Desk of Jack Elving (aka Revolutionary_Jack). Drink Full and Descend.

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

2024 - IT AIN'T EVEN GOT TO BE DEEP, I GUESS

#2024 the year is over. Here’s my end of year feelings about it and stuff I saw and liked this year.

Ultimate Spider-Man #12. Art by Marco Cecchetto So what was your 2024 like? Continue reading 2024 – IT AIN’T EVEN GOT TO BE DEEP, I GUESS

#&039;Bart&039;s Birthday&039;#Alan Moore#Alex Garland#Alice Rohrwacher#Avi Mograbi#Benjamin Labatut#Call of Juarez Gunslinger#Christopher Nolan#Civil War (2024)#Daniel Clowes#David Messina#Death Stranding#Do Not Expect Too Much From The End of the World#Drake#Dune Part Two (2024)#F. D. Signifier#Furiosa#Harry Osborn#Hideo Kojima#Jedi Survivor#Joe Sacco#John von Neumann#Jonathan Hickman#Kendrick Lamar#Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes#Kirsten Dunst#Kubi (Kitano)#Marco Cecchetto#Mary Jane Watson#Mayday Parker

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

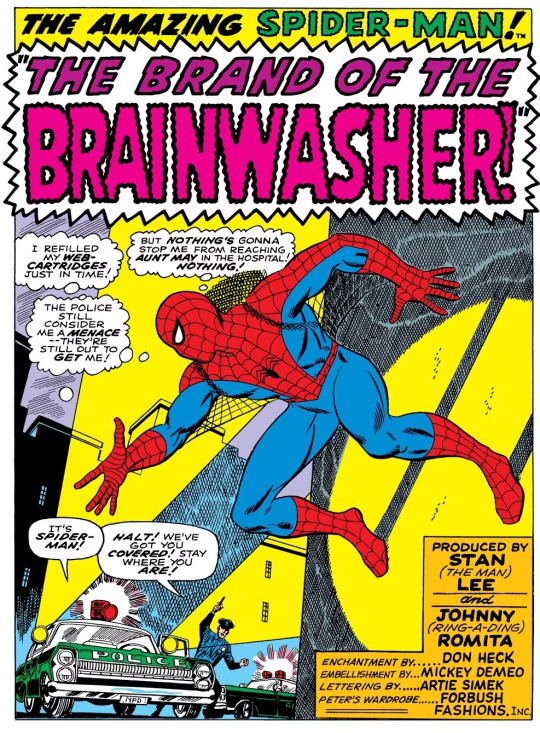

Re-Examining Spider-Man 11: Class Relations

"Will Success Spoil #SpiderMan?" Re-Ex-SM is Back on Thanksgiving 2024! Looking at the #JohnRomitaSr era and how it connects to the superhero class struggle for love and better housing. Is Peter Parker a gold digger? The answer might surprise you!

THIS POST IS DEDICATED TO STEVEN ATTEWELL, IN HOMAGE TO HIS SERIES: A PEOPLE’S HISTORY OF THE MARVEL UNIVERSE For as much as Spider-Man is described being a working-class superhero, class is rarely analyzed in these stories. On account of the demands of the genre, the mainstream superhero action-adventure, Peter Parker rarely expresses ‘class consciousness’ in any direct sense. The nature of the…

#Abraham Josephine Riesman#Arthur Miller#Aunt May#Betty Brant#Black Cat#Brian Michael Bendis#Brooklyn Bridge#Cat on a Hot Tin Roof#Comic-Creators on Spider-Man#Daily Bugle#Death of a Salesman#Don Heck#Felicia Hardy#Flash Thompson#Frank Capra#Frank Castle#George Stacy#George Washington Bridge#Gerry Conway#Gil Kane#Green Goblin#Gwen Stacy#Harry Osborn#Hobie Brown#J. Jonah Jameson#J. M. Dematteis#Jack Kirby#beyonce#daddy lessons#its a wonderful life

10 notes

·

View notes

Note

(Last part!) This is why I was saying that most, albeit not all, of us live very similarly to our North American colleagues... And almost no one has got the clout to circumvent the issue by trademarking their own names like Don Rosa! 'xD Work for hire is still work for hire and (since, iirc, you've mentioned directors' rights to final reshoots and cuts) the editors and publishers can still change and/or censor anything they want without even notifying the original creators.

I guess.

