#Aboriginal history

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

How do Canadian schools teach about indigenous Canadian history and culture? -a curious USAmerican

In my experience we learned about colonization at the same time as we learned about the formation of Canada. At first it was "European settlers came and pushed out the indigenous population", then in the higher grades we learned more about the how and the why.

For example, how carts full of men with rifles would ride around shooting Buffalo, then leaving the meat on the ground to rot, because "a dead Buffalo is a dead indian", which was so fanatical it almost wiped out wild Buffalo entirely

Also how Canadian settlers were lured in with beautiful hand-painted advertisements for cheap, beautiful, fertile land that was unpopulated and perfect, if only you'd sail over with your entire family and a pocket full of seeds- only to be met with scared, confused, and angry lawful inhabitants already run out of ten other places, and frigid winters, and rocky, forested, undeveloped dirt.

also, smallpox blankets, where "gifts" of blankets infected with smallpox were intentionally given out

And treaty violations- Either ignoring written agreements entirely, or buying them out at insanely low prices and lying about the value, or trading for farming equipment that they couldn't use because they weren't farmers.

Then in the first world war, where they told indigenous peoples here that they'd be granted Canadian citizenship if they enlisted

To Residential schools, which was straight up stealing kids for slavery, indoctrination, and medical experiments

But we also covered the building of the Canadian Railway in which Chinese immigrants were lowered into ravines with dynamite to blow out paths through the mountain for pennies on the dollar

And the Alberta Sterilization Act, where it was lawful and routine procedure to sterilize women of colour and neurodivergent people without their awareness or consent after giving birth or undergoing unrelated surgeries

But I'm rambling.

We kind of learned Aboriginal history at the same time as everything else? Like. This is when Canada was made, and this is how it was done. Now we'll read a book about someone who lived through it, and we'll write a book report. And now a documentary, and now a paper about the documentary. Onto the next unit.

And starting I think in grade 10 our English track was split between English and Aboriginals English, where you could choose to do the standard curriculum or do the same basic knowledge stuff with a focus on Aboriginal perspectives and literature. (I did that one, we read Three Day's Road and Diary Of A Part-Time Indian, and a few other titles I don't remember.)

There was also a lunch room for the Aboriginal Culture Studies where Aboriginal kids could hang out at lunch time if they wanted, full of art and projects and stuff. They'd play music or videos sometimes, that was cool

And one elective I took (not mandatory cirriculum) was a Kwakiutl course for basic Kwakwakaʼwakw language. Greetings, counting to a hundred, learning the modified alphabet, animals, etc. Still comes in handy sometimes at large gatherings cause they usually start with a land recognition thanking whoever's land we're on, with a few thanks and welcomes in their language.

And like- when I was in the US it was so weird, cause here we have Totem poles and longhouses and murals all over and yall... don't? Like there is a very distinct lack of Aboriginal art in your public spaces, at least in the areas I've been

My ex-stepfather, who was American, brought his son out once, and he was so excited to "see real indians" and was legitimately shocked to learn that there weren't many teepees to be found on the northwest coast, and was even *more* shocked when we told him that you have Aboriginal people back home too, bud. Your Aboriginal people are also named "Mike" snd "Vicky" and work as assistant manager at best buy.

If you'd ask me, I'd say that the primary difference is that USAmerica (from what I've seen, and ALSO in entirely too much of Canada) treats our European and Aboriginal conflicts as history, something that's tragic but over, like the extinction of the mammoths, instead of like. An ongoing thing involving people who are alive and numerous and right fucking here

But at the end of the day, I'm white, and there are plenty of actual Aboriginal people who are speaking out and saying much more meaningful things than I can

So I'm just gonna pass on a quote from my Stepmum, who's Cree, that's stuck with me since she said it:

"You see how they treat Mexicans in America? That's how they treat us here. Indians are the Mexicans of Canada."

#Canadian history#Canadian education#Medical tw#Medical malpractice#Human rights#Genocide tw#Residential school tw#Child abuse tw#Slavery tw#Current events#Canadian Education#Aboriginal history

566 notes

·

View notes

Text

Condoman

In 1987, Indigenous sexual health worker Aunty Gracelyn Smallwood and her team felt that safe sex advertising wasn’t effectively targeting people in Australia’s remote Indigenous communities. In response, they created Condoman - “The Deadly Predator of Sexual Health” - who spoke to Indigenous people in language they could relate to, and removed stigma from conversations about sexual health.

