#(camera as in the. narrative camera. the scene-shooting camera. the fourth wall)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Whumpee looking at the camera, mouthing "you hear this guy?" in the middle of one of Whumper's rants.

#defiant whumpee#whump prompt#ok it's very much not. this was just a silly thought#self aware whumpees my beloveds#(camera as in the. narrative camera. the scene-shooting camera. the fourth wall)#though it'd be fun with a Literal Camera#sorry whumper your 'material to make team leader speak' has to be discarded#on the basis of you kidnapped the little shit#happens to the best of us

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rewatching Teen Titians Go! To The Movies again (i watched it 3 days ago) and this is literally DC’s Deadpool and Wolverine (and it came out first) so I’m gonna compare them while spoiling Deadpool and Wolverine the least amount possible

The “obscure” character references:

•Challengers of the Unknown

•The Atom

•“That is where the Animaniacs live” (not DC but still Warner Brothers sort of like Marvel and Disney)

•Literally almost everyone in the background of the movie theater scenes

Poking fun at their old movies:

“There was a Green Lantern movie, but we don’t talk about that one”

“My mommy’s name is Martha too”

“Shooting a baby into space what kind of people are you?” “You are the terrible parents!” (referring to superman’s biofamily) + Krypton being saved with EDM

“Golly thanks for taking me to the movies in this dangerous neighborhood, Dad” (Batman’s parents died in crime alley)

The themes of found family

•It’s repeated several times that without Robin, Beastboy would live in a dumpster, Starfire would have to fight in alien gladiator battles, Raven would have to enslave entire planets with her dad and Cyborg would have to play professional football (which he dislikes)

Referring to their characters as characters from the Marvel

“He should be saying he’s not me, I came out like way before him.” “Nah, I’m pretty sure you’re Deadpool.” (this is a whole scene btw and Slade’s intro)

Breaking the fourth wall:

•”Look into the camera and say something inappropriate” (again when calling Deathstroke Deadpool)

•”The prefect plot device”

•Stan Lee’s cameos

•”KIDS! ASK YOUR PARENTS WHERE BABIES COME FROM”

The Meta dancing/songs

•”You need a Upbeat Inspirational Song About Life”

•My Superhero Movie

•Previously mentioned EDM music

🚨🔔 ACTUAL SPOILERS FOR DEADPOOL AND WOLVERINE BELOW BEWARE!!! 🔔🚨

The meta narratives are the main similarity however, in Deadpool and Wolverine the whole “anchor being” thing is just a joke about how Fox’s media company literally died because Hugh Jackman was no longer there to bring them in the big bucks. In Teen Titans Go! To The Movies the narrative is all about the Teen Titians (Go!) characters being too unserious to get a movie, a real complaint people have had since the inception of their show.

Plus Robin and Deadpool both have abandonment issues and low self worth, Robin has a weird Lion King dream where Batman drops him off a building after other superhero’s disapprove of Robin. Deadpool secretly worries that Vanessa doesn’t love him or something???

Also both have the two main villains turn out to be in cahoots in some way, in Deadpool it’s revealed that she works for the TVA, and in Teen Titians Go! To The Movies Slade and Jade Wilson are the same person

#teen titans#teen titains go#i feel like they get unnecessary hate when the humor style is literally kid friendly deadpool#dc#detective comics#teen titians go to the movies#deadpool and wolverine#media comparison#deadpool#i think this would be better if i rewatched deadpool to pull quotes and i might later but 🤷

27 notes

·

View notes

Link

Like most good stories, Harry Styles’ video for “Treat People With Kindness” starts with Fleabag, specifically with a meeting at Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s hit London theatre run, which became the launchpad for the joyous black and white video, released on New Year’s Day.

Working with a team now synonymous with Styles' videos (choreographer Paul Roberts and stylist Harry Lambert, to name a few), it was directed by brothers Gabe and Ben Turner (part of the production company Fulwell 73), whose work has spanned One Direction videos ("Steal My Girl", “History”) and Styles' solo track “Golden” and who produced the documentaries I Am Bolt (2016) and Hitsville: The Making Of Motown (2019).

Here, Gabe and Ben tell us the story of when Harry met Phoebe and how “Treat People With Kindness” came together.

Gabe, you tweeted that the video was shot at the beginning of last year. How did it come together?

Gabe Turner: Harry and I went to watch Phoebe do her live Fleabag show in London. We met Phoebe and she was the kindest, most delightful person ever. The next day I was watching dance videos randomly and one of them was this Nicholas Brothers video from the 1920s. It was two brothers dancing. I said to Harry, “You and Phoebe, question mark.” And he messaged back saying, “Treat People With Kindness”. Then he called Phoebe and was like, “I've got this song. I want to do a video. What about me and you doing this dance routine?” And she was like, “Great." And then the two of them called Paul Roberts, the choreographer.

Ben Turner: This isn't always how our life is. This isn't the regular process. But once the touchpaper got lit, it just went off. Every now and then something comes along where all the dominoes fall perfectly.

GT: Harry and Phoebe worked with [choreographers] Paul Roberts and Jared Hageman. The four of them rehearsed all the time, remotely, wherever they were. Whatever projects they were doing, the choreographers would go with them and work on their steps. We would get sent video updates for them as they were rehearsing and learning. We were like, “This is amazing.” We had been to the Troxy for the Bugsy Malone Secret Cinema, so we were like, “That would be a great place to do this.”

You make it sound easy.

BT: That momentum that Gabe's describing, that's what made it easy. It was plenty of hard work, but once it started, it just came together.

What was the turnaround like for the video? BT: We just did it fast, in the space of a few months.

GT: There is a process for how music videos get made. Directors pitch for them, they come up with their creative, present it and there’s a process to go through. This one was already happening before any of that process. It was pure art from Harry and Phoebe, going, “We're going to connect and make this amazing thing and it will come out when it comes out.” As a creative to work in that way is totally joyous. You're just facilitating greatness.

What was it like to shoot?

BT: This is also easy, in a way, because the choreography means that [Harry's] going to be here at this point and there at that [point]. You knew exactly where they were going to be in the room. We went back and forward a bit on how to weave the story into the choreography so it wasn't just a dance routine. By the time we got onto set, that was quite well planned. The nice thing is being more prepared, you can try to feed in a bit of latitude to things. I know because we've worked with Harry for a long time that the camera doesn't just love him. The camera wants to marry him and run off with him and probably never come back. So we know to give a little bit of space for that to happen. Obviously to have Phoebe there with him as well is totally bonkers. And, again, the camera loves her. It was exciting for us to talk about how to execute things with someone who we admire so much.

GT: When you go to the Troxy there's a hidden stage at the top. Ben had an idea of coming down from the hidden stage to reveal Harry, then setting a scene up of [Phoebe] at the top. She was brilliantly collaborative in discussing what kind of role she was going to play.

What notes did you talk through with Phoebe about her character? BT: This song's called "Treat People With Kindness”, so it feels like there's a distance to cover in the narrative. You start on the Marsellus Wallace shot, out of Pulp Fiction. We wanted to get a sense that this was a kind of tough guy and there was the opposite of people being treated with kindness around the place. But the conversation went from [Phoebe] being a character that stood up to him to, actually, if you look at it, [she] wipes a tear off of his eye, which is so beautiful.

GT: Ben was just obsessed with casting the back of people's heads for the first shot.

What makes a good back of the head?

BT: I'm talking about how many folds of skin at the top, the optimum shape. Someone [said] that Bruce Willis had a fantastic shaped dome of a head and it really turned me on to the shape of a bald head, because it can be really beautiful.

GT: I find a lot of the music videos that we do, there'll always be a shot from a film that inspires something.

Aside from breaking the fourth wall at the end, the Pulp Fiction shot and the Nicholas Brothers, what other reference points or Easter eggs did you include?

BT: We love the Marx Brothers, Danny Kaye and those physical comedians. I love Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire. We’re also obsessed by Bugsy Malone. Busby Berkeley... I don't think there was much Busby Berkeley in this. GT: At the end there's a tiny bit, but Busby Berkeley has actually been used as a reference in quite a few music videos. We love that stuff. But we didn't want to go too into that symmetry and the choreography, because it didn't feel as fresh. What have you learned from Harry, after working together for so long?

