#Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

#The adventures of Huckleberry Finn 1884 by Mark Twain#James 2024 by Percival Everett#Huckleberry Finn#Jim#slavery - history - literature#love the stories around tom huck and jim since my childhood#amazing books#my art#illustration

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

The only existing footage of Mark Twain (1835-1910) filmed by Thomas Edison (1847-1931) in 1909, a year before Twain's passing.

#Mark Twain#Thomas Edison# The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876)#Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884)#writer#humorist#essayist#books#novels#literature#Father of American Literature#inventor#light bulb

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"He told the truth, mainly": what Paul Moses knew about Huckleberry Finn.

(Abridged from Wayne C. Booth's The Company We Keep: An Ethics of Fiction)

Mark Twain had himself done a lot of ethical criticism long before he published his famous warning against morality hunters at the head of Huckleberry Finn ([1884] 1982). I am thinking not mainly of essays like the devastating “James Fenimore Cooper’s Literary Offenses” but rather of the criticism implicit in his fictions… In short, Mark Twain knew well enough what it means to “find a moral” in a tale, and he knew that every tale is loaded with “morals,” even if it avoids explicit moralizing.

What he was right to fear is the destruction that can result for any story, and particularly for any comic story, when a reader busily extracts moralities rather than enjoying the tale… When he mocked courtly romances in A Connecticut Yankee (1889) and adventure tales in Tom Sawyer and parts of Huckleberry Finn, he must have known that his perceptive readers would never again enjoy those originals quite so much. And as the kind of moralist who increasingly was to lay about him with a heavy cudgel, with fewer and fewer freely comic effects, he had good reason to know that people who put their attention on finding the moral in any human story risk destroying the fun of it. Critics like me who do find a moral are going to be distracted from the sheer joy of dwelling for many hours in the mind and heart of a great natural comic poet, that “bad boy,” Huckleberry Finn.

Even so, I suspect that Twain would have been surprised, and no doubt dismayed, at the floods of moral criticism evoked by the tale. Initially the moralists’ attention seems to have been entirely on the dangers to young people of encountering the aggressive “immorality” of Huck himself—his smoking, his lying, his stealing, not to mention his irreverent “attitude.”... Twain could easily have predicted— and no doubt savored the prediction—that the portrait of an appealing youngster openly repudiating most “sivilized” norms would upset good people…

The uselessness of “conscience” is dramatized with example after example of how Huck’s conscience, actually the destructive morality implanted by a slave society, combats his native impulse to do what he really ought to do—what Twain called his “good heart.” The most famous attack on the norms dictated by obedience to public morality—and especially by official Christianity '’—comes when Huck realizes that he is committing a terrible sin in helping Jim escape slavery. Almost two-thirds of the way through the novel, long after Huck has discovered his love for Jim and has been willing to “humble myself to a nigger” and apologize for a cruel trick (709; ch. 15), Huck sits down to think by himself, after hearing some adults talking about how easy it is to pick up reward money for turning in a runaway slave. Though the pages that follow are probably more widely known than any other passage in American literature, I must trace them in some detail, because they have always provided the evidence used by us liberals in opposing Paul Moses’s kind of indictment.

[I omit that part of the discussion, as it is widely known in how the text is taught in schools]

The Indictment

If Twain could have predicted such conventional distress, he could not have predicted Paul Moses’s response, the response, as we might say, of “good old Jim’s” great-great-grandchildren reading the novel from a new perspective—not Jim’s, not Huck’s, not the white liberals’ of the 1880s or 1980s, but theirs: the perspective of a black reader in our time thinking about what that powerful novel has for a hundred years been teaching Americans about race and slavery. It would surely have shocked Twain to find that some modern black Americans see the book as reactionary in its treatment of racial questions:

For black people and for those sympathetic to their long struggle for fair treatment in North America, the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn spirals down to a dispiriting and racist close. The high adventures of the middle chapters, Huck’s admiration of Jim, Jim’s own strong selfconfidence, and the slave’s willingness to protect and guide Huck are all rendered meaningless by the closing chapters in which Twain turns Jim over to two white boys out on a lark. (Jones 1984, 34)

As a black parent... I sympathize with those who want the book banned, or at least removed from required reading lists in schools. While I am opposed to book banning, I know that my children’s education will be enhanced by not reading Huckleberry Finn. (Lester 1984, 43)

Such objections might well have seemed to Twain much more perverse than the cries of alarm from the pious. After all, the book does in fact attack the pious; they were in a sense reading it as it asked to be read—as an attack on them. But when black readers object to it, and even attempt to censor it from public schools (Hentoff 1982), are they not simply failing to see the thrust of scenes like the one I have quoted? How can they deny that Jim is “the moral center” of the work, that Twain has struck a great blow against racism and for racial equality, and that the book when read properly could never harm either blacks or whites?

So I might have argued with Paul Moses. So most white liberals today still argue when blacks attack the book. So even some black readers defend the book today. Many critics have objected, true enough, to the concluding romp that Tom Sawyer organizes in a mock attempt to free the already freed Jim. But most of the objections have been about a failure of form: Twain made an artistic mistake, after writing such a marvelous book up to that point, by falling back into the tone of Tom Sawyer. Not realizing the greatness of what he had done in the scenes on the river, he simply let the novel “spiral down,” or back, into the kind of comic stereotypes of the first few chapters. Though put as a formal objection to incoherence, this objection could be described as ethical, in the broadest sense: the implied standard is that great novels probe moral profundities; because the ending of Huck Finn is morally shallow, the book as a whole ought not be accepted as great.

Seldom is the case made that the ending is not just shallow but morally and politically offensive. Most critics have talked as if it would be absurd to raise questions about the racial values of a book in which the very moral center is a noble black man so magnanimous that he gives himself back into slavery in order to help a doctor save a white boy’s life. Why should this book, so clearly anti-racist, be subjected to the obviously partisan criticism of those who do not even take the trouble to understand what a great blow the book strikes for black liberation? Critics, black and white, are inclined to talk like this: [E]xcept for Melville’s work, Huckleberry Finn is without peers among major Euro-American novels for its explicitly anti-racist stance. Those who brand the book ‘racist’ generally do so without having considered the specific form of racial discourse to which the novel responds. (Smith 1984, 4)

In this view, all the seemingly objectionable elements, such as the use of the word “nigger,” are signs, when read properly, of Twain’s enlightened rebellion against racist language and expectations. The defense is well summarized by one black critic who seems enthusiastic about the book, Charles H. Nichols. Huck Finn, he says, is an indispensable part of the education of both black and white youth. It is indispensable because (1) it unmasks the violence, hypocrisy and pretense of nineteenth-century America; (2) it re-affirms the values of our democratic faith, our celebration of the worthiness of the individual, however poor, ignorant or despised; (3) it gives us a vision of the possibility of love and harmony in our multi-ethnic society; (4) it dramatizes the truth that justice and freedom are always in jeopardy. (Nichols 1984, 14)

Accepting the first two and the last of these, with minor qualifications, must we not question the third? Can we really accept this novel as a vision of the possibility of love and harmony in our multi-ethnic society?

It was in an effort to answer that question that I recently read the great novel again, asking what its full range of fixed norms appears to be, a century after its composition, and thus what its influence on American racial thinking is likely to be. While I found again the marvelously warm and funny novel I had always loved, I found another one alongside it, as it were. That novel looks rather different. Here is how a fully “suspicious” interpreter might view it:

“This is the story of how a pre-adolescent white boy, Huck, reared in the worst possible conditions no mother and a drunken, bigoted, cruel, and impoverished father—discovers in his own good heart and flatly against every norm of his society that he can love an older black slave, Jim—love him so strongly that he violates his own upbringing and tries to help Jim escape from slavery. Huck fails in his sporadic attempt to free Jim, but Jim is (entirely fortuitously) freed by a stroke of conscience (the same ‘good heart’?) in his owner just before she dies. (There is some problem of credibility here, since she presumably has good reason to believe, along with others in her town, that Jim earlier killed Huck Finn; but let that pass.)

