#1922/1923

Text

Still Life With Dice

Paul Klee

Watercolour, chalk and ink on paper mounted on cardboard, 1922/1923

#Paul Klee#art#artist#painter#painting#still life#a lil surreal#Still Life With Dice#Watercolour chalk and ink on paper mounted on cardboard#1922/1923

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Horror movies of the 1920s

#horror#horror movies#horror movie#movie#movies#gifs#gif#horror gif#horror gifs#my gif post#my gif#my gifs#horror edit#horroredit#20s horror#nosferatu#nosferatu 1922#the phantom of the opera#the hunchback of notre dame#the cabinet of dr. caligari#the hunchback of notre dame 1923#the hands of orlac#Faust#the unknown 1927#the man who laughs#Cagliostro#Faust 1928#the phantom of the opera 1925#lon chaney#lon Chaney sr

444 notes

·

View notes

Text

Harrison Ford via AppleTV+ ~ "75th Annual Emmy Awards" ~ 01/15/24 ~ FOX

-WDD

#harrison ford#harrisonford#harrisance#witness the harrisance#apple tv#apple tv+#shrinking apple tv#shrinking#paul rhoades#bill lawrence#brett goldstein#comedy tv#comedy#1923tv#1922#yellowstone 1923#yellowstone#western#drama#taylor sheridan#paramount+#tv shows#tv series#emmys 2024#silver fox#still worth watchin#still got it#harrisonfordedit#love Harrison ford

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cosplay the Classics: Nazimova in Salomé (1922)—Part 1

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

The Importance of Being Peter: Nazimova’s Take on Wilde

With over two decades of professional acting experience behind her (six on the “shadow stage” of silent cinema), Alla Nazimova went independent. She was one of the highest paid stars in Hollywood at the start of 1922 when her contract with Metro ended. Almost exclusively using her own savings, Nazimova founded a new production company and immediately got to work on two films that reflected both a deep understanding of her own fan base and a faith in the American filmgoer’s appreciation for art.

Discourse around these films and their productions that have emerged in the century since their release are often peppered with over-simplifications or a lack of perspective. Focus is understandably placed on Salomé, as her first project, A Doll’s House (1922), has not survived. In part one of this series, I plan to contextualize Nazimova’s decision to commit Wilde’s drama to celluloid and examine the details of the adaptation. Then, in part two, I will cover how Salomé (and A Doll’s House) fits into the industry trends and the emergent studio system in the early 1920s.

While the full essay and more photos are available below the jump, you may find it easier to read (formatting-wise) on the wordpress site. Either way, I hope you enjoy the read!

Wilde’s Salomé: The Basics

Salomé was a one-act drama written by Oscar Wilde. In a creative challenge to himself, Salomé was one of Wilde’s first plays and he chose to write in French, which he did not have as complete a mastery of as of English. Wilde was directly inspired by the Flaubert story “Herodias,” which was, in turn, inspired by the short story which appears twice in the New Testament. The play was later translated into English and published with illustrations by artist Aubrey Beardsley. Wilde’s play was the basis of the opera of the same name by Richard Strauss. While both the opera and the play had been staged numerous times across Europe and in New York before Nazimova’s adaptation, Strauss’ opera was the main reference point for the story in the popular imagination of the time. The success of Strauss’ opera led to the popularization of the Dance of the Seven Veils and the accepted interpretation of the character as a classic femme fatale.

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

Nazimova’s Salomé: The Basics

When Nazimova announced her production of Salomé, she did so assured that she and Natacha Rambova, her art director, had a unique and creatively compelling interpretation of the story to warrant adaptation. Nazimova was not only the star and producer of Salomé, she adapted it from its source herself under her pen name Peter M. Winters. (Cheekily, contemporary interviews and profiles joke that “Peter” is one of her common nicknames.) Charles Bryant, credited as director, was as much the director of the film as he was Nazimova’s husband, which is to say, he is not known to have contributed much at all. It’s now accepted fact that Bryant acted as a professional beard (Bryant and Nazimova were also never legally married). The choice to credit Bryant was to offset the heat Nazimova was getting in the press at the time for “taking on too much.” Having Bryant’s name in the credits was a protective measure. Charles Van Enger was a talented, up-and-coming cinematographer who had been recommended to Nazimova following the inadequate cinematography of her Metro films.

Rambova was in charge of the art direction, set designs, costumes, and makeup. Nazimova and Rambova had become close artistic collaborators after Nazimova hired Rambova to design the fantasy sequence for her film Billions (1920, presumed lost). [You can learn more about Rambova’s career here.] Both women valued their work above all else. Both were convinced that film could be art. Both had the gumption to believe that they could make a lasting mark on cinema’s recognition as a legitimate medium of artistic expression.* (Spoiler: even though Salomé was not an unqualified box-office success, they were right.)

Photo of the Salomé crew from Exhibitors Herald, 29 April 1922. Original caption: Nazimova ordered this picture taken that she might be reminded of the real pleasure encountered in every stage of the production of “Salome.” Top, left to right: Monroe Bennett, laboratory; Charles Bryant, director; Mildred Early, secretary; John DePalma, assistant director. Second row: Sam Zimbalist, cutter; Natacha Rambova, art director; Charles J. Van Enger, cameraman; the star; R. W. McFarland, manager. Front row: Neal Jack, electrician; Paul Ivano, cameraman; Lewis Wilson, cameraman.

Nazimova’s independence was at least partly spurred on by feeling creatively bereft from her work at Metro. In a 1926 interview with Adela Rogers St. Johns, Nazimova said:

“You asked me why I made ‘Salome.’ Well—’Salome’ was a purgative. […] It seems impossible now that I should ever have been asked to play such parts as ‘The Heart of a Child’ and ‘Billions.’ But I was. And instead of saying, ‘No. I will not play such trash. I will not play roles so wholely [sic] unsuited to me in every way,’ I went on and played them because of my contract, and they ruined me.

“WORSE than that, they [made] me sick with myself. So I did ‘Salome’ as a purgative. I wanted something so different, so fanciful, so artistic, that it would take the taste out of my mouth. ‘Salome’ was my protest against cheap realism. Maybe it was a mistake. But—I had to do it. It was not a mistake for me, myself.”

Given that Nazimova now had full creative freedom, outside of the confines of the Hollywood film factory, why were A Doll’s House and Salomé the first works she gravitated towards?

Initially, Nazimova had conceived of a “repertoire” concept for her productions: one shorter production (A Doll’s House) and one feature-length production (Salomé), which could be distributed and exhibited together. Once production was underway for ADH, Nazimova instead chose to make it a feature. The reasons for this decision that I found in contemporary sources are purely creative, but I don’t think it’s too much of a presumption that this may have been a financial choice, as profits from ADH (which unfortunately wouldn’t materialize—more on that in part two!) could have been cycled into Salomé’s production.

Ibsen was not popular source material for the silent screen, but Nazimova’s name and career was forever tied to the playwright as she is considered the actress who brought Ibsen to the US. (Minnie Maddern Fiske starred in a production of Hedda Gabbler in the US before Nazimova, however it failed to raise the profile of the writer.) Nazimova’s stage productions of Ibsen’s work proved that there was an audience for it in the US—both in New York and on tour. Superficially, ADH might seem like a risky proposition, but Nazimova had good reason to believe it had both artistic and box office potential. (Again, I’ll delve into why it might not have found its audience in part two.)

Nazimova as Nora in A Doll’s House

Though ADH is now lost, we know from surviving materials that Nazimova understood that by 1922 The New Woman archetype was already becoming passé to the post-war/post-pandemic generation of young women. Nazimova endeavored to translate the play in a way that would resonate with 1920s American womanhood. (How well she succeeded is lost to time unless we are lucky enough to recover a copy of the film.) Likewise, Nazimova approached her adaptation of Salomé with a keen eye for the concerns of modern independent women.

——— ——— ———

*Incidentally, both women also had a personal connection to Wilde. Nazimova was a close friend and colleague of Elizabeth Marbury, who worked as Wilde’s agent. Rambova spent summers at her aunt’s (Elsie de Wolfe) villa in France where she lived with her longtime partner, Marbury.

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

The Adolescence of Salome

In the decade following the end of the First World War, there was a great cultural shift for women in America, who experienced and pursued greater independence in society—particularly young and/or unmarried women. This quality was emblematized in the Flappers and the Jazz Babies, but even women who didn’t participate in these subcultures lived lifestyles removed from “home and family” ideals of the past. The lifestyle change was mirrored aesthetically. As Frederick Lewis Allen describes in Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s:

“These changes in fashion—the short skirt, the boyish form, the straight, long-waisted dresses, the frank use of paint—were signs of a real change in the American feminine ideal (as well, perhaps, as in men’s idea of what was the feminine ideal). […] the quest of slenderness, the flattening of the breasts, the vogue of short skirts (even when short skirts still suggested the appearance of a little girl), the juvenile effect of the long waist,—all were signs that, consciously or unconsciously, the women of this decade worshiped not merely youth, but unripened youth […] Youth was their pattern, but not youthful innocence: the adolescent whom they imitated was a hard-boiled adolescent, who thought not in terms of romantic love, but in terms of sex, and who made herself desirable not by that sly art that conceals art, but frankly and openly.”*

Allen’s summary of youthful womanhood in the 1920s resounds so clearly in the character design and performance of Nazimova’s Salomé, it’s apparent that she and Rambova were thoroughly informed by contemporary trends around young/independent women. Belén Ruiz Garrido puts it succinctly in her great essay on the film “Besare tu boca, Iokanaan. Arte y experiencia cinematografica en Salomé de Alla Nazimova:”

“Las concomitancias con la flapper o la it girl de los felices años veinte son evidentes. Se muestra mimosa, pero su seducción es como un juego de niña. / The similarities with the flapper or the it girl of the roaring twenties are obvious. She performs affection, but her seduction is like child’s play.” (translation mine)

Nazimova was also fully conscious that her fanbase was predominantly female and that she held significant appeal for younger women. From the moment she signed her first American theatrical contract with Lee Shubert, Nazimova’s status as a queer idol was already being established.

