Text

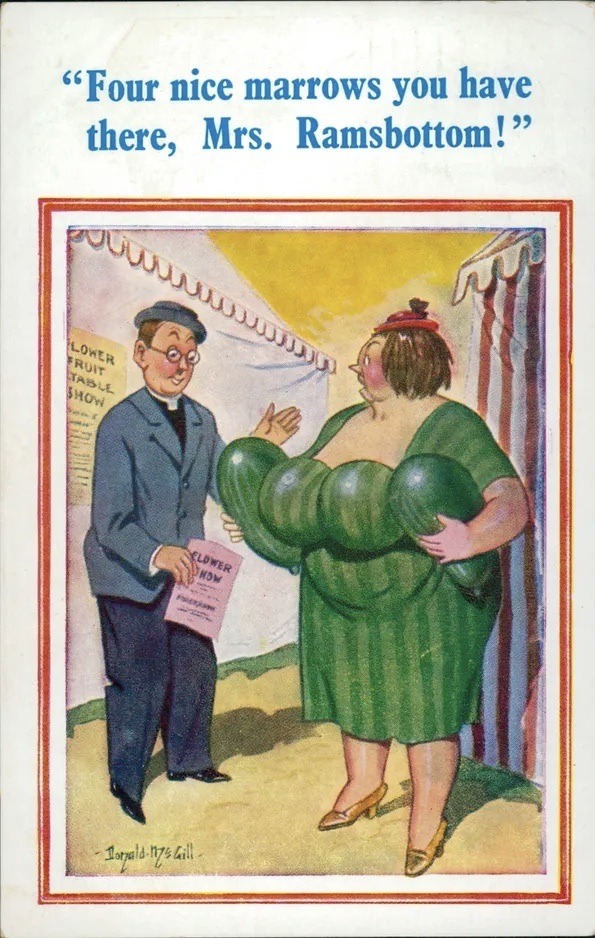

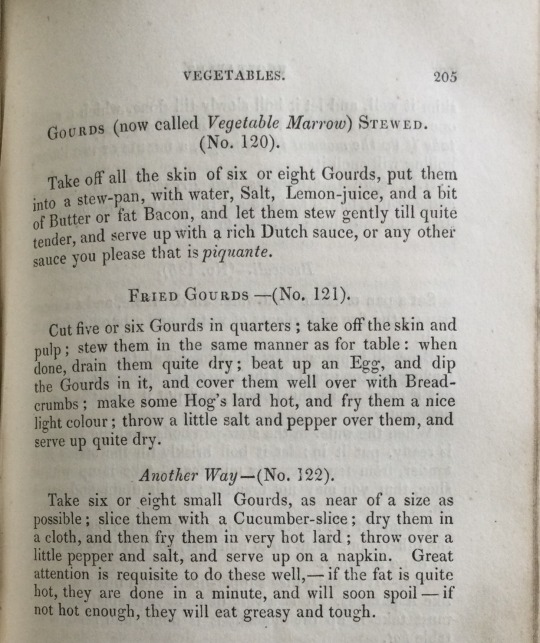

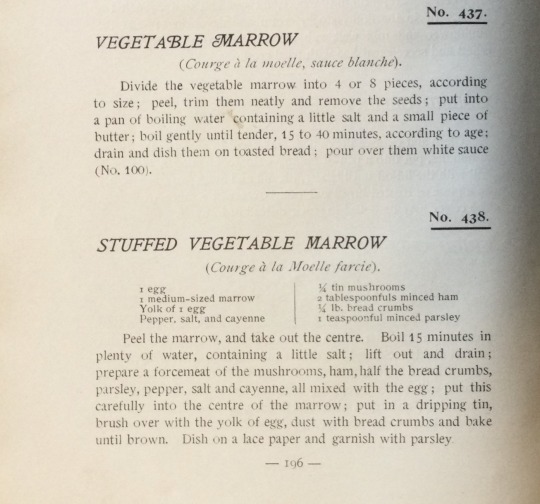

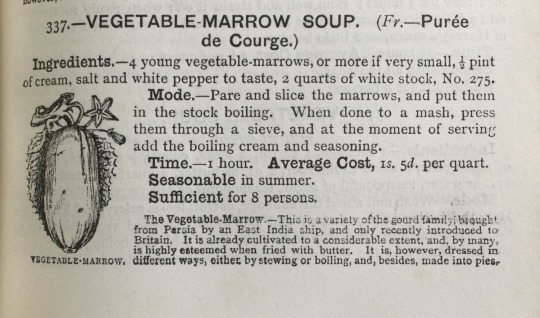

To paraphrase Housman, “Vilest of veg, the marrow now…” But why, as marrows gang up on the gardener, cackling evilly, do we CALL them “vegetable marrows”. The answer may surprise you. https://www.patreon.com/posts/gourd-by-any-be-90532905

A free read.

0 notes

Text

A snippet for you. More original fiction, longer stories, on Patreon/VictoriansVileVictorians.

"We really do advise, in the strongest possible terms, Lady Gribben, that you should not be present in court."

"You keep saying that. But Fitzwilliam is my husband. How could I possibly let him down? I must be there to support him, and that is an end of it."

