#(And how extremely wrong that can go because of the weight of institutions and ideologies and history itself on everyone and everything)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Midst is about a murder the exact same way that Disco Elysium and Pentiment are about a murder.

#They're about murder but also about ideology and authority systems and maybe trying to do what's right when there's little space to.#(And how extremely wrong that can go because of the weight of institutions and ideologies and history itself on everyone and everything)#It's about what you're told and who is telling you. About change and potential second chances.#About communities and societies and how we build them (for better and for worse) and what it is we owe and give and take from one another.#About realizing you can feel the world turning right here and right now. About change and its conditions.#Midst things#Midst#Midst podcast#Disco Elysium#Pentiment#Midst Cosmos

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I'm disabled yeah? I've talked about it a lot. You know it if you're following me.

Something I don't really talk about (on here anyway) is the complicated relationship that one can have with their family members if they are disabled and are in need of relying on family. It can be extremely easy to feel like you're a burden on your family, especially if you need them for any kind of care, whether it be physical care (feeding, bathing, medication management, etc), or financial care (transportation, living arrangements, income, etc). All relationships are work, yes even the fun ones, and it can make you feel bad if you personally feel as though you are unable to contribute as much to the relationship as the opposite party. When you're disabled, you find that you have to quantify your share much differently. Sometimes the reality is that you are not able to contribute the same as the other person, but that doesn't mean that what you are contributing isn't your version of a lot.

However, sometimes family or loved ones will make comments, be it out of frustration or because they don't realize how they sound, and you as the disabled person are left feeling as though you are a weight upon them. That, perhaps, what they aren't saying is how easy it would be if you weren't there. Unfortunately, we live in a world where it is much easier to be able-bodied because our world is so violently against our existence. It can be easy then to spiral into a pit because you're faced with a truth wrapped in an insecurity that is fueled with things that are said or unsaid, looks, and body language.

Here is the reality that I had a therapist help me with:

Yes, it can be hard to take care of someone who is disabled. It can be hard to care for anyone though, regardless of disability or lack thereof. Sometimes, we get tired, we get frustrated, and we take that frustration out on those we are closest to because they are the most likely to forgive us or let it go.

The hardships that a disabled person faces, both externally and internally, are very different from those that an able-bodied person faces. When discussing the challenges that an able-bodied person deals with, it is not possible to compare them to those of what a disabled person deals with. They are like comparing apples to oranges; they are both challenges but they cannot nor will ever be the same.

Those who have chosen to care for you, a disabled person, are doing it of their own free will. They decide every single day that they will keep doing it. They are not forced to, they do it because they care about you. There are lots of people who choose not to care for their disabled family members - this is why there are programs such as disabled housing that exist in some states so that people who do care can help.

You are not a burden any more than any other human being is a burden. You are worthy of care and love simply because you exist. There is nothing wrong with needing help. Everyone needs help, regardless of their circumstances or their health. There is nothing wrong with requiring more than someone else and there is nothing better about requiring less than someone else.

Finding ways to have conversations about this side of disability and relationships is very important. It starts with understanding the points I've made above and ends with having frank discussions with your loved ones. When someone who cares for you comments about how difficult "this all is", it is natural for our knee-jerk reaction to be angry or hurt. It stirs up this pain that we feel on a daily basis because the world is so hostile to our existence and we are supposed to feel safe at home. You feel attacked in the same way that you get attacked by strangers, by institutions, by ideologies. For a moment, the people who are supposed to be those you're allowed to lean on for help sound just like those who would gladly see you gone. This is why it is so very important to be able to find a way to say exactly this to your loved one. Opening up this conversation, asking them to clarify how they express their frustration, helping them see how they are causing a rift when it could be an opportunity to commiserate all helps craft a stronger foundation.

Sometimes, circumstances force us into a situation that isn't our ideal. I do not know of a single disabled person who enjoys being forced to lean on loved ones out of necessity. All of us would much rather have the choice as opposed to having the choice taken away. We have to adapt, it is the only way through. Part of that means making these relationships work to the best of our ability so that when things get hard, as they often do, we know that the bond isn't something we need to question when pushing through the difficult things.

#disability advocacy#as always tho finding a good therapist to vent to and learn how to sift through all this is key#its hard being disabled#you do need help working through it all

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Things Parents Should NEVER Say If They Want to Raise Empowered Daughers.

Remember that words have the power to wound, irreparably. What parents say matters, so be careful what you say if you want to raise confident daughters. Growing up in Indian households comes with its own issues. Growing up as a girl in Indian households is another matter altogether. Even today, there are some statements that have become so hideously commonplace in Indian families, that our elders either do not, or cannot understand the enormous impact these statements have on the psyche of young girls and children in general. Here are 4 examples of seemingly innocuous statements that are thrown at girls in Indian households, without a thought and understanding, which need to be banned immediately. “Behave like a girl. Don’t talk back!” Behave like a girl. Don’t talk back! (Ladkiyon jaise raho. Ulta jawab mat do / zabaan mat ladao) What does this even mean – to behave like a girl? How do we define what ‘behaving like a girl’ entails? Is it to be submissive? Comformative? Meek? Feminine? This reeks of the same stereotype that is used for the other gender – ‘Be a Man.’ Children who are constantly berated for talking back, or expressing their opinions out loud, are brainwashed into thinking that it is ‘unbecoming’ to argue (in case of women), or cry (in case of men); these children grow up to develop an inferiority complex so strong, that they cannot even raise their voices in opposition to wrong things. These children bear the weight of this nonsensical societal expectations of what a girl is, or what a man is, for the rest of their lives. In the case of women, this conditional suppression of their ability to speak up for themselves and stand for their own well being is one of the primary reasons behind their consistent subjugation. Not knowing any better, young girls adopt meekness, considering it to be a virtue, even at the cost of their lives. Is it inherent and internalized prejudice that leads us to assume girls as being somehow weaker or inferior than boys, even if they are not? Or to assume that expressing emotion, or crying, are somehow specifically feminine traits? If yes, this needs to stop now. Children do not have to bear the burden of their parents’ ideologies and prejudices. Let them discover what ‘behaving like a girl’ or ‘being a man’, means for themselves. “Daughters are someone else’s property, their real home is their husband’s” Daughters are someone else’s property. The home of their biological parents is not their home after all, their REAL homes are the ones they will have after marriage. (Betiyan toh paraya dhan hoti hain. Jab tak ho yahan theek hai, fer toh apne ghar jana hai.) I cannot believe parents still say this to their daughters. Why? It’s like adopting a child and then reminding that child every single day that they are adopted; where they are right now. I envy the girls who did not have to hear this thrown at them in their childhood. Even in jest, this is a statement that cuts to the bones of daughters. If you are a woman, reading this here, imagine for a second how it makes you feel. Does it remind you how much it hurt to hear your own parents say this to you when you were young? Why would any parent allow their own children to suffer from the same fate? Daughters are not things to be owned or possessed; they are individuals, human beings in their own right. Please stop. Never let children feel that they do not belong at their home, with their parents. Their REAL homes are wherever they choose to call their homes. Learn to cook. How will you feed your husband? Learn to cook. How will you feed your husband? In-laws will say your mother has not taught you anything. We are bearing all your tantrums, your in-laws will not suffer them. (Khana banana seekh lo. Pati ko kya khilaoge? Sasuraal wale kahenge maa ne kuch sikhaya nahi. Hum jhel rahe hain tumhare nakhre, sasural me koi nahi jhelega.) Learning to cook for oneself is a skill that everyone must acquire. Women are not born with the guidebook to be a MasterChefs. Having the capability to cook and feed oneself is not a gender specific trait, it is survival. Husbands do not need to be fed by their wives; nor do the in-laws. Threatening your daughters with the supposed repercussions they will face at the hands of their in-laws, is a poor way to handle their tantrums; it is just a way to delegate responsibility for your children to someone else. This not only sows the seed of doubt and fear in the hearts of young girls, regarding the whole institution of marriage, but also paints a poor picture of what they should be expecting from their future relatives. A peace based on fear, is no peace. Cooking and cleaning are not the only maternal legacies that matter. There are a horde of more significant traits that mothers can pass on to their daughters, like courage, determination, self-love and empathy. If you cannot cook and clean for yourself, you need some basic survival skills training asap; not a wife or daughter-in-law. Education is important, irrespective of gender and house-work is important, irrespective of gender.

