We hold in our hands the game controller of our lives, and no; there is no turbo function! So what are we to do with it? Play of course :)

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Creativity in Uncreative Games

I’m a sucker for a level editor. Give me the worst game in the world but bundle in a user-friendly level creator and I’ll eat it up, which explains why I adore LittleBigPlanet so much. I am a creative person so having an outlet within the games I love fulfils two of my desires at once without having to know how to write code, etc.

But even in games that don’t facilitate your creative enthusiasm in such a straightforward manner there is the opportunity for extra-curricular fun. Take the lore-heavy Dark Souls 3, a game built on the idea of repetition both thematically and mechanically (which is a whole article in itself), but which has a very traditional structure of beat the bosses, progress through the game, win (sort of). But in being able to choose what armour you wear players all over the world have been having fun recreating their favourite celebrities, characters or even just making the most obscene and crazy avatars they can think of. The results are amazingly varied and accomplished but always fun.

Or take Super Mario 64, an endless source of data mining and speedrunning to this day, but within which players have created their own minigame called The Green Demon Challenge wherein you reveal the 1UP mushroom on a particular stage which will then chase you and make you absorb it. The challenge is to collect all the red coins on the level before the mushroom catches up with you. Again, this is a game with a very defined set of rules and no ‘make your own adventure’ mechanic whatsoever, and yet with a little ingenuity players have managed to concoct an original idea within its structured framework.

I recall myself playing Command & Conquer: Tiberium Sun and enjoying one level of the campaign in particular where you could defeat the enemy without triggering the level to finish. I then messed around with the level creating, in my own head, a unique scenario that I acted out with forced attacking on my own units and so forth. Or when my friends and I played Small Soldiers and we’d activate the invincibility cheat in multiplayer then proceed to, again, act out our own scenarios using the assets we had. Of course, back then ironically my attention span was much better than it is now and...

David

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Greatest Moment in Videogames

1. Final Fantasy VII

Aerith dies

For me it couldn’t have been anything else. Maybe it’s just because it was the first time that a videogame made me cry but these events stick with you on a greater level than merely being a recollection. I don’t recall being particularly attached to Aerith, Cloud or any of the other characters but something about the whole scene, the nature of her death as a sacrifice, the distress of her friends, and that goddamn music, made me stop what I was doing and appreciate that I was not just playing a game but experiencing it.

But it wasn’t just emotional, I’d also never played a game before where a major character was suddenly taken away from me and all my progress with them nullified. This is a world built on the notion of extra lives, after all, so to be told that this character whose story and connection to the world is integral to your journey is now gone forever was a hard notion for me to accept.

From a narrative point it also gave my characters a much more personal bond. Before they were a ragtag team of misfits and rogues, but now all of a sudden they had been brought together by a tragedy that connected them to each other in a way that would never have been possible otherwise. After all, saving the world and defeating evil is a very impersonal quest. Now they, and you, have a reason and a purpose beyond fulfilling the object of the quest: to honour Aerith’s memory and defeat Sephiroth.

And when the remake comes around, no matter what else they change, they absolutely must not tarnish the memory of this wonderful moment in gaming history by allowing you to bring Aerith back from the dead. She is gone. The impact of that realisation hit me like a tonne of brick the first time I played it and to undermine it would be ruining a beautiful moment of my childhood.

And that is why the death of Aerith is, for me, the greatest scripted moment in videogames.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Greatest Narrative Moments in Videogames

2. The Last of Us

Joel lies to Ellie

To have a final line have so much impact is astounding. The confidence that Naughty Dog had to hinge a universally-praised game on its dying breath can only have come about with the knowledge that it would either ruin an otherwise near-perfect game or raise it to astronomical levels of narrative competence. Luckily for all of us, it was the latter.

Joel’s journey from a cold and insular man to a reborn father figure is wonderful to experience and it pleases us to see him comfort Ellie in her darkest moments while also feeling joy like he hasn’t felt in a long time. It’s a credit to the acting that you can hear it in his voice whenever his daughter Sarah is mentioned that the pain is still very real and the only reason he keeps Ellie at a distance is to stop him ever having to feel that again. So to overcome that must take some powerful emotions indeed.

But it takes a certain amount of hardship and heartache to lie to the ones you love the most. Ellie is the cure for mankind in the games zombie apocalypse but in order to process it she has to die under a surgeon’s knife. Joel can’t accept this, not after having built himself up again to love another like Sarah, so he springs Ellie from the hospital and kills the one person who would be determined enough to find her again. All the while Ellie is unconscious, but when she wakes up Joel lies to her. He tells her there is no hope for a cure and that she was just another red herring.