“The women… were enthusiastic about [Nazimova]… [At the hotel, the] ladies’ entrance was always crowded with women waiting for her to return from the theatre. It is much better that she should be exclusive and meet no one if possible. They regard her as a mystery. And there are other damned good reasons besides this one.” – citation: A. H. Canby to Lee Shubert, December 29, 1908**

While women, particularly middle-class women, were emerging as a prominent consumer group in the US, Nazimova’s popularity peaked on stage and on screen. Arriving in Hollywood, Nazimova also continued her trend of surrounding herself socially and professionally with other queer women. Profiles and interviews of Nazimova in the Hollywood press often contained coded language about her queerness as a wink and nudge, usually but not always accompanied by mention of her “husband” Charles Bryant.

This well-developed understanding of her primary fanbase led her to break from popular presentations of the character as an embodiment of monstrous feminine sensuality. Instead, Nazimova chose to present the character as an adolescent. While Nazimova was the first to put this read on the character on film, Marcella Craft chose an adolescent interpretation in a production Strauss’ opera in Munich and Hedwig Reicher was a teenager when she assayed the role and played it accordingly (also in Germany). (Maybe not insignificantly, Reicher was also working in Hollywood at the time of Salomé’s production.)***

This is the American pop culture landscape we’re talking about here, so of course women’s independence was rapidly codified for capitalization. Young women were moralized at for not conforming to traditional gender roles while simultaneously being framed as sexually desirable in order to sell consumer goods (including motion pictures!). The American way. It’s hard to not see social commentary in Nazimova’s reworking of this icon of wanton femininity for a new generation.

This isn’t to suggest that Nazimova’s Salomé glorifies the character, but rather that making Salomé a teen adds layers of complexity to the production. Considering it in conversation with her predecessors, Salomé isn’t even named in the New Testament stories. Flaubert built out the character with 19th century concerns in mind (though his story is more about Herod & Herodias) and Wilde shifted even more focus to Salomé. Nazimova continued that trend with her version of Salomé—an impetuous child too young and ill-equipped to constructively deal with the horrible environment she was brought up in. (Might that resonate with a generation of young people disillusioned by a World War and a pandemic?)

As Nazimova/Peter wrote in the opening intertitles to the film:

“It is at this point that the drama opens, revealing Salome who yet remains an uncontaminated blossom in a wilderness of evil.

“Though still innocent, Salome is a true daughter of her day, heiress to its passions and its cruelties. She kills the thing she loves; she loves the thing she kills, yet in her soul there shines the glimmer of the Light and she sets forth gladly into the Unknown to solve the puzzle of her own words——”

My cosplay of Nazimova as Salomé

As Salomé was an experiment in pantomime for screen acting, it’s worthwhile to look at how Nazimova embodies this image of youth in her performance. In the first scenes, Salomé’s facial expressions are pouty and her movements like a bored child’s. Her wig emphasizes every movement she makes with a flurry of pearls and creates a neotenous silhouette for the character. When denied access to Jokanaan, her facial expressions are imperious, but the imperiousness of a spoiled child. She swings on the bars imprisoning Jokanaan as if they are a jungle gym. As she “charms” Narraboth, her expressions and body language shift toward a scheming energy with barely concealed artifice, displaying a distinct lack of sophistication—like she’s trying to angle a second serving of ice cream not exacting a favor of a servant that could cost his life.

Perhaps most crucially, Salomé’s adolescence emphasizes the inappropriateness of men’s gaze upon her. Wilde’s drama is built around rhythmic repetition in the dialogue—a key repetition being the act of looking. Though the play is only one act, some form of “regarder” in relation to Salomé is repeated nineteen times—most often in some form of “don’t look at her” or “you shouldn’t look at her that way.” As Salomé is a silent film, to repeat this in intertitles nineteen times in intertitles would be absurd. Throughout the film, frequent close ups are strategically employed to visually recreate the rhythmic emphasis on gazing. (The purpose of this device seems to have been lost on one reviewer for Exhibitors Herald who said in his review: ”too many close ups.”) Additionally, the motif is foregrounded by front-loading the mentions of looking. As soon as the opening narration ends, we’re introduced to Herod behaving lecherously toward Salomé and Herodias telling him not to look at her. The perversity of Herod is amplified here because Salomé is not only his niece and his step-daughter, but also a child. This scene is followed by Narraboth and the page having a similar interaction, albeit with a different tone.

As Nazimova put it herself in a profile in Close-Up magazine:

“The men about her are obnoxious; they cannot even look upon her decently. She loathes them all. Even the Syrian [Narraboth] whose approach is of all the most respectful and decorous, is of his times and his love is tempered with the alloy of lust.”

In the film, Salomé’s rage against Herod is justified, and her rage against Jokanaan is a raw confusion of emotions—she doesn’t have the capacity to act constructively. When the first unfortunate man commits suicide over her, she barely takes notice, establishing Salome’s blasé attitude toward death. When the second man takes his life this time directly in front of her, Salomé only notices after almost tripping on his body. Her response is giving the body an annoyed kick for tripping her! The key phrase of the drama is “The mystery of love is greater than the mystery of death.” Salomé is surrounded by death, enveloped by it, but love (of any kind) is unknown to her until Jokanaan. So, when her love of Jokanaan is rebuked, she reverts to the only response that has been nurtured into her: death.

Nazimova’s Salomé is a perfect surviving example of a quality of her acting described in an uncredited review of Nazimova’s theatrical work:

“If the actress you’re seeing knows what she’s saying but you don’t, it’s Mrs. [Minnie Maddern] Fiske. But if the actress doesn’t know what she is saying and you do, it’s Alla Nazimova.”****

We as viewers understand what Salomé is going through, but she is being psychologically buffeted by fate and circumstance without ever comprehending the nature of it. The tumultuous feelings brought on by Salomé’s first brush with the spiritual (rather than the sexual), launches her into an accelerated ripening of her cruelty. This is masterfully communicated by Nazimova through facial expression and body language and accentuated by Rambova’s costuming.

As Herman Weinberg put it in his essay “The Function of the Actor:”

“The true film crystalizes action for us. ‘To see eternity in a grain of sand,’ the poet said. ‘To see a life cycle in an hour and a half’ is the modern screen parallel.”

Because of the emotional scale of Nazimova’s performance in Salomé, it has been variously described as “bizarre” or “grotesque”—though not always said derogatorily. That’s on point, as Nazimova’s performance is only one expression of her protest against realism in the film.

——— ——— ———

*If you’re interested in the 1920s at all, I highly recommend Allen’s book. The section this quote is from has a detailed survey of changes in American women’s lifestyles throughout the 1920s.

**as quoted in “Alla Nazimova: ‘The Witch of Makeup’” by Robert A. Schanke

***Gavin Lambert’s biography of Nazimova intimates that she referenced the 1917 Tairov production of Wilde’s Salomé, which she reportedly had a detailed description of. Reading about the production for myself in Mark Slonim’s Russian Theatre: from the Empire to the Soviets, I’m not sure what precisely she would have drawn from this production. It doesn’t seem to have much in common with the ‘22 film at all. That said, in a 1923 interview with Malcolm H. Oettinger in Picture-Play Magazine, Nazimova admits that in preparing for the film, she compiled a large scrapbook of previous productions and artistic interpretations of the story and character. Unfortunately, though Lambert clearly did voluminous research for his biography, his presentation and interpretation leaves a lot to be desired. Most of the things I tried to verify or try to find more information on from the book proved to be misrepresentations or were factually incorrect. So, I’m avoiding quoting Lambert without verification, unless what I’m citing is directly taken from a primary source; like a quote from Nazimova’s correspondence.

****quotation is from an uncredited clipping held by the Nazimova archive in Columbus, Georgia as quoted in Gavin Lambert’s biography

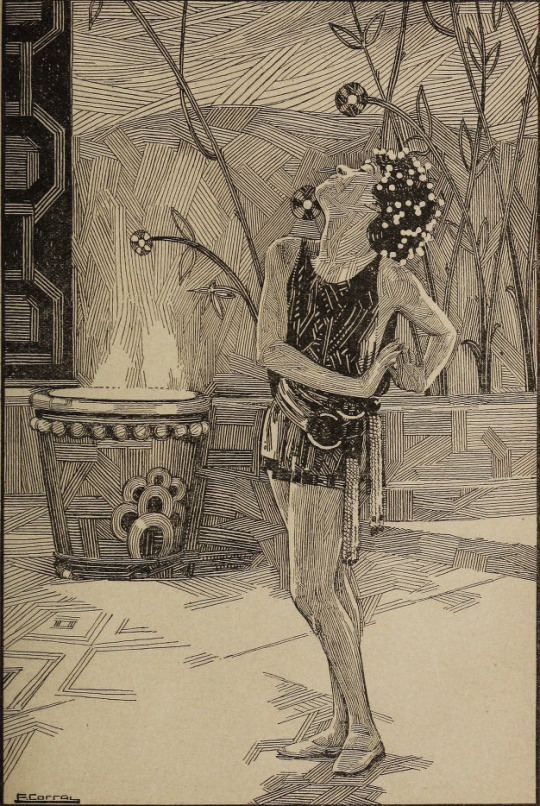

Illustration of Nazimova as Salomé by F. Corral from The Story World, March 1923

Nazimova and Rambova’s Modernist Phantasy

The assurance that Rambova and Nazimova felt that they had something new to bring to Salomé was obviously not solely founded in a character interpretation updated for the screen and for the decade. The two crafted a singular work born of pastiche in a manner that genuinely had not been done before in the American film industry. It’s often repeated that Salomé is America’s first art film. This may have its origin in promotional materials* made for the initial release of the film. Before the film’s official release, Bryant, Nazimova, and Paul Ivano (assistant camera & Nazimova’s on-again-off-again lover) arranged preview screenings and a few reviews from those screenings mention in some form that Salomé was a direct retort to the notion that art cannot be made with a camera.