Don’t wear such clothes. Good girls don’t talk to boys or stay out at night. Don’t wear such clothes. You look like a slut, a prostitute. Why are you wearing make-up? For whom? Good girls don’t talk to boys or stay out at night. They come home early. (Kaise kapde pehne hain? Vaishya lag rahi ho. Kiske liye kar rahe ho ye makeup? Achi ladkiyan ladkon se baatein nahi karti, raat ko bahar nahi ghumti. Jaldi ghar wapis aati hain.)

Although I admit that this is one of the many ways in which Indian parents warn their daughters of the atrocious crimes being committed against women, and I admit that it is extremely important to prepare our daughters to face a world where the dangers of assault are extremely real; I do not agree that this is how this subject should be approached. Believe it or not, daughters are going to come across pop culture sometime or other. They are going to be exposed to what is cool and what is not, they are going to be influenced by the generalised beauty standards of the world. There is nothing parents can do to stop that. What can be done, is to never aggressively deny or demean their choices of attire or make up. Let daughters wear whatever they want to, let them experiment with make-up however they want to. Remember that words have the power to wound, irreparably. What parents say matters. Never compare or judge daughters as ‘sluts’ or ‘prostitutes’; remember that children invariably end up doing exactly what is forbidden. It is always better to convey positive criticism and use words like – this dress does not suit you, or it does not flatter you like this other one – Be very careful of the words used, when speaking to your children. Parents must be open to uncomfortable conversations; no subject should be off-the-table. If children have questions, answer them in the best way possible; if you do not know, tell them that you do not know and attempt to find the best approach together. There is a veritable goldmine of information out there, FIGURE IT OUT. Because, children will find out about these things, one way or another, in today’s world of information overload, it is impossible to protect children from the ‘bad stuff’. The best way to prepare them for the world is to stay one step ahead of other sources; be approachable, discuss, educate. Create awareness of the potential dangers, so daughters can be willing partners in taking measures to protect themselves. Why this is important? Even in today’s so called progressive society, there is an inordinate amount of pressure being exerted on girls for marriage. We are raising daughters (girls in general) to aspire for marriage, and at the same time, we are not raising our sons to aspire for it. The value that women derive from the institution of marriage is far more than that of their male counterparts. This is the reason why there is a far greater number of women who choose to compromise and stay in abusive and toxic marriages, as compared to men. There is a vast difference in the values which we are instilling in our daughters and in our sons. The weight of expectation that we put on our daughters and women is blatantly unrealistic and unfair; and will eventually break them. We have to bring in change, and we have to bring it now. We need to know that if we want to raise strong, independent, self-respecting women, we must treat them as such; and at the same time, raise our sons to be strong, independent, self-respecting men. We must be willing to put in the effort and we must be wary of the words we use. The fate of the world lies in the hands of our children; and our children are our responsibilities.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

BDSM as a Logical Reaction to Monopoly Capitalistic Society

KATHERINE MEADOWS

Popular culture depicts BDSM (Bondage, Discipline/Domination, Submission/Sadism, Masochism), which utilizes sexual power dynamics as a means of furthering excitement and eroticism, in a way that generally distorts mainstream perception of practitioners. Ironically, by enforcing just one extreme of BDSM play, thereby painting the culture in a biased light, the media is demonstrating exactly what BDSM is confronting. Power is everywhere: present in institution-to-individual interactions as well as individual-to-individual interactions—including sexual relationships. In understanding how inextricably combined power and sex are, we can understand why power dynamics are the linchpin of BDSM play and get a more holistic view of this heavily misunderstood subculture.

Power is Everywhere

On bold-type phrases, interpret “power.”

To understand this concept, we have to examine what gives an entity power or what characterizes something with power. Power lends agency, running everything from machinery to the White House. As an abstract, power allows us to hold some capacity of control. Necessarily, this concept involves an exchange between an empowered entity and an entity lacking empowerment.

Forces in our atmosphere as well as the ground beneath our feet have a capacity to control where populations decide to live due to natural disasters and the motion of tectonic plates can kill.

Police officers also have the license to end a life—if they deem it necessary—and to deprive individuals of their freedom. Elected officials and representatives have abundant influence on the laws that govern our society and can even sway the governing forces of other nations. Power decides the rules and, if those rules are not followed, the repercussions. Those who have power can wage wars; the masses are the pawns of those with power.

Even micro interactions involve power exchange. The professor has the qualifications to grant a grade, and therefore, influence the likelihood that a student’s invested time, money, and hard work will result in a degree. It is within a parent’s hands to decide everything for their child until that child becomes an adult.

The Problem with Power

All of these positions that we identify with power also come with the potential for corruption. The parent, meant to act in the best interest of the child, may abuse that child or use the child in a myriad of inappropriate and dangerous ways. The professor may blackmail the student for something that they want.Those that govern our nation may cater to their own interests rather than those of the citizens they are in place to serve.

The police officer may use an unmonitored prejudice when they rationalize whether or not to use deadly force. The officer is prone to biases like anyone else, but because their position in society holds considerably more power, these biases carry more weight. If you’ve been paying any level of attention to the news or social media trends, you are probably aware that all of these problematic dynamics are both present and in a number of instances, allowed by the Monopoly Capitalist system to persist.

In a Monopoly Capitalist society, citizens serve a few functions. Not only are they the worker bees slaving away their libidos for the benefit of the 1 percent, they are simultaneously the consumers latching that dulled desire & stimulation to empty entertainment and luxury after unnecessary luxury; Lending their meager paychecks to those who make the profits. The Protestant values our society was built on (hard work is necessary for rewards and status) helped construct the path that most Americans are pressured to take. The school system teaches us that we must get a job to earn money so that we can buy the food and shelter that we need to survive, along with the most recent iPhone, clothing fad and other necessities.This system pressures us to go to places of higher education that shackle us to our debt in the name of a more prestigious existence (a specialized job with a higher income—and a more costly certification process). Yet, this upward mobility—a cornerstone of the “American Dream”—has never been easy in America. According to the The Equality of Opportunity Project, a child’s chances of “earning more than their parents have fallen from 90 percent to 50 percent over the past half century,” while the wage gap between the top and bottom percentiles grows broader. The America that is okay with these blatant disparities is the same nation that drives home the values, legislation, and economy that keep it this way.

The Role of Power in Identity

The world that we live in carries many forms of power that consistently determine our environment by limiting options, directing individuals toward one route instead of another, and largely shaping who we are. Foucault argued that power can now be understood as the “boundaries that enable and constrain [an individual’s] possibilities for action, and on people’s relative capacities to know and shape these boundaries.” Power sculpts who we are by being present in the influences on our “possibilities” from birth.

