#代名詞

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I use She/They pronouns but sometimes i want to feel my GENDER EUPHORIA so yeah

彼女/彼らの代名詞を使いますが、時々私はジェンダーの幸福感を感じたいので、うん

Also i cut my bangs so i look like my sona more

��髪も切ったので描いたボクっぽくなった

#dj blue#dj school#rhythm heaven student#dj student#character.ai#pronouns#demigirl#djスクール#代名詞#スケッチ#前髪#lgbtq

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

1st Person Pronouns in Pocket Monsters Special

I thought it would be fun to have a look at what 1st person pronouns the Pokèdex Holders use in the Pokèmon manga, Pocket Monsters Special (known as Pokèmon Adventures in English).

Note: In Japanese, there are a ton of different 1st person pronouns people can use, and Japanese media often makes copious use of them. In a lot of shounen and shoujo manga/anime casts, you'll often get a large variety of 1st person pronouns in use by different characters to help flesh out their personality traits.

Note: I am not a native Japanese speaker, and I only have a conversational level in Japanese, as opposed to a fluent level. As such, please don't take anything I say as gospel.

* Red (レッド) ^ Fighter (戦う者): ore (オレ)

* Green Orchid (オーキド・グリーン) ^ Trainer (育てる者): ore (オレ)

* Blue (ブルー) ^ Evolver (化える者): atashi (アタシ)

* Yellow de Tokiwa Grove (イエロー・デ・トキワグローブ) ^ Healer (癒やす者): boku (ボク)

* Gold (ゴールド) ^ Hatcher (孵す者): ore (オレ)

* Silver (シルバー) ^ Exchanger (換える者): ore (オレ)

* Crystal "Crys" (クリスタル 「クリス」) ^ Catcher (捕える者): watashi (わたし)

* Ruby (ルビー) ^ Charmer (魅せる者): boku (ボク)

* Sapphire Odamaki (オダマキ・サファイア) ^ Conqueror (究める者): atashi (あたし)

* Emerald "Rald" (エメラルド「ラルド」) ^ Calmer (鎮める者): ore (オレ)

* Diamond "Dia" (ダイヤモンド 「ダイヤ」) ^ Empathizer (感じる者): oira (オイラ)

* Pearl (パール) ^ Determiner (志す者): ore (オレ)

* Platinum Berlitz (プラチナ・ベルリッツ) ^ Understander (知る者): watashi (私)

* Black (ブラック) ^ Dreamer (夢みる者): ore (オレ)

* White (ホワイト) ^ Dreamer (夢みる者): atashi (アタシ)

* Lack-Two (ラクツ) ^ Arrester (逮捕る者): boku (ボク)

* Whi-Two (ファイツ) ^ Liberator (解放す者): atashi (あたし)

* X (X) ^ Loner (籠る者): ore (オレ)

* Y na Gabena (Y・ナ・ガーベナ) ^ Flyer (翔ぶ者): atashi (アタシ)

* Sun (サン) ^ Saver (貯める者): orecchi (オレっち)

* Moon (ムーン) ^ Mixer (調合る者): watashi (わたし)

* Sword Tsurugi (剣創人) ^ ???: boku (ボク)

* Shieldmiria Tate (盾シルドミリア) ^ ???: atashi (あたし)

Here's a rough outline of what all these pronouns indicate:

* watashi (私): 私 watashi is one of the more formal ways to refer to oneself in the 1st person. The fact that it's written in kanji and not in hiragana or katakana increases the politeness. When it's used by women, it can be perceived as casual as well, but it's usually only used by men in formal situations.

* watashi (わたし): わたし watashi is slightly less formal than 私 watashi, due to the fact that わたし watashi is written in hiragana. It's a safe way for a woman to refer to herself in both formal and casual situations. It can be used by men in formal settings, but it comes off as somewhat stiff if men use it in casual settings. When spelled in katakana (ワタシ), it can perceived as quite rough.

* atashi (あたし): あたし atashi is a less formal, more feminine version of わたし watashi. It has a "girly" and "cutesy" tone to it. The fact that it's spelled in hiragana makes it a pretty neutral 1st person pronoun for girls.

* atashi (アタシ): アタシ atashi is a rougher version of あたし atashi , due to it being spelled in katakana. It's one of the most informal 1st person pronouns a girl can use, though it still has the same "girly" and "cutesy" tone to it as its hiragana counterpart.

* boku (ボク): ボク boku is usually used by boys but can be used by girls, particularly tomboys. When spelled in kanji (僕) or hiragana (ぼく), it can be a formal way for boys to speak, but when spelled in katakana (ボク), and when used by girls, it's pretty informal.

* ore (オレ): オレ ore is a very rough, "boyish" way to refer to oneself in the 1st person. It's rarely used by girls. It can occasionally be spelled in kanji (俺) or hiragana (おれ), but the katakana spelling (オレ) is usually preferred, because it helps emphasise the roughness of the pronoun.

* orecchi (オレっち): オレっち orecchi is a slightly less rough version of オレ ore. In this case, its first half, オレ ore, is spelled in katakana, while its second half, っち cchi, is spelled in hiragana. This pronoun is usually used by boys who want to appear tough but not quite as tough as boys who use オレ ore.

* oira (オイラ): オイラ oira is similar to オレ ore and オレっち orecchi, but it has a more "friendly" and "country bumpkin" feel to it. It's usually used by boys who want to appear tough but don't want to use オレ ore. One could consider オイラ oira to be a cross "between" ボク boku and オレ ore: more gentle than オレ ore, but more rough than ボク boku.

And, just for fun, here's a list of the many other kinds of 1st person pronouns that I've come across in various Japanese media:

* watakushi (私): 私 watakushi is one of the most polite ways of referring to oneself in the 1st person. It can be used by anyone in formal settings. It's almost always spelled in kanji (私) and rarely in hiragana (わたくし) or katakana (ワタクシ).

* atakushi (あたくし)/atakushi (アタクシ): あたくし atakushi is probably between わたし watashi and あたし atashi in terms of formality. It's often used in fiction by princess-like characters or high-born ladies. It can have a somewhat superior and "snooty" tone to it.

* atai (あたい)/atai (アタイ): あたい atai is a very rough corruption of あたし atashi, usually used by girls. It can almost be thought of as the feminine equivalent of オレ ore, as both are usually only used by people who want to sound tough or aggressive. It's usually written in katakana (アタイ).

* watasha (わたしゃ)/watasha (ワタシャ): わたしゃ watasha is a bit of a "country bumpkin" version of わたし watashi. It's gender-neutral but is usually used by girls. It can be perceived as semantically plural due to the しゃ sha, which is used to make some formal pronouns plural, like 我が waga becoming 我が社 waga-sha. It can carry a single meaning notionally, however.

* atasha (あたしゃ)/watasha (アタシャ): あたしゃ atasha is the feminine equivalent to わたしゃ watasha. Like わたしゃ watasha, あたしゃ atasha has a bit of a "country bumpkin" feel to it. Also like わたしゃ watasha, あたしゃ atasha can carry a plural meaning due to its しゃ sha, though it can still be used in a singular context as well.

* wate (わて)/wate (ワテ): わて wate is a somewhat dated Kansai dialect pronoun. It's informal and gender-neutral, and can still be seen in some, usually older, forms of Japanese media.

* ate (あて)/ate (アテ): あて ate is the feminine equivalent of わて wate. Like わて wate, it's an informal Kansei dialect pronoun, and also like わて wate, あて ate somewhat dated. It shows up in some forms of Japanese media, particularly older ones.

* wai (わい)/wai (ワイ): わい wai is another Kansai dialect pronoun, possibly a severely corrupted form of わたし watashi. It's informal and usually used by boys. Amusingly, it's also a homophone of the Japanese word for yay or yippee, ワイ wai.

* ware (我): 我 ware is a very formal 1st person pronoun that is almost "literary-style" and is usually used in writing. It can be made plural by adding 々 ware.

