An Israeli soldier, embarking on a mission to teach Hebrew from א to ת! Stick around for this journey of ours

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Tagged Post

i was tagged by @weepinggardenflower to do this post, so first of all thank you!

let’s go-

nickname- i dont really have a nickname lol. my name is Tomer.

gender- male

astrological sign- sagittarius

height- 1.85~ish meters. 6’ 1/2’’

sexuality- gay

hogwarts house- i’ve never watched harry potter i’m so sorry

favorite animal- hands down dogs

number of blankets- one at home, one at base

where i’m from- israel

dream trip- mexico. austria. ummmmmm italy as well?

when did i create this blog? just about two and a half years ago, january 2017. i was getting really bored waiting to enlist into the military so i decided to put my time to good use. i’ve always wanted to get into teaching and this was a great way to practice it.

honestly i’ve been completely out of touch with tumblr these past two years so i’m gonna have to stop this tag train here

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Update

Soo... apparently it’s been harder than i thought keeping this blog up to date during my service. lol. I’ll be on hiatus until at least November 2019, when i’m discharged from the military.

I will be back though!

Until next lesson :)

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hebrew Animals 🦑

Thought it’d be nice to do a light vocabulary lesson while I’m still on hiatus

* ז stands for זכר, meaning male. * נ stands for נקבה, meaning female.

689 notes

·

View notes

Link

Hello everyone!

A friend of mine who is also studying Hebrew and their friend have started a Hebrew teaching blog. Their goal is to teach Hebrew vocabulary and grammar through memes. It is a very good way to learn vocabulary in an entertaining and engaging way, as well as an easy way to learn practical spoken Hebrew slang, which is oftentimes used in memes in favor of the literary language. Plus it gives you an insight into Israeli pop culture, if you are also interested in learning about the culture of the country as well as its language.

I highly encourage you to check out the first couple of posts and follow the blog for future lessons. I might even contribute some of the memes.

Also, a quick update: I’ve been a lot less busy lately and it’s quite likely I start making lessons again starting where I stopped, maybe on a monthly basis. So keep your eyes peeled and your feeds ready.

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Announcement: Temporary Hiatus

Hey everyone.

As you know, I’m an 18 year old Israeli student. I started this project as a way to pass time before my encroaching enlistment to the IDF, mostly as a personal test to see how well I can teach about my mother tongue. It has proven quite fruitful and I do enjoy writing these lessons very much. But there’s a catch.

I’ll be enlisting a week from the day I’m writing this. For the first couple months of my military service I’ll only be at home once a week at best, so sadly I won’t be able to write any new lessons as they do take quite a bit of work (and a computer).

I already have a rough map of where I want this blog to continue, and I do wish to continue doing this, but unfortunately I will have to delay it by a couple months at least.

I finished verb basics to lay out a base for upcoming lessons. You can check that out here: 1, 2, 3.

See you next lesson!

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hebrew Basics #5: Verbs, pt. 3: Heavy Verb Stems

Hi everyone!

This lesson I’ll finally be finishing up Hebrew verb stems with the last group of stems: פֻּעַל, פִּעֵל and הִתְפַּעֵל - also called the heavy stems (בִּנְיַנְים כְּבֵדִים binyanim kfvedim) or the double stems (בִּנְיַנְים כְּפוּלִים binyanim kfulim).

The main feature distinguishing them from other stems is a dagesh on the 2nd radical letter, which also gives them their names (note that because ע is a guttural letter it cannot take a dagesh, so it doesn’t appear in the very name of the verb stems - but it’s there). Historically, this dagesh signified gemination, or doubling of a consonant, much like an Arabic shaddah. For instance: כָּתַב ‘(he) wrote’ would be pronounced katav, whereas כַּתָּב ‘reporter’ would be pronounced kattav. These days letters with a dagesh are not pronounced differently than the same letter without a dagesh, but its effect can still be seen - for example in בג״ד כפ״ת, that did not go under ‘softening’ when geminate, and therefore retain their hard pronunciation in verb and noun stems that contain a dagesh.

Now let’s leave the technicalities aside and dive into the verb stems’ individual meanings.

פִּעֵל is one of the most common verb stems in the language, and can take a wide variety of different meanings. From standard active verbs:

דִּבֶּר diber ‘to speak’ סִפַּר siper ‘to tell; to cut hair’ צִלֵּם tsilem ‘to photograph’

To more ‘powerful’ version of equivalent פָּעַל verbs:

שָׁבַר shavar ‘to break’ - שִׁבֵּר shiber ‘to break (purposefully)’ שָׁמַר shamar ‘to save’ - שִׁמֵּר shimer ‘to conserve’ חָשַׁב chashav ‘to think’ - חִשֵּׁב chishev ‘to calculate’

Or even causative verbs, like הפעיל:

גָּדַל gadal ‘to grow’ - גִּדֵּל gidel ‘to grow (e.g. a plant)’ קַר qar ‘cold’ - קֵרֵר qerer ‘to cool’ חַם cham ‘hot’ - חִמֵּם chimem ‘to heat’

In short, it’s a very versatile verb stem that carries a multitude of different, sometimes unrelated meanings.

פֻּעַל, much like הֻפְעַל, is the passive counterpart of פִּעֵל. No more, no less.

שִׁמֵּר shimer ‘to conserve’ - שֻׁמַּר shumar ‘to be conserved’ חִשֵּׁב chishev ‘to calculate’ - חֻשַּׁב chushav ‘to be calculates’ גִּדֵּל gidel ‘to grow’ - גֻּדַּל gudal ‘to be grown’ קֵרֵר kerer ‘to cool’ - קֹרַר qorar ‘to be cooled’

הִתְפַּעֵל is an interesting stem. It is the only third stem in a group, which poses the question: what meaning can it have? Both other groups have just an active stem (פָּעַל, הִפְעִיל, פִּעֵל) and a passive stem (נִפְעַל, הֻפְעַל, פֻעַל), so there’s no other ‘third stem’ you can compare it to and deduce its general meaning from.

That is, until you look at נִפְעַל again: As I said in lesson 3, many נִפְעַל verbs are passive counterparts to פָּעַל verbs, but many others are not: there are also stative verbs and verbs denoting processes. What I failed to say, however, is that some of these are reflexive verbs, where the subject acts upon themselves, in a way. The verb נֶעֱמַד ‘to stand up’ (which I deemed a verb describing the process of standing up) can also be seen as ‘to set oneself up’ - or the reflexive counterpart of הֶעֱמִיד ‘to set up,’ itself the causative form of עָמַד ‘to stand,’ or ‘to be standing’ (as in, to cause something/someone to stand up).

הִתְפַּעֵל’s main meaning is the reflexive form of many, but not all, פִּעֵל verbs:

סִפַּר siper ‘to tell; to cut hair’ - הִסְתַּפֵּר histaper ‘to have a haircut’ קֵרֵר qerer ‘to cool’ - הִתְקָרֵר hitqarer ‘to become cold (to make oneself cold)’ חִמֵּם chimem ‘to heat’ - הִתְחַמֵּם hitchamem ‘to become hot (to make oneself cold)’ צִלֵּם tsilem ‘to photograph’ - הִצְטַלֵּם hitstalem ‘to have one’s picture taken’

Another different, yet related meaning is reciprocity. Reciprocal verbs are verbs where the given action is performed mutually in-between a pair or group. This might seem like a difficult quality to grasp, but in reality in isn’t very complicated. For instance:

כָּתַב katav ‘to write’ - הִתְכַּתֵּב hitkatev ‘to correspond by text (to write to one another)’ לָחַשׁ lachash ‘to whisper’ - הִתְלַחְשֵׁשׁ hitlachshesh ‘to whisper to one another’* *Consonant reduplication helps emphasize the reciprocal meaning of the verb דִּבֶּר diber ‘to speak’ - הִדַּבֵּר hidaber ‘to communicate by speech (to talk to one another)’** **This is a very tricky verb to translate, since it is quite rare outside of mediation circles

Some of these verbs have difficult translations, mostly because such a concept doesn’t really exist in English. But a point you need to remember throughout your language studies is that translations aren’t language. To learn a language, you should not rely on translations to understand a given text. Every language has its unique grammatical constructions and ways of speech that might not be translatable to English. This is especially prevalent among languages distant to English (an example close to me is Korean, which I have been studying myself), and although Hebrew and English sentence structure is relatively similar, they still have vastly different grammar.

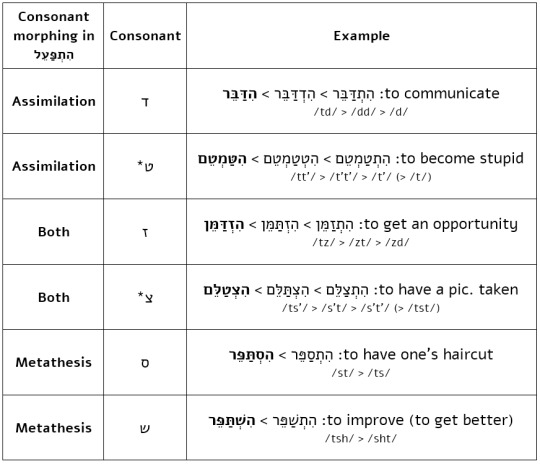

If you have a keen eye you might have noticed some strange pronunciations that seem to deviate from the regular הִתְפַּעֵל pattern:

הִסְתַּפֵּר histaper ‘to have a haircut’ הִצְטַלֵּם hitstalem ‘to have one’s picture taken’ הִדַּבֵּר hidaber ‘to communicate by speech (to talk to one another)’

One reason behind this is assimilation, where a consonant’s pronunciation changes because of the surrounding consonants. This is done by speakers in order to make pronunciation easier. For example, if you insert the root ד־ב־ר into the הִתְפַּעֵל stem you should get *הִתְדַּבֵּר hitdaber. However, the /td/ consonant cluster is hard on the tongue, so over time the /t/ assimilated into the /d/ to form a consonant cluster /dd/, or one geminate /d/ consonant (which eventually got to be pronounced only as one /d/): הִתְדַּבֵּר > הִדְדַּבֵּר > הִדַּבֵּר.

