#1001 Films You Must See Before You Die

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

羅生門 / Rashomon (1950) | dir. Akira Kurosawa.

#1950s#films#my screencaps#mine#akira kurosawa#jidaigeki#cinematography#screencaps#subtitles#japan#movies#50s#japanese cinema#japanese film#1950s films#1950s movies#50s film#50s movies#cinema#criterion collection#1001 movies you must see before you die#japanese#b&w#black and white#old movies#old films

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

VAGABOND:

Drifter found frozen

Locals recall meeting her

She won’t stay in place

youtube

#vagabond#random richards#poem#haiku#poetry#haiku poem#poets on tumblr#haiku poetry#haiku form#agnes varda#criterion collection#criterion channel#sandrine bonnaire#macha meril#Stephane Freiss#1001 movies you must see before you die#1001 movies#cannes film festival#best actress#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Ancient Rome through the art of Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema.

"Alma-Tadema's highly detailed depictions of Roman life and architecture, based on meticulous archaeological research, led Hollywood directors to his paintings as models for their cinematic ancient world, in films such as D. W. Griffith's Intolerance (1916), Ben Hur (1926), and Cleopatra (1934). The design of the Oscar-winning Roman epic Gladiator (2000) took its main inspiration from his paintings, as well as that of the interior of Cair Paravel castle in The Chronicles of Narnia (2005)" "Alma-Tadema' s The Tepidarium (1881) is included in the 2006 book 1001 Paintings You Must See Before You Die." (Wikipedia. org)

Tibullus at Delia's (1866) The Roman poet Tibullus is shown reciting to a group of friends in the house of his mistress, Delia.

The Tepidarium (1881) Lounging next to the tepidarium (warm room of the baths) a curvaceous beauty takes her rest. She holds a strigil in her right hand. Oil on panel

Amo te, ama me (1881). Oil on panel

A Roman Emperor AD 41 (1881) Oil on canvas

Spring (1894) Oil on canvas

Caracalla and Geta (1907)

A Favourite Custom (1909) Oil on panel

The Meeting of Antony and Cleopatra (1883) Oil on canvas

An Audience at Agrippa's (1876) Oil on canvas

Caracalla (1902) Oil on panel

The Triumph of Titus: The Flavians (1885) Oil on canvas

Entrance of the theatre (1866) Oil on canvas

The Oleander (1882)

The flower market (1868)

An Eloquent Silence (1890) Oil on panel

The Frigidarium (1890) -Cold water room of the baths- Oil on canvas

Watching and waiting (1897)

The poet Gallus dreaming (1892) Oil on panel

The roses of Heliogabalus (1888) Oil on canvas

A balneatrix (1876) Watercolour painting

A Roman Art Lover (1868) Oil on panel

The Cymbal Player (1872) A Garden Altar (1879

The mirror (1868) Oil on canvas

A Collection of Pictures at the Time of Augustus (1867) Oil

A Sculpture Gallery in Rome at the Time of Agrippa (1867)

Hadrian Visiting a Romano-British Pottery (1884) Oil on canvas

The Baths at Caracalla (1899)

Unconscious Rivals (1893) Oil on panel

Silver Favourites (1903) Oil on wood

258 notes

·

View notes

Text

Providing some context to this film due to the nature of its contents. This film appears on the list “1001 Films You Must See Before You Die,” which this blog is currently using for polls. It is a compilation of films deemed important to watch for those interested in cinema as determined by dozens of film critics. The Birth of a Nation appears on that list, and thus this poll blog, because of its technical feats- as it says on its Wikipedia: “it was the first American-made film to have a musical score for an orchestra[, and] it pioneered closeups and fadeouts”- but also because of its historical significance. This film is infamously extremely racist, with a plot line that demonizes African Americans (largely portrayed by white people in blackface) while glorifying the KKK to such a degree that studies even link the film to a rise in support for the racist hate group. This was also the first movie to be screened in the White House, to President Woodrow Wilson, so its historical significance cannot be downplayed.

I am thus choosing not to omit this film from this blog’s polling pool despite its nefarious nature because I am interested in how familiar people are with it and its role in history. I encourage anyone voting “haven’t heard of this movie” to at least read the Wikipedia article (my source for all of the above information) about it as it’s important to be aware of prominent films like this and how they did and continue to impact the culture we reside in.

#movies#polls#the birth of a nation#10s movies#d.w. griffith#racism cw#have you seen this movie poll

399 notes

·

View notes

Text

okay it pisses me off so bad when i'm looking at a movie on letterboxd and I click through to see which lists people have put it in, hoping to see like similar movies or other goodies in the genre or interesting connections it has to other films and then the first full page of results is like '1001 movies you must see before you die' 'Random movie roulette' 'All the movies' 'Every movie' 'The ultimate I can't pick a movie list' all with hundreds and hundreds of unrelated films in them. fuck offfffffff. please.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

The King of Comedy

never seen | want to see | the worst | bad | whatever | not my thing | good | great | favorite | masterpiece

now..... i hate jerry lewis and i hate martin scorsese, so i haven't seen this one. hear me out! this film is in my 1001 films you must see before you die book, so i will watch it eventually. but will i like it? i'm going in with good intentions, we'll see. but i will say that i find this one to be a really intriguing one and of the scorseses i haven't seen, this is like one of two that i'm most excited to like. pick up and watch eventually.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hallucinatory 1967 Soviet horror film,(first Soviet-era horror film to be officially released in the USSR) VIY, directed by Konstantine Yershov and George Kropachyov.

Based on the classic novella by Nikolai Gogol – and previously adapted by Mario Bava as BLACK SUNDAY – the first horror film ever produced in the Soviet Union remains “genuinely frightening” (1001 Films You Must See Before You Die), “a visual grab bag of terror” (FilmInquiry.com) and “one of the best horror films of all time.” (IndieWire): In 19th century Russia, a seminary student is forced to spend three nights with the corpse of a beautiful young witch. But when she rises from the dead to seduce him, it will summon a nightmare of fear, desire and the ultimate demonic mayhem. Bursting with startling imagery and stunning practical effects by directors Konstantin Yershov and Georgi Kropachyov, this “overlooked classic” (Paste Magazine) has influenced generations of directors for more than half a century and is still unlike any horror movie you’ve ever seen.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello! In short, this blog will be tracking my attempt to watch all the movies that have ever been on the ‘1001 movies you must see before you die’ list, as much as possible in chronological order by release. As of now there are 1245 movies total in this category. I’ll watch specific movies out of order when there’s a opportunity for it (like doing it with friends, at an event etc) or I’m interested in watching it, because otherwise I think I will actually go insane, but aside from that I’ll try to generally watch a lot of the list in chronological order.

In long, I wasn’t a huge movie watcher for most of my life and only started to get more into it in the last 5 years or so, and I’ve gotten increasingly interested in it as a medium but I’m still not very “well read”. It’s also only in the past year that I first started to watch and get interested in older movies (like pre 1970s), due to having friends that liked them and a film class I took. I decided I wanted to watch a lot more movies from throughout history and study the medium a lot more, but it wasn’t until I stumbled across @891movies ‘s blog that I learned more about the 1001 movies list and the community of people that try to watch all of them, and also that because there’s different editions of the list there’s actually 1245 total movies that have been on the list at any point. What a scam. Anyway, as a relatively newbie movie watcher, the natural conclusion was to immediately decide to try to do this too as a way to watch a lot more movies and learn about the medium. No way you’ll escape from watching 1200 movies alive without knowing about film history!

However, that wasn’t crazy enough for me. Partly due to the influence of my friend @everybatman69 who decided to try to read every batman comic published from the beginning in chronological order, I somewhat hubristically went, “hey, you know what would be cool? If I tried to watch the 1245 movies all in chronological order.” Just because I think watching through all those movies in linear order and seeing the development and change in trends of film kind of in “real time” would be fascinating and really cool from a historical perspective.

