#[ 🌟 family 🌟 ]

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I think I will forever be fucked up over the treatment of the wolf brothers in Sweet Tooth s3. They were kids.

#🌟 Ten Talks#I just got around to watching it#and let me just say#I will never stop thinking about them#they were treated like actual hunting dogs by their own family#since just after they were born#I don’t care how much Rosie loved them you do not do that to a child#let alone your own four sons#sweet tooth#sweet tooth netflix#sweet tooth season 3

359 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chat how are we feeling

and by chat, I do mean the 5 Bittergiggle fans left after 6 months

#bittergiggle#bitterggiggle garden of banban#garten of banban#Garter of ban ban 7#Went from a family man to rambling man - 🌟#<— new tag for when I ramble on about dumb stuff#If you get the reference you get a gold star sticker#queen bouncelia#is here too ig#I know this game is so stupid but I’m hyped for the Bittergiggle return#It’s slop but like in the good way

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

HecuPriam 👑🌟 (edit)

I cried while making this.

Art credit: literallyjusttoa, dilfaeneas, kebriones, wolfythewitch

#Hecuba#Priam#hecuba of troy#priam of troy#Trojan war#Iliad#the iliad#epic cycle#tagamemnon#Priam x Hecuba#Hecuba x Priam#HecuPriam#👑🌟#angst#trojan family#greek mythology#edit#canon ship#W/M

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

drawing in apps that aren’t for drawing >>>

#katamari#katamari damacy#katamari prince#katamari cousins#drew this in. pages? i think?#i just loveee the texture of the crayon brush its everything to me#🌟#family#my art#happy new year! heres to a lot more art and such#hopefully </3

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Emperor's New School || one gifset per episode ↳ Episode 03 ☀︎ Kuzco Fever

#disney#the emperor's new school#disney channel#disneyedit#disneychanneledit#disneynetwork#usereasthigh#kuzco#chicha#tipo#chaca#emperor's new groove#🌟#my edits#gifs#i giffed this whole scene just for that last line tbh#i may have mixed feelings about the show but i love this family <3#also LOVE that chaca basically knew what was up immediately. she's so funny.

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

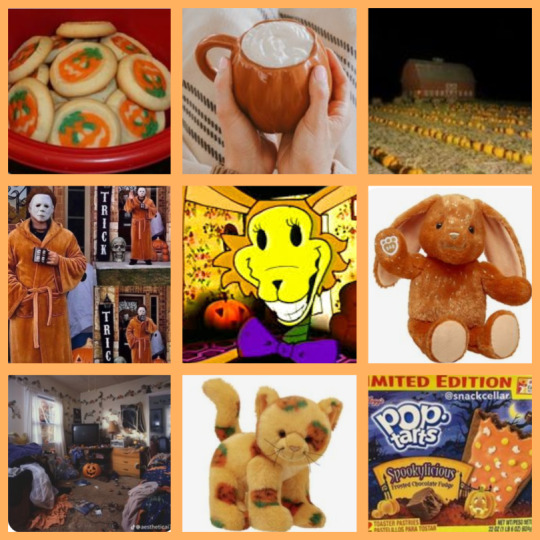

Moodboards of my f/os as caregivers!

Headcanons:

Movie William as a CG:

Takes me to to Freddy's for pizza and cake.

After it has to close, has a special room set up for me.

Keeps my favorite snacks.

Takes me to arcades.

Watches his mechnical work.

Goes nonverbal also as a caregiver, uses flashcards and such with each other.

Secretly enjoys baking, so we bake together.

THE CUDDLER!!!!

TFC William as a CG:

Kinda similar to Movie verse.

Tries to help figure out whats going on with me medically.

Is very gentle when it comes to doctor care.

Cannot do much due to pain + Disabilities, but does the best he can by providing a comfortable set up, buying things for comfort.

Has a set up in his bedroom so we can stay near each other and watch over each other.

Likes it when i play doctor for him.

Can do simple things, like play with my hair.

Pumpkin Rabbit as a CG:

FINALLY a baby. Him and his wife always wanted a Baby.

Teaches Older me how to hunt, but as regressed he mainly carries me while on his hunt, especially since I'm quiet.

Buys me little treats when Sha / Rachel / Mama doesn't feel like cooking.

Takes me pumpkin picking and carving.

Reads bedtime stories.

Witch Sha / Rachel as a CG:

Quite emotional about having a little one finally.

Loves when i help her with baking. Lets me lick the frosting.

