Book Mart and Gallery#Peter Weiermair#Robert Wilk#Frankfurter Kunstverein#Sam Wagstaff#joan didion#Richard Marshall#Richard Howard#Ingrid Sischy#Whitney Museum of American Art#Little Brown and Company

105 notes

·

View notes

Text

DON'T CALL ME MABON

WHY MABON IS AN INAPPROPRIATE NAME FOR THE AUTUMN EQUINOX

by Anna Franklin

The name ‘Mabon’ as a term for the neopagan festival of the autumn equinox (along with the Saxon term ‘Litha’ for the summer solstice) was introduced in 1973 by the American witch and writer Aiden Kelly (b. 1940). His blog for 21st September 2012 explains:

“Back in 1973, I was putting together a “Pagan-Craft” calendar—the first of its kind, as far as I know—listing the holidays, astrological aspects, and other stuff of interest to Pagans. It offended my aesthetic sensibilities that there seemed to be no Pagan names for the summer solstice or the fall equinox equivalent to Ostara or Beltane—so I decided to supply them… I began wondering if there had been a myth similar to that of Kore in a Celtic culture. There was nothing very similar in the Gaelic literature, but there was in the Welsh, in the Mabinogion collection, the story of Mabon ap Modron (which translates as “Son of the Mother,” just as Kore simply meant “girl”), whom Gwydion rescues from the underworld, much as Theseus rescued Helen. That’s why I picked “Mabon” as a name for the holiday…” bd

Curiously, his own tradition, the New Reformed Orthodox Order of the Golden Dawn, did not follow him in this and instead called the autumn equinox ‘Rites of Eleusis’. However, the term took off and was used in many American books, and by extension, the readers of those books in the UK and elsewhere.

The association of the god Mabon with the festival is certainly not an ancient or traditional despite the claims in various books and websites where you might read ‘the Celts celebrated the god Mabon on this date’.

In order to see why the name of Mabon for the autumn equinox is an inappropriate one we need to examine the tales of Mabon.

The Celtic God Maponius

There is certainly a Celtic god whose title was Latinized as Maponus, which is not an actual name but means something like ‘divine son’. He is known from a number of inscriptions in northern Britain and Gaul in which he is addressed as ‘Apollo Maponus’ identifying him with the Graeco-Roman sun-god Apollo. Like Apollo, all the evidence suggests that he was a god of the sun, music and hunting – significantly, he was not a god of the harvest or of the corn.

It is not known whether he was widely worshipped before the coming of the Romans, but with them his cult spread along Hadrian’s Wall amongst the Roman soldiers stationed there. Several stone heads found at the Wall are identified as representing Maponus.

He was also known in Gaul where he was invoked with a Latin inscription at Bourbonne-les-Bains, and on a lead cursing tablet discovered at Chamalières, Puy-de-Dôme where he is invoked along with Lugus (Lugh) to quicken underworld spirits to right a wrong.

It is possible that there are some place names associated with him, such as Ruabon in Denbighshire, which may or may not be a corruption of Rhiw Fabon, meaning ‘Hillside of Mabon’. be During the seventh century an unknown monk at the Monastery at Ravenna in Italy compiled what came to be called The Ravenna Cosmography, which was a list of all the towns and road-stations throughout the Roman Empire. It lists a Locus Maponi (‘place of Maponus’) which has been tentatively identified with the Lochmaben stone site.

It is possible that Mabon’s Irish equivalent is the god Aengus, also known as the Mac Óg (‘young son’).

Literary Sources

A character called Mabon is found as a minor character in the Mabinogion, a collection of eleven – sometimes twelve – Welsh prose tales from the Middle Ages. He is called Mabon ap Modron, meaning ‘son of the mother’, which has led to speculation that his mother Modron (‘mother’) may be cognate with the Gaulish mother goddess Matrona. There are no inscriptions dedicated to her from ancient times, so this cannot be verified. Whether or not the Mabinogion tale of the hero Mabon stems from a thousand year old story of the god Maponus is uncertain, but since the stories contain the names of other known Celtic gods (transliterated into heroes) it is certainly possible.

The Mabinogion is a collection of medieval Welsh stories which would have been recorded by Christian monks. They don’t seem to have been very widely known until they were translated into English in 1849 by Lady Charlotte Guest, who invented the title Mabinogion since each of the four branches ends with the words “so ends this Branch of the Mabinogi”. In Welsh, mab means ‘son’ or ‘boy’ or ‘youth’, so she concluded that mabinogi meant ‘a story for children’ and (erroneously) that mabinogion was its plural. Another possibility is that it comes from the proposed Welsh mabinog meaning something like ‘bardic student’.

The stories now included in the Mabinogion are found in two manuscripts, the older White Book of Rhydderch (c.1300–1325) and the later Red Book of Hergest (c.1375–1425) and Lady Charlotte Guest used only the latter as her source, though later translations have drawn on both books.

The first four tales, called The Four Branches of the Mabinogi, are divided into Pwyll, Branwen, Manawydan and Math and each of these includes the character Pryderi. The Mabinogion scholar W.G.Gruffydd suggested that the four branches of the collection represent the birth, exploits, imprisonment and death of Pryderi.

Mabon is mentioned in the Mabinogion story of The Dream of Rhonabwy in which he is described as one of the King’s chief advisors and fights alongside him at the Battle of Badon. His biggest role comes in the story of Culhwch and Olwen (originally from White Book of Rhydderch). In it is the only known reference to Olwen, and Mabon is still a very minor character in the story. One task of the heroes is to search for Mabon ap Modron, who was imprisoned in a watery Gloucester dungeon. Arthur’s cousin Mabon had been taken from his mother Modron when he was only three nights old, and no one knew whether he was alive or dead. After asking the oldest animals, they were finally directed to the oldest creature of all: the great Salmon of Llyn Llyw. The salmon recalled hearing of Mabon, and told them that as he swam daily by the wall of Caer Loyw, he heard a constant lamentation. The salmon took Cei and Gwrhyr upon his back to the castle, and they heard Mabon’s cries bewailing his fate. Mabon could not be ransomed, so seeing that force was the only answer, the knights fetched Arthur and his war band to attack the castle. Riding on the salmon’s back, Cai broke through the wall and collected Mabon, both fleeing on the back of the salmon.

