Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

Soviet infantry advancing behind T-34 tanks during the Battle of Orel, Russia, early Aug 1943.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Camouflaged German 2 cm Flakvierling 38 anti-aircraft gun mounted atop a SdKfz. 7 half-track vehicle, immediately prior to Battle of Kursk, summer 1943

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kathleen Kennedy whilst working for the American Red Cross in London, 1943. (Photo by Horace Abrahams/Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Children play on the bomb sites and wrecked tanks in Berlin, in the aftermath of the fighting in the city. (Photo by Fred Ramage/Getty Images) 08-1945

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Disabled Polish and Russian survivors stand in front of a tank from the 11th Armored Division, Third U.S. Army, in the Mauthausen concentration camp.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Arnold Bauer Barach

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nazi propaganda showing four disabled men. The original caption reads: "Hereditary illnesses are a heavy burden for the people and the state"

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of G. Howard Tellier

15 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Nazi propaganda composite photograph showing mentally disabled children. The original caption reads: "The National Socialist State in the future will prevent people whose lives are not worth living from being born."

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of G. Howard Tellier

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A German soldier searches a Roma man who is forced to stand with his arms in the air, c. 1940. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Harry Lore

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Roma survivors of Auschwitz camp in Straubing with their horses. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Joseph Eaton

33 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Amon Leopold Goeth (1908-1946), a native of Vienna, joined the Nazi party in 1932 and the SS in 1940. During the war he was sent first to SS headquarters in Lublin and subsequently to Krakow, where he was put in charge of the liquidation of the ghettos and labor camps of Szebnie, Bochnia, Tarnow and Krakow. From February 1943 until September 1944 Goeth held the position of commandant of the Plaszow concentration camp near Krakow. After the war he was extradited to Poland, where he was tried before the Polish Supreme Court. He was sentenced to death and executed in Krakow in 1946.

Amon Goeth delivers a speech to the SS staff in the Plaszow concentration camp.

Amon Goeth rides his horse in the Plaszow concentration camp. Photographer: Raimund Titsch

Amon Goeth stands with his rifle on the balcony of his villa in the Plaszow concentration camp. Photographer: Raimund Titsch

Amon Goeth converses with the wife of an SS staff officer at his villa in the Plaszow concentration camp. Photographer: Raimund Titsch

Majola (Ruth Irene Kalder), the mistress of commandant Amon Goeth, stands on the balcony of his villa in the Plaszow concentration camp with his dog Ralf. Photographer: Raimund Titsch

Amon Goeth relaxes in a lawn chair at his villa in the Plaszow concentration camp with his dog Ralf. Photographer: Raimund Titsch

Commandant Amon Goeth’s dog (Rolf) together with another dog. Arthur Kuhnreich, a Holocaust survivor: “I saw Goeth set his dog on a Jewish prisoner. The dog tore the victim apart. When he did not move anymore, Goeth shot him”.

Amon Goeth with his daughter, 1943. He married Anny Geiger in a civil SS ceremony on 23 October 1938. The couple had three children, Peter, born in 1939, who died of diphtheria at age 7 months, Werner, born in 1940, and a daughter, Ingeborg, born in 1941.

Portrait of Amon Goeth while in Polish custody as an accused war criminal.

Amon Goeth, former commandant of the Plaszow concentration camp, is led away from the courthouse after being sentenced to death.

34 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Minsk Ghetto

Affixed to this barbed wire fence surrounding the Minsk ghetto is a sign stating “Warning: anyone climbing the fence will be shot!”

Entrance to the Minsk Ghetto.

German soldiers parade three young people through Minsk before their execution. The placard reads “we are partisans who shot at German soldiers.”

Jewish partisan leaders from Minsk soon after liberation. From left to right: (first row) B. Chaimowicz, S. Zorin, H. Smoliar; (second row), C. Feigelman, Y. Kraczynsky, and N. Feldman.

Jewish residents of Minsk are forced to move into the ghetto.

Jewish residents of Minsk are rounded up to be forced into the ghetto.

Masha Bruskina, a Jewish Soviet partisan hanged with two other partisans, Krill Trus and Volodya Sherbateyvich. The sign reads: “We are partisans who shot at German soldiers.”

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Wedding Ceremony at Church Hit by Bomb.” The bombing of this beautiful Roman Catholic Church in London did not stop Fusilier Tom Dowling and Miss Martha Coogan being married there today. After the ceremony was over, Father Finn, who performed the ceremony, assisted the bridal couple over the debris to the church exit. Fox. September 14, 1940.

25 notes

·

View notes

Photo

This Is What Europe's Last Major Refugee Crisis Looked Like

“As the current migrant crisis in Europe continues, one particular fact gets repeated over and over: this is the worst such disaster since World War II.

That conflict sent millions of Europeans fleeing the persecution, fighting, and poverty that came with it. The displacement began even before the war did, as the first signs of Nazi aggression pushed German residents and their neighbors—particularly Jews—to seek safety elsewhere. Migration continued throughout the war, as families left burned-out towns, children were sent to safer areas, and the scale of Nazi crimes increased. Even the return of peace saw a surge of refugees, with released prisoners as well as citizens of occupied Axis powers left wandering the continent.” - Time Magazine

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Unpublished Photos Capture the Lifesaving Role of Nurses in World War II

“In early 1942, when LIFE magazine featured the need for nurses as its cover story, that fact was as crystal clear. (Most of the photos above were taken for that story but went unpublished.) In the wake of the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. nurse shortage had been thrown into sharp relief: the Army and Navy together were enlisting 15,000 nurses, the U.S. Public Health Service said it needed 10,000 nurses too and U.S. civilian hospitals were already operating at nurse staffing levels that were 10% short of what they needed. With about 23,000 new nurses graduating from existing training programs each year, the need could not be met fast enough for wartime.