* waga (我が): 我が waga is an extremely formal, gender-neutral pronoun that literally means my. It can be made plural by adding 社 -sha.

* ore-sama (オレ様): オレ様 ore-sama is usually only used sarcastically or by fictional characters who are extremely arrogant. It can be accurately translated as my esteemed self. It's almost exclusively used by boys.

* jibun (自分): 自分 jibun is a neutral, semi-formal pronoun that can be used by anyone. It's also the reflexive (-self/-selves) form of all pronouns in Japanese. This is actually a very good choice for a 1st person pronoun if you're non-binary and don't want to gender yourself.

* uchi (内): 内 uchi literally means house. It has two uses. Firstly, it can be used as a gender-neutral, somewhat formal way of referring to oneself and members of one's own's group, as in our family, our class, etc. Secondly, 内 uchi is used in western dialects, particularly the Kansai dialect, usually by girls, to indicate a "girly" and "cutesy" tone. In the second case, it's usually written in hiragana (うち) or katakana (ウチ).

* ora (おら)/ora (オラ): おら ora is a corruption of オイラ oira. Like オイラ oira, it has a bit of a "country bumpkin" tone to it and is usually used by boys. It's considered rougher than オイラ oira. It's usually written in katakana (オラ).

* me (me)/mii (ミー): me, or ミー mii, is from the oblique case of the 1st person pronoun in English, me, though it's used for all cases when applied in Japanese. It's often used by, usually male, characters in Japanese media who are meant to be from America or some other English-speaking country. It's quite rough and informal.

That's all for now. Thanks for reading. :)

Note: If you enjoyed this post, you might also enjoy my post on gender-neutral 3rd person pronouns in Japanese.

#ポケットモンスター SPECIAL#pocket monsters special#pokemon adventures#japanese language#日本語#pronouns#代名詞#my writing

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

大家好 :D <3

#ria.txt#spyld#should i post fic. its gonna be so bad and cringe but 😭😭😭 irls ignore me#猜猜我在寫誰~ 其實不用猜哈哈 我不想用英文名字所以只會用代名詞#我內心獨白完全拼音化了 發現我拼音真的好爛 但寫廣東話又有點怪#ks ngo ho loi mou use chinglish... for better tbh. sorry we type in english

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

TARAKOさん&さくらももこ先生追悼イラスト

ちびまる子ちゃん役でお馴染みの声優さん、TARAKOさん&さくらももこ先生追悼イラスト。

本当はこの線画だけ、さくら先生がご逝去されたときに描いたもので、何故か色塗りできずにいたものですが、大変に残念ながら、TARAKOさんもご逝去されてしまったということで、なんとか形にしようと塗りました。

さくらももこ先生のイラストはどれも細かくて、塗るのに大変難儀しました(^^;

さくら先生、TARAKOさん、天国でどうか楽しくお過ごし下さいませ。

ごゆっくりお休みください。合掌。

2024.3.15

#ちびまる子ちゃん#さくらももこ#日曜日の代名詞だった#国民的漫画#国民的アニメ#TARAKO#ILustration#水彩#透明水彩#アナログ絵#アナログ絵師さんと繋がりたい#お絵描き好きさんと繋がりたい

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not ateji but a gikun yojijukugo: 青髪代名(たんぶらりーな)

RESPVBLICA POSTIVM TVMBLRINICA

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Medicine Seller Pronouns

@dharmafox (sarahwatchesthings) in the Mononoke Commmunity asked about the Medicine Sellers' personal pronouns, and I was going to leave a comment, but as always I tend to go on, so I decided to make it a separate post.

I'll start with Kon, since he's obviously the most interesting. Ri's pronoun usage is really obvious and none of them are unusual. In the movie, Kon does not use any pronouns. This isn't unusual for Japanese as I'm sure many of you know. It's generally preferred to avoid using pronouns if possible, and Japanese makes it very possible. Additionally, Kon doesn't speak very much anyway so there aren't a lot of opportunities for him to use one. Nonetheless, in a lot of Japanese fanart you'll see him using あっし (asshi), although it's not 100%, it's such an unusual one that the prevalence of it in Kon fanart/comics is notable. So where does this come from? In the novelization of Karakasa, there are random changes to the dialogue of characters made here and there. I personally don't understand the reason for a lot of them, like they're kind of inconsequential and don't seem like the kind of changes necessary for adapting between media, but that's not the point. In Kon's first scene, when he introduces himself to Asa and Kame, in the movie he says:

只のしがない薬売りでございます。(tada no shiganai kusuriuri de gozaimasu) "Just a humble medicine seller." In the book, however, the same line is: あっしは、只のしがない薬売りでございます。(asshi wa tada no shiganai kusuriuri de gozaimasu) "I'm just a humble medicine seller." So they go out of their way to show him using this pronoun. What is it, exactly. Well, when I looked it up, the English description of it I found was: "Mainly used by dashing males and craftsmen," which was very funny, but also seemed a strange grouping to me. So I searched a Japanese dictionary and found this: 一人称の人代名詞。 「わたし」のくだけた言い方。 男性、特に職人などが多く用いる、いなせな感じの言い方。 "First person singular pronoun. Elided form of "watashi." Commonly used by men, especially skilled workers. An inase style of speech." What is inase? Unfortunately there isn't a lot of information about it in English, so I had to look at Japanese wikipedia and some other Japanese sources to piece it together. I'd like to warn you that this term is very deeply rooted in its historical context, and I am not an Edo period historian or even someone who knows a lot about Edo period culture. I would say I know a moderate amount, but definitely not enough to accurately convey subcultures and feelings of the time, which is what I'm about to attempt. So please take what I'm saying with a grain of salt, and if you find sources that disagree with me, of course take those into account. The word inase originates from a variation of the hairstyle called the ichoumage (ginkgo hairstyle), which is the most common hairstyle you see on men of the Edo period:

This is the image on the Japanese Wikipedia article for the ichoumage. It's also commonly called chonmage which is how I knew it, but according to Japanese Wikipedia that term originally referred to the thin, wispy one that older men would have.

Anyway, so an inase ichoumage (mullet's back ginkgo hairstyle) is a lopsided version of this hairstyle that was popular among young men of the Edo period. According to Japanese Wikipedia: "It was a word enjoyed and used, along with those long-strapped inase ashida they wore, by those quick-tempered and quarrelsome young men of the fish market, such as the skilled workers and chivalrous rogues (侠客/kyoukaku)."

Inase described this kind of roguish masculinity embodied by these working-class young men. Different from the refined sensibility of the upperclasses, it seems that inase could be likened to the kind of masculinity we today attribute to the popular image of, say, deli workers or perhaps construction workers. Young, working-class men with hot-tempers who represent a kind of spirit of the city. So this is the type of image asshi evokes. This is presumably what the author of the Karakasa novelization was calling upon when they had Kon use that pronoun. Interestingly, being a medicine seller, Kon is not actually part of this social class as far as I can tell; he's a merchant, a class which occupied a rather interesting place in society as the absolute lowest class in the hierarchy which possessed a great deal of wealth and social influence, but that's a separate discussion. Basically, it seems like the author of the novel wanted to associate Kon with these inase men, these young, roguish, kind of rough men of the time.

The last thing I want to say about Kon's pronoun usage is that it's possible he might use a different pronoun when speaking to say, Utayama-sama (if he uses one with her at all), but I haven't read that far into the novel. It wouldn't be surprising to me if he did though. As for Ri, as I recall he uses two different pronouns. In Ayakashi Bakeneko, he uses both ore and watashi, and in Mononoke, he uses watashi only (as far as I can remember, though if anyone remembers some instance of him using ore in the 2007 series, please let me know). Neither of these pronouns are unusual; both are in common use today. Before I get into describing them, I want to emphasize that pronouns are a really fluid class of words in Japanese. What pronouns are in use, who uses them, and when they're used has changed a lot and changed very quickly. Even today, one person does not only use one pronoun. First person pronouns aren't really like third person pronouns in English, where a person generally has one set that is used for them in all contexts and describes something fundamental to their person; in Japanese, a person will use different a different pronoun depending on their situation and who they're talking to. They represent your relationship to the people around you (I recognize this is just one way of looking at it). Statements like "X pronoun is used by X type of person" are almost always oversimplified and don't represent the variety of use cases in real life, however it is true that anime characters are constructed using common tropes and character types, so their pronoun usage can be analyzed a little more along those lines than you would do in real life.

