#(which I guess is understandable how central the themes of not just secret identities but the many masks people wear to hide are to comics)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

“Shame,” Moon Knight: Fist of Khonshu, (Vol. 2/2024), #6.

Writer: Jed MacKay; Penciler and Inker: Domenico Carbone; Colorist: Rachelle Rosenberg; Letterer: Cory Petit

#Marvel#Marvel comics#Marvel 616#Moon Knight: Fist of Khonshu#Moon Knight: Fist of Khonshu vol. 2#Moon Knight: Fist of Khonshu 2024#Moon Knight comics#latest release#Moon Knight#Marc Spector#Tigra#Greer Grant#8-Ball#Jeff Hagees#Soldier#Reese Williams#Hunter’s Moon#Yehya Badr#alrightalrightalright here’s hoping we’re on an upswing and will be back shortly to putting adversaries out of commission#and you know what it’s pretty crazy after all these years of frustratedly blazing through comics I’m seeing something I always wanted:#characters not only directly communicating but apologizing even as opposed to floundering through half-truths and unspoken feelings#I particularly found Greer’s «why won’t/when will you trust me» comment distantly amusing because of how common it is to comics#(which I guess is understandable how central the themes of not just secret identities but the many masks people wear to hide are to comics)#but it’s rare such a comment is accompanied by an apology and efforts to improve#and tying it all together here with Marc’s propensity for self-sacrifice is a nice touch#idk I’m sure some fans out there aren’t a fan of all the «therapy talk» (comic fans are never happy hahaha) but I don’t know#I feel like this might be a bit of a trade-off for character development#with characters learning to communicate/improve interpersonal relationships or be plagued by the stale#lack of development that can sometimes stick uniquely to comic characters#but that’s just something I’ve been chewing on so it’s kind of half-baked hahaha

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Assorted Jupiter’s Legacy thoughts

Spoilers galore. Spoiling everything.

In retrospect, I should have called that Walter was secretly evil because I kept thinking to myself how in the present story line Walter was the only person who had his life together and could communicate and all that. And when everyone else is kind of a walking disaster that’s a sure sign of trouble right there.

Very disappointed that he killed Raikou though. Maybe we’ll get some flashbacks of her in season 2.

Overall like the show and the way it explores its central theme a lot but I’m not sure where they’re coming from with the whole “the world didn’t used to be like this” refrain. Like guys. You lived through two world wars, the Great Depression, the Cold War where all anyone did was threaten to nuke each other.... what about people’s capacity for evil is surprising to you? Even more so for Fitz who had to live through Jim Crow era.

I feel bad for Chloe... but also I kind of hate Chloe. Which I think is what they’re going for so good for them I guess.

Did George name his son Hutch Hutchence or does he just go by Hutch as an abbreviation of Hutchence and have a different first name that he doesn’t use? because I assumed the latter but google searches seemed to indicate the former and if that’s the case what the heck George? Do better.

But WHY does Skyfox have the helmet when no one else does anything like that?

Also pretty sad that Ghostbeam died.

I feel like we really have to break down Sheldon not knowing the younger heroes real names more. That’s very troubling to me. Also troubling to me: Sheldon’s personal style choices in the modern timeline.

I get that the Union members (or at least the original six) live a lot longer because of their powers and are thus able to have children a lot later in life and so some of them wouldn’t have kids until later... but because of that how did they ALL end up having kids in the same ten year window? They could have had kids at any point during like a seventy year period and they ALL happened to have kids at the same time? What’s up with that?

I really want to believe that Hutch is right-- that George didn’t actually betray the union and that it was actually something that Walter orchestrated to turn the others against him. Maybe that’s why no one’s been able to find him for so long-- because Walter has him trapped somewhere.

I’m not sure if I missed some explanation of how a bunch of people not related to the union got powers too or if that is just something that has not yet been explained.

I want to meet Raikou, Hutch, and Petra’s mothers. Also, are they dead? If so being with a Union member has a high mortality rate (if you are not a Union member yourself).

Grace being able to tell when people are lying was strikingly irrelevant all season.

Brandon looks kinda like Matt Lanter/George. If there’s a plot twist coming where Grace cheated on Sheldon with George and Brandon is actually George’s son, then bravo on the casting. I don’t actually think that’s the case, I’m just saying.

I like Petra and I think she and Brandon should get together.

Despite my mixed feelings about Chloe I do kinda like her and Hutch together, and if she pulls herself together a little bit I think I could like them as a couple too.

Actually that reminds me, what was up with the stuff she snorted? What was that? Is Hutch using her because of that? If so I take back what I said before about them being together.

Is Grace’s actress wearing a wig in both the flashbacks and the present? because she looks like it and I understand the need for one but both seems odd. There are so many things from the past timeline that I still want answers on, like when they abandoned secret identities.

And where is Richard? Fitz said that no one died when he was in the union so in theory Richard must be somewhere. Unless he did die just not as a superhero. Or maybe he retired, in which case good for him. He didn’t sign up for this.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

This isn’t related to anything, but frozen 2 was actually...pretty good of a movie, and you can literally see the disney profit model holding it back. firstly, the music was really good -- i was really impressed with the writing team and with the vocal performances, especially by idina menzel. the songs that didn’t make it in because the plot was rearranged were also excellent. wrt to the visuals, i’m not the biggest fan of this specific animation style, but it’s clear it’s very well done -- i’ve no choice but to be impressed. the plot was whatever (also they fully put a couple of trolls in charge of the kindom for a bit -- is there no fucking line of succession in this goddamn kingdom?? maybe the plot of the movie should have been establishing a functional bureaucracy) and they really yada-yada-ed the magic system, which was basically of the central conceit of the movie so...why did they not put more effort into it? the explanation, such as it was, of the magic system was both confusing and ultimately pretty meaningless -- it added next to nothing of value to the lore or theme or worldbuilding. the themes were clearly meant for a more mature audience (which is i guess what you get for waiting 7 years to make a sequel [which btw just wrenched out a memory out of me that frozen 1 came up literally constantly in my 7th grade latin class -- i cannot emphasize enough how bizarre of an experience learning a dead language throughout the entirety of your teenage years along with 400 more of your cohort is]) -- but anyway, they establish all these themes and then don’t commit to them. Like, the central plot conflict of the movie is literally colonialism lmao. it’s such a strange place to discuss it. My suspicion is that they decided right away to go with a “connecting with mother” storyline, since the “women in the same family connecting with each other” bit worked so well in the first movie; then they were like “is this too basic?” and decided that they should wrap that into a “reckoning with ancestry” thread to cash into that “young leftist with white guilt” market. Then they had somebody on the writing staff who was like “what if we made this about colonialism?” So re: those elements, first of all the mother plotline is boring as shit. Like it doesn’t ring true even to losing a loved one early, but it especially rings soooo hollow wrt the actual relationship that is portrayed in the first movie between elsa and her parents. like we see the parents be so misguided it borders on abusive. and that’s a really interesting dynamic, story-wise, bc the parents are dead and can’t redeem themselves but the baggage they left behind is still there, so the burden of processing that falls exclusively on the daughters. i dare say this is something probably relatable to many of us, bc it’s my sense that most people grow up with pretty misguided parents! (lowkey i feel like the best parenting i’ve seen in my circle are parents who basically went off of vibes rather than idk a philosophy or whatever) i actually would have loved to see a children’s movie address dealing with parents in a nuanced way that isn’t just “one of us is right and the other is wrong” but rather addresses what responsibilities parents and children have to each other, how to navigate intent versus effect, what the value (or lack thereof) of forgiveness is, how to uncover your identity when your entire life was shaped by societal and parental expectations, etc. And the Frozen premise is ideally suited for this! Moreover, a lot of these beats actually DO happen in the movie! Into the unknown is basically elsa trying and failing to convince herself that she wants the life she has and any thoughts to the contrary should be dismissed (and it’s gay as hell, but we’ll get to that later). The climax of show yourself literally says that it was the truth about herself rather than her mother that will bring her peace. But all of these beats are facilitated supernaturally rather than by the very fitting preexisting character background, which makes it lack the satisfaction you’d expect in such a resolution. it never features any reckoning with what made her feel the way she did in the first place -- a projection of the mother’s face singing the climactic realization literally undercuts the entire plotline. like here you can see how basically being propaganda for the american lifestyle (in this case the nuclear family e.g.) undercuts their message. this predictably only gets more egregious when they attempt to tackle colonialism. so quick summary of this plotline: anna and elsa’s grandfather basically genocided an indigenous people -- the northuldra -- after tricking them into building a dam that stifles the power of the forest or something. also their mother was actually northuldra. also magic comes from the northuldra forest? it would probably be pretty problematic re: the magical native stereotype if it was clearer what was going on lmao. at the end, anna breaks the dam even though it’ll flood Arendelle; however, elsa (who was literally frozen because of the sins of the past) swoops in at the last moment and freezes the wave so it causes no damage. However, in an earlier version of the story, the wave actually DOES destroy Arendelle and then they rebuild it with a mix of Arendellian and Northuldran architectural styles. this version actually proposed a genuine vision for how to deal with the impacts of colonialism instead of the final movie where sisterly love absolves everyone of consequences.