BT: He's on a really interesting journey and we are lucky to be a bit of that journey with him. It's really rewarding to dip into that and try to facilitate some of that as we go along. There's a lot that he's in touch with that I'm not. I'm quite a lot older than him. I'm not as cool as him.

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

Would y'all like some Supernatural Lore dropped on you that I assume was common knowledge at some point but which, as a new fan, I haven't really seen talked about? If so, settle in to learn about the origin of the phrase "The French Mistake", and some cinematic history on fourth-wall breaking that hits real differently in light of season 15.

We all know "The French Mistake" as the title of That One Episode where Supernatural goes so meta the real world becomes part of the show (also Misha Collins gets murdered?? I might as well confess now I haven't actually seen this episode, I'm still working my way through to it. Hopefully that doesn't become a problem...) Anyway, what you might not know is the title comes from the movie Blazing Saddles.

With some caveats, Blazing Saddles is an absolutely incredible movie: it's a comedy western made in 1974 about a Black man who becomes the sheriff of a racist town, defeats capitalism and gets a cute sharp-shooting boyfriend. The "boyfriend" part is subtext, but it's pretty damn loud.

So where does "The French Mistake" come in? It's the name of what might be the movie's most iconic scene. In the middle of the climax, a big western shoot-out turned brawl, the camera pans up out of the town and onto an adjacent movie set. The brawling cowboys burst through the wall of that set, out of their own film and onto the new set where they continue to fight. This is why the episode of Supernatural is named for this scene. Just like in Blazing Saddles, Sam and Dean stumble out of their fictional world and onto a film set.

Here's the part that takes this from good to GREAT: in Blazing Saddles, the set they burst onto is a musical, being filmed in the style of a Busby Berkeley number, and before our cowboys break through that fourth wall, we see a staircase lined with chorus boys. They are dancing suggestively, thrusting their hips and singing a song called The French Mistake.

Throw out your hands. Stick out your tush. Hands on your hips. Give them a push. You'll be surprised, you're doing the French mistake.

Look. Guys. It's a song about anal sex. It's being sung by a group of gay men. When the cowboys break the wall and stumble onto the set of the musical, one of them starts out fighting with one of the chorus boys and ends up walking off arm in arm with him. Two other chorus boys go for a romantic swim in a fountain.

"The French mistake" is a reference to the breaking of the fourth wall but it's also literally a euphemism for queer sex. Blazing Saddles makes breaking the fourth wall intrinsically tied to queerness breaking into the heterosexual narrative (I could write an entire essay on how that plays out in the relationship between the leads, Bart and Jim. Suffice to say they trade their horses for a limousine and drive off into the sunset together). Worth considering: are the metanarratives and fourth wall breaking on Supernatural also intrinsically tied to queerness manifesting in the narrative?

For a whole host of reasons, Mel Brooks thought Warner Bros would bury Blazing Saddles rather than release it. He told everyone working on it to just go wild and do all the things they wanted to do but never expected to get away with, because the chances were good it wouldn't matter. He had the right to the final cut - meaning that the execs couldn't force him to make any edits - but he didn't know if the film would ever see the light of day. It did, though, and ended up being a major hit. Brooks talked about this, and in particular the French Mistake scene, in an interview with Entertainment Weekly:

That was dangerous because I was asked by Warners — they said I can do everything you said, but they kept saying, “Don’t do the gay scene. Don’t break through the walls and do the gay scene. You’re crossing a line there.” I said, “Don’t be silly.” There’s always these musicals being shot at Warner Bros. with top hats and tails and dopiness, you know. I said, “It’s a good mixture of cowboys and gay chorus boys.��� So I kept it all in. I had final cut.

There's something kind of familiar about that, right? Don’t break through the walls and do the gay scene. Queerness and metanarratives bound together, threatening the status quo. This scene in Blazing Saddles was so threatening to Warner Bros that above everything else in a very boundary-pushing movie, this was the one they wanted to cut.

One more thing that hits different after season 15, from another really meta episode... Yeah, I'm referring to the famous "why lamp?" scene. Other people have already talked about how the way Dean's dancing sequence in The Hero's Journey recalls the Hays Code and deliberate queer-coding in classic Hollywood. But I want to go further and say that it also specifically recalls the scene I've been talking about, Blazing Saddles' 'The French Mistake' scene.

Maybe this is just because it's drawing on the same frame of reference, or maybe it's more deliberate, but either way, the parallels are there, down to the suggestive song playing (We're all alone, no chaperone... let's misbehave). It's really telling to me that this dance sequence so closely parallels a scene that was almost censored for being too gay.

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

How the joyous ‘Treat People With Kindness’ video came together

Directors Gabe and Ben Turner on how Fleabag became the launchpad for Harry Styles' ‘Treat People With Kindness’ music video

Like most good stories, Harry Styles’ video for “Treat People With Kindness” starts with Fleabag, specifically with a meeting at Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s hit London theatre run, which became the launchpad for the joyous black and white video, released on New Year’s Day.

Working with a team now synonymous with Styles' videos (choreographer Paul Roberts and stylist Harry Lambert, to name a few), it was directed by brothers Gabe and Ben Turner (part of the production company Fulwell 73), whose work has spanned One Direction videos ("Steal My Girl", “History”) and Styles' solo track “Golden” and who produced the documentaries I Am Bolt (2016) and Hitsville: The Making Of Motown (2019).

Here, Gabe and Ben tell us the story of when Harry met Phoebe and how “Treat People With Kindness” came together.

Gabe, you tweeted that the video was shot at the beginning of last year. How did it come together?

Gabe Turner: Harry and I went to watch Phoebe do her live Fleabag show in London. We met Phoebe and she was the kindest, most delightful person ever. The next day I was watching dance videos randomly and one of them was this Nicholas Brothers video from the 1920s. It was two brothers dancing. I said to Harry, “You and Phoebe, question mark.” And he messaged back saying, “Treat People With Kindness”. Then he called Phoebe and was like, “I've got this song. I want to do a video. What about me and you doing this dance routine?” And she was like, “Great." And then the two of them called Paul Roberts, the choreographer.

Ben Turner: This isn't always how our life is. This isn't the regular process. But once the touchpaper got lit, it just went off. Every now and then something comes along where all the dominoes fall perfectly.

GT: Harry and Phoebe worked with [choreographers] Paul Roberts and Jared Hageman. The four of them rehearsed all the time, remotely, wherever they were. Whatever projects they were doing, the choreographers would go with them and work on their steps. We would get sent video updates for them as they were rehearsing and learning. We were like, “This is amazing.” We had been to the Troxy for the Bugsy Malone Secret Cinema, so we were like, “That would be a great place to do this.”

You make it sound easy.

BT: That momentum that Gabe's describing, that's what made it easy. It was plenty of hard work, but once it started, it just came together.

What was the turnaround like for the video?

BT: We just did it fast, in the space of a few months.

GT: There is a process for how music videos get made. Directors pitch for them, they come up with their creative, present it and there’s a process to go through. This one was already happening before any of that process. It was pure art from Harry and Phoebe, going, “We're going to connect and make this amazing thing and it will come out when it comes out.” As a creative to work in that way is totally joyous. You're just facilitating greatness.

What was it like to shoot?

BT: This is also easy, in a way, because the choreography means that [Harry's] going to be here at this point and there at that [point]. You knew exactly where they were going to be in the room. We went back and forward a bit on how to weave the story into the choreography so it wasn't just a dance routine. By the time we got onto set, that was quite well planned. The nice thing is being more prepared, you can try to feed in a bit of latitude to things. I know because we've worked with Harry for a long time that the camera doesn't just love him. The camera wants to marry him and run off with him and probably never come back. So we know to give a little bit of space for that to happen. Obviously to have Phoebe there with him as well is totally bonkers. And, again, the camera loves her. It was exciting for us to talk about how to execute things with someone who we admire so much.

GT: When you go to the Troxy there's a hidden stage at the top. Ben had an idea of coming down from the hidden stage to reveal Harry, then setting a scene up of [Phoebe] at the top. She was brilliantly collaborative in discussing what kind of role she was going to play.

What notes did you talk through with Phoebe about her character?

BT: This song's called "Treat People With Kindness”, so it feels like there's a distance to cover in the narrative. You start on the Marsellus Wallace shot, out of Pulp Fiction. We wanted to get a sense that this was a kind of tough guy and there was the opposite of people being treated with kindness around the place. But the conversation went from [Phoebe] being a character that stood up to him to, actually, if you look at it, [she] wipes a tear off of his eye, which is so beautiful.

