#Africa Marketing Translation

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Y’know, once I had a student who wrote an essay on the positive effects of RuPaul’s Drag Race and the queens in that show. And when they were talking about the specific queens, they kept randomly switching the pronouns. And I had a really hard time making them understand that they should stick to one pronoun, I don’t care which one, when talking about a specific person, because for laypeople (their potential readers) will get confused otherwise.

And now in this book we have an enemy, a country/tribe, who are referred to as Nupe and Tapa, the two terms used interchangeably without rhyme or reason, without the author ever mentioning that these two refer to the same people, it’s just one they call themselves, and the other is what the neighboring people call them.

#translation#the author uses all these term associated with West Africa#in a YA book written for the English/American market#without ever stopping to explain what the terms mean

1 note

·

View note

Text

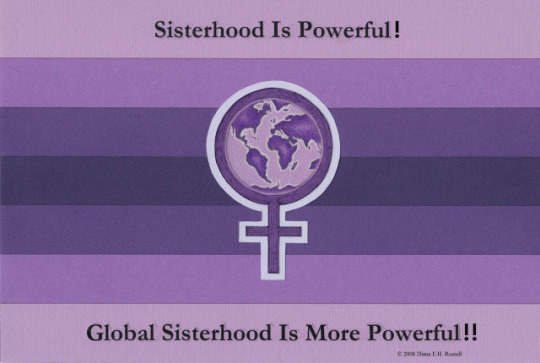

I've revotalized a version of the (Radical) Feminist Sisterhood Flag originally made by Diana Russell!

OG flag by Diana

Dr Diana EH Russell, PhD, (November 1938 to July 2020) was a feminist writer and activist from Cape Town, South Africa. She was an anti-apartheidist, women's rights, and human rights activist.

She was a triple alumni who attended University of Cape Town, London School of Economics, and Harvard University.

She organized (along with other feminists) the first International Tribunal on Crimes Against Women, which was held in Brussels, Belgium.

She was anti-porn, anti-sex trade (or anti rape-economy), and properly defined femicide as the killing of human females because they are female. There is so much more about her to learn, I recommend dianarussell.com

Attention bilingual people:

Diana Russell really wanted her message of global sisterhood to be spread to as many feminists as possible. The uniting and collective organizing of women is how we secure more rights and begin to structurally reorder society towards female liberation. Diana's message unfortunately is only available in English so if you can reblog with a translation of the following, I'm sure Diana's spirit would much appreciate it.

Dear Visitors and Supporters, I'm convinced that the wide distribution of this feminist flag would help to bring attention to feminist actions, and to facilitate international feminist solidarity, thereby empowering our struggle to combat misogyny and sexism in all its oppressive and discriminatory forms. I regret that the words can only be in one language; but I have seen no good alternative to this limitation. I'm searching for a fabulous feminist organizer with the vision, energy, time and motivation to take on the important job of marketing this beautiful feminist flag. If you're interested in helping with this project, please contact me via my contact page. Thank you! —————— 2020 NOTE: Diana has passed away so she can no longer work on this project that was very important to her. But she would definitely want other feminists to take up the cause of creating a feminist flag, either using her flag design (please credit her if you use it), or another design. So please feel free to do so! Thank you! ❤️

In my contribution, I've created a high quality rendition of Diana's initial global sisterhood flag with essentially more vibrancy. I've also created a version that contains the radical feminist symbol I've created.

1.

This is definitely my favourite out of the set. Image ID on alt text.

2.

3.

4.

#radical feminism#radical feminist community#radical feminist safe#radfem vex#vexillology#anti capitalism#radblr#radical feminists do interact#diana russell#feminism#anti sex industry#anti rape economy#radical feminists do touch#rad fem#gender abolition

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Organizing more notes. Some recent-ish books on German colonialism and imperial imaginaries of space/place, especially in Africa:

----

German Colonialism in Africa and its Legacies: Architecture, Art, Urbanism, and Visual Culture (Edited by Itohan Osayimwese, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2023)

An Imperial Homeland: Forging German Identity in Southwest Africa (Adam A. Blackler, Penn State University Press, 2023)

Coconut Colonialism: Workers and the Globalization of Samoa (Holger Droessler, Harvard University Press, 2022)

Colonial Geography: Race and Space in German East Africa, 1884-1905 (Matthew Unangst, University of Toronto Press, 2022)

The Play World: Toys, Texts, and the Transatlantic German Childhood (Patricia Anne Simpson, 2020)

Learning Empire: Globalization and the German Quest for World Status, 1875-1919 (Erik Grimmer-Solem, Cambridge University Press, 2019)

Violence as Usual: Policing and the Colonial State in German Southwest Africa (Marie A. Muschalek, 2019)

Revenants of the German Empire: Colonial Germans, the League of Nations, and Imperialism (Sean Andrew Wempe, 2019)

Rethinking Black German Studies: Approaches, Interventions and Histories (Edited by Tiffany Florvil and Vanessa Plumly, 2018)

German Colonial Wars and the Context of Military Violence (Susanne Kuss, translated by Andrew Smith, Harvard University Press, 2017)

Colonialism and Modern Architecture in Germany (Itohan Osayimwese, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2017)

---

German Colonialism in a Global Age (Edited by Bradley Naranch and Geoff Eley, 2014) Including:

"Empire by Land or Sea? Germany's Imperial Imaginary, 1840-1945" (Geoff Eley)

"Science and Civilizing Missions: Germans and the Transnational Community of Tropical Medicine" (Deborah J. Neill)

"Ruling Africa: Science as Sovereignty in the German Colonial Empire and Its Aftermath" (Andrew Zimmerman)

"Mass-Marketing the Empire: Colonial Fantasies and Advertising Visions" (David Ciarlo)

---

German Colonialism and National Identity (Edited by Michael Perraudin and Jurgen Zimmerer, 2017). Including:

"Between Amnesia and Denial: Colonialism and German National Identity" (Perraudin and Zimmerer)

"Exotic Education: Writing Empire for German Boys and Girls, 1884-1914" (Jeffrey Bowersox)

"Beyond Empire: German Women in Africa, 1919-1933" (Britta Schilling)

---

Advertising Empire: Race and Visual Culture in Imperial Germany (David Ciarlo, Harvard University Press, 2011)