Then a while later, as they reach their final destination, a new home for them to settle down in, Ellie asks him a question she has clearly been thinking about for a long time. She asks Joel to swear that everything he told her was true.

He takes a breath: “I swear.”

Ellie pauses. “Okay.”

Then the game ends.

The emotionally hollow feeling that comes in that moment when the title appears on the screen is immense. You’ve come to love Joel, even admire him. He’s been through and done so much for others that you are happy when he finally starts coming to terms with the bond he shares with Ellie, but to make such a selfish decision, even for the indelible love a father has for his daughter, leaves you cold inside. And you ask yourself, ‘what would I have done?’ Granted, the fate of the world is at stake but the power of love extends beyond the bounds of reality. Could you say with all honesty that you would have allowed yourself to suffer the crushing loss of another friend, another ally, another child?

There is no right answer.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Greatest Narrative Moments in Videogames

3. Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic

You are Revan

It’s all in the title: throughout the majority of the game you have been on the trail of the old Sith Lord Revan, who is missing. Though his true fate remains a mystery those in the know suggest heavily that he is dead but doubts remain. Meanwhile your own personal quest sees you gathering power and allies at a steady rate, regardless of your light or dark path, and references to your potential are plentiful. It all seems rather par for the course, you being the main character and whatnot.

But then you finally encounter the antagonist Darth Malak, face to face, and what he reveals is shocking. It turns out that you were Revan all along, suffering from a Jedi-induced amnesia in the hope that you would return to the light and lend your power and tactical genius to the Republic instead of against it as you previously were.

From this point on your decisions have a greater sense of weight and every decision you’ve made comes into question. Those who are truly into the roleplaying aspect may find themselves going against their chosen path in light of this revelation because of the impact it has on the story. It also works because the game constantly treads the fine line between cliché and originality by feeding you enough to make you wonder but not so much that you guess the outcome before it’s happened.

It may also have been such a successful twist because it existed in an age when twists weren’t so commonplace, or maybe because it reflected another very famous one. But even if you saw it coming, it’s still satisfying to see a game develop around a character whose past, though a mystery, is purposefully misleading to both the in-game characters and the player.

0 notes

Text

The Greatest Narrative Moments in Videogames

4. Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater

Killing The Boss

A stunning locale and a fight that tests all of your skills and reflexes, the fight with The Boss of Metal Gear Solid 3 is exactly what a final boss should be. Taking place in a field of shivering white flowers, your task is to kill your mentor and the closest thing you’ve ever had to a mother. But she isn’t making it easy. She’s clad all in white to blend in with a powerful machinegun and unparalleled close-quarter combat techniques.

The fight is a fantastic experience because it allows you to employ any of the tactics you’ve used to complete the rest of the game: you can shoot her from afar, lay traps, camouflage yourself, or even, with perfect timing, take her on in hand-to-hand combat. The fight is easier if you’ve perfected your abilities just as the fictional character herself has taught you all along.

But the moment of brilliance comes after the fight, when she’s down and out and waiting for the final blow. The cutscene plays out where she laments her failures, reveals some truths and eschews some philosophy, all standard endgame dialogue. Then Snake holds the gun to her head, but nothing happens. You wait, but still nothing. And just when you start to get impatient, remembering Kojima’s penchant for long-winded cinematics, you realise that the final pull of the trigger is down to you. The game cannot advance until you kill The Boss. Not the game, not your avatar Snake, you the player. Putting such a personal emphasis on ending a character you’ve built emotional connections and pathos with is a fantastic touch.

And the gunshot rings out in the silent field while the flowers turn red. It is poignant and oddly subtle for a Kojima game, but works all the better for it.

0 notes

Text

The Greatest Narrative Moments in Videogames

5. Bioshock

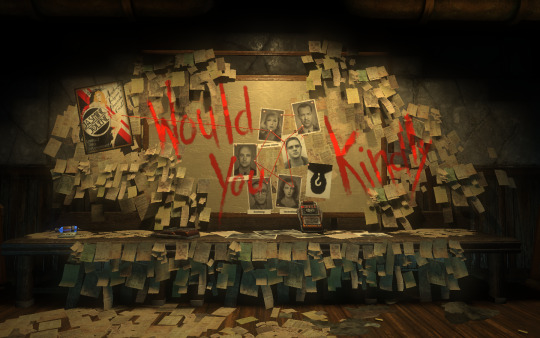

Would you kindly?