Let us suppose for a moment that the god Maponus and the literary hero Mabon are one and the same. We must remember that all the evidence points to Maponus being the young sun god, his youth meaning that he would represent the morning sun or the sun newly reborn after the winter solstice. His theft from his mother after three days would make sense in this light – the three days being the three days the sun stands still at the winter solstice. The imprisonment of the young god underground equates to the sun in the underworld before he is ‘released’ to begin his reign as the new sun. In Culhwch and Olwen, Mabon is said to be imprisoned inside a tower in Gloucester, from which he is freed by Cei and Bedwyr. The ‘missing sun’ or ‘imprisoned sun’ is a premise found in the solar myths of many cultures to explain the night or the shorter days of winter, especially those around the three days of the winter solstice. Such tales often include themes of captivity or the theft of the sun (i.e. the god or object that represents it) and its rescue by a band of heroes, such as Jason and the Argonauts rescuing the Golden Fleece (the sun) from the dragon or the Lithuanian sun goddess Saule, was held in a tower by powerful king, rescued by the zodiac using a giant sledgehammer, or the Japanese sun goddess Amaterasu hiding in a cave.

An earlier source that mentions Mabon is the tenth century poem Pa Gur, in which Arthur recounts the great deeds of his knights in order to gain entrance to a fortress guarded by Glewlwyd Gafaelfawr. In this, Arthur describes Mabon fab Madron as one of his men and says that Mabon is a servant of Uther Pendragon. A second Mabon is mentioned, Mabon fab Mellt (‘Mabon Son of Lightning’) and this is interesting, since the sky/storm god is often the father of the sun god in myth, as Zeus is the father of Apollo.

Mabon defeats the monstrous boar, and in myth the boar is often a symbol of winter and the underworld, just as the sun after the winter solstice defeats winter. Mabon then is the divine sun-child born at the winter solstice and this is his festival – he is not the aged god of the harvest or the seed in the ground as Kore is in Greek myth. As Sorita d’Este says:

“Honour Mabon as a Wizard, a Merlin type figure, as the oldest of men and beasts, honour him as the Son of the Mother, and a hero – don’t take that away from him by ignorantly using his name as if it is a different word for Autumn Equinox. If you really believe that the Old Gods of these lands still live, that they should be honoured and respected, then do that. Don’t join the generations who tried to belittle the Gods in an effort to diminish their power.”[1]

© Anna Franklin, The Autumn Equinox, History, Lore and Celebration, Lear Books, 2012

#thevirginwitch#witchcraft#witch#witchblr#witchy#witches of tumblr#pagan#baby witch#beginner witch#wheel of the year#mabon#fall equinox#autumnal equinox#autumn equinox

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just in case. Some might enjoy. Had to organize some notes.

These are just some of the newer texts that had been promoted in the past few years at the online home of the American Association of Geographers. [At: aag dot org/new-books-for-geographers/]

Tried to narrow down selections to focus on (1) Indigenous, Black, Latin American, oceanic/archipelagic geographies; (2) imaginaries and environmental perception; (3) and mobility, borders, carceral/abolition geography.

These texts feature concepts/subjects like: Indigeneity and "geographies of time" in the Ecuadorian Andes. "Migration and music in the construction of precolonial AfroAsia." The "practice of collective escape" and "reimagining geographies of order." The "making and unmaking of French India." The "literary geography" of the rubber boom in Amazonia. "Coercive geographies" and mass imprisonment. "Anti-fatness as anti-Blackness." The "(un)governable city" of colonial Delhi.

---

New stuff, early 2024:

A Caribbean Poetics of Spirit (Hannah Regis, University of the West Indies Press, 2024)

Constructing Worlds Otherwise: Societies in Movement and Anticolonial Paths in Latin America (Raúl Zibechi and translator George Ygarza Quispe, AK Press, 2024)

Fluid Geographies: Water, Science, and Settler Colonialism in New Mexico (K. Maria D. Lane, University of Chicago Press, 2024)

Hydrofeminist Thinking With Oceans: Political and Scholarly Possibilities (Tarara Shefer, Vivienne Bozalek, and Nike Romano, Routledge, 2024)

Making the Literary-Geographical World of Sherlock Holmes: The Game Is Afoot (David McLaughlin, University of Chicago Press, 2025)

Mapping Middle-earth: Environmental and Political Narratives in J. R. R. Tolkien’s Cartographies (Anahit Behrooz, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2024)

Midlife Geographies: Changing Lifecourses across Generations, Spaces and Time (Aija Lulle, Bristol University Press, 2024)

Society Despite the State: Reimagining Geographies of Order (Anthony Ince and Geronimo Barrera de la Torre, Pluto Press, 2024)

---

New stuff, 2023:

The Black Geographic: Praxis, Resistance, Futurity (Camilla Hawthorne and Jovan Scott Lewis, Duke University Press, 2023)

Activist Feminist Geographies (Edited by Kate Boyer, Latoya Eaves and Jennifer Fluri, Bristol University Press, 2023)

The Silences of Dispossession: Agrarian Change and Indigenous Politics in Argentina (Mercedes Biocca, Pluto Press, 2023)

The Sovereign Trickster: Death and Laughter in the Age of Dueterte (Vicente L. Rafael, Duke University Press, 2022)

Ottoman Passports: Security and Geographic Mobility, 1876-1908 (İlkay Yılmaz, Syracuse University Press, 2023)

The Practice of Collective Escape (Helen Traill, Bristol University Press, 2023)

Maps of Sorrow: Migration and Music in the Construction of Precolonial AfroAsia (Sumangala Damodaran and Ari Sitas, Columbia University Press, 2023)

---

New stuff, late 2022:

B.H. Roberts, Moral Geography, and the Making of a Modern Racist (Clyde R. Forsberg, Jr.and Phillip Gordon Mackintosh, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2022)