This is, notably, the EXACT OPPOSITE of what most people giving advice on watching the 1001 movies list tell you to do- ie, that it’s a lot easier to maintain interest and morale in the project if you mix it up and watch things from different eras and styles all the time so you don’t get tired of it. Which, yeah that is pretty sensible I must admit. Still, I’m curious about how doing it this way will go anyway. Like I said above, to make this easier I definitely will watch individual movies out of order if I’m interested in them or the opportunity presents itself because I think this project would drive me crazy otherwise, and also it would totally suck to have to wait ten years before I get to watch movies I want to watch. Honestly I’m willing to be pretty lenient on this depending on how difficult it ends up being- I don’t mind if I watch a lot of movies out of order, just as long as there’s still a significant part of the list that I watch in order and can see the progression there. I’ll also leave the possibility open that I can axe the chronological order thing entirely down the road if I’m really struggling with it.

I plan to write reviews on here of every movie I watch for the project. I’ll also have “bonus” reviews for extra movies that I’m interested in and decided to basically insert into the 1001 list to watch as well in its respective time period (as if the list wasn’t already long enough, eugh). Also maybe reviews of random other movies I watch and movie talk in general? Idk we’ll see.

Anyway, my starting line is that I’ve currently watched 46 movies out of 1245. (Yeesh.) Strictly speaking there’s another 40 odd movies that I’ve technically watched, but they were so long ago or when I was young enough that I don’t remember much about them, so I decided to just count them as not being watched and I’ll rewatch them. So since there’s not that many of them, I’ll write short reviews for everything I’ve already watched first, with full reviews for a couple of them that I have more to say about. After that we can get this show on the road.

You may imagine that this project will take me a long time. Like, really long. If I watch one movie a week, this project will take me 23 years to finish. That’s fine. The journey’s more important than the destination in this. I’m just here to watch some movies and have a good time.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 11 Best Summer Horror Movies of All Time

What better way to beat the dog days of summer than hiding away inside, cranking the AC, and watching a horror flick? That’s why we put together a list of our favorite summer horror movies of all time. But just to clarify, by “summer horror movies” we mean movies that take place during the summer.

That means some “summer-ish” films — such as Cabin Fever (October) and Cabin in the Woods (weekend getaway) — aren’t eligible for the list. We also require summertime to be explicitly mentioned in the film, so that knocks 2 of our Mia Goth favorites, X and its sequel Pearl, out of contention. We’ve also excluded comedy horror flicks, so you won’t find The Final Girls lurking around here.

Without further ado, here are our favorite summer horror movies of all time.

#11: The Girl Next Door (2007)

This is not to be confused with the romantic comedy starring Emile Hirsch and Elisha Cuthbert from 2004. Not at all. Also known as Jack Ketchum’s Evil, The Girl Next Door is based on the multi-Stoker Award winner’s novel of the same name, which was itself loosely based on the true-life story of Sylvia Likens.

Without giving too much away, 2 recently orphaned sisters are sent to live with their aunt Ruth and her 3 sons. Very quickly, the older sister becomes persona non grata in Ruth’s eyes and is sent (or rather, sentenced) to live in the basement. Horrific things happen from there.

Stephen King called it “the dark-side-of-the-moon version of Stand By Me.” But even with the Master of Horror’s stamp of approval, it’s still one of the most divisive movies around, with as many 10-star ratings as 1-stars on IMDb.

Whether you love it or hate it, the only way to find out is by watching it. The first hour and 15 minutes are disturbing, but the final quarter-hour is downright horrifying. Still, it’s nothing compared to the real-life story behind it.

Where to stream it:

Prime Video

FASTs: Freevee, Tubi

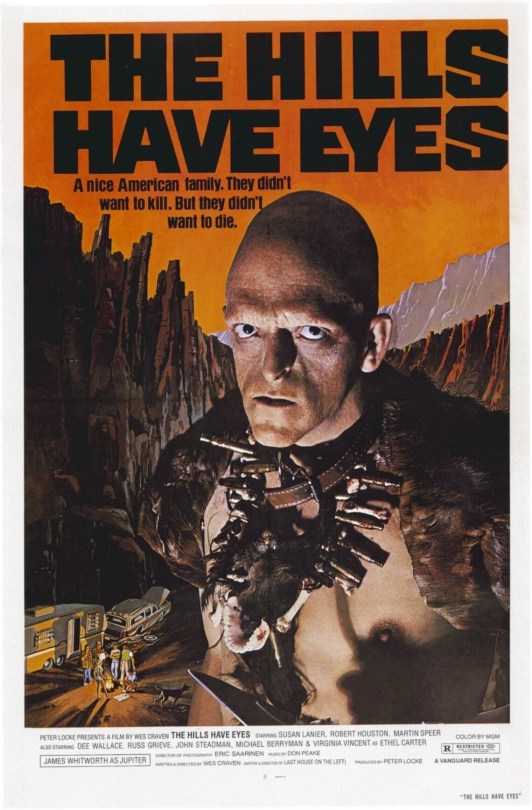

#10: The Hills Have Eyes (1977)

The sophomore directorial effort by legendary horror director Wes Craven cemented his name — and filmmaking future — in the horror genre.

Based on the legend of Scotsman Sawney Bean and his merry band of cannibals, a suburban family’s California road trip is sidetracked by a clan of Nevada flesh-eaters.

Made on a shoestring budget of somewhere between $350k to $700k, it went on to make $25 million. Full of chills, thrills, and dark humor, the movie became a cult classic and was even included in Steven Jay Schneider’s 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die (hopefully not on somebody’s dinner plate).

Pop it up on the screen for those in the backseat during your next summer road trip. It might be a good way to stop them from asking “Are we there yet?”

Where to stream it:

AMC+, Arrow, Screambox, Shudder

#9: Sleepaway Camp (1983)

Ask almost any horror fan and they’ll tell you that Sleepaway Camp is one of the classic summer camp slashers. Starring scream queen Felissa Rose, it’s got one of the greatest endings in movie history — which is all we’re going to say about that.

Aside from the ending, it’s notable for a cast mostly comprised of actual teenagers, rather than twentysomethings (or even thirtysomethings!) pretending to be young.

While not the most renowned horror franchise of all time, it spawned 4 sequels. Only one of them involved the original’s writer/director, Robert Hiltzik — who didn’t even know the others existed or that his film had become a cult classic! How’s that for a twist?

Where to stream it:

Fubo, Peacock, Screambox

#8: I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997)

Jennifer Love Hewitt leads a cast of beautiful people in low-cut, tight tees as they try to figure out who knows, uh, what they did last summer. And that’s not referring to where they went for vacation. It’s the deadly hit-and-run the group of then high schoolers covered up.

Loosely based on the YA novel of the same name by Lois Duncan, IKWYDLS has all the right ingredients for a summer slasher. Attractive, young cast? Check. A secret collective guilt? Check. Mysterious villain? Check. That’s probably why it’s the 7th highest-grossing slasher of all time.

Two forgettable sequels followed, and a third “legacy” sequel is reportedly in the works. But with no release date yet, you probably have at least one more summer to watch the original.

Where to stream it:

Hulu, MGM+

#7: Summer of 84 (2018)

Possibly (or likely) taking some inspiration from 1985’s classic horror film Fright Night, 15-year-old Davey suspects that his neighbor is a serial killer. Of course, Davey also digs conspiracy theories, so he gets a bit of the Boy-Who-Cried-Wolf treatment until he coughs up a bit more proof.

The film captures the feel and essence of the 1980s as well as any episode of Stranger Things and is a commendable homage to the horror movies of that time. It’s not surprising that it made many year-end lists in 2018.

The Summer of 84 is essential viewing for horror fans from June to September.

