#Δ Φ

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Eddie Dark

Η ΠΙΟ ΔΕΙΛΗ ΕΠΙΣΤΡΟΦΗ

1 note

·

View note

Text

i’m no hero

Toji Fushiguro x female reader you meet Toji by chance when you were struggling with an illness. you end up dating the intimidating man, who turns out to be pretty soft. he's ready for a serious relationship and wants to treat you right!!

nb: I placed Toji in his 40s. feel free to imagine whatever age you're comfortable with 18+ content. mdni.

"good girl" / "daddy" / explicit sex throughout

stranger 3.4k α sfw, first meeting, age gap sweet 3.2k β f. oral, size kink control 4.1k ⁺⋆ m. oral, degrading, spitting, gag risky 4.4k ε cockwarming, voyeurism, ft. satoru past 1.5k Δ implied group sex + m x m oral hot date: ♡ princess treatment! part one 2.5k φ m. oral, f. orgasm denial part two 1.6k Φ cowgirl, doggy play nice: ♡ explicit threesome ft. satoru! part one 2.2k ☾ f. oral, reverse cowgirl, m. oral part two 1.3k λ doggy, squirting, m x m oral, f x m oral part three 1.4k μ face sitting, dp [oral + vaginal]

BONUS!

games π guessing game ft. satoru + nanami

toji jjk m.list

likes, comments + reblogs appreciated! ♡

#jujutsu kaisen smut#toji fushiguro#meeting toji fushiguro#toji fushiguro smut#sweet toji#jjk toji#toji x reader#toji smut#toji x you#fushiguro toji#jjk fic#jjk#jjk x reader#jujutsu kaisen

258 notes

·

View notes

Text

Awoo! Hello tumblr! 🐾 🐺

ΘΔ & φ ζ 𐤀 ξ μ χ β δ Ω Σ ι ꩜

We are known as Waya (or Waya Wolf) on the inter web! We are an OSDD system, abuse survivor, therian, polytheistic shaman and activist. We are very passionate about mental health, harm prevention, sexology, psychology and de-stigmatization.

- Contact void, pro consent, anti abuse omniphile zoosexual. Studying psychology with a focus in paraphilias. Pro kink, pro fiction, radical compassion, radical queerness and anti harassment, doxxing and call out culture.

We have coined and made multiple things for the paraphilia community and some of them we can’t post here because we may get suspended but if you wish to know more about us or our activism please check out our website ~ http://wayaden.straw.page

Be Kind, Howl Loud 🌈

#pro para#pro paraphilia#paraphilias#omniphilia#text#ours#pro radqueer#radqueer#pro rq#rq safe#rq community#pro paraphile#paraphilia safe#proship#pro kink#pro fiction#zoo#zoophillia#zoosexual#alef zoo

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome to the premier of One-Picture-Proof!

This is either going to be the first installment of a long running series or something I will never do again. (We'll see, don't know yet.)

Like the name suggests each iteration will showcase a theorem with its proof, all in one picture. I will provide preliminaries and definitions, as well as some execises so you can test your understanding. (Answers will be provided below the break.)

The goal is to ease people with some basic knowledge in mathematics into set theory, and its categorical approach specifically. While many of the theorems in this series will apply to topos theory in general, our main interest will be the topos Set. I will assume you are aware of the notations of commutative diagrams and some terminology. You will find each post to be very information dense, don't feel discouraged if you need some time on each diagram. When you have internalized everything mentioned in this post you have completed weeks worth of study from a variety of undergrad and grad courses. Try to work through the proof arrow by arrow, try out specific examples and it will become clear in retrospect.

Please feel free to submit your solutions and ask questions, I will try to clear up missunderstandings and it will help me designing further illustrations. (Of course you can just cheat, but where's the fun in that. Noone's here to judge you!)

Preliminaries and Definitions:

B^A is the exponential object, which contains all morphisms A→B. I comes equipped with the morphism eval. : A×(B^A)→B which can be thought of as evaluating an input-morphism pair (a,f)↦f(a).

The natural isomorphism curry sends a morphism X×A→B to the morphism X→B^A that partially evaluates it. (1×A≃A)

φ is just some morphism A→B^A.

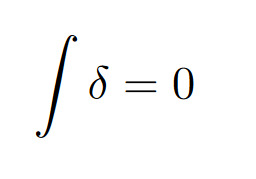

Δ is the diagonal, which maps a↦(a,a).

1 is the terminal object, you can think of it as a single-point set.

We will start out with some introductory theorem, which many of you may already be familiar with. Here it is again, so you don't have to scroll all the way up:

Exercises:

What is the statement of the theorem?

Work through the proof, follow the arrows in the diagram, understand how it is composed.

What is the more popular name for this technique?

What are some applications of it? Work through those corollaries in the diagram.

