#(99.9% of people fail this challenge :00)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

tiktok and tumblr stop stalking the ex victim of a stalker to send him photos of his stalker and re-traumatize him challenge

#also stop saying he's the one in the wrong and stalking his ex-girlfriend to harass her/traumatize her challenge#also also stop glorifying the show challenge#(99.9% of people fail this challenge :00)#bruh it was the most liked comment on a tik tok video saying that he purposely made her uglier than she was (she was an ugly fuck to start)#i don't fat shame normally but i will 100% fat shame that bitch to the point of body dysmorphia and hope she suffers horribly in the future#never the actress tho she was great#if i see ANYONE coming for the actress i'm throwing hands#also darrien i hope he steps on a lego and overdoses on his drugs#actually i wish both experience what it was like for donny all the fear all the pain all the trauma everything i hope they know the sufferi#anyway i just finished baby reindeer and holy SHIT i have never related to a character more since i first saw angel dust#fuck martha and darrien#there's a special place in hell for them#and when i die and go down to hell i'm going to make them wish they were with them six limbed devils#psa; THIS IS ABOUT REAL PEOPLE THEY'RE NOT CHARACTERS#end of my rant now this pissed me off with how people are so hyper focused on martha and everything about her that it makes it seem like sh#+e is the only good person here and the only victim because OF SOME SOPPY FUCKING DUMB STORY AT THE END WHERE HER PARENTS FOUGHT FUCK HER N#+O ONE LOVES YOU AND I HOPE NO ONE EVER LOVES YOU TIK TOK SHE IS NOT THE VICTIM DONNY IS AND YOU ARE ALL TOO DUMB TO REALISE PAST YOUR HYPE#+R FEMENIST ALL MEN ARE EVIL BULLSHIT#*sigh*#i'm fine i swear#i'll delete this later maybe#if i remember it

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

January 1, 2025

Heather Cox Richardson

Jan 01, 2025

Twenty-five years ago today, Americans—along with the rest of the world—woke up to a new century date…and to the discovery that the years of work computer programmers had put in to stop what was known as the Y2K bug from crashing airplanes, shutting down hospitals, and making payments systems inoperable had worked.

When programmers began their work with the first wave of commercial computers in the 1960s, computer memory was expensive, so they used a two-digit format for dates, using just the years in the century, rather than using the four digits that would be necessary otherwise—78, for example, rather than 1978. This worked fine until the century changed.

As the turn of the twenty-first century approached, computer engineers realized that computers might interpret 00 as 1900 rather than 2000 or fail to recognize it at all, causing programs that, by then, handled routine maintenance, safety checks, transportation, finance, and so on, to fail. According to scholar Olivia Bosch, governments recognized that government services, as well as security and the law, could be disrupted by the glitch. They knew that the public must have confidence that world systems would survive, and the United States and the United Kingdom, where at the time computers were more widespread than they were elsewhere, emphasized transparency about how governments, companies, and programmers were handling the problem. They backed the World Bank and the United Nations in their work to help developing countries fix their own Y2K issues.

Meanwhile, people who were already worried about the coming of a new century began to fear that the end of the world was coming. In late 1996, evangelical Christian believers saw the Virgin Mary in the windows of an office building near Clearwater, Florida, and some thought the image was a sign of the end times. Leaders fed that fear, some appearing to hope that the secular government they hated would fall, some appreciating the profit to be made from their warnings. Popular televangelist Pat Robertson ran headlines like “The Year 2000—A Date with Disaster.”

Fears reached far beyond the evangelical community. Newspaper tabloids ran headlines that convinced some worried people to start stockpiling food and preparing for societal collapse: “JANUARY 1, 2000: THE DAY THE EARTH WILL STAND STILL!” one tabloid read. “ALL BANKS WILL FAIL. FOOD SUPPLIES WILL BE DEPLETED! ELECTRICITY WILL BE CUT OFF! THE STOCK MARKET WILL CRASH! VEHICLES USING COMPUTER CHIPS WILL STOP DEAD! TELEPHONES WILL CEASE TO FUNCTION! DOMINO EFFECT WILL CAUSE A WORLDWIDE DEPRESSION!”