If you are born an American citizen, you were probably born in a hospital current on specific regulatory codes enforced by the dictation of the Department of Health. You were born in a healthy, clean environment, away from toxins and unsafe conditions. If you were born in a developing country, you may have come into the world undernourished, in a war zone, or into a poverty-stricken family. Already, two very separate tracks have been paved. If you went to public school growing up, you were taught logic and the scientific method for determining truth—as well as accepted organizations that presumably follow these methods and present the facts that the masses can invest in. If you went on to higher education, you learned the acceptable and unacceptable ways in which information is integrated into cultural understanding. The process by which we determine what information to let into the canon of accepted ideas is monitored by those with the responsibility to dictate which educational facilities will elevate or condemn. As a contrasting example, religious facilities may use other measures for truth, such as what is outlined in a sacred text. Socially, some use anecdotal (subjective, empirical) evidence, which is generally unaccepted in the scientific community. As Foucault detailed, “scientific discourse and institutions...are reinforced (and redefined) constantly through the education system, the media, and the flux of political and economic ideologies."

In the American school systems, you were taught the rules of this society by parents and peers alike: red means stop, killing people is wrong, the most important goal of life is to make money, etc. We gleaned all of our symbolic recognition, moral understandings, and ideological brainwashing from the culture and society we were socialized in. We were taught everything within the confines of what the overarching systems of control allowed us to learn.

Maybe we learned about these systems: ideology, corruption, etc.—and decided that we want less restriction and more freedom of action. Sometimes, we tested the limits of these systems of control; went over the speed limit one too many times and faced the repercussions. Sometimes, we learned and sometimes, we became more curious. Sometimes, we go farther and find ourselves in the almighty face of power—facing something more than just a $100 fine—facing a life sentence, facing mortality, facing crippling debt and repossession, facing ostracization and isolation—all methods of intense control.

Even if we didn’t encounter this backlash, we certainly grew up hearing about those who did. Part of our societal education is to learn about those who did not play by the rules and how they were made examples of. Now, fear becomes a mechanism of control, wielding power. Institutions, especially “prisons, schools, and mental hospitals” set a clear standard and promoting conformity in society. “Their systems of surveillance and assessment no longer required force or violence, as people learned to discipline themselves and behave in expected ways,”John Gaventa of adds.

Where BDSM Enters the Picture

Power permeates life in the ability to provoke something. Because of this fact, we are constantly surrounded by very subtle, inbred modes of control— constantly subjected to unquantifiable power dynamics, that we largely avoid consciously recognizing, because it would hinder functioning smoothly in this social system.

BDSM brings these power dynamics to the table and forces participants to recognize them and move within them. To understand these dynamics is a kind of power in itself because it is the first step in expanding the capacity for changing the instruments that alter and dictate who we are. Practitioners experience what it feels like to be entirely in control of the situation or to experience complete impotence (and not just if the scene gets weird). By allowing them to fully invest in roles they do and do not play within society, BDSM allows people to confront their staggering lack of power as an individual. Play can be very cathartic, with a potential for both great healing and great shattering.

Let’s Talk About Sex, Baby

Power permeates the sexual field similarly to the way it permeates institution-to-individual interactions. For example, sex may be used as an exchange for money or advantageous situations. Some individuals may find it empowering to entice others through sexual attraction, just as it is a show of empowerment to deny sexual interactions. Maybe you find the physical show of power (domination) as a turn on.

Generally in sex, a duo can be classified into one of two categories that do not necessarily align themselves with the opposing: Dominant and Submissive. One gives, one receives. One controls the situation, the other allows themself to be operated. This juxtaposition can go as vanilla as one person initiating or guiding the other or as intense as a BDSM scene that is orchestrated to follow an agreed upon script. There may be pairings of two Dominants and two Submissives, but the power play remains the same. How pronounced the power dynamics are determines where on the scale from “Conforming” to “Deviant” the sexual act falls.

Think about the nonverbal conversation that goes on during sex (inside and outside BDSM play), from the point of initiation. Perhaps it starts with a dialogue between the eyes—lingering just too long on the lips or body. When a hand crosses the threshold and is placed on a knee, an arm, or directly onto the other’s genitals, a question has been asked—namely, “is this okay?” If the person being touched is uninterested or has been read wrong, they will [ideally] verbally or nonverbally respond conveying that information. Or they may respond with another question: moving in to kiss the initiator or touching them back. The one acting is the one showing power, as power is the ability to do something specific. A couple may show power equally and at the same time. Or perhaps, one member of the group will take a stronger leading role, directing which positions are utilized. This isn’t to say that the passive member is void of power, as they always have the power to refuse advances (except in cases of harassment, coercion, sexual assault, and rape). Even during a sex act, if the Dominant directs the Submissive in a way that the sub dislikes, they can respond either verbally (“stop”) or physically by assuming a role of power and redirecting the action to something that does please them. Power often operates to benefit the entity with power; and in sex, the goal is generally that all parties involved get off in some way. To directly facilitate one’s own orgasm or excitement is to assume a role of power. To negate another’s eroticism is also a utilization of personal power. In this light, BDSM becomes a “set of tools for sandboxing...mainstream power dynamics,” according to freaksexual.com, “by providing a safe space to experience and confront, in a corporeal way, all levels of power and control.”

Conclusion

In a world where power permeates every interaction, social construct, and institution, human beings are constantly sculpted and directed by subtle forces that surround everything we know. By bringing these power dynamics into a space where they can be physically confronted, negotiated, and controlled in a way that is ultimately pleasurable, BDSM provides a cathartic release for the tensions that a Monopoly Capitalist society presents.

This article was published on the HerCulture blog. If you would like to submit an article, head on over to HerCulture to learn more about our writers and our magzine. Additionally, check out our social media (twitter, instagram, facebook, and tumblr!), our handles are herculture. Give this post a like and make sure you follow us on any of our accounts. By the end of December, we would like to reach our goal of 400 people on this tumblr account!

Start a culture revolution!

x Likhita

1 note

·

View note

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

Welcome to FiveThirtyEight’s weekly politics chat. The transcript below has been lightly edited.

micah (Micah Cohen, politics editor): We’re here to talk about superdelegates!!!!!!

Everyone’s favorite subject, right?

clare.malone (Clare Malone, senior political writer): Extremely 2016 up in here.

micah: (This is my least favorite topic.)

clare.malone: I can’t imagine why. It’s so sexy, and the debate is totally based in facts about what happened during 2016.

micah:

OK, so Democrats over the weekend curtailed the power of superdelegates a bit by changing the party’s nominating rules.

Here, from friend-of-the-site Josh Putnam at Frontloading HQ, is a description of the new system:

1. If a candidate wins 50 percent of the pledged delegates plus one during or by the end of primary season, then the superdelegates are barred from the first ballot. 2. If a candidate wins 50 percent of all of the delegates (including superdelegates) plus one, then the superdelegate opt-in is triggered and that faction of delegates can participate in the first (and only) round of voting. 3. If no candidate wins a majority of either pledged or all delegates during or by the end of primary season, then superdelegates are barred from the first round and allowed in to vote in the second round to break the stalemate.

Can someone give us a topline “what this means”?

natesilver (Nate Silver, editor in chief): It means that superdelegates can’t override the voters if someone gets 50 percent + 1 of pledged delegates.

It also means they could be hugely influential in the case of a multiballot convention, which is probably the more important case.

And it probably makes a multiballot convention more likely by not allowing superdelegates to be used as tiebreakers.

clare.malone: I think what they’re trying to do is mitigate the notion during the primary contest that “elites” have outsized weight.

We should note here that Hillary Clinton won more pledged delegates in 2016 than Bernie Sanders.

micah: Yeah, how much of this is PR vs. actually limiting the influence of superdelegates?

natesilver: Like so many other institutions, they’re catering to their critics and fighting the last war.

Like, I’m not even sure how I feel about superdelegates. I just think this is done for maybe the wrong reasons? And that the more interesting lessons were actually in the GOP primary in 2016?

clare.malone: I don’t know — it seems like a fair reaction in many ways.