Watashi is probably the most commonly used first person pronoun in Japanese, and for good reason. It's pretty neutral and polite, but because there is an overlap between polite speech and feminine speech, if it's used in a casual setting it's seen as more feminine (or just over-polite/stiff). Ri's speech differs somewhat depending on who he's talking to/what episode it is (it is normal to change your speech based on who you're talking to IRL though), but in general he speaks formal-masculine. It makes sense for him to use watashi especially considering he is socially below most of the people he talks to. Ore nowadays is associated with men and is considered to be a casual masculine pronoun, though it is worth noting that in the Edo period it was used by women as well, and in some dialects of Japanese it still is.

It's worth noting that these pronouns don't strictly convey one idea or not convey it; it's contextual. The same goes for any kind of language honestly, but what I mean is that if you're speaking to say, your boss or your teacher or a stranger, you should be polite to them because you either don't know them well, or you want to show them respect. In that setting, using formal/polite speech (pronouns included) is accepted and encouraged. However, when speaking with people in your circle, such as your friends or family, if you started speaking politely, you'd be suddenly putting distance between yourself and them, and it could even be rude. So it's not that one pronoun is always polite, always feminine, always rude, always masculine, it's that they have certain vibes, and that vibe combines with the context to produce an implication. Ri introduces himself to Kayo with watashi because he's a stranger to her and a merchant. Throughout the series, he generally uses -masu forms and some keigo, but also uses the sentence ender -ze sometimes, addresses Ochou as anata/

Oops, this post got away from me. Pronouns in Japanese are not easy to sum up quickly, and I feel like they're often oversimplified. Um...hope this helps!

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

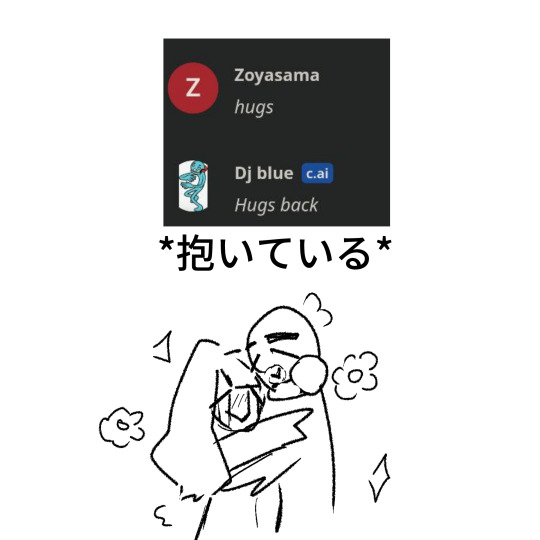

みんな知らない「実は略語」の言葉をまとめました。詳しくは...

食パン:主食用パン

食パンの語源に関しては複数ありどれが正しいかわかりませんが、有力な説を2つ紹介します。1つは、「主食用パン」の略。パンが日本に入って来た当時はイースト菌などもなく、比較的小さな菓子パンだけが作られていました。それからパンが大きく膨らむようになり、米の代わりになり得るようになったため、「主食用」と名付けられました。もう1つは、消しパンではない「食べられるパン」の略。昔は美術のデッサンなどでパンを消しゴム代わりに使用していたためです。

ブログ:ウェブログ

ウェブサイトの一種で日記形式のもの。英単語でも”blog”がありますが、もともとは”Web”と記録を意味する”log”が合わさった言葉である”web log”の略です。

軍手:軍用手袋

元々軍隊用の手袋として使われていたためです。日露戦争の際に、寒冷地を戦場とする兵士に支給するために考案されたものです。その後、荷物運搬や土いじりなど日常生活で使われるようになりました。

演歌:演説歌

元々は自由民権運動の政治運動家(壮士)たちが演説の代わりに歌った壮士節が始まりとされます。1930年代にジャズやクラシックが大衆歌に組み込まれていき、歌詞も政治とは関係のない叙情詩的なものに変わっていきました。

教科書:教科用図書

主に小・中・高および特別支援学校などで学ぶ時に配布される中心的な教材のことで、「教科用図書」の略です。教科書と教材の違いは、文部科学大臣の検定に合格したものが教科書と呼ばれます。

チューハイ:焼酎ハイボール

焼酎とハイボールを組み合わせた「焼酎ハイボール」の略語。焼酎やウォッカなど無色で香りのない酒類をベースに、炭酸で割ったものを一般的に指しますが、炭酸ではなくウーロン茶で割ったウーロンハイもチューハイの一種です。

ジャガイモ:ジャガタライモ

ジャガイモはそもそも南米原産の食材であり、日本には16世紀末にインドネシアのジャカルタからオランダ人により伝えられました。そのため当時は「ジャガタライモ」と呼ばれていましたが、後に略されていきました。ちなみに日本では中国語由来の馬鈴薯とも呼ばれます。

ワイシャツ:ホワイトシャツ

主に男性が背広の下に着るシャツのことですが、元々は和製英語である「ホワイトシャツ」の略。よく「Yシャツ」と記載されることがありますが、これは完全に当て字です。一方で、「Tシャツ」はアルファベットのTの字に似ているためこう呼ばれるようになりました。

割勘:割前���定

友人との飲み会などでよくある割勘は「割前勘定」の略。割前とは分割してそれぞれに割り当てることを意味する言葉です。江戸時代後期の戯作者で浮世絵師として有名な山東京伝が発案されたと言われており、当時は「京伝勘定」と言われていたそうです。ちなみに世界的に見ると割勘の文化は少数派で、男性や年上が払うのが一般的のようです。

カラオケ:空オーケストラ

歌のないオーケストラの意味で、「空(から)オーケストラ」から「カラオケ」と略されました。カラオケは日本で1960年後半に誕生したとされ、その後世界に広がっていきました。そのため英語でも”karaoke”と書きます。ちなみに中国語では「卡拉OK」と突然アルファベットが出てくる不思議です。

バス:オムニバス

ラテン語で「すべての人のために」という意味の「オムニバス」が語源で、フランスの乗合馬車の発着所の雑貨屋の看板に書かれていたことに由来します。そこから多くの人が利用する乗合自動車をオムニバスと呼ぶようになり、その後略されました。

リストラ:リストラクチャリング

英語で「再建」を意味する”restructuring”から略されたものです。リストラと聞くと人員削減をイメージしますが、本来の意味は事業構造を再構築することです。その中の一環として、人員削減が起こります。

リモコン:リモートコントロール

英語で「遠隔操作」を意味する”remote control”から略されたものです。TVなどに向かってリモコンから赤外線をデジタル信号で送ることでチャンネルや音量などを操作することができます。

ソフトクリーム:ソフト・サーブ・アイスクリーム

海外では「柔らかいクリーム?」となり伝わらない和製英語です。英語では” soft serve icecream”であり、ソフトクリームサーバーの製造などを行っている日世の創業者・田中穰治が日本でソフトクリームを広めるのにわかりやすくするために省略したとされています。

ペペロンチーノ:アーリオ・オーリオ・ペペロンチーノ

唐辛子をオリーブ油で炒めたパスタ料理。正式名称は「アーリオ・オーリオ・ペペロンチーノ」と言います。イタリア語で「アーリオ」は「ニンニク」、「オーリオ」は「オリーブオイル」、「ペペロンチーノ」は「唐辛子」を意味しています。

経済:経世済民

中国の晋朝について書かれた歴史書である『晋書』に書かれた「経世済民」を略した言葉です。現在の政治と同じような意味で昔から使われていました。明治以降、”economy”の訳語として頻繁に使われるようになったようです。