ok, so about the gay: i know people read a coming out into let it go, and maybe this is just cause i watched frozen 1 when i was still straight, but i didn’t really see it. but the lyrics in frozen 2 elsa’s songs match up so well with the coming out experience, i have difficulty imagining the song-writers weren’t aware of it, especially since people were already calling for elsa to be gay. Like let’s take a look at these songs -- into the unknown first. She sings

“Everyone I've ever loved is here within these walls I'm sorry, secret siren, but I'm blocking out your calls I've had my adventure, I don't need something new I'm afraid of what I'm risking if I follow you”

This idea of having being afraid of ruining relationships even (and especially) with the people you love most by coming out is something that a lot of queer people can relate to. Then she sings:

“Are you here to distract me so I make a big mistake? Or are you someone out there who's a little bit like me? Who knows deep down I'm not where I'm meant to be? Every day's a little harder as I feel your power grow Don't you know there's part of me that longs to go”

How much do i need to explain this? (like all my 7 followers are some form of queer anyway lol) But again this battle of trying to hide but knowing deep down that you can’t, longing for “someone a little bit like me” -- it’s classic queer. Then she sings a bridge-type thing:

“Are you out there? Do you know me? Can you feel me? Can you show me?”

I mean, again, what is this but longing for community. Then in the climactic song “show yourself”, she sings this:

“Something is familiar Like a dream, I can reach but not quite hold I can sense you there Like a friend I've always known”

this is literally just about reading stone butch blues.

The climactic lyric is “You are the one you've been waiting for all your life” (sung to her rather than by her) and i mean again, this is about finally giving yourself permission to live as your true self. And not gonna lie, i dug that shit. it felt quite authentic. obviously they didn’t actually make her gay, bc of course, but she is gay in my heart!

Ok, so what would have made the movie live up to its full potential?

1) fixing that stuff i already said about the parents; it felt like such bs that anna and elsa were dealing with ancestral sins but also their parents were saints whose love fixed everything? how much more interesting would it have been if reckoning with their parents’ impacts on them led them to reckoning with the impacts of their entire ancestry and in turn their society? if reckoning with their personal responsibilities to each other led them to consider their society’s responsibility to fix the past wrongs that allowed it to flourish? this wouldn’t even be counter to disney’s individualism, but it allows for a slight reconceptualization of it that i think would feel fresh.

2) having actual consequences for the colonialism and genocide

3) either cutting all the new magic system stuff or developing it in a way that in turn helps develop the themes. frankly, the “sometimes people are born with magic” that was implied in movie one was enough.

4) making elsa gay, and i say this not just because i want gay characters but because that genuinely makes sense within the story

5) basically, the central theme should have been “i have all this baggage and i can’t resolve it by looking for answers only within my society; in order to be fully at peace with myself, i must work to right the wrongs of my society that obscured the different ways of knowledge that could help people like me; sometimes you must go into the unknown in order to understand the known” which is a message i think very well suited for the united states!

#In general Disney has created this really cowardly mold for children’s media#where the messages rarely go beyond the individual and are universally basic as shit#and that comes from a fundamental lack of respect for the audience#people keep telling me that pixar has deep multidimensional messages#and i’m sorry to say that your standards are just low#like people keep citing inside out to me and the message of that was literally “it’s okay to be sad sometimes”#cheburashka had a more complex message than that.#i know nobody asked for this long-ass analysis#and i myself watched frozen 2 in like may so idek why i started thinking about it again now#but it's just such a weird yet revealing movie#frozen 2 should have been abolishing prisons#but like seriously idk where they pulled colonialism from#but if they wanted to address a serious issue#prisons would have been perfect#because elsa basically spent half her life in a form of incarceration for being a perceived societal menace#i guess that's more difficult to weave into a story arc#oh holy fuck this reminds me that when i was 16 i was paid (very little might i say but nevertheless)#to 'ghostwrite' a witch cozy#whatever the fuck that is#but literally 'witch cozy' was the entirety of the prompt#no plot or characters or anything#there were 3 novellas#in the first one they made me changed the gay love story to a het one lmaoooo#in book 2 she busts a crime ring or sth and then realizes that social determinants made them commit crimes#and then in book 3 she becomes a prison abolitionist lmaooo#she starts running a rehabilitation program in the local prison using theater#this character was so self-insert it was ridiculous#no offense at whoever's writing the flash but 16-yo disaster child me had 15x more social consciousness than yall#sorry to analyze a different piece of media in the tags for another long-ass media analysis#but in s1 of the flash the local prison can't handle the new metahumans

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Untold Tales of Spider-Man 06: The Doctor’s Dilemma – by Danny Fingeroth

An unexpected gem!