Where to stream it:

AMC+, Shudder

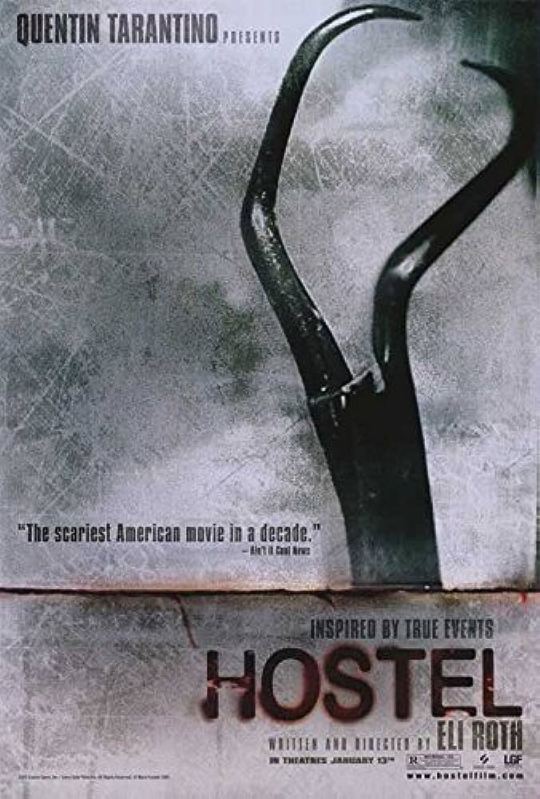

#6: Hostel (2005)

Hold on to your backpack. And your lunch.

In his follow-up to his Cabin Fever debut, director Eli Roth does for backpacking what Jaws did for beachgoing. Or at least tries his damnedest. When a trio of college friends traveling across Europe arrive in Slovakia, they soon wish they’d splurged for a room at the Marriott.

Instead of room service or a dip in the pool, our intrepid travelers end up on the wrong side of a torture chamber glory hole for depraved plutocrats.

Roth’s sophomore effort is reputedly the first to be called “torture porn”, although Hostel is hardly the first film to fit that bill. But fit the bill it does.

Where to stream it:

Hostel is apparently taking a break from paid streaming services at this time (August 2023).

#5: Friday the 13th (1980)

While the question of which Friday the 13th film is the franchise’s best is a hotly debated topic, they all don’t take place during the summer. But that doesn’t matter, because the first one does, and that’s our top pick anyway.

Before the hockey mask. Even before the unkillable man himself. This is where it all started. (And was one of Kevin Bacon’s first movies roles.)

It may not hold up as well visually as another old horror flick ranked higher on this list, but the Jason-less horror remains a classic for reason. Not only did it explicitly establish the have-sex-and-die slasher trope, but that first time at Camp Crystal Lake put summer camp massacres on the cinematic map.

Where to stream it:

Paramount+ (Apple TV Channel only)

#4: It (2017)

Commonly referred to as It Chapter One, — probably to avoid confusion with the 1990 miniseries It starring Tim Curry — It is the highest-grossing horror film of all time. And with all due respect to the fabulous Mr. Curry — and an impressive first adaptation of King’s 1,000-page tome — It is better than It.

The movie starts on a rainy day in October and immediately tells the viewer this ain’t no made-for-TV miniseries. Fast forward to the following June, and 13-year-old Bill enlists his friends to help him correct the mistakes of his past — and fight a primordial, extraterrestrial evil shapeshifter that materializes as your greatest fear.

Stephen King wasn’t consulted on the film, as he has been with many film adaptations of his oeuvre, but he evidently loves it:

Where to stream it:

Unfortunately, It is not currently available on streaming services. However, you can grab a digital rental for $4 at all the usual places.

#3: Midsommar (2019)

Midsommar is director Ari Aster’s sophomore feature film — after Hereditary — and you couldn’t ask for a better follow-up.

Similar to a movie 3 spots down our list, a group of American college kids join their European schoolmate on his home turf during the summer break.

Heading to a commune for a midsummer festival in the idyllic Swedish countryside starts out wonderfully — except for the fact that one of the guy’s brought his girlfriend along. They even get a bunch of free mushrooms, which is great until said girlfriend has a bad trip.

It’s an A24 film, so obviously things are going to get messed up. And boy, do they. Then you’re left watching the rest of the film with your jaw hanging open.

Granted, it’s not loved by all — dividing both viewers and critics — so some may take umbrage with it ranking so high on our list. But we call ’em like see ’em.

Where to stream it:

Paramount+, DirecTV Stream

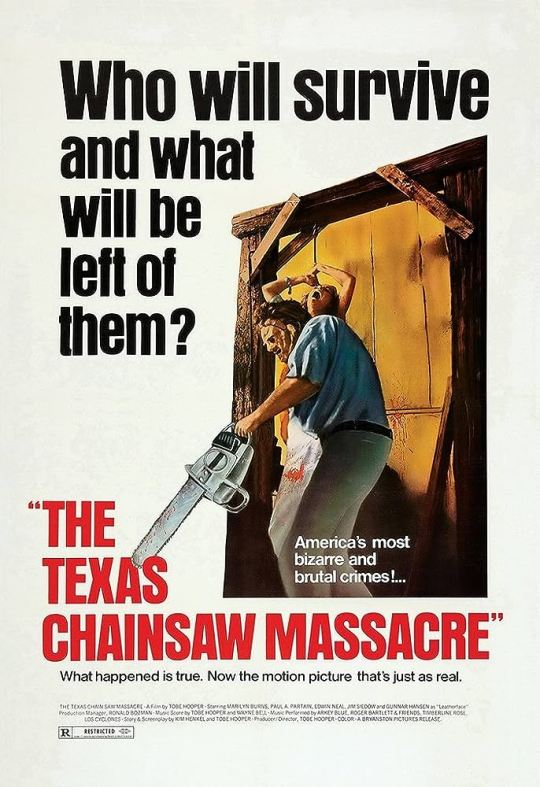

#2: The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)

When watching old movies, it helps to imagine being in the audience of the day. Only then can you truly appreciate when a film is doing something innovative or pushing the bounds of the norm.

And The Texas Chainsaw Massacre did exactly that. In his contemporaneous review, Roger Ebert gave the film 2 stars and a thumbs up but didn’t enjoy it.

It’s also without any apparent purpose, unless the creation of disgust and fright is a purpose. And yet in its own way, the movie is some kind of weird, off-the-wall achievement. I can’t imagine why anyone would want to make a movie like this, and yet it’s well-made, well-acted, and all too effective.

The landmark horror film has been given the 4K UHD remaster treatment at least twice, and both look fantastic. Certainly good enough to mollify those viewers who don’t like watching “old-looking” old movies.

Not only that, the movie itself holds up just fine after (almost) 50 years. That’s no small achievement, as there aren’t too many films that can deliver scares to multiple generations.

Where to stream it:

Peacock, Shudder, Screambox

#1: Jaws (1975)

While this may come as a surprise to some, as Jaws is not your typical murder-filled horror film. Some may prefer to call it a thriller, or even an action or adventure movie. And sure, why can’t it be all of them? But what’s more horrific than a primordial beast invisibly lurking in the shadows until it strikes?

Horror film: …the representation of disturbing and dark subject matter, seek to elicit responses of fear, terror, disgust, shock, suspense, and, of course, horror from their viewers.

And who can forget that music? You can still hear people mimicking it today in swimming pools around the world. Without a doubt, the inimitable John Williams is as much to thank for the horror of Jaws as Spielberg.

No other horror movie — or perhaps movie in general — in the history of cinema has had such an impact on people’s actual lives. People were so afraid to go in the ocean that beach tourism declined in 1975. How many films can say that?

Where to stream it:

DirecTV Stream

FASTs: Tubi

Which streaming service has the most summer horror movies?

When it comes to paid streaming services (and therefore ad-free with the right plan), it’s a dead heat between 5 streamers. AMC+, Parmount+, Peacock, Shudder, and DirecTV all have 2 movies on our list. Hulu, Prime Video, and Screambox each have 1 movie.

However, when it comes to the best overall — including free ad-supported television (FAST) services — Freevee takes the top spot with 4 films. Tubi and Plex tie for second with 3 movies each.

What perhaps surprised us the most was that Max has none of the films on our list. It’s usually a solid choice when it comes horror.

What’s the “most popular” summer horror movie on streaming?

The most popular summer horror movie — ie: the one on the most platforms — is Sleepaway Camp, which is streaming on 9 of the 25 services we counted. The second-most popular summer horror movie is The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, which is available on 8 streaming services. And coming in a distant third — with only 3 platforms — is Hostel, which is only available on FASTs.