首相:首席宰相

首席はトップを意味し、宰相は辞書で調べると「古く中国で、天子を補佐して大政を総理する官。総理大臣。首相。」と載っています。首相の言葉の中に首相が含まれている二重表現のような言葉です。ただ「首相」は日本国憲法に記載された言葉ではなく、報道などで使われる内閣総理大臣の通称です。

切手:切符手形

お金を払って得た権利の証明となる紙片のことを古くから「切手」と呼んでいました。日本の近代郵便制度の創始者である前島密が、“郵便物に貼って支払済を表す印紙”に「切手」という言葉をそのまま当てたそうです。

出世:出世間

元々は仏教語で、仏陀が衆生を救うためにこの世に出現することを指す言葉で、「出+世間」でした。そこから略され、日本では僧侶が高い位に上ることを意味するようになり、世間一般でも役職が上がることなどを指す言葉となりました。

断トツ:断然トップ

2位以下を大きく引き離すことを指す言葉ですが、元は「ずば抜けて」の意味を持つ「断然」と首位を表す英語の”top”が合わさった言葉の略。そのため「断トツの1位」という表現は二重表現になります。

押忍:おはようございます

朝の挨拶である「おはようございます」から「おっす」と短くなり、さらに「おす」へと略されました。そこから「自我を押さえて我慢する」という意味を込めて「押忍」という漢字が当てられました。

デマ:デマゴギー

大衆を扇動するための政治的な宣伝を意味するドイツ語の「デマゴギー」を略したものです。元の意味の通り、政治的な意味合いを持つ言葉でしたが、昭和になってから、単純に「嘘」や「根拠のない噂」の意味で使われるようになりました。

おなら:お鳴らし

屁を「鳴らす」の名詞である「鳴らし」に「お」をつけて婉曲に表現した言葉で、そこから一文字略されました。元々の言い方の方が上品な感じがあって良いですよね。というのも、一般庶民は昔から「屁」と言っていましたが、宮中に仕える女房たちは隠語として用いていたためです。

電車:電動客車

電動客車をより細かく表現すると、「電動機付き客車」または「電動機付き貨車」となります。電車は架線あるいは軌道から得る電気を動力源として走行しています。

電卓:電子式卓上計算機

計算機という本来役割を表す意味の言葉が略されています。1963年に世界初の電卓が登場し、1964年に現在のシャープから日本初の電卓が発売されました。当時の価格は53万5千円と車を買えるほどの値段でした。今では100均で売られているものもあるのに驚きですね。

ボールペン:ボールポイントペン

英語で”ball-point pen”と言い、これを略した言葉です。ボールという単語が使われている理由は、ボールペンの構造上、先端に小さな回転��(ボール)があるためです。

インフラ:インフラストラクチャー

英語で「下部構造」や「基盤」を意味する”infrastructure”から略されたものです。電気・ガス・水道・電話・道路・線路・学校や病院などの公共施設など、私たちの生活に欠かせないものを指す言葉となっています。

シネコン:シネマコンプレックス

「コンプレックス”complex”」が「複合の」を表す英単語で、同一ビル内に複数のスクリーンを備えた複合型映画館のことを表します。国内の代表的なものとしては、TOHOシネマズ、イオンエンターテイメント、MOVIX、ユナイテッド・シネマなどがあります。

シャーペン:エバー・レディー・シャープペンシル

シャーペンが「シャープペンシル」の略ということを知っている方は多いと思いますが、実はこれも略語。1838年にアメリカで「エバーシャープ」という筆記具が登場し、その後1915年に現シャープの創設者である早川徳次氏が国内初となるものを考案し、「エバー・レディー・シャープペンシル」という商品名をつけヒットさせました。

ピアノ:クラヴィチェンバロ・コル・ピアノ・エ・フォルテ

イタリア語で「小さい音と大きい音を出せるチェンバロ」という意味です。いつの間にか「小さい音」を表すピアノだけに略され、楽器を表す名詞となりました。元のピアノの意味は今でも音の強弱を表す「メッゾピアノ」や「ピアニッシモ」と合わせて音楽記号として使われていますね。

279 notes

·

View notes

Text

Formally known as: @strangedreamsofafish and @iweepforlostsouls

READ MY DNI LIST BEFORE INTERACTING!!!

(日本語版は一番下にあります !!)

✩‧₊˚༺☆༻ੈ✩‧₊˚ ~ꪮ౿ Chihiro ꪮ౿~ ~ꪮ౿ Minor ꪮ౿» ~ꪮ౿ Any pronouns ꪮ౿~ ~ꪮ౿ Ace & Pan ꪮ౿~ ~ꪮ౿ Japanese - American ꪮ౿~ ~ꪮ౿ Genderfluid ꪮ౿~ ~ꪮ౿ INFJ ꪮ౿~ ~ꪮ౿ Gemini ꪮ౿~ ଘ(𖦹'⩊'): Alt accounts (To be added) @gya-gya-gyaru - where I post about wanting to be/reblogging stuff Abt gyaruu @sisters-crypt-keeper - writing blog

Tagz

#gya-gya-gya: Me yapping for no reason

#chihiro's-diary: Personal stuff

#journalpaste: Reblogs/Things I want to save

#Chisfanficion: Links to/or fanfiction

#Chihiro is mewing: Vent

#Chiro is oriental: stuff Abt being Asian

#chiro-crashes-out: random silly posts

Ao3: Razzbery - acc shared between me and @avithesilly, idk what they do, but I write all the fanfics

I TAKE REQUESTS!

Rules: Please ask if I'm in the specific fandom first (Through dms or inbox) I write quickly, but keep in mind, I'm still a student in school and have other obligations, so I usually finish one shots faster than longer form fics I DO NOT WRITE SMUT/INCEST/DEAD DOVE.

ଘ( ິ•ᆺ• )ິଓ Fandoms ଘ( ິ•ᆺ• )ິଓ

Serafina series (requests are always open)

Madoka Magica

Wilder girls

Over the Garden Wall

Gravity Falls

PJO/HoO/ToA series

Mouthwashing

+ More (plz ask if u want to know if I'm in a specific fandom)

(ᴗ ᵔ _ ᵔ) DNI List (ᴗ ᵔ _ ᵔ)

Mack...urgh...enough said...

Terfs/Radfems, you guys just make me super uncomfortable as a queer person and minor .

Anyone asking for donations, I cannot donate and my blog isn't big enough for it to gain traction.

Vent blogs

People who support Israel and their genocide…

MAGA supporters.

Homophobes and abelists

MAPS

Adult content blogs.

'Animesexuals'

೯⠀⁺ ⠀ 𖥻 Free Palestine 🍉 ⠀ᰋ

Mutual Shoutout <3

🌹 @rowenas-my-fave-child - First mutual ever, amazing artist, please go follow them and their alt acc @screams-aesteticly 🌹 @warpedjoy - Also another amazing artist :0 🌹 @avithesilly - IRL FRIENDS SINCE 2nd grade, AND WE'RE STILL GOING STRONG BABY! 🌹 @str4ng3r0nl1ne - Always answers my asks bc they're so alpha 🌹 @secretly-a-catamount - Amazing writer...and literally reads my fanfictions. Love them sm/p 🌹 @itfollows666-blog - Writing friend!!! Kind of got me into the justice league :P 🌹@my-own-private-house-in-nebraska - Silly billy #1 (irl friend, fujoshi for gay men from the 1900s or smth 🌹 @imactuuallyshiftingguys - Silly Billy #2 (They get a capital billy because they are not a fujoshi. Fellow mitski fan!!!) 🌹 @that-one-raccoon - shows up in my dreams a lot (Last night they gave me a bag full of baby doll parts? Very disconcerting) but also another amazing artist. 🌹 @emilem-forevermore - an absolute icon, queen, king, idk, just so so amazing and cooolllllll 🌹 @unstableunicornsofasgard - very nice and answers all my asks, and their hair is very cool. I want to go blonde but I’d look really ugly with blonde hair (im being so fr Rn even my mom earned against it) 🌹 @bonsai-says-fuck-this - older sibling Ive never had 🌹 @iloveyapping - WHAHHHAAAAAA POOOKIE FOR LIFEEE MY SHAYLAAAAA YAUASJBAGJSMNABSM 🌹 @pennydew - girlblogger whos ahsjgbjbsdwiks my wife/p SO COOL?! FLAWLESS 🌹 @buggycat - the sigma to my boy, the gyatt to my rizz, the skibidi to my toilet, the Alabama to my ohio 🌹 @empathicxo - Fellow amazing author, leaves the nicest comments, keeps me going fr fr