“At the beginning and again at the end of the novel, Jim is portrayed as an ignorant, superstitious, boastful, kind but gullible comic ‘nigger,’ more grown child than adult. Naturally affectionate toward and uncritical of his white masters, he is almost pathetically grateful for any expression of sympathy or aid. During the central part of the novel he is turned into something of a father figure for Huck; we see him as a loving father of his own children (full of remorse about having beaten a child who turns out to be deaf); and as a deeply loyal friend (once he has found that his ‘only friend’ is the almost equally ignorant but less gullible white boy). He becomes, for large stretches, an ideally generous, spiritually sound, wonderfully undemanding surrogate parent. The implication is clear: wipe slavery away and you will find beneath its yoke a race of natural Christians: unscarred, loving, infinitely grateful people who will cooperate lovingly with their former masters (with the good ones, anyway) in trying to combat the wicked white folks, of which the world seems to be full. (There are no other black characters—just the one ‘good nigger.’) Only occasionally through these middle chapters does the author reduce Jim again to the role of stage prop. Whenever he gets in the way of the author’s plan to satirize the mores of small town and rural American society, he is simply dropped out of sight— and out of Huck’s mind: an expendable property, to be treated benevolently as part of the implied author’s claim to belong to the tiny saving remnant of human beings who escape his indictment of a vicious mankind.

“All the more curious then that we find, especially in a couple of chapters at the beginning and in a prolonged section at the end—al- most a third of the whole book—that Jim is portrayed as simply a comic butt, suitable for exploitation by cute little white boys of good heart who have been led into concocting a misguided adventure by reading silly books. There are moments in the novel when we expect that Huck Finn will discover behind the stereotype of the ‘good nigger- mistreated’ a real human being, someone whose feelings and condition matter as much as those of whites and who at the same time is not, under the skin, merely a collection of Sunday school virtues; a white prince in disguise (‘I thought he had a good heart in him and was a good man, the first time I see him. Then they all agreed that Jim had acted very well, and was deserving to have some notice took of it” [905; ch. 42]). But we lose this hope early, and we are not really surprised, only disgusted, when Huck forgets all that he might have learned and allows himself to take part in Tom’s scheme to free the already freed Jim. Huck is in one sense invulnerable to our criticism here, because he thinks that he is still ‘wickedly’ freeing a slave, his friend. But the novel, like the mischievous Tom Sawyer, simply treats Jim and his feelings here as expendable, as sub-human—a slave to the plot, as it were. We readers are expected to laugh as Tom and Huck develop baroque maneuvers that all the while keep Jim in involuntary imprisonment. Twain, the great liberator, keeps Jim enslaved as long as possible, one might say, milking every possible laugh out of a situation which now seems less frequently and less wholeheartedly funny than it once did.”

”Twain’s full indifference to what all this means to Jim, and his seeming indifference to the full meaning of slavery and emancipation, is shown in the way he exonerates Tom for his prank and compensates Jim for his prolonged suffering. I italicize (superseding Twain’s italics in this passage) the moments that now give me some trouble as I think about what the liberal Twain is up to:

We had Jim out of the chains in no time, and when Aunt Polly and Uncle Silas and Aunt Sally found out how good he helped the doctor nurse Tom, they made a heap of fuss over him, and fixed him up prime, and give him all he wanted to eat, and a good time, and nothing to do. And we had him up to the sick-room; and had a high talk; and Tom give Jim forty dollars for being prisoner for us so patient, and doing it up so good, and Jim was pleased most to death, and busted out, and says:

“Dah, now, Huck, what I tell you?—what I tell you up dah on Jackson islan’? I tole you I got a hairy breas’, en what’s de sign un it; en I tole you I ben rich wunst, en gwineter to be rich agin; en it’s come true; en heah she is! Dah, now! doan talk to me—-signs is signs, mine I tell you; en I knowed jis’ ’s well ’at I ’uz gwineter be rich agin as I’s a stannin’ heah dis minute!” (911; “Chapter the Last’’)

All nice and clear now? The happy-go-lucky ex-slave, superstitious, absurdly confused about the value of money (he happily clutches at the gift of forty dollars while Huck, by the final turn on the next page, gets six thousand), reveals himself as overjoyed with his fate, and all is well. But just what is the “vision of love and harmony” that this novel “educates” us to accept? We find in it the following fixed norms:

1. Black people, slaves and ex-slaves, are a special kind of good people—so naturally good, in their innocent simplicity, that the effects on them of slavery will not be discernible once slavery is removed. Some few whites are like that, too—the Huck Finns of the world who miraculously escape corruption by virtue of sheer natural goodness.

2. Black people are hungry for love (essentially friendless, unless whites befriend them) and they will be (should be) obsequiously grateful for whatever small favors whites grant them, in their benignity.

3. White people are of three kinds: the wicked and foolish, a majority; the foolish good— essentially generous people like the Widow Watson who are made foolish by obedience to social norms; and naturally good people, like Huck, whose only weapons against the wicked are a simulated passivity and obedience covering an occasionally successful trickery. We may find also an occasional representative of a fourth kind, the essentially decent but thoughtless trickster, the creator of stories, like Tom— and Mark Twain. They will entertain the world regardless of consequences.

4. The consequences of emancipation will be as good as they can be, in this wicked world, so long as you (the white liberal reader) have your heart in the right place—as you clearly do because you have palpitated properly to Huck’s discovery of a full sense of brotherhood with Jim. You needn’t worry about his losing that sense almost before he finds it; after all, Huck, our hero, is not responsible for anything that society might have done or might yet do about the aftermath of slavery.

5. All institutional arrangements, all government, all “‘sivilization,” all laws, are absurd—and absurdly irrelevant to what is, after all, the supreme value in life: feeling “comfortable,” as Huck so often expresses his deepest value, comfortable with “oneself,” that ultimate source of intuition which, if one is among the lucky folk, will be a sure guide.”'

6. The highest form of human comfort is found when two innocent males can shuck off all civilized restraints and responsibilities, as represented by silly women, and simply float lazily through a scene of natural beauty, catching their fish and smoking their pipes. As Arnold Rampersad says, “Much adventuring is [like this novel] written by men for the little boys supposedly resident in grown men, and to cater to their chauvinism” (1984, 49). The ideal of freedom, for both blacks and whites, is a freedom from restraint, not a freedom to exercise virtues and responsibilities— which is to say, in the words of another black critic, Julius Lester, “a mockery of freedom, a void” (1984, 46). The final addition to that blissful freedom-in-a-void is to be (or to identify with) a rebellious white child cared for and loved by the very one who might otherwise be feared, since he might be expected to act hatefully once free: the slave, toward whom the reader feels guilt. If we will just let nature take its course, those we have en- slaved will rise from their slavery to love us and carry us to the promised land.

After Such Sins, What Forgiveness?

What can we reply to such a picture? Not, I think, that it is irrelevant to our view of the book. Not that such a suspicious reader “does not know how to read genuine literature, which is not concerned with teaching lessons.” And not, surely, that the fixed norms central to the power of this book are all to the good. The events of the past hundred years have taught us—since apparently we needed the teaching—that America after Emancipation and the aborted Reconstruction just did not work that way, though white northern liberals until this last quarter of a century tended to act as if it did, or should. Nor can we take what is perhaps the most frequent tack in defending Twain: “He rose to a great moral height in the middle of the book, then simply got tired, or lost touch with his Muse, and fell back into the Tom Sawyer gambit.” That line will not work because the problems we have discovered are not confined to the gratuitous cruelty and condescension of the final “evasion.” Though they are most clearly dramatized there, they run beneath the surface of the whole book --even those wonderful moments that I have quoted of Huck’s moral battles with himself.

In the critical literature about Huck Finn, | find three main lines of defense of the book as an American classic.” In all of them, the novel is treated as a coherent fiction, not as a work that simply collapsed toward the end.

The first is the simplest: the attribution to Huck, not to Mark Twain, of all the ethical deficiencies. Since Twain is obviously a master ironist, and since we see hundreds of moments in the book when he and the reader stand back and watch Huck make mistakes, why cannot we assume that any flaw of perception or behavior we discern is part of Twain’s portrait of a “character whose moral vision, though profound, is seriously and consistently flawed” (Gabler-Hover 1987, 69)? In this view, the problems we have raised result strictly from Twain’s use of Huck’s blindnesses as “an added indictment against the society of which he [Huck] is a victim” (74; see also Smith 1984, 6, IO).