The German Forest: Nature, Identity, and the Contestation of a National Symbol, 1871-1914 (Jeffrey K. Wilson, University of Toronto Press, 2012)

The Devil's Handwriting: Precoloniality and the German Colonial State in Qingdao, Samoa, and Southwest Africa (George Steinmetz, 2007)

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abstract economic theorizing typically asserts that prices coordinate the best rational resource allocations and that prices reflect the best information available while the market bets of the smartest people with skin in the game ensure efficiency. But Russell exposes this as flawed fig-leaf logic. He quotes one market participant (an insider “traitor”) confessing the “irrationality of commodity prices.” Algorithmic trades are shots fired between swanky skyscrapers as “hedge funds raid each other’s coffers,” collaterally taking calories out of the mouths of poor kids. Besides, only the absurdly blinkered could imagine that global food is used rationally or efficiently—never mind ethically. Grain used for biofuels “eats up enough food to feed 1.9 billion people annually.” Rich-world pets are less food insecure than the 2.4 billion people (1 in 3 humans) classified by the U.N. as lacking “access to adequate food.” Seventy-seven percent of global farming land is used for livestock which mostly the rich consume (or waste). Indeed, 30-40 percent of all food grown is wasted. Market forces aren’t in the business of fixing this sort of massive and malicious malarkey. For instance, analysis of market-oriented African Green Revolution projects, which aimed to “catalyze a farming revolution in Africa” by helping farmers in 13 countries over a period of 15 years switch from traditional subsistence-and-barter methods to raising monocrops for commercial export, concluded that they led to 31 percent higher undernourishment. As Timothy A. Wise reports in Mongabay News, this large-scale effort was led by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the U.S., U.K., and German governments, with the goal of doubling “yields and incomes for 30 million small-scale farming families while halving food insecurity.” As much as $1 billion per year went into the effort. But integration of small farmers into international markets put these small farmers under the same pressures that for-profit farmers face the world over (but without rich-nation safety nets). They’re at the mercy of volatile global pricing but have high fixed costs of inputs like commercial seeds and fertilizers. The net result was that even when yields rose, they often “failed to translate into rising incomes.” Many of these small farmers could now neither barter traditional crops with neighbors, nor did they have sufficient income to buy local food, a punishing recipe for food insecurity (further details are available in Wise’s coverage). The bottom line is that markets only feed you if you can pay (to match the bets of invisible-hearted hedge-funders or manufacturers of rich-world pet food).

163 notes

·

View notes

Note

[1] `there are often translations available in other languages long before English ones` This is really interesting! I'm familiar with translation in games, where english is often a very early target (a small game might get 0-5 translations, depending on amount of text) because the size of the market is larger.

[2] Do you happen to know why this is different for books? Is it faster to come to a deal about publication rights for some other languages to get started on the translation? Is translation to english harder (at least from French) than to say, Spanish?

The literary translation situation has long been very dismal in the English-speaking world! I don’t know a lot about video games, but are localisations provided by the company that makes the game? Because if that's the case it makes sense that games would get translated into English as a priority. For literary translations which are imported rather than exported, other countries have to decide to translate a foreign author and anglo countries (US, UK and Canada at least) are not very interested in foreign literature. There's something known as the "3% rule" in translation—i.e. about 3% of all published books in the US in any given year are translations. Some recent sources say this figure is outdated and it’s now something like 5% (... god) but note that it encompasses all translations, and most of it is technical translation (instruction manuals, etc). The percentage of novels in translation published in the UK is 5-6% from what I’ve read and it’s lower in the US. In France it's 33%, and that’s not unusually high compared to other European countries.

I don't think it's only because of the global influence of English* and the higher proportion of English speakers in other countries than [insert language] speakers in the US, or poor language education in schools etc, because just consider how many people in the US speak Spanish—I just looked it up and native Spanish speakers in the US represent nearly 2/3rds of the population of France, and yet in 2014 (most recent solid stat I could find) the US published only 67 books translated from Spanish. France with a much smaller % of native Spanish speakers (and literary market) published ~370 translations from Spanish that same year. All languages combined, the total number of new translations published in France in 2014 was 11,859; in Spain it was 19,865; the same year the US published 618 new translations. France translated more books from German alone (754) than the US did from all languages combined, and German is only our 3rd most translated language (and a distant third at that!). The number of new translations I found in the US in 2018 was 632 so the 3% figure is probably still accurate enough.

* When I say it’s not just about the global influence of English—obviously that plays a huge role but I mean there’s also a factor of cultural isolationism at play. If you take English out of the equation there’s still a lot more cultural exchange (in terms of literature) between other countries. Take Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead; it was published in 2009, and (to give a few examples) translated in Swedish 1 year later, in Russian & German 2 years later, in French, Danish & Italian 3 years later, in English 10 years later—only after she won the Nobel. I’m reminded of the former secretary for the Nobel Prize who said Americans “don't really participate in the big dialogue of literature” because they don’t translate enough. I think it's a similar phenomenon as the one described in the "How US culture ate the world" article; the US is more interested in exporting its culture than in importing cultural products from the rest of the world. And sure, anglo culture is spread over most continents so there’s still a diversity of voices that write in English (from India, South Africa, etc etc) but that creates pressure for authors to adopt English as their literary language. The dearth of English translation doesn’t just mean that monolingual anglophones are cut off from a lot of great literature, but also that authors who write in minority languages are cut off from the global visibility an English translation could give them, as it could serve as a bridge to be translated in a lot more languages, and as a way to become eligible for major literary prizes including the Nobel.

Considering that women are less translated than men and represent a minority (about 1/3) of that already abysmally low 3% figure, I find the recent successes of English translations of women writers encouraging—Olga Tokarczuk, Banana Yoshimoto, Han Kang, Valeria Luiselli, Samanta Schweblin, Sayaka Murata, Leila Slimani, of course Elena Ferrante... Hopefully this is a trend that continues & increases! I remember this New Yorker article from years ago, “Do You Have to Win the Nobel Prize to Be Translated?”, in which a US small press owner said “there’s just no demand in this country” (for translated works); but the article acknowledged that it’s also a chicken-and-egg problem. Traditional publishers who have the budget to market them properly don’t release many translations as (among other things) they think US readers are reluctant to read translated foreign literature, and the indie presses who release the lion’s share of translated works (I read it was about 80%) don’t have the budget to promote them so people don’t buy them so the assumption that readers aren’t interested lives on. So maybe social media can slowly change the situation by showing that anglo readers are interested in translated books if they just get to find out about them...