Dr. Bromwell grabs Peter by the arm and tells him he must talk to him about "his double life." But Bromwell hasn't stumbled on Pete's secret identity. He's talking about the dangers Pete gets into as a Daily Bugle photographer. He asks Peter, for May's sake, to give up the job. Although Peter has worried about the dangers himself, he stiffs Bromwell, saying "I'd appreciate it if you'd mind your own business, Doctor." Regretting every word, Peter goes into an unfair critique of Bromwell and a defense of his photography work. Taken aback, Bromwell gives Pete a new prescription for May and heads toward the door. Peter calls him back and apologizes. He tells him he has considered the dangers but still thinks the reward is worth the risk. Once Bromwell leaves, Peter changes to Spider-Man, eventually web-swinging to the pharmacy to fill May's prescription.

Back at his office, Bromwell can't stop thinking about Peter. Suddenly, he gets a brainstorm. He wants to give Peter a job in the sciences instead. First he goes to Metro Hospital and talks to Dr. Gordon, who saved May's life after Spider-Man brought in the needed ISO-36 (in Amazing Spider-Man #33, February 1966). Gordon reveals that, shortly after Spidey left, a beaten and bruised Peter appeared. Bromwell doesn't know what kind of deal Peter has with Spider-Man but he suspects the web-slinger is taking advantage of him.

Out web-slinging, Spidey comes upon "an eight-foot tall, four-foot wide gent in the green spandex suit" who is trashing an armored car. He is also "amazingly fast and as strong as the Hulk." When Spidey asks for a name, the giant comes up with "Impact," revealing that he volunteered for an experiment involving radioactive steroids (a combination just asking for trouble) for which he never got paid. Now paying himself in his own way, Impact slams Spidey against a wall and escapes.

The next day, Bromwell makes a house call and finds Peter all battered and bruised. He offers Pete a job in his own office helping with his research and lab work. Peter accepts. Aunt May overhears this conversation and is wracked with guilt for letting Peter risk his life taking pictures simply because they desperately needed the money.

So, Peter goes to work for Bromwell. There he researches steroids and finds out that Impact is Walter Cobb, a family man whose mind was warped by the experiment. As the days go by, Peter works at Bromwell's office, just missing catching up to Impact at his various crime scenes. Finally, Bromwell is called to the ER to help treat some victims of Impact's latest assault. As he leaves, Bromwell asks Peter to not go out for news photos. But Peter has to go out to stop Impact. Arriving at the scene,he finds Impact holding two hostages. The police bring out Impact's wife and kids to plead with him. It appears to work, with Impact releasing his hostages. Peter starts imagining a day when his work with Bromwell will lead to greater things than his web-swinging. Then a shot rings out and Impact goes on the rampage again. Spidey tries to calm him but he is too far gone. After pounding on the wall-crawler for a bit, Impact collapses. Bromwell is on the scene and pronounces the giant dead. As Spidey swings home, he reflects on it all. "Bromwell tells me that I should think about my aunt – like I don't do that enough. Impact shows me that there's a right way and a wrong way to try to help those you love. All these lessons! But...what am I supposed to learn from them? Where's the curriculum? Where's the syllabus?"

A great ending, right? But, oops, there's more! On his way home, Peter realizes that he could be as dead as Impact and decides to give up the webs. But at dinner, Aunt May tells him to keep doing what he's doing if it's what he wants to do. The next day, Bromwell waves the Daily Bugle at Peter, indicating the front page photo Pete took, and tells him he let him down, abandoning his lab work for the very work he begged him to avoid. He tells Peter that he has done all he can and that he's letting him go from his job. Pete can tell that Bromwell is hoping he will ask for another chance but Peter doesn't. He has come to completely understand that he does not become Spidey for thrills but to help people and that Uncle Ben and Aunt May would approve if they knew. Or, as he puts it, "Love the power. Guess I'll just have to live with the responsibility."

Had you told me that a Spidey story (and a prose story at that) about Doc Bromwell witten by Danny Fingeroth was going to be cracking I’d have never believed you.

Fingeroth’s body of Spidey work is a mixed bag to put it kindly. This is the man who wrote arguably the single best page of Mary Jane ever in Web of Spider-Man #6, eloquently summing up her emotional conflict regarding her romantic feelings for Spidey. But this is also the man who editorially mandated the creation of Maximum Carnage.

And yet here he doesn’t make a single misstep.

Okay that isn’t exactly true. His opening narration makes Peter sounds like a goddam psychopath. “Love the power. Hate the responsibility.” Er….that’s not exactly true, Peter has moments of enjoyment of his power and frustrations over the burdens it places upon him. But he doesn’t truly revel in his power and typically treats his responsibilities as simply something that HAS to be done moreso than something he resents doing. But that’s nothing compared to “…to take what I need. And to make anybody who gets in my way real sorry they got there.”

WTF dude! I was half expecting that the twist here was going to be that this wasn’t Peter speaking but it was. Fingeroth nicely bookends these sentiments by the end of the story but that doesn’t change the fact those sentiments shouldn’t be there in the first place.

You can maybe just handwave this as Peter being in a really bad mood and not believing what he is thinking. But I dunno, I suspect the real intent here was to clumsily set up something to BE bookended by the end of the story and more poignantly to smack the readers in the face with the central theme of the story. This lack of subtly rears its head again towards the end of the story when Fingeroth seriously spells out for us that Impact is a dark reflection of Spider-Man and the exact ways how. Everything the dialogue says is correct and Impact is actually a very good reflection of Spidey. But couldn’t Fingeroth have been a tad more subtle about it?

But other than that this story unto itself is pretty much flawless. I say unto itself because through no fault of Fingeroth the story’s placement withint he anthology is kind of weird. It clearly takes place after ASM #33 as there are very direct references and fallout from the Master Planner Trilogy. However the nature of the story also makes it highly unlikely to take place after ASM #39 because in that issue Peter is shaken by Bromwell informing him of just how frail Aunt May is. He pretty much tells Peter that if May learns his secret she will keel over dead. So this happens between ASM #33 and #39 but the Looter story clearly happens after ASM #36. Whilst far from inconceivable that this story could happen afterwards, because the last story with the Goblin was obviously tipping the hat to ASM #39-40 this story would’ve been better placed just before the Looter story. As is it’s oddly the THIRD story in this book to take place in this extremely small and specific gap of time after ASM #36 but before ASM #39.

Enough of the nitpicks though. I said this story was a gem and I stand by that.

What pleasantly surprised me most about this story was that Fingeroth seemed to be able to handle the prose format better than every other writer thus far sans perhaps DeFalco.

He wisely knows to emphasis the inner conflicts within the characters’ heads and play up the soap opera rather than leaning in on the action setpieces.

And yet there are two significant action set pieces in this story. Indeed the crux of the whole story REVOLVES around the physical danger Peter puts himself in by going into action. Fingeroth handled these deftly. The action wasn’t over explained and painted a clear picture in your head but didn’t linger too much. Sure you might feel things would be more interesting if you could actually see things but you aren’t drifting off as the writer belabors the combination of punches and kicks Spidey lands. It’s all very streamlined and designed to support the emotional arc of the story as opposed to the action being the point unto itself or simply the means to REACH a conclusion.

In this regard Fingeroth actually edges out DeFalco. Reading/listening through DeFalco’s story the action scenes can just be boiled down to Spidey fights some thugs, drags out the fight for pictures and then one them accidentally dies the specifics don’t matter even though we do get them.