Clearly this defense will work perfectly, if we embrace it in advance of our actual experience line- by-line: dealing with any first-person narrative, we can explain away any fault, no matter how horrendous, if we assume in advance an author of unlimited wisdom, tact, and artistic skill. But such an assumption, by explaining everything, takes care of none of our more complex problems. If we do not pre-judge the case, the appeal to irony excuses only those faults that the book invites us to see through, thus joining the author in his ironic transformations. Our main problems, not just with the ending but with the most deeply embedded fixed norms of the book as a whole, remain unsolved.

George C. Carrington similarly defends the ending as of a piece with the rest of the novel, and in doing so he also defends the novel as the work of a great moral teacher who “knew what he was doing.” But he discerns not so much a great conscious ironist as an author exhibiting great intuitive wisdom, a kind of sage. The questionable norms are indeed to be found in the work, but they are fundamentally criticized by it: the views and effects I have challenged are themselves challenged by the great art of Twain, an art that in a sense goes beyond his conscious intentions. The work’s moral duplicity in fact is a brilliant portrayal of the national dilemma following the collapse of Reconstruction. Twain “could not help paralleling the national drama-sequence,” Carrington says; the story of Huck is “rather like” the story of the northern middle class, many of them former Radical Republicans who had fought to free the slaves, [who had become] irritated by the long bother of Reconstruction, became tired of southern hostility, and were easily seduced by strong-willed politicians and businessmen into abandoning the freedmen for new excitements like railroad building. . . . The spirit that led the country to accept the Compromise [of 1877, that abandoned the goals of Reconstruction] might ironically be called ‘the spirit of 77.’ Absorbed in his work and his new life in Hartford, Twain shared that spirit. He thought the Compromise a very good thing indeed... . Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is thus not only a great but a sadly typical American drama of race: not a stark tragedy of black suffering, but a complex tragicomedy of white weakness and indifference. It is one of those modern books that, as Lionel Trilling says, ‘read us,’ tell ‘us’… about ourselves. . . . The meanness of Huckleberry Finn is not that man is evil but that he is weak and doomed to remain weak. . . . Twain did not shirk the presentation, but managed to avert his gaze from the subject’s Medusa horrors by looking at it through his uncomprehending narrator. .. . By experiencing and accepting the ending we can perhaps take a step toward a similar level of self-awareness. A novel that can help its readers do that is indeed a masterwork and deserves its very high place. (1976, 190-92)

While it seems remotely possible that an author with a mind as ironically devious as Twain’s could have worked, consciously or unconsciously, to ensure that some few readers over the centuries would read the work in this special way, obviously most readers have not done so—no doubt because the book itself offers no surface clues to support such a reading. Indeed, both of these defenses spring more from the critics’ ethical programs and ingenuity than from anything that the novel proposes for itself. On the contrary, a vast majority of the artistic strokes, especially during the “evasion,” seem explicitly de- signed to heighten our comic delight in a way that would make these interpretations implausible. They both depend on the wisdom and insight of a reader who has learned to see through the “surface” of the book and recognize that it in fact mocks naive readers who laugh wholeheartedly at Tom’s pranks. They thus leave us with the question, What then happens to the great unwashed, for whom so much of the book has proved totally deceptive? Well, they are going to identify mistakenly with a deceptive implied author who has in some sense worked to take them in. Meanwhile, the real author is above all this,

creating a work that a few discerning readers can make out, after weeks, perhaps years, of careful study. In short, the defense may work well if what we are thinking of is maximum fairness to Twain, but it doesn’t work at all for the critic who cares about what a book does to or for the majority of its readers, sophisticated or unsophisticated. A third influential defense, considerably more complex, has the virtue of leaving the reader able to laugh at the troublesome ending, though embarrassed by the laughter. James Cox argues that Twain set out, through the attacks on Huck’s conscience that lead to his great moment of decision to go to hell, to enact a conversion of morality into pleasure (1966, 171-76). The form implicit in such an ethic demanded an ending that celebrates pleasure and makes everyone “comfortable,” including of course Huck and Jim. But at the moment of choice, that same form requires not the election of pleasure but of another “conscience,” the northern conscience that combats the southern conscience of Huck’s upbringing: “In the very act of choosing to go to hell he has surrendered to the notion of a principle of right and wrong. He has forsaken the world of pleasure [his own eternal salvation] to make a moral choice” (180). It is that conscience which validates, in Huck’s eyes, his going along with Tom, even though he thinks until the end that Tom, who was brought up right, is unbelievably wicked in working to free Jim.

The result is that when we exercise a “northern conscience” that confirms Huck’s choice and find ourselves laughing at the burlesque, “we are the ones who become uncomfortable. The entire burlesque ending is a revenge upon the moral sentiment which, though it shielded the humor, ultimately threatened Huck’s identity [as a natural hedonist]” (181).

If the reader sees in Tom’s performance a rather shabby and safe bit of play, he is seeing no more than the exposure of the approval with which he watched Huck operate. For if Tom is rather contemptibly setting a free slave free, what after all is the reader doing, who begins the book after the fact of the Civil War? This is the “joke” of the book—the moment when, in outrageous burlesque, it attacks the sentiment which its style has at once evoked and exploited. . . . This is the larger reality of the ending—what we may call the necessity of the form. That it was a cost which the form exacted no one would deny. But to call it a failure, a piece of moral cowardice, is to miss the true rebellion of the book, for the disturbance of the ending is nothing less than our and Mark Twain’s recognition of the full meaning of Huckleberry Finn. (175, 181)

Again we see here a critic who saves the novel by rejecting the reading that almost every white reader until recently must have given it. Each reading considers “the reader” —the “we” of these passages—to be plainly and simply the white reader, and neither one considers closely the effects on the white reader who does not feel uncomfortable with the ending. But surely the most common reading of this book, by non-professional whites, has always been the kind of enraptured, thoroughly comfortable reading that I gave it when young, the kind that sees the final episodes as a climax of good clean fun, the kind in fact that Brander Matthews gave it on first publication:

The romantic side of Tom Sawyer is shown in most delightfully humorous fashion in the account of his difficult devices to aid in the easy escape of Jim, a runaway negro. Jim is an admirably drawn character. There have been not a few fine and firm portraits of negroes in recent American fiction, of which Mr. Cable’s Bras-Coupé in the Grandissimes is perhaps the most vigorous, and Mr. Harris’s Mingo and Uncle Remus and Blue Dave are the most gentle. Jim is worthy to rank with these; and the essential simplicity and kindliness and generosity of the Southern negro have never been better shown than here by Mark Twain. . . . Of the more broadly humorous passages—and they abound— ... they are to the full as funny as in any of Mark Twain’s other books; and perhaps in no other book has the humorist shown so much artistic restraint, for there is in Huckleberry Finn no mere “comic copy,’ no straining after effect. (Matthews 1885, 154; qtd. in Blair and Hill 1962, 499-500)

If that is in fact what most white “liberals” have made of the book until recently, it dramatizes the inadequacy of the defenses we have so far considered. A book that thus feeds the stereotypes of the Brander Matthews kind of reader insults all black readers, and it redeems itself only by inciting some few sophisticated critics, many decades later, to think hard about how the story implicates white readers in unpleasant truths. That is surely not what we ordinarily mean when we call a book a classic. Even if we find a reading that at some deep level vindicates Twain for writing better than he knew, our ethical concerns remain unanswered.

Still hoping that I might someday see more merit in these defenses by others, I turn to my own efforts and find, to my considerable distress, that each of them seems almost as weak as those I have rejected. We might first use the “conversational” defense that worked for Lawrence: though Twain’s racial liberalism was inevitably limited, though he failed to imagine the “good Negro” with anything like the power of his portraits of good and bad whites, though in effect he simply wipes Jim out as a character in the final pages, he has still, by his honest effort to create the first full literary friendship between a white character and a slave, permanently opened up this very conversation we are engaged in. We would not be talking about what it might mean to cope adequately with the heritage of slavery, in literary form, had he not intervened in our conversation. There is surely something to this point, but unfortunately the argument fits Twain less well than Lawrence. Twain is not a great conversationalist, not at all “polyphonic”; rather, he is a great monologuist. We have seen here that he is not particularly good at responding to our questions: the critics I have quoted have had to do too much of the work. A great producer of confident opinions—many of them by the time he wrote already thoroughly established (for example, slavery is bad)—he never probes very deep. His positions on issues have not stimulated the kind of public debates that continue about Lawrence’s views. Instead we find collections of colorful expressions, like Your Personal Mark Twain: In Which the Great American Ventures an Opinion on Ladies, Language, Liberty, Literature, Liquor, Love, and Other Controversial Subjects (Twain 1969). Twain has opinions about many matters, but their intellectual content or moral depth would not give many TV shows serious competition. His mind takes me into no new conceptual depths; he is conventionally unconventional, so easily seduced by half-baked ideas that one would be embarrassed to offer him as a representative American intellectual.

