#Adeliza of Louvain

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

wives of english kings who remarried after their deaths

#history#historyedit#weloveperioddrama#weloveperioddramaedit#catherine parr#katherine parr#catherine of valois#isabella of valois#isabella of angouleme#margaret of france#adeliza of louvain#emma of normandy#aethelflaed of damerham#my gifs#my gifsets

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I went down a rabbit hole after the throwaway comment about England's Queen(ish) Matilda/Maud in 'Only Murders in the Building'. You get a years-long civil war known as The Anarchy in the 12th century (Cadfael times) after Henry I died without a legitimate male heir (one legitimate daughter and 24 illegitimate kids). Henry's daughter Matilda and his nephew Stephen are fighting for the throne. I maintain this period should actually be called The Bullshit for reasons including but not limited to:

Entire crisis precipitated by putting all your eggs in one basket, or in this case aristocrats in one boat. The White Ship disaster (which is caused by the passengers getting drunk on the heir's wine and wanting to race another boat) takes out, as far as I can tell, 300 people important enough to be doing international travel in 1120, including the heir to the throne and two of his half-siblings. It's a bit of a political problem.

Stephen, incidentally, was supposed to be on the White Ship but misses it because he's got the shits.

Henry I dies FIFTEEN YEARS LATER, of an honest-to-god SURFEIT OF LAMPREYS (palfreys, according to '1066 and All That'), not having managed to produce another legitimate male child despite apparently being very worried about it and marrying a second wife for this very purpose.

Stephen and Matilda basically fight to a standstill over multiple years with the amount of ridiculous capturings-and-escapings you'd expect from a children's cartoon where nobody can die and the villain has to come back next week, and not actual for-reals warfare. The country is nonfunctional while all this shit is going on. At one point Stephen just straight-up lets Matilda go, because he's too stupid to live, apparently.

Matilda gets as far as a coronation but is chased out by a hostile crowd because god forbid women do anything. She keeps the title 'Lady of the English' which is like when you don't get any more money but your job title gets fancier.

The eventual solution, that Stephen can keep the throne but Matilda's son will inherit, absolutely stinks of everyone else being sick of their nonsense and wanting it to be over. (Stephen has a son, but he's called Eustace so he's obviously shit, but nobody knows this because CS Lewis hasn't been invented yet.)

ANYWAY! That's not the point. The point is Adeliza of Louvain, Matilda's stepmother. Henry I marries her in 1121, after his first wife dies in 1118 and his only legitimate son dies in 1120. Her one job is to produce a male heir to ward off a succession crisis. He's a 54-year-old with 24 illegitimate kids who claimed the throne after his brother had a hunting accident. She's an 18-year-old who likes French poetry. They are together for fourteen years until Henry dies of eating goddamn eels in 1135. They have zero (0) children.

Henry's bits clearly work; see above re: 24 illegitimate children. Okay he's getting on, but that's not a problem for fathers the way it is for mothers. It's not like their part of the baby-making process is difficult or time-consuming.

Maybe she's tragically infertile? LOL NOPE. Three years after Henry dies, Adeliza remarries - to William d'Aubigny, who is six years younger than her. Starting in her thirties, she has seven children with him in twelve years before fucking off to an abbey.

I can only conclude Adeliza - barely an adult, married to the king of England, given the one job of Incubator With A Pulse - spent fourteen years fighting Henry off her lady parts with a shovel. As soon as she's free to marry her toyboy, she has ALL the babies, until she loses interest and does something else instead.

I want to talk to this incredible woman. I need a ouija board and someone who can speak Medieval French.

This has been an episode of Feverish History.

#Medieval history#The Anarchy#Adeliza of Louvain#Empress Matilda#Stephen de Blois#Feverish History#It's like Drunk History but you moderate your alcohol intake and also you have Covid

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

A central element of the myth of [Eleanor of Aquitaine] is that of her exceptionalism. Historians and Eleanor biographers have tended to take literally Richard of Devizes’s conventional panegyric of her as ‘an incomparable woman’ [and] a woman out of her time. […] Amazement at Eleanor’s power and independence is born from a presentism that assumes generally that the Middle Ages were a backward age, and specifically that medieval women were all downtrodden and marginalized. Eleanor’s career can, from such a perspective, only be explained by assuming that she was an exception who rose by sheer force of personality above the restrictions placed upon twelfth-century women.

-Michael R. Evans, Inventing Eleanor: The Medieval and Post-Medieval Image of Eleanor of Aquitaine

"...The idea of Eleanor’s exceptionalism rests on an assumption that women of her age were powerless. On the contrary, in Western Europe before the twelfth century there were ‘no really effective barriers to the capacity of women to exercise power; they appear as military leaders, judges, castellans, controllers of property’. […] In an important article published in 1992, Jane Martindale sought to locate Eleanor in context, stripping away much of the conjecture that had grown up around her, and returning to primary sources, including her charters. Martindale also demonstrated how Eleanor was not out of the ordinary for a twelfth-century queen either in the extent of her power or in the criticisms levelled against her.

If we look at Eleanor’s predecessors as Anglo-Norman queens of England, we find many examples of women wielding political power. Matilda of Flanders (wife of William the Conqueror) acted as regent in Normandy during his frequent absences in England following the Conquest, and [the first wife of Henry I, Matilda of Scotland, played some role in governing England during her husband's absences], while during the civil war of Stephen’s reign Matilda of Boulogne led the fight for a time on behalf of her royal husband, who had been captured by the forces of the empress. And if we wish to seek a rebel woman, we need look no further than Juliana, illegitimate daughter of Henry I, who attempted to assassinate him with a crossbow, or Adèle of Champagne, the third wife of Louis VII, who ‘[a]t the moment when Henry II held Eleanor of Aquitaine in jail for her revolt … led a revolt with her brothers against her son, Philip II'.

