#...historically documented in our culture. ill also never know if we had gay love stories b4 the spanish bc we were only oral tradition)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

If it's okay for me to add something related because I first saw this on Tumblr: In the mid-2010s, I heard about there being a gay Filipino deity romance (from one culture in the Philippines - there are many different cultures and beliefs) here on Tumblr. It wasn't until years later when researching Philippine deities for fun while trying to broadly connect with my culture that I found a deep dive where someone found that the Bulan and Sidapa love story originated from the same fictional blog source, and had been circulating from new sources and fan art claiming it was historical for years before the author tried to find a non-modern historical source for the rumour, creating a kind of Berenstain/Berenstein effect on the people he asked, claiming they'd heard about the love story from a forgotten source much earlier than the 2010s, but unable to give a specific name, or the source cited claimed they didn't actually know about the romance.

While I think in this instance, a shift in narrative is obviously okay when you consider it is still a living Filipino culture, and people from that clearly find identity with this modern take (which should be asked of people from the cultures directly affected by misinfo), it should also be important not to rewrite it as 'historical fact' particularly when it has a fictional modern source that someone can directly point to as the origin when they question and search down the telephone line (like the game).

(I use the word 'fictional' only in reference to the originating blog, because the blog was unable or unwilling to provide any sources that mentioned that relationship to the deep dive author. I'm not implying said gods can't be/aren't gay. I'm not from that specific Philippine culture, and I don't have enough background knowledge to make any claims of my own. There's also no like, singular religious text/'bible' that pre-Hispanic Philippine beliefs followed as a rule/that can be consulted about this - it's not like a translation debate. There's just no textual source pre-dating the blog making the claim of the romance, and historians/oral historians aren't making the claim either.)

I get variations on this comment on my post about history misinformation all the time: "why does it matter?" Why does it matter that people believe falsehoods about history? Why does it matter if people spread history misinformation? Why does it matter if people on tumblr believe that those bronze dodecahedra were used for knitting, or that Persephone had a daughter named Mespyrian? It's not the kind of misinformation that actually hurts people, like anti-vaxx propaganda or climate change denial. It doesn't hurt anyone to believe something false about the past.

Which, one, thanks for letting me know on my post that you think my job doesn't matter and what I do is pointless, if it doesn't really matter if we know the truth or make up lies about history because lies don't hurt anyone. But two, there are lots of reasons that it matters.

It encourages us to distrust historians when they talk about other aspects of history. You might think it's harmless to believe that Pharaoh Hatshepsut was trans. It's less harmless when you're espousing that the Holocaust wasn't really about Jews because the Nazis "came for trans people first." You might think it's harmless to believe that the French royalty of Versailles pooped and urinated on the floor of the palace all the time, because they were asshole rich people anyway, who cares, we hate the rich here; it's rather less harmless when you decide that the USSR was the communist ideal and Good, Actually, and that reports of its genocidal oppression are actually lies.

It encourages anti-intellectualism in other areas of scholarship. Deciding based on your own gut that the experts don't know what they're talking about and are either too stupid to realize the truth, or maliciously hiding the truth, is how you get to anti-vaxxers and climate change denial. It is also how you come to discount housing-first solutions for homelessness or the idea that long-term sustained weight loss is both biologically unlikely and health-wise unnecessary for the majority of fat people - because they conflict with what you feel should be true. Believing what you want to be true about history, because you want to believe it, and discounting fact-based corrections because you don't want them to be true, can then bleed over into how you approach other sociological and scientific topics.

How we think about history informs how we think about the present. A lot of people want certain things to be true - this famous person from history was gay or trans, this sexist story was actually feminist in its origin - because we want proof that gay people, trans people, and women deserve to be respected, and this gives evidence to prove we once were and deserve to be. But let me tell you a different story: on Thanksgiving of 2016, I was at a family friend's house and listening to their drunk conservative relative rant, and he told me, confidently, that the Roman Empire fell because they instituted universal healthcare, which was proof that Obama was destroying America. Of course that's nonsense. But projecting what we think is true about the world back onto history, and then using that as recursive proof that that is how the world is... is shoddy scholarship, and gets used for topics you don't agree with just as much as the ones you do. We should not be encouraging this, because our politics should be informed by the truth and material reality, not how we wish the past proved us right.