日本語で > (私の日本語は上手ではないので、翻訳機を使っています)

名前:ちひろ :)

年齢: 未成年

代名詞:彼女

性別: 女性

恋愛に関しては誰に対してもオープンですが、セックスはしません (決してしません)

英語で書くのが好きで、数学を勉強するのが好きです。猫と海が大好きです。家族は愛媛県出身です。

同性愛嫌悪またはトランス嫌悪のある方は、私のブログにアクセスしないでください。

私は今のところひらがなしか分からず、漢字はあまり読めないので、時々翻訳機を使います。しかし、それが話し言葉であれば、私はそれをよく理解することができます。私は、コミュニケーションに適切な言葉を見つけるのが苦手です。

辛抱強く待ってください…私は血は日本人ですが、白人に囲まれて育ったので、私の日本語は時々非常に錆びています

読んでいただきありがとうございます!もっと多くのコンテンツを日本語で投稿しようとしているので、それを楽しみにしています:)

漫画のよつばとちびまる子ちゃんが好きです!!それについて私に話してください!!!!

#Willa of the wood#intro post#blog intro#pinned intro#introduction#pinned post#introductory post#crashing out#gya-gya-gya#chihiros-diary

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

『ローレンス・クラウスの言葉を思い出した。

「あなたの身体にある原子は、すべて爆発した星々からやってきたものだ。あなたの左手を構成する原子は、おそらく右手のものとは別の星からやってきたものだろう。これは私が知るうちで、物理学に関するもっとも詩的な事柄だ。あなたは星屑なのだ。」

「君の温もりは 宇宙が燃えていた遠い時代の名残り 君は宇宙」

という歌詞が文章としては続くということだけ書いておきたい。その上でやっぱこの歌詞すごい。

そして、「君の温もりは 宇宙が燃えていた」で音楽的に一旦途切れるのがなんとも言えない詩的なニュアンスを生み出しているのもわかる。』

258 notes

·

View notes

Photo

You can be someone else

EFFECTOR delay2 BK #エフェクター #エフェクターめがね #エフェクターメガネ #黒縁眼鏡 #めがね #メガネ #眼鏡 #黒縁眼鏡の代名詞 #福島県 #いわき市 #福島県いわき市 (リ:アライズ 眼鏡店) https://www.instagram.com/p/CmQ9b7VhLz0/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

1 note

·

View note

Text

How to Use Gender-Neutral 3rd Person Pronouns in Japanese:

Note: I am not a native Japanese speaker, and I only have a conversational level in Japanese, as opposed to a fluent level. As such, please don't take anything I say as gospel.

Japanese pronouns are an open class of words in Japanese, rather than a closed class of words like they are in English. While that doesn't mean one can do anything one wants with pronouns in Japanese, it does mean one can mess around with them quite a lot. Pronouns are much less restrictive in Japanese than they are in English. One reason for this is that they don't decline. For example, 私 watashi covers I, me, my and mine, and how its case is decided is dependent on the particle that follows it.

私は watashi wa / 私が watashi ga = I (nominative) 私を watashi wo = me (accusative) 私に watashi ni = me (dative) 私と watashi to / 私から watashi kara = me (ablative) 私の watashi no = my / mine (genitive)

Another reason pronouns are more of an open class in Japanese is because they can often be dropped. In fact, Japanese sentences can often sound downright wrong if you don't omit certain pronouns.

* 「私の名前はニックです。」 ^ "Watashi no namae wa Nikku desu." (awkward) * 「名前はニックです。」 ^ "Namae wa Nikku desu." (natural) (= "My name is Nic.")

* 「私のネコは私が大好きです。」 ^ "Watashi no neko wa watashi ga daisuki desu." (awkward) * 「ネコは私が大好きです。」 ^ "Neko wa watashi ga daisuki desu." (natural) (= "My cat loves me.")

* 「あなたのネコはかわいいです。」 ^ "Anata no neko wa kawaii desu." (awkward and borderline rude)[1] * 「ネコはかわいいです。」 ^ "Neko wa kawaii desu." (natural) (= "Your cat is cute.")

* 「あの人はここに来てもいい。」 ^ "Ano hito wa koko ni kitemo ii desu." (awkward sometimes)[2] * 「ここに来てもいい。」 ^ "Koko ni kitemo ii desu." (natural) (= "He/She can come here.")

[1] Calling someone あなた anata in polite speech is usually considered very disrespectful. It's recommended to instead use a person's name with a polite honorific, with さん -san being the safest option.

[2] This is only awkward if the topic has already been established. For example, it would be awkward if the sentence followed something like this:

* 「あの人はあそこにいる。」 ^ "Ano hito wa asoko ni iru." (= "He/She is over there.")

Once the topic has been established, it's usually good to drop the topic upon repetition until a new topic is introduced. For instance:

* 「この人は友達です。アダムと言います。アメリカから来て、30歳です。趣味はカラオケと料理です。1年くらい存じています。大事なカンパニーのメンバーだと思います。」 ^ "Kono hito wa tomodachi desu. Adamu to iimasu. Amerika kara kite, sanjuu-sai desu. Shumi wa karaoke to ryouri desu. Ichi-nen kurai sonjite imasu. Daiji na kanpanii no menbaa da to omoimasu." (= "This person is my friend. He is called Adam. He comes from America, and he is 30 years old. His hobbies are karaoke and cooking. He and I have been acquainted for about 1 year. I think he will be an important member of the company.")

Because pronouns are open class in Japanese, they're very flexible. It's quite easy to mix and match pronouns in Japanese. This is one reason why a lot of Japanese media has casts who use different 1st person pronouns. For example, in the Japanese version of Paper Mario, マリオストーリー Mario Story, every Partner who joins Mario uses a different 1st person pronoun:

Kurio (Goombario): オイラ oira Kameki (Kooper): オレッチ orecchi Pinkie (Bombette): あたい atai Paretta (Parakarry): わたし watashi Resaresa (Bow): あたくし atakushi Akarin (Watt): あたち atachi Opuku (Sushie): あたしゃ atasha Pokopie (Lakilester): オレ ore

This helps flesh them out and gives them all distinctive characteristics.

Now, let's talk about 3rd person pronouns in Japanese. In Japanese, the two binary pronouns are 彼 kare (he) and 彼女 kanojo (she). They're not actually used that often, but they're still good to know, especially since many English-written guides for learning Japanese make liberal use of these two pronouns.

* 「彼は男ですから、「僕」や「俺」などの一人称代名詞を使うことが好きです。」 ^ "Kare wa otoko desu kara, "boku" ya "ore" nado no ichi-nin shou daimeishi wo tsukau koto ga suki desu." (= "He is a man, and so likes using first-person pronouns like "boku" and "ore."")

* 「彼女は女ですから、「あたし」や「あたい」などの一人称代名詞を使うことが好きです。」 ^ "Kanojo wa onna desu kara, "atashi" ya "atai" nado no ichi-nin shou daimeishi wo tsukau koto ga suki desu." (= "She is a woman, and so likes using first-person pronouns like "atashi" and "atai."")

(Note that 彼 kare and 彼女 kanojo can also mean boyfriend and girlfriend respectively, though ボーイフレンド booifurendo, ガールフレンド gaarufurendo and パートナー paatonaa, all borrowed from English, are more commonly used these days.)