💀 Do you see a glaring omission from our list? What’s your favorite summer horror movie? Let us know in the comments below.

👀 And in the meantime, check out our Paramount Review, Peacock Review, and DirecTV Stream Review, to see if one of them suits your needs.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

now granted this is just my experience, of course, but it feels like a lot of favorites list or best of games lists aren't being made by people who look at games as art, but as business ventures. this game changed the course of history by selling a gazillion copies! like is that really the metric by which youre basing your personal opinion? it's not even money you made. those kinds of lists always remind me of the 1001 movies you must see before you die type books. they start out w historically sifnificant films, and then to genre-defining film, and end w films that just make a shitton of money. we have such little time on this earth, you want me to spend it watching marvel films bc they made a lot of money? i appreciate more the lists that are at least honest. "this game is the best because it was fun to play" may not sound complex, but at least it's genuine.

see a lot of #gamer lists suck to me bc it's always like "my top 100 games" and there's like 40 marios and 35 zeldas every souls game and specifically silent hill 2

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1977, having finished up Angel City, despite its intended shoot period of 6 weeks stretching to nearer 8 months owing to my Laurel Canyon incident which limited my capacity to work to a day or two a week, and then a stay in traction in a hospital in La Jolla, I decided to make another film, and corresponded with a friend from my years in Kalispell, Tom Blair. He was an actor from South Dakota, and ran the Whitefish Community College Theater Dept. I had never seen him act (probably fortunately), but instead would hang around drinking beer and smoking dope with him. On deciding to make a film I contacted him and we had a long-distance correspondence vaguely sketching out an idea. I went up to Montana for a week of recon, lining up some actors, and went back to LA. I wrote a few scenes, and going to Montana a friend, copy writer by profession, Peter Trias went with me. He wrote a bit when we got there.

The Edinburgh Festival had already invited Angel City, and with nothing shot in June I promised them a new film for the festival. I went back to Missoula and the actors met with me there. Last Chants was shot in 5 days. I recorded some of the songs in it in Missoula, and returned to LA, to process the film and edit, and record 2 more songs. By mid-August it was done, for a cost of $3000. I went to Edinburgh with it and Angel City. It made a nice splash, got press in Sight & Sound, and it seems I was seriously on my way in the far edges of the film biz.

In some quarters Last Chants is now considered an American classic; Jonathan Rosenbaum lists it as one of the best 100 films ever, and it is listed in the book 1001 Films You Must See Before You Die.

LAST CHANTS FOR A SLOW DANCE (Dead End)

1977, 16mm color/snd, 90 minutes

Produced, written, directed, photographed and edited by Jon Jost.

Additional writing by Peter Trias

With Tom Blair, Steven Voorheis, Jessica St. John, Wayne Crouse, Mary Vollmer, John Jackson

Edinburgh Festival, 1977, Toronto 1978, Florence, 1979, Sydney, and others

Collections of BFI, Australian Film Institute Broadcast by UK’s C4, 1981

A terminal “road-movie,” Last Chants single-mindedly follows the path of its central character, Tom Bates, through an unspecified period of time as he talks to a hitch-hiker and then throws him out of his truck, visits his wife and has a fierce argument with her, talks to a man in a breakfast cafe, picks up a woman in a bar and has a one night stand with her; leaves the woman, and cruising in his truck on a back road, pulls over to help a man with his broken-down car, and shoots and kills the man, for a few dollars.

Critics comments:

“Last Chants for a Slow Dance is a film of extraordinary restraint and formal elegance – a paradox which provides an exceptionally telling indication of the nature of Jost’s attitude to film.”

Alan Sutherland, Sight and Sound

“Watching Last Chants is a disconcerting experience, the harrowing intensity of the long takes almost aggressively unpleasant, the final murder almost self-consciously “unmotivated.” But the very absence of a reassuring sense of conventional motivation – and therefore order – is essential to a film about a man totally disconnected from his surroundings, his numbness preventing him from doing more than passing through the action, with the power to change nothing, to feel nothing, to understand nothing.”

David Coursen, Film Quarterly

“It is tempting to say that Last Chants is remarkable enough in its own terms but, remarkable though it certainly is, that would seriously underestimate the film’s importance. For Last Chants does what virtually no other film made in the USA in the 70’s does — it exemplifies the possibility of a radical alternative cinema, radical and alternative in economic, aesthetic and political terms — which does not inevitably condemn itself in advance to an avant-garde elitist or otherwise narrow audience. One of the primary reasons it is able to do so is that it draws fundamentally upon cinema’s narrative tradition, incorporating some of its pleasure and fascination, while seeking to sever that narrative tradition from its accumulated ideological functions and disguises.”

Jim Hillier, Movie, 1981

Theo Sez (do not know source) :

Still can’t believe I saw some of the stuff in this haunting mood-piece (my first exposure to a fascinating film-maker) : our hero and a one-night-stand he’s picked up in a bar ascending the staircase to her place, only what we see as they clamber up the stairs aren’t people but weirdly corporeal shadows, laughing and talking like people ; a later shot split into the hero and woman making love on one side and a TV blaring on the other, our attention drawn shamefully but inevitably to the TV – which then (somehow) keeps blaring even when the woman walks in front of it, the image projected on her body ; frequent momentary flickers of colour, the film turning red or green for a split second, or else picture fading to black while a conversation continues, or a black-and-white shot with a bright-red neon sign flickering in a corner (how do they do that?), or a drab urban image suddenly followed by a piercingly beautiful shot of clouds at dawn, or (my favourite) a strangely affecting shot of landscapes whizzing past the window of a moving car to the accompaniment of random static (an artist’s impression of the background rush of wind we hear crowding through the window in a silent car). Film-as-Art, obviously, less about the (skeletal) narrative than Jost’s artistry in making each image interesting (even on a so-so video transfer), building a powerful atmosphere of restless alienation – but it’s not just about the aesthetics, linking to a sense of underclass rage, what it means to go through life with a soul-destroying job or no job at all (as in something like HENRY: PORTRAIT OF A SERIAL KILLER, mental breakdown mirrors social disenfranchisement). The film’s strength is the melding of form and content, Blair’s anti-hero tumbling between lassitude and sharp, funny rants (his incongruously nasal laugh is very effective) just as the film shifts between miserablism and visual legerdemain, Jost’s camera passively observing then darting neurotically through a crowded space, trying in vain to make sense of it : the film seems designed to approximate a mind on the edge (teasingly offset by the resigned, lulling rhythms of country-and-Western music). Its limitation is the way form becomes content, stifling any sense of independent narrative (you might say the film-maker is too strong for his own movie), making the ending a mild disappointment as well as a reminder the film was – unfortunately, in my opinion – inspired by the life of Gary Gilmore ; the whole banality-of-Evil thing seems, well, banal, unworthy of the endlessly suggestive dead-endness (“Dead End” is indeed the sub-title) ; otherwise a revelation, making you wonder about the neglected career of a clearly major film-maker. Is it too late to rehabilitate Jost as he heads into his 60s?…

For more of my thoughts on the film see this.

https://vimeo.com/ondemand/121001

Last Chants for a Slow Dance In 1977, having finished up Angel City, despite its intended shoot period of 6 weeks stretching to nearer 8 months owing to my Laurel Canyon incident which limited my capacity to work to a day or two a week, and then a stay in traction in a hospital in La Jolla, I decided to make another film, and corresponded with a friend from my years in Kalispell, Tom Blair.