Condoman became something of a cult figure in Australia, and in 2009 he was relaunched with a suite of comics, animations, and merch, including branded condoms. He was also joined by his “deadly, slippery sister” Lubelicious, who promoted consent, the use of water based lube, and women’s health, for her sisters and sistergirls (an Indigenous term analogous to trans women).

We covered Condoman in our podcast on the AIDS epidemic in Australia.

Keep an eye on this blog throughout the week as we continue highlighting queer Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander history and culture for NAIDOC Week.

#naidoc2024#naidoc week#aids#hiv#condoman#queer history#gay history#lgbt history#queer#gay#lgbt#lgbtq#indigenous history#aboriginal history

460 notes

·

View notes

Photo

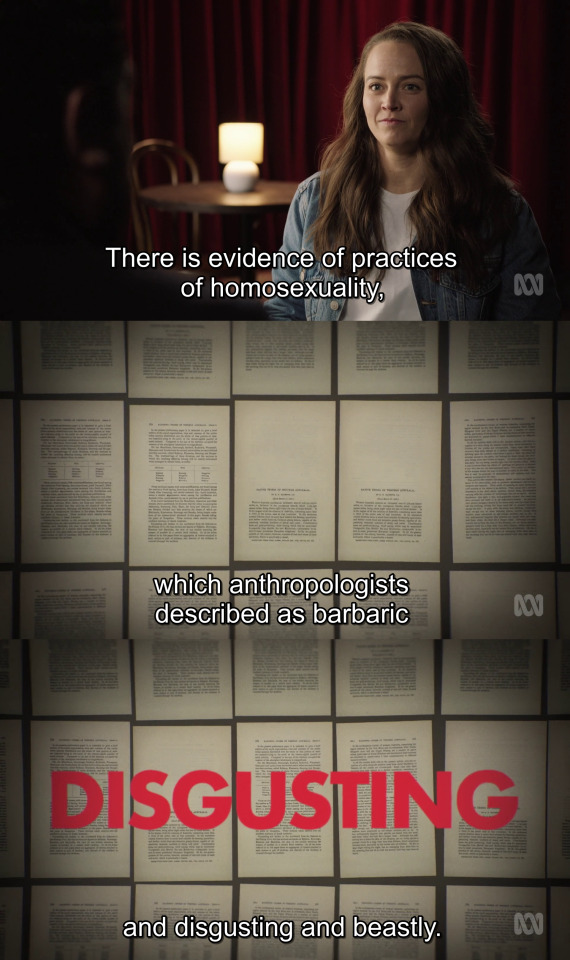

QUEERSTRALIA (2022) Episode 1 dir. Stamatia Maroupas

#queerstralia#documentaryedit#todd fernando#zoe coombs marr#lgbtqai#aboriginal#history#colonisation#aboriginal history#australian history#queer history#lgbt history#australian queer history#racism tw#homophobia tw

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

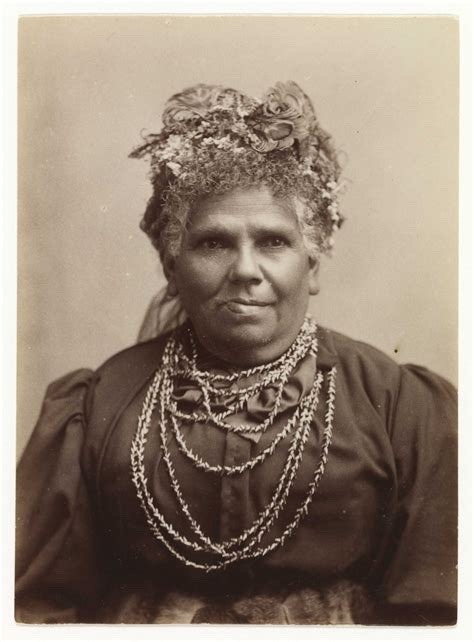

Warning to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People: the following post may contain photos of people who have passed away

Source: Bold: Stories from older lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender & intersex people by David Hardy

#Aboriginal history#Australian Aboriginal history#lesbian history#lesbian positivity#Aboriginal lesbian history#Aboriginal lesbian positivity#lgbt history#Australian lgbt history#tw racsim#tw homophobia#lgbt#lesbian#image#photo#personal

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"If we look at the evidence presented to us by the explorers, and explain to our children that Aboriginal people did build houses, did build dams, did sow, irrigate, and till the land, did alter the course of rivers, did sew their clothes, and did construct a system of pan-continental government that generated peace and prosperity, it is likely we will admire and love our land all the more. Admiration and love are not sufficient in themselves, but they are the foundation of a more productive interaction with the continent. "Behaving as if the First Peoples were mere wanderers across the soil and knew nothing about how to grow and care for food resources is a piece of managerial pig-headedness."