It frequently reinforces "Good vs. Bad" dichotomies that are at best unhelpful and at worst victim-blaming. A very common thread of historical misinformation on tumblr is about the innocence or benevolence of oppressed groups, slandered by oppressors who were far worse. This very frequently has truth to it - but makes the lies hard to separate out. It often simplifies the narrative, and implies that the reason that colonialism and oppression were bad was because the victims were Good and didn't deserve it... not because colonialism and oppression are bad. You see this sometimes with radical feminist mother goddess Neolithic feminist utopia stuff, but you also see it a lot regarding Native American and African history. I have seen people earnestly argue that Aztecs did not practice human sacrifice, that that was a lie made up by the Spanish to slander them. That is not true. Human sacrifice was part of Aztec, Maya, and many Central American war/religious practices. They are significantly more complex than often presented, and came from a captive-based system of warfare that significantly reduced the number of people who got killed in war compared to European styles of war that primarily killed people on the battlefield rather than taking them captive for sacrifice... but the human sacrifice was real and did happen. This can often come off with the implications of a 'noble savage' or an 'innocent victim' that implies that the bad things the Spanish conquistadors did were bad because the victims were innocent or good. This is a very easy trap to fall into; if the victims were good, they didn't deserve it. Right? This logic is dangerous when you are presented with a person or group who did something bad... you're caught in a bind. Did they deserve their injustice or oppression because they did something bad? This kind of logic drives a lot of transphobia, homophobia, racism, and defenses of Kyle Rittenhouse today. The answer to a colonialist logic of "The Aztecs deserved to be conquered because they did human sacrifice and that's bad" is not "The Aztecs didn't do human sacrifice actually, that's just Spanish propaganda" (which is a lie) it should be "We Americans do human sacrifice all the god damn time with our forever wars in the Middle East, we just don't call it that. We use bullets and bombs rather than obsidian knives but we kill way, way more people in the name of our country. What does that make us? Maybe genocide is not okay regardless of if you think the people are weird and scary." It becomes hard to square your ethics of the Innocent Victim and Lying Perpetrator when you see real, complicated, individual-level and group-level interactions, where no group is made up of members who are all completely pure and good, and they don't deserve to be oppressed anyway.

It makes you an unwitting tool of the oppressor. The favorite, favorite allegation transphobes level at trans people, and conservatives at queer people, is that we're lying to push the Gay Agenda. We're liars or deluded fools. If you say something about queer or trans history that's easy to debunk as false, you have permanently hurt your credibility - and the cause of queer history. It makes you easy to write off as a liar or a deluded fool who needs misinformation to make your case. If you say Louisa May Alcott was trans, that's easy to counter with "there is literally no evidence of that, and lots of evidence that she was fine being a woman," and instantly tanks your credibility going forward, so when you then say James Barry was trans and push back against a novel or biopic that treats James Barry as a woman, you get "you don't know what you're talking about, didn't you say Louisa May Alcott was trans too?" TERFs love to call trans people liars - do not hand them ammunition, not even a single bullet. Make sure you can back up what you say with facts and evidence. This is true of homophobes, of racists, of sexists. Be confident of your facts, and have facts to give to the hopeful and questioning learners who you are relating this story to, or the bigots who you are telling off, because misinformation can only hurt you and your cause.

It makes the queer, female, POC, or other marginalized listeners hurt, sad, and betrayed when something they thought was a reflection of their own experiences turns out not to be real. This is a good response to a performance art piece purporting to tell a real story of gay WWI soldiers, until the author revealed it as fiction. Why would you want to set yourself up for disappointment like that? Why would you want to risk inflicting that disappointment and betrayal on anyone else?

It makes it harder to learn the actual truth.

Historical misinformation has consequences, and those consequences are best avoided - by checking your facts, citing your sources, and taking the time and effort to make sure you are actually telling the truth.