Environing Empire: Nature, Infrastructure and the Making of German Southwest Africa (Martin Kalb, Berghahn Books, 2022)

Sentient Ecologies: Xenophobic Imaginaries of Landscape (Edited by Alexandra Coțofană and Hikmet Kuran, Berghahn Books 2022)

Colonial Geography: Race and Space in German East Africa, 1884–1905 (Matthew Unangst, University of Toronto Press, 2022)

The Geographies of African American Short Fiction (Kenton Rambsy, University of Mississippi Press, 2022)

Knowing Manchuria: Environments, the Senses, and Natural Knowledge on an Asian Borderland (Ruth Rogaski, University of Chicago Press, 2022)

Punishing Places: The Geography of Mass Imprisonment (Jessica T. Simes, University of California Press, 2021)

---

New stuff, early 2022:

Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-fatness as Anti-Blackness (Da’Shaun Harrison, 2021)

Coercive Geographies: Historicizing Mobility, Labor and Confinement (Edited by Johan Heinsen, Martin Bak Jørgensen, and Martin Ottovay Jørgensen, Haymarket Books, 2021)

Confederate Exodus: Social and Environmental Forces in the Migration of U.S. Southerners to Brazil (Alan Marcus, University of Nebraska Press, 2021)

Decolonial Feminisms, Power and Place (Palgrave, 2021)

Krakow: An Ecobiography (Edited by Adam Izdebski & Rafał Szmytka, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2021)

Open Hand, Closed Fist: Practices of Undocumented Organizing in a Hostile State (Kathryn Abrams, University of California Press, 2022)

Unsettling Utopia: The Making and Unmaking of French India (Jessica Namakkal, 2021)

---

New stuff, 2020 and 2021:

Mapping the Amazon: Literary Geography after the Rubber Boom (Amanda Smith, Liverpool University Press, 2021)

Geopolitics, Culture, and the Scientific Imaginary in Latin America (Edited by María del Pilar Blanco and Joanna Page, 2020)

Reconstructing public housing: Liverpool’s hidden history of collective alternatives (Matt Thompson, University of Liverpool Press, 2020)

The (Un)governable City: Productive Failure in the Making of Colonial Delhi, 1858–1911 (Raghav Kishore, 2020)

Multispecies Households in the Saian Mountains: Ecology at the Russia-Mongolia Border (Edited by Alex Oehler and Anna Varfolomeeva, 2020)

Urban Mountain Beings: History, Indigeneity, and Geographies of Time in Quito, Ecuador (Kathleen S. Fine-Dare, 2019)

City of Refuge: Slavery and Petit Marronage in the Great Dismal Swamp, 1763-1856 (Marcus P. Nevius, University of Georgia Press, 2020)

#abolition#ecology#multispecies#landscape#tidalectics#indigenous#ecologies#archipelagic thinking#opacity and fugitivity#geographic imaginaries#caribbean#carceral geography#intimacies of four continents#reading list#reading recommendations#book recommendations#my writing i guess#indigenous pedagogies#black methodologies

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

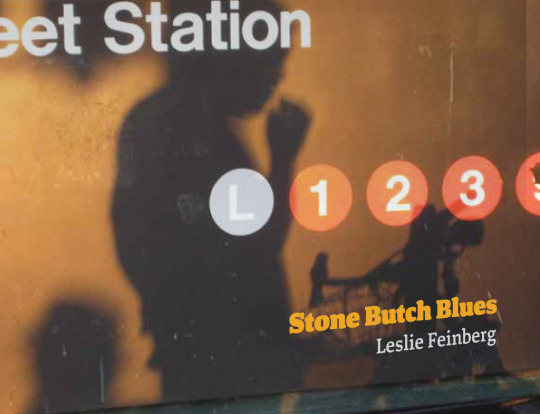

Stone Butch Blues by Leslie Feinberg

"Stone Butch Blues," Leslie Feinberg’s 1993 first novel, is considered in and outside the U.S. to be a groundbreaking work about the complexities of gender. Feinberg was the first theorist to advance a Marxist concept of “transgender liberation.” Sold by hundreds of thousands of copies, passed hand-to-hand inside prisons, the novel has been translated into Chinese, Dutch, German, Italian, Slovenian, Turkish, and Hebrew--with earnings from that edition going to ASWAT Palestinian Gay Women--and won the 1994 American Library Association Stonewall Book Award and 1994 Lambda Literary Award. Feinberg said in hir Author’s Note to the 2003 edition: "Like my own life, this novel defies easy classification. If you found 'Stone Butch Blues' in a bookstore or library, what category was it in? Lesbian fiction? Gender studies? Like the germinal novel 'The Well of Loneliness' by Radclyffe/John Hall, this is a lesbian novel and a transgender novel—making ‘trans’ genre a verb, as well as an adjective."

Once xyr regained her rights to the book, Leslie Feinberg made the ebook available for free permanently at https://www.lesliefeinberg.net/

#free books#queer books#lgbtq books#trans books#lesbian books#butch books#trans rights readathon#stone butch blues#leslie feinberg#active

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

The profile of longtime Johns Hopkins Professor Richard A. Macksey

Richard A. Macksey, was a celebrated Johns Hopkins University professor whose affiliation with the university spanned six and a half decades.

A legendary figure not only in his own fields of critical theory, comparative literature, and film studies but across all the humanities, Macksey possessed enormous intellectual capacity and a deeply insightful human nature. He was a man who read and wrote in six languages, was instrumental in launching a new era in structuralist thought in America, maintained a personal library containing a staggering collection of books and manuscripts, inspired generations of students to follow him to the thorniest heights of the human intellect, and penned or edited dozens of volumes of scholarly works, fiction, poetry, and translation.

Macksey loved classical literature, foreign films, comic novels, and medical narratives—all subjects he taught at one time or another. Conversations with him were marked by a tendency to leap from one topic to another, connected by his seemingly boundless knowledge, prodigious memory, and sense of humor. For many at Hopkins and far beyond, he was no less than the embodiment of the humanities, both in intellect and spirit.

