For the ones who do things a little differently. Support WWYDD on Patreon!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Look, Louts! Lilies! - Yuri For A Hope-Flung Present and Hopeful Future

Look, I’ll be frank. I typically try to keep to a more formal tone when I write for this blog. I’m not in a formal mood. It is June October 2020, and I, like the rest of you, have been under quarantine for a little over three almost seven months now due to the Covid-19 virus. Throw in a eensy, teensy bit of massive political movements and change in response to police violence and racism, and an increase of police violence and racism in response to those movements, and I think it’s fair to say it’s been a tumultuous couple of months. Except, strangely, it also hasn’t been, because so much of this time has been characterized by ennui and isolation. Stressful, yet soul-numbing. In short, it’s been a very weird place to be in.

So, we’ve all found our different ways to cope. My sister’s way has been getting really into succulents(?), and my way has been buying digital manga and video games. I’ve finished stuff I’ve put off for literal years and bought stuff I had heard was good but wasn’t that hyped to get into. And somehow, the one thing I’ve really gotten into has been yuri?

Now, yuri has a very long and rich history, as well as its own sets of conventions and nuances, so it is with a great, great, GREAT deal of respect that I say that I’m going to simplify it for this essay as “Japanese media with a particular focus on romance between women” for brevity’s sake. If you want to know more, there’s actually quite a lot that’s been written about it in English, but I’m aiming this essay at English-speakers who have had at least a little experience with yuri and more than just passing knowledge.

Because you see, I’ve found that yuri fans have a lot of things to say about yuri! And a lot of those things really bug me!! “Yuri is only fetish quasi-porn written by men,” “yuri is only bland wholesome fluff,” “yuri is only high school drama,” so on, so on. It made me mad, but it also made me realize something: a lot of people simply must not know how big this field of lilies truly is! How else can we get people saying “yuri is oversexualized” and “yuri is sexless” as gospel truth? Something’s not adding up here, guys!

So, all that is to say I’m doing something different for this blog: I’m writing up a recommendation list of yuri. A large chunk of it will be stuff I’ve read and can officially give my seal of approval to, while some of them are just titles I’ve heard of that I think will interest others. All of them have been specifically chosen to counter common untrue things I’ve heard about yuri as a whole. I hope you can find at least a few things on this list that you will enjoy and help you keep your head as the encroaching darkness lurches yet a few inches closer!

1. “Yuri is all schoolgirl stuff! Where’s the sci-fi, the period pieces, the action, the fantasy?”

Otherside Picnic

What It Is: A light novel series written by Iori Miyazawa (illustrated by shirakaba). Ongoing, four volumes at time of writing. The story is being adapted into a manga by Eita Mizuno, and an anime adaptation directed by Takuya Satou will be airing in January 2021.

What It’s About: It was on her third trip to the Otherside that Sorawo Kamikoshi almost died, and it was on that same trip she was saved by an angel. Toriko Nishina is a beautiful and confident young woman who also happens to have intimate knowledge of the Otherside, a dangerous yet captivating world that Sorawo can’t help but being drawn to. Toriko convinces Sorawo to join her on her expeditions to the Otherside, fighting off bizarre creatures that have somehow been ripped out of Japanese urban legends and finding strange artifacts in order to make a little extra cash-- all the while keeping an eye out for someone dear to Toriko’s heart.

What I Think: Otherside Picnic is heavily inspired by the novel Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky and features several creatures and scenarios from ghost stories, net lore, and-- there’s no other way to put this-- creepypasta. On paper this sounds deeply unoriginal, so it’s pretty surprising that OP has an incredibly strong identity. The idea of fusing horror with a yuri love story excited me enough the moment I heard about it, so when I finally got to read it for myself, I was delighted to find that the horror elements and the romance elements are both quite strong.

I will say that thanks to the author’s commitment to following his sources of inspiration to the letter sometimes causes him to undercut his own writing (good example: in one arc there’s an ominous train that keeps being mentioned, causing the reader to dread its arrival with each passing page, but seeing what’s on the train will inevitably fall flat in comparison to the reader’s imagination), but those moments are made up by the more original moments-- the things that are left unseen and unexplained.

The place where the story truly shines is the relationship between the two leads. Sorawo and Toriko are great characters, both incredibly charming and deeply flawed, and they achieve a great chemistry with each other right off the bat. Sorawo is a very interesting protagonist, one who turns out to have a deeply tragic past that has made her into a reclusive, somewhat selfish young woman. What’s great is that Toriko, vivacious and confident, everything Sorawo isn’t, accepts this part of her, in a way. Toriko flat out admits she’s not looking for a particularly virtuous person to accompany her, but an “accomplice.” A big part of the appeal of OP is seeing these two “accomplices” bounce off each other, and eventually come to care about each other, all playing against a background of some genuinely spine-crawling horror. Otherside Picnic is a truly underrated series, and I deeply hope that the anime adaption next year will finally get it all the eyes it deserves (menacing phrasing very much intended).

Where To Get It: The light novels are published by J-Novel Club and can be found via various digital platforms and bookstores. The manga will be published by Square Enix Books starting May 2021. The anime will start airing on January 4th, 2021.

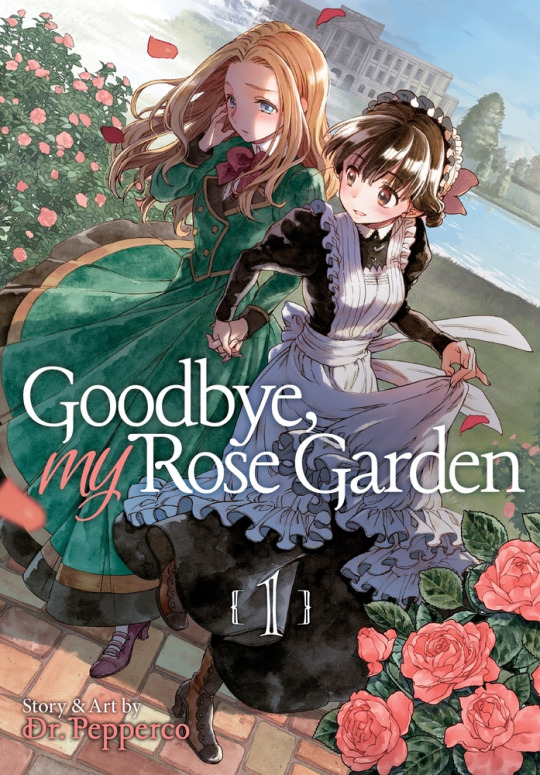

Goodbye My Rose Garden

What It Is: A manga by Dr. Pepperco. Three volumes, complete. It inspired a stage play that ran for a while in Japan, but not much information is available about it in English.

What It’s About: Hanako has two goals: to meet Victor Franks, the mysterious author who pens the books she adores, and to become a writer herself. Despite having the mettle to travel to England on her own to pursue her dreams, she soons finds that it’s difficult for a young, unwed Japanese woman to dream in 20th century London. However, her luck seems to turn around when she meets Alice Douglas, a noblewoman who offers her a job as her maid-- as well as a surprisingly warm friendship. Alice even offers Hanako a way to meet her idol… but at the price of a horrifying request.

What I Think: In the afterword of Volume 1, Dr. Pepperco openly admits that Goodbye, My Rose Garden was the result of them trying to marry all of their favorite tropes (“Victorian maids! Loads of frills! An English family manor!” are some standout items), and this is apparent in the best way possible. GMRG is a lush period piece that will likely appeal to fans of movies like The Handmaiden and Portrait Of A Lady On Fire, with loving attention paid to details like clothes and settings.

The relationship between Alice and Hanako is quite charming, with Alice supporting Hanako as much as she can while still taking every available opportunity to tease her, while Hanako constantly surprises Alice each time she shows her moxie and strength. It’s an adorable, sweet dynamic, yet a dark, melancholy weight lurks in the background in the form of Alice’s request-- in short, it’s a relationship that feels tailor made for me. Still, I believe this “darkness” never threatens to overwhelm the story, only enhance it in such a way that the reader will soldier on, hoping for a happy ending for our two leads. With an engaging plot and gorgeous art, this is a great manga for both longtime yuri fans and newcomers looking for an introduction to the world of yuri.

Where To Get It: Seven Seas Entertainment has translated the first two volumes, with the final one coming to English soon all three volumes into English.

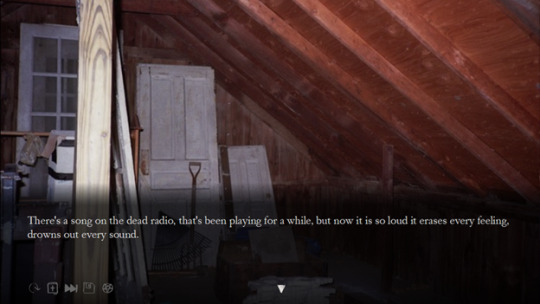

Seabed

What It Is: A visual novel by paleontology, a Japanese doujin circle.

What It’s About: Mizuno Sachiko is a designer who is haunted by visions of Takako, her vivacious childhood friend and former lover. Narasaki Hibiki is a psychiatrist who wants to help Sachiko make sense of these hallucinations. Takako is… confused, trying to figure out why she keeps losing her memory and why she and Sachiko drifted apart despite being so close. Seabed is a story that spans the pasts and presents of these three women as they attempt to find and understand the truth.

What I Think: At first glance, Seabed seems simple, but it’s a bit of a hard story to explain. In a way, there isn’t much to explain-- it’s a very slow, down-to-earth story that gets almost tedious at times. I think it would be a hard sell to someone who isn’t used to visual novels, but I could imagine it being challenging even for fans. All I’ll say is this: if you give Seabed a chance, it will draw you into a surreal, gentle, melancholy tale akin to slowly sinking beneath the water of a strange, yet not unfriendly sea. For its simplicity, it’s got quite a few surprises in its long, long runtime, and any attempt to explain further will just ruin an experience that’s meant to wash over the reader over time. The only thing I’ll say is the one thing I think everyone knows: the climax will make you cry.

Where To Get It: Seabed is published in English through Fruitbat Factory and is available on Steam, Itch.io, and Nintendo Switch.

SHWD

What It Is: A manga by Sono. Ongoing.