Here's the problem: 彼 kare and 彼女 kanojo form their plurals by adding ら -ra to the pronoun. You would use 彼ら kare-ra when referring to more than one person if the people are all male or there is at least one male in the group, and you would use 彼女ら kanojo-ra only if all the people being referred to are female. So, Japanese has a similar dilemma to French and Spanish, because they is gendered.

Except, in Japanese, there are a ton of gender-neutral pronouns you can use to refer to a single person. Some linguists even argue that Japanese doesn't technically have pronouns, as pronouns in Japanese work a lot more like glorified nouns.

To get an idea of the gender-neutral pronouns in Japanese, it's good to have some knowledge of how the こそあど言葉 ko-so-a-do words work. To be brief, こ ko, そ so, あ a and ど do are special morphemes that indicate position. Simply put, こ ko refers to something close to the speaker, そ so refers to something close to the listener, あ a refers to something close to neither or to something extract, and ど do refers to something interrogative.

Through this system, こ ko, そ so and あ a can be used to create various 3rd person pronouns, while do ど can be used to create various interrogative pronouns, like who and what. I won't talk about the interrogative pronouns here, because I feel that will clog up the post, but I will absolutely be talking about all the equivalents Japanese has for the singular they.

1: kochira, sochira, achira (こちら,そちら,あちら):

This is one of the safer ways to refer to people. These words literally translate to this way, that way and that way over there, relating to direction. They're more vague ways of referring to direction than ここ koko, そこ soko and あそこ asoko, which indicate an exact direction but can't be used as pronouns.

They are used to:

1) indicate a direction

* 「こちらにあると思う。」 ^ "Kochira ni aru to omou." (= "I think it's here.")

* 「ええ、本当に?そちらに置いたから。」 ^ "Ee, hontou ni? Sochira ni oita kara." (= "Huh, really? Because I put it there.")

* 「そう言えば、あちらにあるかもしれない。」 ^ "Sou ieba, achira ni aru ka mo shirenai." (= "Now that you mention it, it might be over there.")

2) refer to people in the 1st person (こちら kochira) or the 2nd person (そちら sochira)

* 「そちらとパーティーに行けて、とても嬉しかったです。」 ^ "Sochira to paatii ni ikete, totemo ureshikatta desu." (= "I was very happy to be able to go to the party with you.")

* 「こちらこそ。」 ^ "Kochira koso." (= "Me too.")

3) refer to people in the 3rd person

* 「こちらは内のクラスを混ざる。」 ^ "Kochira wa uchi no kurasu wo mazaru." (= "He/She/They is going to join our class.")

* 「そちらは私の親友だもん。」 ^ "Sochira wa watashi no shin'yuu da mon." (= "He/She/They is my best friend, of course.")

* 「私とあちらが仲よくない。」 ^ "Watashi to achira ga naka yokunai." (= "He/She/They and I don't get along.")

When used as 3rd person pronouns, こちら kochira and そちら sochira can typically only be used to refer to someone who is present, while あちら achira can be used to refer to someone who is either present or absent.

These words cannot be made plural, although they can be interpreted as plural depending on context.

2: koitsu, soitsu, aitsu (こいつ,そいつ,あいつ):

This is not a safe way to refer to someone if you don't know what you're doing. It literally translates to this guy, that guy and that guy over there, with the guy being gender-neutral the same way you guys is in English. It's often used by men rather than women, as it's considered quite "un-ladylike," though women can use it. It's used to refer objects, or to people who are of equal or inferior social standing to the speaker, such as friends or children. It can have a rude or hostile edge to it in some contexts.

They are used to:

1) indicate an object

* 「こいつがほしい!」 ^ "Koitsu ga hoshii!" (= "I want this one!")

* 「そいつを貰う!」 ^ "Soitsu wo morau!" (= "I'll take that one!")

* 「それじゃ、私はあいつを買わなきゃ!」 ^ "Sore ja, watashi wa aitsu wo kawanakya!" (= "Then I've just gotta buy that one over there!")

2) indicate a person or animal:

* 「こいつは友達だ。」 ^ "Koitsu wa tomodachi da." (= "He/She/They is a friend.")

* 「そいつ、歌うのは上手だな。」 ^ "Soitsu, utau no wa jouzu da na." (= "He/She/They is good at singing.")

* 「さっき、公園にあいつを会った。」 ^ "Sakki, kouen ni aitsu wo atta." (= "I met him/her/them in the park earlier.")

To make any of these pronouns plural, simply add ら -ra to their end, or add たち -tachi to their end.

3: kono yatsu, sono yatsu, ano yatsu (この奴,その奴,あの奴):

This means the same thing and work exactly the same way as こいつ koitsu, そいつ soitsu and あいつ aitsu. In fact, こいつ koitsu, そいつ soitsu and あいつ aitsu come from この奴 kono yatsu, その奴 sono yatsu and あの奴 ano yatsu. Before that, though, they entered a "transitional phase" and became こやつ koyatsu, そやつ soyatsu and あやつ ayatsu. Those are archaic now, but このやつ kono yatsu, そのやつ sono yatsu and あのやつ ano yatsu are occasionally used instead of こいつ koitsu, そいつ soitsu or あいつ aitsu, usually for emphasis.

They are used to:

1) indicate an object

* 「この奴が最高のゲームだ。」 ^ "Kono yatsu ga saikou no geemu da." (= "This one is the best game.")

* 「その奴のエンジンは壊れたと思う。」 ^ "Sono yatsu no enjin wa kowareta to omou." (= "I think that one's engine is broken.")

* 「私、あの奴が聞こえる。」 ^ "Watashi, ano yatsu ga kikoeru." (= "I can hear that one over there.")

2) indicate a person or animal:

* 「このやつは悔しすぎる!」 ^ "Kono yatsu wa kuyashisugiru!" (= "He/She/They is too frustrating!")

* 「みんなはそのやつが好きだ。」 ^ "Minna wa sono yatsu ga suki da." (= "Everyone likes him/her/them.")

* 「あのやつ、本当に最低だな。」 ^ "Ano yatsu, hontou ni saitei da na." (= "He/She/They is really the worst.")

Like こいつ koitsu, そいつ soitsu and あいつ aitsu, simply add ら -ra to make the pronouns plural, or add たち -tachi.

4: kono kata, sono kata, ano kata (この方,その方,あの方):

This is the absolute most polite way you can refer to someone. This is generally how you'd refer to a superior, such as your boss, or, in some cases, someone you really admire. It's made by combining この kono, その sono or あの ano with 方 kata, a respectful word for person.

* 「この方は私の上司です。」 ^ "Kono kata wa watashi no joushi desu." (= "He/She/They is my boss.")

* 「私、その方に「すばらしい料理人です」と伝えた。」 ^ "Watashi, sono kata ni, "subarasbii ryouri-nin desu" to tsutaeta." (= "I told him/her/them, "You're an amazing cook."")

* 「私はついにあの方を会えた!」 ^ "Watashi wa tsui ni ano kata wo aeta!" (= "I was finally able to meet him/her/them!")

To make these pronouns plural, add 々 -gata to the end of the word. You can also make these words plural by adding たち -tachi to the end of the word, though this is slightly less polite.

5: kono hito, sono hito, ano hito (この人,その人,あの人):

This is a safe way to refer to someone, because it can be both polite and informal. Thus, you're unlikely to offend anyone by using this. It's made by combining この kono, その sono or あの ano with 人 hito, which is the standard word for person.

* 「この人の一番好きな動物はネコだもん。」 ^ "Kono hito no ichi-ban suki na doubutsu wa neko da mon." (= "His/Her/Their favorite animal is cats, of course.")

* 「その人はコンピュータゲームが大好きだ。」 ^ "Sono hito wa konpyuuta geemu ga daisuki da." (= "He/She/They loves video games.")

* 「昨日、あの人と話した。」 ^ "Kinou, ano hito to hanashita." (= "I spoke with him/her/them yesterday.")