Eleanor is, therefore, less the exception than the rule – albeit an extreme example of that rule. This can be illustrated by comparing her with a twelfth century woman who has attracted less literary and historical attention. Adela of Blois died in 1137, the year of Eleanor’s marriage to Louis VII. […] The chronicle and charter evidence reveals Adela to have ‘legitimately exercised the powers of comital lordship’ in the domains of Blois-Champagne, both in consort with her husband and alone during his absence on crusade and after his death. […] There was, however, nothing atypical about the nature of Adela’s power. In the words of her biographer Kimberley LoPrete, ‘while the extent of Adela’s powers and the political impact of her actions were exceptional for a woman of her day (and indeed for most men), the sources of her powers and the activities she engaged in were not fundamentally different from those of other women of lordly rank’. These words could equally apply to Eleanor; the extent of her power, as heiress to the richest lordship in France, wife of two kings and mother of two or three more, was remarkable, but the nature of her power was not exceptional. Other noble or royal women governed, arranged marriages and alliances, and were patrons of the church. Eleanor represents one end of a continuum, not an isolated outlier."

#It had to be said!#eleanor of aquitaine#historicwomendaily#angevins#my post#12th century#gender tag#adela of blois#I think Eleanor's prominent role as dowager queen during her sons' reigns may have contributed to her image of exceptionalism#Especially since she ended up overshadowing both her sons' wives (Berengaria of Navarre and Isabella of Angouleme)#But once again if we examine Eleanor in the context of her predecessors and contemporaries there was nothing exceptional about her role#Anglo-Saxon consorts before the Norman Conquest (Eadgifu; Aelfthryth; Emma of Normandy) were very prominent during their sons' reigns#Post-Norman queens were initially never kings' mothers because of the circumstances (Matilda of Flanders; Edith-Matilda; and#Matilda of Boulogne all predeceased their husbands; Adeliza of Louvain never had any royal children)#But Eleanor's mother-in-law Empress Matilda was very powerful and acted as regent of Normandy during Henry I's reign#Which was a particularly important precedent because Matilda's son - like Eleanor's sons after him - was an *adult* when he became King.#and in France Louis VII's mother Adelaide of Maurienne was certainly very powerful and prominent during Eleanor's own queenship#Eleanor's daughter Joan's mother-in-law Margaret of Navarre had also been a very powerful regent of Sicily#(etc etc)#So yeah - in itself I don't think Eleanor's central role during her own sons' reigns is particularly surprising or 'exceptional'#Its impact may have been but her role in itself was more or less the norm

389 notes

·

View notes

Text

Arundel Castle England

Arundel Castle is a restored and remodeled medieval castle in Arundel, West Sussex, England. It was established by Roger de Montgomery in the 11th century. The castle was damaged in the English Civil War and then restored in the 18th and early 19th centuries by Charles Howard, 11th Duke of Norfolk. Further restoration and embellishment was undertaken from the 1890s by Charles Alban Buckler for the 15th Duke. Since the 11th century, the castle has been the seat of the Earls of Arundel and the Dukes of Norfolk. It is a Grade I listed building.

The original structure was a motte-and-bailey castle. Roger de Montgomery was declared the first Earl of Arundel as the King granted him the property as part of a much larger package of hundreds of manors. Roger, who was a cousin of William the Conqueror, had stayed in Normandy to keep the peace there while William was away in England. He was rewarded for his loyalty with extensive lands in the Welsh Marches and across the country, together with one fifth of Sussex (Arundel Rape). He began work on Arundel Castle in around 1067.

Between 1101 and 1102 the castle was besieged by the forces of Henry I after its holder Robert of Bellême rebelled. The siege ended with the castle surrendering to the king. The castle then passed to Adeliza of Louvain (who had previously been married to Henry I) and her husband William d'Aubigny. Empress Matilda stayed in the castle, in 1139.[4] It then passed down the d'Aubigny line until the death of Hugh d'Aubigny, 5th Earl of Arundel in 1243. John Fitzalan then inherited jure matris the castle and honour of Arundel, by which, according to Henry VI's "admission" of 1433, he was later retrospectively held to have become de jure Earl of Arundel.

The FitzAlan male line ceased on the death of Henry Fitzalan, 12th Earl of Arundel, whose daughter and heiress Mary FitzAlan married Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk in 1555, to whose descendants the castle and earldom passed.

In 1643, during the First English Civil War, the castle was besieged.[ The 800 royalists inside surrendered after 18 days. Afterwards in 1653 Parliament ordered the slighting of the castle; however "weather probably destroyed more". Restructuring of the castle was carried out between 1875 and 1905. The Castle is open to the pubic

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ages of English Queens at First Marriage

I have only included women whose birth dates and dates of marriage are known within at least 1-2 years, therefore, this is not a comprehensive list. For this reason, women such as Philippa of Hainault and Anne Boleyn have been omitted.

This list is composed of Queens of England when it was a sovereign state, prior to the Acts of Union in 1707. Using the youngest possible age for each woman, the average age at first marriage was 17.