Might I “save” him, then—or rather myself, because he is after all quite secure on his pedestal—by talking of the healing, critical power of laughter, the sheer value of comedy? Here is what I might say: “Let us celebrate Mark Twain’s preeminent comic genius, his gifted imaginings of beloved but ludicrous characters in a (quite ‘unreal,’ quite “unconvincing’) world of their own, a world in which I love to spend my days and hours and from which I emerge delighted that my world has included that kind of sheer delight. Samuel Johnson says somewhere that the sheer gift of innocent pleasure is not to be scoffed at, in a world where most pleasures are not innocent. Twain redeems my time by providing me a different ‘time’ during which my life feels quite glorious.

“It is true that in that world, in that time, there are dangerous simplifications and moments of embarrassment: it is a world inhabited only by good guys and bad guys, clever ones and stupid ones, and Twain tries to lead me too easily to think that I—one of the good and clever ones—can tell which are which. There are marvelously absurd clowns and villains, and I don’t have to reproach myself (as I do in life) for finding them clownish and villainous. I relish here good, honest, wholesome, intense sentiment; I relish an absolute sureness that everything will turn out all right and a freedom from the ‘uncomfortable’ burdens of conscience. Just think of that achievement. Twain has portrayed a world of cruelty and misery, a world of national shame, a world in which good people will in fact always be bested by the bad, and he makes us believe that everything must turn out all right! How many other novels can I think of that I can re-read again and again, teach to students and teach again, decade after decade, and still wish, after each re-reading, that they would go on longer? Huck Finn thus provides me with a kind of moral holiday even while stimulating my thought about moral issues. What a gift this is, this terribly misguided, potentially harmful work! If you try to take it away from me (you censors, black or white) I will fight you tooth and nail.

“How, then, you ask, does Huckleberry Finn differ from simple escape literature of the kind that we enjoy for an hour and then dismiss without a second thought? It does so in two ways, both of which we have hinted at already. The first is the quality of the escape: line by line, Twain simply rewards my returns with exquisite pleasures that are not so much ‘escape’ from life as the kind of thing life ought to be for. The second is a somewhat different form of our ‘conversational’ defense of Lawrence. Though Twain’s fantasy of the innocent boy discovering within his natural self the resources for overcoming society’s miseducation about ‘difference’ threatens us with the kinds of dangers I have described, it also moves us with a mythic experience that can lead to endless but fruitful inquiry into what kind of creatures we are. It is no accident that it is Huck Finn of all Twain’s works that stimulates controversy about the ethical quality of its ending and about its central situation. Somehow the fantasy/myth touches us at our most sensitive points.

In brief, long before Paul Moses and Charles Long had ever led me to think ethically about the book, it had already done its true work in this respect. The vivid images of that great-hearted black man crouched patiently in that shed, waiting while the unconsciously cruel Huck and the consciously, irresponsibly cruel adventurer Tom planned an escape that almost destroys them all— hose images haunted me even as I laughed, and they haunt me still.

“I can never know, of course, just how much miseducation the novel has provided while haunting me in this way. Who am I to say that simply thinking about the book can have removed the kinds of distortion that my black friends have pointed out. But I do believe that the mythic force of that book will be a permanent possession, a permanent gift, long after we repair black/white relations as we find them in the twentieth century. Just as Homer’s epics can now no longer harm our children in the specific way that worried Plato—shaking their confidence in the rationality and decency of the Greek gods—I suspect that Huck Finn will survive the longed-for time when racial conflict is no longer a political and moral issue in our lives.”

I seem to have grown warmer in this defense than in any of the others. But always at my back I hear the voices of those readers—including myself now—who see that the infatuation is not after all innocent. They remind me that the hours I spend in that world are after all fantasy hours; whether or not I see them as that, they have the power to deflect my imagination in dangerous ways. Jim is the “Negro” we whites might in weaker moments have hoped would emerge from slavery: docile, grateful for our gift of a freedom that nobody should ever have had the right to withhold, satisfied with a full stomach and a bit more cash than he’d had before. The picture of pre—Civil War America is a fantasy picture, in which all of the really bad occurrences are caused by caricatures of folly and evil, none of them by people who look and talk like people of our kind.” The battle in the novel for freedom from oppressive Christianity is a superficial battle, at best, and the encounter with the realities of slavery is even more superficial. The story thus offers us every invitation to miseducate ourselves, and therein lies the task of ethical criticism: to help us avoid that miseducation. The trick is always to find ways of doing that without tearing the butterfly apart in our hands.

It should be obvious that I am by no means “comfortable” (to use Huck’s word) about the incompatibilities that my project has led me to here. Having made my case against the book as honestly as possible, I now find a distressing disparity between the force of my objections (along with the relative weaknesses in the various defenses), and the strength of my continuing love for the book. My ethical criticism has disturbed a surface that once was serene. But instead of making the work and its creator look at least as great as before (Austen), or renovating a wrongly denigrated author (Lawrence), I have somewhat tarnished my hero, and since I cannot wipe from my mind the readings that black critics have imposed, I cannot, by a sheer act of will, restore Twain’s former glow. Still, though much of Huck Finn amuses me somewhat less when I read it now than it did in times irrecoverable (the recent reading was, like Cox’s, considerably more solemn than the one Twain himself obviously hoped for), the achievement still seems to me quite miraculous. On the other hand… Such a non-conclusion is disturbing to the part of me that used to seek unities and harmonies that others have overlooked, the part that once spent two years attempting to discern the form of Tristram Shandy, the part that still delights in having once “demonstrated” that Sterne actually brought that “unfinished” work to a close (1951), the part that has often earned its keep by teaching students how to see unities where others have seen only chaos. But should we not expect to discover irreducible conflicts of this kind, if each of our imaginative worlds must finally be constituted of manifold values that can never be fully realized in any one work or any one critic’s endeavor?

What is not in question is that the ethical conversation begun by Paul Moses has done its work: it has produced what I can only call a kind of conversion (both words come from the Latin convertere, “to turn or turn around”). Led by him to join in a conversation with other ethical critics, my coduction of Huckleberry Finn has been turned, once and for all, and for good or ill, from untroubled admiration to restless questioning. And it is a kind of questioning that Twain and I alone together could never have managed for ourselves.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” a novel by Mark Twain, was first published in the United Kingdom on December 10, 1884 #OnThisDay

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

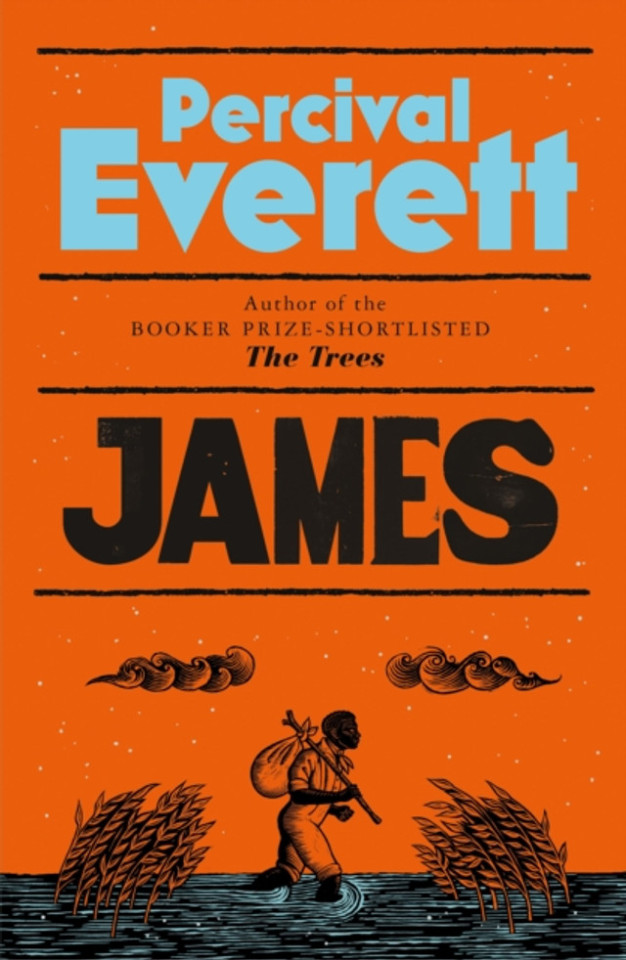

For most of his prolific, 40-year career, Percival Everett has been published by a non-profit imprint in Minneapolis, outside the traditional centre of US publishing in New York. In the UK, he was long out of print until being picked up by Influx Press, the small independent that in 2022 published his Booker-shortlisted The Trees. But after the success of that novel, major labels on both sides of the Atlantic came calling. Suddenly he’s hot property: his new book, James, arrives hard on the heels of the Oscar-winning film American Fiction, adapted from Everett’s 2001 novel Erasure, about a frustrated black novelist who decides to live down to stereotyped expectations of his work by producing a pseudonymous spoof titled My Pafology.