What It’s About: Sawada is one of the few women working for the Special Hazardous Waste Disposal, and the only one in her office. But that changes when the stunningly-strong yet staggeringly-sweet Koga is hired, and the two become close in no time. Sawada trains Koga and soon the two go on their first mission to dispose of the “hazardous waste” left after a recent war… the dangerous, organic anti-human weapons known as the Dynamis.

What I Think: SHWD opens with several close-ups of Sawada’s arm muscles as she works out. I have found that page alone is sometimes enough to convince someone to read SHWD, and if not, pictures of Sawada and-- especially-- Koga are often enough to do the job. In all seriousness, what I love about SHWD can be summarized by something Sono said in an interview about the manga:

‘The first motivating force was "I want to write a yuri manga featuring strong women." I was very drawn to strong female characters by watching "PERSON of INTEREST" and "Assassin's Creed Odyssey." However, I felt that I should differentiate myself by doing something other than a "strong woman" and "weak woman" dynamic. So, I thought about coupling women with different types of strength. This is why all of the SHWD main characters are "strong women."’

It’s a mindset I love a lot. Koga is remarkably strong in a physical sense, but her mental fortitude is fragile due to her past experiences with the Dynamis, and as such, it’s Sawada who uses her immense mental strength to support her. Indeed, every character in SHWD so far bears intense trauma born of the Dynamis in some way, and it’s hard to see how their pasts still hurt them in the present. But that just makes it satisfying to see these women come together to support one another. SHWD drew me in with a unique and often dark action-oriented story with horror elements, but it’s this idea of “strong women” who make up for each other’s weaknesses that really makes it dear to me.

Also, it can’t be stated enough that Sono is so so so so so (etc) good at drawing muscular women.

On a completely unrelated note, there’s a side story about Koga and Sawada playing sports together. This includes judo. I am saying this for no reason.

Where To Get It: The English translation of the manga is released in chapters by Lilyka Manga.

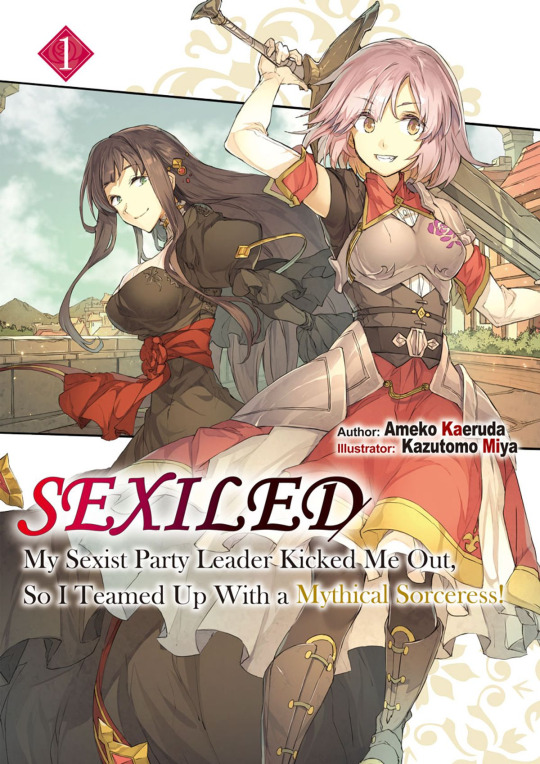

Sexiled: My Sexist Party Leader Kicked Me Out, So I Teamed Up With a Mythical Sorceress!

What It Is: A two volume light novel series by Ameko Kaeruda, illustrated by Kazutomo Miya. Possibly complete.

What It’s About: Tanya Artemiciov is an absurdly talented Mage. So why the hell was she kicked out of her adventuring party? Her leader and former friend sums it up in four words: “You’re a woman, Tanya.” In a fit of rage, Tanya channels her anger into a “venting” session that involves swearing her head of and casting a volley of Explosion spells into the wasteland… and accidentally releases a legendary sorceress! Luckily, Laplace is actually quite nice, and just as powerful as the legends say, so the two decide to team up so Tanya can have her revenge!

What I Think: So, this is a silly one, but after a couple of darker entries I think it’s a good palate cleanser. Sexiled is a loud, not-even-remotely subtle, unabashedly feminist take on the “power fantasy” light novel, especially the “revenge fantasy” subgenre-- and even if that sounds awesome on paper to you (ex. me), it will probably feel over-the-top at times to you (ex. me). But in a way, that’s actually kind of its charm.

I like that Kaeruda utterly refuses to let up on what she wants to tell you, especially because the story was inspired by a real case in Japan. One may be tempted to think “this story is ridiculous, no one would ever be this cartoonishly sexist!” and then you read a news article about how in a famous Japanese medical university was found rigging the test scores of women, and you realize, “oh, people are still this cartoonishly sexist.” So I’m fine with Kaeruda letting it all out in this story. At the same time, I think Sexiled is best when it’s focused not on Tanya’s revenge but on her kindness, and the way her compassion, her strength, and yes, her anger inspires the women and girls around her.

Sexiled is a fun and often very funny romp about assholes getting theirs, with some surprisingly deep and nuanced moments hiding in a very unsubtle story.

Where To Get It: The light novels are published by J-Novel Club and can be found via various digital platforms and bookstores.

BONUS: Other titles with sci-fi/fantasy/action elements that may interest you!

The Blank Of Describer: A one-shot manga by kkzt about a pair of two dream-builders. They’ve taken all kinds of commissions in the past, but one job they recieve throws them for a loop: a request for a shinigami that can predict and report death. And then comes the kicker: the customer asks the two of them to give it features that the both of them “adore the most…” (Published in English by Lilyka Manga)

A Lily Blooms In Another World: A light novel by Ameko Kaeruda (illustrated by Shio Sakura), author of Sexiled, about Miyako, a Japanese wage slave reincarnated into another world based on her favorite otome game. However, she’s not interested in her would-be love interest, but in Fuuka Hamilton-- the game’s villainess! After Miyako confesses her love, Fuuka decides to give her a challenge: if Miyako can make her say the words “I’m happy” in fourteen days, she’ll stay by her side! (Published in English through J-Novel Club, available on various platforms)

Superwomen In Love: An ongoing manga by sometime about the sentai villainess Honey Trap and her infatuation with the masked superheroine Rapid Rabbit. After being kicked out of her evil organization, Honey Trap decides to team up with her former nemesis to fight evil-- and hopefully, find romance! (To be published in English by Seven Seas Entertainment, coming in April 2021)

2. “Yuri is all stories about teenagers! Where’s the stuff about adults?”

Take a look at the previous section: there’s the stuff about adults! Otherside Picnic, Goodbye My Rose Garden, Seabed, SHWD, Sexiled, The Blank of Describer, A Lily Blooms In Another World, and Superwomen In Love are all stories with adult-aged protagonists! But if you’re searching for a more down-to-earth romance, I’m happy to report there’s quite a bit of options to look into!

Still Sick

What It Is: A manga by Akashi. Three volumes, complete.

What It’s About: Makoto Shimizu is an office lady with a secret: she’s a yuri fan who draws doujinshi. She’s able to keep her two lives separate, all until the day she comes face-to-face with her co-worker at a convention! To Makoto’s horror, Akane Maekawa is amused by her nerdy secret, but Akane may have some secrets of her own...

What I Think: This one was a roller coaster for me: I loved the premise of the manga, but wasn’t sure about the dynamic between the leads… that is, until near the end of the first volume, where something happened and everything changed. Without giving too much away, I implore people to give Still Sick a chance-- it has a much deeper story than one might initially guess, as well as an interesting character dynamic between the two leads with some surprising turns.

Where To Get It: The first two volumes of Still Sick are published in English by Tokyopop, with the final one coming soon All three volumes have been published in English by Tokyopop.

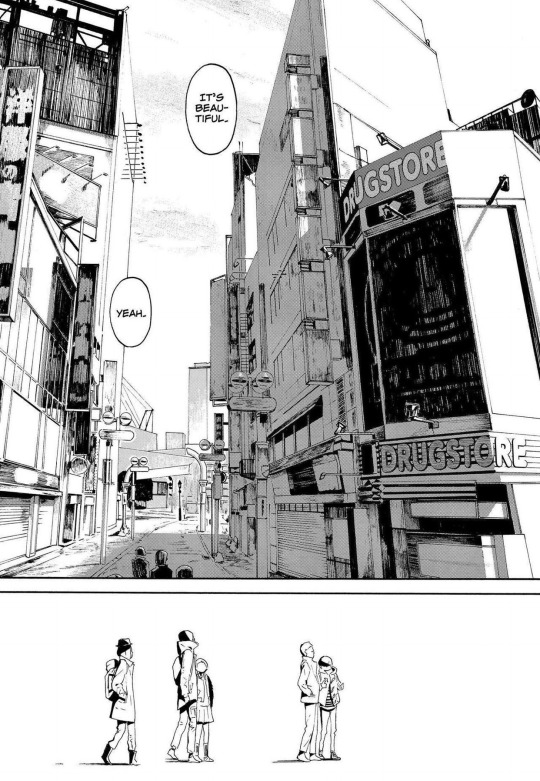

After Hours

What It Is: A manga by Yuhta Nishio. Three volumes, complete.

What It’s About: After being ditched by her friend at a club, Emi Ashiana is ready to write the whole night off. All that changes when she meets Kei, a DJ who seems to be everything Emi is not-- cool, confident… employed.... But Kei and Emi hit it off and Emi’s life changes as Kei draws her into the world of Japan’s club scene!

What I Think: It’s hard to explain exactly why I like this manga, but I reeeeally like this manga.

There’s just something about the sleek art, the amazing atmosphere of the scenes set in nightclubs, the chemistry between Emi and Kei, the focus on more mature topics.... it’s a manga that’s remarkably magnetic for how down-to-earth it is. It’s also just interesting to read stories about subcultures that don’t normally get a spotlight in comics. To sum it up, After Hours is just a lovely manga that’s severely underrated that’s perfect for someone who’s looking for a story that’s both fun and mature.

Where To Get It: All three volumes are published in English by Viz Media.