Eadgifu (Edgiva/Ediva) of Kent, third and final wife of Edward the Elder: age 17 when she married in 919 CE

Ælfthryth (Alfrida/Elfrida), second wife of Edgar the Peaceful: age 19/20 when she married in 964/965 CE

Emma of Normandy, second wife of Æthelred the Unready: age 18 when she married in 1002 CE

Ælfgifu of Northampton, first wife of Cnut the Great: age 23/24 when she married in 1013/1014 CE

Edith of Wessex, wife of Edward the Confessor: age 20 when she married in 1045 CE

Matilda of Flanders, wife of William the Conqueror: age 20/21 when she married in 1031/1032 CE

Matilda of Scotland, first wife of Henry I: age 20 when she married in 1100 CE

Adeliza of Louvain, second wife of Henry I: age 18 when she married in 1121 CE

Matilda of Boulogne, wife of Stephen: age 20 when she married in 1125 CE

Empress Matilda, wife of Henry V, HRE, and later Geoffrey V of Anjou: age 12 when she married Henry in 1114 CE

Eleanor of Aquitaine, first wife of Louis VII of France and later Henry II of England: age 15 when she married Louis in 1137 CE

Isabella of Gloucester, first wife of John Lackland: age 15/16 when she married John in 1189 CE

Isabella of Angoulême, second wife of John Lackland: between the ages of 12-14 when she married John in 1200 CE

Eleanor of Provence, wife of Henry III: age 13 when she married Henry in 1236 CE

Eleanor of Castile, first wife of Edward I: age 13 when she married Edward in 1254 CE

Margaret of France, second wife of Edward I: age 20 when she married Edward in 1299 CE

Isabella of France, wife of Edward II: age 13 when she married Edward in 1308 CE

Anne of Bohemia, first wife of Richard II: age 16 when she married Richard in 1382 CE

Isabella of Valois, second wife of Richard II: age 6 when she married Richard in 1396 CE

Joanna of Navarre, wife of John IV of Brittany, second wife of Henry IV: age 18 when she married John in 1386 CE

Catherine of Valois, wife of Henry V: age 19 when she married Henry in 1420 CE

Margaret of Anjou, wife of Henry VI: age 15 when she married Henry in 1445 CE

Elizabeth Woodville, wife of Sir John Grey and later Edward IV: age 15 when she married John in 1452 CE

Anne Neville, wife of Edward of Lancaster and later Richard III: age 14 when she married Edward in 1470 CE

Elizabeth of York, wife of Henry VII: age 20 when she married Henry in 1486 CE

Catherine of Aragon, wife of Arthur Tudor and later Henry VIII: age 15 when she married Arthur in 1501 CE

Jane Seymour, third wife of Henry VIII: age 24 when she married Henry in 1536 CE

Anne of Cleves, fourth wife of Henry VIII: age 25 when she married Henry in 1540 CE

Catherine Howard, fifth wife of Henry VIII: age 17 when she married Henry in 1540 CE

Jane Grey, wife of Guildford Dudley: age 16/17 when she married Guildford in 1553 CE

Mary I, wife of Philip II of Spain: age 38 when she married Philip in 1554 CE

Anne of Denmark, wife of James VI & I: age 15 when she married James in 1589 CE

Henrietta Maria of France, wife of Charles I: age 16 when she married Charles in 1625 CE

Catherine of Braganza, wife of Charles II: age 24 when she married Charles in 1662 CE

Anne Hyde, first wife of James II & VII: age 23 when she married James in 1660 CE

Mary of Modena, second wife of James II & VII: age 15 when she married James in 1673 CE

Mary II of England, wife of William III: age 15 when she married William in 1677 CE