If you’ve read Erasure or seen American Fiction, you’ll be prepared for the central conceit of James, a reboot of Mark Twain’s 1884 novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, narrated by the enslaved Jim, one half of the book’s runaway odd couple rafting up the antebellum Mississippi. In Twain’s novel, the boy narrator, Huck, has fled home, only to encounter Jim, his guardian’s slave, also on the run because he’s about to be sold (“Ole missus... treats me pooty rough, but she awluz said she wouldn’ sell me down to Orleans”). In James, Jim’s speech, like that of every black character in the novel, is a calculated code-switching put-on: “White folks expect us to sound a certain way and it can only help if we don’t disappoint them... The better they feel, the safer we are”, or “Da mo’ betta dey feels, da mo’ safer we be”, in “the correct incorrect grammar” required by what Jim calls “situational translations”.

There’s no mistaking Everett’s glee in the steady comedy this generates throughout the book, but the language games have teeth, too, as a literal matter of life and death in a novel in which roleplay goes hand in hand with survival. Playing fast and loose with the original Twain throughout, the story unspools a series of last-gasp escapes that each usher in further jeopardy, as Jim is caught up in a money-making scam by vagrants posing as down-at-heel aristocrats or sold to a minstrel troupe, before pinning hopes of freeing his family on a hazardous disguise, only for a shipwreck to intervene.

James offers page-turning excitement but also off-kilter philosophical picaresque – Jim enters into dream dialogue with Enlightenment thinkers Voltaire and John Locke to coolly skewer their narrow view of human rights – before finally shifting gear into gun-toting revenge narrative when Jim’s view of white people as his “enemy” (not “oppressor”, which “supposes a victim”) sharpens with every atrocity witnessed en route. It’s American history as real-life dystopia, voiced by its casualties, but as you might guess from The Trees – a novel about lynching that won a prize for comic fiction – solemn it is not: “White people try to tell us that everything will be just fine when we go to heaven. My question is, Will they be there? If so, I might make other arrangements.”

The central dilemma of Twain’s novel, whose ironies have troubled readers differently down the decades, turns on Huck’s fear that it’s immoral to abet Jim’s flight, not least because Jim wants to free (or, in Huck’s word, “steal”) his family, a notion that leaves the boy aghast. Everett likewise deploys the duo’s misaligned perception for sardonic punch even as he treats their relationship tenderly. Witness the moment when Huck moots going to fight in the civil war:

“To fight in a war,” he said. “Can you imagine?” “Would that mean facing death every day and doing what other people tell you to do?” I asked. “I reckon.” “Yes, Huck, I can imagine.”

Gripping, painful, funny, horrifying, this is multi-level entertainment, a consummate performance to the last. Is there pause for thought when Jim says “white people love feeling guilty”, having told us on the first page that “it always pays to give white folks what they want”? Yes, after decades as a writer’s writer, Everett is finally hitting the big time, but somehow you doubt he’ll be giving anyone the chance to feel too cosy about that.

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at Just for Books…?

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Adventures Of Huckleberry Finn (1884)

Mark Twain

Penguin Classics

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

12. why the 1880s?

something about this decade really sings to me. I find in particular, nearing the end of the nineteenth century, so much was happening on around the world in terms of arts, politics, technology, colonization. world events and global news don’t personally reach the day-to-day lives of the everyday folk, but they are an important part in gauging what life, thought, and society was about—what things were important then and now?

basically for myself, reminding me of notable things that occured during the 1880s—some thematic, some of relevance to context and characters, and the rest just ?? interesting and/or wild?

cocaine is a hot new cure for everything and anything. perscribed, sold in foods and more. heroine introduced as a lesser-addictive substitute for morphine…

lots of developments in fields of psychology; many experiments and happenings; Freud starts his work 1886.

1880-1914 had +twenty million immigrants to the United States: Germany, Ireland, England, China had the most arrivals.

William Dorsey Swann, the first self-proclaimed drag queen, organizes a series of drag balls in Washington, D.C. 1880-1890s.

Jack the Ripper claims his “first” victim in 1888 White Chapel, London. big scare.

Sherlock Holmes first appears in Arthur Conan Doyle’s A Study In Scarlet as part of the British magazine’s Beeton’s Christmas Annual in 1887.

Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson is published in 1886. Gothic fiction, drawing from emerging fields of science and psychology. & Treasure Island was published earlier in 1883 by him too!

Mark Twain drops The Prince and the Pauper (1881), Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889).

Bel-Ami, Guy de Maupassant’s second novel is published in 1885. about a man who seduces and manipulates high society French women in the French colonies for power and wealth. MOVIE WAS ADAPTED IN 2012 STARTING ROBERT PATTINSON LOL

western European art movements very romantic and swirly and pretty: Monet, Debussy xoxo.

meanwhile, African American ragtime music becomes the “pop” music across the pond here.

North Dakota (1889), South Dakota (1889), Montana (1889), Washington (1889) become states.

train segregation laws flag beginning of Jim Crow; Civil Rights Movement of 1875 voided, making discrimination in private is not illegal, and prohibiting state intervention to personal or commercial segregation. l*nching continues throughout the south. slavery may be over on paper, but indentured labour is legal.

1882 infamous O.K Corral gunfight.

Gold Rush continues, all over the world—South Africa, to British Columbia, to California, to Argentina, to Russia-China borders.

centuries of American “Indian” wars continue.

American Dawes Act of 1887 granted American government authorization to regulate indigenous lands, including creating and assigning and enforcing reservations.

Sitting Bull’s 1883 speech of the atrocities experienced at the hands of white American settler colonists.

Canadian Pacific Railway 1881-1885. foreign labourers were hired to do a lot of heavy, dangerous, unwanted work. in America, more than 100,000km of tracks were laid by majority Chinese, Irish, Scandinavian workers.

America’s Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and Canada’s Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 was officiated, enforcing law of a Head Tax to be paid for every Chinese person entering North America. over the course of the next couple of decades, the fee of $1,500 was doubled to $5,000 was increased 500% to $25,000 in today’s currency—per person. this had devastating and lasting impacts on generations and societies of Chinese living both overseas and already in North America. propaganda at this time created many racist myths that persist today: there are too many Asians, they are taking our jobs, (the men) are gross and effeminate and a threat to (white) women, they shady and scheming people. these were the first and only major federal legislation to explicitly suspend immigration for a specific nationality in American and Canadian history. (I study Asian Canadian history, I can go on about this all day)

Tong Wars (1883-1913) had Chinatown gangs and factions in violent street wars across America, San Fransisco to New York.

large, targeted, and repeated anti-Jewish rioting (pogorm) and antisemitism rampant throughout Imperial Russia, 1881-1882 had more than two hundred anti-Jewish events alone. Jews continue to be racialized and othered.

fuck ton of colonization happening in Africa and the Middle East, Southeast Asia. Berlin conference 1884-1885 literally chopped up Africa to distribute to European powers.

Irish nationalist efforts to push forth Home Rule bill of sovereignty is defeated in British Parliament. Irish are not “white”, they are “othered” in Europe and in Americas.

use of photographic film pioneered by George Eastman, who started manufacturing film. his first camera (Kodak) was ready for sale in 1888.

Thomas Edison gets lit in New York 1883 with first electrical power station. next several year sees major cities being lit up with street lamps and public lighting with the science and works of a Nikolas Tesla (1886-1893).

hell of a lot more inventions in the works and patents being claimed. Hertz and radiowaves, Bell for telephone services.

