Text

Integrated campaigning is under-conceptualized across the competition continuum

The Department of Defense should consider incorporating robust indicators of success and robust indicators of failure into the concept of integrated campaigning.

Integrated campaigning refers to the achievement and maintenance of strategic policy aims through the integration of military activities and alignment of non-military activities "of sufficient scope, scale, simultaneity, and duration across multiple domains."

This demands "the skillful combination of cooperation, competition below armed conflict, and, when appropriate, armed conflict in conjunction with diplomatic, informational, military, and economic efforts to achieve and sustain strategic objectives."

Drawing on the business management literature, successful integrated campaigning requires an understanding of the competition continuum across multiple levels, not just multiple domains.

Like product launches in the commercial sector, individual markets matter when conducting integrated campaigns.

Within a selected theater, there will always be locations where it is easier or harder to succeed than others. These are the places where military and intelligence leaders should look for strong signals of future success and failure.

Echoing Ronald Klingebiel and John Joseph, there are no one-size-fits-all solutions in major power competition.

For this reason, military and intelligence leaders should test their campaigns in locations where it is easier to succeed, as well as those where it is easier to fail, before committing to them full force.

Right now, integrated campaigning is under-conceptualized across the competition continuum. That needs to change. Otherwise, the United States Armed Forces and the United States Intelligence Community risk unnecessary campaign failures in the future.

Michael Walsh is a Senior Adjunct Fellow at Pacific Forum.

The views expressed are his own.

#department of defense#intelligence community#strategic competition#security studies#integrated campaigning#harvard business school

0 notes

Text

Taiwan needs an integrated set of national security strategies

"The US already has the National Security Strategy and Pacific Partnership Strategy. Taipei needs to make similar strategic planning investments." - Michael Walsh and John Hemmings (10/7/2022)

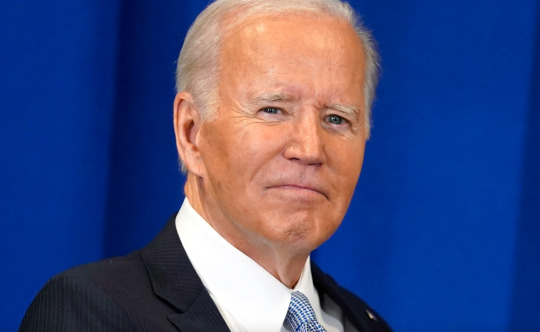

As observed by President Joe Biden, we appear to be fast approaching an inflection point in world history. Faced with no clear enough future, the Taiwan government needs to systematically make strategic decisions on domestic and foreign policy that advance the core national security interests of the peoples of Taiwan across a range of futures. As recently noted by Walsh and Hemmings, this should start with the creation of a set of integrated national security strategies. Building on that argument, this collection of strategies should be deployable and operable across a range of geographic, functional, and community contexts. That may require supplementing the traditional strategy approach with other strategy-building activities, including scenario planning.

At the global level, the Taiwan government needs to develop a multidisciplinary and systematic national security strategy that contains realistic and time-bounded targets. This corporate strategy should be grounded in a core set of principles carefully selected by Taiwan policymakers. Candidates might include autonomy, openness, prosperity, respect, and security. The strategy should identify a core set of national security concerns that frustrate the achievement of those principles. Then, it should identify a core set of instruments for managing those national security concerns. An example would be the strategic partnerships with Japan and the United States. This set of instruments should promote extensive crosscutting cooperation and coordination among government and non-government agencies responsible for defense, democracy, development, and diplomacy.

At the regional level, the Taiwan government needs to develop multidisciplinary and systematic national security strategies for select regions and sub-regions. Distance matters in international security affairs. Proximate sovereign states often share decision-making, collaborate on assessments, and pool resources to promote peace and security in their local neighborhoods. Among other things, this proximity can arise from administrative, cultural, economic, geographic, and historical factors. Examples include the member states of the African Union, Association of Southeast Asian Nations, Commonwealth of Independent States, European Union, Pacific Islands Forum, and Organization of American States. Wherever regionalism threatens to frustrate the successful implementation of the global strategy, Taiwan policymakers should develop regional variants built around values, concerns, and instruments adapted to fit the local conditions. Obvious prospects include Europe, Pacific Islands, and Southeast Asia.

At the functional level, the Taiwan government needs to develop multidisciplinary and systematic strategies for defense, democracy, development, and diplomacy. Functionality matters in domestic and international affairs. Every government agency possesses a unique mix of cultures, missions, roles, legal authorities, ethical norms, funding mechanisms, and political interests that give rise to their own sets of biases, frameworks, processes, terminologies, and planning cultures. For these reasons, Taiwan policymakers should direct the government agencies with primary responsibility for defense, democracy, development, and diplomacy to develop functional variants built around values, concerns, and instruments adapted to fit the local conditions. Ideally, these strategies would not only communicate policy, priorities, and actions to staff, contractors, and other stakeholders. They would also communicate unity of purpose with other government agencies and partner countries. To achieve that outcome, the Taiwan government would need to make significant investments in shared assessments, planning coordination, and alignment reviews.

At the community level, the Taiwan government needs to develop a multidisciplinary and systematic strategy for security relevant groups of people who share common features and manifest collective identities. Community matters in international security affairs. Every community has its own beliefs, cultures, interests, structures, and values that impact the strategic fitness of corporate strategies. Wherever communities threaten to frustrate the successful implementation of the global strategy, Taiwan policymakers should assess those features, determine the strategic fitness, and develop community variants built around values, concerns, and instruments adapted to fit the local conditions. These strategies would help to build more empathetic relationships and take advantage of synergies. Obvious prospects include indigenous peoples and overseas Chinese.