"Dick Macksey was a Johns Hopkins legend," says James Harris, a professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, director of the Developmental Neuropsychiatry Clinic, and a longtime friend of Macksey's. "He was a teacher, mentor, and friend to generations of Hopkins faculty and students. To me, he was the most erudite, kind, gracious, and considerate person I have ever known. He will be deeply missed and always remembered as the epitome of what makes Johns Hopkins a world-class university."

Born in New Jersey on July 25, 1931, Macksey planned to be a doctor and had launched his collection of medical books by the age of 5. After beginning his undergraduate studies at Princeton, he transferred to Hopkins and earned a bachelor's degree in 1953 and master's degree in 1954, both in Writing Seminars. He went on to earn a doctorate in comparative literature from Hopkins in 1957, writing his dissertation on Proust in French. While completing his thesis, he took a teaching position at Loyola College in Baltimore (now Loyola University Maryland) and after receiving his degree, returned to Hopkins as an assistant professor in the Writing Seminars. Quickly expanding beyond the writing workshops and "modern writers" courses he taught, he soon introduced a film class and initiated the first courses at Johns Hopkins in African American literature, women's studies, and scholarly publishing.

In 1966, Macksey led the charge in founding the Johns Hopkins Humanities Center—now the Department of Comparative Thought and Literature—as a meeting ground and incubator for problems, ideas, and discussions across disciplines. A degree-granting department, the Humanities Center sponsored graduate and undergraduate courses in literature, art, philosophy, and history; ran a graduate program; and maintained an active program of visiting scholars, professors, and lecturers. Macksey served as its director from 1970 until 1982, and he was a professor on its faculty until his retirement in 2010. Macksey continued to teach several courses until as recently as spring 2018.

The same year he launched the Humanities Center, Macksey joined French literary theorist and philosopher of social sciences René Girard, then associate professor of French at Hopkins, and deconstructionist and literary critic Eugenio Donato (both of whom co-founded the Humanities Center with Macksey) in convening an international symposium called The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man. It was the first time that many leading figures of European structuralist criticism—including Jacques Derrida, Jacques Lacan, Roland Barthes, and Paul de Man—presented their ideas to the American academic community, throwing open a new conduit to avant-garde French theory and placing Hopkins at the center of an international intellectual conversation.

At the symposium, Derrida first presented his groundbreaking critique of structuralism, creating an entirely new perspective on how philosophy, literature, and language relate to and affect one another. The symposium's proceedings became the landmark study titled The Structuralist Controversy. The gathering set an intellectual standard that no U.S. humanities conference since has been able to match in intensity or intellectual stature, and heralded—or perhaps precipitated—the field's shift from structuralism to post-structuralism.

The many sides of Richard Macksey

"Everyone talks about 'interdisciplinary,' but he taught as if teaching and learning was a work of art," says Caleb Deschanel, director and Oscar-nominated cinematographer who graduated from Johns Hopkins in 1966. "[Macksey's teaching style] covered all the bases. If you were studying literature in the 19th century, it related to the music and art and sociology of the time. It's really what learning was supposed to be about. What it taught me was the fact that learning is about everything at the same time. Richard Macksey could somehow weave together all the elements and all the aspects of human existence into one thing, and that's what made him so great."

While a student, Deschanel proposed a film class to Macksey, who responded, why not? The class created a 16mm film, and Deschanel says that ever since, his work has been informed by the way Macksey taught him to question his instincts and search for the universal. He learned not to think of a piece of literature just as literature but as a work of art in a period of time, and about what we can learn from those universal ideas. "He taught you how to explode all the myths about things and come to the truth about what they were. Every time I do anything, my first thing is to doubt my first instincts about it. He saw learning and teaching the way we think of a work of art."

More than leading a life of aloof intellectualism, Macksey also existed fully on the human plane. A night owl, he was regularly spotted grocery shopping and volunteering at Baltimore's The Book Thing late into the evening and in the early morning hours; he liked to solve the trivia questions posed during Orioles games at Memorial Stadium; and he featured his cat, Buttons, as his Facebook cover photo. A fan of film and film history, Macksey was an inaugural founder and supporter of the 1970s Baltimore Film Festival, a predecessor of today's Maryland Film Festival.

It may have been partly due to his ability to exist on just a few hours of sleep that his presence had a way of being ever-present. Former student Rob Friedman, who graduated in 1981, remembers waking up at 1 a.m. to hear Macksey's voice drifting through his apartment window, and glimpsed the professor walking down St. Paul Street and "yakking with five students." On another occasion, Friedman awoke early and stepped outside at 6 a.m., only to find Macksey driving by and waving.

"He was so brilliant and had such an encyclopedic memory, and was also such an exuberant personality. He loved learning, he loved talking about what he was learning, and he also loved learning about what you had to say," Friedman says. "It's the generosity of his spirit and his contagious love of learning and excitement in sharing that learning. He might suddenly quote something in Greek."

Friedman met Macksey in 1977 when a friend advised him to get to know Macksey because of his sense of humor. Friedman left a funny note on Macksey's desk and the next day received an interoffice envelope with a humorous response. The two began sending comedic lines back and forth, and Friedman switched his major to humanistic studies so that Macksey could be his adviser.

"I was extremely unhappy during my college years, and if it hadn't been for him I wouldn't have finished school," Friedman says. "He really made a substantial difference in my life, not just academically but personally. I can't express the magnitude of my gratitude for Dick. There are probably 64 years' worth of people that—behind the scenes—he looked after."

Over the years, Macksey was celebrated for that dedication to teaching and received numerous awards. He also established awards in his name. In 1992, Macksey received the university's George E. Owen Teaching Award, given annually for outstanding teaching and devotion to undergraduates. In 1999, the Johns Hopkins Alumni Association awarded him its Distinguished Alumni Award, and the same year the Richard A. Macksey Professorship for Distinguished Teaching in the Humanities was endowed by former student Edward T. Dangel III and his wife, Bonni Widdoes. The professorship is currently held by author and Writing Seminars professor Alice McDermott.