I don’t think it’s bad to mitigate concerns that people in your base might have about stifling voter representation.

natesilver: Let’s say the pledged delegate allocation after everyone has voted is: Elizabeth Warren 40 percent, Joe Biden 30 percent, Cory Booker 20 percent, and 10 percent scattered among various other candidates who have since dropped out. Under the previous system, superdelegates would weigh in for Warren — who clearly is the most popular choice — and give her a majority on the first ballot.

Under the new system, the superdelegates don’t get to vote on the first ballot. Instead, they wait until the second ballot, when most of the pledged delegates become unpledged.

And there could be a lot more chaos here: Maybe Booker agrees to run as Biden’s VP, for instance.

clare.malone: Devil’s advocate: Why is it chaos? And even if it is chaos, why is it bad?

Are you arguing that it actually leads to back-room deals negating its supposed goal of democratizing the process?

natesilver: I’m saying that requiring an outright majority on the first ballot — no superdelegates to push a candidate who’s close to a majority over the top — coupled with Democrats’ extremely proportional delegate allocations — is a recipe for chaos

The chances of the nomination not being resolved on the first ballot are about 50 percent, maybe a little higher.

perry (Perry Bacon Jr., senior writer): I agree with that. I actually think under the previous system, Warren (or Sanders) was guaranteed to win in a scenario where she (or he) had the most delegates. That is less true now. The previous system gave superdelegates lots of power in theory. But in practice, supers were already bending to the will of the voters. Some superdelegates who originally backed Hillary Clinton flipped to Barack Obama in the latter stages of the 2008 Democratic primary, for example, once it became clear that he would win the most pledged delegates. That ensured that he got the majority of all delegates at the end.

clare.malone: I’ve decided to argue from the angle of the rules-changers. Aren’t you guys infantilizing the voters a bit? Yes, the process might be messier than in previous years, but on a second-round ballot where people are unpledged, you basically get to see a bit of a caucus happen among delegates. Maybe that sort of parliamentary way of doing things is healthy for the party.

Maybe what voters want is to see the process thrashed out, to see a second ballot!

micah: Woo!

natesilver: Maybe! But it goes against the stated aims of the reforms.

perry: And the changes don’t seem like a great advantage for the Sanders people, who pushed for them.

clare.malone: Well, the party is very different than it was in 2016.

So maybe the “center” or the “establishment” candidate will be closer to where Sanders is and it won’t matter … and the voters will be there too.

natesilver: I agree that it’s hard to predict who these changes will benefit. And, of course, there’s a long history of changes that were made with the best of intentions backfiring.

Democrats saw the train wreck that was the Republican nomination process in 2016 and decided to do nothing to prevent something similar happening to them, even though it looks like they could easily also have a 17-candidate field or thereabouts in 2020.

micah: So, using Nate’s hypothetical above — “Warren 40 percent, Biden 30 percent, Booker 20 percent, and 10 percent scattered among various other candidates” — doesn’t this come down to whether you think Warren winning a plurality means she should get the nomination or whether you think Warren not winning a majority means she shouldn’t get the nomination?

natesilver: I think Warren’s probably getting the nomination either way IN THOSE SCENARIOS , but she’s definitely at more risk under the new system.

clare.malone: Maybe it’s a healthier process for a party that has actual divisions.

natesilver: Now, maybe there are some cases where the opposite is true. If you have a case where it’s Kamala Harris 51 percent, Joe Biden 48 percent, Martin O’Malley 1 percent of the pledged delegates — Harris is now guaranteed the nomination, whereas supers could have pushed it to Biden before.

But if it’s Harris 49 percent, Biden 46 percent, O’Malley 5 percent, she’s not.

clare.malone: It’s basically just more of a wild-card system.

(As a side note, as a journalist, I look forward to the potential drama.)

natesilver: What saved the Republicans from a contested convention of their own in 2016 was the fact that a lot of their primaries, especially toward the end stages, were winner-take-all or winner-take-most. That allowed Donald Trump to build up some real momentum in the last one-third or so of the primary calendar.

Without that, the GOP would probably have still gotten Trump anyway — he was clearly the choice of the plurality of voters — but only after an extremely chaotic convention.

perry: I don’t think the big goal (stopping supers from overturning the plurality of the pledged delegates) is necessarily best served by these particular reforms. That said, on the broader question of whether superdelegates SHOULD be able overturn the plurality of pledged delegates, I think there is a case for superdelegates to have that power. I’m not completely sure superdelegates should be disempowered, even though I agree with arguments that the will of the people should be respected and am generally for giving voters more power. The last two years (so Trump) have suggested that maybe party elders should play a bigger role, not necessarily in pushing for a different person ideologically, but maybe a president who abides by general norms. (For example, I think Ted Cruz would be as conservative as Trump, but perhaps less erratic and able to condemn white nationalist rallies.) I’m not sure if, say, Michael Avenatti has a chance of winning the Democratic nomination in 2020, but I bet a lot of Democratic Party elders are not excited at that prospect–and would like to have the power to stop it.

In other words, maybe the elites should have more power?

micah: I’m a secret believer in that.

clare.malone: Why? To prevent chaos?

micah: Because the mob can be dangerous.

clare.malone: Why are you guys harping on that?

I think there’s something to be said about a cathartic political process.

Voters have watched their nominations be manufactured behind the scenes. What’s wrong with radical transparency?

Yes, it might bring a couple of rounds of voting, I concede that. But you haven’t convinced me why that’s bad in the end? As long as there’s civility among the actors, which I think you could engineer, it’s not a terrible scenario.

natesilver: The expectation among voters is that the most popular nominee will get the nomination.

Granted, there are different ways of defining “most popular.”

clare.malone: Which would likely be reflected in the contested convention votes. Right?

Norms have been less broken on the Democratic side of things, so I don’t think that’s an unreasonable expectation.

natesilver: Maybe? But the more ballots you go, the more divorced you become from the delegates’ original preferences.

We knew on the GOP side, for example, that many delegates personally didn’t back Trump and were big risks to turn on him in the event of multiple ballots even though they were bound to him on the first ballot.

A better-organized campaign will exert more control over the delegate selection process and be better at whipping delegates.

perry: I guess I view these rules as being a diss to the superdelegates. The supers themselves read them that way too.

clare.malone: That’s the point, though. They’re meant to diss. It’s the mood of the party’s hoi polloi.

perry: If Sanders or another candidate who is anti-superdelegates does not win a majority of pledged delegates during the primary, he should be worried. I wonder if the supers, on the second ballot, are even more unbound under this new system, compared to the old one. They could say, “You [Sanders’ supporters] said you wanted a system in which a majority of pledged delegates means you win. You didn’t get a majority. We get to intervene now. These are your rules. We are following them and we will now choose who WE want.”

micah: OK, let’s try it this way: Would these rules, had they been in place, have altered any past Democratic nominations?

Would Clinton have had a better chance in 2008?

perry: This is where I would like to do a more careful analysis.

But, yes, my instinct is that Clinton would have had a better chance to win on a second ballot in this new system. The superdelegates would have no role in the first ballot, but I think their role is enhanced in a second one.

natesilver: There are some primaries, such as in 1984 and 2008, where the nomination process would have been messier, although maybe it would have produced the same nominee.

clare.malone: I smell an assignment …

And then some fan fic about the alternate political universes.

natesilver: Yeah. My thing is that you want a system where someone can win on the first ballot with less than a majority, but with a reasonably clear plurality. Because it’s very common for the top candidate to have something like 35 percent to 45 percent of the overall votes in the primary.

There are two ways to achieve that: either through superdelegates or through winner-take-all/winner-take-most rules.