#1001 Films You Must See Before You Die#Edinburgh Film Festival#Film Quarterly#Jonathan Rosenbaum#Sight & Sound#Tom Blair

0 notes

Text

finally watched avengers: endgame and i have thoughts. nothing i’m about to say is new but i just need to get this out so i can stop thinking about this movie

this movie is so ugly to look at. so much of it looks like a video game cutscene; you can feel the weightlessness of the cgi and it makes you feel less invested in the action.

the action is also poorly staged. i’m no expert by any means but a lot of it was confusing and difficult to watch, not helped by the screen being so damn dark. the lotr trilogy pulled these epic battles off much better 20 years ago, there’s no excuse.

the characters are massacred all around. since the characters are the only thing that ever drew me to the mcu to start with, this is a problem.

even tony, who is treated with a lot of (imo) unearned reverence, still gets screwed by poor character continuity. he’s had to learn the same lesson about how being a hero requires selflessness/sacrifice in like three separate movies now. it doesn’t help that this is rdj’s worst performance in any of these films so far, you can really tell he’s looking towards the exit

i can’t think about steve’s ending without getting pissed off. i think this might be the worst way they could have possibly ended his story? and they sloppily try to justify it by completely rewriting his character trajectory in this movie. just bad decisions all around

nat’s death was stupid and they should feel bad. clint was so very much the obvious choice to sacrifice himself for the soul stone, if we even had to have that stupid plot point. even if they wanted to do the bait and switch ‘oh you think one of them’s gonna die but it’s actually the other one’, you could have had nat arguing more passionately that she’s doing this so clint can reunite with his family and then have clint beat her to the jump with a whole ‘redemption through sacrifice’ moment (because he needed to be redeemed after the first half of that movie and he isn’t really).

the stupidity of nat’s death is even more obvious when you show the characters talking about her after and it’s just a room full of men. really drives home why she was considered the most expendable avenger

thor’s story i feel like could have worked if it didn’t rely so much on fat jokes. but i still think the trajectory they took in infinity war, effectively erasing all the good work ragnarok did, was stupid in the first place.

the time travel plot felt like an excuse for cheap sentimentality and fan service. when they had like three characters meet dead loved ones in quick succession i wanted to laugh. and they literally just reshow some well known shots from older movies, no new footage needed.

all of the mcu women gathering on the battlefield felt like a cheap ploy for some unearned praise. you know, since they’re so progressive for including so many badass female characters in their movies when most of them haven’t been developed beyond being side characters in men’s stories.

the way ‘five years later’ faded in one word at a time pissed me off so much i groaned out loud. you could feel the decision making process behind it, the gasps they were hoping to elicit from the audience. you know when scorcese said these movies aren’t cinema, they’re theme park attractions? he might have been talking about this exact moment (i don’t agree with that take but endgame was doing its best to convince me otherwise)

you know, the reason it took me three years to watch this movie is that i was so burnt out on the mcu after infinity war that i didn’t feel like watching another marvel movie. so i didn’t, until now. and i probably never would have gotten around to endgame if not for my mission to watch every movie from ‘1001 movies you must see before you die’. now that i have watched it? possibly the second worst time i’ve had watching a movie from that list (nothing is topping saló).

#wank for ts#i know i'm three years late to the party but i just had to get this out#this is rant-y and poorly worded but at least i've expelled all of it now#and i can go back to never thinking about the mcu anymore#except when i feel like reading the occasional stucky fic lmao

54 notes

·

View notes

Note

i never heard of that movie so i looked it up and who gives a shit if the movie was directed by a woman when its nazi propaganda???????? im so confused what the fuck i hate goyim so brain dead its crazy

the fact that it has enough ppl rating it high to have a 3.0 on letterboxd, the fact that its on so many "canon" lists like eberts "Great films", 1001 movies to see before you die, etc its fucking crazy like i truly dont understand how these people can in good faith do that shit. its actually quite fucking easy to let the film itself die. sure talk about it in terms of its historical significance but to declare it "great" or a "must watch" or "women filmmaker!!!!!!!!!!!!" its like.... its so beyond aggravating to me lol. god

and sorry in hindsight i shouldve warning tagged it for nazism thats my bad

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ida Lupino (4 February 1918 – 3 August 1995) was an English-American actress, singer, director, and producer. She is widely regarded as the most prominent female filmmaker working in the 1950s during the Hollywood studio system. With her independent production company, she co-wrote and co-produced several social-message films and became the first woman to direct a film noir with The Hitch-Hiker in 1953. Among her other directed films the best known are Not Wanted about unwed pregnancy (she took over for a sick director and refused directorial credit), Never Fear (1949) loosely based upon her own experiences battling paralyzing polio, Outrage (1950) one of the first films about rape, The Bigamist (1953) (which was named in the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die) and The Trouble with Angels (1966).

Throughout her 48-year career, she made acting appearances in 59 films and directed eight others, working primarily in the United States, where she became a citizen in 1948. As an actress her best known films are The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1939) with Basil Rathbone, They Drive by Night (1940) with George Raft and Humphrey Bogart, High Sierra (1941) with Bogart, The Sea Wolf (1941) with Edward G. Robinson and John Garfield, Ladies in Retirement (1941) with Louis Hayward, Moontide (1942) with Jean Gabin, The Hard Way (1943), Deep Valley (1947) with Dane Clark, Road House (1948) with Cornel Wilde and Richard Widmark, While the City Sleeps (1956) with Dana Andrews and Vincent Price. and Junior Bonner (1972) with Steve McQueen.

She also directed more than 100 episodes of television productions in a variety of genres including westerns, supernatural tales, situation comedies, murder mysteries, and gangster stories. She was the only woman to direct an episode of the original The Twilight Zone series ("The Masks"), as well as the only director to have starred in an episode of the show ("The Sixteen-Millimeter Shrine").

Lupino was born in Herne Hill, London, to actress Connie O'Shea (also known as Connie Emerald) and music hall comedian Stanley Lupino, a member of the theatrical Lupino family, which included Lupino Lane, a song-and-dance man. Her father, a top name in musical comedy in the UK and a member of a centuries-old theatrical dynasty dating back to Renaissance Italy, encouraged her to perform at an early age. He built a backyard theatre for Lupino and her sister Rita (1920–2016), who also became an actress and dancer. Lupino wrote her first play at age seven and toured with a travelling theatre company as a child. By the age of ten, Lupino had memorised the leading female roles in each of Shakespeare's plays. After her intense childhood training for stage plays, Ida's uncle Lupino Lane assisted her in moving towards film acting by getting her work as a background actress at British International Studios.

She wanted to be a writer, but in order to please her father, Lupino enrolled in the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. She excelled in a number of "bad girl" film roles, often playing prostitutes. Lupino did not enjoy being an actress and felt uncomfortable with many of the early roles she was given. She felt that she was pushed into the profession due to her family history.

Lupino worked as both a stage and screen actress. She first took to the stage in 1934 as the lead in The Pursuit of Happiness at the Paramount Studio Theatre.[10] Lupino made her first film appearance in The Love Race (1931) and the following year, aged 14, she worked under director Allan Dwan in Her First Affaire, in a role for which her mother had previously tested.[11] She played leading roles in five British films in 1933 at Warner Bros.' Teddington studios and for Julius Hagen at Twickenham, including The Ghost Camera with John Mills and I Lived with You with Ivor Novello.

Dubbed "the English Jean Harlow", she was discovered by Paramount in the 1933 film Money for Speed, playing a good girl/bad girl dual role. Lupino claimed the talent scouts saw her play only the sweet girl in the film and not the part of the prostitute, so she was asked to try out for the lead role in Alice in Wonderland (1933). When she arrived in Hollywood, the Paramount producers did not know what to make of their sultry potential leading lady, but she did get a five-year contract.

Lupino starred in over a dozen films in the mid-1930s, working with Columbia in a two-film deal, one of which, The Light That Failed (1939), was a role she acquired after running into the director's office unannounced, demanding an audition. After this breakthrough performance as a spiteful cockney model who torments Ronald Colman, she began to be taken seriously as a dramatic actress. As a result, her parts improved during the 1940s, and she jokingly referred to herself as "the poor man's Bette Davis", taking the roles that Davis refused.

Mark Hellinger, associate producer at Warner Bros., was impressed by Lupino's performance in The Light That Failed, and hired her for the femme-fatale role in the Raoul Walsh-directed They Drive by Night (1940), opposite stars George Raft, Ann Sheridan and Humphrey Bogart. The film did well and the critical consensus was that Lupino stole the movie, particularly in her unhinged courtroom scene. Warner Bros. offered her a contract which she negotiated to include some freelance rights. She worked with Walsh and Bogart again in High Sierra (1941), where she impressed critic Bosley Crowther in her role as an "adoring moll".