In 2010, Macksey received a Hopkins Heritage Award, which honors alumni and friends of Hopkins who have contributed outstanding service over an extended period to the progress of the university or the activities of the Alumni Association. The Alexander Grass Humanities Institute hosts the Richard A. Macksey Lecture annually, and the Macksey Award is given each year to the graduating member of the Johns Hopkins chapter of Phi Beta Kappa who took the most academic risks.

Bridging medicine and the humanities

Famous at Hopkins for riding a Harley Davidson motorcycle to class in Gilman Hall and for the ever-present pipe between his teeth, Macksey held joint appointments in Writing Seminars and in History of Medicine at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, where he co-directed the Humanities Programs starting in 1990. With neurosurgeon George Udvarhelyi, he co-founded the School of Medicine's Office of Cultural Affairs in 1977 as a cross-campus initiative to engage in rigorous inquiry between the humanities and arts and health, science, and the delivery of care. Starting with just a few resources, the pair attracted funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Endowment for the Arts to bring in speakers with international reputations in medicine and the humanities, including Primo Levi and Umberto Eco.

"Because of Dick Macksey's legacy, we can position Hopkins as a key center of the intersection of humanities and medicine," says Jeremy Greene, professor of medicine and the history of medicine and director of the Institute of the History of Medicine. "He really blazed a path between the two campuses that many people have been able to follow since, and draw closer together the relevance between the humanities and medicine in the 21st century."

In 1992, Catherine DeAngelis, then the School of Medicine vice dean of academic affairs, received a grant to update the 75-year-old medical school curriculum. Wanting to familiarize med students with literature, poetry, theater, and the arts, she asked Macksey if he would assist in developing a four-year course called Physician and Society.

"I could think of no one better to teach in that course than Dick Macksey even though he wasn't in the School of Medicine. He really made that course so special, and I learned a lot from him by sitting in," says DeAngelis, now University Distinguished Service Professor Emerita and professor of pediatrics emerita.

"He was absolutely brilliant, but if you talked to him you would never know from him how brilliant he was," she adds. "He was approachable, and just so kind."

Generosity of spirit

Macksey was beloved for his generosity, the way he fully devoted himself to every conversation and cared about every person and his or her ideas. He thrived on engaging with everyone, eagerly giving his attention to students' thoughts and to them as people, and he never met a conversation or topic he didn't find interesting.

"Dick, of course, was brilliant, with a superb and elegant command of language, and that extraordinary memory," says John Astin, theater program director and Homewood Professor of the Arts. "Beyond that, he was a cherished companion, possessing infinite kindness whom I shall miss always. The world is less without him but much better for having had him for a time."

Friedman remembers one student who had discovered an obscure Portuguese poet, read a translation, and wanted to learn more. The student approached faculty in what is now the Department of German and Romance Languages and Literatures, but no one was familiar with the poet. Someone advised him to ask Macksey if he'd heard of him. "He said, 'of course,' and handed him an entire file of research and the poet's life history," Friedman says.

"I visited him two weeks ago when he was still able to talk and even laugh despite being bedridden," says Richard Chisolm, a documentary filmmaker whom Macksey hired to teach film at Hopkins in the 1980s and '90s, and a friend of Macksey's for 40 years. "He was a one-of-a-kind intellectual giant and a joyful teacher who was never self-centered; always filled with good humor, curiosity, and an intense love of conversation—in over a dozen languages."

A legendary library

In 1972, Macksey and his wife, Catherine Macksey, converted the garage of their home into a library. But his sprawling collection was never confined to its walls, spilling into bookshelves throughout their home and even occupying the steps of the ladders intended to access the upper shelves. "Chez Macksey," as it was fondly known, was where he frequently held classes and film viewings and subsequent discussions, and Macksey and his students would compete with those books for space around a table late into the night, often fueled by cookies and pipe smoke, while works of fine art looked on.

"Students for decade after decade have reveled in the life of that house: To be around a world of learning, enthusiasm, watching movies in the wee hours, listening to this expansive mind firing off in seven directions at once, and learning something they never knew before," Friedman says.

The collection holds not only an impressive number of diverse titles but also, scrawled in the margins, insights into Macksey's mind. He would frequently write on the pages, creating a sort of correspondence with the authors. His wife, a French scholar at Hopkins who died in 2000, also annotated her books, and Macksey told author Jessie Chaffee several years ago that he continued to "find" Catherine in the annotations she'd made in books.

"He was always engaging with the author, either in agreement or in argument," says Winston Tabb, Sheridan Dean of University Libraries, Archives and Museums. "[What you see is] essentially two minds operating together in one text—the author and a very intelligent reactor."

Equally impressive, says Tabb, is the fact that no current catalog exists: "The catalog was in Dick's mind."