There two says to make these pronouns plural. The first is to add 々 -bito to the end of the word, and the second is to add たち -tachi to the end of the word. Both are pretty safe.

6: kono ko, sono ko, ano ko (この子,その子,あの子):

This, in a way, is the "feminine" equivalent of こいつ koitsu, そいつ soitsu and あいつ aitsu. It's used to refer to people your own age or younger, so it's informal. Generally, guys won't use this for other guys, but they will use it for girls, and girls will call guys and other girls this. It's made by combining この kono, その sono or あの ano with 子 ko, which means child or kid.

* 「この子は何をしてるの?」 ^ "Kono ko wa nani wo shite'ru no?" (= "What's he/she/they doing?")

* 「その子の新しいラジオは高い。」 ^ "Sono ko no atarashii rajio ga takai." (= "His/Her/Their new radio is expensive.")

* 「私、あの子にプレゼントをあげた。」 ^ "Watashi, ano ko ni purezento wo ageta." (= "I gave him/her/them a present.")

To make these pronouns plural, add たち -tachi to the end of the word.

7: kono gaki, sono gaki, ano gaki (このガキ,そのガキ,あのガキ):

You shouldn't use this to refer to someone unless they're your age or younger, and you're either very close to them or want to insult them. It's made by combining この kono, その sono or あの ano with ガキ gaki, which literally means brat.

* 「このガキはいい仲間 だ けど…」 ^ "Kono gaki wa ii nakama da kedo..." (= "He/She/They is a good friend, but...")

* 「兄さんはそのガキが好きじゃない。」 ^ "Nii san wa sono gaki ga suki ja nai." (= "My brother doesn't like him/her/them.")

* 「あのガキの先生厳しいな!」 ^ "Ano gaki no sensei wa kibishii na!" (= "His/Her/Their teacher is so strict!")

To make these plural, add either ら -ra or たち -tachi to the end of the word.

8: kono yarou, sono yarou, ano yarou (このヤロウ,そのヤロウ,あのヤロウ):

This one is a big no-no unless you're very close with a person your age or younger, or if you want to offend the hell out of someone. It's made by combining この kono, その sono or あの ano with ヤロウ yarou, which literally translates to bastard or, if you're generous, rascal.

* 「このヤロウはビールを盗んだ!」 ^ "Kono yarou wa biiru wo nusunda!" (= "He/She/They stole the beer!")

* 「私、そのヤロウの声が別に好きじゃない。」 ^ "Watashi, sono yarou no koe ga betsu ni suki ja nai." (= "I don't really like his/her/their voice.")

* 「あのヤロウが全然分かれない!」 ^ "Ano yarou ga zenzen wakarenai!" (= "I can't understand him/her/them at all!")

If you want to make the words plural, add ら -ra or たち -tachi to their ends.

9: kore, sore, are (これ,それ,あれ):

This is basically the equivalent of calling someone it. I know some people prefer that, so I thought I'd include these words, which actually translate to this one, that one and that one over there, because Japanese doesn't have a direct word for it. As usual, you probably shouldn't use this for someone, especially if they're older than you, unless they specifically request it or you want to insult them.

They are used to:

1) indicate an object

* 「これは私のリンゴだ。」 ^ "Kore wa watashi no ringo da." (= "This one is my apple.")

* 「私、それを買いたい。」 ^ "Watashi, sore wo kaitai." (= "I want to buy that one.")

* 「あれがネコのボールだ。」 ^ "Are ga neko no booru da." (= "That one over there is the cat's ball.")

2) indicate a person or animal:

* 「私、これに行きたい。」 ^ "Watashi, kore ni ikitai." (= "I want to go with it.")

* 「それは面白い人だ。」 ^ "Sore wa omoshiroi hito da." (= "It is an interesting person.")

* 「あれは音楽が上手だ。」 ^ "Are wa ongaku ga jouzu da." (= "It is good at music.")

As far as I know, these words can't be made plural, but they can be plural in meaning sometimes, depending on context.

How to politely request to be referred to a certain way in Japanese:

To wrap up this post, here's how to politely request to be referred to with a particular pronoun in Japanese. I included the Japanese equivalents for he, she, they and it.

1)

* 「私の優先の人称代名詞は「彼」です。 ^ "Watashi no yuusen no ninshou daimeishi wa "kare" desu." (= "My preferred personal pronoun is "he."")

* 「私の優先の人称代名詞は「彼女」です。」 ^ "Watashi no yuusen no ninshou daimeishi wa "kanojo" desu." (= "My preferred personal pronoun is "she."")

* 「私の優先の人称代名詞は「あの人」です。」 ^ "Watashi no yuusen no ninshou daimeishi wa "ano hito" desu." (= "My preferred personal pronoun is "they."")

* 「私の優先の人称代名詞は「あれ」です。」 ^ "Watashi no yuusen no ninshou daimeishi wa "are" desu." (= "My preferred personal pronoun is "it."")

2)

* 「私は「彼」と呼ぶことが好きです。」 ^ "Watashi wa "kare" to yobu koto ga suki desu." (= "I like to be called "he."")

* 「私は「彼女」と呼ぶことが好きです。」 ^ "Watashi wa "kanojo" to yobu koto ga suki desu." (= "I like to be called "she."")

* 「私は「あの人」と呼ぶことが好きです。」 ^ "Watashi wa "ano hito" to yobu koto ga suki desu." (= "I like to be called "they."")

* 「私は「あれ」と呼ぶことが好きです。」 ^ "Watashi wa "are" to yobu koto ga suki desu." (= "I like to be called "it."")

3)

* 「私に「彼」と呼んでください。」 ^ "Watashi ni "kare" to yonde kudasai." (= "Please call me "he."")

* 「私に「彼女」と呼んでください。」 ^ "Watashi ni "kanojo" to yonde kudasai." (= "Please call me "she."")

* 「私に「あの人」と呼んでください。」 ^ "Watashi ni "ano hito" to yonde kudasai." (= "Please call me "they."")

* 「私に「あれ」と呼んでください。」 ^ "Watashi ni "are" to yonde kudasai." (= "Please call me "it."")

4)

* 「私に「彼」と呼んでくださったら、とてもありがたいです。」 ^ "Watashi ni "kare" to yonde kudasattara, totemo arigatai desu." (= "If you could call me "he," I would be very grateful.")

* 「私に「彼女」と呼んでくださったら、とてもありがたいです。」 ^ "Watashi ni "kanojo" to yonde kudasattara, totemo arigatai desu." (= "If you could call me "she," I would be very grateful.")

* 「私に「あの人」と呼んでくださったら、とてもありがたいです。」 ^ "Watashi ni "ano hito" to yonde kudasattara, totemo arigatai desu." (= "If you could call me "they," I would be very grateful.")

* 「私に「あれ」と呼んでくださったら、とてもありがたいです。」 ^ "Watashi ni "are" to yonde kudasattara, totemo arigatai desu." (= "If you could call me "it," I would be very grateful.")