Her performance in The Hard Way (1943) won the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actress. She starred in Pillow to Post (1945), which was her only comedic leading role. After the drama Deep Valley (1947) finished shooting, neither Warner Bros. nor Lupino moved to renew her contract and she left the studio in 1947. Although in demand throughout the 1940s, she arguably never became a major star although she often had top billing in her pictures, above actors such as Humphrey Bogart, and was repeatedly critically lauded for her realistic, direct acting style.

She often incurred the ire of studio boss Jack Warner by objecting to her casting, refusing poorly written roles that she felt were beneath her dignity as an actress, and making script revisions deemed unacceptable by the studio. As a result, she spent a great deal of her time at Warner Bros. suspended. In 1942, she rejected an offer to star with Ronald Reagan in Kings Row, and was immediately put on suspension at the studio. Eventually, a tentative rapprochement was brokered, but her relationship with the studio remained strained. In 1947, Lupino left Warner Brothers and appeared for 20th Century Fox as a nightclub singer in the film noir Road House, performing her musical numbers in the film. She starred in On Dangerous Ground in 1951, and may have taken on some of the directing tasks of the film while director Nicholas Ray was ill.

While on suspension, Lupino had ample time to observe filming and editing processes, and she became interested in directing. She described how bored she was on set while "someone else seemed to be doing all the interesting work".

She and her husband Collier Young formed an independent company, The Filmakers, to produce, direct, and write low-budget, issue-oriented films. Her first directing job came unexpectedly in 1949 when director Elmer Clifton suffered a mild heart attack and was unable to finish Not Wanted, a film Lupino co-produced and co-wrote. Lupino stepped in to finish the film without taking directorial credit out of respect for Clifton. Although the film's subject of out-of-wedlock pregnancy was controversial, it received a vast amount of publicity, and she was invited to discuss the film with Eleanor Roosevelt on a national radio program.

Never Fear (1949), a film about polio (which she had personally experienced replete with paralysis at age 16), was her first director's credit. After producing four more films about social issues, including Outrage (1950), a film about rape (while this word is never used in the movie), Lupino directed her first hard-paced, all-male-cast film, The Hitch-Hiker (1953), making her the first woman to direct a film noir. The Filmakers went on to produce 12 feature films, six of which Lupino directed or co-directed, five of which she wrote or co-wrote, three of which she acted in, and one of which she co-produced.

Lupino once called herself a "bulldozer" to secure financing for her production company, but she referred to herself as "mother" while on set. On set, the back of her director's chair was labeled "Mother of Us All".[3] Her studio emphasized her femininity, often at the urging of Lupino herself. She credited her refusal to renew her contract with Warner Bros. under the pretenses of domesticity, claiming "I had decided that nothing lay ahead of me but the life of the neurotic star with no family and no home." She made a point to seem nonthreatening in a male-dominated environment, stating, "That's where being a man makes a great deal of difference. I don't suppose the men particularly care about leaving their wives and children. During the vacation period, the wife can always fly over and be with him. It's difficult for a wife to say to her husband, come sit on the set and watch."

Although directing became Lupino's passion, the drive for money kept her on camera, so she could acquire the funds to make her own productions. She became a wily low-budget filmmaker, reusing sets from other studio productions and talking her physician into appearing as a doctor in the delivery scene of Not Wanted. She used what is now called product placement, placing Coke, Cadillac, and other brands in her films, such as The Bigamist. She shot in public places to avoid set-rental costs and planned scenes in pre-production to avoid technical mistakes and retakes. She joked that if she had been the "poor man's Bette Davis" as an actress, she had now become the "poor man's Don Siegel" as a director.

The Filmakers production company closed shop in 1955, and Lupino turned almost immediately to television, directing episodes of more than thirty US TV series from 1956 through 1968. She also helmed a feature film in 1965 for the Catholic schoolgirl comedy The Trouble With Angels, starring Hayley Mills and Rosalind Russell; this was Lupino's last theatrical film as a director. She continued acting as well, going on to a successful television career throughout the 1960s and '70s.

Lupino's career as a director continued through 1968. Her directing efforts during these years were almost exclusively for television productions such as Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Thriller, The Twilight Zone, Have Gun – Will Travel, Honey West, The Donna Reed Show, Gilligan's Island, 77 Sunset Strip, The Rifleman, The Virginian, Sam Benedict, The Untouchables, Hong Kong, The Fugitive, and Bewitched.

After the demise of The Filmakers, Lupino continued working as an actress until the end of the 1970s, mainly in television. Lupino appeared in 19 episodes of Four Star Playhouse from 1952 to 1956, an endeavor involving partners Charles Boyer, Dick Powell and David Niven. From January 1957 to September 1958, Lupino starred with her then-husband Howard Duff in the sitcom Mr. Adams and Eve, in which the duo played husband-and-wife film stars named Howard Adams and Eve Drake, living in Beverly Hills, California.[22] Duff and Lupino also co-starred as themselves in 1959 in one of the 13 one-hour installments of The Lucy–Desi Comedy Hour and an episode of The Dinah Shore Chevy Show in 1960. Lupino guest-starred in numerous television shows, including The Ford Television Theatre (1954), Bonanza (1959), Burke's Law (1963–64), The Virginian (1963–65), Batman (1968), The Mod Squad (1969), Family Affair (1969–70), The Wild, Wild West (1969), Nanny and the Professor (1971), Columbo: Short Fuse (1972), Columbo: Swan Song (1974) in which she plays Johnny Cash's character's zealous wife, Barnaby Jones (1974), The Streets of San Francisco, Ellery Queen (1975), Police Woman (1975), and Charlie's Angels (1977). Her final acting appearance was in the 1979 film My Boys Are Good Boys.

Lupino has two distinctions with The Twilight Zone series, as the only woman to have directed an episode ("The Masks") and the only person to have worked as both actor for one episode ("The Sixteen-Millimeter Shrine"), and director for another.

Lupino's Filmakers movies deal with unconventional and controversial subject matter that studio producers would not touch, including out-of-wedlock pregnancy, bigamy, and rape. She described her independent work as "films that had social significance and yet were entertainment ... base on true stories, things the public could understand because they had happened or been of news value." She focused on women's issues for many of her films and she liked strong characters, "[Not] women who have masculine qualities about them, but [a role] that has intestinal fortitude, some guts to it."

In the film The Bigamist, the two women characters represent the career woman and the homemaker. The title character is married to a woman (Joan Fontaine) who, unable to have children, has devoted her energy to her career. While on one of many business trips, he meets a waitress (Lupino) with whom he has a child, and then marries her.[25] Marsha Orgeron, in her book Hollywood Ambitions, describes these characters as "struggling to figure out their place in environments that mirror the social constraints that Lupino faced".[13] However, Donati, in his biography of Lupino, said "The solutions to the character's problems within the films were often conventional, even conservative, more reinforcing the 1950s' ideology than undercutting it."

Ahead of her time within the studio system, Lupino was intent on creating films that were rooted in reality. On Never Fear, Lupino said, "People are tired of having the wool pulled over their eyes. They pay out good money for their theatre tickets and they want something in return. They want realism. And you can't be realistic with the same glamorous mugs on the screen all the time."

Lupino's films are critical of many traditional social institutions, which reflect her contempt for the patriarchal structure that existed in Hollywood. Lupino rejected the commodification of female stars and as an actress, she resisted becoming an object of desire. She said in 1949, "Hollywood careers are perishable commodities", and sought to avoid such a fate for herself.