Here Fingeroth forgoes the specifics to simply give you the broad beats to the fight (Impact throws a car, Spidey webs people to safety, etc) whilst ensuring he returns to Spidey’s inner thoughts and peppering in dialogue that is moving the plot and exploring the themes, even if it is simply lightly.

In a way this is a rare example of an action set piece that works BETTER in prose than it would visually. Sure Mark Bagley or Ron Frenz could embellish the fight scene to make it look cool, but the visions of a possible future Peter imagines are more potent and organic when we simply read his train of thought like this. Were it a comic such dialogue would come off as excessive or (if communicated through art) needlessly existential. Additionally as a villain goes Impact is fairly generic, but having him not have any visual presence mitigates that because his importance is more about what he is doing and why than having a dynamic appearance.

To go back to Bromwell, he’s developed more here than he’s been in over 55 years of Spider-History. Were he written like this in his appearances he might’ve become a more beloved character. What’s great is how organic his personality feels. We learn new stuff about him but it feels like a totally logical extrapolation of what little we saw of him in the 1960s. He is a quintessential doctor and Fingeroth lends him a surprising amount of nuance. He isn’t endlessly caring, he has his limits but even so the fact that he wanted Peter to ask him for a second chance at the end was a brilliant touch. It’s a small moment but it helps make Bromwell feel more multidimensional.

And because of this characterization the story earns the pathos of Peter letting him down. You feel sad for Bromwell and for Peter that things didn’t work out for both of them.

Aunt May is also done very well here. She is in typical Aunt May mode but Fingeroth chooses to make that the central conflict of the story rather than a background element. Refreshingly though the issue isn’t that May is on her deathbed, but rather the impact (if you pardon the pun) upon her if anything happens to Peter. The story is almost a spiritual cousin to JMS’ opus ‘the Conversation’ in that it comes to a reasonable and positive resolution.

What in particular what holds this all together is the brilliant (yet rarely used) idea of treating Peter’s cover story as Spidey’s photographer as a metaphor for him being Spider-Man. It’s something that’s pretty clever when you think about it because the cover story means his loved ones go into relationships with him knowing he takes risks and potentially endangers them, just as if they knew he was Spidey.

Through treating the cover story as a metaphor Fingeroth is able to have Peter get a lot of feelings about being Spidey off of his chest. This chiefly comes in the form of his bookeneded confrontations with Bromwell, his angry (and highly unjustified) outburst at the start and his quiet resigned acceptance at the end.

Perhaps the best bi of narration in relation to Peter’s character was when Fingeroth spelled out that Peter might enjoy being Spidey but even if he didn’t he’d do it anyway because he was hooked on helping people. It eloquently emphasis the innate heroism and core of the character. And it does so in a nuanced way too as too often writers have Peter outright hate being Spider-Man or else cynically lean on the idea he’s a thrill junkie of some kind. Fingeroth gets that peter DOES like his work but that isn’t the reason he does it.

Nuance is actually the key word here. There is a lovely sequence where the story acknowledges that Peter might subconsciously be avoiding Impact out of a loss of confidence. It plays very realistically. How often in life has one bad moment shaken us up and made us hesitant to do things we previously did without even thinking about it.

Really I don’t know what else to say about this story that isn’t self-evident by just experiencing it for yourself.

Tiny issues aside it’s really quite excellent and highly recommended.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

book reflections: Confessions by Minato Kanae

Confessions

The heart of this book deals with revenge. It's a familiar theme: when a heinous crime has been committed, are criminal justice procedures ever enough? To what degree is revenge, personally exacted, justified?

Confessions complicates this question by throwing the spikes of tension between children and adults.

Children are such a fascinating subject of study—not to go too far into it, but “childhood” is very much a socially constructed phenomenon (my formative understanding of this is Kathryn Bond Stockton's The Queer Child, which narrates a history of adults-depicting-children, and the values and anxieties that reveals). Confessions asks the question, “what happens when children commit heinous crimes?”

The book begins with a monologue by middle school teacher Moriguchi on the last day of the semester. What first seems like philosophical rambling lays out a multi-layered social phenomenon.

Layer one: social inclination to believe that children are always the victim, never the perpetrator. This is outlined in the story about the teacher who was called out by a female middle school student seemingly in need of help one night, then accused of sexual assault. The student later confessed it was because she wanted revenge—the teacher had scolded her for chatting during class. The teacher was forced to reveal, under these circumstances, that she's trans, and that she had no designs on the student in question (which is certainly a narrative choice to think further about—the quickness of the anecdote and the inherent logic it's meant to convey, that simply by proving herself a woman, the teacher convinced her coworkers that she's exonerated of all suspicion. At least trans identity isn't being inherently linked with deviance?). The teacher was still fired, and the school instituted a new policy that should students ever call teachers for help after school, only male teachers can go to male students, female teachers to female students, etc.

(The narrative, in its determination to gesture to the incapability of institutions to fulfill human needs, uses this as the ignition point for Naoki's unhappiness with Moriguchi.)

Layer two: children receive public anonymity in the court of law, meaning punishment is dealt in secret, and presumably, they can return to society afterwards carrying none of their criminal history. This is outlined in the “Lunacy” case, where a young girl kills her own family with cyanide, after conducting a series of experiments on what poison was most effective. The case got plenty of sensationalist press coverage, but where is the girl now, Moriguchi asks. Has she gotten her punishment? Was justice ever exacted?

Layer three: sensationalist press coverages without embedded moral value only teach children the outliers. At worst, it teaches children that this is the way to get attention (which is precisely what Shuya and Mizuki took from the Lunacy case). Moral outrage loses ground to morbid fascination, becoming worse than an empty gesture; like the teacher who replaces Moriguchi, posturing as some beacon of moral justice is merely for self-satisfaction.

Maybe, more accurately, the book wants to know, “how do you punish a child?” Some, like Moriguchi's not-husband, like Moriguchi insinuates the juvenile criminal justice system to be, answer, “you don't.” Children are products of their environment, so the ones who should be punished are the teachers (as posited by the “Lunacy” case and the chemistry teacher who got all the public blame for giving the child access to cyanide). Alternatively, children are still learning and growing. Moriguchi's not-husband was quite the problem child himself, but he turned things around and became the most truly moral figure of this entire book. He believes in the capacity for change in children.

But Moriguchi doesn't care much about that. Shuya and Naoki plotted to and killed her four-year-old daughter. She wants revenge.

What makes her fascinating as the central figure of this book is her clarity of mind. She isn't someone who's lost herself to vengeance; she systematically identifies the flaws (or what she thinks of as flaws) in the juvenile criminal justice system and then chooses her own revenge. On one hand we have the empathetic response to a mother losing her child, and the willingness to let a fictional character play out, for emotional catharsis, something we might not necessarily endorse in real life. On the other hand we have the unease of her turning this calculatedness toward children: Boy A and Boy B, middle school students.

(Cue comparative cinema studies of the 2010 Confessions film and 2007's Boy A. Oh, apparently Boy A is based off of a novel as well?)

Oh, and then she does take her revenge. She says she's laced Boy A and Boy B's milk cartons with HIV-infected blood.