What constituted the Nazimova/Rambova strategy to elevate film to the status of art? Both women had around six years of experience working in film (twelve collectively), but both came from a live performance background—theatrical acting and ballet respectively. Salomé is a film based on a stage play (though not strictly based on any one production of that play). Salomé inherits its symbology (first and foremost the moon) from its source material, but the filmmakers found creative ways of communicating and remixing symbols for the camera. The art design is inspired by Aubrey Beardsley’s illustrations for a printed edition of the play, though Rambova pulled more broadly from art-nouveau to devise designs that are in no way unoriginal.

As for the much discussed Dance of the Seven Veils, in my opinion, Nazimova’s execution is inspired by the dance described in Flaubert’s “Herodias” rather than a previous live performance.

“Again the dancer paused; then, like a flash, she threw herself upon the palms of her hands, while her feet rose straight up into the air. In this bizarre pose she moved about upon the floor like a gigantic beetle; then stood motionless.

“The nape of her neck formed a right angle with her vertebrae. The full silken skirts of pale hues that enveloped her limbs when she stood erect, now fell to her shoulders and surrounded her face like a rainbow. Her lips were tinted a deep crimson, her arched eyebrows were black as jet, her glowing eyes had an almost terrible radiance; and the tiny drops of perspiration on her forehead looked like dew upon white marble.”

Clearly, I’m not implying that what’s described above is exactly what we see on screen. My thought instead is that Nazimova may have drawn inspiration for the dance to be provocative in an uncanny way instead of provocative in a conventionally sensuous way. What we do see on screen is a distinct lack of practiced sensuality and an element of menace. The former comes both from Salomé’s youthfulness and from the logic that, as Salomé has already gotten Herod to give her his word in front of dignitaries, there’s no need for seduction. The latter is brought on by the expression of Salomé’s fractured emotional state and feelings about Herod. In execution, the use of close-ups again serves a major purpose. Intercutting close-up reactions from those gathered at the court provides a crescendo to the motif of looking, which is then pivotally reversed in the kiss scene. Cutting to close-ups of Salomé’s face accents the ecstatic and maniacal quality of the dance. Together this variation of shots creates an effect that could only work on film.

Salomé has a significant appreciation for its non-cinematic antecedents, but filtered through the prism of Nazimova’s and Rambova’s own creative strengths and sensibilities—a melding of theater and graphic art into something not only fresh but also totally cinematic.

It speaks to their filmmaking skill that all of these ideas and influences do in fact come together as a cohesive yet wholly unconventional film. Some critics of Salomé (both contemporary and modern) will cite vague notions of theatricality, or state that the film is only a series of tableaux, or that the limited sets don’t depart enough from a stage presentation. Art is in the eye of the beholder, but I think whether those specific elements preclude Salomé from being cinematic is a matter of perspective.

The oversized, stylized nature of Salomé’ssets might at first register as theatrical, but those same sets also serve to amp up the anti-real nature of the film. It’s uncharitable to Rambova to suggest that this artificiality was not a conscious artistic decision. If you have seen the sequences she designed with Mitchell Leisen for De Mille’s Forbidden Fruit (1921) then you have seen her demonstrated understanding of how designs register on camera. The gorgeously executed lighting effects in Salomé that are employed to to sublimate tone shifts could feasibly be recreated in a theatrical setting, here, filtered through the camera of Van Enger, register as thoroughly cinematic.

To once again quote “The Function of the Actor” by Weinberg:

“In nine movies out of ten (most particularly those emanating from the film factories of Hollywood), the actors stand around and talk to each other, relieved only by periodic bursts of someone going in or out of a doorway. (Sixty percent of the action in the average Hollywood movie consists of people going in and out of doors.) […]

“The actor going through a doorway may be a necessary device on the stage, to get him on and off. But Pudovkin has made a neat distinction between the realities of stage and screen: ‘The film assembles the elements of reality to build from them a new reality proper to itself; and the laws of time and space that, in sets and footage of the stage are fixed and fast, are in the film entirely altered.’ On the stage, that is, an event seems to occur in the same length of time it would occupy in life. On the screen, however, the camera records only the significant parts of the event, and so the filmic time is shorter than the real time of the event.”

Weinberg cites Pudovkin in an amusing but illustrative way here. People may throw “overly theatrical” or “stagey” casually, but more often than not the distinction between theatrical/cinematic comes down to how space and time is traversed. Even if the base material, a narrative drama for example, is shared between stage and screen, there should be a thoughtful construction of geography and chronology. Could Salomé have played more creatively with space? Perhaps. But, for a film made in early 1922, its creative geography isn’t all that uninventive. The majority of the action in Salomé takes place exclusively on one set, so it does rely a lot on the types of comings and goings that Weinberg identifies with theatre. That said, there are some comings and goings that forcefully pull the audience away from the feeling of stagey-ness. The most consequential occurs in the scene with the first suicide, which I previously mentioned in the context of developing Salomé‘s character and environment. The man runs to the ledge of the courtyard, beholds the moon, and leaps. Cut to a wide, back-lit shot of the figure plunging to nowhere, establishing that the city above the clouds depicted in the art titles and opening credits is the actual physical location that film is taking place in. It’s a genuinely startling moment in the film and Salomé’s most evocative use of creative geography.

The majority of legitimate critical appraisal at the time of Salomé’s release recognize it as an achievement in film art, even highlighting artsiness as a potential selling point. As art cinemas started popping up in the US, Salomé stayed in circulation. Appreciation grew. Legends emerged around its production. And, now one hundred years later, it’s safe to say that Salomé has earned and kept its place as a fixture of the history of film art. As we are lucky enough to have the complete film to watch, assess, reassess, and debate its qualities as a work of cinematic art, I’m positive that conversation on Salomé will continue.

So, if Salomé was appreciated in its time, why did it ruin and bankrupt Nazimova? What was going on in the American film industry at the time? Find out in part two!

“If we have made something fine, something lasting, it is enough. The commercial end of it does not interest me at all. I hate it. This I do know: we must live, and I must live well. I have suffered—enough. Never again shall I suffer. But most of all am I concerned in creating something that will lift us all above this petty level of earthly things. My work is my god. I want to build what I know is fine, what I feel calling for expression. I must be true to my ideals—”

— Nazimova on Salomé quoted in “The Complete Artiste” by Malcolm Oettinger

——— ——— ———

*As of the time of writing, I haven’t been able to track down a complete copy for the campaign book for the film, so I’m relying on fragments, quotes, and second-hand references to its content.

——— ——— ———

☕Appreciate my work? Buy me a coffee! ☕

——— ——— ———

Bibliography/Further Reading

(This isn’t an exhaustive list, but covers what’s most relevant to the essay above!)

Salomé by Oscar Wilde [French/English]

“Herodias” by Gustave Flaubert [English]

Cosplay the Classics: Natacha Rambova

Lost, but Not Forgotten: A Doll’s House (1922)

“Temperament? Certainly, says Nazimova” by Adela Rogers St. Johns in Photoplay, October 1926

“Newspaper Opinions” in The Film Daily, 3 January 1923

“Splendid Production Values But No Kick in Nazimova’s “Salome” in The Film Daily, 7 January 1923

“SALOME” in The Story World, March 1923

“SALOME’ —Class AA” from Screen Opinions, 15 February 1923

“The Complete Artiste” by Malcolm H. Oettinger in Picture-Play Magazine, April 1923

“Famous Salomes” by Willard H. Wright in Motion Picture Classic, October 1922

“Nazimova’s ‘Salome’” by Walter Anthony in Closeup, 5 January 1923

“Alla Nazimova: ‘The Witch of Makeup’” by Robert A. Schanke in Passing Performances: Queer Readings of Leading Players in American Theater History

“Besare tu boca, Iokanaan. Arte y experiencia cinematografica en Salome de Alla Nazimova” by Belén Ruiz Garrido (Wish I had read this at the beginning of my research and writing instead of near the end as it touches upon a few of the same points as my essay! Highly recommended!)

“The Function of the Actor” by Herman Weinberg

“‘Out Salomeing Salome’: Dance, The New Woman, and Fan Magazine Orientalism” by Gaylyn Studlar in Visions of the East: Orientalism in Film

Nazimova: A Biography by Gavin Lambert (Note: I do not recommend this without caveat even though it’s the only monograph biography of Nazimova. Lambert did a commendable amount of research but his presentation of that research is ruined by misrepresentations, factual errors, and a general tendency to make unfounded assumptions about Nazimova’s motivations and personal feelings.)

Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s by Frederick Lewis Allen

Russian Theatre: from the Empire to the Soviets by Mark Slonim

#1920s#1922#1923#Nazimova#alla nazimova#natacha rambova#cosplay#fan art#Salome#Oscar Wilde#film history#independent film#silent cinema#classic cinema#film#american film#queer cinema#women filmmakers#queer#cosplay the classics#queer film#cinema#women directors#classic film#classic movies#silent film#my gifs#silent movies#silent era#history

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

First National Charlie Chaplin offered him one million dollars for 8 two-reel films in 16 months, anything over two-reels First National would pay extra. The 16 months turned into almost 5 years - Chaplin the perfectionist.