From Dark Emu, by Bruce Pascoe

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

FANNY COCHRANE SMITH // LINGUIST

“She was an Aboriginal linguist. She was born in Tasmania, as is thought to have been the last fluent speaker of its own language. In her final years, she made wax cylinder recordings of Tasmanian Aboriginal songs and speech, which in 2017 were inducted into the UNESCO Australian Memory of the World Register as the only audio recordings of any of Tasmania’s indigenous languages.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Girrakool -place of waters

Brisbane Water National Park was originally established in 1959 when an area of 6,000 hectares was dedicated for public recreation, the park is now more than 12,000ha in size.

Girrakool picnic area was established soon after the appointment of the first ranger, Mr Jack Higgs, in 1961.

The establishment of a picnic area and development of walking trails at Girrakool was carefully planned to provide access to the beautiful waterfalls and abundant native flora. Girrakool was officially opened on 11 September 1965.

This beautiful reserve takes its name from nearby Brisbane Water which can be seen from a number of places within the park. The park is a combination of rugged bushland, beautiful wildflowers and spectacular waterfalls and creeks.

Aboriginal people have used the area for centuries and there are Aboriginal engravings on many of the sandstone outcrops.

The importance of the area for Aboriginal people is reflected in the two Aboriginal places in the park, Bulgandry Art Site Aboriginal Place and Kariong Sacred Land Aboriginal Place."

#steventure#blog#australia#hike#hiking#bushwalk#brisbane water#waterfall#brisbane water national park#girrakool#piles creek#aboriginal history#bushwalking#bushwalking blog#hiking blog#travel blog#darkinyung#goanna#central coast bushwalks#nsw national park

0 notes

Text

To most of us, the rush of the oceans that followed the last ice age seems like a prehistoric epoch. But the historic occasion was dutifully recorded—coast to coast—by the original inhabitants of the land Down Under.

Without using written languages, Australian tribes passed memories of life before, and during, post-glacial shoreline inundations through hundreds of generations as high-fidelity oral history. Some tribes can still point to islands that no longer exist—and provide their original names.

0 notes

Text

Uncle Jack Charles

“...there are many Aboriginal people who are gay, both men and women, and ... we’re so proud we’ve made our mark and stamped our ground. ... us gay and Indigenous mob, we’re fringe dwellers twice over, and that’s what gives us great strength.”

Bunurong and Wiradjuri man Uncle Jack Charles was taken from his mother at just four months old as part of the Australian government policy of forcibly assimilating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. These children are now known as the Stolen Generation.

Raised in a Salvation Army boys’ home, and then by a white foster family, Jack grew up believing he was an orphan, and had no idea he was Aboriginal until he was 17. When he left his foster home at 17 to seek out his birth family, his foster mother called the police. When Jack was finally able to connect with his family, he described himself as being born again in his Aboriginality.

Uncle Jack had his first acting role at 17, in a community production of African-American playwright Lorraine Hansberry’s Raisin in the Sun. He went on the become a stalwart of Indigenous theatre in Australia, and in 1971, co-founded the country’s first Indigenous theatre group, Nindethana, which achieved international acclaim.

Throughout his life, Uncle Jack dealt with homelessness and heroin addiction, and spent time in jail for theft. As a burglar, he deliberated targeted wealthy Melbourne neighbourhoods, saying later "I robbed as rent collection for stolen Aboriginal land!"

Having experienced the prison system himself, Uncle Jack became a tireless advocate for young incarcerated men, especially Indigenous men. In 2010, he starred in a one-man show called Jack Charlves v The Crown, where he explored his life, and his struggles with a government bureaucracy that said a man with a criminal record couldn’t be allowed to mentor prisoners.

Uncle Jack was openly gay, although romance was never a big part of his life. He described giving the Welcome to Country at Melbourne’s pride event, Midsumma, as one of his most cherished duties.