The Democrats have neither one of those now.

clare.malone: Maybe this is finally a concession to the big tent party that they have. And in the ensuing rounds of ballot negotiation, maybe you have compromises on who gets VP — like, a Warren paired with a more centrist person — we’ll see who comes along over the next couple of years.

micah: IDK, maybe I agree with Clare: Democracy is messy, so maybe it should look messy.

perry: I think those changes might be good (the ones Clare laid out). The idea that the convention picks the vp. But they give the elites more power.

Sanders does not want the party to pick his vp.

clare.malone: Well, that’s the concession he has to pay to be more of a player.

People have sold their souls for much less. A compromise VP when you’re the presidential nominee of a party in semi-shock therapy ain’t bad.

natesilver: One simple reform they could have considered is to give the nomination to whomever wins the plurality of delegates. Except in a few weird states, that’s how our electoral system works: Plurality takes all.

micah: Or: National popular vote. Simple. One day of voting. Highest vote-getter takes all.

perry: Can we jump back to the broader context?

The reason I am open to elites having more power is because Trump is different in terms of democratic norms, etc. I think Sanders would be better than Avenatti in terms of following those norms.

And the voters might blow it.

If we have weak parties and strong partisanship, do we want to weaken the parties further?

I’m not usually an elitist, but are we sure the voters are doing a great job?

clare.malone: This feels like the old argument against direct election of U.S. senators.

It basically comes down to the age-old question: Do we trust the vox populi?

micah: No.

clare.malone: Haha, so now you’ve switched teams!

micah: lol

Just kidding.

Do you?

How much “republic” do you want in your democratic republic?

clare.malone: I’m still arguing team small-d democracy.

natesilver: There’s also the question of whether ranked-choice voting would produce a different result. Like, suppose that Avenatti was the plurality front-runner with 20 percent of the vote. But most of the other 80 percent who didn’t vote for him didn’t like him.

clare.malone: I think you’ve got to have some faith in the voters.

perry: I want to.

natesilver: Although the GOP doesn’t have superdelegates per se, the fact that the party made relatively feeble efforts to stop Trump is also relevant here. It suggests the norm toward letting voters decide is quite strong.

And the stronger that norm is, the less dangerous that superdelegates are.

micah: I think Perry said this earlier, but I do think there’s a chance this empowers supers because it will erode that norm on the second ballot.

perry: Yeah, that is what I was hinting at — particularly if it’s something like Sanders 44 percent and Harris or Booker or Julian Castro (a non-white candidate) at 41.

natesilver: THEY’RE GOING TO STEAL THE NOMINATION FROM AVENATTI

clare.malone: I mean, he’s got his Vogue story in place.

Next comes the chummy Ellen interview.

perry: FiveThirtyEight contributor Seth Masket wrote that there was a big racial divide at the DNC meeting where this change was adopted, namely that some prominent black officials are opposed to the changes.

The Congressional Black Caucus, for example, likes the power of superdelegates in the current system. (Members of Congress are superdelegates, of course.)

clare.malone: Donna Brazile was making the argument that the DNC was trying to disenfranchise them.

micah: Why do you think there’s a racial divide?

perry: Because there is a big racial divide among party elites about Sanders.

Sanders did well among young black voters. But I suspect that he has very little support among black superdelegates.

natesilver: And there’s also the question of: What if in a close race, you had one Democrat with a plurality of votes/delegates but very little support among black or Hispanic Democrats.

You could argue that’s a case where supers should intervene. I’m not sure I like that argument, but you could make it.

Although, again, in any type of plurality scenario, the supers get to intervene anyway.

micah: How about this for a compromise: Have superdelegates but only let elected officials be them.

natesilver: Many/most of them are elected officials anyway?

clare.malone: Yeah.

micah: Not all, though.

perry: Most superdelegates are DNC members, according to the Pew Research Center, not members of Congress. But some of those DNC members might be elected officials at the local level.

micah: BAM!

clare.malone: I love that one of the subcategories of superdelegates is “distinguished party leaders.” Lol.

natesilver: How about: Let the nowcast decide in the event that no one gets the plurality?

perry: Nate Silver picks which candidate is most electable.

natesilver: Hahaha

hahahahaha

perry: If we pitched this idea to Democratic voters, that Nate picks the candidate or the DNC picks, they would probably go with Nate. I’m serious. I don’t think most Democrats trust the party that much.

natesilver: But see the most electable candidate would be the one with the most popular support.

clare.malone: O’Malley’s gonna make a comeback in that case.

micah: If all the supers were elected officials, it would still have a tinge of small-d democracy. It’s a good middle ground!

perry: That seems right to me. They would be accountable.

That’s the problem with the DNC — people don’t necessarily know who those people are.

natesilver: How about if there’s no majority through the delegate system, there’s a national 50-state referendum where everyone votes again?

That would obviously be cost/logistically prohibitive.

In some very real ways, though, polls could become very important under that scenario. For example, it was probably important in 2008 that Obama never fell behind Clinton in national polls, or at least not for sustained periods, when going through all the Jeremiah Wright stuff, etc.

perry: I’m going to play the Micah role here, because I was curious what Nate’s and Clare’s thoughts were about the caucus changes.

micah: Yeah, let’s close on that. Can someone give me a summary of the caucus changes please?

natesilver: My understanding is that caucuses now need to include a means for people to participate off-site — e.g., through absentee ballots.

perry: Right.

clare.malone: I think it’s probably a shift toward the right kind of “small d democracy” change I’ve been talking about. There are lots of good arguments that say caucuses mean that a lot of people who do shift work can’t vote.

natesilver: Caucuses tend to favor candidates whose supporters are (1) more enthusiastic and (2) better organized. I’m not sure that necessarily maps cleanly onto a left-right scale, and it can be fairly idiosyncratic from election to election who does better in caucuses.

clare.malone: Caucuses tend to favor insurgents, it’s fair to say.

natesilver: They didn’t in the GOP, though.

clare.malone: On the Democratic side they have, right?

natesilver: Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz (OK, Cruz is sort of an insurgent) did better in caucuses, and Trump struggled in them.

I think that’s mostly true.

In 1988, Jesse Jackson struggled in caucuses early on but then started to do quite well in them. It can be quirky.

Also, a lot of states have abandoned caucuses of their own volition and switched to primaries.

perry: So is this a big change?

natesilver: It’s not big in the sense that the Democrats didn’t have that many caucuses anyway, and they were mostly in small-population states.

However, there are often big differences between who does well in caucuses and who does well in primaries.

Without caucuses, Clinton might have won in 2008.

Without caucuses, Sanders wouldn’t have lasted nearly as long.

If the GOP had more caucuses, they might not have chosen Trump.

micah: To wrap, does anyone want to say whether all these changes help or hurt any specific potential 2020 candidates?

Or do we really just have no clue?

clare.malone: I think you have to wait and see what their support/activist system is like.

natesilver: Yeah, we’re at the stage where there are 15 billiard balls on the table and it’s hard to know what everything will look like after the break.

Again, my

take is just that it’s a bad idea to have neither superdelegates nor winner-take-all/most rules. Especially in a year without a clear front-runner.

micah: OK, to sum up, it seems like the best take is: These changes could have big unforeseen and unintended consequences — or maybe not. And to cap us off, I asked Julia (who has studied this a lot) to give us her take …

julia_azari (Julia Azari, political science professor at Marquette University and FiveThirtyEight contributor): I’m more ambivalent about the superdelegate change than a lot of political scientists, many of whom are generally opposed to them. This is mainly because I think parties need to think about how they can regain legitimacy, and if supers are left out of the first ballot but can legitimately come in in the case of a deadlocked convention, that’s a good thing.