Can the theorem be modified for epimorphisms? Why or why not?

For the advanced: What is the precise requirement on the category, such that we can perform this proof?

For the advanced: Can you alter the proof to lessen this requirement?

Bonus question: Can you see the Sicko face? Can you unsee it now?

Expand to see the solutions:

Solutions:

This is Lawvere's Fixed-Point Theorem. It states that, if there is a point-surjective morphism φ:A→B^A, then every endomorphism on B has a fixed point.

Good job! Nothing else to say here.

This is most commonly known as diagonalization, though many corollaries carry their own name. Usually it is stated in its contraposition: Given a fixed-point-less endomorphism on B there is no surjective morphism A→B^A.

Most famous is certainly Cantor's Diagonalization, which introduced the technique and founded the field of set theory. For this we work in the category of sets where morphisms are functions. Let A=ℕ and B=2={0,1}. Now the function 2→2, 0↦1, 1↦0 witnesses that there can not be a surjection ℕ→2^ℕ, and thus there is more than one infinite cardinal. Similarly it is also the prototypiacal proof of incompletness arguments, such as Gödels Incompleteness Theorem when applied to a Gödel-numbering, the Halting Problem when we enumerate all programs (more generally Rice's Theorem), Russells Paradox, the Liar Paradox and Tarski's Non-Defineability of Truth when we enumerate definable formulas or Curry's Paradox which shows lambda calculus is incompatible with the implication symbol (minimal logic) as well as many many more. As in the proof for Curry's Paradox it can be used to construct a fixed-point combinator. It also is the basis for forcing but this will be discussed in detail at a later date.

If we were to replace point-surjective with epimorphism the theorem would no longer hold for general categories. (Of course in Set the epimorphisms are exactly the surjective functions.) The standard counterexample is somewhat technical and uses an epimorphism ℕ→S^ℕ in the category of compactly generated Hausdorff spaces. This either made it very obvious to you or not at all. Either way, don't linger on this for too long. (Maybe in future installments we will talk about Polish spaces, then you may want to look at this again.) If you really want to you can read more in the nLab page mentioned below.

This proof requires our category to be cartesian closed. This means that it has all finite products and gives us some "meta knowledge", called closed monoidal structure, to work with exponentials.

Yanofsky's theorem is a slight generalization. It combines our proof steps where we use the closed monoidal structure such that we only use finite products by pre-evaluating everything. But this in turn requires us to introduce a corresponding technicallity to the statement of the theorem which makes working with it much more cumbersome. So it is worth keeping in the back of your mind that it exists, but usually you want to be working with Lawvere's version.

Yes you can. No, you will never be able to look at this diagram the same way again.

We see that Lawvere's Theorem forms the foundation of foundational mathematics and logic, appears everywhere and is (imo) its most important theorem. Hence why I thought it a good pick to kick of this series.

If you want to read more, the nLab page expands on some of the only tangentially mentioned topics, but in my opinion this suprisingly beginner friendly paper by Yanofsky is the best way to read about the topic.

#mathblr#mathematics#set theory#diagram#topos theory#diagonalization#topology#incompleteness#logic#nLab#Lawvere#fixed point#theorem#teaching#paradox#halting problem#math#phdblr#Yanofsky#Cantor#Tarski#Gödel#Russell#philosophy#category theory

103 notes

·

View notes

Text

honorable mentions: δ (lowercase delta) and ε (lowercase epsilon). i ran out of space ;-;

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

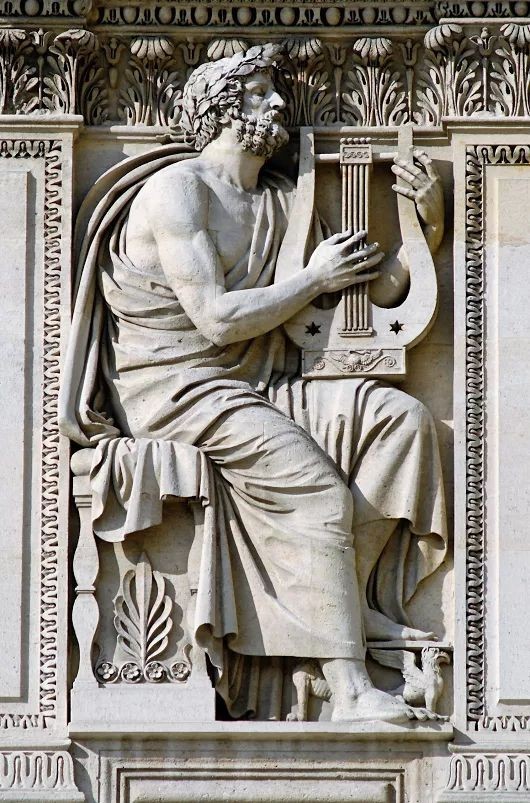

On Achilles and Patroclus Hail Aeacides and Menoetiades, ye twain supreme in Love and Arms.