And now, in what is the true brilliance of the book, Confessions starts to give us other perspectives. We get Mizuki the perfect student, who is first victimized by the hoard of angry classmates (and it's such a consistent literary and real life theme I guess, the cruelty of a mass of children). We get a peak into her questionability in a somewhat tender moment though: why does she just have a poison-testing kit lying around? In this section, we also get a protagonistic portrayal of Shuya; it's not that we doubt Moriguchi's version of the psychopathic-child-inventor Shuya, but now he's the martyr (as per the title of the section). He quietly suffers the bullying of the class, tells Mizuki his negative blood test, and becomes “genuinely” happy at Mizuki's compliments, saying all he's ever wanted was that acknowledgement.

Mizuki also bares her teeth against the new teacher, accusing him of being the cause of Naoki's mother's murder. At this point, it was almost narratively heroic, after we've suffered the annoyance (through her perspective) of the self-important teacher. But afterwards, in Shuya's section, we hear her confess to wanting to poison that teacher for “ruining Naoki's life.” She's killed by Shuya before we hear more, but might that have played out? How much do we fear the mental criminality of children?

We also get Naoki's sister and mother's perspective. We get a doting mother insistent on the innocence of her child, making excuse after excuse for Naoki, even when Naoki's fully confessed to throwing Moriguchi's daughter into the pool. How much responsibility does a parent have toward her child? Does she hold ultimate faith in him, stand staunchly at his side in support of him? Does she do right by the society (and in theory by her kid) by turning in her own child? We were meant to be annoyed by her cruel insistence to blame everyone but her son, but we see in Naoki's section right after that his sanity relied so much on this idea that his mother unconditionally loves him. He believes that, once he's gone to jail for his crimes, he can do his time, reform and return to society as long as his mother is there to love and support him.

Of course, that's when his mother decides to kill both him and herself—a murder-suicide for her failure as a mother.

(It really does haunt me, thinking about Naoki and his stymied possibilities. He killed Moriguchi's daughter in a moment of callous spite, motivated by a desire for revenge against Shuya's dismissal of his overtures of friendship. He lived in such a tortured state for a long time, a child grappling with the terror of impending death by himself, terrified of infecting those who love him. His instincts, when he emerged into the real world again, was to weaponize his “infected” blood. Yet he ended up on such a hopeful incline—mother's love with save me. All this happens as his mother spirals downwards, coming to terms with her own child's monstrosity. The book seeds Naoki's redemption, but takes the sprout away before we can see whether or not it carries infection.)

Finally, we get Shuya's story. I fully bought into it, as I was expected to. The book gestures multiple times at his ability to pen a convincing narrative of innocence. Or at least, a narrative of the anti-hero. He walks us through his absolute love for his mother, the engineering genius. She gave up her career for him, but then turned that dissatisfaction into abuse. Abuse turned back to gestures of love when she was found out, divorced, and forced to move away, and Shuya held deeply on to his faith that he will be reunited with her again. The desire of a child for his mother's love motivated the murder of Moriguchi's daughter, the planting of a bomb at the school festival. It ended up killing Mizuki as well.

Moriguchi bookends this tale, tying up loose threads. Yes she absolutely put the blood in their milk, but it was her not-husband that swapped out the infected cartons. Yes, she wanted to destroy Shuya and Naoki's lives; it won't bring her joy and it won't bring her daughter back, but nonetheless she wants her vengeance on the two boys. The possibility that she was only scaring Naoki and Shuya, that she threatened to but never did anything actually immoral, is completely swept away. She tells Shuya she visited his mother and told her all of his crimes. Baiting Shuya with what his mother said, she instead tells him that the bomb he planted had been deconstructed at the school and reconstructed in his mother's lab instead. Making the bomb and detonating it had both been Shuya's choice.

Shuya had killed her daughter. Now she's killed his mother.

(But did she? I have no doubt she did, but this book doesn't deal in absolutes.)

So—what are we left with? A psychopathic child inventor-slash-murderer motivated by a desire for maternal love? A girl who admired another murderous young murderess and wanted a turn of her own with poisons, murdered before she could prove herself either way? A cruel and reactionary accomplice who came to the conclusion that he had done something wrong but that he could repent? A mother who refused her son's criminality until the very last moment, and believed they were both beyond salvation? Another mother who took justice into her own hands by ruining the lives of two young boys who killed her daughter in cold blood?

...Is there such a thing as cold blood in this novel? Every “cold” act was done with passionate motive: Shuya wanted to prove himself to his mother, Naoki wanted to prove himself better than Shuya, Moriguchi wanted to give her daughter proper vengeance. HIV is the symbol here of criminality, first given, then saved from, then weaponized by both boys. There's so much, with the blood! Naoki coming to terms with the infection he didn't have made it possible for him to confess the truth, to start himself on the path toward salvation (even if it only lasted a few pages). Shuya embracing the infection right away because if he were dying his mother would surely come back; losing that possibility of death led to him befriending, then of course in the end murdering Mizuki.

Shuya plotted the murder of Moriguchi's daughter, but wasn't actually responsible for the cause of death. Naoki was the accomplice, but at the last moment, made the choice to actually extinguish her daughter's life. This murky twist of motion and motive (Kathryn Bond Stockton!) would prevent them from getting the full punishment of homicide in a juvenile criminal justice court, as Moriguchi explained. Now, because of the blood, they've both committed an inarguable murder with their own hands. Naoki loses his mother and his entire world order that revolved around her unconditional love for him. Shuya's murderous inventions are never allowed to succeed, and he never gets to “prove” his genius, until it was used to kill his own mother, the one person he wanted acknowledge from and to live with. The punishments are incredibly cruel—but are they justified?

#kanae minato#confessions#confessions (2010)#this is really an insane book lmfao#i loved every construction of it and could probably#spend a lot more time constructing an academic essay bout it#comparisons of it to gone girl are fucking right#the same complicated treatment of women and criminality#but this one is a lot more haunting tbh cause it deals with children#in such a full and complicatedly emotional way#spoilers

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Love, Simon is a romcom/drama about Simon, a teenager in the closet, and his journey to a more open self, while pursuing the love story that he learns he deserves.

*intermediate few-spoilers review*

I haven't read the book on which it was based, so this isn't a comparison of book and film, just a pure review for the film itself.

There is nothing new about the plot... but at the same time, everything is special about it. Let me explain.

What truly makes this film so special is the act of coming out. It is such a central theme to the film, that most of its greatness relies on that.

The events in the plot are all typical, but all of these are saved by the infused theme of coming out. The events in the story highlighted the importance of finding acceptance, and courage, and trust, and openness — especially when taking steps to reveal yourself to the world.

See, a penpal whom the protagonist develops a crush on: it isn't anything unique in a love story, but it is special because of the way Simon and Blue drew courage from each other in taking steps toward being accepted.

The love triangles: all cliché and super predictable, but special because it isn't actually the love triangles that are being showcased — it is Simon's internal conflict between trusting the people around him and manipulating them.

