#1780s Denmark

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Oil Painting, 1787, Danish.

By Jens Juel.

Portraying Princess Louise Augusta of Denmark in a white chemise dress.

Frederiksborg Palace Museum.

#Louise Augusta of Denmark#womenswear#dress#1787#1780s#1780s dress#1780s painting#1780s Denmark#Danish#Jens juel#Frederiksborg Palace Museum#chemise à la reine

29 notes

·

View notes

Note

This never gets brought up enough in "why did people used to be thinner discussions". A SIGNIFICANT PERCENTAGE OF ADULTS HAD NO BLOODY TEETH. And a lot of the food tasted like garbage, of course they didn't eat much!

So, in the kindest way possible, I'd like to unpack this. Because I feel like there are some very common fallacies here.

When/where exactly are we talking about? 1780s Mediterranean France? 1960s rural Australia? New York City, 1857, upper-class neighborhood? It's possible to make some time/ place generalities when speaking broadly about cultural trends, but a lot of people talk about a nebulous Back Then so nonspecifically as to be meaningless.

My (limited) research has turned up evidence of preemptive- ie not immediately medically indicated -tooth removal and replacement with dentures, as a rare but not unheard-of practice, among young adults primarily in the UK, Australia, and Atlantic Canada around the 1920s-1970s, mostly in rural and/or working-class communities. Usually with existing tooth decay and expectations of further issues in the future. With some mentions from the US, Denmark, and the Netherlands, same time frame. So the question would then be "were people thinner in those communities at that time? if so, how much? and what role, if any, does voluntary toothlessness play in thinness if we take into account food insecurity and physical labor?"

2. People weren't necessarily thinner "back then." There are a myriad of factors that conspire to give this impression nowadays, from survivorship bias leading smaller clothes and shoes to be disproportionately represented in museums, to photo editing in eras where many of us are now unaware that it existed, to the prevalence of celebrity images over pictures of ordinary people, spotty record-keeping on the subject, improved nutrition in the modern day, beauty standards that caused people to have unhealthy but celebrated body weights, and so on. Further, the so-called "obesity epidemic" only dates back to the 1970s even among those who accept it uncritically, and the adoption of the (flawed) BMI system led many people to be newly classified as overweight who previously were not. I highly recommend historian Kenna Libes' excellent Instagram, Stout Style History, for images of larger women in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

3. You can still eat solid food with dentures (albeit sometimes with difficulties). And a big part of this whole cultural practice was the "replace with dentures" step. For the even smaller subset of patients I've read about who did it for aesthetic reasons, that was the whole point- like capping teeth today. So that's not necessarily an impediment to eating, and therefore to eating-related weight gain/maintenance.

4. Many people in many eras liked their food, or at least some of it. I know the food in mid-20th-century Britain- a nexus of voluntary tooth removal in my research, and I'm guessing where you're from due to the use of "bloody" -is notorious now, and every period and place has folks who aren't fans of some common dishes. But it's hard to believe that these people (especially after first one war with rationing and then another) were turning up their noses enough to lose significant weight, or maintain non-genetic extremely low body weights unrelated to physical labor, sports, etc.. Tastes change- in my own country, the USA, I have to believe that SOMEBODY liked those fluorescent Jell-O salads, or there wouldn't be so many recipes for them.

I hope this doesn't come off too critical or combative; I just had many Thoughts on the premise of your ask.

#ask#anon#teeth#dental trauma#tooth trauma#dental#medical#history#long post#fatphobia mention#disordered eating mention#diet culture mention

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ossian Singing His Swan Song

Artist: Nicolai Abildgaard (Danish, 1743-1809)

Date: 1780-1782

Medium: Oil on canvas

Collection: National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen, Denmark

Description

The Danish artist Nicolai Abraham Abildgaard, like many of his contemporaries, merged influences of Neoclassicism and Romanticism in his work. He was very fond of both classical and Nordic literary motifs. Ossian played a major part in his work, and his Ossian Singing his Swan Song has almost become the defining image of the blind bard.

The last section of Ossian, entitled Berrathon, presages Ossian's death and tells of what will be his last song:

"Such were my deeds, son of Alpin, when the arm of my youth was strong. Such the actions of Toscar, the car-borne son of Conloch. But Toscar is on his flying cloud. I am alone at Lutha. My voice is like the last sound of the wind, when it forsakes the woods. But Ossian shall not be long alone. He sees the mist that shall receive his ghost. He beholds the mist that shall form his robe, when he appears on his hills. The Sons of feeble men shall behold me, and admire the stature of the chiefs of old. They shall creep to their caves. They shall look to the sky with fear: for my steps shall be in the clouds. Darkness shall roll on my side.

Lead, son of Alpin, lead the aged to his woods. The winds begin to rise. The dark wave of the lake resounds. Bends there not a tree from Mora with its branches bare? It bends, son of Alpin, in the rustling blast. My harp hangs on a blasted branch. The sound of its strings is mournful. Does the wind touch thee, O harp, or is it some passing ghost? It is the hand of Malvina! Bring me the harp, son of Alpin. Another song shall rise. My soul shall depart in the sound. My fathers shall hear it in their airy hail. Their dim faces shall hang, with joy, from their clouds; and their hands receive their son. The aged oak bends over the stream. It sighs with all its moss. The withered fern whistles near, and mixes, as it waves, with Ossian's hair.

'Strike the harp, and raise the song: be near, with all your wings, ye winds. Bear the mournful sound away to Fingal's airy hail. Bear it to Fingal's hall, that he may hear the voice of his son: the voice of him that praised the mighty!'"