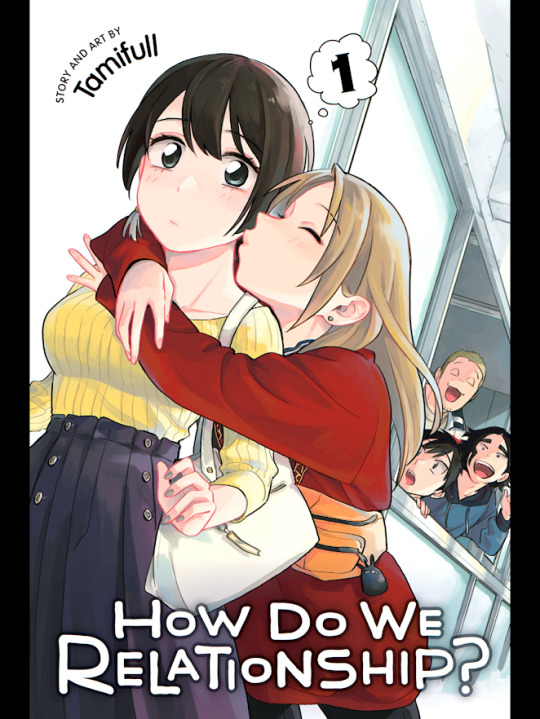

How Do We Relationship?

What It Is: A manga by Tamifull. Ongoing, five volumes at time of writing.

What It’s About: Miwa and Saeko’s first meeting is… interesting. But despite that, and despite their clashing personalities, the two of them become fast friends. Well… actually, perhaps more than friends. You see, pretty soon the two of them learn that the other is into women. With that in mind, Saeko suggests they try dating each other-- might as well, right? “Might as well” seems like a strange place to begin a relationship, but perhaps even something like that could end in true love?

What I Think: “Why do romances always end when they decide to start dating?!” That’s the question Tamifull poses in the afterword of Volume 1. And it’s a great question! What makes How Do We Relationship? an interesting manga is how oddly realistic it is, highlighting things like the compromises people make in relationships, people who get into relationships for pragmatic reasons rather than love, the whole “thing” about sex… as well as highlighting the additional issues queer people have to deal with. That may sound like a heavy story, but it’s actually quite light-hearted, as well as very, very funny at times. With a cute art style and surprisingly deep premise, HDWR is a great manga for older yuri fans who are craving a more mature story.

Where To Get It: The first volume has been published in English by Viz Media, with more on the way.

BONUS: Other titles with adult protagonists that may interest you!

Even Though We’re Adults: A manga by Takako Shimura about two women in their thirties. Ayano and Akari meet each other in a bar and almost immediately feel a sense of chemistry between them. There’s just one problem: Ayano is married to someone else. (To be published in English by Seven Seas Entertainment, coming in January 2021)

Doughnuts Under A Crescent Moon: A manga by Shio Usui. Uno Hinako wants nothing more than to be seen as a normal young woman, but she just can’t seem to make a “normal” romance work. But maybe Sato Asahi, a woman who works at the same company as her, can show her a new kind of normal? (To be published in English by Seven Seas Entertainment, coming in February 2021)

Our Teachers Are Dating: A manga by Pikachi Ohi. Hayama Asuka is a gym teacher, Terano Saki is a biology teacher. One day, they come into work both looking suspiciously happy… because they’ve started dating! (Published in English by Seven Seas Entertainment)

I Married My Best Friend To Shut My Parents Up: A one-volume manga by Kodama Naoko. Morimoto is sick and tired about constantly being badgered about finding a man to marry, so her kouhai from her high school days offers a solution: marry each other to make her parents back off! (Published in English by Seven Seas Entertainment)

Now Loading…!: A one-volume manga by Mikan Uji. Takagi has just snagged her dream job at a games publisher, but being put in charge of a mobile game that’s barely pulling in any attention isn’t exactly what she was hoping for. What’s worse, she’s drawn the attention of her strict higher-up Sakurazuki Kaori… who also happened to design her most favorite game of all time?! (Published in English through Seven Seas Entertainment)

3. “Yuri is all schoolgirl stuff! Where’s- wait, didn’t we already do this one?”

Yes we did. And you know what? I’m making a stand! There’s a lot of really, really good yuri stories set in high schools, and I think more people need to give them a chance! Here are some high school titles that I think are worth a second look for one reason or another!

Bloom Into You

What It Is: A manga by Nakatani Nio. Eight volumes, complete. A twelve episode anime aired in 2018, covering about the first half of the series. A three volume spinoff light novel series written by Hitoma Iruma was also published.

What It’s About: Yuu Koito has long dreamed of the day she’d find That One, Storybook Romance that would make her feel like she was walking on air, but the day that a boy confesses to her, her feet remain firmly planted on the ground. When she meets Touko Nanami, a girl who seems to have the same strange, distant relationship to romance as she does, Yuu feels like she has found a comrade. But what will happen when the next person to confess to Yuu… is Touko?

What I Think: What can I say about Bloom Into You that hasn’t already been said? There’s a reason it’s basically considered a staple of yuri despite being only five years old. The art is beautiful and delicate, the story has a deft mastery of comedy, drama, and romance, and the characters are deeply loveable. Really, the only reason this one is here is to tell you to get to reading this manga (or watching the anime) if you haven’t already. So get to it!

Where To Get It: The entire series-- as well as the spinoff light novel series Regarding Saeki Sayaka-- has been published in English by Seven Seas Entertainment. The anime is currently streaming on HiDive.

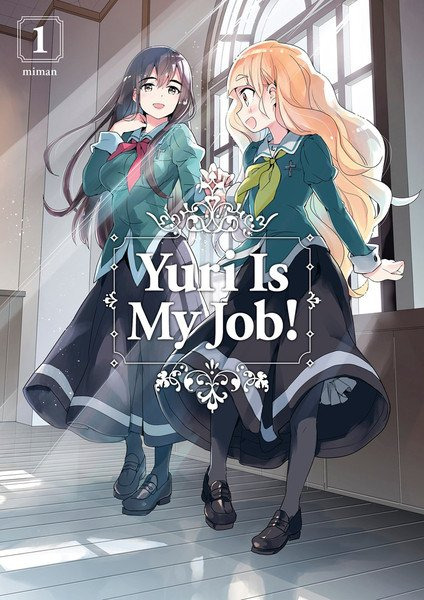

Yuri Is My Job

What It Is: A manga by Miman. Ongoing, seven volumes at time of writing.

What It’s About: Hime wants nothing more than to be adored by everyone and to someday bag a rich husband. Of course, being loved by all takes a lot of work, and she prides herself in keeping her perfect, adorable facade so well-maintained. But of course, the one time she slips up, she ends up injuring the manager of a local cafe! Hime finds herself strong-armed into working for this cafe under their star employee, a kind, graceful girl named Mitsuki. But things aren’t quite so simple-- you see, this cafe has a gimmick in which all the employees are constantly acting out yuri-inspired scenes for the customers, so in a way, the employees also have their own facades. And under her facade, Mitsuki… hates Hime’s guts!

What I Think: Yuri Is My Job is an odd duck, but in a good way. It’s advertised and initially framed as a comedy, but it becomes a surprisingly thoughtful drama about the personas people adopt and why they do so (though, luckily, the comedy never truly goes away). There’s an interesting web of relationships between the girls, and having those interactions take place in a setting where they must act out a completely different sort of drama adds an extra level of drama and intrigue. The cute, polished artwork is just the icing on the cake. YIMJ is a good manga for those who are already familiar with yuri tropes and those who are interested in a drama that doesn’t get too heavy.

Where To Get It: Six volumes have been published in English by Kodansha comics, with the seventh on the way.

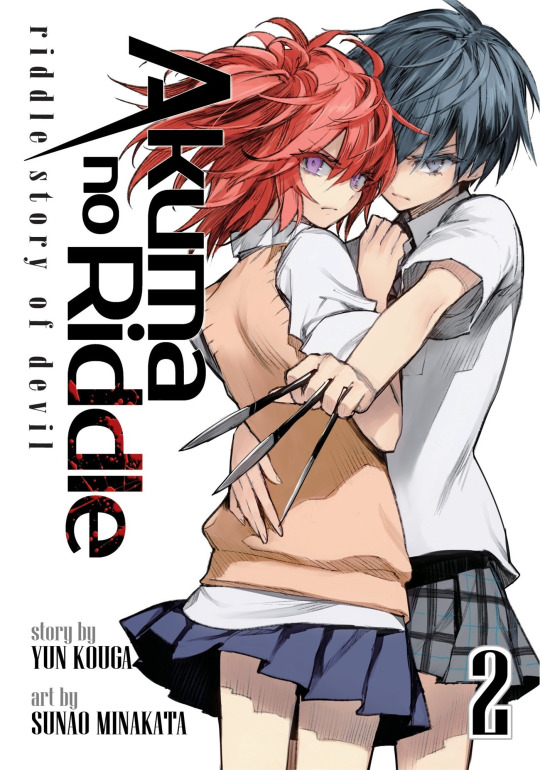

Riddle Story of Devil

What It Is: A manga written by Yun Kouga and illustrated by Sunao Minakata. Five volumes, complete. A 12 episode anime aired in 2014.

What It’s About: At Myojo Private School, an elite all-girl’s academy, Class Black has a secret. Twelve of the thirteen girls are actually assassins who have been offered a dark deal-- one wish will be granted to whoever manages to kill Haru Ichinose, the thirteenth student. But there’s still hope for Haru in the form of Tokaku Azuma, one of the assassins who has decided to defect to Haru’s side-- and defend her from the other girls at any cost.

What I Think: I’m not sure… if I can say Riddle Story of Devil is “good.” It’s definitely something. Although its premise is vaguely similar to Revolutionary Girl Utena, its tone and atmosphere remind me a lot more of the Dangan Ronpa series. It’s schlocky and ridiculous and often over-the-top and at times exploitative. It’s pure junk food, basically… and I believe that’s where the charm comes from. It’s my guiltiest of guilty pleasures. It may not exactly be good, but more often than not, it’s fun. It’s hard not to be immediately interested in a yuri battle series, you have to admit.

And if it does have one undeniably good element, it’s Tokaku and Haru’s relationship. They contrast each other nicely, and while one might expect Haru to be boring and helpless, she’s actually quite proactive at times, and some of the most interesting, engaging parts of the series come from seeing how the two work together to fend off the latest assassin. It’s a short read and if anything, it’s worth it to see how each girl ends up. I recommend it for older viewers who are okay with violence and ludicrous battle scenarios.

Where To Get It: All five volumes are available through Seven Seas Entertainment. The anime can be watched through Funimation.*

*Please don’t watch the anime.**

** At the very least, please don’t watch the anime unless you’ve read the entire manga. Riddle Story Of Devil was one of those unfortunate cases where the anime adaption was produced before the manga reached its conclusion, and as such it has a very strange, rushed ending that includes none of what I enjoyed about the actual ending. Several scenes were also changed, and if I recall correctly, fanservice was added in several places where there was none previously. All in all, I’d really only recommend it for big fans of the series.