"Lady Gribben, I cannot believe you will be able to observe the proceedings with composure. I fear you will find the experience most disturbing."

"I am famous for my composure. Nothing Fitzwilliam could do could disturb me. My faith is him is incorruptible."

"Lady Gribben, you have the charges in front of you. They are very plain. Lord Gribben has been charged with Gross Indecency. You do understand what that means?"

"I do not have my reading glasses with me. But it simply means my husband has disrobed himself in inappropriate surroundings. I appreciate that he is severely overweight, but I still find the phrase unnecessarily impertinent."

"Er, um, Lady Gribben, I am very much afraid..."

"It's all just a silly mistake. I expect Fitzwilliam wished to bathe, it was a warm day if I recall. Or perhaps a mouse had become entangled in his underclothing while taking refuge from a terrier. There will be some perfectly innocent explanation."

"... Lady Gribben, the offence of Gross Indecency refers to more than a mere removal of clothing. Perhaps Hargreaves, you might explain?"

"Yes, um, oh. Er, the offence of Gross Indecency under the 1885 Offences Against The Person Act, Lady Gribben, entails, um, behaviour which would be very shocking and offensive to any lady. Without going to, um, unnecessary detail, it, um, involves doing things which, um, any lady would find extremely, um, well, indecent."

"Well, there you are, that just goes to show how ridiculous the charges are. I have been married to Fitzwilliam for eleven years, and he has never in all that time, ONCE behaved toward me with the slightest hint of indecency. I shall give evidence as a character witness!"

"I'm not entirely sure that will be helpful, Lady Gribben..."

*******************************************************

This is a Victorians, Vile Victorians "penny dreadful". There is a free Penny Dreadful every day on Patreon.

0 notes

Text

We go on with our free serial over on Patreon. Original fiction, no subscription, no paywall.

"Is it supposed to look like this?" Bridget replies from the other side of the kitchen, as she has been tempted to on a number of previous occasions, “I'm sure I don't know, ma'm". Miss Barnes snorts at her. "I have no time for that sort of nonsense! Come and look!" Plaintively Bridget explains that she was not being insolent, she really is sure she doesn't know what puff paste is supposed to look like. It seems Mrs Grant, though perfectly happy to pass all the arduous jobs to Bridget, was indeed "close" with all skilled tasks.

Click here to read on. https://www.patreon.com/posts/puff-pastry-89612424?utm_medium=clipboard_copy&utm_source=copyLink&utm_campaign=postshare_creator&utm_content=join_link

#19th century#1800s#victorian era#short fiction#short stories#fiction#social history#victorian#humour#cookery#pastry#cooks

0 notes

Text

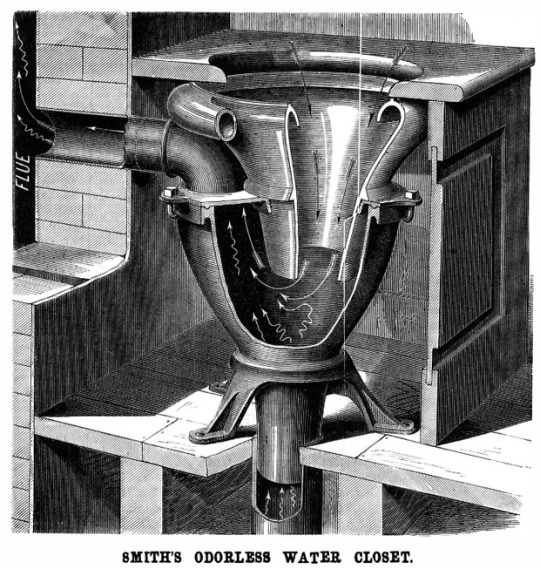

Over on VVV at the moment, a new “free access” serial has just started, with another brand new one for subscribers, both wildly romantic and one of them featuring a favourite villain. But you don’t want to know about that, do you? You want to hear why indoor toilets took so long to catch on, and how the brave policeman lost his life to a pong….

To see stories, click on the bewhiskered face of Sir Joseph Bazalgette and you will be taken to the main page.

#sewage#hygiene#victorian house#disaster strikes#policemen#darwin awards#social history#victorian era

0 notes

Text

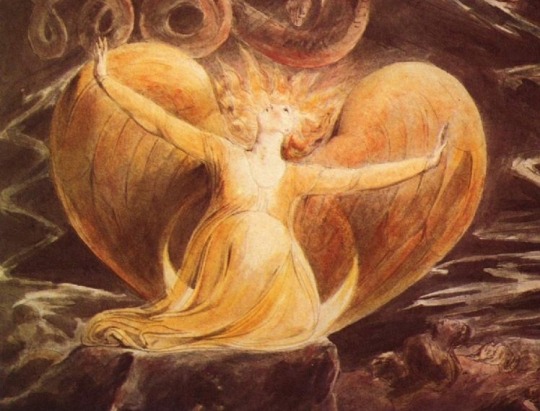

Now live and free on Victorians, Vile Victorians, “The Second Coming isn’t this Tuesday, it’s next Tuesday”. Follow Victorians, Vile Victorians on Patreon for plenty of free reads, and extra jollity for subscribers. Original short stories and surprising history.