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

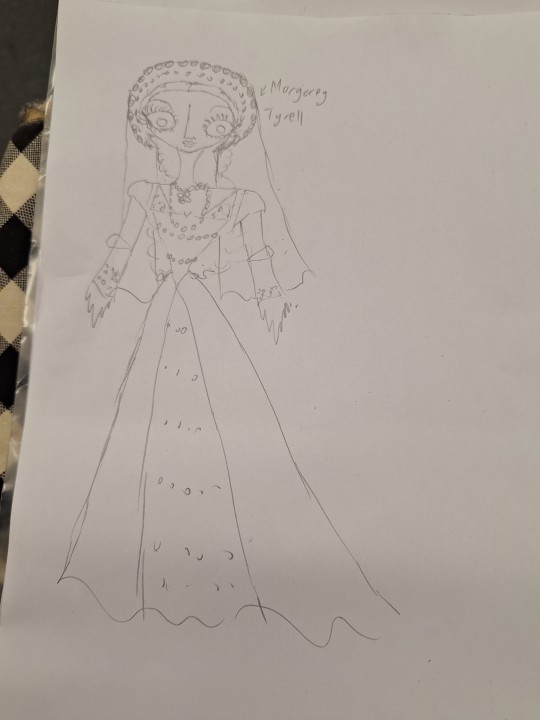

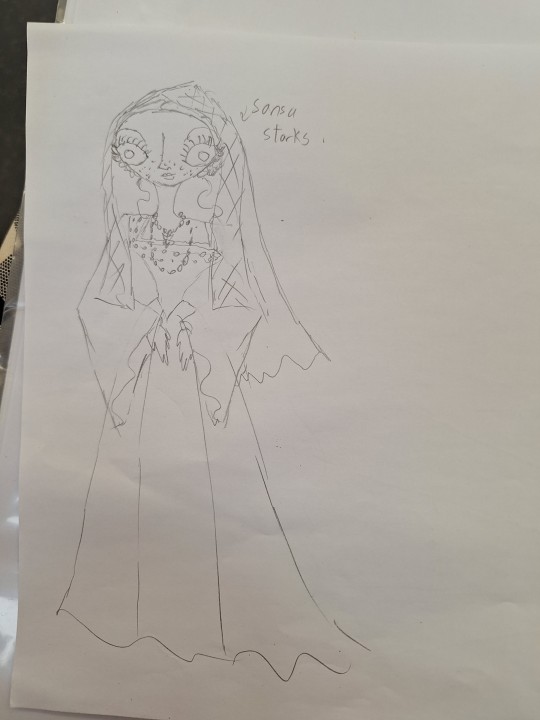

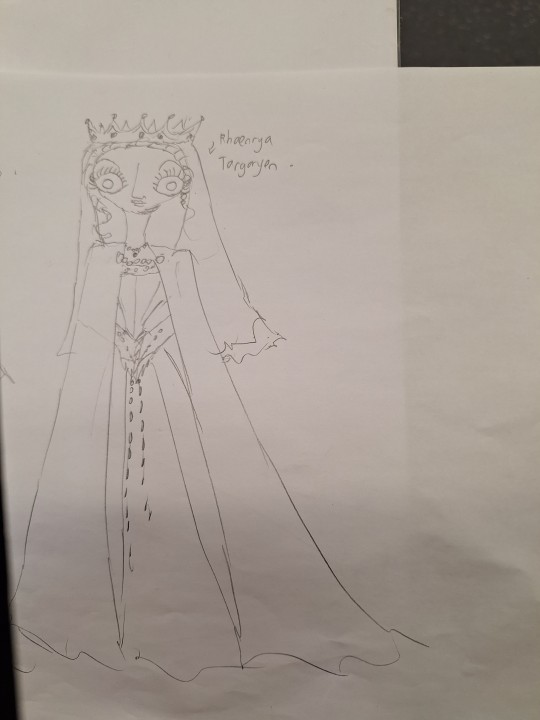

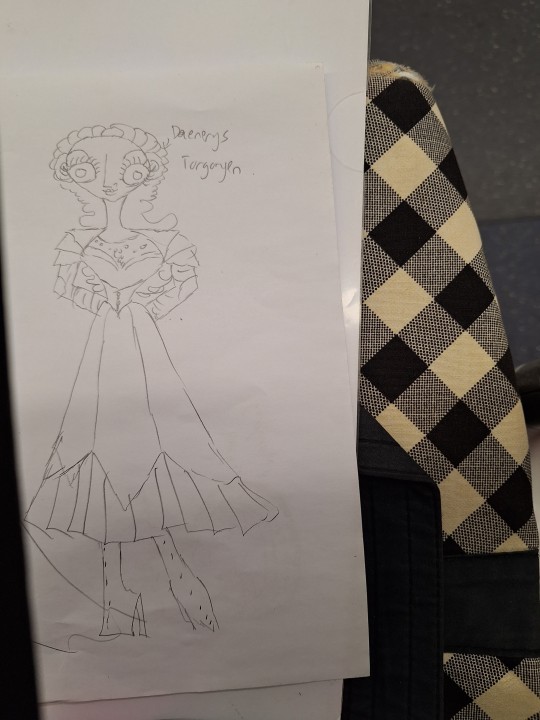

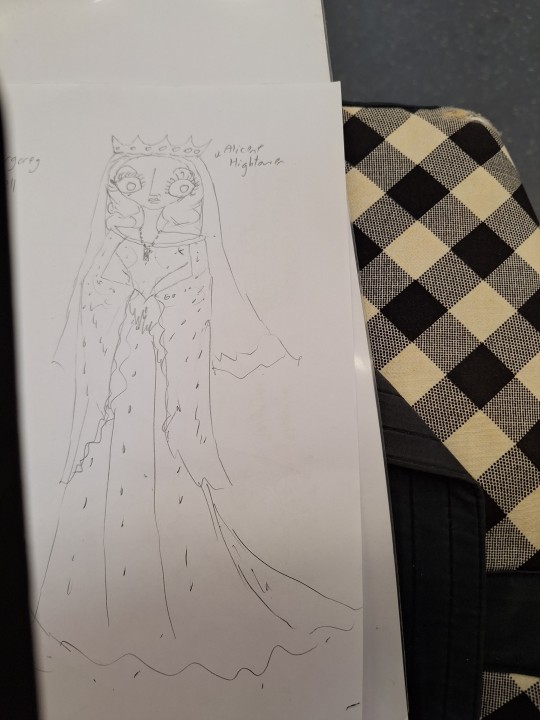

Several GOT ladies in more historically accurate clothing

Since House of the Dragon has inspirations from The Anarchy ( set in 12th century ), and Game of Thrones has inspirations from War of the Roses ( set in 15th century ), I've decided to draw several GOT franchise ladies in more historically accurate fashion

And....here we go.