#sorry if i get something wrong im trying to refresh my memory as i write this#also just a cool fun fact theres a nonbinary tagalog deity that IS documented in historical texts#which was cool to find out back when i was looking all this up the first time and again just now#i promise im not biased for being tagalog it was just literally recommended reading on the same article#should also state that im also american in america and dont subscribe to belief in philippine deities (as a disclaimer)#but its still super cool to find out how socially accepting the philippines can be about lgbt issues compared with other asian countries#(even if they still face discrimination! obviously should go without saying but someones gonna twist my words i just know it)#(im reminded of the other spanish-us colony... the us. where i live as a native american also. whos tribe Chumash also had/has Two Spirit..#...historically documented in our culture. ill also never know if we had gay love stories b4 the spanish bc we were only oral tradition)#anyway thats a tangent on a tangent on a disclaimer on a tag on an anxiety filled addition to a post#anxiety bc im probably getting something wrong somewhere just know that i am always pro-gay everything all the time forever#i just wanted to add how this disappointed me when i found out the gay was not historical like i originally was made 2 believe#im in full support of modern gay#how mnay times am i gonna say that lmao (how many tags do i have left to be anxious in)#listen one time i got put on a blocklist next to actual transphobes whod hate me and im still anxious every time i post anything online now#(it was over something i said when i was first discovering my gender abt how sex and gender 'are' different and it wasnt worded the best)#and because i was pro-asexual inclusion in lgbt then exclus went and dug up that very obviously old post from my blog to have 'dirt' on me#i fucking hate ace exclusionists lmao dni with me about that topic its been like 8 years stale by now#anyway...#misinformation#disinformation#history#long post#i know theres some drama idk about the article author but i dont want to bring that into this so i didnt name the article#...but its on the aswang project if youre gonna look it up#i want to get books on philippine legends but i dont have the money and theyre not in my library so .. eventually ill read the more...#...scholarly sources on the subject but for now i only have whats online and that site has been a good jumping point imo#ok ive had this reblog open for hours now lemme just post and if someone who knows more can correct me go ahead just pls b nice i rly tried#im tired and i want to get back to my drawing i didnt wanna spend hours beng anxious abt this bc i randomly saw it while break scrolling

15K notes

·

View notes

Note

i read the first tales of the city last week after picking it up at an out of the closet (usamerican gay thrift shop chain) (i refrained from picking up any pulp sff bc i know i usually don’t get around to reading it, and any books with hairy shirtless men on the cover bc i was embarrassed, but like. the gay cashier isn’t going to judge me so if there’s anything left next time i go in... anyway) do you think i should read more of the series before gawking at the show

Great question ^_^

There's a couple of different answers to this:

1) In terms of continuity/canon, the Netflix TV series is set in the present day as a sequel to the book series. But it's a free adaptation, and diverges from the canon whenever it feels best to them.

It doesn't matter that much if you haven't read the series; the concept is, as in the books, ensemble cast of intertwined tales of queer chosen family in San Francisco - and that's the sort of thing you can pick up at any stage. And I'm not convinced that the new series meaningfully constitutes "spoilers" either, because it's so clearly a parallel canon rather than a replacement or continuation.

THAT SAID. A bit like Picard, it leans heavily on sentimental nostalgia; I'm not sure why you would care enough about the indulgent, semi-deification of the characters if you weren't already invested in them.

2) There's also an older TOTC adaptation, with the same cast, which I haven't seen - but would still like to.

3) In terms of pleasure: I just counted on my shelf, and I own all nine TOTC books plus one of his others. I think the book series is fantastic. In contrast, I watched three episodes of the show and haven't bothered to finish it.

The books are a series where you'll either read one of them, or all nine. The first book is an essential part of our literary history and culture; but if you buy what he's selling, it's pretty irresistable.

TOTC books are an interesting historical document - especially the first few which have a slice-of-life wit and a parodic eye. "The City" is Maupin's great love affair, so it's a document of that moment and that place - as well as notable for its groundbreaking representations of LGBT characters.

Beyond that, it's a string of sausages story and you stick with it because you love the characters. Maupin isn't immune to a very silly plot twist, but his observational character writing is always excellent; he seems to struggle with finding the narrative on which to hang his character work. Expect a soap opera twist at the point 75% through the novel when he thinks just having characters talk to one another isn't enough and something ought to Happen. But you know what? It is enough. I wish he had had the courage in his observational work to let it stand on its own.