Ida Lupino was diagnosed with polio in 1934. The New York Times reported that the outbreak of polio within the Hollywood community was due to contaminated swimming pools. The disease severely affected her ability to work, and her contract with Paramount fell apart shortly after her diagnosis. Lupino recovered and eventually directed, produced, and wrote many films, including a film loosely based upon her travails with polio titled Never Fear in 1949, the first film that she was credited for directing (she had earlier stepped in for an ill director on Not Wanted and refused directorial credit out of respect for her colleague). Her experience with the disease gave Lupino the courage to focus on her intellectual abilities over simply her physical appearance. In an interview with Hollywood, Lupino said, "I realized that my life and my courage and my hopes did not lie in my body. If that body was paralyzed, my brain could still work industriously...If I weren't able to act, I would be able to write. Even if I weren't able to use a pencil or typewriter, I could dictate."[31] Film magazines from the 1930s and 1940s, such as The Hollywood Reporter and Motion Picture Daily, frequently published updates on her condition. Lupino worked for various non-profit organizations to help raise funds for polio research.

Lupino's interests outside the entertainment industry included writing short stories and children's books, and composing music. Her composition "Aladdin's Suite" was performed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra in 1937. She composed this piece while on bedrest due to polio in 1935.

She became an American citizen in June 1948 and a staunch Democrat who supported the presidency of John F. Kennedy. Lupino was Catholic.

Lupino died from a stroke while undergoing treatment for colon cancer in Los Angeles on 3 August 1995, at the age of 77. Her memoirs, Ida Lupino: Beyond the Camera, were edited after her death and published by Mary Ann Anderson.

Lupino learned filmmaking from everyone she observed on set, including William Ziegler, the cameraman for Not Wanted. When in preproduction on Never Fear, she conferred with Michael Gordon on directorial technique, organization, and plotting. Cinematographer Archie Stout said of Ms. Lupino, "Ida has more knowledge of camera angles and lenses than any director I've ever worked with, with the exception of Victor Fleming. She knows how a woman looks on the screen and what light that woman should have, probably better than I do." Lupino also worked with editor Stanford Tischler, who said of her, "She wasn't the kind of director who would shoot something, then hope any flaws could be fixed in the cutting room. The acting was always there, to her credit."

Author Ally Acker compares Lupino to pioneering silent-film director Lois Weber for their focus on controversial, socially relevant topics. With their ambiguous endings, Lupino's films never offered simple solutions for her troubled characters, and Acker finds parallels to her storytelling style in the work of the modern European "New Wave" directors, such as Margarethe von Trotta.

Ronnie Scheib, who issued a Kino release of three of Lupino's films, likens Lupino's themes and directorial style to directors Nicholas Ray, Sam Fuller, and Robert Aldrich, saying, "Lupino very much belongs to that generation of modernist filmmakers." On whether Lupino should be considered a feminist filmmaker, Scheib states, "I don't think Lupino was concerned with showing strong people, men or women. She often said that she was interested in lost, bewildered people, and I think she was talking about the postwar trauma of people who couldn't go home again."

Author Richard Koszarski noted Lupino's choice to play with gender roles regarding women's film stereotypes during the studio era: "Her films display the obsessions and consistencies of a true auteur... In her films The Bigamist and The Hitch-Hiker, Lupino was able to reduce the male to the same sort of dangerous, irrational force that women represented in most male-directed examples of Hollywood film noir."

Lupino did not openly consider herself a feminist, saying, "I had to do something to fill up my time between contracts. Keeping a feminine approach is vital — men hate bossy females ... Often I pretended to a cameraman to know less than I did. That way I got more cooperation." Village Voice writer Carrie Rickey, though, holds Lupino up as a model of modern feminist filmmaking: "Not only did Lupino take control of production, direction, and screenplay, but [also] each of her movies addresses the brutal repercussions of sexuality, independence and dependence."

By 1972, Lupino said she wished more women were hired as directors and producers in Hollywood, noting that only very powerful actresses or writers had the chance to work in the field. She directed or costarred a number of times with young, fellow British actresses on a similar journey of developing their American film careers like Hayley Mills and Pamela Franklin.

Actress Bea Arthur, best remembered for her work in Maude and The Golden Girls, was motivated to escape her stifling hometown by following in Lupino's footsteps and becoming an actress, saying, "My dream was to become a very small blonde movie star like Ida Lupino and those other women I saw up there on the screen during the Depression."

Lupino has two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame for contributions to the fields of television and film — located at 1724 Vine Street and 6821 Hollywood Boulevard.

New York Film Critics Circle Award - Best Actress, The Hard Way, 1943

Inaugural Saturn Award - Best Supporting Actress, The Devil's Rain, 1975

A Commemorative Blue Plaque is dedicated to Lupino and her father Stanley Lupino by The Music Hall Guild of Great Britain and America and the Theatre and Film Guild of Great Britain and America at the house where she was born in Herne Hill, London, 16 February 2016

Composer Carla Bley paid tribute to Lupino with her jazz composition "Ida Lupino" in 1964.

The Hitch-Hiker was inducted into the National Film Registry in 1998 while Outrage was inducted in 2020.

#ida lupino#classic hollywood#classic movie stars#golden age of hollywood#old hollywood#1930s hollywood#1940s hollywood#1950s hollywood#1960s hollywood#1970s hollywood#hollywood legend

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here is the poll for what film list we should use next, as discussed in this post. Not all of the suggestions were used, as some suggested lists were either a bit too niche or too repetitive (too many movies of the same genre/type) to fit this blog. I still appreciate everyone who suggested one, though! Below the poll are the links to every list in question.

1001 Films You Must See Before You Die

The American Film Institute's "100 Years... 100 Movies - 10th Anniversary Edition"

IMDb Bottom 250

Rotten Tomatoes "100 Worst Movies of All Time"

Sight and Sound's Greatest Films of All Time 2022

List of Academy Award-nominated Films

Wikipedia's "List of films considered the worst"

Wikipedia's "List of highest-grossing films"

Winners & nominees of the Golden Raspberry Award for Worst Picture

Some of these lists have had a lot of their entries polled already, so if the winner of this poll ends up not lasting us too long then I will switch to the list in second place. Until this poll expires, every poll posted will be a request rather than from any list.

157 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Sculpting in Time.

As the world inches into the future, we invited Justine Smith, author of the ‘100 Films to Watch to Expand your Horizons’ list, to look to the cinematic past to help us process the present.

It is said that the essential quality of cinema that distinguishes it from other arts is time. Music can be played at different tempos, and standing in a museum, we choose how many seconds or hours we stand before a great painting. A novel can be savored or sped through. Cinema, on the other hand, exists on a fixed timeline. While it can theoretically be experienced at double or half speeds, it is never intended to be seen as such. Cinema’s fundamental quality is experiencing time on someone else’s terms. As the great Andrei Tarkovsky said in describing his work as a filmmaker, he was “sculpting in time”.

The perception of time, however, is not universal. Our moods, our emotions, and our ideologies shape our relationship to it. Most Western audiences are further acclimated to Western cinema’s ebbs and flows, which similarly favor efficiency and invisibility. When we see a Hollywood film, we don’t want the story to stop. We want to be swept away and forget that we are all moving towards a mortal endpoint. Cinema, though, in its infinite possibilities, exists far beyond these parameters. It can challenge and enrich our vision of the world. If we open ourselves up, we can transfigure and transform our relationship to time itself.

When I first put together my 100 Films to Watch to Expand your Horizons list, I did it quite haphazardly. I imagined countries, filmmakers and experiences that I felt went under-appreciated in discussions of cinema’s potential. Intuitively, I went searching for corners of experience that expanded my own cinematic horizon. Some of these films are well-loved and seen by wide audiences; others are virtually unknown. It was often only after the fact that the myriad of intimate connections between the films came to light.

Manuel de Oliveira’s ‘Visit, or Memories and Confessions’ (2015).

“The only eternal moment is the present.” —Manoel de Oliveira

Released in 2015 but made in 1982, Visit, or Memories and Confessions is a reflection on life, cinema and oppression by Portuguese filmmaker Manoel de Oliveira. If we were to reflect on cinema’s history, few filmmakers have the breadth of experience and foresight as Oliveira. His first film was made in the silent era using a hand-cranked camera. By the time of his death at 106 years of age, he had made dozens of movies, including many in a digital format.