When Pumpkin Rabbit goes on hunts, she wraps me in a blanket and we watch movies in the couch.

Sings lullabies when its bed time, both tuck me in.

the Cuddler 2

Bandit and Chili as CGs:

This is more based on a regressor oc rather than an adult being a regressor ! ( so a kid ) /gen

I'll write Bluey and Bingo as siblings one day <3

Bandit Claims to be the "cool parent" ( Chili is just as cool )

Bandit does lean more on the sweets and junk food, while Chili leans on healthy foods, but they both make sure i get enough.

Turns the spare room into my room. Bandit buys decor and Chili helps decorate it. ( extra blankies, stuffies etc ).

Chili teaches me new crafts and such! Helps me with my crochet and kandi.

them and the girls love playing games! So we have board game nights.

Chili helps me make it fun to help clean up on days i have spoons to clean, and on days i have no spoons but feel like helping, she gives me minor activies to do ( aka pretend cleaning ).

Silco as a CG:

sneaks us somewhere to play in cleaner waters.

Mini parties with Jinx

Always sneaking me objects or snacks like its SOME big secret but its really just to get me to laugh or feel apart of the mission

when shit is serious he often tucks me away in my room if i cannot join him or Jinx.

Jinx sometimes gets to stay with me and we make up games.

We enjoy calmer games when its just me and Silco. I spy, or just naming things with a start of a letter.

Endless Art supply for me ( and Jinx because we both love art when regressed ).

Princess Celestia as a CG:

Plays Royalty with me. Sometimes lets me use her crown.

Loves taking me for a stroll in the early mornings.

Knows her beautiful sun can be too hot at times, so she brings me mini fans or buys ice cream sometimes.

Often takes me with her on her trips unless its too busy or dangerous.

Loves to make me teas or coffee she knows i enjoy.

Sometimes we go to a beach together! We find sea shells :)

btw i always see my fictional caregivers as flips unless i say otherwise!

Unless we're moots please don't tag William as f/o ! Okay to tag the rest as f/o or caregiver or take inspiration. Okay to use moodboards as long as you don't claim you edited them together! /lh

#agere caregiver#familial fictional other#queerplatonic f/o#platonic fictional other#princess celestia#Pumpkin rabbit#Witch sha#Bandit heeler#Chili heeler#Flip agere#Permaregressor#Self ship#Moodboards#『 William Afton: 🪦🧪 』#『 Springtrap: 🫀🕯 』#『 Pumpkin Rabbit: ☻️🎃 』#『 Witch Sha: 🔮🐏 』#【 Abyss: 🌊🌟 】#『 Petre: 🧸🍼 』#『 Age Dreaming: 📓🎮 』#『 Caregiver: 🩺🫂 』#『 Permaregressor: ♾️💤 』#『 Age Regression: 🎮🧩 』#Agere

29 notes

·

View notes

Text

And this feeling has got a window 'Til I'm numb, 'til I am blissful 'Til the sum outweighs the mental 'Til the blood of both is my limbo

fellas is it cringe to draw oc refs for your own fic? no? great. i finally did official postassim saints refs because i love them :3

the saints are the brainchild of me and my lovely wife @bean-market-mafia and you can find the fic we wrote together (linked above). anyways i love the saints

#i did futhark vesta and kelpie while watching oppenheimer with my family LMAO#black clover#bc oc#doleur unuis#ares deuteros#stella tridentarius#futhark tettares#vesta quintus#kelpie sextus#saintverse au#🌟 the blood of both#funky sea art#🪲#alex my beloved#the song is hollow by cloudeater btw

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

PS: I couldn't believe my eyes when I found this photo!

#Queen Victoria smiling

#united kingdom#queen victoria#uk monarchy#british royal family#england#rare photos#brf#old photos#british history#historical figures#british monarchy#queen#late 1800s#ukfanpage#colorized#RARE🌟

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

I turn 15 in two months 💖💖💖

#Only cool thing about that is that I only have to suffer dysfunctional family dinner for 3 more years🌟#ferf yapping#afternoon quil#shitpost#memes#15

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

One Knee at Dinner

Desc: Asta comes to a family dinner on board the Astral Express, because she has a surprise for her girlfriend, Miya. Arlan and Peppy are there too.

(divider credit to @/animatedglittergraphics-n-more) (fic is utc as usual)

"Dinner's ready!" Miya calls, pulling off her noise-canceling headphones now that the meal is finished. She washes her hands, before slipping her fishnet gloves back on. The other members of the Express come trickling into the room, with the exception of one - their father figure.