"A Dog's LIfe" 1918 (3 reels). "Shoulder Arms" 1918 (3 reels). "Sunnyside" 1919 (3 reels). "A Day's Pleasure" 1919 (2 reels). "The Kid" 1921 (6 reels). "The Idle Class" 1921 (2 reels). "Pay Day" 1922 (2 reels)" & "The Pilgrim" 1923 (4 reels).

Out of this period, would come his first fully realized Masterpiece:

“The Kid” 1921

Chaplin was told he could not mix pathos (drama) with comedy, one would fail, again he proofed them wrong. He created an iconic scene with the roof top rescue of the orphaned boy, one of the greatest in cinema history in my opinion.

#charlie chaplin#first national#1918-1923#“a dog's life”#“shoulder arms”#1918#“sunnyside”#“a day's pleasure”#1919#“the kid”#“the idle class”#1921#“pay day”#1922#“the pilgrim”#1923

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

View of a 1922-1923 Packard front quarter view, male standing at front, top raised, storm curtains in place. Inscribed on photo back: "Packard 3-35, third series twin-six, 12-cylinder, 90-horsepower, 136-inch wheelbase, 7-person touring car (body type #225), note Michigan license plate #14-354, double bar front bumper, disc wheels, spot light fitted through lower windshield panel, Detroit jitney and driver, served Woodward Ave. & 8 Mile Road."

Packard Collection

National Automotive History Collection, Detroit Public Library

#detroit#packard#1922#1923#1920s#jitney#michigan#cars#automobiles#vintage#vintage automobiles#vintage cars#detroit history#detroit public library

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day Dreams (1922), Three Ages (1923), Convict 13 (1920)

She loves me, she loves me not... // They'll catch me, they'll catch me not...

#buster keaton#day dreams#three ages#convict 13#1920#1922#1923#1920s#silent film#silent comedy#silent cinema#silent era#1920s cinema#1920s hollywood#film#cinema#pre code#pre code hollywood#comedy#buster edit#black and white#vintage hollywood#slapstick#gifs#old hollywood

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

my overthinking ass will have me saying things like "will my teacher hate me for writing about the 1921 famine in the civil war activity because it might not be considered part of the civil war?" when absolutely no fucking body can agree on proper start and end dates for the russian civil war

#diya's musings#like it is open for interpretation!!#and it's not even an assessed task it's not that deep#some say it ended in 1920 others say 1922 or 1923

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

BEAUTY EVOLUTION OF BARBARA LA MARR

(1896-1926)

1910s barbara (left) and her sister violet

1920 she starts acting and becomes a star

1921 her eyes are so sad but beautiful

1922 this dark outfit is fantastic

winter 1922 smiling with her son marvin

1923 cute with curly hair

around 1924 again with marvin both adorable

1924 glamorous with lots of makeup

1925 in one of her last movies

around 1926 barbara on her deathbed

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Rare Paleomedia Find

youtube

This is an important piece of lost paleomedia for several reasons. First of all, it's the source of all the "Old Timey Fossil Prospecting" footage used in dinosaur documentaries from the 1980s onwards. That's a pretty important find in and of itself.

For a while, I thought it had a little extra footage from the much edited down and lost from Ghost of Slumber Mountain - but the footage freely available online is just in such muddy quality that it's hard to see (the Blu Ray of the 1925 Lost world restoration has a much cleaner version).

Still, this is an important piece of Paleomedia history, and it doesn't even have an IMDB page! As near as I can tell, its' from 1922 (according to online sources that share it), and the timing checks out (it needs to be at least older than 1918 to have footage from Along the Moonbeam Trail).

#Dinosaurs#Dinosaur#Paleomedia#Paleoblr#Monsters of the Past#1922#1923#Ghost of Slumber Mountain#Willis O'brien#Along the Moonbeam Trail#Stop Motion#Stop Motion Animation#Ray Harryhausen#Youtube

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dadda Cooke

1922-1923

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ending My Articles On A Good Note

A short article regarding how I usually choose to end my articles written on this website.

-

#blog #blogging #malaysia #writing #article

Click here for more articles & daily dose.

Sometime ago, I wrote about “The Small Change I Hope My Blog Would Make“, whereby I mentioned that with every article written and uploaded on this website would spread some form of comfort and positivity, especially within the community of junior doctors.

Perhaps I’m just simply being optimistic. I have to. That keeps me going, even on difficult days…

#article#Articles#Blog#blogging#dailyprompt#dailyprompt-1863#dailyprompt-1907#dailyprompt-1912#dailyprompt-1913#dailyprompt-1914#dailyprompt-1916#dailyprompt-1917#dailyprompt-1918#dailyprompt-1919#dailyprompt-1921#dailyprompt-1922#dailyprompt-1923#dailyprompt-1924#dailyprompt-1926#dailyprompt-1931#dailyprompt-1933#dailyprompt-1935#dailyprompt-1984#dailyprompt-1995#dailyprompt-2005#dailyprompt-2008#dailyprompt-2019#dailyprompt-2024#dailyprompt-2026#dailyprompt-2027

0 notes

Text

The Civic Guard Mutiny of 1922

After the ratification of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, Britain withdrew its soldiers from Ireland except for a contingent in Dublin. This contingent was under the command of General Cecil Frederick Nevil Macready. Not only did the withdrawal create a barracks race between the Free State and Anti-Treaty forces, but it also created a police crisis in the midst of an approaching civil war. Obviously, the…

#Civic Guard Mutiny#Garda Síochána#Ireland#Irish Civil War 1922-1923#michael staines#patrick brennan

0 notes

Text

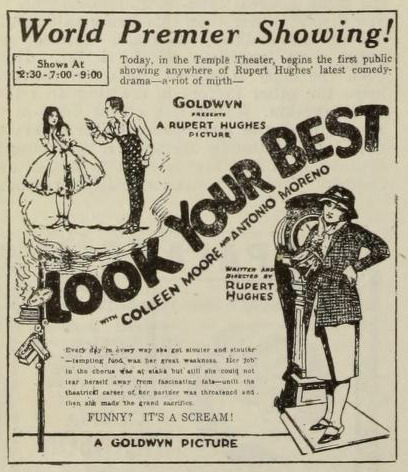

Lost, but Not Forgotten: Look Your Best (1923)

[alternate title: The Bitterness of Sweets]

Direction: Rupert Hughes

Scenario: Rupert Hughes

Camera: Norbert Brodin

Choreography: Ruth St. Denis

Studio: Goldwyn

Performers: Colleen Moore, Antonio Moreno, Earl Metcalfe, Martha Mattox, William Orlamond, Orpha Alba, Francis McDonald, Eleanor Boardman (in a bit role)

Premiere: 18 February 1923, Temple Theatre, Detroit, MI

Status: presumed entirely lost

CW: Dieting / Weight Loss

Synopsis (synthesized from magazine summaries of the plot):

On the streets of New York’s Little Italy, Perla Quaranta* (Moore) dances to the music of her father’s (Orlamond) barrel organ. Unfortunately, Perla’s mother (Alba) has a tendency to grab whatever is at hand for use as a projectile in the midst of arguments with Perla’s father. After one particularly raucous fight, her parents are arrested and sentenced to 30 days. Fortunately for Perla, the owner of a dance troupe, Carlo Bruni (Moreno) scouted her dancing on the streets and hires her to replace a recently fired dancer. The previous girl in Bruni’s “Butterfly Act” was let go after gaining too much weight to do the wirework demanded by the routine. Perla’s privation-induced petiteness is desirable for the role.

Bruni’s struggle with his weight has also apparently gotten in the way of his own work as a dancer. Perla takes well to the role and is a success in the act, which features a number of chorus girls dressed as butterflies flitting across the stage by wire. The stagehand, Krug (Metcalfe), takes a liking to Perla and takes her out regularly as the troupe goes on tour. The now gainfully-employed and avidly-courted Perla has access to all the sweets her heart desires and, in a repeat of her predecessor’s difficulties, she begins to put on pounds. Krug makes an advance on Perla, which she rebuffs. In his bitterness, Krug files Perla’s wires, assuming Bruni will blame the broken wires on her weight and fire her. During the next performance, Perla plummets to the stage and is injured.

Bruni suspects Krug of tampering with the wires, and thrashes him. Bruni is arrested and also given 30 days. While Perla recovers in the hospital, another suitor appears in the form of a baker, Cabotto (McDonald), who buoys her spirits by describing all the different delectations he serves. Meanwhile, behind bars, Bruni envisions a new ballet for the troupe with Perla in a starring role.

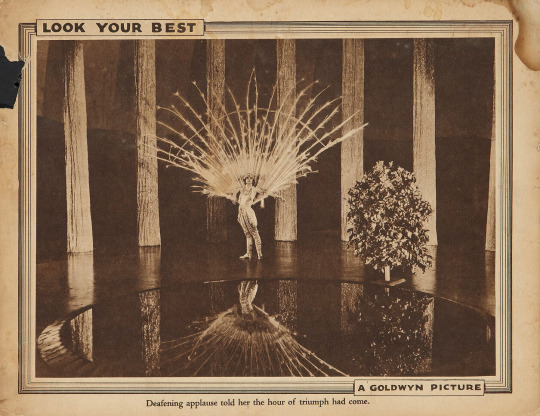

When Bruni is freed and Perla is recovered, they reunite and commit to dieting and to each other, via marriage. The new act depicts Perla as a white peacock killed by the hunter, played by Bruni, and mourned by an array of forest nymphs.