GT: Ben was just obsessed with casting the back of people's heads for the first shot.

What makes a good back of the head?

BT: I'm talking about how many folds of skin at the top, the optimum shape. Someone [said] that Bruce Willis had a fantastic shaped dome of a head and it really turned me on to the shape of a bald head, because it can be really beautiful.

GT: I find a lot of the music videos that we do, there'll always be a shot from a film that inspires something.

Aside from breaking the fourth wall at the end, the Pulp Fiction shot and the Nicholas Brothers, what other reference points or Easter eggs did you include?

BT: We love the Marx Brothers, Danny Kaye and those physical comedians. I love Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire. We’re also obsessed by Bugsy Malone. Busby Berkeley... I don't think there was much Busby Berkeley in this.

GT: At the end there's a tiny bit, but Busby Berkeley has actually been used as a reference in quite a few music videos. We love that stuff. But we didn't want to go too into that symmetry and the choreography, because it didn't feel as fresh

What have you learned from Harry, after working together for so long?

BT: He's on a really interesting journey and we are lucky to be a bit of that journey with him. It's really rewarding to dip into that and try to facilitate some of that as we go along. There's a lot that he's in touch with that I'm not. I'm quite a lot older than him. I'm not as cool as him.

(12 January 2021)

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ouija, Origin of Evil and the profane voice - Part I

Though extremely shocking and disturbing, children happen to be at the core of major horror films. Samara in The Ring (2002), Dalton in Insidious (2010), Dany and the Grady twins in The Shining (1980), the children in Sinister (2012), Thomas in The Orphanage (2007) are among many other examples that prove the existence of an entire branch of horror cinema built on the mythology of the malevolent child. Why is the figure of the child so prevalent? Why should the most innocent and purest human beings be the main characters of films that are gruesome, violent and whose public age is strictly restricted? Precisely because their vulnerability and purity of soul make them easily influenced and manipulated by external forces. Besides, children are known to have an overwhelming imagination and a propensity to trust which are necessary to open the boundaries between the worlds of the living and the dead in accordance with the codes of the genre.

In addition to this, the more the prey is opposite to our expectations and subverts our beliefs of what is proper and what is not, the more the fright and fascination are potent. To consider a child as a monster, a killer or a possessed body is beyond our general understanding, hence the uncanny appeal of creepy children.

As pointed out by Alison Nastasi in her article published online on Hopes&Fears, this devious appeal for corrupted and murderous children portrayed in horror films might echo to « real-world fears about parenting, gender and social responsibility. »; a theory supported by Joe Dante’s comments about the subject : « Could it be connected to the fact that more and more parents have difficulty balancing work responsibilities [and] child-rearing (not to speak of nurturing their own relationships, personal and career aspirations) and are squeezed financially by the costs of raising children […]? Therefore, is it any wonder that children in genre movies are portrayed as powerful, disruptive, and uncontrollable? Perhaps these menacing moppet movies reflect the fears inherent in helicopter parenting—that the minute you take your eyes off your child, something dreadful will happen. » In any case, the films in question use the creepy kid trope in order to suggest that something is wrong, that the natural order of things is being shattered.

The corruption of innocence can take many forms but the most interesting one to study in relation to the narrative role of the voice in cinema is the threat of an invasion from the Beyond. In Ouija: Origin of Evil (2016), supernatural forces hold a young girl hostage by inhabiting her body and making it go through such transformations (vocal and physical) as to change it beyond recognition.

Taking place in 1967 in Los Angeles, Ouija: Origin of Evil tells the story of the Danzer family. Alice, a spiritual medium, is striving to make ends meet after the loss of her husband and father of her two children by hosting readings in her own house with the help of her daughters, Lina (15) and Doris (9). Running a declining scam business, in which Alice pretends to talk to the dead to bring closure to people and the girls help her out with tricks intended to make it all real, Lina suggests her mother to add a ouija board as a new prop to modernise her readings. The factitious dimension of the ritual which unfolds through the display of ingenious devices (stretchable table, a cupboard big enough to hide Doris, extinguishable candles…) is both an ironical comment on how fake spiritism is going to beat the family at their own game by revealing its true power and also a cleverly designed introduction to set the tone and build the tension.

All the ingredients are here to turn the ouija experience into a nightmare. The bereaved family is craving for a contact whatsoever with their loved one, little Doris first. She wishes she could talk to her father at a seance like other people do when they come and see her mother for help, that is why she does not talk to god directly but instead send prayers to her dad every night before going to bed. Contrary to Lina who is a teenager in complete denial and pushes down her feelings, Alice and Doris seek communication and are open to it, hence the evil befalling on them.

Portrayed as an angelic but lonely and bullied girl who is deeply grieving her father and believes in the blurry frontiers between the worlds of the living and the dead, Doris becomes the perfect human and tangible vessel through which supernatural forces can express themselves. All starts with the introduction of the ouija board as a prop into the house and with Alice breaking the three rules which are to never play alone, in a graveyard and never forget to say goodbye. At this very moment, Doris becomes inhabited by Marcus’s spirit whose identity is yet to be defined. How does this possession first transpire? Through speaking. Marcus uses Doris’s voice to start materializing and, as soon as she touches the board, the voices appear all around her, thus enabling the world of the Beyond to let in.

Doris is progressively attracted by the ouija board which makes her believe she is talking to her father, Roger. They are deceitful spirits who do everything to earn her trust to better trap her, hence the hint at the money buried in the cellar. Contrary to Lina who is far from being fooled, Alice thinks her youngest child is gifted and asks her for help. As the readings follow one another, the trap is closing in around Doris who starts feeling pain in her neck at the same time she excels in the occult. She can now reproduce the voice of the deceased summoned during the seance.

Once she is fully possessed, Doris first goes through a radical physical and behavior transformation by becoming lethargic, stolid, her eyes often turned white when no one is watching her. Besides, her vocal abilities also go through creepy changes. In addition to mimic the deceased’s voice during the readings, adults’ voices, Doris keeps whispering in people’s ears in a demonic way when the evil entity starts spreading its malevolent influence on the whole family.

When the film reaches its climax and Doris fully assumes the devil’s voice, which is guttural, otherworldly and distorted by hatred, she no longer is a young innocent child. Marcus’s spirit corrupts and perverts Doris to achieve revenge by desecrating her body and soul and making her utter bloodcurdling things. The scene which most epitomizes the figure of the violated child is when Doris explains step by step to Lina’s boyfriend how it feels like to be strangled to death. The most uncomfortable thing about it is to witness the contrast between what she says and the sweet voice in which she says it with an angelic smile on her face. The mise-en-scène that keeps stressing Doris’s vocal changes, by shooting her facing the camera (or the fourth wall) as if she was already part of the Beyond, is meant to emphasize the element through which she is channelling these powers and forces : the mouth.

youtube

The mouth as an organic element stands as a kind of leitmotiv throughout the film inasmuch as the possession of Doris’s body and soul by the demonic entity is made complete through that means. One night, Doris is awakened by her pain in the neck and gets assaulted by a dark creature who thrusts his devilish arm into her throat. This shadowy creature, one can notice, has no mouth or rather a distorted sewed one, similar to Lina’s mouth when she looks at herself in the mirror one night. At the light of these elements, what was supposed to be a nightmare was in fact real and prophetic.

But what can be the meaning of the recurring imagery of the sealed mouth (see also Lina’s doll)? Who is Marcus? Why is he portrayed as an evil spirit? What does he want from Doris and her family? He clearly states his purpose when trying to possess Lina’s soul : to snatch her voice.

Father Tom Hogan, a friend of the family, is the one who uncovers the ugly truth behind Doris’s pretended benevolent gift of clairvoyance. She is not channelling good forces but Marcus’s spirit, a man who happened to have been mutilated and murdered in this house a few decades ago. After the second world war, a twisted nazi doctor, called the devil’s doctor in the camps, escaped to America where he succeeded to get hired in a mental institution. He went on practicing his sadistic experiments on patients in the basement of his house. In order to do it, he cut out their tongues, severed their vocal cords and sewed their mouths so that no one could hear them from above. However, Marcus’s story does not end with his death. Violently murdered, he never rested in peace but instead was doomed to wander in the cold darkness of the underworld among other desperate, voiceless souls and malevolent creatures who must have been summoned by the doctor who was into the occult.