#19th century#victorian era#1800s#social history#humour#cults#victorian#emanuel swedenborg#agapemonites

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

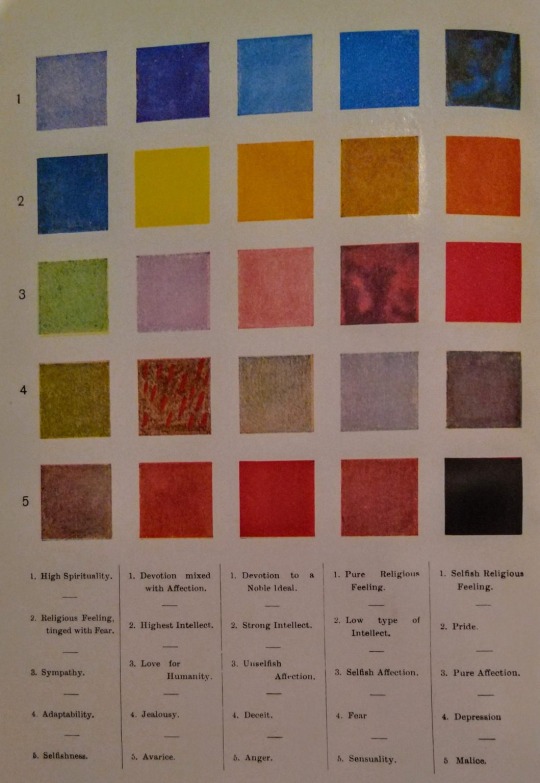

This afternoon on Victorians, Vile Victorians, the roots of abstract art with a woman better known to history for birth control and Indian self-rule… click across for free at https://www.patreon.com/posts/surprising-89112934

0 notes

Text

“Monkeys fight a duel to the death”, Mr Purkiss?

“Oh, come along, Sykes, you’re our animal specialist, you can do it. Use your imagination, it’s what I pay you for.”

“Can’t I do Jealous Husband’s Revenge? You’ve given Jealous Husband’s Revenge to Mallow, and he had Stabbed To Death With A Parasol only last week. You can hardly call it fair. Mallow gets all the stories with beautiful young ladies in.”

“Be reasonable. Can Mallow do Monkeys Fight A Duel To The Death? I ask you as a friend and a colleague, Sykes. No reflection on Mallow, but can you imagine what a hash he’d make of it?”

“But there’s so little to go on. All you’ve given me is “Bangalore. Two monkeys, having chanced upon a brace of loaded pistols, proceeded to conduct a shoot-out worthy of the Wild West. Bystanders, rushing to ascertain the source of the noise of gunfire, found a scene of devastation. The apes, their bodies riddled with bullets, lay expiring at the scene.”

“Yes, Sykes, that’s what was in the Bangalore Observer”

“And did this take place in a bungalow? A military barracks? An hotel? Was the owner of the pistols a British officer? Why did he feel the need to leave loaded pistols lying around? Did he not think of the danger to children or servants? Is Bangalore a lawless area, or did the officer have a particular reason to feel his safety was threatened? Was a lady involved? Did he, in fact, intend to take the loaded pistols and carry out a Dreadful Crime? I need to know! How can I do the story justice with just those one, two… forty nine words?”

“Perhaps the householder had the pistols handy to deal with the monkey menace, Sykes. Have you thought of that? Perhaps the incident took place in a tent, perhaps during a tiger hunt. A tent would be easier for the apes to get into, although I suppose the blighters do climb… Need not even be a bungalow, I suppose. An agile monkey could gain access to a third floor bedroom. Now there’s a thought…”

“But Mr Purkiss, were they monkeys or apes?”

“Monkeys, apes, what does it matter? Monkeys are apes, or apes monkeys, I cannot recall which way round.”

“Ah, but there, Mr Purkiss, you are falling into a common error. A monkey is not an ape, nor an ape a monkey, any more than a donkey is a horse, or vice versa. Except I think it’s even more distant, like a zebra perhaps…”

“Do you presume to give me a lecture in zoology, Purkiss?”

“It being an impertinence doesn’t make it any less true, sir.”

“Well, you had best decide, Sykes. After all you are the expert.”

“There’s no need to be like that, Mr Purkiss. You are the one who always says ‘Accuracy is my watchword’ You would be the last to want the Illustrated Police News to get a reputation for sloppiness.”

“As you see fit, Sykes.”

“Shall I put a beautiful lady in, sir? Rushing to discover the source of the mayhem? Or a pretty maid, in a lace cap?”

“I would think, in Bangalore, any servants would be of the Indian persuasion, and male. Best have a few turbaned figures looking swarthy and terrified.”

“It doesn’t say servants, Mr Purkiss. It says just bystanders. It could be anyone. Very unhelpful it is, if I may say so.”

“Well, I can only apologise for your inconvenience. May I suggest you characterise those rushing to the scene as the putative owners of the pistols, suitably horrified at the misuse to which they have been put.”

“Very well Mr Purkiss. And I shall require the morning off sir…”

“For what purpose?”

“To go to the Natural History museum. To study what species of ape, or indeed monkey, is indigenous to Bangalore and large enough to hold a revolver…”

“Don’t push your luck, Sykes.”