0 notes

Note

Correction about European comic writers and artists having author rights: that's only true for the few ones who create their own wholly original series. The vast majority of comic authors work for hire using corporate-owned characters just like their North American colleagues, so they're only paid X euros per page without royalties, with the X value increasing along with their seniority.

Interesting. I've heard other stuff but I'll accept the caveat.

0 notes

Text

No notes

you need to remember to blog with your pussy first and brain second

9K notes

·

View notes

Note

Would like to discuss the MCU Version of J. Jonah Jameson with you and how he can be redeemed. I have some ideas. Any way to get in contact?

Sure just drop me a line in chat

0 notes

Text

NOTES on Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes (2024)

I saw Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes (should really be “Kingdom of the Apes” but whatever) and I surprisingly liked it a lot. I also found a lot of reviews of the film missing the mark of the film. So I’m going to explore it a bit here. SPOILERS. So about Planet of the Apes… Short answer, I’ve never been a fan of the franchise and the reason has everything to do with prejudice. I just don’t…

View On WordPress

#Ahmad Best#Andy Serkis#Apeman (song)#Caesar (Andy Serkis)#Charlton Heston#Conan the Barbarian (Milius)#Congo (film)#Dawn of the Planet of the Apes#Dr. Zaius#Dr. Zaius (song)#Falco#Franz Kafka#George of the Jungle#Jar Jar Binks#Kevin Durand#King Kong 1933#Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes#Matt Draper#Michel Serres#Mighty Joe Young#Noa (Owen Teague)#Nova/Mae#Philip José Farmer#Planet of the Apes#Promethea#Proximus Caesar#Rise of the Planet of the Apes#Sasquatch Sunset#Tarzan#The Kinks

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

THANK YOU FOR THE DAYS: Steven Attewell, In Memoriam.

My tribute to @racefortheironthrone, aka Steven Attewell. Thank you for the days.

View On WordPress

#A Dance With Dragons#A Distant Mirror (history book)#A Song of Ice and Fire#Adam Attewell#Aelfred of Wessex#Assassin&039;s Creed Valhalla#Barbara Tuchman#Boiled Leather (podcast)#Captain America#Days (Kinks&039; Song)#Douglas Wolk#Dunk and Egg#Edward Said#Elana Levin#Franco Berardi#Game of Thrones#George RR Martin#Jack Kirby#John Ball#JulianLapostat#Lawyers Guns & money#Magneto#Marc Simonetti#Noam Chomsky#People Must Live by Work#Race for the Iron Throne#Scott Eric Kaufman#Sean T. Collins#Ser Davos Seaworth#Spider-Man

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Steven Attewell, aka #racefortheironthrone has passed away. https://t.co/i6RF2V4rtz

He was an immense influence on me as a writer and online commenter. I would not have started my blog and my tumblr had it not been for him. I will write on him in the coming weeks but for now, Rest in Peace. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sfyzaiT_rRU

Is shrinkflation a new phenomenon, or and old phenomenon given a new name?

More the latter.

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

OK, I'll bite - what's the deal with the United Farm Workers? What were their strengths and weaknesses compared to other labor unions?

It is not an easy thing to talk about the UFW, in part because it wasn't just a union. At the height of its influence in the 1960s and 1970s, it was also a civil rights movement that was directly inspired by the SCLC campaigns of Martin Luther King and owed its success as much to mass marches, hunger strikes, media attention, and the mass mobilization of the public in support of boycotts that stretched across the United States and as far as Europe as it did to traditional strikes and picket lines.

It was also a social movement that blended powerful strains of Catholic faith traditions with Chicano/Latino nationalism inspired by the black power movement, that reshaped the identity of millions away from asimilation into white society and towards a fierce identification with indigeneity, and challenged the racist social hierarchy of rural California.

It was also a political movement that transformed Latino voting behavior, established political coalitions with the Kennedys, Jerry Brown, and the state legislature, that pushed through legislation and ran statewide initiative campaigns, and that would eventually launch the careers of generations of Latino politicians who would rise to the very top of California politics.

However, it was also a movement that ultimately failed in its mission to remake the brutal lives of California farmworkers, which currently has only 7,000 members when it once had more than 80,000, and which today often merely trades on the memory of its celebrated founders Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez rather than doing any organizing work.