In addition to these integrated strategies, the Taiwan government needs to develop a multidisciplinary and systematic national survival strategy that contains realistic and time-bounded targets. This strategy should identify those processes and functions that would be required to preserve nationhood in the event of occupation by the People’s Republic of China. This strategy should be grounded in its own core set of principles. Candidates might include autonomy, independence, patriotism, respect, and security. The strategy should forecast a core set of national survival concerns that would frustrate the achievement of those principles. Then, it should identify a core set of instruments for managing those national survival concerns. Examples would be nonviolent resistance and violent resistance by Taiwan nationalists. This set of instruments should promote extensive crosscutting cooperation and coordination among the government and non-government agencies forecast to exist in such a contingency.

Echoing an earlier observation by the author, the Taiwan government ideally should have one multidisciplinary team develop all of these strategies through a collaborative process making use of multiple work streams. Such an approach would help to promote systems thinking in strategy development. That not only could help to unlock efficiencies and innovations that otherwise might be missed if different teams set out to develop these strategies independent of one another. It could also help to mitigate the risk of unexpected destabilization in cross-strait relations that could arise from the strategic posture brought into existence by the interaction of these strategies.

Michael Walsh is a Senior Adjunct Fellow at Pacific Forum.

The views expressed are his own.

#taiwan#national security#strategy#integrated strategy#regionalism#indigenous people#overseas chinese#democracy#diplomacy#defense#development#security#survival#national identity

1 note

·

View note

Text

White House should translate regional partnership strategies for Sub-Saharan Africa and Pacific Islands

One of the major problems with natural languages is that it is impossible to fully translate the meanings of complex texts from one language to another.

Fortunately, proficient multilingual translators often can infer the meanings of strategies, policies, and plans with a good degree of accuracy. Then, they can redraft the original texts with reasonable levels of communicative loss.

The United States government should make more of an effort to redraft its regional partnership strategies in the natural languages of indigenous communities around the world.

This should start with Sub-Saharan Africa and the Pacific Islands.

In the last few months, the White House has released new regional partnership strategies for broadening and deepening partnerships in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Pacific Islands.

Unfortunately, the U.S. Strategy toward Sub-Saharan Africa has yet to be translated into Amharic, Hausa, Igbo, Oromo, Shona, Swahili, Yoruba, or Zulu, and the Pacific Partnership Strategy of the United States has yet to be translated into Carlonian, Chamorro, Gilbertese, Hawaiian, Marshallese, Palauan, Māori, Micronesian, Samoan, Solomons Pijin, Tahitian, Toki Pisin, or Tongan.

This is an oversight that seems to frustrate the strategic objectives being pursued by the Biden Administration.

Michael Walsh is an Affiliate of the Center for Australian, New Zealand, and Pacific Studies of the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University. The views expressed are his own.

#pacific islands#africa#foreign policy#language#culture#biden administration#national security council#state department

0 notes

Text

The Vagueness and Contestability of Overseas Military Bases

The concept of an overseas military base is discursively contested and wickedly vague. Factual claims about what counts as a military base are the subject of seemingly endless disputes among major power competitors who have quite divergent interests in what function the concept should play in their strategic language games. There also appears to be borderline cases where there exists an inherent indeterminacy in the application of the term to things out there in the world. Consider these examples. For years, the Chinese government declared that the Chinese People's Liberation Army Support Base in Djibouti was an overseas logistical facility not an overseas military base on the grounds that the motives behind its construction were different than those of Camp Lemonnier. Meanwhile, the question of when a Cooperative Security Location becomes an overseas military base is problematic since the criteria of having “little or no permanent United States presence” is open to the sorites paradox. Whenever the media covers overseas military bases in the Pacific Islands Region, reporters need to be mindful of these philosophical challenges posed by the concept of overseas military bases in our political discourses.

Michael Walsh is an Affiliate of the Center for Australian, New Zealand, and Pacific Islands Studies at the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service of Georgetown University. The views expressed are his own.

Image Source: New Jersey National Guard

#djibouti#niger#solomon islands#kiribati#military base#philosophy#social ontology#vagueness#contested concept

0 notes

Text

Reporters Have Responsibility to Educate About Chinese Overseas Military Posture

In the aftermath of the Solomon Islands-China Security Agreement, Radio Free Asia staff quoted a think tank expert as saying:

“I think now that the security agreement has been officially signed, there is little the U.S. or Australia can do to reverse it. The key question now is how fast will China move to establish a permanent presence, leading to a base, in the Solomon Islands.”

When journalists report this kind of statement, they should take the time to provide their readers with the conceptual framework needed to make sense of the overseas military posture of the People’s Republic of China.

This not only includes the ability to grasp the concepts of overseas military agreements, overseas military forces, and overseas military footprints. It also includes the ability to understand a related set of higher-level and lower-level concepts.

Problematically, most of these concepts are not well known outside of a few epistemic communities.

Among the NATO allied and partner militaries, the overseas military posture of a sovereign state is commonly understood as the overseas military agreements, overseas military forces, and overseas military footprints of its armed forces. These are outlined in Department of Defense Instruction 3000.12:

Overseas military agreements are the agreements and arrangements that set the agreed upon terms of a military’s presence within the territory of another country.

Overseas military forces are the forward deployed and/or stationed forces, military capabilities, equipment,and units of the military.

Overseas military footprints are the locations, infrastructure, facilities, land, and pre-positioned equipment of the military that exist in overseas and/or foreign territories.