I also think he has one of the most interesting treatments of AIDS in literature. His books are semi-autobiographical, written contemperaneously, and it's telling to me the way he chooses to almost step around it - for example, killing main characters in the time between books, so as not to tell the story of their illness on the page. In both TOTC and the Night Listener, he explores HIV through the experiences of straight characters. You get a real sense of him needing to approach this topic from the side, rather than head on. That's important to me, in and of itself, as a document of that part of our history.

4) I think the best run is books 5-7: Significant Others/Sure of You/Michael Tolliver Lives, with the last of those being the one I've read to death.

I didn't get on with book 8 (Mary Ann in Autumn), but it has a nice subplot about young gay trans man Jake connecting with this Mormon youth pastor missionary who may-or-may-not-be-gay. Book 9 (the Days of Anna Madrigal) was a travesty, absolutely terrible. The more you learn about Maupin's life, the more you realise the books are literally just things that happened to him - including having disappointing sex with a closeted film star. The reality of Book 9 is that Maupin is an married man living a quiet life, and not much is happening any more.

So if you're reading, you can stop after book 7.

5) One of the most important things about the series is how connected Maupin is to the world he's writing about. Filled with knowing references that his gay readers of 1974 would have understood, to people and places and bars and events and things you see on the street there.

The Netflix has attempted to replicate this by updating it for modern queer culture and modern SF. I don't think the writers are part of that world, it doesn't read as "real" to me.

For one thing, adjusting Jake from a young gay trans man who hooks up with the poly, married, older cis male protagonist - courageously, but with confidence - to one of the "young people" characters, having relationships with other young people newly created for the series. There's a subtle othering going on here, suggesting Jake's life is a "young person's thing". But in one stroke, they've erased the age gap, the open marriage, the long history of gay trans San Franciscans as an equal part of a historic community...trans lives are not validated by cis people's acceptance or by sex, but when you're adapting the longest-running openly gay character in literature, the character who comes to embody the life of a gay man over the course of 3 decades of books, and you choose to write the trans characters out of his bedroom, and into this nebulously modern queer space instead, you are Making A Choice.

I had horrible experiences in queer spaces, so the rosy-tint everything has doesn't read as real to me; and where are all those trans young artists living in San Francisco anyway? Yeah, Anna and Edgar are running an Instagram account, but the tale of the city is not the tech revolution, but the people crushed underneath it.

You know, what happens in the book series at the moment we move into the present day is that Mrs Madrigal has to sell her house - that iconic house, the house on which everything centers - because she's an older woman in a rapidly gentrifying city that's shifting underneath them, and she needs the money.

But in the show, there she is, at Barbary Lane, luminous and surrounded by loved ones; it's giving us what we "want", part of the Maupin brand. But Barbary Lane is not the house, but the way the people within it create home for one another there. I think what it misses is that these are tales of the city, and like any lover, you adore it even when your heart is breaking - you have to be honest about that which you love, in all its imperfections; Michael Tolliver Lives explores that a little in 2016, what it means for the city to be gentrifying, but a series made in 2019 shies away from it?

To me, this sort of exemplifies the queerwash cowardice of the series. It's something hollow draped in a rainbow flag. Maupin was never cruel to his characters - but he never lied about them either. The series is safe, unwilling to criticise, unwilling to take risks, unwilling to look at the modern city or modern queer life with a clear and honest eye, it's like eating a wad of colourful cardboard.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

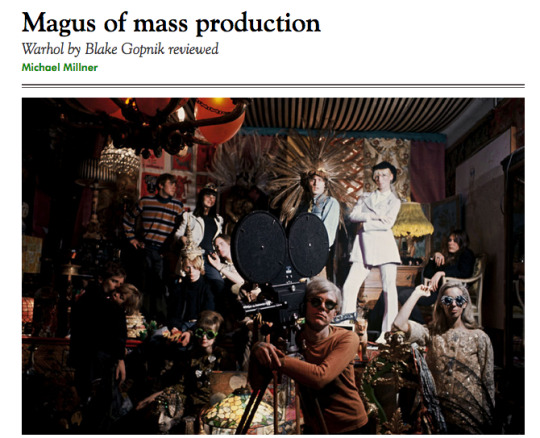

Lovely review of my Warhol bio by Michael Millner in the US edition of The Spectator:

“An extraordinary and revealing biography — surely the definitive life of a definitive artist….There is something interesting, revealing or humorous on just about every page. Gopnik deftly excavates his data mine. His prose is precise and pointed, and his year-by-year narrative clips along. He is also a master of pithy and informative character and historical sketches.”