To explain the strengths and weaknesses of the UFW, we have to start with some organizational history, because the UFW was the result of the merger of several organizations each with their own strengths and weaknesses.

The Origins of the UFW:

To explain the strengths and weaknesses of the UFW, we have to start with some organizational history, because the UFW was the result of the merger of several organizations each with their own strengths and weaknesses.

In the 1950s, both Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez were community organizers working for a group called the Community Service Organization (an affiliate of Saul Alinsky's Industrial Areas Foundation) that sought to aid farmworkers living in poverty. Huerta and Chavez were trained in a novel strategy of grassroots, door-to-door organizing aimed not at getting workers to sign union cards, but to agree to host a house meeting where co-workers could gather privately to discuss their problems at work free from the surveillance of their bosses. This would prove to be very useful in organizing the fields, because unlike the traditional union model where organizers relied on the NRLB's rulings to directly access the factory floors, Central California farms were remote places where white farm owners and their white overseers would fire shotguns at brown "trespassers" (union-friendly workers, organizers, picketers).

In 1962, Chavez and Huerta quit CSO to found the National Farm Workers Association, which was really more of a worker center offering support services (chiefly, health care) to independent groups of largely Mexican farmworkers. In 1965, they received a request to provide support to workers dealing with a strike against grape growers in Delano, California.

In Delano, Chavez and Huerta met Larry Itliong of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), which was a more traditional labor union of migrant Filipino farmworkers who had begun the strike over sub-minimum wages. Itliong wanted Chavez and Huerta to organize Mexican farmworkers who had been brought in as potential strikebreakers and get them to honor the picket line.

The result of their collaboration was the formation of the United Farm Workers as a union of the AFL-CIO. The UFW would very much be marked by a combination of (and sometimes conflict between) AWOC's traditional union tactics - strikes, pickets, card drives, employer-based campaigns, and collective bargaining for union contracts - and NFWA's social movement strategy of marches, boycotts, hunger strikes, media campaigns, mobilization of liberal politicians, and legislative campaigns.

1965 to 1970: the Rise of the UFW:

While the strike starts with 2,000 Filipino workers and 1,200 Mexican families targeting Delano area growers, it quickly expanded to target more growers and bring more workers to the picket lines, eventually culminating in 10,000 workers striking against the whole of the table grape growers of California across the length and breadth of California.

Throughout 1966, the UFW faced extensive violence from the growers, from shotguns used as "warning shots" to hand-to-hand violence, to driving cars into pickets, to turning pesticide-spraying machines onto picketers. Local police responded to the violence by effectively siding with the growers, and would arrest UFW picketers for the crime of calling the police.

Chavez strongly emphasized a non-violent response to the growers' tactics - to the point of engaging in a Gandhian hunger strike against his own strikers in 1968 to quell discussions about retaliatory violence - but also began to employ a series of civil rights tactics that sought to break what had effectively become a stalemate on the picket line by side-stepping the picket lines altogether and attacking the growers on new fronts.

First, he sought the assistance of outside groups and individuals who would be sympathetic to the plight of the farmworker and could help bring media attention to the strike - UAW President Walter Reuther and Senator Robert Kennedy both visited Delano to express their solidarity, with Kennedy in particular holding hearings that shined a light on the issue of violence and police violations of the civil rights of UFW picketers.

Second, Chavez hit on the tactic of using boycotts as a way of exerting economic pressure on particular growers and leveraging the solidarity of other unions and consumers - the boycotts began when Chavez enlisted Dolores Huerta to follow a shipment of grapes from Schenley Industries (the first grower to be boycotted) to the Port of Oakland. There, Huerta reached out to the International Longshoremen's and Warehousemen's Union and persuaded them to honor the boycott and refuse to handle non-union grapes. Schenley's grapes started to rot on the docks, cutting them off from the market, and between the effects of union solidarity and growing consumer participation in the UFW's boycotts, the growers started to come under real economic pressure as their revenue dropped despite a record harvest.

Throughout the rest of the Delano grape strike, Dolores Huerta would be the main organizer of the national and internal boycotts, travelling across the country (and eventually all the way to the UK) to mobilize unions and faith groups to form boycott committees and boycott houses in major cities that in turn could educate and mobilize ordinary consumers through a campaign of leafleting and picketing at grocery stores.