In the end, Marcus, who has been silenced by force, deprived of his own voice and overtaken by the surrounding evil influence in the Beyond, seeks revenge against god and people who have the ability to express themselves, eaten away as he is by hatred, frustration and pain. The only way for him to exorcise the horrible things he has been through is to communicate and hurt others, but for that a voice and a body are needed, hence his attempts to snatch the family’s voices. That is the only way to be heard and to have an influence outside his doomed world. Helped by her father’s good spirit, Lina grabs needle and thread and silences her sister for ever, thus fighting hard against the entity who strives to engulf her.

Ouija, Origin of Evil, like many other horror films, uses the voice and its communicative powers as narrative tools to address issues and challenge notions such as grief, loss, family unity, parenting, revenge, alternative beliefs, suffering, innocence, corruption, violation and religion. Religion…such a crucial theme whose set of practices and beliefs makes it the most cherished subject of the genre. Any idea which emblematic film is yet to be analyzed in the perspective of the profane voice and corruption of innocence?

#ouija#ouija origin of evil#horror film#ouija board#mike flanagan#elizabeth Reaser#annalise basso#lulu wilson#henry thomas#devil#spiritism#occult#voice#profanation#lina#doris#mouth#creepy children#cinema#supernatural#whispers#religion#film analysis#child#innocence#revenge#grief#loss#soul#voiceless

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Detroit

Can robots feel? To empathize? To do? Despite years of research, scientists do not give clear answers. And where science is powerless, fiction comes to the fore. Last year, with the help of NieR: Automata, Taro Yoko tried to get to the truth. Now David cage, the author of the interactive thrillers Heavy Rain and Beyond: Two Souls, has decided to present his view on the problems of artificial intelligence. Well, guys, myltso? On the blade Near future. Technology has made another leap, and the achievements of Boston Dynamics are in the past: androids are already among us, their appearance and behavior are barely distinguishable from ordinary people. Indispensable helpers and cheap slaves in one person, the" children " of CyberLife have been performing the most thankless work for years, bearing the humiliation of the Almighty masters. But nothing lasts forever: suddenly, in Detroit, one after another, deviants begin to appear-machines that have gained self-awareness.

Detroit: Become Human

In a matter of months, humanity is on the verge of war with its greatest creation. Now, in the darkest hour, the fate of the world depends on the actions of ordinary robots, not people. Marcus, the old artist's Butler, is stranded on the street in an accident. Connor, a police officer, hunts for "broken" brothers and tries to find out the reason for their madness. Kara, the housekeeper, runs off with her owner's daughter when he raises his hand to his own child. Heroes are waiting for incredible adventures, and their paths will cross more than once. And who knows how their amazing story will end?

Light, camera, shame Video games have long been made with an eye on Hollywood. Game designers spy on the Directors ' techniques, more and more screensavers from year to year, and the traditional gameplay is regularly replaced with spectacular QTE. It seems as if developers want to" shoot " movies, rather than sculpt conveyor blockbusters. Only a few people have the courage to say this openly. Few people except David cage and his Studio Quantic Dream.

Detroit: Become Human

Unlike other famous teams, the French company has long ceased to disguise itself: since 2005, it has been exclusively engaged in interactive cinema, where there is no place for shootings with terrorists, boss fights, or other distracting nonsense from the narrative. Cage's logic is impeccable: the industry is already littered with shooters like Call of Duty, why not do something original? But to create such masterpieces, you need skill. Talent. And here's the problem: the Frenchman has nothing else but naked enthusiasm.

Omikron: the Nomad Soul, Fahrenheit, Heavy Rain, Beyond: Two Souls... Each of his opus is a story about how a good idea was ruined by a bad performance. Whatever the game, it's a beautiful dummy-fascinating at first, and then, closer to the final, falling apart. So it was hard to expect anything good from Detroit: Become Human (with its banal beginning). And all the same old cage I found something to surprise.

Detroit: Become Human

Double Detroit is an emphatically cinematic adventure that tells the fates of several characters at once. As before, the player is required to do relatively little: walk around locations, collect or view garbage, talk a lot, pass sophisticated QTE and survive. Yes, unlike many of the genre's peers, in Become Human (as in the ever-memorable Heavy Rain), the characters can die, and the plot will move on quietly — though, already in the direction of a bad ending. This is not a peaceful LucasArts quest.

Already from the introductory chapters, the new product is perceived as one big work on mistakes — as if all these years the authors studied reviews of their creations, threw out unsuccessful elements and kept working. The output turned out to be a kind of collection of "the best of". Check the boxes: a futuristic world a La Omikron (alas, without David Bowie), an intriguing Fahrenheit introduction with dozens of scenarios, investigative episodes, the death of the protagonists and elements of the heavy Rain interface, Hollywood actors just like in Beyond. Even the main menu resembles the beginning of the Nomad Soul — only instead of a low-poly model, a beautiful girl breaks the fourth wall. Try not to blush.

Detroit: Become Human

And it seems that everything is familiar, familiar, but there is nothing to swear at: from the point of view of game design, the game is made wisely. Even the usual genre flaws here, in the new context, do not look so scary and critical. Do robots speak in an unnatural, UN-human way? Logically, the same pieces of iron! Invisible walls prevent you from exploring locations? Of course, the program does not allow you to deviate from the set course! Bullets don't kill or even slow down characters during action scenes, and wounds heal too quickly? Cars, what to take from them.

However, these are rather pleasant things — the really impressive thing about Detroit: Become Human is something else. Here (unlike the series of some Telltale), the decisions made by the gamer during the "movie" really affect what is happening — very noticeably change the story. At first, the linear narrative branches out over time: unique mini-episodes are opened, even fleeting dialogues and individual chapters vary. And endings are determined not by the choice of a specific scene in the final, but by a number of not always obvious moments. How thoroughly did Connor study the crime scenes? Had Kara managed to escape from her master? And how?

Detroit_ Become Human_20180522213231

Conceptually, the mechanics are similar to the "butterfly effect" Until Dawn (or the earlier Blade Runner from Westwood): do something or say-prepare for the consequences, the authors will not allow the descent. Unless in the Supermassive Games horror movie there were much less variations of the development of events: in this regard, chamber horror is difficult to compete with the cyberpunk epic. Quantic Dream employees have done a lot of work, and they do not hesitate to demonstrate this by drawing giant diagrams at the end of each Chapter, similar to the intricate chronology of some Metal Gear Solid. A good way to mask loading screens!

In other words, in terms of gameplay, the new product really succeeded. Taking the best of their previous creations and borrowing a couple of other people's inventions, the authors finally fulfilled their promise: they released a real interactive movie. Hooray? Hooray. But unfortunately, Detroit is still David cage's "Need more emotion" game. With all the consequences.

Be a man Alas, in the five years since the premiere of Beyond, the head of Quantic Dream has not learned to write good scripts. Even with the help of new assistants and editors, all he managed to compose was at best a mediocre melodrama about racism, where the roles of oppressed Negroes were assigned to soulless androids. Vulgar metaphors and clumsy references to real historical events (up to the Nazi concentration camps!) attach.

Detroit: Become Human

Admittedly, it's very funny to watch such obvious and artless nonsense in 2018. There are no bright new ideas, unprecedented sci-Fi concepts, or unique views on AI problems. Instead — it is a continuous repetition of what has been studied with a lot of loud words, high-sounding platitudes and obligatory tears in artificial eyes. The characters are all drawn up according to the textbook of archetypes and communicate such Terry platitudes that at times the game borders on self-parody. Sometimes it even seems that Lieutenant Frank Drebin from the Naked gun is about to turn the corner and everything will fall into place. But that would be too subtle. Well, at least there was no nonsense in the spirit of Heavy Rain, that is, attempts to hit and turn what is happening upside down, somehow. Here everything fits into the fragile logic of a fabulous cyberpunk universe, where a robot service can be bought for a measly 899 dollars, and Canada is a futuristic Wonderland.

However, not everything is so sad. There are also good scenes in Detroit — and such that it's not even a shame to watch! They are concentrated mainly in the storyline of Connor (who has to play a buddy movie in the spirit of the series "Almost human"). There is humor, and "chemistry" between two dissimilar partners, and quite a sensible dialogue almost without stupid "snot", from which it is time to roll your eyes. Looking at the amazing adventures of an Android and a grumpy detective Anderson, you keep asking yourself: "why the hell are there two other protagonists in this game?»