Magus of mass production

Warhol by Blake Gopnik

Ecco, pp.976, $45.00

reviewed by Michael Millner

This article is in The Spectator’s April 9, 2020 US edition.

‘If you want to know all about Andy Warhol,’ the artist said in the East Village Other in 1966, ‘just look at the surface: of my paintings and films and me, and there I am. There’s nothing behind it.’ This quotation re-appeared in 2002 on the US Post Office’s commemorative Warhol stamp. It’s fabulously fitting for a stamp that reproduced a self-portrait, but when scholars recently compared the audiotapes of the interview with the printed version, the passage wasn’t on the tapes. Warhol sometimes invented interviews from whole cloth. He answered questions with a gnomic ‘yes’ or ‘no’ or, refusing to speak at all, allowed proxies like his ‘superstar’ Edie Sedgwick to answer for him. After all, he was just surface — leather jacket, shades, wig. The magus of mass production was there and everywhere forever, but nowhere in particular. This negation of personality seems a publicity ploy, or the evasiveness of a shy man, or possibly the self-protection of a gay man in pre-Stonewall America. It was all of this, but also much more. The self-as-surface routine was perfect for a new kind of celebrity, one founded less on accomplishment and talent and more on presenting a surface for the projected desires of a mass audience. Authenticity and the sense of a deep self were obstacles to the creation of this new celebrity persona. Warhol made millions by autographing screen prints that were mass-produced by anonymous assistants. Warhol somehow understood how this all worked. Born in 1928 in Pittsburgh to working-class Catholics from eastern Europe who barely spoke English, he realized the power and danger of being known to the world. The flipside of ‘15 minutes of fame’, Warhol suggests again and again, is death. The paintings of Marilyn Monroe memorialized her suicide; those of Jackie Kennedy, her suffering following her husband’s assassination. After Warhol survived his own assassination attempt in 1968, he allowed Richard Avedon to photograph the surgeon’s scars that crisscrossed the surface of his torso. There is no narrative development or personal bildungsroman in Warhol’s art, and his affectless manner resists psychologizing, the biographer’s stock-in-trade. His images are impressions, flashes whose immediacy, flatness and repetition carry little sense of progression. The Brillo box contains no story, and the subject of a film like Empire, with its eight hours of static footage of the Empire State Building, remains inanimate. Despite Warhol’s resistance, Blake Gopnik has written an extraordinary and revealing biography — surely the definitive life of a definitive artist. He accomplishes this through broad and deep, even obsessive, research into what he calls Warhol’s ‘social network’. Gopnik reports that he consulted 100,000 period documents and interviewed 260 of Warhol’s lovers, friends, colleagues and acquaintances. Warhol kept everything — he was a hoarder, collector and archivist all his life — and Gopnik has left no archival folder unopened or box unperused. Across 976 pages and more than 7,000 footnotes on a separate website, he recreates the swirl of ideas, culture and especially people that orbited Warhol. Warhol famously thought of his studio as a factory, producing work after work off an assembly line. The catalogue raisonné of his paintings, drawings, films, prints, published texts and conceptual works would, if it were ever completed, rival that of the other master of 20th-century self-replication, Picasso. Gopnik has surveyed it all.