#painting#oil on canvas#landscape#bearded man#swang song#music#ossian singing#blind bard#cloth#epic poetry#the poems of ossian#literature#nicolai abildgaard#danish painter#oil painting#fine art#dutch culture#dutch painter#national gallery of denmark#artwork#european art#18th century painting#lyre

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Erlking

In European folklore and myth, the Erlking is a sinister elf who lingers in the woods. He stalks children who stay in the woods for too long, and kills them by a single touch.

Pic by Sammycat17 on deviantart

The name "Erlking" is a name used in German Romanticism for the figure of a spirit or "king of the fairies". It is usually assumed that the name is a derivation from the ellekonge (older elverkonge, i.e. "Elf-king") in Danish folklore. The name is first used by Johann Gottfried Herder in his ballad "Erlkönigs Tochter" (1778), an adaptation of the Danish Hr. Oluf han rider (1739), and was taken up by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in his poem "Erlkönig" (1782), which was set to music by Schubert, among others. Goethe added a new meaning, as "Erl" does not mean "elf", but "black alder" - the poem about the Erlenkönig is set in the area of an alder quarry in the Saale valley in Thuringia. In English translations of Goethe's poem, the name is sometimes rendered as Erl-king.

According to Jacob Grimm, the term originates with a Scandinavian (Danish) word, ellekonge "king of the elves", or for a female spirit elverkongens datter "the elven king's daughter", who is responsible for ensnaring human beings to satisfy her desire, jealousy or lust for revenge. The New Oxford American Dictionary follows this explanation, describing the Erlking as "a bearded giant or goblin who lures little children to the land of death", mistranslated by Herder as Erlkönig in the late 18th century from ellerkonge. The correct German word would have been Elbkönig or Elbenkönig, afterwards used under the modified form of Elfenkönig by Christoph Martin Wieland in his 1780 poem Oberon.

Alternative suggestions have also been made; in 1836, Halling suggested a connection with a Turkic and Mongolian god of death or psychopomp, known as Erlik Chan.

Johann Gottfried von Herder introduced this character into German literature in "Erlkönigs Tochter", a ballad published in his 1778 volume Stimmen der Völker in Liedern. It was based on the Danish folk ballad "Hr. Oluf han rider" "Sir Oluf he rides" published in the 1739 Danske Kæmpeviser. Herder undertook a free translation where he translated the Danish elvermø ("elf maid") as Erlkönigs Tochter; according to Danish legend old burial mounds are the residence of the elverkonge, dialectically elle(r)konge, the latter has later been misunderstood in Denmark by some antiquarians as "alder king", cf Danish elletræ "alder tree". It has generally been assumed that the mistranslation was the result of error, but it has also been suggested (Herder does actually also refer to elves in his translation) that he was imaginatively trying to identify the malevolent sprite of the original tale with a woodland old man (hence the alder king).

The story portrays Sir Oluf riding to his marriage but being entranced by the music of the elves. An elf maiden, in Herder's translation the Elverkonge's daughter, appears and invites him to dance with her. He refuses and spurns her offers of gifts and gold. Angered, she strikes him and sends him on his way, deathly pale. The following morning, on the day of his wedding, his bride finds him lying dead under his scarlet cloak.

Although inspired by Herder's ballad, Goethe departed significantly from both Herder's rendering of the Erlking and the Scandinavian original. The antagonist in Goethe's "Der Erlkönig" is the Erlking himself rather than his daughter. The Erlkönig appears to a young boy in a feverish delirium - his father, however, identifies the apparition as a simple streak of fog. Goethe's Erlking differs in other ways as well: his version preys on children, rather than adults of the opposite sex, and the Erlking's motives are never made clear. Goethe's Erlking is much more akin to the Germanic portrayal of elves and valkyries – a force of death rather than simply a magical spirit.

In Angela Carter's short story "The Erl-King", contained within the 1979 collection The Bloody Chamber, the female protagonist encounters a male forest spirit. Though she becomes aware of his malicious intentions, she is torn between her desire for him and her desire for freedom. In the end, she forms a plan to kill him in order to escape his power.

Charles Kinbote, the narrator of Vladimir Nabokov's 1962 novel, Pale Fire, alludes to "alderkings". One allusion is in his commentary to line 275 of fellow character John Shade's eponymous poem. In the case of this commentary, the word invokes homosexual ancestors of the last king of Zembla, Kinbote's ostensible homeland. The novel contains at least one other reference by Kinbote to alderkings.

In Jim Butcher's The Dresden Files, there is a character called the Erlking, modeled after the leader of the Wild Hunt, Herne the Hunter.

In the author John Connolly's short story collection Nocturnes (2004), there is a character known as the Erlking who attempts to abduct the protagonist.

The New Yorker's "20 Under 40" issue of July 5, 2010 included the short story "The Erlking" by Sarah Shun-lien Bynum.

A version of the Erl-King is mentioned in Zoe Gilbert's Mischief Acts, implied to be a figure related to Herne the Hunter.