Yes, Simon was manipulative, and his secret doesn't excuse that. But to my understanding, (and I draw from past experiences here), he was scared, desperate, confused about what he should do. It would be so much easier if everybody just knew; that way, he can't be blackmailed. But at the same time, it's not easy at all, because it takes so much of you to allow yourself to be vulnerable to the world.

Seeing this single conflict take control of the development of other characters was amazing. It portrayed powerful substance in Simon's struggle for secrecy, along with its outward influence. But as amazing as it was to see it, it sort of sucks that his friends treated him more harshly than he deserved, especially at a time when he needed them.

And when Simon finally was vulnerable, Nick Robinson did a wonderful job in portraying Simon's emotional ride: his initial fear and how he takes it out on his sister, his frustration and hopelessness as he breaks down on his bed... and my personal favorite, his anger at Martin.

School life didn't make things easy for him, so it was a delight to see his family taking up an active role in supporting him, each member with their own way. The portrayal of these things matters, because parents and kids alike could learn new ways of expressing themselves. Hopefully, this sets examples of love, acceptance, and mending for people throughout the world.

I guess I see why some people might not see what is special in it; it might be a cultural gap. Some people might only see the clichés, without our experiences to help them perceive the greater depths.

The film resonates with me, because aside from inspiring a lot of other people I know, it taught me lessons too, even if I haven't really spent much time in the closet lately. I let others push me around sometimes, in the way that I barely stand up for my right to decide whom I tell. Simon taught me that it is my thing; Simon taught me that my identity is mine.

8/10

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Continued: Eight Impressions from Albania

<Part 1 of this post is here>

Journeys

I had started in the port town of Saranda, on the south West tip of the country, half an hour by boat from the Greek island of Corfu, one of only a handful of ways to enter Albania. A town of cheap mussels freshly-caught and cheaper backpacker lodges, from which there were two roads out: one snaking up the coast towards Vlore, and the other East, across hills towards Gjirokastra and Permet.

I took the route east, going first to Gjirokastra and its hillside of Ottoman-era landowner houses, the birthplace of the great Albanian historical novelist Ismail Kadare, where I spent a couple of days wandering, and then on to Permet to meet Cimi. The terrain was not insurmountable, but still it held the upper hand and told you how you had to proceed: gently, in daylight, towards the next pass, the next trough between the ranges, the next crossing where the mountains dipped. So that an as-the-crow-flies distance of 10 km would become fifty or seventy on the road, and two and a half hours or more on the unhurried buses.

Bus stations were no more than a clearing in front of a centrally-located shop or cafe, and buses advertised their route by way of the driver screaming out place names. Once the driver had hustled enough people into his seats the journey would begin along the river valley, the passengers mostly quiet but not the bus itself, which played music or videos of alternately lilting and gyrating Albanian folk music.

Flat ground is precious in this mountainous country, and our bus would soon leave the coastal plain or the valley and begin crawling up the mountainsides. Then around one of those hair-pin bends it would screech to a sudden halt at a turning. Turn around and peer out and you would find that this was where one or more mule-tracks met the road. Here one or two patiently waiting men would swing into action, unloading a crate of spinach or cherries or a sack of grain off the back of a mule or donkey, loading it up into the back of the bus or hoisting it onto the last row of seats, with instructions to the driver to unload it at a waiting mule at the next town along.

An unfamiliar sight in modern Europe maybe but familiar to me, reminiscent of the once-a-day buses that wind their way through the mountain villages and tea estates of the Western Ghats near where I grew up.

--

I reached Permet the afternoon before our 5-day hike was due to start. It was, looking one way, like every riverine mountain town from where treks begin: where one arrives the afternoon before, looks anxiously for shops to purchase last-minute supplies, breathes a sigh of relief to find them, looks for a more-elaborate-than-usual sitdown meal at a riverside eating house, and spends the rest of the evening in a quiet thinking of what is to come.

For five days Cimi and I walked together in the mountains and valleys around his hometown. Along the Zagoria valley, unconnected by road, on that first day to Limar, then across the mountains and down towards Permet in the valley of the Vjosa river on the second. Into a designated National Park of Macedonian-native fir trees called the Bredhi i Hotove on the third, he deftly ensuring (in spite of our liimited shared vocabulary) that we kept up a loud-enough conversation to keep the bears away. On the fourth morning along the Vjosa again on the other side of Permet, crossing an Italian-era bridge to the village of Petran, stopping at some thermal springs for a dip before a steep climb to the beautiful mountain village of Benje to spend the night. Then on the fifth day taking shepherd's-only trails across the low mountains back to where we started, Cimi expertly cowing down with the ferocious sheep-dogs that we encountered on the way.

Growing Pains

Over the next week as I made my way from village to small town to regional city to metropolis other things betrayed their familiarity too.

I had left the south for Berat, in the centre of the country. It had the feel of a regional capital and also of a past glory, with its snazzily-dressed old men out for their Xhiro - stroll - in the evenings once the sun had lessened in intensity.

By the river rose this neo-Classical building, standing taller than all others, at a scale and opulence out of place in the Albania I had seen so far:

It was home to the University of Berat. Finally! I thought, for one of the things that had begun to pique my curiosity was that I had not seen any evidence of an institutional or professional middle class of people yet. Now in Berat I would find an intellectual atmosphere that grows up around a University city: professors, artists, researchers, library cafes, students who would form the next generation of this group of people: maybe even young people in one of these cafes who could speak enough English to have an involved conversation with.

Only to be told that the University had been shut last year. Why? The reason was incomprehensible to the Danish girl sat next to me listening to the story but perfectly understandable to an Indian: a huge "pay to pass" scam had been unearthed in almost all the private universities that had mushroomed in the regional centres of Albania since the fall of Communism and the sudden rise of private enterprise. It was an open secret, but the scam had finally become too big to ignore, and a couple of years ago all these universities had been shut down. And now Berat, and small Albanian cities like it was back - at least for young people with higher ambitions - to how it used to be, and at 18 they had no option but to compete for limited places in the capital's public universities, or stay at home. Growing pains, and as I watched the young folk whiling away their time in Berat's riverside cafes I saw them differently after this.

"The News"

The long bus ride to Berat inland from the coast reminded me also of other Balkan journeys, in Croatia over the winter in a modern two-carriage train winding up from the beautiful coastal city of Split to the capital, Zagreb: six hours through a white, frozen country: fields, trees, shrubs, lakes and rivers all iced over with stalactites dangling. After skirting the beautiful Plitvice Lakes National Park we arrived in human habitation after what seemed like hours: this was the small hillside town of Knin. Amazingly my phone instantly picked up a 3G connection, so I decided to look Knin up.

“Before the Croatian War of Independence 87% of the population of the municipality and 79% of the city were Serbs. During the war, most of the non-Serb population was ethnically cleansed from Knin, while in the last days of the war the Serbs were killed or ethnically cleansed from Knin by Croatian forces”.

I closed the page shut, the train still on the platform. Gory stuff indeed, but that wasn't the only reason why I wanted to stop reading. There was something unfair about the whole business: that this town of Knin with its wrinkled old man bidding goodbye to his wife on the platform just now and its row of peculiar houses up the hill, being still associated so singularly on Wikipedia with this act of inhumanity of twenty-three years ago.