Another reason is consonant metathesis, where two consonants change places in order to make pronunciation easier. This can be seen in הִסְתַּפֵּר histaper, where the /s/ and the /t/ switched places to make a /ts/ cluster into an easier /st/ cluster: הִתְסַפֵּר > הִסְתַּפֵּר.

Explaining the change for each consonant combination is cumbersome, so here’s a list of changes:

ט and צ, marked with an asterisk, are quite complicated. You probably noticed I wrote them as /t’/ and /s’/ instead of plain /t/ and /ts/. This is because they weren’t all pronounced as they are today. If you recall, in lesson 1 I recalled many “historical reasons” that there are so many homophones in Hebrew. This is because over its history in the diaspora, certain communities (namely Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews) merged many of those consonants, and in modern times, since the Sephardi reading of the Bible was adopted as the pronunciation of Hebrew after its revival - these mergers stuck. Among these, Sephardim and Ashkenazim merges ת and ט. Originally it was pronounced as an “emphatic” consonant, meaning it came more “from the throat” (If you are familiar with Arabic, it was pronounced like Arabic ط): hence I wrote it as /t’/.

צ was pronounced differently between communities, but originally it was pronounced similarly to ט, “from the throat” (like Arabic ص). However, the Ashkenazi pronunciation /ts/, as if it were a combination of ס and ת, stuck in Modern Hebrew.

The different consonant morphings happened centuries before the Jewish diaspora, so the consonants were still pronounced as they were originally. Back then it was easier to pronounce /s’t’/ than /s’t/ because both consonants were emphatic, so it morphed. These days it seems pointless, since ט and ת have the same phonetic value, but the correct spelling is nonetheless הִצְטַלֵּם. Many speakers make the mistake of writing הִצְתַּלֵּם, but it is just that - a spelling mistake.

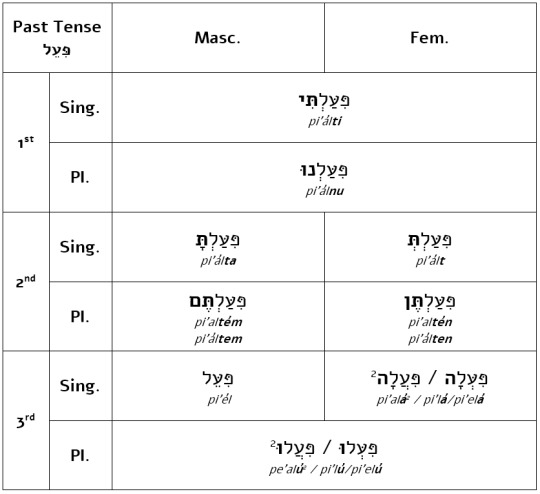

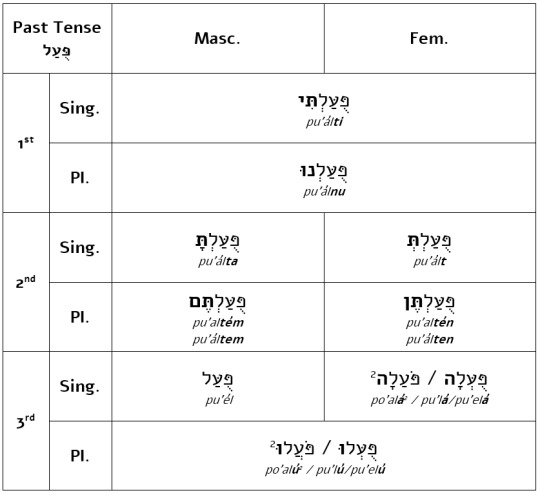

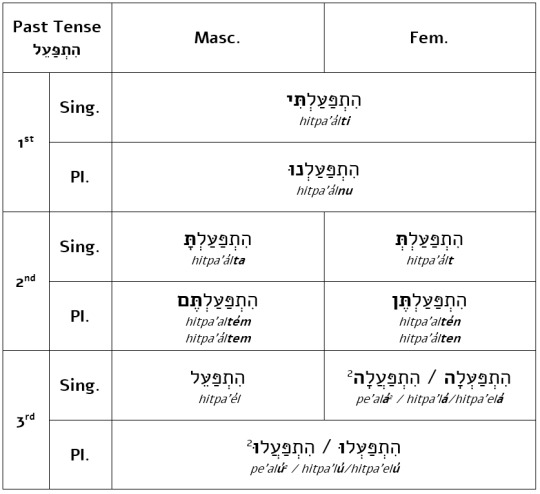

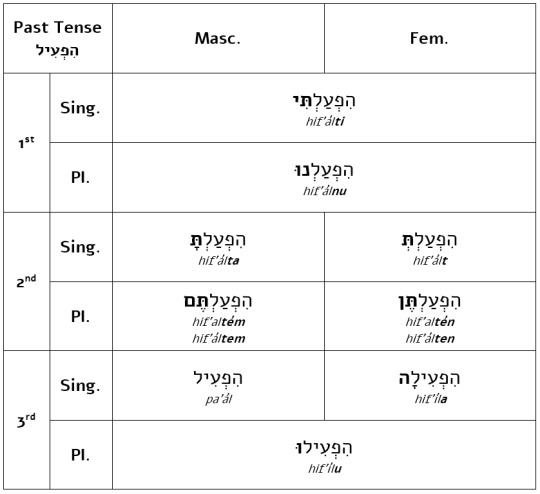

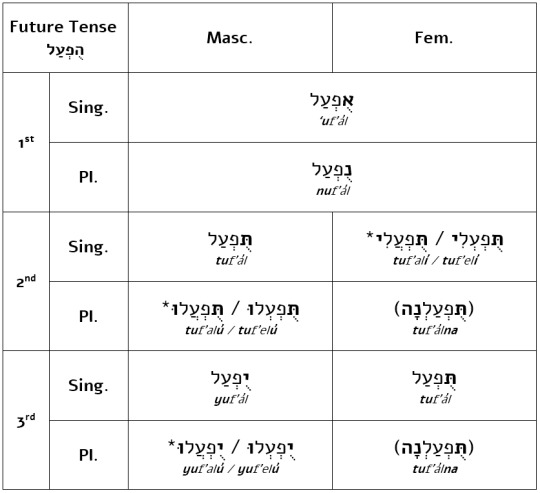

Past Tense

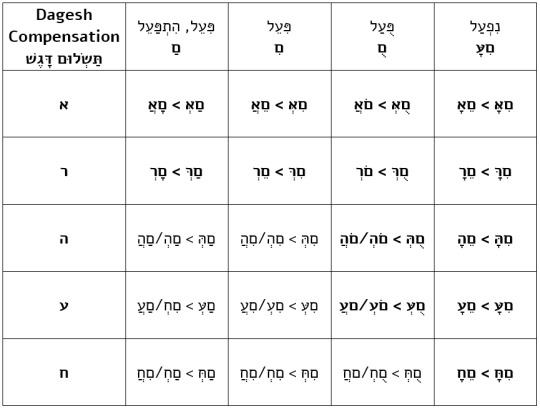

Verbs marked with 2, as usual, undergo vowel reduction that turns a shva into a hataf /a/ (סֲ) under certain guttural letters, but you might have noticed something particularly strange in these verbs under the פֻּעַל stem - the characteristic /u/ (סֻ) changes to an /o/ (סֹ). This is because of a phenomenon in Hebrew called “dagesh compensation,” תַּשְׁלוּם דָּגֶשׁ tashlum dagesh, where the vowel before a guttural letter with a dagesh gets intensified to accommodate the reduction of the dagesh.

Dagesh compensation typically happens in the double stems, however it occurs in נִפְעַל as well, in future tense conjugations. It goes as follows:

I marked where compensation occurs in bold, because it does not occur before every guttural letter.

Take note that although the vowel point changes in the first column, םַ, the pronunciation actually stays the same.

Furthermore, each letter handles vowel reduction differently, as you can see. א always takes a hataf (םֱ, םֲ, םֳ) instead of a shva, ר never, and under ה, ע, ח whether the shva changes to a hataf changes on a case to case basis. Keep in mind that this also means the pronunciation is different: when the reduced vowel is rendered as a םְ it can be pronounced either as a /e/ or as no vowel, depending on the following consonant; when it is rendered as a hataf it can be pronounced either as /a/, /e/ or /o/, depending on the identity of the hataf.

If the guttural vowel has any vowel other than םְ, it is conserved and does not change in spite of the vowel intensification (a can seen in the last column, נִפְעַל).