“Oh, I shall make studies from the taxidermy specimens, Mr Purkiss…”

Follow Victorians, Vile Victorians on Patreon for free short fiction, some droll, some romantic, some tragic, every morning. FREE, d’ye hear me? https://www.patreon.com/VictoriansVileVictorians

1 note

·

View note

Text

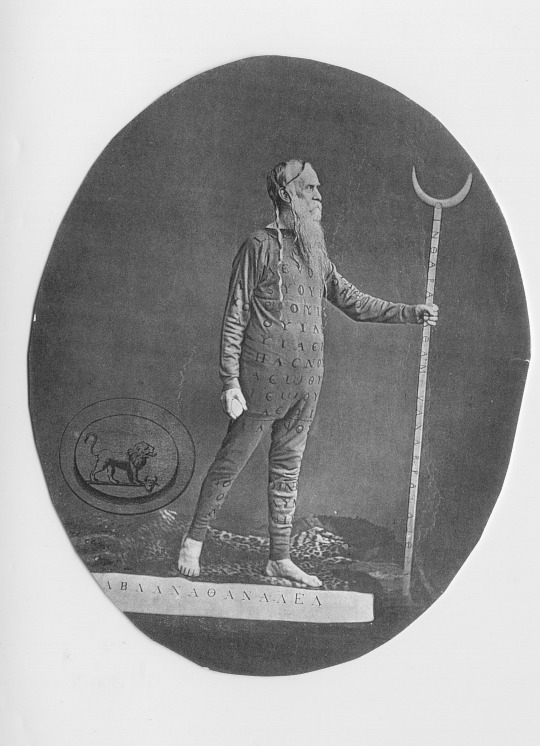

William Price, self-appointed Druid and pioneer of cremation, proves that Jaeger combinations can be a fashion statement.

1 note

·

View note

Text

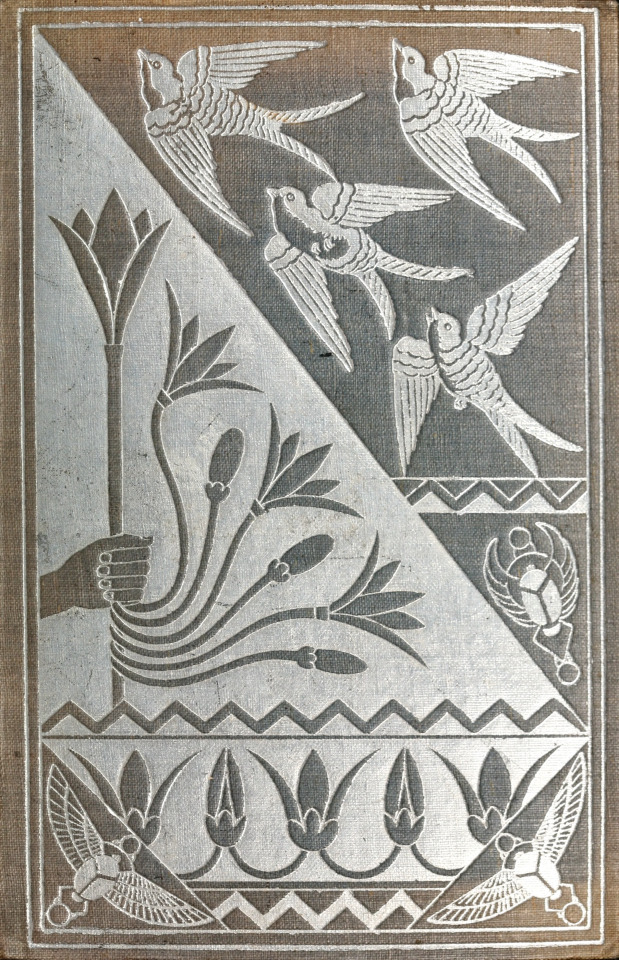

Birds of passage. 1895. Book cover.

Internet Archive

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

A new thing on Victorians, Vile Victorians. The grouped stories and serials are now in “Collections” so you can easily find and read a serial. Many are open access with no need to sign up. Try it now. https://www.patreon.com/VictoriansVileVictorians/collections

#19th century#victorian era#1800s#short fiction#short stories#fiction#social history#victorian#humour

0 notes

Text

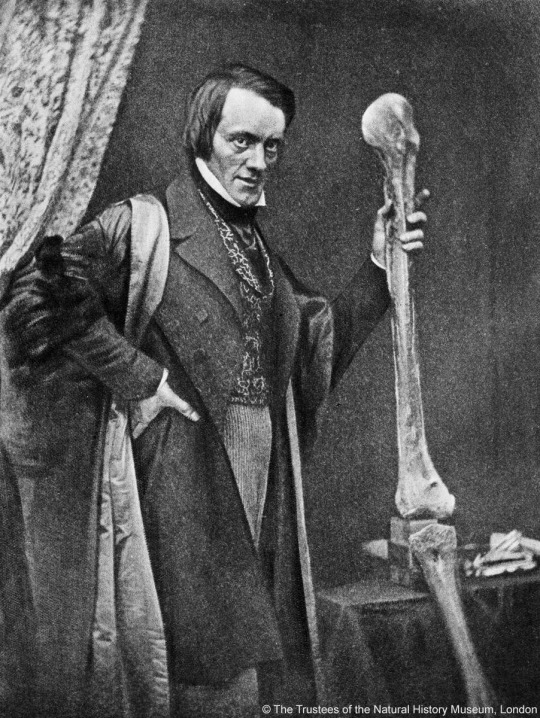

Good guy, bad guy.