1 note

·

View note

Photo

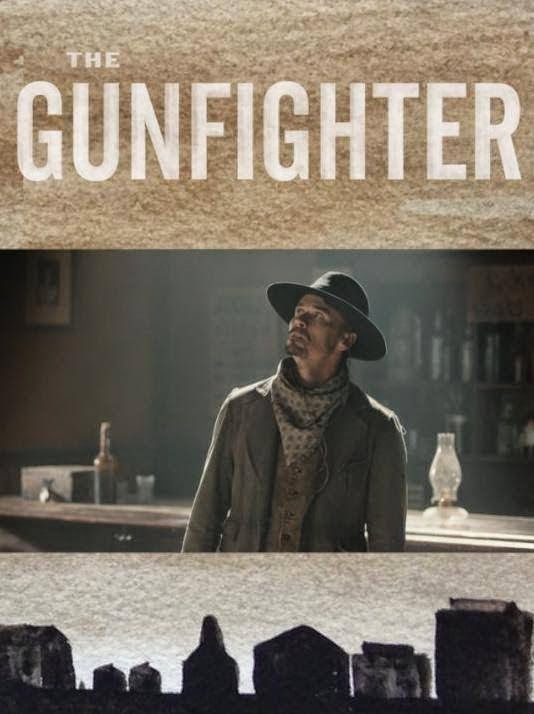

https://youtu.be/Z4qc34kYHdM The Gunfighter - Directed by Eric Kissack, 2014.

In this post, I will be analyzing a short film, The Gunfighter (2014) directed by Eric Kissack. I will address how the film utilizes cinematic elements to support its premise. I will discuss the premise of the film, basic dramatic structure, and production design. I will also explore the production style, which includes the cinematography, sound, and editing. Finally, I will discuss the production elements I will employ in my short film Inshallah, and it’s dramatic purpose.

After infidelity secrets of a small town were revealed by an unseen voice, a bloody gunfight ensued between a group of saloon goers and a strange gunfighter.

The basic dramatic structure though not unique, the director incorporated a voice with a decisive language mixing suspense and thriller with comedy. The setup - The Gunfighter (Kissack, 2014) is a narrative comedy western short about a gunfighter who enters a saloon to have a drink, and his actions are narrated by a voice. The unseen voice knows what all the characters are thinking, and begins to reveal their secrets. A gunfight eventually ensues as they all realized they have wronged each other and kill each other except one named Sally. The voice finally revealed that a rabid wolf would maul her the next day.

Production design in Gunfighter (2014) is a creative period western, set in a saloon as commonly used in westerns. The production utilized efficient camera composition and movements and sound to direct viewer attention, set decoration, wardrobe and props were used to enhance the plot of the film. The salon set features brown painted walls, bar set up with unlabeled and faded labeled bottles of alcohol, stairs that lead up to rented rooms, windows, batwing door, tables, and chairs. Complimentary set dressings like curtains, posters, pictures, whiskey bottles, old dirty lamps, towels, and napkins accessorized the set.

The casts were clad in a period western wardrobe that includes spurs cowboy boots, gun belt with holster, jacket, buckle-belt, scarves and cowboy hats. Props used were playing cards, shots of whiskey, handguns, and shotguns, napkins while the makeup made use of beauty makeup for the characters, the actors were made to look sweaty, dirty and greasy haired. Fake blood was also used.

The director utilized artificial lighting to direct viewers to the protagonist by setting a spotlight above him, other lights used were represented with daylight as the sole source of light because the film was set at a time that there was no electricity. Camera movements and compositions included dolly tracks, pans and tilts on sticks, slow zoom and rack focus, wide shots and long shots, over the shoulder shots, medium, close and extreme close-ups were all used to initiate viewer attention to details.

Diegetic and non-diegetic sounds were used. Background sounds, footsteps, dialogues, and inaudible conversations in, and outside the set is used to complement the things the audience cannot see from their point of view. This includes the use of Foley sounds to represent footsteps, bar conversation noise. A narrative voice that breaks the fourth wall, talking to the characters and viewers of the film. The use of ominous sound shows that things are about to turn ugly in the film. The sound effect was minimal and it was used to complement a fast pan movement from one character to the other. The Editing is creative and simple. Focusing on cutting back and forth between characters and complimenting the shots so as not to distract the audience.

The film is dialogue and narrative based. and the story is more visualized. In editing, the first scene was introduced with a fade in, and jump cuts were used in the rest of the movie to show the progression, and pace of the relationship between the two characters in a montage of events.

I will be working on a short titled Inshallah, written by Elijah Edmunds. The film is about a young Muslim American who is absorbed into a group home after losing his parents to a road accident. The future is bleak for Syed as he faces discrimination He is bullied by roommates and was rescued by a housemate who had been through what he is going through. Learning from the cinematic storytelling of the Gunfighter (Kissack, 2014) with a $25000 budget, and comparing the production elements to that of my zero-low resource film requirement, I will utilize the use of a group-home location with all the set requirements in place. I do not have enough funds to build a spacious bedroom, mess hall set, as required for fluid cinematographic movements in my film.

Cinematography style will consist of static slow zoom to emphasize the dialogue of some of the characters. Shaky hand-held camera close-ups will compliment the fight that took place in one of the bedrooms. I will use extreme close-ups to emphasize the unspoken emotions of the protagonist and also to highlight the physical appearance of his pain in the film. The tone of the film will be saturated and later warm, to show the growth of the protagonist towards the end because of its drama theme. It is a dialogue-based film, but music and sound effects will be used to complement the plot of the story.

The are several props needed for this film which includes Syed’s Quran, prayer beads, praying mat, case files, pork chops, cups, and plates, but the most important prop needed is the praying mat and Quran as this helps portray Syed’s religion and he observes Salat in his dorm room. The challenges I face in working on this movie is how to choreograph the fight scene between the characters. With zero to low budget, it is hard to high a choreographer so I hope to have the cast rehearse this scene many times before the shoot. I will shoot a well-rehearsed fight scene with the use of sound effects to compliment it.

Pre-Production has improved my knowledge a great deal about film production. And the preparation required towards it. Getting familiar with the scripts and working on a script breakdown exposes all hidden components of the film.

In conclusion, I analyzed a short film, The Gunfighter (2014) directed by Eric Kissack. I address the film cinematic elements and production style. I also discussed the production elements I will employ for the short Inshallah, which I will be working on next month, and it’s dramatic purpose. Finally, I had a self-reflection of the past month and my growth process in this class.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Production Journal - The Farewell

060320

As a creative of British Asian origin, I am attentive of the perceptions of the Eastern community within Western mainstream culture. Crazy Rich Asians (2018) was an uplifting rom com that limited Caucasian actors to background fodder and reserved leading roles for those of Asian descent. Although glossy in its approach, it was a landmark victory for ethnic minorities in the film industry who have long been typecast to portray dated stereotypes. It suggested that we could be charismatic, comedic and above all desirable. Awkwafina is a rapper, comedian and writer who has successfully transitioned to acting. Her character Goh Peik Lin is a bleached blonde version of her gregarious stage personae. In The Farewell (2019) she plays another feasible derivative of herself as aspiring writer Billi Wang.