“Between the years of 1850–1900, women were placed in mental institutions for behaving in ways the male society did not agree with”

way too much history to cram, obviously. here are some keywords for further research oki

prison industry / spiritualism / opium epidemic / irregular and uneven “modernizations” in rural vs. urban areas / class and poverty gaps / morality scares, checks, comparisons, gaps / new businesses and gadgets, products, tech to help with anything / fascination of the (colonial) Other; side shows, “freak shows” and other human zoos

#update#victorian era#1880s#1800s#1880s history#update: research#writing research#drugs cw#lynching cw#inventions#technology#gold rush#ref: poc history#ref: indigenous history#ref: black history#ref: queer history#ref: womxn history#ref: research#american history

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Holidays 12.10

Holidays

Bob Dylan Day (Minnesota)

Chief Red Cloud Day

Dewey Decimal System Day

Flag Day (Guinea)

Flipadelphia (from “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia”)

Grub-Hoe Day (French Republic)

Human Rights Day (UN)

International Animal Rights Day

International Human Rights Day (Namibia)

Jane Addams Day

Mari Alphabet Day

Merlinpeen (Festival of Mouth Pleasure from Secret Santa; Verdkianism; on “30 Rock”)

Namibian Women’s Day (Namibia)

National Cancel Caillou Day

National Corey Day

National Day of the Clown

National Derek Day

Nobeldagen (a.k.a. Alfred Nobel Day; Sweden)

Nobel Prize Day

Sister-Friend Day

Victory Day (Iraq)

Whirling Dervishes Festival begins [thru 17th]

Women’s Day (Namibia)

Women’s Rights Day (Wyoming)

World Digital Detox Day

World Football Day

World Human Rights Day (UN)

World TRAP Awareness Day

Food & Drink Celebrations

Do Something Wild and Crazy with Velveeta Day

International Tokaji Aszú Day

National Lager Day

National Pancetta Day

Suspended Coffee Day

Terra Madre Day (Slow Food)

Independence & Related Days

Constitution Day (Thailand)

Mississippi Statehood Day (#20; 1817)

Tortuga (Declared; 2021) [unrecognized]

2nd Tuesday in December

National Belgian Waffles Day (Belgium) [2nd Tuesday]

Table Tennis Tuesday [2nd Tuesday of Each Month]

Taco Tuesday [Every Tuesday]

Target Tuesday [Every Tuesday]

Tater Tot Tuesday [Every Tuesday]

Tomato Tuesday [2nd Tuesday of Each Month]

Trivia Tuesday [Every Tuesday]

Two For Tuesday [Every Tuesday]

Weekly Holidays beginning December 10 (2nd Full Week of December)

Human Rights Week (thru 12.17)

National Groundwater Awareness Week (thru 12.12)

Festivals Beginning December 10, 2024

The Bracebridge Dinner (Yosemite National Park, California) [thru 12.23]

Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable & Farm Market Expo (Grand Rapids, Michigan) [thru 12.12]

Michigan Greenhouse Growers Expo (Grand Rapids, Michigan) [thru 12.12]

Nebraska AG Expo (Lincoln, Nebraska) [thru 12.12]

Nobel Prize Award Ceremony (Stockholm, Sweden & Norway (the Nobel Peace Prize))

Stalker International Human Rights Film Festival (Moscow, Russia) [thru 12.15]

Western Alfalfa & Forage Symposium (Sparks, Nevada) [thru 12.12]

Feast Days

Adriaen van Ostade (Artology)

Behnam, Sarah, and the Forty Martyrs (Syriac Orthodox Church)

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms Day (Church of the SubGenius; Saint)

Cornelia Funke (Writerism)

Emily Dickinson (Writerism)

Eulalia of Mérida (Christian; Saint)

Festival for the Souls of Dead Whales (Inuit)

Giovanni Gioseffo dal Sole (Artology)

Greta Kempton (Artology)

Hanukkah Day #3 (Judaism) [thru Dec. 15th]

International Human Rights Day (Pastafarian)

Karl Barth (Episcopal Church USA)

Llys Don (Celtic Book of Days)

Lux Mundi (Light of the World; Roman Goddess of Liberty)

Melchiades, Pope (Christian; Saint)

Miltiades (Christian; Saint)

Purification Rites begin (Ancient Inuit; Everyday Wicca)

Rumer Godden (Writerism)

Sedna’s Day (Pagan)

Thomas Merton (Episcopal Church USA)

Tidy Up Day (Starza Pagan Book of Days)

The Toves (Muppetism)

Translation of the Holy House of Loreto (Christian)

Vieta (Positivist; Saint)

Zinaida Serebriakova (Artology)

Lucky & Unlucky Days

Fatal Day (Pagan) [24 of 24]

Tomobiki (友引 Japan) [Good luck all day, except at noon.]

Premieres

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain (Novel; 1884)

Bedazzled (Film; 1967)

Bedknob and Broomstick, by Mary Norton (Novel; 1943)

Being the Ricardos (Film; 2021)

Big Fish (Film; 2003)

The Billy Goat’s Whiskers, featuring Farmer Al Alfa (Terrytoons Cartoon; 1937)

Boris Bashes a Box or The Flat Chest (Rocky & Bullwinkle Cartoon, S5, Ep. 237; 1963)

The Cider House Rules (Film; 1999)

Counterpart (TV Series; 2017)

A Day at the Races, by Queen (Album; 1976)

Dexter’s Laboratory: Ego Trip (Hanna-Barbera Animated TV Film; 1999)

Donald’s Ostrich (Disney Cartoon; 1937)

The Ethics of Ambiguity, by Simone de Beauvoir (Philosophy Book; 1947)

The Fellowship of the Ring (Film; 2001) [Lord of the Rings #1]

Fernando, by ABBA (Song; 1975)

The Fighter (Film; 2010)

48 Hrs. (Film; 1982)

Gandhi (Film; 1982)

The Glenn Miller Story (Film; 1953)

Gopher Spinach (Fleischer/Famous Popeye Cartoon; 1954)

The Green Mile (Film; 1999)

Guided Muscle (WB LT Cartoon; 1955)

Guys and Dolls, by Damon Runyon (Short Stories; 1932)

A Horse Tale (Oswald the Lucky Rabbit Cartoon; 1928)

The Hour of the Star, by Clarice Lispector (Novel; 1977)

Islands in the Stream, by Ernest Hemingway (Novel; 1970)

The Last Detail (Film; 1973)

Lawrence of Arabia (Film; 1962)

The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (Film; 2004)

Mood Indigo, recorded by Duke Ellington and His Orchestra (Song; 1930)

A New Villain, Parts 1 & 2 (Underdog Cartoon, S3, Eps. 25 & 26; 1967)

Ocean’s Twelve (Film; 2004)

One, Two, Three, Gone! Or I’ve Got Plenty of Nothing (Rocky & Bullwinkle Cartoon, S5, Ep. 238; 1963)

Santa’s Workshop (Silly Symphony Disney Cartoon; 1932)

Shoah (Documentary Film; 2010)

The Silver Sword, by Ian Serraillier (Novel; 1956)

Sleuth (Film; 1972)

Sophie’s Choice (Film; 1982)

Swiss Family Robinson (Film; 1960)

The Tempest (Film; 2010)

Tennis Chumps (Tom & Jerry Cartoon; 1949)

Three’s a Crowd (WB MM Cartoon; 1932)

The Tourist (Film; 2010)

Toyland Premiere (Oswald the Lucky Rabbit Cartoon; 1934)

Wayne’s World 2 (Film; 1993)

West Side Story (Film; 2021)

Wings Over America (Live Album; 1976)

The Year Without a Santa Claus (Animated TV Special; 1974)

Today’s Name Days

Angelina, Bruno, Emma, Herbert (Austria)

Edmund, Gregor, Mauro (Croatia)

Julie (Czech Republic)

Judith (Denmark)

Juta, Juudit (Estonia)

Jutta (Finland)

Eulaire, Romaric (France)

Emma, Imma, Loretta (Germany)

Judit (Hungary)

Loreto (Italy)

Cera, Guna, Judīte, Sniedze (Latvia)

Eidimtas, Eularija, Ilma, Loreta (Lithuania)

Judit, Jytte (Norway)

Andrzej, Daniel, Judyta, Julia, Maria, Radzisława (Poland)