Bioshock is full of great moments: the scene that greets you as you emerge from the plane wreckage; your approach to Rapture itself; your first encounter with a Big Daddy; Dr. Steinman’s mad rant; the dentist; Cohen’s masterpiece; Atlas and Fontaine; becoming a Big Daddy. But the standout moment for many is when you realise that your involvement in the game hasn’t been an accident, and that with three simple words you have been manipulated and bent to one man’s will.

Having gone this far believing your actions to be a result of circumstance and your own will to survive, to be told you have never had a choice in the matter is disquieting. You have been told that Andrew Ryan is a menace and a tyrant, a man driven to insanity by his desire to build the perfect world, so killing him at this point seems entirely justified. But you never expected to be doing it at his own command.

As he tells you, in his mocking way: ‘a man chooses, a slave obeys.’ Even at the end, when he holds his own fate in his hands, he is so devoted to his convictions that he would rather order you to kill him, use you as a tool, a slave, than die by another’s will. And you are forced to watch as this man, who has complete control over you, hands you the device of his own demise and repeats his mantra as you club him to death. It’s a chilling moment in a game that never struggles to ask you important questions or hold a mirror up to society.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Greatest Narrative Moments in Videogames

6. Red Dead Redemption

John Marston dies

Epic narratives often suffer from unsatisfying conclusions, loose ends or endings that are just too happy, too perfect to be good. No fear with Red Dead Redemption, a modern epic that allows you to live John Marston’s final days as he attempts to atone for his sins and make amends for his past. In the end, it seems, to no avail.

You served the people, paid your debts and did what the corrupt government officials demanded from you, but in the end you’re an outlaw and there’s only one ending for an outlaw. But the brilliance of your final moment as John Marston is in giving you false hope, by returning control to you even as you’re faced with insurmountable odds.

There’s dozens of armed men in front of you. There’s nowhere to run. Dead Eye Targeting activates and suddenly you realise you can aim and shoot. You set up your shots, starting slamming back the hammer on your revolver. You take a few of them down. You think about where to aim next...and then you die. The hail of bullets tears you to pieces and there’s nothing you can do about it. But for that one graceful moment, when the world slowed down to witness John Marston’s final moments, you dared to hope.

But this is the wild west. There’s no hope out here.

0 notes

Text

The Greatest Narrative Moments in Videogames

7. Braid

The villain was You

Twists are difficult to pull off these days because the breadcrumb trails that lead to them are full of clichés and easy to spot. Not so in Braid, the at-first unassuming puzzle platformer that hides its truth beneath a whimsical, melancholic veneer. The plot seems threadbare at first (you must save the princess from the evil that holds her captive) but by reading the disjointed story you slowly start to see a very serious narrative unfolding.

The passages of love, from excitement and careless abandon to regret, shame and paranoia, are expressed by an unreliable narrator who’s version of events are as solid as the fluid watercolour backgrounds. The gameplay reflects this too, with the various time-shifting mechanics weaving themselves into the story in an artfully subtle way without ever compromising either.

Then you reach the end and save the princess from the knight who is pursuing her...or at least, that’s what it looks like. You reach out to her, try to touch her, but then everything plays out in ‘reverse’ and now she’s running away from you! She’s activating traps, blocking your path and otherwise doing her best to stop you, until she runs into the arms of her true saviour, the knight. The whole game has been the protagonist replaying his choices in his mind, looking back over the events that lead to him becoming the villain, the bad guy.

But what makes it so perfect is that there’s nothing hidden from the player, everything you need to know the truth is right there in front of you, you just have to put the pieces of the puzzle, sometimes literally, together. There’s no obscuring the events or misleading you unfairly, you’re simply playing with the mindset that as you are controlling the avatar you must be the good guy. It’s a moment that plays with your expectations and gaming conventions and makes you question your actions.

0 notes

Text

The Greatest Narrative Moments in Videogames

8. Undertale

Saving Asriel

It may be less than a year old but Undertale has indelibly wound its way into many gamers’ hearts, mine included. What this game does to make you care for its characters is a masterclass in narrative, character-building and pacing and in a game with so many amazing moments that make you laugh, cry and jump for joy it says something that this is by far the one that really gets you.

Asriel has, by most accounts, been dealt a pretty shitty hand in life. His reward for showing compassion and love is a painful death, followed by a soulless existence in which he is unable to feel love but also unable to die, instead returning to the point in time at which he was reborn as Flowey. After countless lives as a flower the only virtue he can see is in the mantra ‘kill or be killed’: by the beginning of the game he has killed everyone in the Underground untold times, including his own parents, so to say he has become jaded is a gross understatement.