He made Visit, or Memories and Confessions in the shadow of the Portuguese dictatorship. While filming, he imagined he was in the twilight of his life. It revisited essential incidents in his history but also that of his country. It’s a film of reconciliation, violence and oppression, told tenderly in a home lost as a consequence of a vindictive dictatorship. Oliveira’s film, like his life, spanned time in a way that stretches perceptions. It’s a film without significant incident, about the peaceful pleasures and tragedies of daily life.

Elia Suleiman’s ‘The Time that Remains’ (2009).

What worlds have changed over the past one hundred years? The same breadth of perception, which often feels too seismic to tackle in traditional narrative cinema, was also explored in The Time that Remains. In a retelling of his family’s history, Palestinian filmmaker Elia Suleiman also tells Israel’s story. It is a film of wry comparisons and Keatonesque comic patterns. As borders change and time passes, few things fundamentally change, except on a spiritual plane. What happens to people without an identity or a country? What damage does it do to their souls?

The question of time looms heavily in both Oliveira’s and Suleiman’s films. They are movies that contemplate centuries of experiences and explore how those stories are guarded, twisted and erased by the powerful.

Alanis Obomsawin’s ‘Incident at Restigouche’ (1984).

The echoes of history and attempts to break with old patterns often emerge in other anti-colonial and anti-imperialist films. They can be seen in Alanis Obomsawin’s vital and angry Incident at Restigouche, about an explosive, centuries-in-the-making 1981 conflict between Quebec provincial police and the First Nations people of the Restigouche reserve; In Lagaan: Once Upon a Time in India, villagers must win a cricket match to free themselves from involuntary servitude; and in Daughters of the Dust, the languid pace of the Gullah culture is challenged by the promise and violence of the American mainland.

Time, more than just a tool for chronology, becomes in itself a tool for oppression. Those who control time maintain power. If we are to break with dominant histories, the rhythms of oppression must be broken and challenged.

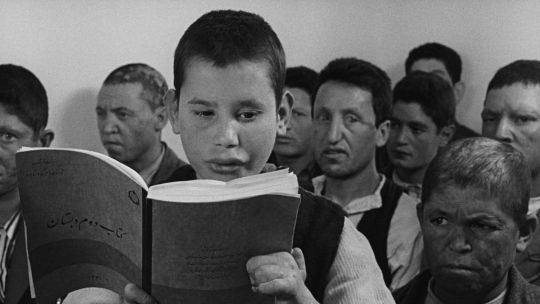

Forugh Farrokhzad’s ‘The House is Black’ (1963).

“The universe is pregnant with inertia and has given birth to time.” —Forugh Farrokhzad, The House is Black

Persian filmmaker and poet Forugh Farrokhzad made just one film before her untimely death in a car accident when she was 32. The House is Black is a short documentary about a Leper colony, which utilizes essay-esque prose taken from the Quaran, and Farrokhzad’s poetry. It is a film about people who are seen as invisible by society at large, cast away and hidden. The film reflects on beauty, sickness and reconciliation. How does one experience time when you’ve been ostracized and cut off from the larger world?

Barbara Loden’s landmark independent film Wanda asks a similar question. A solo mother who cycles from one abusive situation to the next exists outside of time and space. She is invisible. If we look at most American cinema, it might as well be propelled by people who take control over their destiny, but what of the people who are (un)willingly passive to the whims of society and other human beings? In her powerlessness, Wanda stands in for the invisible labor and sacrifices of so many other women. The ordinariness of Wanda’s life, the dusty and dirty environments she inhabits, rebound with significance. It is, however, not a victorious film. Instead, it is a profound portrait of loss and beauty. It’s the only film Barbara Loden ever made.

"If you don't want anything you won't have anything, and if you don't have anything, you're as good as dead." —Norman Dennis in Wanda

Barbara Loden’s ‘Wanda’ (1970).

In 2020, it seemed all we had was time. What seemed like an opportunity quickly became horrific. Time became a burden. We were reminded of our finite time on this Earth and all the hours spent commuting, working and surviving. The pandemic has had a seismic impact on our perceptions. In processing the ongoing crisis, we’ve transformed our relationship to the passage of time. We’ve altered the state of our reality.

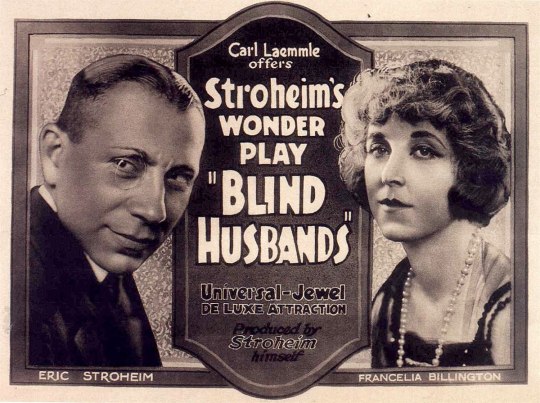

This new pandemic gaze offers us new perspectives on time and history. The oldest film on the list is Erich Von Stroheim’s Blind Husbands, released in 1919 during the grips of the Spanish flu. The film does not reference the event, but its sensuality and class conflicts speak to a world on the brink of seismic change. It is a movie about an Austrian military officer who seduces a surgeon’s wife. The men grapple with jealousy and violence on a literal mountaintop, fighting for survival in an increasingly mechanized society.

Poster for Erich Von Stroheim’s ‘Blind Husbands’ (1919).

To this day, Blind Husbands is shocking. It’s profoundly fetishistic and loaded with heavy sexual imagery. It’s a movie about touch and desire absent of love and affection. It speaks to aspects of current life that feel lost and impenetrable. It speaks to growing and changing social disparities as well. Surviving the modern world is more than just surviving the plague; it has to do with value compromises and shifting power dynamics.

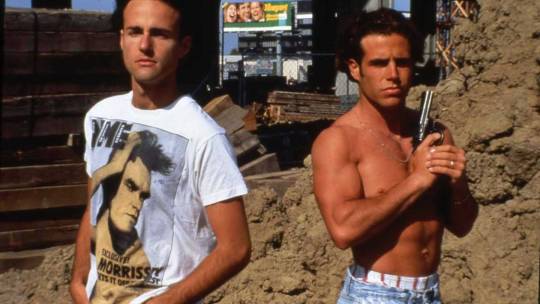

But, a pandemic is also about loss. Gregg Araki’s 1992 film The Living End explores the AIDS crisis from the inside out. Rebellious and angry, the film is about a gay hustler and a movie critic, both of whom have been diagnosed with the HIV virus. With characters who are cast out from society at large, gripped with a deadly and unknown fate, The Living End is apocalyptic—much like other Araki works from the 90s, such as The Doom Generation and Totally Fucked Up. It captures the deep sense of hopelessness of experiencing a pandemic while also belonging to a marginalized group. What is so radical about Araki’s cinema, though, is that it is also fun. It is a film that transcends mourning and becomes a lavish punk celebration. It is a film about survival, out of step with dominant ideology and histories.

Gregg Araki's ‘The Living End’ (1992).

The connections between Blind Husbands and The Living End bridge together to form common passions and changing perceptions. Both films are products of their time, at once part of distant histories but also uncomfortably prescient. More than films about a specific time and place, they are transformed by the time we live in now. To watch and connect with these movies in a pandemic means looking and living beyond the current moment.

While it seems like cinema might be facing an especially precarious future, it feels like the ideal art form to process what is happening right now. Caught in the vicious patterns of our own creation, giving ourselves up to the rhythms of someone else’s will might be a necessary form of healing, as well as an ongoing project in compassion. Time does not have to be a prison; it can be an agent for liberation.

Related content

100 Films to Watch to Expand Your Horizons

The Oxford History of World Cinema

1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die

The Great Unknown: High Rated Movies with Few Views

Follow Justine on Letterboxd

#justine smith#justine peres smith#world cinema#expand your horizons#gregg araki#manoel de oliveira#elia suleiman#julie dash#alanis obomsawin#Forugh Farrokhzad#barbara loden#erich von stroheim#mubi#criterion#criterion collection#letterboxd

15 notes

·

View notes