Miya pokes their head around the corner, watching as the door to the Express slides open. Asta comes in, followed by a confused-looking Arlan and an excitedly-bouncing Peppy. Peppy seems to notice Miya across the room immediately, barking excitedly and tackling it to the ground. Miya giggles, lifting a hand to scratch fondly at the dog's white fur. The dog just barks excitedly, licking Miya's face and barking.

Arlan comes over, whistling sharply to get Peppy to jump off of Miya. He then gives his sister a hand up, which they gratefully accept. They laugh softly, saying, "Thanks, Arlan. Did you and Asta come for dinner?"

"Mhm. It was Asta's idea, though I believe that Mr. Yang invited her." Arlan replies - which given how deep in conversation Mr. Yang and Asta are, that seems highly likely.

Arlan joins the Express Crew in the dining room, Peppy trotting loyally behind.

"Dad, Astie, it's time for dinner! C'mon!" Miya calls. Both of them jump, Asta's face burning red. She stammers out, "Oh, s-sorry love! We're coming!"

Miya ducks back into the dining room to set the table, humming softly as he gets everything settled on the table. Dan Heng and Himeko pull two extra chairs up to the table for the guests, and Peppy skulks around under the table while begging from anyone who seems like they'll drop something.

Miya chatters animatedly the entire time, enjoying having her girlfriend and brother over for dinner.

What they don't notice, however, is when Asta drops something under the table. Peppy picks it up, giving it to Arlan, who pockets it.

After dinner, Asta fidgets in her bag, growing more and more frantic. Mr. Yang shares a glance with Asta before he catches the attention of March 7th, Dan Heng, and Himeko, getting the other three Express members to clean up the dishes and leftovers from dinner.

"Lady Asta, you dropped it. Peppy picked it up and gave it to me. Here you go." and then Arlan presses something into Asta's hand, before whistling to get Peppy to follow him out of the dining room.

This leaves Asta and Miya, alone in the dining room.

Suddenly, Asta is flustered - more flustered than Miya's ever seen her.

"Well... here we are. Here we are," Asta says, flushed bright red. The thing Arlan had returned to her is being twisted in her hands, while Miya just stands there, waiting.

Suddenly, Asta drops down to one knee.

She reveals the item in her hands - a red velvet box.

"Awe, that's a cute box," Miya says, before it suddenly sinks in. When it finally hits, Miya's face grows just as red as Asta's. Finally, Asta speaks again, her voice shaking just a little.

"Miya... will you marry me?"

She opens the box, revealing the contents of the box. A ring with a rose gold setting. The main stone is a gorgeous ruby, with smaller sapphires dotted around the setting.

Miya can only stare for just a minute, blushing and stammer as it tries to answer.

"I... I..."

Asta looks up at him with hopeful eyes, which helps Miya find his voice.

"Y-yes! Yes, oh, Aeons, yes! Of course I'll marry you!"

Asta leaps up, sweeping her into a dip and a kiss. When they finally pull apart, Asta slips the ring onto Miya's finger.

Cheering from the doorway to the kitchen makes them both look up. The rest of the Express stands in the doorway, where March 7th is cheering for them. Dan Heng is smiling, a real one. Himeko also gives them a fond grin, and Mr. Yang nods at Asta with a smile. In the other doorway, Arlan is smiling too.

Quietly, Asta tells her, "I did get Mr. Yang's permission, since I know how important it is to you. He and Arlan were the only ones who knew."

"I had to prevent her from blowing too much money on your engagement ring, by the way!" Arlan interjects, which causes Miya to snicker. Asta flushes with embarrassment, burying her face in Miya's shoulder.

After a few moments, Mr. Yang speaks up. "I tried my hand at making a dessert for the occasion. It's nothing as fancy as what you make, little bird, but I think I did well enough," he says.

Miya smiles at that, saying, "Let's dig in, then."

So they settle down as Mr. Yang brings out the dessert he'd made, while Miya and their fiancée get congratulations from everyone else.

And now they can call Asta their fiancée. Holy shit, that's their fiancée.

And she's just getting happier and happier as the days go by.

"...I love you, Astie."

"I love you too, Miya."