Text of unknown authorship, it's number 143 of Book 7 of the Greek Anthology. This is the translation by W.R. Paton.

Something about being together in love and in war. Something about sharing your most vulnerable side and your most destructive side. Something about the love implicit in the idea of a loyal comrade-in-arms. Something about how it's not Achilles who is supreme, but Achilles and Patroclus. It isn't a greeting hail to Aeacides (Achilles, descendant of Aeacus), it's a greeting to Aeacides and Menotides (Patroclus, son of Menoetius).

They're one, Your Honor. Their ashes are one. Together in life, while they love and while they destroy, and together in death, forever one as, as Patroclus said, they were raised in Phthia.

NOTE: This extra part is just to avoid anyone coming to warn me about how I shouldn't use a modern lens on their relationship and stuff like that, so if you're not interested in it, ignore it. This is the Greek text:

ἄνδρε δύω φιλότητι καὶ ἐν τεύχεσσιν ἀρίστω, χαίρετον, Αἰακίδη, καὶ σύ, Μενοιτιάδη.

The word for love "φιλότητι" has a wider meaning than necessarily romantic/sexual love, although this is one of the meanings. According to the Cambridge Greek Lexicon:

φιλότης φιλότης ητος dial.φιλότᾱς ᾱτος f.[φίλος] 1 friendship (betw. persons) Hom. (betw. states or sim) Hdt. And. (personif) Friendship Hes. 2 love (betw. two people) Od. Sapph. Thgn. Pi. AR (ref. to a specific relationship) Thgn. Pi. AR. 3 spirit of friendliness; friendliness, friendship Hom. AR.affection, love (for someone, sts. w.gen.pers.; esp. in dat., as the motivation for an action) Hom. Thgn. Pi. Trag (philos.) Love (as the attraction betw. the elements) Emp. 4 physical affection; love (shown to someone, ref. to embraces) E. (ref. to lovemaking) Hom. Hes. Archil. Mimn. 5 (ref. to the object of one's affection) dear friend (as a term of address) Pl.nearest and dearest (ref. to one's wife and children) Lys.

According to LSJ:

φιλότης φῐλότης, ητος, ἡ, A). friendship, love, affection, μηνιθμὸν μὲν ἀπορρῖψαι φιλότητα δ’ ἑλέσθαι Il. 16.282 ; ξεῖνοι δὲ διαμ��ερὲς εὐχόμεθ’ εἶναι ἐκ πατέρων φιλότητος Od. 15.197 , cf. S. Ph. 1122 (lyr.); κατ’ ἡλικίην τε καὶ φ. ἰλαδὸν συγγίνεσθαι Hdt. 1.172 : pl., Thgn. 860 ; φιλότητι in, with, from friendship or affection, Il. 3.453 , Od. 3.363 , 10.43 ; ἐν φ. διέτμαγεν ἀρθμήσαντε Il. 7.302 ; φιλότητί γε yes, in affection [we are brothers], E. IT 498 ; φιλότητι χειρῶν with friendly services, Id. Or. 1048 ; φιλότητα μετ’ ἀμφοτέροισι βάλωμεν Il. 4.16 ; φ. μετ’ ἀμφοτέροισι τίθησι ib. 83 , cf. Od. 24.476 ; παρὰ σεῖο τυχὼν φιλότητος 15.158 ; φιλότητα παρασχεῖν Il. 3.354 , Od. 15.55 ; ἄγειν ἐς φ. Sapph. 1.19 ; εἰς ἀρθμὸν ἐμοὶ καὶ φιλότητα .. ἥξει A. Pr. 193 (anap.); ὑδαρεῖ σαίνειν φ. Id. Ag. 798 (anap.); φ. τινός friendship with, affection for, Od. 14.505 , S. Aj. 1410 (anap.); διὰ τὴν λίαν φ. βροτῶν by his overgreat love for men, A. Pr. 123 (anap.); ξενίαι καὶ φιλότητες πρός τινας And. 1.145 : in addressing persons, ὦ φιλότης, = ὦ φίλος , my dear friend, Pl. Phdr. 228d , Philox. 2.7 , 34 ; without ὦ, Hp. Ep. 17 . 2). of friendship between states, φιλότητα καὶ ὅρκια πιστὰ ταμόντες Il. 3.73 , cf. 94 , 323 ; ναυμαχεῖν ὑπὲρ τῆς φ. Lys. 2.35 ; φ. ἀντὶ διαφορᾶς ἐθέλοντες ποιεῖσθαι And. 3.30 . 3). prov., ἰσότης φιλότητα ἀπεργάζεται Pl. Lg. 757a ; more shortly, ἰσότης φ. Arist. EN 1168b8 . 4). in Hom., freq. of sexual love or intercourse, in various phrases: μίγη φιλότητι καὶ εὐνῇ Il. 6.25 , cf. 3.445 , al.; ἵνα μισγεαι ἐν φ. 2.232 ; καθεύδετον ἐν φ., παραλέξομαι ἐν φ., Od. 8.313 , Il. 14.237 ; ὕπνῳ καὶ φ. δαμείς ib. 353 , cf. 207 , 13.636 : less freq. c. gen., ἀείδειν ἀμφ’ Ἄρεος φιλότητος ἐϋστεφάνου τ’ Ἀφροδίτης Od. 8.267 ; φ. γυναικός Hes. Sc. 31 , cf. Th. 374 , 405 , 625 , 822 : pl., Pi. P. 9.39 , N. 8.1 , Antipho Soph. 49 . 5). personified, = φιλία 1.5 , opp. νεῖκος, Emp. 17.20 , al., cf. Hes. Th. 224 .(φιλία is the common prose form.)