There was no shortage of story beats in the film that resonated with my own narrative. As well as a protagonist played by an actor with a similar background, the writer and director Lulu Wang is a Chinese American eager to accurately depict her upbringing. In the opening scene Wang walks the streets of New York while speaking to her grandmother on the phone. She confidently exclaims that she is wearing a hat for the cold weather, even though she is not. In response, her grandmother says she is at home when she is actually at the hospital for an appointment. ‘The back-and-forth makes for an elegant volley of disinformation; if love is kinetic, it’s best to keep things moving,’ wrote Chris Gayomali in his review of the film. It sets up the dynamics of the plot that eb and flow between familial ties with cultural expectations. In Chinese traditional it is regarded as moral to withhold the severity of a medical diagnosis from an elderly relative, even if the outcome is certain death. This clashes with the sentimentality of American born Wang as she struggles with the situation. In an emotive exchange, her mother asks her to conceal her feelings when she blurts, ‘Chinese people have a saying - when people get cancer, they die. But it’s not the cancer that kills them, it’s the fear.’ (Gayomali, 2019) (Ide, 2019)

Anna Franquesa Solano (Born 1984) is the cinematographer responsible for The Farewell’s (2019) sensitive visuals. After graduating with a degree in Art History from the Universitat de Barcelona, she later studied film in New York. Her other noteworthy projects include I Don’t Like Cinnamon (2009), Silent Notes (2020) and The Normal People (2020). To breech the fourth wall, the characters walk directly into shot in slow motion during select scenes. While centred in the frame they stare at the audience as if in a dreamlike trance. This picturesque device references the Asian understanding of the passage of time. Buddhist thought encourages its practitioners to bring attention to the present moment and cast aside a preoccupation with the past and future. Furthermore, Solano pays close attention to filling her frame with long, timely shots. In a heartwarming scene, Wang and her grandmother practise Tai Chi together. The differences between the characters are shown to be generational as well as cultural. Nineteen takes were attempted and it was nearly left on the cutting room floor. My interest in the footage is its semi-autobiographical nature with two actors playing versions of themselves. Although there is a degree of scripting, the director captures genuine emotion by allowing any candid spontaneity to play out. As a result, it is equal parts documentary and constructed. (Weber, 2020)

Summary

There are certainly media codes that I will recreate from The Farewell (2019) and I am hopeful to represent its semi-autobiographical aspects - setting up a situation and then letting it resolve on film appeals to me. My interview is not purely documentary because I need to extract enough footage for the project and make it appear real. My email conversation with Teemu Hupli also covered some of the spiritual themes in this blog post.

‘In another tutorial I mentioned that there have been arguments that the Western conception of time has tended to be that time is linear - that it moves in one direction from past to present to future - and this is essentially what Hollywood conventions of continuity are designed to represent illusionistically. You can find this kind of conception particularly strongly in the philosophy of Hegel, who saw history as a progressive movement towards an ultimate goal of what he calls ‘spirit’ gaining freedom (you can try to read more about this by researching Hegel’s Philosophy of History, but it is heavy going reading, and I would perhaps suggest not spending too much time on it right now). More importantly, however, it was therefore interesting that your work seemed to derive inspiration from Japanese filmmaking. It has been suggested that the Japanese, or more broadly, Oriental conceptions of time are less linear than the Western notion, and therefore it stands to reason that some films originating from those areas construct different ‘pictures' of time too. This would be quite a fitting connection if your project ends up playing with questions of what is ‘genuine' thinking and talking in the here and now of ‘natural time’ so to speak; what is rehearsed, memorised and edited acting of such thinking and talking; what is continuous shooting and what is not, etc.’

Production Notes

The cyclical nature of Eastern philosophy was not investigated in the final cut of my piece. The voice over covers events that are not necessarily linear; however, there is a progressive property to the clips that expresses a beginning, middle and end. This is sealed with Natalie giving advice to her audience before switching a television off at the end. In post-production, I made attempts to shuffle the order of events but my experience as a filmmaker made this edit confused and unconvincing. The dream sequences from The Farewell (2019) were appealing too but I was not proficient enough with my knowledge of camera techniques to present my version of this storytelling device.

In several of the scenes of my film, Natalie and I are playing versions of ourselves in a similar fashion to Awkwafina’s portrayal of Wang. To film the section where we meet at the front door, I placed the camera in the kitchen and shot through the doorway. I was satisfied with this frame within a frame and then I left the flat to re-enter on cue. The events that occur on screen were not planned or scripted, and on some level, are representative of our real life interactions as friends. Following this, I found another shot in the living room that enabled us to speak to each other and remain seated on sofas. During an early screening of the project, I was given feedback that the burnt out window was distracting. I was not able to reshoot the scene and I feel that the way that it compartmentalises the composition is appropriate - I am respectful of her space as a performer that she may need to express herself. The chatting and laughing between us are spontaneous acts. She is actually showing me the Shakespeare script that we discussed beforehand and the enthusiasm is sincere. In the final cut, the voice over of her talking about improvisation seemed appropriately matched to this moment.

My initial proposal foresaw outside scenes shot on location - Natalie walking, on public transport and crowds. These were never produced due to time restrictions. As a result, the film comes across as more stagnant by being restricted to the confines of her flat. The scenes above contribute some spark to the footage and it would have been interesting to see how she engaged with strangers, other friends and family.

Bibliography

Ide, W. (2019). The Farewell Review - Beautifully Bittersweet Chinese-American Family Drama. The Guardian. Available from www.theguardian.com/film/2019/sep/21/the-farewell-review-lulu-wang-awkwafina [Accessed 10/04/2020]

Gayomali, C. (2019). How The Farewell Director Lulu Wang Stayed True to Herself. GQ. Available from www.gq.com/story/lulu-wang-the-farewell-interview [Accessed 10/04/2020]

Weber, J. (2020). The Farewell - 10 Things We Learned from The Director's Commentary. Screen Rant. Available from www.screenrant.com/the-farewell-things-facts-trivia-learned-directors-commentary [Accessed 10/04/2020]

Final Cut, Manual Mode, 25 fps, WB Natural Light

0 notes

Photo

FOURTH SHOOT: THE FIRST GREENHOUSE SCENE

So, now that we had completed the first scene with August, that being the Cafe scene I had posted about in my last blog entry, it was time to either film the first scene, or the first scene involving the Glasshouse since August is limited by her schedule in terms of filming for the time being. Due to my house being somewhat busy during this past week I decided upon the first Glasshouse scene as being a perfect fit for the next shoot.

The first Glasshouse scene in the films narrative occurs right after the first scene and the discovery of Mark’s main inspiration for his own art, setting up the important question of the film that is being asked by both Ken the cameraman as well as the audience, which is, is what we are being shown real or fake? throughout the Glasshouse scene we are given a glimpse into Marks character, someone who is fond of the idea of isolation and the rural side of life, with his choice of location being not only a brilliant place to shoot a abandoned body that has seemingly been murdered in Marks photographic narrative, but also as a place in which he himself expresses the idea of hiding, whether that be himself or other ‘things’. As well as this the scene hangs on the idea of Ken as the cameraman trying to understand Mark more as a person and his project, with his own questioning of Marks photography being that of fiction or reality. As Mark reluctantly opens up to Ken about his work and his intentions for the project, he becomes frustrated with Kens constant questions and momentarily snaps at Ken for pestering him to much. This gives us as the audience the first glimpse of Marks unhinged nature and who he truly is underneath this pretentious and charismatic vail. A man who is obsessed with creating the perfect artistic piece, who will do whatever it takes to achieve that, and at this point, in his own twisted mind, that is the execution of murder, however in order to achieve such a feet he will even lie to his own cameraman in order to achieve it, however in a moment of rage we almost see his true intentions come out as he snaps at Ken, for trying to find out the truth behind what he is up to. However, Mark seemingly manipulates the situation by proposing to Ken that if he was to help him complete this project, his involvement would grant him a vast amount of opportunities for the future, but for that to happen he needs to trust Mark and what he is planning, this seemingly sends Ken off the trail, who is now blinded by the idea of the success he could achieve. although this does not stop Ken for asking questions in the future, it restrains him from delving in to deep or trying to intervene in Marks intentions until halfway through the film. this scene is probably one of the most important ones throughout the narrative as not only does it give us a sneak preview of who Mark truly is, but it also sets in stone the main location of the films story as well as explaining why Ken is eager to do what Mark says and keep filming, until Mark finally reveals his true colours.