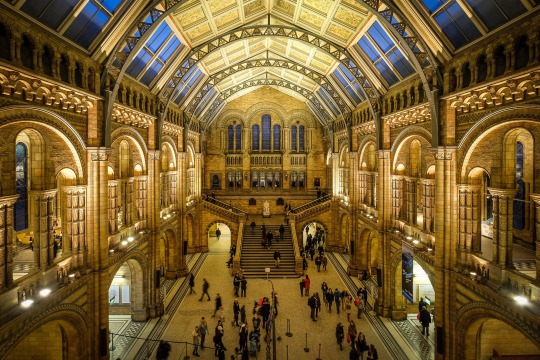

There are two statues in the Natural History Museum, one black, one white. Any irony is unintentional. To a modern audience, the towering figure of Victorian biology was Darwin. This was not so to his mid-century contemporaries. Dominating biology, the “English Cuvier” as he liked to think of himself, was Sir Richard Owen, who entirely agreed with those who felt he bestrode the science of the age like a colossus.

Scientific ability does not however insure good character, and Owen’s moral nature was a compound of hubris, envy, spite and, as one biographer frankly labels it, sadism. In his self-appointed role as the greatest biologist of the age, he liked to patronise promising young scientists. This put him in a useful position to make sure they never achieved anything more than promise.

Like many Victorians, Owen was born a Georgian, and only became Victorian later. The son of a prosperous Northern businessman, he had stumbled by accident into a career as a comparative anatomist. Undistinguished at school, he had showed no early intimations of greatness: as a boy he tried the Navy, but ducked out of that after no more than a taste. Perhaps he judged the position of midshipman offered insufficient opportunities for his considerable ambition…

Read the whole grisly story at https://www.patreon.com/posts/good-guy-bad-guy-87985536

The view from Owen’s statue. But he stands with his back to it.

#natural history#natural history museum#19th century#victorian era#villain#nineteenth century#history of science

0 notes

Text

It’s all kicking off on VVV! A new serial. Did you know these are free? You can follow and get them beamed to your inbox. Victorians Vile Victorians has nearly 30,000 followers on Facebook, find out why or click the Patreon link https://www.patreon.com/VictoriansVileVictorians. You won’t regret it.

Kittens

”She needs something to fuss over” the doctor had suggested. “You should get a little dog”. But little or large, Hetty loathes dogs. His sister has one, and they do go to visit, but each time there is some small, ladylike expression of revulsion. “I suppose we will have to put up with her feeding that animal at the tea table” she will say, not really unreasonably. Or when they have left, she will just wrinkle her nose slightly, and remark to him how pleasant it is to be out in the fresh air again.

Where does it go from here? What are you missing? How can you bear not you know 😉?

0 notes

Text

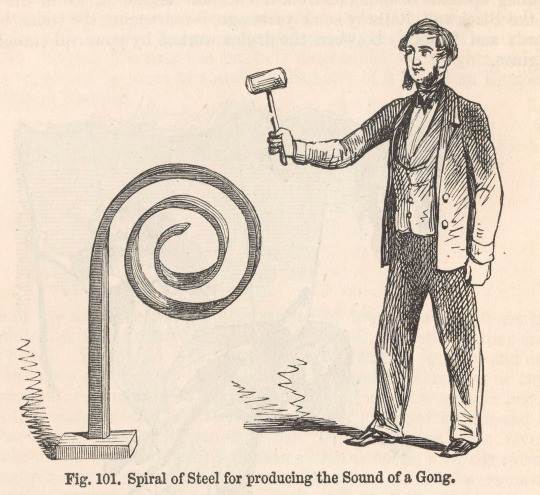

I WANT ONE!

For producing the sound of a gong. The playbook of metals. 1862.

Science History Institute

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Short fiction, longer fiction, non-fiction, a gallimaufry of free stuff at Victorians, Vile Victorians. This sort of thing…

How could he ever have thought she was plain? Life at the rectory has given Abigail no opportunity to wear the revealing evening dresses that are sported at the bishop's palace. She has always been so buttoned up, so neat and finished and self-contained. The rector, of course, is a domestic tyrant as well as a holy terror in the parish: a constant looming background presence, even when he is not there. Their courtship has been a nervous business, intellectual and sensible, and intellectual and sensible companionship is really all Benedict had expected to get from their marriage. Not that he isn't really very fond of her, but it was rather as if their marriage was a conspiracy to get them both out of the power of the Reverend Wilkinson, a sort of legalised elopement.

Even when he was proposing, her father was next door in the study, waiting. Having given his consent, he expected to be informed immediately of his daughter's dutiful acceptance. But here, in the little seaside hotel, they are alone except for the helpful strangers of the staff. The porter had beamed, his pale eyes creased with delight, and the landlady, seeing Abigail's dress, had changed them, at no extra charge, from her cheapest room to her second-best. As they climbed the stairs, the dimpling maid had blushed, and they had both blushed too. It had been the same on the train.