In Andrzej Sapkowski's The Witcher saga, the highest leader of the Folk of the Alder elves, Auberon Muircetach, is also known as the Alder King. In the story, he maintains thematic ties to kidnapping: the Wild Hunt, known for abducting humans, is subordinate to him, and he orchestrates the imprisonment of Cirilla.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

La Morte

The sick child, 1896 | Edvard Munch (1863-1944, Norway)

Funerale bianco (White funeral), 1901 | Edoardo Berta (1867-1931, Italia)

Autoritratto macabro (macabre self-portrait), 1899 | Carlo Fornara (1871-1968, Italia)

Tombe romane (roman tombs), Concordia (Venice), 1887 | Filippo Franzoni (1857-1911, Switzerland)

Miseria, 1886 | Cristóbal Rojas (1857-1890, Venezuela)

Böcklin's grave, 1901-02 (Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe) | Ferdinand Keller (1876-1958, Germany)

The widow (detail), 1882-83 | Anders Zorn (1860-1920, Sweden)

L’adultera o La femme de Claude, 1877 (Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Torino) | Francesco Mosso (1848-1877, Italia)

The funeral of Shelley, 1889 | Louis Édouard Fournier (1857-1917, France)

La peine de mort | Félicien Rops (1833-1898, Belgium)

Funeral at sea (on the death of the painter David Wilkie), 1842 (Tate Gallery, London) | William Turner (1775-1851, England)

La mort de Marat, 1793 (Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts, Bruxelles) | Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825, France)

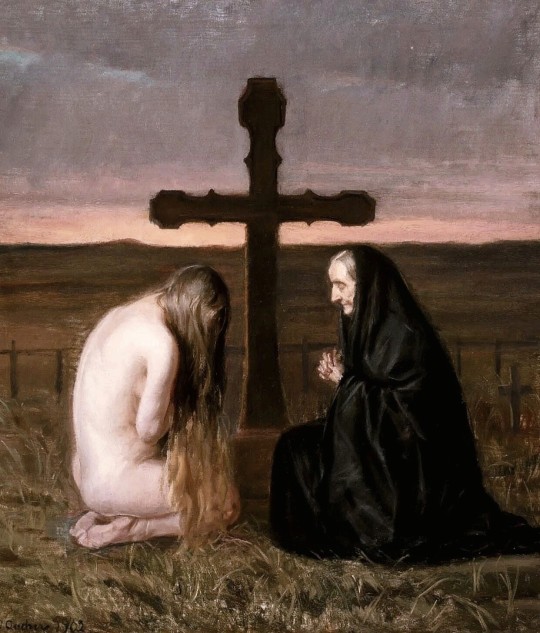

Le jour des morts, 1859 (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux) | William Adolphe Bouguereau (1825-1905, France)

Bradamante at Merlin's tomb, 1820 | Alexandre-Évariste Fragonard (1780-1850, France)

Death on the pale horse, 1865 | Gustave Doré (1832-1883, France)

Il trionfo della morte, 1464 ca. (Palazzo Abatellis, Palermo) | Anonimo

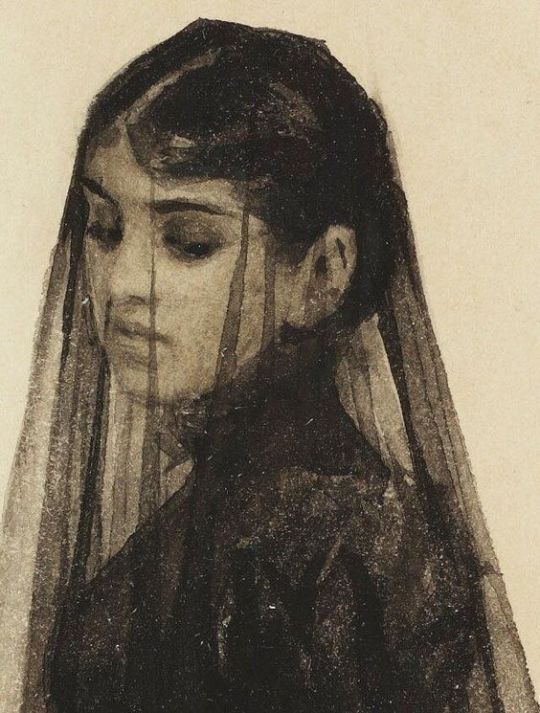

Roman widow | Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882, England)

Cemetery in the moonlight, 1822 | Carl Gustav Carus (1789-1869, Germany)

The plague, 1898 | Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901, Switzerland)

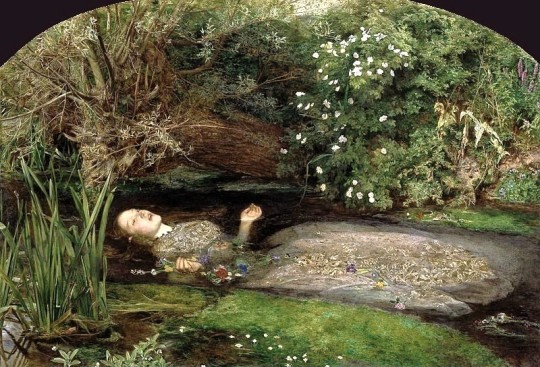

Ophelia, 1851-52 (Tate Britain, London) | John Everett Millais (1829-1996, England)

Grief, 1902 | Anna Ancher (1859-1935, Denmark)

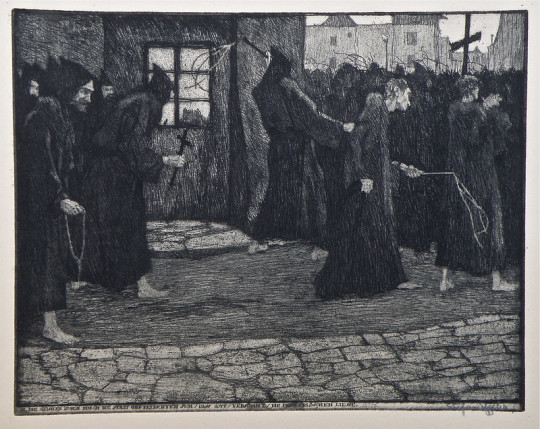

The plague of pestilence, portfolio (two of seven etchings), 1920 | Stefan Eggeler (1894-1969, Austria)

The plague of pestilence, portfolio (three of seven etchings), 1920 | Stefan Eggeler (1894-1969, Austria)

Dr. Nicolaes Tulp's anatomy lesson, 1632 | Rembrandt (1606-1669, Netherlands)

La sepoltura del conte di Orgaz (El Entierro del conde de Orgaz), 1586 (Chiesa di Santo Tomé, Toledo) | El Greco (1541-1614, Greece)

Woman on her deathbed, 1883 (Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo) | Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890, Netherlands)

Princess Tarakanova, in the Peter and Paul Fortress at the time of the flood, 1864 | Konstantin Flavitsky (1830-1866, Russia)

6 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

DeSantis said no one questioned slavery before Americans. See Van Jones ...