Anyway, I don't really care if the author wanted to refer to friendship or them as a couple (they were known both ways in ancient times), I just care that they love each other. Friends, family, lovers, they are still one.

Also, I think the term for Arms is "τεύχεσσιν". Hence the "Love and Arms". At least, that's what it seemed to me searching online dictionaries.

#Patroclus#Achilles#Patrochilles#Anyway tagging the ship because I ship them#And I want my blog organized#Birdie.txt

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I think what annoys me more than saying the Dirac delta distribution is a function is when people say it's 0 everywhere except when x=0, it is infinity. Like that is just not compatible with the fact it's integral over ℝ is supposed to be 1. Suppose we did define an extended function that way:

δ is a Lebesgue measurable since {x∈ℝ:δ(x)<a} is empty for a≤0 and ℝ\{0} for a>0 which are both Lebesgue measurable sets. δ is non-negative so we can calculate the integral via

where the inequality is pointwise.

Now since δ is 0 except at x=0, we require any simple measurable function φ≤δ must also be 0 except at x=0. This leaves us with a constant times an indicator function:

where a>0, and

Then we have

So taking the supremum over a we get

So δ cannot be the Dirac delta distribution. You really need the theory of distributions to talk about the Dirac delta.

P.s. I know this isn't the typical notation for an integral with respect to a measure but this was the notation I had in my lectures

#this is partly also a way to expose some people to a bit of measure theory#but it is mostly a vent about common descriptions of the dirac delta distribution#maths posting#analysis#measure theory#undescribed#lipshits posts

37 notes

·

View notes

Note

Chapter 1

The greek alphabet:

α - alpha, the letter a

β - beta, the letter b

γ - gamma, g

δ - delta, d

ε - epsilon, short e

ζ - zeta, z

η - eta, long e

θ - theta, th

ι - iota, i

κ - kappa, k

λ - lambda, l

μ - mu, m

ν - nu, n

ξ - xi, x

ο - omicron, short o

π - pi, p

ρ - rho, r

σ - sigma, s

ς - sigma, s (but only at the end of letters)

τ - tau, t

υ - upsilon, u/y

φ - phi, f

χ - chi, ch (like in the word loch)

ψ - psi, ps (like in eclipse)

ω - omega, long o

Greek doesn't have the letter h, so when words start with a vowel, there is an accent to show either smooth breathing or rough breathing.

for example :

ó - rough breathing

ò - smooth breathing

when a word starts with rough breathing, it means it has a h in front of it.

when iota follows a long alpha, eta or omega, then it is written in miniature form underneath. This is called iota subscript

Present tense:

I - ω

you - εις

he/she/it - ει

we - ομ��ν

you pl - ετε

they - ουσι(ν)

The 3rd person plural form has a moveable nu at the end. This means that when the word after the verb starts with a vowel or if the verb is at the end of the sentence, then it has a nu at the end. If not, the ending is just ουσι.

Declensions

In greek, a nouns ending reflects its role in the sentence, or its case.

There are 4 cases in greek

nominative - the subject

Accusative - the object (also used for expressing time, and certain prepositions)

Genitive - possession and some prepositions

Dative - to or for and also for some prepositions

The (main) endings for first declension are as follows

sg

nom - η

acc - ην

gen - ης

dat - ῃ

pl

nom - αι

acc - ας

gen - ων

dat - αις

And the endings for second declension are:

sg

nom - ος (or ον if neuter)

acc - ον

gen - ου

dat - ῳ

pl

nom - οι (or α if neuter)

acc - ους (or α if neuter)

gen - ων

dat - οις

Articles

Greek also has the definite article (translated as "the") which must agree to the noun it is describing in case, gender and number.