Acknowledging the possibility that the nomination might not be wrapped up by the convention and that that could be something other than a total crisis is in my view a good thing. The emphasis on party elites unifying around a single candidate early in the nomination — in either party — hampers competition within the party and potentially prevents voters from having real power in the nomination process.. At the same time, my understanding is that none of the rules change anything about how elected officials can make their preferences known during and before the primary season (so people who are superdelegates can still endorse someone ,even if that endorsement is not effectively a delegate vote in this new process), and that will rightly be seen by some in (for lack of a better term) the Bernie camp as attempting to tip the scales in favor of more establishment candidates. If you could actually have a competitive convention without it being seen as a giant disaster, then elites wouldn’t need to head that off by endorsing early.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tony Blair, The War Criminal Ghoul: Why We Must Not Abandon the People of Afghanistan – For Their Sakes and Ours

— August 21, 2021

The abandonment of Afghanistan and its people is tragic, dangerous, unnecessary, not in their interests and not in ours. In the aftermath of the decision to return Afghanistan to the same group from which the carnage of 9/11 arose, and in a manner that seems almost designed to parade our humiliation, the question posed by allies and enemies alike is: has the West lost its strategic will? Meaning: is it able to learn from experience, think strategically, define our interests strategically and on that basis commit strategically? Is long term a concept we are still capable of grasping? Is the nature of our politics now inconsistent with the assertion of our traditional global leadership role? And do we care?

As the leader of our country when we took the decision to join the United States in removing the Taliban from power – and who saw the high hopes we had of what we could achieve for the people and the world subside under the weight of bitter reality – I know better than most how difficult the decisions of leadership are, and how easy it is to be critical and how hard to be constructive.

Almost 20 years ago, following the slaughter of 3,000 people on US soil on 11 September, the world was in turmoil. The attacks were organised out of Afghanistan by al-Qaeda, an Islamist terrorist group given protection and assistance by the Taliban. We forget this now, but the world was spinning on its axis. We feared further attacks, possibly worse. The Taliban were given an ultimatum: yield up the al-Qaeda leadership or be removed from power so that Afghanistan could not be used for further attacks. They refused. We felt there was no safer alternative for our security than keeping our word.

We held out the prospect, backed by substantial commitment, of turning Afghanistan from a failed terror state into a functioning democracy on the mend. It may have been a misplaced ambition, but it was not an ignoble one. There is no doubt that in the years that followed we made mistakes, some serious. But the reaction to our mistakes has been, unfortunately, further mistakes. Today we are in a mood that seems to regard the bringing of democracy as a utopian delusion and intervention, virtually of any sort, as a fool’s errand.

The world is now uncertain of where the West stands because it is so obvious that the decision to withdraw from Afghanistan in this way was driven not by grand strategy but by politics.

We didn't need to do it. We chose to do it. We did it in obedience to an imbecilic political slogan about ending “the forever wars”, as if our engagement in 2021 was remotely comparable to our commitment 20 or even ten years ago, and in circumstances in which troop numbers had declined to a minimum and no allied soldier had lost their life in combat for 18 months.

We did it in the knowledge that though worse than imperfect, and though immensely fragile, there were real gains over the past 20 years. And for anyone who disputes that, read the heartbreaking laments from every section of Afghan society as to what they fear will now be lost. Gains in living standards, education particularly of girls, gains in freedom. Not nearly what we hoped or wanted. But not nothing. Something worth defending. Worth protecting.

We did it when the sacrifices of our troops had made those fragile gains our duty to preserve.

We did it when the February 2020 agreement, itself replete with concessions to the Taliban, by which the US agreed to withdraw if the Taliban negotiated a broad-based government and protected civilians, had been violated daily and derisively.

We did it with every jihadist group around the world cheering.

Russia, China and Iran will see and take advantage. Anyone given commitments by Western leaders will understandably regard them as unstable currency.

We did it because our politics seemed to demand it. And that’s the worry of our allies and the source of rejoicing in those who wish us ill.

They think Western politics is broken.

Unsurprisingly therefore friends and foes ask: is this a moment when the West is in epoch-changing retreat?

I can't believe we are in such retreat, but we are going to have to give tangible demonstration that we are not.

This demands an immediate response in respect of Afghanistan. And then measured and clear articulation of where we stand for the future.

We must evacuate and give sanctuary to those to whom we have responsibility – those Afghans who helped us, stood by us and have a right to demand we stand by them. There must be no repetition of arbitrary deadlines. We have a moral obligation to keep at it until all those who need to be are evacuated. And we should do so not grudgingly but out of a deep sense of humanity and responsibility.

We need then to work out a means of dealing with the Taliban and exerting maximum pressure on them. This is not as empty as it seems. We have given up much of our leverage, but we retain some. The Taliban will face very difficult decisions and likely divide deeply over them. The country, its finances and public-sector workforce are significantly dependent on aid notably from the US, Japan, the UK and others. The average age of the population is 18. A majority of Afghans have known freedom and not known the Taliban regime. They will not all conform quietly.

The UK, as the current G7 chair, should convene a Contact Group of the G7 and other key nations, and commit to coordinating help to the Afghan people and holding the new regime to account. NATO – which has had 8,000 troops present in Afghanistan alongside the US – and Europe should be brought fully into cooperation under this grouping.

We need to draw up a list of incentives, sanctions and actions we can take, including to protect the civilian population so the Taliban understand their actions will have consequences.

This is urgent. The disarray of the past weeks needs to be replaced by something resembling coherence, and with a plan that is credible and realistic.

But then we must answer that overarching question. What are our strategic interests and are we prepared any longer to commit to upholding them?

Compare the Western position with that of President Putin. When the Arab Spring convulsed the Middle East and North Africa toppling regime after regime, he perceived that Russia’s interests were at stake. In particular, in Syria, he believed that Russia needed Assad to stay in power. While the West hesitated and then finally achieved the worst of all worlds – refusing to negotiate with Assad, but not doing anything to remove him, even when he used chemical weapons against his own people – Putin committed. He has spent ten years in open-ended commitment. And though he was intervening to prop up a dictatorship and we were intervening to suppress one, he, along with the Iranians, secured his goal. Likewise, though we removed the Qaddafi government in Libya, it is Russia, not us, who has influence over the future.

Afghanistan was hard to govern all through the 20 years of our time there. And of course, there were mistakes and miscalculations. But we shouldn’t dupe ourselves into thinking it was ever going to be anything other than tough, when there was an internal insurgency combining with external support – in this case, Pakistan – to destabilise the country and thwart its progress.

The Afghan army didn’t hold up once US support was cancelled, but 60,000 Afghan soldiers gave their lives, and any army would have suffered a collapse in morale when effective air support vital for troops in the field was scuttled by the overnight withdrawal of maintenance.

There was endemic corruption in government, but there were also good people doing good work to the benefit of the people.

Read the excellent summary of what we got right and wrong from General Petraeus in his New Yorker interview.

It often dashed our hopes, but it was never hopeless.

Despite everything, if it mattered strategically, it was worth persevering provided that the cost was not inordinate and here it wasn't.

If it matters, you go through the pain. Even when you are rightly disheartened, you can't lose heart completely. Your friends need to feel it and your foes need to know it.

“If it matters.”

So: does it? Is what is happening in Afghanistan part of a picture that concerns our strategic interests and engages them profoundly?

Some would say no. We have not had another attack on the scale of 9/11, though no-one knows whether that is because of what we did post 9/11 or despite it. You could say that terrorism remains a threat but not one that occupies the thoughts of a lot of our citizens, certainly not to the degree in the years following 9/11.

You could see different elements of jihadism as disconnected, with local causes and containable with modern intelligence.

I would still argue that even if this were right and the action in removing the Taliban in November 2001 was unnecessary, the decision to withdraw was wrong. But it wouldn’t make this a turning point in geopolitics.

But let me make the alternative case – that the Taliban is part of a bigger picture that should concern us strategically.