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

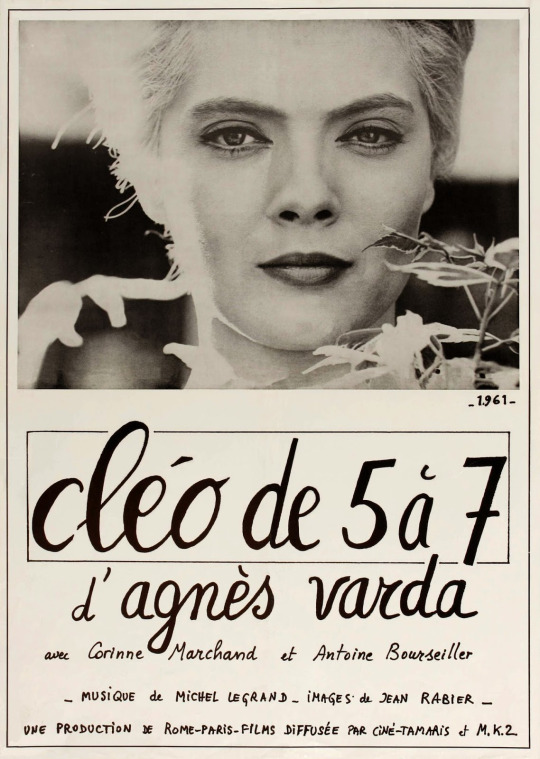

Cléo from 5-7: How the French New Wave Brought a Disruption to Commercial Cinema

Image Courtesy of Mubi

Cléo from 5-7 is a 1962 film directed by filmmaker Agnès Varda and is one of the most notable films associated with the French New Wave movement. The New Wave movement emerged in the late 1950s and was characterized by its rejection of conventional modes of commercial cinema. The formal elements of the New Wave embraced unconventional aesthetic techniques such as discontinuous editing, location shooting, and deviating from the 180-degree rule. On the contrary, mainstream French cinema aesthetics were marked by continuity editing, adherence to the 180-degree rule, and glamorous sets seen in films such as Romance de Paris (1941). Varda incorporates New Wave techniques, particularly discontinuous editing combined with recurring visual motifs of mirrors to provide a spectacle of Cleo’s existential state as she awaits her medical diagnosis.

The origins of the French New Wave can be traced back to young filmmakers who rejected “Traditional de qualité” — the commercial state of the French film industry around the mid-20th century. Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, and Jacques Rivette were among a few of the critics who became respected figures within the New Wave movement and emphasized the value of realism, innovation, and subjectivity. The emerging filmmakers who opposed “Traditional de qualité” referred to them as “cinema de papa,” translating to “daddy’s cinema.” Moreover, the conventions of “Traditional de qualité” were often marked by their literary adaptations of classic novels, high production values, and conventional editing techniques.

Along with this, the New Wave brought variety to its movement, defined by the Cahiers, (filmmakers previously mentioned) and la River Gauche (Left Bank) composed of figures such as Agnés Varda, Chris Marker, and Alain Resnais. The Cahiers group was associated with the French film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma and were heavily invested in American cinema, particularly the works of Charlie Chaplin and Alfred Hitchcock. On the contrary, filmmakers associated with la River Gauche possessed a background in documentary production, literature, and left-wing politics. Similarly, in Cléo from 5-7, these characteristics are manifested through the film’s documentary elements, including location shooting and a sense of real-time to give the spectator a realistic representation of Cleo’s psyche.

The New Wave filmmakers viewed the mainstream films of France during their time as old-fashioned and associated them with the preferences of an older generation, hence the term “cinema de papa”. Filmmaker Truffaut expanded on this perspective, stating, “This school [of film] which aspires to realism destroys it at the moment of finally grabbing it, so careful is the school to lock these beings in a closed world, barricaded by formulas, plays on words, maxims, instead of letting us see them for ourselves, with our own eyes. The artist cannot always dominate his work. He must be, sometimes, God and, sometimes his creature”. Truffaut believed conventional French cinema was rigid, artificial, and often adhered to formulaic conventions, which prompted the birth of the New Wave movement.

Agnés Varda’s Cléo from 5-7 embodies the sentiments Truffaut speaks of and attempts to diverge from a conformist approach to filmmaking. The film heavily employs discontinuity editing, particularly through the use of jump cuts that capture the disarray Cléo experiences. In the opening scene, Cléo visits a tarot reader who envisions an unfavorable fortune about her health, setting the tone of the film. As an emotionally distraught Cléo leaves the building, she is depicted descending a staircase through a series of jump cuts. The use of jump cuts in this particular scene represents not only Cléo’s fragmentation of her life but also a descent toward an existential crisis. After she makes her way toward the floor, Cléo makes her way toward a mirror, admiring her beauty in the uncertainty of death. Moreover, the sentiment of existentialism and fragmentation is solidified through Cléo’s experiences of intensive emotions, prompting her to reconsider the fabric of her existence. Additionally, this sentiment is also displayed in the second act, when Cléo takes off her wig in front of the mirror as she spirals in anger while demanding to be left alone. Cléo’s decision to remove her wig represents the unmasking of herself as she looks into the mirror and the uncertainty of death. Additionally, this scene is a manifestation of the visual motif of the mirror intensifying the spectator's awareness of Cleo’s perception of reality.

Varda invites the spectator into Cléo’s inner turmoil and existence through recurring visual motifs of mirrors, in addition to jump cuts. The mirror forces both Cléo and the spectator to confront her identity and reality. In one scene, in particular, Cléo and her friend Dorothee descend a staircase resulting in Dorothee accidentally dropping a mirror and shattering it. Cléo is shaken up by what occurred, as she believes it is an interpretation of an omen of death. This recurring theme of fragmentation, instability, and superstition is symbolized by the camera’s focus on the broken mirror pieces revealing Cleo’s reflection. Film scholar and historian Sandy Flitterman-Lewis expands on this particular scene, “As Cleo bends down toward the scattered pieces of a pocket mirror… the only portion of her reflected face visible in these Jagged fragments is her eye. This is the last image of a mirror to appear in the entire film; significantly, it announces that this image has ceased to function for Cleo as a reassurance of identity as it confirms the priority of her own vision of the world”. The motif of the mirror is employed by Varda as a technique that embodies Cleo’s complex relationship with her identity and is a reminder of her fragmented self-perception.

Varda’s use of discontinuity editing and the broken mirror symbolizes a significant shift in Cleo’s relationship with mirrors. The mirror is no longer something that reassures Cléo as it did in the opening scene, rather, it forces her to confront a new perspective on her identity. Additionally, jump cuts are employed to intentionally disrupt the continuity of the film in conventional modes of commercial cinema. The use of discontinuity editing in Cléo from 5-7 however, creates a distinctive approach to both filmmaking and continuity. The discontinued editing mirrors the fragmentation that her health status brought into her life. Although the fate of Cléo is never presented at the end of the film, as one would assume, it concludes with a sense of a transformative outlook on how she perceives life. As the spectator witnesses Cléo deal with existential concerns, she becomes more self-assured in herself, even with the fear of death looming over her.