Here is the definite article in greek:

sg m f n

nom - ό ή το

acc - τον την το

gen - του της του

dat - τῳ τῃ τῳ

pl m f n

nom - όι άι τα

acc - τους τας τα

gen - των των των

dat - τoις ταις τoις

These are extremely similar to the declension endings but with a tau at the beginning

Negatives

Negatives are formed with the word ου, which changes to ουκ before a vowel with smooth breathing and ουχ before a vowel with rough breathing

ooooh thank you!!

this is all very interesting.... the declinations are super cool glad there doesn't seem to be that many!!!

thanks for writing all this out :O

#for later#language help#<-i do not want to lose these#thanks for the ask!#rania rambles#emelin speaks to me

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just clicked for me:

Sigma (σ) bonds - because of the 's' orbital

Pi (π) bonds - because of the 'p' orbital

Delta (δ) bonds - because of the 'd' orbital

Phi (φ) bonds - because of the 'f' orbital

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, here's a thread on "how to read the Greek alphabet?"

The Greek alphabet consists of 24 letters:

α,β,γ,δ,ε,ζ,η,θ,ι,κ,λ,μ,ν,ξ,ο,π,ρ,σ;ς,τ,υ,φ,χ,ψ,ω.

So here we go:

Α,α-alfa [a]

Β,β-beta[b]

Γ,γ-gamma [g]

Δ,δ- delta [d]

Ε,ε-epsilon[e;short]

Ζ,ζ-dzeta [dz]

Η,η-eta[e;long]

Θ,θ-theta [th]

Ι,ι-jota[i]

Κ,κ-kappa [k]

Λ,λ-lambda[l]

Μ,μ-mi [m]

Ν,ν-ni [n]

Ξ, ξ- ksi [ks]

Ο,ο-omikron [o;short]

Π,π-pi [p]

Ρ,ρ- ro [r]

Σ,σ(at beginning and in the middle), ς(in the end)-sigma [s]

Τ,τ-tau [t]

Υ,υ-ypsilon [y]

Φ,φ-phi [f or ph]

Χ,χ-khi [ch or kh]

Ψ,ψ-psi [ps]

Ω,ω-omega[o;long]

#ancient greece#ancient greek#classicalphilology#ancient history#hellenism#classics#greek history#classical studies#hellenismos

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Symbols for The Sims 4 Gallery 🌟

Please note: The symbols displayed here on Tumblr might appear differently on the Sims 4 gallery. To see their true appearance, copy and paste them directly into the gallery description. Misc : ♨ ☏ ☎ ⚒ ⛘ ♠ ♥ ♣ ★ ☆ ♡ ♤ ♧ ♩ ♪ ♬ ♭ ♯ ♂ ♀ ※ † ‡ § ¶ 冏 웃 유 ⚉ 쓰 ヅ ツ 〠 ☜ ☞ † ↑ ↓ ◈ ◀ ▲ ▼ ▶ ◆◇◁ △ ▽ ▷ ◙ ◚ ◛ ▬ ▭ ▮ ▯ ▦ Ω ◴ ◵ ◶ ◷ ⬢ ⬡ ▰ ◊ ⬟ ⬠ ∝ ∂ ∮ ∫ ∬ ∞ √ ≠ ± × ÷ 兀 ∏ ㄇ П п ∏ Π π $ ¢ € £ ¥ ₩ ₹ ¤ ƒ ฿ Ł Ð ◸ ◹ ◺ ◿ ◢ ◣ ◤ ◥ ◠ ◡ Shapes : □ ■ ▒ ▓ █ ▄ ▌ ▧ ▨ ▩ ▒ ■ □ ▢ ▣◃ ▤ ▥ ░ ▁ ▂ ▃ ��� ▅ ▆ ▇ █ ▉ ▊ ▋ ▋ ▌ ▍ ▎ ∇ ▵ ⊿ °○ ● ⊕ º • 。 ○ ◯ O ⓞ ◎ ⊙▹