In order for the scene to feel important then, Me and Tom had to nail down the acting between these two characters throughout the filming. once we both met up at Stanmer Park we started right away planning out how this scene would go, going through the script and adding notes on how to say some of the sections of the lines as well as what emotions we had to portray in order to put forth the strength and weight of each of the dialogues. Although i didn't have as much lines as Tom it was important for me to play Ken in this scene as someone who is simply investigating into what his employer had in store for him as well as what his importance was in this project, although Ken is rather concerned in the beginning as he still doesn't understand if the photos of the dead models he was shown were real or fake, this subsides into simple and innocent questioning once Mark reassures him that the photos are only staged. On Tom’s side of acting he had to portray Mark as someone who starts off in the scene as a artist excited for his project finally starting now that he has a cameraman filming for behind the scenes. however his tone seemingly changes throughout as he becomes uncomfortable with all of Kens questioning, lashing out like previously mentioned, then luring Ken back in with his charm and lucrative promises. And in all honesty I think Tom really nailed it, after a couple of takes he was able to understand what i wanted to showcase in his motivation as Mark, he was really able to put forth the idea of Mark showing off to his new employee throughout the first half of the scene leading up to the glasshouse, then being able to quickly switch into a man on the brink of snapping once he had enough of all my questioning, and then proceed to slip back under the charismatic vail in order to lure my character back into the idea of future glory if i was to trust him and his vision, plus Tom’s use of the Wall outside the Glasshouse ruins as a depiction of the famous gallery wall that Kens name could be on in the future was all Tom’s idea, not my direction which was amazing! Looking back on the shoot however there are a couple of lines in which i seemingly stumble my words in multiple takes that we had to redo, although I am somewhat naffed off with myself in terms of that, i am still only in the early stages of acting with a camera, so i can excuse myself for that for the time being, plus also it adds to the nerves that Ken would be feeling in this scene.

Overall, I think me and Tom have nailed this scene completely, the Tone is set right in terms of the different shifts that occur throughout the characters interactions with each other, there is a certain comedic element that i do enjoy between the two that adds to the black comedy vibe i’m looking to nail alongside the main thriller aspect of the film, as well as the camerawork looking excellent for the direct cinema approach i’m going for and the fact we had it all wrapped up in 4 hours instead of the original 6 that we thought it might take. Perfect! Now all theres left to do is either the first scene or all the Greenhouse scenes involving August before we make our way to the final two scenes of the piece.

0 notes

Text

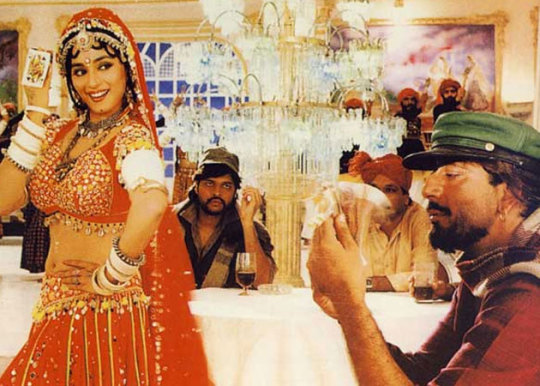

“Choli Ke Peeche Kya Hai?”: Bollywood's Scandalous Question, and The Hardest-Working Scene in Movies by Genevieve Valentine

In a nightclub with the mood lighting of a surgical theater, a village belle is crying out for a husband. Her friend Champa encourages and chastises her by turns; her male audience is invited to be the bells on her anklets. (She promises, with a flare of derision, that serving her will make him a king.) Her costume, the color of a three-alarm fire, sparkles as she holds center screen. The song and camerawork builds to a frenzy as if unable to contain her energy; the dance floor’s nearly chaos by the time she ducks out—she alone has been holding the last eight minutes together. And the hardened criminal in the audience follows, determined not to let her get away.

Subhash Ghai’s 1993 blockbuster Khalnayak is a “masala film,” mingling genre elements with Shakespearean glee and a healthy sense of the surreal. By turns it’s a crime story, a separated-in-youth drama, a Gothic romance with a troubled antihero, a family tragedy, a Western with a good sheriff fighting for the rule of law, and a melodrama in which every revelation’s accompanied by thunder and several close-ups in quick succession. (There’s also a bumbling police officer, in case you felt something was lacking.) It was a box-office smash. But the reason it’s a legend is “Choli Ke Peeche Kya Hai?”—“What's Behind That Blouse?”— an iconic number that’s one of the hardest-working scenes in cinema.

youtube

See, Ganga (Madhuri Dixit) isn’t really a dancer for hire. She’s a cop gone undercover to snag criminal mastermind Ballu (Sanjay Dutt), who’s recently escaped from prison and humiliated her boyfriend, policeman Ram (Jackie Shroff). Ballu, undercover to avoid detection, is trying to avoid trouble on the way to Singapore...but of course, everything changes after Ganga.

Though the scene shows its age—the self-conscious black-bar blocking, the less-than-precise background dancers—it’s an impressive achievement. Firstly, it’s a starmaker: the screen presence of Madhuri Dixit seems hard to overstate. By 1993 she was already a marquee name, and she would dominate Bollywood box office for a decade after, both as a vivid actress and as a dancer whose quality of movement was without peer. But if you’d never seen a frame of Bollywood you’d still recognize her mountain-climb in this number—playing the cop who disdains Ballu playing the dancer trying to court him, performing by turns for the room and to the camera, conveying flirty sexuality without tipping into self-parody, and all on the move for kinetic camera shots ten to fifteen seconds at a time. Dixit’s effortless magnetism holds it fast; the camera loves what it loves.

But this is more than just a career-making dance break; “Choli Ke Peeche” is the film’s cinematic and thematic centerpiece. Khalnayak is about performativeness. Ballu performs villainy (sometimes literally) in the hopes it will fulfill him; Ram vocally asserts the role of virtuous cop to define himself against those he prosecutes. As Ballu performs good deeds—saving a village from thugs, ditching his bad-guy cape for sublimely 1993 blazers—his conscience grows back by degrees. As Ganga performs a moral compass for Ballu, her heart begins to soften. And at intervals, crowds deliver praise or censure, reminding us that all the world’s a stage. (It’s in the smallest details: While on the run, Ballu’s ready to kill a constable until it turns out he’s an extra in the movie shooting down the street.)

And nowhere in cinema is the fourth wall more permeable than a musical number. Bollywood’s turned them into an art. Playback singers are well-known (they even have their own awards categories), a layer of meta in every performance. Diegetic dance numbers are common. Movies often halt the action entirely for an item number, as a guest actress drops by. For the length of a song, the suspension of disbelief the rest of a movie requires is on pause.

Musical numbers are a place where a movie can comment on itself, and Khalnayak takes full advantage of the remove. (In an earlier number with more traditional Hollywood framing, Dixit winks at us while singing to her beloved.) Likewise, Saroj Khan’s choreography in “Choli Ke Peeche” invites us to enjoy Ganga’s sexuality without concern about racy lyrics—or even about the villain, who dances in his chair along with the rest of us. With the camera as chaperone, it’s safe for “Ganga” to asks what else she’s meant to do but lift her skirts a bit as she walks (that skirt's expensive!), and to let her prince know she sleeps with the door open. The men around her are either part of the act, or an audience safely contained by the narrative and the frame for our benefit. (At times, her back is to her audience so she can dance for the camera; Khalnayak knows we’re watching.) “Choli Ke Peeche” is a thesis statement on the relationship between performance and audience.

It’s a moment powerful enough to cast a shadow across the rest of the film. This number, not the crimes or the cops, is what the movie returns to repeatedly; it’s too good to ignore and too subversive to solve. Not least, among the other layers of performance, is queer subtext. In Impossible Desires: Queer Diasporas and South Asian Public Cultures, Gayatri Gopinath points out that “female homoerotic desire between Dixit and [Neena] Gupta is routed and made intelligible through a triangulated relation to the male hero.” Champa’s masculinized within the performance; she asks the loaded title question, addresses our heroine’s male savior, and discusses him with Ganga. It’s a significant connection between women in a song supposedly directed at a man—which might be why Champa is the one who defends Ganga’s reputation by explaining the dance-hall sting, and reminding the audience it was all for show.

But that’s not going to stop “Choli Ke Peeche.” At the end of the second act, Ballu blows Ganga’s cover. (He’s known she’s a cop since their backstage meeting—another layer of performance). To prove they mean no real harm, the men don lenghas and veils and parody a chunk of the number, right down to interjectional close-ups and a wandering camera that brings kinetic energy to the static space.

youtube

In one way this reprise tries to undercut the song’s power by making it faintly ridiculous, suggesting it isn’t really sexual—it’s camp. But if “Choli Ke Peeche” functioned as a ‘safe’ way for Ganga to express sexuality when we first saw it, it serves a parallel purpose here. Despite the mocking undertones, with this number the men are reassuring her; they understand her sexuality was itself just a performance—her purity is therefore safe with them. (We know that’s a concern here because her shawl is pulled close about her; the free-spirit act is over, and her virtue is at stake.)