At a lower level, these concepts are commonly understood as being composed of different kinds. These are described in the Overseas Basing of U.S. Military Forces Study:

Overseas military agreements include overflight and in-transit rights, status of forces agreements, basing and access agreements, and mutual defense treaties.

Overseas military forces include temporary deployed forces, rotationally deployed forces, and permanently deployed forces.

Overseas military footprints include pre-positioned support infrastructure, en route support infrastructure, command and control infrastructure, access facilities, expansible facilities, and primary facilities.

Armed with this conceptual framework, one not only has the knowledge required to make sense of claims made by subject matter experts about the overseas military posture of the People’s Republic of China. They also have the power to uncover the presence of ambiguity, generalization, vagueness, and contestation in those claims.

Professor Michele Moses once said, “the media have a responsibility to help educate a citizenry so that it is adequately prepared for well-informed deliberation.”

If one accepts this premise, then it seems to follow that the Radio Free Asia staff not only had a responsibility to tell their readers that a security agreement has been signed between the Solomon Islands and the People’s Republic of China and a subject matter expert is concerned that could lead to a permanent presence in the region. They also had a responsibility to empower their readers to be able to respond with the follow-on questions of what kind of security agreement and what kind of permanent presence.

We should demand more from those who cover the overseas military posture of the People's Republic of China - even if Radio Free Asia is a United States government-funded news service.

Michael Walsh is an Affiliate of the Center for Australian, New Zealand, and Pacific Islands Studies at the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service of Georgetown University. The views expressed are his own.

Image Source: Secretary of Defense

#radio free asia#media#military#china#solomon islands#pacific islands#cambodia#djibouti#overseas military base#overseas military posture#forward-deployed forces

0 notes

Text

Letter to Washington Post Editorial Board: Henry Olsen Column

In "Biden cannot let Pacific island nations fall into China’s hands," Henry Olsen argues that the initial reaction from the Pacific Island Country Summit was positive.

Here, I wish that Oslen would have taken the time to explicitly state his premises for reaching this conclusion. This not only would have helped to educate his readers on how and where this positive reaction was expressed by those in attendance. It also would have provided an opportunity to add the caveat that not all Pacific Island leaders appear to have shared this sentiment. This is an important point. Olsen fails to tell his readers that Kiribati did not attend the summit, and they cannot be expected to know nor understand the context and significance of that move.

Another problem with Olsen’s handling of the reaction is that he only presents half of the story. While it is important for his readers to know the reaction from the summit, they also need to know the reaction to the summit. Olsen appears to overlook the significance of that distinction. Otherwise, he would have taken the time to explain to his readers how the media, scholars, watchers, and wonks reacted to the summit. Then, his readers would know that the reaction from the summit and the reaction to the summit have not been the same. The reaction to the summit has been far more mixed. And, there were certain places where the reaction from the summit and the reaction to the summit have pulled in opposite directions.

Michael Walsh is an affiliate of the Center for Australian, New Zealand, and Pacific Studies of the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.

Image Credit: United States Department of State

#state department#united states#washington post#columnist#journalism#media#think tank#biden administration#pacific island country summit#pacific islands#georgetown#diplomacy#henry olsen

0 notes

Text

US Should Think Systematically About Democracy in the Pacific

As a matter of policy, the United States government seeks a free and open Pacific. This concept revolves around three key components. First, the United States seeks a world in which Pacific Islanders are free in their daily lives and reside in liberal democratic societies. Second, the United States seeks a world in which Pacific Island countries are free to manage their own domestic and international affairs. Third, the United States seeks a world in which the Pacific Islands Region is committed to the rules-based order that has governed international relations for decades.

In implementing this policy, the United States government must contend with the inherent tension between freedom, openness, and security in regional affairs. As Abraham Maslow taught us, the need for safety and survival dominates the need for freedom and independence. Given this hierarchy of needs, it is reasonable to expect sovereign states to prioritize foreign relations that ensure their safety and survival over those that promote their freedom and independence. Of course, liberal democratic states tend to prefer international relations with other liberal democratic states, all things being equal. However, all things are rarely if ever equal when major powers compete for access and control in small island states.

To square this circle, the United States government must constantly strike a balance between freedom, openness, and security in regional affairs. As suggested by Thomas Carothers and Benjamin Press, this is particularly difficult whenever there is a risk that confronting a partner government over its lack of commitment to democracy will trigger hostilities that could endanger the security benefits imparted by the relationship. One therefore needs to be mindful of where the Pacific Island countries fall on the political spectrum and where they are willing to engage in relations along the democracy-authoritarian divide. As it stands, several appear prone to such democracy-security dilemmas, including Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, Papua New Guinea, and Solomon Islands. This arguably includes at least one liberal democratic state in Kiribati.

Since the invasion of Ukraine, the United States government has shown a pragmatic willingness to accommodate the non-democratic interests of other sovereign states in return for their strategic alignment against major power competitors. The diplomatic rehabilitation of Saudi Arabia serves as a case in point. Echoing Richard Youngs, this raises the question of whether the ‘free and open Pacific’ will be reduced to a mobilizing narrative for strategic partnerships that are only rhetorically driven by a commitment to strengthening democratic norms. Counter the pundits, the answer to this question still rests with the Biden administration and the United States Congress, who must decide whether it is in the national interest to reorder the region in full or part along the authoritarian-democracy divide.

In search of a coherent and comprehensive reply, the United States government will need to take into account the subregional dynamics at play in the Pacific. Aside from Nauru, the foundations of democracy are relatively strong across Micronesia. The subregion contains the Freely Associated States and many of the United States Pacific Territories. Plus, it is proximate to Hawaii. In contrast, there is far less of a commitment to democratic governance, democratic institutions, and rule of law in Melanesia. Apart from Bougainville, the strategic benefits to be gained by playing the democracy card appear less compelling too. For these reasons, one could argue that a stronger case can be made for reordering Micronesia along the authoritarian-democracy divide than Polynesia and Melanesia.