#ask#anyway it's difficult to find accurate stats for translation and compare between countries because some % you see are#for all translations and as i said technical translations / computer manuals etc make up the bulk of it#some % are averages over decades; others only for fiction or for novels & poetry etc so you end up comparing apples and oranges#but the fact remains that the three percent website (translation database) was able to list every single literary translation#published in the us year after year and it was never higher than 600-ish titles in the 2010s. it's not great#when you see much smaller countries release translations in the thousands or tens of thousands#it's also not a huge improvement over the 400-ish yearly US translations in the 00s#but they haven't released numbers for the past few years and maybe the situation is a bit better now

366 notes

·

View notes

Text

Back in the 1980s, when polenta was the hot new item on restaurant menus, I was eager to try it. I knew it was a traditional Italian dish, but it was foreign to everyone else, including me. I bought a package of cornmeal, began the preparation, and when it was done I realized I had been eating it all my life. It was the same dish Jonathan Harker ate before his encounter with Count Dracula in Bram Stoker’s novel, known in the American South as “cornmeal mush” and “pap” in South Africa. But I knew it as mamaliga, which had been a staple in my grandma’s Romanian kitchen.

Because mamaliga was such an essential in our lives, I didn’t realize that most of my Jewish friends had never heard of it. The hallways in the buildings we lived in all had the same familiar scents of Ashkenazi staples we all knew — chicken soup, challah, braising briskets, and roasting chickens. Shared values and menus.

Except when it came to mamaliga, which I learned was limited to those of us whose ancestors were from Romania.

While our family was dining on cornmeal mush, everyone else was eating kasha varnishkes, a dish I ate regularly only after tasting it at my future mother-in-law’s house (it was love at first bite).

It all has to do with geography, I think. Polenta/mamaliga is based on cornmeal, which had been unknown anywhere except the Americas, where corn is indigenous. Christopher Columbus and other Spanish and Portuguese explorers brought corn to western Europe and Africa, where it flourished. Cornmeal became a staple.

Turkish traders noticed corn grain in the markets of Africa and brought some “granoturco” back to Southeast Europe, including the region we now know as Romania, which then belonged to the Ottoman Empire. In 1692, a Romanian nobleman tried some, thought it worthy, and introduced it to Romania. It became the country’s national dish.

A few years ago I visited “the old country,” including the city of Iasi, where my grandparents were born, and laid stones on the graves of my great-grandparents who are buried in the one remaining Jewish cemetery (when my grandparents lived there, the city was about one-third Jewish).

Naturally we sampled mamaliga, which is ever-present on every restaurant menu. It’s usually served as a side dish, much like any starch, but in my childhood, my grandma, and later on my mother, served mamaliga in a multitude of ways, including our favorite, mamaliga cu branza si smetana – mamaliga with cheese and sour cream, served for lunch or as a side dish at dairy dinners.

In my own kitchen, I’ve learned that mamaliga is incredibly versatile. I’ve used it as a substitute for potatoes, noodles, and rice (complete with butter, sauce, or gravy). I’ve served it as a full meal, as a topping for brisket or chicken pot pie filling, with mushroom ragout, and with caramelized onions and cheese. I’ve even mixed it with molasses and cream to make a quick Indian pudding.

The leftovers are spectacular, too. In fact, in Romanian households they make extra mamaliga to pour into a loaf pan, let it firm up, and then cut slices to fry to crispy goodness. I’ve served fried slices of “Romanian toast” for breakfast, topped them with gravy or cheese for lunch, or with a fried egg for dinner.

It’s no wonder that the Romanians called dried ground corn mamaliga, a word that translates to “food of gold.” It’s a tribute not merely to the grain’s beautiful yellow color, but to its adaptability. Whatever you call it, this dish is an enduring winner and, as far as I am concerned, another treasure of the Ashkenazi kitchen.

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Minority Ambassadorship

I need to get something off my chest and it’s been bothering me for a while but I could never figure out the right words. So I’m just going to shoot my shot and clarify if need be. I’m all for representation and all that but the way it’s been handled in recent years.

The thing that helped me finally click all the pieces together was the recent Spider-Man game. While Peter has a proper adventure Miles is not. He’s doing side jobs and while obviously showing he’s part of the community, his story also falls into a dangerous trap I keep seeing. They (the writers) make him the ambassador of his culture no one is the entirety of their culture but writers keep doing this stuff.

White folks in stories have the freedom to be anything, like anything and feel anything. They’re organically made all the time. But the moment a different race takes the stage they’re chained to the cultural stereotypes. Even Wakanda has just become “Africa the Country” theirs no uniqueness to it, it’s populated by every conceivable African Stereotype. Heck I remember a few years back a marvel comic was made with Miles being made the new Thor and IMMEDIATELY Asgard turned into a Ghetto and it was the most racist joke I’ve seen in a while.

This isn’t new by any means. More often than not when an American enters an anime they’re stereotypically American. Wearing the American flag, usually blond for some reason, constantly swearing and won’t shut up and if we’re feeling REALLY spicy we can make them big and scary.

That habit of writers though can create a feeling of “otherness” to anyone that isn’t you and can actually reinforce stereotypes. You’re not your culture and you shouldn’t be pressured into that mindset. You can absolutely be influenced by it but people aren’t just ambassadors to their culture. That’s ignorant to the highest degree.

Considering many games that do this are affiliated with Sweet Baby Inc. I’m not surprised but it just means we should fight harder against it.

Sweet Baby Inc. is one of those companies that’s basically “sensitivity writers” they show up to punch up stories to make them more “inclusive” but what this usually means is make them subtly racist, homophobic and authoritarian and barring that making a story less interesting. They’re involved with almost every failure within recent types in the gaming market including Suicide Squad and Last of Us 2. They even worked on Spider-Man 2 and the Miles Morales Game. Both of which you can see what I’m talking about by making Miles the Ambassador of Black People and Harlem. They were even involved with the Spanish Translation of Spider-Man 2 which upset that entire part of the world because they used words like Latinx which is considered a slur and an act of colonialism as white people try to force them to change their own language.