#selfship writing#self ship writing#s/i | miya “debonaire��� starshine#🛰️🌠 every star is a miracle | asta#ship | the stars will always remember us#⚡🩹 lightning in the dark | arlan#🐾🌟 space station puppy | peppy#i cant be assed to tag the entire express crew so you just get the general tag lmao#🌌🚅 a trailblazing family | astral express crew#actually welt talks n stuff so ill tag him#🖋🎞 our dear elder | welt yang#💛❤️💜 brought together by fate 💜❤️💛

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Olivia Combs Ref Sheet!!

I finally have her ref sheet done!!! Sorry for not making one sooner!!

Now that I have a ref sheet for her, I can talk about her more! I’m gonna copy paste her info from my notes app lol

-23

-Female

-Irish American

-5’8” (The same height as Jack!)

-Nickname: Oli

-Works in the Film Department as a reel inspector. She basically goes over all the film reels and checks for errors or problems before they can be sent off to air (I’m not sure if this was an actual job back then, but it seems fitting. Joey was a perfectionist after all).

-Gets along really well with Norman Polk. Basically besties, as they both relate to being exhausted and fed up with the stuff Joey pulls.

-Gets along really well with Jack Fain as well. She enjoys spending time with him, since his positivity balances out her aloof nature.

-Gets along really well with Sammy Lawrence. She likes to mess with him sometimes, but only because she feels like he needs to lighten up a bit. They both get along because they are pretty stubborn.

-Rivalry with Lacie Benton. This studio ain’t big enough for two girls with mechanic skills. They like to talk smack about each other. They got into a fight in the basement once, which Sammy promptly stopped Wally from getting involved in (dude wanted to break it up).

-Pretty neutral relationship with Thomas Connor. They respect each other, but they don’t really talk much.

-Enjoys Wally Franks company. He’s a funny guy, and they would definitely get drinks together after work. Their relation went down the drain after Wally became the Ink Demon and she came back to the studio. She’s trying her best to make him snap back to reality.

-Pretty good friends with Shawn Flynn. They’re both Irish, so they like similar things there, and love talking about their homeland.

-Neutral relationship with Susie Campbell. She exists, not much else to say about it. Olivia does like her voice though. Aware that Sammy loves he, and likes to tease him about it. After she comes back to the studio, she thinks she’s insane, but willing to try and help her.

-Doesn’t like Joey Drew at ALL. Would probably murder him in the streets if he wasn’t signing the paychecks. Hates him even more after realizing what happened after she left.

-Didn’t really know Henry. Knew of him, but very little about him. They would probably get along pretty well though. During the second part of the AU (coming back to the studio) they tend to be a bit at odds due to Henry not trusting Norman, Jack, and Sammy, and her not liking how he’s trying to be leader all the time. They’ll work it out though.

-Neutral Relationship with Bertrum Peidmont. They know of each other, but thanks to working in completely different departments, they don’t talk much. She doesn’t really like how stuck up he is though. He is aware of her and Lacie’s rivalry.

-Neutral positive relationship with Grant Cohen. They understand the feeling of being screwed over by Joey, so they bond over that. She does like to make fun of him for being British though.

-Quit before everything went down hill and Joey started messing with the ink on a larger scale.

-Surprisingly good at mechanics. She often fixes miscellaneous things around the studio just because she can, or because she wants to make them run better.

-Might have Trypanophobia, the fear of needles. Spiders, heights, the dark, she’s good with those, but she draws the lines at needles. It’s not really plot important, but I think it’d be funny to see her absolutely getting all antsy when the crew is trying to deal with a very insane Susie.

-Definitely the type to hold grudges. She will always remember when you wronged her. Even if it’s petty, she’ll remember.

-Likes to call people by nicknames or shortened versions of their name sometimes. Like, she would definitely call Norman; Norm, and Sammy; Sam. It’s just her little way of showing she cares.

-She has a very slight Irish draw to her words. She sounds American, but tinges of her Irish Accent show through a bit.

-Favorite kind of music is definitely swing. She’d probably lose her crap if she ever heard electro swing. In modern times, she would probably really like anything by Will Wood.

-Enjoys bitter and savory foods. While she does like sweets, she loves the kick salt gives. Her favorite food is probably pretzel bites, thanks to their filling nature and are easy to eat on the job.

-Takes her coffee battery acid black. If she can’t see her reflection in the swill, then it wasn’t made right. Although, she probably wouldn’t mind a bit of milk in it on some days.

-Enjoys horror/thriller movies.

-Her favorite animals are probably bats and cats. Yes, a very dark and edgy choice, but she just thinks they’re slick. In addition, she would also really like mudskippers.