(At some point before the final dance number, Perla is reunited with her parents, but, from the synopses, I’m not sure of the order of events.)

* or Quaranti or Moroni based on various reviews

As a side note that I cover more in the annotations below: this plot doesn’t make much sense without a heavy dose of satire, right? The reviews didn’t leave me with a clear idea on whether the film lampoons diet culture or not and, unfortunately for us, unless somebody (maybe some sharp Michigander) makes a lucky discovery, we can’t find out for ourselves!

Transcribed sources & annotations below:

Motion Picture News, April 1922

Ruth St. Denis to Supervise Dance Scenes

The noted dancer, Ruth St. Denis, has been engaged by Goldwyn to supervise the dance scenes in Rupert Hughes’ new comedy, “The Bitterness of Sweets,” which he is himself directing.

The beautiful peacock ballet in this film will form the climax of the picture. The featured players, Colleen Moore and Antonio Moreno, are both busy practicing for this dance. Active work on the photography for “The Bitterness of Sweets” will soon be begun by Mr. Hughes. In the cast are William Orlamond, Orpha Alba, Earl Metcalfe and Martha Mattox.

—

Note: “The Bitterness of Sweets” was the working title of “Look Your Best.”

I hadn’t heard of Ruth St. Denis before now, but seeing what an important role she had in the creation of Modern Dance in America—and that she was a teacher of both Martha Graham and Louise Brooks—it’s an insult to injury that this film appears to be lost. I’m not even sure how many films St. Denis worked on! Many of the reviews below cite the dance numbers as a true highlight of the film too.

Exhibitor’s Herald, 8 April 1922

Rupert Hughes Personally Directs Filming of Story

Rupert Hughes’ new Goldwyn photoplay “The Bitterness of Sweets,” is a story of Italian-Americans, instead of the Irish-Americans that he has depicted so frequently in the past. The author has assumed the directorial reins in the making of his own picture.

Colleen Moore is playing the role of an Italian dancer with a craving for sweets, which tend to make her too fat for the dancing art. Antonio Moreno has been signed to Goldwyn to play opposite Miss Moore in this comedy-drama.

Moving Picture World, 13 May 1922

SINCE Rupert Hughes has taken to directing his own pictures at the Goldwyn studios in Culver City he has been swamped by visitors. They like to hear him spouting epigrams through his megaphone. Colleen Moore, who is now being directed by him in “The Bitterness of Sweets,“ already has jotted down the following bits:

You can’t use imitation silk before the motion picture camera. The lens is even quicker to detect imitation emotion.

Horace said: “He who would make others weep, must first have wept himself.” Every motion picture director should have that on his wall.

Ever since I was six years old people have been prophesying that I was going to kill myself with overwork. All the prophets are now dead.

We could make some very fine motion pictures if we didn’t have to bother with cameras and lights.

The censors are going to stop crime by censoring the films. Why don’t they put an end to diseases by burning the medical books which describe them?

When an actor loses control of himself he loses control of his audience.

—

Note: the timeline for the production to release of this movie is really something. They commenced filming somewhere around the end of April/early May 1922, but it wasn’t released until late February of 1923.

Motion Picture Magazine, June 1922

On the Camera Coast

[excerpt]

Things are stirring down at Goldwyn’s once more, with Rupert Hughes at work on his own story, “The Bitterness of Sweets,” Colleen Moore. Colleen made such an impression in two of the Hughes pictures that she will be retained as the featured player in all of his productions into which she can possibly be fitted.

—

Note: This doesn’t appear to have come to fruition?

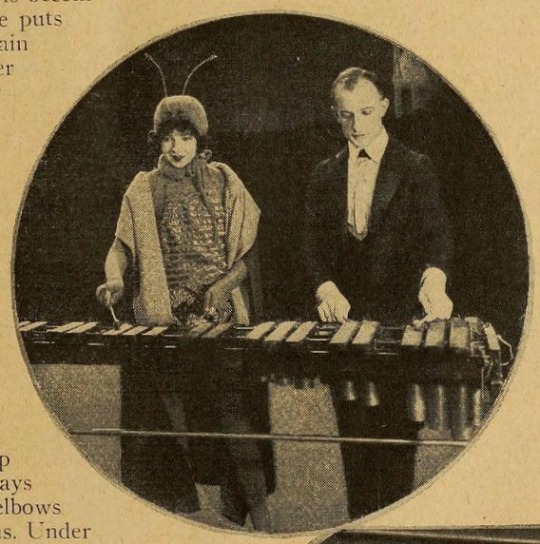

Motion Picture Magazine, September 1922

…There were long waits between the scenes of the new Rupert Hughes production “The Bitterness of Sweets,” but Colleen Moore didn’t mind them. She provided musical relaxation…

Exhibitor’s Trade Review, October 1922

Colleen Moore Sets New Record

Will Be Featured by Five Different Distributing Companies Within Space of Two Months

A record unique in the annals of the motion picture business is being set this fall by Colleen Moore, beautiful and talented young star. Exhibitors who stand by one or another distributing company and who have therefore not had the opportunity to play any of these pictures in which Miss Moore has been featured will note with interest that no less than five distributing companies will offer productions in which she is featured during the coming fall months.

First National will shortly present “Slippy McGee,” the Oliver Morosco production of Marie Conway Oemler’s well known story, in which Miss Moore plays the leading feminine role.

Goldwyn will soon release two pictures in which Miss Moore will be featured. The first will be Rupert Hughes’ production of “The Bitterness of Sweets,” which was personally directed by the author. Tony Moreno plays opposite Miss Moore in this production. The second Goldwyn feature will be “Broken Chains,” the widely advertised $10,000 prize story which was transferred to the screen under the capable direction of Allen Holubar.

Hodkinson has already delivered to its exchanges the prints of “Affinities,” a picturization of the Mary Roberts Rhinehart story of the same name. This is a Ward Lascelle production in which Miss Moore is starred.

Universal announces that Miss Moore will soon be seen in the featured feminine role in “Forsaking All Others,” a drama which has just been completed under the direction of Emile Chautard. It will be released as a Jewel special.

Rounding out the quintet, Vitagraph is now nearing completion of a picturization of the famous old stage success “The Ninety and Nine,” with Miss Moore in the featured role and directed by Dave Smith. This production will also be a special release.

—

Note: Slippy McGee (premiered June 1923, status unknown) , Broken Chains (premiered December 1922, extant), Affinities (premiered October 1922, status unknown), Forsaking All Others (premiered December 1922, status unknown), The Ninety and Nine (premiered December 1922, only 10 minutes of the film survive (available on Undercrank Productions’ Accidentally Preserved Vol. 4))

This item implies that LYB was intended for release in the fall/winter of 1922, though an exact date isn’t given.

Moving Picture World, October 1922

Moreno Signs to Act for Paramount

Antonio Moreno has signed with Paramount. This announcement was made during the past week in Hollywood where the popular “Tony” already has started work as leading man with Gloria Swanson in Sam Wood’s new production, “My American Wife,” which Monte M. Katterjohn has adapted from an original screen story by Hector Turnbull.

Moreno is admittedly one of the handsomest and most able actors on the screen. Recently he has been featured by Goldwyn and will soon be seen in two of that company’s new productions, “The Bitterness of Sweets,” a Rupert Hughes production, and “Passions of the Sea.”

The new Paramount picture in which Moreno will play opposite Miss Swanson is described as intensely romantic, the locale being Argentina. Moreno’s role is that of a handsome young aristocrat and politician, descendant of one of the old Spanish conquistadores, who falls in love with a beautiful American girl from Kentucky (Miss Swanson) whose horse out-races the valued track champion of the Latin nobleman.

—

Note: My American Wife (premiered February 1923, status unknown), Passions of the Sea (premiered in February 1923 as Lost and Found on a South Sea Island, extant)

Motion Picture News, February 1923

Pre-release Reviews of Features

“Look Your Best ”

Goldwyn—Six Reels

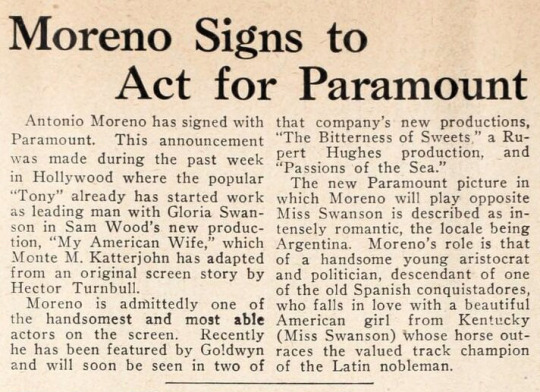

(Reviewed by Charles Larkin)

TO EAT, to grow fat, to spoil one’s career. To starve, to keep thin, to become a great artiste. That is the choice given Perla Quaranta, a little Italian girl portrayed by Colleen Moore, who is one day noticed dancing in the streets by Carlo Bruni, manager of a small theatrical troupe, and who is given the place of the chorus lady who has fallen to the temptation of too many sweets, with the result that the perfect 36 has developed into an imperfect 40 or so. Perla is a success in the act but as she goes from town to town, accepting invitations from Krug, a stage hand, to dine, she also begins to take on weight. Krug, maddened at her coldness, when he makes advances, weakens the wire that holds Perla aloft in a butterfly stunt and she falls to the stage. Krug thought he could tell the folks Perla’s avoirdupois was to blame. Bruni, however, knocks Krug for a goal and gets thirty days for his gallantry. However, thirty days pass soon in some jails, and Bruni is soon out and starting a new ballet with Perla.