And in the smartphone age, of course, there are newer and ever more pointed ways of accessing the sort of thing that becomes news. And who wrote that article on Wikipedia? It is very difficult to imagine that it was a Knin local (of whatever stripe, Croat, Serb, or Bosniak). Who wants their own town to be committed to writing for the world to see in this way? How would a Knin local have described his town instead? That it has a beautiful Orthodox church at the top, that they once heroically resisted the Ottomans (a fairly unifying, common theme right across the Balkans I've learned), that there are two folk songs which have lines that mention the beautiful young unmarried girls of Knin? I wouldn't know, I am only guessing here, but perhaps something like this, with an addendum, in a low voice if such a thing can be represented in the cold words of a Wikipedia article, of the ethnic strife that once visited this town twenty years ago, and has now left.

It must have been for reasons such as this that I avoided reading or watching anything about Kosovo (an ethnic-Albanian majority state to Albania's north-west) during my time in Albania, even though I remembered it being briefly in the news earlier this year. The only time I heard Kosovo mentioned on this trip was a girl in a bar in Tirana, who said, "They're Albanian too, but because their communism was not as strict they're more exposed to other cultures than us. There is some great music there, You should go to Pristina and Prizren next!". I enjoyed hearing this positive impression of that country then, and when I do visit, I would much rather keep her suggested way of looking at Kosovo at the top of my mind, rather than images of past wars and present conflicts.

All Together

As we passed this riverside graveyard outside Permet I asked Cimi, "Is this a Christian cemetery or a Muslim cemetery?"

"Both", he said. "All together. We have no problem".

All through my trip there had been hints of this easy secularism and coexistence in this nominally Muslim-majority country. In the South where I spent most of my time a significant minority were Bektashis, a Sufi sect with its origins in Turkey.

Below a Bektashi shrine and mausoleum on the grounds of Gjirokastra castle. The South was dotted with these little shrines, as well as traditional Sunni masjids and orthodox churches. None of them, even in the bigger towns and even the Sunni ones during namaz, had anyone inside.

There is historical probable-cause for this: Albania's communist doctrine had banned religion, destroying mosques and churches ("One of the few good things that the Communists did", Cimi quipped), and encouraged a pan-Albanian identity. But even that does not fully explain this religious intermingling. In earlier centuries, with Ottoman conversions, when entire villages converted and re-converted to one or other Islamic or Christian sect often for purposes of protection and tax relief as much as religious calling, people were said to remember and trace back their historical clan-lineage more than their religious leanings. This too over the centuries kept religious difference at bay.

And now? Many people I spoke to, Shamsi the waiter, Cimi himself, self-identified as religiously liberal or atheist: usually spoken of just before downing a strong glass of Raki, or in describing their family: Cimi's wife is Orthodox, and his siblings' spouses fall on every side of the coin: Sunni, Bektashi, Orthodox Christian, Catholic.

They were familiar with global currents on this too, of Islamic fundamentalism around the world, and made the point of how they were flummoxed by it. And again, our limited shared vocabulary prevented a detailed discussion, but what they seemed to say was this: This is how we've always been. It is possible to be this way. In the rest of the world strange things are happening with religion. We find that odd.

Modernity

Time and again, people spoke of how they felt their country was 'backward', that 'things have to change', that there wasn't enough opportunity for them and they were forced to emigrate. It is difficult to argue that last point (remember the shut Universities up and down the country), but there is certainly modernity in Albania, modernity in its most profound sense. Take the story of Hoxha and his Bunkers:

Enver Hoxha took over as leader of Albania's one-party Communist state in 1944 and, over the next forty years, cemented his position as Supreme Leader. His brand of Totalitarian rule was too much not just for China (who broke with him in the early seventies), but even for the mother country the Soviet Union, who Hoxha condemned as deviated from the fundamentalist line. Over time he built all over Albania a series of these "spying posts", both above and below the ground, on streetcorners, hillsides, and nooks everywhere. Many of these still exist:

During the second half of his reign he built two series of underground bunkers in the capital city Tirana, one right underneath the Ministry of Defence and Parliament, and the other, more elaborate construction, complete with an underground Parliament Hall, a few miles away. They were built to withstand chemical and nuclear attack. I spent a few hours each in both, and they are masterpieces of claustrophobia, paranoia and stale air.

What is more incredible, though, is what has been made of these spaces in the years after the fall. Here is the entrance to this space, dynamited into the hillside:

What followed was a reconstruction and preservation of the highest order, encapsulating and committing to permanence and memory the worst excesses of the regime, and for the visitor without any loss of the eeriness.

Enver Hoxha's underground quarters:

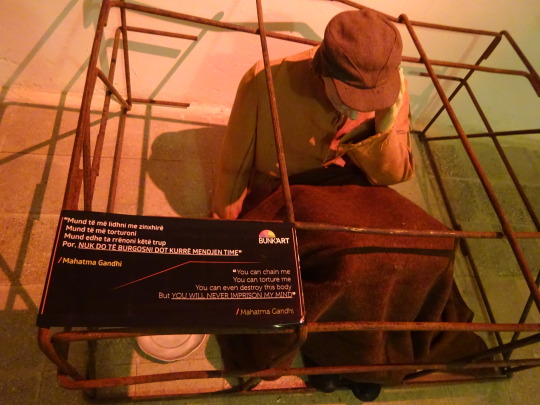

The preferred holding cell for dissidents and political prisoners:

The photographs are of those who lost their lives as part of the regime's political purges. A voice called out the names of the deceased.

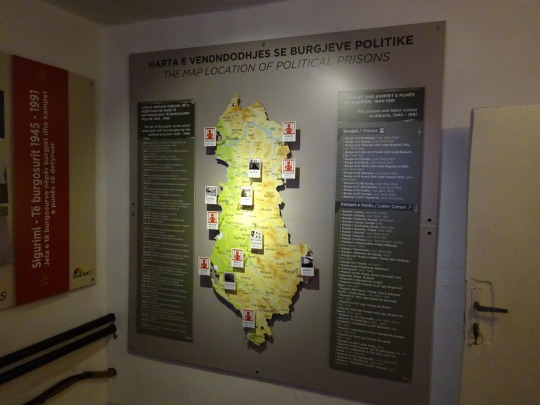

Political prisons and concentration camps were set up all around the country:

Dogs were trained to hunt, maim, and kill, to guard the borders:

It is difficult to capture in photos how eerie the experience was. Often it seemed inappropriate even to click pictures.

I had read about the Bunkers even while in Permet, and asked Cimi if he had ever seen it.

"No, but I have heard about it. I cannot go. It is too painful for me".

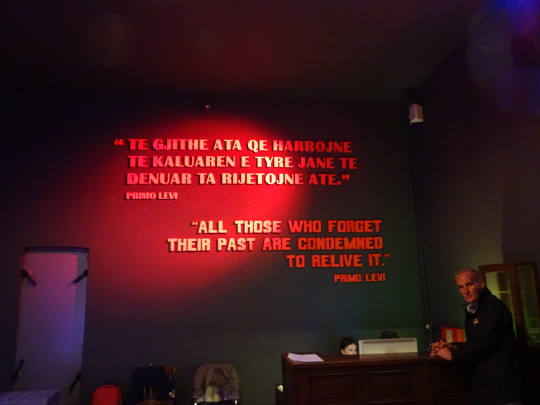

Cimi wouldn't, but many Albanians were there on the days I visited. This museum-visit was no daytime stroll, neither was it entirely academic. The young, but especially the older, had a quiet intensity as they slowly made their way through the dank corridors. Some were close to tears.