Ermoghen, Eugraf, Mina (Romania)

Radúz (Slovakia)

Eulalia, Loreto (Spain)

Malena, Malin (Sweden)

Angeline, Marian (Ukraine)

Emely, Emilee, Emilia, Emilie, Emily, Eula, Eulalia, Ula (USA)

Today is Also…

Day of Year: Day 345 of 2024; 21 days remaining in the year

ISO: Day 2 of Week 50 of 2024

Celtic Tree Calendar: Ngetal (Reed) [Day 17 of 28]

Chinese: Month 11 (Bing-Zi), Day 10 (Wu-Shen)

Chinese Year of the: Dragon 4722 (until January 29, 2025) [Wu-Chen]

Hebrew: 9 Kislev 5785

Islamic: 8 Jumada II 1446

J Cal: 15 Black; Oneday [15 of 30]

Julian: 27 November 2024

Moon: 72%: Waxing Gibbous

Positivist: 9 Bichat (13th Month) [Fermat / Wallis]

Runic Half Month: Jara (Year) [Day 4 of 15]

Season: Autumn or Fall (Day 79 of 90)

Week: 2nd Full Week of December

Zodiac: Sagittarius (Day 19 of 30)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

Mark Twain's The Adventures of Tom Sawyer was published in 1876, and narrates the life of a smart but mischievous boy Tom Sawyer living in the town of Mississippi River. This work is considered as classic American Literature and created a successful sequel The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884).

Tom's age was probably around twelve to thirten years old; as we can see in the novel, he was a jolley prankster young man. He also experienced a normal life of a lad, like making trouble with other boys and whitewashing the fench as a punishment. But later on in his life he met Huck Finn, a vagabond whose father is a drinker. One day when Tom and Huck came across with robbers, and among those robbers were Joe and Dr. Robinson, then the two men got into a fight, and Joe murdered the doctor. At a young age, these two young men were brought into contact with this kind of experience. In normal circumstances, it could be a threat to their mental development and may lead to trauma until they grow old.

Those experiences lead them to be pirates to run away from their dark past. After many events, Tom met Becky, a girl whom he had been engaged to. One day, when Tom and Becky wandered in a cave, they lost their way. At the same time, Becky suffered from a health issue. Tom tries to find a way out, and Tom successfully led Becky to safety. At the end, after these tragic experiences, they manage to live their lives as normal children and will no longer be affected by their terrible past but in an adventurous way. This novel reminds their reader about the vulnerability of a child's mind but, at the same time, the effects of being steadfast no matter our age.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bad childrearing adventures in literary comparison part two: post apocalyptic boogaloo

This week we've got Cormac Mccarthy's The Road (2006) and Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn (1884). While both are for once tied when it comes to number of murders on page, they've got one thing in common I really did not expect: neither of this men can write a child's experience of trauma to save his life. Yes, Twain does acknowledge that Finn's treatment by his father is very fucked up, making his death the happy reveal at the end of the book, but, Mark, my dude, for a book about realistic childhood experiences that sure is a lot of nothing that child feels when it comes to a lot of abuse... is what I thought, right until I reached for Cormac. Turns out, I am willing to accept a lot of narrator unreliability in the form of child's own writings and machismo within it, when the point of comparison is that goddamn disaster. Oh, yes, papa, I too am scared of travelling this post apocalyptic wasteland, but I at least have more than one emotion and two dialogue lines to express it. Sir, Dickens called and asked for his angelic children.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Holidays 12.10

Holidays

Bob Dylan Day (Minnesota)

Chief Red Cloud Day

Constitution Day (Thailand)

Dewey Decimal System Day

Flag Day (Guinea)

Flipadelphia (from “It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia”)

Grub-Hoe Day (French Republic)

International Animal Rights Day

International Aszu Day

Jane Addams Day

Merlinpeen (Festival of Mouth Pleasure from Secret Santa; Verdkianism; on “30 Rock”)

National Cancel Caillou Day

National Corey Day

National Day of the Clown

National Derek Day

Nobeldagen (a.k.a. Alfred Nobel Day; Sweden)

Nobel Prize Day

Sister-Friend Day

Victory Day (Iraq)

Whirling Dervishes Festival begins [thru 17th]

Women’s Day (Namibia)

Women’s Rights Day (Wyoming)

World Digital Detox Day

World Football Day

World Human Rights Day (UN)

World TRAP Awareness Day

Food & Drink Celebrations

Do Something Wild and Crazy with Velveeta Day

National Lager Day

National Pancetta Day

Suspended Coffee Day

Terra Madre Day (Slow Food)

2nd Sunday in December

International Children’s Day [2nd Sunday]

Jashan-e Sadeh (a.k.a. Adar-Jashen; Zoroastrian/Parsi)

Lager Beer Week begins [Sunday of 2nd full week]

National Children’s Memorial Day [2nd Sunday]

2nd Sunday in Advent [3rd Sunday before Xmas] (a.k.a. ...

Advent Sunday

Love Sunday

Transfiguration Sunday

Waiting Sunday

World Choral Day [2nd Sunday]

Worldwide Candle Lighting Day (7 PM) [2nd Sunday]

Independence Days

Mississippi Statehood Day (#20; 1817)

Tortuga (Declared; 2021) [unrecognized]

Feast Days

Adriaen van Ostade (Artology)

Behnam, Sarah, and the Forty Martyrs (Syriac Orthodox Church)

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms Day (Church of the SubGenius; Saint)

Eulalia of Mérida (Christian; Saint)

Festival for the Souls of Dead Whales (Inuit)

Greta Kempton (Artology)

Hanukkah Day #3 (Judaism) [thru Dec. 15th]

International Human Rights Day (Pastafarian)

Karl Barth (Episcopal Church USA)

Lux Mundi (Light of the World; Roman Goddess of Liberty)

Melchiades, Pope (Christian; Saint)

Miltiades (Christian; Saint)

Sedna’s Day (Pagan)

Thomas Merton (Episcopal Church USA)

The Toves (Muppetism)

Translation of the Holy House of Loreto (Christian)

Vieta (Positivist; Saint)

Zinaida Serebriakova (Artology)

Lucky & Unlucky Days

Fatal Day (Pagan) [24 of 24]

Sensho (先勝 Japan) [Good luck in the morning, bad luck in the afternoon.]

Premieres

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain (Novel; 1884)

Bedazzled (Film; 1967)

Bedknob and Broomstick, by Mary Norton (Novel; 1943)

Being the Ricardos (Film; 2021)

Big Fish (Film; 2003)

Boris Bashes a Box or The Flat Chest (Rocky & Bullwinkle Cartoon, S5, Ep. 237; 1963)

The Cider House Rules (Film; 1999)

A Day at the Races, by Queen (Album; 1976)

Donald’s Ostrich (Disney Cartoon; 1937)

The Ethics of Ambiguity, by Simone de Beauvoir (Philosophy Book; 1947)

The Fellowship of the Ring (Film; 2001) [Lord of the Rings #1]

Fernando, by ABBA (Song; 1975)

The Fighter (Film; 2010)

48 Hrs. (Film; 1982)

Gandhi (Film; 1982)

The Glenn Miller Story (Film; 1953)

The Green Mile (Film; 1999)

Guided Muscle (WB LT Cartoon; 1955)

Guys and Dolls, by Damon Runyon (Short Stories; 1932)

Islands in the Stream, by Ernest Hemingway (Novel; 1970)

The Last Detail (Film; 1973)

Lawrence of Arabia (Film; 1962)

The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (Film; 2004)

Mood Indigo, recorded by Duke Ellington and His Orchestra (Song; 1930)

Ocean’s Twelve (Film; 2004)

One, Two, Three, Gone! Or I’ve Got Plenty of Nothing (Rocky & Bullwinkle Cartoon, S5, Ep. 238; 1963)

Santa’s Workshop (Disney Cartoon; 1932)

Shoah (Documentary Film; 2010)

The Silver Sword, by Ian Serraillier (Novel; 1956)

Sleuth (Film; 1972)

Sophie’s Choice (Film; 1982)

Swiss Family Robinson (Film; 1960)

The Tempest (Film; 2010)

Three’s a Crowd (WB MM Cartoon; 1932)

The Tourist (Film; 2010)

Wayne’s World 2 (Film; 1993)

West Side Story (Film; 2021)

Wings Over America (Live Album; 1976)