To all extents and purposes he is irredeemable, the indisputable evil of Undertale, but then you uncover the truth and you realise that inside this devil flower is the lonely soul of a child who only wants to love and be loved. You reach the end of the game where he has absorbed every soul in the Underground and begins toying with you, mocking you for loving your friends and for your determination, but by this point you know who dwells inside and when the time comes you know what you must do: you have to save Asriel.

It’s a hugely emotional moment, reducing the self-styled God of Hyperdeath to tears as he realises that he isn’t a heartless monster at all, just a scared little boy, but it also reduces you to tears as well. Find me the person who didn’t shed a tear when they comforted the lonely child and I’ll show you their heart of stone. It’s a moment that will stay with you forever.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Greatest Narrative Moments in Videogames

9. Resident Evil

The first encounter

There’s a lot of things that aren’t right about this mansion: there’s vicious, hideous dogs outside trying to kill you and not a soul inside. That is until you find a human figure bent over another, making...distinctive sounds. The figure turns, and the sight is dreadful: there’s blood around his mouth, he’s snarling and he seems to be missing part of his face. Then he starts shambling towards you, taking more than one shot from your gun to collapse. And what’s worse, he gets back up and chases you outside the room! This scene is memorable for a number of reasons: for many people is was their first experience with true videogaming horror, and the shock of having the monster approaching you coupled with the games finicky tank controls injected the moment with a soupcon of panic. It sets up many things for you, including the theme and atmosphere of the game as well as the basic premise of ‘just because it’s prone, doesn’t mean it won’t get back up.’ The next time you see a zombie on the floor you will probably think twice before going near it. The series may have gone further with the idea of forcing you to deal with threats in a limited space and with restricted controls, but it was this first encounter that made you fumble with the gamepad and shriek in terror.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The Greatest Narrative Moments in Videogames

Videogames are able to make you feel like an unstoppable killing machine as you murder endless streams of alien scum, or a genius for solving a complex puzzle, but they also have a lesser-praised skill of making you sit up in shock, awe or tears. Narrative moments in videogames are tailored to make you feel or react a certain way but when they work they dig themselves into your psyche, and then you always remember the first time.

So while Super Mario 64 had many outstanding moments of awe and wonder for first-time players it lacked moments that compare with some of cinemas greatest story-telling achievements. This, therefore, is the first in a short series that details my top ten moments that will obviously contain many, many spoilers so if you spot a game title you don’t want spoiled for you, know that you have been warned.

10. Half-Life 2: Episode 2

The G-Man returns

He haunted your steps from the very first moments of your tram ride in Black Mesa, observing your movements and shifting events ever so slightly in your favour. Seemingly omniscient and omnipresent, he is a threatening yet enigmatic figure who’s power is incomprehensible, so it is a surprise when he is stopped in the opening cutscene of Half-Life 2: Episode 1 and we see anger on his face for the first time.

The G-Man is Half-Life’s most mysterious element (other than the fate of Half-Life 3) and only ever produces more questions than answers, but it is clear that whatever his motives and however he chooses to go about them there is nothing you can do about it. He literally stops time to pluck you from the jaws of death and, despite objection from ‘naysayers’, saves Alyx Vance from the destruction of Black Mesa on a whim. So while no one thought we’d truly seen the last of him when the vortigaunts got in his way at the beginning of Episode 1 it was still a surprise to see him pop up at an emotional peak of Episode 2.

Alyx Vance has been mortally wounded and you have ventured into the heart of an antlion nest to retrieve the MacGuffin that will save her, but while performing their ritual the vortigaunts are distracted enough to allow the G-Man to sneak in and lay out the next phase of his plan to you. As with all of his encounters he is sinister, ambiguous and threatening, showing little care for the possibility of failure.

It works because he’s a seemingly omnipotent figure who has been castrated, leading you to wonder what stops he will be pulling out to get back on top. The game also felt slightly odd without him appearing in the distance every so often, a silent reminder that someone else is pulling the strings. Knowing that he has ‘returned to power’ opens up the possibilities of what will happen next.

David

0 notes

Text

Freedom of Choice vs The Illusion

Here’s something I wrote initially as an article pitch that never gained any traction, so instead of letting it go to waste I thought I’d re-purpose it for my own use. Enjoy.

Hey, thanks for deciding to read this article. I really appreciate you taking the time because I know it must have been hard deciding what to read on the whole internet but you chose me. Or did you? What if I had expertly engineered your path so that whatever you chose to do you would always end up here? Is it actually possible to make you think you are doing something of your own free will when you aren’t? In videogames, surprisingly so.