I didn’t write the vowel forms in the tables according to the correct compensated forms (due to the 2nd radical of פ־ע־ל being a guttural) because that would mean a very messy table. I expect you to think for yourselves and write for yourself what the correct forms of the verbs, taking dagesh compensation into account. It isn’t that hard actually, just knowing where /i/ becomes /e/ and when /u/ becomes /o/. (I did, however, include two forms when the vowel on the 2nd radical gets reduced, because that’s what I’ve been doing until now and I like consistency)

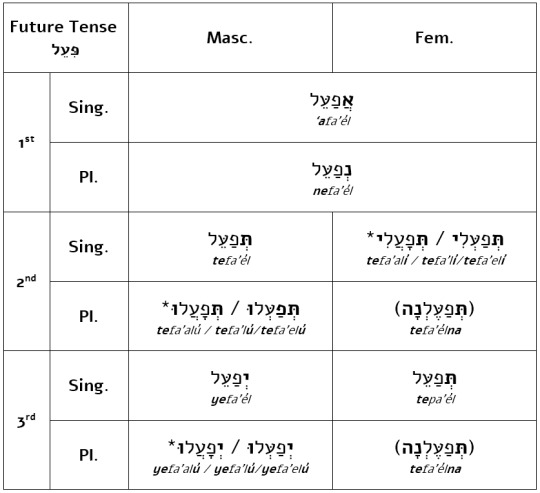

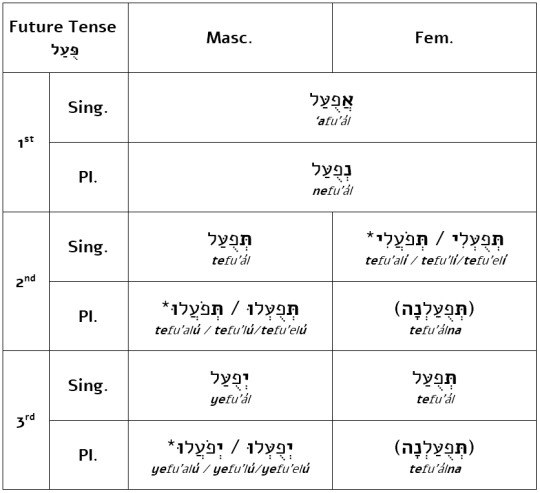

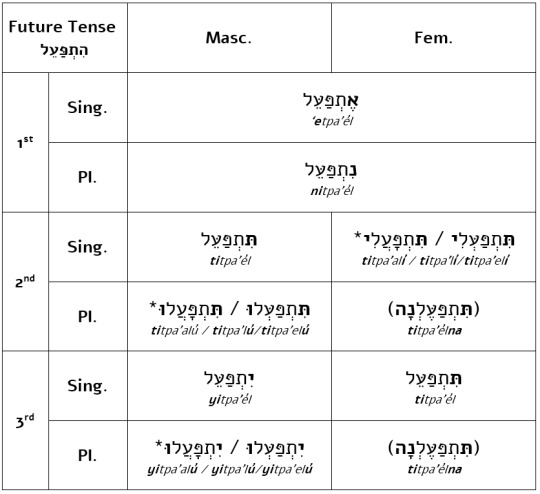

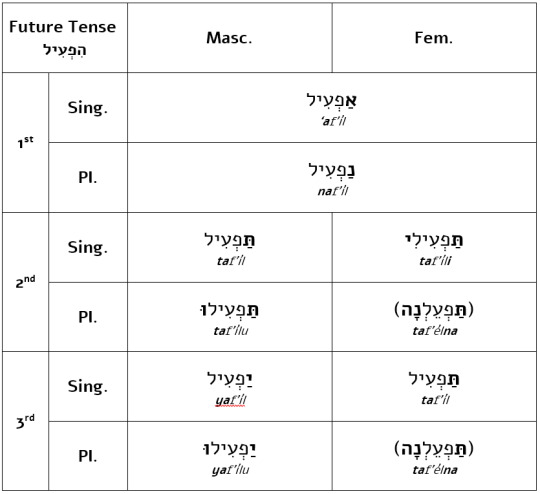

Future Tense

1st person conjugations have a different bowel of the prefix (א־) because the vowel on the א either changes to a hataf (אְ > אֲ) or it intensifies (אִ > אֶ).

Luckily that’s all There needs to be explained here. Everything peculiar here, you should already know the answer to from previous lessons

That’s it!

Next lessons I’ll be delving into the present tense and infinitives. Until then - keep your eyes peeled for more lessons!

See you next time :)

#Hebrew#Hebrew language#Learn Hebrew#hebrew resources#hebrew study#ivrit#verbs#עברית#שפה עברית#לומדים עברית#שיעור עברית#Hebrew Lesson#hebrewing

52 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hebrew Basics #4: Verbs, pt. 2 - הִפְעִיל & הֻפְעַל

In lesson 3 you learned basic verb morphology, as well as the two common verb stems פָּעַל and נִפְעַל.

This time we’re going to look at another pair of verb stems - הִפְעִיל and הֻפְעַל.

As you remember from last lesson, each verb stem has a unique meaning it contributes to each verb. These two stems are no exception.

הִפְעִיל carries a causative meaning - a הִפְעִיל verb usually carries the connotation of a subject causing an object to be or act a certain way. For example:

אָכַל akhal ‘to eat’ - הֶאֱכִיל he’ekhil ‘to feed (to cause to eat)’ גָּדַל gadal ‘to grow, to be big’ - הִגְדִּיל higdil ‘to enlarge (to cause to be big)’ כָּתַב katav ‘to write’ - הִכְתִּיב hikhtiv ‘to dictate (to cause to write)’

Note that not all verbs can be converted into a causative form with this stem. While you can make someone eat using one word הֶאֱכִיל, you cant make someone save something by using the verb *הִשְׁמִיר - it just doesn’t exist in the language. For this there is a different auxiliary verb you’ll learn more about in upcoming lessons.

As well as constructing causative verbs, הפעיל also conveys the meaning of change , often expressed in English with the verb ‘to become.’ This is most commonly used with colors:

אָדֹם ‘adom ‘red’ - הֶאֱדִים he’edim ‘to become red, to redden’ צָהֹב tsahov ‘yellow’ - הִצְהִיב hitshiv to become yellow’ כָחֹל kachol ‘blue’ - הִכְחִיל hikhchil1 / hikchil ‘to become blue’ שָׁחֹר shachor ‘black’ - הִשְׁחִיר2 hishchir ‘to become black, to blacken’ אָפֹר ‘afor ‘gray’ - הֶאֱפִיר he’efir ‘to become gray’ לָבָן lavan ‘white’ - הִלְבִּין2 hilbin ‘to become white, to whiten’

Please note that this cannot be done with all colors: כָּתֹ�� katom ‘orange’, סָגֹל sagol ‘purple’ and וָרֹד varod ‘pink’ do not have a corresponding הפעיל form, while the form for יָרֹק yarok ‘green,’ הוֹרִיק horik, is especially rare.

But can also be used with other adjectives and words:

חָשׁוּךְ chashukh ‘dark’ - הִחְשִׁיךְ2 hichshikh ‘to become dark, to darken’ בָּהִיר bahir ‘light, bright’ - הִבְהִיר2 hivhir ‘to become light/bright, to lighten/brighten’ זָקֵן zaqen ‘old’ - הִזְקִין hizqin ‘to grow old’ סֹמֶק someq ‘blush (n.)’ - הִסְמִיק hismiq ‘to blush’

1. The pronunciation hikhchil uses a double kh consonant, which is pretty hard to pronounce. Therefore it is more commonly pronounced hikchil. This is common with most words whose roots contain a כ-ח cluster.

2. Verbs marked with a 2 also carry the causative meaning ‘to cause to be black/white/dark/bright.’

הֻפְעַל is the passive counterpart to הִפְעִיל, and unlike נִפְעַל which you learned about last lesson, this is its only role. Yay! some simplicity, finally.

הֶאֱכִיל he’ekhil ‘to feed’ - הָאֳכַל ho’okhal / hu’akhal* ‘to be fed’ הִגְדִּיל higdil ‘to enlarge’ - הֻגְדַל hudgal ‘to be enlarged’ הִכְתִּיב hikhtiv ‘to dictate’ - הֻכְתַּב hukhtav ‘to be dictated’ הִשְׁחִיר hishchir ‘o blacken’ - הֻשְׁחַר hushchar ‘to be blackened’ הִלְבִּין hilbin ‘to whiten’ - הֻלְבַּן hulban ‘to be whitened’

* ho’okhal is the prescribed pronunciation, but is pretty uncommon - hu’akhal i far more common in everyday, as well as in formal speech.

Keep in mind that the passive mood is fairly uncommon in speech, as with most languages these days. It is more natural to express a given situation using an active verb than a passive verb.

You might have noticed הֶאֱכִיל ‘to feed’ and הָאֳכַל ‘to be fed’ have a weird pronunciation. The reason for this is that א is a guttural letter. Originally the verbs should be pronounced *הִאְכִיל hi’khil and *הֻאְכַל *hu’khal, but this is difficult to pronounce. You should be familiar with this phenomenon from last lesson. It happens with other verb stems too, but is especially prevalent in הִפְעִיל and הֻפְעַל because of their prefixes. In general it goes as follows:

םִאְ־ / םִעְ־ / םִהְ־ -i’- / -i’- / -ih- > םֶאֱ־ / םֶעֱ־ / םֶהְ־ -e’e- / -e’e- / -ehe- םַאְ־ / םַעְ־ / םַהְ־ -a’- / -a’- / -ah- > םַאֲ־ / םַעֲ־ / םַהֲ־ -a’a- / -a’a- / -aha- םֻאְ־ / םֻעְ־ / םֻהְ־ -u’- / -u’- / -uh- > םָאֳ־ / םָעֳ־ / םָהֳ־ -o’o- / -o’o- / -oho-

The last row is usually pronounced םֻאֲ־ / םֻעֲ־ / םֻהֲ־ -u’a- /-u’a- / -uha- in speech.