Whatever the strategic calculus, the United States government should seek to integrate and harmonize its policy approach within the region and beyond.

On the domestic front, a false dichotomy is often drawn between the domestic policy and the foreign policy of the United States in the Pacific. Paraphrasing Martin Holland, they are entwined and interdependent phenomena. Just look at the politics of COFA migration. On the international front, a false binary is often portrayed between the strategic collaborators and the strategic competitors of the United States in the Pacific. As Jonathan Hughes and Jeff Weis have warned, strategic partners are not simple, homogenous entities. Even among allies, one should expect some degree of divergence between what each perceives to be their national security interests and the priorities that should be assigned to them. Consider the Suez Crisis as an example.

To avoid such black and white thinking, the Biden administration and the United States Congress should take into careful consideration the perspectives and interests of the State of Hawaii, United States pacific territories, Freely Associated States, treaty allies, and Taiwan when deciding whether it would be in the national interest to reorder the region in full or part along the authoritarian-democracy divide.

Michael Walsh is an affiliate of the Center for Australian, New Zealand, and Pacific Studies of the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.

This article appeared in The Hill on August 3, 2022.

Image Credit: The Hill Newspaper

#democracy#hawaii#guam#samoa#cnmi#pacific#cofa#palau#marshall islands#micronesia#joe biden#state department

1 note

·

View note

Text

US Must Learn How to Disrupt and Subvert Chinese Partnership Network

The Chinese government is pursuing a new era in strategic alliances to guarantee a multipolar world. This move revolves around the creation of an expansive network of strategic partnerships that are less formal than the strategic alliances of the United States. They also reportedly sidestep hard commitments for mutual protection and mutual restraint.

Within this emerging constellation, each strategic partnership might be viewed as a living system that interacts with the totality of its environment. These open, self-organizing systems are shaped by things like beliefs, doctrines, emotions, ethics, feelings, morals, principles, and values. As a consequence, this sort of network cannot be explained away using practical concerns and realpolitik practices. They are not determined by the threat alignment rationale once assumed to drive strategic alliances during the Cold War.

Practically speaking, this mode for collaboration frustrates harmonization. It also creates the potential for dirty, emotional, and painful affairs. One might say that these strategic partnerships are competitive collaborations that behave much like friendships. They face uncertainty and encounter roadblocks. They therefore demand the sustained commitment of all parties. Otherwise, they risk breaking down and being thrown into the dustbin of history.

So long as this can be avoided, these strategic partnerships not only provide a useful way to steer clear of military entanglements. They also promise to open doors to alternative futures. Think about all of the future worlds made possible by the changing perceptions of young Africans about China.

From an analytical perspective, these strategic partnerships exhibit what scholars refer to as a mutual constitution of agency and structure. As noted, they are not mindlessly determined by the distribution of power out there in the world. They are mindfully constructed out of the beliefs, doctrines, emotions, ethics, feelings, morals, principles, and values held by their respective parties. They are therefore constantly subject to revision and reversion.

Here, perceptions matter. Competitive collaborators are hesitant to reveal their beliefs, doctrines, emotions, ethics, feelings, morals, principles, and values. They therefore must be inferred from observations of their actions and orientations.

As noted by Mahatma Gandhi, particular emphasis should be placed on what happens in times of crisis. This is because the true test of these kinds of relationships is whether assistance will be given in the face of great adversity. The Chinese government clearly appreciates this point. Consider their recent statement on the Russian invasion of Ukraine: “No matter how perilous the international landscape, we will maintain our strategic focus and promote the development of a comprehensive China-Russia partnership in the new era.”

From a strategic perspective, the United States government must be able to effectively and efficiently disrupt and subvert these strategic partnerships in order to win the global governance competition with the People’s Republic of China. The problem is that the United States government has failed to demonstrate the ability to do so. Just look at the recent Solomon Islands pact with China. That needs to change. And it needs to change quickly. Here are some recommendations on how the Biden administration could correct course.

First, the U.S. government needs to fundamentally understand the nature of the strategic partnerships of the People’s Republic of China. This includes grasping the underlying motives that precede and sustain competitive collaboration, processes used to assess and select strategic partners, processes used to negotiate and renegotiate strategic partnerships, relative valuations placed on the potential contributions of strategic partners, governance and control structures used within strategic partnerships, and mechanisms used to achieve organizational learning and knowledge acquisition.

Second, the U.S. government needs to identify potential high-impact vulnerabilities in the strategic partnerships of the People’s Republic of China. This not only includes identifying actions, orientations, and events that could change the perceptions of the People’s Republic of China about the beliefs, doctrines, emotions, ethics, feelings, morals, principles, and values of its strategic partners and potential strategic partners. It also includes identifying actions, orientations, and events that could change the perceptions of those partners about the beliefs, doctrines, emotions, ethics, feelings, morals, principles, and values of China.

Third, the U.S. government needs to systematically exploit the vulnerabilities that exist in China’s strategic partnerships. For that to happen, the U.S. not only needs to possess the defense, democracy, development, and diplomatic capabilities required to exploit those vulnerabilities. It also needs the domestic and international political will to risk using them, especially in times of crisis.

Michael Walsh is an affiliate of the Center for Australian, New Zealand, and Pacific Studies of the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.

This article appeared in The Hill on August 22, 2022.