Third, the UFW organized the first of its marches, a 300-mile trek from Delano to the state capital of Sacramento aimed at drawing national attention to the grape strike and attempting to enlist the state government to pass labor legislation that would give farmworkers the right to organize. Carefully organized by Cesar Chavez to draw on Mexican faith traditions, the march would be labelled a "pilgrimage," and would be timed to begin during Lent and culminate during Easter. In addition to American flags and the UFW banner, the march would be led by "pilgrims" carrying a banner of Our Lady of Guadelupe.

While this strategy was ultimately effective in its goal of influencing the broader Latino community in California to see the UFW as not just a union but a vehicle for the broader aspirations of the whole Latino community for equality and social justice, what became known in Chicano circles as La Causa, the emphasis on Mexican symbolism and Chicano identity contributed to a growing tension with the Filipino half of the UFW, who felt that they were being sidelined in a strike they had started.

Nevertheless, by the time that the UFW's pilgrimage arrived at Sacramento, news broke that they had won their first breakthrough in the strike as Schenley Industries (which had been suffering through a four-month national boycott of its products) agreed to sign the first UFW union contract, delivering a much-needed victory.

As the strike dragged on, growers were not passively standing by - in addition to doubling down on the violence by hiring strikebreakers to assault pro-UFW farmworkers, growers turned to the Teamsters Union as a way of pre-empting the UFW, either by pre-emptively signing contracts with the Teamsters or effectively backing the Teamsters in union elections.

Part of the darker legacy of the Teamsters is that, going all the back to the 1930s, they have a nasty habit of raiding other unions, and especially during their mobbed-up days would work with the bosses to sign sweetheart deals that allowed the Teamsters to siphon dues money from workers (who had not consented to be represented by the Teamsters, remember) while providing nothing in the way of wage increases or improved working conditions, usually in exchange for bribes and/or protection money from the employers. Moreover, the Teamsters had no compunction about using violence to intimidate rank-and-file workers and rival unions in order to defend their "paper locals" or win a union election. This would become even more of an issue later on, but it started up as early as 1966.

Moreover, the growers attempted to adapt to the UFW's boycott tactics by sharing labels, such that a boycotted company would sell their products under the guise of being from a different, non-boycotted company. This forced the UFW to change its boycott tactics in turn, so that instead of targeting individual growers for boycott, they now asked unions and consumers alike to boycott all table grapes from the state of California.

By 1970, however, the growing strength of the national grape boycott forced no fewer than 26 Delano grape growers to the bargaining table to sign the UFW's contracts. Practically overnight, the UFW grew from a membership of 10,000 strikers (none of whom had contracts, remember) to nearly 70,000 union members covered by collective bargaining agreements.

1970 to 1978: The UFW Confronts Internal and External Crises

Up until now, I've been telling the kind of simple narrative of gradual but inevitable social progress that U.S history textbooks like, the Hollywood story of an oppressed minority that wins a David and Goliath struggle against a violent, racist oligarchy through the kind of non-violent methods that make white allies feel comfortable and uplifted. (It's not an accident that the bulk of the 2014 film Cesar Chavez starring Michael Peña covers the Delano Grape Strike.)