The first row corresponds to the הִפְעִיל past prefix and the נִפְעַל past and present prefixes (נִ־; הִ־), the second to הִפְעִיל present and future prefixes (נַ־, תַּ־, יַ־ ,אַ־; מַ־) and the last to all הֻפְעַל prefixes (הֻ־, נֻ־ ,תֻּ־, יֻ־, אֻ־, מֻ־).

As far as I know, this only happens to א, ה, ע. The other gutturals, ר, ח, take a shva like any other letter and verb prefixes preceding them stay the same.

Furthermore, situations where it would be very plausible to use passive verbs in English might not be the same in Hebrew. For instance, if you work at a petting zoo and your supervisor asks whether or not the goats were fed, in English you could say “The goats were fed an hour ago.” However, this isn’t quite the case for Hebrew. Instead of saying:

הָעִזִּים הָאֳכְלוּ לִפְנֵי שָׁעָה. - The goats were fed an hour ago.

It would more commonly be said as:

הֶאֱכִילוּ אֵת הָעִזִּים לִפְנֵי שָׁעָה. - (They) Fed the goats an hour ago.

Although the subject of the sentence (they) can be deduced solely through the conjugation of the verb, it is effectively omitted. Thus it is made irrelevant to the sentence. This is the same effect using a passive verb would convey, since it does not require stating the subject either. Using the 3rd person plural conjugation of the verb doesn’t necessarily mean some group of men did the action: it could be women, a single person, or even a non-human subject. In effect, they acts as a dummy subject, only there to fill in the blank because the language doesn’t allow a sentence without a subject.

The vague they is a very common construction in Hebrew, used when the subject is irrelevant to the sentence and the speaker wishes to emphasize the action itself, rather than the subject.

Conjugations

Now it’s time for your favorite part - conjugating!

The principles of verb conjugation are the same regardless of verb stem. However, each stem as some weird phenomena that require me to teach each one separately.

Past Tense

The first four rows are irregular to the conjugation, but you will see similar phenomena in the future. The stressed /i/ changes into an /a/ in some conjugations: הֶאֱכִיל > הֶאֱכַלְתֶּי he’ekhil > he’ekhalti, הֶאֱדִים > הֶאֱדַמֱתֶּם he’edim > he’edamtem. I did some research and apparently this change has no clear explanation, so take it as it is.

Future Tense

The forms marked with an asterisk are irregular and you should no why from last lesson. Here’s a reminder: Stress moves to suffix, 2nd radical letter gets reduced to a shva and since פ־ע־ל has a guttural ע it can’t take the shva, so it morphs to a /a/, marked as םֲ. Again, the right hand pronunciation is the general case, the left hand is the specific pronunciation for roots who have a guttural 2nd radical letter.

Yay! That’s it for this time.

I don’t think practice is really necessary here, so I won’t include any this time. Probably will next lesson.

See you next lesson!

#hebrew#hebrew lesson#hebrew lessons#hebrew language#learn hebrew#study hebrew#עברית#שיעור עברית#לומדים עברית#Ivrit#שפה עברית#lessons#verbs#basics

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

בִּשּׁוּל! Hebrew Cooking Vocab!

Yay! Cooking Vocab!

Utensils

סִיר sir, m - pot, saucepan ,anything with high walls you cook in מִכְסֶה mikhsé, m - lid מַחְבַת machvát, f - saucepan, skillet, anything flat you fry stuff on מָרִית marít, f - spatula מַטְרֵפָה matrefá, f - whisk מִסְנֶנֶת misnénet/mesanénet, f - colander, strainer (misnénet is the correct pronunciation, mesanénet is the more common one) נָפָה nafá, f - sieve מַזְלֵג mazlég, m - fork סָכִּין sakín, m or f - knife (Seriosuly, both genders work, it’s weird. I sometimes even mix feminine and maculine in the same sentence) כַּף kaf, m - (table)spoon כַּפִּית kapít, f - (tea)spoon סַכּוּ״ם sakúm, m pl. - silverware (acronym for סַכִּין, כַּף וּמַזְלֵג - knife, spoon and fork). מַקְלוֹת אֲכִילָה / צ׳וֹפְּסְטִיקְס maklót akhilá / chópstiks, m pl. - chopsticks פֻּמְפִּיָּה pumpiyá, f - grater תַּבְנִית tavnít, f - (cake, casserole, etc.) pan פּוֹתְחַן potchán, m - (can, bottle) opener כְּפָפוֹת תָּנוּר kfafót tanúr, f pl. - oven mitts מַעֲרוֹךְ ma’arókh, m - rolling pin מַכְתַּשׁ makhtésh, m - mortar עֵלִי ‘elí, m - pestle מַגֶּבֶת magévet, f - towel

Dishes

מָגָּשׁ magásh, m - platter צַלַּחַת tsaláchat, f - plate קַעֲרָה ka’ará, f - bowl קַעֲרִית ka’arít, f - small bowl צְלֹחִית tslochít, f - small bowl; flask כּוֹס kos, f - cup, glass סֶפֶל séfel, m - mug בַּקְבּוּק baqbúq, m - bottle קַנְקַן qanqán, m - jug, pitcher פַּחִית pachít, f - can צִנְצֶנֶת tsintsénet, f - jar

Appliances

תָּנוּר tanúr, m - oven כִּירַיִם kiráyim, f dual (effectively pl.) - stove טוֹסְטֶר tóster, m - toaster מִיקְרוֹגַל míqrogal, m - microwave oven מִיקְסֶר míkser, m - mixer בְּלֶנְדֶּר / מְעַרְבֵּל blénder / me’arbél, m - blender קוּמְקוּם qumqúm, m - kettle קַנְקַן תֵּה/קָפֶה qanqán te/qafé, m - tea/coffee pot מַקְרֵר meqarér/maqrér, m - refrigerator (maqrér is an uncommon mispronuncioation, often thought of as being the correct one) מַקְפִּיא maqpí, m - freezer

Actions

Verbs, as usual, are in the 3rd person, masculine, singular, past tense conjugation.

בִּשֵּׁל bishél - to cook (in general) חָלַט chalát - to blanch, to parboil (whatever that is) טִגֵּן tigén - to fry צָרַב tsaráv - to sear אִדָּה ‘idá - to steam אָפָה afá - to bake חָתַךְ chatákh - to cut פָּרַס parás - to slice קָצַץ qatsáts - to chop, to mince טָחַן tachán - to grind (e.g. beef), to puree, to blend (e.g. soup) מַָעַךְ ma’ách - to mash חִמֵּם chimém - to heat קֵרֵר qerér - to cool עִרְבֵּב ‘irbév - to mix טָרַף taráf - to whisk; to devour (unrelated) הִקְצִיף hiqtsíf - to whip (e.g. eggs) קִפֵּל qipél - to fold (e.g. meringue) הִתִּיךְ hitíkh - to melt הֵמִיס hemís - to melt (technically incorrect, but it’s more widely used) הִשְׁרָה hishrá - to soak, to marinate מָדַד madád - to measure רָתַח ratách - to boil, to be boiling הִרְתִּיח hirtíach - to boil, to cause to boil (in a pot or a kettle)

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hebrew Basics #3: Verbs, pt. 1 - Basics, פָּעַל & נִפְעַל

Yay! Verbs!

I bet you’ve been dying to know about verbs ever since last lesson you learned about sentence structure. Well - Here it comes!

Verbs are arguably the most important part of speech in a spoken language. They convey the core meaning of a sentence and in many cases simply knowing the verb is enough to know the meaning of a sentence. Therefore I found it fitting to teach them at such an early stage of this series - now!

Hebrew verbs are generally made of two components: a root (שֹׁרֶשׁ shóresh) and a stem (בִּנְיָן binyán - literally meaning ‘building’). The root contributes the consonants and the stem contributes the vowels (along with its intrinsic prefixes), both make up the full word. Think about it like this: the verb ‘meet’ has its consonants (m-t) and its vowels (ee), both make up the verb. Of course, in English it works nothing like that, but that is the basic morphology of Hebrew verbs: the verb פָּגַשׁ pagásh ‘he met’ has its conosnants פגשׁ and its vowels םָםַם.

Unlike English, where any word can just be put in the middle of a sentence and suddenly become a verb, all Hebrew verbs have to be comprised of a verb and a root. New roots can be coined from loanwords (this is done quite a lot these days), but it always has to be the root that is coined and inserted into an existing stem.

Each verb can be thought of as a plant of sorts. With a consonant root, a vowel stem, and leaves. The leaves, of course, are the different conjugations applied to it - person, number, tense and more (there are not called leaves though!!! that’s just weird). However unlike an actual plant, different leaves can be applied that change the overall pronunciation (which can be thought of as the shape of the plant)

Roots

Roots provide the core meaning to any word in Hebrew. Native roots are almost always comprised of three consonants, with some rare native verbs comprised of four. For example: the root שׁ־מ־ר sh-m-r carries the meaning ‘to keep, to save,’ the root א־כ־ל ‘-k-l carries the meaning ‘to eat’ and the root מ־ל־ח m-l-ch carries the meaning ‘salt.’ Combining them with different verb and noun stems creates different words, whose meanings all relate to the meaning of the original root:

שׁ־מ־ר - to keep, to save: שָׁמַר shamár ‘to save, to keep,’ שִׁמֵּר shimér ‘to conserve,’ שׁוֹמֵר shomér ‘guard’, etc. א־כ־ל - to eat: אָכַל ‘akhál ‘to eat,’ אִכֵּל ‘ikél ‘to corrode,’ אֹכֶל ‘ókhel ‘food’, etc. מ־ל־ח - salt: מֶלַח mélach ‘salt,’ מָלוּחַ malúach ‘salty,’ הִמְלִיחַ himlíach ‘to salt (food),’ etc.