Let’s start at the beginning: the original Super Mario Bros. on the NES forced you to go right, you had no choice. But you were allowed to tackle most of the obstacles in whichever way you deemed fit. When you encountered the first goomba you could jump on his head or avoid him entirely, so even though your goal was set in stone your methods of achieving that goal were up to you. And that is pretty much the standard gaming choice: you have to finish the game and you have to progress on the path chosen for you but you have the freedom within that path to play your own way. Some games give you more freedom within that path, like Half-Life 2: Episode 2’s large outdoor areas, while others offer multiple paths within each section of the larger whole, like Dishonored’s sandbox-style levels.

And in that sense it’s pretty obvious that your freedom is essentially nonexistent. You have the tools but you can only open certain doors with them and the game points them out. This is mainly due to the difficulty of accounting for the infinite number of ways that people can react to a given situation. It would be impossible to code a unique response for every way a player might, say, respond to an NPC asking for help, or get from one side of a city to another. So instead developers have to give players either a range of definitive choices or they mask the player’s freedom with subtle guides and funnelling mechanics.

Many RPG’s allow you to choose the outcome of some, if not all conversations by giving you options on what you can say. Sometimes you are able to go through these options one by one to learn more about the NPC and the subject matter but sometimes you’ll have to give a definitive response that you cannot take back, and when those options have a bearing on the rest of the game it can be difficult to make your choice feel like it has a true impact. For instance, at the end of Fable 1 you are given the option of destroying the Sword of Aegis, the most powerful weapon in the game, or use it to kill your sister. Either way the main storyline ends and your sister never reappears, so you either end up playing with the sword but no more meaningful progression or you get a mention in a cut-scene that you spared your sister. It has no impact because either outcome is negligible. Now let’s look at Mass Effect 1: near the end of the game one of your companions, Wrex, gives you an ultimatum and you must decide whether to risk the fate of the universe or kill him. Not only are you fully emotionally-invested in him since you’ve gone through so much already but making either choice will have a massive impact on how the next two games pan out. You only have two options but you feel freer in making the decision because the ramifications are so great and you have the confidence, judging from what you’ve already seen, that the series can deliver on them.

But narrative-driven choices aren’t always so rewarding. Heavy Rain is a good example of giving the player an illusion of choice when, really, their choices are very limited. It is a very plot-heavy game with player input for almost every action and, as the game and promotional material told us quite clearly, it is entirely possible that not every character will make it to the end of the game. During the tense action sequences it does feel like at any moment one of the characters will fail and die, but actually the moments when it counts, when a mistake will actually cost them their lives, are few and far between. Failing an input usually only stops you from getting an achievement or seeing certain, specific scenes playing out later on. In this way though the game suggests that the fate of the characters is in your hands in actual fact you can only influence it greatly at specific points. It is essentially the same as the Mass Effect example but with the illusion that you have more choice.

So those are examples of freedom of choice within very limited boundaries, but how far can we go? An open-world sandbox game like Grand Theft Auto gives you lots of tools to play around with and essentially lets you do whatever you want, but go in another direction where Fallout 4 gives you the tools to not only explore a large open region at your leisure but to also build your own settlements with basic but versatile building blocks. In such instances the game relies just as much on your imagination to go and do what you want and to make your own stories, helping you out by handing you a toolbox of inspiration, than it does on the content that has already been tailored for you.

And if we run with this theme to its logical conclusion we come to a game like LittleBigPlanet, that is essentially a game-maker’s toolkit with a fanciful (but fully-accomplished) storyline glued on top (or screwed, or bolted, or attached, or any of the other LittleBigPlanet tools). In LittleBigPlanet your mind is truly your only obstacle in doing and making what you want, and the choices you make are entirely your own. But then when you make your own levels for other people to play the problem of choice is flipped: now you are the one making decisions for the player and you are the one who has to decide how much choice you give them. Perhaps you want to give them secret areas to uncover or multiple paths to complete? Maybe you want to make an open-world design with side-quests and portals to other levels? Or maybe you just want to recreate that first level from Super Mario Bros.? Whatever you make you will have to impose your will on it and decide who gets to decide.

David

0 notes

Link

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A musing

I had a thought but I didn’t know where to put it where I might get some feedback. My thought was a tiny change to the ending of Star Wars: Episode III - Revenge of the Sith that would drastically alter the finale and give it a huge amount more pathos. Sounds grandiose doesn’t it? Well, when I though of it that’s the feeling I got.

...

Anyway, where was I? Oh yes.