Image Credit: The Hill Newspaper

#china#russia#xi jinping#vladimir putin#military#defense#ukraine#pentagon#cold war#strategic competition#social constructivism#news

0 notes

Text

Biden Administration Should Avoid Throwing Stones at Pacific Summit

On Wednesday, President Biden will host the first-ever U.S.-Pacific Island Country Summit. The event is designed to bear testament to the shared history, values, and people-to-people ties of the Pacific Island Countries and the United States. Pacific Island leaders hope that it will lead to “real deliverables” on “key issues” that matter to the region. According to the president of the Federated States of Micronesia, those issues are clearly laid out in the Blue Pacific Strategy. Among other things, that strategy declares a regionwide commitment to the principles of democracy and good governance.

Two weeks ago, I had the opportunity to discuss democracy and good governance with Ambassador Ilana Seid of the Palau Mission to the United Nations. During our conversation, Ambassador Seid challenged the notion that democracy and good governance are always better in Hawaii and the United States Pacific Territories than in the Pacific Island Countries. She also warned policymakers against advancing one-shot solutions for promoting democracy and good governance across the Pacific Islands region. Whenever they do, she argued, “it backfires.”

A few weeks earlier, I had argued that the United States government needs to think more systematically about democracy in the Pacific Islands region. I suggested that changes in the states of democracy in one part of the region could lead to significant changes in other parts of the region. Of course, that challenges the notion that a sharp distinction can be drawn between domestic politics and foreign policy in Pacific affairs as it entails that changes in the state of democracy in the Pacific Island Countries can lead to significant changes in the democracy of Hawaii and the U.S. Pacific Territories, and vice versa. The same holds true for good governance.

Sandy Ma, the former executive director of Common Cause Hawaii says that people are not only becoming disenchanted with their state and local governments, they are increasingly disengaged from elections themselves. That is especially true for Native Hawaiians, according to Kuhio Lewis, CEO of the Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement. He said, “I think a good number of Hawaiians just don’t connect with the American system.”

Democracy advocates also express concern that recent scandals involving public officials have started to take a toll on public confidence. Some examples include the federal prosecutions of former Hawaii state senator Jamie Kalani English, state representative Ty Cullen, Honolulu prosecuting attorney Keith Kaneshiro, Honolulu deputy prosecutor Katherine Kealoha, Honolulu police chief Louis Kealoha, and Kauai councilmember Arthur Brun.

On the eve of the U.S.-Pacific Island Country Summit, the Biden administration should take note of concerns being voiced about democracy and good governance in Hawaii and the United States Pacific Territories. These sorts of problems weaken the ability of the United States to advocate for policy interventions designed to strengthen democracy and good governance elsewhere. They also carry unintended consequences for the states of democracy and good governance elsewhere in the Pacific Islands Region.

While there are many positive things that can be said about democracy and good governance in the United States, American diplomats and military leaders do not appear to appreciate fully the challenges to democracy and good governance in Hawaii and the U.S. Pacific Territories and their implications for our foreign policy objectives. Until that changes, the United States will find it difficult to engage in “fruitful conflict” on these matters with their counterparts from Pacific Island Countries.

Michael Walsh is an affiliate of the Center for Australian, New Zealand, and Pacific Studies of the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.

This article appeared in The Hill on September 26, 2022.

Image Credit: The Hill Newspaper

0 notes

Text

Taiwan Should Pay More Attention to COFA Negotiations

In the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, there have been heightened concerns that a Taiwan contingency involving the People’s Republic of China (PRC) will play out in the not too distant future. The 2021 Department of Defense Annual Report on China to Congress asserts that the view PRC leadership views unification as pivotal to its overall policy of Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation, and its piecemeal pressure tactics against Taipei has led the United States (US) President, Joe Biden, to openly state that the US would defend Taiwan in case of invasion. The PRC’s ambitions seem to pose a direct threat to Taiwan’s autonomy and subsequently to regional peace in the wider Indo-Pacific Region.

Already, there are those who think that the US government’s ability to deter or defend against an invasion of Taiwan is at risk due to the changing balance of power between the two superpowers. As Bryan Clark, a senior fellow at Hudson institute, stated in a recent report Defending Guam, the United States Armed Forces “can no longer plan to defeat the PLA in a fire-powered duel over Taiwan.” Instead, the United States government will need to find creative ways to undermine “PLA Confidence” and exploit “decision-making advantages to gain an edge.” Among other things, this requires establishing a widely-distributed, multi-layered network of civilian and military infrastructure across Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia.

The United States government is working hard to deter the existential threat posed to Taiwan by the PRC while making the necessary preparations to be able to successfully defend Taiwan if those efforts fail. Should the United States government not be able to deter such an attack, then the United States Armed Forces and the United States Intelligence Community must be able to effectively and efficiently prevent missile and cyber attacks from taking out critical infrastructure targets essential to the defense of Taiwan over an extended period of time. To thwart these sorts of attacks, the United States government will need to rely on civilian and military infrastructure that is located in and around the Freely Associated States of Palau, Marshall Islands, and Micronesia.

Right now, a key part of that military infrastructure is the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defense Test Site (RTS). Its radar, optical, and telemetry sensors are not just useful for conducting missile tests and space exploration missions. It is expected that they would play a critical role in supporting missile launches, space reconnaissance, and surveillance operations during the defense of Taiwan. Without RTS, the United States Armed Forces and the United States Intelligence Community probably would find it far more difficult to protect allied and partner forward-deployed forces and space-based assets from hypersonic and ballistic missile attacks and other advanced threats during the defense of Taiwan. That is why it is so important to protect the submarine cable and artificial satellite systems that connect RTS to allied and partner military and intelligence facilities around the world, including US Army Cyber Command, US Army Space and Missile Defense Command, and Joint Region Marianas.