Side note: roots can be written in a number of ways. Using hyphens or maqafím (Hebrew hyphens; פ-ע-ל or פ־ע־ל), gersháyim (פע״ל), periods (פ.ע.ל) or even square root signs (√פעל). I prefer hyphens and maqafim.

A term that’ll come up frequently (that I think I just made up) is radical letter (from Latin radix, meaning ‘root’). By saying that I refer to the letter of the root as they’re pronounced in the word. In the root פ־ע־ל p-’-l, פ is the 1st radical, ע the 2nd and ל Is the 3rd radical letter. In the word נִפְעַלְנוּ each letter פ, ע, ל will be referred to as the 1st, 2nd and 3rd radical letter in the word respectively. For each root, they do not appear in a different order no matter how you manipulate them. The root ח־ט־ב ch-t-b (‘to log/cut trees’) is fundamentally different to the root ח־ב־ט ch-b-t (‘to hit’), for example.

Some roots have irregular conjugations, depending on the consonants they have. Each irregular conjugates differently under each stem, and you will learn more about that later on. Other than that, roots are pretty straightforward. Stems are where things get interesting.

Stems

Hebrew has seven verb stems. They’re named by inserting the root פ־ע־ל p-’-l, meaning ‘verb’ or ‘action’ into the most basic conjugation of the stem - 3rd person, masculine, singular, past tense. The stems are:

- פָּעַל pa’ál (also called קַל qal) - נִפְעַל nif’ál

- הִפְעִיל hif’íl - הֻפְעַל huf’ál

- פִּעֵל pi’él - פֻּעַל pu’ál - הִתְפַּעֵל hitpa’él

The stems are divided in groups of two (and one of three), where each has an active stem and a passive stem.

I’ll be teaching more about each stem in upcoming lessons. This lesson I’ll be concentrating on the first two: פָּעַל pa’ál & נִפְעַל nif’ál. These are the two most basic stems.

פָּעַל is the simplest and most common stem in the language. Verbs of this stem generally have only a basic meaning directly related to the meaning of the root. for example: שָׁמַר shamár ‘to save, to keep,’ אָכַל ‘akhál ‘to eat.’

נִפְעַל is generally considered its passive counterpart. For most פָּעַל active verbs, there is a נִפְעַל passive counterpart: נִשְׁמַר nishmár ‘to be saved, to be kept,’ נֶאֱכַל ne’ekhál ‘to be eaten.’ However, contrary to other passive stems, not all נִפְעַל verbs are passive. For example, the verb סָגַר sagár means ‘to close (a door),’ and its passive counterpart is נִסְגַּר nisgár ‘(for a door) to be closed.’ However, the same verb נִסְגַּר nisgár also means ‘to close,’ as in “the door is closing,” without stating whether someone closed it, or it closed by itself. To put it differently: נִפְעַל has a double role, as a passive verb stem (describing a subject who is being acted upon), and as a stative verb stem (describing a state the subject is in).

Other examples are:

שָׂרַף saráf ‘to burn’ - נִשְׂרַף nisráf ‘to be burnt’ or ‘to be burning’ רָאָה ra’á ‘to see’ - נִרְאָה nir’á ‘to be seen’ or ‘to seem’ צָפָה tsafá ‘to watch’ - נִצְפָּה nitspá ‘to be watched’

Another different nuance נִפְעַל has is to describe some sort of process, usually changes in position. For instance, you would use שָׁכַב shakháv to describe someone who is already lying on a bed, whereas you would use נִשְׁכַּב nishkáv to describe someone in the process of lying down onto a bed. Other examples are:

עָמַד ‘amád ‘to stand’ - נֶעֱמַד ne’emád ‘to stand up / be standing up’ שָׁפַךְ shafákh ‘to pour’ - נִשְׁפַּךְ nishpákh ‘to be poured’ or ‘to pour in/out’ (“The water poured out of the bottle.”) שָׁבַר shavár ‘to break’ - נִשְׁבַּר nishbár ‘to be broken (by someone)’ or ‘to break’ (“My arm broke.”)

Generally, the one aspect in common with all נִפְעַל verbs is that none of them can take direct objects; but that’s about it.

Now let’s talk conjugations!

There are only three tenses–past, present and future–and constructions such as perfect and progressive tenses simply don’t exist.

The most important part to about conjugating Hebrew verbs is knowing their tense. As you know, verbs are always conjugated according to person, number, gender and tense. Within each tense the conjugations share many similarities, however between the tenses the patterns vary considerably.

Past Tense

Past tense conjugations are characterized by suffixes. For each person-gender-number combination a unique suffix is added which encodes information for all three of these. They are as following:

Before I begin explaining, I need to say one more thing. When talking about verb conjugations, syllable stress plays a big role in pronunciation, as you will see in the next paragraphs. Stress in Hebrew words classically falls in one of two places: the ultimate (last) syllable, or the penultimate (second-to-last) syllable. Colloquially, it can fall on other syllables, especially in proper names and loanwords, but this is technically incorrect.

The first three rows are very simple - just add the corresponding suffix to the basic verb form, and that’s it. שָׂרַף > שָׂרַפְתִּי saráf > saráfti (‘burn’), נִשְׁבַּר > נִשְׁבַּרְתְּ nishbár > nishbárt (‘break’).

The fourth row, 2nd person plural, marked with a 1, works similarly, yet there are some notable differences. The stress moves to the last syllable (the suffix), instead of staying on the 2nd radical letter, as with other conjugations. As a consequence, the 1st radical letter in the פָּעַל stem gets reduced to a shva (the null vowel point): שָׂרַף > שְׂרָפְתֶּם saráf > sraftém. As with the copula you learned last lesson, informally it is pronounced as if it was like the first three rows: שָׂרַף > שָׂרַפְתֶּם saráf > saráftem.

The double pronunciation situation going on with these (in the formal pronunciation) is because some clusters are easily producible while others aren’t. When the first letter can be easily clustered it is pronounced with a null vowel, when it isn’t it is pronounced with an /e/ (rarely as /a/). For example: שָׁמַר > שְׁמַרְתֶּם shamár > shmartém; but מָרַח < מְרַחְתֶּם marách > merachtém (‘smear, lather’), and עָרַך > עֲרַכְתֶּם ‘arákh > ‘arakhtém (‘set (a table); edit’).

The last two rows are a bit more complicated. Instead of being pronounced with the stress still on the 2nd radical letter, it also moves to the suffix. However, here it is the 2nd radical that gets reduced to a shva. שָׂרַף > שָׂרְפָה saráf > sarfá, נִשְׁבַּר > נִשְׁבְּרוּ nishbár > nishberá. Consonant clusters of more than 2 consonants aren’t possible, so the shva in the נִפְעַל conjugation is pronounced as a /e/ instead of as no vowel.

You might’ve noticed the last rows, marked with a 2, have that pesky double pronunciation going on. This is because פ־ע־ל p-’-l is an irregular root.

As I’ve said earlier, roots are irregular depending on their letters. In פ־ע־ל, the ע is the irregular. It is part of the guttural letters, called so because they’re classically pronounced deep in the throat (guttur in Latin). These letters are א, ה, ח, ר, ע, contracted as הָאָ״ח רַ״ע / רֵ״עַ (ha’ách ra’ ‘the brother is bad’ or ha’ách réa’ ‘hooray, a friend’). Three of these letters–א, ע, ה–cannot take a null shva (שְׁוָא נַח), simply because it is hard to pronounce. (The other two can, but also give rise to some problems in other instances.) Therefore they are usually pronounced with a dummy vowel inserted, depending on the surrounding vowels. This dummy vowel is usually notated as a tnu’á hatufá (סֱ סֲ סֳ) - hence the complicated origin I didn’t explain in the 1st lesson!

The right pronunciation, not marked with the 2, is the general case. The left one is the specific pronunciation with the gutturals.

Future Tense

While the past tense is characterized by suffixes, the future tense is characterized by prefixes, sometimes combined with suffixes. These prefixes are always one of four letters: א, י, ת, נ - contracted as אֵיתָ״ן eytán. It is fairly simple, and goes as following:

The variation between /o/ and /a/ is weird and really only depends on the verb. The only way to know which it is is to memorize: it’s תֹּאכַל tokhal (‘she will eat’) and תִּפְתַּח tiftach (‘she will open’), but תִּשְׁבֹּר tishbor (‘she will break’) and תִּשְׂרֹף tisrof (‘she will burn’).

As you can see, the characteristic נ prefix of the נִפְעַל stem is gone in the future conjugations. This is because it underwent full assimilation into the following consonant (effectively it melted into the following consonant): יִנְשָׁבֵר > יִשְׁשָׁבֵר > יִשָּׁבֵר yinshavér > yisshavér > yishavér. The dagesh in the 1st radical letter signifies that assimilation, as will be explained in a future lesson. An important consequence of this is that any בג״ד כפ״ת letters in the 1st radical position are pronounced hard, in all future נִפְעַל conjugations.

The irregular conjugations are marked with an asterisk in both tables. These have double pronunciations for the same reason as in the past conjugations: the word-final stress causes the 2nd radical letter to be reduced, and because the root פ־ע־ל p-’-l has a guttural 2nd letter (ע), it cannot be pronounced with the reduced shva and gets a reduced /a/ instead. Again: the right pronunciation is the general case, while the left is specific to gutturals.