Sweet Baby Inc. and its employees are a bunch of racists, homophobes and Authoritarians pulling the greatest grift of all time by pretending to not hate those people and acting like they don’t want to control how people think. The mask has come off frequently and only recently has it come off in such spectacular fashion that a lot of the internet is starting to notice myself included.

In conclusion though, don’t be a racist and let characters of other races and sexual orientation be actual people instead of being the ambassadors of their people. Don’t support bigots that pretend to be on your side and be mindful of people like that. Also don’t buy anything Sweet Baby Inc touched because they’re all of those things.

#story writing#stop normalizing racism#racism#stereotypes#harmful stereotypes#last of us part 2#suicide squad#spider man 2 ps5#miles morales#sweet baby inc

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

found my old douk-douk from many years ago! that carbon steel is looking a little rough. gonna give him a little TLC.

when I bought him, these were like 25 bucks. Now they're 36 bucks.

ramble under the cut

Douk-Douks have an interesting history. A French dude named Gaspard Cognet wanted to capture the pocket knife market in the French Pacific colonies (specifically in Melanesia). He needed a marketing draw that would boost brand recognition and catch local eyes, though. This was in 1929, so he went to the library and found this in an illustrated dictionary:

...and he was like "wow, this is a thing from an island in Melanesia so obviously all of Melanesia will love my knife if I put it on there. It must be important if it's one of the only Melanesian things in the dictionary, right? Even though my target market is mainly in New Caledonia, im sure they will will all recognize this niche figure from one culture from one peninsula on one island on the opposite end of Melanesia and that this isn't going to come off weird or cause misunderstandings--"

except he totally didn't say that. The dictionary probably just said "fierce melanesian spirit thing" and had a cool drawing, and that was good enough for Gaspard. He was, after all, a white guy trying to market products to black people he had never met who lived as his country's colonial subjects on the other side of the planet. I doubt he considered the differences in their respective experiences and cultures at all. If he did, he probably would've made some different choices.

Anyways, the product flopped. It did, however, succeed in French possessions in Africa. People seemed to like them as work knives, and apparently they were sharpened into razors as well.

One promotional photo shows hunters from an unspecified "pygmy" culture kneeling around a bongo carcass with knives and a sign reading "The Douk-Douk Among the Pygmies." Most of the men look a bit disinterested. They are all wearing the same shorts and t-shirts, and the knives are shiny and new. It's honestly a very strange and contrived picture. There's a lot going on here.

During the Algerian War of Independence, the FLN supposedly would hammer the lips of the handles together to convert them into fixed-blade knives. Some French guys online say that they would cut informers' noses off and stabbed soldiers in the Casbah with them. I'm sure the war was brutal, but I don't know if this story about the douk-douks is actually true. It gets repeated a lot online (especially by sellers), but the only actual source I can find is an untranslated memoir by a French guy.

(The title of this memoir is "Il était une fois mon Algérie à moi: Biographie," which translates to "Once Upon a Time There Was My Own Algeria: A Biography." It seems to be self-published. We are clearly dealing with some reliable stuff here!)

This is a consumer product that was made to sell to lower-income people in overseas colonies. How do you even tell where the history ends and the marketing and weird colonial mythology begin? I don't know what is really true except that people bought it and used it. I wonder if there are things written about it in languages I can't read or even struggle through. That would be the really interesting stuff!

It's a neat little knife, regardless.

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

let's call hybe and bighit's neglect of south american countries what it is : racism. I am not saying the tannies are racist but that company refusing to take their latino fans into consideration despite the numbers they give them on itunes, spotify, apple music is vile. Countries like Colombia, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Peru are safe and beautiful, have great concert infrastructure and atmosphere & rich musical legacy. Like these countries were the main reason Bad bunny was the number one male artist for a while. They're literally leaving money on the table ffs.

However their neglect of europe and australia is pure stupidity ; they probably thought these places would just say ' USA likes them, so i'll stan them ' but that has not been the case. Europe loves cheesy and bright pop music like BWL - too much focus on the USA prevented Bts from being more global and mainstream :( still they're pulling insane numbers on spotify and apple music

I heard MOTS:7 tour was supposed to include stops in India and Africa :( idk if we'll ever get a tour on that scale again and fuck covid man...

Sure, here's a translation into British English with necessary grammatical and fluency corrections:

I don't think it's about racism, though it is probably xenophobia. Market ignorance as well. Perhaps classism; it could also be viewed from that perspective.

The problem is this mentality, which even exists in the West, that only the American market and some European countries matter. Obviously, the fact that these are countries with significant economies and that, in one way or another, they are the "leaders" of the world also has an influence. However, I believe that in the musical world, it shouldn't be or be seen this way, especially when everything is digitised.

Not going to countries like Australia, New Zealand, or countries in Africa is a missed opportunity to be the first in many cases or one of the few to visit those countries. I know that in terms of concerts, it is a bit more complicated, but as I said before, not impossible. It is really a pity overall.

14 notes

·

View notes

Note

Sorry, I have returned with another heavy representation related question

Do you find it odd that the push for black characters is disproportionately higher than the push for black culture?

Aside from all the interesting history and cultures in Africa, there's aboriginal Australians and Afro-Brazilians who invented an entire martial art to escape slavery and fight off colonizers. Capoeira is awesome btw

Why represent black people, but ignore black culture?

Good question!

I don't know if I have a great answer to this, but if I were to start anywhere, it's that part of it is definitely because of just how significant the U.S. is (or at least is treated) in how culture moves, shapes, and released. In the risk of sounding like a baby leftist eager to use buzzwords all the time, honestly it all ties back to capitalism. What sells, generating profit, buying out smaller companies for their better critical acclaim-to-commercial success ratio.

And a notable cog in the capitalist machine is what U.S. corporations do as, despite being an extremely young country, it is a superpower with massive amounts of land and wealth that it hoards. It stands to reason that anything that comes out of the U.S. can and will be marketed and capitalized off of if it reaches a certain point of popularity and/or notoriety.

Black American culture is one part in that American capitalist cog, where, despite being a proported bastian of modern day human rights, the U.S. values the dollar of the world's citizenry over actually making efforts to improve the damn planet they live on.