A drawing I did of Margarey Tyrell in a more historically accurate attire

It is actually a Tudor Era rendition of her iconic blue and gold attire, with stylistic nods to Anne Boleyn btw

A drawing I made of Sansa Stark in a more historically accurate fashion

It is actually a 15th century rendition of a purple and gold outfit that I really like - with stylistic nods to Elizabeth of York

A drawing I did of Rhaenyra Targaryen in a more historically accurate attire

It is a 12th century rendition of a dark blue and gold dragon dress attire that she wore, with stylistic nods to Queen Leah ( Disney animated Sleepinf Beauty ) and Queen Matilda of England

A drawing of Daenerys Targaryen in a more historically accurate attire

Now Daenerys' fashions included beautiful dresses and long skirt armors

I drew Daenerys in a 15th century ladies' armor rendition of a black armor suit of hers that I really like, with stylistic nods to Joan of Arc and Lagertha

A drawing of Alicent Hightower in a more historically accurate attire

This is a 12th century rendition of Alicent's green and gold attire that I like - with stylistic nods to Queen Elinor from Brave, and Adeliza of Louvain

A drawing of Cersei Lannister in a more historically accurate attire

This is a rendition of Cersei in a 16th century rendition of a mahogany and black attire that I've seen her wear ( in my memory ) - with stylistic nods to Caterina di Medici and Mary I Tudor

#game of thrones#GOT historically accurate fashions#12th century fashions#15th century fashions#daenerys targaryen#sansa stark#margarey tyrell#cersei lannister#rhaenyra targaryen#alicent hightower#house of the dragon

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome to another installment of Scorpion Sundays! This fellow here is another Zodiac denizen, from the Shaftesbury Psalter.

The Shaftesbury Psalter, Lansdowne MS 383, is a manuscript from 12th-century England, hypothesized to have been created for Adeliza of Louvain, Queen of England and second wife of King Henry I. I would tell you more about it and see if there's anything worth checking out with the rest of the Zodiac, but the British Library's manuscript viewer is down, apparently due to cyberattack. So I guess we'll move on.

This one is clearly related to the Scorpio we saw two weeks ago (link here), who was a few decades older and found in Arundel MS 60. If you look down near the gutter of the page, you can see that this one is even also being shot with an arrow, presumably by Sagittarius again but once more I cannot confirm that due to what I must assume is some kind of ransomware scheme.

A few differences. This "scorpion" is in a slightly different pose, standing all bunched up rather than moving forwards. This artist has also directly attached the wings to the legs in a manner that seems anatomically suspect, but the connection is less smooth and stylized than the Arundel manuscript. Instead of a face like a sad bulldog, this one has a beak that makes me think of a duck; its ears are also longer and thinner. It's overall less stylized and more detailed; also, the artist is doing a black outline that's colored in rather than the red line-art of the Arundel zodiac.

Most relevant to us, this one has a distinct point at the end of its tail that I'm going to charitably consider a stinger.

This is the same basic concept overall, though, so here are the points:

Small Scuttling Beaſtie? ✘

Pincers? ✘

Exoskeleton or Shell? ✘

Visible Stinger? ✓

Limbs? 4

Also -1 for having wings, common mistake but Definitely Wrong.

Vibes are good, I like this one. The goofy duck face is charming in its way. I'm not all the way to "I want to give it a hug" like the Arundel scorpion though. I was going to give it a 4/5, but that face honestly does make me smile so let's call it a 4.5/5.

Total points:

4.9 / 10

Slightly more accurate than its relative, but also slightly less huggable.

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

Just a follow-up about Alicent Hightower within the Dance of the Dragons being inspired by the Anarchy following the death of King Henry I of England... so Alicent Hightower and Adeliza of Louvain are or aren't alike in anyway?

They're both second wives of kings who were looking for legitimate male heirs, but Adeliza didn't have any children with Henry I. Also Adeliza supported the Empress Matilda, which in this analogy would be like Alicent supporting Rhaenrya during the Dance.

So I think they're more different than similar.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Castle Rising, Norfolk

One of the largest, best preserved and most lavishly decorated keeps in England, surrounded by 20 acres of mighty earthworks.

The castle was begun in 1138 by the Norman lord William d'Albini for his new wife, Adeliza of Louvain the widow of Henry I.

In the 14th century it became the luxurious residence of Queen Isabella, widow (and alleged murderess) of Edward II.

It later became the property of Edward, the Black Prince, one of Edward III’s sons.

It is now owned and managed by Lord Howard of Rising

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Been reading up on The Anarchy as a supplement to my sporadic re-read of Fire & Blood, and IMO the parallels here are much clearer and more direct than those between ASOIAF and the War of the Roses.

(Spoilers for HotD and F&B under the cut)

Rhaenyra is pretty obviously Empress Matilda, though her ending is much sadder than her real-life counterpart's. Matilda actually outlived the relative who usurped her throne, and saw her son ascend as Henry II of England.

Henry I is King Viserys, who appointed his daughter as his heir. Matilda's cousin Stephen of Blois usurped her throne and is the clear parallel to Aegon the Elder.

As far as I can tell, William of Ypres is the real-life inspiration for Criston Cole as Stephen's military leader, Waleran de Beaumont is the inspiration for Otto Hightower as the treacherous, grasping noble who became Stephen's main advisor, and Stephen's brother Henry of Winchester is the inspiration for Aemond. Matilda's first husband is likely the inspiration for Laenor.

Daemon and Alicent are more complicated, as I believe they are based on several prominent historical figures of the time.

For Daemon, he appears to be inspired by both Geoffrey of Anjou, Matilda's second husband and Henry II's father, and Matilda's uncle, David I of Scotland (who also somewhat inspired Lord Corlys). Both were supporters of her claim, along with her half brother Robert of Gloucester, who seems to be the inspiration for Rhaenys (though his claim was denied in favor of Henry I because he was a bastard, as opposed to Rhaenys whose claim was denied because she was a woman). Like Daemon, Geoffrey died toward the end of the war.