CHRONOLOGY-Who banned slavery when?

By Reuters Staff

3 MIN READ

(Reuters) - Britain marks 200 years on March 25 since it enacted a law banning the trans-Atlantic slave trade, although full abolition of slavery did not follow for another generation.

Following are some key dates in the trans-atlantic trade in slaves from Africa and its abolition.

1444 - First public sale of African slaves in Lagos, Portugal

1482 - Portuguese start building first permanent slave trading post at Elmina, Gold Coast, now Ghana

1510 - First slaves arrive in the Spanish colonies of South America, having travelled via Spain

1518 - First direct shipment of slaves from Africa to the Americas

1777 - State of Vermont, an independent Republic after the American Revolution, becomes first sovereign state to abolish slavery

1780s - Trans-Atlantic slave trade reaches peak

1787 - The Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade founded in Britain by Granville Sharp and Thomas Clarkson

1792 - Denmark bans import of slaves to its West Indies colonies, although the law only took effect from 1803.

1807 - Britain passes Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, outlawing British Atlantic slave trade.

- United States passes legislation banning the slave trade, effective from start of 1808.

1811 - Spain abolishes slavery, including in its colonies, though Cuba rejects ban and continues to deal in slaves.

1813 - Sweden bans slave trading

1814 - Netherlands bans slave trading

1817 - France bans slave trading, but ban not effective until 1826

1833 - Britain passes Abolition of Slavery Act, ordering gradual abolition of slavery in all British colonies. Plantation owners in the West Indies receive 20 million pounds in compensation

- Great Britain and Spain sign a treaty prohibiting the slave trade

1819 - Portugal abolishes slave trade north of the equator

- Britain places a naval squadron off the West African coast to enforce the ban on slave trading

1823 - Britain’s Anti-Slavery Society formed. Members include William Wilberforce

1846 - Danish governor proclaims emancipation of slaves in Danish West Indies, abolishing slavery

1848 - France abolishes slavery

1851 - Brazil abolishes slave trading

1858 - Portugal abolishes slavery in its colonies, although all slaves are subject to a 20-year apprenticeship

1861 - Netherlands abolishes slavery in Dutch Caribbean colonies

1862 - U.S. President Abraham Lincoln proclaims emancipation of slaves with effect from January 1, 1863; 13th Amendment of U.S. Constitution follows in 1865 banning slavery

1886 - Slavery is abolished in Cuba

1888 - Brazil abolishes slavery

1926 - League of Nations adopts Slavery Convention abolishing slavery

1948 - United Nations General Assembly adopts Universal Declaration of Human Rights, including article stating “No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Events 10.10. (before 1960)

19 – The Roman general Germanicus dies near Antioch. He was convinced that the mysterious illness that ended in his death was a result of poisoning by the Syrian governor Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso, whom he had ordered to leave the province. 680 – The Battle of Karbala marks the martyrdom of Husayn ibn Ali. 732 – Charles Martel's forces defeat an Umayyad army near Tours, France. 1471 – Sten Sture the Elder, the Regent of Sweden, with the help of farmers and miners, repels an attack by King Christian I of Denmark. 1492 – The crew of Christopher Columbus's ship, the Santa Maria, attempt a mutiny. 1575 – Roman Catholic forces under Henry I, Duke of Guise, defeat the Protestants, capturing Philippe de Mornay among others. 1580 – Over 600 Papal troops land in Ireland to support the Second Desmond Rebellion. 1760 – In a treaty with the Dutch colonial authorities, the Ndyuka people of Suriname – descended from escaped slaves – gain territorial autonomy. 1780 – The Great Hurricane of 1780 kills 20,000–30,000 in the Caribbean. 1814 – War of 1812: The United States Revenue Marine attempts to defend the cutter Eagle from the Royal Navy. 1845 – In Annapolis, Maryland, the Naval School (later the United States Naval Academy) opens with 50 students. 1846 – Triton, the largest moon of the planet Neptune, is discovered by English astronomer William Lassell. 1868 – The Ten Years' War begins against Spanish rule in Cuba. 1903 – The Women's Social and Political Union is founded in support of the enfranchisement of British women. 1911 – The day after a bomb explodes prematurely, the Wuchang Uprising begins against the Chinese monarchy. 1913 – U.S. President Woodrow Wilson triggers the explosion of the Gamboa Dike, completing major construction on the Panama Canal. 1918 – RMS Leinster is torpedoed and sunk by UB-123, killing 564, the largest loss of life on the Irish Sea. 1920 – The Carinthian plebiscite determines that the larger part of the Duchy of Carinthia should remain part of Austria. 1928 – Chiang Kai-shek becomes Chairman of the Republic of China. 1933 – A United Airlines Boeing 247 is destroyed by sabotage, the first such proven case in the history of commercial aviation. 1935 – In Greece, a coup d'état ends the Second Hellenic Republic. 1938 – Abiding by the Munich Agreement, Czechoslovakia completes its withdrawal from the Sudetenland. 1945 – The Double Tenth Agreement is signed by the Communist Party and the Kuomintang about the future of China. 1954 – The Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Sultanate of Muscat, Neil Innes, sends a signal to the Sultanate's forces, accompanied with oil explorers, to penetrate Fahud, marking the beginning of Jebel Akhdar War. 1957 – U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower apologizes to Ghanaian finance minister Komla Agbeli Gbedemah after he is refused service in a Delaware restaurant. 1957 – The Windscale fire results in Britain's worst nuclear accident.