And true to that type of attitude, that resulted in Black American art at first being mocked ("a Negro wrote a book? yeah and pigs can fly haha"), then the 'emancipation' happened (ignore the fact that slavery technically still exists under the 13th amendment as punishment for crime and doubly ignore which racial population is drastically over-arrested and accused for crimes of which they either didn't do or have outrageous sentences compared to the crime committed e.g. weed posession, the U.S. doesn't want you to think about that) /s

After mockery, came mockery+profit, such as minstrelsy, and later whitewashing and theft of cultural aspects (music is a big one) at the expense of Black Americans not getting their due.

Then the Civil Rights era happened (ignore how socialist MLK was that's not good for the money making machine) and with that led to a more rapid dissolution of segregation, and that meant Black people can be on screen and can sell stuff to other Black people. Later, Black culture started becoming really cool and hip to non-Black people in America. White boy hip-hop, white guy and gal R&B (Timberlake, P!nk's first album), whatever the hell X-tina was doing with those damn cornrows lmaoooo.

And this corporate co-opting of the culture has proven to be a major money maker for the past 5 decades, and is still perpetuated today. Any accusation, claim, or slander of "Gen Z/TikTok/Stan Twitter" language is how Black Americans have been talking for decades upon decades (I wish I could remember there was this show from early days of color tv that had a black cop do a "white to black" translation as a joke on the show and he said "my partner wants the tea on the old bird" cuz that's really a big indicator of that fact.)

The double edged sword of this, is of course that this is a way of speaking, culture, art, and lifestyle that a group of people live, and despite it continuing to be marketable as trendy and cool, Black Americans are still not really getting the lion's share of praise for it, because well... the U.S. is still systemically racist and any trend that starts from a non-lighter skinned cultural/ethnic group that can be whitewashed, will be in order to sell more. Unconscious bias as a result of being raised in a country built upon injustice and genocide is something I don't imagine will be undone for even the next century or two.

Getting to the actual point you asked about, it's because of the topics in my aforementioned ramblings why it's most likely harder/less seen for Black culture to be pushed over just Black/dark skinned characters.

On one hand, yes, I did mention how Black culture has been commercialized and commodified, but 1) lots of overt racists still exist and celebrating or even explaining something adjacent to Black culture can and will set them off cuz "THE WOKE AGENDA, STOP PREACHING IN MY FAVORITE FRANCHISE GRRRR" which means a not-insignificant amount of money can potentially be risked since those types are in more spaces than you'd expect, 2) there's extra work to be done now as to not offend the particular culture being portrayed, which is a good thing to do, but sadly often results in said culture just being cut from a character to avoid the work because time spent on sensitivity can be taken as time wasted on not improving other parts of the product, and 3) I know this is a big accusation to make, but... people consume more subpar and shallow stuff than they're willing to admit. Obviously there's nuance to stuff; enjoying a children's show with black characters in it as a kid and thinking it's good representation is no problem whatsoever, in fact I encourage it more because diverse cartoons set developing kids' brains up extremely well for a progressing society.

But there's a very noticeable deluge of applause from even mature audiences when there's a major involvement of a Black person in general that rings hollow because there's usually nothing significant about it other than the produce may not have had Black involvement before. I myself am not immune to this of course, because my favorite game series' are Fire Emblem and Xenoblade, and only in the most recent entries of both did they feature unambiguously Black characters inspired by either cultural taste aesthetics (Timerra and Fogado from Latin America) or physical features (Taion's hair, nose and lips), and I basically fucking cheered cuz those are my babies and they look so cute. BUT, again, those were the most recent entries in series where characters darker skinned than a paper bag (or gray-ish brown) that weren't just insignifanct NPCs were hard to find, and in FE's case got outright fucking offensive (Danved/Devdan).

I suspect this is a similar sentinment with non-American Black culture as well, as since Black American culture is still a controversial celebration, African, Carribean, Black Latin, or Aboriginals of Australia have the same reputation except exacerbated by xenophobia, weird fetishy-exoticism being placed on them, or flat out being unknown to the greater zeitgeist at the moment. Certainly doesn't help that the major powers of entertainment are located in the places that ruined or exterminated those same Black cultures :/

TL;DR: Capitalism profits off of culture, but not too much because that risks losing more money than its worth, so the compromise is usually slapping a "they're black" sticker on whatever they're trying to sell and unfortunately it works a lot of the time because being an uncritical consumer is something we've been raised to deal with as a part of life.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Congolese cinema and Patrice Lumumba

It’s no surprise that African cinema, especially Congolese cinema, isn’t a part of the syllabus of film studies at several universities outside Africa, and Patrice Lumumba hasn’t yet found a space in most history and political science textbooks used by the Western-centric education system in many wealthy and developing countries (including mine).

There is only a handful of scholarly work on Congolese cinema available in English, and most of them are focussed on the evangelisation of the Congolese people, in Belgian Congo, by the male missionaries through mobile film screenings using the “cinema van” built by the British before World War Two to spread propaganda among “primitive peoples”.

Gansa Ndombasi addresses the lack of available information about Congolese cinema and lays out its history in his book La cinéma du Congo démocratique (2008).

The filmmakers of the films screened in Belgian Congo – which used to be the personal property of King Leopold ll after the European countries divided the African continent among themselves at the Berlin Conference of 1885 until Belgian government took over the administration of Congo from him in 1908 and turned it into their colony – showed black characters as “so Manichaean and caricatured that local populations could not identify with them”. The films, religious and nationalist in nature, including the imported Hollywood, Bollywood, and East Asian films – shown to the Congolese community between the early 1960s and 1997 were strictly governed by the interests of Mobutu, the then (1965-1991) head of the state who facilitated the West's access to Congo’s resources as he assumed his dictatorship over Zaire, a name he adopted for the nation. Film commentators, who translated the film’s dialogues into the local language and helped the community understand the story of the film they were being shown, existed well into the post-colonial period since the colonial times. The period following the end of Mobutu’s rule was marked by an increase in Revivalists’ religious films and independent films co-produced by the unrepressed Congolese diaspora with countries like France and Belgium. Ndombasi has called this cinematic period “Cinéma Congolaise” when Zaire became the Democratic Republic of Congo and, unlike the other two male-dominated periods of filmmaking, women began to make documentaries and short films. Recently Macherie Ekwa Bahango made her debut feature film, Maki'La (2018), on the lives of the marginalized street children and violence against women in Congo.