And so it goes. It isn’t much of a picture and there is a fight between Perla’s mother and father which takes up much footage and could be eliminated much to the improvement of the story. In fact, the dropping of these two characters throughout would not be missed in the least. To see a boisterous hurdy gurdy grinder jump from jail into a theatre box in a dress suit is not being done these days. There is a very artistic ballet scene toward the end of this picture.

This is not the best thing Rupert Hughes has written and adapted for the screen. Neither is it his best directed picture. Of course, one can’t expect any company to continue releasing masterpieces all the time. We can’t have a “Christian” every day. There have got to be some program pictures once in a while. This is one. It will serve its purpose and is suitable for second-class downtown houses, and there may be many who may find much humor in its fat and thin theme—especially those who are fighting either evil.

The Cast

Perla Quaranta…Colleen Moore

Carlo Bruni…Antonio Moreno

Pietro…William Orlamond

Nella…Orpha Alba

Krug…Earl Metcalfe

Mrs. Blitz…Martha Mattox

Alberto Cabotto…Francis McDonald

By Rupert Hughes. Directed by Rupert Hughes. Scenario by Rupert Hughes. Photographed by Norbert Brodin.

The Story—Deals with the horror in which some folks hold plain good old fat. A chorus girl having attained this terrible state, is fired and Perla, a daughter of Little Italy, is given her place in Bruni’s “Butterfly Act.” Perla made good and went on the road with the show. She also went out to dine with one Krug and began to put on flesh. Krug, a disappointed suitor, filed one of the wires which held Perla aloft in the butterfly stuff. During the act she crashed to the stage. Bruni beats up Krug and gets 30 days. Emerging from jail he starts a new ballet, engages Perla and the two rise to fame.

Classification—One of Rupert Hughes’ problem plays—the problem of keeping thin.

Production Highlights—Colleen Moore’s characterization of the role of the little Italian girl. The crashing of Perla to the stage floor as a result of the villain weakening the wire which holds her.

Exploitation Angles—The title. The eat and grow thin or fat as you will theme offers a chance to tie up with the health department, Y. W. C. A. women’s walking clubs, etc.

—

Note: “Deals with the horror in which some folks hold plain good old fat.” There’s only so much I can assume about the movie’s treatment of weight gain and dieting, as it is lost, but from all the synopses I read, I gotta say as a plot device it doesn’t seem to make much sense? Like, obviously in the performing arts, the expectation to stay at one precise size is stricter than in other fields, but it seems like there is no real logic at play here? I’m glad this reviewer points out that it comes off as Rupert Hughes just hating fat people. Another reviewer mentions a noteworthy lack of satire in the film, and, from the details in the synopses, it seems like this plot would only really make sense if it were a satire or critique on diet culture.

Exhibitor’s Trade Review, February 1923

Look Your Best

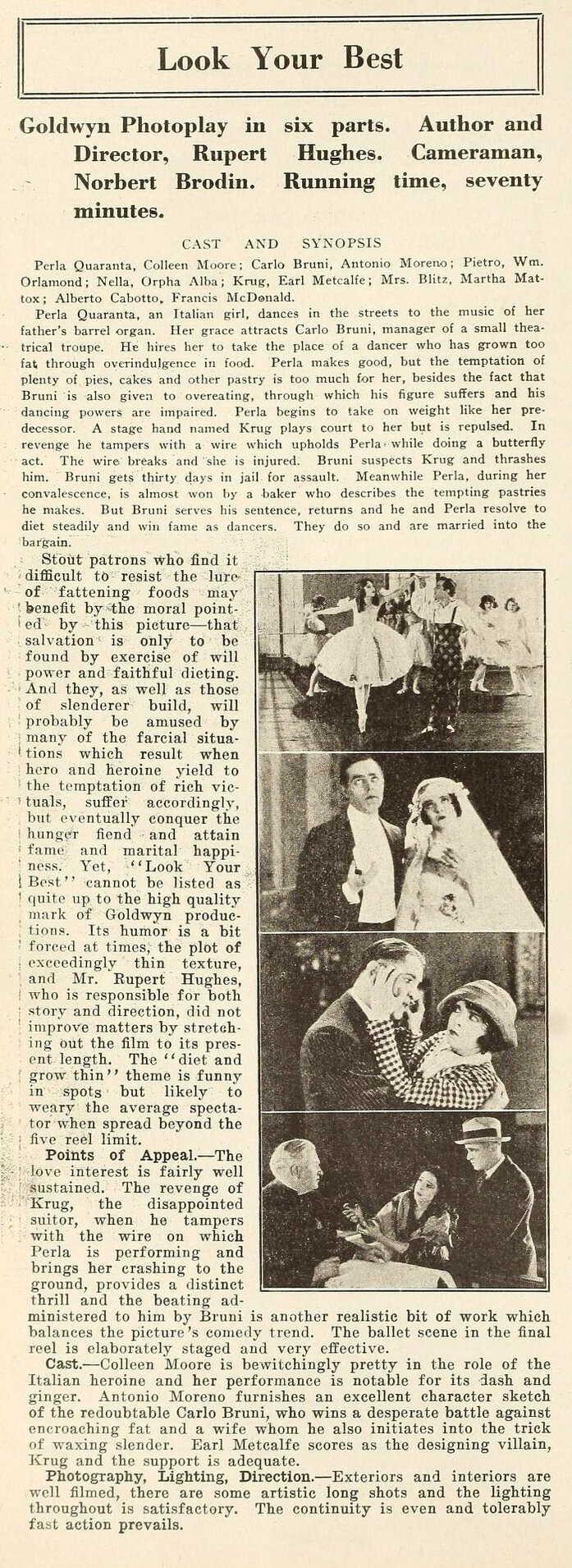

Goldwyn Photoplay in six parts. Author and Director, Rupert Hughes. Cameraman, Norbert Brodin. Running time, seventy minutes.

CAST AND SYNOPSIS

Perla Quaranta, Colleen Moore; Carlo Bruni, Antonio Moreno; Pietro, Wm. Orlamond; Nella, Orpha Alba; Krug, Earl Metcalfe; Mrs. Blitz, Martha Mattox; Alberto Cabotto, Francis McDonald.

Perla Quaranta, an Italian girl, dances in the streets to the music of her father’s barrel organ. Her grace attracts Carlo Bruni, manager of a small theatrical troupe. He hires her to take the place of a dancer who has grown too fat through overindulgence in food. Perla makes good, but the temptation of plenty of pies, cakes and other pastry is too much for her, besides the fact that Bruni is also given to overeating, through which his figure suffers and his dancing powers are impaired. Perla begins to take on weight like her predecessor. A stage hand named Krug plays court to her but is repulsed. In revenge he tampers with a wire which upholds Perla while doing a butterfly act. The wire breaks and she is injured. Bruni suspects Krug and thrashes him. Bruni gets thirty days in jail for assault. Meanwhile Perla, during her convalescence, is almost won by a baker who describes the tempting pastries he makes. But Bruni serves his sentence, returns and he and Perla resolve to diet steadily and win fame as dancers. They do so and are married into the bargain.

Stout patrons who find it difficult to resist the lure of fattening foods may benefit by the moral pointed by this picture—that salvation is only to be found by exercise of will power and faithful dieting. And they, as well as those of slenderer build, will probably be amused by many of the farcical situations which result when hero and heroine yield to the temptation of rich victuals, suffer accordingly, but eventually conquer the hunger fiend and attain fame and marital happiness. Yet, “Look Your Best” cannot be listed as quite up to the high quality mark of Goldwyn productions. Its humor is a bit forced at times, the plot of exceedingly thin texture, and Mr. Rupert Hughes, who is responsible for both story and direction, did not improve matters by stretching out the film to its present length. The “diet and grow thin” theme is funny in spots but likely to weary the average spectator when spread beyond the five reel limit.

Points of Appeal.—The love interest is fairly well sustained. The revenge of Krug, the disappointed suitor, when he tampers with the wire on which Perla is performing and brings her crashing to the ground, provides a distinct thrill and the beating administered to him by Bruni is another realistic bit of work which balances the picture’s comedy trend. The ballet scene in the final reel is elaborately staged and very effective.

Cast.—Colleen Moore is bewitchingly pretty in the role of the Italian heroine and her performance is notable for its dash and ginger. Antonio Moreno furnishes an excellent character sketch of the redoubtable Carlo Bruni, who wins a desperate battle against encroaching fat and a wife whom he also initiates into the trick of waxing slender. Earl Metcalfe scores as the designing villain, Krug and the support is adequate.

Photography, Lighting, Direction.—Exteriors and interiors are well filmed, there are some artistic long shots and the lighting throughout is satisfactory. The continuity is even and tolerably fast action prevails.

Motion Picture Magazine, March 1923

Comments on Numerous Productions

LOOK YOUR BEST — GOLDWYN

Rupert Hughes gets off on a different tack in this, his latest expression. He makes a plea to be on the look-out for adipose tissue as a destroyer of beauty. And he argues his point thru a weirdly melodramatic story of a chorus girl who develops obesity and is discharged as a result. A slender girl is taken on and proves a sensation. Comes then a bit of Italian jealousy when a disappointed lover files the wires in the ballet number, causing the little “butterfly” to crash to the stage. Mr. Hughes’s satiric vein is missing here. In fact you wouldn’t recognize his style here at all. It’s breath-taking, now and then, but many of the scenes are clumsily executed and the characters are not deftly drawn. Colleen Moore succeeds in being genuine, as usual, in her portrayal of the ballet girl. And Tony Moreno is a satisfactory lover—of the hot Italian school.