Alicent's inspiration is complicated in a different way. She seems to have been inspired by two very opposing figures in history, two women who shared the same name.

The first is Adela (or Adeliza) of Louvain, Henry I's second wife and Matilda's stepmother. Adela of Louvain married Henry I after his first wife, Matilda's mother, died. She was only 18, and Henry was over 30 years her senior. She was actually one year younger than Matilda herself.

Adela actually supported Matilda's claim and even defied her second husband to do so. Though she apparently betrayed Matilda later (probably out of fear) when Stephen besieged her castle, she also bargained with him to secure Matilda's safe departure. Ultimately, it's easy to imagine her as the inspiration for the show's framing of Alicent and Rhaenyra as close friends.

The other likely inspiration for Alicent is Adela of Normandy, Stephen the usurper's mother. She supported her son's siezure of the throne. She was known to be extremely pious, echoing the way Alicent clings to the Faith of the Seven. She was actually made a saint after her death. Her husband, Count Stephen II of Blois, may have been the inspiration for some of Viserys's characterization as well.

Matilda and Geoffrey's son, Henry II, is of course the inspiration for Aegon III.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

This bit of Medieval history from England will sound somewhat familiar.

Henry I sired two dozen or more children out of wedlock. But with his queen, Matilda, he had only a daughter, the future “Empress” Matilda, and a son, William. With William’s birth, the foremost responsibility of medieval queenship was fulfilled: There would be a male heir. Then tragedy struck. In 1120, a drunken 17-year-old William attempted a nighttime crossing of the English Channel. When his also-inebriated helmsmen hit a rock, the prince drowned.

Kids, don't go sailing when drunk. An accident could lead to a war of succession.

The queen had died two years earlier, so Henry remarried. But he and his second wife, Adeliza of Louvain, had no children together. The cradle sat empty, and the sands in Henry’s hourglass ran low, so he resolved that his lone legitimate child, Matilda, would take the throne as a ruling queen. The move was unprecedented in medieval England. A queen could exert influence in her husband’s physical absence or when, after a king’s death, their son was a minor. Her role, moreover, as an intimate confidant and counselor could be consequential.

A quick reminder that this was 400+ years before Mary I – England's first female reigning monarch. They were still speaking Middle English in the early 12th century.

But a queen was not expected to swing a sword or lead troops into battle and forge the personal loyalties on which kingship rested, to say nothing of the misogyny inherent in medieval English society. The queen was the conduit through which power was transferred by marriage and childbirth, not its exclusive wielder. [ ... ] Henry I pursued measures to make his daughter palatable to them. Matilda, who had married the Holy Roman Emperor Henry V in 1114, returned to England a widow in 1125. Henry I, determined to forge a sacramental bond between his daughter and England’s magnates, compelled his barons in 1127 to swear their support for her as his successor. Henry I then turned to arranging a marriage for Matilda so she could give birth to a grandson and buttress her position.

After Matilda’s nuptials with Geoffrey, Count of Anjou, the barons were summoned to renew their oath to her in 1131. A son, Henry, was born two years later, and a third pledge followed. Henry I died two years later of food poisoning after eating eels, a favorite dish of his.

Of course, all hell breaks loose after the king dies.

Stephen of Blois, a son from the marriage of Henry I’s sister Adela to a French count, aggressively registered a claim to the crown after Henry I’s death. Many English magnates conveniently forgot their oaths to Matilda, and Stephen became king. Matilda was not without supporters: her half-brother Robert, Earl of Gloucester; her husband, the Count of Anjou; nobles disaffected by Stephen’s rule; and opportunists seeking personal gain from the conflict. Matilda resisted, and the Anarchy ensued. Forces supporting Matilda invaded England in 1139, but save for a moment in 1141, she never ruled. She then focused instead on elevating her son to the crown.

Military success speaks louder than oaths or pledges.

Prosecution of the war ultimately passed to the young Henry. His mounting military successes jogged the barons’ memory of their past commitments, and the contending parties reached a settlement. Henry would succeed Stephen. With Stephen’s death, Henry became Henry II.

It isn't exactly like the Targaryen civil war but the themes are similar.

Matilda, daughter of Henry I and mother of Henry II.

#game of thrones#house of the dragon#rhaenyra targaryen#the anarchy#matilda – lady of the english#henry i#gra o tron#ród smoka#la maison du dragon#дім дракона#آل التنين#juego de tronos#jogo dos tronos#a casa do dragão#la casa del dragón#龙之家族#ejderha evi#ड्रैगन का घर#하우스 오브 드래곤#בית הדרקון#হাউস অফ দ্য ড্রাগন#rod draka#lohikäärmeen talo#gia tộc rồng#ڈریگن ہاؤس#sárkányok háza#σπίτι του δράκου#дом дракона#haus des drachen#кућа змаја

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Honestly, in my opinion there isn’t really a good in-universe explanation for Viserys choosing to marry again - because the *actual* reason for his actions is “GRRM wrote him that way in order to advance the narrative, despite the fact that it makes very little sense for the character to act like that.” You can really see this when you compare the Dance of the Dragons to its IRL historical inspiration (the Anarchy/first English civil war), since the initial set up is pretty much a 1:1 copy of IRL history.