Arrows : ⇧ ⇒ ↹ ↘︎ ↗︎ ↙ ↖ ↕ ↔ ︿ ﹀ ︽ ︾ ← → ⇔ ↸ Brackets: 〖 〗 〘 〙 〈 〉 《 》 「 」 『 』 【 】 〔 〕 ︵ ︶ ︷ ︸ ︹ ︺ ︻ ︼ ︽ ︾ ︿ ﹀ ﹁ ﹂ ﹃ ﹄ ﹙ ﹚ ﹛ ﹜ ﹝ ﹞ ﹤ ﹥ ( ) < > { } ‹ › « » 「 」 ≪ ≫ ≦ ≧ [ ] ⊆ ⊇ ⊂ ⊃ Lines: ☰ ≡ Ξ – — ▏ ▕ ╴ ‖ ─ ━ │ ┃ ‒ ― ˍ ╋ ┌ ┍ ┎ ┏ ┐ ┑ ┒ ┓ └ └ ┕ ┖ ┗ ┘ ┙ ┚ ┛ ├ ├ ┝ ┞ ┟ ┠ ┡ ┢ ┣ ┤ ┥ ┦ ┧ ┨ ┩ ┪ ┫ ┬ ┭ ┮ ┯ ┰ ┱ ┲ ┳ ┴ ┵ ┶┷ ┸ ┹ ┺ ┻ ┼ ┽┾ ┿ ╀ ╁ ╂ ╃╄ ╅ ╆ ╇╈ ╉ ═ ║ ╒ ╓ ╔ ╔ ╔ ╕ ╕ ╖ ╖ ╗ ╗ ╘ ╙ ╚ ╚ ╛ ╛ ╜ ╜ ╝ ╝╞ ╟╟ ╠ ╡ ╡ ╢ ╢ ╣ ╣ ╤ ╤ ╥ ╥╦ ╦ ╧╧ ╨ ╨ ╩ ╩ ╪ ╪ ╫ ╬ ╱ ╲ ╳ Χ χ × ╭ ╮ ╯ ╰ ∧ ∨ ¦ ⊥¬ ∠ Punctuation: ‼ … ∷ ′ ″ ˙ ‥ ‧ ‵ 、 ﹐ ﹒ ﹔ ﹕ ! # $ %‰ & , . : ; ? @ ~ · . ᐟ ¡ ¿ ¦ ¨ ¯ ´ · ¸ ˉ ˘ ˆ ` ˊ ‵ 〝 〞 〟〃 " '′ ″ ‴ ‘’ ‚ ‛“ ” „ ‟ " '* ﹡* ⁂ ∴ ∵ Letters : © ® ℗ ∨ ㎖ ㎗ ㎘ ㏄ ㏖ ㏒ μ ℃ ℉ ㎍ ㎎ ㎏ ㎈ ㎉ ㎐ ㎑ ㎒ ㎓ ㎾ ㏑ ㏈ ㏐ ㏂ ㏘ ㎳ ㎭ ㏅ ㎪ ㎚ ㎛ ㎜ ㎝ ㎞ № ü ◂ ▾ ▿ ▸ ▴ ◖ ◗ ρ ∀ ∃ α β γ δ ε μ φ π σ θ ∈ ∑ ⁿ Α Β Γ Δ Ε Ζ Η Θ Ι Κ Λ Μ Ν Ξ Ο Π Ρ Σ Τ Υ Φ Χ Ψ Ω α β γ δ ε ζ η θ ι κ λ μ ν ξ ο π ρ ς σ τ υ φ χ ψ ω Æ Á   À Å Ã Ä Ç Ð É Ê È Ë Í Î Ì Ï Ñ Ó Ô Ò Ø ÕÖ Þ Ú Û Ù Ü Ý á â æ à å ã ä ç é ê è ð ë í î ì ï ñ ó ô ò ø õ ö ß þ ú û ù ü ý ÿ Ā ā Ă ă Ą ą Ć ć Ĉ ĉ Ċ ċ Č č Ď ď Đ đ Ē ē Ĕ ĕ Ė ė Ę ę Ě ě Ĝ ĝ Ğ ğ Ġ ġ Ģ ģ Ĥ ĥ Ħ ħ Ĩ ĩ Ī ī Ĭ ĭ Į į İ ı IJ ij Ĵ ĵ Ķ ķ ĸ Ĺ ĺ Ļ ļ Ľ ľ Ŀ ŀ Ł ł Ń ń Ņ ņ Ň ň Ŋ ŋ Ō ō Ŏ ŏ Ő ő Œ œ Ŕ �� Ŗ ŗ Ř ř Ś ś Ŝ ŝ Ş ş Š š Ţ ţ Ť ť Ŧ ŧ Ũ ũ Ū ū Ŭ ŭ Ů ů Ű ű Ų ų Ŵ ŵ Ŷ ŷ Ÿ Ź ź Ż ż Ž ž ſ ʼn ⓐ ⓑ ⓒ ⓓ ⓔ ⓕ ⓖ ⓗ ⓘ ⓙ ⓚ ⓛ ⓜ ⓝ ⓞ ⓟ ⓠ ⓡ ⓢ ⓣ ⓤ ⓥ ⓦ ⓧ ⓨ ⓩ Numbers : ① ② ③ ④ ⑤ ⑥ ⑦ ⑧ ⑨ ⑩ ⑴ ⑵ ⑶ ⑷ ⑸ ⑹ ⑺ ⑻ ⑼ ⑽ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ⅰ Ⅱ Ⅲ Ⅳ Ⅴ Ⅵ Ⅶ Ⅷ Ⅸ Ⅹ ⅰ ⅱ ⅲ ⅳ ⅴ ⅵ ⅶ ⅷ ⅸ ⅹ ½ ⅓ ⅔ ¼ ¾ ⅛ ⅜ ⅝ ⅞ ₁ ₂ ₃ ₄ ¹ ² ³ ⁴ Japanese : ぁ あ ぃ い ぅ う ぇ え ぉ お か が き ぎ く ぐ け げ こ ご さ ざ し じ す ず せ ぜ そ ぞ た だ ち ぢ っ つ づ て で と ど な に ぬ ね の は ば ぱ ひ び ぴ ふ ぶ ぷ へ べ ぺ ほ ぼ ぽ ま み む め も ゃ や ゅ ゆ ょ よ ら り る れ ろ ゎ わ ゐ ゑ を ん ゝ ゞ ァ ア ィ イ ゥ ウ ェ エ ォ オ カ ガ キ ギ ク グ ケ ゲ コ ゴ サ ザ シ ジ ス ズ セ ゼ ソ ゾ タ ダ チ ヂ ッ ツ ヅ テ デ ト ド ナ ニ ヌ ネ ノ ハ バ パ ヒ ビ ピ フ ブ プ ヘ ベ ペ ホ ボ ポ マ ミ ム メ モ ャ ヤ ュ ユ ョ ヨ ラ リ ル レ ロ ヮ ワ ヰ ヱ ヲ ン ヴ ヵ ヶ ヷ ヸ ヹ ヺ ・ ヲ ァ ィ ゥ ェ ォ ャ ュ ョ ッ ー ア イ ウ エ オ カ キ ク ケ コ サ シ ス セ ソ タ チ ツ テ ト ナ ニ ヌ ネ ノ ハ ヒ フ ヘ ホ マ ミ ム メ モ ヤ ユ ヨ ラ リ ル レ ロ ワ ン゙゚ ㍻ ㍼ ㍽ ㍾ ゛ ゜ ・ ー ヽ ヾ 々 〒 〃 ※ 〆 Korean : ㄱ ㄲ ㄳ ㄴ ㄵ ㄶ ㄷ ㄸ ㄹ ㄺ ㄻ ㄼ ㄽ ㄾ ㄿ ㅀ ㅁ ㅂ ㅃ ㅄ ㅅ ㅆ ㅇ ㅈ ㅉ ㅊ ㅋ ㅌ ㅍ ㅎ ㅏ ㅐ ㅑ ㅒ ㅓ ㅔ ㅕ ㅖ ㅗ ㅘ ㅙ ㅚ ㅛ ㅜ ㅝ ㅞ ㅟ ㅠ ㅡ ㅢ ㅣ ㈀ ㈁ ㈂ ㈃ ㈄ ㈅ ㈆ ㈇ ㈈ ㈉ ㈊ ㈋ ㈌ ㈍ ㈎ ㈏ ㈐ ㈑ ㈒ ㈓ ㈔ ㈕ ㈖ ㈗ ㈘ ㈙ ㈚ ㈛ ㈜ ㉠ ㉡ ㉢ ㉣ ㉤ ㉥ ㉦ ㉧ ㉨ ㉩ ㉪ ㉫ ㉬ ㉭ ㉮ ㉯ ㉰ ㉱ ㉲ ㉳ ㉴ ㉵ ㉶ ㉷ ㉸ ㉹ ㉺ ㉻ ₩ ㉿ ー