---

Note: Interesting point here that there is a lack of “Hughes’ satiric vein.” I haven’t seen much of his work as of yet, so I don’t know what sort of satire would be typical of Hughes’ work. However the plot details laid out across various reviews and synopses don’t just strain credibility they tear it to shreds, UNLESS the whole thing was a satire on diet culture, but as far as I can tell, it’s just straight-up fatphobia. A shame, for sure, because this sort of story told as a lampooning of diet culture honestly sounds pretty darn entertaining.

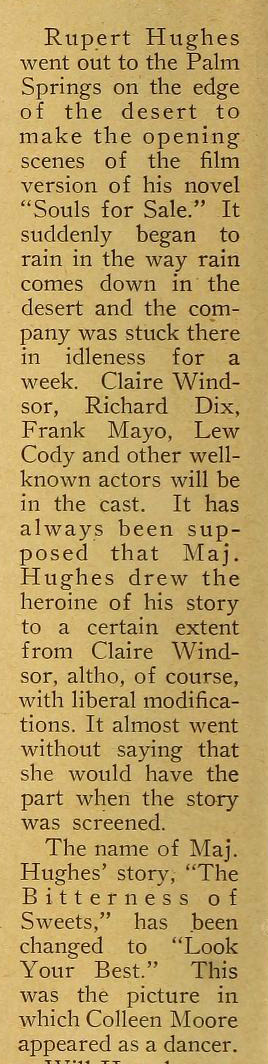

Motion Picture Magazine, March 1923

Rupert Hughes went out to the Palm Springs on the edge of the desert to make the opening scenes of the film version of his novel “Souls for Sale.” It suddenly began to rain in the way rain comes down in the desert and the company was stuck there in idleness for a week. Claire Windsor, Richard Dix, Frank Mayo, Lew Cody and other well known actors will be in the cast. It has always been supposed that Maj. Hughes drew the heroine of his story to a certain extent from Claire Windsor, altho, of course, with liberal modifications. It almost went without saying that she would have the part when the story was screened.

The name of Maj, Hughes’ story, “The Bitterness of Sweets,” has been changed to “Look Your Best.” This was the picture in which Colleen Moore appeared as a dancer.

—

Note: Considering the extended timeline between the production and release of Look Your Best, the production of Souls for Sale (premiered March 1923, extant) commenced directly after LYB wrapped. So, Hughes’ second and third feature for Goldwyn premiered within a month of each other, with Souls for Sale being a larger production and more heavily marketed. I’m wondering if holding off on the release of Look Your Best was due to a lack of faith in the final product and a desire not to prematurely tarnish the rep of a writer/director that Goldwyn had just signed on for a lot of pictures? That is, releasing it close to Souls for Sale seems like a smart call because Souls for Sale’s quality and higher box-office potential would likely minimize any doubts about Hughes’ abilities that might arise if his second film for Goldwyn was as underwhelming as reviewers and exhibitors portray it. Alternatively or additionally, maybe the studio deemed LYB a “programmer” after production wrapped and was simply waiting for a better time on their release schedule.

The Film Daily, 30 March 1923

Putting It Over

Here is how a brother exhibitor put his show over. Send along your ideas. Let the other fellow know how you cleaned up.

Fashion Pageant Staged

Toledo—Eddie Carrier, Goldwynner put over “Look Your Best” at the Pantheon exploitation campaign.

The outstanding feature was the presentation of a fashion pageant, which was staged in co-operation with the Thompson Hudson Co. department store. A number of manikins were brought to Toledo by Carrier. A runway was constructed out into the audience along which the beauties promenaded adorned with the seasons latest fads and fancies. The runway had special illumination and the spectacle was said the most elaborate ever staged.

—

Note: There are a number of news items about exploitation schemes for the film that tie in with other local businesses, but, humorously, the tie-ins are with department stores and have to do with fashion and cosmetics, when that seemingly has nothing to do with a movie about vaudeville performers and dieting!

Camera, 30 March 1923

THE SILENT TREND

Composite of Views, Previews, and Reviews of Motion Pictures.

“Look Your Best” and we did. The result: we saw a pretty fine Rupert Hughes photoplay, quite typical of that author’s best work for the screen. Many critics complain that this one is not up to the usual Hughes standard. It may not be, but, just the same, it is highly amusing and away above the average of other films of its class. The cast is especially attractive, Colleen Moore and Antonio Moreno dividing high honors with Earl Metcalf and Martha Mattox contributing excellent characterizations. The direction is undoubtedly devoid of any of the brilliance of finesse and could be improved upon easily, but the main idea of the story is registered successfully enough to make anyone remember it with pleasure. And, that’s a commendable lot for a motion picture to accomplish.

Motion Picture News, April 1923

Elaborate Style Show Put Over with “Look Your Best”

Toledo, Ohio.—The management of the Pantheon theatre, in conjunction with Goldwynner Eddie Carrier, put on an elaborate exploitation campaign on “Look Your Best,” the outstanding feature of which was a fashion pageant staged in co-operation with the Thompson-Hudson Company, a leading department store.

A bevy of beautiful mannequins was assembled, and a runway was built far out into the audience, on which they promenaded with the latest fashion creations. Special lighting and scenic effects were used and a musical score was provided for the occasion. The department store co-operated with a double-page ad, seven full window displays and 2,500 letters to its customers.

Moving Picture World, April 1923

“Look Your Best”

Rupert Hughes Has Created a Clever Comedy Drama Satire on Dieting

Reviewed by Beatrice Barrett

A clever commingling of comedy, pathos and drama, with a thrill thrown in now and then and a subtle satire on dieting running all through is “Look Your Best,” a Goldwyn release.

It is the sort of light entertainment picture lovers like when they are just out for a good time and relaxation.

With the much discussed question of dieting as a background there will be many in the audience who will appreciate heartily the efforts of the people to diet and forego all the pleasures of eating, and the many times they yield to temptation.

An appealing strain of pathos is introduced in Perla, the Italian girl whose life is almost all work and no food, and her childish pleasure in her first nice clothes. Colleen Moore does well this wistful role. There is always a fascination about life back of the curtain and there are many scenes here of the rehearsals and scenes in the dressing rooms that will attract.

Very beautiful are the scenes of the Butterfly Girls with great gauze wings executing their dance and then suspended on wires flying through the air. The stage sets and the dance which Antonio Moreno and Colleen Moore do at the end of the picture is also very artistic and gives an air of a big production to what at times seems to be simply a comedy.

Rupert Hughes worked up through many laughs to the big thrill of the cut wire and has handled very well these scenes with the girl flying through the air coming right toward the camera—and all the while the audience knows the wire is going to break—and it does and there is a fall that will give them a shudder.

The plot is a gossamer one, and simply a thread which lightly holds together the events of the story—but in a picture of this character you don’t expect much plot. The audience will be chuckling and enjoying each new incident as it comes along.

Cast

Perla Moroni…Colleen Moore

Carlo Bruni…Antonio Moreno

Pietri…William Orlamond

Nella…Orpha Alba

Krug…Earl Metcalf

Mrs. Blitz…Martha Maddox

Alberta Cobatto…Francis MacDonald

Written and directed by Rupert Hughes.

6 reels.

Story

Perla, a half starved Italian girl, is engaged by Bruni to be one of his butterfly dancers because she is so thin. Krug, the wireman, becomes infatuated with Perla. She begins to get fat, and when she tires of Krug’s attentions he files the wire on which she hangs as a butterfly so Bruni will think she is too fat for the part and discharge her. Bruni used to be a beautiful dancer but through love of food grew too fat and could no longer dance. He and Perla both start to diet. He composes a beautiful dance for them and they are a great success. The story ends with their wedding—and the two still dieting.

—

Note: Now, this reviewer thinks the film is a satire of dieting?

Exhibitor’s Herald, 7 April 1923

COLLEEN MOORE IN

LOOK YOUR BEST

(GOLDWYN)

A cheerful little story of an Italian girl who becomes an actress and then has a hard time keeping her job because of overeating. An interesting picture of backstage life, and although not one of Rupert Hughes greatest plays, is quite satisfying. Author: Rupert Hughes; Continuity: Rupert Hughes; Director: Rupert Hughes. Length six reels.

There is just a little over an hour’s pleasant diversion in this latest Rupert Hughes-Goldwyn production. It is a quaint mixture of pathos, humor and drama. The humor borders on the slapstick, while the melodrama is the good old-fashioned “s-death” kind. However, there is the ever appealing Colleen Moore in it, as the interesting little toe dancer, and Antonio Moreno as a ballet master. Add to these William Orlamond, as Pietro; Orpha Alba, as Bella, his wife; Earl Matcalfe, as Krug, the villain; Martha Mattox, ad Mrs. Blitz; and Francis McDonald, as Cabotto, a suitor for Perla’s hand, and you have a cast capable of good things.

At the State-Lake theater, Chicago, where the picture followed the trained seals, it got a few laughs and held the attention of a vaudeville-loving audience. And you’ll certainly enjoy Colleen Moore more and more.

The story concerns Perla, a little New York girl of Italian parentage who goes into Bruni’s butterfly dance act in vaudeville and finds she must deny herself the sweets she loves in order to remain slender. The man who manipulates the wires, failing to win her love, plots to get her discharged for putting on too much flesh. He cuts the wire supporting her, but Bruni discovers his treachery and engages him in a fight, which lands both in jail, but on Bruni’s release Perla is waiting to reward him with her hand.

Screen Opinions, June 1923

“LOOK YOUR BEST”— [Class B] 65%

(Especially prepared for screen)

Story:—Romance of Little Italy, a Girl and a Theatrical Manager

VALUE

Photography—Very good—Norbert Brodin.

TYPE OF PICTURE—Entertaining.

Moral Standard—Average.

Story—Good—Comedy-drama—Family.