2nd and 3rd person feminine plural conjugations, as you can see, are put in parentheses. This is because, as you remember from last lesson about copulae, these days the feminine and masculine conjugations have merged into the masculine form. It would be very rare these days to see a 2nd or 3rd person female plural verb conjugated as תִּפְעַלְנָה / תִּפָּעֶלְנָה instead of יִפְעַלוּ / יִפָּעֲלוּ. This is true for all verbs, so I’m not going to say this after teaching each stem’s conjugations.

Before I move on I need to make one remark about the obviously missing tense - present tense. The present tense in Hebrew works differently to the two others, so I found it more suitable to introduce it after I finish past and future for all stems/

Exercise

OK so that was quite a bit for one lesson - but it doesn’t mean you don’t need to exercise what you’ve just learned!

For the next ten lessons, I’ll leave out the verb and you need to fill it out according to the root and tense given. Each subject will have its pronoun in parentheses (if it isn’t a pronoun anyway), so you can practice those too. On we go!

1. הַכֶּלֶב [הוּא] ___ הַרְבֵּה בָּשָׂר. (past, א־כ־ל)

2. אֲחוֹתִי [הִיא] ___ מֵהַלִּמּוּדִים. (past, פ־ר־שׁ)

3. הֵם ___ אֵת הָעֵץ. (future, שׂ־ר־פ)

4. רֹאשׁ הַמֶּמְשָׁלָה רַבִּין [הוּא] ___ לְטוֹבַת הַשָּׁלוֹם. (past, פ־ע־ל)

5. אֲנִי ___ עַצִים רַבִּים. (future, ח־ט־ב)

6. אַתָּה ___ לֹא נָכוֹן. (past, ח־שׁ־ב)

7. הָחֲתוּלוֹת [הֵן] ___ הַרְבֵּה עִם הַשָּׁנִים. (future, ג־ד־ל)

8. אֲתֶּן ___ אֵת הַשֻּׁלְחַן. (past, שׁ־ב־ר)

9. אַתְּ ___ אוֹתוֹ מְאֹד. (past, א־ה־ב)

10. אֲנַחְנוּ ___ שָׁם. (past, י־שׁ־ב)

Answer Key:

1. אָכַל. hakélev akhál harbé basár. “The dog ate a lot of meat.”

2. פָּרְשָׁה. achotí parshá mehalimudím. “My sister dropped out of school.”

3. יִשְׂרְפוּ. hem yisrefú et ha’etsím. “They will burn the tree / wood.”

4. פָּעַל. rósh hamemshalá Rabín pa’ál letovát hashalóm. “Prime Minister Rabin acted towards peace.”

5. אַחֲטֹב / אַחְטֹב. aní achtóv / achatóv etsím rabím, “I will log / cut down many trees.”

6. חָשַׁבְתָּ. atá chashávta lo nakhón. “You were thinking wrong,”

7. תִּגְדַלְנָה / יִגְדְּלוּ. hachatulót tigdálna / yigdelú harbé ‘im hashaním. “The cats will grow up a lot as years go by.”

8. שְׁבָרְתֶּן. atén shvartén et hashulchán. “You broke the table.”

9. אָהַבְתְּ. at ahávt otó me’ód. “You liked him a lot.”

10. יָשַׁבְנוּ. anáchnu yashávnu sham. “We sat / were sitting there.”

That’s it for this lesson!

Talk about dense information.

Next lessons I’ll be explaining the conjugations of the other two verb stem groups (הִפְעִיל&הֻפְעַל, פִּעֵל&פֻּעֵל&הִתְפַּעֵל), then the elusive present tense. They won’t be as information dense, hopefully, since I already explained a lot of the basics this lesson.

Stay Hebrewing ;)

#hebrew#learn hebrew#hebrew lesson#study hebrew#hebrew language#ivrit#עברית#לומדים עברית#שיעור עברית#lessons#basics#verbs

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hebrew Basics #2: Pronouns, Sentence Structure

Hi Again!

Now that you’ve hopefully started to get Hebrew writing, it’s time to start with the language itself, beginning with the very base of the language - basic language structure.

First and foremost, here is a table of personal pronouns, since they’re pretty necessary for this lesson, and don’t require too much explaining behind them:

An easy way to remember them is:

1st person pronouns always start with אֲנ an-.

2nd person pronouns also always start with א alef, but always have a ת tav in them.

3rd person pronouns always start with ה he, and are monosyllabic.

Male plural pronouns always end in a מ mem, while female plural pronouns always end in a נ nun.

אֲנוּ ánu is pretty much only used in formal settings, speeches, documents etc., not even in Biblical texts (it rose later in history).

אָנֹכִי anokhí is archaic these days, used primarily in Biblical texts and in some set phrases (e.g. אֲנִי וָאָנֹכִי aní va’anokhí ‘me, myself and I’), as well as serving as an adjective meaning ‘selfish.’

Moreover, some speakers merge the 2nd and 3rd person masculine and feminine plural pronouns, using only the masculine form. I don’t like prescribing you a correct and an incorrect way to say something - but I’ll let myself do so here. This is a language changing as we speak, and as of now this in-distinction is still pretty much universally viewed as incorrect. You can, and probably will, see it online or in speech, but most speakers (at least those I speak to) still make the distinction, especially with verb conjugations (as explained further in the lesson), and some will correct you if you don’t make it yourself.

What you might have noticed as well is the lack of a neutral pronoun. Hebrew nouns are all either male or female, and to refer to an inanimate noun you would simply refer to it by its appropriate pronoun. שֻׁלְחַן shulchán (table) is of masculine gender, so one will refer to it as הוּא hu (he); קַעֲרָה ka’ará (bowl) is of feminine gender, so one will refer to it as הִיא hi (she).

Side note: as there are no gender neutral 2nd and 3rd person pronouns, this creates some problems in feminist and LGBT circles. It’s simply impossible to refer to a group of people by a gender-inclusive pronoun, neither is it possible to refer to someone without explicitly saying what binary gender your referring to them with.

Before I explain sentence types I need to set out word order. Since verbs are conjugated to encode tense, number, gender and person (1st, 2nd and 3rd persons) of the subject, Hebrew generally has pretty free word order. This is because it is usually clear who the subject is through conjugation and context. Another consequence of this is frequent dropping of subject pronouns, since it is already specified through the verb.

However, most sentences still fall under SVO word order - where the subject comes first in a sentence, then the verb, then any objects the subject acts upon. For example:

1. אָכַלְתִּי תַּפּוּחַ. akhálti tapúach. - I ate an apple. (literally: I-ate[S+V] apple[O].) 2. יוֹנָתָן לִטֵּף אֵת הַכֶּלֶב. Yonatán litéf et hakélev. - Yonatan pet the dog. (literally: Yonatan[S] pet[V] direct object preposition the dog[O].) 3. הַסַּפְרָן יִתֵּן לִי אֵת הַסֵּפֶר. hasafrán yitén li et haséfer. - The librarian (m) will give me the book. (literally: the-librarian[S] will-give[V] to-me[O] direct object preposition the-book[O].)

(Note: even if it doesn’t look like it, the period / full stop comes after the text - to the left. So do exclamation and question marks. Typing right-to-left text embedded in a left-to-right language is very annoying, so you should get used to punctuation, vowel points and generally everything to not fall where you actually put your cursor. It’s terrible. Also, vowel points don’t get bolded with the rest of the text?? w h y)

Occasionally, in more higher speech as well as in Biblical texts, Hebrew also shows VSO word order. Hence, all of these sentences could alternatively be said like so:

1. אָכַלְתִּי תַּפּוּחַ. akhálti tapúach. - I ate an apple. (literally: I-ate[S+V] apple[O].) 2. לִטֵּף יוֹנָתָן אֵת הַכֶּלֶב. litéf Yonatán et hakélev. - Yonatan pet the dog. (literally: pet[V] Yonatan[S] direct object preposition the-dog[O].) 3. יִתֵּן הַסַּפְרָן לִי אֵת הַסֵּפֶר. yitén hasafrán li et haséfer. - The librarian (m) will give me the book. (literally: will-give[V] the-librarian[S] to-me[O] direct object preposition the-book[O].)

In 1, the verb and the subject are conjoined, therefore flipping their order doesn’t make any sense and the sentence stays the same.

That being said, these days SVO word order is a lot more common that VSO, especially in speech, so don’t worry too much about it, just know it’s used. Personally, I tend to used VSO in some cases for school essays, but that’s about it - and even this is mostly my personal tendency. Again, don’t think about it too much.

Sentence Structure - Syntax!

Hebrew sentences are generally separated into two categories: verbal sentences and nominal sentences. A verbal sentence, מִשְׁפָּט פָּעֳלִי mishpát po’olí (more commonly pronounced po’alí), is a sentence that contains a subject (some type of noun or verb phrase) and an action verb, also called the predicate. This, you might recognize, is the basic sentence structure of English as well. In fact, the vast majority of languages only possess this type of sentence. Nominal sentences are where stuff gets interesting.

A nominal sentence, מִשְׁפָּט שְׁמָנִי mishpát shemaní, as you might have guessed, is a sentence where instead of a nominal subject and an action verb - there’s just another noun (or adjective) acting as the predicate. These are characteristic to Semitic languages and Russian (I’m not sure about other Slavic languages), among others. For example:

1. הַדֹּב הַזֶּה מְאֹד יָפֶה. hadóv haze me’ód yafé. - This bear is very pretty. (literally: bear this very pretty.) 2. אֲנִי רְעֵבָה. aní re’evá. - I am hungry. (literally: I hungry (female)) 3. הוּא כֶּלֶב. hu kélev. - He is a dog. (literally: he dog).