Basically, Viserys’ counterpart Henry I had a daughter (Matilda) and a son with his first wife, the son died so Henry married again (to the much younger Adeliza of Louvain - similar to Alicent & Rhaenyra in HOTD, she was pretty much the same age as Matilda) in the hopes that he could have another male heir. However, he was aware that the succession was dicey while he was still trying to beget another son, so he chose Matilda as his heir and had the barons swear to recognise her as such in 1126, on the condition that he died with no legitimate sons. You can probably guess what happened next - he did in fact die with no legitimate sons in 1135, and his nephew Stephen seized the crown instead.

This is the big difference from F&B/HOTD - IRL Henry was working within the established patriarchal power systems, so if he’d had a son with Adeliza, they would’ve automatically superseded Matilda’s claim to the throne, while Viserys keeps Rhaenyra as heir even though in-universe it makes 0 political sense and in fact undermines his own initial claim to the throne (which was based on male primogeniture negating Rhaenys’ claim).

IMO the reason why GRRM diverged from history here is because there’s much more drama and narrative tension in pitting (half-)sister vs (half-)brother rather than cousin vs cousin. Also he likely wanted Rhaenyra and Alicent, the two major female players on either side of the civil war, to be narrative foils for each other in a way that Matilda and Adeliza weren’t IRL (though personally I would argue that Matilda and Adeliza’s relationship was actually much more interesting than the stereotypical “evil usurper stepmother” narrative in F&B! I can definitely talk more about them if anyone’s interested - I can talk sooooo much about them - but this reply is already pretty long and I haven’t even scratched the surface of the IRL political situation, precedent etc. so I will wrap it up here haha)

TL;DR Viserys remarries because GRRM is cribbing from IRL history, however the changes he’s made to the story in service of narrative drama means that the characters’ decisions don’t actually make sense in context and just makes them look... kind of politically stupid 😭 (see also: Rhaenyra’s actions in F&B vs what Matilda actually did IRL. And don’t get me started on how Daemon, although vaguely similar to Robert of Gloucester, takes on a much more prominent role at Rhaenyra’s expense because he’s clearly GRRM’s pet fave!!)

Asking someone to explain to me the reason why Viserys chose to marry again knowing he'll name Rhaenyra his heir. Like genuinely, explain it to me like you would to a toddler.

°

Because I'm not buying the whole peer pressure bs explanation when clearly he could hold his own ground when it came to making decisions — when he named Rhaenyra heir he didn't let anyone change his mind. So I don't for a second believe that "poor little Viserys" got bullied into a second marriage.

587 notes

·

View notes

Photo

— House of Normandy: QUEENS ♕

#historyedit#matilda of flanders#matilda of scotland#adeliza of louvain#matilda of boulogne#empress matilda#empress maud#history#perioddramaedit#periodedits#gifshistorical#onlyperioddramas#perioddramasource#women in history#english history#fancast#userperioddrama#userbennet#duchessofhastings#my edit

381 notes

·

View notes

Note

Why was empress Mathilda not able to become the ruler?

Hi! There were lots of reasons, and historians have gone back and forth between them over the years. I am not an expert at all, but the way I see it, it was a combination of factors - be it social, structural, or plain bad luck - that resulted in Matilda's inability to claim the throne of England. To list a few I think were relevant:

Misogyny. After his son's death in 1120, Henry I's first instinct doesn't seem to have been to name his daughter his heir but instead to conceive another son with his second wife Adeliza of Louvain. William of Malmesbury wrote that the lords swore to accept Matilda as their sovereign only if Henry I died without a male heir; John of Worcester wrote that Henry designated Matilda as heir as "he had as yet no legitimate heir to the kingdom", implying that Matilda would be the one to provide that heir (ie: a son); and it seems that some of Matilda's supporters like Robert of Gloucester stressed the claims of infant Henry (the future Henry II) from the onset. Some historians have argued that Henry I wished to live long enough to transfer the kingdom and duchy to his eldest grandson, though this is of course mere speculation and Matilda would have been her father's immediate successor for the foreseeable future regardless. So even during Henry I's life, while Matilda was named heir and was expected to inherit & rule England, her exact situation appears to have been complex, and her gender was - directly or indirectly - at the heart of the complication.

Moreover, during the Anarchy, while Stephen technically did not justify or defend his claim to the throne explicitly because of his gender, there was clearly public debate over female succession at that time: for example, Matilda's illegitimate brother Robert of Gloucester was known to reference the Bible, where the Book of Numbers depicted God sanctioning female inheritance when there were no sons. This indicates that Matilda faced opposition from enemy quarters specifically for those reasons. Also, during Matilda's brief assumption of power as a female king, gendered ideals of masculinity/femininity and kingship/queenship entirely dictated public response to her and shaped her negative reputation.

Xenophobia. The Normans and Angevins were historic enemies, and many nobles were incredibly worried about Matilda’s second husband Geoffrey Plantagenet becoming king. I don't think it's a surprise that the Gesta Stephani repeatedly called Matilda "Countess of Anjou" or emphasized the presence of "Angevin knights" among her entourage. This had something to do with gendered expectations as well, but it was also likely meant to highlight Matilda's presumed foreignness, despite the fact that she was a princess of England by birth.