0 notes

Text

July 27, 1809

Couche 1. Rose 7. Before breakfast to Bergström’s, whom I found. His uncle is a celebrated advocate, whose acquaintance I wish to aid my legal researches. To Breda’s; out. M’lle sang and played for me. Home to breakfast. Replied very honêtely¹ to the Baron d’Albedÿhll’s note. To a watchmaker who says he can replace the glasses and that the watch has sustained no other injury. I danced for joy at this news. To Hedboom’s, whom I found; got my 6 ducats which are now worth 4 dollars Rixelt each. He offered me many civilities. To Breda’s again, whom saw only to ask a question. Home to study law. No, I came by Ulrick’s, the bookseller, to get a book written by le Baron d’Albedÿhll, which got. Read a book before you see the author. Sat half an hour with M'lle Ulrick. She is beautiful, very beautiful; about 15, nearly your size and form. Speaks German and French fluently. Her elder sister keeps a bookstore at Nÿkooping or Noskyping, I forget which. Dit,² that she is also beautiful, knows all languages, ancient and modern, &c, &c. Single; boit’e.³ Home at 1/2 p. 1. Read the Baron’s book. Only about fifty pages, extremely well written in French. The rest of the volume is made up of documents and public letters. The subject is a history of the armed neutrality, the whole merit of which has been given to Catherine of Russia. No such thing! It originated in a treaty made between Denmark and Sweden in 1756; renewed between them in 1779. Catherine, during all that year, and till July, 1780, refused to come into it, fearing the effect on the belligerent powers. At length, in that month, by the influence of Count Panin, her minister, she acceded. At 5 to Judge Poppius’s, whom, fortunately, I found smoking in his office. He would transfer me over to his beautiful wife till he made his toilette⁴; but I sat down and took a pipe, and had an hour's very satisfactory conversation with him. Went in to tea, but took none. Y: Madame Djyrta and M’lle ———, her sister. At 8 to Helvig’s to see for Louisa; out; not even a servant. Home, and sat to read law. Fillibonka at 4. No supper. I do not report to you my Swedish law; that has a separate department, and many curious things will be found in it. Met Mrs. Daily in the street this morning.

1 A hybrid adverb made from the adjective mentioned in note 9, preceding letter. 2 Said. 3 For boiteuse. Lame. 4 Toilet.

0 notes

Text

Learn From the Best: How to Play eos 파워볼 5분 | Viejas Casino and Resort

Like the Don't Pass each player may only make one Don't Come bet per roll, this does not exclude a player from laying odds on an already established Don't Come points. Players may bet both the Don't Come and Come on the same roll if desired.The city uses automatic shuffling machines in every new deck with only eight-deck games. As a result, you miss the chances of getting edges through card counting. Shuffling should continue until the chance of a card remaining next to the one that was originally next to is small. In practice, many dealers do not shuffle for long enough to achieve this. Using a standard 52-card deck, the object is to rid oneself of all of one's cards. Cards can be played in certain combinations, including familiar poker combinations such as straights, flushes, and full-houses.

The player can fold or raise and then the best five-card poker hand possible for each player is used to determine the winner. Players are playing against the house and each player may take only one seat at the table.It is a rich and interesting heritage from which the English pattern emerges, and it owes much to the French for their ingenuity in design and style. here are no attendants, and so the progress of the game, fairness of the throws, and the way that the payouts are made for winning bets are self-policed by the players. The dealers will insist that the shooter roll with one hand and that the dice bounce off the far wall surrounding the table.

If the player requests the Come odds to be not working ("Off") and the shooter sevens-out or hits the Come bet point, the Come bet will be lost or doubled and the Come odds returned.There are different number series in roulette that have special names attached to them. By 2008, there were several hundred casinos worldwide offering roulette games. The double zero wheel is found in the U.S., Canada, South America, and the Caribbean, while the single zero wheel is predominant elsewhere. The 1780s-Throughout the 18th Century, French card makers had enjoyed export trade across Europe. The regions of Limoges, Bordeaux and Theirs exported to Spain, Lyons traded with Switzerland, and the Rouen pattern was circulating in as far apart as Sweden, Russia, Denmark, Flanders and England. By the 1780s, many of the regional patterns were fading away, and the Paris pattern rose to pre-eminence as the general pattern throughout France.

As well as the support options and their quality. Step up to the table and place a bet on the box marked Ante. At this time, you also may place a $1 Progressive bet on the marked space.If you happen to be dealt a flush, full house, four-of-a-kind, straight flush or royal flush and have placed a $1 Progressive bet, you will win additional money.Casino game machines have been introduced at racetracks to create racinos. In some states, casino-type game machines are also allowed in truck stops, bars, grocery stores, and other small businesses. The Saint Anne Glassworks (now Cristallerie de Baccarat) at 6-49 Rue des Cristalleries (1764-1954)It’s still all too easy to make mistakes in the casino if you don’t know what you’re doing, so it’s important that you make sure you fully understand a game before you start playing it.

The house advantage (or “edge”) is the difference between the true odds (or the mathematical odds) and what a casino pays.These are bets that the number bet on will be rolled before a 7 is rolled. In Bank Craps, the dice are thrown over a wire or a string that is normally stretched a few inches from the table's surface.eos 파워볼 5분It looks like a small loss with the 6 to 5 game, but the losses are significantly experienced when you bet with a large amount.