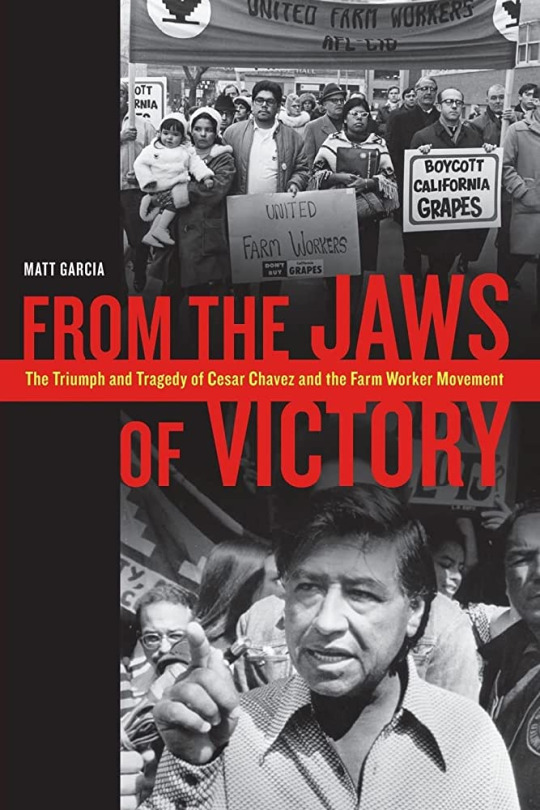

It's also the period in which the UFW's strengths as an organization that came out of the community organizing/civil rights movement were most on display. In the eight years that followed, however, the union would start to experience a series of crises that would demonstrate some of the weaknesses of that same institutional legacy. As Matt Garcia describes in From the Jaws of Victory, in the wake of his historic victory in 1970, Cesar Chavez began to inflict a series of self-inflicted injuries on the UFW that crippled the functioning of the union, divided leadership and rank-and-file alike, and ultimately distracted from the union's external crises at a time when the UFW could not afford to be distracted.

That's not to say that this period was one of unbroken decline - as we'll discuss, the UFW would win many victories in this period - but the union's forward momentum was halted and it would spend much of the 1970s trying to get back to where it was at the very start of the decade.

To begin with, we should discuss the internal contradictions of the UFW: one of the major features of the UFW's new contracts was that they replaced the shape-up with the hiring hall. This gave the union an enormous amount of power in terms of hiring, firing and management of employees, but the quid-pro-quo of this system is that it puts a significant administrative burden on the union. Not only do you have to have to set up policies that fairly decide who gets work and when, but you then have to even-handedly enforce those policies on a day-to-day basis in often fraught circumstances - and all of this is skilled white-collar labor.

This ran into a major bone of contention within the movement. When the locus of the grape strike had shifted from the fields to the urban boycotts, this had made a new constituency within the union - white college-educated hippies who could do statistical research, operate boycott houses, and handle media campaigns. These hippies had done yeoman's work for the union and wanted to keep on doing that work, but they also needed to earn enough money to pay the rent and look after their growing families, and in general shift from being temporary volunteers to being professional union staffers.

This ran head-long into a buzzsaw of racial and cultural tension. Similar to the conflicts over the role of white volunteers in CORE/SNCC during the Civil Rights Movement, there were a lot of UFW leaders and members who had come out of the grassroots efforts in the field who felt that the white college kids were making a play for control over the UFW. This was especially driven by Cesar Chavez' religiously-inflected ideas of Catholic sacrifice and self-denial, embodied politically as the idea that a salary of $5 a week (roughly $30 a week in today's money) was a sign of the purity of one's "missionary work." This worked itself out in a series of internicene purges whereby vital college-educated staff were fired for various crimes of ideological disunity.

This all would have been survivable if Chavez had shown any interest in actually making the union and its hiring halls work. However, almost from the moment of victory in 1970, Chavez showed almost no interest in running the union as a union - instead, he thought that the most important thing was relocating the UFW's headquarters to a commune in La Paz, or creating the Poor People's Union as a way to organize poor whites in the San Joaquin Valley, or leaving the union altogether to become a Catholic priest, or joining up with the Synanon cult to run criticism sessions in La Paz. In the mean-time, a lot of the UFW's victories were withering on the vine as workers in the fields got fed up with hiring halls that couldn't do their basic job of making sure they got sufficient work at the right wages.

Externally, all of this was happening during the second major round of labor conflicts out in the fields. As before, the UFW faced serious conflicts with the Teamsters, first in the so-called "Salad Bowl Strike" that lasted from 1970-1971 and was at the time the largest and most violent agricultural strike in U.S history - only then to be eclipsed in 1973 with the second grape strike. Just as with the Salinas strike, the grape growers in 1973 shifted to a strategy of signing sweetheart deals with the Teamsters - and using Teamster muscle to fight off the UFW's new grape strike and boycott. UFW pickets were shot at and killed in drive-byes by Teamster trucks, who then escalated into firebombing pickets and UFW buildings alike.

After a year of violence, reduced support from the rank-and-file, and declining resources, Chavez and the UFW felt that their backs were up against a wall - and had to adjust their tactics accordingly. With the election of Jerry Brown as governor in 1974, the UFW pivoted to a strategy of pressuring the state government to enact a California Agricultural Labor Relations Act that would give agricultural workers the right to organize, and with that all the labor protections normally enjoyed by industrial workers under the Federal National Labor Relations Act - at the cost of giving up the freedom to boycott and conduct secondary strikes which they had had as outsiders to the system.