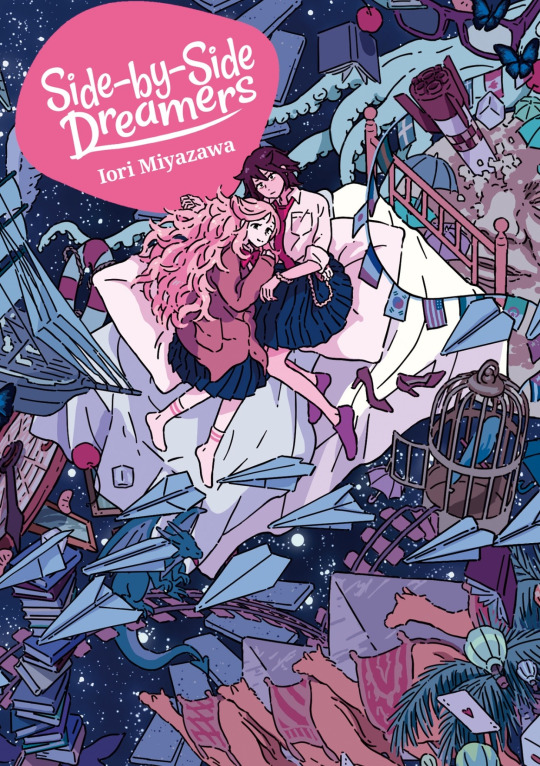

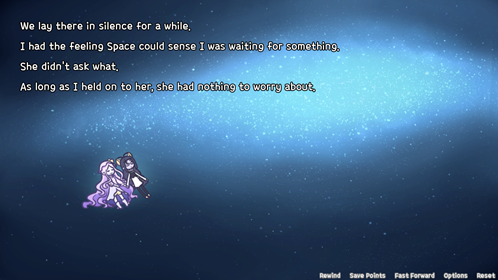

Side By Side Dreamers

What It Is: A light novel by Iori Miyazawa, illustrated by Akane Malbeni. One volume, complete.

What It’s About: Saya Hokage has been suffering from insomnia, but one day finds relief in the form of Hitsuji Konparu, a strange girl who can put people to sleep. As it turns out, Hitsuji is a person who has the special ability to move freely in their dreams, known as a “Sleepwalker.” The Sleepwalkers have been battling beings that possess people through their dreams, and it turns out they want Saya to join them in the fight.

What I Think: Side By Side Dreamers is short and… well, dreamy. I really enjoyed the premise and I think it’s a good novel for people who think Otherside Picnic may be a little too much for them. I also enjoyed each dream sequence-- I tend to find that the writing in light novels is a little dry, so the use of figurative language to describe these scenes was really refreshing and interesting. SBSD is a fun oneshot that I think is especially ideal for newcomers to yuri.

Where To Get It: Side-by-Side Dreamers is published by J-Novel Club and can be found via various digital platforms and bookstores.

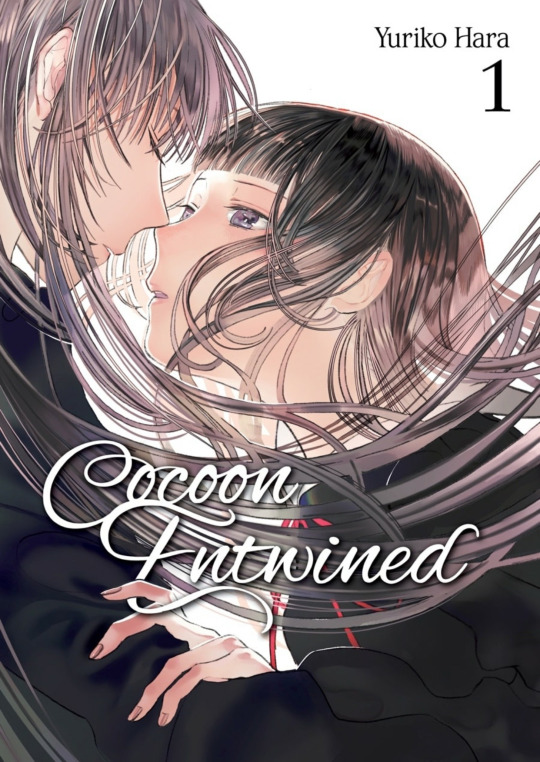

Cocoon Entwined

What It Is: A manga by Yuriko Hara. Three volumes, ongoing.

What It’s About: Hoshimiya Girls' Academy is a strange, almost otherworldly paradise with a peculiar tradition. For all three years, each girl grows out her hair to absurd, breathtaking lengths, in order for it to eventually be cut and weaved into uniforms for future students. Perhaps it is these strange uniforms that seem to whisper about the past that makes the school seem frozen in another time… picturesque, yet stagnant. But one day, a shocking incident shatters the quiet peace of the academy, and the tumultuous feelings that have long been hidden in the hearts of these girls come rushing into the light.

What I Think: Cocoon Entwined is, in a word, eerie. It’s not marketed as a horror story, and I don’t think it’s intended to be one, but I’ve seen some that say they get horror vibes from it. I definitely understand that-- there’s a deep sense of unease that permeates the entire story in a way that’s a bit hard to articulate. The running thread of uniforms made from human hair definitely doesn’t hurt (it does-- I’ve seen many people understandably turned off by this element), but it’s more than that. It’s the sense that everything at Hoshimiya feels frozen and fragile. It’s the sense that everyone is burying their true feelings under countless layers. It’s the fact that in one scene, Saeki reaches out in a dark room full of uniforms and feels her arm touched by countless hands made of hair.

Cocoon Entwined is a strange manga, and I feel it’s not for everyone-- besides the way many are put off by the central premise, the way that the story jumps around in time can be a bit confusing to follow. But in my opinion, I love it for these elements: the uniforms and their marriage between beauty and grotesque, the sense of frozen time, the delicate artwork that feels like it might be shattered by the weight of your gaze, the strange, airless atmosphere, the girls and their clear exhaustion of having to be ideal women. It’s a strange little series that I think should be given a shot, particularly if you want something a little more out there, or a darker take on Class S tropes.

Where To Get It: Yen Press has currently published two volumes in English.

BONUS: Other high school titles that may interest you!

A Tropical Fish Yearns For Snow: A manga by Makoto Hagino. Konatsu Amano has just moved to a new town by the sea, and must deal with her new school’s mandatory club policy. Luckily, she meets Koyuki Honami, an older girl who runs the Aquarium Club. Recognizing her loneliness, Konatsu decides to join her club. (Published in English by Viz Media)

Flowers: A four-part series of visual novels published by Innocent Grey. Flowers focuses on Saint Angraecum Academy, a private high school that prides itself on overseeing the growth of proper young ladies. One notable thing about the academy is the Amitié program, a system that pairs students together in order to foster friendships between the girls. But friendship isn’t the only thing blooming… (Available in English from Steam, J-List, and JAST USA)

Adachi And Shimamura: A series of light novels written by Hitoma Iruma and illustrated by Non that has recently received a manga adaptation and an anime adaption. Adachi and Shimamura are two girls who encounter each other one day while cutting class. Little by little, the two girls become a part of each other’s lives, and feelings begin to form. (The light novels are published in English by Seven Seas Entertainment, the anime is licensed by Funimation)

And there we go! 24 different yuri titles. I didn’t even go into the series that I tried but personally didn’t like that still might interest other people. I primarily made this list to gush about yuri that I liked, but I also tried to include a fairly wide range of things so that, hopefully, any random person who read this whole list could find at least one new title that interests them. And I hope that includes you!

The yuri scene is quite large and wonderful if you know where to look, and it too often gets a bad rap. I hope that this list could give you a new perspective on what kinds of titles are available, and I hope it gives you something new to try. And remember: if you want something specific, try looking for it! There’s a good chance the story you’re craving is already out there, waiting to be discovered!

#otherside picnic#shwd#goodbye my rose garden#sexiled#seabed#a lily blooms in another world#superwomen in love#the blank of describer#even though we're adults#doughnuts under a crescent moon#how do we relationship#still sick#bloom into you#yuri is my job#riddle story of devil#our teachers are dating!#yuri#cocoon entwined#wwydd#side by side dreamers#a tropical fish dreams of snow#now loading...!#i married my best friend to shut my parents up#adachi and shimamura#after hours#flowers#wwydd?

530 notes

·

View notes

Text

Cold Sweats Were Made To Be Broken - How Emily Carroll Creates Effective Horror By Bending The Rules

I believe that, with enough time and resources, someone with a good eye for horror would be able to create a good horror story with just about any medium. With prose, you have the advantage of vivid description and getting to intimately know the character’s inner thoughts and fears, like in the works of Stephen King. With film, you get the advantage of visuals and audio along with the dread that comes with being a helpless audience member, such as the in the works of John Carpenter. And while the poor video game is often given a bad rep among other, older art forms, video games actually are one of the most ideal ways to experience horror stories, since the audience must become an active participant in the story to move it forward, not even allowed the escape of being a passive viewer.

It’s actually for very similar reasons that I find comics to be one of the ideal mediums for the horror genre. You get some of the benefits of prose, some of the visuals of movies, and even a bit of the forced participation of video games, in the fact that readers must choose to advance to each next page- a happy medium, if you will. There’s also one of my favorite features of sequential art as a whole- the fact that the artist has a tight amount of control over the pacing of the story. You can enhance the drop a world-shaking reveal on the reader by devoting a splash page to it, or pull out a scene with agonizing slowness with multiple, decompressed panels- storytelling devices that become lethal weapons in the hands of a good horror writer.

Keeping this in mind, it’s no surprise that horror comics have always been a huge part of comic history. In modern times, American comics are almost always associated with superhero stories, but there’s actually a rich history of horror comics- the rise of gruesome true crime stories and horror anthologies like Tales from the Crypt are why we have the infamous Comics Code, after all. Today we have titles like 30 Days of Night and The Walking Dead (though their more cinematic adaptations are typically more well-known). The huge world of European comics have given birth to a huge number of horror titles, like Italy’s Dylan Dog or Britain’s semi-tongue-in-cheek Scream! And of course, Japan has been the birthplace of great horror comics from the days of Mizuki Shigeru to the advent of modern horror with figures like Junji Ito and Masaaki Nakayama.