In fact, the fix turned out to be simple—programmers developed updated systems that recognized a four-digit date—but implementing it meant that hardware and software had to be adjusted to become Y2K compliant, and they had to be ready by midnight on December 31, 1999. Technology teams worked for years, racing to meet the deadline at a cost that researchers estimate to have been $300–$600 billion. The head of the Federal Aviation Administration at the time, Jane Garvey, told NPR in 1998 that the air traffic control system had twenty-three million lines of code that had to be fixed.

President Bill Clinton’s 1999 budget had described fixing the Y2K bug as “the single largest technology management challenge in history,” but on December 14 of that year, President Bill Clinton announced that according to the Office of Management and Budget, 99.9% of the government's mission-critical computer systems were ready for 2000. In May 1997, only 21% had been ready. “[W]e have done our job, we have met the deadline, and we have done it well below cost projections,” Clinton said.

Indeed, the fix worked. Despite the dark warnings, the programmers had done their job, and the clocks changed with little disruption. “2000,” the Wilmington, Delaware, News Journal’s headline read. “World rejoices; Y2K bug is quiet.”

Crises get a lot of attention, but the quiet work of fixing them gets less. And if that work ends the crisis that got all the attention, the success itself makes people think there was never a crisis to begin with. In the aftermath of the Y2K problem, people began to treat it as a joke, but as technology forecaster Paul Saffo emphasized, “The Y2K crisis didn’t happen precisely because people started preparing for it over a decade in advance. And the general public who was busy stocking up on supplies and stuff just didn’t have a sense that the programmers were on the job.”

As of midnight last night, a five-year contract ended that had allowed Russia to export natural gas to Europe by way of a pipeline running through Ukraine. Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelensky warned that he would not renew the contract, which permitted more than $6 billion a year to flow to cash-strapped Russia. European governments said they had plenty of time to prepare and that they have found alternative sources to meet the needs of their people.

Today, President Joe Biden issued a statement marking the day that the new, lower cap on seniors’ out-of-pocket spending on prescription drugs goes into effect. The Inflation Reduction Act, negotiated over two years and passed with Democratic votes alone, enabled the government to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies over drug prices and phased in out-of-pocket spending caps for seniors. In 2024 the cap was $3,400; it’s now $2,000.

As we launch ourselves into 2025, one of the key issues of the new year will be whether Americans care that the U.S. government does the hard, slow work of governing and, if it does, who benefits.

Happy New Year, everyone.

LETTERS FROM AN AMERICAN

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

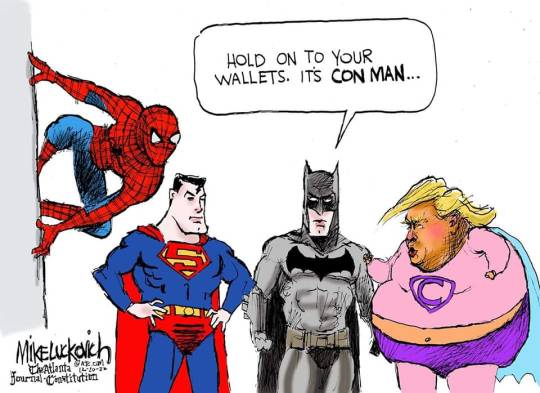

#Con Man#Mike Luckovich#Letters From An American#heather cox richardson#history#American History#Y2K#do your job#the work of government#Inflation Reduction Act#technology management#the hard slow work of governing

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Heather Cox Richardson 1.1.25

Heather Cox Richardson 1.1.25

Twenty-five years ago today, Americans—along with the rest of the world—woke up to a new century date…and to the discovery that the years of work computer programmers had put in to stop what was known as the Y2K bug from crashing airplanes, shutting down hospitals, and making payments systems inoperable had worked.

When programmers began their work with the first wave of commercial computers in the 1960s, computer memory was expensive, so they used a two-digit format for dates, using just the years in the century, rather than using the four digits that would be necessary otherwise—78, for example, rather than 1978. This worked fine until the century changed.

As the turn of the twenty-first century approached, computer engineers realized that computers might interpret 00 as 1900 rather than 2000 or fail to recognize it at all, causing programs that, by then, handled routine maintenance, safety checks, transportation, finance, and so on, to fail. According to scholar Olivia Bosch, governments recognized that government services, as well as security and the law, could be disrupted by the glitch. They knew that the public must have confidence that world systems would survive, and the United States and the United Kingdom, where at the time computers were more widespread than they were elsewhere, emphasized transparency about how governments, companies, and programmers were handling the problem. They backed the World Bank and the United Nations in their work to help developing countries fix their own Y2K issues.