-Favorite kind of weather is rainy. She likes it when it’s just lightly raining, and she doesn’t need an umbrella. However, she also loves it when it’s just absolutely pouring outside, like to the point where you could think it’s night outside.

-Her eyes light resistance is kind of jacked up at times. Working in the pitch dark of a studio room with no light other than a projector running a cartoon definitely does something to your eyes. It takes her a bit to adjust to the light whenever she comes out.

-She’s prone to migraines, since the sudden shift from pitch black to a lit room when she leaves her workstation hurts her head.

-She came back to the studio 5 years later (Yeah, it’s supposed to be 30, but this is my AU lol) due to her crushing guilt finally getting the best of her. She felt bad for quitting and leaving her friends to deal with Joey, since literally a year after she left, Joey screwed over everyone in the studio.

-Has a light scar across her shoulder from being a stupid kid.

-Hates anything frilly, like a dress or skirt. She would probably throw a fit if Susie offered to do her hair for one of Joey’s parties. She values comfort over style any day.

-Voice Claims (What I think she would sound like, or as close as I can get!):

Sargent Calhoun (Wreck It Ralph)

Mai (ATLA)

Rosa Diaz (Brooklyn 99)

Sorry if this is really long. I just have a lot to say about her!! If you read through to the end, you are a trooper lol

#batim#bendy and the ink machine#batim au#olivia combs#batim oc#reference sheet#oc reference#oc ref sheet#oc info dump#oc info#Eevee’s Art - 🌟#Went from a family man to rambling man - 🌟#This falls under both tags this time lol#long post#I’m sorry if this comes off as cringey I try my best not to

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

your_home_숩 ☆

#thank you for coming home before the year ends and giving us update on how you’ve been🖤#you have no idea how much that means and how happy i am to hear from you🥺#our captain‚ our forest and our warm home🤎🌳🏡 we love you and we’ll wait for you as always so take all the time you need‚ okay?!#i knew that he was home with his family probably having good time with them but hearing it from him really did gave me a relief😭#like hearing from him that he sleeps well‚ eats home cooked meals‚ takes a walk everyday‚ looks at the sky and feels#spends time with his family‚ hearing from him that he’s healthy and happy and putting efforts to be healthier🥺nothing could make me happier#i missed you sOooOooooo much my love🥺 but i can wait you as much as you need and the passing time only makes my love grow bigger🥺#i hope he keeps having healing time with his loved ones‚ hope he never stops taking walks and looking up to the sky..♡#sighs the fact that he immediately brought happiness and brightness to my day...! and this will keep me going till they come back as 5 🙂↕️#love you soobie boobie doobie foobie🥺✨️💝💖💗💓🌟💞💕#tu’s moa diaries (tu’batu wari wari) 🌟

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

I always remind Comet and Catwoman's relationship to be of Duchess and Marie.

Comet does love cats although her most favourite animal is rabbits.

#🐈⬛️cat mama🐈⬛️ (familial)#🎨flicky's drawings🎨#🌟comet🌟#🐈⬛️catwoman🐈⬛️ (familial)#💙familial f/o💙#parental f/o#the batman 2004#a motherly cat and her kitten she wishes to have

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

THIS TEAM IS SUPER UNOPTIMAL BUT IT MAKES ME HAPPY TO USE ^_^

#Q#💫.jpg#💫.txt#『🌟』 volo#GIRATINA#familie... except our great great grandaughter doesn't give a fuckk#POKEMAS

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

At present, it is standard among practically all communities to fête the family as a bastion of relative safety from state persecution and market coercion, and as a space for nurturing subordinated cultural practices, languages, and traditions. But this is not enough of a reason to spare the family. Frustratedly, Hazel Carby stressed the fact (for the benefit of her white sisters) that many racially, economically, and patriarchally oppressed people cleave proudly and fervently to the family. She was right; nevertheless, as Kathi Weeks puts it: “the model of the nuclear family that has served subordinated groups as a fence against the state, society and capital is the very same white, settler, bourgeois, heterosexual, and patriarchal institution that was imposed by the state, society, and capital on the formerly enslaved, indigenous peoples, and waves of immigrants, all of whom continue to be at once in need of its meagre protections and marginalized by its legacies and prescriptions” (emphasis mine). The family is a shield that human beings have taken up, quite rightly, to survive a war. If we cannot countenance ever putting down that shield, perhaps we have forgotten that the war does not have to go on forever.