But of course, those figures and titles only exist in the world of print comics. In the age of the Internet, it would be remiss to ignore the staggeringly massive world of webcomics in any discussion of comics, let alone horror comics. This is due to any one of the many, many, many webcomics that exist online, but for this essay, I want to focus on an artist who doesn’t just happen to focus on horror comics while publishing them on the internet, but uses and utilizes both the medium of sequential art and the Internet to bring out the best in her comics.

Originally an animation student, Emily Carroll had only just begun to venture into the field of comics when she went hurdling to the attention of the webcomic community in 2010. His Face All Red was only her third comic, and its runaway success (helped by the recommendation of another name in horror comics, Neil Gaiman) was something she admits to be caught off-guard by. But she clearly has seemed to have taken it in stride, considering that her website now hosts almost 20 webcomics, many of them some sort of horror story. She’s also done print comics, including the original anthology Through the Woods and the upcoming graphic novel adaption of Laurie Halse Anderson’s powerful YA story Speak. As grandiose as it may be to say this, I believe Carroll’s style and approach to storytelling was made for the medium of comics, and I believe she deserves a spot up there along with Gaiman and Ito when it comes to naming masters of the horror comic.

But how does she do horror comics so well? It’s not just good writing, or good art, though she’s certainly talented on both those fronts. After spending an amount of time looking through her comics, I think I’ve come up with a solid answer, an answer that can be used to teach anyone interested in comics and in storytelling in general.

Emily Carroll is a master of breaking rules.

When I say rules, I don’t mean that there’s actual rules some God Of Comics has written down somewhere. Rather, the “rule-breaking” Carroll does refers to how she subverts expectations and goes against the conventions of storytelling that have become familiar over time. In doing this, Carroll’s comics have an air of unpredictability to them, and the reader must not only advance through the comic at their own pace, they must do it with the knowledge that the comic will surprise them in some way. In short, when a story breaks “the rules,” it creates the illusion of the audience’s safety being lost.

But how does Carroll break the rules? This is a bit of a nebulous thing to analyze- I mean, I don’t even think “breaking rules” is something Carroll consciously sets out to do. But over time, I’ve noticed recurring themes and storytelling methods in Carroll’s comics, and I think it’s worth analyzing them to gain a better understanding of sequential art and how sequential art can continue to evolve.

Breaking “The Rules” of Each Comic

One thing I like about Carroll’s webcomics is that, since they’re all self-contained short stories, they each have their own unique visual “language.” This can apply to comic’s palette (like how The Hole The Fox Did Make is all grayscale), the format of panels (like how When The Darkness Presses is told through several 4-panel pages), or even the format of the writing (like how The Prince & The Sea is told as a poem). This gives all of Carroll’s comics a sense of cohesion, similar how to repetition is used in visual design to create a sense of rhythm and reason.

But, of course, what’s even more important than the “rules” Carroll establishes for each individual comic, is when Carroll chooses to break these rules.

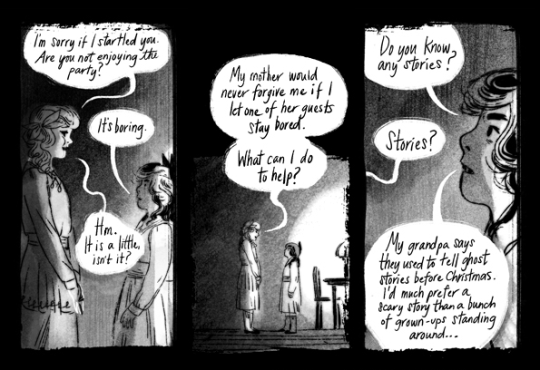

The Hole The Fox Did Make is all grayscale- so when the colorless 4-panel strips are replaced with a mass of panels mostly rendered in an angry red, it comes as a shock. When The Darkness Presses is told through several 4 panel pages- so the reader knows that the long vertical segments that accompany each scene about the door are meant to be considered different than other scenes. And once the reader sees what is behind the door…

Suddenly changing the established visual language of a comic is easy shorthand to let the reader know that the scene is important in some way, but in a horror comic, it can also be a subtle way to catch the reader off-guard. Rebecca’s ghost story in All Along The Wall is told in a simple style and over-saturated colors to distinguish it from the “real” scenes, but the contrast in the story’s bright, colorful palette to the sketchy grayscale of the rest of the comic almost makes it feel more menacing in contrast. The fact that it’s explicitly a ghost story rendered in these almost cheerful hues make it even more uneasy- and ends up saying a lot about the kind of person Rebecca is. In short, it’s good, creative storytelling that also serves to scare.

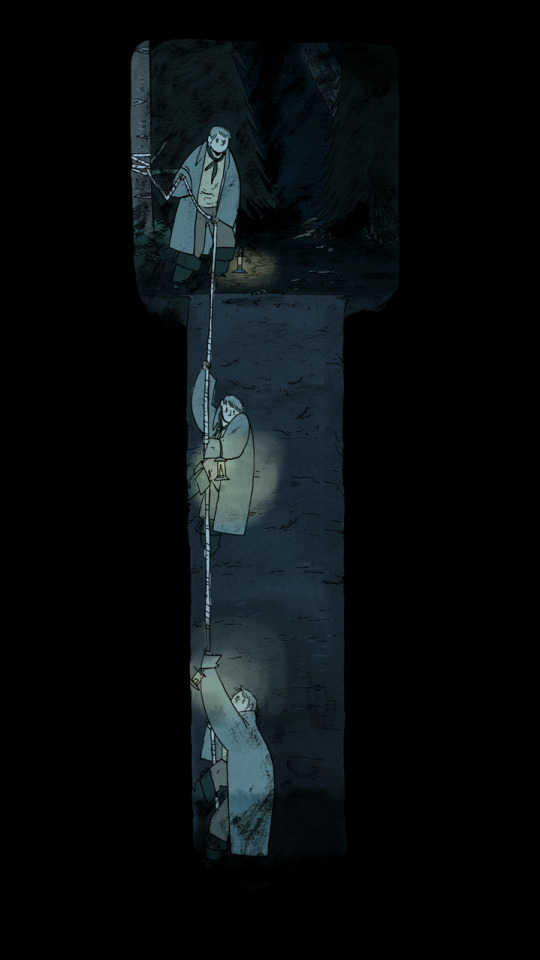

These breaks in the established format work best when combined with one another. The Prince & The Sea takes part mostly on land- specifically, in single-panel illustrations that show only the meeting place of the prince and the mermaid- with a colorful palette that’s equal parts earthy and warm. When the story shifts under the sea, the palette shifts to eerie, cool colors that reflect both the dark atmosphere and the horrifying turn of the plot. But in addition to this, the story finally breaks the single-illustration format, going vertical to simulate the feeling of diving, and adding in “floaty” panels surrounded by black, giving a true feeling of being underwater. Carroll uses not only tone and format shifts but shifts in space- which, incidentally, brings us to one of the most notable and important features of Carroll’s work.

Breaking “The Rules” of Comics As A Whole

In 2000, the comic book artist Scott McCloud published the book Reinventing Comics: How Imagination and Technology Are Revolutionizing an Art Form, in which he made several predictions about the necessary changes that would need to occur in the field of comics in order for the medium to survive, with a major focus on the Internet and webcomics. One interesting idea McCloud proposed was the concept of “the infinite canvas,” the idea that a comic could have limitless storytelling potential thanks to the almost limitless size and space offered by a webpage.

In the year of 2000, the art of the webcomic was in its infancy, consisting mainly of typical comic strips like you’d see in newspapers, leading to a lot of skeptical response to these ideas-- but as it turns out, McCloud was basically completely correct. We’ve seen this from the long vertical formats typical of many Korean webtoons like The Sensual M and Chinese manhua like Tamen de Gushi to the textlogs, flash games, and fully animated segments of the ambitious multimedia-mishmash Homestuck.

Of these examples, however, I think Carroll’s techniques are closest to what McCloud had in mind when he proposed the infinite canvas. His Face All Red famously had the wonderful, wordless sequence of the protagonist descending deep into a hole, depicted by the downward scroll of the reader. When The Darkness Presses switched deftly between standard “real world” pages, long vertical dream sequences, and the dramatic horizontal reveal of what lay behind the door.

To this day, I think Carroll’s most impressive use of the infinite canvas is still Margot’s Room. Initially presented as a month-long event during October 2011, Margot’s Room starts with a grim poem over a grim image, with every important word in the poem relating to a part of the picture, which the reader would click to go to a new part of the story. Each week, a new line of the poem would be revealed alongside a new link, with the last part being released, of course, on Halloween. This creative use of hyperlinks is interesting enough, but the final, shocking scene is almost breathtaking- the events are violent, chaotic, and wild, heightened only by the wide spread of panels over a massive, empty blackness, linked only by words and furious splashes of blood. It’s something that couldn’t really exist in print comics (unless on a much smaller scale) and seeing how effective it is here, it almost make one wonder why it’s not more widespread among webcomic artists.

Without the limits of the printed page, Carroll has a better opportunity to break the typical conventions of sequential art. But she actually goes beyond that, using the medium of the Internet in even more creative ways than McCloud imagined. Besides her use of hyperlinks in Margot’s Room, links are also used to tell the non-linear “story” of Grave of The Lizard Queen, or show two sides to a tragic tale in The Three Snake Leaves. Carroll even employs animation in her work, to an extent. An animated GIF in Out Of Skin conveys the horror of seeing something terrible just out of the corner of your eye, and a certain “trick” panel in All Along The Wall may make you jump out of your skin if you don’t know what exactly it’s going to do. And that’s how it’s brilliant- comic panels aren’t supposed to change, after all. Carroll knows that, and knows just how to use the reader’s unconscious knowledge of the rule of well of course comic panels are always static against them. You don’t think twice about it... until the rule is broken.

Breaking “The Rules” of Storytelling

One of my favorite examples of Carroll’s unique take on the infinite canvas is in When The Darkness Presses. Despite being a short comic released all in one go, it’s presented as a recently completed longform webcomic, complete with animated ad banners. I don’t want to spoil what becomes of these ads later, but it’s very interesting to point out that one of them is for “Alo-Glo,” the skin product that features heavily in Some Other Animal’s Meat. This is especially interesting once you realize that Some Other Animal’s Meat is technically a sequel to When The Darkness Presses.