The discontinuity editing and recurring motif of the mirror in Cléo from 5-7 becomes a means to visually express the complexity, tragedy, and uncertainty of the human condition through Cléo. Along with that, the pieces of her life are captured through jump cuts that attempt to construct Cleo’s fragmented existential state, as death may be near for her. Varda's filmmaking techniques prompt the spectator to put the pieces together to reflect the philosophy of life’s continuity found in discontinuity. Additionally, the ambiguity of the film’s conclusion also prompts the spectator to reflect on the broader sentiments while considering the chaotic uncertainty of existence. Ultimately, Cléo from 5-7 is a visual manifestation of Varda’s unique approach to filmmaking, demonstrating a nuanced narrative of life through disrupting conventional modes of cinema.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

There is a very valid reason that the whole 5-7-5 thing is the modern american/western understanding of Haikus. It's been awhile but basically translating poetry betwen languages is very difficult, translating writing is already difficult but especially poetry because there are so many things that can go into. Structure, rhyme scheme, use of literary tools like metaphors and alliteration, and other such examples. Languages are also all pretty different and are impacte dby the socieies they are used in. Cultural refrences, casual phrases all of that are hugely important. So when trying to translate poetry or forms of poetry from one langauge to another, new rules are sometimes forms/style of poetry, to try and keep the vibes/meaning of said poem or style. 5-7-5 if I remember correctly is exactly that with Haikus. There are other aspects but thats the one everyone remembers.. because its also very easy to teach that kids!!

Its a very basic rule that can be easily be seen in practice, while harder or more nebulous rules around theme or more complicated structures can be harder to teach younger kids. And since not everyone goes on to become an expert poet, most Americans associate the 5-7-5 with haikus. And thats ok.

Honestly i fell in love with the concepts of translations in poetry in college and if we were actually good at picking up languages it would have been something we would have loved doing.

I left a lot out because again not an expert and just wanted to get the basics across. But yeah, translation is a beautiful thing.(it can also be a scary thing. Because biases and such can also come into play. But its all fascinating).

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you make of the absolute MANIA for novels of 200K+ words among postwar American authors? The form didn't really exist outside of Melville, Dreiser, and Dos Passos before the 50s, but at a certain point practically everyone started doing it, whether in single or multiple volumes. It's faded, but it hasn't gone fully away. Beyond commercial considerations, why were so many novelists attracted to this kind of writing?

In the 19th century, novels were as long as they were both because of serialization and because the subscription lending-library system demanded three volumes per one novel so a single novel could circulate more readily among multiple subscribers, akin to the old DVD-lending Netflix model where a TV season would be six discs. When the lending-library system ended in the late 19th century due to competition from cheaper alternatives, short novels had a renaissance and became the backbone of modernism. I believe, however, that the legacy of the 19th century "baggy monsters" (as Henry James called them) persisted. First, on the level of artistic ideals, the long novel was still associated with the greatness of authors like Scott, Dickens, or indeed James (and novelists-in-translation like Balzac or Tolstoy, though I know less about the publishing context in those countries); no doubt length had a further prestigious association with the epic going back before the 19th century in Homer, Dante, Milton, etc. Second, on the less idealistic level of marketing, audiences still wanted, or were at least thought to want by publishers, a long immersive experience in exchange for their hard-earned money, especially in an era when there were fewer forms of media competing with books; I think this is why the pop bestsellers of the mid-20th-century, no less than the literary masterworks, were also monstrously long. That's my best guess anyway! Major Arcana, people may be interested to know, is long, but not that long: just short of 160K.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The matter I’d been tasked to investigate had to do with Kan’ichi and the nature of his return. Kan’ichi Hiraizumi came home after the bureau sent out a notice, entirely separate from the first and second waves of repatriation. He had been admitted to a military hospital during his duty. After the war, he had also been detained as a prisoner of war in a place that was well-known—even to those with limited knowledge like myself—for having far from humane conditions. Still, he sustained no major injuries or infections, and with his mental and physical health cleared, he returned home on foot, alone. Although it was a miracle worthy of celebration, this kind of story wasn’t particularly rare at the time. The problem was with how Kan’ichi looked since returning. There was little to no resemblance between photos of Kan’ichi from before the war and his current appearance, so much so that it seemed likely that a complete stranger could do a better job at mimicking him. In short, he had returned a completely different person.

Keep reading

Haneko Takayama is a writer, born in 1975 in Toyama prefecture, Japan. In 2010, she won an honorable mention in the Sogen SF Short Story Prize for UDON (Unknown Dog of Nobody); in 2016, she won the Fumiko Hayashi Literary Prize for "The Island on the Side of the Sun"; and in 2020, she won the Akutagawa Prize for A Horse from Shuri. Her works include Where I Was, "Come Gather ‘Round, People," and Lenses in the Dark. Alisa Yamasaki is a writer, translator, and interpreter based in Brooklyn, originally from Tokyo. Her writing has appeared in The Japan Times and Vice among other outlets. She was part of the 2022 cohort of the merging Translators Mentorship Program by the American Literary Translators Association.

#translation#japanese#literature#short story#fiction#short fiction#writing#haneko takayama#alisa yamasaki#the offing

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hobbit has an entire segment about the invention of golf

Also, one of the most common (and best supported imho) interpretation is that LOTR is a mythology for our world - these are things that supposedly happened in our past. The books even tell us that Hobbits are still around in our time - they use magic to hide from us Big Folk. Me own dad’s interpretation - and he’s not a literary scholar - was that Tolkien was explicitly wanting to make some mythologized past Britain akin to Wagners version of Norse mythology.

I think this is a debated topic among Tolkien aficionados, but I’ve always understood it as the Red Book of Westmarch was copied down by a Gondorian scribe from Bilbo’s manuscripts. Edits were made by that scribe to render the Hobbit’s names in a more common tongue. Then Tolkien purports to translate this ancient manuscript, just as he did many medieval Anglo Saxon texts, into English. He also makes changes in his translation (which is true of *any* translation. translation is a creative process)

So you see here two clear explanations:

They weren’t actually potatoes, that was just the easiest way to refer to a starchy vegetable. Culinary it serves the same purposes, and probably tastes the same. People are wildly imprecise with common names for fruits and veggies.