This is why Paul Gilroy remarked in his 1993 essay “It’s A Family Affair,” “even the best of this discourse of the familialization of politics is still a problem.” Gilroy is grappling with the reality that, in the United Kingdom as in the United States, the state’s constant disrespect of the Black home and transgression of Black households’ boundaries, as well as its disproportionate removal of Black children into the foster-care industry, understandably inspires an urgent anti-racist politics of “familialization” in defense of Black families. Both the British and American netherworlds of supposedly “broken” homes (milieus that are then exoticized, and seen as efflorescing creatively against all odds), have posed an obstinate threat to the legitimacy of the family regime simply by existing, Gilroy suggests. The paradox is that the “broken” remnant sustains the bourgeois regime insofar as it supplies the culture, inspiration, and oftentimes the surrogate care labor that allows the white household to imagine itself as whole. As a dialectician, “I want to have it both ways,” writes Gilroy, closing out his essay. “I want to be able to valorize what we can recover, but also to cite the disastrous consequences that follow when the family supplies the only symbols of political agency we can find in the culture and the only object upon which that agency can be seen to operate. Let us remind ourselves that there are other possibilities.

There are other possibilities! Traces of the desire for them can be found in Toni Cade (later Toni Cade Bambara)’s anthology The Black Woman, published in America in 1970, not long after the publication of the US labor secretariat’s “Moynihan report,” The Negro Family: The Case for National Action. The open season on the Black Matriarch was in full swing. And certainly not all of the anthology’s feminists, in their valiant effort to beat back societal anti-maternal sentiment (matrophobia) and the hatred of Black women specifically (more recently known as “misogynoir”), make the additional step of criticizing familism within their Black communities. But one or two contributors do flatly reject the notion that the family could ever be a part of Black (collective human) liberation. Kay Lindsey, in her piece “The Black Woman as a Woman,” lays out her analysis that: “If all white institutions with the exception of the family were destroyed, the state could also rise again, but Black rather than white.” In other words: the only way to ensure the destruction of the patriarchal state is for the institution of the family to be destroyed. “And I mean destroyed,” echoes the feminist women’s health center representative Pat Parker in 1980, in a speech she delivered at ¡Basta! Women’s Conference on Imperialism and Third World War in Oakland, California. Parker speaks in the name of The Black Women’s Revolutionary Council, among other organizations, and her wide- ranging statement (which addresses imperialism, the Klan, and movement- building) purposively ends with the family: “As long as women are bound by the nuclear family structure we cannot effectively move toward revolution. And if women don’t move, it will not happen.” The left, along with women especially of the upper and middle classes, “must give up ... undying loyalty to the nuclear family,” Parker charges. It is “the basic unit of capitalism and in order for us to move to revolution it has to be destroyed.”

Forty years later, the British writer Lola Olufemi is among those reminding us that there are other possibilities: “abolishing the family...” she tweets, “that’s light work. You’re crying over whether or not Engels said it when it’s been focal to black studies/black feminism for decades.” For Olufemi as for Parker and Lindsey, abolishing marriage, private property, white supremacy, and capitalism are projects that cannot be disentangled from one another. She is no lone voice, either. Annie Olaloku-Teriba, a British scholar of “Blackness” in theory and history, is another contemporary exponent of the rich Black family-abolitionist tradition Olufemi names. In 2021, Olaloku-Teriba surprised and unsettled some of her followers by publishing a thread animated by a commitment to the overthrow of “familial relations” as a key goal of her antipatriarchal socialism. These posts point to the striking absence of the child from contemporary theorizations of patriarchal domesticity, and criticize radicals’ reluctance to call mothers who “violently discipline [Black] boys into masculinity” patriarchal. “The adult/child relation is as central to patriarchy as ‘man’/‘woman,’” Olaloku-Teriba affirms: “The domination of the boy by the woman is a very routine and potent expression of patriarchal power.” These observations reopen horizons. What would it mean for Black caregivers (of all genders) not to fear the absence of family in the lives of Black children? What would it mean not to need the Black family?

Sophie Lewis in “Abolish Which Family?” from Abolish the Family: A Manifesto for Care and Liberation, 2022.

206 notes

·

View notes

Text

number 1 advice for taking exams ummm have a glass of beer beforehand

#i mean OBVIOUSLY eat well too but this is the important bit. the grandpas of my dad's side of the family would URGE me#to mention the holy balkan medicine which is 🌟rakijica🌟 so i am doing that too lol#jo in the tardis*

17 notes

·

View notes