To negate the sentence, simply put לֹא

As you might have noticed, the key characteristic is where English would put the verb to be, Hebrew just doesn’t put anything, because there is no equivalent in Hebrew. The languages simply lacks a copula (the linguistic term for verbs like to be, whose purpose is linking the subject to a non-verb predicate).

Well… not quite.

You see, without a copula, there would be no way of indicating different tenses. When the sentence is word-for-word ‘I hungry’ or ‘he dog,’ where do you mark the tense? For this there’s a nice and clever solution - copulae! Yep, Hebrew didn’t wanna feel left out of the copula club so it made itself copulae of its own.

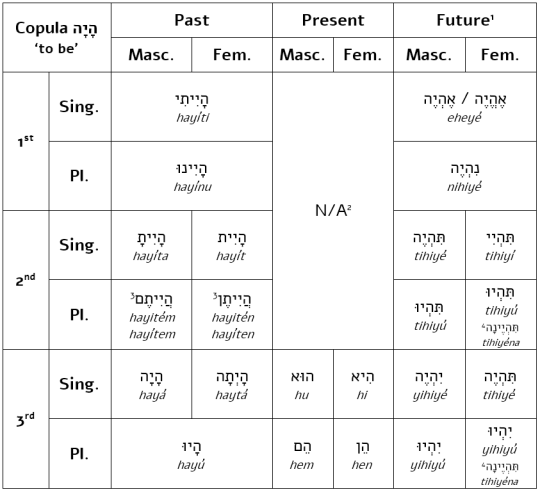

There are many types of copulae, to mark different types of relations, but for now I’ll introduce you to most common and most simple one. To mark present tense sentences use the 3rd person pronouns הוּא, הִיא, הֵם, הֵן, and for past and future tenses it uses conjugations of the verb הָיָה hayá*, ‘to be,’ as following:

*I refer to all verbs in this series with their 3rd person, masculine past tense form. This is because verb infinitives in Hebrew, as you will learn, are not a great way to represent the verb, and the 3rd person masc. form of a verb is considered the most basic form of the verb in all different conjugations.

If this seems like a lot to take in - it’s because it is. Hebrew verb conjugation is pretty complicated, and it doesn’t help that הָיָה hayá is quite an irregular verb. I don’t recommend you try and understand it fully, as I’ll be teaching everything you need to know about Hebrew verb conjugation pretty soon. For now, just take it at face value.

Notes:

If you have keen eyes, you might notice the /i/ after the /h/ in the transliteration of all future tense conjugations, that shouldn’t be there according to the vowel points. If not, notice it now. This is because it’s difficult to pronounce a /h/ without any consonant afterwards, so a dummy vowel was inserted after it. This is a common phenomenon in Hebrew with some consonants, but I won’t explain it now, as it’s quite complicated. (the different vowel points in the 1st person is just that I found two different vowel markings that seem to have no real difference between them)

For the present tense 1st and 2nd persons no copula is used. My guess is that this is because the subject can only ever be ‘I’ or ‘you’ when talking about 1st and 2nd person subjects, so repeating the same pronoun twice is useless. This is the case for 3rd person subjects as well: if the subject itself is ‘he,’ ‘she’ or ‘they,’ you don’t repeat the same pronoun as a copula.

This is getting a bit into verb conjugations, but the 2nd person plural past tense forms (now try saying that three times in a row) have two pronunciations: the top is the ‘correct’ one used formally, and the bottom is the one you’d actually hear pretty much everywhere, as it fits the conjugation pattern more regularly.

The 2nd and 3rd person feminine plural future tense conjugation, as marked on the table, is very rare nowadays, and shifting towards merging with the equivalent masculine conjugation. In fact, even the 2nd person plural past tense conjugations (marked with the 3), are starting to lose their distinction between masculine and feminine, just like the pronounced mentioned in the beginning of this lesson, but this is still widely considered a grammatical mistake and I do advise that you keep the distinction - people will just correct you otherwise.

The examples above in different tenses would be:

Past: 1. הַדֹּב הַזֶּה הָיָה מְאֹד יָפֶה. hadóv haze hayá me’ód yafé. - This bear was very pretty. (literally: bear this was very pretty.) 2. אֲנִי הָיִיתִי רְעֵבָה. aní hayíti re’evá. - I was hungry. (literally: I was hungry [female]) 3. הוּא הָיָה כֶּלֶב. hú hayá kélev. - He was a dog. (literally: he was dog).

Future: 1. הַדֹּב הַזֶּה יִהְיֶה מְאֹד יָפֶה. hadóv haze yihiyé me’ód yafé. - This bear will be very pretty. (literally: bear this will-be very pretty.) 2. אֲנִי אֶהֱיֶה רְעֵבָה. aní eheyé re’evá. - I will be hungry. (literally: I will-be hungry (female)) 3. הוּא יִהְיֶה כֶּלֶב. hú yihiyé kélev. - He will be a dog. (literally: he will-be dog).

Exercise

For the next 10 sentences, I’ll leave out the copula, and you should fill it in according to the tense and gender given in the brackets… if you even need the copula!!! muahahahaha

Don’t worry, they’re as simple as it gets.

1. הַכּוֹס ___ יְרֻקָּה. hakós ___ yeruqá. (fem. sing. past) 2. בְּנִי ___ חָכָם. bní ___ chakhám. (masc. sing. future) 3. מָסָךְ הַטֶּלֶוִיזְיָה שֶׁלִּי ___ לָבָן. masákh hatelevízya sheli ___ laván. (masc. sing. past) 4. הַלֵּב ___ הָאֵיבַר הֲכִי חָשׁוּב בַּגּוּף. halév ___ ha’evár hakhí chashúv bagúf. (masc. sing. present) 5. כְּרוּבִית ___ יֶרֶק. kruvít ___ yérek. (fem., sing., present) 6. מֶזֶג הָאֲוִיר מָחָר ___ קַר. mézeg ha’avír machar ___ kár. (masc. sing. future) 7. הֵן ___ בָּנוֹת נִפְלָאוֹת. hen __ banót nifla’ót. (fem. pl. present) 8. הַשֻּׁלְחַנוֹת שֶׁלָּהֶן ___ חֻמִּים. hashulchanót shelahen ___ chumím.(masc. pl. future) 9. הַהֲלִיכוֹן ___ מָהִיר מִדַּי. hahalichón ___ mahír miday. (masc. sing. past) 10. מִשְׁקָפַי ___ חֲזָקִים. mishkafái ___ chazaqím. (masc. pl. present)

Answer Key

1. הָיְתָה haytá (The cup was green.) 2. יִהְיֶה yihiyé (My son will be smart.) 3. הָיָה hayá (My TV screen was white.) 4. [הוּא] / - ; hu / - (The heart is the most important organ in the body.) 5. [הִיא] / - ; hi / - (Cauliflower is a vegetable.) 6. יִהְיֶה yihiyé (The weather tomorrow will be cold.) 7. - (They are wonderful girls.) 8. יִהְיוּ yihiyú (Their (f) tables will be brown.) 9. הָיָה hayá (The treadmill was too fast.) 10. הֵם / [-] ; hem / - (My glasses are strong.)

In the present tense examples I marked the option more likely to be heard with square brackets. I’m not sure why it is for each example, but the other option just sounds less natural.

Aaaaand that’s it for today!

Next time… Verbs??? probably

See you next week :)

לְהִתְרָאוֹת!

#hebrew#hebrew lesson#hebrew lessons#learn hebrew#study hebrew#עברית#לומדים עברית#שיעור עברית#hebrewing#hebrew basics#lessons#basics

405 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hebrew Basics #1: All about the Hebrew Alphabet

In order to learn a language, the very first thing you need to know is reading it. This is a basic step in all language studies. Hopefully you’ll start conquering that by the end of this lesson :)

The Hebrew alphabet… isn’t an alphabet. Technically speaking, it’s an “‘abjad” (an acronym of the first four letters of the Arabic ‘abjad), although it is commonly called an alphabet (as I’ll continue calling it for simplicity’s sake). Characteristic of Semitic languages (to which Hebrew belongs, among Arabic and many others, extinct and alive), the ‘abjad’s main characteristic is (almost) complete lack of vowels. Every letter stands for a consonant, and vowels are simply omitted. It’s equivalent to writing English “lk ths.”

While using an ‘abjad-like system with English is quite hellish, the case for Hebrew is quite different. Due to its relatively simple vowel system and unique Semitic grammar and morphology (how words are formed and act in a sentence), using an ‘abjad is actually quite a reasonable choice for Hebrew. Oversimplifying, Hebrew words are comprised of a root and a template, each contribute meaning to the final word. The root is comprised of (usually three) consonants, and the template describes the vowels, prefixes and suffixes you insert between and around the consonants.

The Letters

The Hebrew alphabet, called הָאַלֶף־בֵּית/אָלֶפְבֵּית הָעִבְרִי ha’álef-bét ha’ivrí, is comprised of 22 letters.

The first, most important fact is that Hebrew is read from right to left.

Note: the names aren’t all that important to learning the letters. Simply learning their pronunciation is enough at this point.

Five of the letters, for historical reasons, have two different forms - a word-initial and -medial form, and a separate final form. These are marked with a 1 on the table.