This led to the semi-miraculous Modesto March, itself a repeat of the Delano-to-Sacramento march from the 1960s. Starting as just a couple hundred marchers in San Francisco, the March swelled to as many as 15,000-strong by the time that it reached its objective at Modesto. This caused a sudden sea-change in the grape strike, bringing the growers and the Teamsters back to the table, and getting Jerry Brown and the state legislature to back passage of California Agricultural Labor Relations Act.

This proved to be the high-water mark for the UFW, which swelled to a peak of 80,000 members. The problem was that the old problems within the UFW did not go away - victory in 1975 didn't stop Chavez and his Chicano constituency feuding with more distinctively Mexican groups within the movement over undocumented immigration, nor feuding with Filipino constituencies over a meeting with Ferdinand Marcos, and nor escalating these internal conflicts into a series of leadership purges.

Conclusion: Decline and Fall

At the same time, the new alliance with the Agricultural Labor Relations Board proved to be a difficult one for the UFW. While establishment of the agency proved to be a major boon for the UFW, which won most of the free elections under CALRA (all the while continuing to neglect the critical hiring hall issue), the state legislature badly underfunded ALRB, forcing the agency to temporarily shut down. The UFW responded by sponsoring Prop 14 in the 1976 elections to try to empower ALRB, and then got very badly beaten in that election cycle - and then, when Republican George Deukmejian was elected in 1983, the ALRB was largely defunded and unable to achieve its original elective goals.

In the wake of Deukmejian, the UFW went into terminal decline. Most of its best organizers had left or been purged in internal struggles, their contracts failed to succeed over the long run due to the hiring hall problem, and the union basically stopped organizing new members after 1986.

71 notes

·

View notes

Note

Scorsese doesn't own his films and technically they are all made for-hire as well. It's just that cinema is so much more well-paid and union protected, and the fact that the main value of Scorsese's films are that they are Scorsese films, that you likely won't have stuff like rights owners recutting his films (which legally *can* happen but very likely won't; there have been attempts to do remakes/sequels/prequels to Raging Bull or Taxi Driver, which is more likely to happen but Scorsese has managed to stall such things). With Alan Moore, the issue is that WATCHMEN was supposed to be owned by him and Dave Gibbons. That was the agreement of the original contract. It's the equivalent of Orson Welles denied ownership of CITIZEN KANE, which didn't happen. Welles' original contract allowed him to own CITIZEN KANE which was unprecedented and that contract was honored, regardless of the controversy, and it allowed Welles a lifelong income to fall back on while he hustled for low-budget deconstructionist Shakespeare movies. [In Europe both comics and cinema have les droits d'auteur, with directors allowed final cut and ownership by law] And then after failing to return ownership to Moore and Gibbons, DC decided to start siphoning and spinning WATCHMEN, which is the equivalent of making Citizen Kane into a TV show or miniseries without Welles' consent. And I think it was the latter that led Moore to give up comics, because Watchmen isn't even allowed to be the literary exception to endless superhero stories by DC. And he saw it as them trying to delete its prestige, which basically they were. I will add that Moore has generally been more fortunate than others. He has enough prestige and name that he can do Non-IP comics by himself (though not without some period of struggle) whereas Kieron Gillen, heck even Neil Gaiman, still has to do cape comics before going back to creator owned. Like LOEG sold pretty well as did PROVIDENCE and FROM HELL. So with Moore, it was personal disillusionment. His magnificent novel What We Can Know About Thunderman is one of the best things he's done, and up-there with Cavalier and Klay in terms of a novel about comics. It's also an incredible book about the mentality of the comics business and the entire fan-to-writer-to-corporate shill pipeline.

Does the comics industry treat its creators worse than other entertainment industries? I ask because someone mentioned Alan Moore has given up writing comics because of his disillusionment with the comics industry, and that it was the equivalent of Martin Scorsese giving up films.

I discuss this in some detail here:

Historically, the comics industry has been surprisingly hostile to most forms of revenue sharing - residuals, profit shares, and the like - and unusually wedded to so-called "work for hire." This has led to a lot of famous creators getting screwed when it came to their financial rights or creative inputs over their creations.

However, there's nothing intrinsic to the comics industry that made it so - the problems that comics creators have complained about for decades were the same problems that creators in film and television complained with all the time before the advent of unionism in those industries. So yeah, comics would be quite different if it was unionized.