They are potatoes. Tolkien had a strong grasp on western history; unfortunately, I doubt the finest of intellectuals in the 20th century west really put much thought into South American cultures - so we can’t really fault him for slighting the accomplishments of the potatoes’ domestication. (I surprise a lot of people when I tell them ketchup, pizza and pasta didn’t really have tomato sauce until roughly the late 19th century - people thought tomatoes were poisonous!) Potatoes are such a ubiquitous foodstuff by Tolkien’s time that maybe Eru Iluvatar sang them into existence for a bit and then they were remade later by awesome ancient Peruvian people.

But mostly, I disagree with Tolkien making his world fundamentally alien to ours. He’s presenting to us pseudo-historical documents of a world he has created, which must inherently draw from his own experiences (another famous connection is his experiences of war and his descriptions of Orcs; World War 1 is a part of the work)

Insinuating Tolkien was writing some sort of xeno fiction flattens his work. They ultimately eat potatoes because potatoes are what Tolkien ate growing up, and he associates with home. Everything associated with the Shire is based on his childhood.

Tolkien was a scholar, and he wrote like a scholar who has translated and interpreted tons of historical primary texts. He puts poems in because he loved poems.

not even JRR Tolkien, who famously developed the concept of the Secondary World and firmly believed that no trace of the Real World should be evoked in the fictional world, was able to remove potatoes from his literature. this is a man who developed whole languages and mythologies for his literary world, who justified its existence in English as a translation* simply because he was so miffed he couldn't get away with making the story fully alien to the real world. and not even he, in extremis, was so cruel as to deny his characters the heavenly potato. could not even conceive a universe devoid of the potato. such is its impact. everyone please take a moment to say thank you to South Americans for developing and cultivating one of earth's finest vegetables. the potato IS all that. literally world-changing food. bless.

77K notes

·

View notes

Text

Join us for the last Another Way to Say of 2024 at Molasses Books this Friday, December 13 at 8 PM for works in translation from Argentinian Spanish, Japanese, and French, namely Alexis Almeida's translation of Roberta Iannamico's Many Poems (The Song Cave), like "coming across a vibrant patch of wildflowers unexpectedly," (Mónica de la Torre), Amy Obermeyer's translation of Hirabayashi Taiko's (timely?) "At the Charity Clinic" (Barricade: A Journal of Antifascism and Translation), and Kenneth Reveiz's translations of poetry from Our Americas by Stéphan Bouquet (seeking publisher!): "Stretched out along the poems / like entire days i waited / stretched out amongst the withered hand of the ferns, / and the crinkled sound of the leaves" ("The Trees in Succession" for Circumference Magazine).

Read on for reader bios***

Alexis Almeida grew up in Chicago. She is the author of the chapbooks I Have Never Been Able to Sing (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2018), and Things I Have Made a Fiction (Oversound, 2024). Her translation of Roberta Iannamico's Many Poems is recently out from The Song Cave, and her first full-length collection, Caetano, is forthcoming from The Elephants in 2025.

Amy Obermeyer was the first managing editor for Barricade: A Journal of Antifascism and Translation, where she is a founding member of the editorial collective. She is particularly interested in early twentieth-century women's literature, and translates primarily from Japanese into English. For her day job, she serves as Director of Student Affairs and Associate Faculty at NYU's Gallatin School of Individualized Study and her literary scholarship focuses on questions of gender and subjectivity in Japanese and Latin American fiction.

Kenneth Reveiz is an award-winning poet, screenwriter, and literary translator from New York City who works in service of racial and economic justice. Honors include fellowships from Yale University and CalArts, publications by the British Film Institute, Queer.Archive.Work, and Latin American Literature Today, and artist residencies from the Wassaic Project (2x), Fieldwork: Marfa, the California Institute of the Arts, and Yale. They are the author of the “dazzling” and “frontal” poetry collection MOPES, published by Fence Books as winner of the Fence Modern Poets Series Prize.

0 notes

Text

TIMOTHY SNYDER

MAR 7

The attempt to humiliate Volodymyr Zelens'kyi in the Oval Office a week ago was an American strategic collapse. It heralded a new constellation of disorderly powers, obsessed with resources, seizing what they can. Inside that new disaster is something old and familiar that we might prefer not to see: antisemitism. The encounter in the White House was antisemitic.

I am historian of the Holocaust. I was trained by a survivor. Jerzy Jedlicki was nine years old when the Germans invaded, and fourteen when he emerged from hiding in Warsaw, and a prominent Polish historian by the time we met. He talked to me about antisemitism for decades, from the time of the breakup of the Soviet Union until his death in 2018. The way that I reacted to the scene in the Oval Office, and how I have pondered and considered it since, have to do with my research, but also with him.

Jerzy survived the Holocaust because his mother Wanda, a literary translator, refused to go with her children to the Warsaw ghetto. Thanks to her courage and ingenuity, and to others who helped her, he and his brother survived. Jerzy's father was murdered, like more than three million other Jews in Poland. The family history emerged bit by bit, as we became friends, as some of his own colleagues wrote memoirs of childhood survival, as my own interests turned towards the war. During my research, I found a recollection, by his mother, of their time in hiding in Warsaw. It turned out that he had helped her to write it.

In post-communist Poland, in the 1990s and 2000s, Jerzy was an activist against antisemitism and xenophobia, and I attended at his urging some of the meetings of the association he helped direct. The entire time, I think, he was trying to train my eye.

Some forms of what he defined as antisemitism had to do with his memories of occupation. Jews had to show deference. Germans mocked the ways Jews dressed. That was before they were sent to the ghetto and murdered. Jews were scapegoated, made responsible for what the Germans wished to do anyway.

Some characteristics of antisemitism as he described it were more abstract. Jewish achievement was portrayed as illegitimate. Jews only gained success, antisemites say, by lying and propaganda. If a Jew was prominent, that only proved the existence of a Jewish conspiracy, and thereby the illegitimacy of the institution where the success was achieved. A prominent Jew was always, went the antisemitic assumption, motivated by money.