The small change: when Obi-Wan is yelling at Anakin after cutting his legs and arm off (spoilers) he is clearly angry beyond belief but also broken hearted. What if then, instead of Anakin saying ‘I hate you’ (my God George...) he simply reaches out with his hand and with that same broken look on his face. Obi-Wan stops. Is Anakin, his dearest friend and trusted apprentice, reaching out for comfort in his dying moments? Obi-Wan puts his own hand out, ready to forgive him despite all that he did...but then he notices Anakin’s lightsaber wobbling. He wants the lightsaber. Even in his final moments the only thing on his mind is revenge. Obi-Wan feels sicker than he’s ever been. Everything he knew and loved is gone...and now Anakin has fallen farther than he’d ever dared dream a Jedi could go.

tl;dr - Anakin tries to pull his saber towards him instead of saying ‘I hate you’ (for God’s sake George, what were you thinking?)

David

1 note

·

View note

Text

Game of the Year: Undertale

In a year that saw the release of Fallout 4, The Witcher III, Star Wars: Battlefront, Metal Gear Solid V, Halo 5, Bloodborne, Batman: Arkham Knight, Mortal Kombat X, Cities: Skylines, Heroes of the Storm and Rocket League, all huge games in their own right, the competition for Game of the Year has possibly never been tougher, and as far as the 2015 Game Awards are concerned, The Witcher III gets that accolade. But now I’d like to put to you the case for Undertale, a small indie game that nobody could have predicted would turn so many conventions on their heads so succinctly, which I feel is more deserving than even the nigh-on-perfect Witcher entry.

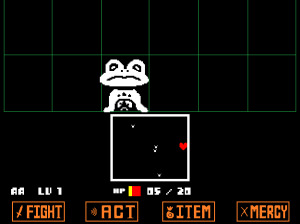

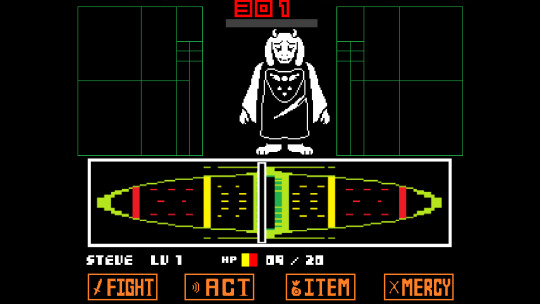

Originality can be hard to come by these days so many artistic types are turning to subversion and reflection for their outlets, taking apart the mediums they work in and exposing the mechanics and secrets to help everyone understand how they work. Undertale is substantially a classic RPG that looks and plays very similarly to, among others, Earthbound: it enjoys a hand-drawn art style that is susceptibly simple and childlike; it features random encounters with battles taking place from the character’s perspective (as opposed to side-on); it employs light-hearted humour over a very dark story; and it involves time travelling, or something akin to it, but we’ll get to that later. At first glance it’s a harmlessly nostalgic love letter to ‘ye olde games of yore’ and it plays out as such until your first battle.

When you attack you are given a sliding bar, and activating it as close to the centre as possible deals more damage. But when an enemy attacks you are represented as a heart in a box which you can move around freely with the arrow keys while projectiles come at you. Every enemy has unique attacks which can take the form of simple pellets to flaming eyes, leaping frogs, lasers, bones, etc., relevant to the enemy (which is important) and giving every encounter a unique flavour. Certain enemies, usually bosses, even change the way you defend yourself: one instance fixes your heart in the centre and you use the four arrows to block incoming spears, like a rhythm game, and another introduces gravity and forces you to engage in platforming jumps. If nothing else it is a clever reinvention of the traditional RPG formula where fights were determined ultimately by stats and numbers instead of wholly by player skill as seen here.

But the most unique aspect to this system is that you are not required to kill anything. Almost every enemy can be run from, but all of them can be spared. The game drops hints early on that you can ‘act’ your way out of a fight until the enemy accepts your offer of mercy. Aaron the bodybuilding seahorse, for instance, can be engaged in a flexing match until he flexes so hard he ‘flexes himself out of the room’. Or Froggit the timid frog, who must be complimented so it’ll decide not to attack you or threatened so it’ll be scared of you. At first it seems like an amusing twist on the traditional formula but then you realise that this subversiveness is engrained into Undertale and, as it turns out, is actually very important. As another example shop keepers will refuse to buy items from you, commenting that if they did it would be bad business practice. The sparing mechanic works its way into the main story too, with main characters commenting on how merciful or bloodthirsty you are at various points, sometimes mentioning specific events, until the ending.

This is where the game truly shines because it tailors the conclusion based on your actions not only in your current run but also in all the attempts you’ve made. Decisions you made in a previous save file that has since been overwritten will be remembered. The antagonist, Flowey (the flower), possesses the ability to Save and Load during your final fight against him and he renders the game unplayable until you’ve dispatched him. It sounds complicated and though the underlying mechanics surely must be, on the surface it is perfectly understandable and you ‘get’ what the game is saying to you.