Both French Congo and Belgian Congo gained independence in 1960, but a Congolese feature film wasn’t produced until 1987; the 1980s being the period when NGOs started flocking to Africa. Some of those charitable organisations are accused of trying to establish “market-friendly human rights” and profiteering the resistance of the people in the exploited conflict-plagued continent.

The first Congolese prime minister and a visionary pan-Africanist whose anti-colonial revolution was crucial in freeing Congo from Belgium, Patrice Lumumba, was murdered in 1961 along with two of his colleagues, by the “agents of imperialism and neocolonialism” because the three martyrs “put their faith in the United Nations and because they refused to allow themselves to be used as stooges or puppets for external interests”. During the cold war, Lumumba’s plans to nationalize Congo’s resources to enhance the country’s economic growth was unfavourable to the West, especially because Congo provided the uranium used in the atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki – an outcome of Einstein’s fateful letter. Lumumba’s assassination committed with full support from the United States and Europe, in his aim to prevent the “economic reconquest” of the resource-rich Congo by the United States, Belgium, and the United Kingdom, he sought the help of Soviet Union when the United Nations refused to aid the Congolese government in “restoring law and order and calm in the interior of the country”. But he was no communist. In his own words (translated into English): In Africa, anybody who is for progress, anyone who is for the people and against the imperialists is a communist, an agent of Moscow! But anyone who approves of the imperialists, who goes out looking for money and pockets it for himself and his family, is an exemplary man; the imperialists will praise him and bless him. That is the truth, my friends.

In the book Lumumba in the arts, Matthias De Groof writes, "In Congolese society, the impression is that Lumumba is the only one who managed to hang on, to survive and to stay in people's memories through the popular and humorous speeches in which people imitate political figures, for example. When a painter portrays Lumumba, he knows that he will sell the painting, which isn't the case for other national figures." Lumumba (2000) is considered to be the first African feature film on him that portrays his life, political stance and assassination, followed by the documentary called Lumumba, la mort d'un prophète in 1990, by Raoul Peck, a Haitian director who had spent his childhood in Zaire. The father of Congolese independence has inspired a number of foreign films, among other forms of art.

To get an idea of how challenging it is to shoot a movie in the Democratic Republic of Congo at present, last week, we got in touch with Congo Rising, a US-based production company who was preparing to make a major film on Patrice Lumumba in 2021. Congo Rising's Margaret Young informed us, It’s a huge challenge! We have a call scheduled with our publicist on Thursday and a call with Roland Lumumba, Patrice Lumumba’s youngest son, on Sunday. Things are definitely NOT nailed down. The project is still alive, but there are lots of questions which must be answered.

As the Congolese people now battle the devastating consequences of the ongoing armed conflict and slavery, it is crucial that we, the common people with a conscience, do everything in our power – boycott the corporate giants getting richer by enabling modern slavery, promote the enormous creative potential of the Congolese people and amplify the unedited version of their resistance against their exploiters – to stop contributing to their sufferings.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

The franc CFA (originally denoting Colonies françaises d’Afrique) is the official currency of Senegal and most other former French colonies in Africa, from before national independence through the present-day. This monetary system and its history are the subjects of a new book by Fanny Pigeaud and Ndongo Samba Sylla, Africa’s Last Colonial Currency (2021), translated by Thomas Fazi from a 2018 French edition. The book brings to the attention of Anglophone readers the peculiar institutions through which the French Republic continues to exercise colonial rule over nominally independent African states. France’s recent “counterterrorism” operations across the Sahel region (supported and rivaled in scope by the United States’ Africa Command, AFRICOM) represent only one phase in what the Black Alliance for Peace (2020) has called France’s “active and aggressive military presence in Africa for years.” Aggression has often had monetary motivations, and control has often exceeded aggression. One of Pigeaud and Sylla’s commitments and achievements is to show how “French ‘soft’ monetary power is inseparable from its ‘hard’ military power” (2021: 99). In their telling, the CFA franc has for decades been France’s secret weapon in “Françafrique,” the zone in Africa where France, its representatives, and its monetary system have never really left. [...]

---

The franc CFA was born in Paris on the 25th of December, 1945 [...]. The embattled empire was compelled to “loosen its grip” in Africa [...]. Consequently, argue Pigeaud and Sylla, the creation of the CFA franc was “actually designed to allow France to regain control of its colonies” (13). What Minister Pleven called generosity might better be called a swindle. [...] French goods-for-export, now priced in a devalued currency (made cheaper), would find easy markets in the colonies [...]. African goods - especially important raw materials, from uranium to cocoa, priced too expensively for domestic consumption [...] -- would find buyers more exclusively in France [...]. In effect, the new CFA monetary policies re-consolidated France’s imperial economy even as the monopoly regime of the colonial pact could be formally retired in recognition of demands for change from colonial subjects. [...] [T]he egalitarian parlance of community and cooperation modernized French colonial authority, making it more invisible rather than marking its end. [...]

---

Most importantly, France has held up a guarantee of unlimited convertibility between CFA francs and French currency [...]. CFA francs can only ever be converted into France’s currency [...] before being exchanged for other currencies [...]. In 1994, in conjunction with the International Monetary Fund and against the wishes of most African leaders, French authorities adjusted the franc zone exchange rate for the first time, devaluing the CFA franc by half. This blanket devaluation was the shock through which structural adjustment was forced upon Françafrique [...]. And the devaluation proved, to Pigeaud and Sylla, that France’s “‘guarantee of unlimited convertibility’ was an intellectual and political fraud” (74). Nevertheless, French authorities have continually held up - that is, brandished and exploited - this guarantee, without honoring it. [...] Pigeaud and Sylla do not mince words: “France uses its presumed role of ‘guarantor’ as a pretext and as a tool to blackmail its former colonies in order to keep them in its orbit, both economically and politically” (38). [...] In that respect, the CFA franc system has ensured [...] the stabilization of raw material exportation and goods importation, hierarchy and indirect rule, [...] accumulation and mass impoverishment, in short, the colonial order.

---

And all along, France has found - or compelled, coerced, and more-or-less directly put in place - useful political partners in Françafrique. [...]

The CFA franc has been central to the French strategy of decolonization-in-name-only. [...]