I say “technically,” because it’s actually entirely possible to read both comics and not know this, the way I first did. They’re two different self-contained stories that just happen to involve two characters at two points at their life.

There’s no real meaning to it- and in a way, this is perhaps Carroll’s favorite rule to break: the all-encompassing question of what does it all mean?

Ever since His Face All Red, Carroll has faced this question, or at least variants of it. How did the man’s brother come back? What was that thing in the hole? In a 2014 interview with Hazlitt, Carroll admits to feeling self-doubt when readers began clamoring for concrete answers:

“People were saying, ‘What’s the meaning of this? What’s the meaning of this?’ and … I felt very much like, I need to justify this somehow, otherwise they will see that I am a faker that has faked my way into some kind of Internet buzz, so there has to be a one-to-one meaning for everything.”

Thankfully, Carroll has been able to move past this initial doubt- I believe, very much for the better. Leaving unanswered questions is almost a trademark of Carroll’s now- from the tree in Out of Skin to the “mystery man” in The Groom to the door in When The Darkness Presses. The thing that plagues the main character of Some Other Animal’s Meat. The voice that calls Regan to the river in The Hole The Fox Did Make. The list goes on.

And it’s not just monsters. From early on in my love of Carroll’s works, I began to notice connecting threads through many of her comics. What did it mean that His Face All Red draws attention to “a tree with leaves that looked like ladies’ hands” (similar to the tree in Out Of Skin) and “a stream that sounded like dogs growling” (a sentence almost identical to how the stream in Margot’s Room is described)? What did it mean that The Hole The Fox Did Make and The Groom featured Regan, or that All Along The Wall is technically a prequel to a comic from Through The Woods? What did it mean that events of When The Darkness Presses are brought up by the main characters years later in Some Other Animal’s Meat?

The answer, of course, is that there is no answer- other than the answers and ideas that begin to form in our heads when we’re presented with an unsolved mystery. Ever since early humans looked up at the stars and put together shapes in the gaps, the nature instinct of human beings drives us to pick patterns out of randomness. Our brains try to find meanings or answers where there is none, whether we want to or not, or even if we are aware of our minds doing so or not. And of course, this almost whimsical trait of ours is also one of our most massive burdens- the horror of imagination. The infinite possibility of the conclusions each person reaches on their own will always be far, far more frightening than any single answer a writer can give.

In a way, Carroll’s most mundane “broken rule” may be her most powerful tool. In the age of endless theories and fiction analysis, in the light of humanity’s eternal, inescapable desire for the solutions for every puzzle, Carroll’s works are unanswerable. And because of this, I think the unexplained monsters of Carroll’s works are some of the scariest in fiction.

Funnily enough, despite basing this essay around the concept of breaking rules, I stated early on that I don’t think Carroll herself sees her approaches to sequential art like that. While researching for this essay, I came across an interview by The Comics Journal with Carroll from 2011, not too far after the runaway success of His Face All Red. It’s a great interview, but what probably stuck with me most is Carroll’s description of how she approaches comics:

“It stems more from just what I think will be most fun, really. And since—when I started doing comics—I’d never done comics for print, I wasn’t in the mindset of doing pages anyway, which maybe led to me not really adhering to that standard when I started in on my own attempts. I like the idea of scrolling just because it’s fun to play around with revealing images that way, but you can play around with the same thing using page turns too really.”

I wanted this essay to be a tribute to one of my favorite artists, but I also initially intended it to be a way to encourage artists to shake up typical comic conventions and try to create unique art. Upon reading this quote, however, I realized that I had one more thing to learn from Carroll, one thing I want artists to know as well. Carroll has carved out her own, unique approach to sequential art, and in the process has happened to buck several storytelling conventions. You too can learn from this and know that you have the freedom to break these same rules- but perhaps the most important thing to take away from this is that Carroll does this because she has fun doing this. Carroll’s comics work not just because they break the rules, but also because she enjoys creating them.

Your own unique style should be what is most enjoyable for you. Creating new and unique artwork is all well and good, but what will make or break your art are the feelings you have while creating it.

And if you have fun in breaking rules, then more power to you.

All of Emily Carroll’s online works can be found on her personal site (general NSFW warning for nudity and disturbing content). You can buy Carroll’s anthology Through The Woods here.

262 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Is The Shape Of Your Monster? – Get Out and Thought-out Horror

Get out.

No, I’m dead serious. If you haven’t already seen Jordan Peele’s Get Out yet, I need you to do me a massive favor. I need you to bookmark this page, close this page, and absolutely do not read this page— or any other essay or article on Get Out— until you’ve finished watching it.

I’m not just saying this because this essay will contain major spoilers for a movie that is best enjoyed going in knowing as little as possible— I mean, yes, it will— but most of all I just want as many people to see this movie as possible. It is by far the most socially relevant American movie to come out this year, at time of writing, if not one of the most socially relevant pieces of American art of the past decade.

It’s also just a very good movie.

(SPOILERS START NOW)

If there was really any complaint I had about Get Out, it would be that the trailers gave a little too much away. If you’ve seen even one you’ve basically got a pretty decent Wikipedia summary of the first two-thirds of the story. Chris Washington, a young photographer, goes on a weekend get-away with Rose Armitage, his girlfriend of four months, to meet her parents for the first time. It’s a pretty big step in any relationship, but Chris has an extra level of anxiety: Rose is white, he’s black, and apparently she’s forgotten to mention that to her family. Despite Rose’s reassurances, her family is awkward, if well-meaning, whenever the topic of Chris’s race comes up— but as the weekend goes on, Chris begins to pick up traces of something more sinister about the Armitages and their entourage of cultured friends.

The trailers establish that, no, Chris is not just paranoid, something terribly wrong is going on here, and (perhaps unfortunately) a lot of the most terrifying scenes are featured prominently in the movie’s marketing— the lingering, uncomfortable shot of Georgina’s tight smile as she weeps uncontrollably, for example, and of course, the almost-sure-to-soon-be-iconic “sink into the floor” scene. During my first watch of the movie I was surprised to see that it’s established very early on that Rose’s mom, Missy, is a psychiatrist who uses hypnosis as a treatment, so I felt a little less irritated at the trailers seemingly spoiling the use of hypnosis as a part of the story.

But here’s the thing— it WASN’T a spoiler. Hypnosis is a part of the plot, but the way it’s presented made me (as well as Chris’s friend Rodney) initially assume that the Armitages were hypnotizing black people into becoming slaves— and amazingly enough, the truth is actually far more horrifying.

I don’t think this was an accident.

You see, what makes Get Out good (and different!) is that it flips several conventions of horror films. The horror genre as a whole is usually based around a fear of “the other,” be it monstrous or metaphorical, but Chris, as a black man among white people, is actually the true Other, and the movie examines how terrifying it truly is to be “Othered.” Rose, the likable, charming, seemingly pure and innocent (white) ingenue who might be the coveted Final Girl of another horror film turns out to be the coldest, most manipulative, and by far the most vicious member of the Armitage family. And Rod already would be an anomaly in most horror movies simply by virtue of actually going to authorities and loudly questioning (alongside the audience) the shady things happening around Chris. But Get Out takes his character a step further, because Rod— portly, goofy, a little on the uncouth side— would almost certainly be on the Killed-Off-Comedy-Relief block in most other movies. Instead, it was the sight of him stepping out of a car that signaled to viewers that Chris was finally saved. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a theater of moviegoers as happy as the one I sat in when Get Out turned the Funny Friend character into the hero of the movie.

This is why I believe the marketing of Get Out was intentionally leading the audience towards the ��hypnotism” angle: because Get Out is a seriously well-thought out movie. I can’t describe it any other way— it’s smart. Not simply in the sense of the very relevant themes it covers, but in how it works as a horror movie. Here where I’m going to ask you to do a second thing— whenever you can, go see Get Out a second time (third and fourth and so on, that’s up to you), and see how many things either foreshadow later events or hold important double meanings. I was very surprised to learn this was Jordan Peele’s very first foray into the horror genre (his typical genre of choice is actually comedy) because he’s slipped into the role of “horror writer” like he was made for it. Apparently Peele is at least a little confident in himself as well, because he’s mentioned in at least one interview now that he would like to direct several other films fitting in the “social horror” genre of Get Out, and I know I for one will be eager to see more from him.

Speaking of the idea of “social horror,” you really can’t talk about Get Out without the politics behind it. All art is, by nature, political in some way, but Get Out really gets into it, pulling double shifts as psychological horror and biting social satire. Get Out is a movie about race, but specifically about being a black person in modern America (specifically-specifically, about being a black man in modern America).

As such, as much as I found myself nodding sympathetically at some of the awkward party scenes and finding some of the lines of Rose’s parents familiar (recognizing those words on notable ‘woke’ white lips), I rather not write about what Get Out says about how it’s like being black in this country. I’m not white, but I’m not black either (Venezuelan-Cuban, if you’re curious), and Get Out is a movie very specifically and firmly about black people. I much rather leave that part of the discussion to black writers— this piece by Robert Jones Jr and Law Ware is a good place to start— and I encourage other non-black writers to do the same.

Instead, I’d like to talk more about something Get Out does differently that can apply to all stories, regardless of politics, genre, or medium. Specifically, I want to discuss the way Peele writes his antagonists.

Lanre Bakare wrote a very good essay about his thoughts on Get Out, and I definitely recommend it alongside the Jones/Ware piece. In particular, this section jumped out to me:

“The villains here aren’t southern rednecks or neo-Nazi skinheads, or the so-called “alt-right”. They’re middle-class white liberals. The kind of people who read this website. The kind of people who shop at Trader Joe’s, donate to the ACLU and would have voted for Obama a third time if they could. Good people. Nice people. Your parents, probably. The thing Get Out does so well – and the thing that will rankle with some viewers – is to show how, however unintentionally, these same people can make life so hard and uncomfortable for black people. It exposes a liberal ignorance and hubris that has been allowed to fester. It’s an attitude, an arrogance which in the film leads to a horrific final solution, but in reality leads to a complacency that is just as dangerous.”

I’ve bolded the most relevant parts for emphasis. I can’t remember who said it (there’s probably several mis-attributed sources) but there’s a quote somewhere out there about how the best villains don’t realize they’re villains.