There is something interesting, revealing or humorous on just about every page. Gopnik deftly excavates his data mine. His prose is precise and pointed, and his year-by-year narrative clips along. He is also a master of pithy and informative character and historical sketches: ‘Warhol’s Pop wasn’t about borrowing a detail or two from commercial work, as many of his closest colleagues [like Robert Rauschenberg] did; it was about pulling all its most dubious qualities into the realm of fine art and reveling in the confusion they caused there. ‘He wants to make something that we could take from the Guggenheim Museum and put it in the window of the A&P over here and have an advertisement instead of a painting,’ complained one early critic of Warhol’s, getting it right, but backward: Pop pictures started in the windows and then migrated to the museums.’ Warhol is about the Age of Warhol as much as Warhol himself. We learn about the new possibilities of gay life in 1950s New York, the city’s underground film scene, the history of silk-screening (so important to Warhol’s art), the fluctuations of the art market, the history of department-store window design. We learn about fascinating things we may not even want to learn about, such as the size and color of Warhol’s penis. (Large and gray, like the Empire State Building.) Warhol arrived in New York City in 1949 and quickly made a name for himself as a commercial illustrator, especially of women’s shoes. He lived for two decades with his mother, Julia, one of his most influential muses, and sought out an emerging coterie of gay artists including Truman Capote, with whom he had a stalkerish infatuation. The great Pop paintings of the early 1960s transformed American art. No less important was Warhol’s mid-Sixties salon and studio, the Silver Factory (silver because wallpapered in aluminum foil). This perverse and fecund anti-commune of ‘superstars’ and hangers-on spawned Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground, as well as Warhol’s wannabe assassin, Valerie Solanas. On June 3, 1968, Solanas shot Warhol in the name of feminist revolution. His heart ceased beating on the emergency room table before a determined surgeon saved him. In the 1970s, he turned to what he called ‘business art’, mainly portraits of other famous people. He died in 1987, aged 58, after gallbladder surgery. Gopnik unpicks many of the conventions of Warhol’s non-biography. Warhol wasn’t an aesthetic rube when he arrived in New York. He had received an extraordinary avant- garde education from four years at the Carnegie Tech art school and at the Outlines gallery, which had brought Jackson Pollock, Alexander Calder, Joseph Cornell, Francis Bacon, Merce Cunningham and many other transformative artists to Pittsburgh in the 1940s. Warhol did not suddenly reinvent himself as a Pop artist in the early 1960s. As he built a successful career illustrating advertisements in the Fifties, he regularly tried to cross the line between commercial and fine art — a crossover he finally achieved in late 1961 with ‘Campbell’s Soup Cans’. Warhol was baptized ‘Drella’ by acquaintances — part bloodsucking Dracula and part innocent yet social-climbing Cinderella. But Gopnik also argues that one of Andy’s greatest desires was for compassionate companionship. This was never achieved. The ‘routine’ gallbladder surgery which led to his death was anything but routine. He had been very ill for weeks but avoided treatment out of a lifelong fear of surgery and a misplaced faith in the healing powers of crystals. Emphasizing Warhol’s radical ambiguity in art and life, Gopnik makes it impossible to say anything easy about him. His Warhol is a complex artist practicing what Gopnik, in a marvelous turn of phrase, calls ‘superficial superficiality’. The Warhol brand, the images of branded goods, famous faces and dollar bills, celebrates consumerism but also leaves us a little nauseated from our commodity fetishism. Warhol’s endless ‘boring’ films are hard to ignore because they give us so much space and time to think. They are studies in modern emptiness, and thus deep meditation. Warhol the critic of modern celebrity was also one of its greatest adulators. This double image of Warhol seems just right. ‘His true art form,’ Gopnik writes, ‘first perfected in the first days of Pop, was the state of uncertainty he imposed on both his art and his life: you could never say what was true or false, serious or mocking, critique or celebration... Examining Warhol’s life leaves you in precisely the same state of indecision as his Campbell’s Soup paintings do.’ Gopnik’s analysis of Warhol’s ambivalence evokes another great observer of midcentury American culture. Lionel Trilling, the gray-suited lion of Columbia’s literary studies, would have hated Warhol, had he deemed the Silver Factory worthy of a visit. Still, Trilling’s America is Warhol’s: ‘A culture is not a flow, nor even a confluence; the form of its existence is struggle, or at least debate — it is nothing if not a dialectic. And in any culture there are likely to be certain artists who contain a large part of the dialectic within themselves, their meaning and power lying in their contradictions.’ To Trilling, the great American authors contained ‘both the yes and the no of their culture, and by that token they were prophetic of the future’. Warhol absorbed and reflected the affirmations and negations of his America — but was he prophetic of ours? Yes and no. For a long time now we have lived in the Age of Warhol. If he were alive today, he would film us staring blankly at the social networks on our smartphones, hour after hour, while nothing and everything go on and on. By retaining ambivalence, Warhol allowed us to recognize and experience the deepest ethical dilemmas of American life — and he paid a price for being our screen and mirror.

0 notes