He had been in a lather of embarrassment, originally. The Reverend Wilkinson, a man with rigid ideas on domestic economy, had been reluctant enough to supply the creamy silk for the wedding dress: the suggestion that a "going away costume" might also be required had brought on one of his silent rages, and Abigail's mother had, in the usual desperate, cowed, whispers recommended that Abigail "go away" in her grey wool. Abigail, the sunlit pastures of freedom opening up before her, had said no, she was not wearing grey wool on her wedding day, and she would "go away" in her wedding dress.

Finding themselves universally recognised as newly-weds, instead of being the anticipated ordeal, had been magical. The railway porter had bowed lightheartedly to Abigail as he handed her into the carriage, old ladies had dissolved into smiles, an elderly gentleman, as they alighted from the hackney at the hotel, had raised his hat and said "My very sincere congratulations and felicitations, my children", though he'd never seen them before in his life. And now they were alone at last, the formalities of an early hotel dinner safely accomplished, the summer evening's sun streaming in from the sea, the cloud of gloom which has seemed to hang over him for years is finally banished. He need never, if he choose, see the Reverend Wilkinson again: and if he does, it will not be as a humble curate, the Reverend's dogsbody, but as a vicar with a living of his own, to be taken up at the end of the week.

The curve of her neck, the vulnerability of her bare shoulderblades, has him holding his breath. Suddenly her skin, which seems to have never seen the sunlight before, reminds him of the glistening petals of flowers, seen through the magnifying glass on his botanising outings. Her sleeked down hair which, in a moment will be unleashed and falling like the golden brown of autumn leaves, holds a kind of terror. She rises, from the froth of her tumbled clothing, not like the "angel of the house" he had been promised, but like Venus from the foam of the warm, sinful Mediterranean sea. Would he please unclasp her necklace? The catch is a little tricky... He cannot move. She is waiting. To unclasp the necklace, he will have to touch her neck: his hands are shaking. How can she be so calm?

Married life is going to be not at all as he had thought.

Fill your boots at https://www.patreon.com/VictoriansVileVictorians

0 notes

Text

Follow Victorians, Vile Victorians in Patreon for more original fiction like this for free.

"But you can't wear the red scarf, ma'am!" But the black scarf, Sarah admits, is still in to soak, having become unbearably frowsty, and the white one, despite Sarah's best attempts, is streaked with dull yellow stains. Why anyone thought of wearing white silk next to their neck is a mystery to her. "You could wear a shawl?" Sarah suggests tentatively, but her mistress doesn't reply. She detests shawls, they remind her of market women.

Sarah is not elevated to the status of a lady's maid, and washing the black scarf had taken its place alongside tasks like cleaning out the fires. Mrs Ampleforth had noted, even as a child, that while her mother professed to be exhausted after a tea party, Sarah and her workmates were banging about the kitchen before it was light, and could be heard still clearing up long after she had gone to bed. It had left her slightly in awe of servants, and the feeling had never quite worn off.

Anyway, she explained to her employee, though the sun is bright there is a chill gusty wind, it is still only February, Pedro needs his walk, and who is she going to meet on the Common at this time in the morning? She opens the front door, then steps smartly back inside. Fumbling under her coat, she releases the strings of her crinoline, steps out of it, and hangs it over the newel post at the foot of the stairs. "Madam!" says Sarah in horror. "You'd best pop that straight upstairs, in case anyone calls" she replies calmly, and steps out into the tail end of the storm, her skirts clutched firmly in her hand.

If she hadn't got out of the house, she says to herself, she would have screamed and, having screamed, started smashing the china. The sandy paths, though still damp, hold no puddles, and progress is far easier (and her legs warmer) without the crinoline swaying and bucking in the wind. The scarf cracks and flaps like a flag, pulling out every time she tucks it in, and she ends up clutching it in her other hand. It's a good job there are no gates to open, she thinks, as she doesn't have a hand free. The broad brimmed hat wasn't the best idea, but it is so firmly pinned to her tight plaits that its efforts to escape are futile.

She was wrong, however, about meeting no-one. She passes several working men, and an old lady collecting firewood blown down overnight, who count, for social purposes as No-one, but then she realises the figure chasing his round hat into a clump of juniper is the vicar. In Westheath, the church is out at the end of a lane, and this must be his short cut to the village.

"A red scarf, Mrs Ampleforth?" he says, instead of the customary how-d'ye-do. As he has started the conversation without the usual grace notes, she will follow suit. "Red is God's colour too, Vicar. I am not aware of the Bible discriminating amongst shades." This is clearly more than he bargained for, and he bows and walks on without anything more. She resists the urge to turn her head and see if he is looking back at her.

Nonetheless, the sermon the next Sunday, taking as its text "Render unto Caesar", seems rather pointed to Mrs Ampleforth, seated in the third row in her clean black scarf. Several working men and an old lady collecting firewood have been quite sufficient to pass the news round the village that Mrs Ampleforth had been seen wearing scarlet, while still in second mourning, although fortunately the collective lack of sartorial acuity had barely noticed that her gown had seemed rather bedraggled, and not identified the actual lack of crinoline.