For decades, the United States has maintained special relationships of free association with the Freely Associated States by way of the Compacts of Free Association (COFAs). These international agreements not only recognize these Freely Associated States as sovereign states with the authority to conduct their own foreign affairs. They simultaneously grant the authority for their defense and security to the United States. Under these terms, the United States government has the freedom to make use of the civilian and military infrastructure required to protect its national security interests across a wide range of scenarios, including the defense of Taiwan.

These COFAs must be renewed soon. And, the Freely Associated States governments have indicated that they are not satisfied with the proposed terms that have been put forward by their American counterparts. Recently, this spilled out into the public domain when the Marshall Islands government called off a scheduled COFA negotiating meeting. Then, a letter was released from all of the Freely Associated States ambassadors. In it, they expressed concern about being able to reach a successful outcome based on what has been proposed by the Biden Administration. As one might imagine, these moves raised lots of eyebrows during the Pacific Island Country Summit. Whatever is going on behind the scenes, it seems that the negotiations may have started to go off-track. Meanwhile, the US pivot toward Pacific regionalism has introduced a new dynamic into the negotiations. These developments should concern the Taiwan Government as the collapse of negotiations would weaken the deterrent effect of the United States - Taiwan security partnership.

With all of these diplomatic maneuvers play out, the Taiwan Government does not appear to be doing enough to convey the importance of the successful negotiation of these international agreements to domestic and foreign audiences. That needs to change. First, Taiwan and the United States need to work collaboratively with the United States and other partners to 7address the development needs and climate change concerns of the Freely Associated States. Second, Taiwanese diplomats and policymakers need to work closely with their American counterparts on the shared assumption of the critical role that the territories of the Freely Associated States would play in the defense of Taiwan. Third, Taiwanese diplomats and policymakers need to ensure that their Freely Associated State counterparts understand the potential negative consequences that the termination of their COFAs could have on regional stability and by extension their own national interests.

At the same time, the Taiwan Government needs to start thinking far more systematically about its own national security. The US government already has a National Security Strategy and Pacific Partnership Strategy. The Taiwan Government needs to make similar strategic planning investments. The US government also has started to reimagine itself as a Pacific nation. Taiwan would be wise to explore the merits of following suit. This could unlock the benefits that entail from a shared identity.

Either way, the Taiwan Government needs to think long and hard about why the Freely Associated States matter to Taiwan. For too long, its focus has been on diplomatic recognition. That still matters but increasingly less so. We have entered an era of renewed major power competition with a struggle for world order on the side. In this world, there needs to be a shift in focus toward defense and security.

Michael Walsh is an affiliate of the Center for Australian, New Zealand, and Pacific Studies of the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University. John Hemmings is Senior Director of the Indo-Pacific Program at Pacific Forum.

This article appeared in the Taipei Times on October 7, 2022.

Image Credit: Taipei Times

Copyright 2022

0 notes

Text

East-West Center Report Suggests Need for Better Fact-Checking

Asia Matters for America is a longstanding series of reports that provide “visually easy-to-understand data, graphics, analysis, and information on the US-Indo-Pacific relationship.”

Produced by the East-West Center in Washington, these reports are designed to help “policy makers, politicians, business leaders, academics, media, and the general public” make sense of U.S. relations in the Indo-Pacific Region. They are intended to do so through “nonpartisan, credible, and up-to-date information on diplomacy, policy, trade, investment, and educational and cultural exchanges.”

This year, the East-West Center (EWC) published a new report in the series on the Pacific Islands. Funded by the Office of Insular Affairs (OIA), this report is supposed to give a primer on “the trade, investment, employment, business, diplomacy, security, education, tourism, and people-to-people connections between the United States and the Pacific Island Countries.”

Here, the authors set out to make the case that Pacific Island Countries (PICs) matter to America, and vice versa. One of the key pieces of evidence that they use to back-up their argument is that American cities maintain eight sister city partnerships with five Pacific Island Countries. Unfortunately, this claim is based on contradictory and questionable premises.

Digging deeper into the report, the contradictions become apparent.

Whereas the authors claim that there are eight partnerships with five PICs, they only provide a table with six of them. As for the rest, they note that Hawaii “also shares two connections with the US territories of American Samoa and the Northern Mariana Islands.”

The math simply does not add up. Either these American territories must count as sovereign states or two of the sister city partnerships must be missing from the report.

The other problems are less obvious.

Last week, I thought that the mainland partnerships would make a good feature for the Center on Public Diplomacy. So, I set out to do some background research on the Compton, Des Plaines, Gilroy, Neosho, and Oceanside ones.

When I reviewed official websites, I was surprised to find scant mention of these partnerships.

On the Oceanside website, I found a page dedicated to sister cities. It listed cities in China, Ireland, Greece, Japan, Mexico, Montenegro, and the Philippines. However, there was no mention of one in Samoa.

On the other websites, I encountered more problems. The Gilroy website references a regular advisory meeting with the Gilroy Sister City Association. Their website has a page dedicated to a partnership with Koror. However, it fails to mention recent sister city activities. On the Compton, Des Plaines, and Neosho websites, I found nothing of relevance.

When I reached out to city officials, I was in for even more surprises. Their responses suggested the partnerships with A’ana, Apia, Koror, and Nailuva actually don’t seem to matter all that much.

In Gilroy, the president of the Gilroy Sister Cities Association, Hugh Smith, confirmed that the city officially still has a “sister city relationship with Koror,” but that “has been inactive for many years.” He shared that they had sent “a letter to that effect” to their Koror counterparts about a decade ago. However, they “got no reply.” He added, “I doubt if anyone there is even aware of it.” So, what does this mean? In Smith’s words, “For all intents and purposes … we don't have a real sister city in Koror.”