The 9/11 attack exploded into our consciousness because of its severity and horror. But the motivation for such an atrocity arose from an ideology many years in development. I will call it “Radical Islam” for want of a better term. As a research paper shortly to be published by my Institute shows, this ideology in different forms, and with varying degrees of extremism, has been almost 100 years in gestation.

Its essence is the belief that Muslim people are disrespected and disadvantaged because they are oppressed by outside powers and their own corrupt leadership, and that the answer lies in Islam returning to its roots, creating a state based not on nations but on religion, with society and politics governed by a strict and fundamentalist view of Islam.

It is the turning of the religion of Islam into a political ideology and, of necessity, an exclusionary and extreme one because in a multi-faith and multicultural world, it holds there is only one true faith and we should all conform to it.

Over the past decades and well before 9/11, it was gaining in strength. The 1979 Iranian Islamic Revolution and its echo in the failed storming of the Grand Mosque in Mecca in late 1979 massively boosted the forces of this radicalism. The Muslim Brotherhood became a substantial movement. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan saw jihadism rise.

In time other groups have sprung up: Boko Haram, al-Shabab, al-Qaeda, ISIS and many others.

Some are violent. Some not. Sometimes they fight each other. But at other times, as with Iran and al-Qaeda, they cooperate. But all subscribe to basic elements of the same ideology.

Today, there is a vast process of destabilisation going on in the Sahel, the group of countries across the northern part of sub-Saharan Africa. This will be the next wave of extremism and immigration that will inevitably hit Europe.

My Institute works in many African countries. Barely a president I know does not think this is a huge problem for them and for some it is becoming THE problem.

Iran uses proxies like Hizbullah to undermine moderate Arab countries in the Middle East. Lebanon is teetering on the brink of collapse.

Turkey has moved increasingly down the Islamist path in recent years.

In the West, we have sections of our own Muslim communities radicalised.

Even more moderate Muslim nations such as Indonesia and Malaysia have, over a period of decades, seen their politics become more Islamic in practice and discourse.

Look no further than Pakistan’s prime minister congratulating the Taliban on their “victory” to see that although, of course, many of those espousing Islamism are opposed to violence, they share ideological characteristics with many of those who use it – and a world view that is constantly presenting Islam as under siege from the West.

Islamism is a long-term structural challenge because it is an ideology utterly inconsistent with modern societies based on tolerance and secular government.

Yet Western policymakers can't even agree to call it “Radical Islam”. We prefer to identify it as a set of disconnected challenges, each to be dealt with separately.

If we did define it as a strategic challenge, and saw it in whole and not as parts, we would never have taken the decision to pull out of Afghanistan.

We are in the wrong rhythm of thinking in relation to Radical Islam. With Revolutionary Communism, we recognised it as a threat of a strategic nature, which required us to confront it both ideologically and with security measures. It lasted more than 70 years. Throughout that time, we would never have dreamt of saying, “well, we have been at this for a long time, we should just give up.”

We knew we had to have the will, the capacity and the staying power to see it through. There were different arenas of conflict and engagement, different dimensions, varying volumes of anxiety as the threat ebbed and flowed.

But we understood it was a real menace and we combined across nations and parties to deal with it.

This is what we need to decide now with Radical Islam. Is it a strategic threat? If so, how do those opposed to it including within Islam, combine to defeat it?

We have learnt the perils of intervention in the way we intervened in Afghanistan, Iraq and indeed Libya. But non-intervention is also policy with consequence.

What is absurd is to believe the choice is between what we did in the first decade after 9/11 and the retreat we are witnessing now: to treat our full-scale military intervention of November 2001 as of the same nature as the secure and support mission in Afghanistan of recent times.

Intervention can take many forms. We need to do it learning the proper lessons of the past 20 years according not to our short-term politics, but our long-term strategic interests.

But intervention requires commitment. Not time limited by political timetables but by obedience to goals.

For Britain and the US, these questions are acute. The absence of across-the-aisle consensus and collaboration and the deep politicisation of foreign policy and security issues is visibly atrophying US power. And for Britain, out of Europe and suffering the end of the Afghanistan mission by our greatest ally with little or no consultation, we have serious reflection to do. We don’t see it yet. But we are at risk of relegation to the second division of global powers. Maybe we don’t mind. But we should at least take the decision deliberatively.

There are of course many other important issues in geopolitics: Covid-19, climate, the rise of China, poverty, disease and development.

But sometimes an issue comes to mean something not only in its own right but as a metaphor, as a clue to the state of things and the state of peoples.

If the West wants to shape the 21st century, it will take commitment. Through thick and thin. When it’s rough as well as easy. Making sure allies have confidence and opponents caution. Accumulating a reputation for constancy and respect for the plan we have and the skill in its implementation.

It will require parts of the right in politics to understand that isolation in an interconnected world is self-defeating, and parts of the left to accept that intervention can sometimes be necessary to uphold our values.

It requires us to learn lessons from the 20 years since 9/11 in a spirit of humility – and the respectful exchange of different points of view – but also with a sense of rediscovery that we in the West represent values and interests worth being proud of and defending.

And that commitment to those values and interests needs to define our politics and not our politics define our commitment.

This is the large strategic question posed by these last days of chaos in Afghanistan. And on the answer will depend the world’s view of us and our view of ourselves.

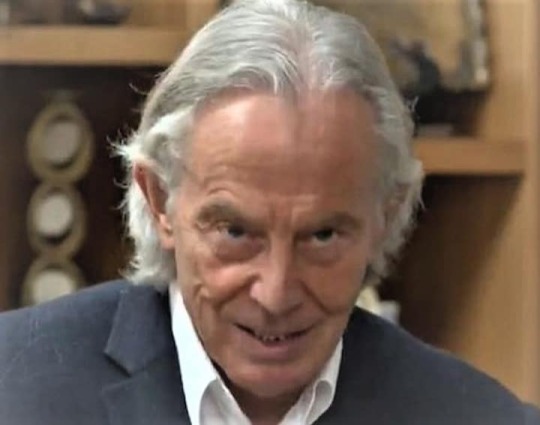

— War Criminal Ghoul Tony Blair: Former Prime Minister of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and Executive Chairman of the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change

0 notes

Text

Wendy McElroy: Interview With Jeffrey Tucker on All Things Crypto, Part Two

Wendy McElroy: Interview With Jeffrey Tucker on All Things Crypto, Part Two

Featured

Interview with Jeffrey Tucker on All Things Crypto, Part Two

Conducted by Wendy McElroy

The multi-faceted Jeffrey Tucker is an American writer who focuses on market freedom, anarcho-capitalism, and cryptotech. He is the author of eight books on economics, politics, and culture, a much-sought after conference speaker, and an Internet entrepreneur. Jeffrey is editorial director and vice president of the venerable American Institute for Economic Research, founded in 1933. His career has focused on building many of the web’s primary portals for commentary and research on liberty, and is undertaking new adventures in publishing today.

I have incredible good fortune, as Jeff has written the preface to my book “The Satoshi Revolution,” which will be published in early 2019 by bitcoin.com. Meanwhile, a rough draft of the book is available online for free, compliments of bitcoin.com. Be sure to come back for the substantially-rewritten and thoroughly-edited book. I expect there will be a forum established here for me to chat with readers and answer their questions.

To access Part One of this interview, please click here.

Wendy: I was very impressed by an article in which you argued against the idea that Misesian regression theorem invalidated bitcoin as a money. For readers, the Regression theorem claims “Any valid medium of exchange (money) has to have a previous use as something else.” Could you offer an overview of your argument?

Jeff: Mises’s argument was that the root value of money traces to a conjectural history in which the pre-money form was deployed, for example, in barter. By 1949, Mises became hardened in this view: money had to originate in barter; there is no other path. From a historical point of view, this is probably correct. But it is a theoretically misleading formulation.