The ko-so-a-do chart for pronouns:

That’s all I’ve got for now. Thanks for reading. :)

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

国名および通称はオランダ語でNederland(ネーデルラント)。これは「低地の国」「低地地方」を意味する普通名詞に由来するため、基本的に定冠詞をつける必要がある。通称の "Nederland" は、オランダ王国の欧州における国土を意味するため単数形で、正式名称に使われている「de Nederlanden」は、海外領土を含めた概念のため複数形である。ゲルマン系言語ではドイツ語でdie Niederlande、ラテン系言語ではフランス語でles Pays-Bas、スペイン語でlos Países Bajos、イタリア語でi Paesi Bassi(いずれも語義は同じ)。いずれも複数形であるのは、伝統的に現在のベネルクス三国のある低地地域一帯の領邦群の歴史的総称を受け継いでいるからである。なお、複数形ではあるものの、英語やスペイン語など言語によっては、しばしば集合名詞あるいは「王国」を略したものとして単数扱いされる。 俗称の「Holland(ホラント)」もよく使われるが、これはスペインの支配に対して起こした八十年戦争で重要な役割を果たしたホラント州(現在は南北2州に分かれる)の名に由来し、固有名詞であるため冠詞がつかない。 公式の英語表記は、the Netherlands(ザ・ネザーランズ)。形容詞および名詞形のDutch(ダッチ)は、元来ドイツ(Duitsch)を指し、同国の支配から脱した17世紀以降オランダ(人、語)を意味するものに変わっていった。ただし、歴史的に英蘭間で貿易や海外進出をめぐって激しい競争と対立が発生したことから、軽蔑のニュアンスが強く[12]、「Netherlander」や「Hollander」が用いられることもあるが、オランダ政府は公式に「Dutch」を使い[13]、民間企業も「Dutch」を使用している[14]。 日本語の表記はオランダ。漢字表記は、和蘭、和蘭陀、阿蘭陀、荷蘭陀[15]、荷蘭、尼徳蘭(ネーデルラントの音訳)と表記され、蘭と略される。由来はポルトガル語における「ホラント」の表記「Holanda [ɔˈlɐ̃dɐ]」が、戦国時代に来航したポルトガル人宣教師によってもたらされたことによる。 オランダ政府は、2020年1月1日をもって、国名としての「ホラント」の使用を廃止し、オランダ外務省も諸外国にこの通称から変更し「ネーデルラント」とするよう呼びかけている[16][17]。なお、日本のオランダという呼称については、日本語の言葉として定着していることから変更は求めないとしている[17][18]。

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

帰ってきたウルトラマン、幻の主題歌「戦え!ウルトラマン」。

作詞は東京一(円谷一の作詞家名義)、歌は主役でMG5の団次郎。

(MG5って。笑)

音楽が冬木透ってどういうことなんだろう?

(主題歌以外のサウンドトラック担当なのか?)

作曲を担当したすぎやまこういちは、こちらを主題歌としたかったそうですが、子供番組ということもあり、わかりやすい「帰ってきたウルトラマン」が主題歌として採用。

しかし、現在はマニアの間ではこちらの幻バージョンが断然人気。

この動画はパイロット版か実際に使われたかはわかりませんが、大胆にボーカルを抜いたマイナスワンのインストで凄くオシャレです。

最初は2ビート進行で、途中からファンクのリズム���変わる!

(なんと素敵な!笑)

ベースがウオーキングで完全にジャズ・ファンク。

(たまらんです)

ウルトラマンシリーズ定番のシャドゥ・アート映像バックのキラキラ感がサイケデリック。

70年代の欧米のテレビドラマのOPみたいでかっこいいので個人的にはこちらが好みです。

大江戸捜査網OP音楽もこんな感じだ。

(確かに、笑。70年代凄い)

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

<正論>CO2は生命育む恵みの物質

東京大学名誉教授・渡辺正

CO2を悪とみる1988年以来の発想は、中世の魔女狩りに似て、社会を壊すエセ科学だった。かつて35年ほど光合成を研究した工学系の化学屋が、そう断じる根拠をご披露したい。

快適な暮らしもその恵み

約30万種の陸上植物は、太陽光を動力にした光合成で、安定な水とCO2から高エネルギー物質を作る。必須物質の全部を生合成する植物は、単独で繁栄できる。

物質合成能の低い動物は、植物の「製品」を強奪して生きるしかない。草食動物はむろんのこと、肉食動物も間接的に植物を食べている。要するに植物から見た動物は「寄生虫」にすぎない。

大魚や鯨を頂点とする海中の食物連鎖も、植物プランクトンと藻類がCO2から作る有機物を原点にして成り立つ。

私たちも植物の恵みで生きる。飲食物のうち、水と食塩を除くほぼ全部が、直接間接の光合成産物だとわかる。体重72キロの筆者を作る13キロの炭素原子も、元は大気中のCO2分子だった。

光合成は、私たちに飲食物のほか材料(木材など)と繊維(綿・麻・紙)も恵む。1億~2億年前の光合成産物は、化学変化して石油や石炭、天然ガスになった。

文明や文化を創造し、快適な暮らしと移動法を手に入れ、情報化社会を作ったヒトも、食物から産業用動力までの全部を植物に頼る。高層ビルが演出する都会の華麗な夜景も植物の恵み、つまりはCO2の恵みだと心得よう���

CO2増え豊かさ増す世界

CO2削減の声が芽生えてから大合唱に育つまで35年余、大気のCO2濃度は増え続けた(たまたま同時進行した昇温の原因は多様)。直近の25年間はペースを上げながら15%以上も増え、世界を豊かにしつつある。なぜか?

大気に適量の酸素がたまった4億~5億年前に緑藻の一種が上陸し、分化・進化を経て1億~2億年前の恐竜時代に大繁栄した。葉の化石を調べた結果などから、当時のCO2は現在の5~10倍も濃かったと推定されている。

当時の生物を先祖とする植物に、今のCO2は薄すぎる。だからこそ本格的ハウス栽培では、石油燃焼装置を使って内部のCO2濃度を外気の3~4倍に上げ、植物=作物の生育を速める。

大気に増えるCO2は、むろん地球の緑化を進め、ひいては私たちの食糧を増やしてくれる。

衛星観測によると地球の緑は、30年間に約10%ずつ増えてきた。作物の収量も快調に増えた状況を、国連食糧農業機関(FAO)の統計が語り尽くす。食糧の増加は、8億人以上ともいう飢餓人口の低減にも貢献してきた。

そんなCO2を減らすのは、全人類に向けた大犯罪だろう。

カネと利権「CO2悪玉論」

CO2は、気温変動の主因ではない。たとえばCO2が単調に増え続けた過去2千年のうち、10~13世紀は今よりだいぶ暖かく(中世温暖期)、江戸期を含む14~19世紀は寒かった(小氷期)。

先述の1億~2億年前は、気温も3度は高かったとおぼしい。それでも熱暴走など起きず、生物が栄えたわけだから今後、CO2が倍増しても問題はない(CO2の赤外線吸収は飽和に近いため、倍増時でも昇温は0・5度未満)。

だが国連は、東西冷戦の終結が見えた88年、CO2温暖化危機を口実に、排出の多い先進国の富を途上国へ流す南北調停仕事を思いつく。だから定例集会COPでも、近年は「カネよこせ(途上国)」と「ちょっと待て(先進国)」の口論だけをやってきた。

実のところ国連の企(たくら)みは、とうの昔に破綻している。80年代末は途上国だった中国が今や世界一のCO2排出国なのに、国の分類を変えないというルール上、今もって「途上国」なのだから。

けれど、環境浄化が進んで失業に怯(おび)えつつ国連と協働した面々が、一件を「解決可能な環境問題」という虚構に仕立て上げた。

深刻そうな話にメディアが飛びつき、政治家は票を期待して血税を垂れ流す。巨費の利権を産学界の亡者(一部は知人)が狙い、脱炭素など非科学語を操って庶民を騙(だま)す世になった。

政府は昨今、脱炭素・経済成長の営みをエセ英語でグリーントランスフォーメーション(GX)と呼ぶ。10年で投資150兆円を期待するというけれど、「脱炭素」の成功だけはありえない。

たとえば、バイオ燃料のCO2発生量は石油より少ない…と叫ぶ集団がいる。事実なら人類は燃料問題から解放され、化石燃料の大半を掘らずにすむ。だがバイオ燃料はCO2を増やす代物だから、石油採掘が減る気配すらない。

バイオ燃料は善…という噓が、2022年12月の航空法改正(バイオ燃料導入)につながった。審議会に理系の人はいないのか?

なお形容詞「グリーン」は、遠い未来の姿ではなく、CO2が増え、植物界も食卓も豊かさを増す現状にこそふさわしい。

GX関係者はCO2が減ると誤解して喜び、筆者は増えると確信して喜ぶ。私たちは妙な時代を生きている。(わたなべ ただし)

27 notes

·

View notes