Outside Gilroy, the story appears to be murkier. A Compton official said that they didn’t recall any recent activities with Apia. A Des Plaines official responded, “I’ve done some research internally and as far as I can tell we do not have an active partnership with any Sister Cities at this moment.” An Oceanside official acknowledged, “no - we do not have a Sister City relationship with A’ana.”

These findings left me shaking my head.

EWC seems to have accidentally published inaccurate, or at least misleading, information in their flagship publication on U.S. - Pacific Islands relations. And, that should concern American policymakers.

First, these findings bring into question whether this EWC report is a reliable source. One of the key factors in being able to persuade others that something matters is one’s perceived credibility. When it becomes known that an institution has published inaccurate or misleading information on a particular topic, people will start to question more than the expertise and trustworthiness of the authors of that publication. They will question the credibility of their employer and funder as well. To restore their trust, American policymakers should not only demand that all Asia Matters for America reports be fact-checked post haste. They should require strong fact-checking safeguards be put in place on future research projects funded by the United States Department of Interior.

Second, this incident begs the question of whether the United States has a large enough bench of experts on Pacific Affairs. One of the key strategies for winning any argument is to avoid the fallacy of questionable premises. This exists whenever an argument is based on questionable or unlikely to be acceptable premises. To expose such a fallacy, one has to possess sufficient background information to know that a premise being advanced is questionable or unlikely to be acceptable. In this case, that body of knowledge is Pacific Affairs. Without it, a faulty argument can go unnoticed like this one. To avoid a repeat, American policymakers need to invest in broadening and deepening the bench of American experts. This will require strengthening regional studies departments at universities, improving regional coverage at media outlets, expanding regional programs in think tanks, and creating more regional programs at nonprofits. This is how you create more fact-checkers on the issue. Of course, that will take time. In the interim, Aussie and Kiwi policymakers could fill the gap.

We ought to hold those who we trust to produce facts about the Pacific Islands Region to a high standard. Here, that standard was not met.

However, it is important to recognize that no one is perfect when it comes to writing about regional affairs. Not academics. Not bureaucrats. Not journalists. Not policy wonks. We all make mistakes. And, we actually make them quite often. That’s why we need safeguards like editors and reviewers. They help to protect our reputations. Here, those safeguards unfortunately seem to have broken down.

Michael Walsh is a freelance foreign correspondent who formerly served as the Washington Correspondent for The Diplomat.

This article appeared in the Pacific Island Times on October 4, 2022.

Image Credit: East-West Center Website

Copyright 2022

#east-west center#congress#research#methodology#factchecking#think tank#pacific islands#sister city#public diplomacy#gilroy#oceanside#neosho#des plaines#news

0 notes

Text

The US Pivot Towards Pacific Regionalism

Today, President Joe Biden released the United States’ Pacific partnership strategy. Although it bears some resemblance to the Pacific engagement strategy that was drafted by the Asia–Pacific Security Affairs Subcommittee of the Biden Defense Working Group, this strategy is a separate document that arose through a completely independent drafting process. Nevertheless, it fulfills part of the vision of those who worked on the original policy paper during the 2020 US presidential campaign. It provides a roadmap on the direction for engagement by the US government in the Pacific islands region.

When I reviewed this strategy a few days ago, the first thing that struck me was the considerable emphasis that has been placed on regionalism by the Biden administration. The strategy makes an explicit commitment to bolstering regional institutions such as the Pacific Islands Forum, the Pacific Community and the secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Program. No similar mention is made of a commitment to bolstering sub-regional institutions such as the Melanesian Spearhead Group, Polynesian Leaders Group and Micronesian Presidents’ Summit.

This is significant given the tremendous tension that has existed between regionalism and subregionalism among Pacific island countries over the past few years. Recall what happened last year. The member states of the Micronesian Presidents’ Summit announced their decision to withdraw from the Pacific Islands Forum. Over the summer, Kiribati appeared to follow through on that threat. Those wounds have yet to heal. So, it is quite remarkable that the Biden administration has made the decision to take sides and declare a preference for regionalism in the ordering of the international relations of Pacific island countries.

Yet, this move carries monumental risks. In the short run, it could amplify the regional dynamics involved in the compact negotiations with the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of the Marshall Islands and Republic of Palau. And that could frustrate the successful completion of the renewal negotiations with FSM and the Marshall Islands by the end of the year. In the long run, it could result in the weakening of relations among the Micronesian states and between the Micronesian states and the United States.

It’s therefore important to be clear about one thing: Biden and his administration are taking a gamble here. They are betting that the upside potential is worth more than the downside risks. Let’s hope they’re right. No one wants them to roll craps. That could imperil the preservation of American hegemony in the North Pacific.

After pondering this pivot towards regionalism, I was struck by the realization that this strategy provides a roadmap on the overall direction for only one kind of engagement with the Pacific islands. By definition, it doesn’t provide a roadmap on the overall direction for relationships that result from formal agreements between two or more nations for broad, long-term objectives that further the common interests of the respective parties. It therefore can’t provide a roadmap on the overall direction for free-association relationships and homeland relationships. Here, the scope is more limited. It is targeted at relationships that result from less formal agreements between two or more nations for narrower, shorter term objectives that further the overlapping interests of the respective parties.