There’s a very small but telling detail in one scene, in which Rose’s brother, Jeremy, plucks at a small guitar while eyeing Chris. It’s a pretty clear nod to the famous banjo scene in Deliverance, which may seem odd at first. Rose’s family is as far as you can get from the crass, degenerate rednecks who terrorize that movie’s protagonists. But that’s it exactly. The Armitages and their friends are cultured, intelligent, even funny and charming at times—and yet they’re all still doing something that’s utterly, completely, uncompromisingly terrible, because they don’t see it as terrible at all. In fact, they most likely believe what they’re doing is actually good—what could be evil about extending the life of loved ones, or allowing friends to “trade up” physically? There’s actually a twisted implication that they believe they might be doing a favor for their victims, giving them a “superior mind” to control their “superior genes.”

This is where I would like to bring up one aspect of the movie that, as of time of writing, has had very little attention, despite the massive role it plays in the themes of Get Out. The video in which the above photo comes from seems to be the only Get Out interview specifically focusing on Stephen Root and his character, Jim Hudson. It makes sense—from what I can tell, Hudson doesn’t actually show up in any of the movie’s marketing, and he only appears in three scenes. Still, I think he might the best written character in the entire movie, as well as an example to hold up for any writers who want to create believable and terrifying antagonists.

After a series of uncomfortable, cringe-inducing scenes of the Armitages’ party guests, Chris meets Jim Hudson, a blind art dealer who surprises him by saying that he knows his work. Jim is the lone person at the party who doesn’t say something belittling, insensitive, or overly familiar to Chris. He openly scoffs at the ignorance of the other guests and connects to Chris with something personal and important to him. In short, he’s the only person who really treats Chris as an equal—really, as a human.

So of course, it’s all the more shocking when it’s revealed that he’s the winner of the auction.

Hudson’s final scene is when he speaks to Chris in the basement. He’s casually cheery as he explains everything, seemingly unperturbed by the horrible fate he’s about to sentence Chris to. It’s almost comical that the one thing that seems to really trouble him is Chris’s obvious question: “why black people?” Mind you, he’s not troubled because of guilt— he seems to be worried that Chris thinks he’s a racist.

“Honestly though, personally..? I couldn’t give two shits about race. I don’t care if you’re black, brown, green, purple... whatever. What I want is so much deeper: Your eye, man.”

Here’s the thing: out of all the guests bidding on Chris’s body, I believe that Hudson legitimately is the only one who doesn’t give a rat’s ass about race, as far as he thinks. As Chris finally pieces everything together, he flashes back to the party, and suddenly all the seemingly well-intended-if-insensitive interactions betray the true intentions of the guests— a chance to regain glory days for an aging former golf player, a life of better opportunities for a Japanese man, a revitalized young body for the old and sickly husband of a gold digger interested in “the rumors” about black men— all of them are interested in the “benefits” of being black. Jim’s biggest motivation for the procedure is being able to see again, and from what I know there’s no stereotype of one race having better eyesight than any other. I highly doubt he’d care about taking the body of a white person, or any other person. I truly do believe the movie is positing that he’s being honest.

The movie also posits, of course, that doesn’t absolve him at all. Jim treats Chris kindly and respectfully, he doesn’t make any of the gaffs his acquaintances do, he doesn’t believe any of those ludicrous misconceptions about the bodies of black men— and yet, he has no qualms about benefiting from their exploitation. Of course, he’s not racist, he’s just willing to look the other way of black people being violated and dehumanized if it means he can get ahead.

I stay away from most things that self-advertise as “satire,” mostly unintentionally but also because there’s few things that are as painful to watch as bad satire. Luckily, Get Out is extremely good satire, just painful in a different way. I don’t think I’ve ever really gotten what people meant by “biting satire” until watching this movie. It really burrows to the heart of this kind of thinking, and this type of person. It’s brilliant from a standpoint of social commentary, as well as serving as example of how to approach writing a believable, fleshed out antagonist.

And now, I’ll ask you do one final thing. Convince as many people as you can to see Get Out. Blog about it, tweet about it, talk about it— to friends, to family, and especially to people who don’t especially like horror movies or “political” movies. Get Out is a testament to how powerful and provoking horror can be when approached thoughtfully, and it’s bringing up discussions of topics that have never been more relevant to this country. This is the kind of movie I crave to see more of, and I can only hope Peele’s success will allow him to make more of the same while inspiring other creatives to explore what their art can comment on.

Now, go on. Get out of here.

Get Out is now playing on at theaters nationwide.

849 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hearts Of Gold – A Very Brief Look at the Character Design of Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure

If I were to describe Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure in a single word, I think it would have to be “audacious.”

I would be very surprised if there’s anyone out there that doesn’t have even an inkling of an idea of what Jojo is about, but to put it as briefly as possible: Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure is a long-running manga (that has since given birth to a multi-media franchise, including animation, video games, and an exhibit in the Louvre) that tells the story of the Joestar family, spanning years, generations, and various casts of characters. The foes that the Joestars face range from vampires to superhuman immortals to everyday human beings empowered by the ghostly avatars of their resolve and desire. The Joestars and their allies use their own ghostly avatars (most commonly known as Stands), along with other forces such as the manipulation of energy via proper breathing or the weaponization of the Golden Ratio. Oh, and later in the story alternate universes come into play.

I’ve joked in the past that the secret to Jojo’s success is that the mangaka, Araki Hirohiko, simply does whatever he wants. Emotions are rarely anything less than bombastic, characters pose like abstract art pieces, Stand abilities range a seemingly endless range of possibilities, and are named after popular Western musicians and songs, and can be found in infants, turtles, hawks, haunted cat-plant hybrids, intelligent colonies of plankton, and trees. Basically, Araki never seems to ask himself “is this TOO ridiculous?” Honestly, in my opinion, at times it can be— but most of Jojo’s appeal is in how fantastic and delightfully bonkers it can get. If there’s anything Araki does differently, it’s that he is unafraid to let loose, which has made Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure the pop culture sensation it is today.

And if there’s anything Araki is good at letting loose about, it’s character design. Araki (who has gone on the record confirming the importance of the fashion world as an influence for his work) has a knack for designing outfits that are absurd and iconic and outlandish and stunning all at the same time— and in the world of Jojo, a character’s wardrobe is always a key part of their design. Iconic hairstyles, accessories, and tattoos are plentiful. And I could write an entire essay about the otherworldly and delightfully bizarre Stands alone.

I’ve come to find I have a deep love for character design and the thought that artists put into them— so much so that I’m actually in the middle of writing another essay about the character design for another series, Yowamushi Pedal. But as a sort of “appetizer” for that essay (and a “warm-up” to get me back into proper writing form for this blog), I’ve decided to write a small essay on what’s probably my favorite example of character design from this series while also examining what makes it so good.

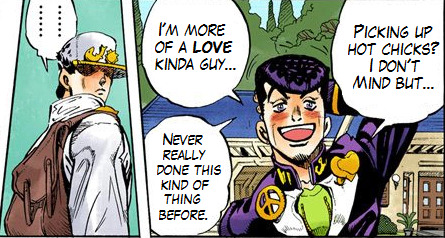

Higashikata Josuke is the protagonist of Diamond is Unbreakable, the fourth major part of Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure, and (at the time of writing) the part that has most recently been adapted into an animated series. Unlike previous Jojo installments, DIU has a specific and consistent setting: Morioh, an average and unassuming Japanese town whose only real oddity is the disturbingly high amount of missing person cases. This, of course, ends up being linked to the power of Stands, and Josuke and his companions take it upon themselves to solve the mysteries of their beloved hometown and bring the unknown killer to justice.

Despite a few vices typical of your average teenage boy and a shockingly explosive (and specific) temper, Josuke’s defining character trait is his kind and noble heart. His major goal of the series is to keep his hometown safe from malevolent Stand users, but he actually ends up befriending many of the enemies he and his companions defeat.

What does all of this have to do with character design? Simple: Josuke’s design effectively communicates almost all of this information.

We’ve already established Araki has an eye for fashion, and even working with a typical high school uniform he’s able to create a look that’s all at once stylish, grounded (at least, for Jojo) and instantly recognizable. But the main thing I want to talk about here is the repetition in Josuke’s design. Repetition is one of the principles of visual design, and the idea is simple: repeating a visual element in your design will create a sense of unity and cohesiveness. This is mostly applied to things like graphic design, but I find repetition is a great way to create excellent character design as well.

Have you guessed what the repeated element in Josuke’s design is? That’s right: he wears his heart on his sleeve.

Or, rather his collar. Josuke customizes his school uniform with pins, and three of those five pins are heart. Most notable is the larger one he wears on his open jacket flap, opposite a large peace sign. One could definitely say that “love and peace” is Josuke’s ultimate goal in bringing the killer of Morioh to justice.

Speaking of the flaps of his jacket, take a close look. While it’s not as obvious as the stylized pins, the shape of Josuke’s open jacket creates what’s unmistakably a heart shape. Even Josuke’s silhouette calls to mind a heart: compare the width of his shoulders and chest to his waist.

Of course, we can’t talk about Josuke without talking about his hair. Josuke’s hairstyle is great, not just because it’s snazzy (it is) but also because it’s a rare QUADRUPLE-hitter of character design. First, obviously, is the fact that it continues the heart motif (only at certain angles— it’s even more pronounced in the anime). More important than that though is the fact that it’s instantly distinctive and even iconic, setting him apart not only from his fellow “Jojos” but from other characters in Japanese pop culture as well. Even if you only saw him in silhouette, you could probably identify Josuke by the shape of his hair alone.

Perhaps most cleverly of all, though, is how it sets up a contrast that serves to communicate Josuke’s character depth. See, in Japan, particularly in Japanese media and pop culture, pompadours are typically shorthand for a delinquent. When the audience first meets Josuke, more likely than not they’d assume he’s a bit of a rough kid (especially since the previous “Jojo” was a delinquent himself), leading them to be surprised when his introduction scene sees him attempting to be friendly with a local turtle to get over his fear of reptiles.

It’s a classic set up and reversal: “the delinquent with a heart of gold.” Nowadays it’s starting to become a bit of a cliché, but at least it’s a starting point for character depth. But Araki gives this trope another twist: in Josuke’s introduction (and establishing character moment), Josuke encounters some of his upperclassmen. They talk down to him, harass him, and even hurt the poor turtle, but Josuke, being a freshman, is of course too polite to talk back to his senpai.

And then one insults his hairstyle.