Uncle Jack passed away on 13 September 2022.

Keep an eye on this blog throughout the week as we continue highlighting queer Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander history and culture for NAIDOC Week.

[Image: Uncle Jack holding his record Son of Mine]

298 notes

·

View notes

Text

Admittedly, my research is lacking in the veracity of my claim here. But to my understanding, traditional ochre hand stencil art is still practised in Australia by various aboriginal mobs/cultures.

youtube

Here is one explanation of meaning from Malyankapa man Mark Sutton on traditional land in Mutawintji, Western NSW.

40,000 years ago, early humans painted hands on the wall of a cave. This morning, my baby cousin began finger painting. All of recorded history happened between these two paintings of human hands. The Nazca Lines and the Mona Lisa. The first TransAtlantic flight and the first voyage to the Moon. Humanity invented the wheel, the telescope, and the nuclear bomb. We eradicated wild poliovirus types 2 and 3. We discovered radio waves, dinosaurs, and the laws of thermodynamics. Freedom Riders crossed the South. Hippies burned their draft cards. Countless genocides, scientific advancements, migrations, and rebellions. More than a hundred billion humans lived and died between these two paintings—one on a sheet of paper, and one on the inside of a cave. At the dawn of time, ancient humans stretched out their hands. And this morning, a child reached back.

#Malyankapa#Mutawintji#NSW#Australia#Mark Sutton#Hand stencil#art#indigenous#indigenous art#ochre#aboriginal#aboriginal australia#aboriginal history#indigenous history#Youtube

92K notes

·

View notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://www.knewtoday.net/resilience-and-revival-five-stories-of-aboriginal-life-in-australia-after-european-invasion/

Resilience and Revival: Five Stories of Aboriginal Life in Australia After European Invasion

The European invasion of Australia in the late 18th century had a profound and lasting impact on the Aboriginal people, the continent’s original inhabitants. The arrival of European settlers brought significant changes to the social, cultural, and political landscape, leading to a complex and often painful history for Aboriginal communities. However, amidst the challenges and injustices, stories of resilience, cultural revival, and a quest for justice have emerged, painting a picture of a people determined to preserve their heritage and create a better future.

In this collection of stories, we delve into five significant narratives that shed light on the experiences of Aboriginal Australians after the European invasion. These stories highlight both the struggles and the triumphs, offering a glimpse into the diverse ways in which Aboriginal communities have navigated the post-invasion era.

From the heart-wrenching tale of the Stolen Generation, where Aboriginal children were forcibly separated from their families to the inspiring fight for land rights and self-determination, these stories encapsulate the profound impact of European colonization on the Aboriginal people and their ongoing efforts to reclaim their cultural identity.

We will also explore the pivotal moment of reconciliation and apology, as the Australian government acknowledged the injustices of the past, offering hope for healing and unity. Additionally, we will delve into the resurgence of Aboriginal art and cultural expression, as Indigenous artists reclaim their narratives and share their rich heritage with the world.

Lastly, we will uncover the remarkable stories of Aboriginal land and sea management practices, where traditional ecological knowledge blends with modern conservation principles, creating sustainable ecosystems and economic opportunities for Aboriginal communities.

These stories weave together a narrative of strength, resilience, and determination among Aboriginal Australians. They provide a deeper understanding of the ongoing journey toward justice, reconciliation, and the revitalization of Aboriginal culture. Through these tales, we are reminded of the importance of acknowledging and respecting the legacy of the Aboriginal people and working towards a more inclusive and harmonious future.

The Stolen Generation

The Stolen Generation refers to a dark chapter in Australian history when Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children were forcibly removed from their families by the Australian government and placed into institutions or with non-Indigenous foster families. This policy, which spanned from the late 1800s to the 1970s, aimed to assimilate Indigenous children into Western culture, severing their ties to their families, culture, and land.

The impact of the Stolen Generation on individuals and communities was profound and long-lasting. Children were taken away without consent or understanding, often experiencing trauma, loss of cultural identity, and a sense of displacement. Families were torn apart, and the bonds of kinship and community were shattered. The effects of this policy continue to be felt today, with intergenerational trauma and ongoing struggles for healing and reconciliation.

One example that highlights the experiences of the Stolen Generation is the story of Doris Pilkington Garimara, as depicted in her book “Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence” (later adapted into a film). Doris, along with her sister and cousin, was forcibly taken from her mother in 1931 when she was just four years old. They were transported to Moore River Native Settlement, hundreds of miles away from their home.