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHAT DOES DESIRE DO TO YOU?

Does it:

a) cradle you

b) gut you

c) starve you

d) nourish you

e) inspire you

f) obliterate you

g) awaken you

h) hinder you

i) steal your warmth

j) pass through you

k) take you to a river

l) tie red string to your finger

m) clog your arteries

n) smell you

o) taste you

p) touch you

q) hear you

r) see you

s) understand you

t) turn into you

v) pay for your bus ticket

w) prepare you

x) wait for you

y) yield to you

z) echo your name

α) ignore you

β) tempt you

γ) famish you

δ) waste you away

ε) lie to you

��) strike you

η) steal from you

θ) betray you

ι) spread inside you

κ) sicken you

λ) anoint you

μ) undress you

ν) lead you to the minotaur

ξ) give you a mirror

ο) warn you

π) surround you

ρ) harden your joints

σ) shoot you with the wrong arrow

τ) rot your teeth

υ) build you a bench in the middle of the sea

φ) sedate you

χ) please you

ψ) love you

ω) win

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

bonus chapters: she always smiled and spouted pretty ideals

25+ y/o Megumi Fushiguro x female reader life after Megumi makes you his girlfriend! bonus chapters for this extended fic [14.5k] 18+ content. mdni

treasure .6k α kink discovery, fluff night out 2.3k β sfw, alcohol consumption urge .7k ⁺⋆ stripping, dry humping ft. 25+ yuji connect 1.4k ε m. oral friends? 1.8k Δ f. oral, m x m oral, doggy, spanking pretty pet .8k φ "kitten", soft dom, m. oral tied up 1.6k Φ bondage, fingering, f. oral, sex

megumi jjk m.list

likes, comments + reblogs appreciated!