Instantly Josuke’s entire demeanor changes. One broken nose later, the upperclassmen are running for their lives, the turtle’s shell is mysteriously fixed, and the audience is beginning to get it. Josuke is a nice guy, he has a set of morals he sticks to, but he’s not a pushover, and he’s definitely not opposed to violence. In short, he’s far more than just a high school punk.

As for why Josuke’s hairstyle is such a big deal to him, that’s the last important detail about it: it ties into Josuke’s history, and therefore, his motives. As it turns out, Josuke’s hairstyle is modeled after that of a mysterious stranger that helped him and his mother many years ago. Inspired by the man who saved his life, Josuke decided to live his life as he believed his savior would, which reflects in his compassionate nature at the time of DIU— wouldn’t you know it, linking neatly back to the heart shape, specifically as a symbol of love.

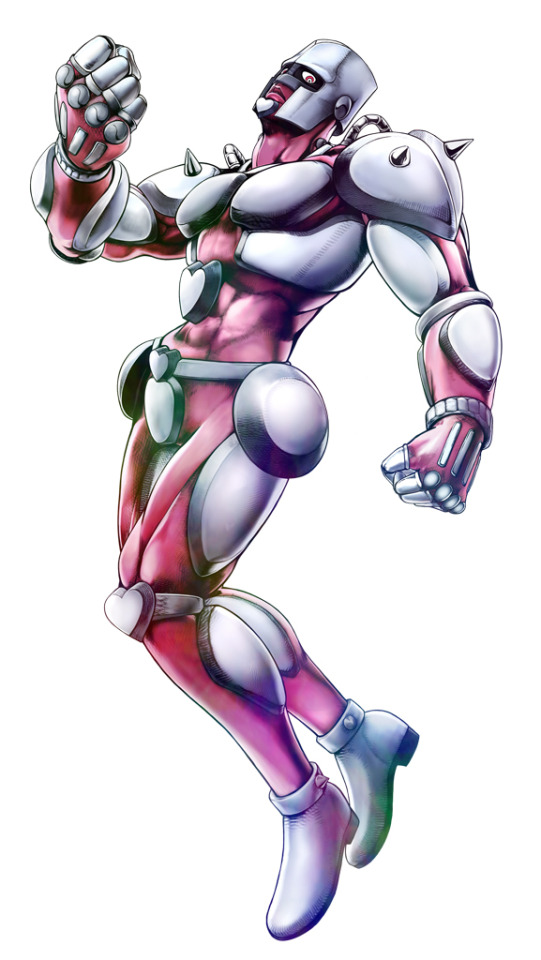

It’s things like this that make me wonder is Araki is a genius, or simply ridiculous.

Anyways, the short and long of it is that’s Josuke’s pompadour continues the heart theme. That theme also just so happens to continue in his Stand, Crazy Diamond. There’s hearts all over Crazy Diamond’s design, some blatant, some more subtle (hint: look at its shoulders). And of course, its helmet-like head is an obvious parallel to Josuke’s hair while also incorporating a heart-like shape. As an extension of Josuke, it’d only make sense for Crazy Diamond to also possess his motif.

But what does the motif mean? Well, I probably don’t have to tell you. Even if you somehow didn’t know that hearts are visual shorthand for love and affection, the round edges might clue you onto the fact that it’s a “soft” shape, similar to how a circle carries connotations of approachability. Hearts are love, kindness, compassion— all that warm and fuzzy stuff. Basically, Josuke’s “hearts” are all meant to clue the audience to the fact that he’s a good kid.

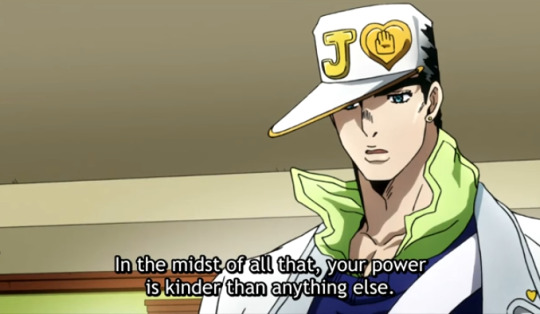

This is reflected in the main ability of Crazy Diamond. On paper, Crazy Diamond’s ability is “restoration,” allowing Josuke to return anything to a previous state. The most common application he uses this ability for, however, is healing the wounds of others. As Jotaro says early in the story, while humans are naturally drawn to violence and destruction, Josuke’s strength is rooted in his compassion. It’s his compassion that leads to him befriending his many allies over the course of DIU, even those who started as his enemies. And ultimately, it is the culmination of all these different bonds that lead to the defeat of Morioh’s killer.

Diamond is Unbreakable is often referred to by fans as something of a “slice-of-life” series. While there’s plenty of action and drama, this classification isn’t entirely inaccurate, what with the small town setting and the fact that most of the cast are high-schoolers and otherwise average people, despite all the punch ghosts. Even with all the fights and mysteries, DIU is more of a story of characters, of their strengths, weaknesses, inner conflicts and interactions. It’s a “softer” chapter in the story of Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure, and Josuke, with all his “softness,” is the perfect protagonist for it.

In talking about Josuke’s character design, I actually ended up talking a lot about a lot of other things, including Josuke as a character and the themes of Diamond is Unbreakable— and that’s precisely why Josuke’s character design is so fantastic. You see, aesthetics are great, but a character’s design should ultimately tell me about the character, and if it also happens to communicate some central themes of the story, well, the more the merrier. Josuke’s character design is one of my favorite Jojo designs, and stands as a testament to the power of a few repeated elements as well as what a good character design can communicate.

Araki Hirohiko, your manga is ridiculous, but it’s a damn good kind of ridiculous. Shine on, you crazy diamond.

Diamond Is Unbreakable can be watched with subtitles on Crunchyroll, along with all the previous seasons of David Production’s current adaption of Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure.

#jojo's bizarre adventure#jjba#diamond is unbreakable#josuke higashikata#wwydd?#manga#anime#character design

394 notes

·

View notes

Text

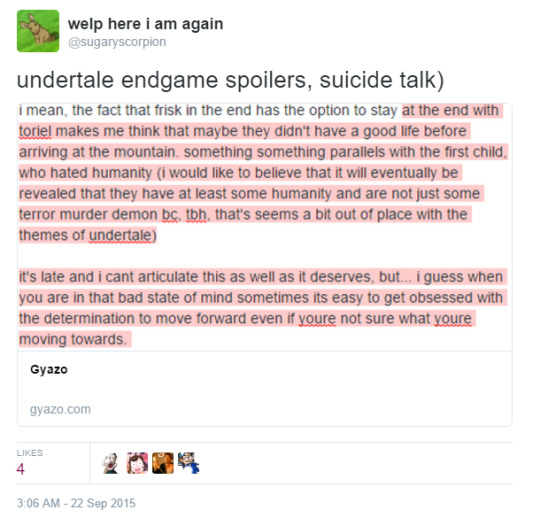

Why Would You Ever Climb A Mountain Like That? – Depression, Suicide, and Surviving In Undertale

(This essay will contain major spoilers for all of the major routes of Undertale, as well as themes of mental illness, suicide, and death.)

Autumn 2015 sure was a good time for indie games, huh?

Remember how I said that writing about We Know The Devil was intimidating, since it felt like so many people had already written so many amazing things about it? Well, imagine that feeling and multiply by a thousand, and you might know what it feels like trying to write something about Undertale. If you’ve spent more than 10 minutes on Tumblr, Twitter, or just about any website between September 15, 2015 and now, you may have heard about it a few times: the little indie project that could, the love letter to the JRPG, the examination of morality in video games, the new big thing all your intellectual friends scoffed at for being too popular. Dogs. Pasta. Skeletons. Any of that ring a bell?

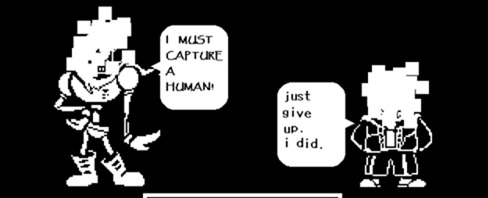

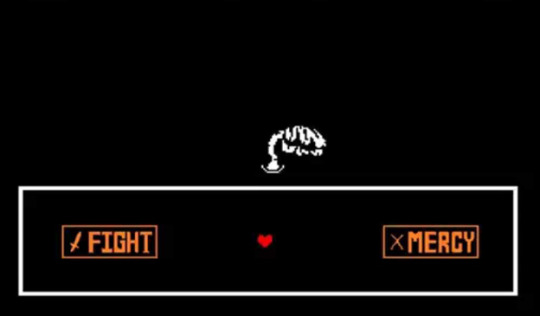

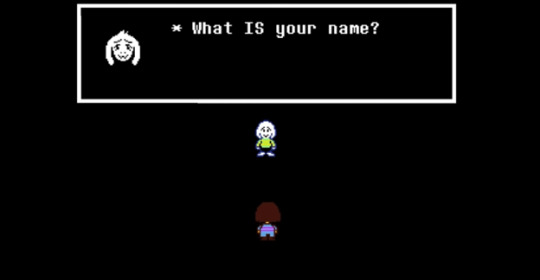

Undertale is an independent role-playing game created by Toby Fox in which the player controls a young child who falls into a strange world populated by monsters and attempts to escape while meeting a cast of colorful characters and learning more about their history and underground society. Like most RPGs, you do battle with monsters, but through a unique combat and dialogue system, you must choose if you want to kill monsters or spare them. Depending on what you choose, you get a different game experience.

There is… quite a lot one could say about Undertale. You could talk about how the unique combat system refreshes the concept of an RPG using bullet hell elements and puzzle-solving. You could talk about how it alternately examines, retools, or deconstructs common video game mechanics and tropes. You could talk about how it uses its soundtracks and leitmotifs to strengthen its storytelling. You could talk about the various ways it plays with the concept of morality systems in video games. You could talk about how much you want to kiss Undyne. You could talk about how it made you cry, and cry, and cry.

Like I said. Intimidating.

There’s lots of good articles and essays about Undertale out there that I like. I’m sure you have a couple. So, yeah, maybe I’m literally a year too late to be getting on this particular train. But here’s the thing: Undertale affected me. It’s a little embarrassing admitting that you were deeply touched by a colorful little video game full of goofy cartoon characters. But it did, and it REALLY did. And the thing is, whenever something affects me to the point I can’t stop thinking about it, I’ve just gotta write about it, and write about it and write about it until I can’t anymore.