As you might have noticed, some letters have multiple pronunciations, and some of these overlap with one another. This was caused by many changes that happened to the language’s phonology over the years since the alphabet was created (some 3,000 years ago in its earliest forms).

The most notable of these letters are the בֶּגֶ״ד כֶּפֶ״ת* béged kéfet letters, marked with a 2. These days, for historical reasons**, only three letters actually change their pronunciation depending on their position in a word–ב bet, כ kaf, פ pe–and they are the only ones marked on the list, pronounced as /b~v/, /k~kh/, /p~f/, respectively. Generally speaking, for native words, at the beginning of a word and directly after a consonant (with no vowel in-between), they are pronounced with their ‘hard’ pronunciation (/b/ /k/ /p/), and in all other positions with their ‘soft’ pronunciation (/v/ /kh/ /f/). Loanwords do not follow these rules, and are pronounced as they are in the original language.

*Acronyms and initialisms, as well as Hebrew letter names and numerals, are marked by the Hebrew punctuation mark ״, called גֵּרְשַׁיִם gershayim, and placed before the last letter of the phrase. It is similar looking to the Latin quotation mark, and is often confused with it even by native speakers, but nonetheless different.

**You might have noticed that ‘historically’, ‘for historical reasons’, etc. are somewhat a trend in this lesson. Hebrew is an incredibly old language, about 5,000 years old in fact, riddled with old tales and tradition. During that period it changed a lot, it even died for 2,000 years and came back to haunt us in the last 150. Despite this, the Hebrew writing system as we know it today was tailored (albeit not perfectly) for Hebrew as it was spoken some 2,500 years ago, and remained relatively unchanged during that whole period. Therefore, there are a lot of peculiarities in the Hebrew alphabet that we simply do not have time to cover, stemming from the complicated history of the language.

There are also a handful of letters which, for historical reasons, are still pronounced the same.

א alef + ע áyin (+ ה he) = ‘ (glottal stop) or none (ה he only as none)

soft ב bet + ו vav = /v/

ח chet + soft כ kaf = /ch/*

ט tet + ת tav = /t/

hard כ kaf + ק qof = /k/*

ס sámekh + שׂ sin = /s/

*I still transcribe hard כ kaf and ק qof, as well as ח chet and soft כ kaf differently (/k/ vs /q/, /ch/ vs /kh/) because, well, it’s easier than the other homophones.

To form a word, simply string together letters - the vowels magically appear in your head!

ספר (séfer) - book

ספר (sapár) - barber, hairdresser

ספר (sipér) - (he) told, (he) cut hair

ספר (supár) - (passive of above verb)

ספר (sper) - spare (English loanword)

…Yeah, that’s easier said than done.

See, in general with the ‘abjad system, all words pronounced with the same consonants are written exactly the same, which can create a heck of a lot of homographs, words written the same but pronounced differently. This problem has been cleverly solved using אִמּוֹת קְרִיאָה - ‘imót kri’á (literally mothers of reading). These are letters in Hebrew that serve a double function as a consonant and a vowel, marked with a 3 on the table. Noticed the letters ו vav and י yod have multiple pronunciations?

In many words, vowels (especially /i/, /o/ and /u/) are marked using one of these letters to reduce the number of homographs. For example, the words listed earlier are usually written:

ספר (séfer) - book

ספר (sapár) - barber, hairdresser

סיפר (sipér) - (he) told, (he) cut hair

סופר (supár) - (passive of above verb)

ספייר (sper) - spare (English loanword)

These letters can be conveniently memorized using the acronym אֶהֶוִ״י ‘eheví.

Interestingly enough, Yiddish, written with the same 22 letters, uses these letters (and some more) to create a full alphabet, where each and every vowel in a word is written, as well as the consonants. But we aren’t learning Yiddish here.

Learning when and where to put ‘imót kri’á comes with time, as it is often up to the reader where to put them. The style of writing I’ll be teaching with is called כְּתִיב חֲסֵר ktiv chasér, or ‘lacking spelling,’ where the bare minimum of ‘imót kri’á are used, and all vowels are indicated using vowel points, נִקּוּד niqúd, explained in the next section. This style is often used in children’s books and Biblical inscriptions; ktiv chasér is historically the only way Hebrew was written. This is in opposition to כְּתִיב מָלֵא ktiv malé, ‘full spelling,’ where ‘imót kri’á are used and vowel points aren’t; this is the style of writing virtually every modern Hebrew text is written in.

This might seem all confusing at this point, but let me assure you it isn’t. Once you wrap your head around it and start reading more and more of the language, you just instinctively know how a word is read off the bat. Context is usually more than enough to settle any ambiguities in how to read a word.

Vowel Points

Vowel points, נִקּוּד niqúd, are the diacritics used in Hebrew to indicate the vowels of a word, to complement the ambiguous ‘abjad system. These are the little dots and lines around each letter in previous examples.

Hebrew has five vowels: /a/ /e/ /i/ /o/ /u/ - pronounced almost identically to those in Spanish and Greek, to name a few. However, it has 13 different vowel points. Historically, and still in some traditional readings of the Bible, each mark had a different pronunciation, but in Modern Hebrew a lot of them merged with one another.

The final form of מ mem, ם, is used as a placeholder here.

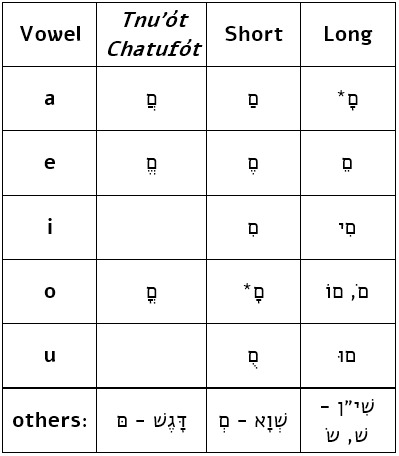

Make no mistake, the two vowels marked with an asterisk are in fact the same vowel. For now, know that in most cases it is pronounces as /a/. The /o/ pronunciation is rare, only in certain templates of words, and distinguishing between them is out of the scope of this lesson. For now, the only common word that uses the /o/ pronunciation is כָּל kol, meaning ‘all’.

Short and long vowels are only traditional nomenclature - in practice, all vowels in each row are pronounced with the same length. תְּנוּעוֹת חֲטוּפוֹת tnu’ót chatufót are stlightly different, but nonetheless pronounced the same. Note that the some long vowels use ‘imót kri’á intrinsically.

דָּגֶשׁ Dagésh:

The point on the bottom left, the דָּגֶשׁ dagésh, is an interesting topic. However, the only relevant point to this lesson is that it distinguishes between hard (with dagesh) and soft (without) pronunciations of בֶּגֶ״ד כֶּפֶ״ת béged kéfet letters.

שְׁוָא Shva:

There are two types of shva: נַע na’ ‘moving’ - indicating an /e/, and נַח nach ‘still’ - indicating no vowel. Distinguishing between them is way out of the scope of this lesson, so for now the only way to tell them apart is through experience and transliterations.

שִׁי״ן Shin Points:

You might have noticed the rogue ש shin at the bottom of the table there. ש shin is different to other letters with double pronunciations, as it had always had two different pronunciations. Therefore, it got a different point to distinguish between the two: a dot on the right spoke of the ש shin indicates the common /sh/ pronunciation - שׁ, and a dot on the left spoke indicates the rarer /s/ pronunciation - שׂ. Each pronunciation is subsequently called שִׁי״ן יְמַנִית shin yemanít ‘right שִׁי״ן’ and שִׁי״ן שְֹמָאלִית shin smalít ‘left שִׁי״ן’.

All word-final letters have no vowel, unless marked otherwise. Most letters cannot even take a vowel mark at the end of a word. Exceptionally, ה he, ח chet, final ך kaf, ע áyin, ת tav, in certain circumstances do take vowel marks. ש shin must always have either a left or a right point, but no other vowel mark.

Practice!

Try reading these basic Hebrew words, then look at the answer key at the end to see if you were right.

1. אֲנִי 2. כֶּלֶב 3. בְּתוֹךְ 4. שֻׁלְחָן 5. פְּרִי 6. כָּל 7. יַם 8. עֵץ 9. אֲדָמָה 10. שְׂמֹאל

Answer Key

‘aní – I (me)

kélev – dog

betókh – inside

shulchán – table

pri – fruit

kol – all

yam – sea

‘ets – tree

‘adamá – ground, earth

smol – left (vs. right)

Alright then, that’s it for today! Follow me for more Hebrew lessons, hopefully they won’t all be as long as this one :D

לְהִתְרַאוֹת בַּפַּעַם הַבָּאָה! (lehitraót bapá’am haba’á)

See you next time!

#hebrew#learn hebrew#study hebrew#hebrew lesson#hebrew lessons#hebrew alphabet#עברית#אלפבית עברי#lessons#basics

743 notes

·

View notes

Text

About the Blog

Hi! My name is Tomer, I’m 18, from Israel. I have a bit too much time on my hands, and recently I’ve gotten into the langblr business, since I’m kind of a massive language nerd.

Therefore, I decided to make my own language teaching blog! When (and if) I start doing this regularly, you should expect Hebrew grammar and vocabulary lessons once a week, give or take. Hopefully once I start gaining followers, I’ll start writing lessons more frequently, but for now I’ll run this on a time-to-time basis.

And… that’s it! Next up, probably in the next couple of hours, a lesson on the Hebrew alphabet and how to read it. Then I want to start a series on verb grammar, then… who knows!

לְהִתְרַאוֹת!

24 notes

·

View notes