The most important ending and ‘version’ of the game is the genocide run, a challenge mode of sorts that is both long and arduous that involves killing every enemy type at least once and every main character. It is purposefully tedious because the game wants to teach you a lesson: during the final fight of this ‘genocide run’ mode the secretly clever character Sans will predict why you, the player, have spent so much time killing every entity in the game: for the completionist satisfaction. There can be no other reason for your digital bloodlust because there is no physical or emotional reward for dispatching everyone one by one and investing your time into an ultimately fruitless cause. He questions why you would do such a thing and wonders if it belies a dark truth about yourself and if someone who is capable of wilfully wasting their time on pointless violence is truly wholly sane. It’s a sobering thought and not one you might have expected when you saw the opening pixelated cinematic for the first time talking about humans, monsters and souls.

It’s a game that sits in a category with company like Braid, Fez and The Talos Principle that begin traditionally enough but by the end have turned the mechanics and your own preconceptions inside out. They tell a story with an innocent smile that hides the dark machinations within, a reflection of the true nature of the games they imitate and the people who play them to escape the world they live in. They’re clever for breaking the fourth wall in a natural and subtle way and for laying the foundations for you to connect the dots yourself. And they’re also scary in a way that Resident Evil or Silent Hill can never be, because they force you to think about yourself. We’re unsettled by this because we play games to escape, but we also like to be challenged and what greater challenge is there than to wonder who we are, what we are, and why we are.

But the final and most important aspect that all these games share with Undertale is that they are fun, satisfying and well-crafted. They are great games in their own right, not just cheap imitations or snarky spoofs, and you can see that despite all the cynicism and morbidity there is a genuine love running through them all. To that end Undertale is not just a clever or interesting game, it is a fun one too.

And that is why Undertale is the Game of the Year 2015.

David

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tower 57

I stumbled across this fantastic looking game while browsing for pixel art and thought it looked magnificent enough to share. It’s a twin-sticks shooter with mass-destructability and with a heavy emphasis on multiplayer, though it looks like it’ll be great in single-player too. The game is fully funded on Kickstarter but you can still receive most of the tiered rewards by paying the appropriate amount through their PayPal link, found here: Tower 57.

I emailed the team about the game and the charming Marco Pappalardo responded:

What drew you to develop a game in this art style?

I started gaming on an old 8086, I witnessed the evolution of pixel art from black and green blocks all the way to the 16bit golden age, and I've always been enamoured with this art style, so the choice for me felt natural.

It looks like classic Bitmap Brothers games like The Chaos Engine, is that a coincidence or did you take inspiration?

Absolutely 100% not a coincidence :) The Chaos Engine has always been one of my favourite games, and - as many gamers do - I always thought of ways I could make it better while playing it. The genre also lends itself pretty well to “modernisation” (for example twin stick controls) without betraying what makes the genre cool, and we felt that, contrary to platformers for example, there was still room in the market for a high-quality pixel-art twin stick shooter!

How difficult is it to create a new ip without a large publisher behind you? Would you have preferred it another way or do you enjoy the creative freedom?

I would say quite difficult. Nowadays more than ever, it seems marketing is very important to get your game to stand above the “noise”, and I have no problems recognising my own shortcomings in this field ^_^ I'm very happy about the way things went, and certainly value the creative freedom we have at our disposal, but neither Thomas nor myself would be opposed to the idea of a publisher if we could find a way to retain our creative freedom. Ultimately the goal is to get the game on as many screens as possible, and publishers do this for a living :)

Are you worried about delivering what your backers have paid for having seen the difficulties faced by developers in the same position?

I'm very confident in our ability to deliver, I've been professionally coding games for a little over 10 years now, and Thomas is a very skilled artist with a very strong work ethic. We purposefully stayed away from “crazy promises” during the campaign, and have spent the best part of the last year prototyping all our ideas and refining the tools to support content creation. The only “risk factor” at this point is the timeline, but technically speaking we have made sure we can deliver on our promises.

What are the long and short-term futures for the game and the studio?

The short term plan is to focus 100% on Tower 57 until release (this was the goal of the Kickstarter after all). Depending on the success of the game, we would then like to extend our partnership into a proper dev studio and self-fund our next game :)

Are the backer rewards still valid for payments via paypal? If so, for how long?

Absolutely! Except for the “design rewards” which are “sold out” on the Kickstarter page, backers can still pick rewards when backing through Paypal. We will most likely close it down at some point, but for the time being anybody who wants to jump on board is more than welcome to do it!