Stars—Good—Colleen Moore and Antonio Moreno.

Author—Good—Rupert Hughes.

Direction—Good—Rupert Hughes.

Adaptation—Good—Rupert Hughes.

Technique—Good.

Spiritual Influence—Neutral.

CAST

Perla Quaranti…Colleen Moore

Carlo Bruni…Antonio Moreno

Pietro…William Orlamond

Nella…Orpha Alba

Krug…Earl Metcalfe

Mrs. Blitz…Martha Mattox

Alberto Cabotto…Francis McDonald

June 1 to 15, 1923.

Producer—Goldwyn

Footage—6,000 ft.

Distributor—Goldwyn

Our Opinion

MORAL O’THE PICTURE—If You Would Look Well, Mind Your Diet.

Not Particularly Artistic, but Makes Good Entertainment—Stars Do Well

Scenes in Little Italy, in which an Italian organ grinder and his wife are forced to serve a thirty-day sentence in jail following a knife and china shower, are fraught with comedy, and so also is the initiation of Perla, the pretty daughter, into the stage technique of playing butterfly and being hoisted on a wire to flutter her butterfly wings. Colleen Moore is charming in the role of Perla, and one of the notably good performances of the picture is done by Orpha Alba, who plays the role of Nella Quaranti, Perla’s mother, who, between laughter and tears, chastises her husband, Pietro, with the first article that comes to hand, no matter what the substance is, and then makes parting at the jail “such sweet sorrow.” William Orlamond is the type for Pietro, and Antonio Moreno, as Bruni, whose theatrical grace was spoiled by too much eating, is also very good. Earl Metcalfe, as Krug, elected to serve as Perla’s wire hoister, in love with her and reproachful when he failed to obtain kisses in return for the food that made Perla “not as thin as she used to was,” is all that the role requires—he does well. Francis McDonald is the baker joy and jealous lover, and looks and acts the part. The picture contains some attractive stage scenes with the butterfly girls flitting rapidly past the camera, and there is also an elaborately staged classic dance, supposed to take place in the greenwood, in which Colleen Moore is dressed as a white peacock, which is slain by the hunter, Antonio Moreno, and mourned by the wood nymphs. This is really a very enjoyable feature.

STORY OF THE PLAY

Perla Quaranti, a street dancer, finds herself alone when her father and mother are sentenced to thirty days in jail for fighting. She is offered a position by Carlo Bruni, an Italian theatrical manager, whose specialty is a group of butterfly girls. Perla, filling the place of a girl who got too stout to hoist, grasps good fortune by the neck and eats herself stout also on the bounty of one Krug, a wirehoister. Krug plays her false when he realizes that she loves Bruni instead of himself, and takes revenge by cutting the wire so that during the whirl of butterflies Perla falls to the stage and is injured. The story closes happily with Perla and her parents reunited, and Bruni her prospective husband.

PROGRAM COPY—”Look Your Best”—Colleen Moore and Antonio Moreno

Perla Quaranti’s butterfly days ended with a bang when a jealous lover took revenge for lack of kisses. Don’t miss seeing Colleen Moore, Antonio Moreno and an excellent cast in “Look Your Best,” one of the funniest and most original of recent comedies.

—

Note: This is the only review that adds detail about Perla’s parents. Another reviewer complained that the bits with her parents were wholly superfluous. Other reviewers barely mention that they are even in the film!

Moving Picture World, 9 June 1923

Sells First Showing on the Type Argument

The Temple Theatre, Detroit, does not believe in too much splash, even for a world premier, and gets along very nicely with 100 by 3 for Look Your Best, using two cuts and six lines of snappy stuff about the nature of the play to back up the illustrations. Apparently these illustrations are from the plan book, and they have no strong illustrative value, but the upper one suggests the stage story, which this is, and the lower the growing weight of Colleen Moore, which is the essence of the plot. The selling value lies chiefly in the talk, and here this talk is a quiet little chat about the play with no particular stress, just an intimate tip-off on the nature of the play which is more convincing than a many-adjectived oration could possibly be. It is so good that it might have been put into larger type, even at the cost of one of the cuts. And make a note now that Look Your Best is going to make a wonderful peg for hook-up pages and style shows. Combine the two of them by starting early enough to get your plans all properly laid. There are a lot of similar co-operative angles, but these will be the best bets. -P. T. A.-

Poster blurb: Every day in every way she gets stouter and stouter—tempting food was her great weakness. Her job in the chorus was at stake but still she could not tear herself away fascinating fats—until the theatrical career of her partner was threatened and then, she made the grand sacrifice.

FUNNY? IT’S A SCREAM!

—

Note: photo of the interior of the now demolished Temple Theatre, a popular vaudeville venue.

---

Exhibitor’s Trade Review, July 1923

SLOGAN BASIS OF MERCHANT TIE-UP

Madison, Wis.—A merchant tie-up on a “Look Your Best” Week was put across by Dr. Wm. E. Beecroft, manager of the Parkway Theatre, and Goldwynner W.D. Nealand, in connection with the screening of “Look Your Best.” Art Kniseley, advertising manager of the Burdick & Murray Department Store, went in heavily with the theatre management on this “Look Your Best” week.

He gave the picture a splendid window display, using the slogan “Look Your Best” as a sales aid for their clothing, millinery, hosiery and toilet articles. In addition to the window display, Mr. Kniseley ran a sixty-eight inch advertisement in both the State Journal and the Capitol Times, tieing up with “Look Your Best.”

---

Moving Picture World, September 1923

Consensus of Published Reviews

Look Your Best

(Colleen Moore—Goldwyn—6 reels)

M. P. W.—A clever commingling of comedy, pathos and drama, with a thrill thrown in now and then and a subtle satire on dieting.

E. H.—Is a cheerful little story of backstage life. It was written and directed by Rupert Hughes, and although not his greatest play, will be found highly diverting as an hour’s entertainment.

N.—It will serve its purpose and is suitable for second-class downtown houses.

T. R.—The “diet and grow thin” theme is funny in spots but likely to weary the average spectator.

---

Picture Play Magazine, October 1923

Keeping Nature’s Gifts

[excerpt]

Colleen Moore’s diet depends upon whether she is putting on flesh for a picture or taking it off. She lived practically on lemon-juice for two weeks, losing ten pounds at the start of “Look Your Best.” For the last scenes she had to regain her avoirdupois, so she went to bed for a week, drank milk-two or three quarts a day and ate cakes and everything.

—

Note: I hate this.

---

Exhibitor’s Herald, 24 November 1923

Goldwyn Cosmopolitan

Look Your Best, with Colleen Moore. —A very good picture that failed to score at all at the box office. I have played ten of these pictures, losing money on eight, breaking even on one, so I really will be glad when they are over with. The advertising matter is my greatest drawback, for I’m a little fellow and can’t afford an artist to make my lobby and have to use their stock stuff, which is bum considering the attractions they represent. Pretty enough, but do not run true with the films. Seven reels.—Hugh G. Martin, American theatre, Columbus, Ga.—General patronage.

Look Your Best, with Colleen Moore and Antonio Moreno.—Two dandy stars wasted in this. Rupert Hughes was unable to convince an audience of movie fans what he was driving at. Lacked interest all the way. Not worth bothering about.—Ben L. Morris, Temple theatre, Bellaire, Ohio.—General patronage.

---

Moving Picture World, December 1923

LOOK YOUR BEST. (6 reels). Star, Colleen Moore. A very ordinary picture that I played on a Saturday night and put in a strong line of fillers and in that way escaped censure. You can play this, but be careful of your accompanying selections and buy it right. Usual advertising brought good attendance. Draw health seekers and tourists. Dave Seymour, Pontiac Theatre Beautiful, Saranac Lake, New York.

LOOK YOUR BEST. (6 reels). Star cast. Nice little comedy-drama. Very light in construction. Seemed to please. Had fair attendance. Draw all classes in town of 1,000. Admission 15-25. Jack Kaplan, Rivoli Theatre (378 seats), South Fallsburg, New York.

---

Best Moving Pictures, 1922-1923

LOOK YOUR BEST. Produced and distributed by Goldwyn. Six reels. Released February 18, 1923. Cast: Colleen Moore and Antonio Moreno. Director, Rupert Hughes. Story of a chorus girl who tried to keep thin.

---

The Educational Screen, February 1924

THE THEATRICAL FIELD

LOOK YOUR BEST (Goldwyn)

Colleen Moore and Antonio Moreno demonstrate the tragic fact that life is very bitter to the lover of sweets when his job depends on his remaining thin. Fair entertainment, making no demands on either actors or audience.

---

Motion Picture Magazine, November 1924

Every Little Bit Helps—to Stardom

By HARRY CARR

[excerpt]

Eleanor Boardman came to the old Goldwyn lot and jumped at once into the top line by a tiny scene in Rupert Hughes’ The Bitterness of Sweets, in which she fainted in a theater box.

—

Note: Given what I noted earlier about the release dates of LYB and Souls for Sale, finding out that a bit role in LYB (here referred to by its working title) led to Eleanor Boardman’s starring role in the latter film is fascinating. Boardman likely filmed her single scene in LYB months before production started on Souls for Sale, which she is the star of. But, because the release of LYB was delayed, Boardman had a bit role and a starring role on screens within a month of each other!

#Look Your Best#The Bitterness of Sweets#lost film#silent comedy#silent era#silent film#silent movies#1920s#1922#1923#Rupert Hughes#Colleen Moore#antonio moreno#eleanor boardman#classic movies#classic film#american film#movie magazine#film magazine#Souls for Sale#ruth st. denis#film history#lost but not forgotten

15 notes

·

View notes