When and where demands for self-determination and changes to the monetary system (usually more minor than exit or abolition) have been strongest, from charismatic leaders or from below, they have been met with a retaliatory response from France and its African partners, frequently going so far as “destabilisation campaigns and even assassinations and coups d’état” (40). [...]

The first case is exemplary. In 1958, Ahmed Sékou Touré helped lead Guinea to independence [...]. Guinea was alone in voting down De Gaulle’s “Community” proposal [...], and [...] the new state established its own national currency and central bank by 1960. [...] [T]he decision was ultimately made to make Guinea a cautionary tale for the rest of Françafrique. French counter-intelligence officials plotted and hired out a series of mercenary attacks (“with the aim of creating a climate of insecurity and, if possible, overthrowing Sékou Touré,” recalled one such operative), in conjunction with “Operation Persil,” a scheme to flood the Guinean economy with false Guinean bills, successfully bringing about a devastating crash (43). [...] Yet, Sékou Touré was never removed, only ostracized - unlike Sylvanus Olympio in Togo or Modiba Keita in Mali, others whose (initially minor) desired changes to the CFA status quo were refused and rebuffed and who were then deposed in French-linked coups. [...]

So too the Cameroonian economist Joseph Tchundjang Pouemi, an even more overlooked figure since his death at the age of 47 in 1984. Pouemi’s experience working at the IMF [International Monetary Fund] in the 1970s led him to recognize that the leaders of the international monetary system would “repress any government that tries to offer their country a minimum of wellbeing” (60) and could do so especially easily in Françafrique because of the CFA franc.

---

All text above by: Matt Schneider. “Africa’s Last Colonial Currency Review.” Society and Space [Book Reviews section of the online Magazine format]. 29 November 2021. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fantasy throughout the world

On top of having an article centered around the French fantasy specifically, the "Modern Success" issue of the BNF Fantasy series also has an article (again written by Anne Besson) covering the topic of "Fantasy throughout the world". Here is, once again, a rough translation by your humble servant:

While heavily dominated by an English-speaking production, fantasy literature found its place in numerous European countries, and managed to cross several continents.

Born in England, grown in parallel on the two sides of the Atlantic oceans, and becoming a mass-phenomenon in the United-States, fantasy is without a doubt an anglophone genre. Even today the fantasy market has a MASSIVE unbalance, and the modern fantasy successes prove that the mondialization of the imaginations is dominated by the cultural superpower of the USA. But ever since the 1970s, as the translations of Tolkien spread across the world and role-playing games conquered the heart of teenagers, "native fantasies" started to appear in various European languages.

German fantasy is a good example of one of those "local takes" - it does help that Germany has a literary background including the Romantic movement, and the brothers Grimm fairytales. After the enormous success of Michael Ende's Never-Ending Story in 1979, the German fantasy did not stop. Many successful authors appeared. Wolfgang Hohlbein gained an internal fame, with his 1982 Märchenmond or his 1999's Chronicles of the Immortals. Cornelia Funke was a famous German youth author, with her trilogy "Inkworld" in 2003. Kai Meyer reworked Germanic legends in his 1998's Loreley or his 2001's Nibelungengold. Walter Moers created the continent of Zamonia, and popularized the character of Captain Blue-Bear (hero of a 1993's children television show, of two novels, and of a 1999's movie).

But very often, international fame only latches on one specific author that is well-known outside of their country's frontiers. In Poland, this author would be Andrzej Sapkowski with his 1986's Witcher series, adapted in 2007 as a video game, and in 2019 as a television series). In Spain, it would be Javier Negrete with his 2003's Tramorea.

Crossing the continents, it becomes very tempting to mix together the magic of fantasy literature with specifically cultural supernatural domains - the Hindu pantheon, the Chinese ghost stories, the kami and the yokai of Japan, the witchcraft of Africa or the Caribbean Isles...

South-America is rich of a literary tradition that in France we compare to our own "fantastique": the short stories of Argentina's authors Jose Luis Borges or Adolfo Bioy Casares in the 40s, the magical realism of Alejo Carpentier in Cuba (The Century of Lights, 1962), of Gabriel Garcia Marquez in Columbia (A Hundred Years of Solitude, 1967) or Carlos Fuenta in Mexico (Terra Nostra, 1975).

On the side of the African continent, The Road of Hunger, in 1991, by Nigerian author Ben Okri, is also part of this more "legitimate" current, a form of fantasy much closer to "general literature", but there is a new African generation, dominated by English-speaking women (Nnedi Okorakor, Nisi Shaw, Lauren Beukes) that fully appropriate and absorb the fantasy genre.

Up until a very recent date, it was considered more respectful to not assimilate these works, born of very different cultures, with a genre that is both modern and Anglo-Saxon. However, the numeric world and the mondialized economy have today destroyed a lot of cultural frontiers, and today we assist to a true "meeting of the imaginations" mixing various cultures together. The author of this article mentions as an example several works coming from East-Asia: the Japanese manga Full Metal Alchemist by Arakawa Hirowu, the other Japanese manga Witch Hat Atelier, or the Sino-American movie The Great Wall (2016).

#fantasy literature#foreign fantasy#fantasy references#fantasy novels#german fantasy#non-english fantasy#polish fantasy#spanish fantasy#african fantasy#european fantasy#japanese fantasy#fantasy throughout the world

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's pretty funny how Africa Salaryman made fun of all those annoying mobile game ads that intentionally lie to potential customers. This also makes me realize that these ads are international and deceive people in all sorts of foreign markets. While I would point out the obvious solution to the puzzle, the artist took things a step further and made it so the puzzle is completely unsolvable. They put all the tropes from those ads on full display and clearly wanted to take their absurdities to the max.

While we're still talking about Africa Salaryman, I'm thinking about translating it someday. Since it's a webcomic, though, I should probably ask the original artist for permission.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some years ago, while celebrating Hanukkah at the home of Moroccan Jewish friends, I got my first taste of sfenj. I knew (and loved) the Israeli jelly donuts called sufganiyot, but sfenj, while also donuts, were something different. The yeasted dough was familiarly puffy, but instead of being shaped into a plump round, it was formed into rings. And instead of sufganiyot’s jam filling and snowy cap of powdered sugar, my friends served sfenj two ways: dipped into granulated sugar or generously drizzled with an orange-blossom-scented syrup. Naturally, I was smitten with this new-to-me expression of Hanukkah frying.