I would definitely say, having seen the prototype and development material, that this is more than just a pixel-art game and I've put my money where my mouth is to prove it. That’s not a challenge, by the way, just a confirmation that I have been impressed by what I’ve seen. The link is at the top if you want to donate yourself or you can simply go there to admire these fantastically nostalgic graphics in fluid motion. Either way, go Twoer 57!

David

0 notes

Text

Looks like Genius - The Binding of Isaac, the Seven Deadly Sins

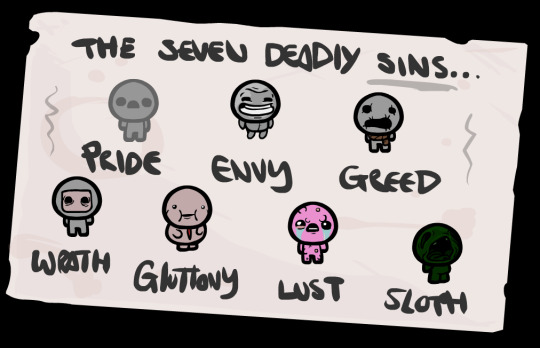

I love The Binding of Isaac: it’s full of the basest humour imaginable yet it has such great depth to it. And while you may argue that it isn’t hard to animate a pile of poo, to do it in such a way that you nod and go ‘yep, that’s how a piece of poo would move if it could’ takes skill. But the best example of design in The Binding of Isaac is in the Seven Deadly Sins.

Come on everybody: ‘Pride, Envy, Greed, Wrath, Gluttony, Lust, Sloth, and a partridge in a pear tree.’ The seven deadly sins represent the aspects of ourselves that, if given into, will drag us into irredeemable damnation.

Apparently. But they are just themes, vices that don’t have a face so to give them one takes consideration, and even more to make them walk around and hurt a videogame avatar. See, it’s all very well making Gluttony a fat man but how should he sound? What attacks should he perform that fit with the themes and styles of the game that says ‘gluttony’? The Binding of Isaac has put these age-old questions to rest, finally!

Let’s start with gluttony then, as he’s probably the simplest. Yes, he’s a fat person. Yes, his mouth is stuffed and he walks around like he’s eaten too much over many, many years. His first attack is pretty straightforward too: he fires tears (this games basic projectile) in eight directions at once. But then his secondary attack is to open a wound in his stomach and fire a line of blood in one of the four cardinal directions, the idea being a representation of how gluttony spills out because, ultimately, you cannot contain it. Still though, a standard depiction for the most part.

Then we have lust, a pink dude who is clearly STD-ridden. He chases you round the room, trying to touch you, and he’s quick! He wants you! He can’t get enough of you, even though it’s clearly not good for him.

Greed is next and he looks rather hollow: his eyes are just black sockets and his complexion and twisted mouth make him look like a corpse. He also has a noose round his neck and he spawns little greed heads, and whenever either he or the heads deal damage to you it spawns coins that you can pick up. This leads to the temptation of taking damage to get some money, or sacrificing your own well being to feed your hunger for money, which is the idea of greed in the first place.

Envy floats around rather harmlessly but splits into smaller pieces when you kill him, which split up further, and so on. Eventually the room is full of envy, just like how envy consumes you if you let it. You can, of course, focus on each piece in turn and prevent yourself getting swamped but it takes time and dedication. Dealing with the problem carelessly will see you getting out of your depth.

Wrath drops bombs and is otherwise self-explanatory except his bombs can also hurt him, just like how in real life allowing yourself to be controlled by anger will hurt you as much as your target.

Then there’s pride, who attacks by gleefully jumping up and shouting, or by filling the room with bombs. This is akin to loudly talking about yourself to whoever is in ear shot regardless of whether they want to hear or not.

And then we reach sloth, my favourite deadly sin character because of his clever design: he’s green and walks around shooting explosive projectiles and spawning little grubs that chase you down. At first glance the connotations aren’t obvious, but let’s look a little closer: nothing about this boss is original. All the other sins have unique models and attacks (or at least attacks that are copied by later creatures) but sloth uses the exact same model as another enemy and both his attacks are borrowed. In making him the designers have literally employed the use of sloth.

Each sin also has a ‘super’ version that ups the ante in some way, but then there’s also the unique Ultra Pride which depicts Edmund McMillan (the creator) as a larger version of sloth which, again, uses borrowed attacks. It’s like a mini autobiography, a self-critique and it’s clever to boot. The rest of the game is full of the same brilliantly-realised design, epitomised by the seven deadly sins.

89 notes

·

View notes