To understand the theory behind the conjectural history, you have to return to Mises’s original 1912 argument. Here he is more precise. In order for something to become money, it had to have a pre-existing use value. Use value. That’s not the same thing as being used in barter trade. His point was that you can’t take a useless thing and call it money and expect it to take flight.

How can we reconstruct the history of Bitcoin to discern if this applies here? From the January 2009 genesis block until October of that year, Bitcoin’s posted dollar exchange value was exactly $0. And yet we know, because we have a perfect historical record, that there were many thousands of trades being made all these 10 months. What was happening? What was going on? This was a period in which the network was being tested by enthusiasts. What does this network do? It permits the peer-to-peer exchange of immutable information packets on a geographically non-contiguous basis using the Internet so that they can come and go without corruption or compromise.

Is this a valuable service and does it work? This is what was being tested. By October, the use value of this network had proven itself, and so we began to see the emergence of a dollar/Bitcoin exchange ratio. That is to say, Bitcoin was priced as a scarce good. We can see, then, that the conditions of the “Regression Theorem” as theory are met via the services provided by the blockchain. You can also see, however, that if an economist looking at this did not understand the payment system embedded as part of the monetary technology, he or she would be completely befuddled.

To be sure, some very smart people disagree with me. My friend William Luther is blunt about his opinion about his matter. He thinks the Regression Theorem is just wrong, so it doesn’t matter if Bitcoin is theoretically compliant. He once made the argument to me and pretty much backed me into a corner. If he turns out to be correct, I’m fine with that. What matters more, my theory or existing reality? I faced that problem in early 2013 and concluded that I had, as a matter of intellectual integrity, to defer to reality, even if it meant admitting the wrongness of my position or even that of Mises’s. Shocking, I know!

Wendy: The crypto community parallels the libertarian one, in ways both good and bad. An example of the latter is the deep personal schisms with which it is rift. You are a person who stays away from internecine battles. What advice do you have to others who wish to do the same?

Jeff: I try to stay focused on the big picture and imagine that my audience is not my friend network but rather the general public. I try to serve that readership. That means no Twitter wars. No flame wars at all. Plus, I’ve seen vast destruction spread by vicious internecine battles. I’ve seen friendships wrecked, bad theory perpetrated by virtue of ego alone, massive setbacks take place in understanding and marketing. Also, there are some people who are ideologically attached to the friend/enemy distinction. Unless they are smashing someone and hitting “the enemy” they think they are not working. It’s extremely strange how some people thrive off this posture.

To be sure, I have no trouble taking a stand, as I have when libertarians have wrongly drifted left and right. Why? I like to seek greater intellectual clarity and share my thoughts with others, in hopes that I can help others understand too. I’m not seeking saints and not looking to burn witches. I try to choose my battles carefully and stay focused on doing productive work, cooperating with anyone who thinks, writes, and acts in good faith. That’s the main thing to ask yourself, not “Who have you destroyed today?” but rather, “What kind of light have I brought to the world today?”

Wendy: Different explanations of crypto’s recent plunge in price have been advanced. Some people point to increased government regulation, especially in China and in the U.S., where the SEC is taking active steps against the crypto community. Many believe the tumble resulted from a bursting bubble that was created by surging prices earlier in 2018. Still others speak of manipulation by “the whales.” These explanations are not mutually exclusive, of course. But do you favor one over the other? Do you have another explanation?

Jeff: It’s impossible to untangle all of this, and many of the factors you name are right, but let me add another issue. The amazing bull market of 2017 was fueled by wild optimism and adoption. People in the space were ready to rock. Then this optimism was massively interrupted by a terrible realization. Bitcoin would not scale. It stopped behaving like Bitcoin and started becoming more expensive and slower than regular credit cards. To use street parlance, it sucked. It was an amazing thing to have happened. It was a true calamity. And to top it off, it was completely the fault of the guardians of the code. When the code would not adapt to broader use, the optimism turned to pessimism and we experienced a huge setback.

By the way, I’ve worked for years with people who are geniuses at code but completely stupid when it comes to the user experience. It was the tragedy of Bitcoin that it fell prey to exactly this same problem. Coders desperately desire cleanliness, zero bloat, no cruft, perfect logic. It’s an old joke in the community that a coder invites you to use his new program but all you see on the black screen is a blinking green cursor. “Of course I still have to write the user interface.”

The OCD-ish mind of coders is a great thing for some purposes but this outlook has never prevailed in the commercial marketplace. In the early 1990s, there was a great battle over word processors. Microsoft kept making Word larger and larger, puffed with cruft, and the code monkeys were screaming that this was a disaster in the making. For my own part, I hated Word in those days and completely agreed that the hard-to-use light-weight programs were better.

But guess what? The market disagreed. Moore’s Law kicked it as it always does and eventually Word destroyed the competition. Why? Because it had more features that users like. Eventually the code got clean again and now Word itself has many elegant competitors. This is the normal progression of any software with a consumer focus.

Incredibly, some people with the keys to the kingdom of Bitcoin actually came to imagine that they could develop a digital money without an efficient, consumer-focussed use case. They drove a wedge between two functions: store of value and medium of exchange. This is not how much work. One function depends on the other. The freeze in the development of Bitcoin, in the name of staying light and elegant, was a fool’s errand. During all the scaling debates of 2014-16, they dug in their heels, shouting slogans, guarding their small blocks, instead of thinking about adoption and scaling when the time came.

When the time did come, Bitcoin did not perform. It fact – and it pains me to say this – it completely flopped.

Old school Bitcoiners like me were horrified to see it all happening. It was like an old friend had become possessed. When the mempools exploded, and the miners were in a position to ration trades based on price, it would cost $20 to send $2. This was in the fall and winter of 2017. It was absolutely disgraceful, and all the more so because the newly emergent “maximalists” defended this preposterous reality, acting if as this was part of the plan all along. They were like PeeWee Herman explaining that when he fell off the bike that he “meant to do that.” They flagrantly ignored even the title of the White Paper. Then the fork came in August of 2017, as it necessarily had to. But then followed a tremendous explosion of tokens of all sorts.

I don’t regret the competition, and I think this is all a good thing. I’m not a Bitcoin Maximalist. I’m a Competition Maximalist. But the absurdities of Bitcoin’s performance could have been completely avoided with just a bit of concern for the user. I would love it if we could perform a controlled experiment and see the BTC price today if the thing had properly scaled. We can’t do that. We have the reality we have.

Privately, of course, Bitcoin Core developers will admit that this was a disaster and that scaling will eventually take place on the chain. But at this point, pride and arrogance had gotten the best of them. How long will they continue to promise the Lightning Network while showing no concern for the use case? It’s time for a bit of humility.

To be sure, the Lightning Network is super great. We run a node at the Atlanta Bitcoin Embassy. I look forward to its final stability and adoption. The problem is that this was proposed as an eventual solution to the scaling problem that currently exists. Real-time technological development has to deal with problems in real time according to the time schedule of the market rate of adoption. Markets don’t obey code architects; the reverse has to be the case. Bitcoin Core forgot that at the very point it mattered most.

Wendy: Whatever the probable explanation(s), do you have a sense of when or whether crypto markets are likely to rebound significantly? Do you have a sense of what will cause a rebound or prevent one?

Jeff: Like all enthusiasts, I do expect a turnaround. Remember that I’ve been in these markets since BTC was $14. I’ve seen wild swings and long periods of nothingness. I’m prepared for anything.

Wendy: A debate within crypto parallels one I have heard between gold bugs. That is, should one take physical possession of precious metals, or they can be stored with reputable entities. In crypto, the parallel argument is whether coins should be in private wallets with undisclosed keys, or can they be stored with exchanges that do not demand possession of the keys?