Although the full-pay version has a theoretically-positive return, few play well enough to capitalize on it. Double Bonus is a complex game.Therefore, casino games take place in massive resorts as well as in small card rooms. Example: First ball is 22. All numbers beginning or ending with a 2 is considered a called number.Today video poker enjoys a prominent place on the gaming floors of many casinos. The game is especially popular with Las Vegas locals, who tend to patronize locals casinos off the Las Vegas Strip. These local casinos often offer lower denomination machines or better odds.

Five chips or multiples thereof are bet on four splits and a straight-up: one chip is placed straight-up on 1 and one chip on each of the splits: 6-9, 14-17, 17-20, and 31-34.When it got its way to other continents like the United States, many casinos promoted the game by giving an additional winning to any player who had a blackjack winning hand. Commercial gambling operators, however, usually make their profits by regularly occupying an advantaged position as the dealer, or they may charge money for the opportunity to play or subtract a proportion of money from the wagers on each play.Strip poker is a traditional poker variation where players remove clothing when they lose bets.

Fan-tan is no longer as popular as it once was, having been replaced by modern casino games like Baccarat, and other traditional Chinese games such as Mah Jong and Pai Gow. Fan-tan is still played at some Macau casinosBonus Poker is a video poker game based on Jacks or Better, but Bonus Poker offers a higher payout percentage for four of a kind. This terrifies casino operators, as it is difficult and expensive to recover from perceptions of a high-priced slot product.The Tower of Voués was the keep of the castle built in 1305 by Count Henry I to protect the serfs' houses. It measures 11.70 m in the North by 14.70 m in the East and its height is approximately 30 m. It was sold in 1332 by Henry III to Adhémar de Monteil (Bishop of Metz) who built a castle around which Baccarat would be built.

0 notes

Text

A sympathetic nod; considering how much people tend to struggle with Danish pronunciation (and although his Danish isn't terrible, how often he pokes fun at it, himself), English might be their best option.

"Oh, right. I remember, uh, reading about this." He feels a little silly — despite their geographical proximity, their histories... He was so far, and so sheltered from everything. It's these things he's heard of in passing, but dates, details... Hell, he didn't even really get to know Sweden properly - outside of a very Danish perspective, of course - until much more recently in his history. "I'm sorry, I was... very isolated. I only know these things kind of, eh, in passing. I know Danish history very well, but..." He coughs into his elbow again, and then waves a hand apologetically. "I was with Denmark. That sounds right."

Those years kind of blurred together, now he thinks back on them. Even though things were pretty good up until the late 1780s, the period after that had been so endlessly horrible that it kind of mixed everything up in his mind. He coughs again, and then rubs sheepishly at the back of his neck. "It's strange, isn't it? I mean, it's a positive thing, of course, but... Do you remember wondering if it would ever happen?"

Fannar opts to keep his layers on — with the eruption back home, he's perpetually feeling a little bit chilly. The sun does take the edge off, though, and he leans back against the wall as well with a smile and a shrug of his shoulders. "I think the same, sometimes. It's a self fulfilling prophecy, I think." Sometimes he wonders if they just like hearing themselves talk, but that would probably be a little bit rude to say aloud.

"Ah, well —" He coughs into one hand again, and then scratches thoughtfully at one cheek. "I can sort of... understand it better than I can speak it, but not fluenly, I don't think. I could probably speak a bit of it, if it was really necessary, but — probably not very well. Danish is my most fluent of the Scandinavian languages." Then, with a little laugh followed by another cough — "Even that's not very fluent anymore. I think I could understand a decent amount of what was being said, but would have to reply in Danish most of the time. And, I don't think the people speaking Swedish could understand me so well, then, if that makes sense."

But then he tucks a strand of hair back behind his ear and asks, "Do you speak Swedish more than the other Scandinavian languages? I-I'm sorry, I'm not the best with who knows who and everything. I know we all have some history, but," Another cough, and then he waves a hand apologetically. "I was a bit distant from everything on the mainland."

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

Robe de cours from 1700-1720s look like they have slim hips while the ones from the 1740s-1770s. Those one have really wide hips.

Aaah... yes. I’m sorry I don’t know if this is a question? No? Well, I’m assuming it is you, Anonymous, giving us all a start for a cool conversation ;)

The fashionable silhouette for the 18th century starts slim, gets really wide at the middle of the century, and ends being slim again. This is seen in the fashionable dress, and also the robe de cour (plural robes de cour), even though the bodice of the dress remains the same pretty much until the end of the century, the skirt shape and size changes with the fashion of the decade. At the end of the century, after the French Revolution and with the Regency fashion things for the robes de cour went, well, weird. You’ll see at the end of the post.

This dress is also called by other names, so you can find info about the grand habit, grand habit de cour, or stiff bodied gown, and all of them are the same dress. Because why not. LOL. It evolved from the mantua worn at court during the 17th century.

Here a small timeline for the robes de cour:

“Engraving of Marie Thérèse de Bourbon, Princesse de County”, ca. 1690.

“Princess Anne”, 1728, Philippe Mercier, Hertford Town Council.

“Portrait of Lady Frances Montagu”, ca. 1734, Charles Jervas.

Mantua, 1740s, Victoria & Albert Museum.

Marie Leszczinska, queen of France, 1747, Carle Van Loo.

British court dress, ca. 1750, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Coronation dress (robe de cour) of Queen Lovisa Ulrika of Sweden, 1751, Royal Armoury, Sweden.

Catherine the Great’s coronation robe, 1762.

Sofia Magdalenas wedding dress (robe de cour), 1766, Statens Historiska Museer.

Maria Carolina of Austria, about 1760-70, Martin van Meytens.

Sofia Magdalena of Denmark, 1773-74, Lorens Pasch the Younger.