A few years after tasting sfenj, I learned about sfingi — another doughy fritter, which hails from Southern Italy and can be found in many Italian American bakeries. The term “sfingi” refers to a couple of different pastries, including simple, free-form donut holes rolled in sugar, and a more elaborate fried round that gets topped or filled with sweetened ricotta (think: cannoli filling) and sweet Amarena cherries. In Naples, the fritters are sometimes called zeppole, but in Sicily and other parts of Southern Italy, they usually go by sfingi or, to further confuse matters, sfinci.

Some Italian families make sfingi to celebrate Christmas, but they really shine on March 19th, or Saint Joseph’s Day, which honors the Virgin Mary’s husband. On that day, many Italians — particularly Sicilians who consider St. Joseph to be their patron saint — pull out all the stops to throw a feast that often ends with sfingi and other decadent sweets.

Sfenj. Sfingi. Two donuts with remarkably similar names. There had to be a connection, right? As it turns out, the North African Hanukkah treat and Southern Italy’s feast-day fritter likely do share a common ancestor. The name for both pastries comes from the Arabic word “isfenj,” which translates to“sponge,” and refers to the way dough soaks up oil while it fries, and also to its bouncy texture. (Interestingly, sufganiyot also means sponge in Hebrew, suggesting a linguistic connection between all three donuts.)

This connection also hints to the influence that Arabic cuisine had across both North Africa and Southern Italy. According to some historical accounts, sfenj originated in Moorish Spain in the Middle Ages. (The era and region similarly gave rise to the traditional Sephardic Hanukkah dish, bimuelos — small, sweet fritters that are often round in shape.) From there, the dish spread to places where Moorish traders traveled, including the Maghreb – North African countries that border the Mediterranean Sea.

Today, sfenj are popular across Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya. In Morocco, they were traditionally prepared by sufnajeen — bakers dedicated to the craft of making sfenj. They were (and are) considered an everyday breakfast pastry or street food snack, and are served alongside coffee or mint tea.

Jewish Moroccans, meanwhile, adopted the fritter for Hanukkah, when Jews traditionally eat foods fried in oil. They introduced sfenj to Israel when they immigrated there in the mid-20th century. In Israel, however, sfenj never caught on in quite the same way as sufganiyot. Moroccan Jewish families still make them, and they’re available in food markets nationwide, but you are not likely to see piles of sfenj in bakery windows across Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, they way you will sufganiyot.

Sfingi, meanwhile, hail from Palermo, Sicily’s capital. The recipe for the ricotta-cream-filled version was invented by nuns, who adapted the dessert from Arabic cuisine and dedicated it to St. Joseph. In the weeks leading up to St. Joseph’s Day, you will find sfingi di San Giuseppe – in all of its fried, cream-filled glory — in bakeries across Southern Italy, and in communities across the world that are home to Southern Italian communities.

I like to joke that the reason Hanukkah lasts for eight nights is so home cooks can dedicate each night to a different fried treat. From potato latkes and sufganiyot to bimuelos and sfenj, there is no shortage of Hanukkah dishes to celebrate. But this year, if my patience for frying (and my appetite for fried foods!) hold, I might just add sfingi to my Hanukkah menu.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jantra - Synthesized Sudan: Astro-Nubian Electronic Jaglara Dance Sounds from the Fashaga Underground

Near the border of Sudan, Eritrea, and Ethiopia, a disputed area called Fashaga is home to one of the most raucous, hypnotic, addictive, and celestial dance musics being made anywhere in Africa, perhaps the least known to the wider world of them all. Far from the townships of South Africa or the cities of Nigeria, this sound belongs to people intimately tied to their land, deep in the rural areas of Sudan. Known in some circles as “Jaglara,” this mysterious cosmic dance music is being innovated by one man, named Jantra, which translates as “craziness,” a moniker bestowed to celebrate both his personality and sound. Jantra cuts a mysterious figure, a rather unknown quantity even in Sudan, outside of the select few circles which have granted him cult status to perform at their humble gatherings or at street parties far from the gaze of the wider world. Never without his trusty blue Yamaha keyboard, Jantra joins a wave of synthesizer maestros across Africa revolutionizing the electronic sound of the continent. His dexterous fingers and street side raves in his home town of Gedarif near the Sudan-Ethiopia border caught the attention of a less privileged segment of Sudanese society who became infatuated. But you wouldn’t stumble across one of his parties unless you knew where to look, and they take place where few ever care to look. Jantra has no songs. He simply freestyles a combination of his melodies incessantly for hours on end, acting as a live producer and DJ for emphatic crowds in compact spaces, where the energy of his 155-168 BPM music is known to inspire the odd gunslinger to raise his pistol in the middle of the dance floor, ready to fire away a few shots into the air when the build up reaches climax. His Yamaha keyboard, like most keyboards, is not made in Africa and not tuned to cater to Sudanese rhythms or melodies. It required special tweaks from legendary keyboard mechanics in Omdurman market outside of the capital Khartoum who service, maintain, and jolt these synths to work for their aesthetics and flavor profile. Jantra then further tweaks the sound to achieve what you’re hearing — the perfect, sweet key tone, literally universal in its appeal. To produce this album, the Ostinato team pioneered a new approach: a hybrid reissue-contemporary album. Jantra had made a few cassette and digital recordings in his early days. We used excerpts from those and followed him to his legendary parties on the outskirts of the outskirts of the capital. Using a special technique devised by Ostinato producer Janto Koité, we extracted the individual melodic patterns, rhythms, as well as the MIDI data, and combined them with older recordings to recreate his lengthy sessions into individual dance tracks for a worldwide audience to reach the enviable frenzy of Sudanese crowds. This promising new dance music emerging from the deepest reaches of Sudan has never made its way outside of Jantra’s parties, let alone outside of the country, and never been professionally recorded. This record is confirmation that the many electronic styles being exported from Africa have a new worthy sibling and rival — Jantra’s signature electronic Jaglara from the Fashaga underground. It is a privilege of the highest order to be exposed to this unheralded, incredibly well kept rural Sudanese secret. Use unsparingly at your Synth Maestro: Ahmed Mohamed Yaqoup Eltom aka Jantra Produced & Arranged by Vik Sohonie & Janto Koité Recording & Data Extraction by Janto Koité Artwork by Mahammed El Mekki

8 notes

·

View notes