The Year Without a Santa Claus (Animated TV Special; 1974)

Today’s Name Days

Angelina, Bruno, Emma, Herbert (Austria)

Edmund, Gregor, Mauro (Croatia)

Julie (Czech Republic)

Judith (Denmark)

Juta, Juudit (Estonia)

Jutta (Finland)

Eulaire, Romaric (France)

Emma, Imma, Loretta (Germany)

Judit (Hungary)

Loreto (Italy)

Cera, Guna, Judīte, Sniedze (Latvia)

Eidimtas, Eularija, Ilma, Loreta (Lithuania)

Judit, Jytte (Norway)

Andrzej, Daniel, Judyta, Julia, Maria, Radzisława (Poland)

Ermoghen, Eugraf, Mina (Romania)

Radúz (Slovakia)

Eulalia, Loreto (Spain)

Malena, Malin (Sweden)

Angeline, Marian (Ukraine)

Emely, Emilee, Emilia, Emilie, Emily, Eula, Eulalia, Ula (USA)

Today is Also…

Day of Year: Day 344 of 2024; 21 days remaining in the year

ISO: Day 7 of week 49 of 2023

Celtic Tree Calendar: Ruis (Elder) [Day 13 of 28]

Chinese: Month 10 (Gui-Hai), Day 28 (Ren-Yin)

Chinese Year of the: Rabbit 4721 (until February 10, 2024)

Hebrew: 27 Kislev 5784

Islamic: 27 Jumada I 1445

J Cal: 14 Zima; Sevenday [14 of 30]

Julian: 27 November 2023

Moon: 6%: Waning Crescent

Positivist: 8 Bichat (12th Month) [Vieta]

Runic Half Month: Is (Stasis) [Day 15 of 15]

Season: Autumn (Day 78 of 89)

Zodiac: Sagittarius (Day 19 of 30)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Favorite DISNEY STUDIOS Live Action Movies

Below is a list of my favorite live-action movies from the Walt Disney Studios. This list is in chronological order:

FAVORITE DISNEY STUDIOS LIVE ACTION MOVIES

“Treasure Island (1950) - This adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1883 adventure novel starred Robert Newton and Bobby Driscoll. Byron Haskin directed.

“Davy Crockett and the River Pirates” (1956) - Fess Parker and Buddy Ebsen starred in this prequel to the 1955 movie, “Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier”. Norman Foster directed.

“The Parent Trap (1961) - Hayley Mills starred in this first version of Disney’s film about long-lost twins who scheme to reconcile their divorced parents. Co-starring Maureen O’Hara and Brian Keith, the movie was written and directed by David Swift.

“Mary Poppins” (1964) - Oscar winner Julie Andrews and Dick Van Dyke starred in this award-winning musical adaptation of P.L. Travers series of novellas about a magical British nanny. Robert Stevenson directed.

“That Darn Cat” (1965) - Hayley Mills and Dean Jones starred in this comedic adaptation of Gordon and Mildred Gordon’s 1963 novel, “Undercover Cat”. Robert Stevenson directed.

“The Adventures of Bullwhip Griffin” (1967) - Roddy McDowall, Suzanne Pleshette and Bryan Russell starred in this adaptation of Lowell S. Hawley‘s 1963 novel, “By the Great Horn Spoon!“. James Neilson directed.

“Blackbeard’s Ghost” (1968) - Peter Ustinov, Dean Jones and Suzanne Pleshette starred in this comedy adaptation of Ben Stahl’s 1965 novel. Robert Stevenson directed.

“The Love Bug” (1968-69) - Dean Jones, Michele Lee, David Tomlinson and Buddy Hackett starred in an adaptation of “Car, Boy, Girl", Gordon Buford’s story about a magical Volkswagen. Robert Stevenson directed.

“Bedknobs and Broomsticks” (1971) - Angela Landsbury and David Tomlinson starred in this musical adaptation of Mary Norton’s children books, 1944′s “The Magic Bedknob; or, How to Become a Witch in Ten Easy Lessons” and 1947′s “Bonfires and Broomsticks”. Robert Stevenson directed.

“The Million Dollar Dixie Deliverance” (1978) - Brock Peters starred in this Civil War adventure about a black Union soldier and escaped prisoner of war, who helps five wealthy Northern children being held hostage by Confederate soldiers, escape from their captors. Russ Mayberry directed.

“Dick Tracy” (1990) - Warren Beatty directed and starred in this adaptation of the 1930s comic strip created by Chester Gould. Oscar nominee Al Pacino, Glenne Headly and Madonna co-starred.

“The Rocketeer” (1991) - Bill Campbell starred in this adaptation of the superhero comic book series created by Dave Stevens. Directed by Joe Johnston, the movie co-starred Jennifer Connelly, Timothy Dalton and Alan Arkin.

“The Adventures of Huck Finn” (1993) - Elijah Wood and Courtney B. Vance starred in this adaptation of Mark Twain’s 1884 novel, “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”. The movie was written and directed by Stephen Sommers.

“The Three Musketeers” (1993) - Kiefer Sutherland, Chris O’Donnell, Charlie Sheen and Oliver Platt starred in this loose adaptation of Alexandre Dumas père‘s 1844 novel. Stephen Herek directed.

“Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl” (2003) - Johnny Depp starred in the first film of the supernatural swashbuckler film series that was based on a Disney Park attraction. Directed by Gore Verbinski, the movie co-starred Orlando Bloom, Keira Knightley and Geoffrey Rush.

“National Treasure” (2004) - Nicholas Cage starred in the first adventure movie in this film series about a historian and treasure hunter. Directed by Jon Turtelbaub, the movie co-starred Justin Bartha, Diane Kruger, Sean Bean and Jon Voight.

“Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest” (2006) - Johnny Depp starred in the second movie of the supernatural swashbuckler film series that was based on the Disney Park attraction. Directed by Gore Verbinski, the movie co-starred Orlando Bloom, Keira Knightley and Bill Nighy.

“National Treasure 2: Book of Secrets” (2007) - Nicholas Cage starred in the second adventure movie in this film series about a historian and treasure hunter. Directed by Jon Turtelbaub, the movie co-starred Justin Bartha, Diane Kruger, Jon Voight, Ed Harris and Helen Mirren.

“Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time” (2010) - Jake Gyllenhaal, Gemma Arterton and Ben Kingsley starred in this action-adventure adaptation of Jordan Mechner’s video game series. Mike Newell directed.

“Saving Mr. Banks” (2013) - Emma Thompson and Tom Hanks starred in this biopic about conflict between author P.L. Travers and filmmaker Walt Disney over the development of the 1964 movie, “Mary Poppins”. John Lee Hancock directed.

“Tomorrowland” (2015) - George Clooney, Britt Robertson and Hugh Laurie starred in science-fiction adventure about a disillusioned scientist and a teenage science enthusiast embarking on a trip to a futuristic alternate dimension. Brad Bird directed and co-wrote with Damon Lindelof.

“Cruella” (2021) - Emma Stone starred as the titular character in this crime comedy about the villainess from Dodie Smith's 1956 novel The Hundred and One Dalmatians”. Directed by Craig Gillespie, the movie co-starred Emma Thompson, Joel Fry and Paul Walter Hauser.

Do you have any favorite Disney live-action movies? What are they?

#walt disney studios#disney studios#disney live action#disney live action films#treasure island#treasure island 1950#robert newton#bobby driscoll#robert stevenson#davy crockett#early america#davy crockett and the river pirates#fess parker#buddy ebsen#norman foster#the parent trap#the parent trap 1961#hayley mills#brian keith#maureen o'hara#david swift#mary poppins#p.l. travers#mary poppins 1964#julie andrews#dick van dyke#edwardian age#that darn cat 1965#dean jones#the adventures of bullwhip griffin

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mark Twain, 1884, “the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”, Chapter Nine

95K notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Birthday Samuel Langhorne Clemens, known by the pen name Mark Twain, (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910). He was an American writer, humorist, essayist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced,” and William Faulkner called him "the father of American literature.”

Twain's novels include The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and its sequel, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), with the latter often called the "Great American Novel."

0 notes

Text

Happy birthday to the late Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was lauded as the "greatest humorist the United States has produced," and William Faulkner called him "the father of American literature". His novels include The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and its sequel, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), the latter of which has often been called the "Great American Novel".🎂💖#LovingMemory

1 note

·

View note