As a consequence, the Biden administration has left the US government wanting for a comprehensive roadmap on the overall direction for engagement in the Pacific islands region. Someday, the US Congress may remedy that situation by demanding one. If that happens, the administration could easily fulfill the request by creating two additional national strategies. Like the Pacific partnership strategy, they could be nested side by side under the Indo-Pacific strategy. For argument’s sake, we could call them the Pacific free-association strategy and the Pacific homeland strategy.

Ideally, all of these strategies should have been developed by one team in a collaborative process involving three simultaneous work streams. That would have made the most sense, since the government needs to think systematically about developing, implementing and sustaining relationships in the Pacific islands region. Unfortunately, the National Security Council appears to have taken a different approach with the development of this strategy. That could make it a lot more difficult for the US government to integrate and harmonize its different kinds of engagements across the Pacific islands region.

Michael Walsh is an affiliate of the Center for Australian, New Zealand, and Pacific Studies of the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.

Note: This article appeared in The Strategist on September 30, 2022.

The Mokupuni Magazine | © 2022

#australia#united states#joe biden#pacific island forum#pacific community#pacific partnership strategy#pacific island country summit#congress#melanesian spearhead group#polynesian leaders group#pacific regionalism#micronesia#polynesia#melanesia#aspi

0 notes

Text

We Should Demand More from Those Who Cover the Solomon Islands

Over the last few months, a great deal of ink has been spilt over the strengthening of relations between the Solomon Islands and the People’s Republic of China. Unfortunately, very few of the commentators and reporters have ever been on the ground in those countries to collect the facts needed to fully understand this development. Admittedly, this is in part because neither of their governments appear interested in providing a conducive environment to do so. Similarly, very few possess the regional subject matter expertise to be able to provide the historical, political, and social context required to make sense of those facts that have been gathered. Perhaps that is why some authors add the following disclaimer to their correspondence, “I am not a regional expert.” Then there is the issue of diversity of opinion. Much more is needed in order to test conclusions against alternatives. It is the responsibility of their editors to demand it.

Earlier today, I took it upon myself to collect some facts on the relations between the Solomon Islands and the United States. Specifically, I wanted to gather some more facts about the failure of the Government of the Solomon Islands to provide diplomatic clearance to a United States Coast Guard (USCG) vessel. This incident was widely covered and debated by reporters and pundits in recent days. Unfortunately, their discourse was riddled with sparse details, driven by unstated assumptions, and framed in superficial ways. Rather than stepping into that arena, I reached out to my contacts. I wanted to try to collect some additional facts on the ground. And, this is what I learned from a State Department spokesperson:

On August 23, the Government of the Solomon Islands Government did not provide diplomatic clearance to a USCG vessel that had been seeking to refuel and provision. After the Solomon Islands Government failed to provide the necessary clearance, the USCG Cutter Oliver Henry diverted to Papua New Guinea. It arrived in Port Moresby on the same day. The vessel was in the region to support the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency (FFA). Specifically, it was participating in Operation Island Chief. This operation seeks to enable regional partners to protect their national interests, combat illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, strengthen maritime governance, and model professional maritime behavior to partners and competitors. Operation Island Chief is one of four annual operations that are conducted by the FFA. It occurs in the waters surrounding the FFA member states. These member states include Australia, Cook Islands, Fiji, Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati, Nauru, New Zealand, Niue, Palau, Papua New Guinea, Marshall Islands, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu. The United States Government was disappointed that the USCG Cutter Oliver Henry was not able to make this planned stop in Honiara.

On August 29, the U.S. Navy Ship (USNS) Mercy arrived in Honiara to begin a two-week humanitarian mission that is part of the Pacific Partnership. The Pacific Partnership claims to be the largest annual multinational humanitarian assistance and disaster relief preparedness mission conducted in the Indo-Pacific Region. This year, the Pacific Partnership team is composed of representatives from Australia, Japan, and the United States. These partners coordinate their local events with the host nation. Their events therefore are planned around the requirements and requests set forth by the Solomon Islands. In Honiara, their engagements are intended to include community health outreach and professional medical exchanges, engineering projects, discussions on humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, and community outreach events (e.g. band concerts). The United States Government was pleased that the USNS Mercy was given permission to enter the Solomon Islands. And, the United States remains committed tolong-term engagement in the Pacific. This includes listening to the people of Solomon Islands and responding to their needs.

On August 29, the United States received formal notification from the Government of the Solomon Islands regarding a moratorium on all naval visits, pending updates in protocol procedures. The USNS Mercy had received diplomatic clearance prior to the moratorium being implemented. The United States government will closely monitor the situation.

As already noted, this puzzling set of facts demands further scrutiny by academics, journalists, and think tank fellows. While they may help to fill in some gaps, these facts raise new questions that need to be answered. For example, why does the Government of the Solomon Islands want updates to be made to the protocol procedures? In the coming days, it is my hope that reporters and commentators not only will go out and collect the facts to answer these questions. They will then provide the historical, political, and social context that is required to make sense of them. And, they will showcase a wider range of opinions in their works so that their readers and viewers can test their conclusions against alternatives.

Either way, I hope that the Biden Administration and United States Congress will take a moment to reflect on the recent news coverage of the Solomon Islands. Just as I hope that the national policymakers in the Solomon Islands will do the same. Both have a duty to ensure that their media and citizenry are able to hold accountable those who are responsible for their international relations and their policies. Otherwise, they risk compromising a vital component of democracy in the Pacific.

Michael Walsh is an affiliate of the Center for Australian, New Zealand, and Pacific Studies of the Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University.

Note: This article appeared in Ocean Currents on August 30, 2022.

The Mokupuni Magazine | © 2022

#solomon islands#pacific islands#journalism#congress#joe biden#georgetown university#china#navy#coast guard

1 note

·

View note