Determined to return to their family and their traditional lands, the three girls embarked on a remarkable journey, following the Rabbit-Proof Fence that stretched across the Western Australian outback. Despite the challenging conditions and the constant threat of capture, they relied on their knowledge of the land and their resilience to navigate their way home.

Doris Pilkington Garimara’s story, along with countless others, sheds light on the courage, strength, and resilience of the Stolen Generation. It serves as a testament to their enduring connection to their culture and their unyielding spirit in the face of adversity.

The recognition of the Stolen Generation and the injustices they suffered led to a national apology by then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in 2008. The apology aimed to acknowledge the pain and suffering caused by the forced removals and to begin the process of healing and reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

The stories of individuals like Doris Pilkington Garimara and the countless others impacted by the Stolen Generation serve as a reminder of the ongoing need for understanding, compassion, and support for healing the wounds inflicted upon Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. It is through listening, acknowledging, and learning from these stories that a path toward reconciliation and justice can be forged.

Land Rights Movement

The Land Rights Movement in Australia emerged as a response to the dispossession and marginalization of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples from their traditional lands following the European invasion. It sought to address the historical injustices, assert Indigenous rights to land, and regain control over their ancestral territories. The movement gained momentum in the 1960s and 1970s, and its efforts have resulted in significant legal and social changes.

One prominent example of the Land Rights Movement is the Gurindji strike and the subsequent Wave Hill Walk-Off in 1966. Led by Vincent Lingiari, the Gurindji people, were working as cattle station laborers in Wave Hill, Northern Territory, demanding better working conditions and the return of their traditional lands.

The Wave Hill Walk-Off was a groundbreaking event that captured national attention. More than 200 Aboriginal workers, together with their families, left the Wave Hill cattle station, camping at Daguragu (formerly known as Wattie Creek) and refusing to work until their demands were met. Their actions sparked a larger movement for land rights and provided a rallying point for Aboriginal activism across the country.

The Gurindji strike and the Wave Hill Walk-Off led to the establishment of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976. This legislation recognized Aboriginal land rights in the Northern Territory and paved the way for the return of land to Indigenous ownership. It was a significant milestone in the Land Rights Movement, empowering Aboriginal communities and enabling them to reclaim their ancestral lands.

Another significant example is the Native Title Act of 1993. This legislation recognized the existence of native title, the recognition of Indigenous land rights based on traditional connections to the land, and established a legal framework for Indigenous communities to make native title claims. The Native Title Act aimed to address the historical injustices and provide a pathway for land rights reconciliation.

The Mabo v Queensland (No 2) case, a landmark High Court decision in 1992, played a pivotal role in the recognition of native title. Eddie Mabo, along with other Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal plaintiffs, challenged the doctrine of terra nullius (the notion that Australia was unoccupied prior to European settlement) and successfully argued for the recognition of native title rights.

These examples highlight the activism, perseverance, and collective efforts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in their fight for land rights. The Land Rights Movement has led to the return of significant areas of land to Indigenous ownership, enabling communities to reconnect with their traditional lands, practice cultural traditions, and exercise self-determination.

The struggle for land rights is ongoing, and Indigenous communities continue to assert their rights and negotiate for recognition and control over their lands. The Land Rights Movement remains a critical aspect of the broader movement for Indigenous rights, self-determination, and reconciliation in Australia.

Reconciliation and the Apology

Reconciliation and the Apology refer to significant steps taken in Australia to acknowledge and address the historical injustices and mistreatment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples following the European invasion. These initiatives aim to foster healing, understanding, and a path toward unity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Reconciliation: Reconciliation in Australia involves acknowledging the past injustices, promoting understanding, and working towards a more respectful and equitable future for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The concept emphasizes the importance of building positive relationships, respecting Indigenous cultures and heritage, and addressing the ongoing issues faced by Indigenous communities.

The journey toward reconciliation encompasses various aspects, including education, awareness, community engagement, and policy changes. It involves acknowledging and respecting the diverse cultures, languages, and histories of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, as well as supporting self-determination and empowering Indigenous communities.

Apology: The Apology refers to the formal apology delivered by then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd on behalf of the Australian government to the Stolen Generations on February 13, 2008. The Stolen Generations were the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who were forcibly removed from their families and communities under government policies of assimilation.