But there’s also something undeniably subversive in hyper-masculine, violent figures reenacting coy expressions of feminine desire. To prevent things from getting too subversive, Ballu invades Ganga’s personal space, a reminder of his power amid the making fun. And the performance ends in the threat of violence against Ganga when she breaks the spell—the expected order of captor and captive reestablishing itself as the film falls into a formulaic last act, an attempt to wrest social order out of the exuberant chaos one musical number has wrought.

It caused some chaos offscreen, too. When the soundtrack was released ahead of the film, “Choli Ke Peeche” was deemed obscene; the song was banned on Doordarshan and All India Radio, and faced legal challenge at the Central Board of Film Certification. In “What is Behind Film Censorship? The Kahlnayak debates,” Monika Mehta writes that “the visual and verbal representation combined to produce female sexual desire. It was the articulation of this desire that was the problem—it posited that women were not only sexual objects, but also sexual subjects.” And within the number, there’s no doubt Ganga’s in control; she sends alluring glances Ballu’s way, mocks (then takes) his money, and signals he’s free to follow her if he dares. The undercover-cop framework gives these gestures the veneer of respectability, but since Ballu doesn’t know that yet, the frisson of the forbidden remains.

Letters of condemnation and support rolled in. Many claimed the song was too suggestive; an exhibitor from Paras Cinema in Rajasthan wrote in favor because “Choli Ke Peeche” was based on a folk song from the area, and “If it was vulgar then the ladies would have never liked it.” The examining committee eventually ruled in favor of letting the number remain, with some edits: one that removed the chorus entirely (which Ghai successfully appealed), and two cuts to beats considered provocative, including one of Ganga ‘pointing at her breast’ as she sings, “I can’t bear being an ascetic, so what should I do?”, unequivocally claiming sexuality without even a man as her object. No wonder it had to go.

It wasn’t the only controversy dogging the film; star Sanjay Dutt was arrested under The Terrorist and Disruptive Activities Act for possible connections to the 1993 Bombay bombings, which added an uncomfortable self-awareness to Ballu’s onscreen misdeeds. Yet those controversies did Khalnayak no harm at the box office, where it broke records, and the movie’s had such nostalgic power that as of 2016, Ghai was considering a sequel.

But “Choli Ke Peeche” remains the movie’s most measurable influence. In Bombay Before Bollywood: Film City Fantasies, Rosie Thomas notes that after Ganga, “distinctions between heroine and vamp began to crumble, as the item number became de rigueur for female stars,” suggesting Khalnayak was a harbinger of less rigid strictures for Bollywood’s leading ladies. Another legacy of Khalnayak: more numbers feature women—with a man as the absent locus of their affections—dancing with each other instead, forming their own narrative connections and opening the opportunity for queer readings. (One of the most famous, “Dola Re Dola” from 2002’s Devdas, features Dixit again, alongside costar Aishwarya Rai.)

The pressure of so much cultural influence and metatextual weight might have turned a lesser scene into a relic, a stuttery car chase from a silent movie that starts a montage of the ways the camera has developed. It’s a testament to “Choli Ke Peeche” that it absorbs the weight of the years as gracefully as it does. If you want a watershed moment for sexual agency in Bollywood, you have it. If you want a starmaker with dancing that’s influenced choreography and direction for twenty years since, it’s happy to help. If you want a scene that dissects the idea of performance as subversive act, the offscreen vulgarity scandal only adds to your case. And if you want a musical number that reminds you what cinema can do, “Choli Ke Peeche” is as vibrant, campy, and complex as ever.

#bollywood#choli ke peeche#khalnayak#sanjay dutt#subhash ghai#masala film#all india radio#oscilloscope laboratories#musings#indian cinema#cinema of india#ganga#devdas#aishwarya rai#madhuri dixit#doordashan

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

NOTE: Despite the fact The Magic Flute was originally released on Swedish television on January 1, 1975, it debuted as a theatrical film in the United States later that year in November. As per the rules I set out for this blog, Bergman’s The Magic Flute will be treated as a theatrical film.

The Magic Flute (1975, Sweden)

I imagine that when some people read that this film review concerns an adaptation of an opera, they will stop reading at the word, “opera”. As someone who was taught classical music from an early age, I get it. Opera seems inaccessible, and a several-minute aria just to get a plot point across can seem daunting (not just for the audience, but the performer too). But as with any artistic medium, there will always be points of entry for newcomers. Ingmar Bergman’s 1975 adaptation of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute is one of them. The Magic Flute is one of the more accessible and most performed operas in Western classical music, and it just so happened to be Ingmar Bergman’s favorite. Bergman saw the opera when he was twelve years old, leaving an immediate impression. Unable to afford the record, he attempted to recreate The Magic Flute with marionettes at home. By the mid-1970s and having cinematic and stage production experience in his oeuvre, Bergman dared to imagine filming his favorite opera.

There are numerous cinematic opera adaptations. But they are underseen and largely unavailable to North American viewers – I am not including filmed opera performances in this distinction (e.g. the Metropolitan Opera’s popular live feeds that are presented in movie theaters and public television). Invariably, Bergman’s The Magic Flute is mentioned on the rare occasions when opera films are discussed. Sometimes, due to contempt for opera or a lack of understanding about classical music, it is the only such opera film discussed, and usually never from a musical lens.

In this adaptation, Bergman attempts to meld the distinct artifices of cinema and opera together. The viewer is never transported to a fantastical world, as the film possesses no “fourth wall” to begin with. We see an audience – look closely and you will see Bergman and cinematographer Sven Nykvist in the audience – waiting in anticipation during the overture, and the action takes place on what appears to be a homely community opera house. On occasion, we will see the performers backstage preparing for their musical entrances. When their performance begins, they inhabit the world of the opera.

This peculiar dynamic Bergman creates is less believable on a more gargantuan stage. The stage’s production design and deliberately low-budget (but charming) costume design suggests we are experiencing a performance given by a small community opera company. La Scala this is not, nor is it the Met or Paris Opera. Bergman wished to shoot the film at the Drottningholm Palace Theatre in Stockholm, a small eighteenth-century theater that still uses mechanisms dating back to its inception. Unfortunately, that theater was deemed too fragile for film equipment. Nevertheless, Bergman and production designer Henny Noremark (who also served as co-costume designer along with Karin Erskine) concocted a workaround. On a soundstage at the Swedish Film Institute, the production design team painstakingly crafted a facsimile of the Drottningholm Palace Theatre’s interior. The Magic Flute appears to be an inexpensive production, but it is anything but. The stage is intimate, inviting, personable.

In brief, Mozart’s opera is set in Egypt and concerns a mother-daughter dispute rife with misunderstanding. The protagonist, Prince Tamino (Josef Köstlinger), is contacted by the Queen of the Night (Birgit Nordin). She asks him to free her daughter Pamina (Irma Urrila) from the clutches of a high priest named Sarastro (Ulrik Cold; doesn’t that sound like a villainous name?). After being shown a portrait of Pamina, Tamino falls instantly in love with her – that’s opera logic, you know. Tamino is joined in his adventures by Papageno (Håkan Hagegård), an overly talkative bird-catcher dressed like a bird. But Tamino will learn more about Sarastro’s priestly order and becomes interested in joining. The Magic Flute has been interpreted as heavily influenced by Masonic themes, and modern analyses clash as to whether its portrayal of the Queen of the Night is misogynistic (see: Sarastro’s belief that Pamina should not be subject to the Queen’s feminine manipulations) or proto-feminist.

Also featured are the conniving Monostatos (Ragnar Ulfung) and, in the second act, Papagena (Elisabeth Erikson). The Magic Flute benefits from an excellent recording by the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra under the direction of conductor Eric Ericson.

Opera films tend to adhere closely to the work composer and librettist. Bergman exercises some liberties with Mozart’s music and Emanuel Schikaneder’s libretto*. Instead of the original German, this film uses a Swedish-language libretto by the poet Alf Henrikson (this Swedish-language version debuted at the Royal Swedish Opera in 1968). No offense against the Swedish language, but this Swedish-language version of The Magic Flute makes the musical phrasing awkward. Mozart’s opera was composed with German in mind. German may not be a listenable as Italian in an operatic setting (it could be worse, it could be English – as in the otherwise excellent 1951′s The Tales of Hoffman, adapted from Jacques Offenbach’s opera of the same name), but this should have been Bergman’s first choice.