“Habit de cour de satin cerise”, 1779, fashion plate from Gallerie des Modes.

Marie Antoinette of Austria, Queen of France, 1783, Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun.

Robe de cour of Ekaterina Pavlovna, late 1780s, attributed to Rose Bertin.

Robe de cour of Grand Duchess Ekaterina Pavlovna, 1790s.

Her Royal Highness the Princess of Wales in her court dress on the fourth of June, 1807, as authentically taken from the real dress by Mrs. Webb of Pall Mall. London.

#Anonymous#robe de cour#court gown#18th century#18th century fashion#womenswear#court#european courts#marie antoinette#1780s#1783#louise elisabeth vigee le brun#french court#habit de cour#1770s#1779#denmark#france#danish court#sweden#swedish court#sofia magdalena of denmark#Lorens Pasch the Younger#maria carolina of austria#austrian court#Martin van Meytens#1760s#1766#Queen Lovisa Ulrika of Sweden#1750s

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

Silver and Blue Silk Dress, 1725-1789, Danish.

Met Museum.

#met museum#silk#dress#womenswear#18th century#1720s#1730s#1740s#1750s#1760s#1770s#1780s#1725#danish#Denmark#silver#extant garments#1770s Denmark#1780s Denmark#1770s dress#1780s dress

62 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Dress

1725-1789

Danish

The MET

#dress#fashion history#historical fashion#18th century#1720s#1730s#1740s#1750s#1760s#1770s#1780s#denmark#danish#baroque era#rococo era#silk#baroque fashion#rococo fashion#the met

480 notes

·

View notes

Text

A controversy erupted in 2018 when the famous French artist Johnny Hallyday (sometimes known as the French Elvis or France’s rock-and-roll “national hero”) was buried in the island of St. Barthélemy. Many fans complained about this decision. [...] Even though St. Barthélemy has been under France’s jurisdiction since 1878, the controversy around Hallyday's burial site is a reminder that, for many French people, St. Barthélemy is not really part of France.

Jeppe Mulich’s In a Sea of Empires fosters our understanding of the complicated and multilayered place of the Caribbean in historical imagination. The book explores the Leeward Islands, an archipelago of small islands in the northeastern Caribbean, in particular the British Virgin Islands (Antigua and St. Christopher), the Danish Virgin Islands (St. Thomas and St. Croix), and the Swedish St. Barthélemy (France colonized the island in 1648 and sold it to Sweden in 1784 before gaining it back in 1878).

These islands shared many features: they had a highly polyglot and diverse population, the majority of which was enslaved; they were home to a higher share of free people of African descent than larger plantation islands; their expansive coasts and rocky terrains made them more suited for maritime trade while other colonies relied on large-scale agricultural plantation production; they had small military forces. Furthermore, neither Sweden nor Denmark was particularly interested in the day-to-day administration of their colonies and lacked the enforcement to do so, leading to a form of “laissez-faire sovereignty” (p. 78) that characterized life in the Leeward Islands.

-------

Adopting a micro-regional perspective, Mulich frames the book around the concept of “inter-imperial region,” [...] defined as “a geographical area inhabited by multiple polities, with a particularly high density of relations and interactions between and across the formal boundaries of these polities” (p. 16). [...] In a Sea of Empires proves that movement of people across imperial borders formed an integral aspect of micro-regional systems. The book brings this ground-level perspective to little-studied smaller imperial powers in the Atlantic world such as Sweden and Denmark-Norway. [...] [C]hapter 2 delves into the formal and informal trade of King Mammon. It studies political economy and commercial practices and networks. The chapter starts with the end of the imperially sanctioned trading companies, the Danish West India and Guinea Company and the Swedish West India Company, in the 1780s. The Danish and Swedish colonies were declared free ports and British colonies replaced state-sponsored smuggling practices of the eighteenth century through the practice of free trade. More than an ideological decision, the demise of earlier systems of trade control was a practical response to the fact that European powers could not regulate the flow of trade in the region. [...]

-------

Chapter 3 switches to the goddess of war Bellona. The eighteenth- and the early nineteenth-century world, Mulich reminds us, was a world at war. Limited military infrastructures left the Leeward Islands vulnerable to invasions, insurrections, and rebellions. In this chapter, Mulich carefully shows how the colonial social and political order managed to remain stable in an era of revolutions and upheavals. Inter-imperial rivalries take center stage in the chapter, especially during the 1790s, and the fear that the French Atlantic Revolution would spread its brand of republicanism to the Leeward Islands alongside the fear that enslaved people would rise up like they did in the French colonies. This fear of insurrection (Mullich uses the term paranoia several times) prompted colonial administrators to push aside their rivalries to protect their political and social system from the perceived threats of slave uprisings and colonial rebellions.

The heirs to Francis Drake and Robert Surcouf are the topic of chapter 4 with the resurgence of privateering during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-15) and the start of the Latin American independence movements after 1808. Privateers received commissions, or letters of marque, from countries at war in the Greater Caribbean region. They took advantage of the location of the Leeward Islands as well as the environment of the islands, hiding in coves and islets to attack enemy vessels. The islands were also the perfect markets for the merchandise and human beings they seized from enemy ships. St Barthélemy became a central privateering hub in the region thanks to preexisting human and commercial networks and a lenient governor. The focal point of this chapter is not so much on privateers themselves as on the establishment of prize courts especially in the British islands: Mullich argues that prize courts illustrate the clashes over jurisdiction that characterized the region and eventually led to British ascendance.