In his speech, Rudd acknowledged the pain, trauma, and injustices suffered by the Stolen Generations and their families. The Apology sought to provide recognition, validation, and healing, aiming to restore dignity and respect to those who had endured the devastating impacts of forced removal.

The Apology represented a significant moment in Australian history, symbolizing a national commitment to acknowledging past wrongs and working towards reconciliation. It sparked hope for a renewed relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, promoting understanding, healing, and a shared future.

Following the Apology, various initiatives and programs have been implemented to support reconciliation efforts, including increased funding for Indigenous education, health services, and community development. National Reconciliation Week, held annually from May 27 to June 3, provides an opportunity for Australians to reflect on the importance of reconciliation and to participate in events that promote understanding and unity.

Reconciliation and the Apology are ongoing processes, requiring continued commitment, understanding, and meaningful actions from all Australians. The goal is to create a more inclusive, just, and equitable society where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples can thrive, celebrate their cultures, and contribute to the nation as equal partners.

These initiatives mark important milestones in Australia’s journey towards healing, recognition, and forging stronger relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. They represent a commitment to learning from the past, acknowledging the ongoing impacts of colonization, and working towards a shared future of reconciliation and justice.

Land and Sea Management

Land and Sea Management in Australia refers to the Indigenous-led practices and initiatives aimed at preserving and sustainably managing the natural environment, including land, waterways, and marine ecosystems. These practices combine traditional ecological knowledge with modern conservation principles to ensure the long-term sustainability of ecosystems while supporting Indigenous cultural connections to the land and sea.

Indigenous land and sea management initiatives recognize the deep understanding and stewardship of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, who have maintained sustainable relationships with the environment for thousands of years. These initiatives encompass various activities, such as fire management, cultural mapping, species monitoring, habitat restoration, and sustainable fishing practices.

One notable example of Indigenous land and sea management is the work of the Yolngu people in Arnhem Land, Northern Territory. Through their organization, the Dhimurru Aboriginal Corporation, the Yolngu people have been actively involved in caring for their ancestral lands and coastal areas.

Dhimurru’s initiatives include fire management practices, where controlled burning is utilized to maintain healthy ecosystems, reduce the risk of wildfires, and promote the regeneration of native plants and animals. The Yolngu people also engage in sea management, monitoring and protecting marine species, and implementing sustainable fishing practices to ensure the preservation of coastal resources.

Another example is the Djelk Rangers program in West Arnhem Land. The program, established by the traditional owners of the region, involves Indigenous rangers working to conserve and manage the land, rivers, and coastal areas. The Djelk Rangers are involved in activities such as weed and pest management, cultural site protection, and land and waterway monitoring. They also collaborate with scientists and researchers to combine traditional knowledge with scientific approaches, fostering a holistic approach to land and sea management.

Indigenous land and sea management practices not only contribute to biodiversity conservation but also support cultural preservation, economic development, and community empowerment. These initiatives provide employment and training opportunities for Indigenous communities, enabling them to reconnect with their cultural heritage, pass on traditional knowledge to future generations, and assert their rights and responsibilities as custodians of the land and sea.

The success of Indigenous land and sea management programs has led to increased recognition and support from government, non-governmental organizations, and the broader community. Collaborative partnerships have been formed, enabling Indigenous communities to have a greater say in land management decisions and policies.

Overall, Indigenous land and sea management initiatives exemplify the intersection of environmental conservation, cultural preservation, and community development. These practices demonstrate the importance of traditional ecological knowledge and the role of Indigenous communities as custodians of the land and sea, leading to more sustainable and inclusive approaches to environmental stewardship.

Aboriginal Art and Cultural Revival

Aboriginal Art and Cultural Revival in Australia has played a vital role in preserving and celebrating Indigenous traditions, stories, and cultural heritage. Aboriginal art encompasses a wide range of artistic expressions, including paintings, sculptures, carvings, weaving, and more. It is deeply rooted in the spiritual and cultural beliefs of Aboriginal communities and serves as a powerful medium for storytelling and connection to the land.

Aboriginal art has gained international recognition for its unique styles, vibrant colors, and intricate designs. It provides a visual representation of the rich cultural diversity and deep connection to Country held by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

One example of Aboriginal art and cultural revival is the Western Desert Art Movement. It emerged in the 1970s in remote communities of Central Australia, such as Papunya, and is often credited as the catalyst for the contemporary Aboriginal art movement. Artists like Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri and Emily Kame Kngwarreye played significant roles in popularizing Aboriginal art and introducing it to a broader audience.