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

It's probably vicarious wish-fulfillment on Lee and Kirby's part. They wanted to be famous so they wrote about people who were famous, and through that lived through their different levels of mid-life crisis. 'Course eventually it did make them famous anyway.

One thing I noticed from the mutant metaphor article is that the Fantastic Four live on Madison Avenue, which is synonymous with "advertising", both now and when the comic started. Is that just a coincidence?

No, I think from the beginning, Stan and Jack were interested in the concept of celebrity and fame - it’s why there’s Fantastic Four-mania in the comics, it’s why Johnny becomes a teen heartthrob, it’s why Sue becomes a model. And later writers have run with that ball.

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

The world’s largest population in India is majority polytheistic though (they also have admittedly the second or third largest Muslim population). And Buddhism which doesn’t fit either parameter is significant in the Indo China region. If not for the CCP’s repression, it’s likely that China would have significant strains of traditional belief.

Is there a reason for why the majority of major religions in the world today are not polytheistic, or is it mostly just luck?

I know that theologians, anthropologists, and historians of religion have theories about how monotheistic religions have a competitive advantage when it comes to organization and prosletyizing, but I don't know enough about the field to have much of an opinion about it.

34 notes

·

View notes

Note

Possession has pretty much fallen into a "bad guy superpower" these days. It's too suggestive of enslavement and violation of consent. Kirby's Anti-Life Equation is all about Darkseid attaining universal possession after all: "if someone possesses absolute control over you — you're not really alive".

Having just watch "Fallen" starring Denzel Washington I was wondering what's a better superpower, shapeshifting or possession?

Neither are my favorite superpowers, but of the two, I'd definitely go with shapeshifting.

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

ASM#91-92 has Spider-Man combat a racist white-supremacist prosecutor named Sam Bullitt. That's closest to what you want. There's also ASM#99 which has a sympathetic portrayal of a Prison Riot (post-Attica, though it's conclusion is pretty unbelievable in its optimism but the message is nice). Aside from that, other stories of Spider-Man veer over the map. Like "The Death of Jean DeWolff" deals with police work and mob-like lynch hysteria (with Spider-Man falling into it until Daredevil holds him back). In terms of media, Andrew Garfield's TASM-1 is the only one that has Spider-Man actively hunted by the police (it's adapting in part the Bullitt 2-parter but doing it badly) with George Stacy calling Spider-Man an "anarchist" but the ending ends in a more pro-cop place than any previous or subsequent Spider-Man movie. In games, The Spider-Man 2000 actually has him hunted by the police who fire live rounds and use searchlights to track him. But that was the last time before 9/11. In general the Spider-Man distrusted by the police is an inconsistent theme that comes and goes.

So as discussed before, Spider-Man historically hasn’t had a great relationship with the police and rightfully so. But a lot of stories I hear about come from the place of police against Spider-Man , but I was wondering if you have any recommendations for stories about Spider-Man against the police if that makes sense? Rather than the focus of police hunting Spider-Man, defending himself against them, etc, Spider-Man being the active one and standing up to police and helping / protecting citizens against them as being part of a friendly neighborhood Spider-Man

That's a good question, because while it's very common for the police to be presented as antagonists to Spider-Man who are targeting him for a crime he didn't commit or who are awful at actually getting convictions on the criminals he literally drops in their laps, they tend to function more as obstacles and hindrances getting in the way of Spider-Man dealing with the real problem.

I did a fair bit of research and read up on a bunch of Spider-Man stories that involve him dealing with the police, and I couldn't turn up any story where Spider-Man actively goes after the cops at the level of the storyline where Steve Rogers infiltrated the NYPD to bring down authoritarian cops trying to gin up a law-and-order backlash against police reforms:

15 notes

·

View notes

Note

If you dislike the people who live in a city, by definition you don't love the city. For me that's a maxim. Robert Moses simply loved a Zoom Filter or a Post-Apocalyptic video-game level with desolate ruins, or the opening of 28 Days Later transplanted to NYC. He absolutely did not love the city.

Thoughts on Robert Moses?

I think I've more or less covered them in my previous posts on the subject. I consider Moses to be a real tragedy for New York, because he was clearly someone of great political and adminstrative ability, but who was just fundamentally wrong about his core ideas relating to transportation and transit, and who used his abilities whenever and wherever possible to fuck over poor communities of color.

The most dangerous thing one can be is competent and evil at the same time.

64 notes

·

View notes