The vicar expands, at length, on the topic of fitting in with our fellows, conforming with what is expected of us, and generally not outraging public decency. As Mrs Ampleforth is close to the front, everyone else has the luxury of staring at the back of her head, while she has only elderly Major Binks to hide behind, and he is asleep as usual. She holds her gaze with rigid stoicism on the altar cross and refuses to blink.

The rest of the service passes in its normal dreariness, and if the vicar, standing to greet his parishioners in the porch before they step out into the rain awaits Mrs Ampleforth with chagrin, he gives no sign of it. Perhaps he is ready with forgiving compassion for her to step forward, eyes downcast. Not a bit of it. "An interesting sermon, Vicar" she observes sharply "one wonders what Our Lord would make of the suggestion that we should take worldly opinion as our moral guide?" She has had half an hour to sharpen and perfect her barb, and is pleased with her firm delivery.

If the vicar has flinched, if she has hit home, she does not see, for she has stepped out into the drizzle with her nose in the air and her gaze straight ahead. On Monday morning, however, when she walks down to the post office with Pedro at her side, she is wearing the scarlet silk scarf like a flag of war.

Reactions are so varied that she is soon too amused to feel any awkwardness. The better sort of villagers simply pretend they have not seen her. Those below her in the social scale blush, or try to hide a sly smile. The children, of course, are unaware of the depths of her outrage, although some of the older ones gasp open mouthed, vaguely conscious they are witnessing a phenomenon. Does she really hear a low buzz of voices as she ducks to go through the low door of the post office, or is she imagining it?

In the darkened room there is only the postmaster, yet even he leans forward and speaks in low, conspiratorial tones. "Aren't you concerned about what Mr Ampleforth might say, looking down?" His tone is amused, the way he raises his eyes to heaven theatrical rather than pious. "Scarlet was his favourite colour, and it was he who gave me the scarf." she says tight-lipped. It is her prepared speech, but the post-master breaks into a broad grin. "Good for you, ma'am", and she finds herself smiling shyly in return.

The postmaster is a notorious free-thinker, and rumoured socialist: but he is also the village's news-service, and she knows that the fact that the disgraceful scarlet-wearing is a tribute to her tenderness for the late Mr Ampleforth rather than an insult to his memory will be disseminated very quickly. But as she and Pedro make their way back, she is restless and fidgety. She may wear a scarlet scarf every day for a month, but it hardly signifies anything other that a desire to tweak the vicar's nose.

Other women, she vaguely appreciates, experience a dissatisfaction with the ways things are arranged. Not such quibbling and, she trusts now purely temporary, inconveniences such as those affecting property, or education, or the vote: these, she is confident, will sooner or later be swept away by Progress, in this modern age. The Sarahs of this world, she is embarrassingly aware, have good reason to be as dissatisfied with the Mrs Ampleforths as with the law. Does the postmaster's rumoured socialism free the Sarahs from tyranny, or only their fathers and husbands, she wonders. She must ask him next week.

Her sister-in-law Jessica has Turned To Rome, which she feels must only make things worse, not better. As if having a husband wasn't bad enough! she catches herself thinking, which is strange, because she never thought it while Henry was alive.... Her mother recommends Good Works, and her brother says she should marry again, and is rather offended at the response he gets. "You need children" he goes on, undefeated. "No I don't!" she snaps, surprising herself.

Turning to the catalogues of progressive publishers, she embarks on a course of reading, but each new book sways her one way until the next comes along to sway her another. The solution to poverty isn't penwipers, and there is more wrong with women than Rational Dress can solve (though it is very tempting): the postmaster, tentatively consulted, concurs and supplies her with a bundle of pamphlets. She agrees with everything they propose, but finds their suggested methods of achieving it naive in the extreme.

Westheath may be charmingly rural, but the train from the little station beyond the windmill whisks her into the centre of London within half an hour. Sensibly shod and soberly dressed, red scarf apart, she tries every institution and library. She attends lectures with titles like "What is religion?" or "An Examination Of The Proposed Methods For Reforming The Plebiscite" and finds, regardless of the advertisement, regardless of the serious, nodding heads in the auditorium, that the point has been sorely missed somewhere along the way.

The old vicar, his grey hairs no doubt dragged down in sorrow, if not to the grave at least to Bournemouth, retires, and his place is taken by a wiry, nervous man who has earned Westheath by service in the East End. She attends church, which she had not quite given up doing, to hear what he has to say. His first sermon explores an obscure point of theology in Saint Augustine. After the service, at the church porch, she shakes hands. "Did you preach like that in the East End?" she asks with wide-eyed innocence. "Good Lord, no. It was all very Evangelical. Why, do you think it went over their heads?" She cannot resist a smile. "Well, it certainly went over mine!" and leaves him there, blushing slightly.