I wanted to scream out when I emerged from the bunkers into the sunlight: This is modernity! This is progressiveness! A memorial to past mistakes and madnesses that many countries and people around the world - including our own - struggle to acknowledge even happened, let alone bring out with such forthrightness and honesty for themselves and the rest of the world to see. What a towering achievement Albania's Bunkart is!

Cimi

This is Sotir, Cimi's father-in-law.

A retired schoolteacher, he lives in the beautiful mountain village of Benje. We had trekked 17 km that day to reach it. We spent the night there. All evening he kept pouring the Raki, and kept bringing out the plates of cheese and salad to go with it, and kept the folk music playing loud on his battered old tape recorder, and danced.

And below, Cimi:

1 note

·

View note

Text

Vanilla Sky is the Weirdest Remake I’ve Ever Seen

All things considered, I hold a lot of respect for remakes. Sure, it might seem like a waste of creative potential to throw a bunch of money and artists on a project that’s a copy of a previous one, but remakes can “reinvent” the film that came before it. Updating the special effects, correcting problematic stereotypes, retelling an important theme, yadda yadda, you get the idea. You may notice that all those excuses for a remake I listed were based on the remake being made a long time after the original. But Vanilla Sky was released just four years after Open Your Eyes, the film it was based on. It even shares a main cast member playing the same role. So...what’s the point in remaking it? According to director Cameron Crowe, it was to bring the story to an American audience while weaving it into a new story. According to me, a viewer of both films, it was to make the same film but slightly worse in every way. And wouldn’t you know it, when everything’s a “little worse”, the quality of the film as a whole drops a lot. First and foremost, the central theme, plot elements, characters, and even most sets are near-identical to Alejandro Amenábar’s original film. So any changes are mostly in things like dialogue, shot composition, and editing. And honestly, the only thing I’m thankful to Vanilla Sky for is birthing the very memorable movie quote “In another life, when we are both cats”, but even that is far less interesting in context. I’d like to clarify that I’m certainly biased by having watched the original film first, but I’ve done my best to focus my analysis on the formal elements specifically.

Why don’t we start with the respective protagonists? The story opens with the introduction of Cesar in Open Your Eyes, and Tom Cruise in Vanilla Sky, although I’ll probably call him “David” for the rest of the review. Both are fundamentally the same character; they have the same nightmares, sleep around without much care for the women in question, were born rich, and are paranoid about other shareholders trying to steal his company. There’s a few key differences between them though, and it mostly comes down to acting. Cesar is portrayed as a complete douche. He brags about lay he gets, talks rudely to them, values his vanity above everything else, and is just generally...rude, if such a word isn’t too crass. Tom Cruise is unmistakably Tom Cruise, and despite also being a player, he’s also more, well, playful. He seems to form at least some kind of emotional attachment to the women he sleeps with, tries to keep their identities secret from his friends, he doesn’t come off as exceptionally rude, and there are even a few scenes of him being sentimental to friends to teach us “he’s not that bad a guy”. This is the change I most expected, but it’s still one I wasn’t happy to see. The repeated attempts to make the protagonist “relatable” only made him seem two dimensional. Instead of being an enigma, a character with clear flaws, he’s a character who has his depth plainly told to us. The side characters are all pretty much the same, with one notable change to Sofia, the main love interest (who shares a name and actress between the movies). Sofia is a reluctant love interest, who seems to see Cesar as her date’s annoying friend, although some flirtatious subtext can be picked up. Vanilla Sky’s interpretation has her completely fixated on him quite literally from the second they meet. I assume it’s done to make the relationship more “believable” or “charming”, but it really just makes Sofia static, and reinforces tired tropes about “true love”. It comes off as especially cheap at the end of the film, actually undercutting the theme of the story as a whole. All of these changes, while relatively minor, lead to massive overhauls in tone and dramatic tension.

Why do I care so much about that? Because Open Your Eyes is a brilliant psychological thriller, which induced a lot of genuine stress and discomfort in me while watching it, more so than any horror film I’ve ever seen. Suspense is constant even throughout the calmest or happiest of scenes. With long shots, a lack of music, and occasional discontinuous cuts in time, the film conditions you to never trust what’s coming next. Once a shot begins to linger, you start to worry about what’s going to go wrong: Sometimes there’s an abrupt cut, a shocking image, maybe even a tragic twist, but often, it’s nothing at all. You start to question your own sanity just as you do Cesar’s. The cost of Cameron Crowe wanting to make you like Tom Cruise (which is kind of easy because he happens to have Tom Cruise’s face) is that you no longer question him or his sanity. And the editing changes to match this change: cuts don’t waste time, and there’s always something happening. Sometimes there’s legal mumbo-jumbo, or banter, or a musical sequence, but you aren’t given any time to savor these moments. You don’t get to think about how happy Tom must be in a moment of levity or character development, because we’re already watching him have another conversation, or having pop music blasted at us. Open Your Eyes generates a sense of tension and unease that’s able to penetrate even the most mundane or harmless of scenes, while Vanilla Sky creates an aura of, well, ease, that it betrays any dramatic tension.

Just so you don’t think I’m talking out of my ass, I’ll break down how two versions of the same scene demonstrate this change: the prison portrait scene. In a flashforward to Cesar in a prison cell being visited by a psychologist, we see him repeatedly drawing a portrait of a young woman. The psychologist questions him on the matter, but Cesar doesn’t share much, lamenting about it being a happy memory. Shortly thereafter, we’re introduced to the subject of the portrait, Sofia, and see the game the two of them play, drawing caricatures of each other, giving new context to the prior scene. In Vanilla Sky, the two characters sketch each other before we see Tom redoing the portrait in prison. And in that prison scene, a somewhat glowing, superimposed Sofia is shown inside the jail cell, interacting with Tom and serving as the model for his drawing. That change does two things to the viewer’s impression of the character: it makes Tom’s state of mind explicitly clear to the viewer, and it directs our attention to the obvious hallucination, instead of the bond between Tom and his psychologist. When Cesar was questioned on him compulsive drawing, we’re put into the psychologist’s shoes, wanting to learn about him, which helps us get invested in wanting to see the two characters come to understand each other. Vanilla Sky’s version of the scene brings focus to the cheap trick and breaking of reality, making the dialogue a backdrop rather than an investing subplot. And that’s just one of many scenes to do changes like that.

I guess my conclusion here is that Vanilla Sky is overrated, and Open Your Eyes is amazing.. So, uh, don’t let me spoil it for you, go watch Open Your Eyes sometime, it’s fantastic. Maybe we’ll all be able to appreciate the underrated gem, one day, when we’re all cats (See? It really is just too damn quotable)

0 notes