Meanwhile, people who were already worried about the coming of a new century began to fear that the end of the world was coming. In late 1996, evangelical Christian believers saw the Virgin Mary in the windows of an office building near Clearwater, Florida, and some thought the image was a sign of the end times. Leaders fed that fear, some appearing to hope that the secular government they hated would fall, some appreciating the profit to be made from their warnings. Popular televangelist Pat Robertson ran headlines like “The Year 2000—A Date with Disaster.”

Fears reached far beyond the evangelical community. Newspaper tabloids ran headlines that convinced some worried people to start stockpiling food and preparing for societal collapse: “JANUARY 1, 2000: THE DAY THE EARTH WILL STAND STILL!” one tabloid read. “ALL BANKS WILL FAIL. FOOD SUPPLIES WILL BE DEPLETED! ELECTRICITY WILL BE CUT OFF! THE STOCK MARKET WILL CRASH! VEHICLES USING COMPUTER CHIPS WILL STOP DEAD! TELEPHONES WILL CEASE TO FUNCTION! DOMINO EFFECT WILL CAUSE A WORLDWIDE DEPRESSION!”

In fact, the fix turned out to be simple—programmers developed updated systems that recognized a four-digit date—but implementing it meant that hardware and software had to be adjusted to become Y2K compliant, and they had to be ready by midnight on December 31, 1999. Technology teams worked for years, racing to meet the deadline at a cost that researchers estimate to have been $300–$600 billion. The head of the Federal Aviation Administration at the time, Jane Garvey, told NPR in 1998 that the air traffic control system had twenty-three million lines of code that had to be fixed.

President Bill Clinton’s 1999 budget had described fixing the Y2K bug as “the single largest technology management challenge in history,” but on December 14 of that year, President Bill Clinton announced that according to the Office of Management and Budget, 99.9% of the government's mission-critical computer systems were ready for 2000. In May 1997, only 21% had been ready. “[W]e have done our job, we have met the deadline, and we have done it well below cost projections,” Clinton said.

Indeed, the fix worked. Despite the dark warnings, the programmers had done their job, and the clocks changed with little disruption. “2000,” the Wilmington, Delaware, News Journal’s headline read. “World rejoices; Y2K bug is quiet.”

Crises get a lot of attention, but the quiet work of fixing them gets less. And if that work ends the crisis that got all the attention, the success itself makes people think there was never a crisis to begin with. In the aftermath of the Y2K problem, people began to treat it as a joke, but as technology forecaster Paul Saffo emphasized, “The Y2K crisis didn’t happen precisely because people started preparing for it over a decade in advance. And the general public who was busy stocking up on supplies and stuff just didn’t have a sense that the programmers were on the job.”

As of midnight last night, a five-year contract ended that had allowed Russia to export natural gas to Europe by way of a pipeline running through Ukraine. Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelensky warned that he would not renew the contract, which permitted more than $6 billion a year to flow to cash-strapped Russia. European governments said they had plenty of time to prepare and that they have found alternative sources to meet the needs of their people.

Today, President Joe Biden issued a statement marking the day that the new, lower cap on seniors’ out-of-pocket spending on prescription drugs goes into effect. The Inflation Reduction Act, negotiated over two years and passed with Democratic votes alone, enabled the government to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies over drug prices and phased in out-of-pocket spending caps for seniors. In 2024 the cap was $3,400; it’s now $2,000.

As we launch ourselves into 2025, one of the key issues of the new year will be whether Americans care that the U.S. government does the hard, slow work of governing and, if it does, who benefits.

Happy New Year, everyone.

1 note

·

View note

Text

January 1, 2025

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON

JAN 2

Twenty-five years ago today, Americans—along with the rest of the world—woke up to a new century date…and to the discovery that the years of work computer programmers had put in to stop what was known as the Y2K bug from crashing airplanes, shutting down hospitals, and making payments systems inoperable had worked.

When programmers began their work with the first wave of commercial computers in the 1960s, computer memory was expensive, so they used a two-digit format for dates, using just the years in the century, rather than using the four digits that would be necessary otherwise—78, for example, rather than 1978. This worked fine until the century changed.