-------

Jurisdictional tensions and legal-political struggles are also present in chapter 5, this time around slave codes and legal frameworks and practices around slavery. In a rich and dense chapter, Mulich tackles various topics such as the rise of abolitionist sentiment in Europe, amelioration programs in the British world, its impact on the Leeward Islands, the efforts by free people of color to obtain political and economic rights, maritime marronage, and the villages, like Kingstown, set up for the Africans “liberated” by the British from foreign slave ships. The close proximity of the islands meant that slave codes were circulated, copied, and imitated, and so were ideas around freedom and self-liberation. [...]

The last chapter focuses on the abolition of the slave trade. The Danish and British empires passed laws outlawing the trade in 1792 and 1807, respectively. [...] Mulich argues that a micro-regional perspective reveals the gaps between imperial policies and local practices since many administrators and merchants in the Leeward Islands circumvented decrees and decisions coming from Europe. This chapter also gives Mulich the opportunity to document the rise of British imperial influence in the region through slave trade treaties, mixed commission courts, and naval hegemony. Bans on international slave trade were not only inconsistently enforced, but they also did nothing to prevent “domestic” or inter-island slave trade, and enslaved people continued to be forcibly transported across islands. [...]

---

In the Sea of Empires also opens up the possibility to trace more connections and networks between the Leeward Islands and other parts of the Caribbean and the Americas [...]. Other scholars might be interested in placing the Leeward Islands in connection with the French and/or the Spanish Caribbean, Venezuela, and especially neighboring Haiti, which was the only free and independent country in the Caribbean. Mulich mentions fears around Haiti and especially the insurrections of the 1790s, but Haiti became a geopolitical player in the region in the early nineteenth century. The wonderful digitalization project by the Danish National Archives has made five million documents about the Danish West Indies available for free online: [virgin-islands-history dot org/en]. This amazing resource is sure to fuel our understanding of the place of the Leeward Islands in global history.

---

All text above by: Vanessa Mongey. “Review of Mulich, Jeppe, In a Sea of Empires: Networks and Crossings in the Revolutionary Caribbean”. H-LatAm, H-Net Reviews. Published online September 2021. [Bold emphasis and some paragraph breaks/contractions added by me.]

#more on scandinavian and nordic colonialism and swedish amnesia about slavery#piracy#Caribbean#maroon#revolution

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

European powers on the eve of the French Revolution, 3/3

The last category of European states included weaker polities that could not effectively compete on the international level, frequently served as subsidiaries to greater powers, and occasionally turned into conflict zones. Until the later nineteenth century central Europe was occupied by the Holy Roman Empire, one of the most irrational institutions in what was proudly described as the Age of Reason. This was hardly an empire in the traditional sense of the word, but rather a patchwork of more than three hundred polities owing allegiance to the Holy Roman Emperor. The empire was ethnically, religiously, and politically fragmented; as the French philosopher Voltaire famously remarked, it was "neither holy, nor Roman, nor an Empire."

[..]

Like the Holy Roman Empire, Switzerland was also a disunited conglomeration of cantons, but it combined a burgeoning banking business with the equally lucrative hiring out of mercenaries to European powers. Italy remained divided into more than half a dozen states and subject to the domination of foreign powers. Lombardy remained firmly under Austrian control, though the thousand-year old Venetian Republic, in the northeastern corner of the Italian peninsula, defended its interests. Meanwhile, the kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia jealously guarded its position in the northwest and on the island of Sardinia, while the popes controlled a broad swath of central Italy. The largest state was the Kingdom of the Two-Sicilies, a rather confusing name for a realm that centered around the city of Naples but straddled the island of Sicily and all of southern Italy.

The once-mighty Polish kingdom had degenerated into a feeble political entity that became, as we've seen, the target of Russian, Austrian, and Prussian ambitions before ceasing to exist entirely in 1795. The Dutch Republic drew vast wealth from its East Indian possessions and the Cape of Good Hope, but of even greater importance was its great financial centers to which all of Europe came to borrow money. Although affluent, the Dutch state was also torn by internal dissent, politically weak, and dominated by its neighbors. Defeated in the fourth Anglo-Dutch war (1780-1784), the Dutch experienced domestic turmoil that resulted in the Prussian invasion in 1787. In the meantime, Scandinavia comprised just two states. After enjoying its golden age in the seventeenth century, the Swedish Empire (which included Finland) had gradually turned into a regional power whose influence in the Baltic was continually contested by Russia and Britain. Which is why Sweden was anxious to acquire Norway, then linked by a common crown to Denmark, Sweden's perennial rival.

This broad categorization of European states during the revolutionary era is useful when discussing the variety of interests and conflicts present in this period. Though the Revolution added a significant ideological dimension, there was a clear continuity of interests from before the revolutionary era, and European powers continued to be guided by traditional factors, such as longstanding rivalries and territorial interests. So while the execution of the French king caused the Spanish Bourbons to join the First coalition against France in 1793, it did not prevent the same Spanish monarchy from allying itself to the French republic in 1796. The Polish Partitions of 1792 and 1795 reflected the continental powers' sense of opportunity created by the outbreak of political turmoil in France as well as their concern about one another's expansionism.

Alexander Mikaberidze- The Napoleonic Wars, A Global History.

#xviii#french revolution#alexander mikaberidze#the napoleonic wars: a global history#european powers on the eve of the french revolution#holy roman empire#switzerland#lombardy#piedmont sardinia#kingdom of the two-sicilies#poland#the dutch republic#sweden#denmark

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Stable Interior, 1780, Museum of the Netherlands

This heavyset horse of Polish and Spanish bloodlines was bred in the royal stud farm at Frederiksborg Castle in Denmark. The artist drew the animal in the stables of the stadholder’s court in The Hague, where he worked as a portraitist. Ironically, he reaped the most success not with his portraits of people, but with his paintings and drawings of horses – whether or not they included a rider or stable hand.

http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.226695

10 notes

·

View notes