She is of course, by now, no longer young, and the beauty that turned Mr Ampleforth's head is not there to cause awkwardness between her and the Reverend Hughes. Nevertheless, villages being villages, their conversations are conducted at the church porch, or in front of the post office, and are brief. "You should try the Greeks" he ventures one week, having divined from the ether a need. "Which ones?" she asks, thinking vaguely of heavily-bearded church fathers. "I'll make you a list." he promises, boldly. If Mrs Ampleforth has put on weight, and grown grey: if her teeth are no longer so numerous as they were, she is still an imposing woman. "I don't read Greek..." she adds cautiously. "I never for a moment supposed you did." And they laugh nervously at his temerity.

She orders the books on the list from a publisher specialising in cheap editions for the working man. They are refreshingly small, after some of the books she has waded through. They are also surprisingly hard. If people were at this stage more than two thousand years ago, even before Christianity, how is it the world is still such a muddle? "You must try Marcus Aurelius next" says the Reverend Hughes. "I found him a great solace during my worst times." Somewhat alarmed at this encomium, she orders him too.

Somewhat later, she orders a deluxe edition, bound in green morocco with gold tooling. The Reverend Hughes has moved on to Anglo Saxon poetry, and though she is warmly appreciative of the copy of The Wanderer, beautifully calligraphied in his own handwriting, which falls from her Christmas card, she tells him she is more the Ancient Roman than the Dane. The difference of taste does not sour their friendship.

As the years pass, Mrs Ampleforth gets heavier, and greyer, and more of her teeth fall prey to the dentist, while the Reverend Hughes gets leaner, and wirier, (a difference which may be due to her distinct fondness for cake, and his for long solitary walks) and continues to deliver his baffling sermons. The Reverend Hughes flirts briefly with Kierkegaard, but Mrs Ampleforth, despite her other reading, remains faithful to Marcus Aurelius.

As she had predicted during an argument with her sister, all those injustices of property, and education, and politics which had exercised them so wither progressively with the passing of the years, leaving her nieces and, in time, great-nieces aware only of others, as yet unresolved. People forget there was ever a Mr Ampleforth, regarding her title as an honorific, like that bestowed on cooks. She gains, and keeps into extreme old age, a reputation for not suffering fools gladly, and being a good place to turn in a crisis. She watches her contemporaries decline into complacency or fretfulness - all except the Reverend Hughes, who expires in the fullness of years while wrestling with the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.

Mrs Ampleforth lives on, missing him less than she had expected. The older she gets, the fuller her days seem to be. Her maid, Sarah's grand-daughter ("Don't think of it as 'service' " says Granny, "think of it as quite a cushy job with a nice boss. You don't have to stay forever, just till she finds someone else." Which was twenty years ago...) reads the newspaper to her every evening, as the print has got so small these days, a task which is especially bonding during the Great War, when Mrs Ampleforth loses a favourite great-nephew and Sarah's granddaughter loses her sweetheart. She sinks slowly and gently, much comforted by Marcus Aurelius, and eventually passes during the General Strike, her main feeling one of irritation at not knowing how it will end.

She encounters the Reverend Hughes again almost immediately. He is wearing a goatskin, and his wiry limbs are very sunbrowned. She, for her part, seems to be dressed in something soft and loose and pale - bliss after a lifetime of corsets - and her arms, when she glances down at them, are bare and unwrinkled. Looking further, she sees, peeking out from under the creamy wool, feet that have never been forced into tight patent leather boots. Her own dress is expected enough, but his is a puzzle.

"Is this heaven?" she asks tentatively, gazing into a crystalline distance resembling, quite remarkably, that in John Martin's painting at the Tate. "I rather think" says the Reverend Hughes, leaning picturesquely on a staff of rough wood "it must be the Elysian Fields". But just as she no longer cares what happened in the general strike, she meets this observation with quiet calm. "And is everybody here? Or is there ... another place?" The Reverend Hughes observes that this is rather unlikely, as he has met a number of people who would undoubtedly be in it, if there were.

"Really? Anyone interesting?" asks Mrs Ampleforth with excitement, thinking of Ivan the Terrible or Caligula. "Not really..." says the vicar, brushing away an affectionate butterfly "only my Latin tutor and the like. I haven't yet encountered anyone I didn't already know." As she ponders this intriguing peculiarity, a speck in the distant meadow resolves itself into the shape of a bounding, hairy animal with a long pink tongue. "It's Pedro!" she cries, pressing her hands together. "Oh, how awfully, awfully glorious!" Behind the dog labours a figure in an embarrassingly short tunic, carrying a basket. It is the postmaster.

"I say, Emily!" he hails, approaching. Who? My goodness, that will take some getting used to! She hasn't been Emily to anyone since her sister-in-law died. Which is a thought: she wonders what Jessica Ampleforth makes of the present arrangement? The postmaster is breathing a little hard from climbing the hill. "I say!" he repeats "What ho, Fred? Would either of you like a fig? They're awfully good this year Emily. Did you get the vote yet?" The figs are large, a lustrous purple, and wonderfully sweet. "Oh yes, ages ago. Straight after the War." He looks blank. "Which one?" She takes another fig and says "Never mind, eh?" Pedro runs round them in circles, chasing the butterflies.

#19th century#short fiction#victorian era#fiction#short stories#kingdom of heaven#socialism#victorian#mourning#cocker spaniel

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everything Victorian is there at https://www.patreon.com/VictoriansVileVictorians, even original fashion plates.

0 notes