The Western Desert Art Movement revitalized traditional art practices and storytelling techniques, leading to the establishment of art centers in Aboriginal communities. These art centers provide a space for artists to create and share their work, ensuring cultural knowledge is passed down to future generations.

Contemporary Aboriginal artists draw inspiration from Dreamtime stories, ancestral connections, and the natural environment. They employ a diverse range of styles and techniques, ranging from dot paintings to intricate cross-hatching and more abstract forms. Each artwork holds deep cultural significance and often carries messages related to identity, land rights, spirituality, and social issues.

The success and recognition of Aboriginal art have also brought economic opportunities to Indigenous communities. Art sales, exhibitions, and licensing agreements provide a sustainable income source for artists and their communities, fostering self-determination and empowering Aboriginal individuals and art centers.

In recent years, Aboriginal art has been increasingly incorporated into public spaces, galleries, and museums, both in Australia and internationally. It serves as a means of education, raising awareness about Aboriginal culture and history, and challenging stereotypes and misconceptions.

The cultural revival facilitated by Aboriginal art extends beyond visual representations. It has influenced other creative disciplines, including music, dance, storytelling, and film, contributing to a broader renaissance of Indigenous cultural practices and expressions.

Aboriginal art and cultural revival not only provide a platform for Indigenous voices and narratives but also contribute to a deeper understanding and appreciation of Australia’s rich cultural tapestry. They serve as a testament to the resilience and ongoing presence of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and their commitment to preserving and sharing their cultural heritage with the world.

#Aboriginal Art#Aboriginal History#Cultural Revival#European Invasion#Indigenous Knowledge#Land Rights Movement#Reconciliation#Stolen Generation

0 notes

Text

Source: New Day Dawning; The Early Years Of Sydney’s Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras

#Australian gay history#gay male positivity#gay men#Aboriginal lgbt history#Aboriginal history#gay First Nations history#lgbt#image#photo#personal

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

there was a swedish guy in like the early 1900s that literally just traveled to Australia, attended a funeral of an indigenous person and then HE CAME BACK A FEW WEEKS LATER TO DIG UP THE BONES TO KEEP IN HIS COLLECTION!!!!

DO YOU HEAR ME??!!!

HE WENT ON A FUNERAL AND THEN CAME BACK TO DIG UP THE BONES!!!!!!!

Thankfully the aboriginal people there had heard he had dug up bones previously and they moved the grave.

AND WHEN HE DISCOVERED THIS HE GOT MAD AND SAID THE ABORIGINAL PEOPLE COULDN'T BE TRUSTED

AHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH

#the guys name was Erik Mjöberg for anyone wondering#he was absolutely disgusting AND SMUGGLED BONES OF ABORIGINAL PEOPLE OUT OF AUSTRALIA#If this doesn't tell you about attitudes at the time towards indigenous people from europeans#I don't know what does#Sweden#History#aboriginal#hate crimes tw#i don't know if this counts as a hate crime but I'll still put it there to be safe#regardless it's still definitely a crime towards and disgusting treatment of indigenous people

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

^^^^ because I've seen a lot of this too, people just *saying* "manifest destiny" like it's an inspirational mantra, I'd like everyone who follows me to be aware that "manifest destiny" was the slogan for white colonizers throughout the aboriginal genocide in North America.

It appeared in all kinds of posters produced and distributed by the government with the sole purpose of encouraging colonizers to remove and destroy the original inhabitants.

The idea was that God created white people to be in command of the earth, dominant over all plants, animals, and other races, which were meant to serve them, and "manifesting your destiny" was whatever horrific actions they saw fit to make that "destiny" a reality.

"Manifest destiny" was not "good things will come if you work hard to make them happen".

"Manifest destiny" was "I will remove you from my rightful seat as God intended".

And it STILL MAINTAINS THAT MEANING.

Whatever you intend when you say "Manifest destiny", you need to know that it is the Seig Heil of North America.

Do Not Throw This Around.

i love grian. has anybody told him what 'manifest destiny' means though. because i am not sure if he realises,

#Sorry to hijack this is a very big concern of mine#It's a bit personal#Canada#America#History#Aboriginal history#Genocide

4K notes

·

View notes