#jujutsu kaisen#megumi fushiguro#megumi x reader#jujutsu kaisen smut#jjk smut#jjk x reader#female reader#jjk megumi#bonus chapters#navigation#masterlist

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

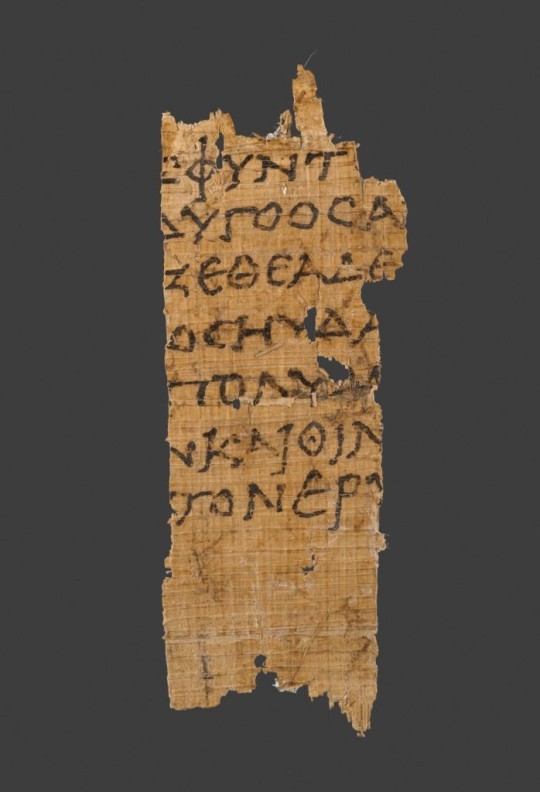

Which Greek letters are seen on this kylix?

Image description: Early form of the Greek alphabet on an Attic black-figure bowl

This kylix is part of the collection at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

Letters on the top side as far as I can tell:

Alpha Α

Beta Β

Gamma Γ (yes, it looks like a lambda, but that's how they used to write it)

Delta Δ

Epsilon Ε

Digamma Ϝ (super strange to see this- but maybe it's not written in Ionic)

Zeta Ζ (yes, it looks like an iota, again it's how it used to be written)

Eta Η

Theta Θ

Iota Ι

Kappa Κ

Lambda Λ (slightly older form again)

Mu Μ

Nu Ν

Omicron Ο

Pi Π

Rho Ρ (this one threw me off so badly, because why is that an actual R)

Sigma Σ

Tau Τ

Upsilon Υ (sometimes written like a v)

Chi Χ (but like a cross)

honestly have no idea what this extra O is standing for, maybe a miswritten Phi Φ? Although it's clear on the bottom side...

Psi Ψ (chicken foot type).

They are missing Xi Ξ and Omega Ω!

#I really wonder what time period this is from#and what dialect is seen here#because the letters are an interesting mix#ancient greek#greek language#greek alphabet#kylix#pottery#classics#dys blurbs

9 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Έχω ένα φόβο by Bad Movies from the album Στο λάκκο με τα φίδια.

#music#greek music#bad movies#bebis#geom#kimis#dimitris makris#kostas (bad movies)#giorgos tachtsidis#theodoros bournas#george taxtsidis#video#music video#oracle art vision#george papaioannou#sophia voulala

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, here u are nitka na temat: "jak czytać alfabet grecki?"

Alfabet grecki składa się z 24 liter:

α,β,γ,δ,ε,ζ,η,θ,ι,κ,λ,μ,ν,ξ,ο,π,ρ,σ;ς,τ,υ,φ,χ,ψ,ω.

A więc zaczynamy: Α,α-alfa [a]

Β,β-beta[b]

Γ,γ-gamma [g]

Δ,δ- delta [d]

Ε,ε-epsilon[e;krótkie]

Ζ,ζ-dzeta [dz]

Η,η-eta[e;długie]

Θ,θ-theta [th]

Ι,ι-jota[i]

Κ,κ-kappa [k]

Λ,λ-lambda[l]

Μ,μ-mi [m]

Ν,ν-ni [n]

Ξ, ξ- ksi [ks]

Ο,ο-omikron [o;krótkie]

Π,π-pi [p]

Ρ,ρ- ro [r]

Σ,σ(na początku i w środku wyrazu), ς(na końcu)-sigma [s]

Τ,τ-tau [t]

Υ,υ-ypsilon [y]

Φ,φ-phi [f lub tak jak czytali starogrecy ph]

Χ,χ-khi [ch lub tak jak czytali starogrecy kh]

Ψ,ψ-psi [ps]

Ω,ω-omega[o;długie]

10 notes

·

View notes