Complicated inheritance patterns. Succession in England, both before and after the Norman Conquest, was incredibly tricky. I'm not even going to get started on the Anglo-Saxons, but going by William the Conqueror's children: his eldest son rebelled against him, his second son inherited while keeping the eldest one imprisoned for life, and was in turn most likely murdered by the third son, who also kept the eldest son imprisoned for life. Hereditary claims were thus overridden in both cases. As Charles Beem points out in the Lioness Roared about Matilda's own father: "Henry I promoted a system of lineal inheritance based on a firm rule of primogeniture [for his children]. However, his own legitimacy as king was not based on this principle, a concept that infiltrated Anglo-Norman inheritance practices during his reign. Instead, he based his self-representation as a legitimate king on a medieval hodge-podge of justifications: porphyrogeniture, or having been “born to the purple” after his father had become king of England, sacralization from his anointing and consecration, and the acclamation of the people: Finally, Henry I secured papal recognition for his title, and convinced Pope Calixtus II to reject the claims of William Clito, the son of Henry’s eldest brother Robert Curthose, in effect dealing a severe blow to the legitimacy of primogeniture." So even in an ideal scenario, the idea of a designated heir and eldest child succeeding without hindrance would have been unusual. Unfortunately, this was not an ideal scenario by any circumstances.

Also, England seems to have functioned with an interregnum at that time, meaning that Matilda would not have been immediately considered ruler upon her father's death. To quote Beem: "To become king of England in the year 1135 required positive, immediate action; although the theory of the king’s two bodies had already begun to develop, the idea that an immediate succession occurred upon the death of a king had not. Instead, an interregnum occurred, which ended only when the crown was placed on the next king’s head. This had been the case with William Rufus’s accession in 1087 and that of Henry I in 1100, both of whom overrode the hereditary claims of William the Conqueror’s eldest son Robert Curthose. Although Matilda had received oaths to support her candidacy, the oaths in themselves did not make her king. Like her uncle and her father before her, Matilda needed to be physically present in London, to receive formal homage from her tenants-in-chief, to accept the acclamation of the people, and to be anointed and crowned in Westminster by the archbishop of Canterbury". I think the first heir to be regarded as king despite not being physically present in the country was Edward I in 1272 - a while away. Which brings me to...

Bad Luck. At the time of her father's death, Matilda wasn't in England or Normandy. She seems to have left her father's court after a disagreement where he refused to be reconciled with William Talvas without punishing him despite Matilda's wishes on the contrary. As Robert of Torigny notes, in the end of 1135, "the empress Matilda, who he [Henry I] had long before appointed heir to his realm, was staying in Anjou with her husband count Geoffrey and her sons"; William of Malmesbury likewise stated that she was staying in France “for certain reasons.” The fact that Matilda wasn't physcally present made it easy for Stephen and the nobles to sideline her and overrule Henry I's appointment.

Matilda was also pregnant at the time, and it's possible that this prevented her for making the crossing, either due to physical reasons (we know she nearly died during her second childbirth) or due to ideological ones (she may have "considered such a state to be a liability in constructing herself as a viable contender for an office essentially gendered male", as Beem speculates).

An insufficient power base: Yet another one of her misfortunes was the fact that Henry I seems to have withheld his daughter's dowry till the end of his life. For example, Torigny writes that "the king was unwilling to do the fealty required by his daughter and her husband for all castles in Normandy and in England". Nor does Henry seem to have associated her with direct kingly governance during his life that could have made the transition to rulership more natural for her and for English & Norman magnates. This meant that Matilda and Geoffrey didn't seem to have had a solid power base to rely on at the time of her father's death with which she could directly launch her claim. It's no surprise that their first move was to try and secure her dowry castles (Exmes, Domfront, Argentan, Ambrières, Gorron, Colmont, etc), and that Matilda installed herself in one of them.

And, of course, Matilda's ultimate bad luck was the existence of a rival claimant (Stephen) with sufficient resources and backing who chose to press his own - theoretically inferior - claim. Ultimately, after the majority of nobles sided with or acquiesced to Stephen, Matilda's doors were shut - without tangible support, she was stuck. It's not surprising that it was only after Stephen began to alienate his followers (particularly Robert of Gloucester, who had initially supported him) a few years later that Matilda got an opportunity to press home her advantage.

Hope this helps!

#obligatory disclaimer that I'm not an expert at this and may have fumbled in a few places (I don't think so but just in case)#empress matilda#12th century#english history#the anarchy#my post#queue#I'll edit this some more in a bit (maybe)#ask

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

CONSORTS OF ENGLAND SINCE THE NORMAN INVASION (1/5) ♚

Matilda of Flanders (December 1066 - November 1083)

Matilda of Scotland (November 1100 - May 1118)

Adeliza of Louvain (January 1121 - December 1135)

Geoffrey V of Angou (April 1141 - 1148)

Matilda of Boulogne (December 1135 - May 1152)

Eleanor of Aquitaine (December 1154 - July 1189)

Margaret of France (1170 - June 1183)

Berengaria of Navarre (May 1191 - April 1199)

Isabella of Angoulême (August 1200 - October 1216)

Eleanor of Provence (January 1236 - November 1272)

#my photoset.#royal edit#history#historyedit#matilda of scotland#matilda of flanders#adeliza of louvain#geoffrey v#eleanor of aquitaine#margaret of france#berengaria of navarre#isabella of angouleme#eleanor of provence#british royal family#british royals#royals#royal#queens#historical royals#medieval ages#british royalty#historical royalty#consorts of england since norman invasion#english history#plantagenets#house of normandy#house of blois#plantagenet dynasty#consorts of england since norman invasion edit#consorts of england and britiain.

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Queens of England (2/7)

Queen consorts and queen regnants of England from 856 to present day

#aelfgifu of york#emma of normandy#ealdgyth#edith of wessex#matilda of flanders#matilda of scotland#adeliza of louvain#empress matilda#historical women#gif#gifset#british history

93 notes

·

View notes