In light of that situation, the Office of Civilian Defense and the Red Cross joined together to call for 100,000 American women — they were all women at the time — to volunteer as unpaid wartime nurses' aides, working under the supervision of registered nurses. By performing duties like feeding patients and taking temperatures, they would thus free up the registered nurses to perform the jobs that required the most training, or to go to war. It was an idea that had come about during World War I, and the U.S. entry into World War II had created a renewed need for their services.” -- Time Magazine

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Russian and American troops dancing together when the official link-up was made between the US 9th Army and the Russians at Cobblesdorf. (Photo by Fred Ramage/Getty Images). 05-1945

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Johanna Altvater, secretary to regional commissar Wilhelm Westerheide in the Nazi occupied Volodymyr-Volynsky region of Ukraine. In spite of her clerical role, Altvater was a willing and direct participant in the genocide of Ukrainian Jews, singling out children in particular. One such instance was witnessed by the father of a child she murdered.

“On September 16th, 1942, Altvater entered the ghetto and approached two Jewish children, a six-year-old and a toddler who lived near the ghetto wall. She beckoned to them, gesturing as if she were going to give them a treat. The toddler came over to her. She lifted the child into her arms and held it so tightly that the child screamed and wriggled. Altvater grabbed the child by the legs, held it upside down, and slammed its head against the ghetto wall as if she were banging the dust out of a small carpet. She threw the lifeless child at the feet of its father, who later testified, ‘Such sadism from a woman I have never seen, I will never forget this.’ There were no other German officials present, the father recalled. Altvater murdered this child on her own.”

Wendy Lower, Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

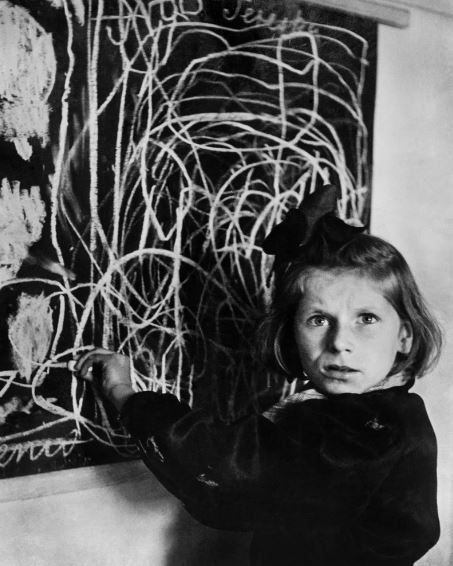

Unraveling a 70-Year-Old Photographic Mystery

“An extraordinary picture taken in 1948 by David ‘Chim’ Seymour, one of Magnum Photos’ co-founders, has since been seen by millions: first, it was published in LIFE magazine where the caption read in part ‘Children’s wounds are not all outward. Those made in the mind by years of sorrow will take years to heal.’ Then it was selected by Edward Steichen for his legendary exhibition The Family of Man. This image of Tereska drawing her home has fascinated many and has become emblematic of World War II.

In the Spring of 1948, when Chim was sent by UNICEF as a special correspondent to report on children in five European countries, 13 million children of Europe had survived World War II. They were homeless and orphans, many of them physically wounded as well as mentally traumatized. As a new retrospective of Chim’s photographs opens in Israel at Tel Aviv’s Beit Hatfutsot Museum, it seems like a perfect time in history to take a new look at Tereska’s picture.

In a school for ‘backward and psychologically upset children,’ as Chim states in his story’s captions, Tereska, then seven or eight years old, is standing in front of a blackboard. As we see in Chim’s contact sheets from a pinned notice on the blackboard, the teachers’ assignment was ‘To jest dom’- ‘This is home’.

That is what children were supposed to draw, but Tereska could only trace in chalk a tangle of frantic lines. Her haunted eyes reflect her confusion and anguish. Tereska’s identity has remained a mystery for almost 70 years.

Teresa Adwentowska came from a Catholic family. She was one of two daughters of Jan Klemens, who was an activist in the Polish Underground State, the Resistance. During the Warsaw uprising (August-October 1944), he was heavily beaten and all his teeth were broken by the Gestapo at their Warsaw headquarters and prison. During the war, Tereska’s mother Franciszka did her best to make ends meet, for instance visiting the Jewish ghetto in order to trade goods.

During the bombing of Warsaw by the German Lutwaffe, Tereska’s home was destroyed, and her grandmother was most likely shot by Ukrainian soldiers who were helping the Germans annihilate the Warsaw Uprising. Tereska was struck by a piece of shrapnel that left her brain-damaged. Fleeing Warsaw after the bombings, four-year old Tereska and her 14-year-old sister Jadwiga spent three weeks trying to reach a village forty miles away from Warsaw – on foot, in a war-ravaged country. They were starving. That episode left her with an insatiable hunger, and her physical and mental condition steadily deteriorated. During the 1954/1955 school year, she had to be sent to a mental asylum in Świecie (about 190 miles from Warsaw). Since her early childhood she had loved drawing, mainly flowers and animals. As a teenager she got addicted to cigarettes and alcohol, and became violent towards her younger brother. Since the mid-sixties, she spent her life at the Tworki Mental Asylum near Warsaw; the only things that meant anything to her were cigarettes, food and her drawings.

In 1978, at the Tworki Mental Asylum, Teresa Adwentowska met with a tragic death: she accidentally choked on a piece of sausage that she had stolen from another patient.

Chim’s photograph of Tereska, which has become a symbol of the fate of children during war and has inspired the Tereska Foundation, remains one of the only portraits of her as a child. As if caught in the tangled web of her own chalk lines, she remained frozen in time: for Tereska, war never ended.” - Time Magazine

8 notes

·

View notes