As the turn of the twenty-first century approached, computer engineers realized that computers might interpret 00 as 1900 rather than 2000 or fail to recognize it at all, causing programs that, by then, handled routine maintenance, safety checks, transportation, finance, and so on, to fail. According to scholar Olivia Bosch, governments recognized that government services, as well as security and the law, could be disrupted by the glitch. They knew that the public must have confidence that world systems would survive, and the United States and the United Kingdom, where at the time computers were more widespread than they were elsewhere, emphasized transparency about how governments, companies, and programmers were handling the problem. They backed the World Bank and the United Nations in their work to help developing countries fix their own Y2K issues.

Meanwhile, people who were already worried about the coming of a new century began to fear that the end of the world was coming. In late 1996, evangelical Christian believers saw the Virgin Mary in the windows of an office building near Clearwater, Florida, and some thought the image was a sign of the end times. Leaders fed that fear, some appearing to hope that the secular government they hated would fall, some appreciating the profit to be made from their warnings. Popular televangelist Pat Robertson ran headlines like “The Year 2000—A Date with Disaster.”

Fears reached far beyond the evangelical community. Newspaper tabloids ran headlines that convinced some worried people to start stockpiling food and preparing for societal collapse: “JANUARY 1, 2000: THE DAY THE EARTH WILL STAND STILL!” one tabloid read. “ALL BANKS WILL FAIL. FOOD SUPPLIES WILL BE DEPLETED! ELECTRICITY WILL BE CUT OFF! THE STOCK MARKET WILL CRASH! VEHICLES USING COMPUTER CHIPS WILL STOP DEAD! TELEPHONES WILL CEASE TO FUNCTION! DOMINO EFFECT WILL CAUSE A WORLDWIDE DEPRESSION!”

In fact, the fix turned out to be simple—programmers developed updated systems that recognized a four-digit date—but implementing it meant that hardware and software had to be adjusted to become Y2K compliant, and they had to be ready by midnight on December 31, 1999. Technology teams worked for years, racing to meet the deadline at a cost that researchers estimate to have been $300–$600 billion. The head of the Federal Aviation Administration at the time, Jane Garvey, told NPR in 1998 that the air traffic control system had twenty-three million lines of code that had to be fixed.

President Bill Clinton’s 1999 budget had described fixing the Y2K bug as “the single largest technology management challenge in history,” but on December 14 of that year, President Bill Clinton announced that according to the Office of Management and Budget, 99.9% of the government's mission-critical computer systems were ready for 2000. In May 1997, only 21% had been ready. “[W]e have done our job, we have met the deadline, and we have done it well below cost projections,” Clinton said.

Indeed, the fix worked. Despite the dark warnings, the programmers had done their job, and the clocks changed with little disruption. “2000,” the Wilmington, Delaware, News Journal’s headline read. “World rejoices; Y2K bug is quiet.”

Crises get a lot of attention, but the quiet work of fixing them gets less. And if that work ends the crisis that got all the attention, the success itself makes people think there was never a crisis to begin with. In the aftermath of the Y2K problem, people began to treat it as a joke, but as technology forecaster Paul Saffo emphasized, “The Y2K crisis didn’t happen precisely because people started preparing for it over a decade in advance. And the general public who was busy stocking up on supplies and stuff just didn’t have a sense that the programmers were on the job.”

As of midnight last night, a five-year contract ended that had allowed Russia to export natural gas to Europe by way of a pipeline running through Ukraine. Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelensky warned that he would not renew the contract, which permitted more than $6 billion a year to flow to cash-strapped Russia. European governments said they had plenty of time to prepare and that they have found alternative sources to meet the needs of their people.

Today, President Joe Biden issued a statement marking the day that the new, lower cap on seniors’ out-of-pocket spending on prescription drugs goes into effect. The Inflation Reduction Act, negotiated over two years and passed with Democratic votes alone, enabled the government to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies over drug prices and phased in out-of-pocket spending caps for seniors. In 2024 the cap was $3,400; it’s now $2,000.

As we launch ourselves into 2025, one of the key issues of the new year will be whether Americans care that the U.S. government does the hard, slow work of governing and, if it does, who benefits.

Happy New Year, everyone.

—

1 note

·

View note